ABSTRACT

Focusing on the integration of human rights into the Ethiopian Bachelor of Social Work programme, this paper presents a study of students’ understanding of human rights by employing a mixed-methods research design. Qualitative content analysis and survey study were utilized to assess the extent of human rights infusion into the undergraduate curriculum and examine students’ understanding of human rights conventions. The qualitative content analysis revealed a non-explicit infusion of human rights content into the social work curriculum. Human rights were indirectly applied and referenced in the human rights themes, e.g. for refugees and migrants, showing a lack of explicit and direct integration of human rights in the curriculum. The survey study also showed that, of the 201 participants, a significant majority (77%) lacked awareness of the human rights documents pertinent to social work. A discernible augmentation in the familiarity with the human rights conventions was observed among students as they progressed through higher levels of study. Hence, the study posits that Ethiopian social work schools should consider revisiting their curricula and give due attention to the human rights infusion into their social work programmes.

Introduction

Human rights have long been a focus of the social work profession (Healy, Citation2008; Ife, Citation2001; Reichert, Citation2011; Staub-Bernasconi, Citation2016). This derives from the profession’s value and practice-based orientation (Hawkins, Citation2009), in which its mission and values are strongly compatible with human rights (Healy, Citation2008). As a result, social work theory and practice are essentially based on the values of human rights (Wronka, Citation2012). Therefore, the social work profession prioritizes human rights (Steen & Mathiesen, Citation2005; Steen et al., Citation2016). Prioritising human rights in social work education could equip students to frame their practice from a human rights perspective (Tibbitts, Citation2015). It is for these reasons that international professional social work organizations initiated human rights infusion into social work education (Gatenio Gabel & Mapp, Citation2020; Steen & Mann, Citation2015). For example, according to the current Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training, schools of social work should always aspire to develop curricula that are based on human rights principles and the pursuit of justice (International Association of Schools of Social Work [IASSW] & International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW], Citation2020, p. 11). Furthermore, international organizations (e.g. United Nations Centre for Human Rights [UNCHR], Citation1994; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], Citation2017) have also produced documents emphasizing the need to educate social workers about human rights.

As shown above, the integration of human rights into social work education was required by professional and international organizations. However, cross-cultural and substantial studies demonstrating the required incorporation of human rights have yet to be conducted (Steen & Mathiesen, Citation2005). The literature review shows that most studies (e.g. Healy, Citation2008; Ife, Citation2012; McPherson & Cheatham, Citation2015; Reichert, Citation2011; Staub-Bernasconi, Citation2010, Citation2016; Steen & Mann, Citation2015; Stellmacher & Sommer, Citation2008; Witt, Citation2020) were conducted in the Global North. To the researchers’ knowledge, very few studies (Amadasun, Citation2020; Carrim & Keet, Citation2005; Giliomee, Citation2023; Giliomee & Lombard, Citation2020; Lombard & Twikirize, Citation2016) are available on the topic in African countries. They show variable efforts made by social work programmes to integrate human rights into their curricula. However, these studies are geographically limited and do not clearly show students’ understanding of human rights and commitment to rights-centered practice.

In the Ethiopian context, none of the available studies related to social work (e.g. Butterfield, Citation2007; Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021; Kebede, Citation2019) discussed human rights issues and integration of human rights into social work education. This article is based on a study focused on exploring the extent of human rights integration into the Ethiopian Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) curriculum and impact on students’ understanding of human rights conventions. Thematically, the study explores the nature and extent of human rights integration in Ethiopian social work education through analyzing the harmonized BSW curriculum. The article addresses the following research questions: 1) how and to what extent were human rights infused into the harmonized BSW curriculum in Ethiopia? and 2) Do social work students have knowledge of human rights conventions? Geographically, it has been delimited to focus only on six schools of social work in Ethiopia. In the subsequent sections, the study provides a brief background on human rights in social work education, approaches to infusing human rights into social work curricula, and social work education in Ethiopia. It also discusses the results obtained through qualitative content analysis and survey study. Finally, the study provides discussions and suggestions that support the social work schools’ efforts in affording students access to human rights.

Human rights in social work education

The historical and philosophical connection between social work and human rights values is well recognized. Social work has a long history of being a human rights profession. Scholars assert its proud legacy of advocating for disadvantaged groups whose rights (e.g. healthcare, education, housing, and equality) have been violated. Pioneer social workers (e.g. Jane Addams, Eglantyne Webb, Alice Salomon & Charlotte Makgomo) had made great contributions to human rights and social justice causes before the establishment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (Healy, Citation2008; Staub-Bernasconi, Citation2016). Beyond the early social work reforms, the social work profession in itself has been officially involved in major human rights movements, for instance, during the Apartheid regime in South Africa and the US Civil Rights Movement (Healy, Citation2008). This and other historical contributions of the profession to the international human rights field confirm its intrinsic inclination toward being a human rights profession.

Moreover, apart from the social work profession’s historical orientation to the advocacy of human rights, social work and human rights philosophy are intertwined with each other (Steen et al., Citation2016). As a result, the profession continues to place a high focus on human rights. Human rights are, therefore, fundamental to social work since it is a particularly value-based profession in addition to its practice-based orientation (Hawkins, Citation2009). Similarly, Healy’s (Citation2008) findings also showed the mission and values of the social work profession to be strongly compatible with human rights. In recent times, this linkage has been unambiguously identifiable in major social work documents, organizations, and in associations’ conceptualization of the social work profession.

Despite the profession’s historical engagement with human rights, significant attention was not afforded to this field until the 1970s (Healy, Citation2008). Since then, international organizations and associations have articulated the centrality of human rights to the social work profession. The International Federation of Social Workers' initial policy statement (International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW], Citation1988) proclaimed the social welfare profession’s inclusion of inherent human rights values (Healy, Citation2008). Then, in their global definition of social work, IFSW and the International Association of Schools of Social Work (International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW] & International Association of Schools of Social Work [IASSW], Citation2001) heralded the profession’s commitment to human rights. Finally, in the later global definitions of social work, human rights became central to the profession, acknowledging that the profession is based on the concepts of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility, and respect for diversities (International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW] and International Association of Schools of Social Work [IASSW], Citation2014).

