ABSTRACT

The literature on environmental security often stresses the complementarity between sustainability and broader security goals. Less emphasis has been placed on possible trade-offs between security objectives and aspects of sustainability. This study examines the conditions under which these synergies and trade-offs are likely to occur, and how the trade-offs can be reconciled, especially during times of peacebuilding. As a case study, we analyse the effect of Israeli security concerns on environmental infrastructure designed to treat wastewater in the West Bank. This study identifies several sustainability–security trade-offs: (1) economic—in which security concerns raise costs of wastewater infrastructure, thereby crowding-out other potentially productive investments; (2) equity—in which security concerns result in disproportionate exposure of populations to environmental hazards; and (3) environmental—in which security concerns increase ecological footprints. Yet, our case study also indicates that both sides used a variety of creative measures to reconcile these trade-offs.

EDITOR D. Koutsoyiannis GUEST EDITOR K. Aggestam

1 Introduction

The nexus between environment and security has been widely discussed since the 1980s (UNDP Citation1994, Barnett Citation2001, Diehl and Gleditsch Citation2001). Indeed, since the seminal report, Our Common Future (WCED Citation1987), which dedicated a full chapter to “Peace, Security, Development and the Environment”, a wealth of literature has addressed the issue of environmental degradation as both a direct and indirect causal factor of armed conflict. (For a review of such literature, see Khagram and Ali Citation2006.) The literature dealing with direct causal links tends to focus on wars over scarcity of critical resources such as water or energy sources (e.g. Myers Citation1989, Citation1993, Citation1993, Citation2005, Gleick Citation1991, Gleditsch Citation1998, Klare Citation2001, Renner Citation2002, Citation2005, Katz Citation2011), or the hypothesis that resource abundance has both financed and motivated conflicts (e.g. Collier and Hoeffler Citation2000, Le Billon Citation2001). Much less attention has been given to the environmental and sustainability implications of security concerns.

These links have been publicly recognized not only by researchers, but also by top political and military officials (see, for example, Dycus Citation1996, CNA Citation2007). This has led to governmental and intergovernmental initiatives establishing research centres dedicated specifically to the study of the link between the environment and security, and to the formation of several NGOs dedicated to pursuing joint environment and security goals (e.g. Conca and Carius et al. Citation2005, FoEME Citation2007), as well as to formal recognition of this link in many international forums such as the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (Principle 25, UNCED Citation1992, the European Security Strategy, and the UN High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges, and Change (UNROL Citation2004).

Either explicitly or implicitly, the literature on environmental security often assumes a complementarity or common agenda between promoting environmental and broader security goals. Assuming that sustainability leads to security, and vice versa, has shifted the focus of the research community towards identifying policy interventions that can enhance resource sustainability as a prerequisite for security (e.g. Homer-Dixon Citation1994, Citation1999, Levy Citation1995).

While such complementarity between environmental and security objectives certainly exists in many cases, real and sometimes substantial trade-offs between security objectives and other aspects of sustainable development are often overlooked. In order to better understand the environment–security nexus, it is imperative to identify under which conditions security objectives are synergistic with environmental goals and under which they will entail trade-offs with environmental objectives. Furthermore, it is critical to know what forms of trade-offs are likely to occur, and how positive synergies can be increased and detrimental effects avoided or minimized in order to reduce tensions between these two sometimes competing policy goals.

This study takes a positivist approach to both security and sustainability concerns. This approach is in contrast to the current literature that tends to look at these terms from a constructivist standpoint. While the former approach accepts the legitimacy and validity of both concepts, the latter views them as rhetorical and linguistic mechanisms used with the intention of placing them on the radar of policymakers. Hence, it views them as a social construct rather than factual events and concerns.Footnote1 Another clarification is that when using the term “security”, this study focuses on conventional notions of national security, rather than other forms of security such as human security. Thus, the paper focuses on the interplay between policies for national security and environmental objectives rather than on how individual insecurities intervene with local environmental conditions.

In order to identify the effects of security concerns on issues of sustainability we first outline a conceptual model that hypothesizes the synergies and trade-offs between environmental and security policies, from a sustainability perspective. We then apply this model using a case study of the effect of the Israeli security concerns on environmental infrastructure designed to treat wastewater in the West Bank between the onset of the Oslo peace process in the 1990s and 2010.

2 The interdependency of security and sustainability concerns

Security concerns lead to at least four basic responses that can affect environmental objectives. The first is the construction of redundant infrastructure systems, whose purpose is to improve the robustness of supply systems of critical resources. Greater security may provide for the stability necessary for stable and efficient use of resources, and, thus, reduce the need for superfluous facilities. For instance, it may allow for integrated supply networks or for trade that would reduce overall local consumption rates.Footnote2 However, the means of achieving security goals themselves may require redundancy of resource use and infrastructure. For instance, excessive water storage or energy supply capacity may be designed to forestall supply interruptions. Such redundancy has several direct implications.Footnote3 For one, it requires funds, thus crowding-out funding for projects or programmes that would be more productive had risk of conflict not been present. Furthermore, redundant critical infrastructure has direct effects on natural resources, hence entailing an increased ecological footprint. In addition, siting of such critical infrastructure may have adverse equity implications if it disproportionately affects disadvantaged groups.

A second issue is the actions taken to increase the reliability of supply in face of security concerns by diversifying supplies (Farrell and Zerriffi et al. Citation2004). Diversification may include variation in terms of both number suppliers as well as types of resources utilized. Greater national security may afford policymakers the luxury of relying on limited sources of supply, which could allow them to concentrate on the most efficient sources. However, diversification is often a means to achieve security (both national security and goals such as energy security or food security), and this almost invariably requires trade-offs in terms of economic efficiency, as it obviates economies of scale, and often entails additional infrastructure, thereby generating all of the above-noted redundant infrastructure effects. Moreover, the development of a more diverse set of sources may also have direct footprint effects, as it implies additional extraction, transport and disposal of resources.

