Abstract

On the eve of my retirement as co-editor of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS) and Hydrological Sciences Journal (HSJ), I would like to take the opportunity to address the HSJ audience with some reflections about the journal and the publishing system.

1 EIGHTEEN YEARS ON THE ROAD

In the mid-1990s I was approached by John Rodda, the then IAHS President, asking whether I would be interested and available to assume the duty of editor of the IAHS’s periodical, Hydrological Sciences Journal (HSJ). The conversation with John took place when I was an HSJ associate editor (1991–1996). I felt flattered by this challenging proposal and agreed. During the IAHS Scientific Assembly in Rabat in April 1997, I formally assumed this new duty, after being thoroughly briefed by the outgoing Editor, Terence O’Donnell.

I did not really imagine then that my career as HSJ editor would last 18 years, longer than the tenure of any previous editor of the journal (initially this role was part of the IAHS Secretary General’s tasks): L.J. Tison (1956–1960), followed by Gérard Tison (1961–1971), John Rodda (1972–1979), Robin T. Clarke (1980–1983) and Terence O’Donnell (1983–1997).

On assuming the duty of editor, I knew that the journal of the IAHS (formerly the International Association of Scientific Hydrology, IASH) had a long tradition: established in 1956, it is indeed the oldest hydrological journal worldwide. It has changed its name from the International Association of Scientific Hydrology Bulletin (1956–1971) to Hydrological Sciences Bulletin (1972–1981) and, finally, to Hydrological Sciences Journal (since 1982). The journal has indeed come a long way since its beginning. The first issue (1/1956) of the IASH Bulletin contained mostly newsletter-type material, devoted to organizational matters and a section, small to begin with, devoted to scientific articles. In response to numerous requests sent out by L.J. Tison, one “first-class” scientific article arrived that was proudly included in the first issue. Old issues (including 1/1956) are available on the Internet (see www.tandfonline.com/thsj).

During my term as editor, I have witnessed dramatic changes in the journal and in the publishing environment. My predecessor, Terence O’Donnell did not always have sufficient material to fill the planned number of journal pages. In contrast, during recent years, the number of submissions has rocketed, reaching 571 new papers in 2014, so now some two-thirds of submitted papers are rejected.

When I started my editorial duties in 1997, the journal was bi-monthly (since 1988; from 1956 to 1987 it was quarterly). The frequency increased again in 2010 to eight issues a year and, since 2014, HSJ has been published monthly. The number of editors (one since 1956) grew to two in 2006, and now—since May 2014—three.

There have been several recurrent themes during my time as editor. I remember discussion of the possibility of granting open access (OA) to HSJ (at the Sapporo assembly in 2003), but it was clearly too early for such a bold move (yet, EGU made such a decision on Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (HESS) and won an advantageous position in the hydrological journals space). The Association considered two financing models: readers pay (classical subscription model), or authors pay (emerging OA model), and it was decided to maintain the former arrangement. Given the importance of HSJ to financing IAHS (a non-membership fee organization), it was found too risky to attempt the transition at that stage.

I started my editorial career at a time when postal services dominated. There were paper files for every submitted contribution and all the HSJ material (papers, reviews, decision letters) was printed and sent by post. I remember queues in post offices. To save my time there I bought a letter scale and quickly learned the foreign part of the Polish post tariff by heart. Although Frances Watkins (Technical Editor) in the IAHS Press office in Wallingford and I were extensively using the Internet by that time, some of our authors were not, so that using “snail-mail” was a must. Gradually, we went electronic—the material was e-mailed and processed without printing. It could well be that, some time in the future, even the HSJ will not be printed and, indeed, online dissemination will do. Also, progress in bibliometry (see Section 3) has been an important element of the changing publishing landscape that I have noticed during my term.

In my early days as editor, I used to read everything that was published and tried to correct any problems, including the typos, I could spot. This was quite old-fashioned, and not maintainable in the light of the massive growth of the journal.

