ABSTRACT

This article explores the types of actions that are dramatically shaping the formation of the peri-urban economic landscape of the ger areas in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Drawing from numerous interviews and ethnographic fieldwork in and around a bus stop on the northern edge of the city, we trace the experience of two different women who each carve out a life and livelihood on this urban fringe. Examining the types of strategies they employ to secure land and employment, we argue that negotiations, speculation and enactions of relationships are vastly influential in shaping Ulaanbaatar’s urban economy from the ground up. Drawing from the anthropology of generative capitalism and the fungibility and heterogeneous nature of money, we discuss how the making of capitalist urban economies in Ulaanbaatar implicates a variety of decisions and materials, perceptions of the state, and local economies of exchange and reciprocity. Central to the shaping of these urban economies, we argue, are emerging moral quandaries and ethics arising out of these entanglements.

The peri-urban areas of Ulaanbaatar form a generative space of numerous, overlapping types of economic activities. This article explores how diverse types of strategy and decision making directly influence the formation of these socio-economic landscapes. We explore how Ulaanbaatar’s peri-urban areas form productive spaces for understanding the making of Mongolian capitalist urban economies, processes that implicate a variety of decisions and materials, formations of the state, and local economies of exchange and reciprocity. Here moral quandaries and ethics arising out of these kinds of exchanges and economic activities are fundamental to the shaping of land commercialization and political influence in the district. These economic practices, we argue, rather than being ‘outside’ of so-called ‘main’ capitalist activities in Ulaanbaatar, or part of a kind of ‘marginal’ discursive space, are instead specific aspects of the continuing formation of Mongolian urban capitalism itself.

This article explores connections between both the changing physical landscapes, the behaviours and visions of inhabitants in the district and local bureaucracy in the formation of urban economies in Ulaanbaatar. To demonstrate these interconnections, we trace the experience of two women who each carve out a life and livelihood on this urban fringe – a mother of three attempting to secure her hold over her land and access to services, and an experienced local sub-district unit leader contemplating her future in the district. In presenting the experiences of these women, we aim to reveal how particular forms of creative networks that shape Mongolian urban economies are arising out of Ulaanbaatar’s changing spaces. To explore the interrelationships between these phenomena in the making of urban economies, we draw from the anthropology of capitalisms (Bear, Ho, Tsing, and Yanagisako Citation2015; Cross Citation2014; Tsing Citation2015) as well as the anthropology of the domestication and affect of the state (Das and Poole Citation2004; Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2017) and the use of social money and strategy in relationship to exchange (Bourdieu Citation1997; Zelizer Citation1989, Citation2011).

Contextualizing capitalism in Ulaanbaatar

This paper explores the complex relationships, strategies, decision making, and favours that generate economic activity and opportunities, or even allow residents to reside in their districts or hold government administrative employment. These activities impact and shape the burgeoning land market in Ulaanbaatar, and the unfolding ‘catching-up’ of its bureaucratic infrastructure. Looking at capitalism from this perspective, we aim to direct the discussion of Mongolian capitalism in this special issue to how in the peri-urban areas of Ulaanbaatar, different actions are constantly influencing the formation of urban economic spaces, literally from the dirt upwards. Here, the decision to move a fence 20 cm, or to politely refuse a gift, can form influential actions that have a range of potential economic consequences. We explore something of the close relationship between these actions and the formation of the economy of which they are a part. The negotiation of the potential consequences that arise as a result of our interlocutors’ actions results in different types of speculative planning, moral considerations, and, in many cases, anxiety about the future.

When we discuss capitalist economic forms in this article, we are not only referring to an image of a global ‘capitalist system’ or a monolithic ‘global capitalism’. Granted, several bureaucratic instruments of land tenure and municipal administrative systems that our interlocutors engage with in Ulaanbaatar have stemmed from policies and practices developed in collaboration with organizations such as the Asian Development Bank. These were introduced during a variety of structural reforms that Mongolia has experienced since 1990 as part of larger efforts intended to instigate a free market economy (Sneath Citation2001, 42). However, these instruments now form only one small part (and often a problematic part) of the myriad number of economic decisions made and actions taken by the women we discuss in this article. We will look at how these decisions and actions shape what capitalism in Ulaanbaatar is becoming, highlighting them as fundamental in making the urban economy.

Here there are processes at play that are complex and innovative. In these economic spaces, people not only rely on money or documents (though these are important) but also on fences, concrete, favours, speculative planning techniques, power struggles and conflict, and forms of strategic planning. This article examines of some of the collaborative, contaminative encounters these techniques and elements give rise to (Tsing Citation2015, 27–29), which can become ‘recoded in new commercial forms’ (Humphrey Citation2017, 53). It aims to highlight the significance and downright necessity of ‘taking advantage of value produced without capitalist control’ (Tsing Citation2015, 63). In this sub-district of Ulaanbaatar, accumulation is not companies gathering or attracting human labour, or large conglomerates mining for raw products like coal, but residents buying wood or gathering old car tyres to build fences and claim areas of land. Doing a favour for someone, or accepting or refusing a bribe in the course of one’s employment in the local municipal administration, form enactions of social relationships. Here, these kinds of actions become ‘reciprocally interactive and mutually constituting’, where capitalism ‘is immanent in human action’ (Cross Citation2014, 7; see also Bear et al. Citation2015). These social processes that have economic consequences are by their very nature precarious (Tsing Citation2015), and are largely formed of changing relationships.

Reconsidering Ulaanbaatar’s ‘margins’

The word ‘margins’ is highly problematic when considering the urban make-up of Ulaanbaatar. Expanding out from the built core of the city, well beyond the reach of core infrastructure, is a peri-urban area that largely consists of allotments of land on which people live. However, this ‘peri-urban’ area now constitutes roughly 83% of the residential land in the city (World Bank Citation2015, 1). We are attempting to release the so-called ‘marginal’ (economic) behaviour or ‘informal’ sector ‘from singularity and subjection’ and make it ‘visible as a differentiated multiplicity’ (Gibson-Graham Citation1996, 16) by looking at the ways different activities and resources are hugely influential in forming and continually remaking the capitalist fabric of Ulaanbaatar in the emergence of different employment opportunities, or the shaping of Ulaanbaatar’s land market. Here, assemblages of different economic actions, phenomena and collaborations ‘cannot hide from capital and the state’ and form ‘sites for watching how political economy works’ (Tsing Citation2015, 23).

