ABSTRACT

A study was conducted to explore the impact of professional development related to the individual education plan (IEP) process on teachers’ understanding and practices in the Republic of Ireland (RoI). This paper reports on part of that research, focusing on teachers’ collaborative practices in the IEP process. In the RoI, teachers working as special education teachers (SET) can avail of State-funded professional development through an award-bearing model provided by universities. The study combined survey of three cohorts of teachers who undertook this professional development course in one university with follow-up focus groups, observation and documentary analysis in five schools. Challenges to effective team functioning were identified in relation to the constructs of joint instructional work, communication, and values and ethics. Building on these constructs, this paper proposes a framework for developing competencies in collaborative practice for inclusion of students with IEPs with implications for practice and for teacher educators.

Introduction

Collaboration and collaborative practices are widely accepted as orthodoxy for supporting inclusive education (Ainscow and Sandhill Citation2010) with many calls for modelling ways of working with and through others (Florian and Spratt Citation2013; Pantic and Florian Citation2015). Inclusive education remains a contested concept, without a universally agreed definition. Its implementation within and across countries arguably varies significantly and continues to be met with challenges (Artiles, Kozleski, and Waitoller Citation2011; Florian Citation2014; Loreman, Forlin, and Sharma Citation2014). In the Irish context, these include a lack of teacher efficacy, insufficient access to teacher education (O’Gorman and Drudy Citation2010; Rose et al. Citation2015) and a lack of collaborative practice to support individual learning within curriculum planning and teaching (King, Ní Bhroin, and Prunty Citation2018). This arguably reflects Pantic and Florian’s (Citation2015) concept of ‘inclusive pedagogy as an approach that attends to individual differences between learners while actively avoiding the marginalisation of some learners’ (334). While inclusive pedagogy relates to including all learners, the emphasis in this paper is on the inclusion of learners with special educational needs (SEN).

Planning for individual learning needs has been a key feature of educational programmes internationally for decades (UNESCO Citation1994). It is reflected in the practice of personalising learning to abilities and interests of each and every student, pursued by schools with a commitment to school improvement (Ferguson Citation2008). Furthermore, it is a fundamental tenet of differentiation which ‘involves attempting to cater for the individual needs of the student/pupil while teaching in an ordinary classroom’ (Griffin and Shevlin Citation2007, 150).

Illustrative of planning for individual learning needs is the individual education plan (IEP), adopted by many countries as a tool for individualising teaching and learning for students with SEN while ensuring access to the general curriculum (NCSE Citation2006; Loreman, Deppeler, and Harvey Citation2010; Wakeman, Karvonen, and Ahumada Citation2013). Moreover, the policy status of individual education plans is directly linked to legislation in a number of countries (DfES Citation2001; Ekstam, Linnanmäki, and Pirjo Citation2015; Forlin Citation2001; New Zealand Ministry of Education Citation2004; SFS Citation1994).

A key principle underpinning the development of individualised educational planning is collaboration. Indeed, collaborative decision-making and problem-solving is at the core of inclusive education for all students (Ainscow and Sandhill Citation2010; Clarke Citation2000; EC 2013). However, the challenges of collaboration in the individualised planning process are widely documented (Riddell Citation2002; Tennant Citation2007) with reports that individual education plans are not being used as a collaborative tool between parents, teachers and other educational professionals (Stroggilos and Xanthacou Citation2006). This paper draws on a mixed methods study which was conducted with the aim of exploring the impact of professional development related to the individual education plan process on the understanding and practice of teachers at primary and post-primary level in the Republic of Ireland (RoI) 2–4 years following completion of the course. The paper reports on part of that research, focusing on teachers’ collaborative practices in the individualised educational planning process. This resulted in the design of a framework with potential to support the development of collaborative practices for inclusion and thus, with implications for teacher education. This aspect of the study is of relevance to those who lead and are involved in the individualised educational planning process, to teacher educators who prepare teachers for engagement with this process, and to policymakers who have it in their power to devise and influence policy to create and sustain meaningful collaborative practices that support inclusion.

Policy context

In the Republic of Ireland (RoI), the Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act (Government of Ireland Citation2004) was introduced to make individual education plans mandatory for all children with special educational needs. This legislation was supported by the publication of a comprehensive set of Guidelines on the Individual Education Plan Process (NCSE Citation2006). However, amidst economic recession in 2008, there was a deferral on commencement of certain sections of the Act including those pertaining to individual assessment and education plans. In the intervening decade, there has been increasing evidence to suggest that schools in RoI are taking the initiative in developing individual education plans, though with variability and inconsistency in practice (Bergin and Logan Citation2013; Douglas et al. Citation2012; Ní Bhroin, King, and Prunty Citation2016; Prunty Citation2011; Rose et al. Citation2012).

Moving from ‘a deficit model of resource allocation to one requiring a social, collective response from schools’ (Fitzgerald and Radford Citation2017, 453), policy development saw the introduction in September 2017 of a more equitable system of resource allocation for all learners including those with SEN in mainstream schools, underpinned by the principles of inclusion (NCSE Citation2014). The significance of this policy development for individualised planning is that it has been accompanied by a departmental directive on educational planning which stipulates that the student’s ‘support plan should include clear, measurable learning targets and specify the resources and interventions that will be used to address student needs’ (DES Citation2017, 21). It also requires that the plan is developed through a ‘collaborative process involving relevant teachers, parents/guardians, the pupils themselves and outside professionals’ (DES Citation2017, 21). Additionally, it is directed that this ‘individualised planning process’ includes ‘regular reviews of learning targets as part of an ongoing cycle of assessment, target setting, intervention and review’ (DES Citation2017, 22). Although the nomenclature is changed, in essence, student support plan and individual education plan share the same underpinning principles. Among these principles are that the individualised planning process includes the setting of specific, measurable targets, is ongoing and collaborative, with parental involvement, and with the student at the centre and involved in contributing to development and review of the plan (NCSE Citation2006; Barnard-Brak and Lechtenberger Citation2010). Rather than relying on individualised approaches (Pantic and Florian Citation2015), it is anticipated that ‘individualised learning needs can be addressed … in the collective setting of the classroom’ (DES Citation2017, 18).

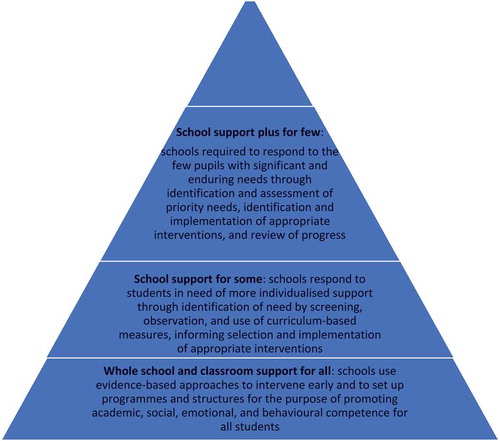

To promote the social and collective response from schools in delivering on the policy of more equitable allocation of support, policy guidelines outline a three-level pyramid of support (DES Citation2017). Mirroring the three-tier support model incorporated in Response to Intervention (RtoI) (Fuchs and Vaughn Citation2012), utilised in a number of European countries, and mandated in legislation, for example, in Finland (Ekstam, Linnanmäki, and Pirjo Citation2015), these levels of graduated support are illustrated in .

Additionally, it is a requirement that a student support file which includes the support plan be developed for those students eligible for the level of school support plus for few (DES 2017). This is not to imply that individualised educational planning may not be required by students eligible for lower levels of support. However, by aligning the requirement of a student support file with the most intensive of the three levels of support, this lessens the documentation that would have been required had the relevant sections of EPSEN (Government of Ireland Citation2004) been mandated, circumventing a commonly levelled criticism that paperwork relating to individual education plans is too extensive (Andreasson, Asp-Onsjo, and Isaksson Citation2013; Ekstam, Linnanmäki, and Pirjo Citation2015).

