ABSTRACT

Using the context of Teaching as Inquiry (TAI), this study responds to calls for in-depth qualitative research documenting opportunities that have the potential to build Teacher Self Efficacy. Drawing on 4 data sets generated by 28 student teachers as they undertook a TAI project during their final practicum, we illustrate how TAI experiences fostered competence and confidence through knowledge and skill development. We also highlight the impact outcome expectancies had on student teachers’ behaviour including their expectations of students from diverse backgrounds. As well as building persistence and resilience we show how the cyclic nature of the TAI process developed student teachers’ understanding of task magnitude with reference to their inquiry goals and teaching in general. Finally, we argue that self-efficacy needs to be promoted as a core rationale for TAI if its full potential in developing self-efficacious student teachers is to be realised.

Introduction

Ensuring that students have access to an education that is inclusive and equitable is an ongoing challenge internationally (UNESCO Citation2017). Differential achievement and outcomes between student cohorts according to ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, and linguistic background remains an enduring issue (Ainscow Citation2020). In New Zealand, international comparisons of educational achievement show that students who are predominantly European and Asian are over-represented in high-achieving groups. Conversely, Māori and Pasifika students, and those from lower socio-economic communities are over-represented in low-achieving groups. These inequitable results expose New Zealand as having one of the largest gaps between high and low achieving students in the OECD (Bolton Citation2017; OECD Citation2016).

Given that teachers are the most important school influence on student learning (Hattie Citation2008), it is critical that teachers have high levels of teacher self- efficacy (TSE) if the divide between high and low achievers is to be reduced. Teachers must believe they have the knowledge, skill and dispositional qualities necessary to ensure learning opportunities result in successful outcomes for all the children they teach, even those who may be unmotivated or disengaged.

Teacher self-efficacy

TSE refers to the generalised expectancy a teacher has in regard to their ability to influence students’ learning in a positive manner as well as beliefs about their ability to perform the professional tasks that constitute teaching. Given the magnitude and complexity of teaching, TSE may not necessarily be uniform across the multitude of tasks a teacher is required to perform or the different subject matter they may be required to teach (Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy Citation2001). The knowledge and skills a teacher brings to teaching will be influencing factors when making efficacy judgements. Also, TSE may be influenced by student demographic factors such as age and ethnicity (Poulou Citation2007).

Although a matter of perception, there is clear evidence that TSE has an influence on practice (Poulou Citation2007). TSE affects the magnitude of the goals set and the amount of effort expended to reach goals. It influences degrees of persistence and resiliency and whether coping behaviours are initiated in the face of setbacks (Kavanoz, Yuksel, and Ozcan Citation2015). Typically, teachers with high degrees of TSE are more willing and able to develop positive learning relationships with students and are able to deal effectively with challenging student behaviour (Zee and Koomen Citation2016).

Early experiences are important to the development of TSE as this is the time when teachers’ beliefs are most malleable and open to change, either positively or negatively (Pajares Citation1992). Therefore, Initial Teacher Education (ITE) is an important space within which to foster TSE beliefs (Yough Citation2019). Those developing programmes must take cognisance of the four sources of efficacy belief: mastery and vicarious experience, social persuasion, and physiological and emotional states. Attention should be paid to the provision of substantial opportunities to build student teachers’ (ST) robust efficacy beliefs through the advancement of teaching competence and confidence. Given that mastery experiences are considered the most powerful source of efficacy belief, it must be recognised that practicum experiences will play a significant role in their formulation (Poulou Citation2007). Vicarious experiences in the form of social models, are also considered an influential way in which individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to master comparable activities can be strengthened. Therefore STs need substantive opportunities to observe credible role models working successfully with diverse cohorts of students (Siwatu Citation2011). While social persuasion is a less powerful source of influence, it has potency when combined with successful mastery experiences. To capitalise on this source STs should be encouraged to seek, listen to and act on feedback from their peers and colleagues as well as the students they teach. Finally, given that people rely on ‘their physiological and emotional states in judging their capabilities’ (Bandura Citation1995, 4) STs need to understand that teaching is a complex activity and successful mastery is not easily achieved. An initial lack of success should not be seen as reason to doubt one’s competence. Rather difficulties encountered should be viewed as valuable learning opportunities that can be overcome with sustained and persistent effort.

Whilst there is a body of research that documents the TSE of both STs and experienced teachers these studies have been mostly quantitative, utilising existing SE scales (Ma and Cavanagh Citation2018). While these scales provide informative numerical and statistical data, they fail to provide a rich picture of what teachers’ responses may mean or where support is needed (George, Richardson, and Watt Citation2018). There is a need to move beyond the use of surveys and SE scales and to adopt qualitative methods that will help ‘develop a better understanding of the contextual pathways and experiences that promote teacher efficacy’ (Blonder, Benny, and Jones Citation2014, 11). Despite these calls for an alternative methodological focus, studies investigating TSE through the use of SE scales are still prominent in the literature. In this article we respond to calls for research that provides rich detail in relation to the opportunities that have the potential to influence STs’ TSE (Usher and Chen Citation2017) as they learn to teach (Pendergast, Garvis, and Keogh Citation2011).

