ABSTRACT

What would a ‘good’ industrial policy in the realm of cotton production look like? This article seeks to address this question through a focus on reforms to the cotton sector in Kazakhstan. In contrast with neighbouring Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, administrators in Kazakhstan had widely freed the cotton sector from government control as early as 1998. Agricultural collectives had been replaced by small private farms, and commercial cotton processors and traders entered the sector. However, in 2007, regulation tightened again and forced ginneries to use a complex warehouse receipt system without making sure that it was accepted by stakeholders and without appropriate institutions for implementing it in place. Moreover, it imposed financing restrictions on ginneries, which were major loan and input providers to farmers. In the following years, private producers and investors turned away from cotton, and cotton area and output fell substantially. We position our analysis in the broader debate about the right approach to industrial policy and argue that the cotton sector performance after 2007 shows how ill-designed regulation and government interference can turn a promising economic sector towards decline.

Introduction

International observers agree that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many principles of centrally planning the economy survived in Central Asia. Incumbent political elites maintained the state administration of key industries, public ownership of production resources, and even outright price controls and delivery targets in some cases (Pomfret Citation2006; Spechler Citation2008). With persistent ‘centralized control over the “commanding heights” of the economy’ (Ruziev, Ghosh, and Dow Citation2007, 7, on Uzbekistan), political patronage, corruption and cronyism continued to loom large (Collins Citation2006; Pomfret Citation2006). Various authors portray the cotton sector as a typical example: it represented a backbone of the Soviet Central Asian economy; production mandates endured the transition to post-socialism in many cases; and governments continued to siphon off considerable means by imposing unfavourable output prices on farmers (Kandiyoti Citation2007; Ruziev, Ghosh, and Dow Citation2007; Pomfret Citation2008b).

In the following, we take the cotton sector of South Kazakhstan as a case to challenge the conventional view of persistent state control in strategic sectors of the Central Asian economies. We show that, as early as 1998, the Kazakhstani government had completely loosened its grip on the cotton sector, agricultural collectives had been replaced by small private farms, and commercial entrants in the processing sector were becoming active. Only in the new millennium did the administration rediscover the cotton sector as an arena for regulation, culminating in the Law on the Development of the Cotton Sector passed in 2007. However, the new legislation failed to invigorate the sector. We provide evidence that the new policies imposing borrowing restrictions on cotton ginners, introducing producer subsidies, and stimulating the formation of a ‘cotton cluster’ turned the nascent private cotton industry towards decline.

On a theoretical level, we question the continuum of a smooth post-socialist transition from ‘central plan’ to ‘free market’ reminiscent of the intellectual spirit during the 1990s. We argue that the more recent wave of government regulation in Kazakhstan can be better understood in the context of a broader debate about the right ‘industrial policy’ for economic development. Recent evidence mostly from Latin America and Africa suggests that widespread liberalization and the wholesale retreat of the state in the wake of a policy agenda called the Washington Consensus did not result in the desired prosperity. Many economists and policy advisors thus sought to generalize the lessons from interventionist industrial policies in the supposedly more successful East Asian economies such as South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan (Rodrik Citation2007; Serra and Stiglitz Citation2008). Also observers of Central Asia increasingly call into question economic development strategies that do not assign a central role to the state. For example, Stark (Citation2010) explores the parallels between the East Asian ‘developmental states’ and the authoritarian regimes of Central Asia. Spechler (Citation2011) insinuates that state-owned enterprises should play a key role in the economic diversification of Central Asian economies. Such views resonate well with the self-image of Central Asian political leaders, who like to compare their economies to the ‘East Asian tigers’. For example, Kazakhstan's president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, is known for his admiration of the Malaysian and Singaporean development models (Wandel Citation2009).

While the intellectual pendulum swung towards a greater appreciation of active industrial policies worldwide, the question remains what the quality attributes of a ‘good’ industrial policy are. In the following, we use some of Rodrik’s (Citation2007, Citation2009) policy principles to assess the recent return to stricter government regulation and intervention in South Kazakhstan's cotton sector. We find that, despite possibly good intentions, many of the new regulations were in conflict with these principles and therefore contributed to the decline of the industry. Our findings suggest that the ‘laissez-faire’ cotton restructuring of the 1990s led to more growth and higher farm incomes from cotton than the subsequent sector regulation based on misguided principles of industrial policy.

We proceed with a brief review of the principles of good industrial policy. The following section describes the emergence of an unregulated cotton sector in South Kazakhstan after 1991. This is followed by a discussion of the 2007 cotton legislation and its effects. The final section discusses the recent cotton reforms in the light of the contemporary industrial policy literature, concluding with an outlook on the future role of the government in Kazakhstan's cotton sector.

The information and analysis presented in these sections are based on publicly accessible data and a series of interviews the first and second authors conducted during field visits to South Kazakhstan and Astana in 2010, 2012, 2016 and 2017. We refer to these interviews in the text with ‘I##’ and provide a full list of interview partners in the appendix.

Industrial policy done right – a snapshot of the debate

The historical failure of central planning in the former Eastern Bloc seemed to imply a triumph for an economic system based on ‘free’ markets and private property and driven by entrepreneurs seeking their individual profit to the benefit of society at large. In fact, ‘shock therapists’ of fast liberalization and privatization have a point in claiming that their recipes were at least partly successful in the early transition of the Central European states (Roland Citation2000, 335). However, the experience of transition countries further east and of developing economies in many other parts of the world suggests that eliminating production targets, state regulation, trade restrictions and financial repression would not be enough to instil growth and promote economic diversification (Rodrik Citation2007, 13–55).

Careful scrutiny of the East Asian ‘miracle’ shows that governments pursuing a successful diversification strategy did provide significant support to private businesses under the condition that they offered technological learning effects (‘spillovers’) and entered the world market quickly. Moreover, governments maintained close links to business groups which they saw as strategic vehicles to develop nascent industries, often coordinated by high-level government agencies. At the same time, countries devoid of natural resources such as Korea, Singapore and Taiwan invested massively in human skills, infrastructure and supporting services (Lall Citation2006, 93; Stark Citation2010).

Adherents of a laissez-faire strategy counter that governments cannot ‘pick winners’, i.e. select promising industries or companies, due to the ‘problem of knowledge’, i.e. the impossibility to know and process all the relevant information necessary for a support decision (Wandel Citation2009). Furthermore, businesspeople and bureaucrats may compromise industry interventions through political capture, corruption or ‘rent seeking’. While proponents of modern industrial policy acknowledge these concerns, they argue that they arise with any sort of government intervention, even in areas where it is much less controversial (such as health, education or infrastructure; Rodrik Citation2009). Rodrik (Citation2007, 100) envisages a situation where markets and private entrepreneurs drive the development agenda, but governments engage in a strategic, coordinating partnership with the private sector.