2 LESSONS LEARNT

An odd section title, perhaps? A retiring editor will have no opportunity to implement changes resulting from lessons learnt. However, this may still be of use to my successors.

While running the journal, I recognized the process dynamics, linking input, output and the state of the system. In the language of queueing theory, I dealt with an input stream of submitted papers, with quantity and quality characteristics, and an output stream of published papers (also with quantity and quality characteristics). Quantity measures are straightforward, while the quality measures perhaps less so. The quantity measures could refer to numbers of papers submitted, rejected, accepted and published in the time interval of concern (typically a year). The input quality characteristics could refer to the quality of the stream of submitted and revised drafts as evaluated by referees. They rate a paper using three categories: poor to fair, good, very good to excellent, and they issue recommendations, ranging from “reject outright” through a number of intermediate categories such as: “reject and resubmit”, “major revision”, “minor revision” to “accept apart from editorial changes”. The measures for the output stream include: the number of downloads, the number of citations (e.g. via bibliographic indices, as discussed in the next section) and statistics related to processing a submitted paper (rejection rate, acceptance rate, process duration indices: mean time from submission to review, from acceptance to publication online, and from publication online to printing the final version), as well as economic results (total income vs costs, number of paying subscribers). A systemic view identifies actors/players: audience/readership, authors, editors, technical/copy editors, associate editors, referees, patron scientific organizations and commercial publishers. The regularities of the dynamics of the publishing system can be recognized and guidelines for relevant actions can be formulated. There is a risk that if the number of issues grows, the standard may fall. Publication of many special issues, solicited by IAHS commissions and individual scientists, can potentially add to the attractiveness of the journal (and might contribute to the citation index—the impact factor, IF, cf. Koutsoyiannis and Kundzewicz Citation2007), but it shifts the accepted papers that are due to be published in regular issues into a queue. A backlog can grow and the waiting time may become unacceptably long.

It is crystal clear that in the single-objective setting, if only the IF counts and should be boosted (see Section 3), the HSJ editors have to do one or more of the following:

reject outright any papers that are unlikely to attract citations (in fact, rejecting more papers would serve the journal well also for other reasons, as it would reduce the unacceptably long queue of accepted papers);

change the bilingual English/French policy to English-only (papers in French receive few citations);

attract star papers that are likely to catch many citations in the first two years after publication (and publish such star papers, if possible, in the first issue in a year, so that they have a long run-up and are available for the longest possible time in the publication year, N, improving their visibility and chance of being cited in years N + 1 and N + 2, i.e. the period that counts for the IF); and

increase the visibility of HSJ papers by any possible means, one being promoting access to more papers.

Star papers that attract numerous fast citations do happen in HSJ (for recent examples, see: Montanari et al. Citation2013, Hrachowitz et al. Citation2013), but are rather rare. Most papers published in HSJ attract no citations in the IF time window of two years. This is not a surprise to editors, who can forecast the likely dynamics of citations of a submitted paper and reliably foresee that a paper is unlikely to be cited. The same may also hold for some fine papers that appeal to a narrow readership in a niche area where not much is being published. Should the policy of rejecting papers that are unlikely to fetch citations in the first two years after the publication year be followed? How to communicate such a verdict?

The way in which the impact factor is determined gives an advantage to open-access journals (where authors pay for processing the contribution and for publication, while readers get access for free). Only the first two years after publication count for the IF, while for the great majority of HSJ papers (except for those whose authors pay the open-access, OA, fee), free access is granted only after two years––too late for the IF). In comparison to HESS (a fully open-access journal) the structural disadvantages of HSJ are: no free open access and publication of French-language papers whose audience is smaller. By paying for open access, one can acquire additional visibility and citations, but at present the price is high and unaffordable to most authors. However, several funding agencies increasingly insist on open access publishing and accept a budget line in project proposals to this effect. This may become commonplace in future.

