ABSTRACT

This teaching note describes how the author (a practice teacher and university lecturer) retrospectively considered and applied the work of Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger; with a specific focus on situated learning, communities of practice and pre-qualifying social work education in Northern Ireland. Through this retrospective lens, this conceptual paper presents a new, inclusive model for practice teachers (practice educators) and social work students to use in professional supervision. The Social Work Placement Professional Competence (PPC) Model is presented as a supervisory tool to guide and frame professional discussions and critical analysis of student’s practice. The model can be used to critically reflect on the development of the students’ incremental learning, knowledge base, evidence of decision-making, assessment of need and ability to effectively manage risk.

Introduction

In this teaching note, the author retrospectively considered and applied the work of Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and Wenger (Citation1998) with a specific focus on situated learning and communities of practice as a theoretical frame. Drawing on this analysis to consider how these concepts can be applied to pre-qualifying social work students on placement in Northern Ireland. Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) seminal book reframes the concept of learning, proposing that learning is a situated activity which is process driven and occurs through participation in communities of practice. In his book Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity, Wenger (Citation1998) places an emphasis on the lived experience of the learner and locates communities of practice at the center of his social learning model.

Social work education and political conflict in Northern Ireland

Coulter and Duffy (Citation2023, p. 423) reflecting on living through the Troubles discuss the ‘decades of inequality, oppression and discrimination in regard to housing, employment, education and electoral practices’ impacting the Catholic/Nationalist minority. This prompted the rise of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland with marches and protests campaigning for equality. This may resonate with international colleagues where political conflict has been a feature of their contested history. Darby (Citation1995), in his essay on the conflict in Northern Ireland, identifies similarities between what was happening in the United States at this time (1960s). The Troubles lasted over three decades from 1969 until the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

As MacDermott (Citation2023, p. 2) notes ‘Several political controversies led to the collapse of the power-sharing arrangements, with two significant periods of direct rule from Westminster, 2002–2007 and 2017–2020’. In February 2022, the Northern Ireland Assembly was collapsed by the Democratic Unionist Party over concerns post Brexit and the implications of a border in the Irish Sea. This had a paralyzing effect on people and communities in Northern Ireland, at a time when leadership and decisions were required to respond to ongoing social issues including health, education, housing, legacy issues, e.g. Troubles Permanent Disablement Payment Scheme. At the time of writing, 2 years to the day after its collapse on 3 February 2024, Northern Ireland witnessed the reformation of the Northern Ireland Assembly, a moment of tentative optimism for the citizens of Northern Ireland that change, and decisions will be prioritized. An historic occasion for Northern Ireland with the first Republican and Nationalist First Minister finally taking up her role.

Campbell et al. (Citation2019) postulate that for some social work practitioners, experience of working in political conflict lends itself to practice approaches which are more politically aware and aligned to activism. In contrast, Campbell et al. (Citation2013) discuss the impact of neutrality as a practice approach and the tension between internal identities and the professional engagement in human rights and social justice issues. One of the core challenges for practice teachers and social work students in Northern Ireland is the added complexity of trying to navigate our contested histories and understand the impact of sustained political conflict on citizens and communities. The legacy of three decades of conflict, intergenerational trauma, contested histories and the start-stop politics contribute to the ways in which political conflict impacts personal and professional identities in Northern Ireland (Campbell et al., Citation2019; Duffy et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; MacDermott, Citation2023).

Practice teachers and the students they supervise must be able to have honest conversations about personal values and discuss complex intergenerational histories to make sense of practicing in a post-conflict era in Northern Ireland. The Framework Specification for the Degree (Northern Ireland Social Care Council [NISCC], Citation2015) includes a mandatory requirement that the social work curriculum includes learning and teaching on Northern Ireland’s contested history and the impact of past violence on people and communities. A research project with school children in Northern Ireland found that exposure to the Troubles was associated with self-harming behaviors demonstrating the transgenerational effect of the conflict (O’Connor et al., Citation2014). O’Neill and O’Connor (Citation2020) report that almost one in four citizens in Northern Ireland have experienced a traumatic event because of the Troubles.

Social work education in Northern Ireland is regulated by the Northern Ireland Social Care Council, NISCC. Since the introduction of the BSc (Hons) degree in 2004, pre-qualifying social work education is periodically reviewed in five-year cycles (Citation2009, Citation2014, Citation2019a) planning is underway for the next review scheduled for 2024. Practice teachers in Northern Ireland must be registered social workers and must have completed the Northern Ireland Practice Teacher Training Programme or be undertaking the programme with supervision from an assessor. This is taught at master’s level by Ulster University, on successful completion practice teachers obtain 90 academic credits and the Specialist Award in Social Work (NISCC, Professional in Practice Award).