As discussed above, international professional social work organizations, e.g. IFSW and IASSW, initiated the advancement of human rights by including human rights education and related training in social work education. The United Nations Centre for Human Rights (UNCHR, Citation1994) has also prepared a document, Human Rights and Social Work: A Manual for Schools of Social Work and the Social Work Profession, which laid an essential basis for incorporating human rights education into social work curricula. In this document, the Centre stated that human rights are integral to social work as a value-based and practice-oriented profession and highlighted that ‘social work from its conception has been a human rights profession’ (UNCHR, Citation1994, p. 5). Recently UNESCO (Citation2017), in the third phase of its World Programme for Human Rights Education, also emphasized the need for educating social work educators and practitioners about human rights. Finally, the above-mentioned Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training (IASSW & IFSW, Citation2020) also emphasize the importance of human rights education for all social work study programmes.

Recognising the profession’s base in human rights and inclusion of human rights education into social work programmes is necessary to advance this inherent linkage (Steen et al., Citation2016). Incorporating human rights into social work institutions and organizations enables social workers to acquire knowledge and practice related to human rights (Henry, Citation2015). Moreover, the profession’s emphasis on human rights also lets social workers understand the relevance of human rights in their professional careers (Reichert, Citation2011). Educating social work students about human rights enables them to understand the profession better and guide their practice from a human rights perspective (Tibbitts, Citation2015). In addition, when students know about human rights, their commitment to the promotion and advocacy of human rights will be visible (Henry, Citation2015).

Integration of human rights content into social work curriculum

As discussed above, social work education and practice becomes more rights-centered when it includes human rights knowledge and frameworks in the curriculum. This requires certain ways of incorporating human rights into social work education (Henry, Citation2015). Integrating human rights principles and values into the social work curriculum can be accomplished through the use of the infusion approach (Lucas, Citation2013). Carrim and Keet (Citation2005) elaborated on this approach, arguing that it better describes the integration of human rights content into the curriculum. They argue that designing a curriculum through infusion brings symbiosis to different contents in the curriculum and easily pierces existing boundaries among disciplines.

The process of integration could range from ‘minimum infusion’ to ‘maximum infusion’ (Carrim & Keet, Citation2005). Minimum infusion is when the curriculum lacks a holistic or explicit inclusion of human rights content in its programme, indicating that it is concentrated on implicit inference of and reference and application to human rights knowledge in a non-universally inclusive manner (Carrim & Keet, Citation2005). On the other hand, human rights would be assumed to be infused at the maximum level when human rights developments, knowledge, skills, and values are comprehensively covered in the curriculum. Students also need to have direct access to human rights in their courses, including the relevant political and legal content that was formerly taught as civic education (Carrim & Keet, Citation2005). These typologies can help with understanding the integration of human rights in the social work curriculum and provide a basic framework for identifying how far they have been included. Nevertheless, it must be underlined that curriculum design is a dynamic and fluid process (Ife, Citation2012). It should be noted that integrating human rights content, among other things, requires the social work faculty’s ongoing knowledge of and orientation toward human rights.

In the African context, the accustomed culture of human rights education in schools is a recent development that is present only in some countries. Even in the African states with experience in human rights education, e.g. South Africa, student access to human rights knowledge is limited to a basic level, demanding a maximum infusion of human rights into the curriculum (Carrim & Keet, Citation2005). Lombard and Twikirize (Citation2016) have also noted that human rights integration into the curriculum is negligible and not uniform. In a recent study, Giliomee and Lombard (Citation2020) pointed out that the social work curriculum’s scope in Africa is restricted to exposing students to information about basic human rights declarations such as the UDHR, the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, and treaties concerning children, women, people living with disabilities, and other vulnerable groups. According to these authors, social work programmes are too constrained to integrate fundamental philosophical ideas and human rights core values in their curricula beyond teaching students about international human rights treaties.

Social work education in Ethiopia

Social work is a relatively young profession in Africa, and for a long time, social work education and practice were strongly reliant on Western models (Giliomee & Lombard, Citation2020). As was the case for many African countries, Ethiopia’s social work education and training developed in the second half of the twentieth century. Kebede (Citation2019) classifies the emergence and development of social work education in Ethiopia into two phases: the pre-2004 and post-2004 periods. The first phase started in 1959 with a two-year diploma course until it was upgraded to the degree level in 1967 (Kebede, Citation2019). The program was part of the Ministry of Public Health and the UNICEF project until it became part of the then University College of Addis Ababa in 1961. Since then, social work education and training have been offered by the School of Social Work at Addis Ababa University until it was closed by the socialist regime in 1974 (Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021; Kebede, Citation2019).

In the second phase, the programme was relaunched in 2004 and developed subsequently, with a significant influence from international scholarship. During the programme’s relaunch, international expertise has played a valuable role in curriculum design, teaching, and advising students, demonstrating the profession’s internationalism (Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021). In addition, the social work programme was mainly reinstituted to address the nation’s health and social needs by concentrating on poverty reduction (Butterfield, Citation2007). After the demise of the socialist regime, pro-social work provisions were outlined (Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021; Kebede, Citation2019). Consequently, in partnership with the Jane Addams College of Social Work of the University of Illinois, Addis Ababa University launched a graduate program in social work in 2004 (Butterfield, Citation2007; Kebede, Citation2011). During this time, the school has considered international social work education guidelines, i.e. Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training (IASSW & IFSW, Citation2004), as well as the country’s context and needs (Butterfield, Citation2007; Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021).