However, the IF has not been the only objective that mattered in HSJ (cf. Cudennec and Hubert Citation2008). Traditionally the IAHS journal served multiple objectives, one of them being to provide an avenue for publication for hydrologists from the developing world. A long-lasting tradition of the Association has been to serve authors from developing countries by assisting them to improve their contributions and perhaps placing a little less rigid acceptance thresholds. Critical and constructive reviews can be extremely useful, and even more so for authors from developing countries. At times, when comparing the submitted first draft and the accepted paper, one can note a huge improvement, bringing satisfaction to all—authors, reviewers, editors and the readership at large.

If I know what to do to boost the IF, why didn’t I do this myself? Well, I have seen my role in a multi-objective setting and wanted to avoid revolutionary action. I am afraid of revolutions that destroy in order to build something different (as it turns out, not necessarily better). I do strongly prefer evolutionary development, instead.

3 UNDER THE DICTATORSHIP OF BIBLIOMETRIC INDICES

During my 18 years as editor, I have observed a strong growth in the importance of bibliometric indices. Today, they are essential in the evaluation of a scientist, or group of scientists. Such indices are used to back decisions on employment, promotion, pay rises, or funding a project. In Poland, the ranking list of journals compiled in the ISI/Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports (JCR), according to the value of their IF, is processed every year to produce the official list of credit points for publication, issued annually by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

When bibliometric indices were not as important, I did not pay attention to the JCR list and was keen to publish books as well as articles in “obscure” journals, with the same enthusiasm as publishing in high-impact periodicals. Now, like many HSJ readers, I visit the Web of Science website of ISI/Thomson Reuters that evaluates the bibliometric indices of each scientist publishing in journals included in the JCR. For a discussion of the application of bibliometric indices in hydrological sciences, see Koutsoyiannis and Kundzewicz (Citation2007). shows the seven numbers summarizing my achievements, after Web of Science, as of 13 March 2015.

Table 1 Bibliometric summary of Z.W. Kundzewicz. Data source: Web of Science, 13 March 2015.

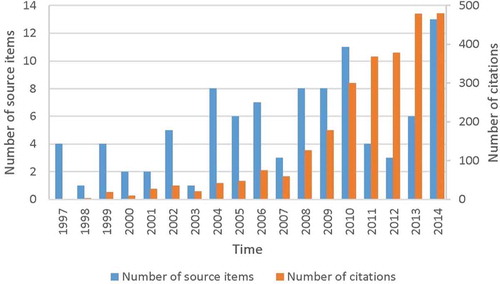

As illustrated in , I (co-)authored 126 papers in journals included in the JCR. There is considerable inter-annual variability in the number of papers (), while the numbers of citations show a clearly increasing tendency. Part of this growth can be explained by the fact that the journal database of ISI has been gradually extended. If a new title is included, earlier volumes of this journal enrich the database. Apparently, some journals try to “artificially” increase their IF by advising authors of papers under review to cite papers from this Journal.

Fig. 1 Number of papers (co-)authored by Z.W. Kundzewicz during his term as HSJ editor or co-editor (1997–2014), in journals included in JCR, and number of citations to these papers. Data source: Web of Science, 13 March 2015.

Evaluating an individual in seven dimensions () is not practical; hence, the question arises: how does one scalarize the bibliometric summary and achieve a one-dimensional index? What should count more: a sum of source items, a sum of times cited, an h-index, or perhaps a combination of these?

For pragmatic reasons, scalarization could be advantageous, but in fact one can invent many more bibliometric indices (new concepts or mutations of indices), and indeed some of them have been occasionally envisaged and used in various environments (institutions, countries). One option is to look at the number of publications with citations in excess of some threshold, such as 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 (also 1000 and 10 000 for “giants”). In my case: C500 = 1 (one co-authored publication with the number of citations in excess of 500), C100 = 4, C50 = 10, C20 = 33, C10 = 50 (after Web of Science of ISI/Thomson Reuters).

