ABSTRACT

This study compared visual art teachers’ experiences of generic early-career professional identity dilemmas with experiences of dilemmas arising from subject-specific concerns. In turn, their experience of generic dilemmas was compared with experiences of non-arts teachers, as found in literature. Results show, on average, art teachers experienced considerably more dilemmas than non-arts teachers. No conclusive evidence was found for more frequent, or stronger experience of arts-specific dilemmas. Our data does, however, concur with descriptions of art teacher identity dilemmas found in qualitative arts education research, suggesting that some generic early-career dilemmas may become conflated with subject-specific concerns. For example, art teachers may focus more on students expressing their emotions than other teachers. In uncovering how these teachers might use subject-specific framing when interpreting generic dilemmas, this research invites teacher educators to consider how the subject one teaches may have deeper, and more complex connections to early-career dilemma experiences than previously recognised.

Introduction

There is general agreement that forming a professional teacher identity is a complex and dynamic process requiring continuous intellectual, social and emotional engagement from new teachers (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009; Beijaard and Meijer Citation2017). Early in their careers, beginning teachers often struggle with their desire to sustain an idealised version of the teacher they want to become while adjusting to the day-to-day demands placed on them by an environment that may already regard them as fully formed professionals (Hong, Day, and Greene Citation2018; Schaap et al. Citation2021). Geijsel and Meijers (Citation2005) described early-career teaching as a period of identity learning predicated on processes of self-interpretation that can be experienced both positively and negatively. In their work examining the coping strategies beginning teachers use as they form a professional teacher identity, Pillen, Beijaard, and den Brok (Citation2013) described 13 generic early-career teacher identity tensions. They did not, however, investigate contextual factors that might conflate with teacher identity leading to an increase in tension experiences. For example, is there a relationship between the school subject one teaches and experiences of early-career professional identity tensions? In secondary schools, the specialist knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours associated with subject expertise, or an academic discipline are used by groups of teachers to guide their actions and promote their sense of professional affiliation (Anstead, Goodson, and Mangan Citation2002; Goodson and Hargreaves Citation1996). The relative importance of the subject in a curriculum, and mainstream schooling more generally, can also be a key contributing factor to how teachers identify with the teaching profession as a whole (Day et al. Citation2006; Ragnarsdóttir and Jónasson Citation2020).

For visual art teachers, who have been educated in the practices, knowledges and discourses of both artists and teachers, professional teacher identity formation can be problematic. Artistic skill is widely regarded by society as a personal characteristic one is born with, while teaching skill appears instrumentalised, or something to be learned (Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013). Allied to this, there is a general perception that an art teachers’ classroom practices are different from other school subject classroom practices. In formal educational settings, artist identity and teacher identity can seem divergent, leading in some cases to misconceptions around intentions and behaviours (Kenny and Morrissey Citation2020). Beginning visual art teachers also undergo a significant (re)organisation of their ideas about professional practice as their primary focus moves from their artistic skill to their teaching skill after graduation (Hatfield, Montana, and Deffenbaugh Citation2006; Scheib Citation2006).

This study explores the complexity of subject-specific and generic perspectives on the experience of professional teacher identity tensions using the term ‘dilemmas’ because it reflects the multiple professional identity positions that visual art teachers, as teachers with highly developed expert skills in the arts, bring to their work in schools. Dilemmas can be experienced at the interpersonal level of relationships at school and the intrapersonal level of professional teacher identity but are most often triggered by the specific (new) activities and situations that early-career teaching presents (van der Wal et al. Citation2019). For example, Varelas, House, and Wenzel (Citation2005) discussed how beginning science teachers struggled with the contrast between a scientist identity that knows ‘messiness’ is part of doing science and a teacher identity that wants to keep classroom learning orderly and structured. The extent to which the experience of dilemmas becomes conflated with subject-specific concerns, or subordinated to a subject-specialist identity, remains a grey area in teacher identity research. In this study, we contrast what have been framed as generic early-career dilemmas with the experience of dilemmas that appear to emanate from subject-specific concerns.

Earlier research

To better understand the potential for visual art teachers to experience dilemmas during early-career, we began our study with a review of the existing literature on teacher identity formation from generalised and subject-specific perspectives.

Teacher identity formation and early-career experiences

Research on teacher identity has established that the process of becoming a professional teacher is incremental, building on one’s personal biography, and situational, as one experiences teaching as a profession and the school as a professional space (Kelchtermans Citation2009). Early research on teacher identity by Beijaard, Verloop, and Vermunt (Citation2000) highlighted the importance of the personal knowledge that teachers use to configure their subject matter, pedagogy and didactics in their classroom teaching. Developing this person focussed approach, studies by Lamote and Engels (Citation2010) and Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (Citation2017) have gone on to show that teachers can experience decreased perceived agency when their own interpretations of what is desirable and possible in a classroom setting does not match the expectations of their students or school. For new teachers, sensing they have little agency can result in a strong personal, emotional response to encounters at work that can lead to difficulty identifying with teaching as a profession (Heikonen et al. Citation2017; cf.; Hokka et al. Citation2017). Even common situations such as keeping order in a classroom can be experienced as a dilemma if a beginning teacher feels they must act in ways that seem deeply unnatural to them personally (M. T. Pillen Citation2013).

In their meta-analysis of research on early-career teaching, Pillen, Beijaard and den Brok (Citation2013, 663) conceptualised a professional identity tension as an instance ‘containing a conflict between the teacher as a person and the teacher as a professional’. Their subsequent study of beginning teachers’ coping strategies described 13 tensions commonly experienced in early-career teaching. In that research they did not, however, make a distinction between teaching setting (primary or secondary) or the subject specialism of the teacher. Separate studies in Israel (Popper-Giveon and Shayshon Citation2017) and Australia (Morris and Imms Citation2021) have recently shown that teachers in education, and beginning teachers, can become preoccupied with notions of generalised teacher behaviours and teacher concerns at the expense of developing themselves as a subject specialist.