A third direct action undertaken by various countries is to increase the resiliency of operating systems. This pertains to the establishment of different institutions, or capacities within existing institutions, that would assure the continued operation of the various governmental and economic functions during crises. Security services can be viewed as part of this response to security concerns. Greater security can provide for institutional economies of scale by, for instance, allowing for joint international management institutions. This would potentially reduce environmental impacts and provide for more effective resource management. However, provision of such security may require facilities and training grounds, with direct footprint effects. They also require funding, often quite substantial in scale, and as such increase the probability of a crowding-out effect, as noted above. In terms of equity, such security services may provide differential coverage to different parts of the population or country (whether due to differential costs or to discrimination). In addition, security agencies may target specific groups which may seem threatening from the perspective of these agencies.

In addition to the establishment of institutions, countries put in place emergency programmes. For instance, due to security concerns, countries establish monitoring systems that will give warning about threats. As noted above, these are seen as crucial for reducing the risk of disruptions due to hostile actions or to natural or manmade disasters. These systems are often seen as part or inputs to emergency programmes. In addition to the expense of these systems, they can also have direct equity implications, for the same reasons noted above. It is possible that parts of the system or country will not be monitored sufficiently, whether due to budget constraints or to discrimination. It is also possible that certain groups or areas will be monitored more closely, due to perceived threats (whether justified or not). This may impinge on the privacy or other rights of the monitored groups.

The causal relationships are not unidirectional. Security measures impact on sustainability due to their environmental implications. Concurrently, environmental policies can also impact on security concerns. As mentioned earlier, much of the literature focuses on the many synergies between security and sustainability, such as reducing environmental refugees and conflict over resource scarcity. However, again, such synergy cannot be assumed. For instance, as environmental interests gain political power, environmental and broader sustainable development concerns may increasingly impact on the location and design of security infrastructure and the timing and implementation of military training.Footnote4 In addition, causality may often involve feedback loops. For example, water or energy reserves designed to cope with short-term security threats can come at significant economic and environmental costs, and themselves may, in turn, become targets posing security and environmental threats. The existence of such multiple causal pathways for security–sustainability interaction reinforces the need for systematic critical thinking in terms of prioritizing policy goals so as to minimize trade-offs.

The discussion so far has focused on the environmental implications of security concerns. In the implications of the four security-driven actions outlined above are widened to include both the implications on equity and on the economy, the other two pillars of sustainability. Essentially, the desire to build redundant infrastructure as well as the security services biases and emergency systems can have equity impacts. As noted above they can come at the expense of minority groups seen as threatening by the dominant party involved, or at the expense of weaker strata of society who will bear a disproportionate share of the siting impacts of the redundant infrastructure, as these may be sited in proximity to those population groups least able to oppose them. By crowding-out productive investments, such actions, and particularly the building of redundant infrastructure, may have deleterious economic effects. Hence all three of the pillars of sustainability may be adversely affected by such actions. These implications may, in turn, have effects for security concerns, when widely viewed.

This brief outline demonstrates that the relationship between security concerns and sustainability, while often synergistic, is not always so. Nor can it be viewed in a purely “satisficing” framework; that is, that if a minimum level of security is maintained then it has no further implications for sustainability. On the contrary, the measures taken for security purposes may entail trade-offs with sustainability goals. Because each is shaped by separate policy networks, it is important for effective policies to understand how these networks interact and communicate across specialties. These interactions will be a function of the location of the relevant infrastructure vis-à-vis the different population groups, the attributes of these groups and their relative power, the financial ramification of the actions taken for security purposes, and the agencies involved and the power they are given. The nature and power of the agencies and actors in any specific case is a function of the institutional structure managing the particular infrastructure and its siting process.

The next sections examine the validity of the above model through evaluating the case of the impacts on sustainability of Israeli security concerns regarding critical wastewater and water infrastructure designed for the population of the West Bank. It differentiates between three periods. A period of parallel discourse in which security and sustainability were discussed separately, a period in which there were attempts to harmonize security and sustainability during a peacebuilding process, and a period of heightened conflict, in which security concerns over-rode sustainability ones.

3 Wastewater treatment on the Israeli–Palestinian border

3.1 The first era: until the 1990s

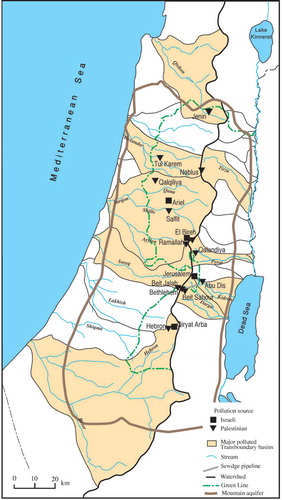

The Mountain Aquifer underlies both Israel and the West Bank and, as such, is shared between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (). The recharge zones of the aquifer are along the mountain ridge of the West Bank, predominately populated by Palestinians, while the primary natural outlets (springs) lie within Israel. The aquifer supplies most of the freshwater for the population of the West Bank and, prior to the adoption of desalination in Israel over the past decade, supplied roughly 40% of the total freshwater withdrawals of Israel. The Mountain Aquifer is also susceptible to pollution, due to its karst limestone/dolomite geological composition (Gvirtzman Citation2002). The spatial interdependency between upstream Palestinian and mostly downstream Israeli populations requires joint management of the aquifer in order to ensure its sustainability (e.g. Feitelson and Haddad Citation1998).

