ABSTRACT

Since student teachers’ emotions during field experiences are highly relevant to their overall learning and professional development, they are worthy of closer investigation. Thus, based on longitudinal data and co-occurrence network analyses, this study determines whether and how often positive and negative emotions co-occur among a sample of student teachers at three different timepoints (beginning, middle, and end) of a 15-week field experience. The findings revealed that a significant number of student teachers experienced mixed emotions, with the frequent co-occurrence of feeling stressed alongside positive emotions such as interest, attentiveness, excitement, strength, and confidence. Moreover, the proportion and structure of emotional co-occurrences changed over time. Notably, the prevalence of mixed emotions was higher in the initial and middle stages of the field experiences. These findings highlight the limitations of conventional correlation analyses in capturing important emotional information. The implications of these insights for student teacher support and development are discussed.

Introduction

In general, emotions are a part of everyday school life and are highly relevant for individuals aiming to productively engage in teaching and learning activities. The emotions of these stakeholders are also entwined in dynamic relationships, as widely reported in the correlation between teachers’ and students’ emotions (Becker et al. Citation2014; Goetz et al. Citation2021; Jennings and Greenberg Citation2009; Sutton and Wheatley Citation2003). As for teachers, emotions are of instrumental value, since they can both support and undermine student – teacher relationships (Bilz et al. Citation2022; Forster, Kuhbandner, and Hilbert Citation2022; Goetz et al. Citation2021), teaching efficacy (Carroll et al. Citation2021; Keller et al. Citation2014), and teacher well-being (Dreer Citation2021; Luque-Reca et al. Citation2022). Moreover, through a mechanism called ‘emotional contagion’, teachers have been shown to influence students’ emotions through their own display of emotions (Houser and Waldbuesser Citation2017; Mottet and Beebe Citation2000).

Since teachers’ day-to-day work routines often involve a wide array of impressions, certain amounts of uncertainty and ambivalence, and stressful situations, they most likely experience mixed emotions such as simultaneously feeling both happy and stressed (Berrios, Totterdell, and Kellett Citation2015; Fried Citation2011). Thus, the teaching profession calls for emotional engagement, regulation, and labour, which include acknowledging, reducing, exaggerating, and even faking emotions in relation to various professional situations and teaching goals (Burić and Frenzel Citation2020; Goran and Negoescu Citation2015; Schutz and Lee Citation2014; Taxer and Frenzel Citation2015).

Although there are differences in emotional closeness and the demands of emotional labour in regard to various school types (Hargreaves Citation2000), emotional intelligence and emotional regulation strategies are important components of teachers’ competencies (Jennings and Greenberg Citation2009). For student teachers, learning to develop such competencies involves diverse experiences, including understanding emotions and mastering emotional display and responses. In this regard, field experiences in teacher education present a great opportunity to experience different emotions, thus providing a rich context for developing regulatory competencies. However, research on the emotions of student teachers has been limited. Furthermore, little is known about how they feel, especially during the practical phases of teacher education. In order to narrow this gap, the present study focuses on the positive and negative emotions of a sample of student teachers, and investigates the co-occurrence of these emotions during a long-term field experience.

Student teachers’ emotions

Due to the importance of emotions in teaching, research has begun to explore student teachers’ emotions and their effects (Ahonen et al. Citation2015; Ketonen and Lonka Citation2012). On a theoretical basis, it has been argued that emotions are connected to various behavioural aspects and outcomes. It has also been posited that experiencing positive emotions is related to a greater openness for new experiences and methods, better workplace relationships, and more flexibility in dealing with unforeseen events and obstacles. Conversely, experiencing negative emotions is connected to a higher likeliness of adhering to familiar routines/methods, being less engaged in workplace relationships, and having difficulty dealing with unforeseen events and obstacles (Fredrickson Citation2001; Frenzel Citation2014).

In accordance with these suggestions, some studies have found that student teachers’ emotions are highly relevant in regard to social learning, identity development (Timoštšuk and Ugaste Citation2012), and professional development (Marais Citation2013). Related research has reported that student teachers’ emotions are significant in cognitive performance, decision-making, problem-solving, motivation, and achievement (Eren Citation2013; Linnenbrink-Garcia, Rogat, and Koskey Citation2011; Sutton and Wheatley Citation2003). Overall, such research supports the theoretical expectation that positive emotions are generally connected to beneficial outcomes, whereas negative emotions tend to be connected to unwanted outcomes.

Although one study found that students’ emotions when entering teacher education are fairly stable (Ripski, LoCasale-Crouch, and Decker Citation2011), initial teacher education has been described as an emotional journey, due to the wide array of learning situations/contexts such as attending courses, taking examinations, studying lessons, analysing videos, and engaging in field experiences (Anttila et al. Citation2016; de Zordo, Hagenauer, and Hascher Citation2019). It has also been argued that such situations and contexts must be disentangled to better understand student teachers’ emotions, emotional triggers, and patterns (Anttila et al. Citation2016). Moreover, Anttila et al. (Citation2017) found that emotions are triggered by task-related elements of teacher education such as fulfilled or unfulfilled expectations and sufficient or insufficient abilities. Similarly, the interview study by Lindqvist (Citation2019) revealed that teacher education is connected with student teachers’ challenging emotions, which can be triggered by a discrepancy between idealistic conceptions and field experiences.

These findings highlight the significance of field experiences in teacher education, since they enable student teachers to compare their expectations, ideas, skills, and identities with the real-life demands of teaching. Meanwhile, some studies have suggested the great potential of field experiences for eliciting various emotions. For example, de Zordo et al. (Citation2019) showed that student teachers’ emotions are triggered in anticipation of a teaching practicum. They also found that ability beliefs and motives are strong contributors to student teachers’ emotional states prior to the practical phases. Furthermore, their findings indicate that positive and negative emotions experienced by student teachers are uncorrelated, indicating that the rate of positive emotions is not connected to that of negative emotions.

