ABSTRACT

As responsive social work education is about meeting the dynamic needs of learners, social work educators engage with innovative approaches that promote teaching and learning (TAL). The purpose of this article is to address the research question: Based on our experience as educators, what TAL methods can support social work and human services curriculum delivery in an online environment? Using the co-operative research method and analyzing our reflections, we proposed a model of curriculum delivery which conceptualizes the application of four methods of TAL (pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy, and paragogy). We also illustrate how this teaching approach can promote different levels of learning (single, double, and triple- loop learning). The model is based on internationally agreed principles of social work and can incorporate non-Western and Indigenous learning processes. We argue that when educators and learners use these four methods in different combinations, it is possible to produce learning experiences that augment social work skills and knowledge development, as well as prepare learners for a multi-dimensional world of change. The implication is that there is scope in the presented model to promote transformational learning and ways of positive engagement during social disruption and dynamic change, both features in our current global environment.

Introduction

This article discusses the application of four learning-teaching methods—pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy, and paragogy—in preparing social work students for practice in an online environment. The authors share their experience and analysis of employing these teaching and learning (TAL) methods and present an adapted model of education which can provide academics and practitioners with additional strategies for effective social work education and training.Footnote1

The process of educators deepening consciousness regarding contemporary TAL has gained prominence in the second half of the 20th Century (Manojan, Citation2019, p. 124; Wood, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In response, the aim of this article is threefold. First to outline the authors’ critical reflections on the flexible application of the TAL approaches within an online environment. Second, as social work educators, the authors present our experiences in preparing social work students for practice. Third, we reexamine Wood’s (Citation2017a) model of TAL, which was developed pre-pandemic. Wood’s (Citation2017a) model developed out of a consideration of achieving excellence in higher education and it places ‘teaching within a wider framework of complex adaptive systems’ (p. 56): curriculum, learning assessment and teaching. At the center of this model is the student and teacher, and their interactions. His model (Citation2017b, p. below) to show how the different methods of TAL can be woven together to meet not only the educational requirements of higher education institutions but also be responsive to the dynamism required by our current world experiences with attention to cultural and geopolitical diversity.

For conceptual clarity, the teaching methods are defined for this article as follows and their respective main features and assumptions are summarized in . Pedagogy refers to teacher-centered/dominated/controlled/led/determined TAL practices relating to curriculum design, educational methods, choice of teachers and facilitators, practice exercises, case studies/examples, assessments, and feedback mechanisms. Teacher-centered learning assumes that the teacher is the primary source of knowledge and the facilitator of learning (Blumberg & Weimer, Citation2009). Andragogy connotes the use of adult learning principles to enable student-centered TAL practices (Knowles, Citation1984a, Citation1984b; Knowles et al., Citation2012; Mews, Citation2020). The learner can choose topics and learning projects (Tough, Citation1971). The underpinning assumptions are that adults come with experiences and existing knowledge that can be considered strengths and capacities and which can be used as anchors for new concepts so that learning is integrated, connected to life, and relevant. In heutagogy, students take control to determine and direct TAL activities. Essentially, the student or learner is ‘in the driver’s seat’ and teachers only play a facilitating role when needed. In heutagogy, the learning objectives can still be set by standards and curriculum developers. How the student achieves the learning is flexible. Heutagogy is used in social work, particularly in field education. It sometimes includes the learner teaching the lecturer/practitioner/and others new technologies or novel ways of using existing technologies. Paragogy is a further extension of heutagogy where learners/peers, analyze and co-create the educational environment in which they learn from each other by setting aside their diverse backgrounds and even educator and learner differences, sharing their understanding, raising questions and doubts, and by seeking and offering clarifications and resources (Bassendowski, Citation2016; Raw, Citation2016).

Table 1. The main elements of the four teaching-learning methods.

Irrespective of different TAL models, theories or approaches, the core focus of teaching is on people and learning, through engagement with the curriculum, and the theory of learning (UNESCO IBE, Citation2021). Alongside these ideas, social work education has a further focus or dimension, that is, aligning with social work professional ethical principles and knowledge (Australian Association of Social Workers, Citation2020, Citation2021; International Federation of Social Workers, Citation2020, p. 8.1).

More recently, pedagogy, as a classic TAL method within social work education, has come under considerable critique due to its overemphasis on the teacher-centered activities sometimes at the neglect of the learner (Strauss et al., Citation2014). The limitations of pedagogy occur along the lines of the person learning having limited power and control, whilst the teacher has full responsibility for learning. Within this relationship there are some cultural and risk mitigation principles requiring consideration. For instance, regarding colonizing approaches, colonizers bring education to others, they decide what is knowledge, the language used, how this will be delivered—the resources made available—and how knowledge and skills are to be examined and credentialled (Poitras Pratt et al., Citation2018). In contrast, social work education practices are framed as humanistic and enabling people to have the tools to exercise their rights and responsibilities (Meszaros & Baroti, Citation2016).

In response to the critique, we argue that education can enable human rights, facilitate social mobility, and enhance well-being. It aligns with international commitments to education for all as articulated in Article 26 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensuring inclusive, equitable, and quality education and the promotion of lifelong learning opportunities for all are key examples of this commitment (United Nations, Citation1948; United Nations & Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Citation2023).