This brief overview of policy relating to the process of individualised educational planning in RoI serves to highlight a commitment to individually relevant learning informed by cyclical motions of planning (assessment, target setting), intervention and review, based on collaboration of all involved in the student’s development, and documented in a student support plan. However, ‘rules and regulations’ of educational policy ‘promulgated’ by government (Sykes, Schneider, and Ford Citation2009, 1) run the risk of remaining aspirational unless embraced by those at the chalk-face who are charged with the task of delivering on the policy. To this end, exploration of the impact of professional development related to the individual education plan process on the understanding and practice of teachers, with potential to shed light on the enactment of policy requirements relating to collaboration and with implications for teacher education is timely.

Theoretical background

The theoretical context shedding light on the issue of this paper draws from literature on teacher professional learning, individualised educational planning and teacher collaboration. This literature informs the conceptual framework for analysis of findings detailed at the end of this section.

Teacher professional learning

In this paper, teacher professional learning is conceptualised as change in cognition leading to changes in teaching practice and students’ learning outcomes (Attard Tona and Shanks Citation2017; King Citation2014; Levin and Nevo Citation2009) which can occur in multiple contexts including classrooms, school communities and professional development programmes and workshops (Borko Citation2004; Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002). Change may be evident in teachers’ knowledge, skills and attitudes, and is contingent upon the acquisition of new concepts, new skills and new processes intrinsic to teaching (Desimone Citation2009; Guskey Citation2009). Models of professional learning have been identified (Hoban Citation1996; Kennedy Citation2014), ranging from transmission of new knowledge and skills led by experts, to collaborative and active construction of knowledge for transformative practices relying on either the collective expertise of group members or the combined expertise of group members led by an external expert. Kennedy (Citation2014) deemed accredited programmes within teacher education to be in the malleable category meaning they may or may not lead to transformative practices.

In terms of efficacy for facilitating and sustaining pedagogical change, research favours models of professional learning that involve active and inquiry-based learning, that are collaborative, of high professional relevance to all group members and embedded in the contexts of teachers’ work (Cordingley et al. Citation2003; Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011; Sjoer and Meirink Citation2016; Timperley et al. Citation2007; Vermunt and Endedijk Citation2011). Reflecting the social constructivist concept of scaffolding (Vygotsky Citation1978), research supports professional learning approaches that draw on the expertise of a more knowledgeable other to support teachers in developing deeper understanding, embracing new beliefs and being independent problem-solvers in their own contexts (Butler et al. Citation2004; Timperley and Alton-Lee Citation2008). A knowledgeable other may be in the form of interactions with more effective peers (Jackson and Bruegmann Citation2009) highlighting the importance of collaboration. Apart from encouraging teachers to enact continually and adapt new practices to context, the role of more knowledgeable other in sharing feedback on practice is pivotal to teachers’ learning with consequent changes to practice (Butler et al. Citation2004). In terms of focus, professional learning content that balances knowledge of specific curriculum areas with knowledge of the most effective teaching strategies for facilitating student learning, referred to in the literature as pedagogical content knowledge (Fraser Citation2005; Shulman Citation1986), is more likely to produce meaningful change to teachers’ practices with higher student outcomes (Saxe and Gearhart Citation2001). Research also highlights the pivotal role of leadership in developing and sustaining changes to practice by fostering collaboration between teachers through building collegiality based on trust and respect (King Citation2014).

Individualised educational planning for inclusion

A review of research supports the view that the pedagogical value of the individual education plan is dependent on its quality and perceived efficacy. The significance of quality of individualised educational planning highlighted by research indicates that this is determined by accuracy of assessment data to identify individual needs, effective assessment practices to inform instructional planning, and contextualisation of individual plan into whole-school planning and delivery of curriculum (Blackwell and Rossetti Citation2014; Cooper Citation1996; Rose and Shevlin Citation2010). However, studies focusing specifically on the quality of individualised educational planning in mainstream settings present findings to indicate problems with the extent to which instructional supports and individualised learning goals are appropriate to ensure student participation in general education programmes (Kwon, Elicker, and Kontos Citation2011; Kurth and Mastergeorgre Citation2010; Ruble et al. Citation2010). Indeed, reconciling individually relevant learning with general curriculum standards has long been recognised as a significant undertaking for many teachers (Erickson and Davis Citation2015). Collaborative decision-making between mainstream class teachers and special education teachers based on careful consideration of the individual’s learning goals and the typical classroom practices is advocated to facilitate contextualisation of the individual plan within the general curriculum (Hunt, McDonnell, and Crockett Citation2012; Janney and Snell Citation2006), highlighting the significance of collaboration in teacher practices.

Additionally, research underscores the unproven efficacy of individualised educational planning in terms of making a difference to student learning outcomes (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010: Riddell Citation2002; Tennant Citation2007), leading to the recommendation for future research to examine the relationship between quality of individualised educational planning and student performance (Blackwell and Rossetti Citation2014). In the absence of robust efficacy evidence, claims have been levied that individual plans function primarily as administrative tools rather than pedagogical resources for collaboration between teachers, students and parents to help meet the student’s educational and developmental needs (Andreasson, Asp-Onsjo, and Isaksson Citation2013; Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010). Furthermore, lack of teamwork and collaboration is reported to have a diminishing impact on the potential of the individual education plan to effect change (Bergin and Logan Citation2013; Riddell Citation2002; Stroggilos and Xanthacou Citation2006; Tennant Citation2007). Clearly, a study of teachers’ practices relating to individual education planning should attend to the collaborative aspects of practice and teachers’ preparedness for this.

Collaboration for inclusion

Collaboration can be defined as ‘an interactive process where a number of people with particular expertise come together as equals to generate an appropriate programme or process or find solutions to problems’ (NCSE Citation2006, X1). As an underpinning principle, collaboration is essential to development of the individual education plan and critical to how that plan unfolds in practice. Collaboration is integral to the inclusion of students with special educational needs, where it is advocated that ‘teachers work with specialists in order to find meaningful learning experiences for all children within the classroom community’ (Florian and Spratt Citation2013, 122). Promoting teacher collaboration with other adults, a framework for inclusive pedagogy in action informed by theoretical principles and evidence from teacher reflections and observations of student teachers’ practice highlights ‘working with and through other adults in ways that respect the dignity of learners as full members’ of the classroom community (Florian Citation2014, 291). For inclusion of students with special healthcare needs who require medical professional nursing care and students with severe disabilities in relation to for example, communication and language or motor development who require support from a speech and language therapist or occupational therapist, respectively, inter-professional collaboration among nurses, therapists and teachers is critical in promoting appropriate developmental and academic progress (Aruda, Kelly, and Newinsky Citation2011; Pufpaff et al. Citation2015).

Endorsing teacher collaboration, research indicates that effective collaboration has a number of significant benefits. Firstly, collaboration among teachers contributes to successful implementation of innovative, student-centred and collaborative learning methods (Dochy et al. Citation2003; Meirink, Meijer, and Verloop Citation2007; Slavit et al. Citation2011). Teachers involved in collaborative professional learning report using more innovative pedagogies (OECD Citation2013), improved teacher morale (Johnson Citation2003), and improved teacher motivation (Wigglesworth Citation2011), and display greater job satisfaction and self-efficacy (European Commission Citation2013). In a mixed methods study of the impact of peer collaboration on teachers’ practical knowledge, teachers who were jointly involved in collaborating on a teaching plan in the domain of statistics and subsequent implementation were enabled to reflect on their knowledge and skills while extending their practical knowledge (Witterholt, Goedhart, and Suhre Citation2016). In a comparative exploration of school context on professional learning, it was found that collaborative working among colleagues at increasingly expansive levels was a ‘tangible way’ of supporting teacher professional learning (Attard Tona and Shanks Citation2017, 105). Furthermore, research highlights the benefits of teacher collaboration for students in terms of improved understanding and performance (Egodawatte, McDougall, and Stoilescu Citation2011; Goddard, Goddard, and Tschannen-Moran Citation2005; Westheimer Citation2008; Wigglesworth Citation2011). Specifically related to inclusion of students with special educational needs, a small-scale exploration of teachers’ understanding and practices of inclusion revealed that increased complementariness of class teacher and special education teacher roles was linked with more coherence in teaching-learning experiences, facilitating the intentional learning of their students (Ní Bhroin Citation2017). Despite such favourable outcomes for students and their teachers and desirability in terms of balancing individual needs with general curriculum access, low levels of teacher collaboration relating to the individual education plan process have remained a persistent cause for concern (Ekstam, Linnanmäki, and Pirjo Citation2015; Morgan and Rhode Citation1983; Ní Bhroin Citation2017; Riddell Citation2002; Stroggilos and Xanthacou Citation2006; Tennant Citation2007).

