ABSTRACT

In recent years there has been a surge in land investments, primarily in the African continent, but also in Asia and Latin America. This increase in land investment was driven by the food pricing crisis of 2007–2008. Land investors can be identified from a variety of sectors, with actors ranging from hedge funds to national companies. Many water-scarce countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are among these financiers, and primarily invest in Africa. Recognizing the potential for “outsourcing” their food security (and thereby also partly their water security), Middle Eastern countries such as Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have invested in land for food production in Africa. The extent to which this is happening is still unclear, as many contracts are not yet official and the extent of the leases is vague. This paper investigates the land investments and acquisitions by Middle Eastern countries. It also seeks to analyse what effect, if any, these investments can have on the potential for conflict reduction and subsequent peacebuilding in the Middle East region as the activity removes pressure from transboundary water resources.

EDITOR D. Koutsoyiannis ASSOCIATE EDITOR K. Aggestam

1 Introduction

Subsequent to the food prices crisis of 2007–2008, the world has seen increases in land investment in foreign countries for (mainly) productive purposes. The primary location of the majority of investments has been the African continent. This land acquisition trend was initially driven by increased food prices, but was also in response to growing water scarcity in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and elsewhere. A tangible result of this situation has been an increased interest from nation states, larger multi-national supermarket chains, as well as investment funds, in farmland purchases (Reardon et al. Citation2004, Gereffi et al. Citation2005). These actors include not only transnational agribusiness corporations from the developed world (which represent the traditional foreign direct investor in the agricultural sector), but also state-owned corporations and sovereign investment funds from emerging economies. Food security is an extremely salient issue, making investment in agricultural lands abroad an attractive solution (von Braun and Meinzen-Dick Citation2009), however most research has, so far, focused on the issue of land and rights while largely neglecting the issue of water (Jägerskog et al. Citation2012).

Earlier literature highlights the Middle East and North Africa as a region for water conflict and even war (see e.g. Starr Citation1991, Bulloch and Darwish Citation1993). However, substantive research shows that this has not been the case (see e.g. Wolf Citation1998, Allan Citation2002, Jägerskog Citation2003). While water has been (and still is) a source of conflict between and within states, it is not the precursor for war. Some of the main reasons for the initiation of war can be found by an analysis of the region’s political economy. A key example of this is the ameliorating effect played by “virtual water” in the region (Allan Citation1997, Citation2002, Citation2011). Researchers who identified approaching wars pointed to ongoing population growth as a reason, implying that less and less water per capita to live on, coupled with already tense relations over rivers such as the Jordan, the Euphrates-Tigris and the Nile, would lead to war. However, they did not analyse the trading patterns where virtual water was traded into the region in the form of food. Thus, the water deficit was managed through the importing of water-intensive foodstuffs at an accelerated pace by accessing the global food market (Allan Citation2002).

Today, there is decreasing trust in the global food market and many actors including states are choosing to invest in farmland for the production of food in places such as sub-Saharan Africa, South America and Southeast Asia (Deininger and Byerlee Citation2010, Anseeuw et al. Citation2012). The stability of food prices is intertwined with the political stability of a regime and further with national security (Brown Citation1977, p. 6, Swain Citation2012). Consequently, states’ active engagement in securing food production has been justified as a protective national security activity. Using the arguments put forward by Tony Allan—namely that the import of virtual water is a reason for reduced conflict—we investigate in this article a new aspect of this idea: that countries in the Middle East region are developing their “own” “virtual water” flows through land acquisitions.

We draw on the Land Matrix project’s database (www.landmatrix.org), the UN Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) statistics, as well as available data on virtual water trading within the region. The authors acknowledge that using secondary sources on such an aggregated scale can be problematic in terms of verification and accuracy of data. The majority of the data collected by the Land Matrix project are based on media reports which can be inflated and difficult to follow up. Despite the limitations, the database is the best available database that covers the global scale on land deals. Central questions asked are: To what extent do actual and planned investments in land represent, or potentially represent: part of the wider picture of virtual water trading? How much of investments are planned for import back into the investing countries? Can these amounts be considered significant? How much does this activity contribute to water and food security in the investing countries? Based on an understanding of the questions above, we analyse how this activity is contributing to improved security and peacebuilding in the Middle East.