The context for the study

In New Zealand, ITE has become a major policy lever in the drive to improve teacher quality. Aimed at improving the quality of graduating teachers’ practice in order to raise the achievement of a diverse range of learners the Ministry of Education has encouraged providers to develop new approaches to ITE programmes ensuring they are both intellectually demanding and practice-focused.

The Master of Teaching (Primary) (MTchg) was developed as an intensive, intellectually demanding master’s degree. The programme aimed to graduate beginning teachers who were efficacious, resilient, self-motivated and self-regulating professionals who could work collaboratively with students, colleagues, and parents (MTchg (Primary) Programme Handbook, 2019–2020). As such STs were encouraged to adopt an inquiry stance (Cochran-Smith and Lytle Citation2009), that is a habit of mind, whereby they were expected to continually reflect on how their practice impacted on all students’ learning. They were also asked to consider broader questions about how inequitable educational resources, processes, and practices influence diverse student opportunities and outcomes. Addressing such questions were seen as important given that ITE students in New Zealand tend to be white and come from higher socio-economic communities and would possibly have limited knowledge and experience of working with students from diverse backgrounds.

Hence the MTchg programme aimed to develop graduates who would feel confident and competent to work effectively with a diverse range of learners and just as importantly have the determination to meet and overcome any challenges they would face. Throughout the programme a strong emphasis was placed on developing STs’ sense of self-efficacy, both as learners and teachers. It was assumed that building robust efficacy beliefs would enable STs to cope with the magnitude and complexity of learning and learning to teach; develop resilience and persistence when faced with setbacks and self-doubt; and take responsibility for their successes and failures. Additionally, an awareness of personal efficacy beliefs and development would enable STs to provide support for learners who were socially, culturally and linguistically diverse, and utilise practices that promote engagement and learning which in turn would build learner self-efficacy.

A key feature of the degree was a strong and sustained practice-focus, involving more time on practicum, specifically in schools with diverse student populations in terms of ethnicity, culture, language, and socio-economic status. To meet the strong practice requirement, STs were required over time to work intensively in two different host schools. The first placement (July-December) was in a high decile, culturally diverse school where the STs worked two days a week, returning to the university campus for the remaining three days. This placement culminated in a three-week full-time practicum experience. For their second placement (February-June), STs were intentionally placed in a low decile school with a high proportion of Maori, Pasifika and second language learners, also working in this host school two days a week. This placement was bounded by two full-time practicum experiences: three weeks at the beginning of the school year and a summative six week practicum towards the end of their programme. Across both placements during their two-days in schools, STs were expected to take on increasingly demanding teaching tasks. In the final six-week practicum STs were required to take full responsibility for the class for three weeks. They also undertook as part of course work, a Teaching as Inquiry (TAI) project aimed at developing their understanding of and practice in working with students from diverse backgrounds.

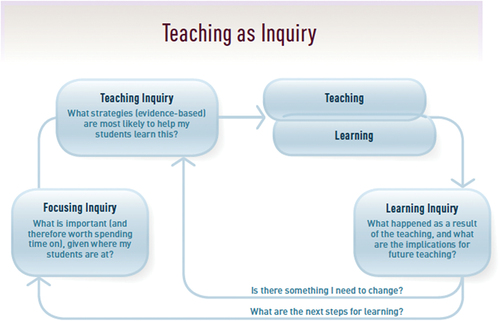

Utilising a cyclical inquiry process to examine the impact of teaching on student learning, TAI has been acknowledged as one of the most powerful sources of teacher professional learning. Through the systematic collection, analysis and use of data, TAI has been shown to support teacher exploration, experimentation, reflection and evaluation (Timperley, Kaser, and Halbert Citation2014). In New Zealand it has been argued that the TAI process is key to teachers achieving success for all learners (MoE, Citation2020). In the final semester of their programme, STs undertook a practitioner inquiry course taught prior to and alongside their final six-week practicum. The course required STs to identify and investigate a problem of practice during their practicum. To this end STs were taught how to use the TAI framework (see ) to undertake a systematic inquiry into how their teaching impacted on diverse students’ learning.

Figure 1. Teaching as inquiry.

STs were expected to develop a research question related to their selected problem of practice in the area of Literacy or Mathematics (drawing on previous courses in these domains, and school placements), and to use the TAI framework to carry out three cycles of inquiry into their practice. Each ST created an Inquiry Plan and were given lecturer feedback and sign-off on their plans prior to starting their practicum. The first of three TAI cycles were carried out during their initial ten days in the classroom. Two weeks into the practicum, during an on-campus session STs worked collaboratively with peers to analyse data from this cycle and identify the focus and question for Cycle Two. The STs wrote up their second cycle process and outcomes in a Milestone (progress) Report, which also identified their intended implementation of Cycle Three. To accommodate classroom and practicum requirements, the STs chose the most suitable time to undertake their second and third cycles over their final four weeks of practicum. Throughout the inquiry process STs worked with a critical friend from their cohort. An understanding of the role of critical friend was developed by drawing on Costa and Kallick’s (Citation1993) notion of working with a trusted person who provides assistance by asking provocative questions, offering another lens to view data, making suggestions, and giving constructive critique. In addition, as part of each cycle of inquiry, Associate teacher and Adjunct (Visiting) lecturer feedback, reflections on their own teaching, learners’ observations, and evidence of students’ learning were utilised to identify the focus for ensuing cycles. At completion of the project STs presented their inquiry findings via a poster, to peers, programme staff, and school colleagues.