In some evaluations (e.g. at the national level), sums of IFs of all journals where papers were published count. Then, a single paper in Science or Nature may bring as many “credit points” as 20 or even 50 papers published in less prestigious, lower-impact, journals from the Web of Science.

includes the h-index (Hirsch Citation2005)—a simple concept that has made a fascinating recent career. The h-index rewards many highly-cited papers rather than a non-uniform distribution with a single star paper and a much less cited remainder. The h-index cannot decrease in time (except for the rare cases of retraction of publications after proving fraudulent, see Section 5). It may grow in time, even after the death of the author (then such growth does not include self-citations). Since the concept has attracted a lot of interest, there are many modifications and variants of the index, e.g. giving more weight to highly-cited papers, or restricting the time window to more recent times. What we have done in the more recent past, e.g. the last five or 10 years, is indeed more important than earlier achievements, and the career length should be also reflected (Alonso et al. Citation2009). However, by proposing modifications to the h-index (cf. Kierzek Citation2013), one may wish to find (and promote) a classification where one’s position is better. This can be a vehicle for manipulation.

While the IF has become the principal index to evaluate journals, the h-index has unquestionably reached the position of the prime index to evaluate scientists.

How can an individual boost her or his bibliographic indices? Publishing citable papers is key. Citability depends on the quality of the science and the findings, their novelty and originality and the likely interest they may raise. The probability of success can be increased by the choice of an important and attractive topic, and a catchy title. Dissemination and visibility can be increased by attending conferences and presenting material published in journal articles, thus publicizing them. Often the order is reversed: first a conference presentation and then a paper.

The “publish or perish” rule is now cast in stone; however, a variant “publish as high as possible” (i.e. not higher and not lower) is increasingly implemented. Publications and citations are the core of performance indicators—currencies for evaluating scientific activities at any level (from individuals to groups, institutions, countries, continents or even the globe, if you will). It is pragmatic to strive for optimal selection of a publication outlet: aiming too high incurs the risk of a paper being rejected without review—a virtually useless experience, because no constructive comments are received that could allow one to improve the paper. The only benefit is finding out that the paper will not “fly” in that particular journal. In contrast, if a paper is accepted smoothly and quickly, it may seem a missed opportunity (one could have aimed higher), unless a journal is selected for reasons different from bibliometry (e.g. time is the principal constraint—fast acceptance is needed). One may doubt, however, whether making bibliometry-based projections, calculations and optimizations is a healthy (even if pragmatic) symptom of the present era.

Some scientists feel that bibliographic indices are a poor proxy for quality—a kind of vanity fair. One weakness is that an erroneous paper may raise interest and many critical citations; the tenor of a citation—whether it expresses criticism or applause—cannot be distinguished. A cynic may say that, these days, publications are not to be read, they are to be cited, to boost authors’ careers. Yet, I always ran the journal with the hope that what we publish in HSJ will be read.

Bibliographic indices should be considered from an area-specific perspective: in the hydrological sciences, the values of indices are far behind those in the life sciences or physics. For example, in the life sciences, one author (S.H. Snyder) has an h-index of 208, and in physics, another (E. Witten) achieved 131. Some individual papers attract a huge number of citations—a single paper published in Analytical Biochemistry in 1987 (by P. Chomczynski, a Polish record-holder) fetched 61 447 citations. This is far above the hydrological records.

At this point I wish to greet Keith Beven, the record holder in the hydrological sciences, as measured by bibliometric indices, whose 275 papers published in ISI-rated journals have been cited 19 116 times. Keith’s respectable Hirsch index is 65. Chapeau bas!