2 Virtual water flows in the MENA region

The climate in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region ranges from semi-arid to arid.Footnote1 Populations are dependent on transboundary water sources and groundwater aquifers for their vital basic needs. Lack of rain and suitable agricultural land for rain-fed agriculture forces countries in the MENA region to concentrate on irrigated agriculture or importing food for consumptive purposes (de Fraiture et al. Citation2009). With the exception of Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, MENA is one of the most water-scarce regions globally. Renewable water availability is less than the 1000 m3/person per year threshold which determines water scarcity (Siddiqi and Anadon Citation2011, p. 4532). According to the FAO statistics, all countries in the Middle East are net importers of cereal. In 2010, volumes of imported cereal by MENA countries reached 79.885 106 t. This is a 26.1% increase from 2000, and counts as 23.8% of the total volume of cereals imported worldwide (FAO Citation2013). The volume of imported meat to the region has also increased from 1.258 106 t in 2000 to 3.222 106 t in 2010 (FAO Citation2013). Imported wheat, the main staple crop in the MENA region, is supplied from Australia, Canada, France, the USA and the Russian Federation. The largest MENA trade flows can be seen between France (exporter) and Algeria (importer) and between the Russian Federation (exporter) and Egypt (importer) (FAO Citation2013). International trades in crops and derived crop products are responsible for 76% of virtual water flows between countries (Hoekstra and Mekonnen Citation2012, p. 3233). Aggregated data of the MENA countries suggest that the consumption of agricultural products is responsible for 91.9% of internal water footprints and 97.3% of external water footprints.Footnote2

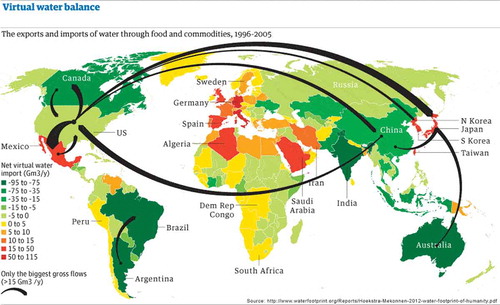

As shown in , most countries in the MENA region are net importers of virtual water through food and commodities. Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, the UAE and Yemen show extremely high external water dependency (). These countries are all located in an arid climate and experience severe freshwater water scarcity. Most of their water for food production is withdrawn from surface water and groundwater sources (blue water) as opposed to rainwater (green water). With the current international trade of food and agricultural commodities, countries in the MENA region have been able to import water indirectly. Consequently, virtual water trades have contributed to the mitigation of water security risks in the region (Allan Citation2002). However, this does not mitigate every risk. Apart from the insecurity of relying on the international trade regime for commodities, virtual water trading exposes countries to fluctuations in global food prices—one of the factors identified as an initiator in the Arab Spring revolutions in MENA countries (Lagi et al. Citation2011). Indeed, the trend of increasing prices of crucial agricultural commodities such as wheat and sugar poses great pressure on food importing countries. For example, between August 2003 and August 2013, the monthly price per metric tonne of wheat has increased from US$148.72 to 305.49. During the same period, the period of sugar increased from US$6.71 to 16.70 (World Bank Citation2013). These rises in imported food pricing point to an increase in cost for importing virtual water to the MENA, which threatens food security in the region.

Figure 1. Virtual water flows between nations (Hoekstra and Mekonnen Citation2012).

Table 1. Ratio of external/total water footprint of national consumption (%).

3 Land acquisitions by MENA region investors

The debate on achieving food security and food sovereignty in the MENA region is longstanding. Refuelled by the 2007–2008 food price spikes, some MENA governments strengthened or resumed their support of staple crop production, such as wheat cultivation in Egypt, Iran and the UAE (Ahmed et al. Citation2013). In 2013, the Abu Dhabi Food Control Authority of UAE conducted a feasibility study on large-scale wheat production in the country (Kader Citation2013, Malek Citation2013). The policy decision has a basis of excessive dependence on imported food in the UAE. The UAE’s cereal export has almost tripled from 502 000 106 t in 2000 to 1 477 000 t in 2010, while the imported volume steadily increased by 53% (FAO Citation2013). In opposition to this activity, Saudi Arabia’s strategy for food security focuses entirely on food imports and investment in farmland abroad. This is especially important after the reversal of Saudi policy to produce wheat in the desert (England and Blas Citation2008). Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have been primary investors in overseas farmland after the 2007–2008 food price spikes.

