ABSTRACT

There has been a commitment to critical reflection research, theory, education, and practice development in social work in the last 15 years, yet less is known about how we effectively teach and assess critical reflection with students in a neo-liberal context. Following the Joanna Briggs framework for scoping reviews, 50 social work education articles from the last 15 years were identified and thematically analyzed, to explore the current knowledge on teaching and assessing critical reflection. This scoping review was co-designed and undertaken by two social work academics and two social work students. Diverse teaching strategies employed within the classroom, field education, and on-line learning spaces and individual written pieces dominated assessment were identified. The voice of social work educators, however, were centered. The results raise questions about the impact of power not only within the educator-student relationship, but also who is conducting the research. The findings point to the importance of social work educators’ role modeling critical reflection, tailoring teaching strategies to respond to students’ learning preferences, and ethical considerations regarding assessment. We consider challenges resulting from neo-liberal pressures within universities and present reflective questions for educators to consider the needs of students and do justice to critical reflection education.

Introduction

Social work professional bodies internationally espouse the importance of critical reflection, an essential component of socially just practice. The International Federation of Social Workers promotes social work curricula that develops critically self-reflective practitioners (IFSW, Citation2020). In Australia, the Australian Association of Social Work’s (AASW) Code of Ethics (Citation2020) presents critical reflection as key to professional integrity. The ability to critically reflect on practice is further reinforced throughout the AASW Practice Standards (Citation2023).

Critical reflection is essential for effective and ethical practice in an ever-changing landscape of uncertainty and structural inequality (Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021). Dominant neo-liberal values—which promote free market solutions, flexible labor, extended work hours, and the deregulation and privatization of industry—have seen bureaucratic and evidence-based approaches increasingly govern organizations (Esau & Keet, Citation2014; Jones et al., Citation2020; Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014). Critical reflection is crucial to uphold social justice in this environment and navigate competing organizational and professional tensions in practice (Humphrey, Citation2009).

Social work education is not immune from these tensions between critical practice and neo-liberal values. Academic institutions are increasingly outcome focused. Amplified by the global pandemic, and associated cost cutting, social work educators are consistently expected to do more with less resourcing (Jones, Citation2020). In this context, and in a bid to develop ‘graduate ready’ students, a competency-based and technical skills approach to teaching can dominate (Jones, Citation2020). This has led to ‘formulaic learning’ where key competencies can be measured and assessed (Froggett et al., Citation2015, p. 137). Social work educators are also expected to effectively teach a relational profession to larger student cohorts (Morley et al., Citation2020). In this environment, teaching and inspiring students’ commitment toward critical reflection is difficult.

In this paper, we understand critical reflection as a process of turning the gaze inward, to investigate personal assumptions, and engage in emancipatory practice which challenges power relations and upholds social justice (Brookfield, Citation2017; Fook, Citation2017; Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014).

To understand and inform current teaching, this scoping review draws together critical reflection teaching and assessment strategies featured in social work education literature in the last 15 years. Our critical reflections as students and academic researchers are shared throughout the article, highlighting the value of a student and academic research team.

Background

Critical reflection is key to interrogating taken-for-granted truths and knowledge claims in social work (Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Fook, Citation2017). Many authors promote critical reflection to identify inequalities (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021) and work toward social justice (Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014). Critical reflection unearths unconscious bias informing our practice and helps us avoid reproducing oppressive power relations (Fook & Gardner, Citation2012). By critically examining how power operates, social workers can enact ethical practice, and find maneuverability in places which feel disempowering for social workers, as well as service users (Giles & Pockett, Citation2012).

There are varying rationales for teaching critical reflection in social work including: developing students’ capacity to apply critical theory and critically analyze (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021; Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Esau & Keet, Citation2014); host multiple and contradictory perspectives (Brookfield, Citation2017; Fook & Askeland, Citation2007); reformulate practice options and generate alternative discourses; and to proactively respond to the competing tensions during field placements (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021; Morley & Dunstan, Citation2013). Other authors highlight how critical reflection enables transformative learning for students, increased self-awareness, and reflexivity (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021; Edwards & Walker, Citation2019; Whitaker & Reimer, Citation2017), and confidence to address inequitable power relations (Fook & Askeland, Citation2007; Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020; Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021). Critical reflection supports learning from events (Walker & Gant, Citation2021) and foregrounds ongoing learning and emancipatory practice beyond university (Lay & McGuire, Citation2010; Pack, Citation2013).

Despite critical reflection being core to social work, challenges exist for teaching such knowledge in a neo-liberal context (Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014). Students now, more than ever, are struggling to study alongside the rising costs of living, often having to make strategic decisions on what teaching activities they engage with (Jones, Citation2020). Academics face their own ‘critical incident’ to engage students meaningfully in critical reflection in an environment increasingly hostile to such contextual and reflexive imaginations of practice.

As a research team consisting of two social work students—one final year Bachelor and one first year Masters—and two social work academics, we were invested in understanding how to teach and assess critical reflection in different ways. As students, we have experienced some teaching that has not extended our capacity to critically reflect. As academics, critical reflection has been highly valued in the social work programs we have worked within, yet often taught in ad hoc ways. We wanted to learn more about the student experience and how to further integrate critical pedagogy into our teaching. The student and academic dialogue throughout the research enriched the analysis and our learning, and we consider this review part of a broader dialogue in social work education. This scoping review investigates current social work education literature to explore how it is possible to teach and assess critical reflection in the current context.