Constraints to collaboration cited by teachers include inadequate professional preparation, mismatched personalities or pedagogical philosophies, a lack of dedicated time (Austin Citation2001; Meirink et al. Citation2010; Takala and Uusitalo-Malmivaara Citation2012; Welch Citation2000; Wischnowski, Salmon, and Eaton Citation2004), and the pressure of accountability and standardisation (Somech Citation2008; Westheimer Citation2008). An additional constraint with potential to impact on teacher learning from collaborative activity has been identified by Sjoer and Meirink (Citation2016, 120) as ‘safe talk’, manifest by the teachers in their research who failed to ask the challenging questions of their colleagues that would have required ‘taking a critical look at each other’s work.’ Safe styles of encouragement (Levine and Marcus Citation2010; McCotter Citation2001) mitigate against the ‘deep-level collaboration’ required to ‘touch’ teachers’ underlying beliefs (Vangrieken et al. Citation2015, 27) and to promote teacher learning. This is further evinced in Fullan’s (Citation2017) call for enhancing specificity in collaboration as a means of enhancing student outcomes. Focusing specifically on inter-professional collaboration where collaboration was regarded as important but not always feasible, evidence supports the call for improved pre-service preparation and professional development for professions involved (Pufpaff et al. Citation2015) and for ‘increased understanding of each other’s roles, conjoint training opportunities, and information sharing’ (Taylor, Morgan, and Callow-Heusser Citation2016, 173).

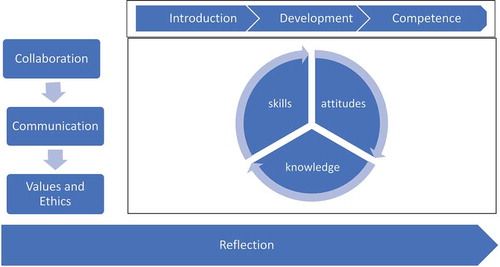

Of support here for teacher educators is the framework for interprofessional collaborative practice which is underpinned by the constructs of collaboration, communication, and values and ethics, cross-referenced with related competencies of knowledge, skills and attitudes (University of Toronto Citation2008). Designed for the inter-professional education curriculum at the University of Toronto, this is a three-stage curriculum framework of exposure, immersion and competence in preparing health professions’ students for collaborative practice. The framework specifies the core competencies of clinical placement for each of the three stages while highlighting continuous reflection across all three stages (for graphic of framework see Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel Citation2011, 31). Although concerned with healthcare professionals in clinical settings, there is potential in using the constructs of the framework to interrogate and interpret teachers’ collaborative practices in the individualised educational planning process with implications for professional learning. As such, the authors of this paper adapted the framework for their study in light of their review of previous research on professional learning and individualised educational planning and teacher collaboration for inclusion, to accommodate competencies relating to the development of collaborative practice in education, with particular focus on the student support plan. Maintaining the constructs of collaboration, communication, and values and ethics but reflecting the developmental aspect of learning, this framework assumes a learning continuum combining the interconnected phases of introduction, development and competence, with continuous reflection across these phases ().

Figure 2. Framework for exploring the development of collaborative practice for inclusion of students with support plans.

It was anticipated that analysis of the data would inform the detail relating to knowledge, skills and attitudes, populating these competencies in the framework, while allowing for review of the constructs.

Method

The study focused on teachers in one university who had completed a year-long Postgraduate Diploma in Special Educational Needs funded by the Department of Education and Skills (DES). Eligibility to attend the course was dependent on teachers working with students with SEN either in a mainstream or special school. Mainstream teachers on the course were in the role of a special education teacher (SET), special class and/or unit teacher in a primary or post-primary school. Course content placed significant emphasis on individual planning for students with special educational needs and on collaborative practice for their inclusion. The latter consisted of inter-professional collaboration, co-teaching and collaboration with parents and students. The aspects of individual planning and collaboration were assessed as part of the overall assessment of the course through written assignments and a practicum. Implementation and sustainability of new learning and practices have been highlighted as key areas of concern (King Citation2014, Citation2016) in relation to professional development and as such, it was hoped that this study would elucidate areas of strength and areas for development in relation to teacher education.

The study adopted a mixed methods design involving two phases of data collection. The first phase was quantitative, using a questionnaire to explore teachers’ perspectives of their knowledge, understanding and practices in relation to individual planning and collaboration for students with special educational needs, as gained from their postgraduate course. The total of 165 teachers who undertook the postgraduate course in the academic years 2010–2011, Citation2011–2012 and 2012–2013 were invited to participate in a postal survey. The response rate was 50.30% (n = 83).

Phase two was qualitative, designed to explore the possible embedding of new professional knowledge, practice and beliefs (Anderson Citation2005), and acknowledging the complexity of the social world (Coldwell and Simkins Citation2011), to explore how course participants were making sense of their learning about individual planning and collaborative practices for inclusion in their school contexts. An invite on the postal survey to self-select for phase two yielded an expression of interest from five special education teachers in five schools, four at primary level and one at post-primary level, all of whom became participants for phase two. Each special education teacher, in consultation with the school principal, choose one student for whom individual planning was warranted and whom the special education teacher participant was teaching. The five students along with a parent/guardian and other school staff involved in their education were also participants in phase two. Three researchers visited each school for the duration of one full day to carry out interviews, focus groups, observation of teachers’ practice and students’ learning in each student’s mainstream class and in the student’s support setting, and analysis of documents made available by the school ().

Table 1. Data collection for phase two.

Focus group members in each school comprised of a minimum of the student’s class teacher, special education teacher (SET), school principal and special needs assistant while for three schools, an additional teacher also involved in teaching the student joined the group. Each focus group lasted approximately one and a half hours and was attended by the three researchers, with one taking the lead on questioning while the remaining two took notes and one of these two provided a summary of key points towards the end of the focus group interview for verification by the participants and for clarification. Questions were designed to elicit the adults’ experiences, understanding and use of individual education plans which had intersection with collaboration, the postgraduate participant’s experiences of professional learning on the course, and perceptions of the impact of this professional learning on practice in the school particularly in relation to individual planning for students with support plans and collaboration for inclusion. The four individual and one paired interview with parents/guardians of the named student were carried out by one researcher in a room made available by the school. Each interview lasted for approximately one hour and followed a semi-structured schedule of questions designed to elicit participants’ experiences of being involved in the individual education planning process for their child. At the same time, individual interviews were carried out with each of the students in the additional support room, with two researchers present and one taking the lead. While questions were designed to encourage the students to talk about their experiences of their student support plans and their involvement in the process, an informal approach was adopted with warm up questions inviting students to share their interests, likes and dislikes. Interviews with the students from primary school lasted from 15 to 20 min and the interview with the post-primary student lasted 35 min. All focus groups and individual interviews were audio recorded, converted to a digital sound file, and transcribed in full for analysis purposes.