In 2010, wheat exports from Russia to Egypt reached US$858 730, the third largest in the world (FAO Citation2013, p. 153). In 2010, the Russian Government imposed a 5 month temporary ban on exports of wheat, barley, rye, corn, and wheat and rye flour due to fear of rising food and feed stock prices (Vassilieva and Smith Citation2010). This measure taken by Russia presented, and still presents, a risk to Egypt in relation to its food security. It is likely that this risk will have prompted discussion in Egypt of the increased need to assume control over the country’s food security status.

Because of socio-economic and political sensitivities associated with wheat supply and food prices, wheat is one of the most protected agricultural commodities in the MENA region. The government plays a crucial role in this protection throughout the global value chain (Ahmed et al. Citation2013).Footnote3 The challenges that occurred as a result of the food price spike affirmed the weakness of the countries in the MENA region, especially as the role of MENA countries in the international market is largely limited to consumer-based activities. When food commodity prices abruptly increased, this posed a significant economic burden to the countries in the MENA region. Understanding the new dynamics in the international market caused by the increase in food prices is crucial to placing rational agricultural policies in MENA countries. This understanding has prompted an increased interest on the part of the MENA countries to invest in land for food production.

According to the data drawn from the Land Matrix (Citation2013), Saudi Arabia has signed 19 deals with a total contract size of 1.489 million hectares (ha), and the UAE has signed 17 deals with a total contract size of 2.83 million ha. Both countries intend to grow mainly food crops (cereals including corn, rice and wheat), fruits and vegetables through these ventures. Only one contract is specifically earmarked for biofuel production through contract farming. This dataset collection clearly demonstrates the intention to use land for food production through new deals in foreign countries. The most prominent investment destination for the MENA investors is Ethiopia followed by Sudan and Egypt. Ethnic connections can also play an important role in the selection of MENA investment destinations. For example, the MIDROC Group of Saudi Arabia contracted six agreements with Ethiopia between 2007 and 2012 for growing a variety of food and cash crops (Land Matrix Citation2013).Footnote4 The company is well known for its prominent chairman, Sheikh Mohammed Al-Amoudi, an Ethiopian-born Saudi businessman who has been one of the primary investors in Ethiopia (Davidson Citation2012). During an interview with Forbes, Al-Amoudi stated that he tends to focus (his philanthropic work) in Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia and emphasized a special reference to Ethiopia in terms of developing cultural relationships (Serafin Citation2013). On the MIDROC website, Al-Amoudi further states, “When I invest in Ethiopia, my decisions to invest are based on what I feel in my heart for my motherland. All my other investment decisions in the rest of the world are based on calculated risks and benefits” (MIDROC Citation2009). In general, ethnic networks have been considered as one of the factors in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), e.g. ethnic Chinese networks and inward FDI in China (Gao Citation2003, Tong Citation2005).

The purpose of investment is two-fold. Some investors prioritize exporting back to the investor country, but other investment projects are mainly motivated by financial gains. No conclusive data indicate the exact amounts of food and agricultural commodities produced from land acquisitions, nor the percentage exported back to the MENA countries. However, media reports and statements by investors suggest that investors intend to export back to MENA in order to enhance food security. Al Dahra Agricultural Company of UAE, one of the investors in Pakistan and Sudan, states “the principal aim of this project [a project in Mipourkhas, city in Sindh district] was to grow alfalfa and Rhodes grass for export to the UAE” (Al Dahra Citation2013). Another example can be seen with the Abu Dhabi-based private company, Jenaan, who reported that 50% of their produce from Egypt is sold in the domestic market, while the remainder is sold to the Gulf region including the UAE (Bakr Citation2010). Saudi Star, a Saudi-based investment firm investing in Ethiopia, plans to export 45% of the produced rice mainly to Saudi Arabia and the rest to trade in the domestic market (Davison Citation2012). A Saudi investment project in Argentina by the Al-Khorayef Group established a concession on agricultural production that most of the production would be bought by Saudi businessmen under the Saudi Arabian National Food Security Plan, the initiative of King Abdullah (Piñeiro and Villarreal Citation2012, p. 6–7).

