ABSTRACT

The European Union’s (EU) 2019 New Strategy for Central Asia and joint meetings with Central Asia’s five foreign ministers established standards and expectations for mutual relations. Throughout those initiatives and proclamations, the EU stresses its un-geopolitical essence and behaviour, including the statement that affords the article’s title. The article identifies five issue areas that demonstrate that, despite declarations otherwise, the EU reasons and acts geopolitically in this contested region: (1) the promotion of Central Asian regionalism; (2) the inclusion of Central Asia in formations beneficial to the EU; (3) selectively in economic and functionalist cooperation; (4) democracy, human rights and civil society promotion; and (5) international education cooperation. The EU identifies its comparative advantage through cost–benefit analyses and seeks to enhance its attractiveness by offering its allies to Central Asia, while excluding other, present actors. That the EU is often outmanoeuvred does not diminish this subtle yet discernible geopolitical conduct.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) frames itself as a ‘non-geopolitical’ actor in Central Asia. When the EU’s 2019 Strategy is compared with other EU statements and activities, however, its intentions and actions reveal strategies of competition, ones substantial and directed enough to constitute it a geopolitical actor. This article ascertains how, subtly but significantly, the EU recognizes and responds to competition from others, and seeks to maximize its comparative advantages against the regional ambitions of others. The article additionally identifies the EU’s unstated weaknesses, and how it limits them. These acts constitute cost–benefit analyses of how to deploy available resources, behaviour recognizable from traditional understandings of competitive international conduct. Furthermore, the EU seeks to boost its attractiveness in Central Asia through the mobilization of its wider international–organizational offerings, bringing allies to the region. In these regards, the Strategy behaves in line with the new European Commission of 2019 that, if hesitantly, nevertheless began to speak of geopolitics (for commentary, noting also that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen needed over an hour of her State of the Union address before mentioning ‘geopolitics’, see Brzozowski Citation2020).

The EU’s first Central Asia strategy, in 2007, identified the region’s changed strategic value after the 9/11 terror attacks and international intervention in neighbouring Afghanistan. The EU’s 2019 Strategy for Central Asia and related events and declarations, particularly pertaining to the Foreign Ministerial summit of 2019 and to the European Council Conclusions, illuminate Brussels’s approach to the region.Footnote1 The EU pronounced in 2019 that Central Asia ‘has always been a key region’ (European Commission Citation2019). These claims are made even as scholarship on the EU’s external relations gives scant attention to Central Asia (Fawn, Kluczewska, Korneev Citation2022).

The present aim is to place EU objectives from its key documents of 2019 for future Central Asian relations in wider context of other EU statements and actions, and of observers, to reveal the EU’s sense, stated and especially otherwise, of its abilities and interests in engaging with Central Asia, and how those compare against other actors. Despite what the EU asserts about being un-geopolitical, it both performs in a theatre where others act competitively and is responding accordingly.

Attention is given to the EU’s ability to reshape itself in a region which it states is increasingly important, and where challenges to its influence intensify. Central Asia is a region where contrarian examples of authoritarian politics are exerted, and by not one but two major authoritarian actors: Russia and China.Footnote2 The EU faces enormous challenges also from its geographical remoteness and the resource provisions offered by those two neighbouring states, while also advancing a normative agenda that confronts those extra-regional actors and the Central Asian states. Nor, potentially to the EU’s benefit, are outside powers able to realize their intentions (see Heathershaw, Owen and Cooley 2019, for contentions of how Chinese and Russian state interests are moderated in their execution in Central Asia by other, including societal, actors). Additionally, while non-Central Asian actors may not seek direct or even indirect physical control of territory, this region is a strong candidate to be an example where an evolution of spheres has occurred, creating a contestation over its forms and content (an interesting argument is advanced by Costa Buranelli Citation2018). Competition for influence in Central Asia certainly exists, even if the EU seeks to present its engagement as non-competitive and non-exclusionary, and ideational in content, with values that it expounds to be good and applicable universally.

When the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini launched the 2019 Strategy, she pronounced the words providing this contribution’s title: in Central Asia, the EU is ‘not here for geopolitical interests or games’ (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Citation2019b). The EU seeks not competition and to be received as un-geopolitical. In its principal sectors of engagement, the EU identifies its own allies and ignores some already present. It also faces challenges to its offerings to Central Asia; these are absent from the Strategy, but evidenced in other EU declarations and publications. This unstated but present competition is identified across five areas of engagement in which the EU believes it exerts comparative advantage over competitors: the promotion of regionalism, which itself takes two forms: the EU’s promotion of Central Asian regionalism, and then Central Asia’s placement in other formations – economic and functional initiatives; democracy, human rights and independent civil society promotion; and higher education.

The Strategy is structured according to three ‘interconnected and mutually reinforcing priorities’: ‘partnering for resilience’, ‘partnering for prosperity’ and ‘working better together’ (High Representative Citation2019a). Some themes, such as democratization, are located within one of these priorities, but all are wide-ranging and fulfil the declaratory mutual interlinkages of issues that could be identified for analysis. The aspiration is not to retell the Strategy’s contents, but to detect how, strategically, the Strategy includes and excludes actors and issues. We turn first briefly to what could constitute ‘geopolitical’ EU behaviour, and the characteristics of competition in the Central Asian region where the EU seeks influence.

The EU as a geopolitical actor in Central Asia and regional dynamics

A sui generis international actor, neither an international organization nor a state, the EU advances its values and incentivizes engagement by offering access to the world’s deepest integrated supra-national market (see Dzhuraev Citation2022 for EU behaviour regarding Central Asia). Values promotion and the pursuit of interests need not be mutually exclusive, and in that regard the EU engages in realist behaviour by overtly working with and mobilizing certain allies to heighten the EU’s attractiveness. These allies include other like-minded international organizations and selected international financial institutions. The EU simultaneously seeks to minimize the influence of competitor international actors in Central Asia. That, as this article identifies, the EU is outdone in its areas of comparative advantage does not diminish the intentions of competitive engagement. It undertakes appraisals of tools available, in relative and relational terms – in comparison with those of others, and their suitability to achieve EU aims.

Despite frequent contemporary invocations of the 19th-century imperial epithet of ‘Great Game’ to explain competition in and around Central Asia, none of the extra-regional actors work correspondingly, and Central Asian states also have agency (an essential dynamic not focused here, but see Cooley Citation2012). China’s influence comes heavily from trade, aid and especially infrastructural development. Russia emulates more familiar geostrategic behaviour, through military-alliance formation and the continued and sometimes expanded security presence, including the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Its Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) also provides economic-trade influence and Russia perhaps is most influential as a site of labour for some Central Asian populations, and the remittances generated. Even in these domains, however, Russian influence is limited and inconsistent across the region. And Russia opens itself to competition to the EU in soft power: culturally and educationally. Influence of the United States might be framed predominantly as military influence, and its own Strategy includes such along with soft power, yet its armed presence has diminished after base closures in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Primary and self-defined influence remains soft power, and with similarities to some of Russia’s: culture and education (elaborated comparatively, below).

Even if the EU is the least-applicable actor for the ill-fitting motif of the Great Game, it nevertheless identifies areas of competition to exert its comparative advantage. The EU seeks to define and place Central Asia in regional state formations of its making, and ones that serve EU interests. The EU seeks thereby to create strategic benefits and achieve strategic goals. It is to those practices of self-interested region formation to which we turn first.

The EU’s promotion of Central Asian regionalism

Internal challenges notwithstanding, the EU remains the world exemplar of region-making. The EU likes dealing with, even making, regions elsewhere. The EU created a ‘Western Balkans’ where no such term existed (nor with a tallying ‘Eastern Balkans’). The EU Eastern Partnership (EaP) grouped six unlikely countries,Footnote3 a process that is argued presently to have an unstated bearing on the EU’s approach to region-making in Central Asia. In the early post-Communist period the EU was influential enough that some saw it as obligating Central European states to form regional cooperation formats, even if Brussels later judged countries individually for accession. The EU likely also approaches the Central Asian region, in managerial terms, possessing a global vision for itself that requires attempting to organize the world into workable units that recognize regional dynamics and serve EU interests.