The research methodology

An interpretative, qualitative approach was utilised for this study. Specifically we sought to:

Investigate how engagement in a TAI project provided opportunities and experiences that had the potential to support STs’ efficacy in relation to working with diverse learners within a bounded context. The research did not aim to measure changes in student TSE. Rather it sought to provide insights into the nature of the experiences students saw as influential in regard to building their confidence and competence when working with a diverse range of learners, often from very different backgrounds and experiences to their own;

Determine what sustained/motivated STs as they worked through their cycles of inquiry.

To address the two research aims four datasets were utilised. Generated throughout the inquiry these were each ST’s Inquiry Plan [IP] (2–3 pages); Milestone Report [MR] (2–3 pages); Critical Friend Feedback and the final Inquiry Report (3000 words) presented in the form of a Poster [P]. Ethics approval to utilise these data was gained from the University’s Human Participants Ethics Committee (Ref #012500) with all STs in the cohort providing written consent for their inquiries to be used for research purposes, once they had graduated from the programme. The 28 participants in the current study comprised the total cohort of students in the year long programme. Twenty-seven STs were female and 1 was male with the majority identifying as European. Two identified as Pasifika and seven were of Asian and/or Middle Eastern heritage.

Bandura’s (Citation1977) theory of SE was utilised as a deductive device through which data were analysed. Given the nature of the STs’ individual inquiries it was assumed that core concepts associated with TSE would appear in the data: for example, what was working well when teaching diverse learners (mastery), what the feedback they received was telling STs (social persuasion), and how STs were feeling as they worked with their learners (emotional states). During the analysis process techniques associated with open, axial and selective coding (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) were also used. As such Bandura’s framework provided some of the emergent categories used during open coding. Concepts such as confidence (high-low), knowledge (strong-weak); emotions, learner engagement, success, challenges became categories which were used as substantive levers (Neuman, Citation2003) to interrogate the data. A second level of coding established relationships among and between open codes which created axial codes. These codes were created with reference to both the literature and terms used by the STs eg: experience; mastery; valued outcome; emotive states; magnitude of task. Throughout this process the authors checked randomly selected samples of open and axial coding, along with data and codes identified as puzzling. These checks strengthened the dependability of the analysis process and the trustworthiness of our interpretations. The axial codes were then cross-cut and linked at a descriptive and conceptual level to identify central patterns and relationships. Finally, selective codes were formed in which interrelationships between themes and sub-themes were identified. To enhance the trustworthiness of the research and to counteract criticisms that teacher education research does not sufficiently consider ST perspectives when examining ITE programmes (Korthagen, Loughran, and Russell Citation2006) extensive use of STs’ voices is made in the presentation of the findings.

Findings

STs were required to carry out their TAI projects in one of the following areas: Reading, Writing, Oral Language or Mathematics. Two key themes, each with sub-themes, emerged from the data and are reported below. The quotations in each of these themes exemplify thoughts and feelings expressed by a majority and in some instances all of the STs. Moreover, a range of voices (21 of the 28 STs) have been included.

As noted earlier, all were placed for their second teaching placement in schools that had a high proportion of Maori, Pasifika and second language learners:

My [placement] is in a class [that] is culturally diverse with 14 students having additional ESOL support. Students come from a range of ethnic backgrounds including Asian, Pacifica, European, NZ European and Maori. (Deana, P)

During the two days a week spent in their host schools STs had taught a number of group and class based literacy and maths lessons with many making mention of the low levels of achievement recorded for their learners in these areas – a situation they considered unacceptable and inequitable. The need to challenge this state of affairs served as an impetus for undertaking the inquiry and shaped the focus:

Many of the struggling learners were ESOL-Pasifika students. To challenge the classroom practices that reproduce inequity [for these learners] I purposefully chose peer-assessment … for its ability to provide an additional support system and source of feedback for these students (Teresa, P);

In order to challenge inequity and pave the way for beneficial lessons, all students need to have equitable access to participation. Using Talk Moves to create an environment in which that happens is an effective place to start. [my inquiry] (Nerissa, P)

Theme 1: pre inquiry – identifying the need to build competence and confidence

Drawing on experience

When making decisions about aspects of teaching practice that would form the focus for their inquiries, all of the STs referred to prior teaching experiences, drawing on these to identify authentic areas for improvement:

[In] my previous lessons I have not scaffolded or modelled the writing process well enough and have not provided the students with the language or strategies they needed to succeed … this led to my decision to focus on improving my practice in modelling (Rita, IP).

STs recognised the nature and scope of their prior teaching was somewhat limited thus contributing to gaps in practice:

Due to my lack of experience … [I do not know] how to support these reluctant writers and which strategies to implement. (Ferne, IP)

Ferne’s limited experience in teaching writing and supporting diffident writers provided her with the impetus for inquiring into how she could use selected strategies to improve learner engagement. Bonnie echoed Ferne’s sentiments, acknowledging how a lack of experience and ‘insufficient knowledge of strategies’ in promoting meaningful and productive peer-to-peer discussion in the context of mathematical problem-solving made it ‘hard for me to support my students’ (IP). As a result, she decided to inquire into the use of think-pair-share to see how it impacted on learners’ participation in problem-solving discussions. Debbie also selected the learning area of mathematics for inquiry, noting she had ‘not experienced [until this placement], learning or teaching mathematics in classrooms that encourages … learner discussion as DMIC] maths does’ (IP). Her lack of familiarity with DIMC maths meant she ‘did not have [knowledge or experience of] the … strategies to facilitate these lessons successfully’ (IP). She believed directing her inquiry to the use of DMIC strategies would further her teaching competence in this area.