Expanding out from the primarily ex-socialist built core of the city, 83% of Ulaanbaatar’s land area is currently made up of what are described as ger districts (ger horoolol, see ), which consist of square, fenced allotments of land, often including a small house, sometimes self-built, or gers, the white, felt, collapsible dwelling used by Mongolian mobile pastoralists (World Bank Citation2015, 1).

Figure 1. An example of Ulaanbaatar’s sprawling ger districts, which span out from the core of the city. Photo: T. Bayartsetseg, 2016.

Since the end of socialism in 1990, there has been a rapid influx of people moving to Ulaanbaatar to seek out better economic opportunities and access to healthcare and education. The increasing privatization of urban land since 1990 and the fact that Mongolians registered in Ulaanbaatar are technically each entitled to 0.07 hectares of land has created two overarching property regimes in the city. Residents who are eligible are first able to register for temporary possession of land (ezemshil), and, after five years, can apply for outright ownership (ömchlöl). However, the steady influx of people into the city, and the increased movement of people between different areas of Ulaanbaatar’s ger districts, has meant that the city’s population is rapidly exceeding the capacities of the bureaucratic infrastructure that applies Mongolia's urban land tenure systems (Miller Citation2017).

The legal and bureaucratic ‘path’ (or paths) to acquiring possession and ownership rights is often fraught with difficulty and inconsistencies. For many it is often a convoluted, unclear process that can manifest in a variety of ways and techniques that are not always fully known by many of the people trying to legally secure their land (Byambadorj, Amati, and Ruming Citation2011; Højer and Pedersen Citation2018; Miller Citation2017; Pedersen and Højer Citation2008, Plueckhahn Citation2017; World Bank Citation2015). People often set up hashaa (fences) to cordon off a section of land for their use and then apply for permission, the first step towards applying for temporary possession. Due to a broad range of factors however, many people currently acquire and live on land in Ulaanbaatar without gaining (or being able to gain) either temporary possession or outright ownership. People can live in this situation for many years, making this a continually unfolding situation rather than a temporary lack of bureaucratic legitimacy (Miller Citation2017).

The ger areas of the city are divided into three geographical sections: central, middle and peripheral (City Mayors’ Office Citation2014). The ger area where we conducted our research is in the middle zone, in accordance with the Development Strategy for Ulaanbaatar City 2020 and Development Trend till 2030 (City Mayor’s Office Citation2014). In this development strategy, the Ulaanbaatar City Municipality plans to disperse the population density of the city into the middle zones in order to prevent overloading of public services. But despite these plans, not much has been implemented since 2014 due to a severe economic downturn that has significantly affected the municipality (City Mayor’s Office Citation2014; Lkhagva Citation2017). Currently, several projects are in various stages of planning and early implementation for the setting up of micro-hubs in the ger areas, to bring services to these areas and help disperse population density throughout the city (Lkhagva Citation2017). The municipality’s consistent lack of funds, combined with a lack of local urban planning, and significant political and bureaucratic turnover in the city administration after each four-year election cycle, has only compounded and exacerbated this situation (Byambadorj, Amati, and Ruming Citation2011). With an overall lack of infrastructure development, residents in ger areas still warm their homes by burning coal in winter, and about 97.3% use pit latrines in the absence of plumbing and running water.

The larger district where we conducted our research consisted of 6 sub-districts in apartment areas (central ger areas) and 13 in ger areas. It is one of the most densely populated districts in Ulaanbaatar (Statistics Bureau Citation2015). Lately, according to the district statistics bureau, the district territory has been extended further north of the city, with its total population reaching 159,514 (Statistics Bureau Citation2015). Crime is most prevalent in this district, with about seven crimes reported daily (Statistics Bureau Citation2015). In the ger areas, residents lack proper roads, footpaths, footbridges, and adequate drainage, as well as running water and heating (Ger Area Development Bureau Citation2007; UN Habitat Citation2010). Access to kindergartens and public schools is also limited, especially in the newly extended northern side of the district (Vanderberg Citation2013). Communicable diseases are common in this district due to its population density, outnumbered health clinic services, and poor sanitation.

The sub-district

This article draws from ethnographic research undertaken primarily in one horoo, an administrative sub-district in the northern reaches of Ulaanbaatar. We focused our research in and around a busy bus stop that formed the third-to-last stop and one of the last major hubs of stores and services on a newly asphalted road stretching out from the centre of the city. Surrounding this bus stop were several small stores (delgüür) selling a variety of foodstuffs, from which people can buy goods or get them on credit. There is also a small café (guanz), a pharmacy, and a mobile library for children. This transport hub is almost always busy, with buses coming and going every 10 minutes, taxis and minivans (microbus) offering their services, and people milling about talking ().

Figure 2. The bus stop in the north of the city in June 2016. Here, people are campaigning for a political candidate during the lead-up to Mongolia’s national parliamentary elections on 29th June. Photo R. Plueckhahn.

This transit hub is an important place where people can receive and exchange different types of information, from buying and selling land, to finding out about opportunities for temporary employment. For example, one day we saw an interlocutor of ours walking through the bus stop area saying that he was waiting and watching for the big coal trucks to arrive, hoping that he could secure a day’s temporary work unloading and bagging coal to be sold to households for heating. The bus shelter itself was a place where people advertised land that was available to buy, rent, or be ‘shared’ (ail buulgana), as well as advertising other kinds of goods and services and types of temporary employment opportunities ().