In many countries, the ISI/Thomson Reuters resources, such as Web of Science and Journal Citation Reports, are a standard. However, there exist other, important bibliometric databases, such as Scopus and Google Scholar (Koutsoyiannis and Kundzewicz Citation2007). The latter, free-access, database includes the largest set of source items, far beyond the ISI-rated journals. Some important publications in the hydrological sciences, such as the IPCC Technical Paper on Climate Change and Water (Bates et al. Citation2008) co-edited and co-authored by myself, have fetched many citations, as can be seen in Google Scholar (2204 citations as of 13 March 2015). This work was published in all six official languages of the United Nations (), so the real number of citations must be higher, as Google Scholar may not include many source items in non-Latin alphabets. Moreover, there are citations to my name with typographic errors (of several different types) that do not count for me (they would count for a non-existent person). One can calculate h-index based on Scopus or Google Scholar ratings as well.

Fig. 2 Front covers of the different language versions of the IPCC Technical Paper on Climate Change and Water (Bates et al. Citation2008) that has fetched many citations, according to Google Scholar, yet is ignored in the Web of Science.

4 PLAYING COACH

I fulfilled my role as HSJ editor analogously to a playing coach in sports—one who coaches the team, but also plays in the team, if this is advantageous for the result. I used HSJ as an outlet for several citable papers I had authored or co-authored, rather than trying to submit to other journals even with slightly higher bibliometric indices.

I did not see the situation of an editor publishing in “her” or “his” journal as the manifestation of a conflict of interests. Rather, it is seeking co-benefits and “win-win” situations. In fact, this happens in other journals, where editorials (included in the Web of Science database) and papers (co-)authored by editors are more the norm than the exception. However, for the evaluation of my achievements in the process of reviewing my Polish grant proposal, being an HSJ editor was a disadvantage. A tacit assumption was made by an anonymous referee that it is “my” journal, so I can publish what I want and then possibly generate and control citations. I found this disappointing and saddening, since, in reality, my HSJ papers that are frequently downloaded and cited had been dealt with by another co-editor and had quite a difficult path to acceptance, being considerably improved by taking account of the remarks of very critical referees. For instance, the reviews of the paper by Kundzewicz et al. (Citation2014) were tough, and quite an effort was necessary to have this paper revised before it was accepted.

Actually, more than half of my “best” papers (in the top 10, 20, 30 of the citability table) were published in HSJ. Since the h-index has a variety of applications, it can also rank my entries to HSJ: thus the value of my h-index in HSJ is 18, i.e. my 18th most cited paper published in HSJ has been cited 18 times ().

Table 2 Most cited HSJ papers (co-)authored by Kundzewicz (ZWK), in order of number of citations (source: Web of Science, 13 March 2015). The papers shown contribute to the ZWK-in-HSJ h-index. In brackets, the position on the list of all ZWK publications is shown, organized by citation number.

The years with maximum number of citations (in the examples given in —years 6–7, 8 and 9) come long after the IF horizon (i.e. years 2 and 3). Citations in the first year(s) are often self-citations.

Table 3 Dynamics of citations: time series of top three best cited HSJ papers by Kundzewicz. Year no. 1: year of publication. Bold values show those that count for the IF. Citations in 2015 are not included.

I am very glad that a flood paper resulting from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) special report on extremes (Kundzewicz et al. 2014) is now second on the list of the most read HSJ papers (amazing, in view of such a short life-time). It had 9776 views and eight citations by 13 March 2015, and may count toward the ZWK-in-HSJ h-index (cf. ) relatively soon. It is likely to be well-cited in its IF time window and to contribute to the journal’s IF for 2015 and 2016 (to be determined in 2016 and 2017, respectively). The HSJ paper with the most views has been another IPCC-based product, by Kundzewicz et al. (Citation2008), reporting on the findings of the chapter on freshwater resources and their management in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (Working Group II) with 10 896 views (and 169 citations). It is fair to state that both these papers (Kundzewicz et al. Citation2008, Citation2014) were open-access contributions, so that they may be read online at no cost.

