ABSTRACT

Field experiences aim at immersing student teachers in authentic work tasks and conditions of teachers. However, specific psychological needs of the teaching workforce are not considered when studying the fulfilment of student teachers’ psychological needs. This paper proposes a four-dimensional theoretical framework incorporating both basic and specific psychological needs. A diary study is presented, which measures the fulfilment of the hypothesised needs at five intervals during a ten-day field experience. The average fulfilment rates and development trends show differences among the four dimensions, suggesting the presence of lower- and higher-order needs. Significant correlations between need fulfilment and success indicators, such as learner satisfaction, learning gain, teacher self-efficacy and level of self-reflection, are also found. The results highlight the relevance of high rates of need fulfilment right from the start of the field experience.

1. Introduction

Teaching is a future-oriented and competence-based profession. It constantly sets new goals, poses new challenges and developmental tasks and hence demands continuing professional development of teachers (Alexander Citation2008; Reeve and Su Citation2014). Student teachers’ field experiences provide rich learning opportunities for developing competencies regarding present and future complex demands of teaching (Zeichner Citation2010). However, evidence suggests that these opportunities are not exhausted, partly due to the rather limited knowledge about the conditions that are beneficial for realising successful practical learning (Arnold, Gröschner, and Hascher Citation2014). According to Hascher (Citation2012), relevant antecedents for successful learning involve several environmental (e.g. mentoring, feedback) and individual factors (e.g. emotion, motivation). Although successful professional development is argued to be fundamentally dependent on motivation (Alexander Citation2008; Barcelos Citation2016; Richardson and Watt Citation2018), there are scarce insights on the motivational side of practical learning in field experiences. Motivation predicts the extent and the quality of cognitive engagement and thus contributes to the development of skills and competencies and subsequently, achievement (Blumenfeld, Kempler, and Krajcik Citation2006). Although motivation is commonly viewed as connected to a series of complicated cognitive processes, which to date cannot entirely be explained by theoretical approaches (Han and Yin Citation2016), theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence are present on beneficial conditions and the relevant antecedents of motivation. For example, the self-determination theory (SDT) proposes that goals and values are integrated into a person’s self, representing one’s identity and regulating one’s behaviour accordingly (Deci and Ryan Citation2000). The deeper these goals and values are integrated into the self, the more the identification and the regulation of behaviour become possible. Environmental factors can influence the integration of values and goals into the self. However, these processes are deemed dependent on basic psychological needs and their fulfilment. Hence, when need fulfilment is realised, adaptation, adjustment and growth can be accomplished (Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017). To a great extent, need fulfilment contributes to intrinsic and self-determined motivation, which in turn is perceived as necessary for deep and sustained learning processes and work engagement (Deci and Ryan Citation2008).

The fulfilment of basic needs in the workplace appears to be a highly relevant motivational resource for in-service teachers. It is shown as related to job engagement (Betoret, Lloret, and Gómez-Artiga Citation2015; Klassen, Perry, and Frenzel Citation2012), job performance (Ghazi and Khan Citation2013), flow and general life satisfaction (Olcar Citation2015). Need fulfilment also leads to lower levels of negative emotions when teaching (Klassen, Perry, and Frenzel Citation2012) and prevents burnout (Betoret, Lloret, and Gómez-Artiga Citation2015). It also mediates the relationship between stress exposure and degree of enthusiasm (Aldrup, Klusmann, and Lüdtke Citation2017). Furthermore, teachers who report high rates of need fulfilment tend to support their pupils’ learning more effectively (Taylor, Ntoumanis, and Standage Citation2008) and provide better opportunities to enhance their pupils’ need fulfilment (Pelletier, Se´guin-Le´vesque, and Legault Citation2002; Roth et al. Citation2007). Consequently, it can be argued that work conditions enabling the fulfilment of psychological needs also support productivity, quality and wellbeing in the teaching profession (Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017).

Despite some evidence pointing to the significance of in-service teachers’ psychological needs and need fulfilment, only a few studies have investigated the conditions and the effects of psychological needs and need fulfilment, both of pre-service teachers and in pre-service teacher education. However, this issue appears to be an important area of research, as it has been shown that motivational factors (32%) and the use of learning opportunities (33%) account for the majority of the learning output of student teachers (Keller-Schneider Citation2016).

Research findings further suggest the relevance of student teachers’ need fulfilment regarding their academic motivation and ability beliefs (Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017), their learning success in classes and lectures (Filak and Sheldon Citation2003; Vermeulen et al. Citation2012), as well as during field experiences (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; Korthagen and Evelein Citation2016). However, field experience has proven to be a challenging research area, mainly because of the distinctive characteristics of practical learning (see McDonald et al. Citation2014).

On one hand, field experiences in schools during pre-service teacher education constitute a complex learning environment (Korthagen et al. Citation2001; Zeichner Citation2012), leading to the assumption that student teachers (being students) exhibit learners’ typical basic psychological needs, such as for autonomy, relatedness and competence (Deci and Ryan Citation2000). This conjecture is substantiated by some empirical findings that need fulfilment does not only vary alongside relevant teaching experiences but is also connected to student teachers’ teaching behaviour (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; Korthagen and Evelein Citation2016).

On the other hand, field experiences in schools during pre-service teacher education also constitute a complex practising environment (Hammerness et al. Citation2005; McDonald et al. Citation2014; Zeichner Citation2012), as learning goals are achieved by actively engaging in core teaching practices and subsequently reflecting on these experiences (Arnold, Gröschner, and Hascher Citation2014; Ball and Forzani Citation2009, Citation2011; Ball et al. Citation2009). This perception leads to the assumption that student teachers (being teachers) also exhibit the typical specific psychological needs that are relevant for the teaching workforce, such as the needs for security (Vasile, Margaritoiu, and Eftimie Citation2011), a thriving teacher–student relationship (Klassen, Perry, and Frenzel Citation2012) and self-actualisation (Mcneil et al. Citation2006; Palak and Papuda-Dolinska Citation2015).

