ABSTRACT

How do new media contribute to political participation among young people? Several studies have dealt with this question; however, the question remains an understudied area in the former Soviet Union. Drawing on data collected during one year of fieldwork that included online surveys, interviews and focus groups with young people in both Russia and Kazakhstan, this study demonstrates that new media contribute to both on- and offline political participation in Russia and Kazakhstan among young people through: awareness as a prerequisite for political participation; communication; interaction; advocacy as political participation; mobilization; organizing; coordination; and hype-ization. In so doing, it offers a theoretical model that explains how new media contribute to young people’s political participation in Russia and Kazakhstan, providing an in-depth account from two post-Communist cases which can contribute to cross-national comparative studies in non-competitive statist political systems.

Introduction

New media have changed how we understand contemporary models of political participation. However, there is little investigation into the use of various new media forms and their potential influence on political participation (Dimitrova et al. Citation2014, 95). Therefore, ‘a more systematic and consistent research agenda focusing on multiplatform, multi-effect environments’ is needed ‘to shed a brighter light on the differential effects’ (Valenzuela, Correa, and Gil De Zúñiga Citation2018, 130). This suggestion is important in the context of the emerging era of Web 3.0Footnote1 because new media platforms are becoming more interlinked and they impact political participation in many ways. Consequently, it would be better not to ask whetherFootnote2 but how social-media use, such as on Twitter and Facebook, ‘translates into citizen engagement’ (Kim and Chen Citation2015, cited in Valenzuela, Correa, and Gil De Zúñiga Citation2018, 117). This study addresses this problem in two countries of the former Soviet Union: Russia and Kazakhstan. I explain how new media contribute to political participation among young people through a comparative study. Reference and comparisons are also made to findings in Western-contested electoral democracies.

Studies have found a positive relationship between new-media use and political participation of young people, particularly among students (Lane Citation2009, 114; Yamamoto, Kushin, and Dalisay Citation2015; Moeller, Kühne, and De Vreese Citation2018), who are ‘attracted to […] non-institutionalized methods of political action’ (Henn, Oldfield, and Hart Citation2018, 732). Gil de Zúñiga, Molyneux, and Zheng (Citation2014, 627) argue that ‘political expression in social media use is promising for the development of a politically active future, especially for younger people’. Recent new-media-led political events, such as the protests that erupted because of the 2018 pension reform in Russia, the 2019 presidential election in Kazakhstan and the 2019 Moscow city Duma election, highlight the complex dynamics that surround social media and internet usage for political participation among young individuals. While both Russia and Kazakhstan intend to control and manipulate the internet and social media in their territories (Anceschi Citation2015; Lewis Citation2016; Shahbaz and Funk Citation2019), including in young people’s on- and offline activism, young citizens seek to participate in politics using new media in various ways (Insebayeva Citation2019; Isaacs Citation2019; Kosnazarov Citation2019; Sairambay Citation2021a). However, it is unclear what these ways are and how young people use new media in their political participation. Therefore, by addressing this question, this study seeks to build a theoretical model of new-media-led political participation.

The choice of Russia and Kazakhstan follows the hypothesis that field research in countries with more political events in the region provides us with more fruitful findings for the how question. While Russia represents the highest number of political events among all post-Soviet Union states, Kazakhstan has experienced more extra-parliamentary citizen actions, such as protests and rallies (520 total), than any other Central Asian country in the period 2018–20 (Jardine et al. Citation2020). Moreover, internet penetration is 80% in Russia and 94% in Kazakhstan, and almost every young person (over 99%) uses the internet and social media daily in these countries (Sairambay Citation2021b). Furthermore, Russian is an official language in both countries and plays a significant role in the new-media environments of both states. The political system of Russia is considered a hybrid regime (Owen and Bindman Citation2019, 99), containing both authoritarian and competitive electoral features, while Kazakhstan’s political system is defined as a consolidated authoritarian regime (Niyazbekov Citation2018, 401). These two political systems may result in two different civic cultures of citizens. Thus, by looking at these two countries, the aim is to gain a comparative perspective in the post-Communist region to understand whether there are similarities and differences in the contributions of new media to political participation. The focus on these two countries provides an analysis of lived experiences of political participation through new-media use in ‘networked authoritarian’ conditions.

Young people’s use of new media in their political participation remains a relatively under-researched field in post-Communist countries. The paired country comparative approach is appropriate for this study because it offers a different, more intensive and robust perspective, given the lack of in-depth research on new-media use of young people in political participation in a post-Communist space, as most studies have been conducted in single-country settings (e.g., Denisova Citation2017; Bekmagambetov et al. Citation2018).

New-media-led political participation in Russia and Kazakhstan

New media’s role in state–society relations, governance, and youth engagement have been extensively discussed (Earl and Kimport Citation2011; Morozov Citation2011; Beissinger Citation2017). The internet has sharply reduced ‘costs for creating, organizing, and the participating in protest’ and the ‘need for activists to be physically together in order to act together’ (Earl and Kimport Citation2011, 10). However, it is also argued that the internet has built the delusion of liberating the world (Morozov Citation2011) and led to a ‘clicktivism’ that neglects important events with political participation being reduced to a matter of clicking online links (White Citation2010). This debate has also unfolded in the post-Soviet region.

While Kazakhstan ‘purchased a $4.3 million automated monitoring tool[s] to track signs of political discontent on social media’ in 2018, Russia has long been using online trolls and propaganda as well as ‘sophisticated social media surveillance tools’ to track the expression of political dissent (Shahbaz and Funk Citation2019). Such online surveillance and censorship have resulted in ‘networked authoritarianism’ – a term coined by MacKinnon (Citation2011, 33) – which is ‘when an authoritarian regime embraces and adjusts to the inevitable changes brought by digital communications’. Examples of ‘networked authoritarianism’ can been observed in Kazakhstan’s new-media landscape (Anceschi Citation2015, 282), and in Russian information control policy, which includes the expression of dissent via information and communication technologies (ICTs) and media (Maréchal Citation2017, 36). The blocking of Telegram (between 2018 and 2020) and the LinkedIn ban in Russia ‘are further indications that the Kremlin is serious about controlling information within its borders’ (Maréchal Citation2017, 36–37).

However, bloggers such as Alexei Navalny, Ilya Varlamov, Rustem Adagamov, Marina Litvinovich, Anton Nossik and Vladislav Naganov effectively use blogs for political mobilization in Russia (Bode and Makarychev Citation2013, 58). ‘Russia presents a difficult case’ to examine new media and political participation, as most studies are ‘focused either on mature democracies or on authoritarian regimes’ and ‘Russia falls into neither of these categories’ (Valenzuela Citation2013, cited in David Citation2015, 97). Scholarly studies that concentrate on new media and political participation in Russia more frequently examine the 2011–13 Russian protests (Sherstobitov Citation2014; White and Mcallister Citation2014; Denisova Citation2017). The driving force behind political participation in Russia from 2011 to 2012 (and later) was Russia’s ‘virtual’ civil society (Beissinger Citation2017, 359). The importance of Facebook for political mobilization during the elections and anti-regime protests in Russia was demonstrated by the 2011 Russian Election Survey, achieving a national sample of 1600 respondents, by White and Mcallister (Citation2014, 81). White and Mcallister (Citation2014, 82) found that Facebook was important for political mobilization because it is ‘US-based and less subject to Russian government interference or censorship’. VKontakte groups were also used for political communication during that electoral period, likened by one scholar to being civic non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Sherstobitov Citation2014, 165).