Method

Scoping reviews help investigate how key concepts are conceptualized (McKinstry et al., Citation2014) and gather varying literature to consolidate current ‘evidence’ (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). While critical reflection doesn’t neatly fit formulaic evidence-based teaching, a scoping review allowed us to map the breadth of available literature about teaching and assessing critical reflection in social work (Munn et al., Citation2022). The review addressed the research question: “How is critical reflection taught and assessed in tertiary social work education? The scoping review was undertaken in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute method for scoping reviews. In line with JBI guidelines, a protocol was registered with Open Science Framework on NaN Invalid Date NaN and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist was completed (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Search strategy

Initial search terms were developed from our research question. A preliminary database search identified articles on the topic. Significant terms in the titles, abstracts and keywords of relevant articles were used to develop a full search strategy (see ). Terminology closely related to critical reflection, such as reflexivity and reflective practice were included. The databases included were CINAHL, ProQuest, ERIC, and Scopus. Sources included peer reviewed articles and book chapters including case examples and personal reflections on the teaching or assessing of critical reflection in tertiary social work education. Studies relevant to the research question, written in English, and published in the last 15 years (since 2007), were included.

Table 1. Search Terms.

Study selection

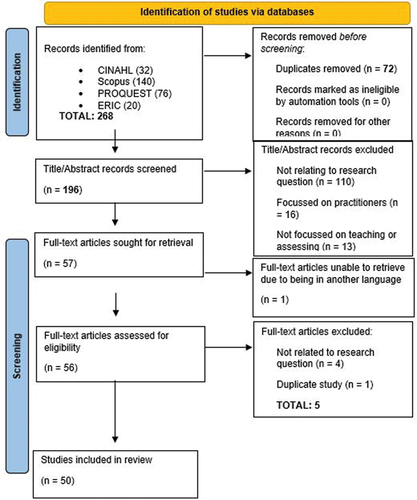

The first search yielded 268 articles, which decreased to 196 after removing duplicates. Initially, one team member screened all titles and abstracts to remove clearly unrelated articles. The remaining 92 titles and abstracts were then screened by two people. Any differing views were resolved through discussion. Sixteen articles were removed due to their focus on critical reflection in social work practice, not education, 13 articles were excluded due to an absence of teaching or assessing of critical reflection in a tertiary setting, and a final six were unrelated. A total of 57 articles were included for full text review. Another six articles were then removed, one was not available in English, an additional duplicate was discovered, and four articles were identified as irrelevant. The search process is presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram below, (Tricco et al., Citation2018). Information on the included 50 articles is captured in .

Table 2. Included articles.

Data analysis

Reflexive Thematic Analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) was undertaken to inductively identify key themes. At least two researchers were involved in each stage—‘1) data familiarisation …; 2) systematic data coding; 3) generating initial themes…; 4) developing and reviewing themes; 5) refining, defining and naming themes; and 6) writing the report’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021, p. 331). Articles were coded in the qualitative analysis software NVivo 12. Final themes are captured in a narrative overview, with a visual presentation of teaching considerations.

The student-academic researcher composition was important during analysis. We met regularly to review the literature, undertake analysis, discuss, and identify key themes. While we shared a commitment to the teaching and learning of critical reflection, we held various experiences and standpoints on critical reflection and gained important insights into the view of the others throughout analysis. This was a powerful process and we have included italicized researcher reflections throughout the findings section.

Findings

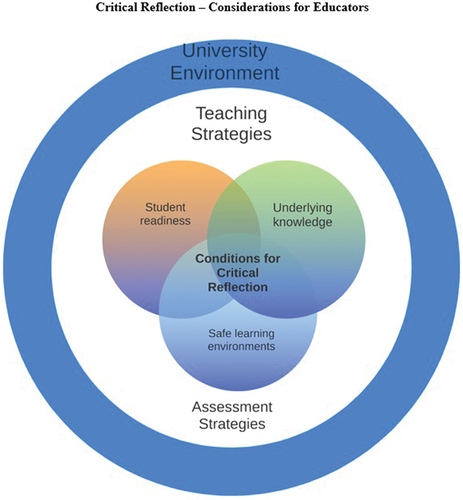

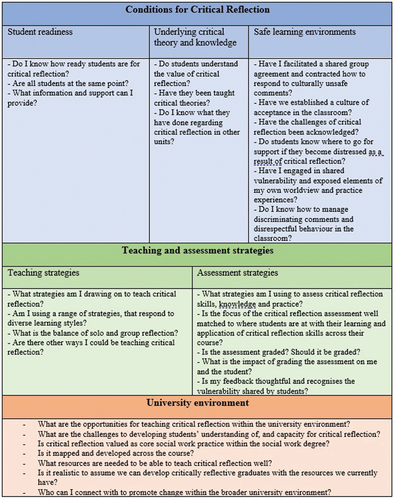

Key findings emerged from the analysis undertaken. These themes captured: the preparation and environment students need before being asked to critically reflect; diverse teaching strategies; dominant assessment strategies and associated challenges; and current barriers faced by educators.

Creating the conditions for critical reflection

Prior to teaching critical reflection, most articles (38) highlighted the need to establish an environment and mind-set conducive to critically reflect. Supporting students to engage in critical reflection was achieved through three strategies—understanding how ready students were to reflect and what support they needed, teaching critical theories and related concepts, and creating a safe classroom.

Student readiness

It was considered essential to recognize how ready students were to reflect, how they may experience and respond to critical reflection, and match education approaches accordingly (Giles & Pockett, Citation2012; Walton, Citation2012).

