ABSTRACT

There is an increasing demand for university level qualifications to service the evolving social work workforce in Australia. With many students entering university from non-traditional pathways, it is important to provide support as students transition to higher education. Here, a discipline-specific model is established to support first-year students in the Bachelor of Social Work at a regional Australian university. The 235 students who met with the tutor had on average 7.5% higher assessment marks and 11.5% higher cumulative marks than students who did not meet with the tutor. In addition, students who met with a tutor were more likely to receive a passing grade and to be retained the following year. Feedback from students, the tutor and a unit coordinator describe the positive impact tutoring had on the student experience. Here, we present a scalable model of support that increased students’ confidence, self-efficacy and feedback literacy, and overall improved student success and retention.

Introduction

Social workers provide services in Australia to vulnerable populations and support the physical and mental health of individuals and well-being of communities. They can advocate for individuals in relation to health, poverty, child protection, domestic violence, disability and address other complex social issues. Social work education is crucial in preparing students to navigate a culturally diverse population and landscape in Australia through the development of ethical practices, problem-based learning, and cultural sensitivity. Social work students emerge with the ability to contribute significantly to improving social justice and improving equitable access to support for individuals and communities. However, recent events including the COVID-19 pandemic have increased the number of Australians experiencing hardship and increased the social worker workforce demand. While there are current strategies in place to increase the number of qualified social workers and to attract and retain social workers (Scarfe et al., Citation2022), there is also a need to increase the support offered to students studying social work to succeed at university and move into the profession. First-year social work students have reported higher anxiety and stress levels than second-year students (Stanley & Mettilda Bhuvaneswari, Citation2016). Therefore, social support as well as academic support is required to increase the well-being and resilience of commencing students (Grant & Kinman, Citation2012). Social work education needs to be responsive to the profession, and address both competencies and techniques as well as developments of professional judgment based on theoretical frameworks (Singh & Cowden, Citation2009).

Tutor support in higher education can improve the student experience in the transition to the first year of university (Court, Citation2014; McKevitt, Citation2016). Engaging students with tutors who have professional experience enables the students to see how knowledge is applied by skilled professionals. Tutoring programs that increase access to meaningful feedback for students have demonstrated improved grades (Burgess et al., Citation2016). Programs also have a positive impact on tutors, such as increased opportunities for professional development, increased content knowledge and improved teaching practices (Williams & Fowler, Citation2014). Despite the evidence supporting the positive impact of tutoring programs, specific information on the model of delivering support is not often provided in detail. Best teaching pedagogy applied to tutoring employs multiple educational theories and frameworks, most notably social constructivism. The concept of ‘cognitive congruence’ assumes that the tutor and the student have a level of understanding closer than an academic and student, which allows the tutor to bridge the gap in understanding (Yew & Yong, Citation2014). This relates to the concept of Vygotsky’s ‘zone of proximal development’ in which a student learns better from a teacher with a relatable level of understanding (Vygotsky, Citation1978). Further research on established tutoring practices is needed to investigate whether the socioemotional support provided by tutors is equally as important to students as academic skills.

Students begin to develop their feedback literacy in their commencing year of study. Engagement with feedback can be encouraged by providing meaningful interactions and effective feedback on assessments (Henderson et al., Citation2021). However, the timing of feedback is critical for students as it enables them to process and incorporate the feedback. Various forms of technology-enhanced feedback are used to provide individualized and adaptive feedback for students, including feedback provided via audio and video (Carruthers et al., Citation2015; Henderson & Phillips, Citation2015; Hennessy & Forrester, Citation2014; Lunt & Curran, Citation2010). Several studies have shown that feedback provided on a submitted assessment can be used by students in learning experiences and future assessments (Boud & Molloy, Citation2013; Dawson et al., Citation2019; Hounsell et al., Citation2008). Providing feedforward to students in preparation of assessments, which allows them to incorporate suggested improvements into their work prior to submission, is a highly effective form of feedback (Boud & Molloy, Citation2013; Court, Citation2014; Hendry et al., Citation2016). It is crucial to provide students with equal opportunities to engage with effective feedback (Henderson et al., Citation2019; Ryan et al., Citation2019; Winstone et al., Citation2017). However, providing individualized support to students can be an immense challenge for unit coordinators due to schedules, large class sizes and restricted academic workload.

Supporting and retaining students are not new challenges in higher education. It is essential to engage and support students as they transition to university (Kift, Citation2015), and increased student engagement can have positive effects on student experience and student retention (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). In 2020, there was a rapid and significant shift to online learning (Dhawan, Citation2020; Smith & Kaya, Citation2021) and the use of innovative learning technologies (Dhawan, Citation2020). Online study benefits both the institution and the student, by offering increased flexibility and a better work-study balance (Turan et al., Citation2022). However, students studying online often do not have the same opportunities for meaningful interactions and support from peers and educators, and attrition is highest in courses offered entirely online (Greenland & Moore, Citation2014) and in first-year (Norton & Cherastidtham, Citation2018). In addition, a study regarding student engagement in first-year reported a significant decrease in emotional engagement in relation to online study in contrast to traditional face-to-face learning (Salta et al., Citation2022). Higher education institutions now have the opportunity to reflect on the role of online teaching and support post-pandemic. As participation in online study is unlikely to revert to pre-pandemic levels, it is essential for higher education institutions to develop innovative and sustainable ways to promote student engagement and retention using online technologies.