The 2019 EU declarations are equivocal about the degree of, even the appetite for, Central Asian-initiated regionalism. So too are they regarding EU ambitions to promote regionalism in Central Asia, and between the region and itself. This ambiguity may be strategic: rather than limiting its options through declarations, the EU maximizes opportunities as regional circumstances evolve. The EU simultaneously identifies and promotes common regional initiatives among the five Central Asian states, while recognizing and facilitating bilateral arrangements. That is necessary because of the dissimilar views on Central Asia regionalism and on engagement with the EU that the five states have held (among previous works are Hoffmann Citation2010; Matveeva Citation2006; and Warkotsch Citation2011; specific sources are given below). The EU is also indeterminate, arguably strategically, on where and how Central Asia fits into wider regional formations and policies. These issues are assessed in turn.

Challenges aside, the EU promotes Central Asian regionalism. The EU’s Special Representative for Central Asia Peter Burian identified the EU’s intrinsic approach towards making and working with regions: ‘Regional cooperation as a factor of stability and sustainable development is deeply rooted in EU’s DNA’ (Burian Citation2019). The EU’s genetic disposition still needs to engage; its success in finding and working with regions still depends on local conditions and the mutual compatibility of states. Long-recognized are difficulties of achieving anything approaching regionness in Central Asia. Overlapping forms of cooperation, including those instigated by and including outside actors, have generated the epithet of ‘virtual regionalism’ (see especially Allison Citation2008; for earlier limitations on regionalism, see, for example, Kubicek Citation1997; Russo Citation2018; and Hanova Citation2022). Central Asia’s lack of regionalism is largely absent from the Strategy, which seeks and needs optimism, but awareness materializes in parallel EU documents. EU institutions assert divergent approaches to policies, as will be discerned below. A European Parliament research report offers greater accuracy than the Strategy, indicating what is familiar to regional analysts but absent from Commission statements: Central Asia not only faces geographical handicaps to cooperation but also has suffered outright ‘mutual hostility’ between states (Russell Citation2019, 8).

The EU nevertheless presents itself as a model for regionalism and supports seemingly region-indigenous cooperation efforts. To the EU’s credit, post-Soviet formations involving some of the Central Asia states are ‘loosely modelled’ on or even ‘mimicking aspects’ of the European Commission (Cooley Citation2012, 60). But the EU’s aspiration of region-building in Central Asia, let alone providing its model, is constrained. The Strategy implies that the EU possesses resources to endow Central Asia with more regionness through its lobbying capacities, offering access to its international formats to Central Asian states.

Assessing EU expectation of and commitment to regionalism in Central Asia benefits from three considerations: how new and meaningful is Central Asia’s own commitment to regionalism; how much the EU promotes regionalism; and the extent to which the EU continues to pursue bilateralism instead of region-wide engagement. By analysing the totality of EU statements, ambiguities in EU approaches on the latter two points are discernible.

Optimistically, Burian acknowledged a ‘new spirit of regional cooperation’ from a 2017 conference on regional development and security convened in Samarkand, in an Uzbekistan that was opening to the world after the death of decades-long ruler Islam Karimov (Burian Citation2019; for resulting contemporary impetuses for regional cooperation, see, for example, Faizullaev Citation2017, esp. 174–175).

EU support for Central Asian regional cooperation may be commendable, but rests on limited substance. Apart from association with post-Karimov changes in Uzbekistan, ‘the new momentum in regional cooperation’ is thin, and certainly not region wide. Even that seems based on the first informal Summit of Central Asian leaders hosted by Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbaev in Astana in the March of the year preceding the 2019 Strategy. Although that meeting was noted as ‘a sign of improving ties’ in the region, Turkmenistan’s representation was a parliamentary official rather than a high minister, let alone President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov (RFE/RF Citation2018). Nevertheless, this development has ‘enhanced the relevance of the EU’s experience in crafting cooperative solutions to common challenges’ (High Representative Citation2019a, 1). To be sure, the 2018 meeting was a watershed, ‘absolutely unthinkable’ two years prior (Gotev Citation2018), an observation as true as it is also indicative of the paucity of previous cooperation. While the EU’s reinvigoration of regionalism was ‘Built on Uzbekistan-inspired optimism’, the 2019 Strategy was already described in that year of its launch as ‘undercut by Kazakhstan-inspired pessimism’. The latter included domestic repression, seen as managing the domestic political transition following Nazarbayev’s resignation from his 30-year leadership (Putz Citation2019).

Outside of the 2019 Strategy document, but concurrently with its release, the High Representative advanced EU ambitions for region-making:

The EU has a strong interest in seeing Central Asia develop as a region of rules-based cooperation and connectivity rather than of competition and rivalry. The EU is determined to invest in the new opportunities and growing potential for cooperation within and with the region as a whole. (High Representative Citation2019a, 2, emphasis added)

The EU also disseminates its message of region-making in Central Asia through supportive international organizations (IOs). The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), of which all EU members are participating states, summarized in a press release the EU’s approach to fostering Central Asian regionalism, with ambitions that ‘the region develops as a sustainable, more resilient, secure, prosperous, and closely interconnected political and economic space’ (OSCE Citation2007). For some purposes, the EU wants Central Asia and IOs to regard the region as a coherent unit (see also Korneev Citation2017). Doubtless a foundation for this stems from common legacies of Soviet rule, and shared functional and security issues, such as water, drug trafficking and instability from Afghanistan.

For all efforts at region-making, the Strategy itself is restrained. It writes that:

while respecting the aspirations and interests of each of its Central Asian partners, and maintaining the need to differentiate between specific country situations, the EU will seek to deepen its engagement with those Central Asian countries willing and able to intensify relations. (High Representative Citation2019a, 1)

The Council Conclusions state better than the Strategy the EU’s expectations for relations with Central Asian states. These welcome ‘regional cooperation in Central Asia’, but recognize the EPCAs ‘remain a cornerstone’ of EU interactions (High Representative Citation2019a, paras 4–5). Other EU documents amplify that EU relations will foremost be country to country. The General Secretariat of the Council wrote that the ‘scope of the EU’s relations is linked to the readiness of individual Central Asian countries to undertake reforms and strengthen democracy, human rights, the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary … ’ (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2019). Bilateral relations between the EU and individual Central Asian states is an approach supported by many, even to the point of critique, that the EU overemphasizes any regional approach (e.g., Kluczewska and Dzhuraev Citation2020, 226). Even before the EU’s 2007 Strategy, the EU was implored to avoid a regional approach. The International Crisis Group (Citation2006, i) urged that, ‘Europe must move away from largely unsuccessful policies, particularly the promotion of region-wide projects, and take on a more focused and active role geared to the distinct characteristics of each of the region’s five states.’

Once released, any document leaves its authors’ hands to become interpretable. The Strategy seeks to make regionalism in Central Asia. In cases where the Strategy is otherwise deemed to be lacking ‘concrete’ initiatives, it is still seen positively as working region-wide, with the Strategy quoted for its intentions ‘to address structural constraints on intraregional trade and investment’ (RFE/RL Citation2019). The EU purposes towards regionalism are even inferred as extending beyond mutual security interests or environmental concerns, so much that the EU is ‘investing in regional cooperation in order to move towards common rules and a more integrated regional market’ (Amalriks Citation2019). These are both symbols of and underpinnings for regionalism. If that was insufficiently aspirational, the EU also fashions Central Asia into wider regional formations that aid its broader interests.

The Central Asian region within other EU-supported regions

On the essentialist issues of regional-building and inter-regionalism, the totality of the EU’s approach shows either inconsistencies or, possibly, strategic opportunism, allowing it to be a ‘flexible document’ and adaptable to local circumstances (Boonstra Citation2019). An additional dimension is further EU flexibility on where Central Asia as a region fits with other EU-designated state formations.