As a social worker educator with over 15 years’ experience, it can be hard to remember a time when critical reflection was new to me and recognise the assumed knowledge, I hold which may interfere with supporting students to understand and engage in critical reflection. (Academic2)

The literature captured how reflection is not easy for everyone and time must be dedicated to learning how to critically reflect (Ixer, Citation2010). Lawley (Citation2019) describes the initial experience of ‘practising critical reflection [as] difficult, and … bemusing’ (p.35). Before asking students to evaluate their world view, we must acknowledge their ways of knowing (McCusker, Citation2013); only then can we support students to sit with uncertainty long enough to make new connections between personal experiences and professional learning (Ixer, Citation2010; Pack, Citation2013).

Preparing students for critical reflection

Preparation for critical reflection included introducing key concepts and related theories. In one course, a reflective activity was included during orientation, to model reflection and support students:

during fall orientation students and faculty come together as co-learners for group discussion of a ‘summer reading’—a selected work of fiction or non-fiction that probes themes relevant to social work and social justice. Faculty members model critical self-reflection and engage students in conversations that encourage exploration of personal values and assumptions. (Finn & Molloy, Citation2021, p. 178)

Explaining key concepts including critical reflection, reflexivity and positionality, the role and value of critical reflection, and what students and their practice gain from engaging in this process, was considered important (Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; McCusker, Citation2013; Pack, Citation2014).

Teaching critical theories provided foundational knowledge for critical reflection. Critical theories including, social constructionism, anti-oppressive approaches, post-structuralism, and post-modernism, helped to introduce the influence of lived experience and social context, unearth how students make sense of their experience, and realize everyone holds hidden assumptions (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Testa & Egan, Citation2016). They also help students consider the social, cultural, political, and historical contexts of social work; recognize power, oppression, and dominant discourses; and consider possibilities for social justice (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021; Oterholm, Citation2009).

Once I had learnt critical epistemology as a student, I could not ‘unsee’ the inherent power imbalances in society. This is not just a theoretical exercise. Bringing to life this theoretical backdrop is an important responsibility as a social work educator (Academic1).

Creating safety

Critical reflection was recognized as a vulnerable, challenging and sometimes unsettling process (Béres & Fook, Citation2019; Das & Anand, Citation2014; Rosen et al., Citation2017; Theobald et al., Citation2017). Before asking students to engage in and share their critical reflections it is essential to acknowledge the discomfort that may come from questioning our beliefs, establish a safe environment to share personal thoughts and hear differing views, and identify support avenues if students experience distress (Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; Pack, Citation2013; Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019; Theobald et al., Citation2017).

Even with my internalisation of the importance of critical reflection, genuine and honest critical reflection can be difficult, and uncomfortable for me within a tertiary setting. (Student2)

Ground rules are vital to establish safe classrooms, especially as discussions on power and oppression will inevitably provoke debate and strong emotions. Educators need to balance challenge and support, ensuring students do not feel criticized for their opinions (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Ferrera et al., Citation2013; Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020). To build a culture of acceptance, the educator needs to encourage and demonstrate curiosity, and acceptance of uncertainty and differing views (Hughes, Citation2013; Lay & McGuire, Citation2010). Such an environment helps to non-judgementally explore the ‘why’ behind our position and minimize self-blame and criticism of others (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Béres, Citation2019).

When students feel comfortable to share their critical reflections with others, it helps build confidence in reflective practice (McCusker, Citation2013):

Seeing other students … being able to own and examine their vulnerability, and recognising it as an opportunity to learn and develop has helped me recognise … the ability to be ‘professionally vulnerable’ is … a strength, and … essential to being a competent and reflective practitioner. (Lawley, Citation2019, p. 39)

A safe learning environment must address the power imbalance between educators and students. This involves a student-centered approach; making clear teachers are also learners; empathetic communication; recognizing students’ needs; allowing students to make choices about their learning; and working toward emotional safety (Das & Anand, Citation2014; Gair, Citation2011; Lay & McGuire, Citation2010; McCusker, Citation2013; Wiener, Citation2012). This all requires time; critical reflection should not be rushed (Lawley, Citation2019; Walker & Gant, Citation2021).

The need for safe and supportive relationships between myself and the facilitator has been a prominent requirement throughout my social work education, which ensured that I felt comfortable and supported in presenting my reflections to my peers. (Student 1)

Supportive and safe relationships between students and educators are essential for critical reflection (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021). Working to minimize power differentials requires careful consideration of our assessment responsibilities (Béres, Citation2019). As Clare (Citation2007) highlights:

Just as the social worker must be alert to positional authority and the ease with which positive influence can become oppressive coercion, so too must the teacher … my growing awareness of ‘hearing my own words’ in the students’ comments gave me pause for thought as I read their summaries … I searched for confirmation that my role was that of ‘guide and facilitator’ rather than ‘guardian of truth’ for students. (p. 444)

Despite this recognition of the need to support students and acknowledge power differentials, student perspectives do not feature prominently in the literature. Some studies included a few quotes on students’ experiences of critical reflection education, others draw on course evaluation data. Most only evaluate student’s capacity to critical reflect, and the majority center the voice of social work educators. Most articles also present the social work ‘student’ in global terms with only a few defining the varying backgrounds of the students in their study (for e.g. Newcomb et al., Citation2018).

Teaching strategies

Extensive critical reflection teaching strategies emerged across the review, most frequently dialogue, critical incident analysis, case scenarios reflections, and reflective journaling.

Dialogue

Dialogue was the most dominant strategy featuring in 21 articles. Teaching through dialogue recognized the limitations of solo reflection and the deepened learning when exploring views with others (Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020; Jones, Citation2020; Lawley, Citation2019; McCusker, Citation2013). Dialogue helped to explore assumptions (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011), and occurred in class or small group discussion, iterative and sensitive educator feedback, critical questions, and peer dialogue (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Clare, Citation2007; Lay & McGuire, Citation2010; Milne & Adams, Citation2015; Pack, Citation2014; Savaya, Citation2012).