Reviewing adult approaches useful for social work education

Learning happens along a continuum of ever-evolving patterns caused by sometimes chaotic processes, disruptive influences, ebbs, and flows. Edouard Lindeman was a social worker in the early 1900s, practicing and teaching the facilitation of group work to enhance the learning of adults. He was predominantly known as the ‘father of andragogy’, creating the ‘framework of discourse and analysis predominant in adult education’ (Brookfield, Citation1987, p. 1). Compared to contemporary thinking about the sound pedagogical focus required to ensure both learner and teacher experience is at the forefront of effective curriculum design and delivery, Lindeman conceptualized ‘adult education as a collaborative, informal, yet critical exchange between learners and teachers’ (Brookfield, Citation1987, p. 1). This conceptualization has been pivotal in guiding our thinking about how to enact, with genuine impact, the concepts, and principles of adult education. Lindeman’s work predates that of other prominent adult educators, such as Malcolm Knowles, Stephen Brookfield, Terrence Lovett, and Elias and Merriam, by at least 50 years (Lindeman, Citation1926). He consciously wrote about adult education when it was in its pre-paradigmatic state, as education for social action and change. Since andragogy is seen as the ‘art and science of helping adults to learn’, it makes sense to understand a practice that excels in facilitating and accommodating self-directed learning within a variety of appropriate and relevant learning contexts.

Focusing on adult learning principles, andragogy enables student-centered TAL practices (Knowles, Citation1984a, Citation1984b; Knowles et al., Citation2012; Mews, Citation2020). The key andragogical principles operating in social work education are that educators develop an atmosphere conducive to learning. We assist the student to develop realistic expectations. We provide a relaxed, trust-filled learning environment. We respect the student’s life experiences and connect learning materials to their realities. Students are involved in the planning processes for TAL. We provide flexibility and encourage participation, considering people as valuable resources to achieve the learning objectives. We involve students in the evaluations and reviews of learning (Chan, Citation2010; Delgado, Citation2016). Andragogy, by facilitating a learner-centered approach, overcomes any limitations confined to pedagogy.

In their theoretical framework to design personalized learning paths, Karoudis and Magoulas (Citation2016) conceptualized a cumulative learning continuum that includes pedagogy through andragogy to heutagogy. Based on Canning’s (Citation2010, p. 63) work, Blashke (Citation2012, p. 60) discusses this continuum in terms of progression at three levels, from the educator’s control to the learner’s autonomy. Level one is pedagogy (engagement), level two is andragogy (cultivation), and level three is heutagogy (realization). Canning states that as the learner moves at different levels, the educator’s role changes from building confidence (level 1) to supporting shared meaning and understanding (level 2) to facilitating a desire to investigate one’s own learning (level 3). By comparing six learning theories—cognitivism, connectivism, heutagogy, social learning, transformative learning and Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development – Brieger et al. (Citation2020) emphasize the significance of matching theories with an instructional situation and background of the learners. Further, the integration of different learning approaches such as informal, non-formal, and formal is emerging as a new learning model (Garnett & Ecclesfield, Citation2015). From a social work education and training perspective, a transformative theory is pertinent as it involves improvement in knowledge, skills, ability and attitudes and to challenge the status quo (Brieger et al., Citation2020).

By analyzing 33 published articles and other relevant literature, Moore (Citation2020) found that heutagogy is discussed as an emerging instructional approach facilitated by technology and online environment, humanism and constructivism in a continuum with pedagogy and andragogy. Further, Moore’s analysis suggested that workplace environments, including online learning, higher education, medical education, professional development, and massive open online courses (MOOCS) were conducive to heutagogy. From the literature, Blaschke (Citation2021, p. 1633) identifies four principles of heutagogy: learner agency; self-efficacy and capability; reflection and meta recognition; and non-linear learning. These principles are relevant in social work training and practice as they facilitate multiple loops of learning beyond single (engaging with what to learn and correcting errors) and double-loop learning (engaging with assumptions, variables and actions associated with learning) to triple-loop learning (engaging with how we learn what we learn and why) (Blaschke, Citation2021; Eberle & Childress, Citation2009; Hase & Kenyon, Citation2001; Schon, Citation1983; Tosey et al., Citation2012).

In heutagogy, learner-centered and determined learning utilizes a range of teaching methods that collectively create an environment for learning (Blumberg & Weimer, Citation2009; Hase & Kenyon, Citation2001). Heutagogy can help achieve ‘increased learner engagement and motivation, higher levels of learner self-efficacy, … competency and capability’ (Agonács & Matos, Citation2019; Blaschke, Citation2021, p. 1633; Moore, Citation2020). In a case study, Blaschke (Citation2021, p. 1641) ‘found that students demonstrated the development of important lifelong learning skills such as autonomy, communication and collaboration, critical thinking, reflection, self-directedness, self-management, and self-regulation’.

Despite its strengths, it is not always possible to implement heutagogy in social work education. A point of difficulty in implementing and sustaining this approach occurs when powerful accreditation/regulatory bodies remain wedded to pedagogy-oriented assessment practices and prescribed curricula (Blaschke & Hase, Citation2015; Moore, Citation2020). While there is an important need and appreciation for standards and quality issues relevant for the funding of educational institutions and ensuring competent and capable social work graduates, there is also a need for consideration of the nature of social work. Social work practitioners are required to act with confidence, to be empowered and empowering, embrace learning, and engage with others, by sharing stories and relational connections. They are required to demonstrate deep stillness and curiosity in dealing with members of the community and their concerns. These are core capabilities for social workers and so are central to our curricula. They are taught by the way we engage with learning and the methods we use in our teaching.

Regarding paragogy, Zha et al. (Citation2019) analysis showed that peer-led learning facilitated higher cognitive achievement than non-peer-led learning. Similarly, Goldingay and Land’s (Citation2014) study confirmed that ongoing peer interaction produces deeper and enduring learning experiences. Bassendowski (Citation2016) underscores peers’ learning as they help each other to manage, organize and review subject content (see also Sengupta & Sengupta, Citation2018). Lee and Rofe’s (Citation2016, p. 126) research showed that all learning that occurs among peers cannot be fully captured through assessments, even students’ grades reflect only part of the rich learning, and there was little correlation between levels of engagement and formal assessment results. Raw (Citation2016) is radical in stating that both educators and learners should participate in learning events by sharing their experiences to create adaptive learning communities that do not differentiate between learners and educators but commit to mutual support and progress. To Mulholland (Citation2019), paragogy has the potential to become one of the transformative educational developments in the twenty-first century (see also Najib, Citation2013).