As the STs reflected on past classroom experiences, they considered how learners responded to their lessons. Tessa thought her learners’ reliance on the teacher when making decisions about the quality of their writing was an outcome of the way she carried out her role as teacher:

Reflecting on my practice [teaching writing] highlighted that I had reinforced students’ over-reliance on my judgement through teacher-centred and transmission-based practices which positioned myself as the sole ‘expert’ …(P).

This led to her investigating different ways of getting learners to use success criteria to help them make informed judgements about the quality of a piece of work. Bonnie also drew on her observations of learners, remarking that ‘students are not talking to their maths buddies or contributing to larger group mathematical discussion’ (P). This strengthened her decision to inquire into ways in which she might increase learner participation in problem-solving discussions.

Other sources of evidence that informed STs’ foci for inquiry included observations and feedback from Associate Teachers [ATs] with all making mention of the role played by their ATs:

… [through my] AT’s observations, I discovered that there was an issue when it came to participation of all students and the lack of student led mathematical discussion (Nerissa, P);

and some also referring to feedback from the Adjunct Lecturer who had watched them teaching during their first school placement:

I was not providing enough opportunities for children to talk and share ideas … my lessons … consisted mainly of teacher talk rather than dialogic engagement …. (Sandie, IP)

STs thus reflected on past teaching experiences, drew on learners’ responses and considered feedback from colleagues to identify aspects of practice not yet mastered. Limited mastery was attributed to having had few teaching opportunities and/or knowledge of strategies appropriate to the learning area – it was not attributed to any ‘deficit’ on the behalf of their learners. STs’ discourse suggested that through further teaching experience as part of the targeted TAI process, they could and would improve their teaching competence and confidence.

Affective states

All STs admitted to gaps in practice. These admissions did not necessarily result in adverse or debilitating emotions, rather their affective states were tentative and somewhat circumspect. Gemma for instance ‘felt uncomfortable … because of my own lack of knowledge [about how to engage learners in the writing process]’ (P). Others expressed uncertainty and doubt about the effectiveness of their current practice:

I am unsure if my current practice is assisting or is a hindrance in developing the students’ comprehension of the text … I am unsure if I am currently using questioning strategies effectively … (Laura IP);

and professed to having low self-confidence when it came to implementing specialised strategies. Tanya thought she had ‘limited … confidence … to address [learners’] needs … ’ (P) while Bonnie admitted to lacking confidence when working with mixed-ability groups of learners in mathematics, a feeling that ‘has made it hard for me to support my students [in their mathematical discussions and problem-solving activities]’ (IP). Similarly Nerissa commented on her ‘low self-efficacy in regard to teaching maths’ (P) explaining she was ‘very nervous about asking questions or building on students’ questions in fear of making a mistake’ (P).

Apprehension, coupled with low levels of confidence and doubts about one’s teaching competence, did not deter STs from accepting the challenge of addressing gaps in practice in their respective inquiries. There was an underlying belief the TAI process would ‘develop [my] confidence and practice’ (Toni, P). STs believed the targeted teaching experiences underpinning their inquiries would afford a platform on which to build knowledge of and competence in selected teaching strategies, and as a corollary, they expected cognitive and motivational benefits for their learners – as noted by Nora, ‘improving [one’s] practice is oriented to improving outcomes for students … ’ (P).

Valued outcomes for learners

Enhanced outcomes for their diverse learners was the expected result of improvements in STs’ teaching competence. Tegan and Nerissa made reference to the link between their ability to stimulate discussion between learners, and enriched cognitive gains in terms of mathematical understandings:

… group mathematical discourse is supported in the literature as a means to improve student understanding (Tegan, P);

… increase students’ mathematical understanding … [there are] links between [student led] discussion and higher levels of understanding. (Nerissa, P)

Natasha similarly highlighted how the understandings of struggling readers would be enhanced through her ability to ask salient questions, a connection that underscored the importance of mastering this aspect of practice:

… effective teachers who use questioning strategies unlock the understanding of a student who is struggling with an aspect of their reading, thus emphasising the urgency for me to further develop my questioning abilities during guided reading sessions … .

STs also recognised value in addressing motivational outcomes in particular increasing learner participation and engagement during instructional sessions:

It is important for me to be able to motivate these learners to become more engaged in maths because a lack of engagement is one of the first signs that a student is not going to experience success with their learning and may be a strong indication that something in the way I am teaching is not working for my students (Lena, P);

with some like Nancy drawing links between heightened learner involvement and levels of achievement:

… strong link between engagement and achievement … [I want to] increase levels of engagement (IP);

and others like Ferne making connections between engagement and longer-term academic and societal outcomes:

I am concerned that if these students continue to disengage, they will struggle throughout their schooling as writing is a crucial skill … . Additionally, to be successful participants in society students must be able to communicate their ideas in writing (IP)

STs believed that strengthening engagement would also further learner self-regulation, independence, confidence and more specifically, self-efficacy:

… engage learners and build their confidence to support independence in reading (Farah, P);

… engagement … in [class reading of] Big Books will spur students to seek out texts to read for themselves, thus helping them become independent readers who are self-efficacious and can manage themselves as learners. (Ivan, P)

At no stage did STs blame their learners or factors outside their sphere of influence for perceived lack of understanding or low levels of learner engagement and motivation. There was a very strong belief across the cohort that improvements in one’s teaching practice would further students’ learning and enhance levels of achievement.