School subject–specific teacher identities

Professional identity as a subject teacher encapsulates Gee’s (Citation2000) institutional identity perspective and affinity identity perspective, as well as Beijaard, Verloop, and Vermunt’s (Citation2000) dimensions as subject expert, didactic and pedagogue (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström Citation2019). The relationships between school teaching and academic and vocational higher education have produced distinctive subject area cultures and sub-cultures encompassing the practices, as well as the expectations and social positioning, associated with an area of study (Goodson and Hargreaves Citation1996; Ragnarsdóttir and Jónasson Citation2020). Identification with these subject area cultures can be so strong that, as some experienced teachers reported in research by Anstead et al. (Citation2002, 113), teaching seems to ‘come naturally’ and that teaching style is ‘an extension of the personality of the teacher’.

Interest, talent and personal experience as a learner in a subject are all commonplace reasons for becoming a teacher, alongside the desire to work with children and young people (Heffernan et al. Citation2017; Richardson and Watt Citation2016). Despite this, teachers do differ in their level of identification with the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours associated with the perceived expertise in a subject, as Chung-Parsons and Bailey (Citation2019) discussed in their study of science teacher identity. Among the science teacher interns they interviewed, a hierarchy of professional identity positions emerged. Two participants said they felt their science identity was ‘who they are’ and their teacher identity was ‘what they did’, while another participant identified most strongly with their teacher identity because they believed that simply ‘enacting scientist behaviours does not make you a scientist’ (Chung-Parsons and Bailey Citation2019, 43).

The status of a school subject has also been found to have negative and positive impacts on subject-specific teacher identity. Bleazby (Citation2015) identified that it is widely accepted that mathematical and physical sciences knowledge is afforded a higher status than applied knowledge in a traditional curriculum for secondary education. Even so, as Ragnarsdóttir and Jónasson (Citation2020) found, elite subject status can be problematic for some teachers during the formation of their teacher identity. Research by Lutovac and Kaasila (Citation2017) pointed out that a mathematics teacher identity can be stunted by narrowly focussing on ‘masterly’ ability and not engaging with the gender, racial and socio-economic profiles of teachers. In contrast, Watters and Diezmann (Citation2015) reported that some career-change science teachers found it difficult to cope with the lack of status afforded to them personally by colleagues without their level of academic or industry expertise, and by the students who did not share their interest in the subject. By comparison, research has shown some physical education teachers develop strong teaching identities despite believing that others regard their subject as simply providing relief from more rigorous academic subjects (Richards et al. Citation2018). A key factor for positive teacher identity development among these physical education teachers appeared to be social connections at school that led them to feel they mattered as teachers. Being recognised by colleagues as a subject specialist has also been identified as a factor in teachers’ decision to stay in the profession (Morris and Imms Citation2021). Summing up, navigating teacher identity as a subject specialist can require significant personal investment in relationships at school, with success or failure being closely linked not only to an ability to recognise yourself as an expert in a subject but also to having this expertise confirmed and valued by others.

Teaching art in secondary schools

The beliefs, values and ways of learning promoted in higher arts education sometimes conflict with the professional beliefs, values and teaching approaches found in mainstream schooling (Adams Citation2007; Blair and Fitch Citation2015). Separate studies in the United States and Finland have pointed to a belief among visual art teachers that conservative and hierarchical approaches to teaching and learning are embedded in the teacher role (Hatfield, Montana, and Deffenbaugh Citation2006; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013). Just the same, the few empirical studies that specifically discuss the day-to-day realities of teaching art in secondary schools report that visual art teachers experience similar stresses and problems to those found among beginning teachers in other school subjects. Visual art teachers have reported feeling unsure about curriculum development, classroom management and their subject knowledge (Haanstra, van Strien, and Wagenaar Citation2006; Unrath, Anderson, and Franco Citation2013). Echoing Alsup’s (Citation2006) classic case study of teacher identity formation, some visual art teachers also find that normative ideas about how teachers look and act make them feel uncomfortable at school. For example, teacher interns in a study by Adams (Citation2007) reported that gender, dress and appearance could be an issue inside, and outside the classroom. Visual art teachers also believe their subject has a low status in schools. They cite poor facilities, difficult timetabling and the general attitude of colleagues, students and parents that art is ‘just for fun’, as evidence that the subject is not regarded as central to educational or societal missions (Cohen-Evron Citation2002, 273; Downing and Watson Citation2004; Scheib Citation2006). It can also be difficult for some art teachers to come to terms with the lower status afforded to artistic expression and expertise because this contrasts so significantly with the higher status this expertise received during their own teacher education in art colleges, or specialist art departments of universities (Blair and Fitch Citation2015; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013; Scheib Citation2006).

In the existing literature on art teaching in schools, one problem that seems to be unique to these teachers is the profound sense of isolation they experience. Sometimes this is related to a practical reality of being the only art teacher in a school (Cohen-Evron Citation2002; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013) however, more often this isolation is framed as a problem of identification. Some visual art teachers say they feel ‘like an outsider’ in the school community (Adams Citation2007; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013; Thornton Citation2011), while others intentionally set themselves apart because they find it important to take an activist stance that openly questions attitudes they find in their school regarding social justice issues (Acuff Citation2018; Cohen-Evron Citation2002; Hoekstra Citation2015). This implies, for art teachers at least, that feeling like an outsider can be experienced as a personal existential problem and a declaration of professional autonomy.

It is also interesting to consider the difference between research on generalised teacher experience that recognises personality, communicative capability and support at school frame the experience of professional identity formation (e.g. M. Pillen, den Brok, and Beijaard Citation2013; Schaap et al. Citation2021) and the tendency in arts education studies to reify artistic sensibility. Over the past 30 years, studies of art teachers have mostly relied on dichotomising artist and teacher identity and problematising the school environment as a location for working in the arts (e.g. Adams Citation2007; Cohen-Evron Citation2002; Hatfield, Montana, and Deffenbaugh Citation2006; Thornton Citation2011). For beginning art teachers, this overt emphasis on professional interpretations of arts practice may be a source of dilemmas in ways similar to those reported by Watters and Diezmann (Citation2015) in their study of career-change scientists. Being required to give equal, and in some cases more, attention to didactics and pedagogy instead of subject expertise may be difficult for some individuals.

Based on existing research, it can be surmised that the subject one teaches, and the professional behaviours associated with it, may have deeper connections to individual experiences of dilemmas than might be recognised during teacher education or early career. To understand this better, we set out to examine the differences and similarities in visual art teachers’ experience of subject-specific versus generic early-career dilemmas guided by the following research questions:

Which early-career teacher identity dilemmas do beginning visual art teachers experience and what is the magnitude of their dilemma experience?