Rodrik (Citation2007, 104–109) usefully focuses on two major justifications for government intervention. First, he stresses that economic restructuring and diversification requires entrepreneurs to engage in a process of ‘self-discovery’. They must experiment with new products and technologies and possibly adapt them to local circumstances in order to find out whether they are profitable. However, while successful testing of product or technological innovations provides great value for the domestic economy at large and may easily invite imitators to follow suit, the experimenting entrepreneur bears all the cost alone in case of failure. Funding of innovative entrepreneurial activity thus turns out to be a crucial bottleneck of economic development. Following Rodrik, governments may consider providing public subsidies or other sorts of protection to experimenting entrepreneurs, but only under the condition that they reach those innovators alone and bypass copycats, and that they are phased out if the innovations do not perform as expected, e.g. because they fail to enter export markets.

Second, many new projects require complementary investments or services to become profitable. Rodrik (Citation2007, 107) gives the example of the Taiwanese orchid industry, which emerged after the decline of domestic sugarcane production. A farmer considering investing in orchid greenhouses will contemplate whether she also has access to electricity, irrigation, transport networks, phytosanitarian services and international marketing. While many of these services could be provided privately, each of them may become profitable only if all other services are set up simultaneously – a typical coordination problem. This may justify the government to step in by engaging in active coordination of private actors or by providing subsidies or investment guarantees to certain activities. Such a rationale has motivated the public announcement of ‘industry clusters’ in the past. However, Rodrik stresses that coordination failures typically arise with regard to specific activities or technologies, such as a new product or service, not entire sectors. Wholesale agricultural subsidies or trade protection will not solve the coordination problem preventing the adoption of a new technology.

Coherently focusing on these types of learning spillovers and coordination failures leads to a number of best practice recommendations for industrial policies (based on Rodrik Citation2007, 114–119, Citation2009):

Improve funding for activities that are innovative and create spill-overs. Subsidized activities must have clear potential for demonstration effects. Target activities, not sectors.

Set clear benchmarks for success and failure; include sunset clauses in support programmes.

Establish coordination councils such as chambers of commerce or professionally managed business associations including a wide array of stakeholders; engage in intensive communication and deliberation with the private sector.

Make sure that government agencies in charge of programme implementation are professionally managed and competently staffed.

Concrete measures based on these principles may include focused subsidy of innovative activity, publicly supported high-risk funding (e.g. via development banks or venture funds), the establishment of transparent and accountable coordination councils, public support of research and development that is integrated in private-sector activity, and subsidies for general technical training and international exchange of knowledge.

Lall (Citation2006, 80) summarizes the credo of modern industrial policy as follows:

Accepting that past industrialization strategies were often wrongly designed and poorly implemented, … greater reliance on market forces actually requires a strong proactive role for the government. Markets are often deficient and the institutions needed to make them work efficiently are often weak or absent.

Central planning is not an alternative, but restructuring policies that foresee a strategic collaboration between the state and the private sector have proven successful in many places.

The unregulated cotton sector before 2007

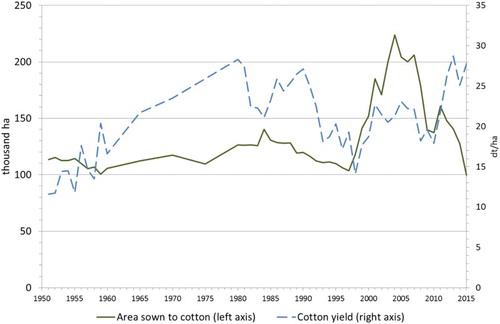

The cotton industry in Kazakhstan dates back to the Soviet period, when the economy was entirely run by the state and the planning administration gave orders to set up cotton plantations and irrigation infrastructure, fostered the development of cotton varieties and massively expanded the area under cotton. Cotton production is geographically limited to 2 out of 14 provinces: South Kazakhstan and Kyzylorda. Moreover, within these two provinces, only Maktaaral and Shardary Districts used to be the major cotton producing regions. Cotton area and cotton yields increased until ca. 1980 and subsequently declined (). Craumer (Citation1992, 145) cites increasing salinity of irrigated land, declining soil quality due to monoculture and lack of organic fertilizer, and plant diseases such as cotton wilt as major reasons for decline. Lower administered cotton prices and a deteriorating financial situation for cotton farms, symptoms of the emerging economic crisis in rural areas, contributed as well (Gleason Citation1991, 343).

Figure 1. Area sown to cotton and cotton yield in South Kazakhstan, 1950–2015.

The emergence of a privately coordinated cotton export chain after independence

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to the removal of government control, so that both cotton producers and cotton processing plants (ginneries) were free to establish their own relations. The Kazakh government was preoccupied with investments in the oil sector and did not care much about agriculture (Kalyuzhnova Citation1998). As in other provinces in Kazakhstan (Petrick, Wandel, and Karsten Citation2011), individual farms in South Kazakhstan controlled a significant share of total agricultural land by the turn of the millennium. This share increased consistently over the years, so that now about half of the land is used by individual farms. The remaining land remains in state farms or private agricultural enterprises. On average, individual farms in South Kazakhstan are much smaller than similarly organized farms in the rest of the country, about six hectares of arable land per farm.

Some interview partners argued that the reform progress actually went too far, because, when compared with the former collective farms, land allocations led to very small farms for cotton growers (I8; I11). Moreover, land reform created a quite homogeneous group of smallholders, with large private farmers being the absolute exception (I8 speaks of two or three private farms operating 1000 ha in all of South Kazakhstan). Sadler (Citation2006, 101) concedes that gins, not farmers, were in control of the processing chain, as each farm operates only a small plot and farmers don't have access to credit.

In fact, in the mid-1990s, cotton farmers in Kazakhstan faced unfavourable prices compared to neighbouring countries, due to a mixture of market power of the cotton ginneries, quality differences, and transport and other costs to get the cotton to the border, rather than policy-induced distortions against farmers. Ginneries had become fully privatized by 1998. However, the majority of the gins in Maktaaral District only started operations after 1998. Between 2000 and 2002, the ginneries sector had become more competitive. By 2005 there were 15 ginneries operating in Kazakhstan. The farmers’ market position improved as the number of cotton gins increased. Pomfret (Citation2008a, 232) explains the increase in ginning plants in Kazakhstan with two factors. First, gins owned in conjunction with Russian companies were entering the local market so that they could export directly to Russian textile mills. Second, because of the availability of smuggled raw cotton from Uzbekistan, large amounts of cotton were available for purchase in Kazakhstan without the provision of crop finance and as spot cash purchases, which increased demand for ginning services. According to Dosybieva (Citation2007, 127), Chinese cotton traders became active in South Kazakhstan at this time as well, possibly increasing competition on the demand side.

Contracts and pricing

Cotton ginneries eventually developed different types of contracts. Since the cotton industry delivered to export markets, the ginneries linked the contract price to the world market price, in this case the Liverpool Cotton Association price (I2). The price formula in the contracts changed over the years, with the formula in 2004 being based on the ‘A’ index at the time of fixation (delivery or later) minus 10%, minus the cost of ginning (at USD 150/tonne) and a ginning outturn of 32%. The ginning outturn (i.e. the cotton fibre received after ginning) determines the economically valuable part of the raw or ‘seed’ cotton.