Prior to 1967, the West Bank was controlled by Jordan. In 1967 Israel occupied the West Bank, thereby gaining full control over the Mountain Aquifer and, with it, the responsibility for managing both the water resources and treatment of wastewater. The 1959 Israeli Water Law, which nationalized all water in Israel and established a centralized institutional system to manage it, was extended to the West Bank through Military Order 158, which required the area commander’s permission to operate water installations. Military Order 291 extended the jurisdiction of the Israeli Water Commissioner to all surface water and groundwater in the Occupied Territories. However, no similar order was issued regarding environmental affairs. Hence, Israeli environmental standards are not obligatory in the West Bank. Rather, the responsibility for the civil aspects of the West Bank, including infrastructure, was placed in the hands of the Civil Administration, a body affiliated with the Israeli Ministry of Defense, while the responsibility for security was retained by the Israeli army. This division between security and civil concerns, including the protection of the aquifers, created a disconnect, and sometimes tensions, between the Israeli authorities in charge of the various facets of the Palestinian population (Caesari Citation2007). One implication of this disconnect was that, while control over the sources of water supply in the Mountain Aquifer came to be seen by the Israeli authorities as a high-profile security issue, protection of it against pollution in both aquifers was not treated as such. This was consistent with the low priority afforded to pollution issues by Israeli governments during this period (Tal Citation2002).

As a result, although Israel did build and improve the water supply infrastructure for the Palestinian population following 1967 (Gvirtzman Citation2012), this was not accompanied by construction of sanitation systems. The wastewater systems that were built provided only collection or at most primary treatment for some of the major Palestinian urban centres, but these frequently malfunctioned or became overloaded (UNEP Citation2003). The Palestinian population had neither the political nor economic capacity to remedy this gap (Trottier Citation1999). In addition, the Israeli settlements, whose number rose substantially since the rise of the Likud government in 1977, also did not treat the wastewater, leading to pollution of streams and the aquifers (Hareuveny Citation2009).

The disconnect between sustainability and security was aggravated upon the outbreak of the first Intifada—Palestinian uprising—in the late 1980s. During this time security concerns became the focal point of the Israeli Civil Administration, while environmental considerations receded (Tal Citation2002). Many initiatives, including wastewater treatment, were delayed as the security situation in the West Bank and Israel deteriorated (Caesari Citation2007). Most Israeli activities focused instead on measures to reduce threats of violence against Israelis, often by paving bypasses or establishing checkpoints. These security measures had deleterious environmental implications, and can be seen as redundant infrastructure from a transportation perspective. Moreover, during this period the Palestinians were barred from decision making regarding the development of natural resources, such as water, or infrastructure, including wastewater treatment plants.

While Israel had not developed wastewater treatment systems in the West Bank, within Israel significant efforts were taken since the early 1990s to build wastewater plants nationwide and to upgrade the old ones (Bar-or Citation2006). West Bank sewage continued to be discharged into the environment at 350 locations (Meir Citation2004), only 8% of which was adequately treated (Nagar Citation2004). shows the major pollution sources, the status of wastewater projects and the boundaries of the Mountain Aquifer. Israeli initiatives in the 1990s to rehabilitate degraded coastal streams, most of which are shared with the West Bank, were concentrated on activities within Israel proper (Tal and Katz Citation2012).

In sum, Israeli occupation of the West Bank allowed for joint and unified management of the shared water resource, and thus avoidance of a potential tragedy of the commons. In reality, however, water provision was seen as a security issue and managed in a way that avoided over-withdrawals. But equity concerns were largely absent from water withdrawal management. Wastewater treatment and its effects, on the other hand, were not prioritized. After the outbreak of the Intifada, security concerns crowded-out environmental ones leading to delays in building and operation of treatment facilities.

3.2 The second era: peacebuilding and balancing interdependency in the 1990s

Following the onset of the peace process in Madrid in 1991, the nature of shared aquifers gained much attention. This was driven in part by widely publicized concerns that the increasing water scarcity in the region may ignite wars (e.g. Starr Citation1991). Water issues were negotiated in both bilateral and multilateral tracks. The former referred to direct negotiations between Israel and each of its immediate Arab neighbours. The latter focused on key issues that concern the entire Middle East, including working groups on water and on the environment. Wastewater issues received significant attention in these negotiations, as they were seen as clearly transboundary issues but that did not impinge on sovereignty (Feitelson and Levy Citation2006).

Parallel to the Madrid negotiations, Israelis and Palestinians negotiated along a separate track that resulted in the Oslo I Accord, signed in September 1993. That Accord noted the need for cooperation in the field of water and established a Palestinian Water Authority, whose powers and responsibilities were to be specified by the Interim Agreement (Article 7, paragraph 4). Subsequent to Oslo I, Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) signed the Oslo II Interim Agreement in September 1995, in which article 40 of Annex III addresses issues of water and sewage. It established a Joint Water Committee (JWC) to oversee the implementation of the agreement, with each side given veto power. All water projects in the West Bank must be approved by this body.Footnote5 Once approved by the JWC, the Israeli Civil Administration has to approve the planning. The Agreement also established an enforcement arm, termed Joint Supervision and Enforcement Teams (JSETs), comprised of both Israelis and Palestinians, with their members enjoying full mobility to water and wastewater facilities (Haddad et al. 1999).

According to the Agreement, the West Bank was divided into areas in which the PA was to have full jurisdiction (Area A), areas which remained wholly under Israeli control (Area C), and areas in which control over civil matters alone were transferred to the PA, while security policy remained in the hands of Israel (Area B). In addition, it included a mechanism that allows Israel to deduct Palestinian funds pertaining to water provision from money held by Israel for the Palestinian side.Footnote6

In the transfer of responsibilities to the Palestinian Authority, any water and wastewater initiative required the approval of the JWC and the operating of infrastructure was subject to JSET supervision. Infrastructure to be built in Area C was subject to the further approval of both the Israeli Civil Administration and the Israeli Ministry of Defense. The agreement also allowed having one maintenance unit to address system malfunctions on both sides.