The authors noted the influence of American professors and funding organizations (i.e. international humanitarian organizations) in shaping the social work curriculum to reflect Western contexts and standards. The guidance offered by international organizations and professors provided invaluable insights into contemporary social work theories, methodologies, and practices, facilitating the alignment of the curriculum with international standards and trends. However, the need for greater integration of local knowledge and practices has become increasingly necessary. Local knowledge and practices that prioritize community-based approaches, collective well-being, and informal support networks have not been carefully considered. Hence, there have been apparent tensions between Western-centric approaches and the indigenous knowledge and practices inherent in Ethiopian culture. Partly the scarcity of local expertise has made it challenging to establish professional dialogue that respects and incorporates local knowledge and culturally sensitive practices. Eventually, emerging local lecturers and professors have continued to use the existing curriculum in newer social work schools (Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021). In this manner, the harmonized BSW curriculum has been applied in social work schools of Ethiopian public universities, allowing a uniform application of its course objectives and structures.

In general, the historical trends of Ethiopian social work education show its gradual movement from prioritizing local contexts to considering international demands and standards in its programmes. Within such developments, coverage of human rights education in the BSW curricula could be expected, though it remained unknown. The available literature for the social work profession in Ethiopia (e.g. Butterfield, Citation2007; Hagos Baynesagn et al., Citation2021; Kebede, Citation2019) could have shown adequate coverage of human rights. As a result, the extent to which human rights are integrated into the BSW programmes and how well students understand human rights conventions remains to be discovered. Thus, it is difficult to examine how far the programme conforms with international social work standards and to know the extent of students’ readiness to be responsive to human rights violations.

Method

Based on these identified gaps, this study aimed to address the following research questions: 1) How and to what extent were human rights infused into the harmonized BSW curriculum in Ethiopia? and 2) Do social work students have knowledge of human rights conventions? The study aimed to explore the integration of human rights content within Ethiopian social work curricula, addressing a gap in the existing knowledge on this topic. As Creswell (Citation2009) suggests, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected to achieve the study’s objectives through data triangulation. Distinct data-gathering techniques were employed for the collection of qualitative and quantitative data.

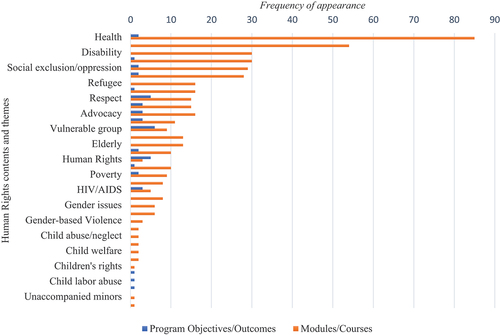

Accordingly, the first research question was addressed through qualitative document analysis. As Strydom and Delport (Citation2011) suggest, the study used document analysis to understand the essential contents of the raised question. For this purpose, the study used the document analysis checklist as a framework to assess human rights infusion in the harmonized social work curricula. The document analysis checklist includes but is not limited to, the themes and contents depicted in . They are constructed to reflect fundamental human rights values and principles, the rights of disadvantaged groups (e.g. women, children, elderly, refugees and migrants), and health and development-related rights. These themes and contents were drawn from the literature, mainly from the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training (IASSW & IFSW, Citation2020) and from the document; Human Rights and Social Work: A Manual for Schools of Social Work and the Social Work Profession (UNCHR, Citation1994). Hence, the qualitative data was obtained by checking the appearance of these and related human rights themes in the curricula. Additionally, the structure and distribution of courses concerning human rights in social work curricula, including the incorporation of dedicated or ad-hoc human rights courses in the social work curricula, were explored.

The study addressed the second research question using a cross-sectional survey design from a sample of 201 students enrolled in BSW and Master of Social Work (MSW) programmes at six public universities in Ethiopia. The target population for this study was 450 students attending studies in 2022/23 in social work schools in universities located in Northern, South West, Eastern, and Central Ethiopia. In total, 212 out of 450 students participated in the study. The survey study used a proportionately stratified random sampling technique to represent the study population accurately (Creswell, Citation2009).

The self-reported questionnaire addressed research questions that sought to examine students’ understanding of human rights conventions. As Kumar (Citation2011) pointed out, a questionnaire is appropriate for a survey with a scattered and literate study population and with greater anonymity. The questionnaires included open-ended and closed-ended items that addressed participants’ background profiles and their knowledge of human rights. The questions were constructed to examine social work students’ knowledge of relevant human rights legislation. It is based on the premise that human rights-centered social work curricula could equip students to learn about human rights. Hence, two questions, which mainly focused on knowledge and sources of human rights, were designed to corroborate with the qualitative content analysis checklist and to enable the study to explore the impact of [integrating] human rights content into the social work curricula. Participants were asked to mention human rights conventions/declarations that they might know. If they could mention any of the human rights conventions/declarations, they were also asked to respond whether their knowledge rely on any of the following sources, i.e. classroom teachings, social media, workshops/seminars, colleagues/friends, or any other sources.

Data analysis

The study concurrently analyzed qualitative and quantitative data utilizing distinct approaches and cross-checked the results to identify corroborating points. For the qualitative data, a summative approach to qualitative content analysis was employed to assess the inclusion of human rights content in the social work curricula. Summative content analysis allows data analysis with a manual or computer search for the identified words or contents (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Hence, the researchers manually looked for the appearance of human rights content or related themes, specified in , in the BSW curriculum using the PDF search facility.

To this end, the curriculum was divided into two broader portions: The program objectives/outcomes section and the Modules/Courses section to locate the distribution of human rights contents. Accordingly, human rights themes and contents, including those depicted in , were checked whether and how many times they appeared in the social work curricula. The appearance of each theme and content was counted and presented numerically. For instance, Health and Disability were the terms that appeared most frequently in the curriculum, specifically in the Modules/Courses section as illustrated in . As Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005) suggest, this approach enabled the researchers to identify and quantify human rights contents or related themes in the curricula. The analysis also included an explanation of the context of how human rights themes and contents manifested in the curricula. For example, the term human rights is emphasized in the curricula within the context of development and social and collective well-being.