Generally, investments in land have become attractive to investors due to higher returns from agricultural commodity trading, rising prices of agricultural land, a diversification of investment portfolios and hedges against inflation (Schaffnit-Chatterjee Citation2012, cited in Auer et al. Citation2012). A representative of the Qatar National Food Security Programme referred to the Qatari investment made by the National Food Security Programme and stated that “these are pure investments for economic returns” (High Level Panel Citation2012). Due to the lack of freshwater and fertile land, many countries in the MENA region are restrained from producing the amount of food they require for food self-sufficiency (Allan Citation2002, Jägerskog Citation2003). After the 2007–2008 crisis, instead of entirely relying on the global agriculture trade for food supply, some countries in the region have been attempting to produce food from foreign farmlands. Indeed, judging from the increase in land investments since the crisis in 2007–2008, outsourcing as an element of food security policy has become a popular option. Leasing land for agricultural production enables more control over price hikes and less reliance on the global food market. Arguably this provides a sense of increased food security and a higher degree of control, something which is also important for the states in the MENA region. While they are, of course, still relying on global food regimes and international trade, the policy of investing in other countries can visibly decrease risk. Added to that is, of course, the improved water security the investing countries can enjoy (Jägerskog et al. Citation2012).

It is extremely hard to measure the amount of virtual water acquired through land acquisitions by MENA investors. This is due to land lease contracts often being unavailable, or that they regularly exclude provisions for water requirements. Quantifying the water acquisitions through land deals can be problematic if information on crop water requirements for the agricultural project is not fully provided. Weather parameters, crop characteristics, management and environmental aspects affect evapotranspiration by crops (Allen et al. Citation1998).Footnote5 Often, land deals are not reported with precise geographical information and that increases the risk on the accuracy in estimating water requirements for foreseen agricultural projects. In addition, factors such as accessibility to market, crop yield and national food export regulations are critical to the “exporting back” option for investors.

Implementation of agricultural investment projects can take a long time to complete. This is due to the need to satisfy detailed requirements for building infrastructures, irrigation facilities, roads and warehouses, and also the period for land reclamation. The slow implementation process delays empirical assessment of water acquisitions through large-scale land acquisitions. However, it is fair to say that the water component of land acquisitions is a significant portion. The countries are exerting their own control over their “virtual waters” through land investment in foreign countries.

4 The role of agribusiness transnational corporations (TNCs) in the virtual water trade

The international market for grain trading has been dominated by four transnational corporations (TNC), namely Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louise Dreyfus. Seventy to 90% of the most regular internationally traded staple food commodities are handled by these corporations. The dominance of these Western TNCs in the global food production system has been accepted as long as the food prices have been low (Sojamo et al. Citation2012, p. 175, 178). Murphy (Citation2008, p. 528) pointed out the “hour-glass” shape of the market (meaning that only a handful of processors and traders are in between many farmers and many customers at one time) is a failure of the agriculture commodity market. The volatile agricultural commodity market reflects factors such as weather events, speculations, slow response to demand and supply change, and rising costs for fertiliser and pesticides (OECD Citation2011).

It is not a new phenomenon that the major agribusiness TNCs operate abroad for both trading and production, but that “new investors” from non-Western countries and other sector TNCs have attempted to engage in agricultural production and trade in recent years (UNCTAD Citation2009).