The Department of Health (DoH) commission funding on an annual basis to support social work placement provision across Northern Ireland. This consists of approximately 530 placements per year across level two (85 days) and level three (100 days) placements. These placements are allocated to each of the key placement providers, including all five Health and Social Care Trusts, the voluntary sector, the Education Authority and the justice sectors (Probation Board for Northern Ireland and Youth Justice Agency). At the time of writing, the voluntary sector is providing approximately 20% of undergraduate social work placements in Northern Ireland (NISCC, Citation2021).

A Department of Health (DoH, Citation2020) paper which sets out future planning for statutory recruitment of social work graduates from 2021 is reflective of the continuing trend toward statutory sector dominance in social work education and post-qualifying employment.

final year social work students should be alerted by Universities and Colleges to early recruitment campaigns and encouraged to apply for posts well in advance of their qualification date; and HSC Trusts will be required to further reduce their use of social workers employed by a recruitment agency (DoH, Citation2020, p. 3).

Thus, the current emphasis from the Department of Health is on social work graduates taking up employment in Health and Social Care Trusts. Understandably, the use of recruitment agencies and locums is a drain on finite resources; however, this type of messaging leaves voluntary sector employers in a precarious position in terms of attracting newly qualified social workers into the sector. At the time of writing 595 social workers or 9% of the workforce are employed in the voluntary sector (DoH, Citation2021).

Ferguson (Citation2008), laments the continuing emphasis on metrics, performance management and service provision tendering processes that prevail in the social work provision. The ongoing marketization of social work has resulted in a significant shift toward increased bureaucracy and a technocratic delivery model.

Situated learning and communities of practice

Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) characterize situated learning as social and cultural processes which acknowledge the significance of relationships and interactions between ‘newcomers’ and ‘oldtimers’. Lave and Wenger place emphasis on learning as a process of participation and engagement in communities of practice, suggesting that ‘to be able to participate in a legitimately peripheral way entails newcomers having broad access to arenas of mature practice’ (Citation1991, p. 110). They argue that initially participation is legitimately peripheral and develops incrementally through increased engagement and complexity in ‘the learning of knowledgeable skills’ (Citation1991, p. 29). Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 29) locate ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ as the core characteristic of situated learning. Social work students are at the beginning stage of their learning journey to becoming qualified social workers. These processes involve observing the conduct and practice of others including lecturers, peers, practice teachers, onsite supervisors and learning about the cultures and practices within the placement setting. As social work students negotiate their professional identity the complexities and expectations of learning increases. Students are required to demonstrate competence by applying skills in practice settings, engaging in knowledge building and knowedge exchange, all of which influences their values and actions. These students will participate in various communities of practice to evidence their professional competence through engagement in different activities and the transitioning of their identities from ‘newcomers’ (p. 29) to becoming members of a community of practice. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 35) assert that their definition of legitimate peripheral participation must be viewed as a whole, with each aspect interlinked and “whose combinations create a landscape … of community membership’’.

Some of the concepts and ideas presented in Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and Wenger (Citation1998) are evident in the work of other social work academics. Examples of this include Edmonds-Cady and Sosulski (Citation2012) who apply aspects of situated learning and some of Wenger’s (Citation1998) ideas on community of practice to develop a macro-social work model with students. Their work reflects on the transformative learning between students, lecturers and community members. Gray et al. (Citation2008) consider groupwork in social work practice and that a community of practice must include trust and relationships where knowledge is distributed, creating an environment in which learning and practice are interlinked. In Gray et al. (Citation2010) paper they put forth an argument on ways to build a community of practice between new managerialism in social work and authentic practices with people accessing social services, suggesting that ‘personalisation could be construed as welcoming people who use services into the community of practice’ (Citation2010, p. 29). Writing from a Norwegian perspective, Voll et al. (Citation2021) reflect on Wenger’s (Citation1998) communities of practice in the transfer of knowledge from ‘knowing that’ to ‘knowing how’. Voll et al. (Citation2021) are writing specifically about the transfer from social work student to employee and the transitions occurring within this sphere of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991).

The influence of Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) concepts can also be found in other subject disciplines. O’Brien and Battista (Citation2019) in their scoping review of situating learning theory in health professions education identified ‘learning processes, intentional efforts to facilitate and support learning and identity’ (Citation2019, p. 493) as the core topics addressed within the literature they reviewed. They conclude that viewing professional education as social learning creates the potential to examine experiences of learning across a range of contexts including, lectures, placement learning and simulated learning.