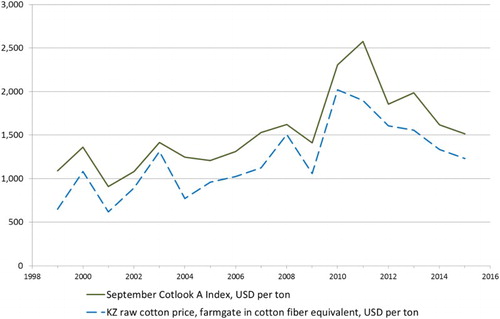

In practice, a two-tier cotton market emerged in Kazakhstan, differentiating the price paid for raw cotton, covered under the above agreements, and the price paid for production (‘free seed cotton’), which is in excess of the original agreement (I3; I5). Inne 2003, when the ‘A’ index was 74 US cents per pound, ginners were paying an average of USD 500/tonne for free seed cotton, which is more than USD 1500/tonne in cotton fibre equivalent. Prices for free seed cotton actually reached USD 600/tonne, 21% more than the price paid for contracted cotton. The premium was due to the competition between the ginners to secure volumes of raw cotton. Both international and local prices were constantly rising from 2001 to 2003, which encouraged the expansion of cotton production ().

Figure 2. Comparison of world and Kazakhstani farm-gate cotton prices. Source: Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan; National Cotton Council of America.

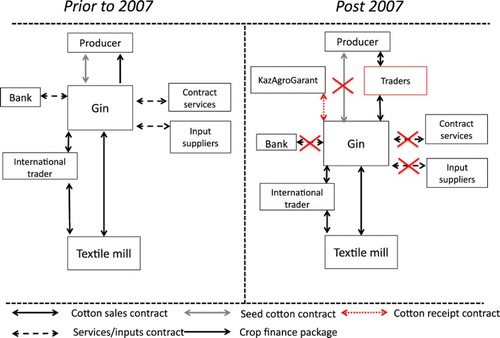

Ginneries were providing crop financing to Kazakhstani producers, as farmers had little collateral and were therefore unable to obtain commercial bank credit (I1). Based on farm survey data, Sadler (Citation2006) states that 89% of respondents received finance from their gins. Producers entered into a contract to supply a gin with a fixed amount of cotton, for which they would receive a price linked to the world price index at the time of delivery. They did so to obtain pre-finance, then provided as 30% on signing an agreement to deliver a certain amount of cotton, 40% at harvest and 30% upon delivery (Pomfret Citation2008a, 243). A large part of this finance was provided in the form of physical inputs (fertilizers, fuel, etc.). Ginners financed the producers in the absence of any collateral guarantees and relied on a signed contract for repayment of the loans (, left panel).

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the cotton supply chain before and after the 2007 legislation.

Ginners in turn obtained finance from three sources: trader finance, domestic banks, and their own cash reserves. Trader financing took the form of forward sales of cotton, against which the ginners received a percentage of the value of the cotton that was due to be delivered under the contract. This system worked well, as ginners and traders had established trustful trading relations. The ginners also developed financing relations with domestic commercial banks. Previously, the ginner's inability to provide cash and collateral cover to the domestic bank limited the amount of finance available from this source. Initially, the cost at which these banks were prepared to offer finance was very high (generally, around 15–20% on top of the international interbank lending interest rate). However, this cost subsequently dropped, and the credit volume increased (Sadler Citation2006). The gins used their assets as collateral to obtain loans. The loans were used to finance cotton producers further down the supply chain by providing production inputs or cash. This had created a win-win situation for all market participants.

Performance of the sector before the regulation

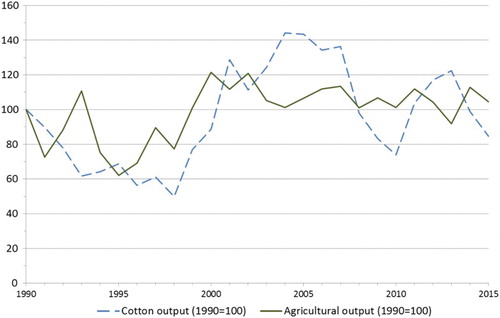

After a decline in the first years of transition, the cotton sector developed very well. Following an all-time low in 1998, physical output doubled in three years, and output growth even outpaced the agricultural sector in general (). A major factor in rising output was the expansion of sown area (). After 2000, output levels were consistently higher than in the last years of the Soviet Union, and also higher than in agriculture on average.

Figure 4. Physical output of agriculture in total and cotton in particular in Kazakhstan, 1990 = 100.

Notably, the cotton sector outperformed the grain industry in the country. Up to the mid-2000s, the area under cotton grew dynamically, whereas grain area consistently declined (Oshakbayev et al. Citation2017).

The cotton sector represents the only known example of private vertical coordination on a large scale in Kazakhstani agriculture. In the early 2000s, local and international observers widely regarded the sector as a success story. The reform progress in Kazakhstan contrasted sharply with neighbouring Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, where national governments rigorously control the cotton sector (Pomfret Citation2008b; Shtaltovna and Hornidge Citation2014). The private coordination system coincided with a period of rising world cotton prices. Together with the boom in ginning operations in South Kazakhstan in the early 2000s, competitive market forces ensured that even small farmers benefited from the private chain coordination.

The 2007 Law on the Development of the Cotton Sector

The Law on the Development of the Cotton Sector (the cotton law) was enacted in 2007 following presidential order (I1). Before the cotton law, no specific regulation of the cotton sector existed. According to official statements, the purpose of the law was to improve the competitiveness of the domestic cotton industry through the introduction of science-based innovation, technical regulations and the industrialization of cotton production, its integration with the textile and food industries and regulation of relations between the participants of the cotton market.Footnote1

Context factors leading to the adoption of the cotton law

In hindsight, the confluence of a number of factors provides a plausible explanation for why the government interfered in an apparently well-performing, privately coordinated cotton value chain. First, due to a number of bankruptcies of independent ginneries, the remaining processors managed to set up an at least temporary informal cartel, which depressed local producer prices in 2004 and increased the margins of cotton processors (). Cartelization may have been linked to the gins’ emerging practice of creating and sharing blacklists of farmers. Farmers on the lists had been caught side-selling their cotton outside the agreed forward contracts, and ginners wanted to prevent this opportunism (I5). Complaints by farmers to local government officials about these circumstances were finally reported to the central government in the capital, which saw a need for action. During a visit to South Kazakhstan in September 2006, president Nazarbayev called on cotton ginneries to pay decent prices for cotton – otherwise the government would set up its own cotton processing plants (I5). The provincial administration of South Kazakhstan supported this idea (Dosybieva Citation2007, 128).

Second, at this time, the government had already had positive experience with a regulated warehouse receipt system in grain trading (Höllinger and Rutten Citation2009; OECD Citation2013, 145). International donors were advocating the implementation of a similar system in the cotton sector (Sadler Citation2006, 111; World Bank Citation2007, 72, 75). A warehouse receipt system is a form of commodity finance that allows farmers to store their harvest in a public or private warehouse. The warehouse certifies the receipt and quality of the commodity in store, which is owned by the producer. This receipt can be used by the farmer as collateral to obtain funding for his or her production operations. While similar systems have a long tradition in Western countries, experts point out that its success crucially depends on factors such as the availability and integrity of public warehouses in rural areas and the quality of the legal and regulatory environment (Höllinger and Rutten Citation2009).