The Nazarbayev generation may be less inclined to challenge the Kazakhstani government compared with young people in democratic countries (Junisbai and Junisbai Citation2019, 40). Nevertheless, there is a growing scholarship that demonstrates the various alternative ways young people in Kazakhstan participate politically such as through self-actualization in lifestyle choices and expressing political identities through popular music (Insebayeva Citation2019; Isaacs Citation2019). For example, hashtag activism on social media enables young people ‘to share their political views and interact with their audiences without any mediators’ (Kosnazarov Citation2019, 264). According to cyber-pessimists (Anceschi Citation2015; Lewis Citation2016), new media, such as the internet and social media, provide the Kazakhstani regime with manipulation tools to track political dissent and thus maintain power. However, cyber-optimists (Nikolayenko Citation2015; Nurmakov Citation2017; Bekmagambetov et al. Citation2018; Kudaibergenova Citation2019) highlight the potential of new media to spread political criticism and incite resistance.

My research contributes to this debate by examining how new media facilitate young people’s political participation. It is important to study how young Russians and Kazakhstanis use new media in their political participation because they use new media more than any other (politically active) age group (over 99%) and are the driving force for political events, particularly in making demands for political change. Thus, this study confirms those existing scholarly claims about the positive relationship between new media and political participation by offering a theoretical model that provides a more detailed explanation of each step in the usage of new media by young people in their political participation.

Very few large-n studies (e.g., Bekmagambetov et al. Citation2018; Frants and Keune Citation2020) in the region have collected individual-level data on young citizens’ use of new media in political participation. Reviewing the literature, the question arises as to how young Russians and Kazakhstanis use new media in their political participation in the emerging era of Web 3.0, which contains both social media (Web 2.0) and the semantic Web.Footnote3 To my knowledge, existing scholarship does not provide a clear enough answer to this question. Emerging literature on this topic has focused on analysing citizens’ participation only in the capital and/or big cities, with little attention paid to both urban and rural areas (e.g., Bekmagambetov et al. Citation2018). This analysis simultaneously addresses young people’s political participation via new media in urban and rural areas.

Conceptualizing political participation and new media

Since the mid-twentieth century there has been a significant increase in research on political participation (Van Deth Citation2001, 5–6). Brady (Citation1999, 737) characterized political participation as ‘action by ordinary citizens directed toward influencing some political outcomes’. Other scholars describe political participation as the activities of citizens who intend to influence the decision-making of public officials (Huntington and Nelson Citation1976, 4; Parry, Moyser, and Day Citation1992, 16).

In recent years, researchers have shown a growing interest in new modes of political participation with the advent of ICTs and the internet as well as with the development of civil societies. Such developments have led to two distinct forms of political participation: ‘online’ and ‘offline’ (Shah et al. Citation2005; Gil De Zuniga, Puig-I-Abril, and Rojas Citation2009). The internet’s potential to contribute to citizens’ on- and offline political participation might be great (Graber et al. Citation2004), and compared with traditional media the internet may empower citizens with opportunities for expressive participation (Castells Citation2007). Considering the above, this study defines political participation as ‘any action by citizens that is intended to influence the outcomes of political institutions or their structures, and is fostered by civic engagement’ (Sairambay Citation2020a, 124).

New media are characterized by internet, digital technologies and interactivity as compared with traditional or old media that dominated before the information age (Vesnic-Alujevic Citation2012, 466). The idea of the Semantic Web is ‘the possibility of enabling machines to “talk to one another” and to understand and create meaning from semantic data’ (Floridi Citation2009, 27, cited in Barassi and Trere Citation2012, 1272). Fuchs (Citation2008, 127) characterizes Web 3.0 as ‘networked digital technologies that support human cooperation’. If Web 2.0 can be defined as a participative Web, Web 3.0 can be described as a collaborative Web or Semantic Web. ‘The Web is becoming a platform for linked data’ (Rudman and Bruwer Citation2016, 136) in the context ‘of multi-device, multi-channel and multi-directional throughput of information’ (Kreps and Kimppa Citation2015, 727). Thus, the current Worldwide Web (WWW) can be characterized as a mixture of Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 because there are elements of both Web developments. The present research, therefore, focuses on both participative Web 2.0 and the rising collaborative Web 3.0.

Research methodology

I applied a sequential explanatory design of mixed research methods in this research that consisted of two stages: quantitative followed by qualitative.Footnote4 The quantitative part establishes a general problem and the qualitative part elaborates on the problem in greater detail (Creswell Citation2003; Ivankova, Creswell, and Stick Citation2006).

Quantitative stage

Qualtrics was used to create and design online surveys that were conducted between July 2019 and January 2020. Considering the contemporary challenges of measuring political participation (Sairambay Citation2020b), offline political participation was measured using the question: Have you done any of the following actions in the last 12 months, if so, how many times? Online political participation was measured with the question: Have you done any of the following actions online through various online media tools (e.g., VKontakte, Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, news websites, etc.) in the last 12 months, if so, how many times? Online surveys were used to obtain a snapshot to determine how Russian and Kazakhstani young people utilize new media in their political participation.

Sampling

A multi-stage sampling method was deemed useful because it is not possible to know the population of 18–29-year aged young people who use new media: its exact number, dispersion across countries and composition. The multi-stage sampling of online surveys was comprised of three stages, which differed one from another by primary sampling units (PSUs). The first stage involved all big cities with over 1 million residents in Russia (n = 15) and Kazakhstan (n = 3), which were sampled by the simple random sampling technique. In simple random sampling, each unit of the population had an equal chance of being included in the sample. The second stage involved the cluster sampling method of randomly selecting 15 towns and 15 villages (poselki) in Russia and three towns and three villages (poselki) in Kazakhstan. Clustering was used to reduce research costs by dividing the population into clusters (known as PSUs) because a study of all towns and villages was not possible. The third stage, stratified random sampling, was followed to increase the representativeness and precision of estimates of the first- and second-stage samples by dividing the population into strata. The strata in this sampling were (1) underage (1–17 years), target population (18–29 years), older people (over 29 years); (1) young people aged 18–29 years who use new media and those who do not; and (3) local inhabitants and non-inhabitants of PSUs. Only local inhabitants, aged 18–29, who use new media were eligible to participate in the online surveys. By dividing people into these strata, I obtained research focus-oriented samples. With a confidence level of 95% and 2.83% margin of error, I calculated that the sample sizes for both Russia and Kazakhstan would need to be 1200 per country.Footnote5

The numbers of towns and villages were the same as those of big cities because all three localities within each country need to be equal to apply a probability sampling method to reduce bias and sampling error (). I excluded visitors and foreigners from the samples.

Table 1. Multi-stage sampling.