This road courses its way between two small rising hills away from the city. Many land plots have been set up so they span out from this asphalt road. The road itself forms an infrastructural ‘lifeline’ to the centre of Ulaanbaatar, making it far more accessible to those in this district than it was in the past.Footnote1 Because of this, plus the local economy springing up around the bus stop, the land was more valuable the closer it was to the road. The road itself has a kind of ‘gravitational pull’, as people set up hashaa fences as close to the road as they can. As the hills arch up away from the roads, land plots became sparser, and during our fieldwork the half-built sections of new hashaa fences could be seen in development.

Our work explores the interrelationships between the road, the physical landscape surrounding the road, its inhabitants, and the lowest-level horoo district city administration connecting this district into a larger bureaucratic framework. Drawing on our combined research expertise in sociology, social work and anthropology, we conducted a mixture of participant observation fieldwork and structured and informal interviews over the course of our research, which we conducted gradually in September–November 2015 and April–August 2016. In this paper, we draw from numerous interviews and ethnographic fieldwork in and around people’s homes, the bus stop and the horoo office that overlooks the district from a nearby hill.

This sub-district of Ulaanbaatar has seen its fair share of new arrivals. Over the course of our research, we saw what were once bare hillsides gradually taken over by people setting up new land plots. As the landscape changes over time, so too do the bureaucratic responsibilities of the local district’s unit leaders (hesgiin ahlagch) employed to work as liaisons between horoo employees (such as welfare officers) and district residents. Unit leaders are the main channel for the horoo office to distribute information to its residents, including information on social and economic programme updates and public events. They play a crucial role in distributing information to residents in their area, as well as promoting civic participation in community campaigns such as organizing collective cleaning days and collecting household data for the city’s welfare programme. As the main outreach people in the horoo, unit leaders are further required to highlight households who are in need of bank loans and people who could qualify for welfare payments and send this information to the horoo office. They can also nominate citizens for local or district awards (People’s Representative Hural Citation2016). Because of their knowledge of and reach to residents, they have to negotiate considerable political pressure from different people. Unit leaders are supposed to look after approximately 150 households each. Now, in this rapidly expanding northern district, some unit leaders look after approximately 400–450 households, which one person acknowledged to us to be an almost impossible task. We now turn to a discussion of how people negotiate this landscape, drawing from the experiences of two women that exemplify the interrelationships that emerge in the formation of urban economies in this area.

Economic landscapes

NaraaFootnote2 is a woman in her early thirties who has three young children, one just a year old. She lives with her children and husband in a small ger on a plot of land. This plot of land is located on the start of the steep rise of one of the hills parallel to the asphalt road running through the sub-district. Her journey towards finding and accessing this land reveals a trajectory of colliding, overlapping strategies and ‘future-oriented’ practices (Cross Citation2015) that she has artfully interwoven in order to gain a foothold in Ulaanbaatar’s land market. However, gaining this foothold is still an ongoing process. Naraa has been living on this piece of land but is still to gain five-year possession rights.

Naraa’s move to the sub-district on the edges of the city formed part of a larger vision that she had for her and her family’s future. Naraa has lived in Ulaanbaatar since she was seven.Footnote3 Now 31, she and her children and husband had previously lived in a ger area closer to the city centre, which she described as extremely overcrowded and close to a cemetery. In that previous location, Naraa lived in one plot of land together with three other families. In this crowded area, she said that her husband fell under the influence of ‘bad people’ and often went out drinking. In the new location, she said her husband drank less, and they were away from a lot of the pressures of these crowds with ‘bad energy’. She described this area of the city as clean, spacious and ‘separate’ (tusdaa). Her husband now takes on numerous odd jobs in the sub-district and other areas of the city; where, she stated, ‘he doesn’t sit unoccupied but doesn’t have a steady job, either’.

A lot of this family’s day-to-day life is infused with a sense of precarity. Naraa and her husband engage with this unstable economic environment by speculating on and engaging in different seasonal opportunities, such as the collecting and selling of pine nuts (samar tüüsen) during the middle to end of summer. Their current way of living is based on temporary economic opportunities, including seasonal jobs and using ecological resources for sale. Her husband’s temporary work opportunities arise out of enacting different relationships at different times. Sometimes the timing of these endeavours does not match the financial needs of the family: in late August 2016, Naraa was worried that the pine nuts were ripening much later in the season, leaving her without enough money for when her children started school. Speculation about different possible opportunities and commenting on possible collaborations and activities with different people formed a large part of Naraa’s life in the area, strategies that also encompassed access to land.

Concrete, cadastral maps, and conflict

While Naraa and her family live on a piece of land near the road, their hold on this land is tenuous and ongoing. When they first arrived in this area, five years ago, she said, there were hardly any land plots. However, their modest section of land is now surrounded by other fenced land plots. Naraa has yet to gain possession rights (ezemshih erh) of her land because she and many other landholders surrounding her cannot get a cadastral map of their land approved by the district land office. In Spring 2016, she speculated to us that this might be due to the ‘altitude, steepness and lack of car access’ that characterize this area. But she acknowledged that if she registered the right cadastral map it would give her legitimacy and thus leverage over her acrimonious neighbours, who were threatening to encroach upon her land. Her neighbours, Naraa said, had for a long time been speaking ‘as if all the nearby areas belong to them’. She described not having possession rights as humiliating (deerelhüüleh). However, without an approved cadastral map she would be unable to obtain them.

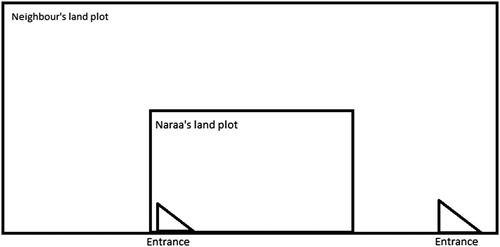

In the meantime, as the summer of 2016 progressed, Naraa’s hashaa became embroiled in an even deeper conflict with her neighbours. By this stage, Naraa’s neighbours had managed to expand their plot of land by moving their fences until Naraa’s land was surrounded on three sides ().

Figure 4. By October 2016, Naraa’s land was almost completely subsumed by her neighbours’ land. Her only free-standing side bordered the dirt road that wound between blocks of hashaa.