Observation of lessons in each student’s mainstream class and in the student’s support setting was undertaken by two researchers who were present for the same lessons. The purpose of observation was to capture the detail of teachers’ practices and students’ experiences of learning, in anticipation that such data would shed light on aspects of the individual planning process and collaboration for inclusion, and on the possible embedding of new learning in practice. Both researchers individually recorded digital field notes documenting their observations of practice, of teaching and of learning over approximately a three-hour period in each school. Following each school visit, the two sets of field notes were collated in preparation for analysis.

Relevant documents, some in digital format, made available by the school, were shared among the three researchers for reading. A digital template for preliminary documentary analysis designed in advance of school visits was used by each researcher, whereby in tandem with reading the documents, details relevant to specific headings were recorded on the template. Following the school visit, data were collated onto one template for further analysis.

Data analysis

Returned questionnaires were identified with a code for tracking purposes. Statistical analysis (136 variables) was undertaken using SPSS. NVivo 10 was used to store and code qualitative data using both inductive and deductive coding (Miles and Huberman Citation1994), with deductive coding relating to collaboration being informed by the conceptual framework (). Deductive codes applied to units of data reflecting or indicative of collaboration were abbreviations of the following: collaboration for planning; collaborative implementation; collaborative review; collaborative players: parents, teachers, students, special needs assistants, other professionals, other schools; communication: how, why, response/reaction; values: who, what, how; and, ethics. Inductive coding involved the iterative process of reading, re-reading and assigning codes to units of data within and across the data sets. In relation to collaboration, this resulted in the generation of the following codes: learning through collaboration; leadership and collaboration; collaboration: changes/developments; challenges of collaboration; and, collaboration: implications for professional learning. The overall coding process led to the generation and refinement of a coding scheme consisting of 125 codes. The codes contributed to the development of 14 categories across all data sources covering inclusion, assessment, profiling, planning, teaching approaches, review, collaboration, links, supports, change, evidence of the influence of professional learning, and student voice, outcomes and experience. Half of the interview transcripts, and of observational and documentary data were independently coded, achieving 93% agreement. As this exceeded the 65% to 75% agreement considered to be indicative of good reliability in qualitative research studies (Boyatzis Citation1998), this measure coupled with triangulation of data sources added to the overall trustworthiness of the process (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). Categories contributed to the emergence of four key themes: inclusion, collaboration, student experience and professional development. For this paper, the presentation of findings draws largely on the theme of collaboration while the examples reported from the qualitative data were consistently evident across the five schools.

Table 2. Teacher perceptions of the extent of improvement in knowledge, skills and practice as a result of CPD.

Findings

All teachers who participated in phase one were involved in planning, implementing and reviewing individual education plans, indicating that development and implementation of individualised educational planning was an established feature of their practice. Overall, teachers were positive regarding the extent to which their knowledge, skills and practice in relation to individual education plans had improved as a result of participating on the Postgraduate Diploma in Special Educational Needs course. Although knowledge and skills were rated separately from practice on the same indicators, teachers’ perceptions of the extent of improvement of knowledge and skills were almost equivalent to their perceptions of the extent of improvement in practice, as evident in the ranking of indicators in .

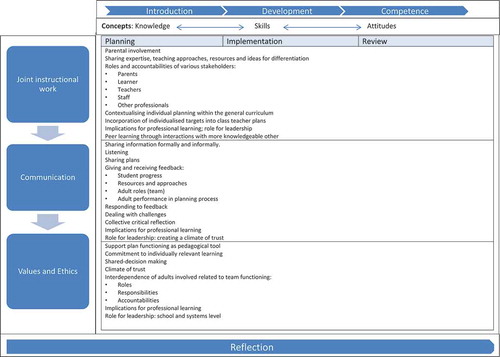

While the extent of improvement reported by teachers on indicators relating to assessment, planning and teaching to address specific learning needs is encouraging, this is less so on critical elements of the individual education plan process concerned with collaboration, coordination and review. Findings on collaboration in the individual education plan process highlighted the necessity for the inclusion of three modifications to the framework for interprofessional collaborative practice (University of Torronto Citation2008). These modifications reflect key stages of the individual education plan process and include planning, implementation and review. Findings related to these stages and challenges identified by teachers will now be explored.

Collaboration in the individual education plan process: planning

Analysis of findings revealed that collaboration in the preparation phase of the IEP process was strong. Survey data revealed that for the majority of teachers (92.6%; n = 75), it was the practice to hold IEP meetings. Regarding frequency, once a year was most common (n = 36), while for almost one quarter of teachers (n = 20), IEP meetings were held once a term. Parents (reported by 98% of teachers), class teachers (reported by 90% of teachers) and special education teachers (reported by 72% of teachers) were most likely to attend the IEP meeting. While meetings facilitated collaborative information sharing, the responsibility for writing the IEP was predominantly undertaken by the special education teacher (reported by 72.3% of teachers). Among class teachers (36.1%; n = 30) reported as writing the IEP, 26 of these were class teachers in a special school or a special class in a mainstream school and were therefore more likely to undertake this role, while class teachers in post-primary schools typically wrote sections relevant to their subject areas. In terms of sharing the programme generated as a result of the collaborative meeting, of those who received a copy of the student’s IEP, the student’s teachers were the most likely (reported by 86.7% of teachers) followed by their parents (reported by 78.3% of teachers). Less likely to receive a copy was the school principal (reported by 45.8% of teachers) and special needs assistant (SNA) (reported by 24.1% of teachers) while one-fifth of teachers reported that it was practice to provide other professionals with a copy of the IEP.

Analysis of qualitative data further revealed that collaboration for preparation of the IEP was welcomed by the teachers as a potential source of information for contributing to the plan. Typical of the views expressed by teachers across the five focus groups is this comment from a special education teacher.

The parents are very informative like, we do bring them in and they would be very good in terms of helping you plan towards what the child needs, and the class teacher, because the class teacher really knows how that child is performing in comparison to their peers, and are they living up to their potential. (Focus Group 2: SET1)

All of the parents appreciated their involvement in contributing to the plan, not alone because they felt their views were valued and given weight but their concerns were eased. This affective dimension is typified in the following parent comment.

It gives me rest of mind … to know that the school understands, so it’s not as if you feel your child will be a failure or what will happen to him; you have enough people that are on board telling you don’t worry, you know we’re going to work this thing, and it’s going to come out positive. It’s a very good feeling for me. (Parent Interview 5)

Collaboration in the individual education plan process: implementation

Implementation of the IEP is inextricably linked with who addresses the student’s learning targets and how, in terms of teaching approaches, learning activities and resources to deliver on that plan. Analysis revealed that collaboration during implementation was less than favourable. Based on survey data, practices relating to the student’s IEP targets reported by teachers indicate that these were typically addressed by appropriate teaching methods and strategies (84.6%; n = 66) and made known to all involved in the student’s education (75.3%; n = 61) but less typically incorporated in the class teacher’s plans (43.2%; n = 35). However, analysis of qualitative data revealed that this low level of incorporation of individual learning targets in the class teacher’s plans was even less so for the five schools that were involved in phase two of the study. By way of illustration, documentary analysis revealed strong links between student learning targets indicated on the IEP and the short-term plans devised by all of the special education teachers, as exemplified in (DA: SET4).

Table 3. Student learning targets on IEP and SET short-term plans.

Contrastingly, class teacher plans did not specifically reference individualised learning targets nor did they address the substance of those targets in terms of, for example, identifying associated concepts and skills. The only reference to any form of individualised learning in class teacher plans and evident across the plans of all class teachers was a generic statement under the heading of differentiation as follows: Differentiation by learning objectives, teaching style, support, resource, task, outcome, grouping, pace (DA: CT1). As explained by one class teacher:

I wouldn’t really be writing down my differentiation within my, my kind of planning, like fortnightly plans would be more content led. I wouldn’t really be writing down times when I would be differentiating or not, that would be an innate thing that I would be doing within the classroom. (Focus Group 2: CT)

Across the five schools, this pattern of low teacher collaboration during implementation was repeated in the analysis of observational data which revealed that special education teachers addressed individualised learning targets with very deliberate and strategic teaching and learning activities. Teaching and learning experiences undertaken by the special education teachers with their students were drawn from the curriculum but focused upon precisely because they related directly to the individual learning needs of students. By contrast, class teachers were aware of the student’s priority learning goals but did not strategically address individualised learning targets in their teaching. However, where students were evidenced experiencing difficulty with learning or struggling with understanding, generally, class teachers addressed this during the lesson, in situ, and in the moment or as noted by one: ‘on the hoof’ (Focus Group 1: CT). This is illustrated in the following extract relating to a lesson on coordinate geometry with children from sixth class (ages 11 to 13 years) who, following whole class teaching, were individually required to draw an ‘8 by 8 grid’, to plot two points on the grid and join with a line.

