ABSTRACT

In Aotearoa New Zealand, approximately 3000 people are enrolled in a recognized social work education programme at any one time. A collaboration between researchers at two social work education providers sought to understand the experiences of student financial hardship, and its impact on wellbeing, amongst current social work students and recent graduates. In total, 346 students and recent graduates participated in a survey that gathered information Glossary of te reo Māori terms regarding financial circumstances, caring responsibilities, mental health and social wellbeing. As social work qualifications require a significant component of unpaid field education, this study reflects growing interest in the financial impact of studying for a social work qualification. This article explores some of the findings with particular focus on the impact of financial hardship on mental and social wellbeing. In particular, the study found that nearly one in four respondents reported experiencing moderate or severe financial hardship while studying, and that this had a significant impact on their mental and social wellbeing. In addition, those with caring responsibilities, especially accumulative caring responsibilities for children and others, were more likely to experience financial hardship. These results add weight to the call for greater support for those preparing to enter the social work workforce.

Introduction

Prior to commencing tertiary education, students need to decide how they will be able to support themselves financially for the duration of their studies. In Aotearoa, New Zealand (hereafter Aotearoa), students can apply for a student loan that covers tuition and, if needed, a student allowance if they come under the threshold with means-testing for income and meet other eligibility criteria (for instance, most students under 25 years old are ineligible). In 2021, 397,785 students were enrolled in tertiary education in Aotearoa (Education Counts, Citation2022), and over the period 2020/2021, 148,905 students borrowed from the loan scheme (Ministry of Education, Citation2022). This level of student endebtedness occurs in a challenging economic environment. High inflation and rising interest rates are being felt by our population as rents remain high, food and petrol prices continue to rise, and the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic continue to be felt (OECD, Citationn.d.). To manage these challenges, it is known that students supplement their income by paid employment, borrowing from family/whānau, using credit cards or overdraft facilities. Overdrafts are readily available when applying for a student account. The backdrop to this is the perceived attitudes to student debt, which add another layer of difficulties when navigating the system.

Combining employment and tertiary study is one way students manage the cost of their studies, though several studies indicate that working while undertaking tertiary education has a detrimental effect on academic outcomes and mental health (Chinyakata et al., Citation2019) and wellbeing (Gair & Baglow, Citation2018a). Earlier studies suggest that debt perception is a predictor of mental distress (Cooke et al., Citation2004) with the author suggesting that further research is needed in this area. Given that the financial climate worldwide has changed substantially since that time, and as student debt becomes more of an inevitability as the cost-of-living increases, this has negatively affected how students perceive and manage their debt as reflected in more recent studies (Richardson et al., Citation2017). The evidence in the literature on the level of student debt and its effects on student mental health is contradictory, however. In a study by Kemp et al. (Citation2006) on student debt and mental health in a large cohort, the researchers did not find evidence that debt accumulation was correlated with mental health problems—though, as suggested above, debt perception may be an important factor in explaining this discrepancy. However, the impact of the demands of tertiary study on student mental health is concerning. The 2017 study ‘Kei Te Pai? Report on Student Mental Health in Aotearoa’ reported on 1762 university students across Aotearoa and found that students reported a moderate level of distress measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Gharibi, Citation2017).

Current study

Researchers from two tertiary institutions offering social work degrees in Aotearoa collaborated in 2019 in an exploratory study of student financial hardship and its impacts on wellbeing amongst a national sample of current social work students and recent graduates. Our aim was to gain a broad view of the impact of social work study on student financial, social, and mental wellbeing. Our engagement with the extant research, as well as own experiences of working with social work students over many years led us to anticipate that students with the greatest levels of anxiety about student debt were most likely to be those who balanced study with caring and other cultural/community responsibilities. These individuals likely managed both their anxiety and their debt by combining study with employment. We expected to find that the pressure to successfully balance their studies with these other responsibilities would have an additional negative impact on their wellbeing. Finally, we anticipated that these negative impacts would be manifest more clearly amongst Māori and Pasifika participants, as being those more likely to have a range of caring and other cultural/community responsibilities, and fewer economic resources (other than employment) to draw upon.

This was designed as a mixed-methods study: we aimed to make an online anonymous survey available to all current social work students and recent graduates, followed by semi-structured follow-up interviews of survey respondents who indicated an interest in participating in them. Our approach can be characterized, using Creswell and Plano Clark’s (Citation2011) typology, as an exploratory sequential design, in which the survey identified key characteristics of the sample and highlighted issues of particular relevance to them, which were then explored qualitatively in the interview phase. Given the amount of data—both quantitative and qualitative—produced in the full study, this article outlines key aspects only of the survey data related to student financial hardship and its relationship to social and mental wellbeing. Further publications address other aspects of interest, including dissemination of the relevant qualitative data (Beddoe et al., Citation2023).