The fences of both parties’ land were not necessarily fixed in any way, but always movable, forming ‘volatile and fleeting stabilisations of an inherently emergent reality’ (Højer and Pedersen Citation2018). The engulfing nature of the neighbouring hashaa formed a physical manifestation of the types of ‘tension’ (zörchil) that were emerging as a result of the close proximity of these two families. These two families were trying to best stake a claim in the emerging land market in the absence of either of them holding land tenure. This underlying tension quite often spilled over to arguments (margaldaan) and on one occasion cursing (haraah), which Naraa blames for the recent death of her aunt, who used to live near Naraa in this sub-district. Naraa increasingly found herself caught in a bind. The land office stated they would not register her land or certify her cadastral map until she sorted out the conflicting claims and disagreements with her neighbour over the sizes of their respective land plots. Added to this was the actual stalling of any further land registrations during the summer of 2016 by the Ulaanbaatar municipality due to administrative changes occurring after the city-wide elections on 29 June 2016.Footnote4 The municipal land office was thus silent on this issue, and it was unclear when applications for possession rights would again be processed. It is a high-stakes situation. In the absence of state involvement, people, as Naraa put it, are ‘tomhon shig zurag avahuulchih geed l’ (trying to get a map for a larger piece of land). While the landscape is ambiguous, people become land prospectors against each other, trying to stake the biggest claim first.

Instead of following up maps or chasing bureaucratic steps, Naraa reverted to other means to secure her land. As we visited Naraa over the course of the summer of 2016, we noticed she had made considerable investments in settling on the land more permanently. She and her husband poured a half-metre-high concrete base, which provided a solid and stable level for their ger on this sloping piece of land. They bought a new ger, and also erected a brand-new, solidly built wooden fence. None of these endeavours would have been cheap. Instead, they formed incremental steps for the slow incorporation of this land into Ulaanbaatar’s continually burgeoning land market (Miller Citation2017, 16-17). By setting it up physically in a more unequivocal way, the concrete and the fence were material goods that Naraa had acquired ‘for capitalist accumulation’ (Tsing Citation2015, 63), for an as yet unforeseen future when this land becomes a form of capital that Naraa can sell for a profit. It is the slow, burgeoning formation of a distinctive type of market in which ‘affordability accrues through the absence of formal planning and regulation’ (Roy Citation2005, 149).

Accumulation and the creation of Ulaanbaatar’s land market

With the state’s inability to fully reach this burgeoning landscape, other instruments become catalysts in the creation of Ulaanbaatar’s land market. Concrete and fences become the ‘“noncapitalist elements” upon which not only land holders depend (Tsing Citation2015, 66). The market itself is being shaped by these elements through proportions of people creating fiscal entities over time, slowly commercializing Ulaanbaatar’s surrounding land (Miller Citation2017). Added to these ‘instruments’ is the tension or conflict shaping the bringing of land into being as assets. The hashaa fences work simultaneously as protective devices as well as tension-creating entities. People’s presence on the land is what holds the land in place, with neighbouring households creating tension over land with competing claims. Some take advantage of this gap in governmental rule enforcement, using it as part of their strategy to obtain more urban space, and thus a bigger stake in the land market and the potential future value of land. These actions influence the market value of land in the area. It was understood among our interlocutors that a large parcel of land containing space for two or three land plots was worth approximately 10 million tögrög (roughly USD 4100) – no small amount. Naraa tries to avoid argument, for the sake of her young children’s well-being, but at the same time tries to reach a consensus over how much land the neighbours could possess and how they can all maintain open access to their land for emergency services. She thinks of escaping from this tension by searching for another parcel of available land nearby, although she says this too will be difficult. She finds a way to create her own infrastructure in the absence of state oversight over land use, envisaging that government officials will eventually recognize the households that have already started building their own environment.

It is Naraa’s ability to negotiate relationships around her that makes it possible for her to live in this space. Because she often misses official information from the horoo office and information from land officers when it becomes available, the only way she can work with the tension between her and her neighbours is through negotiation. Naraa bolsters her situation by creating positive networks among other families nearby, forming types of ‘relational infrastructures’ (Simone Citation2015) that allow her to access services she could not otherwise get. This can be seen in the way that Naraa accesses electricity. Currently, Naraa cannot get her own electricity distribution post until she has possession rights to her land. In the meantime, a family nearby distributes electricity to several other families, including Naraa, through a bundle of wires set up between land plots ().

Figure 5. Wires providing electricity to land plots near Naraa in the sub-district. A common site in the ger districts, electricity is siphoned off a family’s registered distribution post and distributed to other families, often for a small profit. The bundles of wires reveal the multiple, interconnected, relational infrastructures underpinning this so-called ‘informal’ access to electricity. Photo: R. Plueckhahn, 2016.

The ‘distributing’ family extends their electricity to families on three other land plots. However, Naraa acknowledges that the two of these families cannot pay their bills, making it difficult for the distributor and for her. Naraa is locked into an uneasy alliance with these families, borne out of necessity and resourcefulness in this changing landscape. For Naraa, arranging to compensate her neighbours for siphoning off their electricity is not purely a finished ‘transaction’ with a service provider. After all, she found her electricity through creating ties with particular networks in a landscape fraught with social conflict. However, on the other hand, it is not purely an ‘enaction’ of close ties, borne out of obligation and ensuing gratitude. Naraa is expected to give money in return. Her access to the essential electricity shows the uneasy balance of precarious alliance and pressured transaction borne out of necessity that can be found in the local economy in the area. While she is grateful to have the access to electricity, she worries that the providing family is asking too high a premium. Several people we spoke to speculated on how much more expensive it was to access electricity siphoned through by families rather than through a distribution post on one’s block of land. Without the security of land tenure, Naraa was forced to negotiate survival networks that come with different pressures, obligations and transactions in a morally (and physically) ambiguous landscape that is hard to map.