As a consequence of the above, rural and small city populations were not under-represented, because young people and their political culture might differ significantly from those who live in big urban areas. As a result, online surveys were aimed at youth in 45 localities in Russia and nine in Kazakhstan ().

Table 2. Research localities, and numbers and percentages of responses.

Distribution of online surveys

Previous research (Altayeva and Altayev Citation2018; Prins Citation2019) shows that Russian and Kazakhstani citizens mostly use VKontakte, Instagram, Facebook (and Telegram) among all available new media through which one can post research calls. Overall, I distributed surveys in 518 VKontakte, 270 Instagram, and 259 Facebook groups/pages, 164 Telegram channels and in few mailing lists of local youth NGOs and universities in order to catch young people who use new media.

Quality control

Pilot studies were undertaken amongst Russian and Kazakhstani young people in March and April 2019. As a result, participants’ feedback was taken into consideration and some minor changes were implemented. The fastest survey completion time was seven minutes, and the slowest was sixteen minutes. The online surveys with their different language links were prepared and tested by the end of June 2019. Overall, nine links were produced, of which three for Russia in Russian, and six for Kazakhstan in both Kazakh and Russian languages.

Additional data-processing checks, including checks for logic and patterning, as well as data anomalies such as duplicate cases, were taken to ensure the quality of the data. Content validity was assessed by carefully checking the measurement method against the conceptual definitions.

Qualitative stage

I conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups between October 2019 and November 2020. Interviews and focus groups were sought to elaborate on the outcomes of online surveys. The last question of the online surveys was an invitation to participate in semi-structured in-depth and focus-group interviews. Just over 30% (368) of Russian and 24% (288) of Kazakhstani survey participants showed an interest to participate further in this research in the formats of a face-to-face and/or focus-group interview. Sampling of in-depth interviews and focus groups was achieved by employing purposive sampling. Online survey participants who indicated their contacts were selected (where possible) by their preference of interview modes (in-depth or focus group), location, age, gender, nationality, education, marital status, main and current occupation, internet usage, and political interest.

Overall, 45 interviews and 20 focus groups were conducted in each country in Russian and Kazakh. All interviews and focus groups in Kazakhstani and Russian big cities were held in public venues such as cafes, university campuses, public NGO buildings and squares. However, the interviews and focus groups with young people from Russian towns and villages were a mix of both online and face to face due to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions.

Research findings and analysis

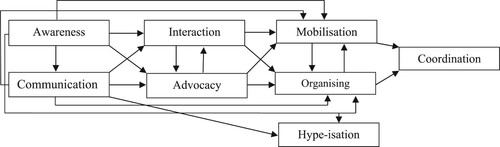

A series of diverse, but interconnected, lived experiences surrounding new-media use in political participation emerged from the interviews and focus groups with young people. Responses were analysed using thematic analysis suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): (1) familiarizing yourself with your data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report. The thematic analysis resulted in 40 codes, which were grouped into eight key themes (see Appendix A). Drawing on online surveys, interviews and focus groups, the analysis highlights eight ways in which new media assist to generate political participation in Russia and Kazakhstan among young people ().

Figure 1. Eight ways in which new media assist the political participation of young people in Russia and Kazakhstan.

These ways have already been studied but have not been integrated into a theoretical model (Whiteley and Seyd Citation2002; Vegh Citation2003; Norris Citation2005). Vegh (Citation2003) claims that online activism serves for ‘action/reaction’ (i.e., online attacks on accounts and/or computers, and the reaction of people), ‘awareness/advocacy’ (publication of information that is not covered in traditional media and drawing and/or promoting public attention to a certain idea) and ‘mobilization/organization’ (call for offline actions published in cyberspace, and the usage of online media for communication and coordination of offline activities). Political mobilization of citizens occurs ‘in response to the political opportunities in their environment and to stimuli from other people’ (Whiteley and Seyd Citation2002, 48). Such opportunities can constitute a new media environment that induces political mobilization. New media such as social media are essential in coordinating protests, namely in terms of ‘news about transportation, turnout, police presence, violence, medical services, and legal support’ (Jost et al. Citation2018, 111).

shows how the different ways new media promote political participation might be connected one to another. As we see from , awareness is the first step and a prerequisite for political participation, followed by communication. These two may lead to all other ways (interaction, advocacy, mobilization, organizing, hype-ization), except coordination, in three different steps. First, it can work as a consecutive chain including all actions except hype-ization: awareness–communication–interaction–advocacy–mobilization–organizing (and then coordination). Second, there can be non-consecutive actions that might omit some way/s, such as awareness–communication–advocacy–organizing. Third, awareness and communication might lead to immediate final action as in the following case: awareness–communication–advocacy. Coordination, as seen in , can be promoted by new media only after mobilization/ organizing.

The eight ways build a theoretical model of new media’s contributions to political participation. Through this model we get closer to a more thorough understanding of how and in what ways new media’s multifaceted nature facilitates political participation than by examining the contributions of new media with the isolated concepts of political mobilization. I contend that the ways highlighted in the model are interconnected and young citizens’ new-media usage usually changes from one way to another, which can illustrate the eventual characterization of users’ political culture (e.g., subject, participant, parochial) in certain flashpoints such as elections and political stress. For example, one can organize a political event using new media and be characterized as a participant by Almond and Verba (Citation1963), but before political organizing one passes some ways such as online political awareness, communication, interaction or even advocacy; however, other organized participants might take part in the political event of the organizer, after being exposed to only online political awareness (e.g., reading the organizer’s post, showing political interest and a standpoint through ‘liking’ the post, then making the decision to participate). Each way is elaborated upon in the subsections that follow.

Political awareness as a prerequisite for political participation

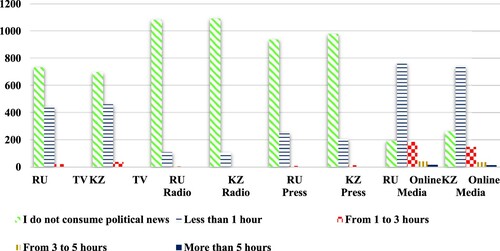

In this study, political awareness means being informed about ongoing political affairs in at least one of the following scales: local, countrywide, international or global. The results of my online surveys show that in the month preceding their completion of the survey, nearly three out of four young Russian and Kazakhstani people read and watched political posts/news and videos online, while almost every other person listened to political audio recordings. Online media is the most extensively used media for political news among young people in both Russia and Kazakhstan ().

In promoting political news/posts, social media play a significant role. Even those who are not members of political news groups may be exposed to political posts because of their friends or their news feeds, if they are about something important and popular. Digital technologies such as smartphones and laptops were appreciated for keeping young people updated at any time and place where the internet is available. The smartphone is the most used (over 90%) digital technology with internet access among both Russian and Kazakhstani respondents.

The idea that political awareness might be translated into political participation is supported by focus-group (FG) data (e.g., Moscow FGs 1 and 2, Almaty FG 1), but with one condition. A political stress or an issue that affects individuals must be present. It seems new media assist in moving people from subjects to participants or contestants, as awareness of ongoing politics is one prerequisite to participation.