In a qualitative approach, Marais (Citation2013) asked a sample of 96 student teachers to identify positive and negative emotions in relation to their practical experiences. They found that while both positive (e.g. happiness, satisfaction, and self-validation) and negative (e.g. fear and anger) emotions were generally experienced by the student teachers, positive emotions were more frequent. In a related interview study on the emotional triggers in identity development, emotions were reported in conjunction with different episodes and situations during field experiences (Timoštšuk and Ugaste Citation2012). Their results also indicated that positive emotions are often triggered by students, while negative emotions are reported in connection with personal experiences and thoughts as well as with feedback from teachers.

Based on these findings, negative emotions are suspected to be more influential towards the development of one’s professional identity. In another series of interviews, Waber et al. (Citation2021) investigated student teachers’ emotions in social situations during field experiences. They discovered that functional relationships (indicated by collaboration, support, and positive feedback) triggered positive emotions in student teachers, whereas dysfunctional relationships (indicated by failed communication, lack of support, and negative feedback) evoked negative emotions. In related research, student teachers’ emotional responses were linked with the teaching methods used during teaching trials (Timoštšuk, Kikas, and Normak Citation2016). The results also showed that good preparation and certain constructivist methods helped reduce negative emotions in the student teachers.

In sum, student teachers’ emotions, especially those elicited during the practical phases of teacher education, have only been investigated by several studies. Meanwhile, these studies only relied on cross-sectional data involving retrospective or single snapshot reports by student teachers. In addition, they focused on certain learning contexts and triggers for emotional patterns, but did not report on the magnitudes and trajectories of emotions.

As for the results of qualitative approaches, some student teachers have reported certain situations and factors connected to positive emotions, with other situations and factors connected to negative emotions during their field experiences. In general, positive emotions were more frequent than negative emotions (e.g. Marais Citation2013). Regarding the results of quantitative or mixed-methods research, they suggest that positive and negative emotions are either uncorrelated (e.g. de Zordo, Hagenauer, and Hascher Citation2019) or negatively linked (e.g. Eren Citation2013; Ripski, LoCasale-Crouch, and Decker Citation2011). However, one common limitation in the aforementioned studies is their lack of investigative focus on the co-occurrence of both positive and negative emotions within individuals.

Interestingly, the findings from research outside of teacher education have demonstrated that positive and negative emotions can simultaneously co-occur within individuals. For example, Simmons and Nelson (Citation2007) showed that in working contexts, some employees tend to experience stress along with positive emotions, while Moeller et al. (Citation2018) found that high school students experience mixed emotions within and across situations. More generally, a meta-analysis indicated that mixed emotions are a robust and measurable experience (e.g. Berrios, Totterdell, and Kellett Citation2015). Yet, the co-occurrence of positive and negative experiences in student teachers seems to be a ‘blind spot’ in the current literature, indicating that student teachers either feel good or bad in certain field situations. Thus, in order to inform future research and practice, the present study not only investigates the occurrence of mixed emotions among student teachers in field experiences, but also addresses the shortcomings of previous research.

Aims and research questions of the present study

While previous research has highlighted the importance of student teachers’ emotions for their professional development, little is known about the intricate interplay between different emotions and how these emotions evolve over the duration of their field experience. This is due to the lack of longitudinal approaches and sensitivity regarding the occurrences of mixed emotions among the individuals in previous studies. Hence, delving into the co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions at various stages within this crucial training period serves as an essential step towards better comprehending the nuanced emotional challenges encountered by future teachers. For that purpose, this study addresses two exploratory research questions:

To what extent is the co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions among student teachers at the beginning, middle, and end of a 15-week field experience?

To what extent does the occurrence of mixed emotions change over the course of the field experience?

Methods

Context

The research took place at the University of Erfurt, Germany, where a structured pre-service teacher education program is mandated by federal law. Erfurt’s program integrates 10 practical phases, both short and long-term, throughout the bachelor’s and master’s studies. These phases culminate in a complex 15-week practicum at the end of the master’s program, where student teachers are fully involved in daily school activities, fostering a deeper understanding of teaching and school life. This approach aims to consolidate competencies gained from previous teaching experiences and to facilitate student teachers’ transition into in-service teaching roles. The complex practicum unfolds within school settings for four days each week, complemented by workshops and coaching sessions at the university for one day weekly. The practicum teaching is supervised collaboratively by a university instructor and a cooperating teacher from the school. To encourage self-regulated exploration, student teachers are given autonomy in selecting their schools. Essential assignments include maintaining a development portfolio and delivering a final presentation on personal progress. While student teachers receive feedback from instructors and peers on their advancement regularly, all tasks remain ungraded to emphasise individual growth.

Procedure and sample

In this study, the data was recorded at three intervals, i.e. at the beginning (2 weeks), middle (8 weeks), and end (14 weeks) of the 15-week complex practicum. During the first interval, 170 student teachers (133 females, 36 males, and 1 non-binary/non-conforming; 23 to 51 years of age, M = 25.49, SD = 3.09) provided the necessary data. The participants were enrolled in a Master of Education program for primary (n = 148) or secondary (n = 21) education. The data was gathered as part of the coursework, which resulted in a 100% retention rate during the three intervals.

Ethics review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements valid at the time of data collection. The student teachers were treated in accordance with the code of ethics of the German Educational Research Association (https://www.dgfe.de/en/about-dgfe-gera/code-of-ethics). They were informed about the research objectives, after which they provided their voluntary informed consent to participate in the study. The data was treated confidentially and the anonymity of the participants was preserved at all times.

Instruments

The student teachers were asked to rate the intensity of 29 emotions on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). General positive and negative emotions were assessed by using the German version of the Positive-Negative Affect Schedule (Breyer and Bluemke Citation2016). This measure consists of two sub-scales that assess the positive affect (six items: alert, attentive, determined, enthusiastic, inspired, and proud; α = .89–.90) and the negative affect (six items: afraid, ashamed, hostile, irritable, jittery, and nervous; α = .84–.86). In addition, emotions that had previously been identified to be relevant in academic contexts were measured (Moeller et al. Citation2018). Specifically, the positive academic emotions included another eight items (active, confident, encouraged, excited, hopeful, interested, relieved, and strong; α = .82–.89), while the negative academic emotions included another nine items (bored, discouraged, distressed, frustrated, guilty, hopeless, scared, stressed, and upset; α = .82–.88).