Convergence between food and energy business sectors can be found in the examples that the energy TNCs initiated investment in agricultural commodities, and agribusiness TNCs began to increase the share of biofuel and chemical production in their portfolios (Gordon Citation2008, Murphy et al. Citation2012). In particular, public subsidies on biofuel production have been a great incentive for biofuel producers (Matondi et al. Citation2011). Although the contribution of biofuel production to the world food prices spike in 2007–2008 was not as significant as it was discussed (Mitchell Citation2008, Ajanovic Citation2011, Mueller et al. Citation2011), the sustainability of biofuel production and the increasing trend of governmental support can cause the trade-off between food and fuel.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The fundamental question in this article has been: To what extent do virtual water trading and land acquisitions contribute to food and water security in investing MENA countries? After analysing the situation, there is evidence that investment in farmland abroad as a source for food and water security, as a strategy, has partly been in order to address risks emanating from the global food market, as evidenced during the food price crisis in 2007–2008. During that period, some countries—for fear of soaring prices of, for example, wheat in their home countries—put a cap on exports. A telling example is how Russia temporarily banned exports of wheat to Egypt. This presented Egypt with a significant challenge due to a reliance on wheat from Russia. With increasing volatility in markets it is clear that countries are re-assessing their strategies to minimize food security risks. Increasing land acquisition for the production of food in other countries is one risk-reduction strategy. This comes with the additional benefit in that countries can also harness control of virtual water flows being traded back, certainly more than they would in the case of relying on the global food market.

It seems also clear that countries and companies in the MENA region invest not only to minimize risk to their food and water security, but also as a business opportunity. As noted by a representative from the Qatari National Food Security Programme, there are untapped business opportunities to be capitalized upon.

Another key question in this paper is whether the increased land acquisitions by MENA countries serve to reduce regional conflict over water. Water was first considered to be a source of conflict and even war in the MENA region. However, it was subsequently proved to be a source of cooperation and that the increased water scarcity was driven primarily by population growth. In addition, it was noted by Allan (Citation2002) that the import of virtual water was an ameliorating factor that decreased the propensity for conflicts and wars. One hypothesis as to why MENA countries would invest in land for food production (and biofuels) could be that there is scope for decreasing water conflicts over land and water in their home countries as well as between countries in the region with high water dependency—i.e. high proportion of reliance on transboundary waters.

It also seems from the evidence that a number of the investments have been made as a way of increasing diversification and reducing risk by not relying only on the global food market and the virtual water hegemons (Sojamo et al. Citation2012). While land investments in the African continent by MENA investors clearly assist them in accessing both land and water and thereby food, it is yet too early to draw definite conclusions as to whether this can lead to a decrease in conflict over water at home or between countries in the MENA region sharing water bodies. More reliable datasets (problems with the current datasets are noted) as well as more in-depth research are needed to more firmly establish the links. While investments in land abroad decrease the risk of relying on the global food market for supply of staple foods—and thereby make investing countries less vulnerable to volatile food markets—the data at hand make it hard to evaluate the significance of the trade coming from the investments at present in relation to the virtual water they are accessing in the global food market. This is partly due to (i) the secrecy surrounding many of the land deals, (ii) that many of the deals are silent on the water requirements, and (iii) the poor quality of some of the data used for the datasets.

Thus, while it may serve to reduce conflict, it is not possible to draw these conclusions at present. However, if more data became available, it would be possible to analyse the issue further.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) for providing financial support through U-forsk (support for Swedish research relevant to low- and middle- income countries) for the research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article, the MENA region includes Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, West Bank and Gaza, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemen.

2 Calculation based on the dataset from Mekonnen and Hoekstra (Citation2011), Appendix VIII. Bahrain, Iraq, Libya, Oman and Qatar are excluded due to the data availability.

3 Here, the “Global Value Chain” of wheat includes providing inputs, production, processing and marketing, as well as trading commodity, either with trading companies or with offshore production facilities (based on Ahmed et al. Citation2013, p.10).

4 Cash crops are grown primarily for marketing rather than for household consumption (definition based on Hill and Vigneri Citation2011).

5 Evapotranspiration represents the combination of evaporative losses from the soil surface and transpiration from the plant surface. The two phenomena occur simultaneously and distinguishing between them is difficult. (The definition based on Allen et al. Citation1998.)

References

- Ahmed, G., et al., 2013. Wheat value chains and food security in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Durham: Duke University, Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitiveness.