At our regional Australian university, the Bachelor of Social Work course is offered online, on campus or via blended delivery. Of the social work students enrolled in 2022, 85% of students were female, 81% were studying entirely online and the median age was 27 years old. Of the students in the 2022 cohort, the entry pathways to the degree included students coming from vocational education training (49%), university (28%), secondary education (18%), or other pathways not listed (5%). The next hurdle presented for commencing students post-pandemic is the increased cost of living. Many students are juggling various other roles such as primary income earner and/or primary caregiver. Therefore, personal and professional work-life balance whilst studying is highly valued. A critical aspect of accreditation of curriculums in higher education institutions is the ability to produce workplace-ready graduates. Social work education plays a critical role in helping students develop a professional identity as a social worker (Bruno & Dell’aversana, Citation2018; Wiles, Citation2022) and students should emerge with developed skills in communication and advocacy. However, it is difficult for students to improve these critical skills without opportunities to practice and reflect with peers and educators.

In 2020, our research group identified an opportunity to support students through an innovative and online approach to providing feedback, enabling equal access to support for students irrespective of their location or mode of study. We piloted a program in which tutors with unit-specific knowledge were embedded into key first-year units to provide feedforward on a draft written assessment (Linden et al., Citation2022). In 2022, the program was expanded to a scalable and sustainable university-wide Embedded Tutor Program (Teakel et al., Citation2023). In addition, our online model of support allowed for the recruitment of tutors with relevant expertise who are not restricted to meeting with students on a particular campus. Here, we evaluate the impact of appointing a full-time discipline-specific tutor, providing assessment support across first-year units in the Bachelor of Social Work, on student success and unit progress rates, perceived student confidence and student experience.

Methods

Embedding a discipline-specific tutor

A tutor was nominated by the unit coordinators to support students across the first year of the Bachelor of Social Work. The tutor had 12 months of experience as a sessional academic and 10 years of professional experience working across various fields of practice including child protection, housing, disability, foster care and juvenile justice. The tutor was provided with training and access to online self-paced training modules that covered topics such as providing personalized guidance and fostering strategies to promote healthy and effective study habits of students. The tutor training is based on transition pedagogy (Kift, Citation2015) and the pedagogy of kindness (Gilmour, Citation2021) principles. Weekly online drop-in meetings with discipline-specific embedded tutors from other disciplines were also held to facilitate collaboration. Discussions were often centered around the additional support some students needed in developing essential academic skills, such as concept mapping, assessing the suitability of sources, linking ideas to theoretical concepts and constructing logical arguments.

The tutor sessions were available in six units offered on multiple campuses and online (17 unit offerings in total across three semesters in 2022). These units introduce students to foundational theory and practice methods in social work. The learning objectives are designed to promote reflection on professional values, ethics, and communication and students are required to reflect on professional values, motivation and influence professional communication, examine moral, legal, political and ethical dilemmas, and methods of intervention that may arise in different fields of human service practice. Students also develop an understanding of the various factors that impact socioeconomic disadvantage.

Specifically, the communication and Human Services unit integrates concepts of being, thinking and doing, and provides learning experiences over a range of topics with a focus on communication on personal, social, organizational, political, and even spiritual levels. Units address the core values and ethics of social work, introduce the social work profession and the human services sector as well as providing an overview of some fields of practice in social work. The foundations in social policy, provides a historical perspective on political social policy debates that helps students to understand contemporary developments in which social provisions are distributed and social conduct is regulated. Many students find the subject challenging, or do not consider themselves politically minded until it is related to social issues that they are passionate about. The law unit has a strong focus on learning objectives relevant to the human services sector such as privacy, confidentiality, a duty of care, negligence, and civil liability. This unit has emphasis on application of legal principles and real-world legal issues they could face as practitioners. The need for advocacy of human rights for vulnerable populations is highlighted. Fostering meaningful learning outcomes is imperative for graduates to emerge with a satisfactory understanding of legal and ethical responsibilities and the potential legal consequences of poor practice.

Ethics approval was received from the Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Protocol No H21170 and H22085). A total of 1121 students were enrolled in the selected units, which are key foundational units with a large proportion of commencing students. The most common types of assessment were reflective essays, reports and theoretical research papers, and were each worth 20–60% of the overall cumulative mark. In addition to providing feedforward on assessments, the tutor also assisted students in understanding the task requirements and marking rubrics, supported decision-making in developing hypotheses and provided additional guidance to students where appropriate regarding academic skills including research, writing and referencing skills. In addition, the tutor sessions created opportunities to provide an educative approach to supporting students who had a suspected case of academic misconduct.