Paragogy and its capacity to disrupt is not new to social work. Paragogy is in our DNA. It is a constant feature of social work education and practice especially when learning from peers in case conferences, seminars, symposia and conferences, and peer led skills training within a variety of organizational contexts. It can be traced back to Mary Richmond’s call to transfer ‘know how’ to the following generations of social workers and which led her to write Social Diagnosis in 1917. Paragogy is where our profession generates its practice knowledge. We encourage all social workers to be engaged in supervision (Pawar & Anscombe, Citation2022) and to reach out to peers when encountering a novel or tricky situation. We encourage coaching for skills development and mentoring. We encourage colleagues to be engaged with the professional association’s activities and workshops.

As there is a lack of adequate evidence, further studies are recommended in online learning environments (Agonács & Matos, Citation2019; Blaschke, Citation2021; Brieger et al., Citation2020; Moore, Citation2020). Agonács and Matos (Citation2019) show that capability development and non-linearity are underrepresented in research. Moore (Citation2020, p. 396) also suggests teachers ‘explore opportunities to integrate heutagogical approaches into the curriculum … ’ (see also Snowden et al., Citation2016). Similarly, Brieger et al. (Citation2020) advocate establishing the effectiveness of various learning theories in different learning situations. Although peer assessment activities were more adequate for providing feedback than discussion forums, Elizondo-Garcia and Gallardo (Citation2020) recommend further research to understand the factors influencing peer interaction and feedback and to develop strategies to improve peer feedback effectiveness. In recognition of mobile technology and ubiquitous learning, Khoo (Citation2019) proposes a stronger connection between mobile technology integration and a learning-theoretical framework to guide research, practice, and policy. Considering these comments and suggestions for further research and adaptations to the changing environment in terms of technological, organizational and learners’ values and expectations (French & O’Leary, Citation2017; Wood, Citation2017a), it is necessary to think of new ways of TAL (Garnett & Ecclesfield, Citation2015; Monk et al., Citation2015; Snowden et al., Citation2016). In addition, our review suggested that although these learning methods have been researched independently and or in combination, we did not come across any research that explicitly attempted to integrate all four of them without being bound by the continuum of linear progression.

Based on this need to integrate pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy, the objectives of this article are to explore the application of the four learning methods in preparing social work students for practice in an online environment, and to present an adapted model of education which can provide academics and practitioners with additional strategies for effective human services education and training.

This article addresses the research question: Based on our experience as educators, what methods of learning and which teaching strategies can support social work and human services curriculum delivery in an online environment?

Methodological approach

Scholars such as Boud et al. (Citation1985, p. 34), Ospina et al. (Citation2008) and Perry (Citation2023) highlight the importance of the reflection process within research about learning, proposing that this process readies educators for new experiences (Pawar et al., Citation2004; Short & Healy, Citation2017). These scholars recognize the usefulness of co-operative inquiry as a research approach that promotes collaborations and structuring reflection on experiences (Boud et al., Citation1985, p. 17; Ospina et al., Citation2008; Perry, Citation2023). Due to its recognized utility in structuring research which promotes reflexivity and reflection, co-operative inquiry was deemed the appropriate methodology for this project.

Pioneered by Heron and Reason (Citation1997), co-operative inquiry is a participatory research approach where people research with each other (Reason & Heron, Citation1995). This methodology considers people capable of engaging research and containing the ability to address the intricacies of learning environments (Heron & Reason, Citation2008; Pawar et al., Citation2021; Short, Citation2018).

Authors’ positionality

In this inquiry, every one of us as a coauthor was the co-participant, co-subject and co-inquirer (Heron & Reason, Citation1997). We are all experienced educators from a regional university. Our university has campuses throughout Australia and classes are face-to-face, online or blended—synchronous and asynchronous. We are all interested in the relationship between pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy, and how together they can promote effective learning during periods of social upheaval. In alignment with the methodology, we decided to include first-person language in the article.

Co-operative inquiry

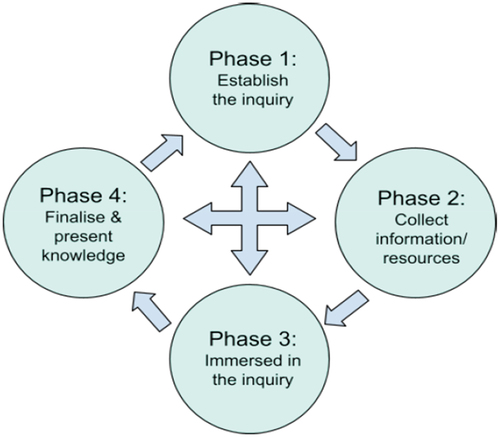

Co-operative inquiry provided rigor and structure to our reflections by capturing the spectrum of thinking concerning teaching approaches presented below, facilitating reflection and reflexive thinking regarding teaching online, and ensuring findings were congruent with each of our present experiences of teaching. This methodology involves cycling through four phases (Heron & Reason, Citation2008), see .

Figure 1. Co-operative inquiry phases (Pascoe et al., Citation2023; Reason & Heron, Citation2013; Short & Healy, Citation2017, p. 190).

In phase one, the focus area and research team were initiated, and the inquiry was established (Heron & Reason, Citation1997; Short, Citation2018). We began sharing experiences of applying the TAL continuum. Due to the four of us being located in three different states of Australia and each state impacted by COVID-19 lockdowns, we decided to communicate primarily through online platforms. Next, we reflexively and critically examined our own experiences, and this became our data. Second-party, third-party, incidental or sensitive data was not collected. Ethics committee approval was not required as this inquiry was deemed to be a nil-to-negligible risk project.