One student is confused and asks teacher ‘what does it mean by plotting?’ Teacher calls out ‘booster table’ pointing to a desk near top, centre of classroom and asks if ‘anybody else wants to come up and I’ll show you’. Eight children leave their seats and move up to circle the booster table where teacher demonstrates the process of plotting required by of the task. David (student with IEP) goes up to observe with the others. As teacher demonstrates the process, she raises right hand with ruler and says ‘I will always use my ruler to plot my graph’ which she encourages children to chorus after her. Then, for each step, she questions on how many squares across x axis and y axis, on numbering of squares, and on using axis and number for plotting to which students, including David, have opportunity to respond, and in response to her question ‘what do you have to remember?’ they reply: ‘go across and then up.’ Demonstration satisfies students who return to their places and work independently as teacher circulates to guide and monitor. (Field notes: CT1)

Responding to the immediate learning needs of the moment, such activity enabled curriculum access for students.

While efforts to enable curriculum access are to be welcomed, observational data relating to class teachers in their mainstream classes across the five schools also revealed missed opportunities for addressing individualised learning within the general curriculum. This was evident, for example, in an art lesson with fifth class (ages 10 to 12 years) on ‘Designing our dream bedroom’; children, who had the choice of working in groups or individually, had to paint and paper a shoebox and then locate materials from an assortment of containers for assembling in the shoebox to include key features which had been identified through class discussion and recorded on the interactive whiteboard earlier in the lesson. During this activity, the class teacher circulated to monitor, guide and encourage children’s efforts. On the three occasions that the teacher approached Evan (student with IEP whose learning targets are recorded in ), it was to assist with assembling the materials, for example, covering cardboard with paper, cutting tape and taping pieces of cardboard together while teacher interactions related to task completion: ‘Right, you hold it there. I must check in the press if we have a bit more tape’ and ‘Are you going to do your actual room or a room that you’d love to have Evan?’ (Field notes: CT4). However, this one-to-one context could also have been used to ask the student to recall what he had done so far and encourage him to explain what he was intending to do using the word ‘because’ as a means of addressing his individualised target relating to formulating sentences using past tense verbs and conjunctions. These missed opportunities lend substance to the wish expressed by one special education teacher ‘to get the scales transferred because often’ she ‘felt’ she ‘would be doing it in isolation in a resource room, but that wasn’t being transferred into the classroom and that’s another big thing’ (Focus Group3: SET1).

Collaboration in the individual education plan process: review

Regarding review, analysis of survey data indicated the majority of teachers (74.4%; n = 61) reporting that it was the practice in their schools to use the IEP to measure learning outcomes for their students although almost one quarter were unsure (23.2%; n = 19). Additionally, for close to one quarter of teachers (n = 20) who reported holding IEP meetings once a term, this presented an opportunity to collaboratively review progress relating to the IEP. Analysis of qualitative data revealed that review was a continuous process, not necessarily confined to the formality of a meeting, typified in the following comment from a special education teacher: ‘We’re constantly unofficially reviewing it, and that’s very important as well, in order to be able to monitor how things are going, what’s working well, and what isn’t’ (Focus Group 4: SET1). Parental involvement in the informal and formal review was welcomed by teachers across the five schools:

The father is often here so it’s very handy if we need to communicate … we had a review there in January and his parents came in … and his parents are very happy to give us their feedback and to get any feedback from us. (Focus Group 2: SET2)

However, on further analysis, review of progress specifically related to achievement of individualised learning targets was undertaken by the special education teachers where information was then shared with relevant others. Class teachers could draw on formal and informal assessment information to report on student progress but this information did not necessarily relate to the student’s learning targets. Additionally, the review process appeared to focus predominantly on student progress and experience without reference to reviewing the collaborative activity of teachers involved in the individual education plan process: ‘at the end of the year it’s just nice to regroup and reflect and see how far this child has come’ (Focus Group 1: CT1).

Challenges

Teachers welcomed the opportunities for professional learning from knowledge and experience sharing afforded by collaboration. Qualitative analysis revealed teachers’ appreciation of learning from their teacher colleagues in ways that enhanced their capacity to plan for and support individually relevant learning, and to facilitate inclusion of their students in their teaching: ‘ … helpful, yes, because it would focus me on the child’s needs, and how I can use differentiation within the classroom to make sure that he’s included, make sure that he’s getting everything that he possibly can from the lesson’ (Focus Group 2: CT1). Additionally, the expertise of other professionals was acknowledged in so far as inter-professional collaboration allowed for sharing of ideas and resources: ‘The OT (occupational therapist) from Lakeview … she showed us the Handwriting without Tears programme and just lots and bits of advice and guidance so that was great to get it, any bit we can get we take’ (Focus Group 3: SET1). Inter-professional collaboration was also welcomed for providing an expert ‘other’ perspective.

Outside professionals coming in, it’s really helpful. Like the speech and language therapist came in who had really good ideas and a really good focus … I think we are so busy with, kind of, the cold face, whereas someone like the speech and language therapist is working in more of a therapeutic setting and they have that little bit of distance, and they are experts as well. It’s good to get another perspective. (Focus Group 2: CT1).

Challenges to collaboration that have long been documented were revealed in the focus group data pertaining to the five schools and were related to insufficient time, shortage of other professionals, and communication. Dedicated time for collaboration to plan and review was persistently raised as an issue across the five schools. Referring to the process of sharing and following up on learning targets for individual students, a subject teacher in the post-primary school noted: ‘you’d like to keep on top of it obviously, but there’s a hundred and one things to do’ (Focus Group 5: SubT1). The view that ‘schools are very busy and there’s an awful lot happening’ (Focus Group 1: SET1) was shared by teachers. Lamenting the short supply of other professionals and wait time that children endured to access professional services beyond the school, teachers’ views were captured in the comment that ‘we don’t have enough of them … the children in the unit should be involved with speech and language therapists and occupational therapists from the beginning, you know, and not on waiting lists like that’ (Focus Group 3: SET2). Although not articulated by teachers as a challenge to collaboration, issues emerged from the analysis of focus group data across the schools relating to communication of feedback with potential to impact on teacher learning. This is captured in a special education teacher’s response to a class teacher in her school expressing the view that ‘support teachers should have knowledge of the class plans’ in advance so they can ‘pre-teach … give the child a head start … prepare certain resources and simplify the language’ (Focus Group 4: CTI).