5 EDITORIAL NIGHTMARES

I have been lucky not to witness extreme editorial nightmares related to the materialization of instability, when a journal moves towards perdition. However, I can easily imagine the fatal case of a journal going down—subscriptions falling, the IF value diving, and the submission stream drying out. In contrast, when I started, the number of submissions was low and the IF ranged from 0.3 to 0.4. This has greatly improved since the commencement of my term (also due to the general growth of importance of bibliometric indices).

I am aware of the possibility of having made editorial errors of the first kind (rejecting papers that should have been accepted) as well as errors of the second kind (accepting papers that should have been rejected). However, the matter of identification of editorial errors is not straightforward. Sometimes a paper that should be rejected outright is much improved after revision(s) and finally is published and well cited, so that the initial mercy brings reward.

The gallery of editorial nightmares includes the risk of overlooking fraud. Fortunately, HSJ has not been involved in any spectacular affairs. Pathologies of the research and publication process, such as publishing fabricated results, or emergence of an “organized” (fake) review, showed up in other journals. In such cases, the punishment included retraction of published papers, so that papers became unpapers—by analogy to the concept of “unperson” from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four—a person who has been “vaporized” (including being erased from printed memory).

At times, the editor’s job has been quite difficult and frustrating. I found myself in an uncomfortable position, placed “between a hammer and an anvil”, having to make a decision, respecting different views, and knowing that at least one of the parties would not like it, no matter what it would be. I tried to be humble, to listen carefully, with utmost attention, to the arguments and to make a robust decision. There are many difficult issues with the potential to generate conflicts. During my editorial career, conflicts have arisen among various actors in the publication process—associate editors, referees and authors. Then applied conflict resolution and advanced negotiation skills were necessary. At such times, I found common sayings, such as: “every cloud has a silver lining” or “what will not kill you will strengthen you” to be of much practical value.

On one occasion, I was threatened with resignation by an excellent scientist on the Board of Associate Editors if I accepted a paper deemed hopeless by this Associate Editor, while I regarded it as catchy, thought-provoking and controversial, hence worthy of publication.

The order of authorship can also be a sensitive issue: I was threatened with resignation by a co-author if I accepted the order of authors proposed by the first author. In different countries, the order of co-authors can be guided by different rules. Thus, I have witnessed the abuse of power, when an author with administrative power has decided on the authorship in an unfair way. At times, the persons who had done most of the work were not listed as first authors (or even, not listed as co-authors at all!). The order of the pair [doctorant, supervisor] in a paper presenting a substantial part of a doctoral thesis is culturally conditioned. It can be: [doctorant, supervisor]—the most frequent and most acceptable situation, [supervisor, doctorant], [doctorant only], or [supervisor only]. The latter option is clearly unacceptable, but editors may not have the information needed to identify such a case. Collecting statements of co-authors explaining their contribution, as practiced in some journals, is much needed.

At times, the polemic: discussion and reply, can generate conflicts. It is the editor’s duty to control the situation and not allow brutal discussion to develop, where parties try to insult each other.

There is not much I can do to please authors who are unhappy with the reviews, the editorial decisions, or the duration of processing of their paper. It is not easy to find competent and responsible reviewers for many submitted papers. It is worst if referees agree to review and then do not deliver, so that a change of reviewers is needed and much time is lost. Choosing three referees right away (improving the chance of receiving two reviews in a reasonable time) and more strict control of the review process could help.

Sometimes we detect dishonest behaviour of actors in the process: authors and referees. Unethical, but not uncommon, is the multiple submission of identical or very similar papers. Generally, anti-plagiarism software or referees will spot this. Sometimes, referees may wish to kill a paper to avoid competition. Unfair reviews by referees hiding behind their anonymity do also happen.

Homogeneity of the review process is probably an unsolvable problem. The level of criticism of individual referees differs, some reviews are really gentle, in the “let-it-fly” mode.

6 FAREWELL, HSJ!

I have been HSJ editor (first sole editor and then a co-editor) for 18 years, from April 1997 to April 2015—indeed a long interval in a human life-time—so that syndromes of age-related material fatigue have developed. Indeed, it is time to say goodbye.

