ABSTRACT

Student teachers have to cope with distressing emotions during teacher education. Coping is important in relation to both attrition and bridging the gap between being a student teacher and starting work. The data consist of semi-structured interviews with 25 student teachers, which were analysed using a constructivist grounded theory framework. The aim of the current study was to examine student teachers’ perspectives on distressing situations during teacher education, as well as how boundaries were established as a way of coping with emotions related to these situations. The findings show that the student teachers’ main concern was to make sense of the imbalance between resources and the demands placed by distressing situations. As a coping strategy, student teachers established professional boundaries linked to emotional labour and relationship maintenance.

Introduction

Student teachers encounter a variety of distressing situations and emotions during their studies (Caires, Almeida, and Vieira Citation2012; Lindqvist et al. Citation2017; Poulou Citation2007). Recent research has examined how emotions and coping with experiences impede student teachers’ development, and could ultimately lead to uncertainty about the role of teacher and questioning their choice of profession (Tiplic, Lejonborg, and Elstad, Citation2016; Yuan and Lee Citation2016). Research on how student teachers cope with distressing situations in the context of teacher education is needed if we are to have a better understanding of attrition from teacher education and the teaching profession. Studying coping as a concept could help to clarify how student teachers adopt strategies to deal with distressing situations in teacher education, and the emotions this involves. This study focuses on coping from the perspective of student teachers. Our objective is to examine student teachers’ perspectives of distressing situations during teacher education, as well as how boundaries were established as a way of coping with emotions related to these situations.

Coping, emotional labour and relationships in teaching

Coping is defined as ‘constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’ (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984, 141). The concept of coping relates to facing and dealing with problems in the environment-person relationship that need to be altered, amended, tolerated or reduced (Folkman & Lazarus Citation1991, Citation1985, Citation1991). Coping strategies are defined as the actions a person uses to take control of the experienced problem. This transactional model of coping with stress focuses on the interaction between the individual and the experienced stress. Stress occurs when there is an imbalance between a person’s resources for mediating or coping with the demands of the environment (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). Therefore, the interpretation of the event is more significant than the event itself, which is also viewed as essential in symbolic interactionism (Charon Citation2007). Emotions are seen as the catalyst of actions, as emotions are defined, isolated, controlled and discussed by humans. Emotions become social when people use them in reflection and interpretation (Charon Citation2007), for example when managing emotions. According to Blumer (Citation1969), the action of humans is in relation to coping with the demands of human life. As we manage emotions, we also create emotions.

Coping is essential in teacher education because teaching is an emotional endeavour (Hargreaves Citation2005). Distressing situations are influenced and determined by social contexts and relationships at school, and teachers must constantly manage their emotions in the student-teacher relationship (Zembylas Citation2005). The general emotional rule is not to display emotions that are too strong or too weak, since this is viewed as unprofessional behaviour. When viewing emotions as constantly managed, emotions can be ‘seen as culturally relevant, public performances, reflecting power relations and mediating between subjective experiences and social practices’ (Zembylas Citation2007, 58) and should be understood from the specific context in which they need to be managed. For example, being angry about a pupil’s behaviour might be linked to the specific power relationship between teacher and pupil. Teaching and developing relational competence in teacher education is an area where further research is needed (Jensen, Skibsted, and Christensen Citation2015).

The emotions of student teachers are here defined as interactive and negotiated within teacher education (Admiraal, Korthagen, and Wubbels Citation2000). Different emotions were present in the perceived distressing situations that the student teachers described. It is not the factual seriousness of the situation but the student teachers’ definition of the situation that we studied, as the definitions are real if they have real consequences for a person’s actions (Charon Citation2007; Thomas and Thomas Citation1928).

Emotional labour is important when discussing coping with emotionally distressing situations. Hargreaves (Citation2005) argues that the emotional labour of teachers has mainly been depicted through negative experiences. Emotional labour is defined as emotions that are performed and acted out, as well as being controlled and suppressed. Some of these enacted emotions, such as surprise and anger, may be acted rather than experienced in order to have a deliberate effect on pupils. Teaching involves emotional rules that regulate which emotions should be expressed or suppressed when teaching (Zembylas Citation2003, Citation2005). For example, anger is not viewed favourably in the teaching profession, whereas emotions related to caring are (Isenbarger and Zembylas Citation2006; Liljestrom, Roulston, & Demarris, Citation2007). When coping with distressing situations in teacher education, previous research has shown relationships to be important as student teachers use social support as a key coping strategy (Gustems-Carnicer and Calderon Citation2012; Paquette and Rieg Citation2016). Seeking support from colleagues is sometimes defined as unproductive because student teachers lack the vocabulary to express their concerns (Caspersen and Raaen Citation2014). Maintaining relationships with colleagues can be problematic in the teaching profession as collegiality is sometimes also the reason for distressing situations in day-to-day work (Löfgren & Karlsson, Citation2016). Working as a teacher involves maintaining relationships with pupils, parents and colleagues. Relationship maintenance is here defined as student teacher’s efforts to uphold relationships, and is understood to be essential when working as a teacher. One example is teachers’ efforts to build trust with pupils (Lassila and Uitto Citation2016).