The international donor community sought to help develop the capacity of the new Palestinian state. The German Government provided assistance for wastewater treatment, while the United States did the same for development of water supply infrastructure. Together the donor community earmarked around US $250 million for wastewater infrastructure, including building wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) for major Palestinian cities (Tagar Citation2007). This influx of earmarked funds provided Israel and the Palestinians an opportunity to address the pending wastewater problem that was endangering the sustainability of the aquifers, without crowding-out other vital investments necessary for the Palestinian economy and the new security measures required by the agreement.

Disagreements arose when the new infrastructure for the Palestinian cities Nablus, Hebron and Salfit was planned to be built in Area C. Building Palestinian civil infrastructure in Area C raised security and budgetary concerns for Israel, as it would be Israel’s responsibility to secure these works. The Israeli military did not want to bear these security costs (Herman Citation2007), but was aware that lack of Civil Administration approval would further delay the construction of all treatment facilities (Meital Citation2007). Israel was also afraid that approving Palestinian facilities in Area C would create a precedent for putting the burden on Israel for what it sees as a Palestinian responsibility, and as a result would turn areas under its control and/or along its border into a backyard of unwanted land uses (Yakobovitz Citation2007). In contrast, for the Palestinians, building WWTPs in Area C seemed essential because of the detrimental implications of locating hazardous sites next to urban populations, which comprised much of areas A and B. Due to the environmental urgency of the issue, Israel eventually acquiesced and approved the building of several plants in Area C. In the case of Salfit, for example, Israel changed the status of the area of the facility from C to B and adjusted its army deployment in the area (Herman Citation2007). Following a German request, Israel also ensured the Germans and Palestinians free access to the facility area (Yakobovitz Citation2007). After 2 years of negotiations over the location of the Nablus facility, Israel also indicated willingness to make a similar concession and allow the plant to be built in Area C. Due to concern for groundwater supplies, and because of pressure by local environmental organizations and the international community, a similar decision was also made to allow the Palestinians to build a solid waste treatment facility in Dir Dibwan in Area C, despite its proximity to a closed military area (Meital Citation2007).

Thus, in the period immediately following the interim peace treaty between Israel and the PLO, efforts were made by parties to compromise on security issues in order to promote environmental goals. While Israeli authorities often viewed environmental concerns as largely antagonistic to immediate security goals (e.g. development of WWTPs in proximity to security establishments), they often compromised for the sake of longer-term environmental and perhaps security goals (e.g. maintenance of working relations with the PA and with the donor community).

3.3 The third era: when security trumps sustainability concerns

For several years after the JWC was established its members accused each other of violating the previous agreements. The Palestinians refused an integrated system that would connect Israeli settlements to the wastewater facilities in the West Bank, as well as the reuse of wastewater. Although Palestinian officials recognized such options as technically desirable, as they would reduce the redundancy of infrastructure, they deemed them politically infeasible on the grounds that they would further entrench Israeli settlements (Brenner Citation1998). Israel, in return, conditioned the PA’s access to hazardous materials and the approval of Palestinian water projects on progress on the wastewater front (Eitan Citation1998). Attempts to establish new joint enforcement and monitoring teams for adjusting the existing agreement were not welcomed by Israeli authorities, which were afraid that these might impinge upon security issues (Ministry of Defense Citation1999).

These difficulties in implementing the regime were exacerbated when the Palestinian–Israeli conflict escalated with the outbreak of the second Intifada in September 2000. The Intifada caused considerable damage to the water and wastewater infrastructure in the West Bank. The JSETs stopped operating (Ministry of National Infrastructures Citation2002) and Israel established its own enforcement teams, but their mandate was restricted only to monitoring (Nagar Citation2003). The Intifada also paralysed all the progress made on the basis of previous wastewater agreements between Palestinian and Israeli local authorities across the “green line” separating the West Bank from Israel.Footnote7

Restrictions on movement of Palestinians were widely used by the Israeli military as a means of preventing Palestinian attacks against the Israeli civilian population and military. A system of some 600 physical barriers was erected, including manned checkpoints, road blocks, gates and trenches. The barriers and the overall security situation prevented the JSETs from taking water quality samples, treating wells on both sides (JWC Citation2001, World Bank Citation2009) and, in some cases, metering the amount of wastewater discharged by Palestinian communities (Regev Citation2001).

The security issues also prevented construction teams responsible for WWTPs funded and operated by the donor community from accessing their sites. For instance the German funding agencies specifically requested that the Israeli military provide military escort for the construction teams in their operations in order to ensure their safety, something that Israel was not willing to provide, both because they did not deem it a justified use of scarce military personnel and because of cost considerations (Herman Citation2007). Both the German and the American donors faced perceived security threats to their projects and employees, and an estimated increase of up to 35% and 25% (respectively) in project costs, due to Israeli security measures (Newman Citation2006). These security concerns eventually led to the cessation of planning and construction of several WWTPs, among them facilities in Salfit, Hebron and two near Nablus. Other projects, not cancelled by the German government, were delayed as they adopted a “phased approach” of postponement of the larger, higher-risk projects (Tagar Citation2007).

Thus, the general attempt at synergistic development of both broad security and environmental and development goals that typified the period just after the signing of the Peace Agreement was replaced by security measures that impeded sustainable development during a period of conflict.