Third, these cotton-specific factors resonated well with an overall political imperative to establish state-mandated industry clusters in various sectors, to promote the diversification of the Kazakhstani economy (Wandel Citation2010). In practice, this strategy typically involved the establishment of state-managed enterprises in key sectors of the economy, and it used to be based on a general scepticism concerning the viability of small businesses, particularly in agriculture.

The establishment of a state-mandated cotton cluster

In 2005, the government established the Ontustik Special Economic Zone (SEZ), near the city of Shymkent, and thus about 250 km from the cotton-growing area in Maktaaral District. The cluster was aimed at promoting the development of the textile industry, in particular the production of readymade garments, stimulating the integration of Kazakhstan's national economy into the world market, encouraging international trademark owners to set up manufacturing of readymade textiles in Kazakhstan, setting up high-tech manufacturing facilities, and expanding the range of textile goods produced.

The government offered tax exemptions to ginners, and the SEZ was designed to become a textile cluster in the Southern Kazakhstan Region. It was initially planned to attract USD 1 billion of investments in three years and to build 15 processing factories, which would compose a full cotton processing cycle.

In 2007, the government also established KazMakta, a subsidiary of the state-owned Food Contract Corporation. KazMakta was supposed to engage in cotton procurement, processing and cottonseed production.

The forced introduction of cotton warehouse receipts

According to the law, a warehouse receipt system was to be introduced that included mandatory examination of cotton fibre quality, formal conditions under which ginners were supposed to issue receipts, and the right of the farmer to request the release of the cotton in exchange for warehouse and pledge certificates. Cotton processing companies had to participate in a guarantee system for cotton receipts. This participation was ensured by signing an agreement with the state company KazAgroGarant, a subsidiary of the KazAgro holding, which was established in 2003 to ensure payments under the grain receipts system. The law also defined requirements for the premises, equipment and machinery of a ginnery.

Article 15, concerning ‘Limitations on the Activity of a Cotton Processing Enterprise’, was the most controversial part of the law. Two main limitations imposed in 2007 were:

Prohibition of business activities unrelated to warehouse services, with the exception of production and marketing (sale) of the products and by-products of cotton processing and free warehouse services.

Prohibition of issuing guarantees and using their property as collateral in loan agreements with third parties.

Both prohibitions fundamentally undermined the previous function of the ginneries as providers of inputs and services to farmers and as providers of commodity finance using their own assets as collateral.

Opposition to the law

Legislators developed the cotton law in 2005 and adopted it in 2007. As Dosybieva (Citation2007) reports, it was hardly uncontested. It faced fierce opposition from representatives of the incumbent processing plants, organized in the Kazakh Cotton Association, as well as from farmers:

Nurlan Kanybekov, the head of Nimeks, one of the biggest cotton companies in the region, called the ‘Law on the Development of the Cotton Industry’ … the ‘law on hindrances to cotton processing plants’. He added: ‘Suddenly, the government decides to make a law today, which was necessary in 1991. At that time all of us experienced difficulties. And the present-day project will allow corrupt officials to satisfy their ambitions through legal means. Seventy per cent of the law's essence is about ways to restrict cotton processing plants. Neither producers nor processors of cotton need this law. The appearance of the ‘Provision Corporation’ [the department responsible for governmental purchase] interested in cotton has coincided with the development of this project. (Dosybieva Citation2007, 128–29).

officials from the oblast already started discussing the necessity of a regrouping of small farms during their meetings at the beginning of 2005. They explained that small farms (5–10 ha) do not observe the rotation of crops and the land becomes overused and infertile. They also argued that large farms can take bank loans to facilitate their development and upgrade their equipment. However, many farmers think that the unification of smaller farms will take them back to forced collectivization. ‘Why would I unite with somebody?’ said a farmer, Dosjan Beibitov. ‘I have five hectares of land and I have been growing cotton for five years. We gather 3000 kilograms of cotton per hectare. I buy quality seeds. I’ve never made any losses. I can afford to utilize machinery. I am the owner of my land now. But I do not have any confidence that I will own my land in the future.’ … ‘I do not want to enter any unions’, said Kairat, a farmer. ‘I am quite happy with going to my investor. I know he can always help me. If farmers need money for weddings or funerals, investors never refuse. Of course, we pay back all debt in the form of harvest, but we are fine with this. They say that investors will be prohibited from giving us money. Is this the government’s way to reward those who helped the cotton industry?’ (Dosybieva Citation2007, 129–30).

The cotton sector after 2007

Failure of the cotton receipt system

As explained in preceding sections, a specific feature of the cotton market before the adoption of the law was to attract short-term loans by cotton ginneries, secured by assets and the conclusion of forward contracts with producers. Since 2007, ginneries have no longer dealt with banks to finance cotton production, and they no longer provided contract services and inputs (, right panel). Instead, a new player – the trader – appeared in the cotton market. According to experts, traders are in most cases affiliated with the ginners and were launched by the latter to comply with the cotton law and facilitate the procurement of raw cotton from producers (I1). Some farmers complain about the bargaining power of the new traders (I3). Others argue that they increase competition (I4).

Cotton receipts, which ideally should have provided cotton growers with opportunities to attract financial resources, failed to gain widespread acceptance (I12). One of the reasons for the lack of interest in the warehouse scheme might have been the high annual fee. In 2008, it amounted to KZT 126 per ton of raw cotton, i.e. 0.2% of the market value of cotton in Kazakhstan at that time. Following the complaints of the processing companies, administrators reduced tariffs by almost half, to KZT 64. But this did not boost the participation rate.

In recent years, a small fraction of existing processing enterprises have signed contracts with KazAgroGarant, while the share of cotton under the guarantee scheme in the total cotton output went down to 18,000 tons (about 7% of total output) in 2015 (Oshakbayev et al. Citation2017). The participating organizations were large-scale enterprises, namely the Myrzakent, LLP, cotton processing plant, with 6000 tons of guaranteed cotton; Hlopkoprom-Yug (1138 tons), the Cotton Contract Corporation (6934 tons), and AIIG-Kazakhstan, which owns two ginneries with a total capacity of 4000 tons.

The central idea of introducing cotton receipts was that they could be used by cotton growers as collateral in obtaining loans directly from a bank. But, probably due to a lack of experience and trust and a weak regulatory framework, commercial banks refused to accept cotton receipts as collateral in loan agreements (I5). Since the ginneries could not use their property as collateral anymore, the financing of producers ceased (I8). Furthermore, the new system did not overcome the seasonality problem in the financing of production. Cotton farmers receive cotton receipts after submitting cotton to the processing companies, i.e. in autumn; but farmers need cash during spring fieldwork, in February and March. Farmers were not used to or did not want to store cotton, preferring on-the-spot settlement of their financial dealings with cotton gins (I3; OECD Citation2013, 145).