Theme 2: cycles 1, 2 and 3 - building competence and confidence

Each TAI cycle provided fresh opportunities for STs to develop their teaching knowledge, proficiency and confidence, and enhance learners’ motivation and learning. As they reflected on lessons, all of the STs considered how effective they had been in attaining their goal(s), identifying successes, gaps in practice and ‘where to next’ for ensuing cycles.

Evidence of competence

Two key sources of data were drawn upon by STs when considering the effectiveness of their teaching. The first was evidence from recordings of lessons. Having an audio or video recording of lessons arguably served as an asynchronous mastery experience with STs re-living their teaching practice. Sandie’s experience was typical of those in the cohort. Her Cycle 1 goal had been to ‘use [a] language experience that connected to children’s interests to encourage children to talk’ (P). After watching and reflecting on the video recording of this lesson, Sandie concluded that although the language experience generated interest from her learners, ‘my questioning was very closed … I was following a very structured teacher-to-student type sharing’ (P). This indicated an area to address in Cycle 2, where her revised goal was to ‘use a range of prompting techniques and variety of questioning to support children’s talk during storytelling in small groups’ (P).

The second source of evidence was verbal and/or written feedback from external sources. Virtually all of the STs made reference to their ATs having observed their lessons and providing feedback on the target strategy. For some this information intimated areas in need of further attention:

Feedback from my associate teacher revealed I did not use student voice, explanations or discussions enough and this was reflected at the end of the lesson when students could not talk about what they learned (Tegan, P);

for others it highlighted aspects of successful practice:

My AT reported [after cycle three] that my collaborative approach to leading and teaching these rhymes and songs was a highly effective method to encourage oral language participation …(Tanya, P).

STs also sought reactions to lessons from a peer who had been assigned as their critical friend – having a critical friend was a requirement of the task so it is not surprising that all STs identified their critical friend as a source of feedback. Critical friends who were at the same school observed each other’s lessons in real time and then discussed the lesson, while those placed at different schools were given access to audio and video recordings, using these as the basis for discussion and feedback. Debbie’s critical friend Laura noted after Cycle 1 that Debbie’s attention when working with a mixed ability maths group ‘was focused on one student who appeared to be getting it which reduced my attention to other students’, a practice Debbie was unaware of. As a result of this feedback, one of Debbie’s goals for Cycle 2 was to ‘ensure that [equal] attention is given to all students’, a strategy she subsequently executed successfully. As part of this reciprocal process, Debbie presented evidence after Laura’s Cycle 1 lesson that showed Learner A only ‘participated once with a simple yes/no response to a memory recall question’ (Laura, MR) while all other learners in the group answered recall and inferential questions and offered ideas on at least four, and some as many as eight occasions. Debbie and Laura then came up with two strategies for Laura to utilise in Cycle 2:

… we both agreed that think, pair and share would be an appropriate strategy to implement for cycle 2 to see if this increases X’s participation during guided reading. … [Debbie] suggested that it would be helpful to select a text which would be of interest to X, to see if this also leads to increased student engagement …. (Laura, P)

STs also considered learners’ responses during lessons to ascertain the effectiveness of their practice. Zara for example interviewed two children after her Cycle 1 lesson regarding her use of think-pair-share:

One student said sharing with their peers helped him to have an idea to write about (MR);

and Nora considered learners’ responses from her Cycle 2 writing lesson when determining how successful she had been in implementing revoicing:

Twice during the lesson, students remarked ‘hey, that was my idea’ when another student shared an idea or comment back to the whole group. This suggests that students are listening to each other’s ideas, and taking on the ideas and language as they repeat or revoice this back to the whole group. (MR)

Collectively, evidence from audio and/or video recordings, and feedback from Associate Teachers, critical friends and learners enabled STs to recognise successes, gaps in practice and where to next. Evidence from these sources encouraged STs to persevere in their endeavours, helping to build confidence and competence:

The insights and valuable conversations I had with my AT and critical friend supported me in developing my next steps and improving my practice. Often talking through what happened with others gave me a new perspective. (Tegan, P)

Outcomes for STs

A key outcome for all STs was the incremental refinement and successful execution of selected teaching strategies. Over the course of the three cycles varying degrees of mastery were apparent in for example, the use of Think, Pair, Share during writing conferences and questioning to facilitate mathematical problem solving:

Student to student interaction was facilitated and encouraged 15 times throughout the conferencing session [through Think, Pair, Share]. … I [now] need to support students to independently manage this process. (Ferne, P);

31 questions were asked … of these: 20 questions were closed, 7 were open and began with ‘how’, and 4 open questions were used that began with ‘why’. Closed questions were used to break down the … problem and scaffold learning. This resulted in my task explanations being clearer. Students were able to access learning and therefore participate. ‘how’ questions were used with all students. They kept students on task and extended their thinking. ‘why’ questions were used to check understanding. I noticed that I only asked these questions to early stage six learners. (Bonnie, P)