The tutor attended the first online class each semester to explain the purpose, accessibility and benefits of the support, and provide students with a warm introduction. Students were encouraged to book a tutor session in the approximately 2 weeks before an assessment was due via an online booking system (Calendly) embedded into the Learning Management System (LMS, Blackboard). In addition, students could book in with the tutor at any time during the semester and the unit coordinator referred students to the tutor for additional support. Online announcements were made via the LMS leading up to assessment due dates during the semester to remind students about the availability of support. The tutor attended lectures and tutorials relevant to the assessment before commencing tutor sessions, participated in the online discussion boards in the LMS and provided feedback to unit coordinators. This model also provided a consistent workload for the tutor whereby assessment support was staggered across multiple units each semester.

Data collection and analysis

Students who participated in the Program were emailed a link to a voluntary, anonymous online survey (Survey Monkey). The survey consisted of 10 questions in which students were asked to indicate their level of confidence before and after the tutor session on a sliding scale of 0 to 10, and to rate their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ regarding whether the tutor sessions helped their overall learning/motivation/understanding, supported the identification of priorities for learning, and how engaging they found the tutor sessions. Students were also asked three open-ended questions regarding their experience with the Embedded Tutor Program: What did you like most about the Embedded Tutor Program, What aspects of the Embedded Tutor Program could be improved, and Anything else you would like to tell us about your experience with an embedded tutor. An NVivo 12 thematic qualitative analysis of the student feedback identified several themes. Improvements to the Program were made following reflection on the feedback provided. The surveys were used to recruit students for voluntary participation in an interview with our research assistant. Students were prompted to provide their contact details (e-mail address and/or phone number). All responses were de-identified prior to sharing with the research team and analysis. The tutor completed a form after they met with each student in which they indicated the student’s unique identification number, the assessment item number and rated the student’s perceived level of confidence regarding the assessment before and after a tutor session on a sliding scale from 0 to 10. The tutor and unit coordinators were invited to provide a reflective statement at the end of the semester.

The assessment marks and the cumulative marks (out of 100) were downloaded from the LMS grading platform (Grade Centre). All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.2 (GraphPad Software). All zero grades awarded to students who did not submit any assessments were removed prior to analysis. A Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to determine the statistical significance between the grade distribution of students who met with the tutor to students who did not meet with the tutor. Using the survey results, a paired student t-test was used to assess the difference in assessment and cumulative marks, and the change in students’ perceived confidence after the tutor session from the perspectives of the student and the tutor. A z-score test for two population proportions was conducted to determine the difference in progress rate for students who met with a tutor and those who did not. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Engaging students with a tutor

In 2022, there were a total of 1689 enrollments in the social work units, which consisted of 1121 unique students. The embedded tutor conducted a total of 417 tutor sessions with 235 students, and 25% of students accessed the tutor in more than one unit. The median age of students who met with the tutor was 32, comparatively, students who did not meet with the tutor had a median age of 26. Students who enrolled in the Bachelor of Social Work through the vocational education training pathway were more likely to access tutor support than students from all other entry pathways; 60% of students who met with the tutor were from the vocational education training (compared to 45% of total enrolled).

Increased student confidence

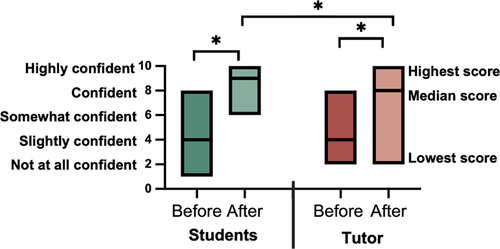

Both tutors and students indicated an increase in students’ confidence following a tutor session using the confidence sliding scale and in open-ended survey responses. Students commented, ‘Having someone to talk to about the assessment helped me in consolidating my learning and gave me confidence that I was on the right track with my assessments’ and ‘[Tutor] had prior knowledge of what was expected and built my confidence’. The spread of responses from students and the tutor regarding the student’s level of confidence before and after a tutor session are displayed as box plots in . There was a significant increase in perceived student confidence levels from the perspective of both students and the tutor (p < 0.002). Students indicated a significantly higher confidence score following the tutor session that the tutor had indicated (p < 0.002). Before the tutor session, students consistently reported a confidence level ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 8 (confident) out of 10, with a median score of 4 (slightly confident). Following the tutor session, students reported a significant increase in confidence level ranging from 6 (somewhat confident) to 10 (highly confident), with a median score of 9. The tutor observed the students’ confidence level at the start of the tutor session ranging from 2 (not at all confident) to 8 (confident), with a median score of 4. Following the tutor session, the tutor responses also showed a significant increase in confidence level ranging from 2 (not at all confident) to 10 (highly confident), with a median score of 9. Occasionally, the tutor perceived the student’s level of confidence to be equally low following the tutor session.