3.4 Recent attempts to address security and environmental concerns

Following the deterioration in security since the outbreak of the second Intifada, Israel has attempted to concentrate water and sewage infrastructure lines along the main roads, all in Area C, under complete Israeli control. Also, Israeli controlled water infrastructure is being relocated towards the new separation barrier (Zorea Citation2007). This, according to officials, allows Israel to respond quickly to any security threats to these infrastructures and enables safe maintenance necessary for the resiliency of the operation systems. However, as the old pipelines and water reservoirs have not been dismantled (Tal Citation2007), such relocation widens the wastewater infrastructure’s ecological footprint. Moreover, such relocation has significant economic costs (Zorea Citation2007, Tal Citation2007), which has crowding-out implications.

Israel has also relocated WWTPs designed to treat Palestinian wastewater from the West Bank to Israeli territory, which does not require Palestinian consent. Examples include the planned Hebron WWTP that was replaced by a WWTP next to the Israeli community of Meitar and the WWTP to treat the wastewater of Tul Karem and Nablus that was replaced by a treatment facility in Israel next to Kibbutz Yad Hanna (Brandeis Citation2001b). Furthermore, in order to minimize security concerns, Israel is considering the inclusion of suggested WWTP for the Kidron Valley, which flows from Jerusalem through the West Bank near Bethlehem, within the jurisdiction of the city of Jerusalem despite this being a technically inferior location.

Building WWTPs on the Israeli side allows Israel to reduce the likelihood of future security threats to the facilities. However, it involves important trade-offs in terms of environmental quality, economic efficiency and equity. Firstly, sewage flows greater distances before treatment, rather than being treated near the source. This has both environmental consequences, e.g. potential seepage and contamination of groundwater, and equity concerns in that additional populations are now exposed to untreated sewage. In the case of Kibbutz Yad Hanna, the relocation was also accompanied by new access roads (Shoam Citation2007) and security defence measures (Brandeis Citation2001), thus enlarging the ecological footprint of the facility. In the case of the Kidron Valley, building the WWTP in a technically inferior location not only means that the facility will not intercept the downstream wastewater of the Palestinian city of Bethlehem, but also will substantially increase its cost. In addition, it may raise environmental justice issues as the new facility is located adjacent to population centres (Nagar Citation2006).

Finally, another equity issue involves the distribution of cost of the infrastructure. Many of the WWTPs are being paid for by Palestinian taxes via the offset mechanism mentioned above. This new cost-burden arrangement has come at great economic expense, crowding-out spending on other productive investments for the Palestinians. By building infrastructure unilaterally, it has also reduced the number of parties involved in the decision-making process to only Israeli ones. This has affected the equity and legitimacy of their decisions. The result of this security footprint is both intra-generational and inter-generational, with detrimental implications that erode the ability to follow sustainable development paths both for Israelis and Palestinians.

summarizes the policy measures taken by Israel and their implications in terms of security, environment and equity in the four periods discussed above. It also outlines some of the counter measures used to mitigate these trade-offs.

Table 1. Policy measures, implications and counter measures.

4 Discussion—factors affecting security’s environmental footprint

An understanding of the broader political context is essential for understanding any water and sanitation management (Swyngedouw Citation2009a, Citation2009b). In the context of a political conflict between populations whose water resources are interdependent, this includes understanding of the security context. While control over water resources has long been viewed as a high-profile national security issue in the Middle East (e.g. Allan Citation2001), treatment of wastewater was not. This study shows that national security concerns had a profound impact on the provision of wastewater infrastructure. identifies different characteristics of wastewater treatment and optimal elements for each characteristic from the perspective of the different components of sustainability and of security. It also shows the solution adopted in practice. In practice, convergence of optimal elements is rare. For example, for optimizing environmental considerations, WWTPs should be located next to the source of the pollution, in Area A, while for optimizing Israeli security considerations, WWTPs should be located inside the Green Line. This explains why, at least in the design of wastewater treatment facilities, there are distinct trade-offs between security and sustainability considerations. It also shows that the actual policies undertaken correspond first and foremost with Israeli security concerns, thereby reflecting the power monopoly of Israel in this context.

Table 2. Characteristics of WWTPs and their correspondence to sustainability and security issues.

A major impact of security in terms of wastewater treatment, in addition to new infrastructure construction, was also increases in the costs of planning, coordination and maintenance. The many checkpoints and barriers put up by Israel and the resulting political reluctance of Palestinian and donor agencies to cooperate with Israeli authorities have caused considerable delays in the design and construction process that have raised the cost of WWTPs beyond what the donor community has been willing to pay. Also the high degree of involvement of many Israeli security-related bodies, such as the Israeli Defense Ministry and the military, in the planning and authorization of civil wastewater infrastructure in the West Bank delayed the authorization required to build WWTPs.

Israel’s national security, footprint was not distributed equally in time and space which implies that the degree of security–sustainability trade-offs is affected by contextual factors that change over time. In the 1990s, during the peacebuilding process and prior to the outbreak of the Intifada, there were genuine attempts to balance security and sustainability concerns. These were enabled by both the political impetus of the peace process itself, the lower instances of violence, which reduced the perceived need for drastic security measures, and the development of measures by policymakers to overcome the institutional fragmentation that allowed security concerns to override civil priorities. The result was the authorization of WWTPs, joint supervision and enforcement patrols, and, in some cases, changes in Israeli military deployment to allow the construction of WWTPs. Thus, not only did security concerns influence sustainability objectives, but sustainable development objectives influenced the manner in which security measures were designed and implemented. But, as the security situation deteriorated following the outbreak of the Intifada, security concerns increasingly over-rode other concerns, resulting in the increased costs of planning, construction, coordination and maintenance. Consequently, many international agencies withdrew or reduced the scope of their operation, thereby hampering further improvement of the wastewater infrastructure in the West Bank (Tagar Citation2007). More recent attempts to reconcile security concerns with environmental objectives have resulted in unilateral environmental policies by the Israeli authorities (Fischhendler et al. Citation2011). However, such solutions are far from optimal, environmentally or economically.

