ABSTRACT

Teacher attrition is a widely recognised problem in music education, having received increasing attention amongst preservice music student teachers over the past few decades. Yet, factors influencing their career intention remain to be fully explored. This study aimed to examine the roles of demographics, personality traits, and motivations in preservice music student teachers’ intention to become music teachers through an integrated psychological decision model. Survey data were collected from 243 preservice music student teachers and analysed using structural equation modelling. The results showed that the integrated model could explain 71% of participants’ career intention. Personality traits exhibited indirect effects through the mediating roles of intrinsic, extrinsic, and social motivations. While all motivations yielded direct effects on career intention, internship experience had a negative impact. The findings provide new insights to develop effective strategies to channel career intention amongst preservice music student teachers for different stakeholders.

Introduction

Music teacher attrition and career decision have been prevalent concerns over the past few years (Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond Citation2019; Qin and Tao Citation2021). Music teacher attrition may negatively impact students, schools, and even educational expenditure (Kersaint et al. Citation2007; Lin et al. Citation2012). On the one hand, a high music teacher attrition rate may lead to the hiring of inexperienced or unqualified music teachers, detrimentally impacting the continuity and quality of students’ music learning (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, and Carver-Thomas Citation2019). On the other, music teacher attrition is likely to result in a waste of educational investment and expenditure, including that related to recruitment, induction, and unemployment subsidies (Lin et al. Citation2012). Existing research has shown how attrition gains prominence amongst preservice music student teachers when they make post-graduation career decisions, as they may lack occupational identity and thus career intention to become music teachers (Freer and Bennett Citation2012). High attrition rates have been widely reported in countries such as China (Zhu et al. Citation2020), UK (Madigan and Kim Citation2021), USA (Kloss Citation2013), Australia (Weldon Citation2018), and Singapore (Bennett and Chong Citation2018). In light of this, the identification and understanding of the means to improve preservice music student teachers’ career intention to remain in the profession have received great attention in music education research (Ballantyne, Kerchner, and Aróstegui Citation2012; Mateos-Moreno Citation2022). However, the antecedents of career intention remain to be fully explored and deserve further examination.

Attrition amongst preservice music student teachers

Whilst previous studies have predominantly explored music teacher attrition amongst in-service music teachers (Liu Citation2021; Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, and Carver-Thomas Citation2019), fewer have examined this issue during their preservice stages (i.e. as preservice music student teachers). Although preservice music student teachers are more likely to develop a career in music teaching (Mateos-Moreno Citation2022) issues such as inadequate teacher identity (Ballantyne, Kerchner, and Aróstegui Citation2012) may play a critically deterring role. In contrast, in-service music teachers tend to establish an occupational commitment through their years of teaching experience, becoming less likely to leave the profession (Reeves and Kazelskis Citation1985). Career intention and its underlying mechanisms may thus differ between preservice and in-service teachers (Bruinsma and Jansen Citation2010). Therefore, their examination amongst preservice music student teachers may help us understand their career decisions, develop effective measures to promote the success of preservice teacher education programmes, and reduce music teacher attrition.

Factors affecting teacher attrition and career intention

Several studies within and outside the education field have shown the essential influence of demographics, personality traits, and motivations on career intention/decisions (or teacher attrition in other words) amongst in-service teachers and preservice student teachers (Hughes Citation2012; Pfarrwaller et al. Citation2022; Qin and Tao Citation2021). Previous studies have investigated key factors related to teacher attrition and career intention, including age, gender, salary, wage compensation, job stress, and family responsibilities (Farmer Citation2020; Liu Citation2021; Robison and Russell Citation2022). Personality traits may also have an indirect influence on career intention through motivations. For instance, Jugović et al. (Citation2012) used the well-known five-factor personality model to investigate the relationships between personality traits and motivational factors for career intention amongst first-year preservice teachers. They found that, whilst some personality traits (e.g. extraversion and agreeableness) could predict intrinsic motivation, agreeableness showed a positive relationship with social motivation. However, the roles of these factors amongst preservice music student teachers are yet to be fully determined. More specifically, several key points still need to be addressed before developing effective strategies to reduce attrition rates amongst preservice music student teachers.

In the first place, no systematic consensus has been reached despite the significant research on teacher attrition and its determining factors produced over the past two decades. As an example, considerable divergences in the roles of motivations, personality traits, and demographics on career intention and teacher attrition have been reported by different studies (Jugović et al. Citation2012; Perryman and Calvert Citation2020; Watt and Richardson Citation2007; Yang, Hwang, and Song Lin and Professor David Lamond Citation2014). Methodological limitations such as the lack of systematic frameworks when examining the roles of these factors may contribute to such inconsistencies. Secondly, previous studies have been mostly conducted amongst in-service teachers or preservice teachers in so-called mainstream subjects (e.g. Literature, Sciences, English, Math, Business, and Technology) (Klassen and Chiu Citation2011; Trent Citation2019), but only a few in music (Bennett and Chong Citation2018; Mateos-Moreno Citation2022). The results obtained in other subject areas might not pertain to the music field, which has unique characteristics such as long-term professional training, fewer employment opportunities, and ambiguous self-occupational identities (Freer and Bennett Citation2012). Preservice music student teachers may consider their career decisions differently from teachers in other domains. In the third place, the relationships between personality traits and career intention/decision-making might differ between countries, as personality traits are underpinned by a cultural substratum (Heine and Buchtel Citation2009). This indicates that the specific cultural setting should be considered when examining the roles of personality traits. Nevertheless, most existing research has been undertaken in Western environments with Asia clearly lagging behind. Thus, evidence-based measures extracted from a Western cultural setting might not be applicable to the Chinese context due to differences in educational policies, cultural environment, and employment markets. Lastly, whilst demographics, personality traits, and motivation might interact with each other in determining individuals’ career intention (Jugović et al. Citation2012), few studies have endeavoured to develop an integrated research framework to examine their roles in determining career intention amongst preservice music student teachers.