In phase 2, the focus area was narrowed, and information and resources collected (Short & Healy, Citation2017). We centered on the TAL continuum, especially on strategies that facilitate students’ learning in a dynamic online environment. In this phase, Dr. Lynelle Osburn proposed reformatting the Wood model, with a focus on the contemporary challenges in teaching social work and human service students. The reformatted model was named the ‘egg and basket model’.

During phase 3 the co-inquirers became immersed in the topic and agreed to take action (Heron & Reason, Citation1997). We presented our emerging themes regarding the eggs and basket model at an international conference (Pawar et al., Citation2021). This presentation confirmed the information we had been collecting, the usefulness of the egg and basket model and our reflections. This elucidation phase of this inquiry highlighted for us the contemporary need for critical explorations of the TAL continuum in an online learning environment.

In phase 4 the co-inquirers reflected on actions and further refined the focus and presented the knowledge (Heron & Reason, Citation1997). In this phase, we paused, revisited, and extended our insights about the intricacies of teaching and the proposed model. Our observations of how the current uncertain times caused by world crises and pandemics were accelerating online teaching established for us the need for conversations regarding transformational education, such as this one. In this phase, we analyzed the data and identified the themes presented in the next section. By integrating the interactions of the four phases, our thoughts were organized under reflections and analysis, resultant themes, and an eggs and basket model, as follows.

Reflections and analysis

Multiple loops of learning underpin our reflections and analysis. In single-loop learning, reflection is focused on achieving the adult learning task. For example, it is about highlighting the need for skills development, knowledge, a new perspective or new approach or tool. Pedagogy is a great strategy for single-loop learning.

Further, in single-loop learning, engaging strategies about innovation is possible and in this way unexpected learning outcomes are revealed. Equally, the student might show the facilitator or lecturer a new technological affordance provided by the software, that is, a capability of the technological platform being used that was not present in previous systems. The technological affordances not only transform the learning for the individual, they change the manner of subject delivery and educational assumptions.

Double-loop learning strategies, in contrast, encourage the student to examine hidden assumptions and unconscious bias critically. A common example of this is when students critically reflect on their personal ethics and their engagement with an ethical code.

Triple-loop learning strategies encompasses reflexive practice where students consider the ways they learn and how they engage with learning and the profession. Beyond actions and assumptions, students deeply examine the broader context, purpose and values. For example, discussions with First Nations researchers, practitioners, and academics as they share deep listening powerfully demonstrate this.

Strategies illustrating the relationship between single, double, and triple- loop learning and paragogy

In addition to this co-operative inquiry, our four authors participated with Charles Sturt University academics, professionals, and students in a prior and now published research project about learning social work skills online during COVID-19 (Osburn et al., Citation2021). This project assisted us with honing our thinking (Osburn et al., Citation2021). Our reflection on what happened for the members of the teaching/research team clearly showed the actions of paragogy—learning from and with peers (Osburn et al., Citation2021). For example, in further reflection on online social work skills intensives (4–5 days), we saw paragogy in the ways students interacted with each other in the facilitated groups and breakout rooms. Students shared and taught each other how to use software, and applications (single-loop learning). We saw paragogy in the moderated chats during lectures when students shared their insights, gently challenged each other’s assumptions and added additional documents, policies and web links, and made recommendations to each other on what behaviors constitute appropriate professional practice behaviors in this teaching environment (double-loop learning). The way in which student questions and comments were conveyed to the lecturer/presenter in small group breakout rooms about how people were learning and their commitment to quality transformational learning moments demonstrated respectful communication and appreciation (triple-loop learning). Best practice was being modeled by academic/professional peers and by student peers.

Resultant themes

We triangulated our emerging reflections and analysis with the literature and noted that synergies existed between our observations and the literature. All the literature found in the initial research on online learning—design, delivery and preparation for professional practice was loaded into a word cloud tool. The analysis and size of each word in the resultant graphic indicated the frequency of that word. In the word cloud, it made sense that ‘online’ featured as the most frequent term followed by ‘learning’ and ‘students’. Many of the key words were predictable. There are some which could escape immediate focus: those small words with considerable frequency like ‘also’ and ‘support’. This word cloud analysis reinforced one of Eberle and Childress’s claims (Citation2009, p. 2242), ‘Focusing on the students and their needs and empowering them to take responsibility for their learning will foster creative, capable people-ones who are ready to solve the problems that they face in the future’. The word, also, connotes inclusion. The word, support, reinforces the importance of fostering and empowering the student to be responsible and creative learners and practitioners.

Eberle and Childress, remind us that,

The heutagogical experience embraces a curriculum that is flexible and rich with double-looped learning opportunities. Differences in social characteristics are also found. In the traditional classroom, independent learning is not only stressed, but encouraged. In the heutagogical experience, not only is independent learning valued, but also collaborative learning is encouraged. (Eberle & Childress, Citation2009, p. 2242)

The shift from traditional method of teaching to self-directed learning may be challenging to some educators. But self-direction helps students to explore learning resources, raise questions, and double-loop their learning rather than just focusing on one way of finding (Eberle & Childress, Citation2009, p. 2242).

This is not new to social workers. Our profession holds the position that field education is ‘the central form of instruction and learning to socialize students to perform the role of practitioner to connect and integrate theory and practice’ (Council for Social Work Education [CSWE], Citation2008, p. 8). They call it our ‘signature pedagogy’. Field education is heutagogy. Students are supported to be self-directed, and to apply theory to practice with increasing difficulty and diversity for approximately one year. They must engage in reflexive supervision, including peer and team supervision sessions (Australian Association of Social Workers, Citation2014, Citation2021). They complete projects and write reports for professional and academic assessment. What we are seeing with online education, and from the literature, is that some of that socialization is now shared with the academy through the effective use of new technologies.