The unit leaders

Scaling upwards from land itself, navigating these opaque socio-economic entanglements is a skill required of various other people living in the district. This can be especially seen in the overworked bureaucrats required to oversee the social expansion on Ulaanbaatar’s urban fringe.Footnote5 We now turn to a discussion of Chimgee, a unit leader, or hesgiin ahlach, employed in the local horoo office. Chimgee has lived in the area a long time and has the dual perspective of being a resident as well as a state representative. In this section, we move away from direct monetary or land-related perspectives of local economic interaction to focus on the other skills required for navigating this landscape: the ability to assess different types of gifting, exchange, and political alliances. Stemming from numerous conversations and time spent with Chimgee, we draw from her own description and self-presented accounts of her experiences living and working in the district. The ability to navigate the different types of gifting, exchange, and political alliances, allows Chimgee to keep her job, and in turn, allows her to continue her life in the sub-district. Here, the boundaries between state reach and socio-economic landscape become intermeshed and blurred.

Chimgee is one of the longest-serving unit leaders in this sub-district, where she has dedicated 13 consecutive years of service to the horoo. The state bureaucracy in Ulaanbaatar is highly political, and it is a common perception that bureaucrats are replaced each time a different political party gains power. That Chimgee has kept her job for so long and weathered so many political changes, as well as that her job is of a low status (and is not highly sought after by other people), is testament to her skills at negotiating different political environments and changing relationships. Her in-depth and long-term knowledge of the district is an essential asset to any newly politically appointed local darga (leader). Unit leaders are the main channel for the horoo office to distribute information to its residents, including information on social and economic programme updates and public events. Because of their knowledge and reach to residents they have to negotiate considerable political pressure from different people.

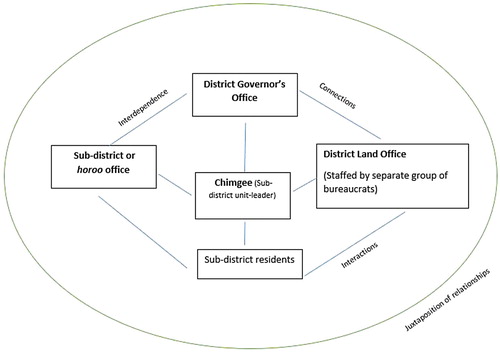

While a unit leader works under the direct guidance of the head (darga) of the horoo, they are contracted by the administrative office of the district governor (People’s Representative Hural Citation2016). Therefore, Chimgee always needs to independently maintain and foster political relationships with both of these administrative offices. This creates networked bureaucratic fractals between which Chimgee independently fosters her own relationships with the local leader of the sub-district as well as the leader of the district (Jensen Citation2007) (see ).Footnote6 This allows her a small, unstable degree of political manoeuvrability and opportunity as she negotiates her position and attempts to access resources for the district. Unit leaders are not considered full ‘public officers’ but ‘contracted officers’, whose contracts are extended based on performance evaluations.Footnote7 This results in Chimgee’s status being a fragile one.

Figure 6. A diagram of the different bureaucratic fractals with which Chimgee has connected herself. This gives her an expanded network and a greater amount of political alliances beyond the sub-district leader.

Chimgee is a mother of two, and also provides home care for her sick mother-in-law. While she has a steady job, she struggles to makes ends meet, as her pay is low. Chimgee has been living in this area for 20 years, yet her family has not yet managed to legally possess a piece of land. Instead, her family rents a ger in a small plot of land owned by another individual. This highlights something of the contradictory nature of her life in the district. While she holds a degree of influence in the sub-district office, she herself is forced, like all other residents, to deal with the separate land office in a different area of the district staffed by a different set of bureaucrats with a different set of political alliances and obligations.

Making bureaucratic connections

The day-to-day experience of this unit leader reveals the fluidity of relationships that emerge in this area as Chimgee liaises between the community and the local administration. Chimgee often ‘wears two hats’; she is often required to work with both community members and public officials to create better social relations and advocate for changes that will improve the built environment in the sub-district. As part of the community, she is engaged with households on a daily basis. Residents of this targeted area, especially those who have settled here within the last five years, experience social exclusion from services and face barriers to social participation irrespective of their willingness (Terbish and Rawsthorne Citation2016). These social and relational aspects of Chimgee’s work form a fundamental part of the bureaucratic interface she represents, in which she moves across and between overlapping systems of relationships (Jensen Citation2007). Chimgee’s daily work includes meeting with people and disseminating city government information, and delivering residents’ concerns to the local administration. She often acts as a broker between these two spheres, translating the demands of one side to the other. This brokerage largely occurs through interpersonal relationships, and much of her work takes place away from the horoo office itself.

With her in-depth knowledge of the district and her access to residents’ civic information, as well as the civic information she has access into, Chimgee acts as an advocate, representing residents in their call to improve infrastructure and make decisions for area development. For Chimgee, working as a unit leader produces different kinds of capital and value (other than the more quantifiable capital of money) that is made up of social commodities, such as social networks and access to information. Chimgee, as Gaventa (Citation2006) described, is an example where power is being created, shared and used for others’ well-being, where she can influence how the presence of the state is reconfigured in the sub-district (Das and Poole Citation2004, 19). Chimgee artfully negotiates with local bureaucrats of different political affiliations, using her position to connect different bureaucratic offices.

As an experienced unit leader, Chimgee is often requested to accompany state officials when they arrive to conduct local situation analyses.Footnote8 Here she can inform officials of people’s living conditions to encourage decisions such as adding streetlights and fixing roads in some parts of the target area. However, because her negotiation and tactics are effective, she is often the target of suspicion and jealousy from others, because people suspect her of aligning with one political party or individual political candidate. For her to do her job, she also needs to navigate this climate of suspicion, political intrigue and suspected corruption. Just like the ‘survival networks’ Naraa needs to negotiate to keep her access to electricity, so too does Chimgee need to negotiate a constantly unfolding and changing social landscape to do her job.