The purpose of this study

The purpose of the present study was to examine the role of demographics, personality traits, and motivations in preservice music student teachers’ career. To do so, an integrated psychological decision model was designed to investigate preservice music student teachers’ intention to become music teachers. We applied structural equation modelling analysis to empirically test the integrated model with survey data from 243 Chinese preservice music student teachers. Our findings could not only help us understand the effects that these factors have on preservice music student teachers’ career intention but also aid policymakers, administrators, and educators to develop effective strategies enhancing preservice music student teachers’ intention to remain in the profession and develop personalised educational interventions for the successful implementation of preservice teacher education programmes.

Theoretical foundation and hypotheses development

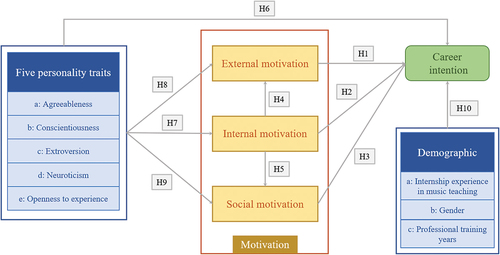

The present section introduces the background literature and the hypotheses. illustrates our proposed model based on the hypotheses.

Motivation and career intention

We introduce motivation as a theoretical psychological concept describing rationale behind our performance of, and reaction to, specific goals. Motivation theories have long been used to understand, illuminate, and predict human behaviours and behavioural intention in various settings, including educational environments (Cook and Artino Citation2016). Amongst the existing plethora of motivation theories, the intrinsic-extrinsic motivation model has been widely used to predict individuals’ behavioural intention and decisions (Vallerand and Ratelle Citation2002). This model poses that intrinsic motivation can be linked to self-driven rewards (e.g. interest, enjoyment, and inherent satisfaction), whilst extrinsic motivation pertains to behaviours leading to the attainment of external or contingent rewards (Vallerand and Ratelle Citation2002). Previous studies have showed that students’ motivation could predict and influence their career choices (Bargmann, Thiele, and Kauffeld Citation2022; Bruinsma and Jansen Citation2010). For example, preservice teachers showed a greater intrinsic motivation to stay in the profession longer (Bruinsma and Jansen Citation2010).

Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, social motivation explores the influence of social or environmental elements on human behaviours and behavioural intention, an approach that has been increasingly adopted to examine human behavioural intention in relevant literature (Hsu and Lin Citation2008). Social motivation can be identified through conformity, socialisation, peer pressure, and influence from important others (Qin and Tao Citation2021). For instance, previous evidence has shown the significant role of educators and specialists guiding students towards the adoption of a career path (Eesley and Wang Citation2017). Accordingly, when making their own career decisions, preservice music student teachers value and prefer to follow suggestions and beliefs from important others (e.g. teachers and peers), taking them as social motivation. Social motivation is thus likely to yield an effect on career intention.

In addition, previous studies indicated that intrinsic motivation could exert an impact on individuals’ behavioural intention indirectly by the roles of extrinsic and social motivation (Qin and Tao Citation2021). Moreover, intrinsically motivated preservice music student teachers are more likely to comply with beliefs from important others, usually desiring professional recognition. Thus, intrinsic motivation may impact social motivation amongst preservice music student teachers.

Thus, taking the intrinsic-extrinsic model as a basis, this study has integrated social motivation as a third necessary component to examine the role it plays in determining preservice music student teachers’ career intention. Overall, exploring the roles of motivation through such a tripartite framework would allow for a comprehensive understanding of its effects on preservice music students’ career intention. Based on the argument introduced thus far, we proposed that:

H1:

Extrinsic motivation yields a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H2:

Intrinsic motivation yields a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H3:

Social motivation yields a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H4:

Intrinsic motivation yields a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ extrinsic motivation to become music teachers.

H5:

Intrinsic motivation yields a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ social motivation to become music teachers.

Personality traits and career intention

Personality traits have been widely recognised as one of the fundamental factors related to an individual’s behavioural intention, particularly in relation to career intention/decisions (Costa and McCrae Citation1992; Farrukh et al. Citation2018). Personality traits are usually defined as a series of consistent and stable psychosocial and behavioural patterns underpinning an individual’s thoughts and behaviours (McCrae and Costa Citation2003). For example, personality traits have been related to students’ career decisions (Mullola et al. Citation2018) and used to predict job performance and satisfaction (Bui Citation2017; Yang, Hwang, and Song Lin and Professor David Lamond Citation2014). In the preservice teacher education field, researchers have explored preservice teachers’ personality traits in their early career stage, finding a significant correlation between extraversion and agreeableness and their career satisfaction (Jugović et al. Citation2012).