For the purpose of analysing the relationship between the positive and negative emotions, both measures were combined, resulting in one scale that assessed the positive emotions at interval 1 (14 items; M = 3.49; SD = 0.62; α = .89), interval 2 (14 items, M = 3.70; SD = 0.59; α = .91), and interval 3 (14 items, M = 3.83; SD = 0.66; α = .93), and one scale that assessed the negative emotions at interval 1 (15 items, M = 1.68; SD = 0.45; α = .84), interval 2 (15 items, M = 1.60; SD = 0.45; α = .86), and interval 3 (15 items, M = 1.48; SD = 0.43; α = .83).

Data analysis

In order to analyse the descriptive statistics, correlations, and internal consistencies of the sub-scales, data analysis was conducted by using SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 software. GEPHI 0.10.1 software was used to perform one separate network analysis per measurement interval (three in total: beginning, middle, and end of the practical phase). For each analysis, this study closely followed the data preparation steps of Moeller et al. (Citation2018), who pioneered co-occurrence network analyses of emotion ratings. For this type of analysis, a dataset is compiled containing a list of all intra-individual pairs of highly rated emotions. In this regard, two emotions co-occur if they are both highly rated by the same student teacher, i.e. equal to or higher than 2.5 on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The rationale for selecting this cut-off was that (a) it intuitively distinguishes low ratings from high ones, and (b) every emotion experienced with more than 50% intensity can co-occur with any other emotion with the same intensity. Following this rule, the prepared datasheets for the student teachers contained 17.322 emotion pairings at interval 1, 17.480 emotion pairings at interval 2, and 15.892 emotion pairings at interval 3.

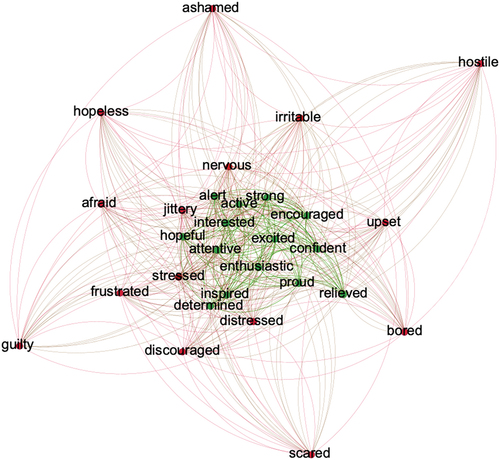

When compiling the network graph, each observed emotion with at least one co-occurrence was plotted and represented by a bubble (nodes), while the co-occurrences of two emotions were represented by connecting lines (edges). The network was chosen to be undirected, meaning that the sequence of occurrence (e.g. interested and attentive or attentive and interested) was considered as the same occurrence. Consequently, the edges were not displayed as pointed arrows. Moreover, in the network graph, positive emotions were coloured in green, with negative emotions coloured in red. As for the connecting lines between the emotions (the edges), they were coloured in red if connecting two negative emotions, green if connecting two positive emotions, and brown/orange if connecting a positive emotion with a negative one (see ). The number of times each connection was observed (edge weight) was configured to proportionally relate to the thickness of the respective line. Co-occurrences of emotions were visualised using GEPHI’s ForceAtlas2 algorithm (Jacomy et al. Citation2014), in which highly connected nodes are moved closer together and less connected nodes are moved apart from one another. Finally, the network was visually expanded by using GEPHI’s expand function.

Figure 1. Network analysis of the emotion ratings during the first interval (2 weeks), with negative emotions in red and positive emotions in green.

Results

In the first step, conventional correlation analyses were conducted. The results revealed small to medium and statistically significant associations between the combined emotion scales at all three intervals (see ).

Table 1. Correlations between the positive and negative emotion scales for all three intervals.

Based on the findings, the ratings of positive and negative emotions were connected over time. Specifically, the student teachers who experienced higher positive emotions at the start of the field experience were more likely to experience higher positive emotions during the later stages. The same finding was present for negative emotions, i.e. the student teachers who experienced higher negative emotions at the start of the field experience were more likely to report negative emotions during the later stages. In addition, the negative relationships between both emotions indicated that the student teachers either experienced higher positive and lower negative emotions or lower positive and higher negative emotions. To address the two research questions (RQ1 and RQ2), the results of the three network analyses are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Interval 1 (week 2)

During the first interval, the student teachers reported 17.322 pairings of highly rated emotions. Among the reported pairings, 70% were pairs of solely positive emotions, 5% were pairs of solely negative emotions, and 25% were pairs of mixed emotions. Regarding the first research question (RQ1), it was first examined how many student teachers reported high levels of at least one positive emotion and at least one negative emotion. The results suggest that mixed emotions were present at least once for each student teacher. The results further suggest that some mixed emotion pairings occurred more frequently than others.

As shown in , the top 10 most frequent connections during the first interval entirely consisted of co-occurrences of positive emotions, with mixed emotion pairings ranking lower on the list.

Table 2. Top 10 most frequent connections (edges) between emotion ratings during interval1 (Week 2).

The top five most reported mixed emotions during interval 1 included: interested and stressed (edge weight = 77), experienced by 45.29% of the student teachers; attentive and stressed (edge weight = 76), experienced by 44.7% of the student teachers; hopeful and stressed (edge weight = 72), experienced by 42.3% of the student teachers; stressed and confident (edge weight = 70), experienced by 41.2% of the student teachers; and strong and stressed (edge weight = 68), experienced by 40% of the student teachers. When analysing the correlations between the pairs of variables, small negative relationships were found (interested and stressed: r = −.137, p = .075; attentive and stressed: r = −.116, p = .134; hopeful and stressed: r = −.186, p = .015; confident and stressed: r = −.170, p = .027; and strong and stressed: r = −.170, p = .027). While these mixed emotions were experienced by approximately 45% of the student teachers, positive and negative emotions were simultaneously uncorrelated or negatively correlated.

As shown in , positive emotions (in green) primarily fill the centre, while negative emotions (in red) mostly fill the outer area of the graph. This illustrates that positive emotions frequently occur together. Meanwhile, the negative emotions of jittery, stressed, irritable, distressed, nervous, and afraid have the closest connections to positive emotions, i.e. they more often occur with positive emotions, in comparison to negative emotions such as scared, guilty, and bored. In addition, the thickness and colour of the edges illustrate that positive emotions are more often connected with one another (green edges) and to a stronger extent with negative emotions in a closer range (orange and brown edges). Finally, connections to the negative emotions in the outer area of the network appear as fine red lines, meaning that they occur less frequently. However, when they do, they are mostly red and more likely to occur with other negative emotions.

