ABSTRACT

Student diversity in the classroom represents a significant professional challenge for pre-service teachers. The goal of this study is to explore how mentor teachers support pre-service teachers in addressing student diversity during their practicum. Eight pre-service teachers and their six mentor teachers were participants in a multi-sited ethnographic study conducted in the Czech Republic. Data collection took place at lower secondary schools and in a teacher education faculty. We identified seven strategies that mentor teachers use and we explain how these strategies shape pre-service teachers’ thinking and behaviour related to student diversity. The overall outcome presents a contradiction: when mentor teachers model practice, they tend to emphasise individuality; however, when they provide feedback, they tend to emphasise universality. Importantly, we proved that feedback shaped pre-service teachers more than modelling. From the discussion of our findings, we derive six indicators that determine quality mentoring regarding addressing student diversity.

Introduction

Differences among students spring from a wide range of specifics, be they social, cultural or health-related, as well as other diverse individual educational needs based on academic strengths, pace, learning profiles, etc. This complex student diversity represents a significant professional challenge especially for pre-service teachers (PSTs) (e.g. Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016), who, on their practicum, are confronted and often overwhelmed at the beginning of their professional career by a number of pressing issues (e.g. Moore Citation2003). Thus, PSTs need considerable guidance in order to effectively address diversity in the classroom (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2019), which they can learn especially during their practicum. Field-based experience is crucial in shaping PSTs’ attitudes to student diversity (Pérez-Castejón and Vigo-Arrazola Citation2021), increasing motivation and developing practices to address student diversity (Whitaker and Valtierra Citation2018). According to PSTs, mentor teachers (MTs), and especially their style of mentoring (Hennissen et al. Citation2008), play a key role in how they learn to teach through the practicum (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielson Citation2014). Therefore, in this study we interlink two important concepts of mentoring and student diversity because research on mentoring with regard to student diversity is rather scarce (cf. Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020; Hoffman et al. Citation2015). The goal of this study is to explore how MTs support PSTs in addressing student diversity during their practicum. The research took place in lower secondary classrooms located in one large city in the Czech Republic with a sample of eight PSTs and six MTs.

Student diversity

Although the specialist discourse (e.g. Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2019) puts an emphasis on meeting the individual needs of all students, authors typically accentuate addressing the needs of only some groups of students, specifically students with a socio-cultural disadvantage and/or students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). For example, based on an analysis of 152 articles, chapters, reports and books, Grant and Gibson (Citation2011) found out that diversity in the context of teacher education is defined predominantly in terms of race, ethnicity and/or culture, despite frequent mentions in these publications of the importance of addressing the needs of ‘all students’. Similarly, based on a landscape review of more than 1500 empirical studies, Cochran-Smith et al. (Citation2016) present research on teacher preparation for diversity and equity as one of the three dominant research trends in this field. In the reviewed studies, diversity is mainly defined in terms of colour, urban background, language, disability, and gender. More recently, Rowan et al. (Citation2021) have also pointed out that previous review studies concerned with teacher education and student diversity as well as studies included in their own review study stressed the needs of students with SEND and socio-cultural disadvantages. In addition to approaches emphasising the socio-cultural perspective of student diversity, such as social justice and equity (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016) and approaches focused on the education of students with SEND, such as some concepts of inclusive education (cf. Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006), there are also pedagogical perspectives such as differentiated instruction (DI) (Tomlinson Citation2017) emphasising the diversity which manifests in the learning process itself, that is, through different interests, motivations, learning profiles, and academic strengths, etc. It is precisely the pedagogical perspectives regarding student diversity that can be promising in terms of addressing the needs of all students, because they assume that each student has learning strengths and needs and may encounter barriers to learning and participation (Woodcock et al. Citation2022). By presupposing that variability exists in any group of students (Griful-Freixenet et al. Citation2020), the pedagogical perspectives foster the idea that each student’s learning needs are responded to effectively.

Differentiated instruction

Following the need to address the needs of all students led us to define student diversity in our research using the concept of DI (Tomlinson Citation2022), because it represents a broader and more nuanced framework for understanding diversity by going beyond selective conceptualisations arising from narrow socio-cultural categories or simple designations of SEND (cf. Ruys et al. Citation2013). Moreover, the perspective of diversity in the presented research is determined by contextual factors. The research took place in the post-socialistic context of the Czech Republic, from which the socio-cultural homogeneity characteristic of the communist past is slowly disappearing (Jarkovská et al. Citation2015). Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, an acknowledgement of the heterogeneity of students in these countries has been steadily increasing, although socio-cultural diversity is not nearly as pronounced as in many so-called Western societies. Furthermore, the focus on inclusion in education is becoming an important part of the discourse of educational policy and practice in the Czech context, which has seen an increase in the number of students with SEND in mainstream classes. Nevertheless, the average Czech classroom contains approximately 10% of students with SEND, students with socio-cultural disadvantages and foreign students (Czech Statistical Office Citation2019). Therefore, the places where PSTs conducted their practicum within our research were heterogeneous classrooms characteristic of student diversity manifested through different students’ individual learning needs, which are based not just on disabilities or socio-cultural disadvantages, but on other individual characteristics such as motivation, interests, etc.

These reasons lead us to use the concept of DI, as it is an approach to teaching in which the teacher proactively modifies the content, process and product of their teaching to address the diverse needs of students in order to maximise the learning opportunities for each student (Tomlinson Citation2017). The basic components of DI include teachers’ positive attitudes, an environment that supports learning, the diagnosis of student progress through diversified and ongoing assessment, adapting teaching to the level of individual students and usage of flexible grouping. In order to be able to respond to student diversity, the teachers are attentive to homogeneous or heterogeneous grouping according to given criteria, or they adapt their teaching to the level of individual students, which is known as individualisation (Smale-Jacobse et al. Citation2019). Through these organisational forms, the teacher differentiates their teaching based on different student characteristics.