The widely applied Big Five Personality Model (Bui Citation2017; Farrukh et al. Citation2018; Jugović et al. Citation2012; Mullola et al. Citation2018; Yang, Hwang, and Song Lin and Professor David Lamond Citation2014) describes an individual’s personality traits through five key characteristics: extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. Its reliability and validity have been consistently verified by previous studies across a wide range of fields (Bui Citation2017; Mullola et al. Citation2018). For instance, Mullola et al. (Citation2018) suggested that four of the five traits (i.e. except neuroticism) are associated with physicians’ career intention. In contrast, Kroencke et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated a negative effect of neuroticism on career intention, given the tendency of highly neurotic individuals to focus on negative emotions. However, current findings on the roles of personality traits in preservice music student teachers’ career intention remain limited. To counter this, our research used the Big Five Personality Model to test their influence on preservice music student teachers’ intention to become music teachers. Considering previous evidence, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H6a:

Agreeableness has a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H6b:

Conscientiousness has a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H6c:

Extraversion has a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H6d:

Openness has a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H6e:

Neuroticism has a negative impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

Previous studies have also examined the influence of personality traits on motivation (Fuertes et al. Citation2020) and, more specifically, on students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Komarraju, Karau, and Schmeck Citation2009). For example, Jugović et al. (Citation2012) found that personality traits served as better predictors of intrinsic motivation, while extraversion and agreeableness proved to be the most important predictors amongst the five personality traits. Our research assumes the impact of motivation on career intention (Bargmann, Thiele, and Kauffeld Citation2022; Bruinsma and Jansen Citation2010) and posits that personality traits, through motivation, could also influence preservice music student teachers’ career intention. Taking such an approach into account, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H7:

Agreeableness (H7a), conscientiousness (H7b), extraversion (H7c), and openness to experience (H7d) have positive impacts on preservice music student teachers’ intrinsic motivation to become music teachers, whilst neuroticism (H7e) has a negative impact.

H8:

Agreeableness (H8a), conscientiousness (H8b), extraversion (H8c), and openness to experience (H8d) have positive impacts on preservice music student teachers’ extrinsic motivation to become music teachers, whilst neuroticism (H8e) has a negative impact.

H9:

Agreeableness (H9a), conscientiousness (H9b), extraversion (H9c), and openness to experience (H9d) have positive impacts on preservice music student teachers’ social motivation to become music teachers, whilst neuroticism (H9e) has a negative impact.

Demographics and career intention

Numerous studies have documented the connections between demographics and an individual’s behavioural intention and decisions through elements such as gender, educational background, experience, and age (Aburumman et al. Citation2020; Santos, Roomi, and Liñán Citation2016; Scanlan et al. Citation2019). For example, Scanlan et al. (Citation2019) found that male medical students were more likely to pursue other career opportunities than their female counterparts. Moreover, males were more likely to consider entrepreneurship as an acceptable career and showed a greater willingness to develop their entrepreneurial skills (Santos, Roomi, and Liñán Citation2016). In the music education field, prior literature has shown how preservice music teachers are highly likely to develop positive relationships with students during internship periods, develop a stronger occupational identity (Russell Citation2012), and thus further gravitate towards becoming music teachers. Similarly, sustained professional training influence preservice music teachers’ occupational identity, as their increasing identification as music professionals (e.g. musicians, singers, and performers) (Freer and Bennett Citation2012) lowers their intention to become music teachers. However, the impact of demographics on preservice music student teachers’ career intention/decisions in relation to personality traits and motivation remains unexplored. To address this, the present study selected three key demographic factors (i.e. internship experience in music teaching, years of professional training, and expertise) to explore their roles in preservice music student teachers’ career intention. The following hypotheses were proposed:

H10a:

Internship experience in music teaching has a positive impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H10b:

Gender has an impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

H10c:

Professional training has a negative impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

Methods

Participants

This study employed a self-report online questionnaire survey. Preservice music student teachers from several Chinese universities and colleges, enrolled in three- or four-year educational programmes designed to train qualified music teachers for primary and secondary education, were invited to participate. Upon graduation, these students may choose to pursue their career path (i.e. to become a music teacher) or abandon it (e.g. to find other occupations instead of teaching music). Two hundred and eighty participants (280) were invited and two hundred and fifty-five (255) filled out the questionnaire, with a response rate of 91%. We obtained 243 valid samples for data analysis after discarding eight invalid ones. summarises demographic information.

Table 1. Statistics for participants’ demographic information.

Procedures

An online questionnaire survey was sent to participants in January 2022 through Wenjuanxing, one of the main online survey companies in China. We notified participants of the collection of personal yet anonymous data, such as demographics, personality traits, and career intention. To reduce potential biased or insincere feedback, we stressed the anonymity of their responses, the need to answer the questionnaire carefully and honestly, and the confidentiality of their personal information. Participants provided informed consent when filling out the survey.

Instruments

The present study developed a questionnaire after a broad review of existing literature and consultation with music teachers and students (potential participants). Measurement scales were validated by and adopted from previous studies: three-item scales for intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and social motivation (Venkatesh and Davis Citation2000; Watt and Richardson Citation2007), respectively, and a four-item scale for career intention (Venkatesh and Davis Citation2000). We adopted Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10) (Costa and McCrae Citation1992) to measure personality traits, each dimension being measured by two items. We chose the briefer BFI-10 over other complex rating instruments (e.g. 60-item Big-Five Inventory, (Costa and McCrae Citation1992)) that are too lengthy and may thus affect data quality. A BFI-10 guarantees a good compromise between accurate measurements and participants’ time costs (Gosling et al. Citation2003), introducing an adequate framework to gather and analyse the necessary data. The widely used seven-point Likert scale was adopted to indicate participants’ responses to questionnaire items.

Cronbach’s coefficient was adopted to assess internal consistency reliability for scales with three or more items, whilst Spearman-Brown coefficient was adopted to estimate internal consistency reliability for scales with two items (Eisinga, Grotenhuis, and Pelzer Citation2013). Cronbach’s coefficient greater than 0.7 and Spearman-Brown coefficients greater than 0.45 were deemed acceptable (Thalmayer, Saucier, and Eigenhuis Citation2011). All scales showed acceptable consistency reliability, with the only exception of agreeableness (Spearman-Brown coefficient 0.184). We thus removed agreeableness from our proposed model but also conducted sensitivity analysis to check its impact on the relationships proposed in the original framework. The sources and consistency reliability for the questionnaire scales can be seen in .