Although it could be argued that the fulfilment of these specific needs might also be relevant for successful field experiences, this issue has never been investigated in pre-service teachers’ field experiences. Despite the clear presence of these two need-related facets of field experiences in pre-service teacher education, to date, no theoretical approach has merged basic and specific psychological needs in this context. Hence, needs and need fulfilment have not been examined in this regard. Indeed, such approach might be fruitful in several aspects. Knowledge on psychological needs and need fulfilment of student teachers during field experiences could not only guide the understanding of motivation, learning processes and beneficial conditions during field experiences. It could also inspire the development of interventions (e.g. mentor training programmes) and instruments (e.g. checklists, learner material) supporting the creation of need-fulfiling practical learning environments. This in turn could support the effectiveness of field experiences and subsequently of entire teacher education programmes, resulting in an enhanced preparation of pre-service teachers for the complex and changing demands of their profession.

This paper aims to add to the prevalently limited knowledge base about student teachers’ psychological needs in field experiences by presenting a theoretical framework, built on the central aspects of the theories of human motivation (Bess Citation1977; Deci and Ryan Citation2000; Maslow Citation1943) and incorporating psychological needs of both learner and teacher sides. With a diary study, evidence is gathered and evaluated testing basic assumptions of the theoretical approach.

2. Theoretical framework

Need fulfilment is described as key to understanding workplace-related motivation (Deci and Ryan Citation2014). It is shown as closely connected to more effective performance (Baard, Deci, and Ryan Citation2004) and high-quality performance (Deci and Ryan Citation2008). Hence, not only is understanding student teachers’ need fulfilment important for the motivational and the emotional aspects of practical phases, but it is also relevant for understanding and predicting practical learning processes and outcomes. For these reasons, the present approach seeks to integrate the needs of student teachers and of in-service teachers into one theoretical framework.

The research literature provides different approaches to studying basic needs of teachers and student teachers based on three established concepts of psychological needs (Bess Citation1977; Deci and Ryan Citation2000; Maslow Citation1943). From a complementary perspective, the individually studied aspects and concepts can be comprehensively subsumed under four need categories (see ).

Table 1. Literature review of studies on psychological needs of teachers and student teachers

Based on the results of this literature review and on the additional knowledge about effective field experiences (as cited in the paragraphs below), the following four dimensions of psychological needs are identified as theoretically relevant for the context of practical learning in pre-service teacher education. The presented framework focuses on the practical phases of pre-service teacher education. Its value is to be seen in bringing together the basic needs of student teachers as both, academic learners and as practitioners into one comprehensive framework. While learner needs are derived from the general concept of basic needs (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), practitioners’ needs are derived from psychological needs of in-service teachers described with concepts from Maslow’s theory of human motivation (Citation1943).

First, the need for introduction is rooted in basic security needs (Maslow Citation1943; Vasile, Margaritoiu, and Eftimie Citation2011) because it incorporates a person’s need for a safe, predictable and controllable (learning and working) environment. In contrast to the typical and well-known learning environments in pre-service teacher education (e.g. lectures and classes), field experiences can trigger a high level of insecurity. The underlying reason is the general unfamiliarity with the practical field (i.e. the actual school visited), as well as the ever-changing work conditions of teachers (Vasile, Margaritoiu, and Eftimie Citation2011). Hence, student teachers want to gain confidence and a sense of safety when moving to the field. They especially appear to strive for spatial, social, hierarchical and organisational orientation and guidance in practical learning environments (Kuzmic Citation1994; Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012). Regarding student teachers’ achievements, research has shown that a proper introduction to the school as a place of working and learning strongly correlates with competence development (Schubarth et al. Citation2009). Fulfilled needs prevent novice teachers from leaving the occupation early (Ingersoll and Smith Citation2004) and even seem to have some impact on students’ achievements (Glazerman et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, the need for introduction resonates with the perception that support for introduction and induction is portrayed as a core role of mentors (Zanting, Verloop, and Vermunt Citation2001).

Second, regarding the concept of social needs (Maslow Citation1943) and the basic need for relatedness (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), the need for relatedness to teacher colleagues and students incorporates the striving for recognition as a professional faculty member and a relevant professional by the students. There are indications that student teachers depend on social support to identify with the teaching profession, which in turn supports them in effectively engaging in teacher education (Han and Yin Citation2016; Roth et al. Citation2007). Being treated as a faculty member (Ferrier-Kerr Citation2009; Wright and Bottery Citation1997; Zanting, Verloop, and Vermunt Citation2001) and building cordial personal and professional relationships with other teachers in the workplace are recognised as important factors for successful learning in field experiences (Abell et al. Citation1995). Student teachers want to know the feeling of being teachers and in this sense, do not want to be regarded and treated as freshmen. They explicitly seek equal footing with in-service teachers (Ashforth and Saks Citation1996; Beck and Kosnik Citation2002; Caires, Almeida, and Vieira Citation2012; Jardine and Field Citation1992; McNally et al. Citation1997). Concerning student teachers’ achievements, the satisfaction of their social needs is shown as positively related to their learning outcomes and competence development during practical phases of their education (Bach Citation2013; Bach, Besa, and Arnold Citation2014; Schubarth et al. Citation2009).

Likewise, meaningful contact with students plays an important role in student teachers’ self-perception (Hascher and Moser Citation2001). Moreover, a professional relationship with students is positively associated with job engagement and negatively associated with emotional pressure (Betoret, Lloret, and Gómez-Artiga Citation2015; Klassen, Perry, and Frenzel Citation2012). Research also suggests that a sound student–teacher relationship contributes to teachers’ identity development and the improvement of their classroom skills, such as the appraisal of teaching situations (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; van der Want et al. Citation2018).

Third, concerning the need for self-affirmation, the desires to feel self-confident, worthy, strong and capable (Maslow Citation1943) become relevant in a professional environment. The needs for autonomy and competence (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) come into play as student teachers tend to seek and choose adequate challenges and want to succeed in field experiences and practical learning (Caires, Almeida, and Vieira Citation2012; Forzani Citation2014; Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017). They strive for an active and increasingly self-determined role in the school community (Mcneil et al. Citation2006) and want to contribute their share to the success of daily operations (Lalitpasan, Wongwanich, and Suwanmonka Citation2014). Moreover, pre-service teachers aim to master the typical tasks of teachers and want to develop their personal skills in performing core teaching practices (Ball et al. Citation2009; Caires, Almeida, and Vieira Citation2012). They also intend to build a positive self-image and boost their self-affirmation as teachers (Meyer and Kiel Citation2014). Student teachers tend to pursue mastery-oriented goals of teaching and hence are more willing to improve relevant competencies when autonomously motivated (Malmberg Citation2006; Roth et al. Citation2007).