A second word cloud (see ) was generated from the text provided by the Charles Sturt University academics, professionals and students in the prior co-operative inquiry (Osburn et al., Citation2021). All the contributions that formed the data for the co-operative inquiry were the ingredients for the word cloud. There were similar words to those that appeared in the first word cloud based on the literature review and some telling differences. First, the size differential spoke volumes. The primacy of ‘students’ as the researchers’ primary concern was the central concept. The words ‘intensive’, ‘group”, and ‘collaboration’ were there. There were two surprising words, ‘felt’ and ‘also’. These were empathic and inclusive considerations. Seeing this result reinforced for us that quality, transformative, professional education is not for the anxious, the fearful or those lacking in enthusiasm. As Eberle and Childress remark, preparation for a profession, preparing capable people ready to solve future problems is, ‘not for the feint of heart or the lazy of mind’ (Eberle & Childress, Citation2009, p. 2244).

Our analysis uncovered 10 key points or themes, which are summarized in .

Table 2. Summary of resultant themes.

These 10 points remind us that academics and practitioners are interested in best educational delivery. They wonder, ‘how can we not miss out?’ on the things that new technologies provide (resources and processes) that enable us to do that were not available before. We know online is not and does not claim to be a substitute for empathy. It is not a substitute for relationship building. It is a set of platforms on which and through which those skills and techniques are delivered and taught. How we use those platforms determines whether we maintain empathy and relationship building capacity, can demonstrate it, and teach it to others online. Striving to deliver quality education involves a multidimensional, culturally responsive approach where students have space to find and share their voice about a field (Testa & Egan, Citation2014). It can also involve experimenting with technology and linking it with triple-loop learning. Online learning can encompass a range of platforms on which and through which skills and techniques are delivered and reflexively considered, such as, what is empathy, how it is delivered, and why empathy is important to social work.

One teaching strategy we have employed that promotes empathy, socially just education and reflexive thinking and uses the available technology is the provision of a time and space for students and academics to chat online, without a preformatted agenda (Atkas, Citation2021)—an availability and freedom to engage before presentations during the skills intensives. Not all spaces were about content delivery. Senior academics, facilitators and professionals were present and engaged with students to welcome them and provide a non-recorded space for conversation. It is like a free-flow chat in the foyer of the lecture theater before the doors open—a chat ‘in the round’.

A second strategy was providing the students with control over spaces for example the break-out rooms and the power to record their interactions—akin to giving students the key to the counseling laboratory rooms with the two-way mirror and the audio-visual recording equipment. We provided these as student-led online rooms. People had learned the theory in advance and then practiced online social work micro-skills, group work skills, community consultation and social action skills. Student recorded their small group interactions and critically reviewed the recordings individually—wondering how they can improve their skills and why they and their peers interacted the way they did. They had the option of discussing their insights with a tutor and could request assistance and support at any point. These heutagogical and paragogical strategies helped us respect the autonomy of the students in their learning (Charles Sturt University, Citation2022).

Introducing an ‘eggs and basket model’ for social work and human services education and training

In contemplating the current periods of social upheaval, for example, the ongoing impact of the pandemic, we recognize the need to extend our discussions about education. In comparing our findings with pre-pandemic literature (for example, Wood, Citation2017a), it appears to us that TAL has always been multi-dimensional. It seems to us that the dynamic changes increase over time for example, including indigenizing parts of the curricula, considering intersectionality and new understandings of conflict and coercive control. This reflection helped us realize that our philosophies, models and strategies of teaching need to make accommodations.

Scholars, including Wood (Citation2017a), challenge much of the dominant language and thinking within education, such as pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy, arguing that each concept and approach partially represents the TAL experience. It appears to us also that internationally, educators, students and other stakeholders have become more comfortable with online technology and its rapidly changing digital platforms. They are beginning to appreciate the technological affordances—the things that technology enables us to do that we could not do before.

Inspired by scholars such as Wood (Citation2017a), we developed a model that aimed to draw together the multi-dimensionality and dynamism of the teaching relationship and have applicability for the expanding online TAL environment for social workers and human service students.

Our findings support Wood’s (Citation2017a) model and we have redesigned it here in a more circular and encompassing manner. This is what we experienced, that we engaged in the challenges of teaching excellence, mindful of the embracing contexts. We used multi-layered collaboration and experiencing multi-dimensional personal growth within an affective foundation, consistent with our profession, and we considered that new things might emerge.

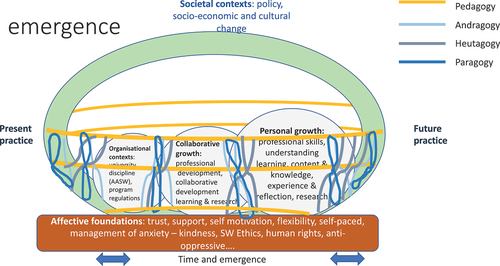

The eggs and basket model explicitly includes concepts that we found useful when designing and delivering online TAL activities. The basket is inspired by single, double, and triple-loop learning; and the teaching approaches of pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy (see ).

Figure 3. The eggs and basket model for TAL.

This proposed model presents a series of interconnecting circles. These interconnecting circles we labeled ‘eggs’. Egg 1 includes the organizational contexts that inform social work education: the university, discipline, professional bodies, programs, technology, and regulations. Egg 2 is the collaborative growth that social work students can engage in through professional development, collaborative development and learning, and research. Egg 3 is each individual’s personal growth, professional skills development, understanding of the learning—its content and deeper content and knowledge, experience and reflection, and research. We perceive educational activities as occurring within specific and varied societal contexts. Educational activities are also influenced by policies that vary within states and nations, socio-economic variations and influences that exist, in time, and culture. The overarching societal context is represented by the handle of the basket.