Table 2. Questionnaire items and their sources in the examined model.

Once we drafted the questionnaire, we invited in-service educators (with a background in psychology) and students to provide feedback to refine its quality and validity. We provided a Chinese translation to guarantee the accuracy of item selection and the correctness of the writing and invited two bilingual specialists to back-translate it. Both English versions were compared, showing no significant differences. The questionnaire began with a brief description of the study, followed by items to collect participants’ demographic information, and by items measuring constructs in the proposed model.

Data analysis

Inter-correlations amongst major variables were assessed by bivariate correlation analyses. The measurement model was verified through the assessment of the constructs’ convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was verified by three criteria widely used in previous studies (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981): composite reliability, item reliability, and the average variance extracted (AVE) per construct. Composite reliability qualified as valid for values greater than 0.70 (DeVellis and Thorpe Citation2021). We assessed the item reliability by verifying that all items’ factor loadings were significant and larger than 0.50 (Hair et al. Citation2010). Adequate AVE value was also confirmed for values that exceeded 0.50. For discriminant validity, a larger AVE value of the square root versus all the bivariate correlations in any specific construct was verified.

The hypothesised structural model was examined with structural equation modelling (SEM) in AMOS 21, adopting maximum likelihood estimates to assess path coefficients in the examined model. Several widely used goodness-of-fit metrics were adopted to verify model-to-data fitness, including the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI ≥ 0.9), the ratio of the Chi-square statistic to the degree of freedom (χ2/d.f. < 3), the comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.9), the incremental fit index (IFI ≥ 0.9), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI ≥ 0.8), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08) (Rao, Miller, and Rao Citation2011).

Results

Correlations amongst tested variables

The correlations and means of tested variables can be seen in . Correlations amongst most variables were moderate. Both personality traits and motivation factors were significantly correlated with career intention, indicating their importance in shaping preservice music student teachers’ career intention.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of and correlations amongst the examined variables.

Measurement model results

The results showed that factor loadings and the AVE for all the constructs exceeded 0.5 and that all composite reliabilities were above 0.7 (), exhibiting adequate convergent validity. Each construct’ square root of the AVE was larger than any of its bivariate correlations (), indicating desired discriminant validity. It was thus appropriate for further assessment of the structural model.

The structural model

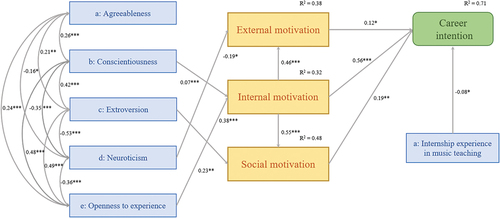

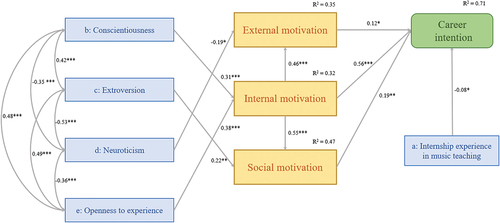

As agreeableness showed less satisfactory reliability (see ), two structural models, with and without the construct, were examined to check its impact on the relationships under examination. illustrates results with significant paths for the original model, whilst shows results from sensitivity analysis where agreeableness had been excluded from the tested model. The comparison between both showed no significant differences. This grounded our decision to remove agreeableness from the final model () reported hereinafter.

Figure 2. The model with the unqualified variable and significant standardised path coefficients. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Figure 3. The final model and significant standardised path coefficients. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The results of the goodness-of-fit metrics indicate an adequate match between the proposed model and data (χ2/d.f. = 2.41, AGFI = 0.82, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.076). includes results of hypothesis testing in the structural model. Extrinsic motivation (β = 0.13, p = 0.027), intrinsic motivation (β = 0.55, p < 0.001), and social motivation (β = 0.34, p = 0.004) positively impacted career intention, supporting H1, H2 and H3. In addition, intrinsic motivation positively influenced extrinsic motivation (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), and social motivation (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) therefore supporting H4 and H5. H6b, H6c, H6d, and H6e were not supported as all personality traits exerted no direct impact on career intention.

Table 4. Results of hypothesis testing.

Two personality dimensions (i.e. conscientiousness (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and openness (β = 0.41, p < 0.001)) yielded positive effects on intrinsic motivation (supporting H7b and H7d). Extroversion (β = 0.11, p = 0.003) had a positive impact on social motivation (supporting H9c), whilst neuroticism (β = −0.18, p = 0.010) negatively impacted extrinsic motivation (supporting H8e). No other significant relationships between personality dimensions and motivations were detected. Regarding demographics, only internship experience in music teaching (β = −0.11, p = 0.033) showed a negative impact on career intention. Therefore, H10a, H10b, and H10c were not supported.

Concerning motivations: two personality dimensions (i.e. conscientiousness and openness) contributed to 32% of the variance in intrinsic motivation, 47% of the variance in social motivation accounted for extroversion and intrinsic motivation, and 35% of the variance in extrinsic motivation was explained by neuroticism and intrinsic motivation. Overall, antecedents of personality traits, motivations, and internship experience in music teaching contributed to 71% of the variance in career intention.