Identifying this theme, enabled further understanding of my ways of critical reflection. As someone who has never been able to effectively critically reflect through journaling or written reflection, conversations with my peers have allowed me to seek differing opinions and ways of thinking that challenge my views. (Student1)

Peer dialogue offered a ‘relatively neutral power framework’ to discuss ideas with a critical friend (Das & Anand, Citation2014, p. 114; Giles & Pockett, Citation2012). Small group discussions fostered safer spaces than larger groups (Clare, Citation2007; Giles & Pockett, Citation2012). During class discussion, staff facilitation was important to support listening, respect, collaboration, and modeling of critical reflection (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; McCusker, Citation2013); a difficult task if teaching online (Ferrera et al., Citation2013). Some articles referred to online reflection meetings or discussion boards as platforms for reflection (Jensen-Hart & Williams, Citation2010; Oterholm, Citation2009).

When other students have the courage to reflect honestly and genuinely in a group, it instils me with courage and a sense of ‘they’re being vulnerable, I can too’. It also helps when paired in smaller groups with students I am comfortable with, it allows for a greater sense of safety for me to be able to speak out and share things in an honest manner. (Student2)

Critical incident analysis

Critical incident analysis or working through disorientating dilemmas was the second most prevalent teaching strategy, appearing in 18 articles. This involved working through challenging situations which: caused stress, anxiety or personal or professional learning; challenged beliefs and taken-for-granted assumptions; raised practice questions; and presented theoretical or ethical dilemmas (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021; Das & Anand, Citation2014; Hughes, Citation2013; Morley, Citation2020). With appropriate unpacking and support, from teachers, field supervisors and peers, these incidences could support self-awareness and professional growth (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2021; Jones, Citation2020).

These disorientating situations often occurred during field placement, where students were exposed to varied experiences and asked to make sense of significant incidents (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Lister & Crisp, Citation2007; Morley, Citation2014; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021). Reflective models, particularly those by Jan Fook and Donald Schon, are commonly used to structure, and prompt this process (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020; Giles & Pockett, Citation2012; Lawley, Citation2019; Oterholm, Citation2009; Testa & Egan, Citation2016). The critical element of reflection is evident in considering discourse, language, power, and context, and reconstructing and developing new understandings, theories, and emancipatory approaches (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Das & Anand, Citation2014, Lister & Crisp, Citation2007; Morley, Citation2020; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021). While critical incident analysis is often written, it may also include verbal presentation and group exploration (Lawley, Citation2019; Lister & Crisp, Citation2007; Savaya, Citation2012).

Case scenarios

Case scenarios appeared as a key strategy in 11 sources and offered an opportunity to practice reflection in realistic-style situations (Cooner, Citation2010). These case scenario reflections drew on similar questions to critical incident analysis but offered a building block to reflection before placement (Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020; Giles & Pockett, Citation2012; Walker & Grant, Citation2021).

Teacher modelling

Teacher modeling emerged in 10 articles as a strategy to teach critical reflection and support students to feel safe in reflecting. Educators sharing critical incidents from their practice, provided examples of critically reflective practice, and the influence of their personal history—demonstrating shared vulnerability and ongoing learning through reflection (Béres, Citation2019; Das & Anand, Citation2014; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021; Oterholm, Citation2009; Pack, Citation2013). McCusker (Citation2013) outlines the value of educator’s use of self to demonstrate:

how their prevailing perspectives were unsettled, how this precipitated an examination of relevant values and assumptions and led to a deep shift in perspective, ultimately changing subsequent actions. (p. 10)

This process can reduce power differentials, build trust, and decrease some of the risk and anxiety of self-disclosure for students (McCusker, Citation2013). Savaya (Citation2012) outlines the value of educator self-disclosure:

it is essential not only to model the technique of critical reflection, but also to convey … that it’s alright to reveal one’s uncertainties and mistakes and … we can all learn from our critical reflection to be better practitioners. Instructors fear that self-exposure will erode their authority in the classroom. Just the opposite occurred here. (p. 185)

I offer a parallel process in the classroom by locating myself and identifying my own privilege as a white, middle-class educator. I demonstrate the messiness and the competing discourses at play, to highlight tensions I have experienced in practice, to show assumptions that informed past interactions with service users, and what I have learnt. (Academic1)

Reflective journalling

Reflective journals, where students consider social justice, ethics, values, and use of self, appeared in nine articles (Cavener & Vincent, Citation2021; Clare, Citation2007; Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; Humphrey, Citation2009; Jensen-Hart & Williams, Citation2010). The journal was mostly referred to as a compulsory task, sometimes brought to class for sharing, and Clare (Citation2007) notes the potential for some resistance from students.

Less prominent strategies

While it is beyond the scope of this article to outline all the teaching strategies in-depth, less prominent themes from the literature included dominant discourse analysis (Bay & Macfarlane, Citation2011; Pack, Citation2013; Patil & Mummery, Citation2020), photovoice (Bowers, Citation2017; Finn & Molloy, Citation2021), creative modalities (McCusker, Citation2013; OKeeffe & Assoulin, Citation2021), student exchanges (Das & Anand, Citation2014; Jones, Citation2020), enquiry-based learning (Giles & Pockett, Citation2012), experiential exercises (Cooner, Citation2010), laddering of values (Burr et al., Citation2016), arts-based story-telling (Grittner, Citation2021), service user narratives (Humphrey, Citation2009; Pack, Citation2013), compare and contrast activities (Newcomb et al., Citation2018), use of metaphor (Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019) and media event reflections (Froggett et al., Citation2015). Aside from some ideas on how to gently introduce students to critical reflection early in their degree (Newcomb et al., Citation2018; Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019), the literature offers minimal guidance on how to stage, develop, and diversify critical reflection education across a social work degree.