Some interviewees (e.g., loyal, state activists, those with a high quality of life or those disinterested in politics) accused political protesters of being stupid, unorganized people with no political agenda. For example, one respondent stated:

I see no reason to protest […] While the opposition does not reflect my views, I see no reason to support protests and rallies […] It seems to me useless. Protestors in Moscow are not well-organised. Most of them are stupid with no goals. (Misha, 22, analyst, Moscow)Footnote6

When high-profile cases happen in Kazakhstan, I check the Instagram of Dosym Satpayev because he comments on these types of events regularly. He helps me to view the cases from different angles. (Daulet, 24, internal auditor, Nur-Sultan)

Probably one of the most watched video bloggers nowadays is Dud. (Sergey, 18, student, FG 1, Moscow)

Yes, he makes interviews so cool. He takes interviews with famous people, including politicians, in his own unique way. (Lubov, 21, unemployed, FG 1, Moscow)

Görtz (Citation2018, 14) conducted a meta-analysis of 70 articles on the significance of political awareness and found that ‘political awareness strongly affects both public opinion and political participation’. The findings of this research share similar conclusions, situating new-media-assisted political awareness at the onset of political participation.

Political communication

In this study, political communication refers to sharing political information both on- and offline. According to the results of online surveys, almost every second Russian and Kazakhstani young person spends in total more than five hours on the internet, whereas 40.75% of Russian and 36.42% of Kazakhstani respondents showed that they use the internet between three and five hours on an average weekday. Instagram, WhatsApp, VKontakte and YouTube are the most used (over 85% of users in each country) social media among young people. Trailing these four types of social media, Telegram is becoming popular especially in cities and towns.

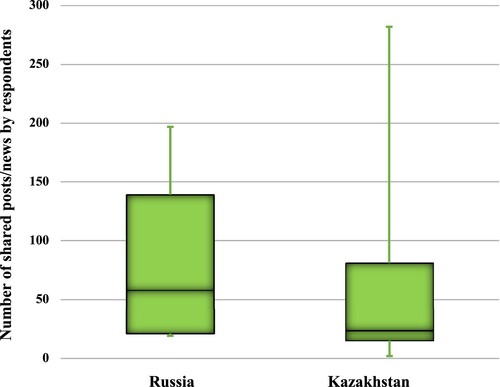

Young people not only consume political news and posts, but also share or repost them, sometimes using multiple social-media tools. Of the 2400 respondents who completed the online surveys, just over half in big cities and just over 43% in towns in Russia and Kazakhstan indicated that they had shared political posts/news on social media in the last month from once to daily. Yet, in response to this question, few participants (20%) from Russian villages showed that they had done so, and this action is nearly twice as infrequent (9.5%) among young Kazakhstani villagers. and display and compare the distribution and spread (variability) of scores found in responses of the respondents who shared political posts/news on social media.

Table 3. Respondents who shared political posts/news on social media: descriptive statistics.

Minimum and maximum here are defined by the largest and smallest value of the specific answer options within a given range of all answers.

While the Kazakhstani sample’s range is higher than that in Russia, Russian interquartile range (IQR)Footnote7 is higher than Kazakhstani. This means that Russian positive responses are less skewed by a small number of extremely high or low values, while Kazakhstani positive responses vary greatly. Thus, the median is larger in the Russian sample than in Kazakhstani one. Therefore, the frequency (from once to twice to everyday) of shared political posts/news on social media were somewhat more evenly distributed in Russia than in Kazakhstan.

Drawing from a three-wave dataset, Zhu, Chan, and Chou (Citation2020) found that online political communication on social media significantly facilitated radical political participation among young people in Hong Kong. Even in less open and more autocratic societies such as Russia and Kazakhstan, an increasing number of political institutions and their structures are adopting social media for communication with citizens. This in turn leaves more room for active political communication, especially amongst social-media users.

In addition to providing information, political communication often also facilitates political awareness and online activism. Many participants began by liking, commenting on or, like Anton (20, student, Moscow), sharing political posts on multiple online platforms, hashtagging before taking political actions. Thus, we can note that communication enhances awareness of young people through new media, which offer multiple platforms and opportunities to create and share political news and posts.

Political interaction

Political interaction is here understood as the communication of people with the intention to affect one another in relation to certain political issues. Interaction somewhat overlaps with communication, but it is more about affecting others rather than just sharing information. The common methods of interaction to assist young people in political participation are online actions such as private messages, comments, posts, reposts, blogs, vlogs and offline actions in the form of a discussion. Interaction can be either the next step of political participation after communication or an isolated action that does not require prior communication.

The frequencies of respondents’ discussions about online political posts/news with their friends, family members and colleagues are shown in . Respondents indicated that they discussed online political news/posts more with their friends because young people seem to trust and understand their peers more than family members or colleagues (e.g., groupmates, co-workers, boss, etc.). For example, the following respondents noted:

I discuss online political posts more with my friends because my parents trust more in news on TV and our viewpoints often differ […] It is easy to speak out fully with friends than parents, you know […]. (Dima, 19, student, Chelyabinsk)

It is sometimes difficult to discuss political news with colleagues because of workplace ethics. For example, I signed a job contract stating that I will not be engaged in political affairs during the working hours. (Daulet, 24, internal auditor, Nur-Sultan)

However, other participants argued that not all family members and colleagues have an online presence to discuss political news or posts. This could be one explanation for why friends are popular for online discussions. Yet, this does not mean that young people do not discuss political news or posts with family members or colleagues – much depends on the new-media use of family members, job places, political interests and most importantly news/posts.

Table 4. Frequencies of respondents’ discussions about online political posts/news.

Political advocacy as political participation

Political advocacy is defined as people’s support for public causes. Young people use new media to advocate political issues through petitions, demonstrations, blogging on political themes, writing political posts on social media or on websites, and reposting those political posts. Over half of the young people who signed e-petitions are city-dwellers in Russia and Kazakhstan. The popular platforms for online petitions that interviewees pointed out are change.org, avaaz.org and petitions247.com. Sometimes consciously refraining from signing petitions also means political participation for some participants. One argued that he had not signed an online petition to reduce the area of a square in Oskemen because the petition did not meet his expectations (Abay, 22, college teacher, FG 2, Oskemen).

One interviewee, who had participated in protests more than 10 times, said: ‘Posts urging us to take a walk at 19:00 on the Square at the Drama Theatre began to appear on social media from advocates of the Square on 13 May [2019]’ (Gleb, 24, political activist, Yekaterinburg). As a result, the organized walk was translated into mass protests that lasted several days. Residents of Yekaterinburg opposed the construction of a new church on the square at the Drama Theatre and won the case. This shows an interesting way to mobilize people, namely using advocacy to cause mobilization (see step 2 in ).