Discussion

Our study proposed and examined a model aimed at understanding preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers in Mainland China. The proposed analytical framework considered the roles of key aspects such as demographics, personality traits, and motivations. Our research opens new paths to investigate key factors influencing preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

Primary findings

According to our results, the proposed model fits the analysed data and could explain 71% variance in preservice music student teachers’ intention to become music teachers, a percentage that is equal or greater to that reported by similar research (e.g. 71% by (Aburumman et al. Citation2020) and 60% by (Dunn, Hattie, and Bowles Citation2018)). Our merging of personality traits with the motivation theory framework, which enhances the integrated model’s predictability, accounts for this. Overall, the results verified the predicted roles of extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, social motivation, and music teaching internship experience on preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

In particular, intrinsic motivation was found to positively influence career intention. Such results were in line with existing studies on career and professional training intention amongst preservice teachers (Qin and Tao Citation2021; Tang et al. Citation2020) showing how the more highly intrinsically motivated preservice music student teachers choose to teach music after graduation.

Extrinsic motivation had a direct impact on career intention. This is consistent with previous research, demonstrating both the direct and indirect influence of extrinsic motivation on career intention (Oliveira, Barbeitos, and Calado Citation2021; Qin and Tao Citation2021). In our study, preservice music student teachers choose to enrol in music education programmes and to become music teachers after their graduation due to either intrinsic desired (e.g. vocational) or extrinsic appeal (e.g. high salaries or the linked social status). This reinforces Mateos-Moreno’s Citation2022, demonstrating the crucial role of external aspects (e.g. school funding, workload, and salary) in preservice music student teachers’ career concerns.

Moreover, social motivation plays a crucial role in predicting career intention. Preservice music student teachers tend to consider the suggestions of professionally qualified and recognised individuals when making career choices. Qin and Tao (Citation2021) proved that preservice music student teachers may internalise important others’ expectations as their own, a fact arguably related to the collectivist culture in China and to Chinese Confucianism. Whilst the younger generation prefers to follow family beliefs (e.g. parents and seniors) (Wang et al. Citation2016), both teachers and parents have a profound influence on the students’ decision-making (Liu and Morgan Citation2016). Moreover, since preservice music student teachers may not be prepared to make a fully informed independent decision (Dewberry and Jackson Citation2018), they are more likely to take into account suggestions from relevant others when choosing future career paths.

In addition, our research showed the direct and indirect impact of intrinsic motivation on career intention via both extrinsic and social motivations. On the one hand, it suggested that preservice music student teachers’ intrinsic motivation influences their extrinsic motivation to become music teachers. Vallerand and Ratelle (Citation2002) found that intrinsic motivation may be transformed into external motivation by an extrinsic force. In our study, most preservice music student teachers enrolled in educational programmes for intrinsic reasons. Eventually, a greater understanding of the external rewards of a teaching career led to the emergence of extrinsic motivation to choose such a career path. On the other hand, intrinsic motivation can also impact social motivation. When preservice music student teachers are intrinsically motivated to become music teachers, their desire may be reinforced by an agreement with their parents’ and teachers’ supportive suggestions, eventually taking these suggestions as their own. Thus, we argue that intrinsic, extrinsic, and social motivation coexist (Lemos and Veríssimo Citation2014) and interact to impact preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers.

Unexpectedly, our research found limited direct effects of personality traits on career intention, a finding that was inconsistent with previous research (Budaev and Brown Citation2011; Farrukh et al. Citation2018). This may be due to their lesser methodological significance in our exploration of preservice music student teachers’ career intention. Interestingly, this unexpected finding appears to support Omar and Dequan’s (Citation2020), showing the greater impact of motivational over personality traits on an individual’s behavioural intention. However, since some personality traits yielded indirect effects on career intention – through motivations – their connection remains relevant. Firstly, both openness and conscientiousness had a significant positive influence on intrinsic motivation. Our findings, consistent with previous research, suggest that preservice music student teachers with greater conscientiousness and openness are more likely to choose teaching as future career, thus conscientiousness and openness are more important predictors for intrinsic motivation amongst personality traits (Tlili et al. Citation2019). Secondly, neuroticism is a negatively influential predictor of extrinsic motivation. Highly neurotic individuals tend to focus on their negative emotions (e.g. threats and emotional pressures) paying more attention to, and being more concerned about, the potential negative consequences (Kroencke et al. Citation2020). Thus, preservice music student teachers with high neuroticism may pay greater attention to the negative ramifications of a music teaching career (e.g. workload and job stress). Thirdly, extroversion positively influences social motivation. Highly extroverted students will be more likely influenced by their parents, teachers, and relevant others. Previous studies have identified a strong link between parent-child relationships and the development of extroversion (Fonseca Citation2021), suggesting that positive and closer father-child relationships are more prone to foster extroverted personalities. Our research appears to echo this finding, highlighting the influence of important others on career intention for extroverted students.

Moreover, amongst the demographic factors, only internship experience in music teaching had an impact on preservice music student teachers’ career intention while gender and professional training years did not. Whilst we initially hypothesised the positive influence of internship experience in music teaching on career intention due to its contribution towards preservice teachers’ occupational identify (Russell Citation2012), our results countered the conclusions reached by previous studies. We argue that such a negative influence may relate to the stressful working conditions linked to low internship satisfaction, as considered by Mensah et al. (Citation2021).

Implications

The findings from this study have clear theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, they demonstrate the sufficiency and efficacy of the proposed model, based on motivation theory and personality traits, to predict and understand preservice music student teachers’ career intention to become music teachers. In particular, our research enriched previous literature by testing the impact of a comprehensive set of demographics, personality traits, and motivational elements. In addition, we have quantified the direction and magnitude of the interrelations between those factors and career intention.