A further outcome was the determination and perseverance displayed by STs when evidence showed a strategy had not worked, or had been partially successful. None of the STs gave up – they persisted in their endeavours, identifying different or more nuanced approaches to try in subsequent lessons:

All students could apply the success criteria to their buddy’s work, however only half could use this information to provide specific written feedback to their buddy. When questioned, students demonstrated that they could verbally provide more elaborate and specific feedback. Oral feedback in a conferencing scenario may be a more equitable form of feedback for all students’ needs and abilities, as it would also provide the feedback recipient with the opportunity to seek clarification. Teacher modelling needs to explicitly scaffold the language used to provide specific and kind feedback, and how to request further clarification or explanation of feedback (Teresa, P)

Through TAI, STs gained insights into their emotional states and how to manage these when lessons did not go to plan. As alluded to by Gemma, teachers need to be resilient – teaching and the improvement of one’s practice is not for the faint-hearted:

There were many times during this teacher inquiry where it felt like everything I did was going wrong, but critical friends were able to stop and say ‘but you did this … ’. … [TAI] requires being comfortable with failure. Expectations are not always met as cycles can be filled with successes but also many failures. Sometimes I felt like I needed to scream, cry and quit, but teaching is reflecting on these moments, learning from them, and considering where to go next …. (Gemma, P)

On a wider front, immersion in TAI resulted in all of the STs gaining a deeper appreciation and understanding of the complexities and challenges involved in the work of teaching and the improvement of one’s practice:

Teaching is very multi-faceted … [I have] started to understand and see the unpredictability of teaching … (Fiona, P);

… the inquiry taught me just how challenging it is to teach mathematics in mixed ability grouping … I now understand the high level of pedagogical and curriculum knowledge that is necessary for me to be able to teach effectively in this way (Bonnie, P);

with Toni acknowledging that learning to teach ‘is a never-ending process’ (P).

Discussion

In the current study STs had been intentionally placed in schools with high proportions of Maori, Pasifika and second language learners. According to achievement data these students would have generally been achieving at lower levels in Mathematics and Literacy comparative to national norms (Ministry of Education Citation2018). It was within this context of working in a school and classroom context with learners who may have been performing below expected achievement levels and frequently of different ethnicities to themselves that STs undertook their TAI projects.

Comprised of three dimensions (strength, magnitude and generality), TSE is not a stable trait. For example within the context of ITE the dimension of magnitude can pose a potential threat to TSE. The expectation that over time STs will master more complex and demanding teaching tasks and activities increases the magnitude of the task. As a consequence of these increased expectations, efficacy can strengthen or weaken. Unsurprisingly the most dramatic changes to efficacy beliefs occurs during practicum placements as greater expectations are put on student teachers (Pendergast, Garvis, and Keogh Citation2011) with a decline in TSE often occurring (Ma and Cavanagh Citation2018). This was not the case in the current study. Drawing strength from the various sources of evidence that engagement in TAI provided, STs were able to make accurate appraisals of their current levels of competence and plan ways forward to continue to develop competency. As a result STs mastered an increasingly complex set of teaching skills. In turn, a heightened sense of competence in a specific domain gave STs confidence in their ability to work with and engage learners from a diverse range of backgrounds. This growing sense of confidence and competence seemingly sustained STs through their ongoing cycles of inquiry. Even when faced with unexpected challenges or difficulties the belief they were making progress and improving their teaching in a specified area proved heartening.

Of the four sources of influence, three seemed to be particularly influential as STs undertook in their inquiry projects: mastery; social persuasion and managing physiological and emotional states. Information gleaned from these sources not only supported the development of positive efficacy beliefs but also supported STs through their cycles of inquiry. In the current study STs identified a focus for their inquiry based on information gleaned from previous teaching placements. In doing so they recognised the need to build competence in a specific area. While they approached the inquiry with some trepidation, the cyclic nature of TAI provided them with a number of mastery experiences that built both knowledge and skill. At times when they were faced with performance failures or partial success, these let downs were neither frequent nor strong enough to have a major impact on confidence. Although an initial or temporary lack of success may have produced a level of self-doubt, this was not paralysing. Seemingly STs considered difficulties encountered as valuable learning opportunities. Viewing these difficulties in such a manner provided the impetus and motivation for STs to continue to strive to meet their goals. By overcoming self-doubt and recognising and accepting that sustained and persistent effort was needed to succeed it can be argued that STs managed their physiological and emotional states in a positive manner.

Social persuasion when coupled with mastery experiences is also effective in developing TSE (Bandura Citation1977). As Bacon (Citation2020) noted, receiving authentic and genuine feedback from significant others helps to develop feelings of accomplishment. In the current study, as an integral part of the inquiry process, STs were encouraged to seek, listen to and act on feedback from a range of credible others. Critical friends, associate teachers, adjunct lecturers and the learners they taught all provided this feedback. It appeared the nature and scope of the persuasion or feedback offered by this diverse range of significant others became a strong source of information. Feedback offered helped STs to make a balanced and informed appraisal of their current capabilities and helped them consider alternative perspectives. The provision of constructive suggestions proved helpful in regard to where to next enabled STs to cope with the demands and challenges associated with their individual inquiries. It would seem that the constructive and insightful feedback generated by credible others as well as the responses and reactions from learners became both a source of encouragement and a source of support which enabled STs to make progress towards achieving their inquiry goals.