The base of the basket which underpins, supports and holds everything together has two layers. The first layer is informed by single, double, and triple-loop learning concepts, which are the knowledge behind what is being learned, why it is being learned (questioning assumptions), and reflections on context, values and purpose, respectively. The second layer of the basket supports (scaffolds) the learning. This second layer is our affective foundations, values, attitudes, and philosophies that inform any TAL online experience.

Further, we want to keep the eggs in the basket and so we the educators weave the TAL framework with the existing 4 strands—pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy. The patterns, we weave for our baskets will differ. They will reflect how we, apply pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy, and paragogy in the process of developing and delivering subjects based on agreed, underpinning affective foundations, mindful of our realistic organizational contexts, need and desire for collaborative growth, and the essential feature of personal growth for our students.

Strategies illustrating the egg and basket model

All this occurs within the societal contexts in which we deliver our professional programs. Depending on the context and the people involved, the strands come together in unique patterns, reflecting each unique course and each unique TAL experience. For example, one strategy in one subject is we ask students to complete weekly reflective blogs on aspects of practice analyzing the experiences with reference to academic and professional sources and generating insights, and they identify their own implications for practice and one achievable transformative action—praxis (andragogy, heutagogy and triple-loop learning). A strategy utilized in another subject is we ask students to write a critical analysis of a program somewhere in the world that serves adolescents who experience adversity. They write three blogs and group members ask them appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider & Whitney, Citation2007) questions about their blogging process (andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy with double-loop learning).

In these two strategies, it would not be unrealistic therefore, to suppose that andragogy as an educative thread can weave through all applications of education paradigms, including pedagogical, and heutagogical TAL frameworks. Additionally, it is possible to use heutagogical thinking, and see the learner as a self-determining being who takes more responsibility and ownership of their learning; there is a deliberate movement to minimize a teacher-centered approach to education, to foster a more student-centered way of enhancing learning. In both strategies, the ‘andragogical thread’ is still present in the use of the heutagogical framework, shown through the dynamic work of learning in groups, or in connection with significant tools, systems, and relationships.

On another note, pedagogical approaches to learning may appear to be the least relevant for wanting to promote insightful and critically aware adult learning. However, the andragogical thread can have some relevance even in this application. When undertaking university study, prospective social workers are advised that they cannot practice unknowingly (Pawar, Citation2016), and this double negative starts to generate initial problematizing of their foundational learning situation, with these questions: What do I need to know? Where do I get this information? What will I do with this information? Why do I need to know? How can I verify what I am being told? Fundamentally, a pedagogical approach is primarily a teacher-lead approach to TAL, but where the limitations of this approach can be easily identified along lines of limited power and control, as well as responsibility for learning, we are in the position to respond to the critical cultural and risk mitigation principles mentioned earlier in relation to colonization, based on a humanistic adult education platform.

In this article we are advocating the development of a new coherent philosophy and model of social work education accessible to all and as varied as the contexts in which courses are delivered. All the components of this new model are supported by applied research that tests the model and builds it while it is being used. This now is an exercise of drawing the blueprints of the basket while we are building it and using it.

Limitations

This inquiry is small, containing four people from one discipline—social work. It is one step by the authors to further knowledge about online education TAL approaches. Consequently, it is limited to their subjective experiences. Our thoughts and reflections were shared in online meetings and this limited the time we had together, which in may have impacted our conversations. Though we are not sure whether meetings in person would have made any difference or impacted our analysis. The co-operative inquiry method calls for significant time commitment and our workloads made it challenging for the researchers to dedicate more time. As TAL is a continuous journey, this article has not included all of our reflections and emerging themes. Additionally, this inquiry is academic-dominated. The student’s voice has not been included in this project. Regardless of these limitations, we consider that there is space in the conversation about online learning to hear the subjective voice of the academics regarding this topic.

Recommendations for further research

At this point, the building of educational programs based on this model and reporting on their success and the new insights we get from any difficulties encountered is the first way forward. If, as Canning (Citation2010) and Blashke (Citation2012) have suggested, there’s a developmental process for students through engagement, and cultivation to realization stages, and if the educator’s role similarly shifts, from building confidence to supporting shared meaning and understanding and finally facilitating a desire to investigate one’s learning, then trialing and reporting on the various patterns using the models can generate a rich set of teaching resources and strategies to share among educators. The resultant reports can indicate what level of student the pattern(s) will best support.

Models are only useful if applied and if they work. The next step is to systematically test and trial this model with interested educators. Within these trials we may also consider and investigate:

the benefits provided by single, double, and triple-loop learning applied in diverse educational environments;

whether transformational learning occurs and informs new beliefs, actions policies, and principles of the professions; and

a component to gauge the student experience of the education programs that apply the model.

Conclusion

Scholars like Wood (Citation2017a, Citation2017b) have long argued the need for models of TAL that comprehend the multi-dimensionality and dynamism of the current TAL environment. In response to this need, this article addressed the research question: Based on our experience as educators, what methods of learning and which teaching strategies can support social work and human services curriculum delivery in an online environment?

To answer this question, we have briefly summarized the evolving learning-teaching practices and stated the research method employed for the analysis. Drawing from our analysis and reflections, we presented an egg and basket model. This multidimensional, culturally responsive model to social work and human services education shows how pedagogy, andragogy, heutagogy and paragogy can be integrated. The eggs and basket model can support online TAL, by encouraging reflection on societal context, present and future practice, organizational contexts, collaborative growth and personal growth. This model encourages all learning to be based on affective foundations, specifically values, attitudes and philosophies that promote single, double and triple-loop learning. It has implications for teaching-learning methods/philosophies of practice-based professions including social work.