The fungibility of money and feelings of indebtedness

This creates an uneven and morally ambiguous environment for Chimgee to negotiate. She attempts to engage with different stakeholders from different spheres of the city to try to gain infrastructural improvements for the area through interacting with different social, fractal scales and influencing the mobilizing of social forces (Wagner Citation1991, 159). However, as she goes about her work, different levels of social indebtedness occur through types of gifting and exchange that move beyond money or something directly quantifiable. Indeed, money itself in this context has diverse qualities and is shaped by social processes. It is heterogeneous and fungible with other types of gifts and favours (Zelizer Citation1989); but the direct equivalences of fungibility between say a gift and an amount of money are murky and unclear. In conversation with us, Chimgee spent much time musing on particular dealings and exchanges she witnessed or had became embroiled in. She described the circulation of favours that were done, as she described, ‘out of gratitude’. She contrasted this by condemning the gifting of cash by political candidates before elections as immoral, because they ‘use taxpayers’ money to do so’. She viewed the amount of cash as indicating the value the giver put on the receiver’s life: ‘hün yeröösöö l havtgai möngö bolchihoj’ (essentially, a person has become money).

Chimgee’s distinctions between gifts and bribery align with those made by Sneath (Citation2006). Sneath describes and contrasts the Mongolian definition of corruption (avilgal) and bribery with gifting where he says the latter creates senses of ‘obligation’ rather than ‘reciprocity’ (97–98), which has a longer timescale and doesn’t have such a direct equivalence. Considering Chimgee’s experiences allows us to take these distinctions and look at how people navigate between these different parameters. For Chimgee, while these distinctions in speech were somewhat clear, the daily negotiation and discernment of the distinctions between a gift or a bribe were not. Chimgee discussed how one person’s gifting out of gratitude could easily be viewed by another person as bribery and corruption. For her, it was always difficult to tell whether accepting a gift would create good relationships or align her politically in ways she did not want. She acknowledged that in this environment it was impossible and ‘not necessary to be favoured by everyone’. It was this navigation and discernment that Chimgee had become skilled at that allowed her to do her job.

Chimgee was often confronted with challenging offers from political party affiliates and some public officials. For instance, on one occasion she was offered a medal by an official for an achievement she was not aware of. Accepting offers such as a medal or, on rare occasions, cash for registering residents during an election campaign, while potentially having some benefits, could leave her indebted to the wrong people. Due to what she feels are the unprofessional approaches of some officials, she was often worried that her motivations might be misinterpreted if she was seen talking to political party affiliates. Here actual avoidance becomes an effective coping technique for her to navigate this socio-economic landscape. Talking with Chimgee at the busy bus stop during the election campaign season in June 2016, we were deep in conversation, when through the array of people Chimgee spotted someone politically aligned that she did not want to see. She quickly exclaimed, ‘I need to go!’ and darted away through the disparate crowd to disappear behind a building.

Chimgee also felt pressure from residents of the sub-district. Some households try to reciprocate Chimgee’s assistance by offering types of fungible returns and goods, including lunch, tea or sharing wine. However, some invitations and sharing have possible clandestine implications: people may be angling for an advantage in some way – socially, politically, economically, or all three. Some families invite their unit leader for a meal to request assistance accessing social welfare programmes, a valuable resource from which many are excluded. Even though as a unit leader she is not in charge of the final decision on welfare applications, a boundless circle of social indebtedness is created in which Chimgee feels in some way obligated regardless.

When gifts are used as a substitute for money in order to produce obligations (Guyer Citation2012), it puts Chimgee in a moral dilemma. She feels caught between a personal feeling of disgust towards the act of gifting, but, on the other hand, feels bound by the gift to encourage favourable decisions. It is extremely difficult for her to quantify this ‘multiplicity of socially meaningful currencies’ (Zelizer Citation2011, 138). Even when she understands that ‘gratitude’ is an important motivation for gifting, she is constantly wary of the possible types of ‘mental accounting’ (Zelizer Citation1989, 350) that can occur when someone gives her a gift. While ambiguous, she suspects that notions of equivalence might exist. Such expectations of equivalence can be seen in the Mongolian proverb, ‘ayagani hariu ödörtöö, agtny hariu jildee’ (give someone a meal, they'll pay you back in a day; give them a horse, it will take a year).

Speculation and the making of urban economies in Ulaanbaatar

Whether one considers the use of and hold on land, or a bureaucrat trying to maintain some type of political status quo in order to keep her job, the physical landscape itself is complicit on both accounts. There is a great deal of confluence and overlap between the politics of the emerging land market, emerging economic actions, attempts to govern this landscape, and the land itself. While she was not in charge of issuing land, Chimgee reflected that state officials are more popular if they (illegally) help people get land tenure. On another occasion, we spoke to a shop owner whose shop sat alongside the busy paved road with a good view of the surrounding land plots. The shop owner said that while she worked, she watched peoples’ behaviour as they moved about the landscape and only gave goods on credit to those she knew weren’t temporally renting (türeesleh) someone else’s land. The effects of observations, speculation and decisions were not seen by our interlocutors as by any means limited to the ger area in which they live. Instead, they viewed themselves as interlinked with a wider Mongolian capitalist economy, in which ambiguity and ethics played a prominent part. For instance, Naraa speculated to us how sacred land close to Bogd Haan Mountain on the southern edge of Ulaanbaatar was now taken and owned by politicians. She found this ironic given that so much criticism was placed on the people in the ger areas who took land on the sides of mountains.

Navigating the murkiness between ‘transactions’ versus ‘enactions’ and favours produces particular spaces in which morality and ethics play an extremely important part (Makovicky and Henig Citation2017). Naraa and Chimgee’s experience of the emerging economic landscape in the district is one of intense speculation (a form of uncertainty and guessing about the future) and watching, in order to take the best course of action. For them, decisions that have economic repercussions are often heavily tinged with moral questions for which there are no easy answers. They form types of moral quandaries which produce stress and anxiety about the future. It is these emotional undertones influencing peoples’ economic decisions in both land and the economy that shape experiences of capitalism and their political materializations (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2017, 7). These questions and quandaries form a vital part of how the economy is made: through forming part of the creation of capitalist goods, and the monetary values placed upon them. This expands out from the ger land plots themselves to the valuations (monetary and otherwise) placed on urban land, and the formation and governance of this changing urban landscape.