Advocacy is not only about citizen initiatives directed towards the political institutions or their structures. It might also be aimed at other citizens, such as through supporting the government. One such case can be observed during the presidential elections in Kazakhstan:

I helped to block many accounts using the ‘complain’ button on Facebook to citizens’ various posts about an unfair election during the [2019] presidential election day from about 7 pm, when it was about to end, until 1 am When the number of ‘complaints’ reaches 10, the user is blocked on Facebook. There were approximately 50 people in the room where we were doing this. […] One of the organisers sent out posts by citizens about the unfair election to our general WhatsApp group that had over 200 people. We barely managed to block the authors who were posting about the unfairness of the election. We were given fake phone numbers to register ourselves on different social media and comment on their posts from mobile phones and laptops, improvising that the election was fair. […] It was organised by the ‘Nur Otan’ party in the building of the [largest youth movement in Almaty] ‘League of Volunteers’. Before this day, on pre-election silence day, each of us was given 20.000 KZT for our volunteering during the electoral campaigns. (Sultan, 19, volunteer student, Almaty)

Whilst only a small number (36 out of 1200) of Kazakhstani respondents indicated that they had participated in demonstrations from one to more than 10 times, this action had been done by nearly one in six Russian respondents. A monstration was a term first used to describe one type of demonstrations in one of my interviews in Yekaterinburg (Albina, 28, journalist). Later an interviewee in Perm (Nina, 26, Russian teacher) and the focus-group participants in Nizhny Novgorod also mentioned it. The monstration is a mass demonstration with art slogans and banners that participants use for expression and communication with their audience. In other words, it is a parody rally and primarily a Russian phenomenon (Astapkovich Citation2013).

While some young people simply share political posts (communication), others advocate (advocacy). As one respondent noted: ‘sharing information on social media is caring about your community’ (Pasha, 21, student, Moscow). Sharing political news/posts already signifies activism to some extent for some young people, which facilitates political participation being characterized essentially as communication. Focus-group participants emphasized how news/posts gained tremendous popularity and use of new media empower advocacy, assisting them to reach many individuals ranging from activists to those who have never heard of the advocated issues before.

Political mobilization

New media might assist in mobilizing young people. Political mobilization refers to offline actions such as protests and rallies that are directed at influencing political institutions or their structures. Study participants had mixed lived experiences illustrating the complexity of new-media-led political mobilization: much depends on, for example, the mode of mobilization; the nature of mobilization; and organizers’ use of new media, all of which affect both political interest and decision-making to participate and impact upon participants’ sense of civic duties.

The results of online surveys show that one-fifth (22.83%) of Russian and 1/20th (4.92%) of Kazakhstani respondents took part in a rally or protest. A contingency table shows differences in the gender and age distributions of these protestors ().

Table 5. Respondents who participated in rallies or protests, 2018–19.

As we see from , the most active protestors were youth aged 21 and under, except in the case of Russian villagers. Men protested more than any other gender in cities and villages in both countries. While women were more active in Russian towns, an equal number of men and women took part in protests and rallies in Kazakhstani towns.

Interestingly, some respondents also showed that they had occupied a building and/or road from one to 10 times: 19 in big cities, 13 in towns and 10 in villages of Russia; six in Kazakhstani big cities and only one in a town called Oskemen. One interviewee informed me that Moscow had a very active summer in 2019 with regards to political participation, noting: ‘On 27th of August, I allowed myself to walk on the roads with other protesters and even went out onto the Garden Ring (Sadovoye Koltso)’ (Anton, 20, student, Moscow).

The presence of social media, such as Facebook, and related positive experiences of protests generate a sense of democratic functioning and contentment. Participants in the focus groups in Yekaterinburg spoke of being proud of becoming the most democratized city in Russia. The members of the focus group were very satisfied with the outcomes of the ‘Church versus Square’ protests (FG 2, Yekaterinburg), stating that other cities and towns of Russia should learn from Yekaterinburg. All of this illustrates a new civic culture with the increasing levels of participation and contestation.

Political organizing

Political organizing is referred as any online action that relates to planning political activities through new media. It might include, for example, deciding about the date, time and venue of political actions. According to my surveys, young people in both countries participated more in collective political actions (e.g., protests, strikes, demonstrations, etc.) organized by other people through new media than those organized by themselves, with the majority of those actions organized by someone they did not know personally. Moreover, respondents pointed out that they had taken part in collective political actions more of their own free will rather than under the influence of third parties.

A total of 94 young Russians (7.83%) and 12 Kazakhstani young people (0.99%) had organized demonstrations online from one to 10 times. While for some participants ‘demonstration’ refers to a campaign to show awareness, for others it means something like a protest. Although very few participants (0.83%) revealed that they had organized rallies or protests online in Kazakhstan, the use of various online-media tools to organize protests by Russians (8.33%) is maturing. For example, one participant noted:

We have a VK group called NTSP. We (with my friends) created this group to be about political interests. We discuss our ideology and opinions there. Sometimes we organise meetings to discuss political events. In the summer [of 2019], for example, we used this VK group to organise our rallies in Moscow. (Kolya, 18, college student, Moscow)

One interesting finding is so-called metro-pickets. One respondent noted how: ‘on Fridays, there are metro-pickets – people sign up on Telegram and picket at the metro stations in support of political prisoners’ (Anton, 20, student, Moscow). Picketing is popular because it is legal and therefore young people are not afraid to picket. Young people choose public venues, such as the metro; governmental institutions, such as Ministry of Internal Affairs; or international institutions, such as embassies or media outlets, to make their picketing more visible to a wider audience.

Another interesting case was revealed in one of the focus groups in Nur-Sultan where members of the group shared an incident that had happened during the ‘Nur Otan’ forum. Students, who had been forced to attend many rehearsals in support of the party’s presidential candidate did not shout slogans at the forum as they had in rehearsals. The focus group members said that these students wanted to show their discontent with the forced rehearsals and the idea had been circulated over social media (FG 1, Nur-Sultan). This shows when political awareness through social media results immediately in political interaction and organizing (see step 3 in ).

Taken together, we can observe that new media already assist young people in organizing political activities in both Russia and Kazakhstan. They make it easy to reach a wider audience, arrange a specific time and place for a political activity, or agree on specific tactics such as seen in Nur-Sultan.

Political coordination

Political coordination is another way by which new media might assist young people to participate in politics. This research interprets political coordination as planning activities using new media that follow political organizing. If political organizing is about the initial planning of political actions, political coordination refers to the next steps in planning the same organized political activities. That is, political coordination denotes the more extensive organizing of political actions, for instance, by providing immediate information about new routes for protestors during rallies.

While 111 Russians (9.25%) indicated that they had coordinated rallies or protests online, it was only five in Kazakhstan (0.42%). Just as in the case of organizing work-related strikes, no one had ever coordinated a strike among Kazakhstani participants. Similarly, as in organizing strikes in Russia, only 19 Russian respondents in big cities, three in towns and three in villages had coordinated strikes from one to four times, using various online-media tools. While one in every 12 young Russians had coordinated demonstrations through different new media from one to 10 times, only eight out of 1200 Kazakhstani respondents had done so once or twice.