Interval 2 (8 weeks)

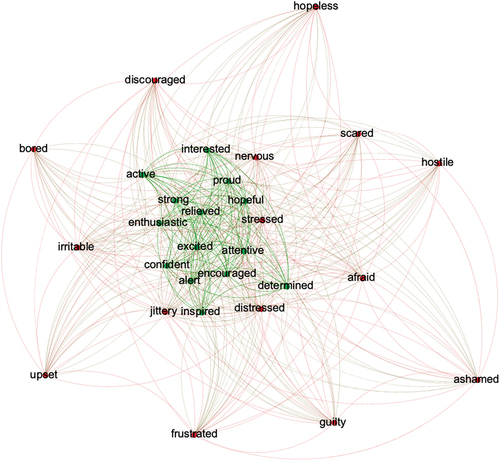

During the second interval, the student teachers reported 17.480 emotion pairings. Among the reported pairings, 74% were pairs of solely positive emotions, 4% were pairs of solely negative emotions, and 23% were pairs of mixed emotions. In comparison to the first interval, the share of co-occurring positive emotions slightly increased, while the shares of mixed emotions and co-occurring negative emotions slightly decreased. Regarding the first research question (RQ1), it was examined how many student teachers reported high levels of at least one positive and at least one negative emotion. The results again suggest that mixed emotions were present at least once for each student teacher. The results further suggest that some mixed emotion pairings occurred more often than others.

As shown in , the top 10 most frequent edges during the second interval only consist of co-occurrences of positive emotions, with mixed emotions ranking lower on the list. In comparison to the results of the first interval (RQ2), the top 10 emotion pairings changed in both order and combination. For example, while interested, attentive, and enthusiastic are still present, the nodes excited and confident are newly listed. This suggests a shift in the co-occurring positive emotion patterns over time.

Table 3. Top 10 most frequent connections (edges) between emotion ratings during interval2 (Week 8).

During the second interval, the top five most reported mixed emotions included: interested and stressed (edge weight = 85), experienced by 50% of the student teachers; attentive and stressed (edge weight = 84), experienced by 49.4% of the student teachers; active and stressed (edge weight = 83), experienced by 48.8% of the student teachers; stressed and excited (edge weight = 83), experienced by 48.8% of the student teachers; and stressed and confident (edge weight = 83), experienced by 48.8% of the student teachers. In comparison to the first interval (RQ2), the top five mixed emotions changed for two out of the five pairings. Specifically, instead of hopeful and stressed, it includes active and stressed, while strong and stressed are replaced by stressed and excited. This indicates a shift in the emotional patterns, which might be because the student teachers are no longer at the beginning of their practical phases.

When analysing the correlations between the pairs of mixed emotions, mostly small negative relationships were found (interested and stressed: r = −.19, p = .161; attentive and stressed: r = −.08, p = .308; active and stressed: r = .008, p = .917; stressed and excited: r = −.245, p < .001; and stressed and confident: r = −.190, p = .010). While approximately 50% of the student teachers experienced mixed emotions, these positive and negative emotions were simultaneously uncorrelated or negatively correlated.

According to , positive emotions (in green) during the second interval mostly fill the centre, while negative emotions (in red) mostly fill the outer area of the graph. Additionally, the negative emotions of jittery, nervous, distressed, and stressed occur within a closer range to the core of positive emotions. This indicates frequent co-occurrences between positive and negative emotions, particularly in comparison to the negative emotions in the outer area of the network such as ashamed, hostile, guilty, and scared. In comparison to the first network, afraid and irritable are more remote to the centre of this second network, indicating less frequent co-occurrences of these two negative emotions with the positive emotions at the centre. As in the first network, connections to the negative emotions in the outer area of the network often appear as fine red lines, suggesting that they occur less frequently. However, when they do, they are more likely to occur in conjunction with other negative emotions.

Interval 3 (14 weeks)

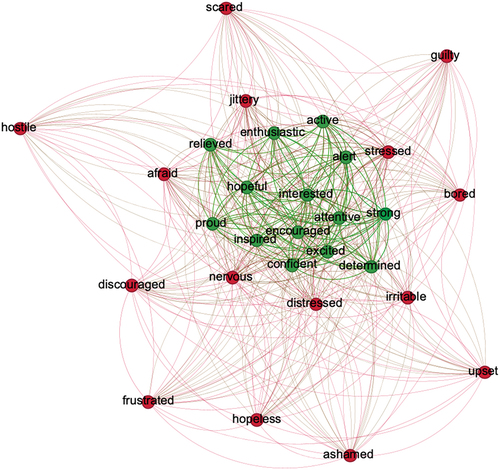

During the third interval, with 15.892 the student teachers reported less emotion pairings than the previous intervals. Among the reported pairings, 81% were pairs of solely positive emotions, 2% were pairs of solely negative emotions, and 16% were pairs of mixed emotions. Regarding the second research question (RQ2), the share of co-occurring positive emotions increased (i1: 70%, i2: 74%, i3: 81%), while the shares of mixed emotions (i1: 25%, i2: 23%, i3: 16%) and co-occurring negative emotions (i1: 5%, i2: 4%, i3: 2%) decreased over time. In regard to the first research question (RQ1), it was examined how many student teachers reported high levels of at least one positive and at least one negative emotion. The results again suggest that mixed emotions were present at least once for each student teacher. The results further suggest that some mixed emotion pairings occurred more often than others.

As shown in , the top 10 most frequent edges only consist of co-occurrences of positive emotions. In comparison to the results of the second interval (RQ2), the top 10 emotion pairings again changed in both order and combination. For instance, although interested, attentive, and excited are still present, the nodes determined, hopeful, and strong are newly listed, while active is removed from the list. This suggests another shift in the co-occurring positive emotion patterns.

Table 4. Top 10 most frequent connections (edges) between the emotion ratings during interval3 (week 14).