Much of the environmental footprint of security is a result of handling the environment and security as two separate concepts. This has resulted in institutional fragmentation, where the Israeli Civil Administration is responsible for civil affairs in the West Bank, while the Israeli military are responsible for security issues, (though both of these bodies are under the Ministry of Defense). In a situation of an ongoing military conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, this institutional fragmentation weakened the voice of the bodies that should represent civil and sustainability concerns, even during peaceful times.

Some of the security footprint was also aggravated by the role that borders have played in the Palestinian–Israeli conflict. In spite of the integrative nature of the Mountain Aquifer, the Green Line functioned not only as a political border, but also as an environmental one (Feitelson and Levy Citation2006). Different laws, regulations and enforcement levels are applied for the populations on each side of the border. Water allocations and investments in infrastructure were likewise uneven, with Israeli communities on both sides of the Green Line receiving a much bigger share of the resources than Palestinian communities. This asymmetrical setting has further pushed Israel to follow a disengagement process in an attempt to absorb the human and environmental insecurity in the West Bank often by a policy of unilateral environmentalism (Fischhendler et al. Citation2011) while neglecting the environmentally detrimental implications of this policy.

5 Conclusions

Over the last two decades the sustainability and security literature bodies have developed largely separately. The sustainable development literature has incorporated concepts such as resource efficiency and equity. The security literature, to the extent that it addressed natural resource concerns, has tended to focus on designing secured systems to provide specific resources or services, and thus, achieving “water security”, “energy security”, “food security” and the like. As a result national security and sustainable development have largely been treated separately by politicians and the public. When the connection between the two has been made around the notion of environmental security, it has tended to be with the assumption of complementarity or a common agenda between sustainable development goals and security goals. As such, with the exception of some of the literature highlighting the negative environmental impacts of war itself (e.g. Lanier-Graham Citation1993; Haavisto Citation2005), the real and sometimes substantial trade-offs between security objectives and other aspects of sustainable development have often been overlooked.

While there are many significant synergies between sustainable development and national security goals, the focus on them to the exclusion of discussion of potential trade-offs among them, is somewhat surprising. The effects of security concerns is largely lacking when one examines the literature covering the design, planning, location and maintenance of water and energy infrastructure designed to provide environmental services. Concepts such as infrastructure redundancy and supply diversification are critical for delivery of secure resources. Yet, inevitably they have an ecological footprint. But the academic literature on environmental security has largely overlooked such trade-offs, and is lagging behind real-world practices.

In this study, we analysed the security facets of the provision of wastewater treatment services in the Israeli–Palestinian context. The trade-offs identified in this case include economic trade-offs in which security concerns raise costs, thereby crowding-out other productive investments; equity trade-offs in which security concerns result in exposure of populations to environmental hazards or nuisances; and environmental trade-offs in which security concerns result in suboptimal pollution treatment and increased ecological footprints in terms of land and other resources consumed. Thus, while the particulars of the Israeli–Palestinian wastewater case may be specific to it, the nature of the trade-offs is, arguably, general, as similar trade-offs can be expected for other infrastructure services in other contexts.

The intensity and directionality of these trade-offs is not constant over time and space as they depend on a variety of contextual factors. In the Israeli–Palestinian wastewater case, peacebuilding efforts, outbreak of violence and the involvement of third parties were such factors. Such factors can either aggravate or mediate and even reconcile the aforementioned trade-offs. Yet, these supportive factors have to confront the institutional path dependency of treating environment and security as two separate themes. It was, and still is, the two-fold role of borders in perpetuating these security–sustainability trade-offs, as borders in our case functioned not only as political borders, but as environmental ones as well.

As the environment–security nexus is characterized by deep-seated contradictions, conflicts and tensions, a more holistic view of this nexus requires a somewhat broader functional definition of sustainability. It requires a definition that accepts security as an additional factor, or perhaps even pillar, in discussions of sustainability. Essentially, security, whether national or personal, should be seen as a prerequisite for sustainability, arguably equal in importance with efficiency, equity and environmental quality. This view of sustainability implies that it is insufficient to discuss and analyse the trade-offs between economic efficiency, equity and environmental quality in formulating policies. Rather, it is necessary to analyse the trade-offs between these pillars and security concerns as well. Once these trade-offs are recognized, a comprehensive approach may also deploy a variety of counter measures to reconcile the tension between security and sustainability, as was demonstrated in the case study explored. Yet, how to design institutions that foster cooperation between sustainable development and security concerns is left for future studies.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 For more on the constructivist approach to the security and the environment nexus, see Deudeny (Citation1990). For a discussion specifically in the context of water and security, see Fischhendler and Katz (Citation2013).

2 This notion has been advanced for the case of water where trade in food implies the ability to import “virtual water”, thereby reducing the need to utilize local scarce water for irrigation (Allan Citation2001).

3 On the importance of redundancy and its implications in a public administrative framework, see Landau’s (Citation1969) seminar article.

4 For example, concerns by native residents regarding the impacts of low flights on caribou have led to restraints on low flight training of the Canadian air force (Barker and Soyez Citation1994).

5 Some have claimed that the JWC is not a cooperative mechanism, but rather a means of extending Israeli hegemony (Zeitoun Citation2007) and even a colonializing mechanism (Selby Citation2013). This stems, at least in part from the fact that the West Bank is completely dependent on JWC decisions, while Israel is not, due to its access to other water sources such as the Sea of Galilee and other aquifers. In any case, by virtue of the PA’s veto power over Israeli actions in the West Bank, the body represents a move towards a more cooperative regime than existed previously.