Social work education requires students to participate as learners, locating the learner as inherently involved in learning, thinking, constructing knowledge and trying to make sense of the environment they occupy. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 93) argue that it is the community of practice which creates the opportunities for learning. In his subsequent work, Wenger (Citation1998, p. 73) defines three domains of a community of practice, ‘mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire’. Wenger (Citation1998) defines mutual engagement as doing things and learning together ‘what we do and what we know and connecting to the contributions and knowledge of others’ (Citation1998, p. 76). Joint enterprise refers to mutual accountability of a community of practice in understanding ‘what matters and what does not, what is important and why it is important’ (Citation1998, p. 81). A shared repertoire is the ‘resources for negotiating meaning’ (Citation1998, p. 83), in social work education this includes, activities, tasks, words, stories, models to support learning, professional language, key roles and social work standards.

Reflexivity

Reflecting on the functional relevance of knowledge, Fook et al. (Citation2000), suggest that it is directly linked to several factors, including the ability and willingness to apply knowledge, the context of the work and connections to professional concerns and curiosities. The practice of reflection is embedded in social work education and practice, as evidenced in its dominance within the social work literature (Gibbs, Citation1988; Schön, Citation1983; Tedam, Citation2012; Thompson & Thompson, Citation2008). Critical reflection moves beyond this and seeks to find strategies that question values, thoughts and prejudices in a way that helps to unpack and understand the roles social workers occupy and how relationships are explored, situated and understood in relation to the self and others. Fook (Citation2015) asserts that critical reflection focuses on power and assumptions and that challenging these can lead to transformative changes in how we view situations in practice and beyond.

Applying a retrospective theoretical lens as a foundation for new learning

This section introduces some of the work of Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and Wenger (Citation1998) using the three domains of a community of practice (mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire) as a retrospective theoretical frame. Applying Wenger’s (Citation1998) ideas on communities of practice as a retrospective lens to MacDermott & McCall (Citation2017) emphasized the significance of mutual engagement, in that, the relationship between the student and service user is complex. It is important to acknowledge that learning to be a social worker will inevitably involve competing tensions and conflicts. Wenger (Citation1998, p. 77) posits that disagreements and challenges are forms of participation and reflect ‘the full complexity of doing things together’. Learning to become a professional social worker is not an activity completed in isolation, students must be open to engaging with and receiving feedback from a range of different sources including service users, practice teacher(s), peers, teams and colleagues on placement and through ongoing tutorial support from university tutors.

Cournoyer (Citation2011) advocates the importance of honest and authentic communication, which is integral in learning to become a professional social worker. Huntley (Citation2002), writing in 2002, suggests there is limited awareness on the part of the social worker when the social worker—service user relationship ends. Roberts (Citation2011) posits that little is known about the practice realities of ending relationships in social work. Using professional supervision to reflect on the experiences and perspectives of service users and carers is critical in helping students to negotiate and interpret what endings mean including the impact of endings in helping relationships. This forms part of the shared repertoire (Wenger, Citation1998) of resources that help to understand and to practise endings in social work education. Wenger postulates that ‘the shared repertoire includes the discourse by which members create meaningful statements about the world’ (Citation1998, p. 83). Wylie and MacDermott (Citation2017) outline six key reflection points specific to endings in social work education and training which must be considered. These are preparation, role-play, a focus on feelings, minimizing dependency, working through unfinished business and the importance of a ritualized ending to celebrate and acknowledge the completed work.

Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 52) posit that ‘participation in social practice’ places an emphasis on the learner as ‘a member of a socio-cultural community’. Author’s own (2019) reflects on the question ‘’what does a professional social worker look like even when no one is watching?’’ (p. 2). This provides an insight into the perceptions of the profession from two distinct vantage points: social work students (pre-placement n = 37) as ‘newcomers’ (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, p. 29) and experienced practitioners training to be practice teachers (n = 25), defined as ‘’oldtimers’’ (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, p. 30). Interestingly, both sets of students ‘identified the same top three core parameters of perceived importance in professionalism, that is, reliability, accountability and ethics’ (MacDermott, Citation2019, p. 14).

