ABSTRACT

Far from all who complete teacher education end up working as teachers throughout their entire career. At first sight the value of teacher education, in terms of efficiency, seems to be a failure. In the present article we argue that teacher attrition, when defined as whether one is working as teacher or not, is a too blunt measure to gauge whether teacher education has been valuable. With a unique dataset, where we have detailed information on 87 Swedish teacher graduates’ working life across 23 years, we can consider whether activities and/or experiences point to an apparent use of teacher education. In conclusion, we find that in order to get informative estimates of its value it is important to consider it from different perspectives and to consider attrition related to the total working time spent in educational settings across a career rather than percentage leaving teaching after a set of years

Introduction

The evident purpose of teacher education seems simple enough: to enable individuals to work as competent and skilled teachers. Yet a common finding is that many of the recently graduated teachers choose not to go into teaching at all (Luekens, Lyter, and Fox Citation2004), or will postpone entering their teaching careers (Lindqvist, Nordänger, and Carlsson Citation2014). Furthermore, some will take breaks for several years (a.a.) whereas others will start working as teachers but leave the profession after only a few years (Cooper and Alvarado Citation2006; Ingersoll Citation2003, Citation2007; Newberry and Allsop Citation2017). Hence, far from all who complete teacher education end up working as teachers throughout their entire careers, a fact that has caused a discussion and questioning of the quality and even the eligibility of teacher education (DN Citation2006; Lindqvist and Nordänger Citation2018).

Reported attrition figures in the literature vary considerably, with an estimated 30–50% five year attrition rate in the US (Ingersoll Citation2003), the UK (Cooper and Alvarado Citation2006), Norway (Roness Citation2012), Australia (Gallant and Riley Citation2014) and Sweden (Swedish Government Citation2010), but less than 5% in France, the Netherlands and Hong Kong (Cooper and Alvarado Citation2006; den Brok, Wubbels, and van Tartwijk Citation2017). In the sense of producing teachers who steadfastly remain in teaching until retirement age, teacher education appears unsuccessful in several countries, including Sweden. At first sight the value of teacher education, in terms of physical efficiency, i.e. ‘producing a specific outcome with a minimum amount or quantity of waste’, seems to be a failure. In the present article we will, however, try to discuss the value of teacher education from a different viewpoint, arguing that its value depends not only on whether the prospective teachers remain in the teaching profession but also on what they are occupied with while not working as teachers and how they have made use of their teacher education. Teacher attrition, when defined as whether one is working as a teacher or not, is too blunt a measure to gauge whether teacher education has been valuable. A more nuanced way of estimating the value of teacher education may be to complement the ‘pathogenic’ viewpoint, identifying attrition as a negative work outcome, with a ‘salutogenic’ perspective (Antonovsky Citation1987; Yinon and Orland- Barak Citation2017), emphasizing attrition as active career decisions among teachers with a strong sense of agency. To this end, we will make use of a unique dataset (Lindqvist, Nordänger, and Carlsson Citation2014; Lindqvist and Nordänger Citation2016) where we have detailed information about the careers of 87 Swedish teacher graduates for a time period of 23 years. For each teacher graduate, and each year after graduation, we will consider whether their activities and/or experiences point to an apparent use of teacher education, regardless of whether they remain in the profession or not.

Literature review

There is nearly universal agreement that teachers matter to students’ growth and learning and there is equally widespread recognition that students should be taught by qualified teachers. At the same time there is a great deal of disagreement over the ‘character, content and caliber of the education, preparation and credentials prospective candidates ought to obtain’ (Ingersoll, Merill, and May 2014, 2) before being considered qualified to teach. While some argue for rigorous education and restricted entry, others claim that there is no solid empirical research documenting the value of existing entry requirements, licensing or certifications (Ingersoll, Merill, and May 2014). This lack of consensus has created a long-standing demand for empirical research to assess the value of different types of teacher education, their relation to student outcomes (Hattie Citation2009; Kennedy, Ahn, and Choi Citation2008) and also their relation to teacher retention (Ingersoll, Merill, and May 2014). This field of inquiry is unusual on the cross-organizational arena. Empirical research on the added value of practitioners having a particular education or certification is scarce in almost all occupations and professions (Ingersoll Citation2004). What Ingersoll, Merill, and May (Citation2014) found was that the content and substance of preparation matter when it comes to attrition. Graduates with more pedagogy in their education were far less likely to leave teaching after the first year on the job. Other studies claim that attrition rates appear much lower for teachers with teaching qualifications or proven competence in teaching than for teachers without qualifications (den Brok, Wubbels, and van Tartwijk Citation2017) and there is some evidence that poorly prepared teachers are more likely to leave the profession shortly after completing education (Darling Hammond Citation2003). Reports from the UK also indicate that teacher attrition is related to initial training routes and allocation of teacher training (Allen et al. Citation2016). These findings might strengthen the idea of value in a more comprehensive teacher education in relation to retention. But it does not tell us if individuals who have left teaching in schools still make use of their teacher education. In our longitudinal study we have a unique opportunity to study if this is the case.