During the third interval, the top five most reported mixed emotions included: attentive and stressed (edge weight = 57), experienced by 35% of the student teachers; interested and stressed (edge weight = 56), experienced by 34.3% of the student teachers; enthusiastic and stressed (edge weight = 54), experienced by 33.1% of the student teachers; stressed and confident (edge weight = 53), experienced by 32.5% of the student teachers; and hopeful and stressed (edge weight = 53), experienced by 32.5% of the student teachers. In comparison to the second interval (RQ2), the structure of the top five list of mixed emotions did not change, while the overall share of mixed emotions decreased.

When analysing the correlations between the pairs of variables during the third interval, consistently small negative and statistically significant relationships were found (attentive and stressed: r = −.251, p < .001; interested and stressed: r = −.113, p = .151; enthusiastic and stressed: r = −.258, p < .001; stressed and confident: r = −.292, p < .001; and hopeful and stressed: r = −.305, p < .001). While approximately 35% of the student teachers experienced mixed emotions, these positive and negative emotions were simultaneously negatively correlated.

According to , positive emotions (in green) mostly fill in the centre, while negative emotions (in red) mostly fill the outer area of the network graph. However, during this interval, the distances between positive and negative emotions are generally larger, suggesting fewer connections. Conversely, the negative emotions of jittery, nervous, distressed, and stressed are even closer to the core of positive emotions. This indicates that at the end of the practical phase, positive and said negative emotions most often co-occur. In addition, connections to the negative emotions in the outer area of the network often appear as fine red lines, meaning that they occur less frequently. However, when they do, they are more likely to co-occur with other negative emotions.

Finally, upon examining all three network graphs in regard to the second research question (RQ2), it is apparent that the distances between the positive emotions in the core of the graphs and some selected negative emotions decrease, while the distances between the core of positive emotions and the negative emotions in the outer area increase over time.

Discussion

At first glance, the findings of this study reinforce the results of previous research. First, they are in accordance with the findings from qualitative research, indicating that the practical phases of teacher education are connected to positive and negative experiences of student teachers, while positive emotions are generally more dominant (Lindqvist Citation2019; Marais Citation2013). Second, the present study’s findings replicate the results from quantitative research on the negative relationship between the positive and negative emotions of student teachers (e.g. Eren Citation2013; Ripski, LoCasale-Crouch, and Decker Citation2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that student teachers tend to experience high positive and low negative or high negative and low positive emotions and that consequently practical phases during teacher education may be perceived generally as either good or bad experiences. Moreover, they imply that by addressing one emotional valence (e.g. fostering positive emotions through intervention) the other emotional valence can be influenced as well (e.g. reduction of negative emotions).

Upon closer examination by means of co-occurrence network analyses, this exploratory study offers some hints that question such previous considerations. Regarding the first research question (RQ1) on the extent of mixed emotions among student teachers, this study revealed that conventional correlation analyses generally overlook important information. While in sum most of the reported co-occurring emotions were of the same valence (positive-positive or negative-negative pairings), and the most frequent connections occurred between positive emotions, around a quarter of all co-occurring emotions were mixed emotions (positive-negative or negative-positive pairings). This translates to the finding that during every interval, each student teacher reported at least one mixed emotion pairing. In addition, 35%–50% of the student teachers experienced the same mixed emotions during each interval, indicating certain emotional patterns in relation to the practical phase of teacher education (Anttila et al. Citation2016, Citation2017). Among the mixed emotions that frequently occurred, the negative emotion of feeling stressed and positive emotions of interested, attentive, excited, strong, and confident were most frequently represented. Moreover, feeling distressed, nervous, and jittery were other negative emotions that frequently occurred in the mixed emotion pairings. In particular, experiencing stress in combination with positive emotions is in line with previous findings from different samples of college students (Moeller et al. Citation2018). Other negative emotions, such as bored, ashamed, and frustrated, were less often connected to other emotions.

Additional correlation analyses for frequently occurring pairs of mixed emotions indicated that these pairs were either uncorrelated or negatively connected. Interestingly, the correlations between emotion pairs became stronger and more often statistically significant in cases where the occurrence of mixed emotions decreased. This highlights the added value of the network analyses and that student teachers’ emotions are not sufficiently represented by conventional correlation analyses.

New insights were also derived in regard to the second research question (RQ2) on the potential changes in the occurrence of mixed emotions over the course of the field experience. Since longitudinal research on student teachers’ emotions during field experiences is scarce (Anttila et al. Citation2017), this study could not build on previously tested assumptions. However, it revealed that the share of mixed emotions decreased over time. Specifically, in the beginning, 25% of all co-occurring emotions were mixed, while in the end, their share amounted to only 16%. Meanwhile, the share of positive emotions increased over time, indicating that the student teachers’ emotions were connected to the developmental processes of familiarisation, adaptation, gaining control and developing competencies in the field. These processes have been well documented and are reflected in induction and mentoring frameworks (Dreer Citation2020; Hobson Citation2020). Moreover, the observed changes may suggest a growing proficiency among student teachers in navigating and regulating their emotions throughout their field experiences. Prior research has emphasised the importance of emotional labour, encompassing the regulation (displaying, suppressing, or amplifying) of genuine emotions, as a skill cultivated through teaching practice. Additionally, the improvement of emotional management skills is facilitated by interactions with mentors, who convey the norms and standards of professional conduct (Meyer Citation2009).

Interestingly, the total number of co-occurring emotions remained basically unchanged from the first to second interval but decreased from the second to third interval. This indicates that at the end of the practical phase, fewer co-occurring emotions were elicited. This also suggests that the student teachers’ feelings were more unambiguous. However, the suggestion that emotion rates generally decrease in the closing stages of a practical experience is not supported by the development of the scale means, which tend to decrease for negative emotions but increase for positive emotions.

Changes were also observed in regard to the structure of co-occurring emotions. For example, in the beginning of the practical phase, the student teachers frequently reported feeling interested in connection with attentive, awake, and hopeful. However, they reported frequent connections between feeling interested, excited, confident, and enthusiastic midway through the experience. In the end of the practical phase, feeling interested was frequently reported in conjunction with attentive, hopeful, and confident. In addition to these changes in co-occurring positive emotions, the structure of mixed emotions changed from the first to second interval. For instance, instead of hopeful and stressed during the first interval, the student teachers more frequently reported feeling active and stressed during the second interval. This could highlight that student teachers have shifted into a more active mode of engagement. Overall, such shifts in patterns have been previously reported (Anttila et al. Citation2017) and might relate to the fact that student teachers are moving forward in their professional development and gaining more confidence and skills (van der Want et al. Citation2018).