What differences exist between beginning visual art teachers’ experience of arts subject –specific dilemmas and their experience of generic early-career identity dilemmas?

To what extent does the average experience of the generic early-career dilemmas differ between beginning visual art teachers’ and beginning teachers from other school subjects?

Contextualisation

In the context of this research, it is important to note that all Dutch art teachers are educated in specialist Universities of the Arts to practice as artists and teachers. Their bachelor degree qualifies them to teach in primary to tertiary level education. By contrast, most other Dutch teachers follow bachelor or master programmes in Universities of Applied Science where subject content knowledge is treated as a specialisation within a broader professional teacher qualification that licences teachers for secondary and vocational level education settings.

Methods

For this research we augmented Pillen’s cross-sectional survey model with subject-specific dilemma descriptions. In total, 14 dilemmas were presented to beginning visual art teachers (see Appendix 1). Ten of these dilemmas represented generic early-career dilemmas taken directly from Pillen (Citation2013), which, in some cases, were adapted to reflect the in-service secondary school contextual focus of this study. Four dilemmas addressed subject-specific teaching issues identified in the arts education literature. One of these was originally a generic early-career dilemma that addressed a teacher’s perception of the level of their subject knowledge. The other three arts subject – specific dilemmas covered the issues: (1) difficulty in seeing oneself as a professional schoolteacher (Adams Citation2007; Blair and Fitch Citation2015; Hatfield, Montana, and Deffenbaugh Citation2006), (2) frustration with the status and position of the arts in schools (Cohen-Evron Citation2002; Hatfield, Montana, and Deffenbaugh Citation2006; Scheib Citation2006) and (3) subject-specific pedagogical aims that appear incompatible with general aims and approaches in schools (Adams Citation2007; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013; Thornton Citation2011).

The decision to gather data on the experience of generic and arts subject–specific dilemmas using a quantitative tool was based on two methodological considerations. In the first place, we know from the existing body of mainly qualitative and contemplative arts education research that this group of teachers is prone, from initial teacher education onwards, to struggle with feelings of inadequacy relating to their professional identities as teachers and as artists (Blair and Fitch Citation2015). Nonetheless, the near absence of visual art teachers in wider teacher identity formation research confounds comparison with the experiences of non-arts teachers. Secondly, closed questions have been chosen over open questions to reduce the response burden of a longer completion time and potential confusion about the overall intentions and goal of the research (Rolstad, Adler, and Rydén Citation2011).

The survey instrument was piloted on three consecutive occasions. The first pilot was conducted with art teacher educators with knowledge of the research subject and wide-ranging experience with the target group. This group pointed out that Pillen’s term ‘tensions’ could be interpreted by beginning visual art teachers as a negative pre-judgement of their teaching competences. For the next pilot, we applied the more expansive term ‘dilemmas’ to the descriptions and asked experienced secondary school visual art teachers to assess the dilemma descriptions, the order of the questions in the survey and the distribution protocol. The final online version of the survey was tested by researchers, teachers and students in the researchers’ network.

Procedure

Graduates of visual art and design teacher education programmes were chosen as the sample population. Seven undergraduate visual art and design teacher education programmes distributed the survey to their alumni in accordance with European Generic Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). With such a narrowly defined target population, we aimed for quality of response over quantity of response (Ganassali Citation2008). Our main concern regarding reliability was completeness of response (Ganassali Citation2008) and homogeneity of response (Baarda et al. Citation2017). To achieve this, background questions were placed at the start of the survey to enable respondents who did not fit the sample profile to opt out early on. This strategy appears to have been successful because the highest rate of dropout occurred at, or directly after, the sampling criteria question that asked how many months a respondent had been in employment as a secondary school art teacher.

Ethics approval was obtained from the researcher’s institution before the research was conducted. The online questionnaire opened with a statement about the aims of the research, data storage and data usage so that respondents could give informed consent.

Participants

In this research ‘beginning visual art teacher’ refers to a respondent who has been teaching visual art in a secondary school setting for no more than three years. Age and teaching experience in another school subject were not considered barriers to participation in the research because of the diversity of pathways into visual art teaching. In total, 109 teachers responded to the survey, representing 33% of the estimated sample population of visual art teacher graduates. After an initially high early opt-out rate of 44%, 61 respondents completed the section on current work situation and started the second part of the survey about dilemma experiences. From here, opt-out rates reduced quickly and 50% of the response data, representing 18% of the estimated sample population, were counted as fully completed surveys (n = 54). The majority of the respondents were female (93%). The respondents’ ages ranged from 21 to 59 years, with an average of 32 years. Nearly three quarters (74%) of the respondents reported that they actively participate in making art and cultural activities alongside their employment as a secondary school teacher.

Comparative data set

To make comparisons between the early-career dilemma experiences of visual art teachers and teachers of other subjects, data on secondary school teachers were extracted from Pillen’s original data set (2013) using the control variable ‘teach in secondary education’.Footnote1 This produced data from 39 teachers, none of whom taught an arts subject. Respondents in this sample ranged in age from 22 to 54 years, with 59% being under 30 years of age (in the newly qualified visual art teacher sample, 63% are under 30 years of age). The proportion of males (36%) to females (64%) in the comparative data set was more balanced than in the visual art teacher sample.

Data analysis

Summary statistics were produced for the beginning visual art teachers’ experiences of all 14 early-career dilemmas and the magnitude of each experience. Frequency distributions were used to answer research question one and part of question two. Additionally, for question two, independent-groups t-tests compared the average experience of the arts subject–specific dilemmas with the average experience of the generic early-career dilemmas. Finally, to answer question three, independent-groups t-tests were performed to test the hypothesis that there would be differences between the newly qualified visual art teachers’ experiences of the generic early-career dilemmas and the experiences of their counterparts from non-arts subjects.

Results

The results are presented in three parts. Parts one and two provide the findings from our survey of beginning Dutch visual art teachers’ early-career dilemma experiences. In part three, by comparing our survey data with data drawn from Pillen’s original data set, we test the hypothesis that visual art teachers’ experiences of early-career generic dilemmas would differ from the experiences of teachers from other subjects.