Analytical framework

In order to assess the value of teacher education, it is instructive to consider how it relates to the respective interests of various parties. To this end, we have construed three stylized levels – schools, individuals, and society – each of which may plausibly be said to play a part in teacher attrition and the use of educational credentials. The conceptualization of the three levels is based on the micro-meso-macro framework often used in social science (Dopfer, Foster, and Potts Citation2004) and on the multi-level perspective in organizational research postulating hierarchical relationships among variables which apply on more than one or two levels (Rousseau Citation1985). To some extent, the conceptualization also includes sociological, managerial and economical ways of problematizing teacher attrition in recent research (Kelchtermans Citation2017).

By thus differentiating between interested parties on different levels, we consciously accentuate ways in which teacher attrition may be problematic, while at the same time allowing ourselves to specifically address the interests of each party and how they relate to the empirical patterns we find.

Teachers who drop out of teaching in schools form one interested party category. Whether their interests are conceived in terms of human capital formation or in terms of more intangible aspects of human identity through life, there is a real possibility that the leavers would experience discontent with the value of teacher training, if it turned out to be a detour or a dead end. Hence the point of view of individuals should be taken into account to ascertain whether this is the case. If we must gauge the interests and fate of those who leave the schools, it is no less important to assess the situation of those who stay on, and their immediate working environment is the school. An analysis of teacher attrition should therefore address how it relates to the school level. Finally, there is reason to include society at large as a level in play. Teacher attrition raises important questions about educational economics. Just as in the case of pilots, engineers or PhDs, it may appear wasteful for society to finance the education of future professionals if they defect into other lines of work.

In order to connect the value of teacher education to teacher attrition in a nuanced way we have also, inspired by Yinon and Orland- Barak (Citation2017), adopted a salutogenic perspective, which allows for identifying attrition not solely as a negative work outcome. The salutogenic perspective contributes to perceiving attrition as career decisions reflecting the meaning that teachers attach to their work. The perspective helps illuminate the strengths of the leavers and their continuing commitment to their calling – to make a difference in the lives of others – as a driving force in deciding to leave the teaching profession.

The school level

From the school level perspective, the main issue is retaining a constant pool of trained teachers. If teachers with professional degrees never enter or choose to leave the school system, then the schools will have to resort to hiring people without these professional degrees. Hence, from a school level perspective, it becomes a problem if 1 000 additional certified teachers are required, but only 500 of those who are certified end up teaching in schools. Another problem comes from high turnover. It is hard for schools to build a stable organization, and for teachers to maintain good collegial relationships, as well as good relationships with students, if a considerable proportion of the work force is constantly shifting (Newberry and Allsop Citation2017). Indeed, high turnover rates can result in negative effects for both the students and the teachers who stayed behind (Ronfeld, Loeb, and Wyckoff Citation2013). Yet these latter types of organizational and instructional disruptions are poorly captured by the teacher attrition figure. Indeed, for a specific school it is of little importance whether it loses a teacher to another type of job or to another school, but for the school system as a whole this is of great importance.

Two types of teacher attrition may, in fact, be beneficial – even necessary – from a school level perspective. The first type of inevitable and not necessarily harmful attrition is the so called ”healthy” attrition (Ingersoll Citation2001) consisting of moderately engaged, disappointed teachers who leave the job because it does not match their sense of professional identity (Lindqvist and Nordänger Citation2016) or who simply do not master it (Watt and Richardson Citation2008). The second type of necessary attrition is related to recruitment of managerial positions in the school system. Schools require other professionals besides teachers, such as principals and project leaders. Teachers can be recruited for these positions, but this will, of course, result in higher numbers of teacher attrition. Low teacher attrition hence necessitates that people who lack teacher experience and teacher education fill such positions. In most cases experiences of teacher education and teaching provide an educational capital that can be used successfully in school management positions (Viggosson Citation2011). Lethwood, Harris, and Hopkins (Citation2008) states that one of the most important criteria for successful school leadership is having a well-grounded sense of context. Having experience of teacher education and teaching would definitely promote such sensibility for the context. Thus, to the extent that teacher education and teaching experience are relevant for school management, low teacher attrition can be problematic here as well.

To sum up, an attrition figure that solely focuses on whether one works as a teacher or not, is rather uninformative for estimating the value of teacher education even from a strict school perspective. Instead, the attrition figure should also reflect whether one stays in the school system or not.

The societal level

From a societal perspective, the question is whether a professional degree yields returns to society as a whole (Bergan and Damian Citation2010; Allen et al. Citation2016). Greatly simplified, this question can be understood as whether the individual is able to do advanced work that the individual would not have been able to do prior to the education. Hence, simply noting that there are many people with teaching degrees who do not teach, there does not seem to be a problem on this level. For example, these people may conduct educational research that requires a teacher background or organize trainee programs at a motor company. The only true loss from a societal perspective are those who end up doing the same type of work as prior to their education, or those who end up in some other type of work that does not make use of their professional education. Importantly, whether a teacher education is valuable or not is not always apparently revealed by the type of occupation held. A teacher may work with improving the education among staff at a large motor company, making good use of his/her teacher training, but appearing as attrition if the figure is based on uninformed statistics. Hence, detailed information from open surveys or interviews is typically necessary to reveal work tasks with sufficient precision to be able to gauge whether individuals make use of their education or not.

The individual level

It has been argued that there are inherent values for individuals with higher education in terms of civic and cultural engagement, life satisfaction, general health (Becchetti, Solferino, and Tessitore Citation2016; OECD Citation2017), not to mention development of general cognitive and intellectual skills (Tam Citation2002). These qualities are inherently difficult to measure improvements in, and perhaps more importantly, impossible to put a value on. Yet the idea is that individuals will grow as a result of attending higher education. Answering this question objectively is beyond the scope of present research. However, we will consider the graduates’ subjective beliefs regarding the meaningfulness of their teacher education during their lives. From this perspective, it is not only a matter of obvious returns to society. For example, three years of education that is highly self-fulfilling during and afterwards, may be meaningful from the individual’s perspective, even if it is economically inefficient. In contrast, a shorter two-year education that is more cost-efficient, but perceived as a necessary evil rather than a self-improving activity, may not be as meaningful from the individual’s perspective. Importantly, people who end up working in activities very far from teaching may still subjectively feel that their education was meaningful to them in that it leads to personal growth in some way. This could be a general aspect of any academic education, for instance regarding improved critical thinking or language skills. Or it could be more or less specific to teacher education, in cases of an increased understanding of people, a pedagogical perspective or personal emotional development.

Individual perceptions of meaningfulness can be considered not only as individual paybacks of higher education but also as benefits for other individuals in society. Decisions to stay in or leave teaching are not always an answer to the question: What is in it for me? It could just as well be an active choice to be able to make a difference for other individuals in society.

Method

For more than 20 years (1993 – ongoing) we have been able to follow a group of 87 Swedish teachers. The first 15 years through semi-structured questionnaires, exchanged between them and their former lecturer at teacher education. This was done annually for the first five years, once after seven years, and once again after 15 years. After the retirement of the former lecturer, we inherited the material and continued to gather data once a year through more systematic questions in formal questionnaires. In total, up until now (November 2017), we have gathered data on 14 occasions. From 2013 we have also conducted follow-up interviews with key informants (N = 48).

The material is unusually informative, since the response rate is very high (see ). The respondents have, in most cases, continued to answer the surveys even though some of them have left their jobs as teachers.

Table 1. Response rate across the years (%).

Even though the questionnaires were not systematically formulated during the first 15 years, the informants have, in all surveys, reported if they work as teachers, where they work and what kind of work they do (including non-teaching work). In survey 1–4, 6 and 9–10 they have also described experiences of and expectations on their work as teachers. In later questionnaires some retrospective information about their career trajectories has been gathered.

With a mixed method approach we have had the possibility of combining particularity with generality, to make quantitative and qualitative data”mutually illuminating” (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011, 24). The mixed approach of the study is sequential (Teddlie and Tashakkori Citation2006), in which qualitative and quantitative procedures run one after the other, in order to sufficiently answer the research questions. In the first stage of the analysis, parts of the mainly qualitative data have undergone basic qualitative analyses in order to be transposed into quantitative variables. (Examples include: working as a teacher, in what subjects and grades, movements in and between schools).

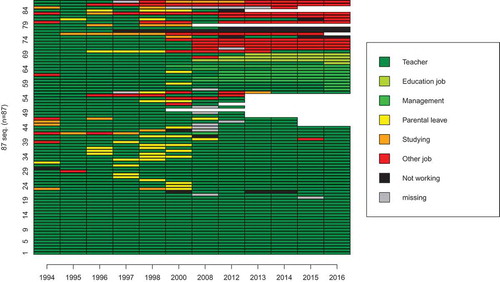

The present study makes use of one of these coded variables: occupation. For each year, an individual’s occupation was coded as: teacher, management, education job, parental leave, studying, other job, not working, or missing data. The granularity of this coding was chosen in order to be able to provide as clear information as possible about the three levels (school, societal, individual), while remaining abstract enough to still provide an overall, zoomed out picture. All coding was based on the most dominant activity of the year (e.g. studying 25% and teaching 75% was coded as teacher). Responses were coded as teacher if respondents were teaching within the regular school system, and as education job if they were teaching outside the regular school system (e.g. education of industrial staff). If their work was outside the educational sector entirely, it was coded as other job. Studying included all types of studies and we did not differentiate between studying to improve one’s teaching or some other subject. However, looking at the trajectories, it is quite easy to see how, for a few individuals, the studies led to a career change and a transition to other job. In not working the reason is not specified and the category includes for example unemployment, sick leave and retirement. Missing data was coded specifically for years where it was not possible to accurately code the current occupational activity.

Having coded the variables in stage one, in stage two we illustrated the individual trajectories by plotting quantitative data from the 87 participants into one figure, using the TramineR package (Gabadinho et al. Citation2009, Citation2011) in R 3.2.2. TramineR is a specialized statistical package for analyzing sequences of nominal (category) data, for example career trajectories and can also be used to calculate a number of summary statistics from this type of data material. Apart from the figure, we also relied on the ‘seqmeant’ command in TramineR to calculate the average duration spent in each state. In other words, the average time spent working as a teacher, studying, etc. The code and data material necessary to reproduce the analysis in the TramineR package can be found at our Open Science Framework project page link: https://osf.io/34xb7/?view_only=ee280aa0bdd14e6e8de9706c2220eb95.

The data also allows further qualitative analyses. At the third stage we have had the possibility of moving beyond figures and numbers and actually study how each individual, on each occasion, describes his/her trajectory. In addition to the overall statistical picture we can return to qualitative data for more detailed information.

Ethical considerations

The nature of the study requires some ethical considerations. Hence, no personal data has been linked to data or results and participants have been given continuous information on the conditions for participation in the study. All participants have been offered opportunities to view research results from the study. Throughout the study, we have carefully balanced the value of the expected knowledge contribution against any negative consequences for those involved.

The cohort

The cohort graduated in December 1993, after 3.5 academic years at a university in a small town in southeastern Sweden. A quarter of them stated that this was their hometown already when they started teacher education and the majority had been recruited from nearby areas. Only 15 of the 87 had moved long distances to become teachers. This is in line with the recruitment of student teachers at other teacher training programs at small colleges in Sweden. Nor do the students’ social backgrounds differ significantly from comparable cohorts recruited to small colleges at this time (Bertilsson, Börjesson, and Broady Citation2008).

Of the 87 participants 63 were women and 24 were men, a slightly higher number of men than in comparable national statistics. In their last year of studies, they were between 22 and 47 years old, with an average age of 24. These figures differ slightly from national statistics at that time, showing an average age of 27 for beginner teacher students. To sum up, the cohort can be seen as fairly representative of students in teacher education in Sweden in the late 20th century. However, from an international perspective there is reason to believe that the characteristics of Swedish teacher students differ slightly from comparable groups. The average age of Swedish students is the highest in Europe (Statistics Sweden Citation2013) and the gender distribution appears to be somewhat more even than in, for example, the U.S. (Bureau of Labor Statistics Citation2013).

At the time when they attended pre-service teacher education, the Swedish version had recently been reformed and divided into two main tracks: ‘the program for early ages’ (grades 1–7) and ‘the program for later ages’ (grades 4–9). All of our respondents attended the program for early ages and were, after graduation, certificated to teach primary and secondary school. But not in all subjects. The program was divided into two areas, language/social sciences or mathematics/natural sciences, which restricted their certification. 78% of the cohort studied social sciences, whereas the rest studied natural sciences. However, this was not equally distributed among women and men, with 84% of the women studying language/social sciences and 63% of the men.

It is important to emphasize that we treat our dataset as a unique cohort case-study. As such, we do not intend to generalize the findings and do not use any inferential statistics such as p-values, confidence intervals, posteriors or Bayes Factors.

Results

The school level

The simplest way of illustrating the value of teacher education is to state the percentage working as teachers after a set number of years. After five years this is 73.6% in our cohort, and at our last measurement after 23 years, it is 63.9%. A more informative estimate, however, is the average percentage of total working time that the individuals spend as teachers during their careers. In the cohort this figure is 76.3%.

A more detailed view can be found in that shows the yearly activities for each of the 87 participants. TraMineR automatically interpolates missing data within sequences for individuals, but not for years when we did not collect data. The figure shows for each individual what they are doing each year. Note that we did not collect data for some years, and therefore the X-axis should be interpreted as fixed years, rather than a true continuous timeline. Also note that an ending sequence (empty cells as opposed to grey cells for missing data) means that a participant has discontinued his/her participation in the study.

Figure 1. Yearly activities for each of the 87 participants.

Note: Grey colour is missing data for that particular year and participant. White fields represent missing data for entire sequences after an individual has opted out of the study.

First of all it may be worth noting that all the graduates in our cohort work as teachers at some point in their careers. Secondly, a majority of the graduates start working as teachers from day one and continue to do so during their careers. Some, however, take some time off for parental leave. There are also a few individuals who work less consistently as teachers, and have unemployment spells or work with other things some years, but later return to teaching and after 23 years still remain in the profession. After 10–15 years a period of transition occurs when some teachers advance into management, and about the same time, a handful move on to other types of educational jobs. This is also a period where a group of teachers leave the profession for other jobs, as can be seen in the transitions in .

From the school level perspective the interesting summary statistics is time spent in the educational system. Since some attrition is actually advancement into management, the figure 76.3% (total working time spent in teaching) increases to 79.9% (total working time spent in teaching and school management).

If we, on top of this, regard parental leave as unavoidable but temporary attrition, the figure increases to 83.9% (total working time spent in teaching, school management and temporary parental leave). Viewing parental leave as only temporary attrition may come as a surprise to some readers. However, in our cohort, parental leave did not trigger leaving the profession permanently for even a single individual. Furthermore, Swedish statistics show that 95% of Swedish women are back in employment after three years of maternal leave (Statistics Sweden Citation2007). This number differs from international studies on returning teachers. In the United States, for example, only about 35–40% of the women who leave the workforce after the birth of a child return to teaching (Vera Citation2013).

The societal level

From a societal perspective, we should also include those who work outside the school system but in the educational sector, which increases the figure to 85.4%. Thus, as shown in , teacher graduates in the cohort spend 85.4% of their working years after graduation as teachers, managers in the school system, or in educational jobs that probably would not have been available had they not had their teacher education. The value of teacher education is therefore, from a societal perspective, best estimated as 85.4%, a figure quite different from the 5-year (73.6%) or 23-year (63.9%) follow-up on whether one is working as a teacher or not.

Table 2. Mean percentage of time spent in different activities across careers.

Looking at the 14.6% ‘failures’ (time spent outside the educational sector) two and half percentage of the time is spent not working at all. This includes sabbaticals, sick leave and early retirement, a probably unavoidable form of attrition. Three percent of the time is spent studying. Looking closely at the material, we see that some study to improve their teacher training, but some studies lead to an entirely different career. This can be seen in , where the trajectories after studying either result in a teaching career or some other career.

Summing up we can see that only 9% of the total working time during 23 years is spent in occupations outside the educational sector. In order to gain an understanding of whether those who have left teaching and the educational sector still feel that their teacher education is contributing to their own or others’ growth, we relied on a qualitative approach based on written information and follow-up interviews.

The individual level

From an individual growth perspective all the ‘leavers’ express a sense of security by having a vocational education to fall back on. Having a business career outside the educational sector does not mean that a return to teaching is unthinkable. It is worth noting that a majority of the individuals in the cohort who have left teaching, express that they would consider returning, when asked 20 years after graduation. What would it take to make them return? In our data, as well as in other studies, we can see that working conditions such as pay (Johnson and Kardos Citation2008), status, manageable assignments (Newberry and Allsop Citation2017) and less accountability pressure (Gallant and Riley Citation2014), are mentioned as crucial aspects. However, the findings also indicate that the chance is low for all leavers to return to school. Individuals who quit teaching due to traumatic turning points, or not being able to develop a personal teacher identity that sits comfortably with their own sense of self, in combination with opportunity structures that enable them alternative careers (Lindqvist and Nordänger Citation2016; Yinon and Orland- Barak Citation2017; Beaudin Citation2008), are probably not tempted to return to a teaching position.

But unwillingness to re-enter teaching does not mean that the commitment for schools, children, learning and education has faded (cf. Peske et al. Citation2001; Anderson and Olsen Citation2006, Citation2007; Hammerness Citation2008). Many of the leavers claim that they, in some sense, are still ‘teachers’.

So you are still, in a way, a teacher?

Yes! Really. That’s what I’m passionate about. (‘Lisa’, web designer, interview, 2014)

Interestingly, even if the leavers are no longer in formal teaching positions, they still describe that they are bringing professional expertise and commitment into society at large. Examples include school board members, working with housing for refugee children and volunteering for BRIS, Children’s Rights in Society.

But then I began to discover that I missed some of it [to be a teacher], to be able to make a difference. As a teacher I actually did things every day that made a difference. And then I started to reflect on precisely what I missed… And then BRIS [Children’s Rights in Society] appeared and I realized that without too much effort I could contribute and make a difference. (‘Britt’, sales and marketing, interview 2014)

Some of the leavers even find themselves making a better contribution to children’s development in a new context outside of school and teaching.

It is fantastic. I can make a tremendous effort for these children. I can make them grow and I can get the support I need… (‘Anders’, works with refugees, interview 2014).

Even though teacher education and teaching experiences seem to have a low value as a merit when looking for another job, many of the former teachers claim that the professional skills they have developed during teacher education or teaching have led to individual growth and skills that come in handy in their new professions. For some of them it also seems like these skills are beneficial to other individuals in the community.

Discussion

In the present research we have tried to show that it is a complicated matter to directly relate teacher attrition to whether or not teacher education has been valuable. We argue that the most relevant estimates include actual teaching but also school management and other educational jobs. Furthermore, we find that the best way of estimating teacher attrition is not to regard the percentage working as teachers a certain year, but rather the overall time spent in teaching and/or educational management. Looking at it this way, we find that 83.9% of the working time for our cohort of Swedish teachers is spent working as teachers or in school management, meaning that the loss for the school system, over a period of 23 years, is just 16.1% of teacher graduates. When we add educational work outside the school system the retention figure is slightly increased to 85.4%, and thus the attrition rate decreases to 14.6% from a societal and economic perspective.

Estimating the value of teacher education from an individual growth perspective for those who do not work as teachers is quite difficult. First, we notice that only 9.3% of the overall working time is spent in occupations with no explicit or implicit relations to educational matters. And then an analysis of subjective opinions reveals a common trait, that even if their working time is spent outside education they apprehend their teacher education as valuable. Perhaps this narration is in part due to people being unwilling to admit that they spent a few years doing something not worthwhile. Yet, one could argue the opposite. If people truly felt that their teacher education had not been useful to them in their careers and lives, we would have heard some disappointed or angry voices. After all, spending several years on an education, often taking loans to be able to do this, not earning any money from a job during the process, etc., for something that is pointless, would be very frustrating. From a salutogenic perspective we can also see that many of the leavers still contribute to the development of other individuals in society. This is something which causes us to point to the potential societal value for this group of ‘highly engaged switchers’ (Watt and Richardson Citation2008) of contributing to the learning and development of people in their communities and society at large.

Recently, proposals to shorten teacher education and to launch fast tracks into the teaching profession have been suggested. In the short term, this could counteract teacher shortages. However, these suggestions contain a potential risk of not giving enough opportunities for teacher students to develop stable professional identities, leading not only to higher attrition rates (Ingersoll Citation2003) but also to serial careers becoming the norm (Roness and Smith Citation2010) and teaching becoming a temporary business. This would then threaten the value of teacher education on all three levels.

It is important to emphasize that the three perspectives we adopted in this article (school, societal and individual) are only examples of useful perspectives. The important message is not that these three perspectives are the most important to consider, but that it matters a great deal what perspective we adopt when interpreting the attrition figures.

In conclusion, we find that in order to get informative estimates of educational value in relation to teacher attrition it is important to consider the matter from different perspectives and – if possible – look at the working time spent throughout a career rather than the percentage leaving after a set number of years. Indeed, attrition is not always permanent and we should be careful when we interpret and make use of general statistics. These figures are necessary and useful and they are all ‘true’ in one sense. But how we should understand and explain them must vary. A recent example is the repeatedly painted picture of Swedish teachers fleeing the profession. With arguments drawn from statistics leading politicians and experts have introduced this ‘truth’ in the school debate. But the picture is somewhat misleading. The same statistics used in another way on the contrary show that Swedish teachers stay longer in the profession today than before and that they also stay longer than comparable professions (DN Citation2016). 2011–2013 the average attrition rate among Swedish teachers was 4.7% per year. Among civil engineers, economists and lawyers, it was about twice as common to change occupations (11.2%, 9.2% and 8.2% respectively). But still teacher attrition is described as an alarming educational issue in Sweden. And it is – in some cases. Returning to the first lines of the introduction of this article: ‘The evident purpose of teacher education seems simple enough: to enable individuals to work as competent and skilled teachers.’ In this article we have focused on the words ‘work as teachers’ and ignored the words ‘competent’ and ‘skilled’. To the latter we could add words such as passionate, appreciated, autonomous and professionally satisfied. Not all attrition can be regarded as lack of resilience (Smith and Ulvik Citation2017) or even negatively, but some of it really is. Teachers leaving the profession due to increased accountability pressure, a loss of collegiality, poor leadership or other working conditions that are possible to affect and avoid present the real problem. We truly agree with Kelchtermans (Citation2017, 965) who argues that as an educational issue ‘teacher attrition and retention refers to the need to prevent good teachers from leaving the job for the wrong reasons’. Using arbitrarily selected international statistics on a one-shot-basis in order to create ‘crisis scenarios’ or to address national problems regarding teacher attrition seems to be a bad idea. Future research on teacher attrition should therefore also try to comprise issues of context, teacher quality and reasons for leaving.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rickard Carlsson

Rickard Carlsson, Ph.D. is a senior lecturer in psychology with a special interest in research methods, meta-analysis and statistics.

Per Lindqvist

Per Lindqvist, Ph.D. and Ulla Karin Nordänger, Ph.D. are professors in education. Their special interests are teachers work, life and knowledge.

References

- Allen, R., C. Belfield, E. Greaves, C. Sharp, and M. Walker 2016. “The Longer-Term Costs and Benefits of Different Initial Teacher Training Routes.” IFS Report 118. Institute for Fiscal Studies. doi:10.1920/re.ifs.2016.0118.

- Anderson, L., and B. Olsen. 2006. “Investigating Early Career Urban Teachers’ Perspectives on and Experiences in Professional Development.” Journal of Teacher Education 57: 359–377. doi:10.1177/0022487106291565.

- Anderson, L., and B. Olsen. 2007. “Courses of Action: A Qualitative Investigation into Urban Teacher Retention and Career Development.” Urban Education 42: 5–29. doi:10.1177/0042085906293923.

- Antonovsky, A. 1987. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well.1st ed. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.1177/0042085906293923.

- Beaudin, B. 2008. “Teachers Who Interrupt Their Careers: Characteristics of Those Who Return to the Classroom.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 15 (1): 51–64. doi:10.2307/1164251.

- Becchetti, L., N. Solferino, and M. E. Tessitore. 2016. “Education Not for Money: An Economic Analysis on Education. Civic Engagement and Life Satisfaction.” Theoretical Economics Letters 2016 (6): 39–47. doi:10.4236/tel.2016.61006.

- Bergan, S., and R. Damian. 2010. “A Word from the Editors.” In Higher Education for Modern Societies – Competences and Values, edited by S. Bergan and R. Damian, 7–18. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Bertilsson, E., M. Börjesson, and D. Broady 2008. “Lärarstudenter, utbildningsmeriter och social bakgrund, 1977–2007.” [Teacher students, educational qualifications and social background, 1997–2007] Sociology of Education and Culture Research Reports, No. 45. Uppsala University

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. “Current Population Study 2011.” www.bls.gov/cps/

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. New York: Routledge.

- Cooper, J. M., and A. Alvarado. 2006. Preparation, Recruitment and Retention of Teachers. UNESCO, IIEP Education policy series No. 5. Brussels: International Academy of Education.

- Darling Hammond, L. 2003. “Keeping Good Teachers. Why It Matters, What Leaders Can Do.” Educational Leadership 60 (8): 6–13.

- den Brok, P., T. Wubbels, and J. van Tartwijk. 2017. “Exploring Beginning Teachers’ Attrition in the Netherlands.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 23 (8): 881–895. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1360859.

- DN 2006. “Var fjärde examinerad lärare borde ha blivit underkänd. [Every fourth graduated teacher should have been failed] DN debatt. Accessed 28 November 2006.” http://www.dn.se/debatt/var-fjarde-examinerad-larare-borde-ha-blivit-underkand

- DN 2016. “Lärarflykten En Modern Myt [Teachers Fleeing the Job - a Modern Myth].” November 2017 https://www.dn.se/nyheter/sverige/lararflykten-en-modern-myt/,

- Dopfer, K., J. Foster, and J. Potts. 2004. “Micro-meso-macro.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 14: 263–279. doi:10.1007/s00191-004-0193-0.

- Gabadinho, A., G. Ritschard, N. S. Müller, and M. Studer. 2011. “Analyzing and Visualizing State Sequences in R with TraMineR.” Journal of Statistical Software 40 (4): 1–37. doi:10.18637/jss.v040.i04.

- Gabadinho, A., G. Ritschard, M. Studer, and N. S. Müller. 2009. Mining Sequence Data in R with the TraMineR Package: A User’s Guide. Geneva: Department of Econometrics and Laboratory of Demography, University of Geneva.

- Gallant, A., and P. Riley. 2014. “Early Career Teacher Attrition: New Thoughts on an Intractable Problem.” Teacher Development 18 (562–580): 562–580. doi:10.1080/13664530.2014.945129.

- Hammerness, K. 2008. “‘If You Don’t Know Where You are Going, Any Path Will Do’: The Role of Teachers’ Visions in Teacher’ Career Paths.” The New Educator 4 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/15476880701829184.

- Hattie, J. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

- Ingersoll, R., L. Merill, and H. May 2014. “What are the Effects of Teacher Education and Preparation on Beginning Teacher Attrition? CPRE Research Reports. Consortium for Policy Research in Education. University of Pennsylvania.

- Ingersoll, R. M. 2001. “Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (3): 499–534. doi:10.3102/00028312038003499.

- Ingersoll, R. M. 2003. Is There Really a Teacher Shortage? Washington: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington. doi:10.1037/e382722004-001.

- Ingersoll, R. M. 2004. “Four Myths about America’s Teacher Quality Problem.” In Developing Teacher Workforce. The 103rd Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, edited by M. Smylie and D. Miretzky, 1–33. Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7984.2004.tb00029.x.

- Ingersoll, R. M. 2007. “Misdiagnosing the Teacher Quality Problem.” CPRE Policy Briefs No. RB-49. Consortium for Policy Research in Education. University of Pennsylvania. doi: 10.12698/cpre.2007.rb49.

- Johnson, S. M., and S. M. Kardos. 2008. “The Next Generation of Teachers. Who Enters, Who Stay and Why.” In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, edited by M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, and D. J. McIntyre, 445–467. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2017. “”Should I Stay or Should I Go?” Unpacking Teacher Attrition/Retention as an Educational Issue.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 23 (8): 961–977. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1379793.

- Kennedy, M. M., S. Ahn, and J. Choi. 2008. “The Value Added by Teacher Education.” In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: Enduring Issues in Changing Contexts, edited by M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, and J. McIntyre, 1247–1272. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Lethwood, K., A. Harris, and D. Hopkins. 2008. “Seven Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership.” School Leadership & Management 28 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1080/13632430701800060.

- Lindqvist, P., and U. K. Nordänger. 2016. “Already Elsewhere – A Study of (Skilled) Teachers’ Choice to Leave Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 54: 88–97. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.010.

- Lindqvist, P., and U. K. Nordänger. 2018. “Separating the Wheat from the Chaff” – Failures in the Practice Based Parts of Swedish Teacher Education.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 17 (1): 83–103. doi:10.26803/ijlter.17.1.6.

- Lindqvist, P., U. K. Nordänger, and R. Carlsson. 2014. “Teacher Attrition the First Five Years – A Multifaceted Image.” Teaching and Teacher Education 40: 94–103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.005.

- Luekens, M. T., D. M. Lyter, and E. E. Fox. 2004. Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2000–2001. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. doi: 10.1037/e609712011-008.

- Newberry, M., and Y. Allsop. 2017. “Teacher Attrition in the USA: The Relational Elements in a Utah Case Study.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 23 (8): 863–880. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1358705.

- OECD. 2017. “Better Life Index.” http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/education/Nov

- Peske, H. G., E. Liu, S. M. Johnson, D. Kauffman, and S. M. Kardos. 2001. “The Next Generation of Teachers: Changing Conceptions of a Career in Teaching.” The Phi Delta Kappan 83 (4): 304–311. doi:10.1177/003172170108300409.

- Roness, D. 2012. “Hvorfor bli laerer? Motivatjon for utdanning och utovning [Why becoming a teacher? Motivation for education and practice].” PhD Dissertation. Bergen: University of Bergen.

- Roness, D., and K. Smith. 2010. “Stability in Motivation during Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 36 (2): 169–185. doi:10.1080/02607471003651706.

- Ronfeld, M., S. Loeb, and J. Wyckoff. 2013. “How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement.” American Educational Research Journal 50 (1): 4–36. doi:10.3102/0002831212463813.

- Rousseau, D. M. 1985. “Issues of Level in Organizational Research: Multi-Level and Cross-Level Perspectives.” Research in Organizational Behavior(7): 1–37.

- Smith, K., and M. Ulvik. 2017. “Leaving Teaching: Lack of Resilience or Sign of Agency?” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 23 (8): 928–945. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1358706.

- Statistics Sweden. 2007. Föräldraledighet Och Arbetslivskarriär. En Studie Av Mammors Olika Vägar I Arbetslivet [Parental Leave and Work Life Careers. A Study on Mothers Trajectories in Work Life]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

- Statistics Sweden. 2013. “Statistik och utvärdering, grundskolan.” [Statistics and Evaluation, Compulsory school] www.scb.se

- Swedish Government. 2010. “Tillgången på behöriga lärare [Supply of certified teachers].” (Report 2010:7). Utredningstjänsten.

- Tam, M. 2002. “Measuring the Effect of Higher Education on University Students.” Quality Assurance in Education 10 (4): 223–228. doi:10.1108/09684880210446893.

- Teddlie, C., and A. Tashakkori. 2006. “A General Typology of Research Designs Featuring Mixed Methods.” Research in the Schools 13 (1): 2–28.

- Vera, C. P. 2013. Career Mobility Patterns of Public School Teachers. Munich: Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

- Viggosson, H. 2011. “Pedagogiskt Kapital. Ett Begrepp under Utveckling [Educational Capital. A Concept under Development].” Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 16 (1): 57–68.

- Watt, M. G., and P. W. Richardson. 2008. “Motivations, Perceptions and Aspirations Concerning Teaching as a Career for Different Types of Beginning Teachers.” Learning and Instruction 18: 408–428. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.002.

- Yinon, H., and L. Orland- Barak. 2017. “Career Stories of Israeli Teachers Who Left Teaching: A Salutogenic View of Teacher Attrition.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 23 (8): 914–927. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1361398.