Procedurally, themes and sub-themes were developed after identifying the appearance and frequency of human rights contents or themes and exploring the structured [inclusion] of human rights courses in the BSW curriculum. As depicted in , the results of this section were summarized into two main themes: 1) Dedicated or related course on human rights and 2) Integration of human rights themes in the social work curriculum. The first theme focused on explaining whether structured inclusion of a dedicated or related course on human rights existed in the curricula. The second theme focused on discussing the extent of human rights infusion in the curriculum. The latter section of the paper discussed the themes by further grouping into four sub-themes, i.e. human rights principles and values, vulnerable groups and human rights, and development themes and health rights.

Table 1. Summary of themes and Sub-themes from the document analysis and survey study.

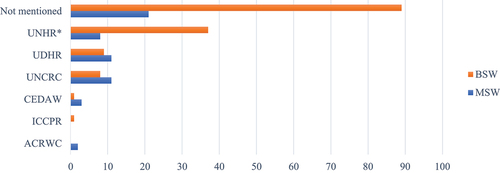

For the quantitative data, the researcher used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 27) to analyze the data collected through a self-administered questionnaire because of its usefulness for word processing, statistical computation, and graphic presentation (Kumar, Citation2011). For this purpose, 201 self-administered surveys were used out of the 212 surveys initially distributed to the respondents. The researchers identified 11 cases with missing and incomplete data and removed them during the data encoding and cleaning phase. As depicted in , the encoded and cleaned data were analyzed and reported under the central theme of understanding human rights conventions and the sub-theme of sources of knowledge of human rights conventions. In both cases, the results were analyzed using frequencies and percentages, as illustrated in . Procedurally, the number of participants who responded to the questionnaire item ‘Please mention human rights conventions or declarations you might know’ were counted and the name of the identified human rights conventions, declarations, and particular set of human rights were calculated. Then the analysis was conducted across study levels, i.e. BSW and MSW, and the findings were presented accordingly.

Based on the analysis, the results of the response were grouped into three categories:

Those who knew human rights convention/s (i.e. depicting how many of them, in each study level, knew certain human rights conventions);

Those who mentioned particular right/s but not convention/s, and this is represented in ‘UNHR*’; and

Those who did not know any of the human rights conventions or a particular set of rights.

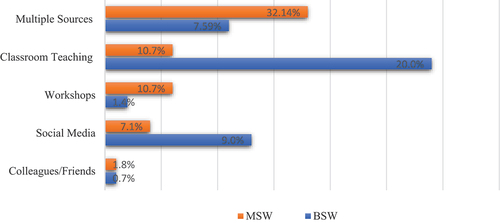

Similarly, participants’ responses to the questionnaire item ‘Please identify sources of knowledge for the human rights conventions or declarations you might know’ were analyzed and depicted in . The analysis was based on the response figures grouped into 1 and 2 categories, as discussed above. In other words, the response of the participants who mentioned knowledge of any of the human rights conventions or a particular set of rights was used in the analysis. Accordingly, out of the 201 responses, 91 were considered for the analysis, and the results were grouped under multiple sources, classroom teachings, workshops, social media, and colleagues or friends, and presented in .

Ethical considerations

The study maintained the required ethical considerations that include but are not limited to obtaining permission from schools to conduct the study and informed consent from the participants. The study’s purpose was explained to the social work schools’ heads and study participants. On this basis the social work schools’ heads granted permission to use the curriculum for content analysis and collect surveys from the social work students. Students also participated on a completely voluntary basis (Babbie, Citation2016). The participants were informed in the consent form that they could quit participating in the study at any time without providing any reasons. Regarding anonymity and confidentiality (Babbie, Citation2016), the study designed a questionnaire that does not reveal students’ identity and university affiliation. Students filled out the questionnaires anonymously, and university names were coded, with only the regions where they are located being described. The study, therefore, has no implications of harm to its participants.

Results

The study aimed to assess the extent of human rights infusion in the BSW curriculum and to examine students’ knowledge of human rights conventions. The study addressed the first research question by analyzing the appearance and frequency of human rights contents or themes, and examining the structured inclusion of human rights courses in the BSW curriculum. As depicted in , the results of this section were summarized into two main themes: 1) Dedicated or related course on human rights and 2) Integration of human rights themes in the social work curriculum. While the first theme focused on explaining whether structured inclusion of a dedicated or related course on human rights existed in the curricula, the second theme focused on discussing the extent of human rights themes in the curriculum. The latter section of the paper discussed the themes by further grouping into three sub-themes, i.e. human rights principles and values, vulnerable groups and human rights, and development themes and health rights. Furthermore, consists a theme comprising of students’ knowledge and sources of human rights conventions obtained through the quantitative analysis.

Dedicated or related courses on human rights

The study examined whether the BSW programme course structure included dedicated course/s on human rights or considered the infusion of human rights contents into other courses. Assessment of the course lists in the harmonized BSW curriculum showed that the BSW programme is structured to offer 28 ‘major’ and four ‘supportive’ courses to social work students. It was noticeable that the list of courses in the curriculum included scarcely a dedicated course on human rights in BSW social work education. None of the courses offered as a major in the BSW programme was dedicated to human rights.

The document analysis showed positive results regarding courses related to human rights and the ad hoc infusion of human rights in a course or as part of a course unit/chapter. For instance, second-year students take a supportive ‘Introduction to Law’ course offered by the School of Law in their first semester. Teaching students about the law exposes them to human rights content and to protection mechanisms, as these are integral parts of the law. This supportive course introduces students to concepts including fundamentals of the law and legal process, the judicial system, major social legislations, social advocacy, legal aid, and legal assistance. In this manner, students’ exposure to these and other related concepts could help them gain knowledge of the legal system, enabling their understanding of human rights protection and enforcement mechanisms. Similarly, considered as part of a chapter or unit in a course, human rights related to specific segments of the population (for instance, refugees and migrants) were added to courses/modules. Primarily, a major course on ‘Migration, Refugees and Social Work Practice’ has incorporated rights related to refugees and migrants into a separate chapter/unit and its reading sections.