Context

To gain registration as a social worker in Aotearoa, students must graduate with a social work qualification recognized by the Social Workers Registration Board (SWRB), comprising either a four-year full-time equivalent bachelor’s degree or a two-year full-time equivalent master’s qualification. A full-time social work programme requires around 40 hours per week comprising lectures and study plus a total of 120 days of field education (approximately 900 hours in total) across the degree. Students do not receive any financial compensation whilst on practicum, and the hours are mandatory. There are currently no bursaries available for students in qualifying social work programmes in Aotearoa: essentially, students wishing to embark on a social work career must self-fund. A review of literature conducted over 2019–2022 found that social work study requirements produce negative financial and mental health impacts (Cox et al., Citation2022). These requirements are similar to those in Australia, where a recent study by Hodge et al. (Citation2021), found that social work students’ wellbeing was negatively impacted through practicum, with additional stressors placed onto managing their financial security with the commitments of social work placement. While Hodge et al.’s participants perceived some flexibility to balance work and study commitments by being able to skip lectures or catch up on studies outside of work and university time, this was not able to be done with field placement. Hodge et al. (Citation2021) note that these commitments disproportionately affect women, given social work students are predominantly female. The intersection here with a significant proportion of students who are also caring for others further adds to the stressors when undertaking compulsory placement.

Gair and Baglow (Citation2018a), explored the impacts of poverty and psychological stress on social work students in Australia. In total, 2,320 participants engaged in the survey across 29 Australian tertiary institutes, which examined the impact of low income on the daily lives of students and their study success. The study compared social work students’ responses on financial hardship scales with those of an earlier survey of the general tertiary student population and found that 18% of undergraduates in the general student population responded ‘yes’ to regularly going without food or other necessities compared to 32% of social work undergraduate students. Gair and Baglow (Citation2018a) highlighted the critical reflection of some of their respondents. They noted the irony that, while the social work curriculum is grounded in social justice, many social work students find themselves facing harsh realities.

Impacts on mental health, and consequently study outcomes, also emerge as a feature of the research on social work student wellbeing. Given the high rates of burnout in the profession (Stamm, Citation2005), the higher prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in social work (Steen et al., Citation2021; Thomas, Citation2016), and evidence that participation in employment while studying social work increases risk of burnout during study and in future employment (Benner & Curl, Citation2018), this is an area of concern for social work educators. In a study by Vickers et al. (Citation2003) the researchers found a positive linear relationship between the hours worked and dropping out from studies, while another study by Robins et al. (Citation2018) showed that increased rates of student burnout was a predictor of workplace burnout as students transitioned from their academic studies into the workforce.

Students with caring responsibilities have emerged as a particularly vulnerable group. Raven et al. (Citation2021), reported that Māori (Indigenous) social work students in Aotearoa were overrepresented in measures of material hardship while Australian research has reported the ‘grinding effect of poverty on many mature-aged social work students’ (Baglow & Gair, Citation2019, p. 91). In both countries, many mature students are caregivers who have been found to experience numerous pressures as they juggle the unremitting demands of work, study, and home (Baglow & Gair, Citation2019; Hodge et al., Citation2021; Raven et al., Citation2021). An analysis of qualitative data collected via semi-structured interviews in our present study found that social work student caregivers disclosed that study required considerable sacrifice to their personal wellbeing (Hulme-Moir et al., Citation2022).

Benner and Curl (Citation2018) explored the role of burnout amongst social work students due to the stress of balancing paid employment with their studies. They defined burnout based on Schaufeli and Enzmann’s theory as the conflict arising in attempting to meet the responsibilities of different roles, with having too much to do with not enough time (Schaufeli & Enzmann, Citation1988). An Australian study by Gair and Baglow in 2018, comparing a 2012 survey of student social workers and a replication study in 2015, found that day-to-day living costs had increased with many more students reporting regularly going without adequate food, fuel, medications and textbooks for their studies (Gair & Baglow, Citation2018b). Overall, students reported more difficulties balancing paid employment and study, and this had a direct impact on their day-to-day living, their mental health and their academic success.

Calls for meaningful changes to the policies governing social work placements in Australia are becoming more insistent in light of findings that indicate the concessions made by the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) to the accreditation standards during the COVID pandemic, allowing for the reduction of the required practicum hours, were both temporary and insufficient (Morley et al., Citation2023). These calls are to consider options such as financial support for students, or paid placements, or radical reconsideration of how practicum requirements might be made more flexible to accommodate students’ simultaneous engagement in paid employment (Morley et al., Citation2023).

Of course, social work is not the only professional qualification in which unpaid clinical placements feature, and whose students suffer financial strain as a result. Teaching and nursing—both of which are also female-dominated professions—similarly require students to engage in unpaid placements, and research into those professions also raises concerns about the wider impacts on students of the financial burden of this requirement (Raven et al., Citation2021; Predergast et al., Citation2021). However, space does not allow a comparison in this article of the ‘practicum poverty’ experienced by students preparing for these professions.

Methods

As the first phase of the mixed-methods study, an online survey was designed to be undertaken by current students and recent graduates (i.e. within the previous five years) of all qualifying social work programmes in Aotearoa. At the time the survey was administered, there were 17 different providers of social work education in Aotearoa. To reach current students in each institution, we enlisted the support of the peak body, the Council for Social Work Education (CSWEANZ), who forwarded the survey invitation to all the schools of social work, to advertise the survey to their own students. We also advertised via the Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Social Workers (ANZASW), to attract members who were recent graduates. The advertisements invited those eligible to participate in the anonymous survey with details about the topics to be addressed (and the link to the survey), and also indicated the opportunity to participate in interviews.

The Qualtrics survey was available online for the first three months of the academic year, 2019. In total, 353 social work students or recent graduates completed the questionnaire.