Enhanced online learning experience

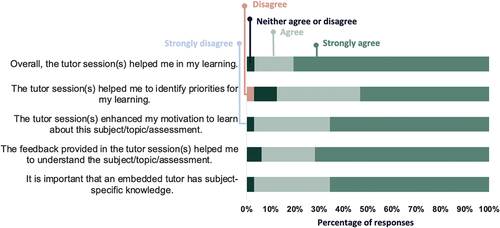

Of the 30 students who completed the student feedback survey, 97% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘Overall, the tutor session(s) helped me in my learning’ (). In addition, 88% of students reported that ‘The tutor session(s) helped me to identify priorities for my learning’, however, a small number of students (3%) disagreed with this statement. In response to the statements ‘The tutor session(s) enhanced my motivation to learn about this subject/topic/assessment’ and ‘It is important that an embedded tutor has subject-specific knowledge’, 66% of students strongly agreed and 31% of students agreed. Students also commented on how the tutor sessions increased their motivation to complete their assessment. Feedback included that ‘It was amazingly helpful to have someone to discuss ideas and concepts with. It allowed me to clarify and reinforce my learnings and I left every session with clarity and motivation’ and ‘[Tutor] was excellent—pushed me really hard and provided thought provoking feedback’. Despite the tutor sessions being held completely online, 75% of students strongly agreed and 22% agreed with the statement ‘My experience with an embedded tutor was engaging’.

Figure 2. Students’ responses to 5-point Likert style questions in the feedback survey regarding their experience with the tutor. Students (n = 30) indicated whether they strongly disagreed (left) to strongly agreed (right) with five statements regarding their experience with the tutor in the social work units.

Various themes arose from the thematic analysis of the student feedback provided in the online survey including kind and meaningful interactions, desirable tutor attributes, enhanced online experiences, increased student confidence, improved motivation, and increased demand for support. Students’ open-ended responses to the feedback survey demonstrated that the Program enhanced online learning experiences: ‘The embedded tutor program was a huge part of my learning and enhanced my experience immensely. It provided a critical link with the university that would otherwise have been missed through online learning’ and ‘[I] cannot share in words how invaluable this program is for online University’. Students liked that the tutor improved their comprehension of content, clarified the assessment and provided guidance, discussed ideas, reinforced learning and provided personalized feedback. Students also indicated that the Program enhanced their university experience and exceeded their expectations referring to the Program as ‘the best support service at the University’.

Students used the feedback survey to comment on the personal attributes of the tutor, highlighting the value held by students in meaningful and kind interactions characteristics of their tutor: ‘The tutor was very friendly and made me feel comfortable. It allowed me to have a conversation with someone prior to submitting the assignment which reduces the sense of isolation’. Students described the tutor as direct, honest, friendly, approachable, professional, efficient and generous with their time. Students liked ‘feeling more confident and motivated’ and that the tutor had ‘unit-specific knowledge and expertise’, and acknowledged the potential positive impact the tutor may have on future learning: ‘I found both the positive feedback and positive criticism very important in my learning process for the subject and for the future’. Unexpectedly, students occasionally reported that the tutor was able to help in the context of mental health-related barriers to learning including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and expressed gratitude for supporting their diverse learning needs: ‘I can’t begin to explain how this helped me. I have ADHD and very real problems with learning/focus and time management. ADHD becomes very apparent during assessments. Without this program, I’d probably have struggled to understand what to do or how to improve and continued to internalize negative ideas about myself as a learner. This program is one of the best things about [the University]’.

Students expressed an increased appetite for this type of one-on-one, individualized support and stated their intention to use tutors where possible in the future: ‘I wasn’t sure about the value of a tutoring session before, but I would always try and use one in the future.’ Students requested longer session times, more availability, support available for more assessments and all units, additional time to review the draft assessment outside of consultation time, and more allotted time for students with disabilities. One student commented ‘I had a great experience with the program, I only wish it was available earlier in my degree. Being able to talk things through really suits my learning style’. Students indicated a preference for sessions outside of business hours, increased capacity to accommodate different time zones, and increased flexibility. Students liked the availability and the ease of booking appointments. Other students took the opportunity to comment that nothing could be improved and that they appreciated and valued the support.

Increased student success and retention

Students who met with the tutor on average achieved a significantly higher assessment mark (7.1%, p < 0.05) than the students who did not meet with the tutor. Students who met with the tutor at any point during the semester achieved a significantly higher overall cumulative unit mark (11.5%, p < 0.05) higher than the students who did not meet with the tutor. Students from vocational education training pathway who met with a tutor had on average 12% higher cumulative marks than students from a vocational education training pathway who did not meet with the tutor. Students who were admitted through work and life experience were the least likely to access tutor support.

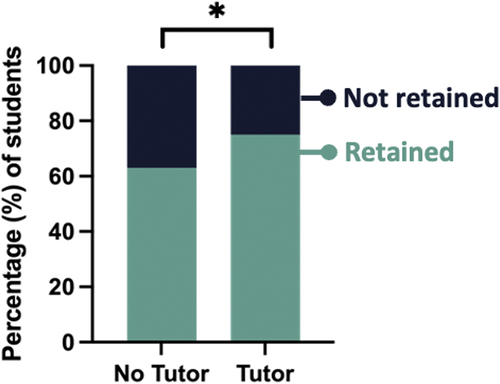

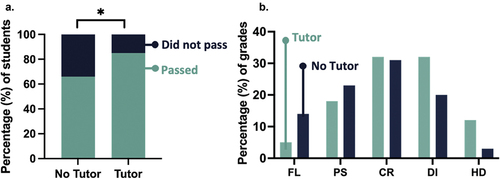

Students who met with a tutor were significantly more likely to pass the unit than those who did not (progress rate of 85% vs 66%, p < 0.05 ). There was a significant shift in the grade distribution for the 313 grades from students who met with the tutor in comparison with the 1375 grades from students who never met with the tutor for feedback on a draft assessment (). Students who met with the tutor received fewer Fail (FL) and Pass (PS) grades, and more Distinction (DI) and High Distinction (HD) grades.