The global financial crisis of 2007/08 further deteriorated the framework for cotton producers. It may be hypothesized that even if the old scheme of forward contracting were in place, ginners would have faced problems in obtaining loans anyway. However, though interest rates on commercial bank loans increased in 2008, they have gradually fallen ever since, and they returned to their pre-crisis level in 2010.

In summary, the following factors contributed to the failure of the cotton receipt system:

Cotton producers were not familiar with the storing system and had no demand for storage; producers preferred on-the-spot payment in cash.

Initially high fees for participating in the warehouse system discouraged participation.

Many warehouses failed to comply with public certification of their warehouse operations or did not even apply.

Banks did not accept receipts as collateral; and thus

The forced introduction of the warehouse system failed to overcome the seasonal mismatch of demand and supply in funding cotton planting operations by farmers.

Declining private activity in the sector and the failure of the cotton cluster

Before 2007, ginners facilitated the growth of production, attracting investments from domestic and foreign investors and obtaining loans from commercial banks. They used these funds to finance producers under futures contracts. When legislators banned the processing companies from commercial activity and loans, this immediately led to an outflow of capital from the sector (I8). Moreover, due to declining cotton area and output, a problem of overcapacity in processing emerged (I7). In 2015, only 12 of the 23 existing ginneries were operating.

On the other hand, the Ontustik SEZ was criticized for being too remote from the main cotton-producing areas. Observers considered the project unfeasible due to the low quality of Kazakhstani cotton, which is normally of the third grade and can at best reach the second grade, whereas textile products of high quality are made primarily from cotton fibres of the first and highest grade. The latter is not available in sufficient quantity in Kazakhstan (I5). One reason for the low quality of the cotton is the absence of elite seed (I4; I7). Farmers can either buy seed from the ginneries or import if from abroad via traders. But according to local interviews, low-quality seed is also smuggled from Uzbekistan and offered to cotton producers at a very low price (I7). In the absence of a seed selection and cleaning infrastructure, traders often mix varieties, and the transparency of the seed market is low (Dosybieva Citation2007).

In 2011, the first textile factory, Khlopkoprom-Tselyuloza, began operating in the SEZ. But in 2015, it was sold to private investors. At present only 8 of the 15 factories in Ontustik are operational. Investments reached USD 150 million, mostly from semi-government loans. The amount of processed cotton is only 140 tons, much less than expected. The management of the SEZ is now considering diversification options.

Declining cotton area and exports

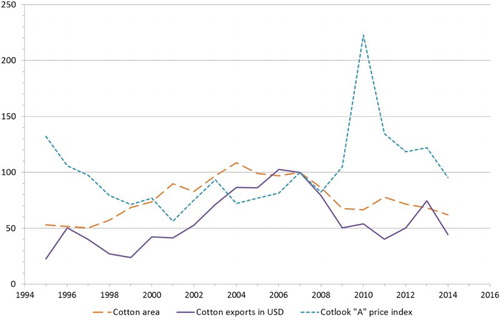

Cotton area and output steeply declined after the introduction of the cotton law in 2007 ( and ). In 2015 total sown area stood at only half of the 2004 level, although hectare yields have been picking up recently. shows how cotton area and exports were effectively delinked from the world cotton market after the introduction of the law. Between 1998 and 2007, the world cotton price, cotton area and cotton exports in Kazakhstan broadly moved in parallel. However, since 2007, area and exports moved in the opposite direction from the cotton price. Cotton area in Kazakhstan reached a 12-year low in 2010, just when cotton prices were skyrocketing.

Figure 5. Kazakhstani cotton area and cotton exports and cotton world market price (2007 = 100).

Increasing government spending on cotton in the face of an eroding regional tax base

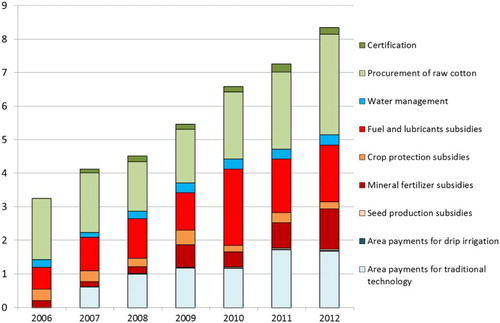

Starting in 2007, the government has provided cotton farmers hectare-based subsidies. The rate of the subsidies exceeded USD 60/ha and even USD 160/ha when it was produced under drip irrigation (OECD Citation2013, 135). However, shows that the latter made up only a tiny fraction of the total amount of subsidies paid out to farmers, on top of the area payments under conventional technology. Cotton farmers also benefit from a range of other subsidies that are typically linked to input use or involve the procurement of raw cotton by the state-owned enterprise KazMakta (). These subsidy programmes existed before 2007, but in terms of nominal spending they were significantly extended afterwards.

Figure 6. Structure of government support of the cotton sector (KZT billions).

At the same time, the public budget suffered from a decrease in revenues from the cotton processing plants. For example, one of the leading cotton processing plants, Ak Altyn Corporation, paid KZT 20–25 million in taxes each year before 2007. The amount subsequently declined by half as a result of its reduced scope of activities. According to parliament representatives, some of the newly emerging traders and middlemen evade taxes, which led to a further decline of the public budget.

Water shortage and crop diversification away from cotton

While the failure of the cotton regulation contributed to the decline of cotton production in a significant way, two other factors reinforced this trend: a perceived shortage of irrigation water, and the government strategy of active crop diversification away from cotton.

The natural scarcity of water resources has recently exacerbated supply uncertainty due to political tensions with neighbouring Uzbekistan. The crucial source of irrigation water for South Kazakhstan farmers is the Syrdarya River, which originates in the Fergana Valley of Uzbekistan (see Wegerich Citation2011 for an overview). The main supply is provided by the artificial Dostyk (‘friendship’) Canal. This is an unlined earth canal that diverts water from the Syrdarya River at the Farkhadskaya Hydroelectric Complex in Uzbekistan, across the border from the South Kazakhstan cotton region. In 2008, Maktaraal District of South Kazakhstan Province faced a critical shortage of water. The daily water intake from Dostyk Canal had fallen to 20 m3/second, less than half of the 70 m3/second guaranteed by a memorandum that had been signed by Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s governments in 2000. Local authorities in Maktaaral were forced to appeal to the national government. The issue was solved after the government issued a warning to the Uzbek side (RFE-RL Citation2008). The water supply was restored to adequate levels; but farmers learned a lesson about the uncertainty of water supply.

Nevertheless, as mentioned before, the adoption of drip irrigation is slow. One reason may be that it depends on the availability of high-quality, soluble fertilizers, which are scarce in Kazakhstan. Drip irrigation systems are also much more service-intensive than traditional open-furrow systems, and service networks are not well developed (I11).