The EU’s External Action Service clusters Central Asia with the EaP countries and Russia. Central Asia was also included in the concept of Wider Europe, launched by the EU in 2003, anticipating the impact of the EU’s largest expansion occurring the next year, and one propelling it more south and eastwards (Commission of the European Communities Citation2003). ‘Wider Europe’, however, generally lost salience, and was superseded six years later by the EU’s European Neighbourhood Partnership (ENP). The EU incorporated Central Asia in this geographically broad initiative that encompassed Mediterranean and post-Soviet countries. The EU’s 2007 Central Asia Strategy enunciated Central Asia’s inter-relationship with EU policies; the EU stated that its commitment to ENP would ‘bring Europe and Central Asia closer to each other’ (Council of the European Union Citation2007, 2). The Strategy, however, raised wider regional cooperation on a limited basis: ‘Whenever useful for the EU and Central Asia, and depending on issues, dialogue and cooperation programmes with Central Asian states could extend to neighbouring states, such as countries of the Eastern Partnership [EaP], Afghanistan and others’ (High Representative 2019, 3) (some of the political–geographical interrelationships are discussed by Fawn Citation2020). EU documents on transportation infrastructure for Central Asia (discussed separately, below) intimate connections between other regions, and support efforts to link Central Asian and EaP countries and Afghanistan (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2018, 4; Citation2019, 5).

The 2019 Strategy left unstated any impact of the EU’s EaP. Dating from 2009, the EaP sought, rather unsuccessfully, to define yet another region that conformed to EU conceptions of its neighbourhood: that of six countries with divergent polities, economies and especially orientations towards the West or to Moscow, sharing only the commonality of being post-Soviet, not Central Asian, and flanking the Russian Federation. The EaP made the EU more geopolitical, even if it sought otherwise, and missed or ignored that others saw it accordingly (among emerging literature, see Nitiou and Sus Citation2019; and below). An historical lesson of the EaP for EU engagement with Central Asia was that Moscow (and possibly other non-participating post-Soviet governments) felt excluded from even basic information exchange on this leading EU foreign relations initiative, one intended to transform how Russia’s neighbouring states engaged with it and the EU (see, for example, Wilson on the EU’s rebuff of Russian Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov and the Russian right to know of EaP developments; Wilson Citation2014, 17; see Sakwa Citation2015 for criticism of EU mistreatment of Russian interests). Russian hostility at least was recognized by European Parliamentarians who in 2014 regretted ‘that the Russian leadership regards the EU’s Eastern Partnership as a threat to its own political and economic interests’ (European Parliament Citation2014).

The mass protests that became Ukraine’s Maidan/Revolution of Dignity in 2013–14 constituted unprecedented popular support for the EU, following the Yanukovych government’s abrupt refusal to conclude its EU Association Agreement. Those developments alarmed Russia and ultimately plunged EU/Western–Russian relations into calamity. Unstated, but consequential, is how the EU’s EaP experience may have shaped its engagement with Central Asia. Some of Central Asia’s importance grows from being the ‘neighbour of the neighbour’, an (unofficial) expression that is not applied to the EU’s several other neighbourhoods, such as the Middle East and the Mediterranean (Spaiser Citation2018, 60). Earlier, Central Asia was described a ‘ghost vacuum’ between the EU’s other regional projects (Kavalski Citation2012, 85), and the EU’s multiple regional packagings of Central Asia may create (unhaunted) larger placements for this region. As discussed below, EU attempts at influencing transportation infrastructure extend far beyond post-Soviet Central Asia’s physical confines.

Central Asia further tallies in the EU’s spatial outlook, and constituting primary impetus behind its intensified cooperation with Central Asia, has been the post-9/11 intervention in Afghanistan. Two of the EU’s principal pan-regional initiatives that involve Central Asia governments address security threats from Afghanistan: the Central Asia Drug Action Programme, and Border Management in Central Asia (Korneev Citation2013, esp. 312–315). Trade and transportation connect Central Asia and Afghanistan, as recognized in EU-related syntheses, although not in the Strategy (Russell 2017, 12). Rather, other than extending regional cooperation on border management to Afghanistan, the Strategy writes only of ‘Integrating Afghanistan as appropriate in relevant EU–Central Asia dialogue meetings and regional programmes’ (High Representative Citation2019a, 3). Convening meetings are conceivable in an EU-supported but pan-regional format; actionable programmes less so.

The EU assigns three forms of regional identity to Central Asia: first, as a series of bilateral relations, with enormously varying intensities; second, of the five states and concomitant with largely declaratory region-wide initiatives, which receive more funding than any single Central Asian state, and occasionally to the point that Central Asia seems an identifiable, even well-functioning regional unit; and third, a region within still two others: the EU’s wider neighbourhood, and then one including Afghanistan.

Apart from seeking to make Central Asia into a region, the EU also seeks to engage with it on an inter-regional basis. The EU thereby offers to assist Central Asia with access to other regional and international organizations. The EU reveals itself to be selective as to which issue areas and partners it permits. The next section identifies stated and unstated access to, and of denial of, the region of Central Asia to other interstate formations for which the EU is the regional gatekeeper.

The selective incentivization of inter-regionalism: who is recognized – and who is not?

In addition to region-building, the EU pursues inter-regionalism: regions engaging with each other. As established, the EU encourages regionalism in Central Asia, but cooperation among the five post-Soviet states remains, if not stillborn, then stunted. Inter-regionalism – that is, between the EU and a coherent group of the five Central Asian states – is even more remote. Inter-regionalism is often, and simply, defined as ‘institutionalized closer relations between two regional blocs’ (Doctor Citation2007, 281). The depth and quality of the institutionalization, naturally, needs definition. EU–Central Asian inter-regionalism is very limited; the convening of meetings is deemed ground-breaking. We look first at whom the EU identifies for inter-regionalism, and then those it skips, and why and what omissions reveals of the quality and capacity of EU–Central Asian relations.

The EU’s emphasis is on the United Nations (UN), the OSCE, the Council of Europe, albeit the latter lacking Central Asian membership, and on international financial institutions. These are ones to which the EU or EU member states are party. The EU also avoided mention of the United States, even though the 2019 American Strategy uses the same language as the EU, that of consulting with and coordinating towards Central Asia ‘with like-minded partners’. The US Strategy names the EU as such a partner, even though the EU does not reciprocate (Bureau Citation2020, 5). By contrast, the EU’s Burian asserts that the US has adopted the EU’s 5+1 model of engagement (Heinecke Citation2019, 7). The EU seems not, however, to mention that supposed US geopolitical imitation aside, it alone provides formats in which all five Central Asian states meet with each other: China and Russia support regional formats both less inclusive and larger. The post-Soviet space has regional institutions important to its member states which include four Central Asian states, non-aligned Turkmenistan remaining outside. The CSTO lacks EU attention because the former is a military formation while the latter is not. Others include the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the EAEU (among the literature, see Dadabaev Citation2014 for the SCO’s limitations; Russo Citation2018; Vinokurov Citation2018; for a critique of analytical approaches to Central Asia regionalism as focused on talk rather than action, see Azizov Citation2017).

Even if the CSTO’s military character makes a non-corresponding body for the EU, its approach to seeking recognition by Western institutions illustrates the tendency among Eurasian state formation to covet recognition from Euro-Atlantic institutions. Such intentions come also from a non-Central Asian post-Soviet leader. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko explained:

All of us [presumably meaning CSTO heads-of-state] have stated that nobody wants to recognize the CSTO, particularly NATO. It seems we are not the right sort. I was listening to this talk, thinking that they will never recognize us if we beg for their recognition. We have to force them to recognize our organization. (Belarus.by Citation2016)Footnote5

Central Asian officials speak, if atypically, to possible EAEU–EU synergies. Questioned on the relationship, Kazakhstan’s deputy foreign minister, a country that signed an EPCA, insisted ‘absolutely no friction’ existed between two formations. Instead, he asserted that ‘even greater opportunities’ were possible for both Kazakhstan and other EAEU members with the EU, and also for it (cited in Gotev Citation2019a). The EU’s thinking on the EAEU is telling in its absence. The Strategy mentions the EAEU strictly in a footnote, and only to reference that Kazakhstan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s trade relations with the EU through ECPAs are unaffected by their membership of the Eurasian formation.