Instrument

The survey was designed with reference to similar surveys previously conducted in other countries of social work and nursing students, relating to the impact of financial concerns on their decision to persist with their study. For example, Baglow and Gair (Citation2018) adapted their survey from an earlier Universities Australia study (see also Baglow & Gair, Citation2019; Gair & Baglow, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Their survey covered much the same ground as ours, in terms of forms of financial support accessed by students, the impacts of financial hardship on studies and on other aspects of life, and family responsibilities. Similarly, Grant-Smith and de Zwaan (Citation2019) developed an online survey of Australian nursing students to explore the financial impact of clinical placements, which included specific questions on caring responsibilities, which we adapted. In all, our questionnaire contained 33 closed and open-ended questions that addressed a range of topics, including:

demographic variables (including age, gender, ethnicity).

caring responsibilities, including care for children, caring responsibilities for other family members or friends, and other non-paid caring responsibilities.

details of the social work qualification undertaken (e.g. undergraduate/postgraduate, year completed or expected to complete, part-time or full-time study), but not including the educational institution, to preserve anonymity;

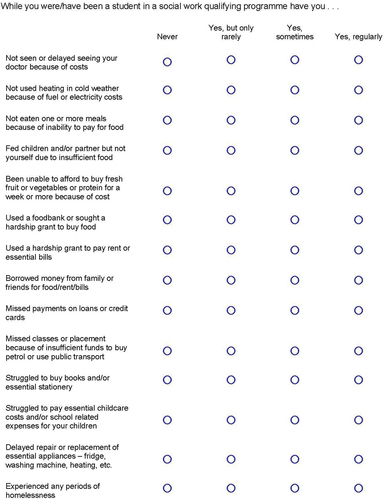

financial matters, including employment circumstances while studying, forms of financial support, details of student loan debt and attitudes toward debt, and details of the impact of financial hardship (detailed in );

aspects of social wellbeing, including questions about the impact of study pressures on relationships with partners, family members, friends, community and hapū/iwi, and on other cultural pursuits;

aspects of mental wellbeing, including whether participants had sought medical advice on their mental health, attended counseling or therapy, taken prescription medications for mental health or sleeping difficulties, and whether they had ever experienced significant mental health challenges but chose not to seek medical advice; and

positive strategies that they may have employed to cope with the impact of studying.

Most of the closed questions related to financial matters, social and mental wellbeing, and positive strategies used Likert-type response sets across multiple items. As the study was exploratory, we chose to develop items whose points of reference would be particularly meaningful for this group of participants (New Zealand social work students and graduates), and which elicited more detailed responses than the earlier Australian questionnaires referenced. For example, the ‘financial impact’ question used a four-point response scale (Never/Yes, but only rarely/Yes, sometimes/Yes, regularly) to elicit responses on 14 items. These items are reproduced in .

The same response options were used in the multi-item questions regarding the impacts on family and social relationships and activities (eleven items), and on mental health (four items).

For the question about positive strategies participants may have employed, a five-point ordinal scale was used, ranging simply from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’ to elicit responses on 12 items, including peer support, family/whānau support, supervision, involvement with marae or hāpori (community) or other cultural activities, religious or spiritual practice, etc.

Included at the end of each substantive section of the questionnaire (financial circumstances, social and mental wellbeing), participants were offered open-ended opportunities to provide further comment or detail. Additionally, the questionnaire ended with an open field for participants to provide any other comment they would like regarding stresses, financial and social challenges they have faced as social work students.

The questionnaire was piloted amongst relatively recent social work graduates who were nonetheless ineligible to participate (i.e. having graduated more than five years previous), and items were reworked in response to feedback (Strydom, Citation2021).

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze individual variables, with ANOVA employed to measure the relationships between financial hardship and mental and social wellbeing, as described below.

The study gained approval from the ethics review committees of both the institutions in which the members of the research team were employed.

Limitations

To address hesitation on the part of institutional gatekeepers, and in line with our ethical undertakings, we did not ask participants to identify the institutions they studied in, thus preventing any analysis of differences across social work education providers. We are unable, therefore, to assess the ‘reach’ of the sample. Additionally, as this was an exploratory study, we opted to design original items to assess participants’ attitudes toward student loan debt, as well as their experiences of financial hardship, social and mental well-being that we tailored to our context. While useful to gain a detailed picture of their contextualized experiences, this limits our ability to compare our results with other studies using existing instruments. Given the stipulation that participants who had already graduated needed to have done so within the previous five years, it was decided to treat all participants as a single cohort, rather than analyze for differences between current students and recent graduates.

Results

Demographics of the participants

Details of the participants are presented in . The high proportion of female respondents was to be expected, given that social work is a highly gendered profession. The participants were all in the process of completing or had recently completed a tertiary qualification in social work. Out of the participants who provided details of their degree studies 82.7% (n = 282) were studying in an undergraduate and 17.3% (n = 59) were studying in a postgraduate social work qualification. In total, 82% (n=288) were (or had been) studying full-time and 18% (n = 63) were (or had been) studying part-time. Nearly two-thirds of the participants (64.3%) were aged under 35, while 6 participants identified as being 55 or older.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

In terms of ethnic identity, it should be noted that respondents were able to choose more than one ethnicity, so their answers were prioritized according to the Ministry of Health guidelines. Proceeding with a prioritized ethnicity variable allowed us to keep the initial size of the sample. These results are presented in .