On a practical level, policymakers, educators, and administrators responsible for the development of music teacher education programmes could also use our findings to advance effective measures increasing music teacher retention rates. In particular, the examination of the motivations underpinning career intention stresses the need to develop measures ensuring the adequate intrinsic motivation of preservice music student teachers and the attractiveness of the extrinsic professional rewards and benefits. This reinforces related discussions introduced in previous literature (Whitaker and Valtierra Citation2018). For example, several studies have linked music teachers’ career choices (Mateos-Moreno Citation2022) to specific external concerns (e.g. working hours, workload, and salary) that should be taken into account by policymakers in order to improve extrinsic motivation (e.g. increasing salaries, rationalising work hours, promoting the legitimacy of music as a subject). Whilst previous studies explored the significance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, our findings revealed the tantamount role of social motivation in the implementation of educational programmes for music teacher students. In view of this, educators should engage important others (e.g. parents and previous teachers) in the advertisement of educational programmes and obtain their recognition and support to recommend music teaching as a future career.

In addition, we should also value the significance of preservice music student teachers’ personality traits, which should be examined in detail by administrators and educators when enrolling new students into preservice music teacher education programmes. Moreover, educators should design teaching activities and course contents aimed at cultivating enrolled students’ conscientiousness and openness personalities, as these will impact intrinsic motivation and career intention. Educators should also convey their own experiences to students as this could be a highly influential social motivational tool impacting career intention. Overall, policymakers should optimally allocate educational resources in preservice music student teachers’ educational programmes according to the diverse roles of antecedents of career intention to decrease teacher attrition rates.

Limitations

Whilst our study represents a significant contribution to music education, we acknowledge its limitations and argue that they could and should be addressed in future research. In the first place, whilst we obtained a statistically adequate sample size (243), according to widely recognised rules of thumb for SEM sample size determination (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2011; Kline Citation2015; Weston and Gore Citation2006), its representativeness of China’s total population remains questionable. As such, our research could be seen as a pilot study providing a framework for future large-scale research involving participants from a greater range of universities and regions, increasing the representativeness of sample size and allowing us to draw more solidly-grounded conclusions. Secondly, our participants were limited to preservice music student teachers from Mainland China. Future studies could incorporate samples from different cultural backgrounds and other types of preservice music teacher education programmes. Thirdly, a longitudinal study would be necessary to clarify the contradiction between our examination of the direct influence of extrinsic motivation on career intention and previous research (Qin and Tao Citation2021). One potential explanation would be that extrinsic motivation may only elicit temporary compliance with an individual’s behavioural intention (Olatokun and Irene Nwafor Citation2012). Finally, as an arguable result of the limited sample and questionnaire items, one of the personality traits (i.e. agreeableness) did not pass our item reliability test: a long instrument with further items would be thus required to assess personality traits.

Conclusions

Our study proposed and tested an integrated psychological decision model to understand preservice music student teachers’ intention to become music teachers after graduation. The results indicated the sufficiency and efficacy of the proposed model, helping us identify several important antecedents of career intention, such as all three motivation types (e.g. intrinsic, extrinsic, and social motivation), for preservice music student teachers. Our findings could help policymakers, administrators, and educators develop more attractive strategies and policies for the analysed demographics. In addition, this pilot investigation could work as the basis for future research exploring the changing roles of the examined antecedents in career intention amongst preservice music student teachers through a longitudinal approach involving different socio-cultural contexts.

Ethics Declarations

After consultation with the local ethics committee, ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it is just a subjective evaluation not involving any potentially harmful experimentation. However, we adhered to the ethical standards of informed consent, confidentiality, and anonymity (informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to filling out the survey), and the data were collected anonymously and securely stored.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mingfu Qin

Mingfu Qin is a PhD: Her research interests lie in music education

Roberto Alonso Trillo

Roberto Alonso Trillo: He has research interests covering areas relating to music education.

References

- Aburumman, O., A. Salleh, K. Omar, and M. Abadi. 2020. “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices and Career Satisfaction on Employee’s Turnover Intention.” Management Science Letters 10 (3): 641–652. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.9.015.

- Ballantyne, J., J. L. Kerchner, and J. L. Aróstegui. 2012. “Developing Music Teacher Identities: An International Multi-Site Study.” International Journal of Music Education 30 (3): 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761411433720.

- Bargmann, C., L. Thiele, and S. Kauffeld. 2022. “Motivation Matters: Predicting students’ Career Decidedness and Intention to Drop Out After the First Year in Higher Education.” Higher Education 83 (4): 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00707-6.

- Bennett, D., and E. K. Chong. 2018. “Singaporean Pre-Service Music teachers’ Identities, Motivations and Career Intentions.” International Journal of Music Education 36 (1): 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761417703780.

- Bruinsma, M., and E. P. Jansen. 2010. “Is the Motivation to Become a Teacher Related to Pre‐Service teachers’ Intentions to Remain in the Profession?” European Journal of Teacher Education 33 (2): 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760903512927.

- Budaev, S., and C. Brown. 2011. “Personality traits and behaviour.” In Fish Cognition and Behavior, edited by C. Brown, K. Laland, and J. Krause, 135–165. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Bui, H. T. 2017. “Big Five Personality Traits and Job Satisfaction: Evidence from a National Sample.” Journal of General Management 42 (3): 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306307016687990.

- Carver-Thomas, D., and L. Darling-Hammond. 2019. “The Trouble with Teacher Turnover: How Teacher Attrition Affects Students and Schools.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 27:1–32. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3699.

- Cook, D. A., and A. R. Artino Jr. 2016. “Motivation to Learn: An Overview of Contemporary Theories.” Medical Education 50 (10): 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13074.

- Costa, P. T., and R. R. McCrae. 1992. NEO PI-R: Professional Manual: Revised NEO PI-R and NEO-FFI. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

- DeVellis, R. F., and C. T. Thorpe. 2021. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Los Angeles: Sage publications.

