ABSTRACT

Studies on teacher practitioner research suggest that experts can provide valuable guidance by modelling the research process within the school context. As it is unknown when and how modelling can promote teachers’ research, the present study evaluated several modelling practices in four teacher teams (N = 38). Two facilitators modelled research skills before, during and after teachers’ research tasks; a research disposition was modelled by questioning research decisions. Results showed that modelling was valuable for practitioner research: teachers appreciated the guidance and felt their research skills and research disposition had improved. Modelling of research skills during the task was deemed easier to comprehend than modelling before and after the tasks. Modelling of a research disposition can bring about tensions that – mainly in the initial stages of the research – cause frustrations in teachers. Based on these findings, directions for improving modelling are discussed.

Introduction

In the last decades, teacher professional development initiatives have mainly been offered as short-term, out-of-school workshops that address a specific topic (Kennedy Citation2005). Although these types of professional development activities can successfully increase teachers’ knowledge and skills (e.g. Hondrich et al. Citation2016; Kurniawati et al. Citation2017), the impact on classroom practice is low (Borko Citation2004; Smith and Gillespie Citation2007). These reservations caused a reconsideration of teacher professional development programmes and instigated a wealth of research that explored alternative ways to better support in-service teachers. The outcomes of these studies point to a number of factors that contribute to successful teacher professional development. A longer time span and more contact hours, programme coherence, collaboration and a focus on student learning have all been shown to positively influence professional development (Desimone Citation2009; Garet et al. Citation2001; Hubers, Endedijk, and Van Veen Citation2020). The design of the programme should actively engage teachers in the learning process and enable them to connect the training content to their teaching (Garet et al. Citation2001; Hubers, Endedijk, and Van Veen Citation2020; van Driel et al. Citation2012). Addressing teachers’ self-identified questions further ensures that teachers feel like agents of their own professional development, which, in turn, results in more meaningful learning (Merchie et al. Citation2018).

These conditions are generally met in professional development programmes that address practitioner research. This research genre comprises several forms of research, such as action research, self-study and participatory research. In all these cases the research is performed by professionals who aim to produce knowledge for their local context by intentionally and systematically investigating their own professional practice (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2009; Hilda, Liston, and Whitcomb Citation2007). Within the school context, practitioner research gives teachers the opportunity to investigate their classroom practices in professional learning communities (Stoll et al. Citation2006), use the results as input for school improvement (Timperley, Parr, and Bertanees Citation2009) and reflect on gained research experiences in light of further professionalisation (Kennedy Citation2005). However, these affordances apply only if teachers are adequately supported in developing the required research skills and research disposition to successfully perform practitioner research.

According to reviews on professional development, facilitators have a determinate influence on what teachers actually ‘take home’ from professional development initiatives (Merchie et al. Citation2018; van Driel et al. Citation2012). Good facilitators abide by the aforementioned contextual factors: they encourage teachers to actively develop and apply knowledge, and at the same time make them feel in charge of their own professional development. An equally important success factor concerns the expertise facilitators bring to the plate. They have to be knowledgeable about the topic under consideration and should be able to share their expert knowledge (van Driel et al. Citation2012). In case of practitioner research, educational scientists could act as facilitators because of their proficiency in conducting research in schools. Studies investigating university-school partnerships have shown that the input of academic researchers can enhance the quality of the research conducted by teachers (Schenke et al. Citation2016, Citation2017). However, as these studies focused on institutional collaboration instead of teacher professional development, questions remain regarding how researchers can best guide teachers in learning to perform practitioner research.

The current study addressed this question by examining how educational researchers can use modelling as a means to facilitate the professional development of teachers willing to extend their expertise in doing practitioner research. Modelling is the purposeful demonstration of skills needed to perform tasks that are beyond the learners’ current capabilities, and has shown to be a valuable means to support pre-service and in-service teachers’ learning about teaching (e.g. Glazer and Hannafin Citation2006; Hogg and Yates Citation2013; Lunenberg, Korthagen, and Swennen Citation2007). Not yet known is when and how modelling should be applied to promote teachers’ learning about practitioner research. To address this paucity in the research, we designed modelling practices aimed at supporting teachers in learning to perform practitioner research. These practices were based on existing theories of problem solving in complex cognitive tasks, which are elaborated in the sections below.

Guiding teacher professional development

Theories of problem solving in complex tasks often refer to tailor-made guidance as ‘scaffolding’. According to Wood, Bruner, and Ross, who coined this term, scaffolding involves ‘controlling those elements of the task that are initially beyond the learner’s capacity’ (1976, 90). This can be done by carrying out difficult task elements and offering hints on what to do next. In line with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) notion of the zone of proximal development, scaffolding ensures that learners can meaningfully engage in the elements that are within their range of competence and develop a conceptual model of the task as a whole (Collins, Brown, and Holum Citation1991; van Merrienboer et al. Citation2003; Wood, Bruner, and Gail Citation1976). Such guidance seems appropriate for practitioner research as teachers need support in planning and processing the research steps (Poekert Citation2011; Ponte Citation2002) and benefit from facilitators who carry out (part of) the more difficult research tasks (e.g. Koutselini Citation2008; Schenke et al. Citation2017).

However, when facilitators take over certain tasks, they essentially reduce the chance that teachers will learn to perform these tasks themselves (Pea Citation2004). Modelling aims to alleviate these possible detrimental effects by offering teachers the opportunity to observe and reflect on the research tasks performed by the facilitator. This type of guidance stems originally from informal learning in the workplace where an expert purposefully shows how to carry out a task and the apprentice observes and imitates the demonstrated act (Collins, Brown, and Holum Citation1991). When these tasks involve cognitive processes such as reasoning or decision making, modelling should go beyond a mere physical demonstration of a task. Such cognitive modelling should include an overt account of the expert’s thinking process (Collins, Brown, and Holum Citation1991; Jonassen Citation1999).