Table 2. Prioritised ethnicity.

Financial support during study

Participants could report all forms of support they received as a part of their studies. These are detailed in . In total 907 responses were recorded from the participants, meaning multiple income streams were needed for many students to financially support themselves during study. Wages was the most commonly reported source of income, followed closely by student loans. Nearly half the participants received student allowances, and more than a quarter of respondents (28.3%) indicated receiving other formal income support. Several students reported receiving scholarships, while 164 respondents reported receiving financial support from parents, partners, or other family/whānau members. Most respondents (86.4%) reported a student loan debt, which ranged in size from $2,000 to $100,000. The mean student loan debt amongst respondents was $31,777.

Table 3. Financial and living arrangements while studying.

Anxiety towards student loan

Participant responses to the question about student loan debt anxiety are presented in . Of those who responded to this question, only 30 (10.1%) reported they never felt anxious about their student loan debt. Overall, 89.9% (n = 268) had experienced anxiety around their student loan debt. The study found there was a significant difference regarding the size of loans among groups (F (4, 288) = 2.62, p = .035). Post hoc analyses using the LSD post hoc criterion for significance indicated that NZ/European had significantly higher debts than Pacific and Asian participants. Finally, there was a difference regarding the rate of anxiety about their debts among four ethnicities (F (4, 290) = 3.64, p = .006), with Pacific participants being more anxious than all other groups regarding their debts.

Financial hardship scales

shows the distribution of the results for the financial hardship index.

Table 4. Financial hardship responses.

In all, 328 responses were recorded for this question. The researchers then created a ‘financial hardship index’ score for each participant by converting each response to a score of 1–4 respectively for each of the 4 responses and summing them to create the total score. Those scores were then grouped into three financial hardship categories: low (index scores 14–27), moderate (scores 28–41), and severe (scores 42–56). The results showed that 60.7% of participants experienced low financial hardship, 32.6% experienced moderate financial hardship and 6.7% experienced severe financial hardship.

Mental wellbeing

The survey asked participants to disclose if they had ever sought medical advice for their mental health. 337 participants answered this question: the results are presented in . Responses to follow-up questions regarding mental health are presented in .

Table 5. As a social work student, sought medical advice on mental health (n = 337).

Table 6. Utilised mental health interventions as a social work student.

In all, 334 responses were recorded for these three questions. The researchers then created a ‘mental well-being index’ score for each participant by converting each response to a score of 1–4 respectively for each of the 4 responses and summing them to create the total score. Those scores were then grouped into three mental well-being categories: good (index scores 3–5), moderate (scores 6–8), and poor (scores 9–12). The results, presented in , showed that 12.3% of participants experienced poor mental well-being, 18.9% experienced moderate mental well-being and 68.9% experienced good mental well-being.

At the same time, 60% of respondents disclosed that during their studies they had experienced significant anxiety, stress, or depression, but chose not to seek medical advice for their mental health (). In an open-response question as to why they chose not to seek medical advice for their mental health, 191 respondents offered a variety of explanations, with some participants citing more than one reason. These are presented in . It is noteworthy that nearly half the respondents (47.1%) indicated a lack of time or finances, while more than a quarter (28.3%) indicated concerns around stigma or the potential impact on their studies or future employment to explain why they chose not to seek mental health advice. Analysis of text responses to an open question about this decision has been reported elsewhere (Beddoe et al., Citation2023).

Table 7. Experienced significant anxiety, stress, or depression, but chose not to seek medical advice for mental health (n = 331).

Table 8. Explanations for not seeking medical advice for mental health (n = 191).

Relationship between financial hardship and mental wellbeing

Analysis was conducted on the impact of financial hardship on mental wellbeing. A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to explore the effect of financial hardship on total score of mental wellbeing. There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA [Welch (2, 51.747) = 12.056, p = 0.001]. A Games-Howell post hoc test revealed that the mental wellbeing was statistically significantly lower for those reporting severe financial hardship (m = 7.85, SD = 3.13) and moderate (m = 8.48, SD = 2.95) compared to those reporting low financial hardship (m = 9.94, SD = 2.41). But there was no significant difference between those with moderate and severe financial hardship regarding their mental well-being.

The researchers examined the association between mental wellbeing and student loan with an independent t-test. The results showed lower mental well-being for those who had a student loan (M = 9.20, SD = 2.79) compared with those who did not have a student loan (M = 10.26, SD = 2.13, t (332) = −2.437, p = .015). A Pearson Correlation was conducted to understand the relationship between level of student loan and mental wellbeing. There was a significant negative relationship (r = −0.181, p = .002).

Social wellbeing

shows the distribution of the results for the social wellbeing questions.

Table 9. Distribution of social well-being index.

In total, 341 responses were recorded. The smallest proportion of respondents felt that they never had to sacrifice doing important activities with their partner or friends (just over half saying they regularly did so). On the other hand, those activities and commitments that respondents felt the least pressure on were their engagement with their communities (marae/hapori/hapu/iwi), time to do activities with children, participation in other cultural activities or exercise and play. When developing index scores with the same method as used for financial hardship, around one third of respondents (30.2%) experienced high social wellbeing. Moderate social wellbeing was reported by 46.6% of participants, and poor social wellbeing was reported by 23.3% of respondents.