Boundaries in teacher education

Establishing boundaries here refers to an individual’s ability to identify the possibilities and restrictions of the teaching profession in order to cope. In this respect, boundaries refer to ‘the distinction between what is part of me versus what is not (yet) part of me’ (Akkerman and Bakker Citation2011, 132). The research carried out on student teachers has focused on boundary crossing between the university setting and the work placement education (Hutchinson Citation2011; Tsui and Law Citation2007), and starting to teach (Haggarty and Postlethwaite Citation2012; McCormack and Thomas Citation2003).

Boundaries have been depicted as a discursive tool that focuses on instrumentalism, performance orientation and emotionlessness (Lanas Citation2017). As object constructions, the discursive boundaries evolve over the course of the teacher education (Jahreie and Ottesen Citation2010). Furthermore, boundaries have been viewed as a way to establish how much personal information to disclose in relationship maintenance with pupils. Student teachers reported a need to be aware of the negative and positive consequences that could come from disclosing personal information (Kaufmann and Lane Citation2014). Also, teachers report that they engage in a balancing act between caring and maintaining a level of control in the classroom when discussing boundaries (Aultman, Williams-Johnson, and Schutz Citation2009).

Laletas and Reupert (Citation2016) investigated a group of student teachers establishing appropriate boundaries in relation to the theme of care in the teaching profession. The student-teacher relationship maintenance has been viewed as difficult when establishing and maintaining boundaries relating to care. Gaps in education on the concept of care are a common theme in qualitative studies of student teachers (Kemp and Reupert Citation2012).

We have used the concept of boundaries to explore coping strategies in order to add to the field of knowledge about coping in teacher education. Qualitative research on student teachers’ perspectives of how they experience and deal with distressing situations in teacher education remains scarce. In this paper, boundaries are viewed as coping based on definitions of situations (Charon Citation2007; Thomas and Thomas Citation1928) and tools for internal dialogue, in line with symbolic interactionism (Blumer Citation1969). The aim of the current study was to examine student teachers’ perspectives on distressing situations during teacher education, as well as how boundaries were established as a way of coping with emotions related to these situations.

Methodology

To explore student teachers’ experiences of coping, we used a symbolic interactionism framework (Charon Citation2007) and a constructivist grounded theory design (Charmaz Citation2014). The constructivist version of grounded theory views social reality as constructed and as a part of an ever-changing process, and was chosen because of our interest in the participants’ actions in social processes. Grounded theory is a suitable method when a researcher is interested in the actions and social processes that the participants use to resolve a perceived problem. According to Charmaz (Citation2014), symbolic interactionism offers constructivist grounded theory an open-ended theoretical perspective, creating a theory-method package incorporating curiosity, openness, and a sense of wonder about the social world and its ongoing social actions and processes. The perspective of symbolic interactionism (Blumer Citation1969; Charmaz Citation2014; Charon Citation2007) was useful since subjective meanings are assumed to derive from interaction with others as part of a process of co-construction and interpretation used in communication and practice. According to the Thomas theorem, or ‘the definition of the situation’, people ‘act in a world they define, and although there may actually be a reality out there, their definition is far more important for what they do’ (Charon Citation2007, 129). Therefore, we need to understand human action from the definition of the actor, which is crucial in symbolic interactionism (Blumer Citation1969) and constructivist grounded theory research (Charmaz Citation2014).

Participants

Twenty-five student teachers were interviewed as part of the study. The participants consisted of seven males, 17 females and one non-binary participant. They were 22–56 years old (M = 28), and were completing the final year of their teacher education at six universities in Sweden. Eight student teachers were studying to teach grades 4–6 (age 10–12) and 17 were studying to teach grades 7–9 (age 13–16) at Swedish schools. In Sweden, student teachers carry out 20 weeks of work placement education spread across the teacher education programme, which takes four (grades 4–6) to four and a half years (grades 7–9) to complete. ‘Work placement’ is the term used for attending a school and practising working as a teacher together with a supervisor. During these periods, student teachers teaching responsibilities increase. The longest period of work placement education is nine weeks in duration, and takes place during the final year of teacher education. The participants were yet to complete the longest period of work placement education at the time of data collection.

Data collection

The current study has received ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm. All participants gave their informed consent and were informed about confidentiality and their right to decline participation at any point in the research process. The first author conducted the interviews. During the interviews, he adopted an open and non-judgemental approach through active listening (communicating genuine interest and attention to the participants by being attentive and using responses like ‘mmm’, ‘okay’ and ‘I see’, as well as nodding), and using probing or follow-up questions (Hiller and Diluzio Citation2004). Questions about distressing situations could provoke emotions in the participants, and this was discussed prior to the interviews.