- Dewberry, C., and D. J. Jackson. 2018. “An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Student Retention.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 107:100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.005.

- Dunn, R., J. Hattie, and T. Bowles. 2018. “Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explore teachers’ Intentions to Engage in Ongoing Teacher Professional Learning.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 59:288–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.10.001.

- Eesley, C., and Y. Wang. 2017. “Social Influence in Career Choice: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment on Entrepreneurial Mentorship.” Research Policy 46 (3): 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.01.010.

- Eisinga, R., M. Te Grotenhuis, and B. Pelzer. 2013. “The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown?” International Journal of Public Health 58 (4): 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3.

- Farmer, D. 2020. “Teacher Attrition: The Impacts of Stress.” Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin 87 (1): 41–50.

- Farrukh, M., Y. Alzubi, I. A. Shahzad, A. Waheed, and N. Kanwal. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of Personality Traits in Perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour.” Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 120 (3): 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-01-2018-0004.

- Fonseca, C. 2021. Quiet Kids: Help Your Introverted Child Succeed in an Extroverted World. Austin, TX: Prufrock Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003237426.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Freer, P. K., and D. Bennett. 2012. “Developing Musical and Educational Identities in University Music Students.” Music Education Research 14 (3): 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2012.712507.

- Fuertes, A. M. D. C., J. BlancoFernández, M. ª. García Mata, A. Rebaque Gómez, and R. G. Pascual. 2020. “Relationship Between Personality and Academic Motivation in Education Degrees Students.” Education Sciences 10 (11): 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110327.

- Gosling, S. D., P. J. Rentfrow, and W. B. Swann Jr. 2003. “A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains.” Journal of Research in Personality 37 (6): 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

- Hair, J. F. J., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, R. E. Anderson, and R. L. Tatham. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet.” Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice 19 (2): 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202.

- Heine, S. J., and E. E. Buchtel. 2009. “Personality: The Universal and the Culturally Specific.” Annual Review of Psychology 60 (1): 369–394. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163655.

- Hsu, C.-L., and J.-C.-C. Lin. 2008. “Acceptance of Blog Usage: The Roles of Technology Acceptance, Social Influence and Knowledge Sharing Motivation.” Information & Management 45 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.11.001.

- Hughes, G. D. 2012. “Teacher Retention: Teacher Characteristics, School Characteristics, Organizational Characteristics, and Teacher Efficacy.” The Journal of Educational Research 105 (4): 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2011.584922.

- Jugović, I., I. Marušić, T. Pavin Ivanec, and V. Vizek Vidović. 2012. “Motivation and Personality of Preservice Teachers in Croatia.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 40 (3): 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.700044.

- Kersaint, G., J. Lewis, R. Potter, and G. Meisels. 2007. “Why Teachers Leave: Factors That Influence Retention and Resignation.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (6): 775–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.12.004.

- Klassen, R. M., and M. Ming Chiu. 2011. “The Occupational Commitment and Intention to Quit of Practicing and Pre-Service Teachers: Influence of Self-Efficacy, Job Stress, and Teaching Context.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (2): 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002.

- Kline, R. B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford publications.

- Kloss, T. E. 2013. “High School Band students’ Perspectives of Teacher Turnover.” Research and Issues in Music Education 11 (1): 15–39.

- Komarraju, M., S. J. Karau, and R. R. Schmeck. 2009. “Role of the Big Five Personality Traits in Predicting College students’ Academic Motivation and Achievement.” Learning and Individual Differences 19 (1): 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.07.001.

- Kroencke, L., K. Geukes, T. Utesch, N. Kuper, and M. D. Back. 2020. “Neuroticism and Emotional Risk During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Research in Personality 89:104038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038.

- Lemos, M. S., and L. Veríssimo. 2014. “The Relationships Between Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, and Achievement, Along Elementary School.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 112:930–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1251.

- Lin, E., Q. Shi, J. Wang, S. Zhang, and L. Hui. 2012. “Initial Motivations for Teaching: Comparison Between Preservice Teachers in the United States and China.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 40 (3): 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.700047.

- Liu, J. 2021. “Exploring Teacher Attrition in Urban China Through Interplay of Wages and Well-Being.” Education and Urban Society 53 (7): 807–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124520958410.

- Liu, D., and W. John Morgan. 2016. “Students’ Decision-Making About Postgraduate Education at G University in China: The Main Factors and the Role of Family and of Teachers.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 25 (2): 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0265-y.

- Madigan, D. J., and L. E. Kim. 2021. “Towards an Understanding of Teacher Attrition: A Meta-Analysis of Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and teachers’ Intentions to Quit.” Teaching and Teacher Education 105:103425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103425.

- Mateos-Moreno, D. 2022. “Why (Not) Be a Music Teacher? Exploring Pre-Service Music teachers’ Sources of Concern Regarding Their Future Profession.” International Journal of Music Education 40 (4): 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614211073138.

- McCrae, R. R., and P. T. Costa. 2003. Personality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory Perspective. New York: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203428412.

- Mensah, C., E. M. Azila-Gbettor, M. Enyonam Appietu, and J. Semefa Agbodza. 2021. “Internship Work-Related Stress: A Comparative Study Between Hospitality and Marketing Students.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education 33 (1): 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10963758.2020.1726769.

- Mullola, S., C. Hakulinen, J. Presseau, D. Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, M. Jokela, T. Hintsa, and M. Elovainio. 2018. “Personality Traits and Career Choices Among Physicians in Finland: Employment Sector, Clinical Patient Contact, Specialty and Change of Specialty.” BMC Medical Education 18 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1155-9.