Dilemmas experienced by beginning visual art teachers

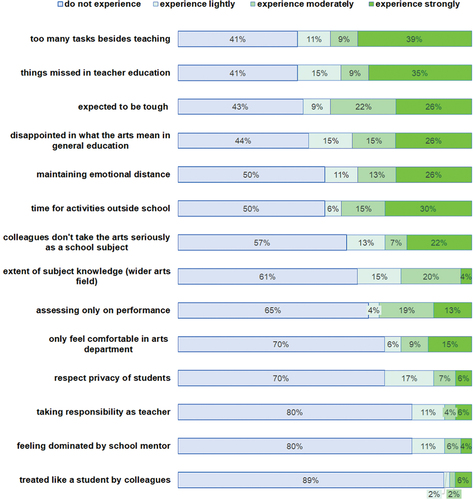

shows the visual art teachers’ experiences of the 14 dilemmas, and the average magnitude of these experiences. Teachers experienced an average of between five and six of the early-career dilemmas, while the range of dilemmas experienced was 0 to 12. Six of the fourteen dilemmas were experienced by 50% or more of the visual art teachers and only one dilemma by fewer than 15% of the visual art teachers.

Table 1. Beginning visual art teachers’ experiences of 14 early-career dilemmas and the magnitudes of these experiences (N = 54). The order of the dilemmas represents the most to least frequently experienced dilemmas, not the order the dilemma descriptions appeared in the survey.

The most frequently experienced dilemmas were too many tasks besides teaching (59%); things missed during teacher education (59%); expected to be tough (57%) and disappointed in what the arts mean in general education (56%). Turning to the magnitude of experience, the median score for six dilemmas was ‘strongly’. These were: maintaining emotional distance; new in department, treated like a student by colleagues; time for activities outside of school; too many tasks besides teaching; things missed during teacher education and colleagues do not take the arts seriously as a school subject. Of the remaining eight dilemmas, five were experienced ‘moderately’ and three ‘lightly’; however, the standard deviation across all 14 dilemmas ranged between 0.644 and 0.905, suggesting considerable variability in the magnitude of dilemma experiences in this sample population of visual art teachers. illustrates the magnitude of experience for each dilemma as a proportion of the total sample.

Comparison of the beginning visual art teachers’ experiences of arts subject– specific dilemmas and their experiences of generic early-career dilemmas

Research question two examined differences in the beginning visual art teachers’ experiences of arts subject–specific dilemmas and the generic early-career dilemmas. In total, there were four arts subject–specific dilemmas and ten generic early-career dilemmas. Surprisingly, 26% (n = 14) of the visual art teachers experienced none of the arts subject–specific dilemmas described. In contrast, only one of the visual art teachers reported experiencing none of the generic early-career dilemmas. Taken as proportions of the possible number of dilemmas that could be experienced in each category, on average, individual teachers experienced 42% of the arts subject – specific dilemmas (M = 1.67, SD = 1.12) and 43% of the generic early-career dilemmas (M = 4.31, SD = 1.69).

The magnitude of experience showed that six of the ten generic early-career dilemmas had a mode of ‘strongly’; however, the average magnitude across all 10 generic dilemmas remained closer to ‘moderately’ (M = 2.16, SD = .354). Three of the four arts subject–specific dilemmas also had a mode of ‘strongly’, although again, the average magnitude remained closer to ‘moderately’ (M = 2.11, SD = .271). Notably, only the arts-related dilemma disappointed in what the arts mean in general education (n=30) could be included in the six dilemmas experienced by at least 50% or more of respondents. There were also noteworthy differences in the magnitude of experience within the arts subject–specific dilemmas. For example, although the dilemma only feel comfortable in arts department was only experienced by 30% of the art teachers, it was, proportionally, the arts dilemma that was experienced most strongly (M = 2.31, SD = .793). A cross-case comparison showed that 56% of the teachers that experienced only feel comfortable in arts department also experienced the dilemma colleagues do not take the arts seriously as a school subject. Subsequent chi-square tests showed no significant relationship between age and the experience of either arts subject–specific or generic dilemmas. Overall, no conclusive evidence of a significant difference between the frequency or magnitude of the experience of arts subject–specific dilemmas compared with the experience of the generic early-career dilemmas was found.

Comparisons of generic early-career dilemma experience between beginning visual art teachers and beginning teachers from other subjects

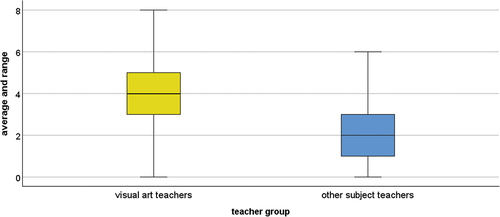

The final question in this study looked at the similarities and differences between how beginning visual art teachers and beginning teachers from other school subjects experience the generic early-career dilemmas. As explained earlier, comparative data for the generic early-career dilemmas were available for a random group of secondary school teachers (M. T. Pillen Citation2013), enabling us to analyse data from 93 teachers (54 visual art teachers and 39 teachers of other subjects). Summary statistics for the entire sample showed that the experience of the early-career generic dilemmas ranged between 0 and 8, and that an average individual experienced between 3 and 4 dilemmas. Looking at each group of teachers separately, the box plots in illustrate the significant difference between the average number of generic early-career dilemmas experienced by beginning visual art teachers and beginning teachers in other school subjects.

Figure 2. Range and average number of generic early-career dilemmas experienced by each teacher group (54 visual art teachers and 39 teachers of other subjects).

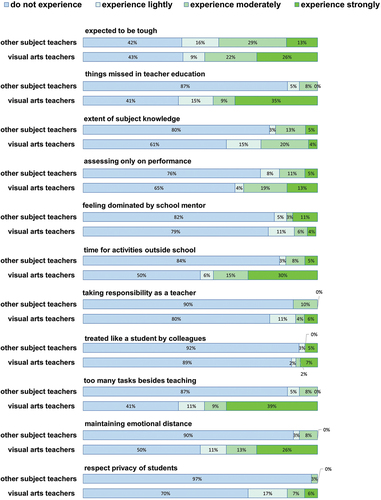

It is evident that newly qualified visual art teachers do experience more of the generic early-career dilemmas than their counterparts in other subjects and, as illustrates, there are similarities and differences between the magnitudes at which these dilemmas are experienced by the two teacher groups.