Arguably, STs engagement in their TAI inquiries engendered a strong efficacy expectation – they expected that with experience and practice they would master the skills and strategies identified within their inquiries. Closely associated with an efficacy expectation is an individual’s outcome expectancy, that is their expectation of the perceived consequences of engaging in a particular behaviour (Bandura Citation1977). Findings from the current study would suggest TAI provided an authentic context that influenced and reinforced STs’ outcome expectancies – those they held for themselves and those they held for their students. STs selected their inquiry focus informed by the belief that the target area was of importance to learners’ engagement and learning. Acknowledging they lacked knowledge and skill in an area, STs saw the inquiry as an opportunity to build competency and in doing so support student learning. Working with their learners in a given domain STs did not seem daunted by the fact that some of the these learners may have experienced difficulties in the past. It would therefore appear that implicit in their actions throughout the inquiry was a strong outcome expectancy for their learners.

Coming from backgrounds far different from the diverse learners they teach can have a negative effect on TSE beliefs and outcome expectations (Morris Citation2017). Limited experience of working in diverse communities may lead STs to take a deficit view of learners who do not share their cultural or linguistic backgrounds. This may influence the nature and type of learning experiences provided, resulting in reduced learner engagement and lower levels of achievement (Rubie-Davies, Webber, and Turner Citation2018). In the current study this was not the case. Prolonged practicum placements in a school along with participation in an inquiry project focused on meeting the needs, interests, and abilities of their learners was seen to accrue benefits to both the STs and the children in their class. In contrast to research that has highlighted teachers’ lack of confidence and competence when working with learners from cultural and linguistic backgrounds dissimilar to their own (Yough Citation2019), this disparity did not appear to be influential in the current study. The cyclic nature of the inquiry facilitated the improvement process as STs mastered various skills and tasks, becoming an ongoing source of motivation. The collection and analysis of a range of evidence throughout their inquiry cycles provided STs with tangible proof that their teaching was having a beneficial effect on their learners. Noticing a range of positive outcomes accruing to their learners strengthened their outcome expectancy – they could see their hard work and commitment to their learners was paying dividends – both for them and their learners. This strong outcome expectancy in regard to the perceived benefits to their students and their learning was a further motivational source. It enabled STs to persevere and persist throughout the duration of their inquiries.

Conclusion

Whilst TSE may be seen as a generalised expectancy, the critical role of classroom and school context must also be taken into account when aiming to enhance TSE (Lazarides and Warner Citation2020; Thommen et al. Citation2022). Class composition such as student age, ethnicity, gender, language abilities and socio-economic status can influence teacher expectations for students’ motivation and engagement (Morris Citation2017) and influence their efficacy beliefs. By focussing on STs experiences of undertaking a Teaching as Inquiry (TAI) project, the current study has illustrated the sources of influence that not only contributed to the development of STs efficacy beliefs but also sustained them through their inquiries. Additionally, drawing attention to the school and classroom context has provided positive evidence of how TAI can support STs efficacy and outcome expectancies in relation to working with diverse learners.

To date much has been written about the benefits of TAI. Promulgated as an iterative, reflective, evidence-based, transformative process, it has been argued that when undertaken in a systematic manner, TAI has the potential to improve teacher practice, and in turn enhance student learning and achievement (Timperley, Kaser, and Halbert Citation2014). However, missing from the literature is reference to the ways in which TAI can be used to support and further TSE – it appears this pivotal benefit of TAI has not been explicitly recognised or disseminated. In this paper, through documenting STs’ experiences when undertaking a TAI project, we have drawn attention to how such experiences can have an effect on TSE, and highlighted the impact outcome expectancies have on behaviour. Given the connection between teaching competence and confidence, and children’s learning (Zee and Koomen Citation2016), the intentional integration of TAI into teacher education programmes is critical. Arguably, STs engagement in a TAI project afforded them authentic experiences that developed both their teaching competence and confidence in working with diverse learners. Through their ongoing endeavours they began to develop the requisite knowledge and skill necessary to perform increasingly complex tasks and successfully attain goals. Further the cyclic nature of their inquiries presented STs with experiences that built their persistence and resilience, qualities which are critical given that complex performances such as learning to teach are never mastered at first attempts (Bandura Citation1977). Also successive engagement in the three inquiry cycles appeared to provide STs with valuable insights into the magnitude of the task as it pertained to their inquiry goal and teaching in general. Finally, successful completion of their TAI projects built STs’ understanding of the complex and demanding nature of teaching. Significantly, if the full potential of TAI in developing self-efficacious student teachers is to be realised, educators need to recognise and overtly promote self-efficacy as a core rationale for TAI. It is insufficient to have development of agentic, self-efficacious STs as a goal of Teacher Education without educators intentionally providing productive opportunities for STs to develop the full range of attendant knowledge and skills during their Teacher Education programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helen Dixon

Helen Dixon is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education and Social Work. She has an interest in teacher professional learning and how teachers can be supported to improve practice. She also has a particular interest in teacher beliefs, including their efficacy beliefs, and how these influence practice.