In general, the course structure and distribution of the BSW program show that visible representation of human rights as part of the major courses in social work was not considered. Nevertheless, as discussed above, incorporating human rights as part of related courses and ad-hoc infusion into the existing courses are noticeable.

Integration of human rights themes in the BSW programme

Distribution of human rights contents in the BSW curriculum

The study assessed the appearance and frequency of relevant human rights contents and themes in the BSW curriculum document. As tabulated in , these contents were incorporated, in different degrees, into the sections of the BSW curriculum (i.e. programme objectives, outcomes, module/course objectives/outcomes, and recommended readings and bibliography). These contents were grouped under human rights themes and sub-themes, namely human rights principles and values, vulnerable groups (e.g. gender issues, child rights, and the rights of refugees and migrants), development, and health rights.

Human rights principles and values

Human rights values and principles were one of the themes that appeared in the curriculum, both as human rights concepts in different courses and as a methodological strategy for course instruction. The content analysis results showed that the presence of these human rights contents varies greatly, from frequent appearance to exclusion.

The human rights principles and values, which were frequently mentioned in the curriculum included respect, equality, and participation. They appeared in different sections of the curriculum in a wide variety of manifestations. In most areas, respect featured in regard to relations between professors and students around respecting diversity. We find, for example, phrases like ‘respect students, regardless of their demographic backgrounds, learning styles, personalities, and abilities’ and ‘promote mutual respect among students’. Similarly, participation was emphasized in the curriculum and conveyed as one of the inclusive strategies for social and community development and teaching strategies. The excerpt, for example, that ‘The course at large depends on … student participation and independence’ could be an example of rights to participation and voice.

The appearance of the term human rights itself in the BSW curriculum was minimal, being mostly confined to a programme section and emphasized within the context of development and social and collective well-being. It was, for instance, stated in the curriculum document as ‘Formulate and implement policies and programmes that promote people’s well-being, development and human rights, and collective social harmony and social stability in Ethiopia’. The BSW curriculum adopted the global definition of social work, which acknowledges human rights as fundamental to the social work profession, stating that ‘principles of social justice and human rights are fundamental to social work’ (IASSW & IFSW Citation2004). The latest definition, from 2014, highlights human rights in the same way but has not yet been integrated into the curriculum.

In a nutshell, the adoption of the 2004 global definition of social work could show the programme’s commitment to considering human rights as essential to the social work profession. However, the minimal appearance and usage of the term human rights and its integral components could also show the programme’s limitation to incorporate essential human rights knowledge into social work education. For instance, some of the fundamental human rights values and principles, e.g. human dignity, universality, inalienability, and freedom, were not boldly prioritized. The inclusion of course or reference materials that could expose students to human rights principles and values were therefore inadequate.

Vulnerable groups and human rights

The study examined the social work programme’s composition and capacity to incorporate rights related to groups identified as ‘vulnerable’, including but not limited to women, children, refugees, and migrants. Working with and empowering disadvantaged, oppressed, and vulnerable groups was one of the programme’s focus areas, as stipulated in the standards of international social work organizations (i.e. IASSW & IFSW, Citation2004). Reichert (Citation2006) suggests that social work professionals should aim to advocate for vulnerable groups, which demands that social work programmes incorporate human rights in their education and training. Overall, the study reveals the emphasis given to vulnerable groups as the major areas of concern in the BSW programme. The programme aimed for students to obtain the basic understanding and competencies to equip them to work with children, women, refugees and migrants, and senior populations.

In the dimension of human rights, however, the study shows that the programme discusses vulnerable groups in fragmented tones and contexts. For example, while women’s rights explicitly appeared regarding protecting women seeking asylum and refugees, other aspects received much less emphasis. Further, the supportive reading materials were limited and exclusively inclined to address gender issues in the context of their health aspects. In brief, these could show the inclusion of specific human rights themes related to gender but could not provide a full picture of human rights around gender equality and women’s rights in the curriculum. Hence, the study underscores the essential need for students to have adequate access to knowledge on women’s rights, especially in light of defending against pervasive gender-based violence in Ethiopia.

Concerning children, the curriculum covered social work courses structured to offer students the requisite social work values and skills enabling them to work with children in families and school settings. The content analysis of the curriculum document, as shown in , reveals that coverage of the rights related to children was not explicitly mentioned. However, related to the rights of refugees and unaccompanied children, the programme gave special consideration to international human rights guidelines in its reading section, notably to the UNHCR’s Refugee Children Guidelines on Protection and Care (1994) and Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in Dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum (1997). The study shows that rights of children in special circumstances are well incorporated though not sufficiently introduced students to the general concepts and themes related to children’s rights.

It was visible that rights related to refugees and migrants were highly emphasized in the curriculum compared to other vulnerable groups. The curriculum document explicitly includes the human rights of people seeking international protection and special consideration during the due process. The programme has also incorporated reading materials related to social work practice with refugees and mechanisms of international protection, such as the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. As a result, students could become familiar with concepts of global citizenship and legal frameworks, and understand the actors protecting internally displaced people, refugees, stateless persons, and unaccompanied children. Thus, the extent of human rights integration in the curriculum is visible, which could enable students to know the rights of refugees and migrant populations. The programme’s emphasis on the rights of refugees and migrant populations can be viewed as viable and as a promising step, considering Ethiopia’s role in hosting a huge number of populations with refugee and migration backgrounds.

Coverage of development themes and health rights

Social work students need to understand the concepts related to development as they are interrelated and essential to fulfilling human rights. As shows, the study assessed whether and how frequently these themes and related concepts appeared in the BSW curriculum. The results indicate that development-related concepts and themes were robustly emphasized in the curriculum. These mainly include, but are not limited to, social exclusion/oppression, social welfare, social development, social justice, advocacy, poverty, and social policy. These development themes and concepts were covered under the following courses and course units: Social Development and Community Practice; Gender, Diversity, and Social Justice; Social Policy Analysis and Practice; and Social Work and Social Justice [Course Unit].