Likewise, such pattern changes might be explained by the external demands in the field (Alhebaishi Citation2019; Timoštšuk and Ugaste Citation2012). While student teachers are typically beginning their field experiences with lesson observations and are not quite sure of what to expect (eliciting co-occurring emotions such attentive, awake, hopeful, and stressed), they are asked to increase their commitment and engage in their own teaching trials towards the middle of the practical phase (eliciting co-occurring emotions such as interested, excited, active, and stressed). Finally, when their experience draws to a close, they might reflect on their gains and begin to look forward to transitioning into in-service teaching (eliciting co-occurring emotions such as attentive, hopeful, confident, and stressed). Accordingly, the observed changes in emotional patterns may also reflect a deepening sense of self-efficacy – a belief in the own capacity to accomplish tasks and overcome obstacles. Initially, as student teachers confront the complexities of classroom management, lesson planning, and student interaction, they may experience fluctuations in their emotional states. However, through ongoing exposure to real-world teaching scenarios and the guidance of experienced mentors, they gradually develop a greater sense of mastery and confidence in their abilities. This increased confidence may be reflected in their emotional states.

Such patterns and patterns shifts are worthy of further investigation, since they can be instrumental in designing better roadmaps for field experiences (Dreer Citation2022) and preparing mentors for their tasks (Bullough Jr and Draper Citation2004; Hawkey Citation2006; Richter et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, future studies should determine whether there are specific situations in field experiences that particularly trigger mixed emotions, like engaging in teaching activities or mentoring dialogues. Knowledge regarding such situations might be beneficial for better understanding the typical struggles of beginning teachers and effectively addressing job satisfaction and retention (Björk et al. Citation2019). When studying the effectiveness of interventions, it should be acknowledged that fostering the positive emotions of student teachers does not necessarily translate to a reduction in negative emotions, even if emotions are negatively correlated.

Implications

The presence of mixed emotions in this study and other samples from research outside of teacher education carry some theoretical implications. For example, while the broaden-and-build theory posits that positive emotions can broaden the scope of attention and action repertoires, and that negative emotions have the opposite effect (Fredrickson Citation2001; Fredrickson and Branigan Citation2005), it does not cover the cases of mixed emotions. How student teachers behave when simultaneously experiencing strong positive and negative emotions thus remains a theoretical gap that should be explored. Since it was suggested that mixed emotions can be helpful for securing successful adaptation and well-being in difficult situations (Braniecka et al. Citation2014), future research should investigate whether student teachers with higher rates of mixed emotions are the ones who experience more challenging situations at their respective schools and are better adapted to handle such situations.

Overall, more longitudinal research is necessary to gain more insights into the amplitudes and trajectories of student teachers’ emotions during field experiences. Since emotions are volatile, future research should use smaller distances between the measurements and approach the matter with other tools such as diaries, logs, and experience sampling (Keller et al. Citation2014).

In terms of practical implications, this study underscores that field experiences evoke a complex array of emotions, presenting a novel perspective for bolstering support for student teachers. Notably, this research suggests that fostering positive emotions in student teachers might not automatically diminish negative emotions. Consequently, it becomes imperative to empower teacher educators to provide nuanced emotional support, particularly in addressing the concurrent experience of both positive and negative emotions by student teachers. One approach could involve training mentors in techniques that facilitate open discussions about emotional experiences and encourage reflection on their underlying causes. Additionally, teacher educators should cultivate adaptability in their support strategies to meet the evolving emotional needs of their protégées. For instance, at the onset of field experiences and during teaching trials when uncertainty is heightened, support may need to address both positive and negative emotions. As student teachers progress through the practical phase and gain a sense of accomplishment, the focus of support could transition towards enhancing and sustaining positive emotions.

Limitations

In addition to these fields of interest, future studies should overcome the limitations of this research. First, this study focused solely on student teachers and their emotional experiences, without considering specific situations, critical incidents, or external demands during their practical phases. However, these environmental factors are suspected to influence the emergence, intensification, or attenuation of emotions during teaching practice (e.g. Alhebaishi Citation2019). To gain deeper insights into the potential causes of mixed emotions, future studies should incorporate and explore aspects of the practicum. As suggested by demands-resources frameworks, future explorations may encompass teaching tasks and demands, the quality of mentoring, and the level of social support available at the practicum school (Hartl et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, employing the critical incident technique (Badia, Becerril, and Gómez Citation2021) could help researchers to better understand the environmental factors causing mixed emotions in student teachers.

Next, co-occurrence network analyses warrant careful interpretation and replication to test the results and assumptions. In the future, significant advancements can be expected for both measurement and analysis of mixed emotions (Berrios, Totterdell, and Kellett Citation2015). Since these advancements may occur outside the field of teacher education, researchers should be aware of these discourses and productively transfer any innovations back into their research. One particular weakness of co-occurrence network analyses is the reliance on dichotomised data, which typically requires the researcher to choose a cut-off point and determine when emotions co-occur. Moeller et al. (Citation2018), who pioneered this technique in emotion research, argued that until a common definition of co-occurrence is agreed upon, it is reasonable to operationalise mixed emotions as two opposite emotions that are rated above the theoretical average. Nevertheless, it should be clearly stated that any changes to this definition or to its operationalisation will most certainly produce different results.

Finally, this study relied on well-defined and repeatedly tested emotion measures. However, the fixed set of emotions might have also triggered emotion ratings that the student teachers would not have otherwise considered. Conversely, a fixed set of items might have limited the scope of the structures and patterns identified in the data (Feldman Barrett and Russell Citation1998). It has been previously demonstrated that using open-ended questions (e.g. ‘How do you typically feel when you are in school? List up to three feelings’.) can be a broader approach to recording the emotions of individuals at the time of measurement (Moeller et al. Citation2018). Yet, this alternative approach is not without its disadvantages, since it involves the significant effort of categorising openly recorded emotions, with the high potential of misunderstandings and categorisation errors. Potentially, mixed-methods studies could help address these issues.