In the context of teacher learning, modelling has mainly been investigated in teacher education. The goal of modelling in this field is to make the relationship between teacher educators’ knowledge and actions more accessible. To accomplish this, teacher educators should not only model what they do, but also articulate their pedagogical reasoning through thinking aloud and discussion—i.e. cognitive modelling (Loughran and Berry Citation2005; Loughran, Stephen, and Rebecca Citation2016). Research has shown that teacher educators are capable of modelling their own actions, but that the pedagogical reasoning underlying these actions remains largely implicit (Lunenberg, Korthagen, and Swennen Citation2007; Montenegro Citation2020). Teacher educators who deliberately tried to model their reasoning, acknowledged that it is difficult to accomplish due to the articulation of their tacit knowledge and experience (Berry Citation2007; Hogg and Yates Citation2013; Loughran, Stephen, and Rebecca Citation2016). Like in many expert practices, teaching expertise increases on the job by informal learning through individual experiences within specific job contexts (Sternberg and Horvath Citation1995). As teachers are generally not aware of this inert knowledge, explicating such knowledge is difficult. However, in cases where teacher educators actively prepared, discussed and reflected on how to explicitly model their thought processes, cognitive modelling was a powerful means to help teachers become aware of the pedagogical decision-making process in the classroom (Hogg and Yates Citation2013; Loughran and Berry Citation2005).

Less is known about how cognitive modelling can be applied in the context of learning practitioner research. The act of doing research is a complex cognitive task that might lend itself well for cognitive modelling. Essential research skills include both overt actions, such as collecting data, and covert thinking processes that mostly involve decision making through inductive and deductive reasoning (e.g. which analysis technique best matches the research design and hypotheses?). Experienced researchers, in addition, critically consider the decisions made throughout an inquiry. This inclination is indicative of a research disposition, which is considered a cognitive process in itself that cannot readily be observed either (Cochran-Smith and Landy Lytle Citation1993; Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2009; Van der Rijst Citation2008; Zwart, Smit, and Admiraal Citation2015). A few studies investigated the use of modelling to guide teachers’ research skills and research disposition. Marsh and Farrell (Citation2015) studied the modelling of research skills in the context of school capacity building and illustrated how school leaders explicitly modelled their thoughts and actions on the use of school data. Modelling of a research disposition was pivotal to the study by Ponte (Citation2002) where teacher educators questioned research decisions so as to assist teachers in thinking about how and why their research was carried out.

Although the studies above exemplify that facilitators can apply modelling in the context of teacher practitioner research, teachers’ appraisal of these modelling practices and when and how they are applied is yet unknown. Whether modelling contributes to teachers’ research skills, dispositions and their future intentions to use research in school is equally unknown. Both issues were examined in the present study.

The present study

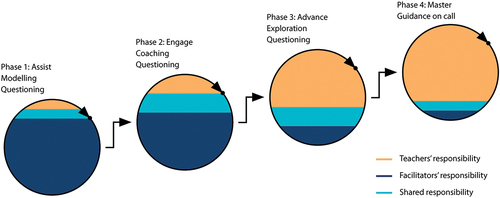

This research is part of a larger project where teachers from a large primary school worked together with two university researchers to learn to perform practitioner research. The professional development initiative was requested by the school. It was on-site, took place in the context of professional learning communities already established within the school, and addressed teachers’ self-identified issues encountered in practice. The underlying scientific goal of this project was to develop, test and evaluate a teacher guidance model. depicts the initial version of this model, which was derived from the literature review presented above and insights gleaned from related research on teacher professional development (Collins, Brown, and Holum Citation1991; Glazer and Hannafin Citation2006). Each of the four model phases comprises a full empirical cycle that runs from orientation on research topics through formulating research questions and planning the research, data collection and analyses, to drawing conclusions. Throughout the four phases the responsibility for the research gradually shifts from the facilitators to the teachers.

The current study focused on the first phase of the teacher guidance model, where facilitators were responsible for the lion’s share of the research and modelled a full research cycle. Facilitators modelled their practice by demonstrating observable tasks and articulating how decisions are made (i.e. modelling of research skills) and by displaying their propensity to pose critical questions about decisions made (i.e. modelling of a research disposition). The study evaluated the use and usefulness of both types of modelling from the perspective of the participating teachers and the facilitators. Specifically, the study aimed to find out:

how teachers and facilitators evaluate the modelling of research skills and dispositions during practitioner research, and

to what extent teachers’ views on their research skills, research disposition and use of research in school change after conducting guided practitioner research.

The first research question was answered by analysing recordings of focus group interviews held at the end of the study as well as the facilitators’ field notes from observations during and reflections after the meetings. Answers to the second research question came from teacher surveys administered before and after the practitioner research was conducted.

Materials and method

Participants and research setting

This study took place at a large public primary school in the Netherlands with over 600 pupils. The school, established in 2001, is located in a sub-urban community of above-average socio-economic status. The school is housed in a building with several neighbourhood facilities, such as a community centre, day-care, youth centre and a library. The school consists of six ‘units’. In every unit a team of 5–6 teachers serves approximately 100 pupils (kindergarten till sixth grade).

The school has a strong learning culture. Like other Dutch schools, teachers receive two hours per week for professional development and spent about seven days per year on seminars or courses on-site or off site. Additionally, in this school teachers’ day-to-day work is organised in teaching teams in which they collaboratively prepare, teach and evaluate their teaching. For cross-curricular innovations teachers collaborate in professional learning communities. These learning communities are thematically organised around school subjects and participating teachers discuss, prepare, and reflect on innovative practices. In these professional learning communities teachers have also attempted to conduct practitioner research. Up until now these attempts were unsuccessful because teachers experienced difficulties in setting up an investigation to explore their practice. The school principal and teaching staff therefore requested guidance in performing practitioner research.