6 Under the Oslo process, Israel collects the Palestinian custom taxes (on goods that come in on their way to the West Bank or Gaza). These revenues are to be transferred each month from the Israeli Ministry of Finance to the Palestinian Authority. Actual transfer of revenues was withheld by Israel upon assumption of control of the PA by Hamas in 2006, and only later resumed. Israel also deducts the costs of services rendered to the Palestinian population under an “offset mechanism” outlined in the Agreement.

7 The most noteworthy of these was the agreement between Tul Karem and the Emek Hefer regional council and the discussion regarding Jerusalem’s wastewater (Feitelson and Abdul Jaber Citation1997).

References

- Allan, T., 2001. The middle east water question: hydropolitics and the global economy. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Barker, M.L. and Soyez, D., 1994. The transnationalization of think locally Canadian resource-use conflicts act globally? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 36 (5), 12–36. doi:10.1080/00139157.1994.9929165

- Barnett, J., 2001. The meaning of environmental security. London: Zed Books.

- Bar-or, Y., 2006. Interview with Yeshua Bar-Or. Israeli Ministry for Environmental Protection, Chief Scientist. Jerusalem, 27 July 2006.

- Brandeis, A., 2001. Summary of meeting for the rehabilitation of the Alexander Stream, 2 January 2001.

- Brandeis, A., 2001b. Letter from Amos Brandeis to Rami Levi on an emergency solution to Nablus Stream. 4 March 2001.

- Brenner, S., 1998. Letter of Shmuel Brenner, Deputy Director of Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection to his Director, 12 January 1998.

- Caesari, M., 2007. Interview with Colonel Michal Caesari, Head of Administration and Services Branch between the years 1995–1999, Israeli Defense Force. Jerusalem. 16 May 2007.

- CNA, 2007. National security and the threat of climate change. Alexandria, VA: CNA Corporation.

- Collier, P. and Hoeffler, A., 2000. Greed and grievance in civil war. World Bank Policy Research Paper No. 2355. Washington, DC, World Bank.

- Conca, K, et al., 2005. Building peace through environmental cooperation. State of the world 2005. Redefining Global Security. W. Institute. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 144–157.

- Deudeny, D., 1990. Environment and security: muddled thinking. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 47 (3), 21–28.

- Diehl, P.F. and Gleditsch, N.P., eds., 2001. Environmental conflict. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Dycus, S., 1996. National defense and the environment. Hanover: University Press of New England.

- Eitan, M., 1998. Letter from Refael, Eitan, Ministry of Environmental Protection to Samuel Brener, Deputy Director of the Ministry of Environmental Protection. 18 November 1998. [in Hebrew].

- Farrell, A.E, et al., 2004. Energy infrastructure and security. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 29, 421–469. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102238

- Feitelson, E. and Abdul-Jaber, Q.H., 1997. Prospects for Israeli–Palestinian cooperation in wastewater treatment and re-use in the Jerusalem region. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies and the Palestinian Hydrology Group.

- Feitelson, E. and Haddad, M., 1998. A stepwise open-ended approach to the identification of joint management structures for shared aquifers. Water International, 23, 227–237. doi:10.1080/02508069808686776

- Feitelson, E. and Levy, N., 2006. The environmental aspects of reterritorialization: environmental facets of Israeli–Arab agreements. Political Geography, 25, 459–477. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.04.001

- Fischhendler, I., Dinar, S., and Katz, D., 2011. The politics of unilateral environmentalism: cooperation and conflict over water management along the Israeli–Palestinian border. Global Environmental Politics, 11 (1), 36–61.

- Fischhendler, I. and Katz, D., 2013. The use of ‘security’ jargon in sustainable development discourse: evidence from UN commission on sustainable development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 13, 321–342. doi:10.1007/s10784-012-9192-z

- FoEME (Friends of the Earth – Middle East), 2007. Website http://www.foeme.org, Accessed on 1 June 2013.

- Gleditsch, N.P., 1998. Armed conflict and the environment: a critique of the literature. Journal of Peace Research, 35 (3), 381–400. doi:10.1177/0022343398035003007

- Gleick, P., 1991. Environment and security: the clear connections. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, 47 (3), 17–21.

- Gvirtzman, H., 2002. Israeli water resources. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzchak Ben Tzvi press. In Hebrew.

- Gvirtzman, H., 2012. The Israeli–Palestinian water conflict: an Israeli perspective. Ramat Gan: The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Mideast Security and Policy Studies, No. 94.

- Haavisto, P., 2005. Environmental impacts of war. State of the world 2005: redefining global security. Worldwatch Institute. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 158–159.

- Haddad, M., Arlosoroff, S., and Feitelson, E., 2001. The management of shared aquifers: principles and challenges. In: E. Feitelson and M. Haddad, eds. Management of shared groundwater resources: the Israeli–Palestinian case with an international perspective. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

- Hareuveny, E., 2009. Foul play: neglect of wastewater treatment in the West Bank. B’Tselem. Available from https://www.btselem.org/download/200906_foul_play_eng.pdf [Accessed 20 April 2010].

- Herman, O., 2007. Interview with Colonel Oded Herman, Head of Infrastructure Davison, Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories between the years 1997–2005. Tel Aviv 17 May 2007.

- Homer-Dixon, T., 1994. Environmental scarcities and violent conflict: evidence from cases. International Security, 19 (1), 5–40. doi:10.2307/2539147

- Homer-Dixon, T., 1999. Environment, scarcity and violence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- JWC (Joint Water Committee), 2001. Minutes of the meeting of the Joint Water Committee held in the Erez DCL on 22 February 2001.