Figure 3. Comparison of the magnitude of experiences of the generic early-career dilemmas as a percentage of the response by each teacher group (54 visual art teachers and 39 teachers of other subjects).

The results from independent-groups t-tests indicated significant differences between the dilemma experiences of the two groups, such as for too many tasks besides teaching (visual art teachers M = .59, SD = .496; other subject teachers M = .13, SD = .339; t (91) = 5.05, p < .01), maintaining emotional distance (visual art teachers M = .50, SD = .505; other subject teachers M = .10, SD = .307; t (91) = 4.36, p < .05) and respect privacy of students (visual art teachers M = .30, SD = .461; other subject teachers M = .03, SD = .160; t(91) = 3.51, p < .01). The t-tests also revealed that visual art teachers experience the time they have for activities outside of school as a dilemma significantly more frequently than their peers from other subjects (visual art teachers M = .50, SD = .505; other subject teachers M = .21, SD = .409; t (91) = 3.00, p < .05). The effects size was determined using Hedges’ g as a control against possible bias caused by unequal sample sizes. Large effects sizes supported the significant difference found for the dilemmas too many tasks besides teaching (1.05) and maintaining emotional distance (0.92). Medium effects sizes were calculated for the dilemmas respecting student privacy (0.74) and time for activities outside of school (0.62).

As was the case when the nominal variable ‘experience dilemma’ was used for the independent-groups t-tests, comparisons of the ranked mean scores for dilemma experience confirmed the significant difference in the way visual art teachers experienced maintaining emotional distance, respecting privacy of students, too many tasks besides teaching and time for activities outside school. In addition, the t-test using the ranked scores showed that visual art teachers differed significantly from teachers of other subjects in their experience of things missed in teacher education (t (91) = 2.275, p < .025); Hedges’ g also indicated a large effects size (1.20). Overall, the results of the comparative tests supported the hypothesis that there are significant differences between the beginning visual art teachers’ experience of the generic early-career dilemmas and those of their counterparts teaching other school subjects.

Discussion

Our first question addressed the beginning visual art teachers’ experiences of the 14 early-career dilemmas and produced conclusive evidence that these dilemmas are indeed experienced, but also that there is considerable variance in the number of dilemmas experienced by individual teachers and the magnitude of those experiences. Based on frequency and magnitude, our second question that compared the visual art teachers’ experience of arts subject–specific dilemmas and generic dilemmas produced a negative result. Indeed, 26% of visual art teachers did not recognise their experiences in any of the arts dilemmas as they were presented. Nevertheless, these quantitative results for the arts dilemmas do provide further support for earlier qualitative research claims made about visual art teacher identity. For example, the dilemma only feel comfortable in arts department explicitly positions visual art teachers as a group that sees itself as different from other schoolteachers. While the number of teachers who reported they experienced this dilemma was just under one third of the sample, proportionally this dilemma was experienced more strongly than any of the other arts subject–specific dilemmas. Furthermore, the results confirm that the status and position of the arts in schools is a source of dilemma for visual art teachers. Whether it is a perception that colleagues do not take the arts seriously as a school subject or being disappointed in what the arts mean in general education, a substantial group of visual art teachers find interactions with their school community problematic. As Cohen-Evron (Citation2002) and Määttä and Uusiautti (Citation2013) have suggested, feeling isolated in the school community can lead to art teacher attrition. A better understanding of the range of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors that contribute to isolation could help these teachers realise social connections at school that provide them with a sense that they matter, even though their subject may not be seen as a core subject in the wider school community (Richards et al. Citation2018).

The proportion of females (93%) in our data set was somewhat higher than that found in the target sample population of visual art & design teacher graduates (83% female and 17% male respectively), but considerably higher than the proportions found in the non-arts population of Dutch teacher education graduates (57% female and 43% male respectively). In her research exploring the relationship between art, education and gender, Hopper (Citation2015, 128) describes art teaching in schools as part of ‘hidden-stream’ arts production and suggests that there may be a relationship between the marginalised position of the arts in schools and a predominantly female workforce. While this research did not address gender specifically, the potential intersectionality of gender and the status and position of the arts in schools should be part of future dialogue around curriculum development in visual art teacher education.

Turning to our hypothesis, the data provides ample evidence that the beginning visual art teachers’ experience the generic early-career dilemmas differently relative to their counterparts in other subjects. The visual art teachers experience almost twice as many of the early-career generic dilemmas as a random group of beginning secondary school teachers and we identified significant differences in the magnitude of these experiences. Proportionally, similarities were found in experiences across the groups for the dilemmas expected to be tough and things missed in teacher education, which emphasises the need for adequate teacher induction for new teachers in all subjects. A noteworthy difference between the groups is that the visual art teachers more often experience the dilemma maintaining emotional distance, and experience it at a significantly higher magnitude. This finding seems to suggest, modestly, that art teachers experience their emotional connection to students as a dilemma. One possible explanation could be that arts teaching often involves asking students to express their inner world, including feelings, because this is regarded as a cornerstone of creative pedagogies and a condition of art classroom practices that aim to stimulate students’ production of original work (Hall and Thomson Citation2017). Having done so, visual art teachers must then evaluate the affective, emotive and experiential dimensions of a students’ artistic work alongside technical skill and visual coherence (Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013). To do this requires not only expert skills in working with the materials of art making, visual art teachers must also learn to reflect on how their own personal characteristics and well-being affects their pedagogy. There are many non-subject-specific studies that discuss the importance of teacher emotions and the impacts they can have on pupil learning, working relationships and teacher identity formation more broadly (Uitto, Jokikokko, and Estola Citation2015) that visual art teacher education could draw on to develop subject-specific research in this area.