As Raniga and Zelnick (Citation2014) put it, students’ exposure to these and other development-related themes equips them to show a critical understanding of the factors that oppress, exclude, and disempower people globally. Hence, they can evaluate and link policy to the larger social welfare context and become change agents to advance social justice and human rights (Raniga & Zelnick, Citation2014). In general, the study shows that the curriculum covered essential themes for the development, but it did not emphasize sustainable development goals and environmental justice, which are critical in times of multiple ecological crises (Hawkins, Citation2010; Stamm, Citation2023).

Furthermore, the programme also stressed health as one of the social work practice areas and specializations. It has incorporated the relevant courses, such as Social Work in Healthcare and Psychiatric Social Work, aimed at training students in social work practice in healthcare settings and mental health institutions. The programme could also offer students the knowledge they need to understand the larger socioeconomic and political factors that impact health and well-being. Hence, implicitly, the BSW programme could expose social work students to the significance of human rights and fight discrimination against access to health services.

Survey participants’ understanding of human rights conventions

As discussed in the preceding sections, the study explored the extent of human rights infusion into the harmonized BSW curriculum through document analysis. Based on the survey results, this study section discusses students’ knowledge of human rights conventions and declarations. The survey study sought to examine social work students’ knowledge of international and regional human rights treaties. For this purpose, BSW and MSW students were asked whether they knew the human rights instruments relevant to social work and to mention them. Their response was analyzed and grouped into three categories:

Those who knew human rights convention/s;

Those who mentioned particular right/s, which are represented in ‘UNHR*’; and

Those who do not know any of the human rights conventions or a particular set of rights, which are referred as ‘Not mentioned’. The categorized responses are shown in and discussed in relation to the total participants and the levels of their study.

The first category discusses participants’ responses, which consist of at least one or more human rights conventions or declarations. Participants were asked to mention human rights conventions or declarations that they might know. Out of the 201 participants who were surveyed regarding their knowledge of human rights conventions, only 46 of them were able to identify the following conventions: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

As illustrated in , most participants, among those who indicated knowledge of human rights, reported familiarity with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Notably, the UDHR and UNCRC were the most frequently mentioned, with twenty (n = 20) and Nineteen (n = 19) participants recognizing them, respectively.

However, analysis of the responses across educational levels reveals a slight variation between BSW and MSW students. For example, nine (n = 9) BSW and eleven (n = 11) MSW students reported familiarity with the UDHR, while eight (n = 8) BSW and eleven (n = 11) MSW students indicated knowledge of the UNCRC. As illustrated in , students’ knowledge of human rights conventions or declarations also moderately varied across the levels of study on the other human rights instruments.

In the second category, participants’ responses comprising only specific rights, represented as UDHR* without demonstrating direct knowledge of any human rights conventions or declarations, were discussed. Among the total participants, forty-five (n = 45) of them mentioned only a phrase or a sentence about one or a couple of rights; that include but are not limited to the right to own property, freedom of religion, the right to life, freedom of movement, a right to work, equal treatment, and the right to education. This figure is almost equivalent to the 23% (n = 46) of participants who reported knowing human rights conventions or declarations.

As depicted in , when these figures were analyzed across study levels, a relatively larger (n = 37) number of BSW students mentioned only one or more of the rights mentioned above compared to the MSW participants (n = 8). Conversely, the study reveals that the number of MSW students who reported knowing human rights conventions is relatively higher than that of BSW students. The results suggest that with an increased level of study, social work students’ knowledge of human rights conventions or declarations becomes less fragmented.

The third group of responses consists of those categorized as Not mentioned. This category refers to participants’ responses who, when asked to name any human rights conventions or declarations they might know, did not mention any specific conventions, declarations, or sets of rights. This category encompasses the responses of the majority (n = 110) of the participants, accounting for more than half (54.7%) of the total responses. Among these figures, as illustrated in , a significantly higher number of ‘Not mentioned’ responses (n = 89) were reported by students enrolled in the BSW program compared to those in the MSW program (n = 21). These figures suggest that a substantial proportion of students, particularly at the undergraduate level, need to know about human rights treaties pertinent to the social work profession.

Sources of knowledge of human rights conventions

Participants were asked to identify sources of knowledge for the human rights conventions or declarations they might know. As discussed above, 45 students also listed a particular set of rights, although they could not name conventions or declarations. As a result, the researchers also used the sources indicated in those responses in the following discussions. Consequently, the total number of responses for all sources (i.e. 46 for human rights conventions/declarations and 45 for particular set of rights) became ninety-one (n = 91). In other words, the sources for the responses of fifty-six (n = 56) out of 145 BSW and thirty-five (n = 35) out of 56 MSW students were discussed.

The study showed that students gained knowledge of human rights legislation from various sources, including classroom teachings, social media, workshops/seminars, colleagues/friends, and multiple sources. Correspondingly, 38.5 and 31.8% of the total students gained knowledge of human rights legislation from their classroom teachings and multiple sources, respectively.

As depicted in , a relatively higher proportion (20%) of BSW students described classroom teachings as their source of human rights conventions than MSW students. On the other hand, a proportionally higher number (32.14%) of MSW students reported multiple sources as their primary means of knowing about human rights conventions.

Participants also mentioned that they knew about human rights agreements from other sources, mainly from social media and workshops/seminars. A relatively more significant number of BSW students than MSW students cited social media as their source of knowledge. However, the proportionate number of MSW students who garnered knowledge of human rights conventions through workshops was moderately greater than that of BSW students.