- Ajanovic, A., 2011. Biofuels versus food production: does biofuels production increase food prices? Energy, 36 (4), 2070–2076. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.05.019

- Al Dahra, 2013. Al Dahra, Pakistan [online]. Al Dahra Agriculture. Available from: http://aldahra.com/aldahra-pakistan.html [ Accessed 24 September 2013].

- Allan, J.A., 1997. Virtual water: a long term solution for water short Middle Eastern economies? In: Paper presented at the 1997 British Association Festival of Science, 9 September, Leeds.

- Allan, J.A., 2002. Virtual water eliminates water wars? a case study from the Middle East. In: Proceedings of the international expert meeting on virtual water trade, 12–13 December 2002. Delft: UNESCO-IHE.

- Allan, J.A., 2011. Virtual water: tackling the threat to our planet’s most precious resource. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Allen, R.G., et al., 1998. Crop evapotranspiration: guidelines for computing crop water requirements. Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Rome: FAO.

- Anseeuw, W., et al., 2012. Transnational land deals for agriculture in the global south. Analytical report based on the Land Matrix Database [online]. The Land Matrix Partnership. Available from: http://landportal.info/landmatrix/media/img/analyticalreport.pdf.[ Accessed 8 April 2014].

- Auer, J., et al., 2012. Real assets: a sought-after investment class in times of crisis. Deutsche Bank Research. June 2012. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bank.

- Bakr, A., 2010. UAE firm focuses on developing farmland abroad [online]. Reuter. Available from: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2010/11/24/idUKLDE6AN1VB20101124 [ Accessed 24 September 2013].

- Brown, L.R., 1977. Redefining national security. Worldwatch Paper 14. Washington, DC: World Watch Institute.

- Bulloch, J. and Darwish, A., 1993. Water wars: coming conflicts in the Middle East. London: St Dedmundsbury Press.

- Davison, W., 2012. Saudi Star offers jobs to overcome criticism of Ethiopia Project [online]. Bloomberg News, 30 May. Available from: http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-05-30/saudi-star-offers-jobs-to-overcome-criticism-of-ethiopia-project [ Accessed 24 September 2013].

- de Fraiture, C., et al., 2009. Can rainfed agriculture feed the world?: an assessment of potentials and risk. In: S.P. Wani, J. Rockstrom and T. Oweis, eds. Rainfed agriculture: unlocking the potential. Columbo: International Water Management Institute.

- Deininger, K. and Byerlee, D., 2010. Rising global interest in farmland. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- England, A. and Blas, J., 2008, Water fears lead Saudis to end grain output. Financial Times. February 27.

- FAO, 2013. Statistics yearbook. Rome: FAO.

- Gao, T., 2003. Ethnic Chinese networks and international investment: evidence from inward FDI in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 14 (4), 611–629. doi:10.1016/S1049-0078(03)00098-8

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., and Sturgeon, T., 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12 (1), 78–104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805

- Gordon, G., 2008. The global free market in biofuels. Development, 51 (4), 481–487. doi:10.1057/dev.2008.52

- High Level Panel, 2012. High Level Panel session during the World Water Week 2012 [online]. Available from: http://www.worldwaterweek.org/sa/node.asp?node=1610 [ Accessed 23 September 2013].

- Hill, R.V. and Vigneri, M., 2011. Mainstreaming gender sensitivity in cash crop market supply chains. ESA Working Paper No. 11-08. Rome: FAO.

- Hoekstra, A.Y. and Mekonnen, M.M., 2012. The water footprint of humanity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (9), 3232–3237. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109936109

- Jägerskog, A., 2003. Why states cooperate over shared water: the water negotiations in the Jordan River Basin. Thesis (PhD). Linköping University, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science.

- Jägerskog, A., et al., 2012. Land acquisitions: how will they impact transboundary waters? Report no. 30. Stockholm: SIWI.

- Kader, B.A., 2013. Abu Dhabi explores wheat cultivation in the emirate [online]. Gulf News. Available from: http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/uae/environment/abu-dhabi-explores-wheat-cultivation-in-the-emirate-1.1136891 [ Accessed 16 September 2013].

- Lagi, M., Bertrand, K.Z., and Bar-Yam, Y., 2011. The food crises and political instability in North Africa and the Middle East. Working Paper Series. Cambridge: New England Complex Systems Institute.