The marked difference between the groups’ experience of the dilemmas too many tasks besides teaching and time for activities outside school also invites more study. Having been educated separately in specialist Universities of the Arts, these visual art teachers would not have been exposed to discussions about the generalities of teacher work from a number of school subject perspectives. Many school subject curricula have long histories and are highly structured, providing beginning and novice teachers with ready-made teaching materials and clear periodic goals to guide their work (Anstead, Goodson, and Mangan Citation2002). In contrast, visual art generally has more loosely defined goals and it is more common than not that art teachers are expected to regularly develop new assignments and lesson materials based on contemporary art trends or their own developing artistic interests (Heijnen Citation2015). Consciously or unconsciously, the development of original lesson materials may be a way for visual art teachers to demonstrate their subject expertise to colleagues and students (Morris and Imms Citation2021; Scheib Citation2006). Using their artistic skills in this way could also reinforce these teachers’ belief that they are connected to a field that surpasses the school subject (Chung-Parsons and Bailey Citation2019). Our results seem to infer that visual art teachers’ experience of tasks other than classroom teaching and time as it relates to personal choices, could be an extension of an intrinsic desire to foreground concerns allied with professional art practices at the start of their careers. This adds an additional dimension to existing questions around a focus on generalised teacher behaviours at the expense of subject specialism found in some teacher education research (e.g. Morris and Imms Citation2021; Popper-Giveon and Shayshon Citation2017).

The more frequent and strong experience of the generic early-career dilemma maintaining emotional distance aligned with the arts subject–specific dilemma disappointed in what the arts mean in general education found in the visual art teacher group is also interesting in that it could be an internalisation of arts education discourse. Arts education literature often claims that the general approaches to teaching and learning found in schools are incompatible with arts subject-specific pedagogical aims and practices (Adams Citation2007; Atkinson Citation2012; Määttä and Uusiautti Citation2013). Furthermore, the significant difference in the experience of the dilemma time for activities outside of school might well be explained by the visual art teachers’ extramural involvement in arts-related activities outside of school, such as regularly visiting exhibitions and arts events, making their own artwork, or teaching art in informal settings such as arts centres or arts studios.

From our study, we can conclude that our between-group comparisons of dilemma experience present the possibility that some generic early-career dilemmas may also be interpreted through arts subject–specific themes or lenses. However, it is clear from our research, that the manner in which individual visual art teachers respond to conditions surrounding their subject at school does require more research. The mixed results found in this survey suggest that interactions between the professional identities visual art teachers bring to their teaching needs closer examination. Hatfield et al. (Citation2006) have proposed strategies to ‘manage’ the two identities through prioritisation, separation or balancing. Cohen-Evron (Citation2002), however, had already suggested that individual art teachers may choose a strategy of claiming and fore-fronting the otherness of an artist identity rather than experience alienation or irrelevancy in the workplace. Feeling like an ‘outsider’ can therefore exist as a personal problem or be a professional statement, which offers an interesting example of the multiplicity, discontinuity and social nature of professional teacher identity (Akkerman and Meijer Citation2011).

Our results support a view that the subject one teaches, the professional behaviours associated with it and the ability to identify as someone who embodies the subject rather than someone who has only knowledge of the subject, may have deeper connections to the experience of teacher identity dilemmas in early career than previously recognised. For art teacher education specifically, the research points towards the need to give more attention to the interaction of multiple professional identities during initial teacher education and in this way help visual art teachers transcend the simple dichotomy of artist identity versus teacher identity. More broadly, this new knowledge, which contributes to our understanding of the early-career dilemma experience of teachers with highly developed subject knowledge and subject identification, also raises new questions about how subject-specific framing may be at work within generalised early-career professional teacher identity dilemma experience. While research on visual art teacher professional identity formation remains ongoing, we see the potential to replicate our approach with other arts subject teachers, second-career teachers with industry- and professions-based expertise and university graduates in postgraduate teacher education.

In closing, we wish to acknowledge that having access to Pillen´s original data set widened the scope of this survey exploring the early-career dilemma experience of Dutch visual art teachers immeasurably. It is an example of how data sharing, when conducted responsibly, benefits new scholarship. Equally, we recognise the limitations of using an older data set from research that was not designed with subject-specific concerns in mind. We are also conscious that the relatively small size of our own data set prevents any generalisation to visual art teachers as a population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maeve O’Brien Braun

Maeve O’Brien Braun, BFA, MA, is a lecturer, and teacher placement supervisor at ArtEZ University of the Arts, Arnhem, The Netherlands. Her multidisciplinary teaching work centres around the professional development of artists as makers, educators, and researchers.

Ida E. Oosterheert

Ida Oosterheert, PhD., is associate professor ‘teacher learning and development’ at the Radboud Teachers Academy, at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. She is a senior teacher educator and supervises (PhD)-research around teacher education and teacher learning, with a specific interest in the cultivation of creativity in education.

Edwin van Meerkerk

Edwin van Meerkerk, PhD., is full professor cultural education at the department of Modern Languages and Cultures at Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. His research focuses on arts and cultural education, cultural policy, and higher education for sustainability. He is also endowed professor Social and Cultural Sustainability at ArtEZ University of the Arts and a Leadership fellow in the Comenius Programme for Educational Innovation in Higher Education.

Paulien C. Meijer

Paulien Meijer, PhD., is full professor teacher learning and development at the Radboud Teachers Academy, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Together with her research team, she publishes on the broad area of teacher education and teacher learning, with specific attention for the cultivation of creativity in education. She is member of the International Forum on Teacher Educator Development (InFo-TED) and vice-chair of the Dutch national committee responsible for university-based teacher education in the Netherlands.

Notes

1. With permission of the researcher.

References

- Acuff, J. B. 2018. “‘Being’ a critical multicultural pedagogue in the art education classroom.” Critical Studies in Education 59 (1): 35–53.

- Adams, J. 2007. “Artists Becoming Teachers: Expressions of Identity Transformation in a Virtual Forum.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 26 (3): 264–273.

- Akkerman, S. F., and P. C. Meijer. 2011. “A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity.” Teaching & Teacher Education 27 (2): 308–319.

- Alsup, J. 2006. Teacher Identity Discourses : Negotiating Personal and Professional Spaces. Mahwah, N.J: Routledge.

- Anspal, T., Ä. Leijen, and E. Löfström. 2019. “Tensions and the Teacher’s Role in Student Teacher Identity Development in Primary and Subject Teacher Curricula.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 63 (5): 679–695.

- Anstead, C. J., I. F. Goodson, and J. Marshall Mangan. 2002. Subject Knowledge: Readings for the Study of School Subjects. Falmer: Routledge.