Assessment strategies

Assessing written reflections was the dominant approach. Assessed written reflections included reflective journals, critical incident analysis, positionality papers, and sometimes storytelling or poetic writing (Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; Newcomb et al., Citation2018). Written reflections could focus on a review of group work or role-plays, critical incidents, engaging with literature on social issues, applying theory to practice, and considering the impact of personal experiences and professional values (Giles & Pockett, Citation2012; Lay & McGuire, Citation2010; Lister & Crisp, Citation2007; McCusker, Citation2013; Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021; Oterholm, Citation2009, Patil & Mummery, Citation2020; Walton, Citation2012). Critical incidents are sometimes verbally presented in class for assessment and feedback (Morley & Stenhouse, Citation2021). Students have identified the value of moving beyond written reflections for assessments—through peer dialogue or digital recording of reflections—to support engagement and more authentic strategies for future practice (Newcomb et al., Citation2018). Alternate modes for reflections included mind maps, poster sessions, peer workshops (Wiener, Citation2012), sharing food that is meaningful to their identity (Rosen et al., Citation2017), and critically examining their assessment of a case study (Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, Citation2020).

Potential issues when assessing critical reflections included shifting a process of ‘professional and academic self-discovery’ to a performative task, reducing authenticity, and being approached strategically (Newcomb et al., Citation2018, p. 335; Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019). There are also safety considerations for students with past or current trauma (Newcomb et al., Citation2018). Students noted the challenges of being assessed and effectively judged when sharing their past experiences (Newcomb et al., Citation2018).

This theme asked me to really engage with the student position and the impact of assessing students when we ask them to be vulnerable, further reinforced when one of the student researchers said ‘Let’s be clear, assessment is never safe for students’. (Academic2)

Reimer and Whitaker (Citation2019) advised against assessing students’ reflections on disturbing events early in degrees, starting instead with their understanding of critical reflection. Some articles offer assessment rubrics to assist with marking reflections (Engelbertink et al., Citation2022; Lay & McGuire, Citation2010). Pack (Citation2014) describes providing formative feedback to reflective journal entries and grading the task complete/incomplete rather than offering a numeric grade. Ixer (Citation2010), notes the challenges in assessing critical reflection given the diverse ways reflection is defined and practiced.

Barriers

Barriers to teaching and assessing critical reflection emerged in 31 articles. The neo-liberal environment influencing social work practice and education was a dominant barrier (Theobald et al., Citation2017). In higher education neo-liberal values could prioritize technically skilled graduates, compromise the value of critical reflection, and limit time to teach, develop, and support reflection and critical thinking (Finn & Molloy, Citation2021; Ixer, Citation2010; Jones, Citation2020, Morley & Macfarlane, Citation2014; O’Keeffe & Assoulin, Citation2021; McCusker, Citation2013). Increasing focus on ‘best practice’ and measuring performance could interfere with safe environments for critical reflection and discourage exploration of vulnerabilities (Morley & Dunstan, Citation2013; Pack, Citation2013). When critical thinking is conceptualized as a rote skill focused on ‘reasoning to support one’s objective evidence for practice’, social workers are positioned as expert, and client knowledge, process, curiosity, and social change are undervalued (Lay & McGuire, Citation2010, p. 542; Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019).

Macías (Citation2013) highlights the ways neo-liberalism positions students as consumers, making it difficult for educators to challenge students and discuss power, racism, and emancipation:

Within increasingly neo-liberalised university and practice settings, bubble-bursting moments are more likely to become no more than bubble-nudging moments in which students may momentarily feel unsettled but quickly recover and restabilize themselves in the certainty of a neo-liberal common sense that remains steeped in whiteness. (p. 323)

The high value placed on student evaluation of units can make educators reluctant to include activities that create discomfort, despite the potential for transformative learning (McCusker, Citation2013).

Additional barriers included students’ fears of being vulnerable and potentially judged for their self-reflections, especially when formally assessed (Lawley, Citation2019; McCusker, Citation2013, Newcomb et al., Citation2018; Testa & Egan, Citation2016). Students may be fearful of failing placements if they are critical and challenge sources of power (Humphrey, Citation2009). Ongoing critical reflections across their degree may also create resistance (Finn & Molloy, Citation2021), especially as asking students to write about their adversity can be emotionally draining (Newcomb et al., Citation2018; Reimer & Whitaker, Citation2019). The absence of in-depth student perspectives across the literature makes it difficult to understand the impacts of current pressures including increased living costs. The findings revealed a multi-layered understanding of how critical reflection is being taught and assessed by social work educators, the tensions present in tertiary education for students and educators, and gaps for future research.

Considerations for educators

From the findings, we developed a visual summary and reflective questions, to help review teaching practices and learning environments. These Considerations for Educators are presented in to support thoughtful approaches to critical reflection education.

Discussion

This scoping review identified many teaching strategies and highlighted how teaching critical reflection is more than a generic ‘strategy’ or ‘technique’; it requires a relational approach. Preparation is essential. Introducing students to critical theory lays the foundation for critical reflection. A culture of safety is a non-negotiable for students. Educators need to understand and respond to power differentials. This involves educators identifying their own privilege, acknowledging unconscious bias, and exposing the messy realities inherent in their practice. Engaging students in critical reflection cannot be the responsibility of a single educator. Whole-of-course planning is required to scaffold learning and build confidence to challenge sources of oppression (Morley et al., Citation2020). These planned and relational approaches to critical pedagogy are, however, not easily achieved in the current tertiary context. The literature did not offer guidance regarding navigating the daily critical incidents social work educators and students face in a neo-liberal context (Jones, Citation2020; Macías, Citation2013). How do we create spaces of safety and critical reflection, with rising student numbers in on-line or face-to-face cohorts?