This study was organised as a whole-school professional development initiative. Thirty-eight of the 48 teachers took part in the study: 35 females and 3 males with a mean age of 41.84 years (SD = 10.46). The remaining 10 teachers could not participate for personal reasons such as maternity leave or health issues. Participating teachers volunteered for the study and signed an informed consent form. The teachers received compensatory hours for the time they invested in the practitioner research. Most participating teachers had a bachelor’s degree (n = 26) or master’s degree (n = 8) in higher vocational education while some owned an academic master’s degree (n = 4). Participants’ teaching experience ranged from 2 to 39 years (M = 15.50, SD = 8.86). Most teachers had never done research before (n = 29), while nine teachers had some basic research experience, which was mainly acquired during their bachelor’s or master’s thesis work and on some occasions by participating in research projects in professional development initiatives. Teachers were grouped in four teams (7–11 teachers per team) based on existing professional communities and availability. Each team consisted of teachers from every unit so as to ensure that the practitioner research studies would be actively shared throughout the school and within each unit.

The first and second author were participatory observers; they took on the role of facilitator and guided two teacher teams each. Noortje guided team 1 and 3, and Amber team 2 and 4. Both authors have a master’s degree in educational sciences and obtained their PhD in educational research. The third and fourth author (educational researchers with over 20 years of research experience) assisted the facilitators in the first three meetings and provided further assistance during discussions in between meetings.

Procedure and measures

Professional development programme

Each teacher team investigated a self-chosen topic in two-and-a-half months. Topics chosen by the teacher teams were: peer feedback (team 1), student autonomy (team 2), student motivation (team 3), and teacher views on the school’s core values (team 4). The teams and their facilitator met during five meetings that followed the steps of the research cycle. offers an overview of these meetings, their duration, attendance, research tasks and the facilitators’ modelling activities.

Table 1. Overview of the modelling of research skills offered during the practitioner research study.

Teachers received a handbook about educational practitioner research (Stokking Citation2015) and a planning of the meetings. During every meeting a general timeline and a description of the meeting’s research tasks were offered on paper. The facilitators and teachers started each meeting by summarising the previous meeting and introducing the tasks of the current meeting; they closed the meeting by summarising the decisions made and previewing the next meeting.

The facilitators modelled their research skills by explicating their thoughts and actions regarding specific research tasks. When possible, good practice examples were used to support the modelling process. These examples came from the facilitators’ own work and illustrated how research tasks could be performed. For example, facilitators modelled how to use a research plan. They demonstrated a partly worked-out research plan, and filled out the rest of the plan together with the teachers. Additionally, sample materials were offered for specific research tasks, such as exemplary instruments and data analysis methods.

Research skills were modelled in every meeting. In absence of any validated framework on the timing of modelling, we opted for modelling at three generic moments: before, during and after a research task. Modelling before a task previewed possible decisions and their consequences so teachers would start a research task well-informed. For example, the facilitators modelled the selection of a research design (e.g. use of descriptive data in interviews or numerical data in multiple choice tests) and asked teachers to consider which design would match their research question. Modelling during a task was generally short and focused on specific subtasks so teachers could immediately put the modelled skills in practice. A typical example occurred during the data analysis meeting. Teachers were preparing their raw data for analysis and when they proposed to divide student work for grading, the facilitator intervened. She introduced the concept of interrater agreement, its relevance in grading the specific student materials, and demonstrated how to compare grades to ensure reliability. Finally, modelling after a task served to explain the tasks facilitators carried out in between meetings. These included time-consuming and complex activities and their modelling involved a high level of input by the facilitators. For example, to model the search for scientific literature – which the facilitators did between the first and second meeting – facilitators articulated their decisions made at every step of the search process. They also presented guidelines for searching for literature and a synopsis of the literature found.

Modelling of a research disposition occurred at key moments during all five meetings. Facilitators questioned the choices made in order to make teachers aware of their decisions and encourage them to consider whether these decisions were appropriate for the research. During the first three meetings, the third and fourth author acted as critical friends in questioning the research decisions. A good illustration of facilitators’ research disposition was when teachers developed their research instruments. Facilitators questioned how teachers would apply the instrument in practice (and why) and to what extent the expected data could be used to answer the research question. The teachers and facilitator discussed the final instrument with their critical friend, who asked additional questions to further ensure the validity of the research instrument.

To make sure the facilitators’ implicit knowledge was sufficiently explicated, they collaboratively prepared each meeting and thoroughly discussed how they would model their research skills and dispositions. They additionally discussed how to align their guidance, so as to ensure that they would model similarly.

Focus group interviews

At the end of the professional development programme, focus group interviews were held with each teacher team. These semi-structured interviews addressed five topics: planning of the research study, teamwork, agency, motivation and guidance. This study focused on the last topic of the focus group interview: teachers’ evaluation of the facilitators’ guidance. To gain insight in teachers’ views and justifications, the facilitator asked (follow up) questions about each topic and encouraged teachers to elaborate on or counter each other’s ideas (Morgan Citation1996).

Recordings of the focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by the first and second author using a stepwise approach (see Bertrand, Brown, and Ward Citation1992). First, all focus group interviews were thoroughly read by the facilitator who conducted the focus group interview. Using an open coding procedure, the facilitator characterised each response in a few keywords. Based on both the coding and the original response, the first author performed axial coding by assigning the responses to specific themes and subthemes. The construction of themes started from our theoretical framework, where we made a distinction between modelling of research skills (i.e. explicating research tasks) and modelling of a research disposition (i.e. questioning decisions made during the research). Based on the way guidance was offered by the facilitators modelling of research skills was divided into three subthemes: modelling before a task, during a task, and after a task. During the coding process additional themes and subthemes were distinguished. All responses in each theme and subtheme were shared with the second author. Differences were discussed and – when needed – further discussed with the third author until agreement was reached. This discussion served to check for interpretation errors and identify additional themes.