To promote crop diversification in South Kazakhstan, the provincial government drafted a comprehensive plan for the diversification of cropland in Maktaaral District. The main stimulating instrument was an area-based payment for the production of alternative crops, in particular vegetables and melons. It went along with an information campaign by local authorities explaining to the farmers the possible benefits of switching to crops other than cotton (Kazinform Citation2013). Indeed, since 2008, the area under melons and vegetables has consistently been growing in Maktaaral, the major cotton producing district (Oshakbayev et al. Citation2017). In South Kazakhstan Province in total, vegetables and melons together occupied about one-quarter of the arable land allocated to cotton in 2005. Since 2012, cotton has been grown on less land than vegetables and melons together.

Yet, further constraints hamper the expansion of other cash crops on lands previously occupied by cotton. First, cotton land is often saline, which limits the choice to salinity-tolerant crops. Rehabilitating these lands would require investments in drainage infrastructure, which is mostly operated using electric pumps. It is thus expensive for small family-operated farms. Implementing a complex programme of crop diversification and soil rehabilitation, state agencies have recently taken over the management of irrigation and drainage systems, after failed attempts to install decentralized water user associations (I11; Zinzani Citation2015). Even so, the agricultural development programme Agribusiness 2020, which was adopted in 2013, continued to stimulate crop diversification through higher subsidies for priority crops. It supported farmers by promoting moisture-saving technologies (drip irrigation and no-tillage), compensated for costs of mineral fertilizers and herbicides, and partially reimbursed lease payments.

Follow-up reform in 2015

In July 2015, the government responded to the problematic situation in cotton financing by ratifying the law On Introducing Amendments and Additions to Some Legislative Acts of Kazakhstan on the Development of the Cotton Industry. This time, members of a parliamentary committee were able to convince the minister of agriculture of the proposed changes. The key modification was to lift the ban on complementary business activities of cotton processors in Article 15 of the law (). However, the ban on using property as collateral was kept in place.

Table 1. The 2016 amendment of Article 15 of the cotton law.

Kazakhstan’s cotton reform in the light of the industrial policy debate

Accepting the premise that the state has a role in actively stimulating industrial development, the literature reviewed above suggests that it should focus on promoting innovative activity, not entire sectors. Moreover, government agencies may assist in the coordination of private businesses activity, possibly complementing it with essential public services. Previous sections have shown that Kazakhstan's recent cotton sector policy was inconsistent with these principles in various respects:

Whereas industrial policy should improve private businesses access to funding, the 2007 legislation had the opposite effect. The cotton law essentially prohibited the collateralization of loans extended by the ginneries, while it failed to install a functioning warehouse receipt system in its place.

The subsidy payments that the government introduced in parallel to the new regulation mostly failed to discriminate between innovators and ordinary producers. They instead ushered in an era of broad-based government funding of all steps of the cotton growing process, not focusing on demonstration effects at all.

Area payments for cotton under drip irrigation represent the only exception, but their share in overall subsidies was minimal. Subsidies for using domestic fertilizers not amenable to drip irrigation discourage the use of the latter, which illustrates a persistent coordination problem not adequately tackled by the government (Petrick and Pomfret Citation2017, 471).

Lack of coordination also prevented the successful introduction of the warehouse receipt system. After the cotton law was passed, it turned out that neither warehouses nor banks or farmers welcomed it or had an actual demand for the new service.

According to the evidence presented in the discussion of the 2007 law above, the establishment of the SEZ near Shymkent seemed to owe more to the preferences of the highest government authorities than to an intensive and transparent process of deliberation among policy-makers and the private sector. The state-controlled cotton processing cluster was established in a logistically suboptimal location, and it failed to take into account the subprime quality of Kazakhstani cotton. Representatives of the key business association, the Kazakh Cotton Association, strictly opposed it.

Implementing the new cotton law involved several government agencies, including KazAgroGarant as a guarantor of the warehouse receipts and KazMakta as a procurement agency, as well as other KazAgro subsidiaries. We don't have direct evidence on their performance, but Nellis (Citation2014, 290–291) and Schiek (Citation2014, 192–218) suggest that Kazakhstan's civil service suffers from low salaries, career incentives are rarely based on meritocratic principles, regulation is implemented in uneven and non-transparent ways, and businesspeople regularly complain about corruption as a major impediment to effective public service provision. Farmers and local cotton experts criticize that the Ministry of Agriculture in Astana does not have the necessary expertise in cotton production (I1).

In sum, rather than promoting innovation in a targeted way and helping tackle coordination deficits among private businesses, the government thwarted entrepreneurial initiative by crowding out private funding sources and providing inconsistent incentives to producers. In the 2000s, rather than relinquishing the driver’s seat to the individual entrepreneur, it returned to principles of top-down planning and public procurement. Moreover, the provincial government obstructed the cotton cluster strategy by subsidizing farmers to diversify into other crops, such as vegetables or melons. In hindsight, this sort of industrial policy seemed to be clearly dominated by widely autonomous private-sector coordination reacting to market signals. Based on the basic knowledge of cotton production inherited from the Soviet period, farmers and processors managed to develop innovative contractual forms of cooperation on their own that allowed significant growth of the sector.

Why did the government widely neglect the cotton sector during the 1990s and return to a centralized policy approach only in the new millennium? Kalyuzhnova (Citation1998) and Schiek (Citation2014) argue that, in the early transition years, the presidential administration instigated a race for assets to consolidate its political and economic power. It grabbed the proceeds from privatizing agribusiness companies that were of national importance, but otherwise neglected the agricultural sector. In South Kazakhstan's overlooked cotton areas, this led to a sort of liberalization by accident, and the administration paid attention to the sector only after it had a firm power base in place. Realizing that the economy had to diversify to reduce vulnerability to price and demand shocks in the oil business, it resorted to a state-driven agricultural modernization strategy that owed much to the Soviet heritage. Petrick and Pomfret (Citation2017, 474–75) suggest that Nazarbayev's career as an engineer and economist in the steel industry, his socialization in the Soviet bureaucracy, and his appreciation of a management style entailing clear orders, deadlines and action plans foreshadowed these later policy choices.

Conclusions

Two and a half decades of economic transition to market economic principles have witnessed a spectacular growth and an almost equally spectacular decline of cotton production in Kazakhstan. The turning point was marked by the 2007 adoption of the Law on the Development of the Cotton Sector, which for the first time after the demise of Soviet central planning reintroduced comprehensive government regulation in the cotton chain. However, rather than improving vertical coordination and stimulating output growth, the available evidence suggests that it had the opposite effect. The state-mandated cotton cluster failed to take off. Cotton area declined, despite significantly higher subsidies offered to cotton farmers in the post-regulation period.

We conclude that the role of the state in restructuring Kazakhstan's post-Soviet cotton sector was ambiguous at best. On the one hand, it provided the basis for private-sector coordination by withdrawing production mandates, privatizing assets, and permitting thorough farm restructuring in the first years of transition. Although due more to neglect than to deliberate choice, this strategy had much in common with a ‘shock therapy’ of transition practised further west and advocated by international advisors. After all, it turned out to be fairly successful. Privatization led to cotton chain structures broadly comparable to the major Western producers, such as Australia or the US, perhaps with the exception that farmers’ bargaining power vis-à-vis the ginners is much weaker due to their smaller size and constrained capital access.