- Atkinson, D. 2012. “Contemporary Art and Art in Education: The New, Emancipation and Truth.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 31 (1): 5–18.

- Baarda, B., E. Bakker, T. Fischer, M. Julsing, M. Hulst van der, and R. Vianen van. 2017. Textbook of Methods and Techniques: Quantitative Practice Based Research. 6th ed. Groningen: Nordhoff Publishers.

- Beauchamp, C., and L. Thomas. 2009. “Understanding Teacher Identity: An Overview of Issues in the Literature and Implications for Teacher Education.” Cambridge Journal of Education 39 (2): 175–189.

- Beijaard, D., and P. C. Meijer. 2017. “Developing the Personal and Professional in Making a Teacher Identity.” In The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education 2, edited by D. Jean Clandinin and Jukka Husu, 177–192. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402042.n10.

- Beijaard, D., N. Verloop, and J. D. Vermunt. 2000. “Teachers’ Perceptions of Professional Identity: An Exploratory Study from a Personal Knowledge Perspective.” Teaching & Teacher Education 16 (7): 749–764.

- Blair, L., and S. Fitch. 2015. “Threshold Concepts in Art Education: Negotiating the Ambiguity in Pre-Service Teacher Identity Formation.” International Journal of Education Through Art 11 (1): 91–102.

- Bleazby, J. 2015. “Why Some School Subjects Have a Higher Status Than Others: The Epistemology of the Traditional Curriculum Hierarchy.” Oxford Review of Education 41 (5): 671–689.

- Chung-Parsons, R., and J. M. Bailey. 2019. “The Hierarchical (Not Fluid) Nature of Preservice Secondary Science teachers’ Perceptions of Their Science Teacher Identity.” Teaching & Teacher Education 78 (February): 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.007.

- Cohen-Evron, N. 2002. “Why Do Good Art Teachers Find It Hard to Stay in the Public School System?” Studies in Art Education 44 (1): 79–94.

- Day, C., A. Kington, G. Stobart, and P. Sammons. 2006. “The Personal and Professional Selves of Teachers: Stable and Unstable Identities.” British Educational Research Journal 32 (4): 601–616.

- Downing, D., and R. Watson. 2004. School Art: What’s in It? Exploring Visual Arts in Secondary Schools. Slough, Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Ganassali, S. 2008. “The Influence of the Design of Web Survey Questionnaires on the Quality of Responses.” Survey Research Methods 2 (1): 21–32.

- Gee, J. P. 2000. “Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education.” Review of Research in Education 25: 99–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167322.

- Geijsel, F., and F. Meijers. 2005. “Identity Learning: The Core Process of Educational Change.” Educational Studies 31 (4): 419–430.

- Goodson, I., and A. Hargreaves. 1996. Teachers’ professional lives.New prospects series; 3. London: Falmer Press.

- Haanstra, F., E. van Strien, and H. Wagenaar. 2006. Docenten en leerlingen over de lespraktijk beeldende kunst en cultuur. Amsterdam: Amsterdam hogeschool voor de kunsten.

- Hall, C., and P. Thomson. 2017. “Creativity in Teaching: What Can Teachers Learn from Artists?” Research Papers in Education 32 (1): 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1144216.

- Hatfield, C., V. Montana, and C. Deffenbaugh. 2006. “Artist/Art Educator: Making Sense of Identity Issues.” Art Education 59 (3): 42–47.

- Heffernan, K., K. Avi, P. Steve, and J. N. Kristie. 2017. “Integrating Identity Formation and Subject Matter Learning.” In At the Intersection of Selves and Subject: Exploring the Curricular Landscape of Identity, edited by E. Lyle, 53–61. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

- Heijnen, E. 2015. Remixing the Art Curriculum: How Contemporary Visual Practices Inspire Authentic Art Education. Nijmegen: Radboud University. https://hdl.handle.net/2066/143969.

- Heikonen, L., J. Pietarinen, K. Pyhalto, A. Toom, and T. Soini. 2017. “Early Career teachers’ Sense of Professional Agency in the Classroom: Associations with Turnover Intentions and Perceived Inadequacy in Teacher-Student Interaction.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45 (3): 250–266.

- Hoekstra, M. 2015. “The Problematic Nature of the Artist Teacher Concept and Implications for Pedagogical Practice.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 34 (3): 349–357.

- Hokka, P. K., K. Vahasantanen, S. Paloniemi, and A. Etelapelto. 2017. “The Recipricol Relationship Between Emotions and Agency in the Workplace.” In Agency at Work. Professional and Practice-based Learning, edited by Michael Goller and Susanna Paloniemi, 161–181. Cham: Springer.

- Hong, J., C. Day, and B. Greene. 2018. “The Construction of Early Career teachers’ Identities: Coping or Managing?” Teacher Development 22 (2): 249–266.

- Hopper, G. 2015. The Shaping of Female Ambition. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2009. “Who I Am in How I Teach is the Message: Self‐Understanding, Vulnerability and Reflection.” Teachers & Teaching 15 (2): 257–272.

- Kenny, A., and D. Morrissey. 2020. “Negotiating Teacher-Artist Identities: ‘Disturbance’ Through Partnership.” Arts Education Policy Review 122 (2): 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1744052.

- Lamote, C., and N. Engels. 2010. “The Development of Student Teachers’ Professional Identity.” European Journal of Teacher Education 33 (1): 3–18.

- Lutovac, S., and R. Kaasila. 2017. “Future Directions in Research on Mathematics-Related Teacher Identity.” International Journal of Science & Mathematics Education 16 (4): 759–776.

- Määttä, K., and S. Uusiautti. 2013. “The Framework of Teacherhood in Art Education.” World Journal of Education 3 (2): 38–49. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v3n2p38.

- Morris, J. E., and W. Imms. 2021. “‘A Validation of My Pedagogy’: How Subject Discipline Practice Supports Early Career Teachers’ Identities and Perceptions of Retention.” Teacher Development 25 (4): 465–477.

- Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. W., L. L. Hadar, K. Smith, I. Helleve, and M. Ulvik. 2017. “Teachers’ Perceived Professional Space and Their Agency.” Teaching & Teacher Education 62 (February): 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.11.005.