The final set of themes and subthemes can be found in . Our interpretation of teachers’ views on these themes are substantiated in the result section.

Field notes

Facilitators wrote field notes after each meeting to summarise and reflect on how they modelled the research tasks. Every modelling practice was evaluated in a structured template in which the facilitators described the specific situation, their actions, the consequences of these actions and their reflections on the usefulness of their modelling. These field notes were discussed with all researchers involved. The first author selected a subset of the notes to exemplify whether and to what extent the facilitators’ reflections were in line with the teachers’ evaluations. The selection was discussed with the second author to ensure representative coverage.

Questionnaire

summarises the practitioner research questionnaire teachers filled-out before and after the professional development programme. The five scales, taken from the validated questionnaire by Krüger (Citation2010), addressed teachers’ views on their research skills, research disposition and use of research in practice. Research skills were measured by two scales that gauged teachers’ ability to conduct research and use research data. Teachers’ research disposition was measured by a third scale and the use of research in school was measured by two additional scales, one containing items about teachers’ personal intentions to conduct research and the other one addressing collaboration with peers. Each item could be rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree to completely agree.

Table 2. Scales and sample items of the practitioner research questionnaire.

Scale means were calculated by taking the average of the constituent item scores. In cases where one item was unanswered, the scale mean was based on the scores of the remaining items. In one instance, two scale items were left blank; this scale was scored as ‘missing’ and the participant was excluded from the analysis. Reliability estimates of the five scales were deemed acceptable. Scale means were analysed by repeated measures MANOVA.

Results

offers an overview of the themes and subthemes that surfaced during the focus group interviews. All teacher teams had a positive general impression of the guidance offered by the facilitators. They felt the facilitator was actively involved in their learning process, was patient and easily accessible. As Fiona (team 3) stated:

You calmly answered all our questions and I really liked that. That you don’t feel like ‘well, this was a very stupid question I just asked about the research’, but like I was actually heard in the question I asked.

Table 3. Themes and subthemes on the facilitators’ guidance.

Regarding the organisation of guidance, the teacher teams felt the facilitators efficiently guided the research process and offered a clear structure to the research study. This positive attitude was also reflected in teachers’ remarks about the materials they received. The description of research tasks helped in deciding which tasks they had to perform, and according to Joshua (team 2) ‘you could almost literally read along with what you had in mind’. The handbook on practitioner research was not actively used in the teacher teams. This might be because of the elaborate guidance already offered during the programme. Indeed, teachers in team 1 and 2 mentioned it as valuable for future use, when a facilitator would not be present. Thus, the teacher teams appreciated the facilitators’ guidance because they were actively involved in the teams’ practitioner research and clearly structured the research process.

Modelling research skills

During the professional development programme, the teams increasingly recognised the facilitators’ expertise and the knowledge and skills they could offer. This became especially apparent in team 2 and team 3 when a few teachers attempted to do some extra work on the instruments at a time outside of the planned meetings. Marjorie (team 3) explained this situation as follows: ‘Harry and I missed you at a crucial moment … . We sat beside each other for half an hour thinking: what should we do, haha! …and then you came and we finished within half an hour’. The teachers felt such situations emphasised the importance of the facilitators’ skills when modelling the research tasks.

Despite the teams’ overall positive views on the facilitators’ input and expertise, teachers from team 1, 2 and 3 preferred to perform part of the research themselves for several reasons. In team 2 and 3 some teachers were eager to perform more of the research tasks because of their interest in specific subtasks, such as certain steps in the search for literature or specific data analyses. A few teachers from team 1 wanted to try to perform research themselves and receive feedback afterwards. This preference might be related to these participants’ experience: they already were somewhat familiar with doing research and might therefore benefit more when starting on a higher level (i.e. the second phase of the teacher guidance model, see ).

A notable fruitful element of the facilitators’ modelling was the use of good-practice examples. The partly-worked out research plan was appreciated by team 1, 3, and 4, as Jenny from team 1 stated ‘it could be used for the next research study’. The usefulness of practice-examples for specific research tasks was reflected in team 4 where examples of measurement instruments were not readily available because of the specific nature of the research topic (the school’s core values). The lack of these examples made it difficult for teachers to develop an instrument themselves, as Miranda said: ‘I found it quite hard to think of good items, positively or negatively stated’. Amber (facilitator) recognised this problem too as she wrote: ‘I should have put more effort in finding possible [exemplary] instruments because I think this time it got a little out of hand. I didn’t establish the creative process I wanted’. In teams 1 and 3—where examples were present—both teachers and facilitators explicitly mentioned them and showed their appreciation, as Patricia (team 3) said: ‘I think it would be a coincidence if I would actually find a good questionnaire. Like, what you gave us … you can work with that and adapt it to the primary school level. Yes, that was quite nice’. This shows that sample materials are valuable in giving teachers concrete ideas on how to perform a research task.

Regarding the timing of the modelling, team 1 and 2 commented on the facilitators’ modelling before a task. They felt it was useful, but in some cases also tedious and difficult to grasp. This criticism could be related to the teacher’s mediocre understanding of some of the research tasks, as Claire (team 1) said ‘Well, sometimes I think … that not until afterwards we understand what you said beforehand, because we do not yet have the model to which it fits’. The facilitators acknowledged this issue in their field notes. They felt that modelling before the task was needed as it provided teachers with the information required to make informed decisions about the research, but that it was also difficult to involve the entire group, as Noortje said: ‘Modelling of expectations went okay, but I also felt that I lost a few teachers along the way’. About modelling data analysis methods she contemplated:

I noticed that, although I made it quite concrete by using the instruments, the teachers were less focused. I think it was helpful [for them], but I think I should not dwell on it for too long the next time.