Mentoring with regard to student diversity

Literature reviews (e.g. Clarke, Triggs, and Nielson Citation2014; Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020; Hennissen et al. Citation2008; Hobson et al. Citation2009; Hoffman et al. Citation2015; Nesje and Lejonberg Citation2022; Orland-Barak and Wang Citation2021; Wang and Odell Citation2002) summarise a very wide range of knowledge about mentoring in the context of teacher education. A number of mentoring approaches, strategies and tactics have been found to be effective across different contexts (Hobson et al. Citation2009). Importantly, with regard to addressing student diversity when mentoring, literature reviews have shown that some approaches, such as the critical constructivist perspective (Wang and Odell Citation2002) or the critical transformative approach (Orland-Barak and Wang Citation2021), reflect student diversity in the educational process. These approaches stress the importance of helping PSTs to learn to teach in ways that promote social justice. However, although position papers and general conceptual studies on teacher mentoring approaches as well as various mentoring programmes propose the critical approach as one of the important approaches to mentoring, empirical studies on how mentoring encourages PSTs to address diversity are rarely present in review studies and knowledge is not systematically connected. For example, out of 70 studies analysed in the review study by Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen (Citation2020) identifying what a quality MT is expected to know and be able to do, only one study mentions guidance of PSTs by MTs in taking the needs of diverse learners into account. In their review of 30 studies, Nesje and Lejonberg (Citation2022) analysed the knowledge of tools used in mentoring PSTs during the practicum, and the use of only one tool, namely working with critical incidents, explicitly helped PSTs to learn about individual learners’ differences. A search beyond review studies led us to a few studies that directly dealt with mentoring oriented at taking the different needs of students into account, typically in a socio-cultural tradition (e.g. Achinstein and Athanases Citation2005; Naidoo and Wagner Citation2020). The empirical evidence on mentoring within the perspective of DI is scarce and not systematically linked (Hudson Citation2013; Joseph and John Citation2014).

Methodology

This study was guided by two research questions: 1) What strategies do MTs use to support PSTs in addressing student diversity? 2) What is the relationship between MTs’ strategies in supporting PSTs in addressing student diversity and the behaviour and thinking of PSTs? We applied an ethnographic methodological design, which allows us to capture in detail the thinking and actions of actors both in the longer term and in everyday contexts, emphasising the triangulation of different data sources (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007).

The research took place mainly in lower secondary schools where MTs helped PSTs to learn to teach within their practicum, but also partly at the university where the PSTs were enrolled. At the university, the PSTs look at their interaction with a MT on their practicum retrospectively within a single course, pseudonymised as ‘reflective course’, which aims to enable PSTs to share and reflect on their experience from the practicum.

As the object of our study was a phenomenon spread over multiple environments, we were inspired by Marcus’ (Citation1995) multi-sited ethnography, the main principle of which is to follow people, associations, and relationships between sites. Different environments are chosen in order to provide different information about the phenomenon under study (Falzon Citation2009). As such, we follow the ‘ethnography through thick and thin’ principle (Marcus and Fischer Citation1999), which implies that while places that are more important in terms of research focus must be dealt with ‘thickly’ – in our case lower secondary schools, where the MTs work, in others ‘thinly’ is enough – in our case the university, where there is only one subject with a direct link to PSTs’ practicum and their cooperation with MTs. The basic imperative of multi-sited ethnography, to ‘follow people’, also allowed us to respond flexibly to anti-COVID-19 measures, due to which about a third of the data from the PSTs’ practicum at school were collected online. The partial shift of the research carried out from the physical to the virtual research field was thus an opportunity to observe how the participants addressed the researched phenomenon in another environment (Bagga-Gupta, Dahlberg, and Gynne Citation2019).

Contexts: closer look at lower secondary schools and university environments

Although student diversity in Czech education is growing and educational policies are promoting it (see section ‘Differentiated Instruction’), the institutions where the research took place do not noticeably address the topic of student diversity. There is no unified approach to addressing student diversity, such as DI, in either of the institutional settings, and usually neither MTs nor teacher educators are trained in such an approach. Consequently, PSTs do not have any courses in their university preparation in which they learn about DI and the MTs’ approach does not rely on DI. Nevertheless, we based our research on the DI concept, which we work with as a ‘sensitising concept’ (Bowen Citation2006), allowing us to get a grasp of student diversity in the researched environments analytically (see section ‘Data Analysis’).

The most common way to obtain a teaching degree for lower secondary schools in the Czech Republic is through the structured consecutive model at a public university, consisting of a three-year Bachelor’s study programme and a two-year follow-up Master’s study programme. The studies are a combination of specific preparation for teaching a given subject together with the study of general pedagogy and psychology (for more details see Novotná Citation2019). This path was also the case of PSTs involved in this research. An important role in the follow-up Master’s studies is played by the practicum, which PSTs carry out over three semesters. Each semester they have to complete 120 hours, of which they teach for approximately 40 lessons.

The direct connection of the university with schools takes place mainly through the abovementioned practicum and the reflective course. While the connection between the university and the school where the PST attends the practicum is typically provided by an interaction of the MT, the PST and the university supervisor (Cohen, Hoz, and Kaplan Citation2013), in our context the role of university supervisors is de facto not established and the interaction in this triad takes place only exceptionally. Although the MTs involved in this research were respected by school leaders as well as colleagues for their mentoring and teaching skills, they did not undergo any mentor training. Relatedly, mentoring provided for teachers in their different career phases is not regulated in the Czech context.

Participants and data collection

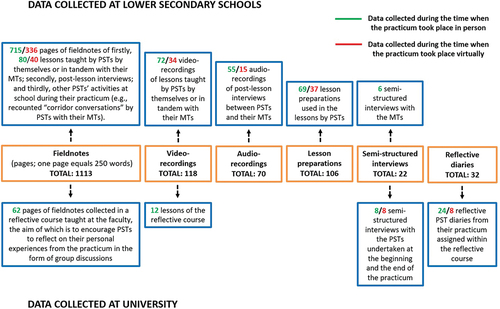

Our sample consisted of eight PSTs during their practicum along with their six MTs (). All these participants are white and of majority ethnic background. Data collection took place in three selected lower secondary schools and in nine different classes attended by students who all have different individual educational needs from the perspective of DI. Additional data were collected in the reflective course at the faculty. All participants, namely PSTs, their peers from the university course, teachers of the course, MTs, and the parents of students from lower secondary classes, signed consent forms which were approved by the Research Ethics Committee. The names of the participants, as well as of the institutions, have been anonymised using pseudonyms. We fully respected the procedural ethical obligations such as the protection of participants’ personal data, but we also performed ‘ethics in practice’ (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004), requiring reflexivity in the day to day conduct of the research.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics – pre-service teachers and their mentors.

All ethnographic observations of the practicum of PSTs, conducted in the subjects of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Civics as well as in post-lesson interviews and in other PSTs’ activities at school e.g. informal interviews with MTs, were captured via fieldnotes which consisted of detailed descriptive accounts of the interactions and incidents regarding diversity, as well as the atmosphere, and characterisations of the actors and settings (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). In addition to fieldnotes, we also collected other data sources. A complete overview of the extensive data corpus is given in .