Relationship between financial hardship and social wellbeing

Analysis was conducted on the impact of financial hardship on social wellbeing. A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to explore the effect of financial hardship on total score of social wellbeing. There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA [F (2, 292) = 45.375, p = 0.001]. A Scheffe post hoc test revealed that social wellbeing was statistically significantly lower for those reporting severe financial hardship (m = 13.80, SD = 4.96) compared to those reported moderate (m = 17.55, SD = 4.52) and low financial hardship (m = 22.13, SD = 5.05).

The researchers examined the association between social wellbeing and student loan with an independent t-test. The results showed no significant difference between social well-being of those who had a student loan (M = 19.91, SD = 5.57) and those who did not have a student loan (M = 21.39, SD = 5.87, t(303) = −1.602, p = .110). A Pearson Correlation was conducted to understand the relationship between level of student loan and social wellbeing. There was no significant relationship (r = −0.056, p = .366).

Caring responsibilities

Respondents were asked if they had caring responsibilities for children. Out of 333 who answered this question, 136 (40.8%) respondents said they had caring responsibilities. Of this group, 25.8% had a child or children, 15.0% were caring for others, and 16.4% of respondents were caring for children and others. Four respondents did not provide data.

Regarding the association between caring responsibilities and financial hardship the result of ANOVA (F (3, 333) = 9.38, p = .001) showed a significant difference. Post hoc analyses using the Scheffé post hoc criterion for significance indicated that those with more than one type of caring responsibility had been impacted financially more than the other three groups.

Discussion

This article has reported the findings on the impact of financial circumstances on the mental and social wellbeing of social work students demonstrating the hidden burdens carried by social work students and the impacts of the current socio-economic climate. Our results echo Gair and Baglow’s (Citation2018a) findings and highlight a growing understanding of how financial hardship impacts student well-being and how this particularly affects social work students before they have commenced their career.

In our study, using financial hardship scales, two-thirds (67.7%) of social work students experienced moderate or severe financial hardship. Moderate financial hardship was experienced by just under half of the students, and severe/extreme hardship experienced by 18% of students, with a particular impact on caregivers. This is especially salient, as social work students will go on to a career that is fraught with pressures and is historically a low-paid profession. Given the vital role social workers play in our communities, implications of the findings should prompt consideration of better financial support for their studies, and a broader question of how social workers are valued in our society. This study, the first of its kind in Aotearoa, also investigates the cultural disparities of the social worker student population, giving weight to the argument for better equity across ethnicity for social work students. Our study supports the findings Gair and Baglow (Citation2018b) reported in their aptly titled article ‘We Barely Survived’ where they state that there is mounting evidence that the ongoing impacts of poverty and psychological stress impact on the daily lives and academic outcomes of social work students.

Student loans

The results highlighted the high prevalence of debt amongst social work students. The students in this study had loans and greater debt than their Australian counterparts (Unrau et al., Citation2019). In a study on student debt and its effect on lifetime income, the researchers suggest that the student debt amount equates to approximately four times the wealth lost over a lifetime, and this impact is more severe for low socioeconomic groups (Hiltonsmith, Citation2013).

After a long period of neoliberal reforms in Aotearoa during the 1980s, 1992 saw the eventual abolition of grants for tertiary education and tuition fees were introduced. With successive governments trying to curb public spending and invest in the new ‘global knowledge economy’, university reform has seen a steep rise in student numbers and a dramatic decline in funding (Shore, Citation2010). Despite the Labour government introducing a fees-free policy for first year students in 2018, the neoliberal discourse has continued to thrust the responsibility for funding study in tertiary education onto students and their families (Roper, Citation2018). Student loan debt has been steadily rising in Aotearoa. Since the introduction of tertiary fees in 1992, students have borrowed a total of $27.4b NZD in loans. In 2019, the average student loan balance for undergraduates was $35,510, with the forecast median repayment time of 8.6 years (Ministry of Education, Citation2022).

Amongst our survey participants there was no significant difference across ethnic groups in having a student loan, but there was significant difference in the size of loans, with NZ Europeans reporting higher debts than Pasifika, Māori and MELAA students. However, the level of anxiety around student loan debt was different across ethnicities, with Pasifika students reporting more anxiety around their student loan debt compared to the other groups.

In a 2016 in an Aotearoa study on equity of university graduates, the researchers found that 2 years after graduation, Māori and Pacific graduates had significantly higher student debt and financial pressures over time compared with NZ European graduates. It was reported that Māori and Pacific families are significantly more likely to help other family members such as offering their time, skills or resources, and are significantly more likely to engage in volunteering than NZ European graduates (Theodore et al., Citation2018). Another study by Benseman et al. (Citation2006) on retaining non-traditional students, found the importance of family to Pasifika students, but also stated that Pasifika families have lower household incomes and the pressure on finances was a major barrier to their tertiary education. Outside their academic life, students had considerable expectations placed upon them to attend family functions and church, as well as study. The participants in the study reported that their family obligations were seen as more important than study which placed considerable pressure on students (Benseman et al., Citation2006).