The translation of teaching strategies identified in the review is context dependent. The focus, therefore, needs to be on both teaching approaches used and the learning experiences of students. Students’ voices were limited in the literature. This is surprising, given the profession’s commitment to service user partnership in research. We need to question how possible critical reflection is when our diverse student cohorts are impacted differently by the rising costs of living and have limited resources (Jones, Citation2020). Students face significant financial pressure while studying, with many forced to live in poverty (Morley et al., Citation2023). Critical reflection is a privilege in itself. Students’ position as consumers of education (Giroux, Citation2002), also raises questions about how far educators can challenge students to engage in unsettling matters of privilege.

While critical reflection is essential for social work graduates, we need to contest it as a competency, from which students are measured. Current research has largely missed the opportunity to consult students about what forms of assessment enhance their critical reflection. The review highlights dialogue is essential to engage students in critical reflection, however, individual written assessments continue to dominate. In the absence of any dialogue, students risk superficial description without deconstructing the deeper assumptions they hold. Even if students can identify unconscious bias, self-awareness alone does not lead to action (Lam et al., Citation2007; Patil & Mummery, Citation2020). Without in-depth deconstruction, the extent to which individual assessments support them to reconstruct new meaning to inform future action is questionable. Assessment needs to go beyond enhancing students’ awareness, because critical reflection ‘is not fulfilled without a commitment to changes for the benefit of people’ (Askeland & Fook, Citation2009, p. 287).

Engendering the ‘critical’ in critical reflection requires students to interrogate and deconstruct taken-for-granted ideology that perpetuates unequal power relations. At the same time, assessing critical reflection is fraught with power relations. How can we meet educational requirements of assessing students, and ensuring graduates have demonstrated ‘skills’ in critical reflection, without being hypocritical in our use of power? Research is required to grapple with these tensions and explore how assessments can ‘shift the balance of power/knowledge’ (D’cruz et al., Citation2007, p. 83), while also challenging students to engage in unsettling learning to support emancipatory practice (Fook, Citation2016). We must ask why reflective assessments are graded, whose needs are being met, and whether this interferes with genuine and in-depth reflection to support thoughtful and socially just practice development.

Commitment to critical reflection is not enough. To avoid formulaic forms of teaching and to co-create spaces of critical transformative learning with students, we need to turn the gaze on our pedagogy to question knowledge production in social work education. This involves a process of reflexivity where educators cast their view ‘outward, to the social and cultural artifacts and forms of thought which saturate [their] practices’ (White, Citation2001, p. 102) and at the same time, turn their gaze inward to question what assumptions they bring (Lam et al., Citation2007). Such reflexivity is only possible with further insight from the student perspective. Students as co-researchers offer invaluable insights. Involving students as research partners to co-design critical reflection learning processes will improve social work education. Further investigation of teaching critical reflection online is needed (Gates et al., Citation2021). Given the dramatic increase of on-line social work courses, further examination of how to create dialogic spaces when teaching critical reflection with a diverse student cohort on-line, in synchronous and asynchronous formats, is required.

Conclusion

Social work graduates require consolidated skills of critical reflection to navigate increasingly complex practice terrains, enact ethical and socially just practice, and sustain themselves. At the same time, higher education has become inherently shaped by a neo-liberal agenda prioritizing formulaic and competency-based teaching to ensure graduates are ‘work ready’. This scoping review highlights how educators can prepare and support students to engage in reflection; the diverse teaching approaches that might be implemented across a degree and the barriers to teaching critical reflection in a neo-liberal environment. The challenges of assessing critical reflection were evident, including an overreliance on solo written assessments, despite multi-perspective dialogue emerging as a key teaching strategy. Further investigation is required to explore how social work educators can avoid reductionist approaches and bring a relational approach to their teaching. We need to turn the gaze outward to critical examine the neo-liberal teaching agenda and at the same time look inward, to question our teaching and assessment practices. We need to more actively involve students in critical reflection research and curriculum design. Despite the challenging education context that social work educators and students face, we need to continue to find ways to support transformative learning which could be a catalyst toward societal change ‘where human rights and social justice is the “natural order”’ (Noble et al., Citation2016. p.114).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Mark Brough’s support and feedback on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katherine Reid

Katherine Reid is a lecturer in social work in the School of Health Science and Social Work. Her research interests include children’s mental health and child-centred family focused practice.

Elise Woodman

Elise Woodman is a senior lecturer in social work at ACU. Her research areas include evidence-informed practice, children’s participation, and youth wellbeing.

Willow Trost

Willow Trost was a previous Bachelor of Social Work student at ACU. Her practice interest include child protection social work, particularly working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families to lessen their representation in the child protection system.

Kian Prammar

Kian Prammar is a Master of Social Work student at ACU, completing his degree in 2023.

References

- Archer-Kuhn, B., Samson, P., Damianakis, T., Barrett, B., Matin, S., & Ahern, C. (2021). Transformative learning in field education: Students bridging the theory/practice gap. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(7), 2419–2438. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa082

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Askeland, G. A., & Fook, J. (2009). Critical reflection in social work. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450903100851

- Australian Association of Social Work. (2020). Australian association of social workers code of ethics. AASW. https://aasw-prod.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/AASW-Code-of-Ethics-2020.pdf

- Australian Association of Social Work. (2023). Practice standards. AASW. https://www.ifsw.org/global-standards-for-social-work-education-and-training/

- Bay, U., & Macfarlane, S. (2011). Teaching critical reflection: A tool for transformative learning in social work? Social Work Education, 30(7), 745–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2010.516429

- Béres, L. (2019). Reflections on learning as a teacher: Sharing vulnerability. In L. Beres & J. Fook (Eds.), Learning critical reflection: Experiences of the transformative learning process (pp. 123–138). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351033305-11

- Béres, L., & Fook, J. (2019). Learning critical reflection: Experiences of the transformative learning process. Routledge.