I’m glad you said that Tamara, because it’s one thing, even with the training, that makes it difficult as a resource teacher, in my experience, to talk to a class teacher in a way they don’t feel like, I mean I couldn’t imagine going to a class teacher, and asking them may I see your plans? It would make my job easier, but I feel they would be on the defensive … training needs to be for the whole staff, so that everybody understands that if you mention that you’re using a particular programme to help to intervene, an intervention with the child or whatever, that the class teacher isn’t thinking you’re telling them what to do you know, I’ve had that experience and it’s not pleasant. (Focus Group 4: SET1)

Discussion and conclusion

Developing and implementing the student support plan is an established feature of practice among the 83 teachers who responded to the survey. Teacher reports of strong improvement in their use of assessment to identify student strengths and needs are encouraging as the quality of assessment data used to identify individual needs is a contributory factor to quality of the plan (Cooper Citation1996). Additionally and contrary to previous reports (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010; Riddell Citation2002; Tennant Citation2007), the majority of teachers engage in the practice of using individual plans to measure learning outcomes for students with SEN. While this could be higher, it indicates teachers’ establishment of connections between assessment data, learning targets and the instructional programme, again supporting the quality of the plan (Blackwell and Rossetti Citation2014; Cooper Citation1996). As such, student support plans are functioning as pedagogical tools for the teachers and their learners, and are an encouraging endorsement of the professional learning programme experienced by the teachers in the study. However, the widely documented challenges relating to collaboration in individualised educational planning (Riddell Citation2002; Tennant Citation2007) persist. While collaborative practices supported development of the student support plan, they were less in evidence during implementation and review. Arising from the findings about collaboration, the conceptual framework for the study has been developed to include the three stages of planning, implementation and review. It is hoped that this framework would support teacher educators to enhance professional learning relating to collaboration for the inclusion of students with support plans ().

Figure 3. A framework for developing collaboration for the inclusion of students with support plans.

Collaboration: joint instructional work

Regarding collaborative involvement in development of the IEP, parental attendance at IEP meetings is high, and furnishing parents and class teachers with a copy of the IEP appears common practice. Teachers’ satisfaction with the opportunities for information sharing in relation to individual students and professional learning about teaching approaches, programmes and differentiating to support inclusion of the students afforded by collaboration with colleagues, parents and other professionals resonates to some extent with research highlighting the benefits of effective collaboration for teachers and their students (Meirink et al. Citation2007; Slavit et al. Citation2011; Westheimer Citation2008; Wigglesworth Citation2011; Witterholt, Goedhart, and Suhre Citation2016).

While collaborative involvement in the preparation phase of the IEP is strong, collaboration during implementation and review phases presents a less favourable picture. As the IEP is not a legal requirement in the RoI, mandatory obligations cannot explain this weaker perception of the importance of collaboration during implementation and review. As such, teacher perceptions and reported practices relating to collaboration and coordination of the IEP process, and the reported and observed the low level of incorporation of individualised targets in class teacher’s plans highlight a need for teacher educators to focus on developing collaborative skills of teachers for implementation. Collaborative skills contribute to contextualisation of the individual plan within the general curriculum (Hunt, McDonnell, and Crockett Citation2012; Janney and Snell Citation2006). Such contextualisation is crucial to quality and pedagogical value of the IEP (Kwon, Elicker, and Kontos Citation2011; Kurth and Mastergeorgre Citation2010; Ruble et al. Citation2010). The lesson for teacher educators is to focus on how collaborative practice can support this contextualisation. The clarion call for teachers to work with and through other adults to secure meaningful learning experiences for all children in the classroom community (Florian Citation2014; Florian and Spratt Citation2013) remains upheld. This highlights the importance of the roles, responsibilities and accountability of each member involved in the collaborative team, and of how these roles and responsibilities are understood and their interdependence appreciated by all team members. Development of the collaborative skills that will support class teachers and special education teachers to interweave individualised targets with general curriculum in planning and teaching relates to an appreciation of the interdependence of these roles and has implications for teacher education. Accepting collaboration as an umbrella term for the framework, the first construct of joint instructional work reflects the knowledge and skills associated with collaborative activities for including students with support plans.

Communication

The construct of communication in collaborative practices relating to the IEP process was evident in teachers’ accounts of sharing information with others formally at planning and review meetings and informally on an ongoing basis. It was further evident in teachers’ acknowledgement of the benefits of information sharing to their understanding and practice. Such benefits reflect previous reports of the positive impact of peer collaboration on teachers’ professional learning (Attard Tona and Shanks Citation2017; Witterholt, Goedhart, and Suhre Citation2016). However, teachers’ listening and contributing to information appeared to focus predominantly on student progress and on ideas, resources, programmes and teaching approaches. The communicative competencies of providing feedback to others and responding to feedback from others where the focus was on adult roles, performance and activity in relation to the IEP process were not so evident in teachers’ accounts or observations of practice. This highlights the need for teacher educators to focus on developing these communicative competencies with teachers. Indeed, communication of feedback with potential to impact on teacher learning emerged as a challenge to collaboration, with concerns about misinterpretation and a call for ‘training’ for the whole staff to address this. The possibilities for peer learning (Jackson and Bruegmann Citation2009) through interactions with a more knowledgeable other (Butler et al. Citation2004) whether that be class teacher or special education teacher, were underutilised within the schools, again highlighting a potential area of focus for teacher educators. Reluctance to challenge colleagues to take ‘a critical look at each other’s work’ (Sjoer and Meirink Citation2016, 120) in favour of safe styles of encouragement resonates with previous research (Levine and Marcus Citation2010; McCotter Citation2001). The development of communicative competencies among teachers relating to collective critical reflection on the practices of all involved, with potential to support ‘deep-level collaboration’ (Vangrieken et al. Citation2015, 27), is an area that requires attention in teacher education that prepares teachers to collaborate for inclusion of students with support plans and in schools where principals are creating collaborative cultures based on trust and respect (King Citation2011).

Values and ethics

Consistent with lack of dedicated time and limited resources previously reported as constraining collaboration (Austin Citation2001; Takala and Uusitalo-Malmivaara Citation2012; Wischnowski, Salmon, and Eaton Citation2004), insufficient time and lack of access to professional services beyond the school emerged as challenges to collaborating among the adults in this study. These challenges reflect the construct of values and ethics at a systemic level, highlighting a role for leadership at school and systems’ levels (King Citation2014) for their redress. The challenges also have implications for teacher educators involved in education of school leaders, in terms of embedding reflection on values and beliefs (Anderson Citation2005) related to collaborative practices. Acknowledging the influence of school context on collaborative practices, research highlights the pivotal role of leadership in fostering collaboration and creating collaborative cultures (King Citation2011, Citation2014).

Within school level, teacher competencies on the collaboration construct of values and ethics were evident in the finding that the IEP was functioning as a pedagogical tool, facilitating student participation and learning, reflecting a commitment among teachers to securing individually relevant learning for their students (Ferguson Citation2008; Griffin and Shevlin Citation2007; Loreman, Deppeler, and Harvey Citation2010). Additionally, preparation, implementation and review of the IEP were based on shared decision-making, evincing regard for democratic principles (Ainscow and Sandhill Citation2010). While findings indicate an expressed appreciation for the contribution of all adults involved in the individual education plan process, in so far as responsibility for addressing individualised learning targets resides primarily with the special education teacher, this may reflect an underappreciation of the interdependence of those adults involved. More than ‘conjoint training opportunities’ (Taylor, Morgan, and Callow-Heusser Citation2016), in terms of teacher education to enhance competencies in collaborative practice for inclusion, increasing teacher awareness of the interdependence of all involved in the process requires attending to roles, responsibilities and accountabilities as they relate to team functioning, to optimise learning experiences for the students while maximising student outcomes.

The challenges to effective teamwork evident in this study may highlight a disproportionate impact of the IEP requirement on the implementation of collaboration. This raises a policy issue in terms of the possible reframing of individual educational planning in the context of foregrounding the collaborative activity necessary to include students with support plans. A policy emphasising collaborative student support plans could acknowledge the collaboration competencies required of those charged with delivering on the plans. While teachers acknowledged the challenges to collaborative practice, beyond recommending ‘training … for the whole staff’, there was no other discussion from participants themselves for the improvement of teacher education for collaborative practice. However, this study has implications for teacher educators to support an increased focus on the development of particular collaboration competencies relating to joint instructional work, communication, and values and ethics. Such professional learning opportunities would enable teachers to develop shared team values and guide collaborative decision-making and action for increasingly effective ways of working with and through others in supporting inclusion. To this end, the framework presented in this paper, with its multi-faceted description of collaboration, has potential to highlight areas of focus not alone for teacher education but also for development and review of collaborative practices for inclusion in schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Órla Ní Bhroin

Órla Ní Bhroin is an associate professor in the School of Inclusive and Special Education, Dublin City University (DCU). Órla has worked in teacher education across the continuum of professional development for the past seventeen years and currently coordinates special and inclusive education on the BEd programme and leads on the Special and Inclusive Education option of the MEd programme.