A study by Theodore et al. (Citation2018), examined data from Pasifika participants who were a part of the Graduate Longitudinal Study New Zealand. Participants were asked as to what helped or hindered their study, and their results are applicable to our findings. In terms of hindering the completion of their studies, the most mentioned factor was family commitments. In often inflexible university systems, family commitments overrode the understanding of study requirements, and the pressure to earn money to support the family were other factors impacting the tertiary experience. A range of both physical and mental health issues also emerged in the findings from this study, and this was impacted by the need to work due to financial pressures and the difficulty in finding a balance between paid employment, family commitments and study.

Our literature review of social work student hardship noted that despite our multi-cultural landscape, there is a gap in the literature examining the relationship of cultural, religious and community commitments for minorities within student life (Cox et al., Citation2022). Given the disparities in health and socioeconomic outcomes particularly for Māori, Pasifika and migrant groups in the country, more attention should be paid to how culture and ethnicity intersect with outcomes for tertiary students. Stratification between students with different socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds has been cited in the literature, with students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds adversely affected (Antonucci, Citation2016; Despard et al., Citation2016). This strongly supports Curtis et al. (Citation2012) who sought to identify the ‘best practice’ drivers to address the underrepresentation of indigenous health professionals and argued that institutions need to demonstrate tangible commitments to equity.

Impacts on mental wellbeing

Engaging in paid employment whilst undertaking tertiary education has become a matter of course, rather than a matter of choice in recent years with impacts on well-being (Beban & Trueman, Citation2018; Fraser et al., Citation2016; Gair & Baglow, Citation2018a; Grozev & Easterbrook, Citation2022). Our results show that mental wellbeing was significantly lower for those reporting severe or extreme financial hardship suggesting that social work students are at greater risk of the effects of hardship on mental wellbeing than the general student population. In this study, there was no significant relationship between working and mental wellbeing, suggesting that working does not alleviate the negative effects of financial stress on wellbeing.

The results that indicated that nearly 61% of respondents chose not to seek medical advice for their mental health should be concerning as these students prepare to enter a profession that expresses a commitment to self-care and anti-discriminatory practices. This phenomenon has been explored in greater depth in Beddoe et al. (Citation2023), incorporating additional qualitative data analysis from interviews conducted in the wider study.

Impacts on social wellbeing

The results showed a significant difference in social well-being between those carrying student loan debt, and those not. Those who had a student loan reported lower social well-being compared with those who did not have a student loan. There was a negative but weak relationship between the amount of student loan debt and social well-being with the higher the score of indebtedness, the lower social well-being was reported. In this study, younger students reported higher levels of social wellbeing (those aged under 25) compared all other age groups, possibly attributed to older students more likely to have caring responsibilities with family/whānau. As noted earlier, Baglow and Gair (Citation2019) found that many mature age students experience poverty during their studies compared to younger students. Our study showed that the more caring responsibilities one had, the more impact on their financial wellbeing. We concur with Baglow and Gair’s recommendation that social work educators and tertiary administrators consider study equity for mature-aged students, particularly those with caring responsibilities.

The results of this study show that the greatest predictor of social wellbeing amongst the participants was student debt. The greater impact was seen in a student’s engagement in socialization, while sport and cultural activities variables did not significantly differ by debt status. While student debt has become a normal part of tertiary education (Bristow et al., Citation2020) it must be recognized that indebtedness creates additional pressures that affect student wellbeing.

Part of the research was used to determine the relationship between financial hardship and social wellbeing. The researchers found a strong positive relationship between financial hardship and social well-being for a quarter of the respondents, indicating that not everyone who experiences financial hardship experiences difficulties in social well-being. This may be explained by some students becoming more tolerant of student debt (Zhang & Kemp, Citation2009). However, those who indicated negative impacts to their social well-being were more likely to be experiencing financial hardship. These results corroborated the results with a previous Australian study where their results showed that financial hardship affected social wellbeing amongst tertiary students (Halliday-Wynes & Nguyen, Citation2014, pg. 22).

When looking at caring responsibilities, social work students caring for children experienced significant differences in financial hardship and social wellbeing. Our results suggest that parent students were more vulnerable to financial struggles and tended to have lower social wellbeing as reported in our qualitative analysis (Hulme-Moir et al., Citation2022). The survey queried participants for different caring responsibilities; children, others, children and others. Additional analysis for those with more than one type of caring responsibility (e.g. children and another family member) showed they been impacted more than the other groups. Those caring for others showed that their ability to socialize and engage in sporting activities were the areas of social wellbeing that were most affected. Osbourne et al. (Citation2004) suggest that the older the student is, the more likely they are to have additional financial commitments and dependents. There have been several studies suggesting the added difficulties for students with parental responsibilities including the balancing parenting and study leading to role conflict (Webber & Dismore, Citation2021) and feelings of guilt (Agllias et al., Citation2016). Tones et al. (Citation2009) noted that while mature students were potentially able to succeed at university in the same ways as their younger counterparts, financial and family commitments became a major barrier to study success. In this study, the under 25 age group experienced better outcomes with social wellbeing, especially in the category of socializing. This group also experienced more engagement with cultural activities more than the other age groups.

Concluding statement

Social work in Aotearoa needs a diverse workforce, and further research may illuminate the implications of these findings as social workers progress in their career. While this study focused on those who have decided to persist despite the financial hardship, and its impact on other aspects of their lives, we do not know the numbers and stories of those who found the financial burden too great and were lost to the profession as a result. Given the perennial workforce shortage in Aotearoa New Zealand social work, such losses represent a social cost shared more broadly.