I proudly declare that I strived to follow my credo of seeking fairness and looking for solutions that brought win-win (or multiple win) situations and co-benefits for several actors in the publishing process. I have tried to do it my way.

I made a fortunate choice in persuading Demetris Koutsoyiannis to join HSJ—he is a great, highly ethical scientist, who has also contributed hugely to the development of HSJ by publishing fine papers therein, such as Koutsoyiannis (Citation2002) and (Citation2003), fetching 94 and 115 citations, respectively, or a brilliant, more recent, work: Koutsoyiannis (Citation2013). Demetris became deputy editor in 2006 and then co-editor; we were joined in May 2014 by new co-editor, Mike Acreman. Now I leave the journal in the capable hands of these great scientists.

My last official duty as HSJ co-editor was chairing the Tison Award jury that decided to bestow this prestigious Award in 2015 to those co-authors of a paper by Maltese et al. (Citation2013) who were eligible age-wise. The winners in 2015 were considered for the Award already in 2014, but then Lavers et al. (Citation2013) won. In 1987, I was the first recipient of the Tison Award. In 2015, I lead the Tison Award jury as the last activity before retirement from the HSJ co-editorship.

I have been loyal to HSJ and to IAHS, and treated them as my principal Journal and my principal Association. I have been saddened by the fact that many officers of the Association and its constituent commissions published their best papers beyond the IAHS journal, having never submitted a decent paper to HSJ. I am afraid that some of them may have not read any HSJ papers, ignoring the existence of the journal. I have always had problems with interpreting such behavior. How can we alter this to the benefit of HSJ?

I thank the HSJ community: co-editors and Demetris Koutsoyiannis in particular, IAHS Press staff and Frances Watkins in particular, the Taylor & Francis personnel, many dozens of associate editors (who completed their 6-year, or more recently 3-year term of service and rotated every year since my arrival), authors, referees and the dedicated readership for the privilege of working with them over all these years, and for their support and trust. I wish the oldest hydrological journal and the people working for it every success for a very long time. I hope others will try to beat my personal ZWK-in-HSJ record of the h-index for their HSJ publications. I am aware that Demetris Koutsoyiannis is likely to overtake my record soon (but not before my retirement). Others are unfortunately very far away. I wish that other colleagues heed my call, improve their h-indices in HSJ and overtake me and Demetris, for the benefit of themselves and the Journal. shows that it is worthwhile to publish in HSJ and it is possible to collect many citations.

Farewell, HSJ! I hope we still keep in touch.

Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz

Institute for Agricultural and Forest Environment of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznan, Poland and Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Germany

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Frances Watkins, Demetris Koutsoyiannis, Cate Gardner, Christophe Cudennec, John Rodda and Valentina Krysanova for useful remarks on this note.

REFERENCES

- Alonso, S. et al., 2009. h-index: a review focused in its variants, computation and standardization for different scientific fields. Journal of Informetrics, 3 (4), 273–289. Available from: http://sci2s.ugr.es/hindex/10.1016/j.joi.2009.04.001

- Bates, B.C. et al., ed., 2008. Climate change and water. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC Secretariat, 210 pp.

- Brázdil, R. and Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2006. Historical hydrology—editorial. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 51 (5), 733–738. doi:10.1623/hysj.51.5.733

- Brázdil, R., Kundzewicz, Z.W., and Benito, G., 2006. Historical hydrology for studying flood risk in Europe. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 51 (5), 739–764. doi:10.1623/hysj.51.5.739

- Coudrain, A., Francou, B., and Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2005. Glacier shrinkage in the Andes and consequences for water resources. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 50 (6), 925–932. doi:10.1623/hysj.50.6.925

- Cudennec, C. and Hubert, P., 2008. The multi-objective role of HSJ in processing and disseminating hydrological knowledge. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 53 (2), 485–487. doi:10.1623/hysj.53.2.485