An interview guide was used. The participants were asked to talk about (a) their perceived distressing situations during teacher education, (b) learning to become a teacher, (c) their supervisors for work placement education, (d) their professional approach as a teacher, and (e) their worries about working as a teacher in the near future. The interviews began by asking the participants about positive emotions that they had experienced in teacher education. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. To ensure confidentiality, the names of the participants have been fictionalised. The interviews ranged between 54 and 96 minutes in length, and were carried out during the first semester of their final year of teacher education. Thirteen of the interviews were conducted in a university setting, and twelve were conducted using an online video conferencing service due to the participants’ geographical locations.

Data analysis

Grounded theory methods were conducted to explore and analyse data (Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser Citation1978; Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). Three stages of coding (initial, focused and theoretical) were used. The phases of coding were not performed in a strictly linear way, but were intertwined and flexible, allowing the analysis to remain open and sensitive to data. Initial coding (Charmaz Citation2014) was carried out word by word, sentence by sentence and segment by segment. Initial codes were constructed and constantly compared with data and with each other. The analysis was also guided by analytical questions (see Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser Citation1978), including the following: What is happening in the data? What is going on? What are the main concerns faced by the participants in the actual situations? What do the data suggest? During the next step, focused coding (Charmaz Citation2014), we used the most significant and common initial codes to sift through the large amount of data, and focused codes of boundary setting, emotional labour and relationship maintenance were constructed. The focused codes generated in this phase were more selective and conceptual than the initial codes. The third phase of coding, which was performed more or less in parallel with focused coding, was theoretical coding. The iterative analysis was extended, and we explored and analysed the relationships between our empirical codes using theoretical codes of process and strategies (Glaser Citation1978), thus constructing an analytical story of coherence (Charmaz Citation2014; Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2012). In the analysis, boundaries as a coping strategy was seen as the core concept. The term ‘boundary’ was analysed as the primary coping strategy with aspects of emotional labour and relationship maintenance as processes where boundaries were established, which will be further discussed in the findings. The phases of coding are illustrated in .

Table 1. Example of codes.

The first author conducted the coding in dialogue with the fourth author. All the authors then critically scrutinised their work, resulting in further elaboration, and ensured the trustworthiness of the coding using critical dialogue procedures. Theories were considered as possible lenses and analytical tools through the logic of abduction, theoretical agnosticism and theoretical pluralism (Charmaz Citation2014; Thornberg Citation2012; Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2012). In accordance with an informed grounded theory approach (Thornberg Citation2012), extant concepts justified their place in the analysis by the way they fitted and worked with the data, codes, concepts and emerging theory.

Findings

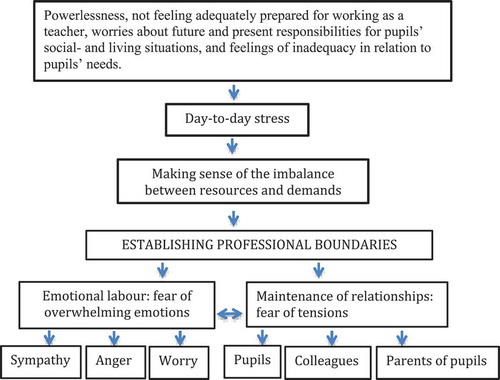

The distressing situations reported by the student teachers related to powerlessness, not feeling adequately prepared for working as a teacher, worrying about their future and their responsibilities regarding pupils’ social progress and living situations, and feelings of inadequacy in relation to pupils’ needs. To cope with these distressing situations, the student teachers established boundaries as coping in relation to aspects of relationship maintenance and emotional labour. The most frequently perceived distressing situations that student teachers reported related to experiences during their work placement education. There were limited experiences of supervisors, or other teacher education activities, that were perceived as distressing. Distressing situations were not considered by the participants to compete in terms of seriousness. Instead, they were seen as contributing towards day-to-day stress. The student teachers’ main concern was having to make sense of the imbalance between resources and the demands that stemmed from experiences connected to the day-to-day stress of teacher education, together with concerns about their future work as teachers.

Imbalance between resources and demands

Boundaries were seen as indispensable to making sense of the imbalance between resources and demands in distressing situations. Boundaries were established as a coping strategy when starting work. For instance, Anders talked about a child in a problematic living situation, where his ‘role started and ended’ as a teacher intervening in family life. When discussing how to handle this, he talked about a lack of resources for what he wanted to do for the pupil:

I think the starting point has to be the pupil. This is something I feel we haven’t really worked with much. When I think back I didn’t have any form of support, and that’s a flaw in teacher education. But it could be something I’ve missed too, I can’t say for sure. (Anders, year 4-6 student teacher.)