Fourth, considering the corresponding concept of Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy, the need for self-actualisation incorporates the striving for solid impressions about the potential for self-actualisation in the work environment (Mcneil et al. Citation2006; Palak and Papuda-Dolinska Citation2015). Student teachers endeavour to properly estimate the extent to which they could fulfil their personal potential in the teaching profession (Kuzmic Citation1994). They want to explore the possibilities of success by engaging in their personal interests and reflecting on their motives and life themes on the job (Caires, Almeida, and Vieira Citation2012; Kuzmic Citation1994). Research confirms that effective and satisfied novice teachers report that their needs are fulfilled through personal contributions to the workplace (Oosterheert and Vermunt Citation2001).

3. Research questions

Field experiences in pre-service teacher education integrate the student (academic learner) and the teacher (practitioner) sides, both connected to motivational characteristics and their respective basic and specific psychological needs. However, previous studies have focused on the student side of practical learning by investigating basic psychological needs only. It has been shown that student teachers exhibit an overall moderate level of need fulfilment during a field experience, varying quite unsystematically over a 14-week period of student teaching. In fact, there is no linear development in any of the three need dimensions (autonomy, competence and relatedness). Additionally, significant relationships between the fulfilment of basic needs and teaching behaviour have been reported (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; Korthagen and Evelein Citation2016).

With the aim of a more balanced concept, four differentiated psychological needs of student teachers during their field experiences are hypothesised on the basis of relevant theoretical concepts and a literature review (see Section 2).

The general approach of presenting a comprehensive theoretical framework and its evaluation by means of gathering empirical data is inspired by recent works from the field of teacher education (e.g. Ní Bhroin and King Citation2020; Ostinelli Citation2016; Van Meeuwen et al. Citation2018).

In the present study the assumptions are tested that for student teachers in practical phases of teacher education there are four distinct need dimensions, each significantly related to certain indicators of success of practical learning. For the purpose of gathering evidence regarding the hypothesised framework and based on the aforementioned findings, the following two explorative research questions are formulated:

How does need fulfilment develop in the course of a field experience with regard to the four dimensions of the proposed framework?

Does need fulfilment regarding the proposed framework relate to certain success indicators in practical learning?

4. Research method

To investigate the aforementioned research questions and to gain insights into the relevance and the fulfilment of the hypothesised needs, a diary study was carried out. In total, 106 student teachers were surveyed in a longitudinal study measuring their need fulfilment at five intervals (days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9) in the course of a ten-day field experience. A two-day interval was chosen to obtain sufficient information without burdening the participants with a daily request, which could have led to a lower quality of the collected data (Ida et al. Citation2012).

The study was conducted at the University of Erfurt, Germany. Similar to most German universities and as regulated by federal law, Erfurt offers an academic pre-service teacher education programme under a consecutive bachelor’s–master’s degree system. However, in contrast to many other universities, Erfurt takes a very systematic approach to practical learning by incorporating ten practical phases (short- and long-term types) over the course of the bachelor’s and the master’s studies. The practical phases begin with orientational field experiences fostering perspective shifts and self-reflection. They later proceed to developing skills and competencies, culminating in a highly demanding and complex long-term practicum at the end of the master’s studies (Protzel, Dreer, and Hany Citation2017). This study was conducted during an early, obligatory and self-organised internship in school, which was prepared and followed up through lectures and workshops at the university. The major goals of this practical phase consist of an observation-based exploration of the central work tasks and the conditions of teachers, as well as an adoption of the perspective of in-service teachers. Student teachers are required to write a ten-page closing report reflecting on their practical experiences. This kind of orientational field experience is quite common in pre-service teacher education programmes throughout Germany.

4.1. Participants and procedure

In total, 106 (85 females) student teachers with an average age of 20.2 years (SD = 6.15) participated in the study, reporting their data at all intervals. The participants were at the end of the third or the fifth semester of their bachelor programme, leading to the Master of Education programme for primary education (n = 72) or secondary education (n = 34) at the University of Erfurt. They visited different self-chosen schools all over the federal state of Thuringia for a two-week duration.

4.2. Instruments

The participants were surveyed using a paper-and-pencil diary with concise instructions about when to record specific data. Altogether, the diary consisted of three sections. The schedule and the instruction for data recording for the first and the last sections were provided during preparatory and follow-up workshops. The data regarding the second section were recorded individually during the field experience. The first section logged general and demographic data prior to the practical phase.

In the second section, the student teachers recorded their need fulfilment on four subscales (see ), repeated at five intervals (at the start of days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9). They were then asked to complete an identical form at the end of the respective survey days. The items were based on an adapted and complemented version of the work-related basic need satisfaction scale (Van den Broeck et al. Citation2010) and were piloted (N = 380) in four previous studies (e.g. Stotzka and Hany Citation2016). The revisions led to a functional, economical and change-sensitive instrument. contains examples of items in the final instrument, as well as descriptive data about the present study sample. The items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = fully applies to 5 = does not apply.

Table 2. Measurement of need fulfilment and descriptive data

The third section of the diary aimed at recording success indicators subsequent to the field experience (see ). Among them were the general indicators learner satisfaction and learning gain, as well as the specific indicators shift from student’s to teacher’s perspective and teacher self-efficacy. The latter indicators were explicit goals of the investigated field experience. Self-reports were collected during a follow-up workshop, which was held several days after the practical phase.

Table 3. Measurement of success of practical learning and descriptive data

Additionally, the level of self-reflection was measured using the grades received by the student teachers in their closing report. By the fourth week after the follow-up workshop, they had to submit a mandatory ten-page written report reflecting on practical experiences regarding their professional development. The papers were rated by the university staff with experiences in school teaching, using an assessment matrix based on a hierarchical model of reflective writing (Imhoff Citation2006). The possible grades ranged from 1 = highest level to 5 = lowest level of self-reflection.

5. Findings

The data analysis focused on the research questions. The missing data were handled using a full-information maximum likelihood estimation. This allowed the use of all available data, which would reduce the bias in parameter estimation resulting from missing data and would increase statistical power (Enders Citation2010). The preparatory steps further consisted of a confirmatory factor analysis, which showed a satisfying model fit for the four dimensions (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.5) and affirmed all scales as distinct constructs. Medium-level, statistically significant intercorrelations of the dimensions were also found at all intervals (rmin = 0.47, rmax = 0.71).