We also discussed and shared examples of TAL strategies that are consistent with the ‘eggs and basket’ model and which we have observed as upholding quality online social work and human service education. These strategies included both guided and informal innovations, where technology was utilized to promote positive learning experiences, specifically single, double and triple loop learning. For us, the strength of these strategies was that they can provide students with autonomy over their learning and online environments. These strategies can also help create respectful and culturally aware spaces where the students’ voices are not only heard but are part of the development and delivery of the learning experience.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Charles Sturt University social work students and colleagues, who enthusiastically participated in online intensives during the COVID Pandemic and helped us generate these ideas for our mutual learning and teaching.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Earlier versions of this article were presented at two conferences: 2020 Virtual ANZSWWER (Australian and New Zealand Social Work and Welfare Education and Research), symposium and NFEN Workshop on ‘Social work in a Climate of Change’, 18–20 November 2020, organised by ANZSWWER and the University of Sydney; and the 8th Indian Social Work Congress (ISWC) & 8th International Consortium for Social Development Asia Pacific (ICSD AP) branch Conference 2020, titled ‘Social cohesion, collective responsibility and social work profession’, 28 February to 2 March 2021, jointly organised online by the National Association of Professional Social Workers in India (NAPSWI), ICSD AP and Department of Social Work (DSW), Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

References

- Agonács, N., & Matos, J. F. (2019). Heutagogy and self-determined learning: A review of the published literature on the application and implementation of the theory. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 34(3), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270433

- Atkas, C. (2021). Enhancing social justice and socially just pedagogy in higher education through participatory action research. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1966619

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2014). Supervision standards. Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/6027

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020). Code of ethics. Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/1201

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2021). Australian social work education and accreditation standards. North Melbourne. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/13629

- Bassendowski, S. (2016). Paragogy: Emerging theory. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 11(4). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=5024

- Blaschke, L. M. (2021). The dynamic mix of heutagogy and technology: Preparing learners for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1629–1645. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13105

- Blaschke, L. M., & Hase, S. (2015). Heutagogy, technology, and lifelong learning for professional and part-time learners. In A. Dailey-Hebert & K. S. Dennis (Eds.), Transformative perspectives and processes in higher education (pp. 75–94). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09247-8_5

- Blashke, L. M. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1076

- Blumberg, P., & Weimer, M. (2009). Developing learner-centered teaching: A practical guide for faculty. Jossey-Bass.

- Boud, D. J., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In D. J. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 18–40). Kogan Page.

- Brieger, E., Arghode, V., & McLean, G. (2020). Connecting theory and practice: Reviewing six learning theories to inform online instruction. European Journal of Training & Development, 44(4/5), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-07-2019-0116

- Brookfield, S. (1987). Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative. Jossey-Bass.

- Canning, N. (2010). Playing with heutagogy: Exploring strategies to empower mature learners in higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770903477102

- Chan, S. (2010). Application of andragogy in multi-disciplined teaching and learning. Journal of Adult Education, 39(2), 25–35. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ930244.pdf

- Charles Sturt University. (2022). HCS200 social work theory and practice 1.

- Cooperrider, D., & Whitney, D. (2007). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change. In P. Holman, T. Devane, & S. Cady (Eds.), The change handbook (pp. 73–88). Berrett-Koehler.

- Council on Social Work Education. (2008). Educational policy and accreditation standards. http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=13780

- Delgado, W. (2016). Analysis of Knowles andragogical principles, curriculum structure, and adult English as a second language standards: Curriculum implications. Universidad de Puerto Rico.

- Eberle, J., & Childress, M. (2009). Using heutagogy to address the needs of online learners. In P. Rogers, G. A. Berg, J. V. Boettecher, & L. Justice (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance learning (2nd ed., pp. 2239–2245). Idea Group Inc.

- Elizondo-Garcia, J., & Gallardo, K. (2020). Peer feedback in learner-learner interaction practices. Mixed methods study on an xMOOC. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 18(2), 122–135. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJEL.20.18.2.002

- French, A., & O’Leary, M. (2017). Teaching excellence in higher education: Challenges, changes and the teaching excellence framework. Emerald Publishing.

- Garnett, F., & Ecclesfield, N. (2015). The emergent learning model: Using the informal processes of learning to address the digital agenda for Europe. Conference Proceedings of eLearning and Software for Education (eLSE), 11(3), 116–121.

- Goldingay, S., & Land, C. (2014). Emotion: The “E” in engagement in online distance education in social work. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 18(1), 58–72. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/226

- Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2001). Moving from andragogy to heutagogy: Implications for VET. In Proceedings of research to reality: Putting VET research to work: Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association (AVETRA). https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991012820997202368/61SCU_INST

- Heron, J., & Reason, P. (1997). A participatory inquiry paradigm. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), 274–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049700300302

- Heron, J., & Reason, P. (2008). Extending epistemology within a co-operative inquiry. http://www.human-inquiry.com/EECI.htm

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2020). Global standards of social work education and training. https://www.ifsw.org/global-standards-for-social-work-education-and-training/

- Karoudis, K., & Magoulas, G. (2016). Ubiquitous learning architecture to enable learning path design across the cumulative learning continuum. Informatics (Basel), 3(4), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics3040019

- Khoo, B. K. S. (2019). Mobile applications in higher education: Implications for teaching and learning. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 15(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.2019010107

- Knowles, M. (1984a). The adult learner: A neglected species (3rd ed.). Gulf Publishing.

- Knowles, M. (1984b). Andragogy in action. Jossey-Bass.

- Knowles, M. S., Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F., III. (2012). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (7th ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lee, Y., & Rofe, J. S. (2016). Paragogy and flipped assessment: Experience of designing and running a MOOC on research methods. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 31(2), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2016.1188690

- Lindeman, E. C. (1926). The meaning of adult education. New Republic.