In short, the EU’s unstated positions in its key documents on inter-regionalism with purely Eurasian members speak loudly: to keep them at bay. Of the other two major Eurasian state formations, the SCO and the CSTO, their only mention in the Strategy is of ‘the interest of the EU to continue monitoring developments’ pertaining to them (Section, 1.2, 6; emphasis added). Such terminology is unsuggestive of engagement, even if, on ground, its representation speaks of engagement with everyone and of avoiding binary choice (Heinecke Citation2019, 7).

The EU’s selective engagement with regional and international organizations is reiterated in the Council Conclusions. Those specify that the EU remains working with the UN, the OSCE and the Council of Europe (CoE) in multilateral engagement with Central Asia (3, para. 8). Some of these IO partnership risks are being construed as ideological alliance-making. The OSCE, however, has not been judged neutral by many of its post-Soviet participating States (for post-Soviet/Western competitions in and over the OSCE, see Fawn Citation2013). Instead, the OSCE is seen as ‘longstanding and close cooperation with the EU’ and the EU, unlike post-Soviet interstate formations, is ‘represented in all OSCE decision-making bodies’ (Herman and Wouters Citation2019, 259). Central Asian states participate in the OSCE (but not the CoE), and conspiracies must not be inferred. Other state formations of which Central Asia state are members are absent from the Strategy. This unexpressed selection and exclusion of regional and international organizations becomes more apparent from determining how the EU pursues economic and functional cooperation with Central Asia.

The EU’s unstated selectivity of actors for economic and functionalist cooperation

In matters economic the EU offers to Central Asia both its own experience and the benefits of its membership of other regional and international organizations. Unstated but implied is that these are select, and covetable actors. The EU’s chief encouragement of relations remains that it is ‘a leading supporter’ of the integration of Central Asian states into the WTO (High Representative Citation2019a, 1). The Strategy also offers that the EU will reinforce cooperation with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and with the International Labour Organization (ILO) to enhance business and working conditions. The Strategy additionally pledges EU ‘help to consolidate the progress made’ with compliance with ILO conventions (High Representative Citation2019a, 1.1, 4), language implying that too little has been done and obligations remain unfulfilled.

The Strategy addresses issue areas that are functionalist – win–win cooperation that need not be politicized. Indeed, the EU’s approach to regional cooperation in Central Asia has heavily rested on functionalism, to the exclusion of security provisions, precisely the cooperation that Central Asia seeks, and which other partners extend, including the USA (e.g., Starr and Cornell Citation2018, 61–62). The US Strategy includes the security cooperation motto ‘Train together, fight together’, and multilateral initiatives that ‘strengthen regional security across Central Asia’ (Bureau 2019, 3).

The EU continues to rest on functionalist cooperation, and this is potentially an area of distinctive contribution. The EU’s first Special Representative for Central Asia, Pierre Morel, provided after the 2007 Central Asia Strategy a representative approach of identifying and building functional gains: ‘With the region connected through cross-boundary rivers, lakes and seas, a regional approach to protecting these resources is essential’ (Morel Citation2008). Of course, especially water provokes fundamental regional division, and even basic legal agreements are lacking (e.g., Boklan and Janusz-Pawletta Citation2017), even if on paper cooperation would seem beneficial.

The Strategy and related documents stress EU cooperation with Central Asia in functionalist organizations, particularly the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea and the United Nations Regional Centre for Preventive Diplomacy for Central Asia (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2019, 3, 8). The EU offers environmental protection assistance to Central Asia from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Such declaratory aims are laudable and muster the EU’s comparative advantage. The EU offers a form of alliance-building by allowing Central Asian states to access Western and global financial institutions where EU member states enjoying influential membership. Again for the EU, WTO accession is paramount: Burian reiterated that the ‘EU remains a leading supporter’ of Central Asian accession (Burian Citation2019).

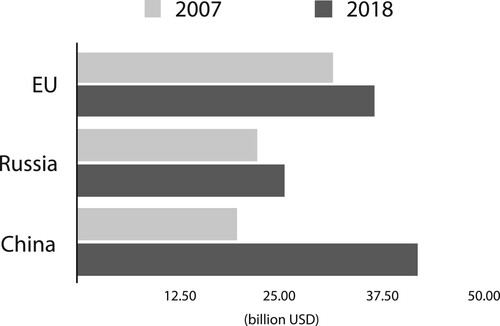

The EU not only overtly ignores competition, but related documents disregard the supersession of EU influence. The 2019 US Strategy for Central Asia pronounces that the United States ‘led’ the World Bank, IMF, World Bank and even the Asian Development Bank in extending their aid of US$50 billion to Central Asia (Bureau Citation2020, 2). While actors might compete for the disputable title of lead influencer of wider financial assistance to the region, trade statistics should be more straightforward. One reads that ‘European trade and investment … have made the EU the main economic player in Central Asia, ahead of Russia and China’ (Russell Citation2019, 1). The same report omits changed comparative trade turnover. Non-EU sources demonstrate how, even in its best attribute, the EU faces growing trade competition by Russia in Central Asia, and China surpasses the EU’s total volume of regional trade (). This situation is acknowledged in jest, such as Burian’s reported joke that to Central Asia, ‘China is coming with an offer nobody can refuse, while the EU is coming with an offer nobody can understand’ (cited in Gotev Citation2019b).

Figure 1. Total European Union (EU), Russian and Chinese trade turnover compared, 2007 and 2018. Source: Adapted from Bhutia (Citation2019a), using International Monetary Fund (IMF) data.

The unstated disparities of influence become even starker regarding the development of regional and trans-regional transportation infrastructure. The 2019 Strategy speaks of developing transport links, and seeks to engage Central Asia in its own transportation network (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2018). The 2019 Strategy promotes ‘work towards connecting the [EU’s] extended Trans-European Network for Transport with networks in Central Asia and advancing mutual interest in the implementation of joint energy and transport connectivity projects’ (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2019, 5, para. 13; High Representative 2019, 11, 2.3). That ambition extends to connecting the Black and Caspian seas, sources of significant hydrocarbons for Europe.

The EU has not openly recognized that Chinese initiatives in Central Asia have eclipsed theirs. The 2007 EU Strategy intended an EU–Central Asian transport corridor; nothing has materialized. Such thinking included a pipeline to carry Turkmen gas to Europe. That aspirational project’s fate indicates Chinese usurpation of the EU’s aspirations for furnishing infrastructure: in the same year that the EU launched its first Central Asia strategy, a pipeline from Turkmenistan to China was begun. Completed in two years, bearing the region-evoking name of the Central Asia–China pipeline, the pipeline became the single largest conduit of natural gas to China, in Beijing’s global effort to secure resources (e.g., Bhutia Citation2019b).

Rather than the EU, the United States claims to facilitate Afghan goods reaching European markets through Central Asia (see US State Citation2019, for comments of Ambassador Alice G. Wells, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs). The United States co-finances, without EU participation, the Central Asia–South Asia power project, more familiarly known by its alphanumerical acronym CASA-1000. This ambitiously connects Central Asia southward, to Afghanistan and Pakistan, through the transmission of electricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. CASA-1000 lacks reference in the EU Strategy or the Council Conclusions, although mention is made that, ‘The EU will help to modernise electricity distribution and develop interconnections between countries, to spur regional and inter-regional electricity trade’ (High Representative Citation2019a, 2.3, 12). The European Parliamentary research report acknowledges that the EIB and EBRD are funding CASA-1000 (Russell Citation2019, 8). The EU operates at an aspirant and declaratory level; others have implemented.

Rather than being a provider of infrastructure across Central Asia, the EU is a consumer. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), though nearly global in reach, was symbolically launched by China in Kazakhstan (and Indonesia). Even the concept of transport ‘connectivity’ in and for Central Asia was introduced not by the EU but in China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, the BRI’s precursor. To be sure, the European Commission ‘proposes the building blocks towards an EU Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia with concrete policy proposals and initiatives to improve connections between Europe and Asia’, an initiative launched at the Asia–Europe Meeting in 2018 (High Representative Citation2018). While the European Parliamentary 2020 report on EU–Asian connectivity welcomed cooperation on the Transport Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia, it noted the EU’s ‘systemic rivalry with China’, urged the EU to ‘play a much bigger role’, and lamented that Chinese regional infrastructural developments lacked transparency (European Parliament Citation2020, paras 27, 46, 56).