The experience of this unfolding landscape is countered by another concurrent phenomenon. In the context of changing relationships, where it is hard to tell the difference between a ‘transaction’ or an ‘enaction’, and with the fungibility of money with other types of less quantifiable favours, gifts or infrastructural access, there is in our interlocutors an anxiety about the possible obligations each type of favour or gift might engender. In this anxiety is an extreme wariness or fear about possible ‘equivalences’ people might associate with different types of arrangements or exchanges. What would the presentation of a prestigious award to Chimgee, say, equate to in terms of a possible return she would be expected to make? The fact that many of these equivalences are essentially unknowable but will possibly arise out of future enactions only compounds the uncertainty experienced by these two women. As they know too well, this urban space is not only a place for social relationships but also a terrain where various strategies clash. Because of this, the uncertainty surrounding forms of exchange itself modifies peoples’ practice (Bourdieu Citation1997, 191): Naraa and Chimgee engage in complex and constant speculation about people’s motivations, actions, and possibly equivalences and obligations arising out of different relationships.

Conclusion

When considering this interrelationship between the use of land, the economy of political favours and attempts to govern this landscape, a complex picture emerges of what constitutes continually emerging capitalist practices in Ulaanbaatar’s urban economy. In contrast to the socialist period, the post-1990 free movement of people and emerging legal processes of land commercialization have given rise to a varied and volatile land market and accompanying conflicting strategies and socialities. The economized political landscape that Chimgee negotiates forms yet another unfolding substantiation of peoples’ relationship to the state in this environment of fluctuating commercialization (of land and, indeed, economization of relationships). Here forms of equivalence, expected returns, the fungibility of money and reciprocal relationships are ambiguous and difficult to negotiate. This sub-district in its entirety forms a kind of emerging market that is partially ‘in waiting’, where items foundational to Ulaanbaatar’s capitalist economy (land, fences, political connections) are used in the present, in the hope that they could be capitalized on in the future on some as yet unforeseeable date. The ‘encounters and entanglements, connections and frictions’ (Cross Citation2014, 8) that form these interlinked processes are exactly experiences of the specificities of capitalism in Ulaanbaatar today, a capitalism that relies on the interconnection between the domestication of infrastructure, reliance on social networks and the personalization of the state.

This all highlights just how integral the myriad social relationships are in making the urban fabric of Ulaanbaatar today. In this space it could be said that the negotiation of these uncertain parameters by Naraa and Chimgee form types of coping which lead to forms of resilience. Here we can see emerging discourses of dissent and practices of resistance people use to manoeuvre their resources (Lister Citation2004; Woliver, Citation1996). They form clear examples of how in the ger areas, people seek practices to secure themselves in insecure economic situations with an absence of state interventions for improvement (Evans and Reid Citation2014, 77). Here, individuals are demanding their ‘right to the city’, a demand for political, social and economic recognition (Butler Citation2012, 144), in a changing, commercializing environment. By looking at this space through a holistic lens, one that takes into account the interrelationships between land markets, varied economic practices in daily life, and emerging moralities, one can gain a sense of the complexity of urban capitalist experiences in Mongolia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Rebecca Empson, Dr Dulam Bumochir, and Elizabeth Fox for comments on earlier drafts. We also thank Setsen Altan-Ochir for her valuable assistance in translating interview transcripts. Each author contributed equally to the production of this research. We sincerely thank the many different people who all gave their time discussing their experiences of living in Ulaanbaatar.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The road that connects this district to the centre of Ulaanbaatar was built in 2009 with local funding from the District Governor’s Office. Such an initiative is indicative of how the Ulaanbaatar municipality has shifted in its perception of the ger areas: moving from seeing them as an informal aberration to a vital and ‘permanent’ part of the make-up of Ulaanbaatar.

2 All names included in this article are pseudonyms.

3 Naraa’s experience of having lived in the ger areas of Ulaanbaatar a long time and having moved between different areas was a common one. A lot of people we met on the urban ‘fringe’ had moved there from other crowded areas within the sprawling ger areas. This in some way problematizes the idea of what exactly constitutes a rural-to-urban migrant in Mongolia, given that there is so much movement back and forth between rural and urban areas, and so much movement within the city itself.

4 In the lead-up to the elections on 29 June 2016, all land registration and issuing of temporary possession certificates were paused. Interlocutors speculated to us as to when applications would be received again, saying it was likely to resume only for two-week periods on and off during the rest of the calendar year.

5 For an ethnography of the role of bureaucrats, welfare provision and and ethics of care in Ulaanbaatar's ger areas, please see the forthcoming PhD thesis by Elizabeth Fox “Between Iron and Coal: Networks of care and obligation in the ger districts of Ulaanbaatar” (working title) University College London.

6 In describing bureaucratic ‘fractals’, we are drawing from Jensen (Citation2007, Citation832), who describes a fractal approach as consideration of how different bureaucratic ‘levels’ each have their own complexity. He advocates this approach as more sensitive to heterogeneity and variability than ‘micro’ or ‘macro’ perspectives. In this, the different ‘places and people are variably connected’, and ‘actors engage in a constant deployment of their own scales’ (833). In highlighting Chimgee’s connections between different municipal scales, we are highlighting the potential variability in the manifestation and use of these different politically aligned relationships.

7 Unit leaders are contracted by the District Administrative Office. Other officers employed at the horoo office are officially considered public service offers in accordance with the Law on Civil Service in Mongolia.

8 Situation analyses are often conducted by elected parliament members to assess community demands. They also allow international organizations to get acquainted with local conditions and administrations and to update their local data on Ulaanbaatar.

References

- Bear, L., K. Ho, A. Tsing, and S. Yanagisako. 2015. “Gens: A Feminist Manifesto for the Study of Capitalism.” Cultural Anthropology Website. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/652-gens-a-feminist-manifesto-for-the-study-of-capitalism.