So, it seems that despite multiple efforts, the facilitators found it challenging to keep the full attention of all teachers when modelling before the task.

Modelling during a task was considered a powerful support strategy by all teacher teams. Carmen (team 2) summarised their ideas as follows: ‘That morning when we started, wow, we thought okay, where will this lead us? Do we understand everything? But at a certain moment it was really fun to work in small groups and explore it yourself’. Mary (team 2) added: ‘That we just did it together. Part of it we can do ourselves, another part you showed how it works, yes this was very informative’. The facilitators were equally positive and felt that ‘modelling on the spot worked very well’ for improving teachers’ research skills.

Teams that commented on modelling after a task (team 1, 2, and 4) felt it was hard to follow the modelling process and difficult to fully understand how a task was conducted. This scepticism might be related to the nature of these tasks. The literature search and data analyses in particular required an extensive amount of time to perform, which made it difficult for facilitators to model every step in full while at the same time keep the teachers’ attention. This was reflected in Noortje’s fieldnotes: ‘I doubt whether just telling what I did was memorable enough… I think I should make it more concrete’. After having tried this suggestion with the next team, some doubt remained: ‘I am quite pleased … However, they will need support when they would carry this out themselves. They probably won’t remember everything I told them’. Similarly, Amber contemplated ‘The main issue is that I cannot just give them my knowledge’. These doubts were reflected in a comment by Florah (team 2) about the literature search: ‘I know you can use literature, I know that you showed us and involved us in how you did this, but I don’t have the feeling I can do it myself the next time’. So modelling after the task appeared insufficient for teachers to confidently perform these research tasks themselves.

Modelling of a research disposition

Teachers’ opinion of the facilitator’s modelling of a research disposition changed over time. This was particularly apparent in team 1 and 3, where teachers experienced the facilitators’ questions as frustrating at the beginning of the programme, as Joanne (team 3) said:

I had the feeling that we needed to explain a lot. Like, is it going like this, or are we doing that?… And then it felt like we had to start again. I felt that really strongly at that time. I thought we were there and then we had to do it all over again.

Later on, several teams (1, 3, 4) began to appreciate the facilitators’ questioning. For example, Marjorie (team 3) explained how it helped her during data analyses:

You helped me quite a lot with this. Like, okay, I need to verify this with someone else first. Is it correct? I tend to really have a tunnel vision and keep doing it my way. And every time you said ‘no, first you need to, and is that correct, and talk about this once more’ … You really taught me to slow down and discuss this with others, that’s a new focus point for me.

And, in reflecting on the change in attitude regarding the facilitators’ questioning, Charlotte (team 1) said: ‘When we look back on the research … when we would do the research question again, or make new criteria, we would do it differently. And you tried to do this already at an earlier moment’.

The third and fourth author, brought in as critical friends at the first three meetings were appreciated in team 1 and 4 because their questions ‘focused their minds’ (Mia, team 4). However, for other teachers in team 1 and 2, the additional researcher was a bit too much: ‘It became a bit chaotic … I don’t know whether it was because you were with two persons, but at a certain point you lost me’ (Ava, team 2). And Sophia (team 1) argued: ‘ … Noortje could do this as well, right? I didn’t need this backup’. This illustrates that although an additional researcher was useful for developing a research disposition, it might have been a bit too much for teachers who are learning to perform research for the first time.

The facilitators were positive about the outcomes of their modelling of a research disposition throughout the research. They felt teachers’ awareness of their research decisions grew and noticed that they thought about them more deeply when their decisions were critically questioned.

Teachers’ research skills, disposition and use

Results of the practitioner research questionnaire showed that teachers generally considered themselves quite capable of doing practitioner research at the start of the professional development programme. This perceived competency had significantly increased after the programme ended, F(5, 32) = 2.72, p = .037, Pillai’s trace = .30, partial η2 = .30. The univariate tests in show that teachers scored significantly higher on all scales after the professional development programme ended, except for the ability to use research data. This nonsignificant result is reflected in some remarks about this skill during the focus group meetings: ‘I don’t know how to do this Excel, first I’ll need to do a course’ (Miranda, team 4) and ‘if I had to it again, I would still need the support’ (Charlotte, team 1).

Table 4. Univariate analyses of the practitioner research questionnaire (n = 37a).

Discussion

This study investigated modelling as a means to support teachers in a professional development programme that revolved around doing practitioner research. Research in other learning contexts suggests that modelling can effectively enhance teachers’ professional development (see Hogg and Yates Citation2013; Loughran and Berry Citation2005). Our study confirms this contention: teachers appreciated the guidance they received during their practitioner research study; it was thoroughly organised and the use of good-practice examples were seen as powerful means to model research tasks. Furthermore, teachers perceived an overall increase in their research skills, research disposition and use of research in school.

Regarding the timing of the modelling activities, modelling during the task seems to best serve teachers who are beginners in practitioner research. The combination of brief moments of modelling and direct application in practice allowed teachers to explore the research tasks themselves and at the same time receive just-in-time feedback to successfully complete the tasks. Facilitators’ modelling before and after the task was considered informative, but also difficult for teachers to fully grasp. This lack of understanding could be related to differences in teachers’ and facilitators’ research experience. As most teachers did not have any experience with conducting research, it might have been difficult for them to fully understand why certain reasoning processes and decisions were relevant and how they could use it to their benefit. For example, the facilitators, with years of research experience, intuitively knew which decisions had to be made in order to prevent problems later on in the research. Their reasoning was built upon this notion. However, as teachers faced a completely new way of investigating their teaching and had not yet experienced such problems, the facilitators’ reasoning might have gone over their heads. Thus, merely offering an overt account of a researchers’ thinking process (cf. Collins, Brown, and Holum Citation1991; Jonassen Citation1999) is not enough: facilitators should also be cognisant of differences in underlying knowledge of performing research between teachers and researchers.