Social work education in Northern Ireland as a constellation of communities of practice

This section will briefly outline the constellation of communities of practice which comprise social work education in Northern Ireland, beginning with an overview of legitimate peripheral participation and the ways in which this evolves into full participation. From this author’s standpoint social work education in Northern Ireland is presented as a constellation of communities of practice that is based on the rationale that it depends on membership (governed by the regulator regarding designating fitness to practice and registration status) and has clearly defined characteristics, relationships and required levels of practice. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 98) define a community of practice as ‘a set of relations among persons, activity and world, over time and in relation with other tangential and overlapping communities of practice’. Wenger as a contributor in Farnsworth et al. (Citation2016) puts forth his view that

over time, communities of practice develop regimes of competence, which reflect their social histories of learning and to which learners are now accountable. (Citation2016, p. 145)

Social work education in Northern Ireland has three distinct learning phases that encompass the continuum of lifelong learning associated with the profession, that is, pre-qualifying, assessed year in employment and postgraduate (professional in practice). Wenger (Citation1998) subscribes to the view that ‘it is by its very practice … that a community establishes what it is to be a competent participant, an outsider, or somewhere in between’ (p. 137). The commitment to sustained learning from pre-qualifying to post qualifying aligns with Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) emphasis on the ‘structural characteristics of communities of practice’ (Citation1991, p. 55). The centrality of developing an identity through participation, engaging in professional activities and acquiring knowledge are core aspects of membership. Voll et al. (Citation2021), writing specifically about the transition from social work student to qualified practitioner, suggest this transition reflects the social learning environment which is ‘entered as an individual, with their own background, and having to find their own way to become a full member of a community of practice’ (Citation2021, p. 9).

Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) thinking on legitimate peripheral participation emerged from their earlier work on apprenticeship. This evolved into an exploration of situated learning and, from this, legitimate peripheral participation as an analytical perspective. They posit that ‘activities, tasks, functions and understanding do not exist in isolation. Learning involves the construction of identities’ (Citation1991, p. 53). Social work education in Northern Ireland exists through the interconnectivity of a range of communities of practice, including statutory agencies, voluntary sector agencies, criminal and youth justice agencies, education and independent sectors, students, service users, academics, practice teachers and the overarching governance of the regulator, the NISCC.

Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) argue that it is the community of practice which creates the opportunities for learning, and they reframe this as ‘that which may be learned by newcomers with legitimate peripheral access’ (Citation1991, p. 93). This is reflected in social work education in Northern Ireland whereby the regulator in partnership with higher education institutions (HEIs) agrees what must be learned by social work students from the pre-qualification (undergraduate) stage to the Professional in Practice (PiP, postgraduate) stage. For Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 37), ‘learning is an integral and inseparable aspect of social practice’. Practice teachers are the gatekeepers to the profession (Finch, Citation2015; MacDermott & Harkin-MacDermott, Citation2021) assessing the competence and professional development from social work student to social work practitioner; the evolving skills, knowledge and characteristics associated with membership and participation in communities of practice which generate opportunities to learn and to make sense and meaning of these experiences. Ferguson (Citation2022) writing about the continued professional development of social workers in Scotland posits how individuals learn, their perceptions about what they need to learn and the ways learning is supported in their workplace are significant influencing factors on what social workers learn.

Personal reflections: practice teaching, practice learning and professional competence

As an accomplished practice teacher, I am acutely aware of the significance of the relationship between the practice teacher and the student. In the initial stages of my supervisory relationship with every student, I explore issues of power, using Doel et al. (Citation1996) ‘Who Am I?’ exercise as a mechanism to begin to open up a dialogue about actual and perceived power. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 36) acknowledge the role of power and opine that how it is used can serve to influence legitimate peripheral participation as either an ‘empowering’ or a ‘disempowering’ experience. Understanding the dynamics and significance of the practice teacher–student relationship is central to measuring how the placement experience is progressing. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (Citation2015) discuss knowledge hierarchies among professions; within social work education, a placement is often students’ first experience of professional power and legitimate professional authority. Whether reluctantly or not, the practice teacher occupies the role of gatekeeper to the profession, and within this there is a distinct power imbalance (Grady & S, Citation2009). Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (Citation2015, p. 13) posit that ‘learning as a social process always involves issues of power’. Finch (Citation2015) provides evidence that practice teachers remain reluctant to fail students on placement and identifies this as another contributor to the low failure rates on social work programmes in the UK. One of the main findings of the research presented in MacDermott and Campbell (Citation2015) is that 88% of the 121 students in the study rated their relationship with their practice teacher as either ‘extremely important’ or ‘highly important’ (p. 38).

The placement landscape offers the space for students to begin to explore their personal and professional social work identity. In the UK context, an increasing emphasis is placed on statutory social work (MacDermott, Citation2019; Wiles & Vicary, Citation2019). Practice teachers and social work students must recognize that professional identity is formed across multiple practice contexts, and it is unhelpful to have a polarized view on what constitutes ‘real social work’ (MacDermott, Citation2019).