In all, data were collected for a period of 10 months during the two academic years 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 over the three semesters when PSTs had their practicum. The frequency of our stays in schools was in line with the ‘selective intermittent mode’ of dealing with time in ethnographic research (cf. Jeffrey and Troman Citation2004). This means that data collection had varying intensity with a flexible approach to individual school visits, which depended on the individual situation of the PST.

Data analysis

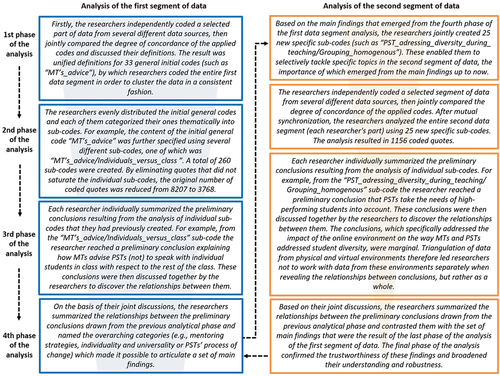

Analytical procedures were applied in correspondence with ethnographic design (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007) and thus data sources were analysed via 1) close reading, i.e. detailed and repeated readings of data; 2) coding, i.e. systematic labelling snippets of data; 3) and theoretical memos, i.e. notes reviewing and developing researchers’ analytical ideas. More specifically, the analysis proceeded in two complete parts, where in the first part the first segment of the collected data was analysed in four phases and in the second part the second segment of the collected data was analysed in four phases (see ). This procedure is in line with ethnographical assumptions that: 1) data analysis is not a distinct stage of the research process; 2) subsequent data collection is guided strategically by emergent explanations developed out of data analysis; and 3) analysis needs to become gradually more focused. While the first segment of data consisted of less than half of all data, exclusively from physical research sites, the second segment consisted of the remainder of the data corpus and included data from both physical and virtual research sites.

Figure 2. Phases of data analysis.

To ensure the validity of the findings, we respected several analytical strategies typical in ethnographic research. By respecting the idea that coding is a recurrent process, researchers repeatedly read and coded data in several analytical phases, ensuring the groundedness of the findings. Further, a related analytical strategy we used was triangulation, which meant developing analysis and interpretation by contrasting different data sources (see ) from various environments i.e. lower secondary schools and university environments as well as physical and virtual environments. This was facilitated by the Atlas.ti programme, where different data sources were coded simultaneously and thus constantly contrasted to enhance the validity and robustness of the findings, with the exception of video-recordings, which were analysed selectively if other coded data sources were not sufficiently detailed. Finally, the findings are based on a cross-case analysis of all participants and are grounded in richly saturated codes and categories.

We worked analytically with DI as with a ‘sensitising concept’ (Bowen Citation2006) that helped us understand how MTs help PSTs address student diversity. However, at the same time, when working with data, we followed the inductive character of ethnographic design. We balanced between two analytical positions, where important categories of DI served as background ideas which informed our inductively driven data collection and subsequent analysis.

Findings

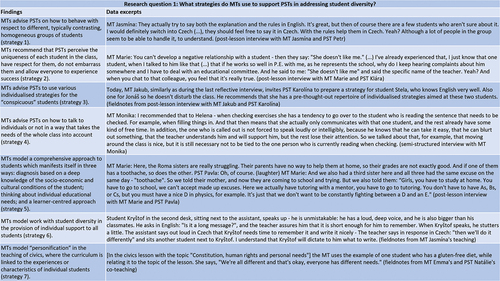

In the first Findings section, we introduce the strategies that MTs use to support PSTs in working with student diversity, thereby addressing the first research question. In the second Findings section, we explain the relationship between MTs’ strategies and the behaviour and thinking of PSTs, thereby addressing the second research question. Illustrative data excerpts are listed directly in the text, but also in Appendix A and Appendix B.

Mentor teachers’ strategies supporting pre-service teachers in addressing student diversity

In our data, with regard to mentoring on the issue of student diversity, two of the principal ways in which MTs participate in teacher education (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielson Citation2014) were evident: providing feedback and modelling practice.

Within these two dominant ways of mentoring which were used with regard to student diversity we identified seven mentoring strategies. These strategies reflect the way MTs think and act when they:

advise PSTs on how to think about student diversity, how to work with it, and in this context also evaluate the PSTs’ treatment of student diversity during their teaching (strategies 1-4);and

demonstrate for the PSTs how they think about student diversity and how they address student diversity in teaching (strategies 5-7).

The strategies were applied in the context of three different types of organisational forms of teaching: one-to-one instruction (strategies 3–6), group instruction (strategy 1) and within whole-class instruction (strategies 2 and 7).

Providing feedback with regard to student diversity

First, we present the strategy corresponding to the organisational form, referred to above as group instruction, specifically homogeneous grouping. We call this strategy ‘invisible’ homogeneous grouping because MTs advised PSTs to divide students into groups only mentally. The imaginary division into groups is not obvious to the students in the classroom, because the PST does not verbalise it. Students then experience only the effects of this mental activity of the PST. MTs advise PSTs on how to behave with respect to different, typically contrasting, homogeneous groups of students (strategy 1):

students who either participate in class or not – MTs advise PSTs, for example not to call on all those who want to say something;

students following instructions or not – MTs recommend, for example, strategies for preventing discipline problems;

struggling/advanced students – MTs recommend, for example, helping struggling students; and

fast/slow students – MTs recommend, for example, continuing with another activity if most of the class has completed the previous task.

We illustrate this type of recommendation with an excerpt in which MT Jakub encourages PST Karolína to support the students who put up their hands, but at the same time to encourage those who only put up their hands now and then or not at all to be more active e.g. those students who are passive or lack confidence.

MT Jakub: There are children who keep putting their hands up and it bothers us as teachers to leave the children with their hands up and not to call on them (…), but those passive students who don’t have confidence have to talk in that lesson.

PST Karolína: Mhm.

MT Jakub: (…) So in fact, eh, you should never get into a situation where you are just grateful to someone who says something. (Post-lesson interview with MT Jakub and PST Karolína)

As for the approach to classroom students, MTs recommend that PSTs perceive the uniqueness of each student in the class, have respect for them, do not embarrass them and allow everyone to experience success (strategy 2). In the words of MT Jakub, it is essential that ‘every single individual student feels that the teacher is interested in them, that they are simply not just formless grey matter’ (semi-structured interview with MT Jakub). We refer to these principles emphasised by MTs as a learner-centred approach because they stress the accepting relationship between teacher and student, although only in general terms.