The analysis on the average level of need fulfilment revealed medium to high fulfilment rates for all four dimensions. Notably, the needs for self-affirmation and self-actualisation exhibited lower average fulfilment rates when compared with the needs for introduction and relatedness (see ).

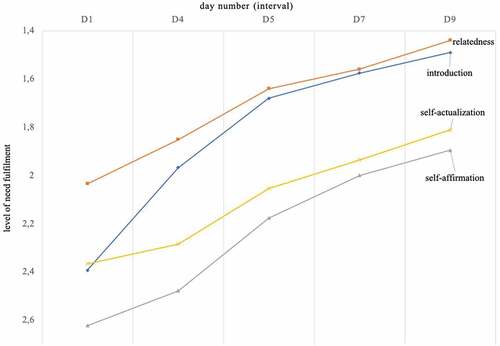

Regarding the development of need fulfilment (research question 1), ANOVAs with repeated measures showed a significant gain in need fulfilment during the ten-day field experience. visualises the development of the average need fulfilment in the course of the practical experiences in the four dimensions.

The direct comparison of the need fulfilment at the first and the last intervals showed large-sized effects for all four dimensions (Cohen Citation1992). The introduction dimension showed the largest gain in need fulfilment (F(4,244) = 63.08, p < 0.001, dt1t5 = 1.23), followed by relatedness (F(4,241) = 47.74, p < 0.001, d = 0.68, dt1t5 = 0.99), self-affirmation (F(4,236) = 45.23, p < 0.001, dt1t5 = 0.90) and self-actualisation (F(4,204) = 16.25, p < 0.001, dt1t5 = 0.70). A visual comparison of the four graphs suggests quite similar linear developments from the second interval (day 3) onwards. However, the starting points partly differed significantly. Further analysis of these differences revealed the effects of familiarity. The student teachers who chose a familiar schoolFootnote1 for their field experience showed higher fulfilment rates regarding the need for introduction on day 1 (n = 71, M = 2.20, SD = 0.85), in contrast to those student teachers who chose an unfamiliar school (n = 35, M = 2.72, SD = 0.81). The difference (d = 0.62) was statistically significant (F(4, 288) = 2.91; p < 0.05) at the first interval (day 1) but could no longer be observed from the second interval (day 3) onwards.

The relationships between need fulfilment and success in practical learning (research question 2) were tested by computing the correlations between a score in need fulfilment (day 1 + day 3 + day 5 + day 7 + day 9) and success indicators (see ). The correlations between the gain in need fulfilment (day 9 – day 1) and success indicators were also computed (see ).

Table 4. Correlations between need fulfilment (score/gain) and success indicators

It became evident that need fulfilment (the score) in the four dimensions was broadly related to the success indicators to a small-to-medium extent. The student teachers who reported more accumulated need fulfilment also exhibited higher rates of learner satisfaction and higher learning gains and more often realised a shift in perspective. Need fulfilment was positively related to teacher self-efficacy as well. Notably, the student teachers who reported higher rates of need fulfilment correspondingly reached higher levels of self-reflection in their written reports. In contrast, the gain in need fulfilment (apart from two significant correlations with learner satisfaction) seemed almost irrelevant. This difference in the findings suggests that consistently high rates of need fulfilment, not gain rates, may be significant when focusing on success in field experiences. However, additional analysis on this matter revealed some explanatory power in fulfilment gains over time. For example, a linear hierarchical regression for the estimation of learning gain brought to light minor but statistically significant changes in R2 at two intervals (see ). Although the fulfilment rates at the start of the experience explained most of the variance in the success indicators, some gains could be observed on day 5 and day 7.

Table 5. Linear hierarchical regression for the estimation of learning gain

6. Discussion

To summarise, the presented findings support the proposed conceptualisation of needs. The evidence confirms the structure of the theoretical conceptualisation, proving the four dimensions as distinct concepts. The average need fulfilment amounts to high rates of the needs for introduction and relatedness and to medium rates of the needs for self-affirmation and self-actualisation. This set of results demonstrates a more differentiated outcome than those provided by prior studies, which report overall moderate rates of fulfilment of basic needs (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; Korthagen and Evelein Citation2016). Furthermore, the presented data support the assumption of the presence of lower-order and higher-order needs (Conley and Woosley Citation2000; Maslow Citation1943).

In tackling the two research questions, further supportive evidence is revealed. A progressive development in need fulfilment is observed for all four dimensions (research question 1). While average gains are visibly similar, starting points differ significantly. As exemplified by further analysis, one reason for these differences involves the factors that vary more or less systematically among groups of pre-service teachers. Several student teachers report a higher fulfilment of their need for introduction on day 1 because of their familiarity with their school prior to the investigated field experience. They thus increase the average fulfilment rate systematically, which might result in differences among the four need concepts on day 1. Future research should investigate the factors responsible for the variance among and within the starting points in need fulfilment. Certain clusters of characteristics might lead to lower or higher fulfilment rates before the beginning of the field experience.

Generally, the average development paths appear plausible in the course of the investigated ten days. This result is in contrast to prior findings (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008) about a rather unsystematic variation in need fulfilment over time. While this finding can be interpreted in favour of the plausibility of the present framework, it could also be attributed to the longer time spans (10 days versus 14 weeks) and measurement intervals organised alongside teaching experiences in prior approaches (Evelein, Korthagen, and Brekelmans Citation2008; Korthagen and Evelein Citation2016). Interestingly, the presence of lower- and higher-order needs is further supported by the reported fulfilment gain rates. The needs for introduction and relatedness show higher gain rates of fulfilment when compared with the needs for self-affirmation and self-actualisation. Based on SDT, it can be argued that one reason lies in the higher complexity of fulfiling the latter two needs in the context of a multifaceted learning environment (Mcneil et al. Citation2006). In this sense, need fulfilment requires a positive upward spiral of autonomously regulated proactivity, in which the individual gains resources by gradually realising increasingly complete self-regulatory processes and effective goal regulation (Strauss and Parker Citation2014). As a consequence, the gained knowledge or skills serve the successful handling of the more complex processes of self-regulation and goal regulation. In this respect, the investigated ten-day practical phase could have simply been too short for the student teachers to further escalate within the spiral. This conjecture should receive attention in future research on long-term practical phases.

However, gain rates do not seem so relevant for the success indicators in practical learning (research question 2). Here, the overall need fulfilment more significantly relates to the following success indicators: learner satisfaction, learning gain, shift in perspective, teacher self-efficacy and self-reflection. This finding highlights the importance of high fulfilment rates right from the start of the field experience. Student teachers who start with low rates and advance to high gains in need fulfilment during their field experience appear to benefit only in terms of learner satisfaction. This outcome seems plausible because higher satisfaction can be regarded as a result of the realised gains. Notably, accumulated need fulfilment is positively related to the level of self-reflection exhibited by the student teachers in their written closing reports some weeks after the practical phase. Therefore, the need-satisfied student teachers do not only report higher learning gains but also demonstrate higher achievements regarding the academic side of practical learning. These results considerably align with the findings of Poom-Valickis et al. (Citation2017).

Altogether, the results support the presented theoretical framework. It becomes clear that when focusing on basic and specific needs, the proposed concept might be superior in explanatory strength compared with the approaches that emphasise only the learner side of practical learning. The results point to a more differentiated picture of need fulfilment and its development during the practical phases of teacher education.

6.1. Limitations

The presented findings were obtained from a rather small sample size. Hence, a careful interpretation is advised, especially regarding their generalisation. The aggregated data also reveal little information about individual development in need fulfilment. When observed at a closer range, different individual development patterns might emerge. Future studies should tackle this problem with larger sample sizes to provide more possibilities for in-depth data analysis.

A further limitation of this present study is its use of self-reports, which are prone to method bias and can inflate the correlations between measures (Blume et al. Citation2010). Following the suggestions of Devos et al. (Citation2007), the potential effects of this bias have been minimised by using anonymised questionnaires and providing sufficient time and support for filling them out. Most importantly, the longitudinal design has reduced the contamination of the success measures, as they have been recorded separately and with a temporal distance from the field experience. Moreover, the use of at least one external criterion (grades in closing reports) supports the validity of the findings to some extent. However, future research should incorporate further external criteria, such as observations, to provide more solid evidence in this regard. Prospective studies could additionally apply methods of mobile experience sampling, especially in recording the need fulfilment data. The benefits could include better accuracy and an enhanced ability to recognise meaningful within-person variability (Carson, Weiss, and Templin Citation2010).

7. Implications for pre-service teacher education

Based on the conclusions drawn from this study, it can be argued that to offer functional and productive field experiences in pre-service teacher education, schools as learning and practising environments should provide possibilities for the fulfilment of the psychological needs of student teachers. This recommendation is in accordance with the argument in favour of learning environments that allow student teachers’ personal choices, goals and opinions in academic and practical contexts (Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017). The present paper makes the point that treating pre-service teachers only as learners who prepare themselves to become future teachers is an insufficient approach. Because student teachers strive for authentic possibilities of experiencing (not simulating) what it means to be teachers, enhancing conditions for practical learning also requires responding to the needs of in-service teachers. In this respect, mentoring and other means of support for pre-service teachers in schools should address and provide possibilities for need fulfilment by using a more holistic approach. Such strategies might incorporate a proper introduction (Hudson Citation2012), a supportive school community (Hudson Citation2012; Lee and Feng Citation2007), the characteristics of the mentor–mentee relationship based on equal footing (Hobson et al. Citation2009), opportunities for choice (Pelletier, Se´guin-Le´vesque, and Legault Citation2002; Poom-Valickis et al. Citation2017), as well as the possibilities for self-affirmation (Wright and Bottery Citation1997), including professional feedback from various sources (Edwards and Protheroe Citation2004; Helman Citation2006; Putnam and Borko Citation2000). Encouraging student teachers to engage in a self-directed process of need fulfilment seems beneficial (Alberta Teachers’ Association Citation2003), especially regarding the alleged differentiation between lower- and higher-order needs. Based on the present findings, a serial approach to need fulfilment is advised. Instead of offering various possibilities for need fulfilment in the beginning of a field experience, it seems plausible to initially dedicate time and support to the fulfilment of the needs for introduction and relatedness (e.g. meet-and-greet sessions, job shadowing, observations). This approach could help secure high rates of need fulfilment from an early stage, which has proven to be crucial for the success of practical learning. Once these lower-order needs are sufficiently fulfilled, higher-order needs should be tackled by providing time and specific support (e.g. teaching experiences, feedback sessions, active engagement). Such a serial approach to need fulfilment aiming at a positive upward spiral (Strauss and Parker Citation2014) could be a major design feature of future field experiences during teacher education.

Acknowledgments

I express gratitude towards Sophie Merl, Madlen Protzel and Ines Stuckatz for supporting data collection and management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Dreer

Benjamin Dreer holds a Master of Education degree in secondary education and a PhD degree in educational sciences. He is currently the scientific manager of the Erfurt School of Education, the centre for teacher education and educational research at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research interests lie in pre-service teacher education, especially in enhancing conditions during field experiences. Furthermore, he is interested in understanding and fostering teacher and student teacher well-being.

Notes

1. Indicators of familiarity: visited school as pupils, had relatives working in the school, had former field experiences in the school, knew the school under other circumstances.

References

- Abell, S. K., D. R. Dillon, C. J. Hopkins, W. D. McInerney, and D. G. O’Brien. 1995. “‘Somebody to Count On’: Mentor/Intern Relationships in a Beginning Teacher Internship Program.” Teaching and Teacher Education 11 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00025-2.

- Alberta Teachers’ Association. 2003. Mentoring Beginning Teachers. Program Handbook. Alberta: Alberta Teachers’ Association.

- Aldrup, K., U. Klusmann, and O. Lüdtke. 2017. “Does Basic Need Satisfaction Mediate the Link between Stress Exposure and Well-being? A Diary Study among Beginning Teachers.” Learning and Instruction 50: 21–30. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.11.005.

- Alexander, P. A. 2008. “Charting the Course for the Teaching Profession: The Energizing and Sustaining Role of Motivational Forces.” Learning and Instruction 18 (5): 483–491. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.006.

- Arnold, K.-H., A. Gröschner, and T. Hascher. 2014. “Pedagogical Field Experiences in Teacher Education: Introduction to the Research Area.” In Pedagogical Field Experiences in Teacher Education: Theoretical Foundations, Programmes, Processes, and Effects, edited by K.-H. Arnold, A. Gröschner, and T. Hascher, 11–28. Münster and New York: Waxmann.

- Arslan, A. 2017. “Basic Needs as Predictors of Prospective Teachers’ Self-Actualization.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 5 (6): 1045–1050. doi:10.13189/ujer.2017.050618.

- Ashforth, B. E., and A. M. Saks. 1996. “Socialization Tactics: Longitudinal Effects on Newcomer Adjustment.” Academy of Management Journal 39 (1): 149–178.

- Baard, P. P., E. L. Deci, and R. M. Ryan. 2004. “Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Well-being in Two Work Settings.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34: 2045–2068. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x.

- Bach, A. 2013. Kompetenzentwicklung im Schulpraktikum [Competence Development during Field Experiences]. Münster: Waxmann.

- Bach, A., K.-S. Besa, and K.-H. Arnold. 2014. “Conditions of Learning Processes during Internships: Results from the Project TSDI (Teacher Student Development in Internships).” In Pedagogical Field Experiences in Teacher Education: Theoretical Foundations, Programmes, Processes, and Effects, edited by K.-H. Arnold, A. Gröschner, and T. Hascher, 165–183. Münster: Waxmann.

- Ball, D. L., and F. M. Forzani. 2009. “The Work of Teaching and the Challenge for Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 60 (5): 497–511. doi:10.1177/0022487109348479.

- Ball, D. L., and F. M. Forzani. 2011. “Building a Common Core for Learning to Teach and Connecting Professional Learning to Practice.” American Educator 35 (2): 17–21.

- Ball, D. L., L. Sleep, T. A. Boerst, and H. Bass. 2009. “Combining the Development of Practice and the Practice of Development.” The Elementary School Journal 109 (5): 458–474. doi:10.1086/596996.

- Barcelos, A. M. F. 2016. “Student Teachers’ Beliefs and Motivation, and the Shaping of Their Professional Identities.” In Beliefs, Agency and Identity in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching, edited by P. Kalaja, A. M. F. Barcelos, M. Aro, and M. Ruohotie-Lyhty, 71–96. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Beck, C., and C. Kosnik. 2002. “Components of a Good Practicum Placement: Student Teacher Perceptions.” Teacher Education Quarterly 29 (2): 81–98.

- Bess, J. L. 1977. “The Motivation to Teach.” The Journal of Higher Education 48 (3): 243–258. doi:10.2307/1978679.

- Betoret, F. D., S. Lloret, and A. Gómez-Artiga. 2015. “Teacher Support Resources, Need Satisfaction and Well-Being.” Spanish Journal of Psychology 18 (6): 1–12.

- Blume, B. D., J. K. Ford, T. T. Baldwin, and J. L. Huang. 2010. “Transfer of Training: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Management 36 (4): 1065–1105. doi:10.1177/0149206309352880.

- Blumenfeld, P. C., T. M. Kempler, and J. S. Krajcik. 2006. “Motivation and Cognitive Engagement in Learning Environments.” In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, edited by R. K. Sawyer, 475–488. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Caires, S., L. Almeida, and D. Vieira. 2012. “Becoming a Teacher: Student Teachers’ Experiences and Perceptions about Teaching Practice.” European Journal of Teacher Education 35 (2): 163–178. doi:10.1080/02619768.2011.643395.

- Carson, R. L., H. M. Weiss, and T. J. Templin. 2010. “Ecological Momentary Assessment: A Research Method for Studying the Daily Lives of Teachers.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 33 (2): 165–182. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2010.484548.

- Cohen, J. 1992. “A Power Primer.” Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

- Conley, S., and S. A. Woosley. 2000. “Teacher Role Stress, Higher Order Needs and Work Outcomes.” Journal of Educational Administration 38 (2): 179–201. doi:10.1108/09578230010320163.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2014. “The Importance of Universal Psychological Needs for Understanding Motivation in the Workplace.” In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory, edited by M. Gagne, 13–32. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2000. “The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behaviour.” Psychological Inquiry 11 (4): 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2008. “Facilitating Optimal Motivation and Psychological Well-Being across Life’s Domains.” Canadian Psychology 49: 14–23. doi:10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14.

- Devos, C., X. Dumay, M. Bonami, R. Bates, and E. F. Holton III. 2007. “The Learning Transfer System Inventory (LTSI) Translated into French: Internal Structure and Predictive Validity.” International Journal of Training and Development 11 (3): 181–199. doi:10.1111/ijtd.2007.11.issue-3.

- Edwards, A., and L. Protheroe. 2004. “Teaching by Proxy: Understanding How Mentors are Positioned in Partnerships.” Oxford Review of Education 30 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1080/0305498042000215511.

- Enders, C. K. 2010. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

- Evelein, F., F. Korthagen, and M. Brekelmans. 2008. “Fulfilment of the Basic Psychological Needs of Student Teachers during Their First Teaching Experiences.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (5): 1137–1148. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.001.

- Ferrier-Kerr, J. L. 2009. “Establishing Professional Relationships in Practicum Settings.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (6): 790–797. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.001.

- Filak, V. F., and K. M. Sheldon. 2003. “Student Psychological Need Satisfaction and College Teacher-Course Evaluations.” Educational Psychology 23 (3): 235–247. doi:10.1080/0144341032000060084.

- Forzani, F. M. 2014. “Understanding ‘Core Practices’ and ‘Practice-based’ Teacher Education: Learning from the Past.” Journal of Teacher Education 65 (4): 357–368. doi:10.1177/0022487114533800.

- Ghazi, S. R., and I. U. Khan. 2013. “Teachers’ Need Satisfaction and Their Performance in Secondary Schools of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.” Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 2 (3): 87–94.

- Glazerman, S., E. Isenberg, S. Dolfin, M. Bleeker, A. Johnson, M. Grider, and M. Jacobus. 2010. “Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction. Final Results from a Randomized Controlled Study.” Accessed 5 January 2019. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee

- Hammerness, K., L. Darling-Hammond, J. Bransford, D. Berliner, M. Cochran-Smith, M. McDonald, and K. Zeichner. 2005. “How Teachers Learn and Develop.” In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World, edited by L. Darling-Hammond and J. Brandsford, 358–390. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Han, J., and H. Yin. 2016. “Teacher Motivation: Definition, Research Development and Implications for Teachers.” Cogent Education 3 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1217819.

- Hascher, T. 2012. “Lernfeld Praktikum – Evidenzbasierte Entwicklungen in der Lehrer/innenbildung.” [ Learning Setting Student Teaching – Evidence-based Developments in Teacher Education.] Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung 2: 109–129. doi:10.1007/s35834-012-0032-6.

- Hascher, T., and P. Moser. 2001. “Betreute Praktika – Anforderungen an Praktikumslehrerinnen und -lehrer.” [ Supervised Field Experiences – Requirements for Teachers and Mentors.] Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung 19: 217–231.

- Helman, L. 2006. “What’s in a Conversation? Mentoring Stances in Coaching Conversations and How They Matter: Developing New Leaders for New Teachers.” In Mentors in the Making. Developing New Leaders for New Teachers, edited by B. Achinstein and S. Z. Athanases, 69–82. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Hobson, A. J., P. Ashby, A. Malderez, and P. D. Tomlinson. 2009. “Mentoring Beginning Teachers: What We Know and What We Don’t.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (1): 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001.

- Hudson, P. 2012. “How Can Schools Support Beginning Teachers? A Call for A Timely Induction and Mentoring for Effective Teaching.” Australian Journal for Teacher Education 37 (7): 71–84. doi:10.14221/ajte.2012v37n7.1.

- Ida, M., P. E. Shrout, J. P. Laurenceau, and N. Bolger. 2012. “Using Diary Methods in Psychological Research.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Foundations, Planning, Measures and Psychometrics, edited by H. Cooper, 277–305. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Imhoff, M. 2006. Portfolio und Reflexives Schreiben in der Lehramtsausbildung [Portfolio and Reflective Writing in Teacher Education]. Tönning, Lübeck, Marburg: Der Andere Verlag.

- Ingersoll, R. M., and T. M. Smith. 2004. “Do Teacher Induction and Mentoring Matter?” NASSP Bulletin 88 (638): 22–40. doi:10.1177/019263650408863803.

- Jardine, D., and J. Field. 1992. “‘Disproportion, Monstrousness, and Mystery’: Ecological and Ethical Reflections on the Initiation of Student Teachers into the Community of Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 8 (3): 301–310. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(92)90028-2.

- Keller-Schneider, M. 2016. “Student Teachers’ Motivation Matters!” Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov 9 (58): 2–10.

- Klassen, R. M., N. E. Perry, and A. C. Frenzel. 2012. “Teachers’ Relatedness with Students: An Underemphasized Component of Teachers’ Basic Psychological Needs.” Journal of Educational Psychology 104 (1): 150–165. doi:10.1037/a0026253.

- Korthagen, F. A. J., and F. G. Evelein. 2016. “Relations between Student Teachers’ Basic Needs Fulfillment and Their Teaching Behavior.” Teaching and Teacher Education 60: 234–244. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.021.

- Korthagen, F. A. J., J. Kessels, B. Koster, B. Lagerwerf, and T. Wubbels. 2001. Linking Practice and Theory: The Pedagogy of Realistic Teacher Education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kuzmic, J. 1994. “A Beginning Teacher’s Search for Meaning: Teacher Socialization, Organizational Literacy, and Empowerment.” Teaching and Teacher Education 10 (1): 15–27. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)90037-X.

- Lalitpasan, U., S. Wongwanich, and S. Suwanmonka. 2014. “Career Preparation: Identification of Student Teachers’ Needs in the School-to-Work Transition.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 116: 3405–3409. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.186.

- Lee, J., and S. Feng. 2007. “Mentoring Support and the Professional Development of Beginning Teachers: A Chinese Perspective.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 15 (3): 243–262. doi:10.1080/13611260701201760.

- Malmberg, L.-E. 2006. “Goal Orientation and Teacher Motivation among Teacher Applicants and Student Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (1): 58–76. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.005.

- Maslow, A. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346.

- McDonald, M., E. Kazemi, M. Kelley-Petersen, K. Mikilasy, J. Thompson, S. W. Valencia, and M. Windschitl. 2014. “Practice Makes Practice: Learning to Teach in Teacher Education.” Peabody Journal of Education 89: 500–515. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2014.938997.

- McNally, J., P. Cope, B. Inglis, and I. Stronach. 1997. “The Student Teacher in School: Conditions for Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 13 (5): 485–498. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(96)00057-1.

- Mcneil, M., A. W. Hood, P. Y. Kurtz, J. S. Thousand, and A. I. Nevin. 2006. “A Self-Actualization Model for Teacher Induction into the Teaching Profession: Accelerating the Professionalization of Beginning Teachers.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Teacher Education Division, Council for Exceptional Children, San Diego, CA, November 21–24.

- Meyer, B. E., and E. Kiel. 2014. “Wie Lehramtsstudierende ihr Praktikum erleben – Selbstbildbeschädigung, Selbstbildbestärkung und Entwicklung.” [ How Pre-Service Teachers Experience Internships – Damage, Affirmation and Development of Self-Perception.] Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung 4 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1007/s35834-013-0075-3.

- Ní Bhroin, Ó., and F. King. 2020. “Teacher Education for Inclusive Education: A Framework for Developing Collaboration for the Inclusion of Students with Support Plans.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (1): 38–63. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1691993.

- Olcar, D. 2015. “Teacher’s Life Goals and Well-Being: Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs and Flow.” PhD diss., University of Zagreb. Accessed 5 January 2019. https://tinyurl.com/ydf9rgya

- Oosterheert, I. E., and J. D. Vermunt. 2001. “Individual Differences in Learning to Teach – Relating, Cognition, Regulation and Affect.” Learning and Instruction 11 (2): 133–156. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(00)00019-0.

- Ostinelli, G. 2016. “The Many Forms of Research-informed Practice: A Framework for Mapping Diversity.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (5): 534–549. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1252913.

- Palak, Z., and B. Papuda-Dolinska. 2015. “Self-Actualisation as an Essential Dimension of Professional Competence of Special Teacher.” Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie – Sklodowska 17 (2): 9–27.

- Pelletier, L. G., C. Se´guin-Le´vesque, and L. Legault. 2002. “Pressure from above and Pressure from below as Determinants of Teachers’ Motivation and Teaching Behaviors.” Journal of Educational Psychology 94 (1): 186–196. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.186.

- Poom-Valickis, K., K. Rumma, D. Francesconi, and K. Joosu. 2017. “Relations between Student Teachers’ Basic Needs Fulfillment, Study Motivation, and Ability Beliefs.” Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology, Portugal, October 11–14.

- Protzel, M., B. Dreer, and E. Hany. 2017. “Studienangebote zur Entwicklung von Handlungs-, Begründungs- und Reflexionskompetenzen. Das Praktikumskonzept der Erfurter Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung.” [Elements of Pre-Service Teacher Education Fostering Competencies Central to Performance, Reasoning and Reflection.] In Konzeptionelle Perspektiven Schulpraktischer Studien, edited by U. Fraefel and A. Seel, 91–104. Münster: Waxmann.

- Putnam, R. T., and H. Borko. 2000. “What Do New Views of Knowledge and Thinking Have to Say about Research on Teacher Learning?” Educational Researcher 29 (1): 4–15. doi:10.3102/0013189X029001004.

- Reeve, J., and Y.-L. Su. 2014. “Teacher Motivation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory, edited by M. Gagne, 349–362. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reeve, J., E. Bolt, and Y. Cai. 1999. “Autonomy-Supportive Teachers: How They Teach and Motivate Students.” Journal of Educational Psychology 91 (3): 3537–3548. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.537.

- Richardson, P. W., and H. G. Watt. 2018. “Teacher Professional Identity and Career Motivation: A Lifespan Perspective: Mapping Challenges and Innovations.” In Research on Teacher Identity – Mapping Challenges and Innovations, edited by P. A. Schutz, J. Hong, and D. C. Francis, 37–48. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Rißmann, J., U. Feine, and U. Schramm. 2013. “Vom Schüler zum Lehrer – Biografische Selbstreflexion in der Lehramtsausbildung.” [From Student to Teacher – Biographical Self-Reflection during Teacher Education.] In Professionalisierung Durch Trainings, edited by B. Jürgens and B. Krause, 125–137. Aachen: Shaker.

- Roth, G., S. Assor, Y. Kanat-Maymon, and H. Kaplan. 2007. “Autonomous Motivation for Teaching: How Self-Determined Teaching May Lead to Self-Determined Learning.” Journal of Educational Psychology 99 (4): 761–774. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.761.

- Rovai, A. P., M. J. Whighting, J. D. Baker, and L. D. Grooms. 2009. “Development of an Instrument to Measure Perceived Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor Learning in Traditional and Virtual Classroom Higher Education Settings.” The Internet and Higher Education 12 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.002.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “The Darker and Brighter Sides of Human Existence: Basic Psychological Needs as a Unifying Concept.” Psychological Inquiry 11 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_03.

- Sayeski, K. L., and K. J. Paulsen. 2012. “Student Teacher Evaluations of Cooperating Teachers as Indices of Effective Mentoring.” Teacher Education Quarterly 39 (2): 48–67.

- Schmitz, G. S., and R. Schwarzer. 2000. “Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen von Lehrern: Längsschnittbefunde mit einem neuen Instrument.” [ Perceived Self-Efficacy of Teachers: Longitudinal Findings with a New Instrument.] Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 14 (1): 12–25. doi:10.1024//1010-0652.14.1.12.

- Schubarth, W., K. Speck, A. Seidel, and M. Wendland. 2009. “Unterrichtskompetenzen bei Referendaren und Studierenden. Empirische Befunde der Potsdamer Studien zur ersten und zweiten Phase der Lehrerausbildung.” [ Teaching Competencies for Trainees and Students. Empirical Findings of the Potsdam Studies on First and Second Phases of Teacher Education.] Lehrerbildung auf dem Prüfstand 2 (2): 304–324.

- Stotzka, C., and E. Hany. 2016. Lerngelegenheiten und Lerngewinne im Komplexen Schulpraktikum [Learning Opportunities and Learning Gains within the Complex Field Experience]. Online Research Report. Erfurt: University of Erfurt. https://tinyurl.com/r7mdwfq

- Strauss, K., and S. K. Parker. 2014. “Effective and Sustained Proactivity in the Workplace: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory, edited by M. Gagne, 50–71. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, I., N. Ntoumanis, and M. Standage. 2008. “A Self-Determination Theory Approach to Understanding the Antecedents of Teachers’ Motivational Strategies in Physical Education.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 30 (1): 75–94. doi:10.1123/jsep.30.1.75.

- Topala, I., and S. Tomozzi. 2014. “Learning Satisfaction: Validity and Reliability Testing for Students’ Learning Satisfaction Questionnaire (SLSQ).” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 128: 380–386. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.175.

- Uzman, E. 2014. “Basic Psychological Needs and Psychological Health in Teacher Candidates.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 116: 3629–3635. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.814.

- Van den Broeck, A., M. Vansteenkiste, H. De Witte, B. Soenens, and W. Lens. 2010. “Capturing Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness at Work: Construction and Initial Validation of the Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 981–1002. doi:10.1348/096317909X481382.

- van der Want, A. C., P. den Brok, D. Beijaard, M. Brekelmans, L. C. A. Claessens, and H. J. M. Pennings. 2018. “Changes over Time in Teachers’ Interpersonal Role Identity.” Research Papers in Education 33 (3): 354–374. doi:10.1080/02671522.2017.1302501.

- Van Meeuwen, P., F. Huijboom, E. Rusman, M. Vermeulen, and J. Imants. 2018. “Towards a Comprehensive and Dynamic Conceptual Framework to Research and Enact Professional Learning Communities in the Context of Secondary Education.” European Journal of Teacher Education. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1693993.

- Vasile, C., A. Margaritoiu, and S. Eftimie. 2011. “Security Needs among Teachers.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 29: 1251–1256. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.360.

- Vermeulen, M., Q. Castelijns, Q. Kools, and B. Koster. 2012. “Measuring Student Teachers’ Basic Psychological Needs.” Journal of Education for Teaching 38 (4): 453–467. doi:10.1080/02607476.2012.688556.

- Wright, N., and M. Bottery. 1997. “Perceptions of Professionalism by the Mentors of Student Teachers.” Journal of Education for Teaching 23 (3): 235–252. doi:10.1080/02607479719981.

- Zanting, A., N. Verloop, and J. D. Vermunt. 2001. “Student Teachers’ Beliefs about Mentoring and Learning to Teach during Teaching Practice.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 71 (1): 57–80. doi:10.1348/000709901158398.

- Zeichner, K. 2010. “Rethinking the Connections between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-Based Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 61 (1–2): 89–99. doi:10.1177/0022487109347671.

- Zeichner, K. 2012. “The Turn once Again toward Practice-Based Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 63 (5): 376–382. doi:10.1177/0022487112445789.