- Hirsch, J.E., 2005. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102 (46), 16569–16572. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507655102

- Hrachowitz, M., et al., 2013. A decade of Predictions in Ungauged Basins (PUB)—a review. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58 (6), 1198–1255. doi:10.1080/02626667.2013.803183

- Kierzek, R., 2013. Najlepsi w PAN. Analiza naukometryczna publikacji instytutów Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Forum Akademickie, Available from: https://forumakademickie.pl/fa/2013/05/najlepsi-w-pan/

- Koutsoyiannis, D., 2002. The Hurst phenomenon and fractional Gaussian noise made easy. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 47 (4), 573–595. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626660209492961

- Koutsoyiannis, D., 2003. Climate change, the Hurst phenomenon, and hydrological statistics. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 48 (1), 3–24. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.48.1.3.43481

- Koutsoyiannis, D., 2013. Hydrology and change. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58 (6), 1177–1197. doi:10.1080/02626667.2013.804626

- Koutsoyiannis, D. and Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2007. Editorial—quantifying the impact of hydrological studies. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 52 (1), 3–17. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.52.1.3

- Krasovskaia, I., Gottschalk, L., and Kundzewicz, Z.W., 1999. Dimensionality of Scandinavian river flow regimes. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 44 (5), 705–723. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626669909492269

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., 1997. Water resources for sustainable development. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 42 (4), 467–480. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626669709492047

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., 1999. Flood protection—sustainability issues. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 44 (4), 559–571. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626669909492252

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2002. Ecohydrology—seeking consensus on interpretation of the notion. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 47 (5), 799–804. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626660209492982

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2004. Editorial. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 49 (1), 3–6. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.49.1.3.53995

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. and Döll, P., 2009. Will groundwater ease freshwater stress under climate change? Hydrological Sciences Journal, 54 (4), 665–675. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.54.4.665

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. and Robson, A.J., 2004. Change detection in hydrological records—a review of the methodology. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 49 (1), 7–19. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.49.1.7.53993

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. and Stakhiv, E.Z., 2010. Are climate models “ready for prime time” in water resources management applications, or is more research needed? Hydrological Sciences Journal, 55 (7), 1085–1089. doi:10.1080/02626667.2010.513211

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., Szamalek, K., and Kowalczak, P., 1999. The great flood of 1997 in Poland. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 44 (6), 855–870. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626669909492285

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. and Takeuchi, K., 1999. Flood protection and management: quo vadimus? Hydrological Sciences Journal, 44 (3), 417–432. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02626669909492237

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. et al., 2005. Trend detection in river flow series: 1. Annual maximum flow. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 50 (5), 797–810. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.2005.50.5.797

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. et al., 2008. The implications of projected climate change for freshwater resources and their management. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 53 (1), 3–10. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.53.1.3

- Kundzewicz, Z.W. et al., 2014. Flood risk and climate change: global and regional perspectives. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 59 (1), 1–28. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02626667.2013.857411

- Lavers, D., Prudhomme, C., and Hannah, D.M., 2013. European precipitation connections with large-scale mean sea-level pressure (MSLP) fields. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58 (2), 310–327. doi:10.1080/02626667.2012.754545

- Maltese, A., et al., 2013. Critical analysis of thermal inertia approaches for surface soil water content retrieval. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58 (5), 1144–1161. doi:10.1080/02626667.2013.802322

- Montanari, A., et al., 2013. “Panta Rhei—Everything Flows”: change in hydrology and society—The IAHS Scientific Decade 2013–2022. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58 (6), 1256–1275. doi:10.1080/02626667.2013.809088

- Radziejewski, M. and Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2004. Detectability of changes in hydrological records. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 49 (1), 39–51. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.49.1.39.54002

- Svensson, C., Kundzewicz, Z.W., and Maurer, T., 2005. Trend detection in river flow series: 2. Flood and low-flow index series. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 50 (5), 811–824. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1623/hysj.2005.50.5.811