On the other hand, the subsequent return to a more proactive industrial policy in the cotton sector was far too unspecified to support truly innovative activities and failed to coordinate those links in the chain that required it the most. While the government rhetoric likes to stress the importance of grand development strategies borrowed from Singapore, Malaysia or US business schools, we showed that actual implementation ignored many best practice principles to be learned from these cases. The recent experience in the cotton sector provides yet another example of how a top-down industrial strategy administered by bureaucrats and pushed by generous subsidies funded from oil revenues, coupled with distrust in independent entrepreneurial initiative and market coordination, fails to reach its possibly well-intended goals of stimulating economic growth and diversifying the economy. In this case the result is even more lamentable, as the lost added value from the previous export chain must be added to the cost of wasted government resources.

Taking seriously the insights of the contemporary industrial policy literature, the Kazakhstani administration should engage in a strategy that empowers rather than patronizes the entrepreneur. It should revise its subsidy system and focus government support on activities that have a clear potential for demonstration and learning spill-overs. It may turn out that such focusing is better achieved by a strengthened commercial banking sector than by government bureaucrats. In addition, more proactive coordination of the cotton sector seems to be required in areas that were neglected by the government's most recent regulatory efforts. These include cotton seed research, certification and distribution, as well as irrigation water management. Reacting to complaints about the market power of ginneries, a more reasoned policy would have strengthened the bargaining position of the small producers, for example by encouraging the establishment of storage capacities.

According to the recent literature, successful industrial policy requires that government and private business communicate at eye level. The Kazakhstani government has allowed and even fostered the emergence of high-level organizations that represent the interests of agricultural businesses, such as the National Chamber of Commerce Atameken Union (I13) and the Republican Public Union of Farmers of Kazakhstan (I14). The latter represents the individual farmers, and a manager reported that it had significantly broadened its member base recently. According to our interviews, the Union of Farmers has understood that better policies require more transparent and more effective communication with the agricultural administration. The government should allow a more independent and self-confident stance of these organizations without meddling in their internal management and opinion formation.

The evidence presented here suggests that a liberal reform of the cotton law that relaxes the constraints on processor funding might restore the vibrancy of the cotton sector. It could leave a possibly modified institutional set-up for voluntary warehousing still in place. After all, the gin managers have shown once before how to turn a formerly state-controlled and run-down sector into a dynamic segment of the rural economy.

Whether ginning operators could replicate this exercise in a different regulatory environment remains uncertain, though. Farmers may have come to appreciate the advantages of a more diversified cropping pattern in the meantime. Crop diversification has many economic and ecological benefits (Bobojonov et al. Citation2013), such as diversifying the income risk of farmers, reducing water consumption or increasing water productivity, and levelling the peaks of seasonal labour demand during harvest time. But the widespread salinity of the soils and the continued need for irrigation may demand additional regulatory effort on the side of the government, even if farmers decide to turn away from cotton. Healthy crop rotations should include fodder crops, which raises questions concerning the future of livestock production in the region. Lacking food quality and safety standards and absent domestic meat and dairy value chains call for careful public regulation (OECD Citation2013; Petrick et al. Citation2014). As an unintended side effect of the cotton law, the evident diversification path chosen by farmers in South Kazakhstan may still produce more sustainable economic and ecological outcomes in the long run than a return to the cotton monoculture.

Kazakhstan's episode of market-driven coordination of the cotton sector holds valuable lessons for its Central Asian neighbours. It shows that private entrepreneurs, even small farmers, can be successfully integrated into an export-oriented value chain released from government intervention and control. While dependence on international commodity markets involves risks, it clearly also creates opportunities that, as the growth of private cotton area in South Kazakhstan during the price boom of the early 2000s shows, may be a strong force of structural change in a traditional sector. Kazakhstan's subsequent experimentation with industrial policy provides important insights as well. Its blend of Soviet-style central planning with strategies copied from other countries and contexts demonstrates the pitfalls of an ‘innovative’ approach to sector management that its neighbours may want to avoid.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the IAAE Inter-Conference Symposium, Agricultural Transitions along the Silk Road: Restructuring, Resources and Trade in the Central Asia Region, in Almaty (Kazakhstan), 4–6 April 2016. The authors wish to thank the conference participants, Nozilakhon Mukhamedova, and the three anonymous reviewers for Central Asian Survey for helpful comments. Support by Sayin Baktybayev in arranging the interviews and providing background information is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See the original legal text at http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/Z070000298_ in Kazakh, Russian and English.

References

- Azhimetova, G. 2011. “Cotton and Textile Branch of Kazakhstan State: Problems and Prospects for the Development.” African Journal of Agricultural Research 6 (17): 4034–45.

- Bobojonov, I., J. P. A. Lamers, M. Bekchanov, N. Djanibekov, J. Franz-Vasdeki, J. Ruzimov, and C. Martius. 2013. “Options and Constraints for Crop Diversification: A Case Study in Sustainable Agriculture in Uzbekistan.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 37: 788–811. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2013.775539

- Caravan.kz. 2005. V pravitel’stve budet sozdana rabochaya gruppa po zakonoproyektu “O razvitii khlopkovoy otrasli” (Government creates working group on the bill “On the development of the cotton industry)” 31.08.2005 http://www.caravan.kz/news/v-pravitelstve-budet-sozdana-rabochaya-gruppa-po-zakonoproektu-o-razvitii-khlopkovojj-otrasli-210737/.

- Collins, K. 2006. Clan Politics and Regime Transition in Central Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Cotton Outlook. 2015. Data portal at https://www.cotlook.com/.

- Craumer, P. R. 1992. “Agricultural Change, Labor Supply, and Rural Out-Migration in Soviet Central Asia.” In Geographic Perspectives on Soviet Central Asia, edited by Robert A. Lewis, 132–180. New York: Routledge.

- Dosybieva, O. 2007. “Kazakhstan’s Cotton Market.” In The Cotton Sector in Central Asia: Economic Policy and Development Challenges. Proceedings of a Conference Held at SOAS University of London 3–4 November 2005, edited by Deniz Kandiyoti, 126–132. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Gleason, G. 1991. “The Political Economy of Dependency Under Socialism: The Asian Republics in the USSR.” Studies in Comparative Communism 24 (4): 335–353. doi: 10.1016/0039-3592(91)90010-4

- Höllinger, F., and L. Rutten. 2009. The Use of Warehouse Receipt Finance in Agriculture in ECA Countries. Technical Background Paper for the World Grain Forum 2009 St. Petersburg/Russian Federation June 6-7, 2009. London/Rome/Washington D.C.: EBRD/FAO/World Bank.

- Kalyuzhnova, Y. 1998. The Kazakstani Economy. Independence and Transition. New York: St. Martin’s Press (University of Reading European and international studies).

- Kandiyoti, D., ed. 2007. “The Cotton Sector in Central Asia: Economic Policy and Development Challenges.” In Proceedings of a Conference held at SOAS University of London, 3–4 November 2005. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- KazInform. 2013. V Yuzhnom Kazakhstane nachali sazhat’ men’she khlopchatnika i uvelichivayut ploshchadi pod kormovymi kul’turam (South Kazakhstan plants less cotton and increases the area under fodder crops) 25.03.2013. http://inform.kz/rus/article/2544982.