Fiona King

Fiona King is an assistant professor in the Institute of Education, Dublin City University (DCU). Fiona spent 25 years teaching in a variety of contexts and currently works in the School of Inclusive and Special Education in DCU where she specialises in: inclusive pedagogies, social justice leadership, teacher professional learning, teacher leadership, and change. Fiona currently leads on the EdD programme for inclusive and special education. She is a member of the IPDA (International Professional Development Association) international committee and Chair of IPDA Ireland along with being an associate editor of the Q1 journal Professional Development in Education.

References

- Ainscow, M., and A. Sandhill. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Education Systems: The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (4): 401–416.

- Anderson, B. 2005. “The Value of Mixed-Method Longitudinal Panel Studies in ICT Research. Transitions in and Out of ‘ICT Poverty’ as a Case in Point.” Information, Communication & Society 8 (3): 343–367. doi:10.1080/13691180500259160.

- Andreasson, I., L. Asp-Onsjo, and J. Isaksson. 2013. “Lesson Learned from Research on Individual Educational Plans in Sweden: Obstacles, Opportunities and Future Challenges.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (4): 413–426. doi:10.1080/08856257.2013.812405.

- Artiles, A. J., E. B. Kozleski, and F. R. Waitoller. 2011. Inclusive Education: Examining Equity on Five Continents. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Aruda, M. M., M. Kelly, and K. Newinsky. 2011. “Unmet Needs of Children with Special Healthcare Needs in a Specialised Day School Setting.” The Journal of School Nursing 27 (3): 209–218. doi:10.1177/1059840510391670.

- Attard Tona, M., and R. Shanks. 2017. “The Importance of Environment for Teacher Professional Learning in Malta and Scotland.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1251899.

- Austin, V. L. 2001. “Teachers’ Beliefs about Co-teaching.” Remedial and Special Education 22 (4): 245–255. doi:10.1177/074193250102200408.

- Barnard-Brak, L., and D. Lechtenberger. 2010. “Student IEP Participation and Academic Achievement.” Remedial and Special Education 31 (5): 343–349. doi:10.1177/0741932509338382.

- Bergin, E., and A. Logan. 2013. “An Individual Education Plan for Pupils with Special Educational Needs: How Inclusive Is the Process for the Pupil?” REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland 26 (2): 79–91.

- Blackwell, W. H., and Z. S. Rossetti. 2014. “The Development of Individualized Education Programmes: Where Have We Been and Where Should We Go Now?” Sage Open 1–15. doi:10.1177/2158244014530411.

- Borko, H. 2004. “Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain.” Educational Researcher 33 (8): 3–15. doi:10.3102/0013189X033008003.

- Boyatzis, R. E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Research: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. London: Sage Publications.

- Butler, D. L., H. Lauscher Novak, S. Jarvis-Selinger, and B. Beckingham. 2004. “Collaboration and Self-Regulation in Teachers’ Professional Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (5): 435–455. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.04.003.

- Clarke, D., and H. Hollingsworth. 2002. “Elaborating a Model of Teacher Professional Growth.” Teaching and Teacher Education 18 (8): 947–967. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7.

- Clarke, S. G. 2000. “The IEP Process as a Tool for Collaboration.” Teaching Exceptional Children 33 (2): 56–66. doi:10.1177/004005990003300208.

- Coldwell, M., and T. Simkins. 2011. “Level Models of Continuing Professional Development Evaluation: A Grounded Review and Critique.” Professional Development in Education 37 (1): 143–157. doi:10.1080/19415257.2010.495497.

- Cooper, P. 1996. “Are Individual Education Plans a Waste of Paper?” British Journal of Special Education 23 (3): 115–119. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8578.1996.tb00960.x.

- Cordingley, P., M. Bell, B. Rundell, D. Evans, and A. Curtis. 2003. The Impact of Collaborative CPD on Classroom Teaching and Learning: How Does Collaborative Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers of the 5–16 Age Range Affect Teaching and Learning? ( Review). London: EPPI-Centre. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/CPD_rv1.pdf?ver=2006-02-27-231004-323

- Darling-Hammond, L., and M. W. McLaughlin. 2011. “Policies that Support Professional Development in an Era of Reform.” Phi Delta Kappan 92 (6): 81–92. doi:10.1177/003172171109200622.

- DES (Department of Education and Skills). 2017. Circular 0013/2017: Circular to the Management Authority of All Mainstream Primary Schools: Special Education Teaching Allocation. Dublin: Author.

- Desimone, L. M. 2009. “Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures.” Educational Researcher 38 (3): 181–199. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140.

- DfES (Department for Education and Skills). 2001. Special Needs Code of Practice. London: DfES.

- Dochy, F., M. Segers, P. Van den Bossche, and D. Gijbels. 2003. “Effects of Problem-Based Learning: A Meta-Analysis.” Learning and Instruction 13 (5): 533–568. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(02)0025-7.

- Douglas, G., J. Travers, M. McLinden, C. Roberstson, E. Smith, N. Macnab, S. Powers, et al. 2012. “Measuring Educational engagement, Progress and Outcomes for Children with Special Educational Needs: A Review.” National Council for Special Education, Research Report No. 11. Trim: National Council for Special Education.

- Egodawatte, G., D. E. McDougall, and D. Stoilescu. 2011. “The Effects of Teacher Collaboration in Grade 9 Mathematics.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 10 (3): 189–209. doi:10.1007/s10671-011-9104-y.

- Ekstam, U., K. Linnanmäki, and A. Pirjo. 2015. “Educational Support for Low-Performing Students in Mathematics: The Three-Tier Support Model in Finnish Lower Secondary Schools.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 30 (1): 75–92. doi:10.10.80/08856257.2014.

- Erickson, J., and C. A. Davis. 2015. “Providing Appropriate Individualised Instruction and Access to the General Education Curriculum for Learners with Low-Incidence Disabilities.” In Including Learners with Low-Incidence Disabilities (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education. 5 vols. edited by E. West, 137–158. West Yorkshire: Emerald Group Publishing.

- European Commission. 2013. Shaping Career-Long Perspectives on Teaching: A Guide on Policies to Improve Initial Teacher Education. Brussels: Author.

- Ferguson, D. L. 2008. “International Trends in Inclusive Education: The Continuing Challenge to Teach Each and Every One.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 23 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1080/08856250801946236.

- Fitzgerald, J., and J. Radford. 2017. “The SENCO Role in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland: Victims or Agents of Change?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (3): 452–466. doi:10.1080/08856257.2017.1295639.

- Florian, L. 2014. “What Counts as Evidence of Inclusive Education?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 286–294. doi:10.1080/08856257.2014.933551.

- Florian, L., and J. Spratt. 2013. “Enacting Inclusion: A Framework for Interrogating Inclusive Practice.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1080/08856257.2013.778111.

- Forlin, C. 2001. “The Role of the Support Teacher in Australia.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 16 (2): 121–131. doi:10.1080/08856250110040703.

- Fraser, D. 2005. Professional Learning in Effective Schools: The Seven Principles of Highly Effective Professional Learning. ( No. 1). Melbourne, Australia: ictorian Institute of Teaching. Accessed 20 January 2018. http://www.education.vic.gov.au/documents/school/teachers/profdev/proflearningeffectivesch.pdf

- Fuchs, L. S., and S. Vaughn. 2012. “Responsiveness-to-Intervention: A Decade Later.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 45 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1177/002219412442150.

- Fullan, M. 2017. “Making Progress Possible: a Conversation with Michael Fullan.” Educational Leadership 74: 8–14.