Figure 3. Progress rates and grade distribution of students who met with a tutor. a. The percentage of students who met with the tutor (tutor) that passed in comparison with students who passed without tutor support (no tutor). b. The grade distribution of students who met with the tutor (tutor) in comparison with students who did not meet with the tutor (no tutor), *p < 0.05.

Of the 235 students who met with the tutor in 2022, 176 students (75%) were retained (enrolled in at least one unit in 2023) and 59 students were not retained (no active enrollment in semester 1 2023) (). In comparison, of the 886 students who did not meet with the tutor, 558 students (63%) were retained, and 328 students (37%) were not retained.

Understanding and adapting to the challenges of supporting social work students online: a reflection from the discipline-specific embedded tutor

Participating in the Program allowed for increased opportunities to identify students that required additional support. Students with a draft assessment below a satisfactory standard often misinterpreted the assessment task requirements or had a lack of knowledge about effective assessment planning. Students who accessed support early in the semester self-reported anxiety associated with their ability to comprehend and engage with legal content. However, these students who present with self-awareness are evidently motivated to seek support. Still, students often questioned the relevance of the legal unit to their professional practice and needed to be persuaded of the significance of the unit content to practice.

Reflecting on the characteristics of the student cohort, a prevailing theme was students who were concerned with their ability to manage the pressures of daily work and caring responsibilities in addition to their study load. Another theme was a self-reported lack of confidence in engaging in political discourse. Students were engaged in reflection about personal values and assisted in identifying social issues that resonate with them; to form a foundation for critical thinking about wider social change and motivation that was anchored to a problem connected to the intrinsic values and beliefs of the individual student. This approach was used to engage in deep learning about social policy and its impact on service delivery.

Approaching the student with curiosity and engaging the student in reflective discussion fostered student self-awareness of personal biases, increased students’ ability to consider multiple perspectives, and created opportunities to practice respectful persuasive political discourse around sensitive topics. Students who attended a tutor session reported feeling increased confidence following reflective discussions with a tutor well-versed in legal issues that can arise in practice.

The Program has provided invaluable opportunities for professional growth early in my academic career and helped to improve teaching skills; through challenges, practice and reflection. This was enhanced by participation in an online professional development series on teaching methodologies. Opportunities to engage with both more experienced academics and other inexperienced academics reduced performance anxiety and feelings that arise from imposter syndrome.

A collaborative experience with an embedded tutor: a reflection from a unit coordinator

Having a tutor embedded in the demanding law for the human services unit has been very beneficial. Grades of the students who have undertaken a session or two with our assigned tutor have been higher overall, and I have heard numerous anecdotal reports from students of how much her advice has calmed their nerves, helped them to tackle essay questions, and research confidently. I have also benefitted from having a second pair of eyes to look at suspected cases of plagiarism. The benefit I would like to comment on most of all though is the weight it has taken off my shoulders in the process of trying to accommodate and be flexible with struggling students. When you’ve got so much to do, it can be difficult as a lecturer and Course Convenor to find the time to offer detailed feedback for essay papers where the student is very much off the mark and below standard. Having the tutor onboard has enabled me to just offer a few main points of concern to a student via email, then refer them to the tutor for a compulsory session for a more detailed reflection on what needs to improve. The reflective discussions and the practical solutions the tutor offered led to strong improvements when students resubmit their essays (for a pass of 50%), or when taking onboard feedback for future essay submissions. If a student has been a borderline fail/pass, attending a compulsory tutor session gives me confidence in converting the grade to a pass, knowing that they have reflected on their mistakes. In the first semester, there was an occasional case of students receiving conflicting advice from the tutor regarding expectations/guidelines for essays and referencing. The tutor and I reflected on each case, and it led to solutions; most notably, the weekly review of recorded lectures so that the tutor can be aware of what I have shared with students in class. Overall, the Embedded Tutor Program has been a highly positive experience.

Discussion

Support in the first year of study is key for student retention in higher education (Kift, Citation2015; Nelson et al., Citation2012), and tutor support is highly impactful in the context of improving the student experience (Court, Citation2014; McKevitt, Citation2016) and student success (Burgess et al., Citation2016). Tutors in the Embedded Tutor Program provide one-on-one, just-in-time online support to commencing students by offering feedforward on written assessments. In 2022, students who met with the discipline-specific embedded tutor in social work units (n = 235) had significantly higher assessment marks and higher overall cumulative marks than the students who did not. Here, we report improved student confidence from the perspective of both the students and the tutor, enhanced online learning experiences and increased student success. In addition, students who met with the tutor were more likely to be retained and re-enroll in 2023. A common barrier to effectively supporting students studying online is creating opportunities for meaningful interactions (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). We propose that providing opportunities for students to access meaningful feedback, and associated development of feedback literacy (Carless & Boud, Citation2018; Edwards et al., Citation2017), has increased student retention.