In addition to the learner-centred approach, MTs advise PSTs on various individualised strategies, including strategies for responding to or preventing discipline problems e.g. using signals instead of shouting (strategy 3). Often, these are recommendations regarding students with SEND, but also students without formalised support measures who are conspicuous in terms of their degree of disruption, talent or speed in performing assigned tasks, etc. We refer to these students analytically as ‘conspicuous’ students. For example, MT Monika advised PST Helena to regularly check on ‘conspicuous’ student Václav, who has attention deficit disorder, to see if he was working on the assigned task (post-lesson interview with MT Monika and PST Helena).

Individualised recommendations were also related to the relationship between the individual and the class (strategy 4). Surprisingly, these recommendations typically do not take the educational needs of individual students into account, but rather prioritise the needs of the class as a whole. Although at first glance it may seem that such recommendations imply individualisation, as they are aimed at specific students, in reality the individual in this sense is more a tool to make teaching the class as a whole more effective. For various reasons, MTs advise PSTs on how to talk to individuals or not in a way that takes the needs of the whole class into account. For example, MT Jasmína recommended that PST Petr moderate student with SEND Kryštof’s speaking, so that the rest of the class could also speak. The MT even stated that she turned off Kryštof’s microphone towards the end of the online lesson (post-lesson interview with MT Jasmína and PST Petr).

Modelling practice with regard to student diversity

Modelling is ‘intentionally displaying certain teaching behaviour with the aim of promoting student teachers’ professional learning’ (Lunenberg, Korthagen, and Swennen Citation2007, 589); however, it does not have to be just about behaviour: modelling of thinking is also important (Glazer and Hannafin Citation2006). Both forms of modelling appeared as important ways of mentoring with regard to student diversity in our data.

The results of the analysis show that MTs model a comprehensive approach in relation to ‘conspicuous’ students, but unlike when providing feedback, they also perform it in relation to other students (strategy 5). This comprehensive approach manifests itself in three ways: diagnosis based on a deep knowledge of the socio-economic and cultural conditions of the student; thinking about individual educational needs; and a learner-centred approach. The following quote illustrates all these aspects in interrelationship:

MT Emma: I had a meeting with Mr. Smith, that’s his [Sergei’s] dad with a special pedagogue and three teachers, on the topic that he was changing the family environment; he switched from living with his mother to living with his father. The father suddenly requires discipline and so on (…) And one of those things [dad wants him to do] is to behave himself, which means to be polite, helpful, stop clowning around and he is working on it. (Post-lesson interview with MT Emma and PST Daniel)

The MT models detailed knowledge of the family background of Sergei, who has an African-American father and a mother of Ukrainian origin, and is thus being brought up tri-lingually. This is reflected in his weaker achievement in Czech and English. Emma shows her that she is working closely with Sergei’s father, and they agreed that they would work together on helping Sergei to behave politely.

MTs also inscribed the comprehensive approach to working with diversity in their behaviour either, for example, within their own teaching, which PSTs usually observe at the beginning of the practicum, or during their co-teaching with PSTs. MTs model work with student diversity in the provision of individual support, as opposed to feedback, to all students (strategy 6), although the way MTs differentiated for students’ needs was typically rather reactive. This means that student support was limited as it was not usually based on an explicit system of planned differentiation strategies. The following excerpt illustrates modelling of providing positive feedback to student Nina in the English lesson, the aim of which was to present individual students’ projects focused on the definition of selected objects from space.

MT Emma: Nina, very nice (…) so thank you very much (she claps), this is probably the first time that Nina has produced such a beautiful thing and especially how long you have been speaking, Nina, I think you can be very proud of yourself. Don’t you think?

Nina: I don’t know (shyly, pleased).

MT Emma: What? You’ve never spoken for such a long time in one go. Really.

(Video recording of MT Emma’s teaching)

The quote suggests that the MT provides individualised and encouraging feedback on the presented project to a rather shy student. This is an example of a MT’s reactive individualisation to a student’s speech in a lesson, which, however, had not been planned in advance.

In the last strategy (7) we identified MTs modelling individualisation within whole-class instruction. In the following excerpt, MT Marie illustrates the significance of the subject of the lesson, which is the influence of the environment on a person’s personality, with respect to student Suri from India.

Then [Marie] asks Suri and firstly she clarifies for me and Klára in the back that Suri came from an Indian school, her father is Indian, and her mother is Czech. At Marie’s request Suri talks about what the difference was, for example, that they were ‘very generous, but there were 50 of them in the class’. (…) Marie emphasises that ‘there is order and discipline there’, as Suri said. (Fieldnotes from MT Maria’s teaching)

In this strategy Marie ‘personifies’ the curriculum of civics with the characteristics and life experiences of student Suri. Even curricular topics that do not explicitly address human diversity are taught through students’ specific interests and experiences, because MTs make use of the knowledge of students’ characteristics and family backgrounds.

The relationship between mentors’ strategies and the behaviour and thinking of pre-service teachers

It turns out that PSTs are mainly shaped by feedback of MTs, rather than their modelling. This statement is based on the dominant patterns in the data about the behaviour and thinking of PSTs related to student diversity, which are visibly linked to the strategies applied by MTs when giving feedback.

PSTs differentiate unevenly in their teaching – they reflect on and take into account almost exclusively the individual educational needs of the ‘conspicuous’ students, who, however, form only a minority of the class. For example, PST Adam helped student Pepa to engage in the group, which is difficult for the student due to his signs of autism.

The students are divided into groups, and Pepa remains alone. PST Adam invites him to join a group. When he hesitates, he assigns him to one of the groups. (…) Pepa gets up and joins his classmates. During the activity, he is not very involved in group work. Adam goes over to the given group several times during the activity and tries to help Pepa to participate more in the activity. (Fieldnotes from PST Adam’s teaching)

The focus on ‘conspicuous’ students was manifested not only in their actions, but also in the PSTs’ thinking. This can be seen, for example, in the reflective diary of PST Pavla, who reflected on how to enable student Zora with ADHD to experience success and thus prevent her indiscipline (PST Pavla’s third reflective diary). This implies that PSTs are shaped by mentoring strategy 3, in which MTs advise PSTs on various individualised strategies, typically involving ‘conspicuous’ students.