Anders concluded that if he noticed a pupil experiencing problems at home, he would leave the issue in the hands of the school management. Another example concerned the feeling of powerlessness. Eva discussed meeting pupils and lacking the ability to influence their actions. Eva said that ‘I felt like, why should they listen to me, or what do I actually have to say, I just have to accept that’ (Eva, year 7–9 student teacher). Eva described a lack of resources to meet demands and the need to establish boundaries when worrying about her ability to perform as a teacher. Alva described working with pupils whom she thought needing special education and how there were no resources available for this. She felt that the lack of resources meant teachers were also supposed to be special educators, even though ‘this is not my strongest side’ (Alva, year 7–9 student teacher). This related to concerns about work tasks that did not align with her ideas of what working as a teacher should include.

Boundaries as a coping strategy, as reported by the student teachers, related to (a) relationship maintenance with pupils, parents of pupils and colleagues, and (b) emotional labour concerning sympathy, anger and worry.

Relationship maintenance

Relationship maintenance was defined as upholding relationships and establishing boundaries as a coping strategy in order to maintain a professional or personal relationship. Relationship maintenance constituted a boundary since there was a professional relationship that was inevitable (with pupils, parents of pupils and teachers). This involved establishing boundaries as a coping strategy since relationship maintenance related to a fear of conflicts with colleagues, parents of pupils, and pupils. The way in which relationships were handled differed between pupils, the pupils’ parents and colleagues.

Pupils

The student teachers frequently referred to the need to build strong relationships with pupils that could be used as a platform to bring about change. They also frequently discussed not being a friend to the pupil, but a grown-up on whom the pupils could depend. The student teachers talked about using relationships as a tool when trying to work with pupils’ social problems. Using relationships to address social injustice or problems in the pupils’ social environments led to a fear of having relationships that could potentially be exhausting. They talked about constantly thinking of ways to resolve pupils’ problems. Relationships with pupils were seen as being dependant on establishing boundaries as a coping strategy for professional duties:

Klara: You shouldn’t take your work home.

Interviewer: Why is that important?

Klara: Otherwise you break. Well, I learned that from previous jobs, like if you try a bit too hard, it becomes a feeling. You end up believing you’re that person, you identify too much and believe you can save the whole world. That will be the hardest part; you’re going to want to save every child, but you can’t.

Interviewer: How come?

Klara: I think you should be a safe person, and being a rock does more than you would think. But it’s not about adopting a child from a troubled home, then it becomes a personal relationship. But of course, you do all you can. That’s the way it is. (Interview with a year 4-6 student teacher.)

Klara described how being excessively motivated to help a pupil or to turn pupils into personal projects would be relationship maintenance that did not include the appropriate boundaries. This was a recurring pattern with the student teachers; they talked about ensuring distance in their relationships with pupils when establishing boundaries as a coping strategy. At least one of the following two rationales could be found among those who emphasised the need to ensure distance in their relationships with pupils: (a) a fear of being too involved in pupils and (b) a statement that teachers should not deal with pupils’ social problems. Both these positions developed the same rationale for boundaries: teachers should not be too personally involved with pupils.

Parents of pupils

The student teachers thought they should have a working relationship with the parents of the pupils (or other care-givers when parents were unavailable), which was sometimes viewed as potentially overwhelming. Klara talked about seeing teachers in work placement education who have excessive contact with the pupils’ parents. ‘I have to explain that I can’t have 30 parents sending me text messages every night’ (Klara, year 4–6 student teacher). Having relationships with parents was discussed as being of paramount importance in ensuring that pupils learn and develop. Ann discussed the need to be calm when communicating with parents ‘because calling or sending e-mails to parents when you are angry is not a good idea, but it might be a mistake you make in the beginning’ (Ann, year 4–6 student teacher). Stefan thought that being criticised as a teacher was common. He had witnessed supervising teachers being questioned about grading, and he concluded that ‘it really is about being pretty specific and direct, and that they have to trust me as a teacher’ (Stefan, year 7–9 student teacher). Relationship maintenance with parents was a source of anticipated distress in their future work duties.

Future colleagues

With regard to relationship maintenance with future colleagues, student teachers had met some teachers that they thought were doing a poor job:

For some people it helps, but for others, like at the school I’m at right now, we have very challenging pupils. Those who are the most challenging you simply have to ignore or separate from the other pupils who they think trigger them. I think that their home situation and other circumstances that affect why they act in a certain way are often forgotten. Teachers shouldn’t be school psychologists, but there are other more helpful alternatives than always picking on them because of how they behave. (Disa, year 7-9 student teacher.)

Disa concluded she felt distressed in the environment she described as she thought neglecting pupils in need was bad practice. As Disa searched for alternative reasons why pupils were behaving as they did, Disa also discussed relationship maintenance with her colleagues. Disa gave examples of trying to influence her supervisor’s conduct, mainly in relation to how the supervisor talked about pupils, but concluded that it was no use. Several student teachers talked about changing schools if the school was not seen to be supportive.