- Katz, D., 2011. Hydro-political hyperbole: incentives for over-emphasizing the risks of water wars. Global Environmental Politics, 11 (1), 12–35.

- Khagram, S. and Ali, S., 2006. Environment and security. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 31 (1), 395–411. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.31.042605.134901

- Klare, M.T., 2001. Resource wars: the new landscape of global conflict. New York: Holt.

- Landau, M., 1969. Redundancy, rationality and the problem of duplication and overlap. Public Administration Review, 29 (4), 346–358. doi:10.2307/973247

- Lanier-Graham, S. D., 1993. The ecology of war: environmental impacts of weaponry and modern warfare. New York: Walker.

- Le Billon, P., 2001. The political ecology of war: natural resources and armed conflicts. Political Geography, 20, 561–584. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00015-4

- Levy, M.A., 1995. Is the environment a national security issue? International Security, 20 (2), 35–62. doi:10.2307/2539228

- Meir, Y., 2004. Interior and Environmental Sub-Committee, Protocol of meeting on the Mountain aquifer pollution from sewage. 16 February [in Hebrew].

- Meital, O., 2007. Coordinating Officer for International Organization Branch of the Israeli Civil Administration. Personal communication. Bet-El.

- Ministry of Defense, 1999. Letter concerning the environment in Judea and Samaria. 4 August [in Hebrew].

- Ministry of National Infrastructures, 2002. Summary of discussion of the Israeli Technical Committee. 6 January [in Hebrew].

- Myers, N., 1989. Environment and security. Foreign Policy, 74, 23–41. doi:10.2307/1148850

- Myers, N., 1993. Ultimate security: the environmental basis of political stability. New York: Norton.

- Myers, N., 2005. Environmental security: what’s new and different? Institute for environmental security (IES) Working Papers. The Hague, Institute for Environmental Security (IES).

- Nagar, B., 2003. Letter from Baruch Nagar, Head of the Water and Sewage Administration in Judea, Samaria and Gaza of the Water Commissioner to Amos Gilad, and Daniel Risner, concerning illegal drillings. 29 January [Hebrew].

- Nagar, B., 2004. Interior and environmental sub-committee, Protocol of meeting on the Mountain aquifer pollution from sewage. 16 February [in Hebrew].

- Nagar, B., 2006. Summary of the JWC Technical Committee registered by Baruch Nagar, from the Israeli Water Authority. 27 April 2006. [in Hebrew].

- Newman, A., 2006. Interview conducted by Zak Tagar with Alvin Newman Head of the water and infrastructure desk, West Bank and Gaza Mission, USAID, Tel Aviv, 15 March 2006.

- Regev, Z., 2001. Letter from Zehev Regev, project coordinator to Erez Yemini, Israeli Ministry of Finance addressing the cost of wastewater treatment plants. 13 September 2001. [in Hebrew].

- Renner, M., 2002. The anatomy of resource wars. Worldwatch Paper No. 162. Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute.

- Renner, M., 2005. Security redefined. State of the world 2005: redefining global security. Worldwatch. Institute. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3–19.

- Selby, J., 2013. Cooperation, domination and colonisation: the Israeli–Palestinian joint water committee. Water Alternatives, 6 (1), 1–24.

- Shoam, Y., 2007. Interview Yoni Shoam, Emek Hefer Water Council, 12 April 2007.

- Starr, J., 1991. Water wars. Foreign Policy, 82, 17–36. doi:10.2307/1148639

- Swyngedouw, E., 2009a. The political economy and political ecology of the hydro-social cycle. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, 142 (1), 56–60. doi:10.1111/j.1936-704X.2009.00054.x

- Swyngedouw, E., 2009b. Troubled waters: the political economy of essential public services. In: J.E. Castro and L. Heller, eds. Water and sanitation services: public policy and management. London: Zed Books, 22–39.

- Tagar, Z., 2007. Water, Power, Institutions and Costs: cooperation and lack thereof in protecting shared Israeli–Palestinian water resources. M.A. Thesis, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Tal, A., 2002. Pollution in a promised land: an environmental history of Israel. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Tal, A. and Katz, D., 2012. Rehabilitating Israel’s Streams and Rivers. International Journal of River Basin Management, 10, 317–330. doi:10.1080/15715124.2012.727825

- Tal, S., 2007. Interview with Shimon Tal, former Israeli Water Commissioner. Tel Aviv, 24 June 2007.

- Trottier, J., 1999. Hydropolitics in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Jerusalem: Passia.

- UNCED (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development), 1992. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Retrieved 26 March 2014, from http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-1annex1.htm/

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 1994. Human development report—new dimensions of human security. New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2003. Desk study on the environment in the occupied Palestinian territories. United Nations convention on the non-navigational uses of international watercourses. In: Groundwater: legal and policy perspectives. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- UNROL (United Nations Rule of Law). 2004. The Secretary General’s High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges, and Change, A More Secured World: Our Shared Responsibility [online]. Available from http://unrol.org/doc.aspx?n=gaA.59.565_En.pdf [Accessed 26 March 2007].

- World Bank, 2009. Assessment of restrictions on Palestinian water sector development. Report No. 47657-Gz. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development), 1987. Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yakobovitz, 2007. Interview with Colonel Grish Yakobovitz, Head of Infrastructure Division, Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories. Tel Aviv, 29 April 2007.

- Zeitoun, M., 2007. The conflict vs. cooperation paradox: fighting over or sharing of Palestinian–Israeli groundwater? Water International, 32 (1), 105–120. doi:10.1080/02508060708691968

- Zorea, E., 2007. Interview with Eli Zorea, project manager at Mekorot, Israeli National Water Company. Israel, Lod, 17 May 2007.