PSTs address differentiation for the majority of the students in the class significantly less. If they already differentiated in their teaching, it concerned especially high-performing students, who are advanced, faster or more active, as illustrated by the following quotation from the teaching of Petr: ‘Petr checks the students’ work, and if someone has finished, he assigns them exercise 3’ (fieldnotes from PST Petr’s teaching). This way of differentiation implies that PSTs are shaped by mentoring strategy 1, within which MTs advise PSTs on how to behave with respect to different, typically contrasting, homogeneous groups of students. PSTs often applied a similar type of strategy in situations where their attention had to be given to one student and to the rest of the class at the same time, implying that PSTs are shaped by mentoring strategy 4, in which MTs advise PSTs on how to talk to individuals or not in a way that takes the needs of the whole class into account.

PST Daniel asks how to say the word earthquake in English. Leoš knows and answers again. Daniel asks him to write it in the chat. Daniel comments that today Leoš is ‘a bit overexcited’ and knows everything, but that he has to give space to the others as well. Moments later, the situation repeats itself. Leoš wants to read again, but Daniel says that it will be good if someone else reads (Fieldnotes from PST Daniel’s online teaching)

Although PSTs tried to balance this conflict of attention to a greater or lesser extent during their practicum, for example through the strategy in which the PST invites the class to help the individual, in these situations the individual served as a teacher’s tool to make teaching the whole class more effective, rather than to primarily take their individual needs into account.

As implied by the compelling relation between the PSTs’ behaviour and thinking and the MT feedback strategies, PSTs typically accept their MTs’ advice and put it into practice in their dealings with students in the classroom, even though they do not always agree with it. In some cases, the acceptance of advice led to a dampening of PSTs’ efforts to take the diverse needs of students into account. A potential disagreement is usually reflected on by the PSTs themselves, for example in their reflective diaries, not in direct interaction with the MT, as illustrated in the following excerpt from the semi-structured interview with PST Karolína.

Researcher: Do you think it has something to do with what MT Jakub recommended that when two-thirds of [students] have finished, you should move on and not wait?

PST Karolína: Definitely, but (…) I don’t think it would save that much time, like it would save a minute or two, but I don’t think it would help me that much, but I have to be careful when the bell is going to ring in a minute, for example, to end even a little earlier and maybe give it to them for homework (…). Jakub doesn’t give homework, so when we finish halfway through the activity, I’d like to tell them to finish it at home, but then I realise that they don’t get homework (…). (Semi-structured interview with PST Karolína)

Karolína distances herself from the advice given by Jakub, who, like other MTs, advises continuing on to the next activity when most of the students in the class have completed the previous one. She reproduces her MT’s advice, which was focused on working with pace, even though she disagrees with it.

The process of reproduction, when a PST’s behaviour changes based on their MT’s advice, was the markedly dominant response to the MTs’ feedback. Our analysis showed that reproduction was occasionally disrupted when, in addition to the mentoring strategy, the PSTs’ learning to teach process was shaped by another strong influence, such as a mentoring style or the MT’s relationship with the mentee.

Discussion

We structure the discussion into three sections. In the first section, we explain that the extent to which the mentoring strategies encourage PSTs to take the needs of individual students into account varies. In response to the first research question, we claim that while strategies addressed by MTs through feedback led PSTs to universalise teaching, strategies addressed through modelling encouraged PSTs to individualise teaching. In the second section we explain why PSTs were shaped by the MT’s feedback more than by the modelling. In response to the second research question, we explain that while feedback was explicit and directive, modelling was implicit and reactive and we discuss this claim. In the last section, we propose the implications for practice, limitations of our research and future areas of study.

Polarity between individuality and universality

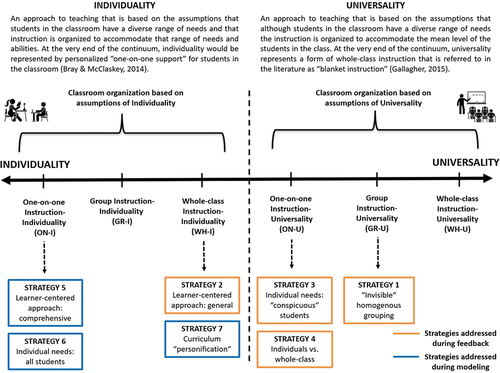

The results of our research suggest that the extent to which individual mentoring strategies encourage the PST to take into account the diverse needs of students varies. It appears that this rate is determined by two criteria: firstly, the organisational form of teaching in the context of which the strategy was applied – one-to-one instruction, group instruction or whole-class instruction (Tomlinson Citation2017); and secondly, the approach to teaching that the strategy encouraged – a universalising approach or an individualising approach. We illustrate the intersection of these two criteria through an Individuality-Universality continuum whose poles represent the minimum and maximum possible degree of consideration of the diverse needs of students ().

The left-hand side of the continuum shows strategies encouraging PSTs towards an individualising approach to teaching (individuality), where the instruction is organised to accommodate a diverse range of needs of each student. The right-hand side of the continuum shows the strategies encouraging PSTs towards a universalising approach to teaching (universality), where the instruction is organised to accommodate the mean level of the students in the class.

We can see that while strategies addressed by MTs through feedback led PSTs to universalise teaching, strategies addressed through modelling encouraged PSTs to individualise teaching. In our diagram we make this contradiction explicit by explaining why some strategies are used by MTs to emphasise universality whereas other strategies emphasise individuality while using the same organisational forms. There are three reasons supporting the interpretation that MTs encourage PSTs to use strategies embedded in organisational forms based on assumptions of universality in their feedback. In explaining these reasons, we refer to the individual strategies, which we rank according to the extent to which they encourage PSTs to universalise.

First, strategy 1, ‘invisible’ homogeneous grouping i.e. the mental division of a class into typically two contrasting groups of students, for example, faster versus slower students, surprisingly may not always encourage PSTs to work with different groups of students in the class to support the individual needs of diverse students. Unlike as conceptualised in the DI framework (Smale-Jacobse et al. Citation2019), this type of grouping may be more a reactive whole-class management strategy e.g. behavioural management of the whole class through the division of students into a group fulfilling the teacher’s instructions versus non-compliant student grouping than sophisticated differentiation based on proactive diagnosis and well-thought-out criteria where students are divided into particular groups. Therefore, we can see this strategy in the position of GR-U on the right side of the continuum emphasising universality in .