The BRI ensures that EU infrastructural aspirations cannot be achieved, even if the EU upholds Central Asia’s historical importance as a connecting highway between Europe and Asia. The EU also stresses, in keeping with its own values, that its conception of connectivity is ‘rules based’, ensuring respect for individual rights and meeting ‘high standards of social and environmental protection’, indeed ones expressly ‘inspired’ by the EU’s own experience (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2018, 2). Analyses suggesting EU–Chinese synergies still urge the former to stand for its rights and interests (Cornell and Swanström Citation2020).

Far from increasing Central Asian interest in infrastructural development, the EU brings conditions of environmental sustainability; its conception of connectivity is even qualified that way. By contrast, Chinese investment comes without conditions, and is believed to be primarily based on fossil fuels, the use of which could undermine the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, designed to reduce greenhouse emissions (e.g., Gallagher Citation2018). The Strategy speaks directly to working with the Central Asian governments to implement the Agreement (High Representative Citation2019a, 6, 1.6). The EU’s promotion of a green BRI may still be undercut by China, reportedly adapting to renewables so that in 2020 their use exceeded fossil fuels (e.g., Foley Citation2021). Irrespective, China’s financial assistance to Central Asian governments, provided without the political conditionality of US or EU assistance, results in Central Asian perceptions of the latter as ungenerous and restricting their state sovereignty (Sharshenova and Crawford Citation2017).

The EU seeks not only a values-based approach specific to transportation and environmental cooperation, but also applies wider normative aspirations: ‘The Council emphasises the importance for the EU to promote an approach which is sustainable, comprehensive, and rules-based, in line with EU’s values and interests.’ The Council elaborates that any ‘approach needs to be economically, fiscally, environmentally and socially sustainable, open and inclusive, with high standards of transparency and good governance’ (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2018, 3). EU recognition of Chinese dominance in economic and infrastructural initiatives in Central Asia seems limited to those of a non-policy publication affiliated to EU institutions that writes understatedly: ‘Chinese investments are upgrading Central Asian transport infrastructure’ (Russell Citation2019, 8).

By contrast, Fabienne Bossuyt points not only to declarative efforts but also concrete measures in Sino-EU cooperation, including a ‘long list of pilot projects’ and the creation of a multilateral investment format (Bossuyt Citation2019). EU-related documents suggest complementarity in EU and Chinese approaches to connectivity, even if the same recognize that the EU lacks comparable financial resources (Russell Citation2019, 11). Chinese–EU coordination, let alone tangible cooperation, remains only aspirational. Far more indicative of the threat to the EU from the BRI, and in contradistinction to the Strategy, was the damning report of EU national ambassadors to Beijing which denounced China’s self-serving interests (Heide Citation2018). The EU also engages in the contentious area of democracy, human rights and civil society promotion, seeking to inject other competitors into Central Asia.

Democracy, human rights and civil society

The EU continues from its 2007 Central Asia Strategy and its 2016 Global Strategy to promote democracy and human rights. The 2019 Strategy states early that Central Asian region-building should include common rules. While universalist EU values exist in the 2019 Central Asia Strategy, they are muted and placed alongside other, often value-neutral functionalist objectives such as economic development and environmental protectionism. Nevertheless, EU statements issued in parallel or sequential to the 2019 Strategy emphasis the EU’s aims of democracy and human rights promotion in Central Asia. That the EU faces ‘extremely unfavourable domestic and external conditions’ for democracy promotion in this region is well-established (Axyonova Citation2014, esp. 2), and some document the EU’s commitment previously nevertheless to promoting them (Sharshenova Citation2018). The EU’s Burian challenged critiques of ‘the EU’s inability to promote, and the Central Asian countries incapability to embrace, common values and international commitments, in particular in the area of basic freedoms and human rights’. He added, ‘I am pleased to note that there is a growing understanding in the region that promoting rule of law, good governance, human rights and a strong role of civil society is not a “Western agenda”. These principles are universally recognised’ (Burian Citation2019).

Such optimism belies selective policy reticence. Occasionally the EU seeks not to push hard, nor reveal perhaps its unpersuasiveness. The EU offers in muted tones help to Central Asian states to accede to the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court, created to try individual leaders accused of the gravest crimes. While the EU’s Strategy does not mention the United States as a partner, let alone a like-minded one, as the American Strategy does of the EU, it may also be that EU support contrasts itself against the United States, which is not a State party to the Statute establishing the Court. The EU offers Central Asian governments the legal experience of its member states’ accession to the Rome Statute (High Representative Citation2019a, 4, 1.4).

The Strategy intends that independent, societal actors (as limited as these may be) are included, even embedded, in the official structures of engagement. To that end, the subsection on EU–Central Asian cooperation formats is entitled ‘Strengthening the Architecture of the Partnership and Engaging Civil Societies and Parliaments’. Highlighting the involvement of civil society itself does not address the pressures placed on autonomous groups in these countries, or how post-Soviet states have undercut, or instead mimicked civil society actors and reappropriated the concept of civil society by creating their own loyal equivalents of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). To be sure, debates continue on the origins and capacity of civil society in Central Asia, and even how to assess that (among these are Pétric Citation2005; Roy Citation2005; and Buxton Citation2011). Nevertheless, the EU seeks to support and elevate into its relations with Central Asia some form of civil society.

Others are not only sceptical of EU efforts but even see them as ineffective against the persecution regional activists face. Asked one commentator: ‘What good will training Kazakhstan’s civil society activists do if they are denied permits to demonstrate by the state and then jailed for going ahead with their protests? European leaders were silent in the face of the recent arrests’ (Putz 2019).

In wider IO engagements, government-organized non-governmental organizations (GONGOs) have replaced non-affiliated civil society (e.g., Synovitz Citation2019). That tactic has become especially evident in the OSCE’s annual, two-week Human Dimension Implementation Meetings (HDIM). The US Mission to the OSCE deemed GONGOs to have ‘polluted’ discussions (Citation2016). The following Ukrainian statement is politically charged because of conflicts over Crimea and eastern Ukraine, but it remains indicative of the perceived influence of the international use of GONGOs: ‘We regret that a genuine and open dialogue during HDIM was seriously undermined by Russian delegation’s determination to challenge the OSCE principles and commitments and to construct a parallel reality, employing GoNGOs from many participating States’ (Permanent Mission of Ukraine Citation2018). Tackling this issue of false, government-prompted civil society directly the 2019 Strategy specifies measures: ‘The EU will promote an enabling legal and political environment for civil society that allows human rights defenders, journalists and independent trade unionists and employers’ organisations to operate freely and safely.’ The EU promises to ‘encourage dialogue and cooperation between civil society and administrations at all levels’ (High Representative 2019, 4).The 2019 Strategy also includes practical proposals for increasing civil society activism, including that regional civil society representatives could convene informally but with EU and regional officials, alongside EU–Central Asian ministerial meetings.

The EU further contends that such initiatives would permit Central Asian civil society to ‘contribute to the development of the EU–Central Asia partnership and increase its visibility’ (High Representative Citation2019a, 3.1, 15). The EU thereby advocates for inclusion of non-governmental representatives in diplomatic forums and even for them to shape content. For these measures, the Strategy received positive recognition from Western human rights advocates. Wrote Human Rights Watch (HRW):

The new strategy offers a clear insight into the EU’s aspirations for a more democratic future for Central Asia’s 105 million citizens. It sets itself apart from the 2007 strategy, which largely focused on energy security, and lacked strong ambition for improving human rights in the region. (Dam Citation2019)

International education cooperation

While democracy and human rights promotion will surely remain contested between the EU and Central Asian governments, education is an area of relative agreement – and with prospects for augmented EU influence. Higher education forms part (with youth, innovation and culture) of a full section of the Strategy. In education the EU interlinkage of regional IO support becomes relevant again – this is the use of external allies to promote EU objectives. Already the 2007 Strategy was seen as creating some inter-regionalism for higher education (Jones Citation2010). The 2019 Strategy pledges that ‘The EU will support inter and intra-regional cooperation’ to improve education generally and to ‘promote synergies between education systems and the labour market’ (High Representative 2019; emphasis removed) The Strategy speaks to exchanges, notably encouraging ‘cooperation between EU and Central Asian higher education institutions as well as exchanges of students, academics and researchers’ (High Representative, 6, para. 14). The Strategy also encourages use of the Erasmus+ programme, worth €14.7 billion and engaging 4 million students (European Commission Citationn.d., EHEA Citationn.d.), to converge Central Asian practices in the Bologna process and the Torino principles on vocational education and training.