- Lall, S. 2006. “Industrial Policy in Developing Countries: What Can We Learn From East Asia?” In International Handbook on Industrial Policy, edited by Patrizio Bianchi, and Sandrine Labory, 79–97. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Nellis, J. 2014. “Institutions for a Modern Society.” In Kazakhstan 2050. Toward a Modern Society for All, edited by Aktoty Aitzhanova, Shigeo Katsu, Johannes F. Linn, and Vladislav Yezhov, 285–310. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- OECD. 2013. OECD Review of Agricultural Policies: Kazakhstan 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2017. PSE Database for Kazakhstan. http://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm.

- Oshakbayev, D., M. Petrick, R. Taitukova, and N. Djanibekov. 2017. Kazakhstan’s Cotton Sector Reforms Since Independence: AGRIWANET Country Report. Halle (Saale): IAMO.

- Petrick, M., A. Gramzow, D. Oshakbaev, and J. Wandel. 2014. A policy agenda for agricultural development in Kazakhstan. Leibniz-Institut für Agrarentwicklung in Transformationsökonomien (IAMO). Halle (Saale) (IAMO Policy Brief, 15). http://www.iamo.de/fileadmin/documents/IAMOPolicyBrief15_en.pdf.

- Petrick, M., and R. Pomfret. 2017. “ Agricultural Policy in Kazakhstan.” Forthcoming chapter in Handbook on International Food and Agricultural Policy Volume I: Policies for Agricultural Markets and Rural Economic Activity, eds. Tom Johnson and Willi Meyers. https://www.iamo.de/fileadmin/documents/dp155.pdf.

- Petrick, M., J. Wandel, and K. Karsten. 2011. Farm Restructuring and Agricultural Recovery in Kazakhstan’s Grain Region: An Update. Halle (Saale): IAMO (IAMO Discussion Paper, 137). https://www.iamo.de/fileadmin/documents/dp137.pdf.

- Pomfret, R. 2006. The Central Asian Economies Since Independence. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pomfret, R. 2008a. “Kazakhstan.” In Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Europe’s Transition Economies, edited by Kym Anderson and Johan F. M. Swinnen, 219–263. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Pomfret, R. 2008b. “Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.” In Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Europe’s Transition Economies, edited by Kym Anderson and Johan F. M. Swinnen, 297–338. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- RFE-RL (Radio Free Europe – Radio Liberty). 2008. Central Asians Achieve Breakthrough Over Precious Resources. http://www.rferl.org/a/Central_Asian_Resources/1331903.html.

- Rodrik, D. 2007. One Economics – Many Recipes. Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rodrik, D. 2009. “Industrial Policy: Don’t Ask Why, Ask How.” Middle East Development Journal 1: 1–29. doi: 10.1142/S1793812009000024

- Roland, G. 2000. Transition and Economics. Politics, Markets, and Firms. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Ruziev, K., D. Ghosh, and S. C. Dow. 2007. “The Uzbek Puzzle Revisited: An Analysis of Economic Performance in Uzbekistan Since 1991.” Central Asian Survey 26 (1): 7–30. doi: 10.1080/02634930701423400

- Sadler, M. 2006. “Vertical Coordination in the Cotton Supply Chains in Central Asia.” In The Dynamics of Vertical Coordination in Agrifood Chains in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Case Studies, edited by Johan F. M. Swinnen, 73–114. Washington, DC: World Bank (Working Paper, 42).

- Schiek, S. 2014. Widersprüchliche Staatsbildung – Kasachstans konservative Modernisierung. Baden-Baden: Nomos (Demokratie, Sicherheit, Frieden, 212).

- Serra, N., and J. E. Stiglitz, eds. 2008. The Washington Consensus Reconsidered. Towards a new Global Governance. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press (The initiative for policy dialogue series).

- Shtaltovna, A., and A.-K. Hornidge. 2014. A Comparative Study on Cotton Production in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Bonn: Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung, Universität Bonn.

- Spechler, M. C. 2008. “The Economies of Central Asia: A Survey.” Comparative Economic Studies 50: 30–52. doi: 10.1057/ces.2008.3

- Spechler, M. C. 2011. “How Can Central Asian Countries and Azerbaijan Become Emerging Market Economies?” Eastern European Economics 49 (4): 61–87. doi: 10.2753/EEE0012-8775490404

- Stark, M. 2010. “The East Asian Development State as a Reference Model for Transition Economies in Central Asia – an Analysis of Institutional Arrangements and Exogeneous Constraints.” Economic & Environmental Studies 10 (2): 189–210.

- UN Comtrade. 2015. International Trade Statistics Database. https://comtrade.un.org/.

- Wandel, J. 2009. Kazakhstan: Economic Transformation and Autocratic Power. Arlington, VA: George Mason University (Mercatus Policy Series Country Brief, 4).

- Wandel, J. 2010. The Cluster-Based Development Strategy in Kazakhstan’s Agro-Food Sector: A Critical Assessment From an “Austrian” Perspective. Halle (Saale): IAMO (IAMO Discussion Paper, 128). https://www.iamo.de/fileadmin/documents/dp128.pdf.

- Wegerich, K. 2011. “Water Resources in Central Asia: Regional Stability or Patchy Make-Up?” Central Asian Survey 30 (2): 275–290. doi: 10.1080/02634937.2011.565231

- World Bank. 2007. Republic of Kazakhstan. Shaping Agricultural Policy in an Oil-Rich Country. Washington, D.C: Joint Economic Research Program (JERP) – The World Bank and the Government of Kazakhstan – In collaboration with USAID and FAO.

- Zinzani, A. 2015. “Irrigation Management Transfer and WUA’s Dynamics: Evidence From the South-Kazakhstan Province.” Environmental Earth Sciences 73 (2): 765–777. doi: 10.1007/s12665-014-3209-6

Appendix

List of interview partners:

I1: Representative of Kazakh Cotton Association, Shymkent, 2010.

I2: National expert on cotton pricing, Shymkent, 2012.

I3: Cotton farmer in South Kazakhstan, Saryagash, July 2016.

I4: Cotton farmer in South Kazakhstan, Orkendi, July 2016.

I5: Chief accountant of a cotton gin, Orkendi, July 2016.

I6: Cotton farmer in South Kazakhstan, Koktobe, July 2016.

I7: Representative of Kazakh Cotton Association, Shymkent, July 2016.

I8: Director of cotton processing company, Shymkent, July 2016.

I9: Representative of Regional Investment Center ‘Maximum’, Shymkent, July 2016.

I10: Private irrigation specialist, Shymkent, July 2016.

I11: Representative of South Kazakhstan water resource committee, Astana, September 2016.

I12: Senior administrator at KazAgroGarant, Astana, February 2017.

I13: Representative of the agribusiness and food processing industry department of National Chamber of Commerce, Atameken Union, Astana, February 2017.

I14: Senior manager of Republican Public Union of Farmers of Kazakhstan, Akzhaly, February 2017.

Interview notes available from the authors upon request.