Acknowledgments

I thank Lara Hartmann and Sophie Charlotte Luz for their support in processing the large number of emotion pairings and Julia Moeller for her instructive workshop on network analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Dreer-Goethe

Benjamin Dreer-Goethe holds a Master of Education degree in secondary education and a PhD degree in educational sciences. He recently completed his postdoctoral qualification and is currently the scientific manager of the Erfurt School of Education, the centre for teacher education and educational research at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research interests lie in pre-service teacher education, especially in mentoring and enhancing conditions during field experiences. Furthermore, he is interested in understanding and fostering teacher and student teacher wellbeing and job satisfaction.

References

- Ahonen, E., K. Pyhältö, J. Pietarinen, and T. Soini. 2015. “Student teachers’ Key Learning Experiences–Mapping the Steps for Becoming a Professional Teacher.” International Journal of Higher Education 4 (1): 151–165. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v4n1p151.

- Alhebaishi S. M. (2019). Investigation of EFL Student Teachers’ Emotional Responses to Affective Situations during Practicum. European J Ed Res 8 (4): 1201–1215. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.8.4.1201.

- Anttila, H., K. Pyhältö, T. Soini, and J. Pietarinen. 2016. “How Does it Feel to Become a Teacher? Emotions in Teacher Education.” Social Psychology of Education 19 (3): 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9335-0.

- Anttila, H., K. Pyhältö, T. Soini, and J. Pietarinen. 2017. “From Anxiety to Enthusiasm: Emotional Patterns Among Student Teachers.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (4): 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1349095.

- Badia, A., L. Becerril, and M. Gómez. 2021. “Four Types of teachers’ Voices on Critical Incidents in Teaching.” Teacher Development 25 (2): 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2021.1882549.

- Becker, E. S., T. Goetz, V. Morger, and J. Ranellucci. 2014. “The Importance of teachers’ Emotions and Instructional Behavior for their students’ Emotions–An Experience Sampling Analysis.” Teaching and Teacher Education 43:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.002.

- Berrios, R., P. Totterdell, and S. Kellett. 2015. “Eliciting Mixed Emotions: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Models, Types, and Measures.” Frontiers in Psychology 6:428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00428.

- Bilz, L., S. M. Fischer, A.-C. Hoppe-Herfurth, and N. John. 2022. “A Consequential Partnership.” Zeitschrift für Psychologie 230 (3): 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000497.

- Björk, L., J. Stengård, M. Söderberg, E. Andersson, and G. Wastensson. 2019. “Beginning teachers’ Work Satisfaction, Self-Efficacy and Willingness to Stay in the Profession: A Question of Job Demands-Resources Balance?” Teachers & Teaching 25 (8): 955–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1688288.

- Braniecka, A., E. Trzebińska, A. Dowgiert, A. Wytykowska, and A. V. García. 2014. “Mixed Emotions and Coping: The Benefits of Secondary Emotions.” Public Library of Science ONE 9 (8): e103940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103940.

- Breyer, B., and M. Bluemke. 2016. “Deutsche Version der Positive and Negative Affect Schedule PANAS [German Version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule PANAS].” https://doi.org/10.6102/zis242.

- Bullough Jr, R. V., Jr., and R. J. Draper. 2004. “Mentoring and the Emotions.” Journal of Education for Teaching 30 (3): 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747042000309493.

- Burić, I., and A. C. Frenzel. 2020. “Teacher Emotional Labour, Instructional Strategies, and students’ Academic Engagement: A Multilevel Analysis.” Teachers & Teaching 27 (5): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740194.

- Carroll, A., A. York, S. Fynes-Clinton, E. Sanders-O’Connor, L. Flynn, J. Bower, K. Forrest, and M. Ziaei. 2021. “The Downstream Effects of Teacher Well-Being Programs: Improvements in teachers’ Stress, Cognition and Well-Being Benefit Their Students.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:689628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689628.

- de Zordo, L., G. Hagenauer, and T. Hascher. 2019. “Student teachers’ Emotions in Anticipation of Their First Team Practicum.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (10): 1758–1767. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1665321.

- Dreer, B. 2020. “Towards a Better Understanding of Psychological Needs of Student Teachers During Field Experiences.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (5): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1744557.

- Dreer, B. 2021. “Teachers’ Well-Being and Job Satisfaction: The Important Role of Positive Emotions in the Workplace.” Educational Studies (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.1940872.

- Dreer, B. 2022. “Creating Meaningful Field Experiences: The Application of the Job Crafting Concept to Student teachers’ Practical Learning.” Journal of Education for Teaching 49 (4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2022.2122707.

- Eren, A. 2013. “Prospective teachers’ Perceptions of Instrumentality, Boredom Coping Strategies, and Four Aspects of Engagement.” Teaching Education 24 (3): 302–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2012.724053.

- Feldman Barrett, L., and J. A. Russell. 1998. “Independence and Bipolarity in the Structure of Current Affect.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (4): 967–984. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.967.

- Forster, M., C. Kuhbandner, and S. Hilbert. 2022. “Teacher Well-Being: Teachers’ Goals and Emotions for Students Showing Undesirable Behaviors Count More than that for Students Showing Desirable Behaviors.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842231.

- Fredrickson, B. L. 2001. “The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-And-Build Theory of Positive Emotions.” American Psychologist 56 (3): 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

- Fredrickson, B. L., and C. Branigan. 2005. “Positive Emotions Broaden the Scope of Attention and Thought-Action Repertoires.” Cognition and Emotion 19 (3): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000238.

- Frenzel, A. C. 2014. “Teacher Emotions.” In International Handbook of Emotions in Education, edited by A. Linnenbrink-Garcia and R. Pekrun, 494–519. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Fried, L. 2011. “Teaching Teachers About Emotion Regulation in the Classroom.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 36 (3): 117–127. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n3.1.

- Goetz, T., M. Bieleke, K. Gogol, J. van Tartwijk, T. Mainhard, A. A. Lipnevich, and R. Pekrun. 2021. “Getting Along and Feeling Good: Reciprocal Associations between Student–Teacher Relationship Quality and students’ Emotions.” Learning and Instruction 71:101349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101349.