Eleanor Hawe

Eleanor Hawe is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education and Social Work. Her research focuses in the main on assessment for learning and self-regulated learning - more specifically, goal setting, feedback (including peer feedback), the use of exemplars and the development of students’ evaluative and productive expertise across a range of educational contexts and teaching subjects.

Lexie Grudnoff

Lexie Grudnoff is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education and Social Work. Her research interests are broadly related to teacher professional learning and development, particularly in terms of enacting practice that promotes more equitable learner outcomes and opportunities.

References

- Ainscow, M. 2020. “Promoting Inclusion and Equity in Education: Lessons from International Experiences.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 6 (1): 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587.

- Bacon, W. J. 2020. “New Teacher Induction: Improving Teacher Self-Efficacy.” [ Doctoral dissertation, University of Kentucky. Educational Leadership Studies. 29. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/edl_etds/29.

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioural Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bandura, A. 1995. Exercise of Personal and Collective Efficacy in Changing Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blonder, R., N. Benny, and G. Jones. 2014. “Teaching Self-Efficacy of Science Teachers.” In The Role of Science Teacher Beliefs in International Classrooms from Teacher Actions to Student Learning, edited by R. Evans, J. Luft, C. Czerniak, and C. Pea, 3–15. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Bolton, S. W. 2017. Educational Equity in New Zealand: Successes, Challenges & opportunities. Wellington, NZ: Fullbright New Zealand.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 2009. Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Costa, A. L., and B. Kallick. 1993. “Through the Lens of a Critical Friend.” Educational Leadership 51 (2): 49–51.

- George, S. V., P. W. Richardson, and H. M. Watt. 2018. “Early Career Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: A Longitudinal Study from Australia.” Australian Journal of Education 62 (2): 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944118779601.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

- Hattie, J. 2008. Visible Learning. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Kavanoz, S., H. Yuksel, and E. Ozcan. 2015. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Perceptions on Web Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Computer & Education 85:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.005.

- Korthagen, F., J. Loughran, and T. Russell. 2006. “Developing Fundamental Principles for Teacher Education Programs and Practices.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (8): 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022.

- Lazarides, R., and L. M. Warner. 2020. “Teacher Self-Efficacy.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.890.

- Ma, K., and M. S. Cavanagh. 2018. “Classroom Ready? Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy for Their First Professional Experience Placement.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43 (7): 134–151. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n7.8.

- Ministry of Education. 2018. “Achievement and Progress in Mathematics, Reading and Writing in Primary Schooling.” www.educationcounts.

- Ministry of Education. 2020.“Teaching as Inquiry.” https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/Teaching-asinquiry.

- Morris, D. B. 2017. “Teaching Self-Efficacy.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.86.

- Neuman, W. L. 2003. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. New York: Allyn & Bacon.

- OECD. 2016. “Who and Where are the Low-Performing Students?” In Low-Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How to Help Them Succeed. Paris: OECD Publishing, 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264250246-en.

- Pajares, M. F. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62 (3): 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307.

- Pendergast, D. N. N., S. Garvis, and J. Keogh. 2011. “Pre-Service Student-Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs: An Insight into the Making of Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 36 (12): 46–57. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n12.6.

- Poulou, M. 2007. “Personal Teaching Efficacy and Its Sources: Student Teachers’ Perceptions.” Educational Psychology 27 (2): 191–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601066693.

- Rubie-Davies, C. M., M. Webber, and H. Turner. 2018. “Māori Students Flourishing in Education: High Teacher Expectations, Cultural Responsiveness and Family-School Partnerships.” In Big Theories Revisited 2, edited by G. A. D. Liem and D. M. McInerney, 213–235. Hong Kong: Information Age Publishing.

- Siwatu, K. 2011. “Preservice Teachers’ Culturally Responsive Teaching Self-Efficacy-Forming Experiences: A Mixed Methods Study.” The Journal of Educational Research 104 (5): 360–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2010.487081.

- Thommen, D., U. Grob, F. Lauermann, R. M. Klassen, and A. K. Praetorius. 2022. “Different Levels of Context-Specificity of Teacher Self-Efficacy and Their Relations with Teacher Quality.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857526.

- Timperley, H., L. Kaser, and J. Halbert. 2014. A Framework for Transforming Learning in Schools: Innovation and the Spiral of Inquiry. Melbourne: Centre for Strategic Education.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., and A. Woolfolk Hoy. 2001. “Teacher Efficacy: Capturing an Elusive Construct.” Teaching and Teacher Education 17 (7): 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1.

- UNESCO. 2017. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- Usher, E. L., and J. A. Chen. 2017. “Reconceptualizing the Sources of Teaching Self-Efficacy: A Critical Review of Emerging Literature.” Educational Psychology Review 29 (4): 795–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9378-y.

- Yough, M. 2019. “Tapping the Sources of Self-Efficacy: Promoting Preservice Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy for Instructing English Language Learners.” The Teacher Educator 54 (3): 206–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2018.1534031.

- Zee, M., and H. M. Y. Koomen. 2016. “Teacher Self-Efficacy and Its Effects on Classroom Processes, Student Academic Adjustment, and Teacher Well-Being: A Synthesis of 40 Years of Research.” Review of Educational Research 8 (4): 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801.