Second, strategy 4, in which MTs gave feedback on the relationship between the individual and the class as a whole, usually resulted in the PST being encouraged to prioritise the needs of the majority of students in the class at the expense of the individual. With such feedback, the individual serves as a teacher’s tool to make teaching the whole class more effective. Therefore, we can see this strategy on the ON-U position on the right side of the continuum emphasising universality in .

Third, the feedback that really encouraged PSTs to individualise instruction was mainly about taking the diverse needs of ‘conspicuous’ students into account while typically working with discipline problems (strategy 3, see the position ON-U in the ). With their needs, these students stand out so much from the class as a whole that it is not possible to work with the class without paying increased attention to them. Viewed from the perspective of mastering the class as a whole, guiding PSTs to work with these students can be understood as correcting imaginary extremes in the classroom in an effort to universalise the teaching process. As a result, ‘conspicuous’ students are implicitly labelled and treated differently and thus the learning needs of all students are not equitably or effectively catered for in a truly inclusive manner (cf. Woodcock et al. Citation2022). In addition, although MTs recommend that PSTs individualise through strategy 2, called the ‘learner-centred approach’, which refers to students’ need to be accepted and valued as emphasised within the DI framework (Tomlinson Citation2022), this happens in a rather general and unaddressed way (see position WH-I on the left side of ). This is the only feedback strategy which is based on the assumptions of individuality; however, thanks to its unaddressed nature, it does not represent a strong counter case regarding the above-described pattern.

However, if we look at the MTs’ modelling of practice, as opposed to feedback on practice, we find a different pattern in mentoring with regard to student diversity. Here, MTs encourage PSTs to use organisational forms based on assumptions of individuality in which they demonstrate advanced competencies in working with student diversity. We rank the explanation of the diagram positions of individual strategies applied by MTs in modelling according to the extent to which they encourage PSTs to individualise. Strategy 5 represents a comprehensive learner-centred approach to each classroom student based on detailed knowledge of his/her background and individual needs. It thus falls within the ON-I position on the left-hand side of the continuum emphasising individuality, as does strategy 6, which consists of provision of individual support to all students. These two strategies thus differ from strategy 3 applied in feedback, where individualisation was limited to ‘conspicuous’ students, mainly related to discipline problems. Lastly, Strategy 7 represents ‘personification’ in teaching of civics, where the curriculum, though delivered through the whole class organisational form, is linked to the experiences or characteristics of individual students, which is within the DI framework referred to as students’ interests and learning profile (Tomlinson Citation2017). This is why we place this strategy in the WH-I position on the left-hand side of the continuum emphasising individuality.

Why pre-service teachers were shaped by the mentors’ feedback more than by the modelling

We demonstrated that the extent to which the strategies encourage PSTs to take the needs of individual students into account varies, and while strategies addressed by MTs through feedback led PSTs to take the needs of individual students in the classroom into account less, strategies addressed by MTs through modelling encouraged them to do this to a greater extent. Hobson et al. (Citation2009) point out that it is difficult to determine the direct impact of mentoring because different potential contributors to mentee professional development operate simultaneously. Although we identified a number of influences that affected PSTs, such as mentoring style and MT’s relationship with their mentee (Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020; Hobson et al. Citation2009), we were able to demonstrate that it was specifically the feedback strategies of MTs that decisively shaped PSTs’ thinking and behaviour. In contrast to modelling, the feedback was explicit, which provided PSTs with clear information on how important MTs thought it was to act and think in practice, as well as directive, which implies the demands and urgency of such information. The directive style of mentoring identified in our data corresponds to the prevailing trend among MTs during their practicum (Hennissen et al. Citation2008; Hoffman et al. Citation2015). The strength of feedback was manifested not only in that the PSTs followed what the MTs recommended, but also by the fact that the PSTs usually respected the MTs’ advice even if they did not agree with it (cf. Hawkey Citation1998). Similarly to previous research, we also found that a typical PST’s response to directive feedback, which usually does not provide much room for reflection and creativity, is to reproduce the MT’s style of teaching (Hoffman et al. Citation2015).

Although modelling is considered one of the key ways in which MTs participate in teacher education (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielson Citation2014; Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020), our research shows that in relation to differentiation with respect to students’ needs, MT modelling shaped PSTs only to a limited extent, for two reasons. First, while feedback was addressed explicitly and required by MTs, the strategies applied by MTs in modelling were far more implicit (Loughran Citation1996), which is why we can understand them more as optional, non-directive inspiration for PSTs. In implicit modelling, PSTs have to derive the message from the comments or actions of the MTs themselves, which they are often unable to do (Kang Citation2021). The influence of implicit modelling of differentiation on PSTs is limited (Ruys et al. Citation2013). Second, mentoring modelling strategies did not imprint much onto PSTs’ thinking and behaviour, because the needs of students were taken into account by MTs rather reactively, that is, not based on a proactively planned system of strategies which is one of the defining principles of DI (Tomlinson Citation2017). The reactive nature of differentiation speaks of the MTs’ deep knowledge of the students, on the basis of which such differentiation is possible, although this is difficult for PSTs to attain due to the limited length of their practicum.

PSTs were shaped by their MT’s feedback more than by the modelling, and thus devoted their attention mainly to the topics emphasised by the MTs during feedback. Thus, they learned to universalise rather than individualise teaching. It turns out that it is more important for MTs to help PSTs to learn to work with the class as a whole than to encourage them to differentiate instruction. This interpretation is supported by previous research, which recognised the existence of a hierarchy of importance of topics that MTs raise during mentoring (e.g. Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020; Hennissen et al. Citation2008; Hoffman et al. Citation2015; Moore Citation2003), where less importance tends to be assigned to the topic of addressing diverse individual needs of students. Review studies reveal that MTs are mainly concerned with the instructional and organisational competence of PSTs, such as planning, maintaining order, classroom management (Hennissen et al. Citation2008) or topics related to instruction, organisation and content of teaching (Hoffman et al. Citation2015).

Implications, limitations, future research

When starting their practicum, PSTs are challenged by many pressing issues, such as classroom management, time management, or teaching content. These topics are also prioritised by mentors in dialogues with PSTs (e.g. Hennissen et al. Citation2008; Hoffman et al. Citation2015; Moore Citation2003). MTs should go beyond these most frequently proposed topics, which usually encourage PSTs to work with the entire class as one undifferentiated whole. In the hierarchy of importance of topics addressed by MTs, the topic of student diversity should appear more often, encouraging PSTs to take an individualising approach to teaching.