- Bowers, P. H. (2017). A case study of photovoice as a critical reflection strategy in a field seminar. The Field Educator, 7(2).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. John Wiley & Sons.

- Burr, V., Blyth, E., Sutcliffe, J., & King, N. (2016). Encouraging self-reflection in social work students: Using personal construct methods. British Journal of Social Work, 46(7), 1997–2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw014

- Cavener, J., & Vincent, S. (2021). Enhancing knowledge and practice of ‘personal reflexivity’ among social work students: A pedagogical strategy informed by Archer’s theory. Social Work Education, 40(8), 961–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1764522

- Clare, B. (2007). Promoting deep learning: A teaching, learning and assessment endeavour [article]. Social Work Education, 26(5), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470601118571

- Cooner, T. S. (2010). Creating opportunities for students in large cohorts to reflect in and on practice: Lessons learnt from a formative evaluation of students’ experiences of a technology-enhanced blended learning design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00933.x

- Das, C., & Anand, J. C. (2014). Strategies for critical reflection in international contexts for social work students. International Social Work, 57(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872812443693

- D’cruz, H., Gillingham, P., & Melendez, S. (2007). Reflexivity, its meanings and relevance for social work: A critical review of the literature. The British Journal of Social Work, 37(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl001

- Edwards, T. M., & Walker, M. (2019). Enhancing transformation: The value of applying narrative therapy techniques when engaging in critical reflection. Journal of Transformative Education, 17(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344619847142

- Engelbertink, M. M., Kelders, S. M., Woudt-Mittendorff, K. M., & Westerhof, G. J. (2022). The added value of autobiographical reflexivity with persuasive technology for professional identities of social work students: A randomized controlled trial. Social Work Education, 41(5), 767–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1888910

- Esau, M., & Keet, A. (2014). Reflective social work education in support of socially just social work practice: The experience of social work students at a university in South Africa [article]. Social Work (South Africa), 50(4), 455–468. https://doi.org/10.15270/50-4-384

- Ferrera, M., Ostrander, N., & Crabtree-Nelson, S. (2013). Establishing a community of inquiry through hybrid courses in clinical social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(4–5), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.835765

- Finn, J., & Molloy, J. (2021). Advanced integrated practice: Bridging the micro-macro divide in social work pedagogy and practice. Social Work Education, 40(2), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1858043

- Fook, J. (2017). Critical reflection and transformative possibilities. In P. Leonard & J. Fook (Eds.), Social work in a corporate era (pp. 16–30). Routledge.

- Fook, J., & Askeland, G. A. (2007). Challenges of critical reflection: ‘nothing ventured, nothing gained’. Social Work Education, 26(5), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470601118662

- Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2012). Critical reflection in context : Applications in health and social care. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uwsau/detail.action?docID=1039238

- Froggett, L., Ramvi, E., & Davies, L. (2015). Thinking from experience in psychosocial practice: Reclaiming and teaching ‘use of self’. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2014.923389

- Gair, S. (2011). Creating spaces for critical reflection in social work education: Learning from a classroom-based empathy project. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.601099

- Gates, T. G., Ross, D., Bennett, B., & Jonathan, K. (2021). Teaching mental health and well-being online in a crisis: Fostering love and self-compassion in clinical social work education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00786-z

- Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, S. (2020). Looking for elderly people´s needs: Teaching critical reflection in Swedish social work education. Social Work Education, 39(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1617846

- Giles, R., & Pockett, R. (2012). Critical reflection in social work education. In J. Fook & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in context (pp. 220–230). Routledge.

- Giroux, H. (2002). Neoliberalism, corporate culture, and the promise of higher education: The university as a democratic public sphere. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4), 425–464. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.4.0515nr62324n71p1

- Grittner, A., (2021). Sensory arts-based storytelling as critical reflection: Tales from an online graduate social work classroom. Learning Landscapes, 14(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.36510/LEARNLAND.V14I1.1050

- Hughes, M. (2013). Enabling learners to think for themselves: Reflections on a community placement [article]. Social Work Education, 32(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.734803

- Humphrey, C. (2009). By the light of the Tao. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450902930779

- International Federation of Social Work. (2020, August 1). Global standards for social work education and training. IFSW. https://www.ifsw.org/global-standards-for-social-work-education-and-training

- Ixer, G. (2010). ‘There’s no such thing as reflection’ ten years on. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1921/146066910X570285

- Jensen-Hart, S., & Williams, D. J. (2010). Blending voices: Autoethnography as a vehicle for critical reflection in social work. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2010.515911

- Jones, P. (2020). Critical transformative learning and social work education: Jack Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Pedagogies for Social Work, 489–500. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002042-40

- Jones, B., Currin-Mcculloch, J., Petruzzi, L., Phillips, F., Kaushik, S., & Smith, B. (2020). Transformative teams in health care: Enhancing social work student identity, voice, and leadership in a longitudinal interprofessional education (ipe) course. Advances in Social Work, 20(2), 424–439. https://doi.org/10.18060/23671

- Lam, C. M., Wong, H., & Leung, T. T. F. (2007). An unfinished reflexive journey: Social work students’ reflection on their placement experiences. British Journal of Social Work, 37(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl320