Apart from collective political actions such as protests, strikes and demonstrations, there were also questions about organizing and coordinating political events in the online survey. The survey shows that the numbers of young people who organized and coordinated political events were quite similar, around 10% in Russia and 1.5% in Kazakhstan. One of the interviewees described his coordination of single pickets in support of Yegor Zhukov through Telegram:

In the public domain people could write to me and I discussed with every volunteer so that no one wastes time and comes when it is convenient for them. For instance, one stands at one point and the next person replaces him/her and continues to picket. I had coordinated these pickets until I was arrested and sentenced. (Anton, 20, student, Moscow)

It is interesting to observe how new-media tools such as Telegram, Instagram and Facebook are preferred over other new media such as VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Twitter, Skype or Viber in coordinating offline political actions. Research participants said that livestreams on Facebook and Instagram during the political actions ease the coordination, as active citizens and potential participants can follow the coordinators. VKontakte and Odnoklassniki were understood to be as pro-government social media managed by Mail.ru Group, and therefore less popular for political coordination. Telegram, on the contrary, makes it possible to coordinate anonymously and/or avoid interference (or at least minimizes the risk of interference) according to young people. Many focus-group participants agreed that Twitter, Skype and Viber are not popular in coordination simply because these new media are less used by citizens in both countries. Yet sometimes these media tools can be used at the same time in coordination. Storsul (Citation2014, 22) argues that politically engaged young people employ social media, especially Facebook, for planning and coordinating their political activities. One good example of political coordination through new media is the Milla (One Million for the Freedom of the Press in Hungary) case, which was organized and coordinated using Facebook eight times against the Fidesz government’s media law throughout Hungary (Wilkin, Dencik, and Bognár Citation2015, 691). All Moscow respondents in my study mentioned similar initial planning and subsequent coordination online in reference to the summer 2019 Moscow protests.

Hype-ization

One method young people shared during the research, interpreted here as hype-ization, is when new media assist to generate political participation because of hype and/or fashion to boost one’s popularity and/or to earn followers in social media. One example of hype-ization was given by a Moscow student during the face-to-face interview:

A graduate student of the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics is a political prisoner […] and we put big bed sheets there – one letter – one bed sheet – as #FREEAZAT opposite the main building of Moscow State University and then we sent them to several dozens of media outlets […] thus, we hyped a little bit. [Me:] ‘Online?’ Yes, yes, well, the photos were displayed with a description and sent out. (Pasha, 21, student, Moscow)

Hype-ization is especially prevalent among teenagers, including those who are under 18, as non-institutionalized political actions such as protests or demonstrations do not require an age limit. One example was given by a college student in Moscow:

[…] There is also another side of social media and political participation. I know one schoolboy aged 17 who participated in the Moscow protests in the summer and constantly filmed his participation on Instagram. He became a school’s hero – classmates applauded him standing when classes began in September. His main goal was to earn popularity, showing he is cool and participates in protests. (Kolya, 18, college student, Moscow)

In general, group feelings about hype-ization in Kazakhstan were that most young people did not know any examples or experiences of such cases, whereas in Russia they varied. For example, only one out of seven participants in a focus group held in Almaty confirmed that there are some youngsters who use new media for hype. For instance, one participant noted that:

There are some teenagers and I know them. My aunt works at a school. She told me of how students in grades 8 and 9 laughed and filmed how they were protesting near the municipal government [Akimat] with posters. They did so for Likee [a short video creation and sharing app], which is similar to TikTok. (Ademi, 24, interior artist, FG 2, Almaty)

One explanation for political participation among 18–19-year-old young people relates to when they are allowed to act legally in politics, for instance, in voting. For some teenage participants, voting for the first time was the main reason for voting. As one focus-group participant commented:

I voted because this is my first election. It was interesting to vote for me. I also took a picture of how I cast my vote and posted it on Instagram and then shared it on Facebook and VKontakte. (Mansur, 19, student, FG 2, Shymkent)

According to participants, peer pressure on social media might also lead some people to participate in politics to improve credibility. For instance, challenging peers during voting through sharing voting pictures and tagging names on posts might be considered peer pressure for some young people. There could be more pressure especially when someone tags one’s friend with another bunch of friends. As a result, young people who stay away from politics might act offline to show that they are also actively engaged in the political life of their society.

Conclusions

In this study, I used data from online surveys and fieldwork in Russia and Kazakhstan to show how new media contribute to political participation among young Russian and Kazakhstani citizens. Various political events that took place in Russia and Kazakhstan in recent years highlight the complex dynamics of new-media use in the political participation of young people. Those who were active both on- and offline showed how new media facilitate their political participation. Young people from both countries have shown similar levels of engagement in awareness, communication, interaction and advocacy, while young people in Russia have used new media more in mobilization, organizing, coordination and hype-ization than Kazakhstani youth. These eight ways, by which new media assist to generate political participation, pertain to the individual and group perspectives of young Russian and Kazakhstani citizens.

According to the results of this study, young people are active politically not only in cities, as one would expect, but also in towns, and even in some villages. Online political participation, which can induce offline political participation, is promoted independently of the physical locations of young people owing to the internet and digital devices. It was revealed that young people in both countries use independent new-media tools such as Telegram, Facebook and YouTube for non-institutionalized political actions. The fact that Russia and Kazakhstan have similar concentrations of new-media ownership can be an obstacle to using new media for extra-parliamentary political activities.

Overall, the emerging era of Web 3.0, which contains both social media (Web 2.0) and the Semantic Web, provides multiple venues to participate in politics. Russian and Kazakhstani young people do not refrain from taking advantage of new media in their political participation, despite the minimal openness of their societies. New media not only make young people aware of political issues surrounding them, but also assist them acting as activists, advocators, organizers and coordinators of political actions both on- and offline.

The findings of this investigation complement those of earlier studies (e.g., mobilization, interaction, coordination) and integrate them into a theoretical model, which can be tested, for example, in other ‘networked authoritarian’ settings. Thus, further studies need to be carried out to compare the experiences of individuals in new-media-led political participation with those in other parts of the world in order to cross-check the eight ways highlighted here and the relations between them. Further research could also assess the regressions or correlations between the variables to examine which of them are related to the inclination to participate in different ways.

Acknowledgements

Most of all, I thank my supervisor, Dr David Lane (Emeritus Fellow, Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge), for his constant advice, comments and support. I am equally grateful to three anonymous reviewers and the journal editor, Dr Rico Isaacs, for their time and comments which helped to shape this article. My special thanks go to Mr Nathaniel Skylar Dolton-Thornton (universities of Cambridge and Oxford) for his effective writing advice. Moreover, I would like to thank all this study's participants for their time and thoughts. An earlier draft of this paper was presented and discussed in the Fifth Annual Tartu Conference on Russian and East European Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia, 6–8 June 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Web 3.0 is a collaborative and Internet of Things Web (Kreps and Kimppa Citation2015, 726), which includes the ‘ability to categorize and manipulate data to enable machines to understand data and the phrases describing data’, as well as the creation and sharing of ‘all types of data over all types of networks by all types of devices and machines’ (Verizon Citation2015, cited in Rudman and Bruwer Citation2016, 136–37).

2 Much empirical research (e.g., Boulianne Citation2015; Skoric et al. Citation2016) suggests that there is a positive relationship between new media and political participation.