If I’m lucky, I will find the right place on the first attempt, but I believe I will have to work at several different schools before I find the right one. I believe that will be the case. So, I don’t really have those expectations about my colleagues now: it’s more like a bonus. If it turns out well, OK, but I don’t expect anything. It sounds awful, but that’s how it is – a pessimistic view, unfortunately. (Lotta, year 7-9 student teacher.)

In essence, moving away from a school and finding the right place was connected to having professional ideals that matched their colleagues’ ideals: ‘School is kind of what your colleagues make it.’ (Linn, year 4–6 student teacher).

Emotional labour

Student teachers were inclined to view the work within the school context as emotionally charged. Emotional labour was described as dealing with emotions and regulating them on a daily basis. Emotional labour constituted professional boundary setting, since student teachers established boundaries as a coping strategy to limit distressing emotional responses and thus used a coping strategy. According to the student teachers, there was a need to establish boundaries in relation to anger, sympathy and worry. These emotions were defined in the analysis as the primary and most common emotions that the participants discussed, and as such they were present in the data. These emotions were seen as an inevitable part of teaching, and there was a fear of the consequences of these emotions. An overarching fear of emotions becoming overwhelming created a need to establish boundaries relating to these specific emotions.

Anger

The majority of the student teachers had experiences involving anger, either being angry themselves or witnessing other teachers being angry. Student teachers viewed anger as a ‘necessary evil’ – they discussed having to show anger at some point. Other examples of anger were viewed as unnecessary, especially if the anger was expressed in the form of other teachers scolding pupils. Anger had to be controlled, not unleashed, and establishing boundaries as a coping strategy regarding anger was necessary:

And I also believe that I’m a slightly afraid to judge pupils who bully. Getting angry at that person instead of thinking about why this pupil acts this way, what happened in the pupil’s life, what pupil feels, and that’s something I work with a lot. I think it’s easy to react with anger, but you also have to react with understanding. (Lena, year 7-9 student teacher.)

Lena discussed the need to consider a different view, seeking to understand rather than to scold and be angry. Since anger was perceived as inevitable, establishing boundaries was seen as a strategy for coping with, controlling and repressing anger that might otherwise have undesired consequences.

Sympathy

Sympathy was another emotion related to boundaries as a coping strategy. Sympathy is here defined as emotions of pity and sorrow for a pupil’s situation. In order to avoid being overwhelmed, sympathy needed to be controlled. Student teachers reported experiences of distressing situations that had evoked strong feelings of sympathy for their pupils. As this was experienced as distressing, student teachers tried to cope by establishing boundaries in connection with sympathy and not constantly thinking about pupils:

I’m kind of a brooder, so that’s the sort of stuff that I’ll have more trouble with. Not letting go but wondering how things are really going and what to do about it. You have so much influence over the pupils, both academically and socially, like their wellbeing. (Catrin, year 4-6 student teacher.)

Catrin discussed the brooding that she thought would be part of her future work. She believed she could influence a pupil’s situation, resulting in a vast number of possible actions. Constantly thinking about ways to act was disturbing, and she considered downsizing her ambitions by establishing boundaries for herself in terms of how much sympathy she should allow herself to feel.

Another aspect of sympathy was witnessing teachers who the student teachers thought, despite having the ability, lacked the desire to care for their students’ specific needs. Student teachers displayed expectations of a best practice in relation to sympathy.

Yeah, well stuff like that. That they don’t care, that you don’t think the teachers care and like, “No I don’t have time, I have my next lesson”. And I understand that it’s probably very strenuous and that you have a lot to do. But I think that if you walk along a hallway and see someone sitting alone, you should ask why that person is sitting alone. (Annika, year 7-9 student teacher.)

Some student teachers, like Annika, thought that some teachers did not have enough sympathy. Student teachers sometimes met teachers whom they perceived as being unmotivated to show sympathy towards students’ well-being. A supervising teacher was reported to have told a student teacher not to walk along hallways because ‘you can always find some pupil in the hallway who’s being picked on or doesn’t feel well at that particular moment’ (Pia, year 7–9 student teacher), and this took time away from other work tasks.

Worry

In relation to the imminent prospect of becoming a practising teacher, the student teachers expressed worries about the nature of the work, their ability to perform the job, and their suitability for the position: ‘I can’t get hurt so easily, or I can’t be like, I need to work with myself./ … /My fears generally, and that has been a worry, like, will I be able to do this?’ (Katarina, year 4–6 student teacher). In relation to worry, introspection about their qualities was important. Student teachers associated certain qualities they lacked with the boundaries they needed to establish. For example, establishing boundaries as a coping strategy was necessary for Katarina in relation to worrying about being easily hurt. Malte discussed how being in distressing situations made him more aware of his limitations when it came to socialising:

Malte: but I get a feeling that I don’t really handle new social situations particularly well. I am afraid of new social relationships. (Interview, year 4-6 student teacher)

In relation to worry, the process of boundary setting involved either expanding existing boundaries or establishing boundaries as a strategy for coping with worry.