As discussed above, the study revealed that social work students accessed knowledge of human rights instruments in different ways, and the figures showed variation based on the student’s level of study. Most BSW students identified classroom teachings as primary sources for their knowledge of human rights conventions. In contrast, MSW students used multiple sources as their primary means of knowing about human rights conventions. Notably, the study also showed that students’ reliance on social media for garnering information about human rights conventions decreased as their level of study advanced; instead, there was a rise in their use of other sources of knowledge, such as workshops, classroom teachings, and combined sources.

Discussion

The study aimed to assess the extent of human rights integration into the BSW curriculum and examine its effect on students’ knowledge of human rights conventions. The document analysis reveals minimal coverage of human rights content in the social BSW programme. With reference to Carrim and Keet’s (Citation2005) framework, any maximal coverage of human rights knowledge, values, and skills in the BSW curriculum is much less likely. The human rights contents were found to be indirectly applied and referenced in certain major courses about vulnerable groups (e.g. refugees and migrants). According to Carrim and Keet (Citation2005), this indirect access to human rights knowledge could imply a lack of explicit and direct integration of human rights in social work education. In this regard, the current study showed results consistent with previous studies (e.g. Giliomee & Lombard, Citation2020; Lombard & Twikirize, Citation2016), which showed a limited scope and coverage of human rights in African social work programmes. Specifically, Giliomee and Lombard’s (Citation2020) study revealed that social work programmes are too constrained to integrate fundamental philosophical ideas and core values on human rights into their curricula.

Consequently, the limited incorporation of human rights into the social work programme could affect students’ knowledge and understanding of human rights conventions relevant to the social work profession. The survey study revealed that most students needed to learn the basic human rights treaties relevant to the social work profession. In other words, less than 25% of participants identified only some of the human rights treaties, e.g. UDHR, UNCRC, and CEDAW that Ethiopia has ratified. Partly, this could be attributed to the limited incorporation of human rights treaties in the curriculum. Previous studies have shown that limited knowledge of human rights conventions among social work students is not uncommon. Students in Guyana, for example, needed more knowledge of human rights conventions due to a lack of human rights infusion into the curriculum (Henry, Citation2015).

The survey study also revealed that students with higher levels of study were better at knowing human rights conventions, and they were not limited to knowing particular right/s specified in certain articles. Students’ tendency to have a better knowledge of human rights treaties after more years of study was also reported in Henry’s (Citation2015) study in Guyana. As shown in , the reports of students with advanced levels of study showed that they rely on different sources (e.g. workshops) for their human rights knowledge besides their classroom teachings.

However, the number of students who knew fundamental human rights conventions could have increased if there had been better human rights and related training for students. Theoretically this, in turn, could negatively affect students’ support for human rights principles and translate them into social work practice. As a result, it will be challenging for students to participate in meaningful discussions and eventually implement a rights-based practice because of their need for more adequate understanding of basic human rights documents (Giliomee, Citation2023).

Implications for social work education and practice

The findings suggest that social work schools should give due attention to human rights education in their programmes to fill the apparent gaps in this area. This could include a commitment to revisiting their programmes and prioritizing human rights infusion into their curricula. Including a dedicated course on human rights and the infusion of human rights and principles into major courses could be one of the considerations. In doing this, their programmes could increase their capacity to enable students’ access to human rights content and increase their familiarity with international and national human rights instruments. Students would, in this way, be prepared to recognize human rights violations and work to promote human rights and fight against social injustices (Gatenio Gabel & Mapp, Citation2020; Henry, Citation2015; Witt, Citation2020). Further, the direct infusion (Carrim & Keet, Citation2005) of human rights into the social work curriculum could enable students to view their profession as a human rights field (McPherson & Cheatham, Citation2015).

To facilitate students’ access to human rights knowledge, schools of social work could engage in interdisciplinary collaboration with professions and organizations that prioritize human rights. For example, the Ethiopian Social Workers Professional Association could be a valuable asset in filling the existing gaps, though collaborative work with it has yet to appear due to its recent establishment. Similarly, the Office of Social Work Field Education Coordination could organize periodic seminars and workshops on different human rights issues. Such experiences alongside classroom teachings have significant implications. At the very least, such efforts could equip students to understand human rights principles and approaches to dealing with human rights violations in their field education practicum. It could also create opportunities for students and social work educators to discuss experiences of handling human rights issues in different contexts and circumstances, including social work field education practice settings. As Giliomee (Citation2023) states, providing human rights training for social work educators is also essential to fostering a human rights culture in the profession.

Conclusion

The study shows that the integration of human rights within the BSW curriculum in Ethiopia is addressed implicitly, but it also reveals a notable inadequacy in the number of students with knowledge of human rights conventions. This underscores the imperative for a more comprehensive infusion of human rights materials into the programme, as the current exposure is insufficient for inculcating human rights values and principles in the students.

The incorporation of human rights into the social work programme is essential to furnish students with the requisite knowledge, empowering them to champion human rights and advocate for social justice. Collaboration between social work schools and diverse entities such as human rights organizations, professions, disciplines, and professional organizations is paramount to achieving this. Moreover, considering the fact that this theme still needs to be fully addressed, conducting further studies on the following areas would be beneficial to distinguish the best approaches to infuse human rights into the social work curriculum and equip students with the required knowledge and skills. Firstly, research that includes the voices of senior professors, preferably those who participated in the curriculum development, would help to understand the pedagogical aspects and contexts of human rights inclusion in the BSW programme. Secondly, further studies that focus on comparative analysis of BSW and MSW programmes concerning human rights content would be essential for programme evaluations and making the necessary adjustments. In conclusion, by prioritizing and integrating human rights into their BSW programmes, Social Work Schools can positively influence students’ comprehension and commitment to human rights in a broader context, including a nuanced understanding of human rights conventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amadasun, S. (2020). Applying a rights-based approach to social work practice in Africa: Students’ perspectives. International Journal of Social Sciences Perspectives, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.33094/7.2017.2020.71.1.9

- Babbie, E. (2016). The practice of social research (14th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Butterfield, A. K. J. (2007). The internationalization of doctoral social work education: Learning from a partnership in Ethiopia. Advances in Social Work. https://doi.org/10.18060/201

- Carrim, N., & Keet, A. (2005). Infusing human rights into the curriculum: The case of the South African revised national curriculum statement. Perspectives in Education, 23(2), 99–110.

- Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Gatenio Gabel, S., & Mapp, S. (2020). Teaching human rights and social justice in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656581

- Giliomee, C. (2023). A new path to cultivate human rights education at schools of social work in Africa from a decolonial lens. Social Work Education, 4(2), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2199770

- Giliomee, C., & Lombard, A. (2020). Human rights education in social work in Africa. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.25159/2415-5829/5582

- Hagos Baynesagn, A., Abye, T., Mulugeta, E., & Berhanu, Z. (2021). Strengthened by challenges: The path of the social work education in Ethiopia. Social Work Education, 40(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1858044

- Hawkins, C. A. (2009). Global citizenship: A model for teaching universal human rights in social work education. Critical Social Work, 10(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v10i1.5804

- Hawkins, C. A. (2010). Sustainability, human rights, and environmental justice: Critical connections for contemporary social work. Critical Social Work, 11(3), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v11i3.5833

- Healy, L. M. (2008). Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International Social Work, 51(6), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872808095247

- Henry, P. A. (2015). Analyzing the integration of human rights into social work education. Issues in Social Science, 3(2), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.5296/iss.v3i2.8041

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ife, J. (2001). Local and global practice: Relocating social work as a human rights profession in the new global order. European Journal of Social Work, 4(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/714052835

- Ife, J. (2012). Human rights and social work: Towards rights-based practice (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Workers. (2004). Global standards for the education and training of the social work profession. Adopted at the general assembly. Retrieved July25, 2024, from https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Global%20Standards%20for%20the%20Education%20and%20Training%20of%20Social%20Work%20Profession.pdf

- International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Workers. (2020). Global standards for social work education and training. International policy papers.

- International Federation of Social Workers. (1988). Human rights. International policy papers.

- International Federation of Social Workers and International Association of Schools of Social Work. (2001). International definition of social work. Retrieved July 25,2024, from https://www.ifsw.org/global-standards/

- International Federation of Social Workers and International Association of Schools of Social Work. (2014). Global definition of social work. Retrieved July 25, 2024, from https://www.ifsw.org/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Kebede. (2011). The challenges of Re-establishing social work education at addis ababa university: Personal reflection. Retrieved July 25, 2024, from https://africasocialwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/The-Challenges-of-establishing-social-work-education-Wassie-Kebede-Ethiopia.pdf

- Kebede, W. (2019). Social work education in Ethiopia: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Social Work, 6(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijsw.v6i1.14175

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Lombard, A., & Twikirize, J. (2016). Africa region. In Global agenda for social work and social development: Promoting the dignity and worth of Peoples, IASSW, ICSW, IFSW (2nd Report (pp. 35–60). IFSW. https://www.iassw-aiets.org/files/2016_Global-Agenda-2nd-Report-PDF-Edition-WEB.pdf

- Lucas, T. (2013). Social work in Africa: The imperative for social justice, human rights and peace. Botswana Journal of African Studies, 27(1), 87–106.

- McPherson, J., & Cheatham, L. P. (2015). One million bones: Measuring the effect of human rights participation in the social work classroom. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2015.977130

- Raniga, T., & Zelnick, J. (2014). Social policy education for change: South African student perspectives on the global agenda for social work and social development. International Social Work, 57(4), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814527634

- Reichert, E. (2006). Understanding human rights: An exercise book. Sage.

- Reichert, E. (2011). Human rights in social work: An essential basis. Journal of Comparative Social Welfare, 27(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17486831.2011.595070

- Stamm, I. (2023). Human rights–based social work and the natural environment: Time for new perspectives. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 8(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00236-x

- Staub-Bernasconi, S. (2010). Human rights – facing dilemmas between universalism and pluralism or contextualism. In D. Zavirsek, B. Rommelspacher, & S. Staub-Bernasconi (Eds.), Ethical dilemmas in social work: International perspective (pp. 9–24). Faculty of Social Work, University of Ljubljana.

- Staub-Bernasconi, S. (2016). Social work and human rights—linking two traditions of human rights in social work. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, I(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-016-0005-0

- Steen, J. A., & Mann, M. (2015). Human rights and the social work curriculum: Integrating human rights into skill-based education regarding policy practice behaviors. Journal of Policy Practice, 14(3–4), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588742.2015.1044686

- Steen, J. A., Mann, M., & Gryglewicz, K. (2016). The human rights philosophy: Support and opposition among undergraduate social work students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36(5), 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2016.1234534

- Steen, J. A., & Mathiesen, S. (2005). Human rights education: Is social work behind the curve? Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 25(3–4), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v25n03_09

- Stellmacher, J., & Sommer, G. (2008). Human rights education: An evaluation of university seminars. Social psychology, 39(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335.39.1.70

- Strydom, H., & Delport, C. (2011). Information collection: Document study and secondary analysis. In A. S. De Vos, H. Strydom, C. B. Fouche, & C. S. L. Delport (Eds.), Research at grassroots: For social sciences and human services professions (pp. 376–389). Van Schaik.

- Tibbitts, F. (2015). Curriculum development and review for democratic citizenship and human rights education. UNESCO Publishing.

- United Nations Centre for Human Rights. (1994). Human rights and social work: A manual for schools of social work and the social work profession [ Professional Training Series No.1]. United Nations.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2017). World programme for human rights education: Third phase action plan. United Nations and UNESCO.

- Witt, H. (2020). Do US social work students view social work as a human rights profession? Levels of support for human rights statements among BSW and MSW students. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, I(3), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-020-00126-0

- Wronka, J. (2012). Overview of human rights: The UN conventions and machinery. In L. M. Healy & R. J. Link (Eds.), Handbook of international social work: Human rights, development, and the global profession (pp. 439–446). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195333619.003.0066