It is useful to consider these findings with reference to a recent study published by Pentaraki (Citation2017) showing the emerging shared reality of social workers and their service users. While the concept of shared reality is more commonly applied to situations where social workers and service users are exposed to the same adverse effects of war, terrorist attack or natural disaster, it can be expanded to encompass the outcomes of austerity measures after the global economic crisis. While arguably, Aotearoa has not been subject to severe economic austerity measures compared to some other countries, living costs are rising, and graduates are entering a profession that is comparatively lower paid. How these financial hardships will carry over to their professional lives is an area for further discussion.

Given that all students in the study experienced financial hardship, a system wide approach to addressing this is called for. Targeted interventions including increased financial support, especially while on placement, as well as better access to mental health support within the university environment to help retain and support social work students is needed (Morley et al., Citation2017). Social work can be a rewarding but challenging career, so when students are learning and understanding the intrinsic importance of advocating for social justice, it is time now for government, tertiary institutions, and the wider sector to reflect those values with a united approach to better support social work students in Aotearoa.

Glossary of te reo Māori terms

| Whānau | = | Family, extended family and a collective through a common ancestor |

| Marae | = | The courtyard and the buildings surrounding that form the meeting house for a hapu or iwi. |

| Hapori | = | Community |

| Hapu | = | Sub-tribe |

| Iwi | = | Tribe |

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all those social work students who participated in the survey and shared their experiences with us. We wish to acknowledge the students whose analysis of some of the data contributed to this article: Olivia Nicolo, Catherine Roguski, and Tanniti Wangsapan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agllias, K., Howard, A., Cliff, K., Dodds, J., & Field, A. (2016). Students’ experiences of university and an Australian social work program: Coming, going, staying. Australian Social Work, 69(4), 468–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2015.1090464

- Antonucci, L. (2016). Student lives in crisis: Deepening inequality in times of austerity. Policy Press.

- Baglow, L., & Gair, S. (2018). Australian social work students: Balancing tertiary studies, paid work and poverty. Journal of Social Work, 19(2), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318760776

- Baglow, L., & Gair, S. (2019). Mature-aged social work students: Challenges, study realities, and experiences of poverty. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1534130

- Beban, A., & Trueman, N. (2018). Student workers: The unequal load of paid and unpaid work in the neoliberal university. New Zealand Sociology, 33(2), 99–131.

- Beddoe, L., Baker, M., Cox, K., & Ballantyne, N. (2023). Mental health struggles of social work students: Distress, stigma, and perseverance. Qualitative Social Work, 14733250231212413. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250231212413

- Benner, K., & Curl, A. (2018). Exhausted, stressed, and disengaged: Does employment create burnout for social work students? Journal of Social Work Education, 54(2), 300–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1341858

- Benseman, J., Coxon, E., Anderson, H., & Anae, M. (2006). Retaining non‐traditional students: Lessons learnt from Pasifika students in New Zealand. Higher Education Research & Development, 25(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360600610388

- Bristow, J., Cant, S., & Chatterjee, A. (2020). Generational expectations and experiences of higher education. In J. Bristow, S. Cant, & A. Chatterjee (Eds.), Generational encounters with higher education (pp. 45–70). Bristol University Press.

- Chinyakata, R., Raselekoane, N., & Regaugetswe Consolia Mphahlele, R. (2019). Factors contributing to postgraduate students working and studying simultaneously and its effects on their academic performance. African Renaissance, 16(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.31920/2516-5305/2019/V16n1a4

- Cooke, R., Barkham, M., Audin, K., Bradley, M., & Davy, J. (2004). Student debt and its relation to student mental health. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 28(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877032000161814

- Cox, K., Beddoe, L., & Ide, Y. (2022). Social work student hardship: A review of the literature Aotearoa New Zealand social work. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 34(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol34iss1id848

- Cresswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Curtis, E., Wikaire, E., Stokes, K., & Reid, P. (2012). Addressing indigenous health workforce inequities: A literature review exploring ‘best’ practice for recruitment into tertiary health programmes. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-13

- Despard, M. R., Perantie, D., Taylor, S., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Friedline, T., & Raghavan, R. (2016). Student debt and hardship: Evidence from a large sample of low-and moderate-income households. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.001

- Education Counts. (2022). Students enrolled at New Zealand’s tertiary institutions. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/tertiary-participation

- Fraser, H., Michell, D., Beddoe, L., & Jarldorn, M. (2016). Working-class women study social science degrees: Remembering enablers and detractors. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(4), 684–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1137885

- Gair, S., & Baglow, L. (2018a). Social justice in a tertiary education context: Do we practice what we preach? Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 13(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197918793059

- Gair, S., & Baglow, L. (2018b). “We barely survived”: Social work students’ mental health vulnerabilities and implications for educators, universities and the workforce. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 30(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol30iss1id470

- Gharibi, K. (2017). Kei te pai? Report on student mental health in Aotearoa. New Zealand union of students’ associations. https://www.students.org.nz/s/Kei-Te-Pai-Report.pdf

- Grant-Smith, D., & de Zwaan, L. (2019). Don’t spend, eat less, save more: Responses to the financial stress experienced by nursing students during unpaid clinical placements. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.12.005

- Grozev, V. H., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2022). Accessing the phenomenon of incompatibility in working students’ experience of university life. Tertiary Education and Management, 28(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-022-09096-6

- Halliday-Wynes, S., & Nguyen, N. (2014). Does financial stress impact on young people in tertiary study? NCVER.