- Pillen, M. T. 2013. Professional Identity Tensions of Beginning Teachers. Eindhoven: Eindhoven University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR758172.

- Pillen, M., D. Beijaard, and P. den Brok. 2013. “Tensions in Beginning teachers’ Professional Identity Development, Accompanying Feelings and Coping Strategies.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (3): 240–260.

- Pillen, M., P. den Brok, and D. Beijaard. 2013. “Profiles and Change in Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity Tensions.” Teachers & Teaching 19 (6): 660–678.

- Popper-Giveon, A., and B. Shayshon. 2017. “Educator versus Subject Matter Teacher: The Conflict Between Two Sub-Identities in Becoming a Teacher.” Teachers & Teaching 23 (5): 532–548.

- Ragnarsdóttir, G. and J. Torfi Jónasson. 2020. “The Impact of the University on Upper Secondary Education Through Academic Subjects According to School Leaders’ Perceptions.” In Re-centering the Critical Potential of Nordic School Leadership Research, edited by Lejf Moos, Elisabet Nihlfors, and Jan Merok Paulsen, 191–207. Cham: Springer.

- Richards, K., R. Andrew, K. Lux Gaudreault, R. S. Jenna, and A. Mays Woods. 2018. “Physical Education teachers’ Perceptions of Perceived Mattering and Marginalization.” Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 23 (4): 445–459.

- Richardson, P. W. and H. M. G. Watt. 2016. “Factors Influencing Teaching Choice: Why Do Future Teachers Choose the Career?.” In International Handbook of Teacher Education, edited by John Loughran and Mary Lynn Hamilton, 275–304. Singapore: Springer.

- Rolstad, S., J. Adler, and A. Rydén. 2011. “Response Burden and Questionnaire Length: Is Shorter Better? A Review and Meta-Analysis.” Value in Health 14 (8): 1101–1108.

- Schaap, H., A. C. Van Der Want, H. W. Oolbekkink-Marchand, and P. C. Meijer. 2021. “Changes Over Time in the Professional Identity Tensions of Dutch Early-Career Teachers.” Teaching & Teacher Education 100 (April): 103283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103283.

- Scheib, J. W. 2006. “Policy Implications for Teacher Retention: Meeting the Needs of the Dual Identities of Arts Educators.” Arts Education Policy Review 107 (6): 5–10.

- Thornton, A. 2011. “Being an Artist Teacher: A Liberating Identity?” International Journal of Art & Design Education 30 (1): 31–36.

- Uitto, M., K. Jokikokko, and E. Estola. 2015. “Virtual Special Issue on Teachers and Emotions in Teaching and Teacher Education (TATE) in 1985–2014.” Teaching & Teacher Education 50 (August): 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.008.

- Unrath, K. A., M. A. Anderson, and M. J. Franco. 2013. “The Becoming Art Teacher: A Reconciliation of Teacher Identity and the Dance of Teaching Art.” Visual Arts Research 39 (2): 82–89.

- van der Wal, M. M., H. W. Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. Schaap, and P. C. Meijer. 2019. “Impact of Early Career Teachers’ Professional Identity Tensions.” Teaching & Teacher Education 80 (April): 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.001.

- Varelas, M., R. House, and S. Wenzel. 2005. “Beginning Teachers Immersed into Science: Scientist and Science Teacher Identities.” Science Education 89 (3): 492–516.

- Watters, J. J., and C. M. Diezmann. 2015. “Challenges Confronting Career-Changing Beginning Teachers: A Qualitative Study of Professional Scientists Becoming Science Teachers.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 26 (2): 163–192.

Appendix 1

Survey dilemma descriptions

‘To keep order in the classroom Nicole needs to be strict with her students. That is difficult, because she wants students to like her and wants to foster a good atmosphere in the classroom. Nicole wants her students to feel that she is there for them, but that does not go along with being strict’.

‘Tanek teaches the course arts and culture studies. He thinks that his students expect him to have more knowledge about the arts than he actually has. He doesn’t know what to do about that’.

‘Julia is very concerned about her students’ well-being and their learning. She has a hard time accepting that she is not capable of helping her students in the way that she should to fulfil their needs in both’.

‘Karin finds that she is very dependent on the mentor she has been assigned to. He forces her to teach in a way that does not square with her own way of teaching. She likes to experiment and wants another way of dealing with her students than her mentor does. At the same time, she has to listen to her mentor, because she is still in her probationary period’.

‘Susan wants to perform her teaching job well, but she also wants to have time for other things outside work. She does not know how to divide her time properly’.

’Anne feels comfortable in the arts section, but not outside of it. She appreciates that her colleagues at school are nice to her but deep down she doesn’t think she could ever be a teacher like many of the teachers that work at her school’.

‘Dalila finds it hard to assess students on the basis of their performance alone. She also wants to consider the person as a whole. Dalila finds it difficult to focus on outputs because there are things that she finds equally important, such as the well-being of students’.

‘Because Maria feels like she still has much to learn, she has difficultly acting like a teacher and being treated like a teacher by students and colleagues. Sylvia feels too young to be a teacher. She cannot take the responsibilities that come along with the profession’.

‘Simon just started at his school. He feels he is treated too much like a student teacher when he should be regarded as an independent teacher. Simon isn’t sure what he should do. He wants to stand up for himself in order to be treated seriously. At the same time, he does not want to be too intrusive, because he is new in the section’.

’Michelle started with strong beliefs about what art can contribute to education but can’t seem to convince colleagues, or students, to move out of their comfort zone. Michelle feels disappointed and wonders just what the arts mean to the school’.

‘Now that Ben has started to work as a teacher he is wondering whether he can actually be a good teacher. He experiences problems because he does not have enough time to accomplish all his tasks well’.

‘Sarah finds that she did not learn the things she should have learned during teacher education to be able to function well in a secondary school’.

’Linda finds end of term meetings frustrating. She feels that the art subjects only get discussed when a student is in danger of failing or there are problems with the schedules of the exam candidates. She doesn’t think colleagues take the art subjects seriously’.

‘One of her students took Aziza into his confidence about a personal problem. She is in conflict with herself. She wants to protect the student’s privacy, but at the same time she is afraid that the student is a danger to themselves or others’.