- Land Matrix, 2013. Land Matrix Database [online]. Available from: http://www.landmatrix.org/ [ Accessed 24 September 2013].

- Malek, C., 2013. Wheat flour could soon be produced in the UAE [online]. The National. Available from: http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/wheat-flour-could-soon-be-produced-in-the-uae#ixzz2f4KeuLHP [ Accessed 16 September 2013].

- Matondi, P.B., Havnevik, K., and Beyene, A., 2011. Conclusion: land grabbing, smallholder farmers and the meaning of agro-investor-driven agrarian change in Africa. In: P.B. Matondi, K. Havnevik, and A. Beyene, eds. Biofuels, land grabbing and security in Africa. London: Zed Books.

- Mekonnen, M.M. and Hoekstra, A.Y., 2011. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 15 (5), 1577–1600. doi:10.5194/hess-15-1577-2011

- MIDROC, 2009. About Us: Sheikh Mohammed H. Al-Amoudi’s Investment in Ethiopia [Online]. Addis Ababa: MIDROC Ethiopia. Available at: http://www.midroc-ethiopia.com.et/md01_aboutus.html#top [ Accessed 30 September 2013].

- Mitchell, D.A., 2008. Note on rising food prices. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Mueller, S.A., Anderson, J.E., and Wallington, T.J., 2011. Impact of biofuel production and other supply and demand factors on food price increases in 2008. Biomass and Bioenergy, 35 (5), 1623–1632. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.01.030

- Murphy, S., 2008. Globalization and corporate concentration in the food and agriculture sector. Development, 51 (4), 527–533. doi:10.1057/dev.2008.57

- Murphy, S., Burch, D., and Clapp, J., 2012. Cereal secrets: the world’s largest grain traders and global agriculture. London: OXFAM.

- OECD, 2011. Price volatility in food and agricultural markets: policy responses. Paris: OECD; Rome: FAO.

- Piñeiro, M. and Villarreal, M., 2012. Foreign investment in agriculture in MERCOSUR member countries. Winnipeg, MB: International Institute for Sustainable Development.

- Reardon, T., Timmer, P., and Berdegue, J., 2004. The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: induced organizational, institutional, and technological change. Agrifood Systems, 1, 168–183.

- Schaffnit-Chatterjee, C., 2012. Foreign investment in farmland: no low-hanging fruit. Deutsche Bank Research. November 13. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bank.

- Serafin, T., 2013. Sheikh Mohammed Al Amoudi on philanthropy [online]. Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/tatianaserafin/2013/06/05/sheikh-mohammed-al-amoudi-on-philanthropy/ [ Accessed 30 September 2014].

- Siddiqi, A. and Anadon, L.D., 2011. The water–energy nexus in Middle East and North Africa. Energy Policy, 39 (8), 4529–4540. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.04.023

- Sojamo, S., et al., 2012. Virtual water hegemony: the role of agribusiness in global water governance. Water International, 37 (2), 169–182. doi:10.1080/02508060.2012.662734

- Starr, J.R., 1991. Water wars. Foreign Policy, 82, 17–36.

- Swain, A., 2012. Understanding emerging security challenges: threats and opportunities. London: Routledge.

- Tong, S.Y., 2005. Ethnic networks in FDI and the impact of institutional development. Review of Development Economics, 9 (4), 563–580. doi:10.1111/rode.2005.9.issue-4

- UNCTAD, 2009. World investment report: transnational corporations, agricultural production and development. New York: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

- Vassilieva, Y. and Smith, M.E., 2010. Ban on grain exports from Russia comes to force on August 15. GAIN Report Number: RS1039. Moscow: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

- von Braun, J. and Meinzen-Dick, R., 2009. “Land Grabbing” by foreign investors in developing countries: risks and opportunities. IFPRI Policy Brief 13. April 2009. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

- Wolf, A., 1998. Conflict and cooperation along international waterways. Water Policy, 1 (2), 251–265. doi:10.1016/S1366-7017(98)00019-1

- World Bank, 2013. World Bank Data Bank: GEM Commodities [online]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/commodity-price-data [ Accessed 19 September 2013].