- Goran, L., and G. Negoescu. 2015. “Emotions at Work. The Management of Emotions in the Act of Teaching.” Procedia – Social & Behavioral Sciences 180:1605–1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.314.

- Hargreaves, A. 2000. “Mixed Emotions: Teachers’ Perceptions of their Interactions with Students.” Teaching and Teacher Education 16 (8): 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7.

- Hartl, A., D. Holzberger, J. Hugo, K. Wolf, and M. Kunter. 2022. “Promoting Student teachers’ Well-Being: A Multi-Study Approach Investigating the Longitudinal Relationship Between Emotional Exhaustion, Emotional Support, and the Intentions of Dropping Out of University.” Zeitschrift für Psychologie 230 (3): 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000495.

- Hawkey, K. 2006. “Emotional Intelligence and Mentoring in Pre-Service Teacher Education: A Literature Review.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 14 (2): 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260500493485.

- Hobson, A. J. 2020. “On SIDE Mentoring: A Framework for Supporting Professional Learning, Development, and Wellbeing.” In The Wiley International Handbook of Mentoring: Paradigms, Practices, Programs, and Possibilities, edited by B. J. Irby, L. J. Searby, F. K. Kochan, R. Garza, and N. Abdelrahman, 521–545. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Houser, M. L., and C. Waldbuesser. 2017. “Emotional Contagion in the Classroom: The Impact of Teacher Satisfaction and Confirmation on Perceptions of Student Nonverbal Classroom Behavior.” College Teaching 65 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2016.1189390.

- Jacomy, M., T. Venturini, S. Heymann, M. Bastian, and M. R. Muldoon. 2014. “ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software.” Public Library of Science One 9 (6): e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

- Jennings, P. A., and M. T. Greenberg. 2009. “The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research 79 (1): 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693.

- Keller, M. M., A. C. Frenzel, T. Goetz, R. Pekrun, and L. Hensley. 2014. “Exploring Teacher Emotions: A Literature Review and an Experience Sampling Study.” In Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice, edited by P. W. Richardson, S. Karabenick, and H. M. G. Watt, 69–82. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Ketonen, E., and K. Lonka. 2012. “Do Situational Academic Emotions Predict Academic Outcomes in a Lecture Course?” Procedia – Social & Behavioral Sciences 69:1901–1910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.144.

- Lindqvist, H. 2019. “Strategies to Cope with Emotionally Challenging Situations in Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (5): 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1674565.

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., T. K. Rogat, and K. L. K. Koskey. 2011. “Affect and Engagement during Small Group Instruction.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (1): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.09.001.

- Luque-Reca, O., I. García-Martínez, M. Pulido-Martos, J. Lorenzo Burguera, and J. M. Augusto-Landa. 2022. “Teachers’ Life Satisfaction: A Structural Equation Model Analyzing the Role of Trait Emotion Regulation, Intrinsic Job Satisfaction and Affect.” Teaching and Teacher Education 113:103668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103668.

- Marais, P. 2013. “Feeling is Believing: Student teachers’ Expressions of their Emotions.” Journal of Social Sciences 35 (3): 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2013.11893160.

- Meyer, D. K. 2009. “Entering the Emotional Practices of Teaching.” In Advances in Teacher Emotion Research: The Impact on teachers’ Lives, edited by P. Schutz and M. Zembylas, 73–91. New York: Springer.

- Moeller, J., Z. Ivcevic, M. A. Brackett, and A. E. White. 2018. “Mixed Emotions: Network Analyses of Intra-Individual Co-Occurrences with in and Across Situations.” Emotion 18 (8): 1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000419.

- Mottet, T. P., and S. A. Beebe. 2000. “Emotional Contagion in the Classroom: An Examination of How Teacher and Student Emotions are Related.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association, Seattle, WA, November 2000.

- Richter, D., M. Kunter, O. Lüdtke, U. Klusmann, Y. Anders, and J. Baumert. 2013. “How Different Mentoring Approaches Affect Beginning teachers’ Development in the First Years of Practice.” Teaching and Teacher Education 36:166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.012.

- Ripski, M. B., J. LoCasale-Crouch, and L. Decker. 2011. “Preservice Teachers: Dispositional Traits, Emotional States, and Quality of Teacher–Student Interactions.” Teacher Education Quarterly 38 (2): 77–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23479694.

- Schutz, P. A., and M. A. Lee. 2014. “Teacher Emotion, Emotional Labor and Teacher Identity.” In English as a Foreign Language Teacher Education, edited by J. D. M. Agudo, 167–186. Leiden, NL: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789401210485_011.

- Simmons, B., and D. Nelson. 2007. “Eustress at Work: Extending the Holistic Stress Model.” In Positive Organizational Behavior, edited by D. L. Nelson, 40–54. London, UK: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446212752.n4.

- Sutton, R. E., and K. F. Wheatley. 2003. “Teachers’ Emotions and Teaching: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Future.” Educational Psychology Review 15 (4): 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026131715856.

- Taxer, J. L., and A. C. Frenzel. 2015. “Facets of teachers’ Emotional Lives: A Quantitative Investigation of teachers’ Genuine, Faked, and Hidden Emotions.” Teaching and Teacher Education 49:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.003.

- Timoštšuk, I., E. Kikas, and M. Normak. 2016. “Student teachers’ Emotional Teaching Experiences in Relation to different Teaching Methods.” Educational Studies 42 (3): 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1167674.

- Timoštšuk, I., and A. Ugaste. 2012. “The Role of Emotions in Student teachers’ Professional Identity.” European Journal of Teacher Education 35 (4): 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.662637.

- van der Want, A. C., P. den Brok, D. Beijaard, M. Brekelmans, L. C. A. Claessens, and H. J. M. Pennings. 2018. “Changes Over Time in teachers’ Interpersonal Role Identity.” Research Papers in Education 33 (3): 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1302501.

- Waber, J., G. Hagenauer, T. Hascher, and L. de Zordo. 2021. “Emotions in Social Interactions in Pre-Service teachers’ Team Practica.” Teachers & Teaching 27 (6): 520–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1977271.