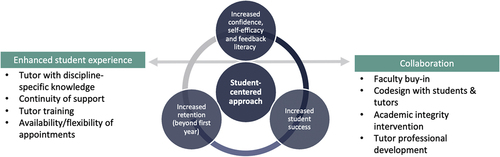

It is important to appreciate that students may experience challenges during the transition to university study. Evans et al. (Citation2021) highlighted the importance of improving support and communication for social work students to support students’ well-being so that they can be retained at university. Here, we show that embedding a discipline-specific social work tutor in key compulsory commencing units in the undergraduate Bachelor of Social Work is a transformative model of support (). The embedded tutor provides individualized support to students in their time of need in the preparation of a written assessment. As demonstrated in this study, upscaling this model of support to be offered across an entire course has the potential to increase course-level progress rates in a course where retention rates are historically low. Key to our model is cross-institutional collaboration to enhance the student experience. The key components of the model are discussed in detail below.

Enhanced student experience

A tutor with discipline-specific knowledge

It has been reported that students have a perceived disconnect between the skills that are needed in social work practice and the theories behind the skills that enable them to promote social justice (Bhuyan et al., Citation2017). The tutor had experience working in the social work profession to affirm their expertise and currency of knowledge, and actively used recent and relevant professional experiences to contextualize theories into practical applications for students. Students valued this discipline-specific knowledge as shown by 97% agreeing that subject-specific knowledge is important and open-ended responses. Research into educational approaches that are most effective for adult learners has determined that they are motivated by assessment tasks and receptive to teaching strategies that are problem-based and applied to practice (Khalil & Elkhider, Citation2016). The tutor leveraged theoretical knowledge and practice experience in the sector to motivate students and support students with problem-based learning, identifying personal biases and gaining a better understanding of theoretical limitations in practice. A sense of professional identity that encompasses belonging to a professional community and sense of professional self is something that is often established in the later years of a social worker’s career (Bruno & Dell’aversana, Citation2018; Wiles, Citation2022). However, meeting with a tutor can contribute to first-year students’ emerging sense of professional identity. The tutor supported students by linking concepts to students’ personal or professional values, and real-life experiences while assisting students to identify practical real-world solutions to problems. It has also been reported that students have limited opportunities to apply social justice theory prior to commencing in the social work profession (Bhuyan et al., Citation2017). The tutor provided students with a ‘safe space’ to practice persuasive and respectful advocacy around social justice (Lerner & Fulambarker, Citation2018). The experience and currency of knowledge that the tutor held were therefore highly valued by both the academic teaching staff and students.

Increased continuity of support

Embedding a tutor across a course increased continuity of support for students and the tutor was exposed to a broad cross-section of first-year undergraduate students and was accessed by returning students, including across several units. The tutor was strategically positioned to bridge the gaps between students and academics in a specific course. The tutor was able to develop a rapport with the student cohort as a result of increased social and cognitive congruence (Yew & Yong, Citation2014). The perceived increase in cognitive congruence was a result of individualized support in which the tutor could adapt their response to the student’s level of understanding and individual learning style and engage in interactive discussion. This was evident in the student feedback comments regarding the tutor adapting to the student’s learning style. This cannot be achieved in a lecture in which a one-way dialogue is occurring.

Providing tutor training

Tutor training and collaborative meetings reduced reported anxiety and feelings of ‘imposter syndrome’, which is often experienced by early career academics (Wilkinson, Citation2020). Tutors were encouraged through training and meetings to approach students with a pedagogy of kindness (Gilmour, Citation2021). Meeting students where they are at in their learning journey was a strong theme in training sessions. The importance of this was evident in the student feedback surveys in which students commented on key tutor attributes that enhanced their experience including friendliness, understanding and kindness.

Increased availability and flexibility of appointments

Online learning offers flexibility in teaching and learning, and can be beneficial to staff and students (Turan et al., Citation2022). Enhanced accessibilityfacilitated student engagement with tutor support. The success of the Program can be further attributed to the flexibility in tutor session times (including after-hours and weekends), reduced travel time and shared workspace requirements, and overall capacity to provide accessible support irrespective of location or mode of study. All these factors contribute to a better work-study balance (Turan et al., Citation2022), which is highly valued by students particularly regarding support for online learning as demonstrated by the student feedback.

Collaboration

The importance of faculty buy-in

The faculty and institutional involvement and support for the Program, and developing a student-centered approach fostered by collaboration have been key to success. One-on-one interactions with students have previously been reported to enable tutors to access early insights into the common challenges and potential barriers to learning that students are experiencing (Brown, Citation2020). In this study, the tutor provided feedback to the unit coordinators on barriers to engagement or motivation to learn, which was incorporated in real-time rather than at the end of the semester when the subject experience surveys are released and reviewed. This allowed the current cohort of students, as well as future cohorts of students, to benefit.