- Hiltonsmith, R. (2013). At what cost? How student debt reduces lifetime wealth (report). Demos.

- Hodge, L., Oke, N., McIntyre, H., & Turner, S. (2021). Lengthy unpaid placements in social work: Exploring the impacts on student wellbeing. Social Work Education, 40(6), 787–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1736542

- Hulme-Moir, K., Beddoe, L., Davys, A., & Bartley, A. (2022). Social work education in Aotearoa New Zealand: A difficult journey for student caregivers. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 34(4), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol34iss4id985

- Kemp, S., Horwood, J., & Fergusson, D. (2006). Student loan debt in a New Zealand cohort study. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 41(2), 273.

- Ministry of Education. (2022). Student loan scheme annual report 2020/21. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/213752/GAV-0741-Student-Loan-Scheme-Annual-Report-2021_web.pdf

- Morley, C., Hodge, L., Clarke, J., McIntyre, H., Mays, J., Briese, J., & Kostecki, T. (2023). ‘This unpaid placement makes you poor’: Australian social work students’ experiences of the financial burden of field education. Social Work Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2161507

- Morley, C., Macfarlane, S., & Ablett, P. (2017). The neoliberal colonisation of social work education: A critical analysis and practices for resistance. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(2), 25–40.

- OECD. (n.d.). New Zealand economic snapshot 2022. https://www.oecd.org/economy/new-zealand-economic-snapshot/

- Osborne, M., Marks, A., & Turner, E. (2004). Becoming a mature student: How adult appplicants weigh the advantages and disadvantages of higher education. Higher Education, 48, 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000035541.40952.ab

- Pentaraki, M. (2017). ‘I am in a constant state of insecurity trying to make ends meet, like our service users’: Shared austerity reality between social workers and service users—towards a preliminary conceptualisation. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(4), 1245–1261. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw099

- Prendergast, M., Ní Dhuinn, M., & Loxley, A. (2021). “I worry about money every day”: The financial stress of second-level initial teacher education in Ireland. Issues in Educational Research, 31(2), 586–605.

- Raven, A., Jakeman, A., Dang, A., Newman, T., Sapwell, C., Vaughan, S., Peters, T., & Nathan, P. (2021). Report on material hardship and impacts on ākonga wellbeing and educational outcomes: Bachelor of applied social work (BASW) and Bachelor of nursing studies, Tai Tokerau Wānanga, Northtec, 2021. Whanake: The Pacific Journal of Community Development, 7(1), 6–42. https://doi.org/10.34074/whan.007101

- Richardson, T., Elliott, P., Roberts, R., & Jansen, M. (2017). A longitudinal study of financial difficulties and mental health in a national sample of British undergraduate students. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0

- Robins, T. G., Roberts, R. M., & Sarris, A. (2018). The role of student burnout in predicting future burnout: Exploring the transition from university to the workplace. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344827

- Roper, B. (2018). Neoliberalism’s war on New Zealand’s universities. New Zealand Sociology, 33(2), 9–39.

- Schaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. CRC Press.

- Shore, C. (2010). Beyond the multiversity: Neoliberalism and the rise of the schizophrenic university. Social Anthropology: The Journal of the European Association of Social Anthropologists = Anthropologie Sociale, 18(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2009.00094.x

- Stamm, B. (2005). Professional quality of life scale: Compassion satisfaction, burnout and fatigue/secondary trauma subscales–revision IV. https://www.isu/edu-bihstamm.

- Steen, J. T., Senreich, E., & Straussner, S. L. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among licensed social workers. Families in Society, 102(2), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389420929618

- Strydom, H. (2021). Sampling techniques and pilot studies in quantitative research. In C. B. Fouché, H. Strydom, & W. J. H. Roestenburg (Eds.), Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human services professions (5th ed., pp. 227–247). Van Schaik.

- Theodore, R., Taumoepeau, M., Kokaua, J., Tustin, K., Gollop, M., Taylor, N., Hunter, J., Kiro, C., & Poulton, R. (2018). Equity in New Zealand university graduate outcomes: Māori and pacific graduates. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344198

- Thomas, J. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences among MSW students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36(3), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2016.1182609

- Tones, M., Fraser, J., Elder, R., & White, K. (2009). Supporting mature-aged students from a low socioeconomic background. Higher Education, 58(4), 505–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9208-y

- Unrau, Y. A., Sherwood, D. A., & Postema, C. L. (2019). Financial and educational hardships experienced by BSW and MSW students during their programs of study. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656687

- Vickers, M., Lamb, S., & Hinkley, J. (2003). Student workers in high school and beyond: The effects of part-time employment on participation in education, training and work. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED475343

- Webber, L., & Dismore, H. (2021). Mothers and higher education: Balancing time, study and space. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(6), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1820458

- Zhang, J., & Kemp, S. (2009). The relationships between student debt and motivation, happiness, and academic achievement. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 24–29.