3 The semantic Web is ‘the possibility of enabling machines to “talk to one another” and to understand and create meaning from semantic data’ (Floridi Citation2009, 27, cited in Barassi and Trere Citation2012, 1272).

4 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge, on 4 June 2019.

5 The calculation was made using www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html.

6 All names in parentheses are pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

7 The robust measure of scale, which describes the middle 50% of values when ordered from lowest to highest.

References

- Almond, G. A., and S. Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Altayeva, A., and A. Altayev. 2018. “Social Networks in the Information and Communication Space of Kazakhstan.” KazNU BULLETIN. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://articlekz.com/en/article/18724.

- Anceschi, L. 2015. “The Persistence of Media Control Under Consolidated Authoritarianism: Containing Kazakhstan’s Digital Media.” Demokratizatsiya 23 (3): 277–295.

- Astapkovich, V. 2013. “Russian Labor Day: Rallies, Ridicule and Revelry as Tens of Thousands Take Part.” Russia Today, May 1. https://www.rt.com/russia/labor-day-russia-politics-671/.

- Barassi, V., and E. Trere. 2012. “Does Web 3.0 Come After Web 2.0? Deconstructing Theoretical Assumptions Through Practice.” New Media & Society 14 (8): 1269–1285. doi:10.1177/1461444812445878

- Beissinger, M. 2017. “‘Conventional’ and ‘Virtual’ Civil Societies in Autocratic Regimes.” Comparative Politics 49 (3): 351–371. doi:10.5129/001041517820934267

- Bekmagambetov, A., K. Wagner, J. Gainous, Z. Sabitov, A. Rodionov, and B. Gabdulina. 2018. “Critical Social Media Information Flows: Political Trust and Protest Behaviour among Kazakhstani College Students.” Central Asian Survey 37 (4): 526–545. doi:10.1080/02634937.2018.1479374

- Bode, N., and A. Makarychev. 2013. “The New Social Media in Russia: Political Blogging by the Government and the Opposition.” Problems of Post-Communism 60 (2): 53–62. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600205

- Boulianne, S. 2015. “Social Media Use and Participation: A Meta-Analysis of Current Research.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (5): 524–538. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brady, H. E. 1999. “Political Participation.” In Measures of Political Attitudes, edited by J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, and L. S. Wrightsman, 737–801. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Castells, M. 2007. “Communication, Power and Counter-Power in the Network Society.” International Journal of Communication 1 (1): 238–266.

- Creswell, J. W. 2003. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- David, M. 2015. “New Social Media: Modernisation and Democratisation in Russia.” European Politics and Society 16 (1): 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2014.965892

- Denisova, A. 2017. “Democracy, Protest and Public Sphere in Russia After the 2011–2012 Anti-Government Protests: Digital Media at Stake.” Media, Culture & Society 39 (7): 976–994. doi:10.1177/0163443716682075

- Dimitrova, D. V., A. Shehata, J. Strömbäck, and L. W. Nord. 2014. “The Effects of Digital Media on Political Knowledge and Participation in Election Campaigns: Evidence from Panel Data.” Communication Research 41 (1): 95–118. doi:10.1177/0093650211426004

- Earl, J., and K. Kimport. 2011. Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in The Internet Age. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Floridi, L. 2009. “Web 2.0 vs. the Semantic Web: A Philosophical Assessment.” Episteme 6 (1): 25–37. doi:10.3366/E174236000800052X

- Frants, V. A., and O. Keune. 2020. “The Role of Digital Communication in Spreading Socio-Political Protest Moods among Russian Urban Youth (Using the Example of Yekaterinburg).” Communications. Media. Design 5 (3): 5–22.

- Fuchs, C. 2008. Internet and Society: Social Theory in the Information Age. New York: Routledge.

- Gil De Zuniga, H., E. Puig-I-Abril, and H. Rojas. 2009. “Weblogs, Traditional Sources Online and Political Participation: An Assessment of How the Internet is Changing the Political Environment.” New Media & Society 11 (4): 553–574. doi:10.1177/1461444809102960

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., L. Molyneux, and P. Zheng. 2014. “Social Media, Political Expression, and Political Participation: Panel Analysis of Lagged and Concurrent Relationships.” Journal of Communication 64 (4): 612–634. doi:10.1111/jcom.12103

- Görtz, C. 2018. “The Significance of Political Awareness: A Literature Review with Meta-Analysis.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research General Conference Article, Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, August 22–25. Accessed May 2, 2020. https://ecpr.eu/Events/PaperDetails.aspx?PaperID=41664&EventID=115.

- Graber, D. A., B. Bimber, W. L. Bennett, R. Davis, and P. Norris. 2004. “The Internet and Politics: Emerging Perspectives.” In Academy and the Internet, edited by H. F. Nissenbaum, and M. E. Price, 90–119. New York: Peter Lang.

- Henn, M., B. Oldfield, and J. Hart. 2018. “Postmaterialism and Young People’s Political Participation in a Time of Austerity.” The British Journal of Sociology 69 (3): 712–737. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12309

- Huntington, G., and J. M. Nelson. 1976. No Easy Choice: Political Participation in Developing Countries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Insebayeva, S. 2019. “Visions of Nationhood Youth, Identity and Kazakh Popular Music.” In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan, edited by M. Laruelle, 177–190. New York: Lexington Books.

- Isaacs, R. 2019. “The Kazakhstan Now! Hybridity and Hipsters in Almaty. Negotiating Global and Local Lives.” In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan, edited by M. Laruelle, 227–243. New York: Lexington Books.

- Ivankova, N. V., J. W. Creswell, and S. L. Stick. 2006. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1177/1525822X05282260

- Jardine, B., S. Khashimov, E. Lemon, and A. Uran Kyzy. 2020. “Mapping Patterns of Dissent in Eurasia: Introducing the Central Asia Protest Tracker.” Accessed June 7, 2021. https://oxussociety.org/mapping-patterns-of-dissent-in-eurasia-introducing-the-central-asia-protest-tracker/.

- Jost, J. T., P. Barberá, R. Bonneau, M. Langer, M. Metzger, J. Nagler, J. Sterling, and J. A. Tucker. 2018. “How Social Media Facilitates Political Protest: Information, Motivation, and Social Networks.” Advances in Political Psychology 39 (1): 85–118. doi:10.1111/pops.12478

- Junisbai, B., and A. Junisbai. 2019. “Are Youth Different? The Nazarbayev Generation and Public Opinion.” In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan, edited by M. Laruelle, 25–48. New York: Lexington Books.

- Kim, Y., and Chen, H. 2015. “Discussion Network Heterogeneity Matters: Examining a Moderated Mediation Model of Social Media Use and Civic Engagement.” International Journal of Communication 9: 2344–2365.

- Kosnazarov, D. 2019. “#Hastag Activism: Youth, Social Media, and Politics.” In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan, edited by M. Laruelle, 247–268. New York: Lexington Books.