An intervention for academic integrity

The support for enhanced academic integrity developed organically based on student feedback to tutors. As Sefcik et al. (Citation2020) have previously described, an educative approach should be collaboratively designed and incorporate learner feedback and focus on underpinning values. Rather than having a punitive or dismissive approach, the tutor has afforded the time for a one-on-one discussion in which the students were assisted with completing assessments, conducting research and referencing appropriately. As the number of students who illicitly use automated paraphrasing tools and generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools to shape written work continues to rise (Cotton et al., Citation2023; Roe & Perkins, Citation2022; Sullivan et al., Citation2023), the role of the tutor in educating and supporting students will become increasingly important. The initial reaction of some higher education institutions was a ban on the use of generative AI tools. However, a recent report found that university students tend to use AI tools as a learning support tools rather than to cheat (Ziebell & Skeat, Citation2023).

Codesign with tutors and students

Traditionally, tutors are not often expected to be content experts or to contribute to curriculum development or assessment design. Therefore, tutors are reluctant to provide unsolicited comments on curriculum (Brown, Citation2020). In contrast, students are often consulted for input on curriculum and assessment design (Brown, Citation2020; Reneland-Forsman, Citation2016). It has previously been acknowledged that ‘tutors are an under-utilized resource when it comes to curriculum development’ (Brown, Citation2020), p. 21). In this study, the tutor was consulted to provide feedback on assessment design (which undergoes constant improvement) and participate in discussions regarding the moderation of assessments. The unit coordinators indicated that this reduced their cognitive load by having support when revising assessments and incorporating student feedback into assessment design.

Tutor professional development opportunities

Tutoring programs can benefit both students and the tutor (Burgess et al., Citation2016; Williams & Fowler, Citation2014). Providing tutoring support can be seen as a stepping stone to teaching at university and other tutoring programs have reported increased opportunities for professional development (Williams & Fowler, Citation2014). In this study, the tutor reported that participation in the Program provided opportunities that positively impacted professional growth such as attending an online professional development series for teaching working collaboratively with teaching academics, and improving teaching strategies.

Limitations

Despite the evidence for increased student success and retention, uptake of tutor sessions could be improved to be above 23% of students. Some reasons students do not access support services include lack of time, or not being able to see themselves as someone who may need support (Picton & Kahu, Citation2022). Further research is needed to investigate the reasons students did not access tutor support, particularly for students who were identified as at risk of failing and students from different age cohorts. Several students who were contacted and encouraged to book a tutor session did not meet with a tutor, submitted the assessment, and did not receive a pass. Strategies to identify and target the students who need the support the most will continue to be assessed and improved by working closely with unit coordinators, the Outreach Team and other support services at the University.

Conclusion

In response to challenges that social work students face in the transition to university and with increased student diversity, higher education institutions need to develop innovative and sustainable ways to promote student engagement and retention using online technologies, The changing landscape of the social work profession also necessitates specialized and adaptive support for student cohorts who are both experiencing adversity and learning to support the wider community. Here, we describe a framework for introducing a discipline-specific, course-associated online embedded tutor to increase student success in an undergraduate Bachelor of Social Work course at an Australian regional university. The tutor helped to bridge the gap between theory and practice for first-year students. Ongoing tutor support to increase students’ confidence, self-efficacy and feedback literacy will improve overall student retention and future progress rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the academics from the Retention Team and the School of Social Work and Arts who have supported the Program. In particular, thank you to Neil van der Ploeg and Wendy Rose Davison.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ST, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bhuyan, R., Bejan, R., & Jeyapal, D. (2017). Social workers’ perspectives on social justice in social work education: When mainstreaming social justice masks structural inequalities. Social Work Education, 36(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1298741

- Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

- Brown, P. R. (2020). What tutors bring to course design: Introducing political and policy theories to disengaged students. Teaching Public Administration, 38(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739419858682

- Bruno, A., & Dell’aversana, G. (2018). ‘What shall I pack in my suitcase?’: The role of work-integrated learning in sustaining social work students’ professional identity. Social Work Education, 37(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1363883

- Burgess, A., Dornan, T., Clarke, A. J., Menezes, A., & Mellis, C. (2016). Peer tutoring in a medical school: Perceptions of tutors and tutees. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 85–85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0589-1

- Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

- Carruthers, C., McCarron, B., Bolan, P., Devine, A., McMahon-Beattie, U., & Burns, A. (2015). ‘I like the sound of that’ - an evaluation of providing audio feedback via the virtual learning environment for summative assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 352–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.917145

- Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148

- Court, K. (2014). Tutor feedback on draft essays: Developing students’ academic writing and subject knowledge. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.706806

- Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: Staff and student perspectives. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

- Edwards, R., Bybee, B. T., Frost, J. K., Harvey, A. J., & Navarro, M. (2017). That’s not what I meant: How misunderstanding is related to channel and perspective-taking. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X16662968

- Evans, E. J., Reed, S. C., Caler, K., & Nam, K. (2021). Social work students’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and themes of resilience. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(4), 771–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1957740

- Gilmour, A. (2021). Adopting a pedagogy of kindness. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (22). https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi22.798

- Grant, L., & Kinman, G. (2012). Enhancing wellbeing in social work students: Building resilience in the next generation. Social Work Education, 31(5), 605–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.590931

- Greenland, S. J., & Moore, C. (2014). Patterns of student enrolment and attrition in Australian open access online education: A preliminary case study. Open Praxis, 6(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.95