- Olatokun, W., and C. Irene Nwafor. 2012. “The Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation on Knowledge Sharing Intentions of Civil Servants in Ebonyi State, Nigeria.” Information Development 28 (3): 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666912438567.

- Oliveira, T., I. Barbeitos, and A. Calado. 2021. “The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations in Sharing Economy Post-Adoption.” Information Technology & People 35 (1): 165–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2020-0007.

- Omar, B., and W. Dequan. 2020. “Watch, Share or Create: The Influence of Personality Traits and User Motivation on TikTok Mobile Video Usage.” International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies 14 (4): 121–137. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i04.12429.

- Perryman, J., and G. Calvert. 2020. “What Motivates People to Teach, and Why Do They Leave? Accountability, Performativity and Teacher Retention.” British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417.

- Pfarrwaller, E., L. Voirol, G. Piumatti, M. Karemera, J. Sommer, M. W. Gerbase, S. Guerrier, and A. Baroffio. 2022. “Students’ Intentions to Practice Primary Care are Associated with Their Motives to Become Doctors: A Longitudinal Study.” BMC Medical Education 22 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03091-y.

- Qin, M., and D. Tao. 2021. “Understanding Preservice Music teachers’ Intention to Remain in the Profession: An Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Motivation Theory.” International Journal of Music Education 39 (4): 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761420963149.

- Rao, C. R., J. P. Miller, and D. C. Rao. 2011. Essential Statistical Methods for Medical Statistics. Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Reeves, C. K., and R. Kazelskis. 1985. “Concerns of Preservice and Inservice Teachers.” The Journal of Educational Research 78 (5): 267–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1985.10885614.

- Robison, T., and J. A. Russell. 2022. “Factors Impacting Elementary General Music teachers’ Career Decisions: Systemic Issues of Student Race, Teacher Support, and Family.” Journal of Research in Music Education 69 (4): 425–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429421994898.

- Russell, J. A. 2012. “The Occupational Identity of In-Service Secondary Music Educators: Formative Interpersonal Interactions and Activities.” Journal of Research in Music Education 60 (2): 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429412445208.

- Santos, F. J., M. A. Roomi, and F. Liñán. 2016. “About Gender Differences and the Social Environment in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Journal of Small Business Management 54 (1): 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12129.

- Scanlan, G. M., J. Cleland, S. A. Stirling, K. Walker, and P. Johnston. 2019. “Does Initial Postgraduate Career Intention and Social Demographics Predict Perceived Career Behaviour? A National Cross-Sectional Survey of UK Postgraduate Doctors.” British Medical Journal Open 9 (8): e026444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026444.

- Sutcher, L., L. Darling-Hammond, and D. Carver-Thomas. 2019. “Understanding Teacher Shortages: An Analysis of Teacher Supply and Demand in the United States.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 27 (35): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3696.

- Tang, S. Y., A. K. Wong, D. D. Li, and M. M. Cheng. 2020. “Millennial Generation Preservice teachers’ Intrinsic Motivation to Become a Teacher, Professional Learning and Professional Competence.” Teaching and Teacher Education 96:103180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103180.

- Thalmayer, A. G., G. Saucier, and A. Eigenhuis. 2011. “Comparative Validity of Brief to Medium-Length Big Five and Big Six Personality Questionnaires.” Psychological Assessment 23 (4): 995. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024165.

- Tlili, A., M. Denden, F. Essalmi, M. Jemni, R. Huang, and T.W. Chang. 2019. “Personality Effects on students’ Intrinsic Motivation in a Gamified Learning Environment.”In Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Maceió, Brazil, 100–102.

- Trent, J. 2019. “Why Some Graduating Teachers Choose Not to Teach: Teacher Attrition and the Discourse-Practice Gap in Becoming a Teacher.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 47 (5): 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1555791.

- Vallerand, R. J., and C. F. Ratelle. 2002. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: A Hierarchical Model.” In Handbook of Self-Determination Research, edited by E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan, 37–63. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Venkatesh, V., and F. D. Davis. 2000. “A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies.” Management Science 46 (2): 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926.

- Wang, S., J. Fan, D. Zhao, S. Yang, and F. Yuanguang. 2016. “Predicting consumers’ Intention to Adopt Hybrid Electric Vehicles: Using an Extended Version of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model.” Transportation 43 (1): 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9567-9.

- Watt, H. M., and P. W. Richardson. 2007. “Motivational Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice: Development and Validation of the FIT-Choice Scale.” The Journal of Experimental Education 75 (3): 167–202. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.167-202.

- Weldon, P. 2018. “Early Career Teacher Attrition in Australia: Evidence, Definition, Classification and Measurement.” Australian Journal of Education 62 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944117752478.

- Weston, R., and P. A. Gore Jr. 2006. “A Brief Guide to Structural Equation Modeling.” The Counseling Psychologist 34 (5): 719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345.

- Whitaker, M. C., and K. M. Valtierra. 2018. “Enhancing Preservice teachers’ Motivation to Teach Diverse Learners.” Teaching and Teacher Education 73:171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.004.

- Yang, C.-L., M. Hwang, and P. Song Lin and Professor David Lamond. 2014. “Personality Traits and Simultaneous Reciprocal Influences Between Job Performance and Job Satisfaction.” Chinese Management Studies 8 (1): 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-09-2011-0079.

- Zhu, G., M. Rice, H. Rivera, J. Mena, and A. Van Der Want. 2020. “‘I Did Not Feel Any Passion for My teaching’: A Narrative Inquiry of Beginning Teacher Attrition in China.” Cambridge Journal of Education 50 (6): 771–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1773763.