Boundaries and coping

The student teachers’ main concern was to make sense of the imbalance between resources and demands. Boundaries as a coping strategy involved student teachers regulating their working environment and dealing with demands, as well as for dealing with emotions and relationships. These boundaries were linked to establishing best practice and protecting against fear of anger, worry and sympathy. Using professional boundaries as a coping strategy also provided resources with which to meet demands. The need to establish boundaries was primarily a result of having experienced an imbalance between resources and demands. A grounded theory of establishing boundaries as a coping strategy is depicted in .

The analysis showed how boundaries were affected by relationship maintenance and emotional labour. Relationship maintenance commonly leads to emotional labour. The process was seen as being reciprocal. For example, by establishing boundaries concerning anger, the relationships with pupils were affected, and establishing boundaries for appropriate relationships with pupils influenced the student teachers’ ability to have sympathy for the pupils. This means that the processes of emotional labour and relationship maintenance influenced each other, and were thought to affect how boundaries were established. When having to control emotions involved in relationship maintenance, problematic events led to a need for emotional labour concerning feelings of anger, for example when questioned by a parent of a pupil.

Discussion

This study of student teachers’ coping highlights a number of new aspects of coping in distressing situations during teacher education. The unique contribution of this study is the concept of establishing boundaries as a coping strategy. The symbolic interactionism framework contributes by allowing the self to be viewed as an object (Blumer Citation1969; Charon Citation2007) and could enable boundaries to be established around the distressing situations experienced by student teachers, primarily during work placement education. By establishing boundaries as a coping strategy, the problem is focused on and the action undertaken is central. Because strong emotions were not discussed as always being productive, teachers viewed their emotional response as needing to be supressed. Boundaries alleviated distressing situations by providing ways to reduce the emotional intensity of these situations (Hargreaves Citation2000). Zembylas (Citation2003) showed how emotions are performed, used and supressed as teachers establish rules on the use of emotions in teaching. Jokikokko (Citation2016) considers it impossible to eliminate emotions from teaching, and addresses the tendency in teacher education to allow student teachers to deal with distressing situations on their own, which is confirmed in our study. Boundaries around the theme of care, and in relation to disclosing personal information in relationships with students (Aultman, Williams-Johnson, and Schutz Citation2009; Laletas and Reupert Citation2016), are present in our study. Conversely, the student teachers in this study discussed having a relationship with pupils as being important, but did not discuss any positive aspects of revealing personal information. Instead, this was problematised as being too much of a friend to pupils. They coped with the emotional challenge that may be experienced by establishing boundaries as a coping strategy to alleviate, amend or change the experience, and by not disclosing personal information.

In previous research, boundaries have highlighted moving between arenas of teacher education (Hutchinson, S. 2011; Tsui and Law Citation2007) or starting to teach (Haggarty and Postlethwaite Citation2012). With regard to Lanas (Citation2017), we here depict how boundaries are used as discursive tools to cope with distressing situations. This study views boundaries as an action undertaken by the person in relation to the self, as a coping strategy to resolve concern about the mismatch between demands and resources. This way of viewing boundaries as a coping strategy is a contribution to the existing literature about boundaries in teacher education.

Limitations

We would like to point out some limitations of the study. The study used interview data and reported events. In the analysis, we relied on the way in which student teachers talked about distressing situations and coping. Further ethnographic studies, including both observations and interviews, could be carried out in order to enhance the ecological validity and to gain a deeper and fuller understanding of how student teachers cope with distressing situations. The grounded theory was constructed in interplay between the researchers and the participants (data, codes and findings were co-constructed), and should be considered as such. However, in line with a constructivist position of grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2014), we do not claim to offer a precise picture but rather an interpretive portrayal of the phenomenon studied. The questions in the interview protocol asked about distressing situations in a straightforward manner, which could result in student teachers voicing concerns for the first time, thus leading to distressing emotions. Even so, the process of discussing the issues was described by the student teachers as being productive rather than unsettling. The transferability of the study is limited by the small size of the sample, and the sample of Swedish student teachers may or may not differ from other groups of student teachers. However, in qualitative research, generalisability has been discussed as a form of interpretation work, such as ‘generalization through recognition of patterns’ (Larsson Citation2009) in which findings should be considered as a working model or a set of working hypotheses (cf. Glaser Citation1978), which has to consider the local conditions and be seen as modest speculations on the possible applicability of findings in other situations (Patton Citation2002).