- Henderson, M., & Phillips, M. (2015). Video-based feedback on student assessment: Scarily personal. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1878

- Henderson, M., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Molloy, E., & Mahoney, P. (2019). Conditions that enable effective feedback. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(7), 1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1657807

- Henderson, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Phillips, M., Molloy, E., & Mahoney, P. (2021). The usefulness of feedback. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787419872393

- Hendry, G. D., White, P., & Herbert, C. (2016). Providing exemplar-based ‘feedforward’ before an assessment: The role of teacher explanation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416637479

- Hennessy, C., & Forrester, G. (2014). Developing a framework for effective audio feedback: A case study. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(7), 777–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.870530

- Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research and Development, 27(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658765

- Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Khalil, M. K., & Elkhider, I. A. (2016). Applying learning theories and instructional design models for effective instruction. Advances in Physiology Education, 40(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00138.2015

- Kift, S. (2015). A decade of transition pedagogy: A quantum leap in conceptualising the first year experience. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2, 51–86. https://www.herdsa.org.au/herdsa-review-higher-education-vol-2/51-86

- Lerner, J. E., & Fulambarker, A. (2018). Beyond diversity and inclusion: Creating a social justice agenda in the classroom. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 38(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2017.1398198

- Linden, K., Teakel, S., & Van der Ploeg, N. (2022). Improving student success with online embedded tutor support in first-year subjects: A practice report. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.2338

- Lunt, T., & Curran, J. (2010). ‘Are you listening please?’ The advantages of electronic audio feedback compared to written feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930902977772

- McKevitt, C. T. (2016). Engaging students with self-assessment and tutor feedback to improve performance and support assessment capacity. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 13(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.13.1.2

- Nelson, K., Kift, S., & Clarke, J. (2012). A transition pedagogy for student engagement and first-year learning, success and retention. In P. Petocz, and I. Solomonides (Eds.), Engaging with learning in higher education (pp. 117–144). Libri Publishing.

- Norton, A., & Cherastidtham, I. (2018). Mapping Australian higher education 2018. https://grattan.edu.au/report/mapping-australian-higher-education-2018/

- Picton, C., & Kahu, E. R. (2022). ‘I knew I had the support from them’: Understanding student support through a student engagement lens. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(6), 2034–2047. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1968353

- Reneland-Forsman, L. (2016). Participating with experience—A case study of students as co-producers of course design. Higher Education Studies, 6(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v6n1p15

- Roe, J., & Perkins, M. (2022). What are automated paraphrasing tools and how do we address them? A review of a growing threat to academic integrity. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-022-00109-w

- Ryan, T., Henderson, M., & Phillips, M. (2019). Feedback modes matter: Comparing student perceptions of digital and non-digital feedback modes in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1507–1523. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12749

- Salta, K., Paschalidou, K., Tsetseri, M., & Koulougliotis, D. (2022). Shift from a traditional to a distance learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: University students’ engagement and interactions. Science & Education, 31(1), 93–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00234-x

- Scarfe, A., Chu, C., & Szeker, D. (2022). 2022-2023 Australian budget priorities AASW submission. Retrieved from: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-03/258735australianassociationofsocialworkers.pdf

- Sefcik, L., Striepe, M., & Yorke, J. (2020). Mapping the landscape of academic integrity education programs: What approaches are effective? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1604942

- Singh, G., & Cowden, S. (2009). The social worker as intellectual. European Journal of Social Work, 12(4), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450902840689

- Smith, E. K., & Kaya, E. (2021). Online university teaching at the time of COVID-19 (2020): An Australian perspective. IAFOR Journal of Education, 9(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.9.2.11

- Stanley, S., & Mettilda Bhuvaneswari, G. (2016). Stress, anxiety, resilience and coping in social work students (A study from India). Social Work Education, 35(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1118451

- Sullivan, M., Kelly, A., & McLaughlan, P. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.17

- Teakel, S., Linden, K., van der Ploeg, N., & Roman, N. (2023). Embedding equity: Online tutor support to provide effective feedforward on assessments. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2232955

- Turan, Z., Kucuk, S., & Cilligol Karabey, S. (2022). The university students’ self-regulated effort, flexibility and satisfaction in distance education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 35–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00342-w

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In Gauvian & Cole (Eds.), Readings on the development of Children (pp. 34–40). Scientific American Books.

- Wiles, F. (2022). Revisiting social work professional identity in the light of the impact of COVID-19. Social Work Education, ahead-of-print(ahead–of–print), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2146087

- Wilkinson, C. (2020). Imposter syndrome and the accidental academic: An autoethnographic account. The International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1762087

- Williams, B., & Fowler, J. (2014). Can near-peer teaching improve academic performance? International Journal of Higher Education, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v3n4p142

- Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2017). ‘It’d be useful, but I wouldn’t use it’: Barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-On-Thames), 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

- Yew, E. H. J., & Yong, J. J. Y. (2014). Student perceptions of facilitators’ social congruence, use of expertise and cognitive congruence in problem-based learning. Instructional Science, 42(5), 795–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9306-1

- Ziebell, N., & Skeat, J. (2023). How is generative AI being used by university students and academics? Semester 1, 2023. Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne.