ABSTRACT

Equity-centred teacher education recognises the dual challenge of preparing teachers to support the learning of all students while encouraging future teachers to recognise and challenge societal systems reproducing inequity. The paper focuses on analysing Finnish student teachers’ perceptions of teachers’ skills related to diversity and equity. The data are drawn from written individual and group assignments completed during three master’s level courses in home economics teacher education. A qualitative content analysis of students’ assignments present student teachers’ collaboratively produced understanding of teachers’ diversity skills. Their self-assessment of both professional strengths and areas of development are evaluated against Paul Gorski’s equity literacy framework. The findings are suggestive of a relatively strong cultural self-awareness and response-ability related to learner diversity. More attention should be given to unfolding structural inequities to enable future teachers to develop the equity literacy necessary to create and sustain equitable learning environments.

Introduction

Equity-centred teacher education is characterised and challenged by the twin goals of preparing teacher candidates to enhance the learning of diverse students while recognising and challenging the intersecting systems of inequality that reproduce inequity in schools and in society (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016, 70).Footnote1 Balancing the two goals challenges teacher educators to navigate their students’ dispositions while effectively equipping them with the necessary knowledge and skills to create and sustain equitable learning environments (Trent, Kea, and Kevin Citation2008; Gorski Citation2016a). Advancing social justice and equity in teacher education requires combining individual efforts with collective and institutional changes (Nieto Citation2000; Biesta Citation2017). Research on equity-centred teacher education is required to improve local programmes and to build theories on how student teachers learn to enact equity in practice (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016).

This paper discusses the promotion of equity in the context of a Master’s level teacher education programme in Finland.Footnote2 The pursuit of educational equity has long been a major goal of Finnish education (Niemi and Isopahkala-Bouret. Citation2015; Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2016; Brunila and Kallioniemi Citation2018). As emphasised by Cochran-Smith et al. (Citation2016), different assumptions about the sources of inequality and inequity result in different ideas about solutions to complex, multifaceted educational inequalities. In the Finnish context, equity has been defined as equal access, equity across the country, equality of opportunities, respect for the diversity of individuals and equal distribution of resources (Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2016). The available institutional tools, including educational institutions’ compulsory, functional equality and equality plans provide frameworks for advancing and monitoring the realisation of equality and equity in education. Also, the current curricula for basic education (NCCBECitation2016) emphasise the importance of seeing each learner as a unique individual possessing an unquestionable right to quality education. In addition to equality and equity, the operational culture principles guiding work in schools include learning community, wellbeing, safety of everyday life, active interaction, use of versatile learning methods, plurality of cultures and multilingualism, sense of belonging, democratic practices, environmental responsibility and sustainability (National Core Curriculum for Basic Education Citation2016. (NCCBE) 2016). The current curricula for basic education in Finland places a demand for (future) teachers and teacher educators to reflect on what these principles mean in practice in basic education and teacher education. An early analysis of the curricula implementation indicated an increased level of teacher reflection and diversification of pedagogical practice (Venäläinen et al. Citation2020).

Societal structures, access and academic achievement as well as structures within classrooms influence the social justice outcomes of education. Social justice can be approached from both its distributive and relational dimensions. Positioning oneself in relation to these dimensions is a challenge for teachers (Boylan and Woolsey Citation2015). Research on early-career teachers has shown polarised positions of commitment and resistance to social justice (Boylan and Woolsey Citation2015). For early-career teachers, the focus may often be on the micro level and on the ways in which their own classrooms are sites for enacting more socially just relationships and practices (Boylan, Citation2009). In Finland, teachers’ role in advancing social justice is emphasised. The high level of autonomy that teachers have (e.g. decisions on teaching methods and material) makes teachers’ attitudes, behaviours and actions with regard to justice or injustice powerful (Layne and Dervin Citation2016).

Responding to learner diversity has been emphasised both in research and in the current public discourse on equity. In a recent study of Finnish school leaders’ and newly qualified teachers’ professional development needs (Harju and Niemi Citation2018), both groups emphasised students’ learning and diversity, differentiated teaching, acquiring competence for special needs education, and working with student welfare groups as key challenges. Recognitive justice, or socially just relationality, includes recognition of, and respect for, social and cultural difference (Cochran-Smith Citation2010; Boylan and Woolsey Citation2015). However, the equity discourses in Finnish teacher education have been criticised for focusing on location and ethnicity, thus reflecting a limited understanding of diversity and interculturality and obscuring the underlying societal inequities (e.g. Layne and Dervin Citation2016). Drawing on an analysis of diversity in education in the US context, Gorski (Citation2016b) describes this as an epidemic of trying to remedy injustice-based problems with culture-based strategies and thus training teachers to be culturally sensitive rather than racially or linguistically just. Making equity rather than culture central in conversations and practices related to educational justice thus remains a challenge for equity efforts (Gorski Citation2016b).

Given the critical role of initial teacher education in creating conditions for equity awareness, this exploratory enquiry with Finnish student teachers enrolled in home economics subject teacher education aims at conceptualising and supporting the introduction of equity education as a critical component of initial teacher education. The present analysis of equity starts from a skills-focused approach of responding to learner diversity, studying how future teachers conceptualise diversity and pedagogies responding to learner diversity. In addition, student teachers’ reflections on their own practice in intercultural groups are analysed to access the wider structural dimensions of equity. As the interconnectedness of everyday life and societal development is at the centre of home economics (Turkki Citation2015) and as it is a school subject characterised by collaboration and communication (e.g. Venäläinen Citation2010), home economics provides a favourable learning context in an increasingly diverse world (Janhonen-Abruquah et al. Citation2017) and can thereby educate towards social justice (Dupuis Citation2017). To benefit from this potential, home economics teachers need both theoretical and practical tools to help them better understand the ongoing changes in society, work with diverse learners and respond to inequities.

The exploratory study conducted in 2017–2019 places the voices and perspectives of home economics student teachers at the centre of the analysis of diversity and equity. The research is part of a research project Home economics education for diversities (https://blogs.helsinki.fi/heedproject/) that develops home economics pedagogy that draws from (learner) diversity as a resource and advances equity. The present study analyses how future home economics teachers perceive skills related to diversity, equality and equity and how these skills can be viewed as part of teachers’ equity literacy. The participating master’s students were asked to identify and reflect on the skills and competences critical to home economics teachers in increasingly diverse and intercultural school contexts for responding to diversity and promoting equity. Student voice and collaborative approaches to teacher education development (e.g. Cook‐Sather Citation2006) were utilised to create a shared space for knowledge construction on equity in education in relation to teachers’ professional skills. The overall objective was to identify and better respond to the learning needs of future teachers and thus support learning to enact equity in practice (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016).

Equity and social justice in intercultural teacher education

Teachers’ changing work contexts are characterised by balancing personal beliefs and institutional demands, structures and constraints (e.g. Toom and Husu Citation2018). Cognisant of this, equity-centred teacher education operates within the tension between assumptions on teachers’ critical role in supporting the learning of students from different backgrounds while acknowledging the limitations in teachers’ opportunities to reduce inequity (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016). According to the review of teacher education research by Goodwin and Darity (Citation2019), the connection of personal and contextual knowledge is present in teacher education for social justice in different contexts.

In initial teacher education, equity-focused content is often labelled as intercultural or multicultural education. In the Nordic countries, the discourse that has shifted from multiculturalism to interculturalism that reflects a more active, dynamic relation between social groups that is constantly being debated and contested (Mikander, Zilliacus, and Holm Citation2018). The notion of ‘intercultural’ has been criticised for its tendency to blur the complexity and dynamic nature of culture, thus resulting in either essentialism or relativism (Gorski Citation2016b; Mikander, Zilliacus, and Holm Citation2018). The intercultural competence focused approach prevalent in initial teacher education is at risk of obscuring the underlying societal inequities (Layne and Dervin Citation2016). Furthermore, inequities reach beyond cultural diversity and thus require an intersectional analysis (Lappalainen and Lahelma Citation2016). Calls have thus been made to shift the focus of discussion from culture to justice (Mikander, Zilliacus, and Holm Citation2018) and equity (Gorski Citation2016b; Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016).

Teachers’ relationships to beliefs and principles of social justice can be conceptualised as their social justice identity. Boylan and Woolsey (Citation2015) argued for the importance of adopting a complex understanding of identity to theorise about teacher education for social justice and to inform pedagogy. Lanas (Citation2014) has argued that the current, performative teacher education framework may not be able to provide the conceptual, theoretical, philosophical, emotional or personal space to ask difficult questions about historical, political, cultural or social contexts. Besides being a forum for teaching the skills needed to imagine new possibilities for social justice, intercultural teacher education is a forum where this imagining can occur through encountering multiple others, engaging with difficult knowledge and exploring zones of discomfort (see also Layne and Dervin Citation2016; Posti-Ahokas, Janhonen-Abruquah, and Johnson Longfor Citation2017).

Possibilities for multifaceted negotiations within teacher education in Finland are constrained by its limited openness to students and faculty from minority groups (Lanas Citation2014; Layne and Dervin Citation2016). Considering this, teacher education pedagogy for social justice should provide a space for critical self-analysis (Gorski Citation2016a; Mills and Ballantyne Citation2010), enquiry into personal positionalities and connecting them with the roots and dimensions of injustice (Boylan and Woolsey Citation2015). Over 15 years ago, Gay and Kirkland (Citation2003) called for engaging pre-service teachers in critical cultural consciousness and personal reflection that are achieved through learning experiences taking place within guided practice, authentic examples, and realistic situations. According to them, it is not enough to have courageous conversations about racism and social injustices; to generally appreciate cultural differences and accept the need to be reflective about pre-service teachers’ professional practice and personal beliefs, the power of real life experiences becomes evident. More recently, Boylan and Woolsey (Citation2015) introduced the notion of ‘pedagogy of discomfort’, aiming at recognising privilege and emotional engagement in relation to the sources and reproduction of injustice. The discomfort can be a result of enquiry or enquiry may be fostered as a result of the discomfort experienced.

The complexity of pedagogical conversation in teacher education about politically and emotionally charged issues of equity and social justice requires pedagogies that extend beyond content knowledge construction and skills development (Gorski Citation2016a). According to Lanas (Citation2014), analysis of knowledge production, retaining various and changing perceptions of self and other, navigating challenges and constantly changing emotions are required in pedagogical relationships for intercultural education. In their dispositional typology developed in an initial teacher education context, Mills and Ballantyne (Citation2010) suggest how dispositions are hierarchically developed from self-awareness through openness and further towards commitment to social justice. Development of such dispositions requires time, which is a scarce resource in teacher education programmes worldwide (e.g. Mills and Ballantyne Citation2010; Gorski Citation2016a).

Pedagogies of intercultural teacher education that aim at reaching beyond the performative framework (Lanas Citation2014) have been developed in critical higher education pedagogy research. Based on an analysis of student teachers’ narratives of meaningful intercultural encounters, Dervin (Citation2017) emphasised that students do not start their intercultural teacher education from scratch, as even those who have neither been in contact with the ‘other’ nor travelled abroad are already acquainted with interculturality through the media, arts, fiction and prior schooling. In their narratives, Dervin (Citation2017) sees the ability of student teachers to un-learn and re-learn and to move beyond appearances and assumptions. The role of teacher education in increasingly heterogeneous societies is to provide theoretical, methodological, and reflexive tools for understanding and interpreting the intercultural experiences students have already experienced. In our previous work (Posti-Ahokas, Janhonen-Abruquah, and Johnson Longfor Citation2017), we have encouraged student teachers to expose themselves to new intercultural encounters and to use the encounters as a basis for personal reflection. Encounters with the diverse world around their proximal environment helped students to face biases, deal with their own prejudges and to analyse and act meaningfully in different situations. However, these experiences do not necessarily enable sufficient consideration of equity issues. With this in mind, we set out to explore pedagogies that could enable moving between teachers’ agency and the structures of equity as part of intercultural teacher education in the Finnish context.

Teachers’ equity literacy

The complexity of equity-centred teaching challenges the existing skills and competence-oriented conceptualisations present in performance-oriented teacher education. To recognise levels beyond teachers’ subject-oriented practice, generic skills (e.g. Tynjälä et al. Citation2016) and literacies (e.g. Gorski Citation2016a; Pennington et al. Citation2013) have been suggested to capture the overarching issues and qualities. In teacher education, these notions could potentially be supported by the increasing emphasis on generic skills and competences over subject-matter-based objectives in curricula at different levels (Hakala and Kujala Citation2021; Harju and Niemi Citation2018; Toom and Husu Citation2018). In the context of intercultural teacher education, Dervin, Moloney, and Simpson (Citation2020) suggested using ‘competences’, in the plural, to recognise the various dimensions of teachers’ intercultural competence. Further, viewing competences as relational, co-constructed and affected by societal structures and people’s positionings requires moving beyond perceiving competence as something an individual is responsible for developing (Biesta Citation2017; Layne and Dervin Citation2016). Similarly, following Joldersma (Citation2011), Lanas (Citation2014) proposed an emphasis on ‘thoughtfulness’ rather than on specific competences, in approaching each situation simultaneously with the ethics of a teacher and the humility of a learner.

In linking the discourses of equity/justice and teacher competences in intercultural teacher education, we have found Paul Gorski’s notion of equity literacy particularly useful. Gorski defines equity literacy as ‘cultivating critical consciousness’ (Gorski Citation2016a, 141) and ‘cultivating in teachers the knowledge and skills necessary to become a threat to the existence of inequity in their spheres of influence’ (Gorski Citation2016b, 225). The equity literacy framework (Gorski and Swalwell Citation2015; Gorski Citation2016b, Citation2017) maps out the teacher abilities contributing to equity literacy as 1) recognising biases and inequities, 2) responding to them, 3) redressing them in the long term and 4) creating and sustaining bias-free and equitable learning environments. Together, these abilities depict the qualities of equity-literate educators, incorporating ‘culture’ with inequity within educators’ spheres of influence. While acknowledging and encouraging teachers’ professional agency, the framework foregrounds equity by highlighting the structural conditions constraining agency and requiring resistance. From the perspective of student teachers, it is important to work the generic competences and insight regarding social structures into more concrete skills and thoughtful actions. For this reason, skills were used as a starting point in our study with Finnish student teachers. Through a collaborative process starting from an analysis of curricula and resulting in formulations of teachers’ diversity skills, we aimed to contextualise student teachers’ reflections within the equity framework to capture issues beyond teachers’ immediate work environment.

Method

The exploratory research approach utilised in the present study attempted to generate new ideas and weave them together into a model. According to Stebbins (Citation2001), a key purpose of exploration in social research is to become familiar with something by testing it or experimenting with it with the aim of creating a particular effect or product. Stebbins’s (Citation2001) notion of concatenated exploration refers to data collection based on leads suggested by findings from studies carried out earlier in the chain. The data is accumulated across a chain of exploratory studies, thus growing the grounded theory in detail, breadth and validity. In the present project, a series of interconnected stages of enquiry was used to deepen understanding of student teachers’ conceptualisations of diversity skills and the processes that led to these formulations, in line with the dual aims of research to improve practice and develop theory (Cook‐Sather Citation2006). Stebbins (Citation2001) points out that concatenated exploration is particularly useful in team research. The research profits from the discoveries of several investigators who all see the field differently. In our case, the collaboration between researchers originated as pedagogical collaboration around two university courses and later resulted in sustained research collaboration.

The research was conducted in the context of a new master’s level compulsory course for home economics student teachers over three consecutive years (2017–2019). The course: home economics in a diverse society, has developed over the years from two optional courses that have served as a platform for several research and pedagogical development projects since 2013 (three references removed for anonymity). In the present study, students’ assignments from the three years were used anonymously as research data with informed consent from the student teachers. (Non-) participation in the study did not add to/reduce students’ workload or influence assessment in any way. The research design consisting of three consecutive cycles, each utilising different sets of data and producing specific outcomes contributing to the whole, is described in .

Table 1. Summary of the assignments and the research approaches used with the three consecutive student cohorts.

Table 2. Categorisation of home economics teachers’ diversity skills identified by student teachers.

Results

A typology of home economics teachers’ diversity skills

Through the content analysis of students’ assignments, the researchers identified 27 different skills and calculated their prevalence across the dataset. The skills were first categorised into seven sub-categories and then further into three main categories, which were self-awareness, teacher practice to support diversity and professional development ().

The analysis of diversity skills suggested by student teachers contains the dimensions of self-awareness, teacher practice and the process of professional development. Based on this analysis, student teachers consider diversity skills as something reflected primarily in the practice of teachers. Teacher practice that supports diversity is considered as pedagogy that is focused on the individual and responsive to diversity, guided by the values of communality and diversity as richness. Teachers’ self-awareness is a critical condition for diversity-responsive practice. Understanding one’s own positionality and developing a coherent professional identity are intertwined, yet distinct, aspects of self-awareness. Professional development is considered to be a combination of a development- and reflection-oriented personal stance and a dynamic orientation to the process of professional development. Professional development includes collaborative practice, self-reflection and continuous learning. The three main categories are interdependent and reinforce each other.

Student teachers’ self-assessment of diversity skills

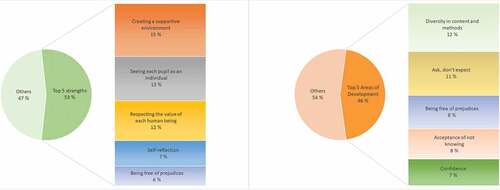

At the second stage, student teachers were asked to indicate five personal strengths and areas of development from the model provided and rank them. Total scores for strengths were 61.4% for teacher practice, 23.4% for self-awareness, and 15.2% for professional development. Areas of development were divided between teacher practice (57.1%), self-awareness (32.4%) and professional development (10.5%). Similar to the three skills categories developed from the student assignments (), the emphasis of self-assessment is strongly on teacher practice. Student teachers’ emphasis on self-awareness over professional development seems logical in the context of initial training. The most important strengths and areas of development in student teachers’ self-assessment of diversity skills are presented in .

The top-three strengths as well as the two most important areas of development identified by student teachers were related to teacher practice. One skill related to self-awareness and one related to professional development were among the top-five strengths. The top-five strengths account for 53.4% and areas of development for 43.9% of the ranking points given to all 27 skills in the self-assessment, thus presenting a rather consistent picture of the most important skills. While student teachers’ main concerns are related to pedagogical practice, getting rid of harmful pre-expectations and prejudices are central areas of development. For future and novice teachers, balancing between confidence and acceptance of not knowing presents a major challenge.

According to the findings, future teachers consider the skills related to pedagogical practice essential and thus requiring attention. While 61.4% of all evaluated strengths were to do with practice, this area was also most often pointed out as an area of development (in 57.1% of the responses). Of the 28 respondents, 20 student teachers mentioned creating a supportive environment as a strength whereas diversifying content and methods was considered a major area of development by 15 student teachers. This emphasis reflects the discussions and practices of Finnish teacher education where teaching practice and practical toolkits are often foregrounded. Beyond this, a solid value base for diversity skills can be built upon the identified strengths of seeing each pupil as an individual (18 scores given, ranked most important by five respondents) and respecting the value of each human being (13 scores given, ranked most important by six respondents). The strong presence of the respect for individual human rights in the perceived strengths allows working from a value-based orientation.

The assessment of students’ own presumptions and self-awareness created more diverse results. The most often mentioned strengths in this area were being free of prejudices and the recognition of one’s background and attitudes. In contrast, while 18 respondents considered being free of prejudices as their strength, another 13 saw it as a major area of development. Similarly, seven student teachers considered the acceptance of not knowing as a strength while eight saw it as an area requiring improvement.

I realise I am making assumptions. R11

Don’t interpret but ask! That reduces ‘automatic’ classification. R15

At times I’m just quiet and forget to ask. R18

I notice it is difficult to have the courage to ask about diversity matters, even if I wanted to. I often don’t dare to ask. I also often realise I am thinking about the challenges of diversity rather than the strengths. R13

The strong but somewhat controversial emphasis on these areas may indicate recognition of these issues as critical challenges to development as a teacher. Recognising counterproductive prejudices, avoiding assumptions and acceptance of not knowing are at the core of wise pedagogical practice.

I am aware that I don’t know and realise that I need more information. R10

At times, one unintentionally produces a certain type of culture. R12

Strengths come from understanding my own background and its hidden meanings together with self-reflection, whereas matters that need to be developed spring up from prejudices towards strange and odd things in addition to developing my self-confidence. R4

The area of developing diversity skills was least present in the self-evaluations. Self-reflection was considered a strength by 12 respondents. One student teacher mentioned her/his own readiness to learn as the strongest diversity skill. The biggest area of development was staying up to date. Although the self-evaluations were conducted towards the end of the study module on diversity, the student teachers pointed to gaps in their knowledge and awareness of diversity-related phenomena.

I see all people as being equal although the world isn’t an equal place. Through this course, I have started reflecting on these matters more. R21

‘Basic things’ still take my energy. Continuous learning of new things takes much of my capacity. R4

The self-evaluation was considered challenging by the student teachers. It is also relevant to ask whether the self-assessments reflect more the current situation of how student teachers envision themselves or their ideal professional selves in the future. Can the identified strengths and areas of development be concretely seen in (professional) practice?

Some student teachers commented on the extensive list of skills to be challenging in essence and really hard to gain during initial teacher education. The complexity of the skills and their development requires strong self-awareness and reflection on practice. If these themes are introduced to future teachers only at the end of their studies, opportunities for learning may be limited before entering working life. Feedback on the course ‘home economics in a diverse society’ has often mentioned the critical importance of the topic but that its introduction happens far too late in teacher education. The findings from this self-evaluation point to the importance of allowing time and space for practice-based reflection. Focusing on equity during teaching practice and recognition of volunteering and international experience as important learning contexts could provide additional spaces in the tightly scheduled programmes.

Attempts to recognise hidden equity structures

Reflection on the diversity skills typology and student teachers’ self-assessments with reference to Gorski’s (Gorski and Swalwell Citation2015; Gorski Citation2016b, Citation2017) equity literacy framework pointed to a gap in student teachers’ awareness of the influence of social structures on teachers’ diversity skills and practices and on teachers’ agency in working towards equity. For us, this seemed alarming because it may potentially lead to future teachers putting unrealistic expectations on their own possibilities to respond to diversity and to promote equality and equity.

A structural look into the diversity skills typology points to understanding of teacher positionality, including the skills of recognising one’s background and attitudes, and understanding one’s own culture, subjectivity and personal perception of diversity. Furthermore, the acceptance of not knowing is also strongly linked to the recognition of limited understanding of diverse positionalities. Awareness of both teachers’ and pupils’ structurally constrained agency is critical to identifying spaces for transformative practice.

As a result of the seeming absence of structural awareness beyond individual positionality in student teachers’ assignments, a third stage of the research process was carried out in 2019, with a focus on analysing the structures producing end reproducing in/equity. The analysis was done as a final stage of reporting on course projects where student teachers participated in activities of previously unknown intercultural groups. Students had either organised or participated in formal or informal events, for example in a poetry club for senior citizens and a cultural tour for women with migrant backgrounds. A reflection session was organised to discuss diversity and equity related issues observable in the activities. At the end of the session, students submitted a short written report for analysis.

In the reports, a total of 41 dimensions of difference, of which 26 visible and 15 hidden were mentioned. Twenty eight of these were related to personal identifiers (68% of the total). The visible characteristics (17) included e.g. age, sex and ethnicity, while sexual orientation and personal life situation remained obscured (9). Most projects were conducted in educational settings where student teachers had observed diversity in academic backgrounds and abilities (6 mentions). In the context of this study, this category can be considered to reflect both individual characteristics and the wider educational structure. As examples of visible, wider structures student teachers mentioned religion, social class and a pedagogical discussion where different societies were compared (3). The five structural aspects that were recognised to remain hidden in interaction included social class, inequalities in general, worldviews and realities external to the school.

The content analysis shows that students were able to differentiate the recognisable and the obscured diversities in the groups of people they interacted with. However, diversity was primarily identified through visible characteristics. This raises a concern of student teachers making assumptions based on what is visible and whether they are able to connect the personal attributes with the structural dimensions (e.g. how does the societal gender structure influence the gender identity of an individual). An equity-centred approach requires that attention is paid to recognising diversity that can result in inequality. Recognition should also lead to action to change practices preventing full participation.

Drawing on findings of the three sub-studies, we suggest that teachers’ pedagogical practices supporting equality (e.g. seeing each pupil as an individual, asking instead of expecting, creating connections with pupil’s home realities and supporting pupils’ gender identities and cultural identities) provide clear, although under-utilised links to equity structures. In line with Gorski and Swalwell (Citation2015), Gorski (Citation2017)) equity literacy approach, we argue that practices supporting equality can only arise from a structural awareness of the causes of inequality and their influence on teacher positionality and agency. Seeing students primarily as individuals rather than through the social structures (e.g. gender structure) they represent requires an understanding of the complexity of socially produced, intersectional identities. When teachers become aware of their positionalities and the resulting limitations in understanding, it may lead to actively getting rid of harmful presumptions and prejudices; moving to pupil-centred, appreciative practice that responds to diversity. Our data shows that student teachers consider themselves able and motivated to recognise and respond to learner diversity. However, a better awareness of the structures (re)producing inequity would be required to develop the ability to redress inequity and to act to create and sustain bias-free communities.

To summarise the analysis, we have complemented the tripartite typology consisting of the distinct yet interconnected skills areas by including a set of structural elements that form the societal context for education. presents a suggested equity-centred model of teachers’ diversity skills development.

Discussion

The qualitative analysis of student teachers’ assignments portrays diversity skills as a combination of self-awareness, teacher practice and professional development that develop in interaction with societal structures. The areas of development identified by student teachers reflect the challenges of responding to learner diversity expressed by beginning teachers and school principals (Harju and Niemi Citation2018). In addition to the pedagogical challenges, the student teachers focused on the self-related, attitudinal dimensions (e.g. being free of prejudges, acceptance of not knowing) that were not visible in the study by Harju and Niemi (Citation2018). Further, moving beyond the culture-focused orientation criticised by Gorski (Citation2016b), the typology developed in our study provides a dynamic, practice oriented approach to responding to diversities. In an equity-centred approach, it is critical for student teachers to develop an awareness of the structures of (in)equity and to build resources to redress inequities. Our findings reveal the challenges of identifying structural inequities through the selected pedagogical approach. This accords with previous research on the complexity of equity-centred teacher education (e.g. Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016) and reinforce previous calls for an explicit commitment to social justice (Gorski Citation2016b; Mills and Ballantyne Citation2010). In our intervention, students would have benefitted from a more thorough orientation and a multiple stage process to support unveiling the structural dimensions in their projects. Another limitation results from the small group of participants and the focus on one specific subject teacher education. These together hinder reaching a holistic understanding of student teachers’ perceptions and the potential for a more comprehensive transformation towards equity centred teacher education in Finland. In this final section, we bring our key findings in discussion with previous literature and discuss some potential spaces and ways forward for promoting an equity-centred approach in teacher education more broadly.

Working through diverse concepts during the exploratory process has demonstrated to us how the use of concepts in daily practice, curricula and in research sheds light on the various dimensions of equity literacy. The collaborative research process has helped us to move from the seemingly distinct themes of multicultural education and gender equality towards diversity and equity as the key foci of initial teacher education for diversities. The conceptual work around skills, competences and literacies has also challenged us to look into the various ways of approaching learning objectives related to diversity and equity. Navigating through the conceptual diversity present in educational discourses could also be considered part of equity literacy. A critical reading of academic texts, learning materials, curricula and policy texts could help in not letting the choice of terms and concepts obscure the equity goals of education. In line with the analysis by Mikander, Zilliacus, and Holm (Citation2018) developing a conceptual understanding and an ability to use the concepts should be a central objective of initial teacher education.

Developing and maintaining a pedagogical approach focusing on both equal access and outcomes while critiquing and challenging the intersecting systems producing inequity (see Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016) is an extremely challenging task faced by educators. Teacher education in its current form does not seem to provide the necessary sociological understanding of in/equity. The equity literacy framework has helped us to contextualise student teachers’ analysis of the basic education curricula and the diversity skills that they, as future teachers, consider critical to advancing equity. Gorski’s equity literacy framework does not highlight the collective dimension of competence development. However, our research points to the potential of the collaborative space of initial teacher education in working towards the development of equity literacy. Agreeing with Lanas (Citation2014), rather than identifying a clearly defined set of skills or competences related to education regarding diversity, we promote an approach that emphasises the thoughtfulness and reflectiveness of educators as the engine of equity-promoting education. However, collaborative work around identification and assessment of skills provided an opportunity to make some of the intangible features of diversity more concrete. Also, commonly used notions such as ‘being free of prejudices’ inspired complex discussions on their usefulness and potential harmfulness.

The findings portray initial teacher education as a potential space to work towards equity literacy. Student teachers’ assignments reflect an improved understanding of diversities through discussion of concepts, dimensions of intercultural skills, the curricula and the reflections following exposure to diverse intercultural settings (see also Posti-Ahokas, Janhonen-Abruquah, and Johnson Longfor Citation2017). In our exploratory enquiry, the work towards a model of diversity skills was based on the objectives of the Finnish curricula for basic education (NCCBE Citation2016). It would be interesting to find out what outcomes other reference bases, including teaching practice portfolios or class observations, would produce. Cochran-Smith et al. (Citation2016) and Gorski and Swalwell (Citation2015) emphasise the interconnected nature of teachers’ pedagogical practice and teachers’ critical position in being influenced by and potentially influencing societal structures. Student teachers participating in this exploratory work became increasingly aware of their own potential role in promoting equity (cf. Dervin Citation2017). In keeping with Layne and Dervin (Citation2016), instead of confirming the ideology of a homogenous society, teacher education should incorporate reflection on privilege and non-privilege as well as pedagogical activism through discussing collective knowledge and injustices. Previously suggested approaches centring on thoughtfulness (Joldersma Citation2011; Lanas Citation2014), compassion (Boylan and Woolsey Citation2015), wisdom and care (Layne and Dervin Citation2016) can only genuinely grow from an equity-oriented approach. However, current structures of teacher education, including the fragmented programme structure and resistance to theory (Gorski Citation2016a) do not necessarily support these objectives. Our findings emphasise the importance of collaboration and continued processes in developing equity literacy. The Finnish teacher education could provide more spaces for collaboration across study programmes and allow phenomenon-based approaches to be used throughout the comparatively long teacher education programmes extending to Master’s level. The work presented here could be considered an attempt to create a non-performance-oriented pedagogical relationship in teacher education (Lanas Citation2014), aiming at a profound change in outlook (Nieto Citation2000).

Initial teacher education in the Finnish context has great potential to address diversity through combining practical exposure with a more systemic perspective drawing on the interdisciplinary content of different teacher education programmes. This in itself can serve the twin goals of addressing individual needs while recognising the structural influences on education (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016). While recognising the other, often competing challenges and demands in teacher education, we argue for the importance of equity literacy as a cornerstone in the development of teacher professionalism in line with the objectives of the Finnish curricula for basic education (National Core Curriculum for Basic Education Citation2016. (NCCBE) 2016) emphasising generic, transversal skills, e.g. critical thinking, future skills and multiliteracies as well as teacher collaboration and integration across subjects (Hakala and Kujala Citation2021; Haapaniemi et al. Citation2020).

In the context of home economics (teacher) education, the discussion of skills has focused on home economics teachers’ pedagogical approaches to teaching skills needed in everyday life (e.g. Tuomi-Gröhn Citation2008). We are contributing to this discussion by suggesting that diversity skills are a critically important element of home economics pedagogy and their acquisition requires extensive learning through exposure and reflection (see also Posti-Ahokas et al. Citation2017). Although the collaboratively developed typology of intercultural skills contributed to student teachers’ understanding and supported reflection, we emphasise the importance of considering skills as complex, interconnected and therefore something that cannot be presented simply as checklists. The interactional, action-oriented space offered by home economics classes (Venäläinen Citation2010) can provide a fruitful context for recognising and actively working with diversity and thereby promoting equality. Through an equity-focused approach in initial teacher education, future home economics teachers can become professionals who are able to work towards equity by connecting learners’ home realities and classroom realities, thereby bringing about meaningful change beyond their own subject area (Dupuis Citation2017; Pendergast Citation2015).

Equity literate teachers are in a good position to influence school-level practice and student attitudes. However, it is important to consider equity as a collective aim and understand the limits to individual agency in promoting equity. According with Haapaniemi et al. (Citation2020) on the potential of integrative teaching, the curricula encouraging collaboration and integration should be recognised as a critical resource for teachers to work towards equality and equity. In Finnish educational institutions, the obligatory institutional equality and equity plans serve as a basis for development and give individual teachers an important reference and justification for equity-promoting practice (e.g. securing resources for students with specific physical/linguistic needs, developing anti-bullying and anti-racist practices, etc.). Again, competing demands and pressures in schools may push equity work to the margins. Considering equity as a key condition of quality education can help to understand its centrality.

The situationality and contextuality of equity-centred teaching raises a challenge for continued professional development of both early-career and more experienced teachers at all levels of education systems. Darleen and Pedder (Citation2011) argued that professional development for teachers is often ineffective because it concentrates on specific processes in isolation and is driven by an underlying process-product logic that fails to acknowledge that teachers’ learning is deeply embedded in their professional lives and in the working conditions of schools. When developing professional development practice to support equity literacy, it is important to consider the contextual/institutional realities (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016) but also to generate dialogue across contexts. Extending collaboration beyond a single school and enhancing the link with pre-service teacher education can bring in useful resources. The work on student teachers’ identity spaces by Boylan and Woolsey (Citation2015) highlights the dynamic aspects of teacher development. In the future, it would be interesting to work together with both pre-service and in-service teachers to understand the longitudinal aspects of the development of teachers’ equity literacy for social justice.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Elli Suninen and Rachel Troberg Foundation for funding the research project. Special thanks to the three cohorts of student teachers who collaborated in the process of developing the model of teachers’ diversity skills development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hanna Posti-Ahokas

Hanna Posti-Ahokas, PhD, Adjunct Professor, is a university lecturer at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland. Her current research on higher education focuses on internationalisation, pedagogical development and innovative approaches to global education and education for diversities. Public research profile: https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/persons/hanna-posti-ahokas.

Hille Janhonen-Abruquah

Hille Janhonen-Abruquah is a Professor in Home Economics Pedagogy at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research focuses on cultural sustainability, education for diversities and everyday life practices. Public research profile: https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/persons/hille-janhonen-abruquah.

Notes

2. A short introduction to Finnish Teacher education by the Ministry of Education and culture https://minedu.fi/documents/1410845/4150027/Teacher+education+in+Finland/57c88304-216b-41a7-ab36-7ddd4597b925

References

- Biesta, G. 2017. “The Future of Teacher Education: Evidence, Competence or Wisdom?” In A Companion to Research in Teacher Education, edited by M. A. Peters, B. Cowie, and I. Menter, 435–453. Singapore: Springer.

- Boylan, M. 2009. “Engaging with Issues of Emotionality in Mathematics Teacher Education for Social Justice.” Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education 12 (6): 427–443. doi:10.1007/s10857-009-9117-0.

- Boylan, M., and I. Woolsey. 2015. “Teacher Education for Social Justice: Mapping Identity Spaces.” Teaching and Teacher Education 46: 62–71. February. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.007.

- Brunila, K., and A. Kallioniemi. 2018. “Equality Work in Teacher Education in Finland.” Policy Futures in Education 16 (5): 539–552. doi:10.1177/1478210317725674.

- Cochran-Smith, M. 2010. “Toward a Theory of Teacher Education for Social Justice.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, edited by A. Hargreaves. Part 1-2, 445–467. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Cochran-Smith, M., F. Ell, L. Grudnoff, M. Haigh, M. Hill, and L. Ludlow. 2016. “Initial Teacher Education: What Does It Take to Put Equity at the Center?” Teaching and Teacher Education 57: 67–78. July. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.006.

- Cook‐Sather, A. 2006. “‘Change Based on What Students Say’: Preparing Teachers for a Paradoxical Model of Leadership.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 9 (4): 345–358. doi:10.1080/13603120600895437.

- Darleen, O. V., and D. Pedder. 2011. “Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 81 (3): 376–407. doi:10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Dervin, F. 2017. ““I Find It Odd that People Have to Highlight Other People’s Differences–even When There are None”: Experiential Learning and Interculturality in Teacher Education.” International Review of Education 63 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1007/s11159-017-9620-y.

- Dervin, F., R. Moloney, and A. Simpson. 2020. “Going Forward with Intercultural Competence (IC) in Teacher Education and Training.” In Intercultural Competence in the Work of Teachers: Confronting Ideologies and Practices, edited by F. Dervin, R. Moloney, and A. Simpson, 3–16. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dupuis, J. M. 2017. “How Can Home Economics Education Promote Activism for Social and Ecological Justice?” International Journal of Home Economics 10 (2): 30–39.

- Gay, G., and K. Kirkland. 2003. “Developing Cultural Critical Consciousness and Self-reflection in Preservice Teacher Education.” Theory into Practice 42 (3): 181–187. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4203_3.

- Goodwin, A. Lin, and Kelsey Darity. “Social justice teacher educators: what kind of knowing is needed?.„ Journal of Education for Teaching 45, no. 1 (2019): 63–81.

- Gorski, P. 2016a. “Making Better Multicultural and Social Justice Teacher Educators: A Qualitative Analysis of the Professional Learning and Support Needs of Multicultural Teacher Education Faculty”. Multicultural Education Review 8 (3): 139–159. doi:10.1080/2005615X.2016.1164378.

- Gorski, P. 2016b. “Rethinking the Role of “Culture” in Educational Equity: From Cultural Competence to Equity Literacy.” Multicultural Perspectives 18 (4): 221–226. doi:10.1080/15210960.2016.1228344.

- Gorski, P. 2017. Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gorski, P., and K. Swalwell. 2015. “Equity Literacy for All.” Educational Leadership 72 (6): 34–40.

- Haapaniemi, J., S. Venäläinen, A. Malin, and P. Palojoki. 2020. “Teacher Autonomy and Collaboration as Part of Integrative Teaching: Reflections on the Curriculum Approach in Finland.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 1–17. doi:10.1080/00220272.2020.1759145.

- Hakala, L., and T. Kujala. 2021. “A Touchstone of Finnish Curriculum Thought and Core Curriculum for Basic Education: Reviewing the Current Situation and Imagining the Future.” Prospects. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09533-7.

- Harju, V., and H. Niemi. 2018. “Teachers’ Changing Work and Support Needs from the Perspectives of School Leaders and Newly Qualified Teachers in the Finnish Context.” European Journal of Teacher Education 41 (5): 670–687. doi:10.1080/02619768.2018.1529754.

- Janhonen-Abruquah, H., L. Heino, S. Tammisuo, and H. Posti-Ahokas. 2017. “Adapting to Change: Building Learning Spaces in a Culturally Responsive Manner.” International Journal of Home Economics 10 (2): 40–50.

- Joldersma, C. W. 2011. “Education: Understanding, Ethics, and the Call of Justice.” Studies in Philosophy & Education 30 (5): 441–447. doi:10.1007/s11217-011-9246-7.

- Kumpulainen, K., and T. Lankinen. 2016. “Striving for Educational Equity and Excellence: Evaluation and Assessment in Finnish Basic Education.” In Miracle of Education, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 69–82. Rotterdam: Brill Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6091-811-7_5.

- Lanas, M. 2014. “Failing Intercultural Education? ‘Thoughtfulness’ in Intercultural Education for Student Teachers.” European Journal of Teacher Education 37 (2): 171–182. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2014.882310.

- Lappalainen, S., and E. Lahelma. 2016. “Subtle Discourses on Equality in the Finnish Curricula of Upper Secondary Education: Reflections of the Imagined Society.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 48 (5): 650–670. doi:10.1080/00220272.2015.1069399.

- Layne, H., and F. Dervin. 2016. “Problematizing Finland’s Pursuit of Intercultural (Kindergarten) Teacher Education.” Multicultural Education Review 8 (2): 118–134. doi:10.1080/2005615X.2016.1161290.

- Mikander, P., H. Zilliacus, and G. Holm. 2018. “Intercultural Education in Transition: Nordic Perspectives.” Education Inquiry 9 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1080/20004508.2018.1433432.

- Mills, C., and J. Ballantyne. 2010. “Pre-service Teachers’ Dispositions Towards Diversity: Arguing for a Developmental Hierarchy of Change.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 447–454. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.012.

- National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2016. Helsinki: Finnish National Board for Education.

- Niemi, H., and U. Isopahkala-Bouret. 2015. “Persistent Work for Equity and Lifelong Learning in the Finnish Educational System.” The New Educator 11 (2): 130–145. doi:10.1080/1547688X.2015.1026784.

- Nieto, S. 2000. “Placing Equity Front and Center: Some Thoughts on Transforming Teacher Education for a New Century.” Journal of Teacher Education 51 (3): 180–187. doi: 10.1177/0022487100051003004.

- Pendergast, D. 2015. “HELM–Home Economics Literacy Model: A Vision for the Field.” Victorian Journal of Home Economics 54 (1): 2–6.

- Pennington, J. L., C. H. Brock, T. Palmer, and L. Wolters. 2013. “Opportunities to Teach: Confronting the Deskilling of Teachers through the Development of Teacher Knowledge of Multiple Literacies.” Teachers and Teaching 19 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.744199.

- Posti-Ahokas, Hanna, Hille Janhonen-Abruquah, and R. Johnson Longfor. “GET OUT.„ Developing Pedagogical Practice for Extended Learning Spaces in Intercultural Education. Teoksessa T. Itkonen, & F. Dervin (toim.) Silent Partners in Multicultural Education (2017): 147–172.

- Stebbins, R. A. 2001. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications .

- Toom, A., and J. Husu. 2018. “Teacher’s Work in Changing Educational Contexts: Balancing the Role and the Person.” In The Teacher’s Role in the Changing Globalizing World. Resources and Challenges Related to the Professional Work of Teaching, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, A. Kallioniemi, and J. Lavonen, 1–9. Boston: Brill Sense.

- Trent, S. C., C. D. Kea, and O. Kevin. 2008. “Preparing Preservice Educators for Cultural Diversity: How Far Have We Come?” Exceptional Children 74 (3): 328–350. doi:10.1177/001440290807400304.

- Tuomi-Gröhn, T. 2008. “Everyday Life as a Challenging Sphere of Research: An Introduction.” In Reinventing Art of Everyday Making, edited by T. Tuomi-Gröhn, 7–24. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Turkki, K. 2015. “Envisioning Literacy to Promote Sustainable Wellbeing.” In Responsible Living Concepts, Education and Future Perspectives, edited by V. W. Thoresen, D. Doyle, J. Klein, and R. J. Didham, 151–178. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15305-6.

- Tynjälä, P., A. Virtanen, U. Klemola, E. Kostiainen, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2016. “Developing Social Competence and Other Generic Skills in Teacher Education: Applying the Model of Integrative Pedagogy.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (3): 368–387. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1171314.

- Venäläinen, S. 2010. Interaction in the Multicultural Classroom: Towards Culturally Sensitive Home Economics Education. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto.

- Venäläinen, S., J. Saarinen, P. Johnson, H. Cantell, G. Jakobsson, P. Koivisto, M. Routti, et al. 2020. “Näkymiä OPS-matkanvarrelta–Esi- Ja Perusopetuksen Opetussuunnitelmien Perusteiden 2014 Toimeenpanon Arviointi”. [Perspectives from curriculum work–Evaluation of the implementation of the national core curricula for pre-primary and basic education2014]. (Report No. 5:2020). Finnish Education Evaluation Centre (FINEEC). https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2020/01/KARVI_0520.pdfAccessed 22 March 2021.