Practical implications

This study describes establishing boundaries as a coping strategy with the mismatch between resources and demands. The conclusions of the study imply that student teachers establish boundaries around relationships and emotions to alleviate distressing situations regarding day-to-day stress, which mainly relate to emotional labour and relationship maintenance. This is relevant in teacher education, in order to support student teachers and to enable their experiences of emotional labour and relationship maintenance to be used in teacher education. Discomfort in teacher education can be used as a tool in professional development (Amir et al. Citation2017). The findings of the study suggest that it is relevant to discuss establishing boundaries in the teaching profession within teacher education. To make use of the perspectives of student teachers on establishing boundaries, a course including a pedagogical model with a connection to the student teachers’ experiences and expectations of working as a teacher (critical incident analysis, case methodology and problem-based learning) might be a way of beginning to discuss boundaries and coping. In the suggested models, presenting a problem is central. The problem/case/incident could involve establishing boundaries. In addition, closer work with supervisors (cf. Trevethan Citation2017) could be valuable since we found that work placement education is the most prominent arena where coping was needed. This implies that student teachers could be given more support with regard to establishing boundaries during work placement education in schools as part of their teacher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henrik Lindqvist

Henrik Lindqvist is a PhD student at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University in Sweden focusing on student teachers learning from, and coping with, distressful situations in teacher education. He is part of a research group investigating both student teachers and medical students distress related to their professional education. Other research interests include special education.

Maria Weurlander

Maria Weurlander, PhD, is associate professor of Technology and learning at the unit of Higher Education Research and Development at the school of Industrial Engineering and Management (ITM) at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. Her main research focuses are on student learning in higher education, and student teachers’ and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with distressed situations during their training.

Annika Wernerson

Annika Wernerson, PhD, MD, is professor in renal- and transplantation science at the department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC) at Karolinska Institutet, where she also is Dean of higher education. Her research areas in medical education focus on learning in higher education and medical students’ and student teachers´ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training and early professional life.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg, PhD, is Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University in Sweden. He is also the Secretary of the Board for the Nordic Educational Research Association (NERA). His main focuses are on (a) bullying and peer victimisation among children and adolescents in school settings, (b) values education, rules, and social interactions in everyday school life, and (c) student teachers and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with distressed situations during their training.

References

- Admiraal, W. F., F. A. Korthagen, and T. Wubbels. 2000. “Effects Of Student Teachers’ Coping Behaviour.” British Journal Of Educational Psychology 70: 33–52. doi: 10.1348/000709900157958.

- Akkerman, S. F., and A. Bakker. 2011. “Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects.” Review of Educational Research 81: 132–169. doi:10.3102/0034654311404435.

- Amir, A., D. Mandler, S. Hauptman, and D. Gorev. 2017. “Discomfort as a Means of Pre-service Teachers’ Professional Development–an Action Research as Part of the ‘research Literacy’ Course.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40: 231–245. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1284197.

- Aultman, L. P., M. R. Williams-Johnson, and P. A. Schutz. 2009. “Boundary Dilemmas in Teacher–student Relationships: Struggling with “The Line”.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25: 636–646. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.10.002.

- Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism. Berkeley. CA: University of California Press.

- Caires, S., L. Almeida, and D. Vieira. 2012. “Becoming a Teacher: Student Teachers’ Experiences and Perceptions about Teaching Practice.” European Journal of Teacher Education 35: 163–178. doi:10.1080/02619768.2011.643395.

- Caspersen, J., and F. D. Raaen. 2014. “Novice Teachers and How They Cope.” Teachers and Teaching 20: 189–211. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.848570.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Charon, J. M. 2007. Symbolic Interactionism: an Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. 9th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Glaser, B. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., and C. Calderon. 2012. “Coping Strategies and Psychological Well-being among Teacher Education Students. Coping and Well-being in Students.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 28: 1127–1140. doi:10.1007/s10212-012-0158-x.

- Haggarty, L., and K. Postlethwaite 2012. “An Exploration of Changes in Thinking in the Transition from Student Teacher to Newly Qualified Teacher.” Research Papers in Education 27: 241–262. doi:10.1080/02671520903281609

- Hargreaves, A. 2000. “Mixed Emotions: Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Interactions with Students.” Teaching and Teacher Education 1: 811–826. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7.

- Hargreaves, A. 2005. “Educational Change Takes Ages: Life, Career and Generational Factors in Teachers’ Emotional Responses to Educational Change.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21: 967–983. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.007.

- Hiller, H. H., and L. Diluzio. 2004. “The Interviewee and the Research Interview: Analysing a Neglected Dimension in Research.” CRSA/RCSA 41: 1–26.

- Hutchinson, S. A. 2011. “Boundaries and Bricolage: Examining the Roles of Universities and Schools in Student Teacher Learning.” European Journal of Teacher Education 34: 177–191. doi:10.1080/02619768.2010.548860.

- Isenbarger, L., and M. Zembylas. 2006. “The Emotional Labour of Caring in Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22: 120–134. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.002.

- Jahreie, C. F., and E. Ottesen. 2010. “Construction of Boundaries in Teacher Education: Analyzing Student Teachers’ Accounts.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 17: 212–234. doi:10.1080/10749030903314195.