The importance of professional supervision in work-based learning and the specific role of the practice teacher as a gatekeeper to the profession should not be underestimated. The practice teacher is responsible for assessing whether the social work student is competent enough to progress to the next stage of learning or to enter the workforce as a newly qualified social worker. Wenger (Citation1998) discusses the relationship between the educator and the learner, with the educator acknowledged as a rich source of learning. It is typical for placement experience to be measured by the student’s ability to perform the tasks associated with the role and to demonstrate technical competence. Supervision with a practice teacher is an anchor and requirement of the social work placement experience. It is during supervision that the student must learn to articulate how tasks were completed, the theories they considered to complete the work, how they attempted to apply these in practice, whether the theory they used to inform them and the theory they relied on to intervene were successful or not and what could be changed if the particular or a similar circumstance should arise again. Bellinger (Citation2010, p. 2460) underlines the importance of ‘enabling students to critique their own practice and that of others’. Higgs (Citation2021) provides evidence of the need for social work students to explore their feelings about the rights of service users versus the finite resources of the relevant agencies and the tension this creates when assessing service users’ needs.

Mentoring a newly qualified practice teacher afforded the author an opportunity to critically reflect on 15 years of experience as a practice teacher. The significance of creating learning opportunities and structured activities to shape social work students’ learning on placement and to promote conversations about how they are learning from the various feedback loops available to them (service users, practice teachers, peers, agency staff, collaborative working). These activities demonstrate professional learning in a practice learning landscape which involves problem solving and asks that students have the capacity to consider who they are and what they bring to the experience (Doel, Citation2010). Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 29) suggest that

legitimate peripheral participation provides a way to speak about the relations between newcomers and old-timers, and about activities, artefacts, identities and communities of knowledge and practice. It concerns the process by which newcomers become part of the community of practice.

Transformative learning: from newcomers to old-timers

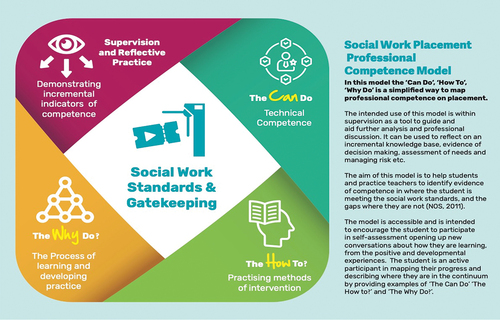

Reflection, critical thinking and problem solving are elements of the shared repertoire (Wenger, Citation1998) in the overlapping communities of practice in social work education. Wenger articulates the importance of reflection and of being aware (as individuals) of the alternative ways we interpret and make sense of our lived experiences. Thinking reflexively can help to identify alternative ways of engaging in practice and promote better outcomes for service users and experts by experience by avoiding routinization MacDermott & Harkin-MacDermott (Citation2019). Professional supervision offers a learning context to engage in reflection and to challenge and make sense of personal values and beliefs. Reflective practice and supervision are included in the Social Work Placement Professional Competence Model () to illustrate the pivotal and significant developmental influences that these activities have on understanding and acknowledging that change, challenge, adaptability and debate are central to sustaining communities of practice in social work education which are responsive to improving outcomes for service users.

The Social Work Placement Professional Competence Model () is a heuristic that is designed to be used within the social work placement setting. The Model is influenced by the author’s perspectives on Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and Wenger (Citation1998). This Model draws on the author’s extensive experience as a practice teacher and academic, it is designed to be a conceptual shortcut, a heuristic to make sense of what constitutes good-enough practice for a social work student on placement. The model reflects elements of Wenger’s (Citation1998) mutual engagement, that is, by learning together as a practice teacher and social work student in professional supervision. The domain of joint enterprise is evident, in that, part of the role of the ‘oldtimer’ (practice teacher/practice educator) is modeling professional socialization and supporting the formation of a professional identity of the ‘newcomer’ (social work student). In essence, this is a problem-solving model designed to help students and practice teachers to organize experiences of assessment, observations of practice and feedback loops. Wenger refers to this as developing ownership and mutual accountability in agreeing ‘what actions are good enough and when they need improvement or refinement’ (Citation1998, p. 81). Cumulatively, these are evidence of the competence of the student’s practice on placement and validate that the professional standards are being met or confirm that they are not being met.

The model () has three distinct domains in the social work education practice learning context, which I have named as follows:

The ‘Can Do’ Domain.

The ‘How To?’ Domain.

The ‘Why Do?’ Domain.