For PSTs to learn from their MTs to differentiate in order to provide for the needs of all students, mentoring strategies must be based on an individualising approach and on a system of planned differentiation strategies which is proposed by instructional models such as DI (Tomlinson Citation2017). Moreover, MTs should develop a versatile repertoire of mentoring skills, which makes it possible to use both directive and non-directive mentoring styles (cf. Hennissen et al. Citation2008). The directive direction of PSTs towards an individualising approach is desirable, and the application of a less directive style of mentoring can support PSTs in their own initiative to take the individual educational needs of different students into account.

Although research on teacher preparation for diversity was recognised as one of the dominant research trends in the field of teacher education (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016), recent reviews describing existing mentoring approaches (Orland-Barak and Wang Citation2021) and key elements of quality mentoring of PSTs (Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020) do not elaborate the form of mentoring with regard to student diversity in much detail. Based on the discussion of our findings we propose six specific indicators determining quality mentoring with regard to student diversity:

An MT applies an individualising approach to differentiation;

An MT takes the needs of all students into account, not just the needs of some (groups of) students;

An MT applies a versatile repertoire of mentoring skills when addressing student diversity;

An MT models work with student diversity proactively in a planned way and explicitly by explaining actions and thinking;

PST mentor support when working with student diversity is based on a system of differentiation strategies;

The topic of student diversity is an important part of mentoring dialogues.

Despite the fact that an experienced teacher does not necessarily make an effective MT, previous research documented that there is a lack of mandatory systematised programmes preparing MTs for their mentoring role (Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020). We suggest that the proposed indicators of quality mentoring regarding student diversity should inform policy-makers and be inscribed into the mentor training programmes.

The limitation of our study is that we captured students’ perspectives on how they view PSTs as well as how MTs provided for their individual educational needs only indirectly. We did not conduct individual interviews with students and thus their views on addressing their individual educational needs were represented in our data in a rather limited way. We believe that including data from students would provide a more accurate and complex picture of differentiation practices (Coubergs et al. Citation2017).

Because research focused on mentoring with regard to student diversity is rather scarce and not systematically interlinked, we suggest that researchers should put more concerted efforts into this important topic to expand the knowledge base.

In future research multiple methods should be combined, because the research on teacher education and diversity derived evidence mainly from self-reported data focused on PSTs’ and educators’ beliefs, and much less on their practices (Anderson and Stillman Citation2013; Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016).

Conclusion

Mentoring is an important part of teacher education that helps PSTs understand the benefits of differentiation and to be prepared to address the needs of diverse students (Guðjónsdóttir and Óskarsdóttir Citation2019). Our research has contributed to a better understanding of the strategies that MTs use in addressing student diversity and how the way they are applied affects the degree to which they encourage PSTs to consider the individual educational needs of students on their practicum. We believe that the defined quality indicators will help MTs support PSTs in learning to work with student diversity effectively, so that every student can experience success at school and develop their full potential.

Acknowledgments

We are also very grateful to Professor Anthony Clarke for his feedback on our manuscript, which helped us think about elaborating our findings in more depth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Petr Svojanovský

Petr Svojanovský is assistant professor at the Department of Education, Faculty of Education, Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic. His research focus is on teacher education, reflective practice, and student diversity. He specialises in qualitative research methodologies. He has been a member of projects funded by the Czech Science Foundation.

Jana Obrovská

Jana Obrovská is assistant professor at the Department of Education, Faculty of Education, Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic. Her research interests are inclusive education, student diversity and the role of ethnicity and sociocultural disadvantage in the educational process. Methodologically, she focuses on qualitative research, with an emphasis on school ethnography. She has been a principal investigator and participated in projects funded by the Czech Science Foundation as well as international research projects (Horizon 2020). Currently, she is a member of The National Institute for Research on Socioeconomic Impacts of Diseases and Systemic Risks (SYRI).

References

- Achinstein, B., and S. Z. Athanases. 2005. “Focusing New Teachers on Diversity and Equity. Toward a Knowledge Base for Mentors.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (7): 843–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.017.

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. London: Routledge.

- Anderson, L. M., and J. A. Stillman. 2013. “Student Teaching’s Contribution to Preservice Teacher Development: A Review of Research Focused on the Preparation of Teachers for Urban and High-Needs Contexts.” Review of Educational Research 83 (1): 3–69. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312468619.

- Bagga-Gupta, S., M. G. Dahlberg, and A. Gynne. 2019. “Handling Languaging During Empirical Research: Ethnography as Action in and Across Time and Physical-Virtual Sites.” In Virtual Sites as Learning Spaces, edited by S. Bagga-Gupta and M. G. Dahlberg, 331–382. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bowen, G. A. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3): 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304.

- Bray, B., and K. McClaskey. 2014. Make Learning Personal The What, Who, WOW, Where, and Why. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

- Clarke, A., V. Triggs, and W. Nielson. 2014. “Cooperating Teacher Participation in Teacher Education: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Educational Research 84 (2): 163–202. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313499618.

- Cochran-Smith, M., A. M. Villegas, L. W. Abrams, L. C. Chávez-Moreno, T. Mills, and R. Stern. 2016. “Research on Teacher Preparation: Charting the Landscape of a Sprawling Field.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching, edited by D. H. Gitomer and C. A. Bell, 439–547. Washington: American Educational Research Association.

- Cohen, E., R. Hoz, and H. Kaplan. 2013. “The Practicum in Preservice Teacher Education: A Review of Empirical Studies.” Teaching Education 24 (4): 345–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2012.711815.

- Coubergs, C., K. Struyven, G. Vanthournout, and N. Engels. 2017. “Measuring Teachers’ Perceptions About Differentiated Instruction: The DI-Quest Instrument and Model.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 53:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.02.004.

- Czech Statistical Office. 2019. “Školy a školská zařízení - školní rok 2018/2019.” Assessed August 28 2022. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/skoly-a-skolska-zarizeni-skolni-rok-20182019.

- Darling-Hammond, L., J. Oakes, S. Wojcikiewicz, M. E. Hyler, R. Guha, and A. Podolsky. 2019. Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

- Ellis, N. J., D. Alonzo, and H. T. M. Nguyen. 2020. “Elements of a Quality Pre-Service Teacher Mentor: A Literature Review.” Teaching and Teacher Education 92:103072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103072.

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Falzon, M. A. 2009. “Introduction: Multi-Sited Ethnography: Theory, Praxis and Locality in Contemporary Research.” In Multi-Sited Ethnography. Theory, Praxis and Locality in Contemporary Research, edited by M. A. Falzon, 1–24. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Gallagher, K. 2015. In the Best Interest of Students: Staying True to What Works in the ELA Classroom. Maine: Stenhouse.