- Lawley, S. (2019). The energising experience of being nonjudgmental in the critical reflection process. Learning Critical Reflection: Experiences of the Transformative Learning Process, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351033305-3

- Lay, K., & McGuire, L. (2010). Building a lens for critical reflection and reflexivity in social work education. Social Work Education, 29(5), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903159125

- Lister, P. G., & Crisp, B. R. (2007). Critical incident analyses: A practice learning tool for students and practitioners. Practice, 19(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150701220507

- Macías, T. (2013). “Bursting bubbles” the challenges of teaching critical social work. Affilia, 28(3), 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109913495730

- McCusker, P. (2013). Harnessing the potential of constructive develop-mental pedagogy to achieve transformative learning in social work education. Journal of Transformative Education, 11(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344613482522

- McKinstry, C., Brown, T., & Gustafsson, L. (2014). Scoping reviews in occupational therapy: The what, why, and how to. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(2), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12080

- Milne, A., & Adams, A. (2015). Enhancing critical reflection amongst social work students: The contribution of an experiential learning group in care homes for older people. Social Work Education, 34(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.949229

- Morley, C. (2020). Stephen Brookfield’s contribution to teaching and practising critical reflection in social work. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Pedagogies for Social Work, 523–535. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002042-43

- Morley, C., Ablett, P., Noble, C., & Cowden, S. (2020). The Routledge handbook of critical pedagogies for social work. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002042

- Morley, C., & Dunstan, J. (2013). Critical reflection: A response to neoliberal challenges to field education?[Article]. Social Work Education, 32(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.730141

- Morley, C., Hodge, L., Clarke, J., McIntyre, H., Mays, J., Briese, J., & Kostecki, T. (2023). ‘This unpaid placement makes you poor’: Australian social work students’ experiences of the financial burden of field education. Social Work Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2161507

- Morley, C., Le, C., & Briskman, L. (2020). The role of critical social work education in improving ethical practice with refugees and asylum seekers. Social Work Education, 39(4), 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1663812

- Morley, C., & Macfarlane, S. (2014). Critical social work as ethical social work: Using critical reflection to research students’ resistance to neoliberalism. Critical and Radical Social Work, 2(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1332/204986014X14096553281895

- Morley, C., & Stenhouse, K. (2021). Educating for critical social work practice in mental health [article]. Social Work Education, 40(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1774535

- Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Khalil, H., Alexander, L., Mclnerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., Peters, M., & Tricco, A. C. (2022). What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 950–952. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-21-00483

- Newcomb, M., Burton, J., & Edwards, N. (2018). Pretending to be authentic: Challenges for students when reflective writing about their childhood for assessment. Reflective Practice, 19(3), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1479684

- Noble, C., Grey, M., & Johnston, L. (2016). Critical supervision for the human services: A social model to promote learning and value-based practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- O’Keeffe, P., & Assoulin, E. (2021). Using creative modalities to resist discourses of individualization and blame in social work education. Social Work Education, 40(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1703935

- Oterholm, I. (2009). Online critical reflection in social work education. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450902930738

- Pack, M. (2013). What brings me here? Integrating evidence-based and critical-reflective approaches in social work education. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 32(4), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2013.32.4.65

- Pack, M. (2014). Practice journeys: Using online reflective journals in social work fieldwork education. Reflective Practice, 15(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.883304

- Patil, T., & Mummery, J. (2020). ‘Doing diversity’in a social work context: Reflecting on the use of critical reflection in social work education in an Australian university. Social Work Education, 39(7), 893–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1722091

- Reimer, E. C., & Whitaker, L. (2019). Exploring the depths of the rainforest: A metaphor for teaching critical reflection. Reflective Practice, 20(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1569510

- Rosen, D., McCall, J., & Goodkind, S. (2017). Teaching critical self-reflection through the lens of cultural humility: An assignment in a social work diversity course. Social Work Education, 36(3), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1287260

- Savaya, R. (2012). Critical reflection training to social workers in a large, non-elective university class. Critical Reflection in Context: Applications in Health and Social Care, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203094662-23

- Testa, D., & Egan, R. (2016). How useful are discussion boards and written critical reflections in helping social work students critically reflect on their field education placements? Qualitative Social Work, 15(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325014565146

- Theobald, J., Gardner, F., & Long, N. (2017). Teaching critical reflection in social work field education [article]. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(2), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1266978

- Tricco, A. C. P. M., Lillie, E. M., Zarin, W. M. P. H., O’Brien, K. K. P. B., Colquhoun, H. P., Levac, D. P. M. B., Moher, D. P. M., Peters, M. D. J. P. M. A., Horsley, T. P., Weeks, L. P., Hempel, S. P., Akl, E. A. M. D. P. M. P. H., Chang, C. M. D. M. P. H., McGowan, J. P., Stewart, L. P. M., Hartling, L. P. M. B., Aldcroft, A. B. A. B., Wilson, M. G. P., Garritty, C. M., & Straus, S. E. M. D. M. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Walker, J., & Gant, V. (2021). Social work students sharing practice learning experiences: Critical reflection as process and method. Practice, 33(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2021.1902973

- Walton, P. (2012). Beyond talk and text: An expressive visual arts method for social work education. Social Work Education, 31(6), 724–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.695934

- Whitaker, L., & Reimer, E. (2017). Students’ conceptualisations of critical reflection. Social Work Education, 36(8), 946–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1383377

- White, S. (2001). Auto-ethnography as reflexive enquiry: The research act as selfsurveillance. In I. Shaw & N. Gould (Eds.), Qualitative research in social work (pp. 100–115). Sage.

- Wiener, D. R. (2012). Enhancing critical reflection and writing skills in the HBSE classroom and beyond. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 32(5), 550–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2012.722183