The results further show that demanding or time consuming tasks might be unsuitable to model afterwards. It was deemed more efficient for the facilitator to perform such tasks in between meetings and model their actions and decisions afterwards. However, both facilitators and teachers expressed doubts about whether the teachers would be able to perform the task themselves in future. For difficult tasks it might be more useful if teachers are more involved, for example by first trying the task themselves – which proved valuable in modelling during the task. For laborious tasks this is unfeasible because the time involved is generally not available in the school context. A more fruitful alternative is to simplify the time-consuming research tasks. For example, teachers neither have the time nor the means to peruse comprehensive scientific databases during a literature search, but they could consult more accessible resources. Currently, government websites increasingly offer practice-oriented research materials, such as databases of summaries of research findings from randomised controlled trials in education (e.g. http://www.whatworks.ed.gov and https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk; Edovald and Nevill Citation2021); resources like these might enable teachers to more easily find and use scientific information themselves.

In modelling a research disposition, differences between facilitators and teachers surfaced again. In the classroom context, teachers have to directly act on their ideas as the problems that arise have to be solved immediately, while in the research context of our professional development programme they had to elaborately discuss and criticise each decision made (cf. Farley-Ripple et al. Citation2018; Gravani Citation2008). This change of culture might have caused teachers’ initial frustration. Offering a more thorough explanation behind the questions asked might alleviate such discouraging feelings. Loughran and Berry (Citation2005) give an insightful example of how the reasoning behind what is being modelled can be made more explicit. They modelled their teaching by openly questioning each other’s decisions and expressing their personal doubts and uncertainties. In our study, the critical friends who now questioned teachers’ decisions, might focus more on the ideas of the facilitator when modelling their research disposition. This could result in less frustrations and more insight in a research disposition from early on in the programme.

The overall increase of teachers’ scores on the practitioner research questionnaire suggests that guidance by means of modelling paid off. The only exception was the below average increase in the use of research data. This outcome is perhaps not entirely surprising because the data analysis techniques used in the programme were new to most teachers. These analyses techniques were therefore heavily guided, which increased teachers’ awareness of the numerous new possibilities for data analyses. Learning to analyse data is not feasible in one meeting; research on the use of data in schools shows that learning to use research data requires considerable time and effort (Edith and Mandinach Citation2015; Schildkamp, Poortman, and Handelzalts Citation2015; Wohlstetter, Datnow, and Park Citation2008). Thus, more time and practice is needed to become familiar with specific data analyses techniques to use them in future research activities.

Some caution is in order when interpreting the outcomes of this study. For example, the results of the questionnaire are based on teachers’ self-reports on performance in practitioner research. As self-assessments are prone to subjectivity, we cannot conclude that teachers actually improved their performance. Nonetheless, these findings do provide insight in teachers’ self-efficacy in performing practitioner research, which seems indicative of teachers’ willingness to engage in practitioner research in the future (see Bray-Clark and Bates Citation2003). Regarding the focus group interviews, it should be noted that such data relies heavily on the interpretation of the researcher. We tried to mend this issue by systematically analysing the focus group data and by discussing each step in our analysis. As there were only a few instances in which there were differences between raters and these were easily resolved, we believe that these efforts were successful in presenting an objective account of the data. Another issue related to the focus group interviews is that they are dependent on group dynamics (Morgan Citation1996), in our case the relations between the teachers and the relation they developed with the facilitator over the course of the programme. The expert role of the facilitator might have made the teachers more susceptible to provide socially desirable answers. However, the results do not suggest this was the case. Teachers critically discussed the modelling activities and offered several suggestions for improvement. Finally, as this study did not include a control condition, causal conclusions cannot be made. Future research should investigate whether teachers who conduct practitioner research without being facilitated would show a lower increase on confidence ratings than teachers who are supported through modelling.

The current study was a government funded collaborative effort between two universities and a large primary school. This made it possible to secure several provisions for the professional development programme. When writing the research proposal, foundations were laid for the university-school partnership and funding made it possible for both researchers and teachers to invest considerable time and effort to work on the project; the school leader was part of the project team, encouraged teachers to become part of this professional development initiative, and was actively involved in the research studies; and teachers were already used to work in learning communities and had the possibility to investigate self-chosen topics. Such conditions are important for the successfulness of professional development through practitioner research (De Paor and Murphy Citation2018; McLaughlin and Black-Hawkins Citation2007) and provided a stable foundation for this study. When considering transferability of our results to other contexts, the aforementioned provisions should be taken into account.

To conclude, this study showed how modelling can be successfully applied to guide teachers in learning to conduct practitioner research. Especially modelling during the task is a powerful means to support teachers in performing practitioner research. Modelling before and after the task, and modelling of a research disposition could be improved further. Explicit attention should be paid to differences between the teaching and research community in order to create smooth collaboration between teachers and researchers. The modelling offered in this study might also be useful for other contexts, such as the guidance of pre-service teachers’ practitioner research (Heissenberger-Lehofer and Krammer Citation2021; Moran Citation2007; Ulvik Citation2014), or other professional development programmes that employ experts to guide teachers in their learning process (e.g. Christine, Yow, and Peters Citation2014; Den Bergh, Linda, and Beijaard Citation2014).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences of the University of Twente. Approval number:15460.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Noortje Janssen

Noortje Janssen is an assistant professor at Radboud University. In her PhD project at the University of Twente she investigated how to assist teachers when integrating technology in their lesson plans. Her most recent research project revolved around the development of a four phase model to support in-service teachers in conducting practitioner research.