Converging higher education standards, however, has not been conducted on a regional basis. As with most EU activities in Central Asia, this occurs primarily bilaterally. The EU draws attention to individual country achieves such as that of Kyrgyzstan, which although not a member of the Bologna process, was making reforms to meet those of Russia and Kazakhstan, and the wider European higher education space: that is, the very formal, structured European Higher Education Areas (EHEA) (European Commission Citation2017, Section 8.3.1, 61). The EU nevertheless also proposes pan-regional educational reforms, seeking to ‘explore the possibility to help Central Asia to develop a regional higher education area’, again using the EHEA as the example (High Representative Citation2019a, 13, 2.4; emphasis added).

The Strategy does not recognize that even in this sector of EU prowess, regional competition throbs. All external actors recognize higher education as a means of attracting the good will of young and talented Central Asian students both now and especially in future decades, when they might ascend to positions of national influence. Separate EU documents acknowledge, at least informationally, the existence of regional competitors in higher education. For example, the 2017 report on higher education in Central Asia recognized the SCO’s initiatives for a network of universities. An EU report wrote that this network was ‘similar’ to the single EHEA (European Commission Citation2017). Seeing that the EHEA is the world leader in creating common supra-national education standards, and one to which several post-Soviet states including Russia have acceded, this is a remarkable complement and concession to the SCO.

Despite being overtaken by China for trade and investment importance to Central Asia, the EU retains potency in knowledge transfer and education. The EEAS’s 2019 factsheet accompanying the Strategy runs a section headline: ‘Supporting Education in Particular’ (EEAS Citation2019). Yet here again it meets fierce competition, when not also from its own member states. China’s scholarships website records in 2019 that 40,000 university scholarships were awarded to students from Central Asia, South America, East Asia, 85% of those carrying full funding (China also funded 2400 scholarship for Russians) (Study in China Citation2019). Russia allocates 15,000 university places annually to foreign students, with 600 of those alone allocated to Tajiks in 2019 (Sputniknews Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Demand for Russian university places from Central Asia remains high, with over 6000 Tajiks and 7000 Uzbeks applying in 2018 (Sputniknews Citation2018). Russian cultural and educational influence predicted in 2006 to be ‘here to stay’ proves enduring (Matveeva Citation2006, 79). Even with officially funded places, Central Asians can still apply beyond set numbers for places with tuition covered by the Russian state at some Russian universities. Additionally, Russian universities run numerous ‘branch’ campuses across Central Asia (and the former Soviet Union), which have been analysed to suggest that they serve to advance Russian political power and influence (Chankseliani Citation2020). The US Strategy for Central Asia tallies all engagement of Central Asians with US ‘spaces’ for learning English and American culture as 1.4 million visits annually. Over 40,000 Central Asians have received US funding for study and professional development in the United States (Bureau Citation2020, 4).

By contrast, the number of both faculty and students involved in EU–Central Asia exchanges in 2017 numbered 800 (Russell 2017, 6). The far smaller figure of 212 represented the total Erasmus+ scholarships offered to all five Central Asian states, over the period 2014–17 (Erasmus+ Citation2018). Writes one Western think tank, ‘The rather underwhelming articulation of priorities adopted in the new strategy comes with the sobering realisation that the EU inherently cannot and indeed should not try to compete for influence in numerous dimensions’ (Sahajpal and Blockmans Citation2019). The EU nevertheless considers its support of education a major and competitive strategy, even if regional observers suggest that this is insufficient and should focus on that, rather than multiple activities (e.g., Laumulin Citation2019).

Conclusions: the deafening silent references to (geopolitical) competitors

‘Not here [in Central Asia] for geopolitical interests or games,’ the EU High Representative asserted in July 2019 at the first EU–Central Asia Forum. By invoking those terms, and having other IOs with substantial EU presences, such as the OSCE, expressly reiterate the same, the EU signals that it not only eschews competition but engages Central Asia differently. True enough is that ‘the EU is always eager to present itself as a sensitive partner who has no geopolitical interests and who is empathetic and trustful’ (Spaiser Citation2018, 72). Nevertheless, the EU has carved a strategy in more than name. It is one that sidelines some international actors and augments others, of which EU states are members and which function as allies. These allies are then rhetorically deployed to maximize EU attractiveness to Central Asian governments, and to woo them onside.

The present study determines these conclusions not only by evaluating the EU’s stated objectives towards Central Asia, but also by identifying absences. Done with reference to EU aims in the Strategy and related published documents and delivered statements, those were then contrasted against other EU documents, EU-related publications and separate analyses. The unstated EU positions were examined in five issue areas to offer added perspectives on how the EU creates opportunities and minimizes challenges to itself in the region, and that in the face of competition from other extra-regional actors.

Thus, despite contrarian rhetoric, the EU seeks to amplify its attributes and deploy them against competition. In region-building the EU intends to maximize possibilities for itself by asserting, across many sectors, regional initiatives, while retaining bilateral cooperation. That even extends to devising and deploying multiple conceptions of Central Asia into wider regional formations. While representatives speak with extra-regional counterparts, EU documentation limits cooperation with Eurasian state formations such as the SCO and EAEU, despite their importance to Central Asia governments. That constitutes leverage for the EU, reinforced by offers of EU assistance to Central Asian governments for access to the resources and even membership of alternative regional and international organizations.

In trade, transportation infrastructure, and even education – sectors previously of EU pride and leadership – the EU is surpassed by competitors, particularly China. Here, too, the EU advances its comparative advantage by making available the resources of other regional and international organizations, and while ignoring the inroads made by challengers. The EU’s place in trade and the provision of infrastructure is outdone by China, yet the EU asserts its offerings to try to retain salience. These constitute competitive strategies; their relative failure makes them no less so.

The EU also engages in what can be termed ideational geopolitics – the overt assertion of its, or what it calls ‘universal’, values. Its conceptions of democracy and human rights promotion, and also the empowerment of civil society independent from the state, challenge the prevailing norms in Central Asia. By seeking to include non-state actors, even in high-level diplomatic forums, the EU is contesting values systems and seeking to advance alternative norms and practices. The EU offers comparatively little material incentivization, while overstating its capacity for investment and its regional attractiveness for any major infrastructural development.

The EU commendably crafts virtue from its uneven resources. That remains a type of geopolitical calculation, underscored by reckonings of competition. The EU casts itself as a different actor. Part of that persona is change in tone and presentation. Zhanibek Zhanibek Arynov notes how the EUSP Burian asserts the EU’s efforts ‘to avoid a “paternalistic” approach’ in the 2019 Strategy. The EU thus seeks to accommodate the ‘priorities, needs, and challenges’ of Central Asians, a measure improving on the 2007 Strategy (see also Burian Citation2019). Arynov even finds that ‘By engaging in this kind of consultation, the EU admits that the voice from the region matters for EU policy formulation’, reducing EU centricism (Arynov Citation2022). This, too, constitutes a pursuit of comparative advantage among extra-regional rivals.

Engagements between regions, like any forms of International Relations, are mutually constituting. Although perceptions of the EU have not been the present focus, Russia or China may not interpret the EU’s intentions or actions as uncompetitive or non-geopolitical, even if they do not object to the EU presence. Likely also, is that the EU is perceived as self-interested and self-serving, despite rhetoric otherwise.