When incremental learning indicators are not being met, the journey toward achieving a successful placement becomes difficult, but it does not have to be insurmountable; the situation will depend on the specific issues identified and the timing of these. Supervision and reflective practice are instrumental to agreeing a time-limited action plan identifying naturally occurring learning opportunities which will enable the student to demonstrate and provide concrete examples of ‘The Can Do’, ‘The How to?’ and ‘The Why Do?’. If action planning is unsuccessful, the student’s professional learning journey must end at this juncture, and the practice teacher’s assessment will be that they are not competent at this point. In Northern Ireland, if a practice teacher identifies fitness to practice concerns because of their assessment of whether or not a student is competent, a referral to the NISCC and the university is required (Northern Ireland Degree in Social Work Partnership [NIDSWP], Citation2023; Northern Ireland Social Care Council [NISCC], Citation2019b).

Applying the placement professional competence model in supervision

Below is an example of how I have applied the Social Work Placement Professional Competence Model in supervision. In this example, the student had completed her first placement in the statutory sector and was struggling to identify the social work role in a voluntary sector agency. As preparatory work, I asked the student to complete two tasks, some reading on perceptions of voluntary sector social work in Northern Ireland and to shadow a colleague presenting at a multi-disciplinary safeguarding meeting.

The ‘can do’ domain (technical competence)

The student reflected on what she had read, questioning early messages on developing her professional identity and her initial perceptions of voluntary sector social work. She discussed how her experience of university teaching was heavily influenced by statutory practice and a perceived status associated with statutory tasks. She expected to complete more paperwork on this placement.

We explored the strengths in her practice, what she feels comfortable doing, reflecting on her experience of shadowing, and what she feels she can do within the context of contributing to a safeguarding meeting. The student identified the importance of interagency partnership and communication in the risk assessment and decision-making processes of the meeting. She also witnessed what she described as ‘uncomfortable conversations’ with the parents. We spent time discussing the learning from this with the student identifying what skills and knowledge she can bring to this work on placement.

The ’how to’ domain (practicing methods of intervention)

Having identified the skills and knowledge the student can bring, we agreed that the student will present at the next safeguarding meeting. I used a range of prompt questions to explore how she will prepare for this.

How will you explain your role at the safeguarding meeting?

Talk me through how you will demonstrate those specific skills.

How will you differentiate between acceptable and unacceptable risk?

How will you demonstrate your professional knowledge at the safeguarding meeting? Why is this important?

How do you assess good enough parenting? Consider your own values and experiences of being parented or being a parent.

How will you seek feedback from the parents/carers during the meeting? How will you manage ‘uncomfortable conversations’ with parents and other professionals?

Tell me how you will manage power differentials (either perceived or real) during the safeguarding meeting? What have you read about the validity of professional identities across practice contexts?

Tell me how the theories we have discussed today (to inform and to intervene) will apply to your role.

The ‘why do’ domain (transformative learning and development)

Working together in supervision, we explored the importance of understanding that professional social work is delivered across a range of practice contexts and the significance of building and sustaining relationships with parents and children to support early intervention approaches. We discussed the value attached to having conversations, being present and listening to the lived experiences of others, and how this helps to build a picture of the strengths, issues, challenges and resources families are working with. Below are some of the prompt questions used to explore the ‘Why Do’ Domain.

Why is the student pushing herself out of her immediate ‘comfort zone’ an important element to developing her practice and testing her own levels of competence?

Why is multi-agency partnership working essential? Reflective discussions on key learning from Case Management Reviews (NI), Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews (England), Learning Reviews (Scotland) and Child Practice Reviews (Wales).

Why is advocacy important? How does this support social justice and human rights in social work practice? Think about micro and macro approaches to improving the lives of families.

Articulating why critical reflection and ongoing professional discussions in supervision are integral to understanding our personal and professional identities.

Why as social work students and practice teachers we must be open to alternative ways of practicing social work, recognizing the continuum of lifelong learning associated with being a professional social worker.

Returning to Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, p. 53) and their perspective on the person and identity in learning. In their analysis,

learning involves the whole person and their relation to social communities … learning thus implies becoming a different person with respect to the possibilities involved in the construction of identities.

Applying Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) analysis to my observations of the multiple synchronized identities in social work education student’s learning is characterized by what Gibbs (Citation2004, p. 173) refers to as ‘the scholastic processes of conversation, involvement and engagement as modes of revealing knowledge’. Social work education involves transformative learning which seeks to challenge the status quo on how social work education is defined by exploring the relational, emotional and political and acknowledging that learning is a social process (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Mezirow (Citation2000) defines transformative learning as learning which results in questioning beliefs and considering alternative ways of processing, reflecting on and understanding different perspectives. Mezirow maintains that transformative changes in perceptions and world views can occur by people ‘trying on another’s point of view’ (Mezirow, Citation2000, p. 21). Ferguson (Citation2023, p. 75) in her research with experienced social workers in Scotland notes that [they] ‘learned through work tasks about the importance of understanding the unique lives of people’ (p. 75).