- Bourdieu, P. 1997. “Selections from The Logic of Practice.” In The Logic of the Gift – Toward an Ethic of Generosity, edited by A. D. Schrift, 190–230. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Butler, C. 2012. “The Right to the City.” In Henri Lefevbre Spacial Politics, Everyday Life and the Right to the City, edited by C. Butler, 133–160. NY, USA: Routlege.

- Byambadorj, T., M. Amati, and K. J. Ruming. 2011. “Twenty-First Century Nomadic City: Ger Districts and Barriers to the Implementation of the Ulaanbaatar City Master Plan.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 52 (2): 165–77. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8373.2011.01448.x.

- City Mayor’s Office. 2014. Development Strategy for Ulaanbaatar City – 2020 and Development Trend Till 2030. Ulaanbaatar: City Mayor’s Office.

- Cross, J. 2014. Dream Zones – Anticipating Capitalism and Development in India. London: Pluto Press.

- Cross, J. 2015. “The Economy of Anticipation – Hope, Infrastructure, and Economic Zones in South India.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (3): 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-3426277.

- Das, V., and D. Poole. 2004. “State and Its Margins – Comparative Ethnographies.” In Anthropology in the Margins of the State – Comparative Ethnographies, edited by V. Das and D. Poole, 3–33. Santa Fe: SAR Press.

- Evans, B., and J. Reid. 2014. Resilience: The Art of Living Dangerously. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Gaventa, J. 2006. “Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis.” IDS Bulletin 37 (6): 23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x

- Ger Area Development Bureau. 2007. Ger Areas in Ulaanbaatar: Current State and Issues Faced (Report prepared for the Citizen Representative Assembly, for an approval of ger area development strategy). Ulaanbaatar: Ger Area Development Bureau.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (as we Knew it) A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Guyer, J. 2012. “Obligation, Binding, Debt and Responsibility: Provocations About Temporality From Two New Sources.” Social Anthropology 20 (4): 491–501. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2012.00217.x/full doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2012.00217.x

- Højer, L., and M. A. Pedersen. 2018. Urban Hunters—Dealing and Dreaming in Times of Transition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Humphrey, C. 2017. “A New Look at Favours: The Case of Post-Socialist Higher Education.” In Economies of Favour After Socialism, edited by N. Makovicky and D. Henig, 50–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jensen, C. B. 2007. “Infrastructural Fractals: Revisiting the Micro—Macro Distinction in Social Theory.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25: 832–850. doi: 10.1068/d420t

- Laszczkowski, M., and M. Reeves. 2017. “Introduction – Affect and the Anthropology of the State.” In Affective States: Entanglements, Suspensions, Suspicions, 1–14. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

- Lister, R. 2004. Poverty. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Lkhagva, E. 2017. “Nuudel, Shiidel (Television discussion).” Mongol HD, Ulaanbaatar, Mongol HD TV studio.

- Makovicky, N., and D. Henig. 2017. “Introduction: Re-Imagining Economies (After Socialism).” In Economies of Favour After Socialism, edited by N. Makovicky and D. Henig, 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, R. 2017. “Settling Between Legitimacy and the Law: At the Edge of Ulaanbaatar’s Legal Landscape.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 24 (1): 7–20.

- Pedersen, M. A., and L. Højer. 2008. “Lost in Transition: Fuzzy Property and Leaky Selves in Ulaanbaatar.” Ethnos 73 (1): 73–96. doi: 10.1080/00141840801930891

- People’s Representative Hural. 2016. “Regulation for Selecting a Unit Leader in Chingeltei District Khoroos.” Administrative Office of the Chingeltei District Governor.

- Plueckhahn, R. 2017. “The Power of Faulty Paperwork Bureaucratic Negotiation, Land Access and Personal Innovation in Ulaanbaatar.” Inner Asia 19 (1): 91–109. doi: 10.1163/22105018-12340080

- Roy, A. 2005. “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 71 (2): 147–158. doi: 10.1080/01944360508976689

- Simone, A. M. 2015. “Relational Infrastructures in Postcolonial Urban Worlds.” In Infrastructural Lives, edited by S. Graham and C. McFarlane, 17–38. London, UK: Routledge.

- Sneath, D. 2001. “Notions of Rights Over Land and the History of Mongolian Pastoralism.” Inner Asia 3 (1): 41–58. doi: 10.1163/146481701793647750

- Sneath, D. 2006. “Transacting and Enacting: Corruption, Obligation and the Use of Monies in Mongolia.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 71 (1): 89–112. doi: 10.1080/00141840600603228

- Statistics Bureau of Chingeltei District Governor’s Office. 2015. Households and Population in Chingeltei district-2014. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.chingeltei.gov.mn/wp-content/uploads/%D0%A5%D2%AF%D0%BD-%D0%B0%D0%BC-2014.pdf.

- Terbish, B., and M. Rawsthorne. 2016. “Social Exclusion in Ulaanbaatar City Mongolia.” Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 26 (2–3): 88–101. doi: 10.1080/02185385.2016.1199324

- Tsing, A. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World – On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- UN-Habitat. 2010. Urban Poverty Profile: Snapshot of Urban Poverty in Ger Areas of Ulaanbaatar City. Ulaanbaatar: UN-Habitat Mongolia Office.

- Vanderberg, J. 2013. “Analysis Conducted on District Information: Identification of Service Inaccessibility Points in Ulaanbaatar Municipality.” Accessed from Ger Area Development Bureau information file in April 2016.

- Wagner, R. 1991. “The Fractal Person.” In Big Men and Great Men: Personifications of Power in Melanesia, edited by M. Godelier, and M. Strathern, 159–174. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Woliver, L. R. 1996. “Mobilizing and Sustaining Grassroots Dissent.” Journal of Social Issues 52 (1): 139–151.

- World Bank. 2015. Land Administration and Management in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Zelizer, V. A. 1989. “The Social Meaning of Money: ‘Special Monies’.” The American Journal of Sociology 95 (2): 342–377. doi: 10.1086/229272

- Zelizer, V. A. 2011. “Payments and Social Ties.” In Economic Lives, 136–149. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.