Amber Walraven

Amber Walraven is a teacher educator and researcher at the Radboud Teacher Academy at Radboud University. She is an expert in the field of ICT in education. Integrating ICT in education, and what that means for teachers, students and organisation are the main focus of her research.

Ard W. Lazonder

Ard Lazonder is a professor of education at the Behavioural Science Institute at Radboud University. He specialises in early science instruction, and has an increasing interest in the research skills of the teacher. His current research involves the development of scientific reasoning in children, and explores ways for teachers to adapt instruction to suit the needs of individual learners.

Hannie Gijlers

Hannie Gijlers is an assistant professor at the Department of Instructional Technology at the University of Twente. She received her PhD in Educational Sciences from the University of Twente. Her current research focuses on (collaborative) inquiry learning processes in the context of STEM education. Hannie contributed to the design of several ICT based learning environments and published several articles on collaborative inquiry learning in International peer reviewed journals.

References

- Berry, A. 2007. Tensions in Teaching About Teaching: Understanding Practice as a Teacher Educator. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Bertrand, J. T., J. E. Brown, and V. M. Ward. 1992. “Techniques for Analyzing Focus Group Data.” Evaluation Review 16 (2): 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x9201600206.

- Borko, H. 2004. “Professional Development and Teacher Learning.” Educational Researcher 33 (8): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033008003.

- Bray-Clark, N., and R. Bates. 2003. “Self-Efficacy Beliefs and Teacher Effectiveness: Implications for Professional Development.” Professional Educator 26 (1): 13–22.

- Christine, L., J. A. Yow, and T. T. Peters. 2014. “Building a Community of Practice Around Inquiry Instruction Through a Professional Development Program.” International Journal of Science & Mathematics Education 12 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-012-9391-7.

- Cochran-Smith, M., J. Barnatt, A. Friedman, and G. Pine. 2009. “Inquiry on Inquiry: Practitioner Research and Student Learning.” Action in Teacher Education 31 (2): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2009.10463515.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. Landy Lytle. 1993. Inside/Outside: Teacher Research and Knowledge. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Collins, A., J. S. Brown, and A. Holum. 1991. “Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible.” American Educator 15 (3): 6–11.

- Den Bergh, V., A. R. Linda, and D. Beijaard. 2014. “Improving Teacher Feedback During Active Learning.” American Educational Research Journal 51 (4): 772–809. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322.

- De Paor, C., and T. R. N. Murphy. 2018. “Teachers’ Views on Research as a Model of CPD: Implications for Policy.” European Journal of Teacher Education 41 (2): 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416086.

- Desimone, L. M. 2009. “Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures.” Educational Researcher 38 (3): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x08331140.

- Edith, G., and E. B. Mandinach. 2015. “Building a Conceptual Framework for Data Literacy.” Teachers College Record 117 (4): 1–22.

- Edovald, T., and C. Nevill. 2021. “Working Out What Works: The Case of the Education Endowment Foundation in England.” ECNU Review of Education 4 (1): 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120913039.

- Farley-Ripple, E., H. May, A. Karpyn, K. Tilley, and K. McDonough. 2018. “Rethinking Connections Between Research and Practice in Education: A Conceptual Framework.” Educational Researcher 47 (4): 235–245. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x18761042.

- Garet, M. S., A. C. Porter, L. Desimone, B. F. Birman, and K. Suk Yoon. 2001. “What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results from a National Sample of Teachers.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (4): 915–945. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038004915.

- Glazer, E. M., and M. J. Hannafin. 2006. “The Collaborative Apprenticeship Model: Situated Professional Development within School Settings.” Teaching & Teacher Education 22 (2): 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.004.

- Gravani, M. N. 2008. “Academics and Practitioners: Partners in Generating Knowledge or Citizens of Two Different Worlds?” Teaching & Teacher Education 24 (3): 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.008.

- Heissenberger-Lehofer, K., and G. Krammer. 2021. “Internship Integrated Practitioner Research Projects Foster Student Teachers’ Professional Learning and Research Orientation: A Mixed-Methods Study in Initial Teacher Education.” European Journal of Teacher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1931112.

- Hilda, B., D. Liston, and J. A. Whitcomb. 2007. “Genres of Empirical Research in Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 58 (1): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106296220.

- Hogg, L., and A. Yates. 2013. “Walking the Talk in Initial Teacher Education: Making Teacher Educator Modeling Effective.” Studying Teacher Education 9 (3): 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2013.831757.

- Hondrich, A. L., S. Hertel, K. Adl-Amini, and E. Klieme. 2016. “Implementing Curriculum-Embedded Formative Assessment in Primary School Science Classrooms.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 23 (3): 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1049113.

- Hubers, M. D., M. Endedijk, and K. Van Veen. 2020. “Effective Characteristics of Professional Development Programs for Science and Technology Education.” Professional Development in Education 48 (5): 827–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1752289.

- Jonassen, D. H. 1999. “Designing Constructivist Learning Environments.” In Instructional Design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory, edited by C. M. Reigeluth, 215–239. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Kennedy, A. 2005. “Models of Continuing Professional Development: A Framework for Analysis.” Journal of In-Service Education 31 (2): 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580500200277.

- Koutselini, M. 2008. “Participatory Teacher Development at Schools: Processes and Issues.” Action Research 6 (1): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307083718.

- Krüger, M. L. 2010. De Invloed van Schoolleiderschap op het Onderzoekend Handelen van Leraren in Veranderingsprocessen: Eindrapport Kenniskring Leren en Inoveren. [The Influence of School leaders on the Research Disposition of Teachers in Change Processes: Final Report Knowledge center Learning and Innovations]. https://www.hva.nl/binaries/content/assets/subsites/kc-oo/publicaties/de-invloed-van-schoolleiderschap-op-het-handelen-van-leraren-in-veranderingsprocessen—meta-kruger—kcreeks-nr.-06-.pdf.