While Mezirow (Citation2000) highlights reflection as integral to transformative learning, Wenger (Citation1998) views practice and the process of learning through active engagement as essential, placing the emphasis on the relationship between the learner and the social context in which they are learning. This is reflected in the knowledge section of the global definition of social work, which asserts that

[t]he uniqueness of social work research and theories is that they are applied and emancipatory, much of social work research and theory is co-constructed in an interactive dialogic process. (International Federation of Social Workers, Citation2014)

Conclusion

The Social Work Placement Professional Competence Model (PPC Model) draws on the author’s perspectives of Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) positioning regarding activities and identities within communities of knowledge and practice which can provide direction and encouragement to newcomers. The model aligns with the concept of the Learning Loop (Argyris & Schon, Citation1978), in which single loop and double-loop reflection can occur during professional supervision. The author posits the Social Work Placement Professional Competence Model () represents the iterative nature of professional learning where the learning and development of the social work student is evolving as they consider the ways in which they experience their learning on placement and critically reflect on their reasoning and decisions and the implications of these for future practice. The model is intended to enhance student self-assessment creating a mapping framework for students to articulate what they can do (technical competence), why they are doing it (transformative learning and development) and how they can do it (practicing interventions). The model is structured to challenge power dynamics, either perceived or real, in professional supervision, promoting open discussions and agreeing incremental indicators of competence on how the student is learning to become a professional social worker.

The Social Work Placement Professional Competence model presented in this teaching note focuses on pre-qualifying social work education. The author posits the model is adaptable and can be used across pre-qualifying and post-qualifying social work education. For example, with newly qualified social workers (NQSWs) as a supervisory model for the Assessed Year in Employment (AYE, Northern Ireland) or similar approaches employed for NQWSs in the United Kingdom, Europe and North America. Potential next steps include integrating the model into learning and teaching for pre-qualifying social work students, trainee practice teachers and established practice teachers. The model will be integrated into existing resources as part of the shared repertoire for social work education across a range of communities of practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organisational learning: A theory of action, perspective. Addison Wesley.

- Bellinger, A. (2010). Talking about (re)generation: Practice learning as a site of renewal for social work. British Journal of Social Work, 40(8), 2450–2466. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq072

- Campbell, J., Duffy, J., Traynor, C., Coulter, S., Reilly, I., & Pinkerton, J. (2013). Social work education and political conflict: Preparing students to address the needs of victims and survivors of the troubles in Northern Ireland. European Journal of Social Work, 16(4), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.732929

- Campbell, J., Ioakimidis, V., & Maglajlic, R. A. (2019). Social work for critical peace: A comparative approach to understanding social work and political conflict. European Journal of Social Work, 22(6), 1073–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1462149

- Coulter, J., & Duffy, J. (2023). Living through it, living after it: Personal reflections on ‘the troubles’ in Northern Ireland. Peace Review, 35(3), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2023.2218816

- Cournoyer, B. (2011). The social work skills workbook (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning.

- Darby, J. (1995). Conflict in Northern Ireland: A background essay. In S. Dunn (Ed.), Facets of the conflict in Northern Ireland (pp. 15–23). Macmillan.

- Department of Health. (2020). Deployment of newly qualified social workers.

- Department of Health. (2021). Social work workforce review. DoH.

- Doel, M. (2010). Social work placements: A traveller’s guide. Routledge.

- Doel, M., Shardlow, S., Sawdon, C., & Sawdon, D. (1996). Teaching social work practice. Arena and Ashgate.

- Duffy, J., Campbell, J., & Tosone, C. (2019a). International perspectives on social work and political conflict. Routledge.

- Duffy, J., Campbell, J., & Tosone, C. (2019b). Voices of social work through the troubles ( Publication arising from workshop, 21 November 2019). BASW NI and NI Social Care Council.

- Edmonds-Cady, C., & Sosulski, M. R. (2012). Applications of situated learning to foster communities of practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 48(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2012.201000010

- Farnsworth, V., Kleanthous, I., & Wenger-Trayner, E. (2016). Communities of practice as a social theory of learning: A conversation with Etienne Wenger. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1133799

- Ferguson, G. (2022). Influences on professional learning in the workplace. Retrieved January 29, 2024, from https://www.nqsw.sssc.uk.com/promoting-nqsw-professional-learning-and-development-in-the-supported-year/

- Ferguson, G. (2023). “When David Bowie created Ziggy Stardust” reconceptualising workplace learning for social workers. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 20, 1. https://www.journals.whitingbirch.net/index.php/JPTS/article/view/1932

- Ferguson, I. (2008). Reclaiming social work: Challenging neo-liberalism and promoting social justice. Sage.