- Manojan, K. P. (2019). Capturing the Gramscian Project in Critical Pedagogy: Towards a Philosophy of Praxis in Education. Review of Development and Change, 24(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972266119831133

- Meszaros, A., & Baroti, E. (2016). The humanistic approach of adult and tertiary education. Acta Technica Jaurinensis, 9(2), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.14513/actatechjaur.v9.n2.395

- Mews, J. (2020). Leading through andragogy. College and University, 95(1), 65–68.

- Monk, N., McDonald, S., Pasfield-Neofitou, S., & Lindgren, M. (2015). Portal pedagogy: From interdisciplinarity and internationalization to transdisciplinarity and transnationalization. London Review of Education, 13(3), 62–78. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.13.3.10

- Moore, R. L. (2020). Developing lifelong learning with heutagogy: Contexts, critiques, and challenges. Distance Education, 41(3), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1766949

- Mulholland, N. (2019). Re-imagining the art school: Paragogy and artistic learning. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Najib, A. I. (2013). Pedagogy redefined: Frameworks of learning approaches prevalent in the current digital information. Journal of Educational Technology, 10(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.26634/jet.10.1.2302

- Osburn, L., Short, M., Gersbach, K., Velander, F., Mungai, N., Moorhead, B., Mlcek, S., Dobud, W., Duncombe, R., Kalache, L., Gerstenberg, L., Lomas, G., Wulff, E., Ninnis, J., Morison, A., Falciani, K., & Pawar, M. (2021). Teaching social work skills-based learning online during and post COVID-19. Social Work Education, 42(7), 1090–1109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.2013795

- Ospina, S., El Hadidy, W., & Hofmann-Pinilla, A. (2008). Co-operative inquiry for learning and connectedness. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 5(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767330802185673

- Pascoe, E., Short, M., Whitaker, L., Morris, B., Petrakis, M., Russ, E., Gersbach, K., Evans, S., Rose, J., Fitzroy, R., Reimer, L., Halton, C., Walters, C., & Berger, L. (2023). International network of Co-operative inquirers: Vision document. https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/international-network-of-co-operative-inquirers-vision-document

- Pawar, M. (2016). Reflective learning and teaching in social work field education in international contexts. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw136

- Pawar, M., & Anscombe, A. W. ( Bill) (2022). Enlightening professional supervision in social work: Voices and virtues of social workers. Springer.

- Pawar, M., Mlcek, S., Short, M., & Osburn, L. (2021). Combining pedagogy, andragogy and heutagogy to deliver transformational education [Paper presentation]. The 8th ISWC & 8th ICSD-AP Conference 2020, titled: Social cohesion, collective responsibility and social work profession, 28 February to 2 March 2021. Jointly organised online by the NAPSWI, ICSDAP & DSW, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India. https://napswi.org/cong/doc/8th_ISWC_Programme_Schedule_2020-Day_2.pdf

- Pawar, M., Sheridan, R., & Georgina, H. (2004). International social work practicum in India. Australian Social Work, 57(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0748.2004.00150.x

- Perry, S. A. (2023). Experiencing collaborative inquiry online: A literature review. Journal of Transformative Education, 21(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/15413446221149194

- Poitras Pratt, Y., Dustin, L., Hanson, A., & Ottman, J. (2018). Indigenous education and decolonization. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.240

- Raw, L. (2016). Adaptive pedagogies and paragogies. Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy, 26(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1353/tnf.2016.0015

- Reason, P., & Heron, J. (1995). Co-operative inquiry. https://wagner.nyu.edu/files/leadership/avina_heron_reason1.pdf

- Reason, P., & Heron, J. (2013). A short guide to co-operative inquiry. www.human-inquiry.com/cishortg.htm

- Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Sengupta, N., & Sengupta, M. (2018). Benefits of peer learning: A study among the post-graduate management students. International Journal of Knowledge Management and Practices, 6(2), 13–20.

- Short, M. (2018). The co-operative inquiry research method: A personal story. In M. Pawar, W. Bowles, & K. Bell (Eds.), Social work: Innovations and insights (pp. 232–244). Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Short, M., & Healy, J. (2017). Writing ‘with’ not ‘about’: Examples in Co-operative Inquiry. In S. Gair & A. V. Luyun (Eds.), Sharing qualitative research: Showing lived experience and community narratives (pp. 188–203). Routledge.

- Snowden, M., Halsall, J. P., & Huang, Y. X. H. (2016). Self-determined approach to learning: A social science perspective. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1247608. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1247608

- Strauss, S., Calero, C., & Sigman, M. (2014). Teaching, naturally. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 3(2), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2014.05.001

- Testa, D., & Egan, R. (2014). Finding voice: The higher education experiences of students from diverse backgrounds. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.860102

- Tosey, P., Visser, M., & Saunders, M. (2012). The origins and conceptualizations of ‘triple-loop’ learning: A critical review. Management Learning, 4(3(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611426239

- Tough, A. (1971). The adult’s learning projects: A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning. http://ieti.org/tough/books/alp.htm

- UNESCO IBE. (2021). Inclusion in education ( Thematic Notes No. 1, Curriculum on the Move). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378427

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- United Nations & Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2023). Goals 4 ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

- Wood, P. (2017a). From teaching excellence to emergent pedagogies: A complex process alternative to understanding the role of teaching in higher education. In A. French & M. O’Leary (Eds.), Teaching excellence in higher education: Challenges, changes and the teaching excellence framework (pp. 39–74). Emerald Publishing.

- Wood, P. (2017b). Holiploigy –Navigating the complexity of teaching in higher education. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 11(11). https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/421/pdf

- Zha, S., Estes, M. D., & Xu, L. (2019). A meta-analysis on the effect of duration, task, and training in peer-led learning. Journal of Peer Learning, 12, 5–28. https://eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ1219651