- Jensen, E., E. B. Skibsted, and M. V. Christensen. 2015. “Educating Teachers Focusing on the Development of Reflective and Relational Competences.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 14: 201–212. doi:10.1007/s10671-015-9185-0.

- Jokikokko, K. 2016. “Reframing Teachers’ Intercultural Learning as an Emotional Process.” Intercultural Education 27: 217–230. doi:10.1080/14675986.2016.1150648.

- Kaufmann, R., and D. Lane. 2014. “Examining Communication Privacy Management in the Middle School Classroom: Perceived Gains and Consequences.” Educational Research 56: 13–27. doi:10.1080/00131881.2013.874145.

- Kemp, H. R., and A. Reupert. 2012. “There’s No Big Book on How to Care”: Primary Pre-Service Teachers’ Experiences of Caring.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 37: 114–127. doi:10.14221/ajte.2012v37n9.5.

- Laletas, S., and A. Reupert. 2016. “Exploring Pre-service Secondary Teachers’ Understanding of Care.” Teachers and Teaching 22: 485–503. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1082730.

- Lanas, M. 2017. “An Argument for Love in Intercultural Education for Teacher Education.” Intercultural Education 28: 557–570. doi:10.1080/14675986.2017.1389541.

- Larsson, S. 2009. “A Pluralist View of Generalization in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 32: 25–38. doi:10.1080/17437270902759931.

- Lassila, E., and M. Uitto. 2016. “The Tensions between the Ideal and Experienced: Teacher–student Relationships in Stories Told by Beginning Japanese Teachers.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 24: 205–219. doi:10.1080/14681366.2016.1149505.

- Lazarus, S. R. 1985. “The Psychology of Stress and Coping.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 7: 399–418.

- Lazarus, S. R. 1991. Emotion and Adaption. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Lazarus, S. R., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer.

- Liljestrom, A., K. Roulston, and K. Demarrais. 2007. “There’s No Place for Feeling like This in the Workplace”: Women Teachers’ Anger in School Settings.” In Emotion in Education, edited by A. Schutz, & R. Pekrun, 275–291. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg. 2017. “Resolving Feelings of Professional Inadequacy: Student Teachers’ Coping with Distressful Situations.” Teaching and Teacher Education 64: 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019.

- Löfgren, H., and M. Karlsson. 2016. “Emotional Aspects of Teacher Collegiality: A Narrative Approach.” Teaching and Teacher Education 60: 270–280. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.022.

- McCormack, A. N. N., and K. Thomas. 2003. “Is Survival Enough? Induction Experiences of Beginning Teachers within a New South Wales Context.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 31: 125–138. doi:10.1080/13598660301610.

- Paquette, K. R., and S. A. Rieg. 2016. “Stressors and Coping Strategies Through the Lens Of Early Childhood/special Education Pre-service Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 57: 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.009.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Poulou, M. 2007. “Student-teachers’ Concerns about Teaching Practice.” European Journal of Teacher Education 30: 91–110. doi:10.1080/02619760600944993.

- Thomas, W. I., and D. S. Thomas. 1928. The Child in America. New York: Alfred A.

- Thornberg, R., and K. Charmaz. 2012. “Grounded Theory.” In Qualitative Research: an Introduction to Methods and Designs, edited by S. D. Lapan, M. Quartaroli, and F. Reimer, 41–67. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

- Thornberg, R. 2012. “Informed Grounded Theory.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 56: 243–259. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.581686.

- Tiplic, D., E. Lejonberg, and E. Elstad. 2016. “Antecedents of Newly Qualified Teachers’ Turnover Intentions: Evidence from Sweden.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 15: 103–122.

- Trevethan, H. 2017. “Educative Mentors? the Role of Classroom Teachers in Initial Teacher Education. A New Zealand Study.” Journal of Education for Teaching 43: 219–231. doi:10.1080/02607476.2017.1286784.

- Tsui, A. B., and D. Y. Law. 2007. “Learning as Boundary-crossing in School–university Partnership.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23: 1289–1301. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.003.

- Yuan, R., and I. Lee. 2016. “‘I Need to Be Strong and Competent’: A Narrative Inquiry of A Student-teacher’s Emotions and Identities in Teaching Practicum.” Teachers and Teaching 22: 819–841. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1185819.

- Zembylas, M. 2003. “Emotions and Teacher Identity: A Poststructural Perspective.” Teachers and Teaching 9: 213–238. doi:10.1080/13540600309378.

- Zembylas, M. 2005. “Discursive Practices, Genealogies, and Emotional Rules: A Poststructuralist View on Emotion and Identity in Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21: 935–948. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.005.

- Zembylas, M. 2007. “Theory and Methodology in Researching Emotions in Education.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 30: 57–72. doi:10.1080/17437270701207785.