- Finch, J. (2015). Running with the fox and hunting with the hounds: Social work tutors’ experiences of managing failing social work students in practice learning settings. British Journal of Social Work, 45(7), 2124–2141. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu085

- Fook, J. (2015). Reflective practice and critical reflection. In J. Lishman (Ed.), Handbook for practice learning in social work and social care knowledge and theory (3rd ed., pp. 440–454). Jessica Kingsley.

- Fook, J., Ryan, M., & Hawkins, L. (2000). Professional expertise: Practice, theory and education for working in uncertainty. Whiting and Birch.

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further education unit. Oxford Polytechnic.

- Gibbs, P. (2004). Trusting in the university: The contribution of temporality and trust to a praxis of higher learning. Kluwer Academic.

- Grady, M. D., & S, M. (2009). Gatekeeping: Perspectives from both sides of the fence. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 79(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377310802634616

- Gray, I., Parker, J., & Immins, T. (2008). Learning communities of practice in social work: Groupwork or management. Groupwork, 18(2), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1921/81123

- Gray, I., Parker, J., Rutter, L., & Williams, S. (2010). Developing communities of practice: A strategy for effective leadership, management and supervision in social work. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 14(2), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1921/174661010X537199

- Higgs, A. (2021). The England degree apprenticeship: A lens to consider the national and international context of social work education. Social Work Education, 41(4), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1873935

- Huntley, M. (2002). Relationship based social work: How do endings impact on the client. Practice, 14(2), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150208414302

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2014). Global definition of social work. Retrieved October 25, 2023, from https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- MacDermott, D. (2019). Even when no one is looking: Student’s perceptions of social work professions. A case study in a Northern Ireland university. Education Sciences, 9(3), 233, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030233

- MacDermott, D. (2023). A chronology of the history and development of social work education in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2275650

- MacDermott, D., & Campbell, A. (2015). An examination of student and provider perceptions of voluntary sector social work placements in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 35(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1100289

- MacDermott, D., & Harkin MacDermott, C. (2019). Co-producing a shared stories narrative model for social work education with experts by experience. Practice, 32(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2019.1704235

- MacDermott, D., & Harkin MacDermott, C. (2021). Perceptions of trainee practice teachers in Northern Ireland: Assessing competence and readiness to practise during COVID 19. Practice, 33(5), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2021.1904868

- MacDermott, D., & McCall, S. (2017). The supervisory relationship in practice learning. In C. McMullin & M. McColgan (Eds.), Doing relationship based social work: A practical guide to building relationships and enabling change (pp. 147–162). Jessica Kingsley.

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass.

- Northern Ireland Degree in Social Work Partnership. (2023). Practice learning handbook.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2009). The five year periodic review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2014). The second periodic review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2015). Framework specification for the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019a). Report 14: Review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019b). Standards of conduct and practice for social work students.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council (NISCC). (2021). Review of practice learning. NISCC.

- O’Brien, B. C., & Battista, A. (2019). Situated learning theory in health professions education research: A scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(2), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.10007/s10459-019-09900-w

- O’Connor, R., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2014). Adolescent self harm: A school-based study in Northern Ireland. Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.015

- O’Neill, S., & O’Connor, R. (2020). Suicide in Northern Ireland: Epidemiology, risk factors and prevention. Lancet, 7(6), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30525-5

- Roberts, L. (2011). Ending care relationships: Carer perspectives on managing ‘endings’ within a part time fostering service. Adoption & Fostering, 35(4), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857591103500403

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Tedam, P. (2012). The MANDELA model of practice learning: An old present in new wrapping? The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 11(2), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1921/jpts.v11i2.264

- Thompson, S., & Thompson, N. (2008). The critically reflective practitioner. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Voll, I., Barmen-Tysnes, I., & Larsen, A. K. (2021). The challenges of combining ‘knowing-that’ and ‘knowing-how’ in social work education and professional practice in the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration. European Journal of Social Work, 25(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1964441

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Harvard University Press.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Learning in a landscape of practice: A framework. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, & B. Wenger-Trayner (Eds.), Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity and knowledgeability in practice-based learning (pp. 13–30). Routledge.

- Wiles, F., & Vicary, S. (2019). Picturing social work, puzzles and passion: Exploring and developing transnational professional identities. Social Work Education, 38(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1553236

- Wylie, S., & MacDermott, D. (2017). Looking through the lens at endings: Service user, student, carer and practice educator perspectives on endings within social work training. In C. McMullin & M. McColgan (Eds.), Doing relationship based social work: A practical guide to building relationships and enabling change (pp. 177–192). Jessica Kingsley.