- Glazer, E. M., and M. J. Hannafin. 2006. “The Collaborative Apprenticeship Model: Situated Professional Development within School Settings.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (2): 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.004.

- Grant, C., and M. Gibson. 2011. “Diversity and Teacher Education: A Historical Perspective on Research and Policy.” In Studying Diversity in Teacher Education, edited by A. F. Ball and C. A. Tyson, 19–61. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Griful-Freixenet, J., K. Struyven, W. Vantieghem, and E. Gheyssen. 2020. “Exploring the Interrelationship Between Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (DI): A Systematic Review.” Educational Research Review 29:100306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100306.

- Guðjónsdóttir, H., and E. Óskarsdóttir. 2019. “´Dealing with diversity´: Debating the Focus of Teacher Education for Inclusion.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (1): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1695774.

- Guillemin, M., and N. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity and “Ethically Important moments” in the Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800403262360.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography. Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Hawkey, K. 1998. “Mentor Pedagogy and Student Teacher Professional Development: A Study of Two Mentoring Relationships.” Teaching and Teacher Education 14 (6): 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00015-8.

- Hennissen, P., F. Crasborn, N. Brouwer, F. Korthagen, and T. Bergen. 2008. “Mapping Mentor Teachers’ Roles in Mentoring Dialogues.” Educational Research Review 3 (2): 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.01.001.

- Hobson, A. J., P. Ashby, A. Malderez, and P. D. Tomlinson. 2009. “Mentoring Beginning Teachers: What We Know and What We Don’t.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (1): 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001.

- Hoffman, J. V., M. M. Wetzel, B. Maloch, E. Greeter, L. Taylor, S. DeJulio, and S. K. Vlach. 2015. “What Can We Learn from Studying the Coaching Interactions Between Cooperating Teachers and Preservice Teachers? A Literature Review.” Teaching and Teacher Education 52:99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.09.004.

- Hudson, P. 2013. “Mentoring Pre-Service Teachers on School Students’ Differentiated Learning.” International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring 11 (1): 112–128. https://rb.gy/bncsji.

- Jarkovská, L., K. Lišková, J. Obrovská, and A. Souralová. 2015. Etnická rozmanitost ve škole. Stejnost v různosti. Praha: Portál.

- Jeffrey, B., and G. Troman. 2004. “Time for Ethnography.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (4): 535–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000237220.

- Joseph, S., and Y. John. 2014. “Practicum Experiences of Prospective Teachers in Differentiating Instruction.” Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 1 (3): 25–34. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.13.136.

- Kang, H. 2021. “The Role of Mentor Teacher-Mediated Experiences for Preservice Teachers.” Journal of Teacher Education 72 (2): 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120930663.

- Loughran, J. J. 1996. Developing Reflective Practice: Learning About Teaching and Learning Through Modelling. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Lunenberg, M., F. Korthagen, and A. Swennen. 2007. “The Teacher Educator as a Role Model.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (5): 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.001.

- Marcus, G. E. 1995. “Ethnography In/Of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1): 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523.

- Marcus, G. E., and M. M. J. Fischer. 1999. Anthropology as Cultural Critique. An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moore, R. 2003. “Reexamining the Field Experiences of Preservice Teachers.” Journal of Teacher Education 54 (1): 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102238656.

- Naidoo, L., and S. Wagner. 2020. “Thriving, Not Just Surviving: The Impact of Teacher Mentors on Preservice Teachers in Disadvantaged School Contexts.” Teaching and Teacher Education 96:103185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103185.

- Nesje, K., and E. Lejonberg. 2022. “Tools for the School-Based Mentoring of Pre-Service Teachers: A Scoping Review.” Teaching and Teacher Education 111:103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103609.

- Novotná, J. 2019. “Learning to Teach in the Czech Republic: Reviewing Policy and Research Trends.” In Knowledge, Policy and Practice in Teacher Education, edited by M. T. Tatto and I. Menter, 39–59. London: Bloombsbury Academic.

- Orland-Barak, L., and J. Wang. 2021. “Teacher Mentoring in Service of Preservice Teachers’ Learning to Teach: Conceptual Bases, Characteristics, and Challenges for Teacher Education Reform.” Journal of Teacher Education 72 (1): 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119894230.

- Pérez-Castejón, D., and M. B. Vigo-Arrazola. 2021. “Investigating the Education of Preservice Teachers for Inclusive Education: Meta-Ethnography.” European Journal of Teacher Education 1–18. online. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.2019702.

- Rowan, R., T. Bourke, L. L’Estrange, J. L. Brownlee, M. Ryan, S. Walker, and P. Churchward. 2021. “How Does Initial Teacher Education Research Frame the Challenge of Preparing Future Teachers for Student Diversity in Schools? A Systematic Review of Literature.” Review of Educational Research 91 (1): 112–158. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320979171.

- Ruys, I., S. Defruyt, I. Rots, and A. Aelterman. 2013. “Differentiated Instruction in Teacher Education: A Case Study of Congruent Teaching.” Teachers & Teaching 19 (1): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.744201.

- Smale-Jacobse, A. E., A. Meijer, M. Helms-Lorenz, and R. Maulana. 2019. “Differentiated Instruction in Secondary Education: A Systematic Review of Research Evidence.” Frontiers in Psychology 10:2366. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02366.

- Tomlinson, C. A. 2017. How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms. 3rd ed. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Tomlinson, C. A. 2022. Everybody’s Classroom: Differentiating for the Shared and Unique Needs of Diverse Students. Washington: Teachers College Press.

- Wang, J., and S. J. Odell. 2002. “Mentored Learning to Teach According to Standards Based Reform: A Critical Review.” Review of Educational Research 72 (3): 481–546. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072003481.

- Whitaker, M. C., and K. M. Valtierra. 2018. “Enhancing Preservice Teachers’ Motivation to Teach Diverse Learners.” Teaching and Teacher Education 73:171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.004.

- Woodcock, S., U. Sharma, P. Subban, and E. Hitches. 2022. “Teacher Self-Efficacy and Inclusive Education Practices: Rethinking Teachers’ Engagement with Inclusive Practices.” Teaching and Teacher Education 117:103802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103802.

Appendices Appendix A.

Additional Examples of Data Excerpts Illustrating Important Findings Related to the First Research Question

Appendix B.

Additional Examples of Data Excerpts Illustrating Important Findings Related to the Second Research Question