- Kurniawati, F., A. A. De Boer, A. E. M. G. Minnaert, and F. Mangunsong. 2017. “Evaluating the Effect of a Teacher Training Programme on the Primary Teachers’ Attitudes, Knowledge and Teaching Strategies Regarding Special Educational Needs.” Educational Psychology 37 (3): 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1176125.

- Loughran, J., and A. Berry. 2005. “Modelling by Teacher Educators.” Teaching & Teacher Education 21 (2): 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.005.

- Loughran, J., K. Stephen, and C. Rebecca. 2016. “Pedagogical Reasoning in Teacher Education.” In International Handbook of Teacher Education, edited by J. Loughran and M. L. Hamilton, 387–421. Singapore: Springer.

- Lunenberg, M., F. Korthagen, and A. Swennen. 2007. “The Teacher Educator as a Role Model.” Teaching & Teacher Education 23 (5): 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.001.

- Marsh, J. A., and C. C. Farrell. 2015. “How Leaders Can Support Teachers with Data-Driven Decision Making: A Framework for Understanding Capacity Builing.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 43 (2): 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214537229.

- McLaughlin, C., and K. Black-Hawkins. 2007. “School–University Partnerships for Educational Research—Distinctions, Dilemmas and Challenges.” The Curriculum Journal 18 (3): 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170701589967.

- Merchie, E., M. Tuytens, G. Devos, and R. Vanderlinde. 2018. “Evaluating Teachers’ Professional Development Initiatives: Towards an Extended Evaluative Framework.” Research Papers in Education 33 (2): 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271003.

- Montenegro, H. 2020. “Teacher Educators’ Conceptions of Modeling: A Phenomenographic Study.” Teaching & Teacher Education 94:103097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103097.

- Moran, M. J. 2007. “Collaborative Action Research and Project Work: Promising Practices for Developing Collaborative Inquiry Among Early Childhood Preservice Teachers.” Teaching & Teacher Education 23 (4): 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.008.

- Morgan, D. L. 1996. “Focus Groups.” Annual Review of Sociology 22 (1): 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129.

- Pea, R. D. 2004. “The Social and Technological Dimensions of Scaffolding and Related Theoretical Concepts for Learning, Education, and Human Activity.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 13 (3): 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_6.

- Poekert, P. 2011. “The Pedagogy of Facilitation: Teacher Inquiry as Professional Development in a Florida Elementary School.” Professional Development in Education 37 (1): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415251003737309.

- Ponte, P. 2002. “How Teachers Become Action Researchers and How Teacher Educators Become Their Facilitators.” Educational Action Research 10 (3): 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790200200193.

- Schenke, W., H. V. D. Jan, P. G. Femke, and L. V. Monique. 2017. “Boundary Crossing in R&D Projects in Schools: Learning Through Cross-Professional Collaboration.” Teachers College Record 119 (4): 1–42.

- Schenke, W., J. H. Van Driel, F. P. Geijsel, H. W. Sligte, and M. L. Volman. 2016. “Characterizing Cross-Professional Collaboration in Research and Development Projects in Secondary Education.” Teachers & Teaching 22 (5): 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1158465.

- Schildkamp, K., C. Poortman, and A. Handelzalts. 2015. “Data Teams for School Improvement.” Teaching & Teacher Education 27 (2): 228–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1056192.

- Smith, C., and M. Gillespie. 2007. “Research on Professional Development and Teacher Change: Implications for Adult Basic Education.” Review of Adult Learning and Literacy 7 (7): 205–244.

- Sternberg, R. J., and J. A. Horvath. 1995. “A Prototype View of Expert Teaching.” Educational Researcher 24 (6): 9–17. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x024006009.

- Stokking, K. 2015. Bouwstenen voor Onderzoek in Onderwijs en Opleiding. [Building Blocks for Research and Education]. Apeldoorn, the Netherlands: Maklu.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7:221–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Timperley, H. S., J. M. Parr, and C. Bertanees. 2009. “Promoting Professional Inquiry for Improved Outcomes for Students in New Zealand.” Professional Development in Education 35 (2): 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580802550094.

- Ulvik, M. 2014. “Student-Teachers Doing Action Research in Their Practicum: Why and How?” Educational Action Research 22 (4): 518–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2014.918901.

- Van der Rijst, R. 2008. “The Research-Teaching Nexus in the Sciences.” PhD diss., Leiden University.

- van Driel, H. Jan, J. A Meirink, K. van Veen, and R. C. Zwart. 2012. “Current Trends and Missing Links in Studies on Teacher Professional Development in Science Education: A Review of Design Features and Quality of Research.” Studies in Science Education 48:129–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2012.738020.

- van Merrienboer, J. G. Jeroen, A. K. Paul, and L. Kester. 2003. “Taking the Load off a Learner’s Mind: Instructional Design for Complex Learning.” Educational Psychologist 38 (1): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_2.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wohlstetter, P., A. Datnow, and V. Park. 2008. “Creating a System for Data-Driven Decision-Making: Applying the Principal-Agent Framework.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 19 (3): 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450802246376.

- Wood, D., J. S. Bruner, and R. Gail. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

- Zwart, R. C., B. Smit, and W. F. Admiraal. 2015. “Docentonderzoek Nader Bekeken: Een Reviewstudie naar de Aard en Betekenis van Onderzoek door Docenten.” Pedagogische Studien 92 (2): 131–148. [A Closer Look at Teacher Research: A Review on the Nature and Meaning of Research by Teachers].