- Goddard, Y., R. D. Goddard, and M. Tschannen-Moran. 2005. “A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation of Teacher Collaboration for School Improvement and Student Achievement in Public Elementary Schools.” Teachers College Record 109 (4): 877–896.

- Government of Ireland. 2004. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Griffin, S., and M. Shevlin. 2007. Responding to Special Educational Needs: An Irish Perspective. Dublin: Gill & McMillan.

- Guskey, T. R. 2009. “Closing the Knowledge Gap on Effective Professional Development.” Educational Horizon 87 (4): 224–233. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ849021.pdf

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Hoban, G. 1996. “A Professional Development Model Based on Interrelated Principles of Teacher Learning.” Unpublished PhD, University of British Columbia, Canada. Accessed 20 January 2018. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0054954

- Hunt, P., J. McDonnell, and M. A. Crockett. 2012. “Reconciling an Ecological Curricular Framework Focusing on Quality of Life Outcomes with the Development and Instruction of Standards-Based Academic Goals.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 37 (3): 139–152. doi:10.2511/027494812804153471.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. 2011. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Jackson, C. K., and E. Bruegmann. 2009. “Teaching Students and Teaching Each Other: The Importance of Peer Learning for Teachers.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (4). doi:10.3386/w15202.

- Janney, R. E., and M. E. Snell. 2006. “Modifying Schoolwork in Inclusive Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 45 (3): 215–223. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4503_3.

- Johnson, B. 2003. “Teacher Collaboration: Good for Some, Not so Good for Others.” Educational Studies 29 (4): 337–350. doi:10.1080/0305569032000159651.

- Kennedy, A. 2014. “Understanding Continuing Professional Development: The Need for Theory to Impact on Policy and Practice.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 688–697. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.955122.

- King, F. 2011. “The Role of Leadership in Developing and Sustaining Teachers’ Professional Learning.” Management in Education 25 (4): 149–155. doi:10.1177/0892020611409791.

- King, F. 2014. “Evaluating the Impact of Teacher Professional Development: An Evidence- Based Framework.” Professional Development in Education 40 (1): 89–111. doi:10.1080/19415257.2013.823099.

- King, F. 2016. “Teacher Professional Development to Support Teacher Professional Learning: Systemic Factors from Irish Case Studies.” Teacher Development: An International Journal for Teacher Professional Development 20 (4): 574–594. doi:10.1080/13664530.2016.1161661.

- King, F., Ó. Ní Bhroin, and A. Prunty. 2018. “Professional Learning and the Individual Education Plan Process: Implications for Teacher Educators.” Professional Development in Education 44 (5): 607–621. doi:10.1080/19415257.2017.1398180.

- Kurth, J., and A. M. Mastergeorgre. 2010. “Individual Education Plan Goals and Services for Adolescents with Autism: Impact of Age and Educational Setting.” The Journal of Special Education 44 (3): 144–160. doi:10.1177/0022466908329825.

- Kwon, K., J. Elicker, and S. Kontos. 2011. “Social IEP Objectives, Teacher Talk, and Peer Interaction in Inclusive and Segregated Preschool Settings.” Early Childhood Education Journal 39 (4): 267–277. doi:10.1007/s10643-011-0469-6.

- Levin, T., and Y. Nevo. 2009. “Exploring Teachers’ Views on Learning and Teaching in the Context of a Trans-Disciplinary Curriculum.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 44 (4): 439–465. doi:10.1080/00220270802210453.

- Levine, T. H., and A. S. Marcus. 2010. “How the Structure and Focus of Teachers’ Collaborative Activities Facilitate and Constrain Teacher Learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 389–398. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.001.

- Loreman, T., C. Forlin, and U. Sharma. 2014. “Measuring Indicators of Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” In Measuring Inclusive Education: International Perspectives on Inclusive Education. 3 vols. edited by C. Forlin and T. Loreman, 165–187. West Yorkshire: Emerald Group Publishing. doi: 10.1108/S1479-363620140000003024.

- Loreman, T., J. Deppeler, and D. Harvey. 2010. Inclusive Education: Supporting Diversity in the Classroom. London: Routledge.

- McCotter, S. S. 2001. “Collaborative Groups as Professional Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 17 (6): 685–704. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00024-5.

- Meirink, J. A., J. Imants, P. C. Meijir, and N. Verloop. 2010. “Teacher Learning and Collaboration in Innovative Teams.” Cambridge Journal of Education 40 (2): 161–181. doi:10.1080/0305764x2010.481256.

- Meirink, J. A., P. C. Meijer, and N. Verloop. 2007. “A Closer Look at Teachers’ Individual Learning in Collaborative Settings.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 13 (2): 145–164. doi:10.1080/13540600601152496.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Mitchell, D., M. Morton, and G. Hornby. 2010. Review of the Literature on Individual Education Plans. Report to the New Zealand Ministry of Education, Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Morgan, D. P., and G. Rhode. 1983. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards IEPs: A Two-Year Follow-Up.” Exceptional Children 5 (1): 64–67.

- National Council for Special Education. 2014. Delivery for Students with Special Educational Needs: A Better and More Equitable Way. Trim: Author.

- NCSE (National Council for Special Education). 2006. Guidelines on the Individual Education Plan Process. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- New Zealand Ministry of Education. 2004. The New Zealand Curriculum Framework. Wellington: Learning Media Limited.

- Ní Bhroin, Ó. 2017. Inclusion in Context: Policy, Practice and Pedagogy. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Ní Bhroin, Ó., F. King, and A. Prunty. 2016. “Teachers’ Knowledge and Practice Relating to the Individual Education Plan and Learning Outcomes for Pupils with Special Educational Needs.” REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland 29 (2): 78–90.

- O’Gorman, E., and S. Drudy. 2010. “Addressing the Professional Development Needs of Teachers Working in the Area of Special Education/Inclusion in Mainstream Schools in Ireland.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 10 (1): 157–167. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01161.x.

- OECD (Organisation for Co-operation and Development). 2013. Teaching and Learning International Survey: TALIS 2013. Paris: Author. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/TALIS%20Conceptual%20Framework_FINAL.pdf

- Pantic, N., and L. Florian. 2015. “Developing Teachers and Agents of Change and Social Justice.” Education Inquiry 6 (3): 333–351. doi:10.3402/edui.v6.27311.

- Prunty, A. 2011. “Implementation of Children’s Rights: What Is ‘In the Best Interests of the Child’ in Relation to the Individual Education Plan (IEP) Process for Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD).” Irish Educational Studies 30 (1): 23–44. doi:10.1080/03323315.2011.535974.

- Pufpaff, L. A., C. E. McIntosh, C. Thomas, M. Elam, and M. K. Irwin. 2015. “Meeting the Health Care Needs of Students with Severe Disabilities in the School Setting: Collaboration between School Nurses and Special Education Teachers.” Psychology in the Schools 52 (7): 683–701. doi:10.1002/pits.21849.

- Riddell, S. 2002. Policy and Practice in Special Education: Special Educational Needs. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

- Rose, R., and M. Shevlin. 2010. Count Me In: Ideas for Actively Engaging Students in Inclusive Classrooms. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Rose, R., M. Shevlin, E. Winter, and P. O’Raw. 2015. Project IRIS – Inclusive Research in Irish Schools. A Longitudinal Study of the Experiences of and Outcomes for Pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Irish Schools. Trim: National Council for Special Education (NCSE).

- Rose, R., M. Shevlin, E. Winter, P. O’Raw, and Y. Zhao. 2012. “Individual Education Plans in the Republic of Ireland: An Emerging System.” British Journal of Special Education 39 (3): 110–116. doi:10.1111/bjsp.2012.39.issue-3.

- Ruble, L., A. McGrew, J. Dalrymple, N. Lee, and A. Jung. 2010. “Examining the Quality of IEPs for Young Children with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40 (12): 1459–1470. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1003-1.