The EU mobilizes its comparative offerings and tries to shape the arena of competition to its strengths, in education, legality, environmental protection and norms-based trade and infrastructural development. It seeks to be more responsive to local needs, implying contrast with others. Such is sensible diplomacy. That in itself, however, does not mean that interlocutors, indeed competitors, share those perceptions. A wider reading and contextualization of the EU’s 2019 Strategy shows omissions, likely intentional, of both the EU’s limitations and of how it has been outflanked by other actors. Irrespective of what Brussels wishes to promote, and no matter how dynamically, it interprets, responds to and faces what amounts to geopolitical competition.

Acknowledgements

An early version of this paper was presented at the ‘Transformations of EU Approaches towards Central Asia’ workshop, Brussels, Belgium, 10 July 2019, organized within the framework of the research project ‘Contested Global Governance, Transformed Global Governors? International Organisations and “Weak” States’ (GLOBALCONTEST). The author is grateful for the comments of three anonymous reviewers, as well as those of Jason Bruder, Filippo Costa Buranelli, Shair Dzhuraev, Karolina Kluczewska, Oleg Korneev and Elena Zhirukhina. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Frequently referred to as the ‘Strategy’, the EU’s 2019 policy for Central Asia has two parts. The first was presented in the name of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, as a Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, and is entitled The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, dated 15 May 2019. Because the authorship of the document is given as the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, this will appear in references as ‘High Representative (Citation2019a)’. In text, however, and in keeping with common usage, the 17-page document is called ‘The Strategy’. The second part refers to the General Secretariat of the Council, which issued on 17 June 2019 its ‘Council Conclusions on the New Strategy on Central Asia’ in which it stated that those, together, ‘provides the new policy framework for EU engagement with the countries of Central Asia’ (General Secretariat of the Council Citation2019, 2, para. 2, and its contents are so referenced hereafter).

2 Other extra-regional actors include India, which has also advocated regionalism among the post-Soviet Central Asia states, but in the present view, without palpable results. For India, see Kavalski (Citation2012, 142, passim) and Laumulin (Citation2019), who includes India. The European Parliamentary Research Service, by contrast, writes of ‘Three main players in Central Asia: Russia, China and the EU’ (Russell Citation2019, 4). The United States also has a Central Asia policy, although EU documentation makes no direct reference to cooperation (Bureau Citation2020).

3 Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine share the commonalities of being post-Soviet states and geographically located on Russia’s western and southern borders, the former being adjacent to the EU, the latter construed to be in the EU’s Black Seas region. The political, economic and foreign policy development of the six diverge substantially, as do their interests in cooperation with the EU.

4 The EU had negotiated Partnership and Cooperation Agreements, precursors to the EPCAs, that came into force in 1999 with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, and in 2000 with Tajikistan. Turkmenistan was first to sign, in 1998, but never ratified the Agreement.

5 The 2007 EU Strategy called for intensification of relations between Central Asia and NATO (Council of the European Union 2017, III, 5); the 2019 Strategy omits reference.

6 Cooley writes particularly of Russia, and in the present view applicable more widely among post-Soviet states: ‘As with the EAEU, the United States and NATO have always refused to engage with [the CSTO], which for Moscow has been further evidence of Western bad faith and Western inability to accept other organizations operating in the same geopolitical space as juridical equals’ (Cooley Citation2019, 607).

References

- Allison, R. 2008. “Virtual Regionalism, Regional Structures and Regime Security in Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 27 (2): 185–202. doi:10.1080/02634930802355121

- Amalriks, A. 2019. “A Strong and Modern Partnership.” The Parliament Magazine, December 20. https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/articles/opinion/strong-and-modern-partnership.

- Ambrose, T. 2009. Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet Union. London: Routledge.

- Arynov, Z. 2022. “Opportunity and threat perceptions of the EU in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 734–751. doi:10.1080/02634937.2021.1917516

- Axyonova, V. 2014. The European Union’s Democratization Policy for Central Asia: Failed in Success or Succeeded in Failure? Stuttgart: Ibidem.

- Azizov, U. 2017. “Regional integration in Central Asia: From knowing-that to knowing-how.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 8 (2): 123–135.

- Belarus.by. 2016. “Lukashenko: CSTO Doesn’t Have to Wait for NATO’s Recognition.” October 14. https://www.belarus.by/en/press-center/speeches-and-interviews/lukashenko-csto-doesnt-have-to-wait-for-natos-recognition_i_0000047265.html.

- Bhutia, S. 2019a. “The EU’s New Central Asia Strategy: What Does It Mean for Trade?” euasianet.org, June 5. https://eurasianet.org/the-eus-new-central-asia-strategy-what-does-it-mean-for-trade.

- Bhutia, S. 2019b. “Is New Russia–China Gas Pipeline a Threat to Turkmenistan?” eurasianet.org, December 4. https://eurasianet.org/is-new-russia-china-gas-pipeline-a-threat-to-turkmenistan.

- Boklan, D. and B. Janusz-Pawletta. 2017. “Legal challenges to the management of transboundary watercourses in Central Asia under the conditions of Eurasian Economic Integration.” Environmental Earth Sciences 76 (2017): 1–13.

- Boonstra, J. 2019. “A New EU Strategy for Central Asia: From Challenges to Opportunities.” October 3. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/new-eu-strategy-central-asia-challenges-opportunities-24062.

- Bossuyt, F. 2019. “Connecting Eurasia: Is Cooperation Between the EU, China and Russia Possible in Central Asia?” Caucasus and Central Asia Analyst, July 1. https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/feature-articles/item/13577-connecting-eurasia-is-cooperation-between-the-eu-china-and-russia-possible-in-central-asia?.html.

- Brzozowski, A. 2020. “Global Europe Brief: State of the “Geopolitical” Union.” Euractive.com, September 7. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/global-europe-brief-state-of-the-geopolitical-union/.

- Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, US State Department. 2020. United States Strategy for Central Asia 2019–2025: Advancing Sovereignty and Economic Prosperity, February 5. https://www.state.gov/united-states-strategy-for-central-asia-2019-2025-advancing-sovereignty-and-economic-prosperity/.

- Burian, P. 2019. “European Union and Central Asia: New Partnership in Action.” The Astana Times, September 9. https://astanatimes.com/2019/09/european-union-and-central-asia-new-partnership-in-action/.

- Buxton, C. 2011. The Struggle for Civil Society in Central Asia: Crisis and Transformation. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Chankseliani, M. 2020. “The Politics of Exporting Higher Education: Russian University Branch Campuses in the “Near Abroad”.” Post-Soviet Affairs (Online). doi:10.1080/1060586X.2020.1789938.

- Commission of the European Communities. 2003. Wider Europe – Neighbourhood: A New Framework for Relations with Our Eastern and Southern Neighbours, March 3. http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/enp/pdf/pdf/com03_104_en.pdf.

- Cooley, A. 2012. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cooley, A. 2013. “The League of Authoritarian Gentlemen.” Foreign Policy (Online), January 30. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/01/30/the-league-of-authoritarian-gentlemen/.

- Cooley, A. 2019. “Ordering Eurasia: The Rise and Decline of Liberal Internationalism in the Post-Communist Space.” Security Studies 28 (3): 588–613. doi:10.1080/09636412.2019.1604988

- Cornell, S., and N. Swanström. 2020. “Compatible Interests? The EU and China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Institute for Security and Development Policy, February. https://isdp.eu/publication/compatible-interests-the-eu-and-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/.

- Costa Buranelli, F. 2018. “Spheres of Influence as Negotiated Hegemony: The Case of Central Asia.” Geopolitics 23 (2): 378–403. doi:10.1080/14650045.2017.1413355

- Council of the European Union. 2007. The EU and Central Asia: Strategy for a New Partnership, May 31. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/st_10113_2007_init_en.pdf.

- Dadabaev, T. 2014. “Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Regional Identity Formation from the Perspective of the Central Asia States.” Journal of Contemporary China 23 (85): 102–118. doi:10.1080/10670564.2013.809982

- Dam, P. 2019. “The EU Must Press for an End to Repression in Central Asia at Its Kyrgyzstan Summit.” Human Rights Watch, July 8. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/08/eu-must-press-end-repression-central-asia-its-kyrgyzstan-summit.

- Directorate-General for External Policies. 2017. Russia’s and the EU’s Sanctions: Economic and Trade Effects, Compliance and the Way Forward, October. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/603847/EXPO_STU(2017)603847_EN.pdf.

- Doctor, M. 2007. “Why Bother with Inter-Regionalism? Negotiations for a European Union-Mercosur Agreement.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (2): 281–314. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00712.x

- Džankić, J., S. Keil, and M. Kmezić, eds. 2019. The Europeanisation of the Western Balkans: A Failure of EU Conditionality? London: Palgrave.

- Dzhuraev, S. 2021. “The Continuity of the EU–Central Asia Relations.” Draft Manuscript.

- EEAS. 2019. Cited as Factsheet, EU is Builds a Strong and Modern Partnership with Central Asia. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_centralasia_2019.pdf.

- EEAS. n.d. EU is the Leading Donor in Central Asia [Factsheet]. http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eu-central_asia_cooperation_infographic.pdf.

- EHEA (European Higher Education Area). n.d. Accessed April 28, 2020. http://www.ehea.info/page-full_members.

- European Commission. 2017. Overview of the Higher Education System in Central Asia. Brussels: Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/3c728d8a-6144-11e7-8dc1-01aa75ed71a1.

- European Commission. 2018. “Erasmus+ for Higher Education in Kyrgyzstan.” https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/erasmus-plus/factsheets/asia-central/erasmusplus_kyrgyzstan_2017.pdf.

- European Commission. 2019. “The European Union and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership.” [Press Release], May 15. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_2494.

- European Commission. n.d. “Erasmus+.” Accessed May 21, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/about_en, last.

- European Parliament. 2014. Joint Motion for a Resolution on the Situation in Ukraine and the State of Play of EU–Russia Relations (2014/2841(RSP)), September 17. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-8-2014-0118_EN.html.

- European Parliament. 2020. Report on Connectivity and EU–Asia Relations, December 17. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2020-0269_EN.pdf.

- Faizullaev, A. 2017. “Negotiating Security in Central Asia: Explicit and Tacit Dimensions.” In Tug of War: Negotiating Security in Eurasia, edited by F. O. Hampson and M. Troitskiy, 162–182. Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- Fawn, R. 2013. International Organizations and Internal Conditionality: Making Norms Matter. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Fawn, R. 2020. “The Price and Possibilities of Going East? The European Union and Wider Europe, the European Neighbourhood and the Eastern Partnership.” In Managing Security Threats Along the EU’s Eastern Flanks, edited by R. Fawn, 1–29. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Fawn, R., K. Kluczewska, and O. Korneev. 2022. “EU–Central Asian Interactions: Perceptions, Interests and Practices.” 41 (4): 617–638. doi:10.1080/02634937.2022.2134300

- Foley, R. 2021. “Central Asia Courts Green Energy Investors.” Eurasianet, April 15. https://eurasianet.org/central-asia-courts-green-energy-investors.

- Gallagher, K. 2018. “China Must Calibrate Overseas Lending Towards Paris Climate Goals Beijing’s Belt and Road Projects are Heavily Dependent on Fossil Fuels.” ft.com, December 10. https://www.ft.com/content/520ef0b0-fc94-11e8-ac00-57a2a826423e.

- General Secretariat of the Council. 2018. Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy – Council Conclusions (15 October 2018). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/36706/st13097-en18.pdf.

- General Secretariat of the Council. 2019. Council Conclusions on the New Strategy on Central Asia, June 17. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39778/st10221-en19.pdf.

- Gotev, G. 2018. “Astana Hosts Little-Publicised Central Asia Summit.” EURACTIV.com, March 17 and 18. https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-asia/news/fri-astana-hosts-little-publicised-central-asia-summit/.

- Gotev, G. 2019a. “Kazakhstan Advocates Closer Ties Between EU and Eurasian Economic Union.” EURACTIV.com, January 17. https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-asia/news/kazakhstan-advocates-closer-ties-between-eu-and-eurasian-economic-union/.

- Gotev, G. 2019b. ““Almost Impossible” to Rival China’s Business Clout in Central Asia.” Euractiv, October 11, https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-asia/news/almost-impossible-to-rival-chinas-business-clout-in-central-asia/.

- Hanova, S. 2022. “The Interplay of Narratives on Regionness, Regionhood and Regionality: European Union and Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 699–714. doi:10.1080/02634937.2022.2117134.

- Heathershaw, J., C. Owen and A. Cooley. 2017. “Centred discourse, decentred practice: the relational production of Russian and Chinese “rising” power in Central Asia.” Third World Quarterly 40 (8): 1440–1458. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1627867

- Heide, D., et al. 2018. “China First: EU Ambassadors Band Together Against Silk Road.” Handelsblatt, April 17. https://www.handelsblatt.com/today/politics/china-first-eu-ambassadors-band-together-against-silk-road/23581860.html?ticket=ST-844320-UlBOv6YS37cNbeHRfwNz-ap1.

- Heinecke, S. 2019. “EU–Central Asia Relations: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership? Interview with Peter Burian.” EUCACIS in Brief No. 9. Berlin: Institut für Europäische Politik. https://www.cife.eu/Ressources/FCK/EUCACIS%20in%20Brief%20No%209_final.pdf.

- Herman, O., and J. Wouters. 2019. “The OSCE as a Case of Informal International Lawmaking?” In The Legal Framework of the OSCE, edited by M. S. Platise, C. Moser, and A. Peters, 241–272. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security. 2018. Joint Communication to the European Parliament to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions, and the European Investment Bank, Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy, September 9. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_-_connecting_europe_and_asia_-_building_blocks_for_an_eu_strategy_2018-09-19.pdf.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security. 2019a. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, May 15. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_the_eu_and_central_asia_-_new_opportunities_for_a_stronger_partnership.pdf.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security. 2019b. Closing Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini at the 1st EU-Central Asia Forum, July 6. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/65103/closing-speech-high-representativevice-president-federica-mogherini-1st-eu-central-asia-forum_en.

- Hoffmann, K. 2010. “The EU in Central Asia: Successful Good Governance Promotion?” Third World Quarterly 31 (1): 87–103. doi:10.1080/01436590903557397

- ICG. 2006. Central Asia: What Role for the European Union? Report 113, April 10. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/central-asia/central-asia-what-role-european-union.

- Jones, P. 2010. “Regulatory Regionalism and Education: The European Union in Central Asia.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 8 (1): 59–85. doi:10.1080/14767720903574082

- Kavalski, E. 2012. Central Asia and the Rise of Normative Powers: Contextualizing the Security Governance of the EU, China and India. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Kluczewska, K., and S. Dzhuraev. 2020. “The EU and Central Asia: The Nuances of an “Aided” Partnership.” In Managing Security Threats Along the EU’s Eastern Flanks, edited by R. Fawn, 225–251. London: Palgrave.

- Kobayashi, K. 2019. “The Normative Limits of Functional Cooperation: The Case of the European Union and Eurasian Economic Union.” East European Politics 35 (2): 143–158. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1612370

- Kofner, Y. 2019. “Ten Reasons for EAEU–EU Cooperation.” Valdai Club, June 26. https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/ten-reasons-for-eaeu-eu-cooperation/.

- Korneev, O. 2013. “EU Migration Governance in Central Asia: Everybody's Business–Nobody's Business?” European Journal of Migration and Law 15 (3): 301–318. doi:10.1163/15718166-00002038

- Korneev, O. 2017. “Self-Legitimation Through Knowledge Production Partnerships: International Organization for Migration in Central Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (10): 1673–1690. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1354057

- Kubicek, P. 1997. “Regionalism, Nationalism and Realpolitik in Central Asia.” Europe–Asia Studies 49 (4): 637–655. doi:10.1080/09668139708412464

- Laumulin, M. 2019. “The EU’s Incomplete Strategy for Central Asia.” Carnegie Europe, December 3. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/80470.