- Kreps, D., and K. Kimppa. 2015. “Theorising Web 3.0: ICTs in a Changing Society.” Information Technology & People 28 (4): 726–741. doi:10.1108/ITP-09-2015-0223

- Kudaibergenova, D. 2019. “The Body Global and the Body Traditional: A Digital Ethnography of Instagram and Nationalism in Kazakhstan and Russia.” Central Asian Survey 38 (3): 363–380. doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1650718

- Lane, D. 2009. “‘Coloured Revolution’ as a Political Phenomenon.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 25 (2–3): 113–135. doi:10.1080/13523270902860295

- Lewis, D. 2016. “Blogging Zhanaozen: Hegemonic Discourse and Authoritarian Resilience in Kazakhstan.” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 421–438. doi:10.1080/02634937.2016.1161902

- MacKinnon, R. 2011. “China’s “Networked Authoritarianism”.” Journal of Democracy 22 (2): 32–46. doi:10.1353/jod.2011.0033

- Maréchal, N. 2017. “Networked Authoritarianism and the Geopolitics of Information: Understanding Russian Internet Policy.” Media and Communication 5 (1): 29–41. doi:10.17645/mac.v5i1.808

- Moeller, J., R. Kühne, and C. De Vreese. 2018. “Mobilizing Youth in the 21st Century: How Digital Media Use Fosters Civic Duty, Information Efficacy, and Political Participation.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 62 (3): 445–460. doi:10.1080/08838151.2018.1451866

- Morozov, E. 2011. The Net Delusion: How Not to Liberate the World. London, UK: Penguin.

- Nikolayenko, O. 2015. “Youth Media Consumption and Perceptions of Electoral Integrity in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” Demokratizatsiya 23 (3): 257–276.

- Niyazbekov, N. 2018. “Is Kazakhstan Immune to Color Revolutions? The Social Movements Perspective.” Demokratizatsiya 26 (3): 401–425.

- Norris, P. 2005. “The Impact of the Internet on Political Activism: Evidence from Europe.” International Journal of Electronic Government Research 1 (1): 20–39. doi:10.4018/jegr.2005010102

- Nurmakov, A. 2017. “Social Media in Central Asia.” In Central Asia at 25: Looking Back, Moving Forward. A Collection of Essays from Central Asia, edited by M. Laruelle, and A. Kourmanova, 74–76. Central Asia Program (CAP). Washington: the George Washington University.

- Owen, C., and E. Bindman. 2019. “Civic Participation in a Hybrid Regime: Limited Pluralism in Policymaking and Delivery in Contemporary Russia.” Government and Opposition 54 (1): 98–120. doi:10.1017/gov.2017.13

- Parry, G., G. Moyser, and N. Day. 1992. Political Participation and Democracy in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Prins, N. 2019. “An Analysis of the Russian Social Media Landscape in 2019”. Accessed June 10, 2019. https://www.linkfluence.com/blog/russian-social-media-landscape.

- Rudman, R., and R. Bruwer. 2016. “Defining Web 3.0: Opportunities and Challenges.” The Electronic Library 34 (1): 132–154. doi:10.1108/EL-08-2014-0140

- Sairambay, Y. 2020a. “Reconceptualising Political Participation.” Human Affairs 30 (1): 120–127. doi:10.1515/humaff-2020-0011

- Sairambay, Y. 2020b. “The Contemporary Challenges of Measuring Political Participation.” Slovak Journal of Political Sciences 20 (2): 206–226. doi:10.34135/sjps.200202

- Sairambay, Y. 2021a. “Политические Культуры и Новые Медиа России и Казахстана [Political Cultures and New Media in Russia and Kazakhstan].” Подкасты CEURUSа, June 23. Accessed August 7, 2021. https://anchor.fm/ceurus/episodes/8-e139i99.

- Sairambay, Y. 2021b. “Internet and Social Media Use by Young People for Information About (Inter)National News and Politics in Russia and Kazakhstan.” Studies of Transition States and Societies. (Accepted and Forthcoming).

- Shah, D. V., J. Cho, W. P. J. R. Eveland, and N. Kwak. 2005. “Information and Expression in a Digital Age: Modeling Internet Effects on Civic Participation.” Communication Research 32 (5): 531–565. doi:10.1177/0093650205279209

- Shahbaz, A., and A. Funk. 2019. “Freedom on the Net 2019 Key Finding: Governments Harness Big Data for Social Media Surveillance.” Freedom House. Accessed March 6, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-on-the-net/2019/the-crisis-of-social-media/social-media-surveillance.

- Sherstobitov, A. 2014. “The Potential of Social Media in Russia: From Political Mobilization to Civic Engagement.” Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Electronic Governance and Open Society: Challenges in Eurasia, 162–166. doi:10.1145/2729104.2729118

- Skoric, M., Q. Zhu, D. Goh, and N. Pang. 2016. “Social Media and Citizen Engagement: A Meta-Analytic Review.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1817–1839. doi:10.1177/1461444815616221

- Storsul, T. 2014. “Deliberation or Self-Presentation?: Young People, Politics and Social Media.” Nordicom Review 35 (2): 17–28. doi:10.2478/nor-2014-0012

- Valenzuela, S. 2013. “Unpacking the Use of Social Media for Protest Behavior: The Roles of Information, Opinion Expression and Activism.” American Behavioral Scientist 57 (7): 920–942. doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479375

- Valenzuela, S., T. Correa, and H. Gil De Zúñiga. 2018. “Ties, Likes, and Tweets: Using Strong and Weak Ties to Explain Differences in Protest Participation Across Facebook and Twitter Use.” Political Communication 35 (1): 117–134. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1334726

- Van Deth, J. W. 2001. “Studying Political Participation: Towards a Theory of Everything?” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research, April, 1–19.

- Vegh, S. 2003. “Classifying Forms of Online Activism: The Case of Cyberprotests Against the World Bank.” In Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and Practice, edited by M. McCaughey, and M. D. Ayers, 71–95. New York: Routledge.

- Verizon 2015. “Web 3.0: Its Promise and Implications for Consumers and Business.” Verizon Business. Accessed February 9, 2019. www.verizonenterprise.com/resources/whitepapers/wp_Web-3-0-promise-and-implications_a4_en_xg.pdf

- Vesnic-Alujevic, L. 2012. “Political Participation and Web 2.0 in Europe: A Case Study of Facebook.” Public Relations Review 38 (3): 466–470. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.01.010

- White, M. 2010. “Clicktivism is Ruining Leftist Activism.” Common Dreams. Accessed February 16, 2019. http://www.commondreams.org/views/2010/08/12/clicktivism-ruining-leftist-activism.

- White, S., and I. Mcallister. 2014. “Did Russia (Nearly) Have a Facebook Revolution in 2011? Social Media’s Challenge to Authoritarianism.” Politics 34 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.12037

- Whiteley, F. P., and P. Seyd. 2002. High-Intensity Participation: The Dynamics of Party Activism in Britain. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

- Wilkin, P., L. Dencik, and É Bognár. 2015. “Digital Activism and Hungarian Media Reform: The Case of Milla.” European Journal of Communication 30 (6): 682–697. doi:10.1177/0267323115595528

- Yamamoto, M., M. Kushin, and F. Dalisay. 2015. “Social Media and Mobiles as Political Mobilization Forces for Young Adults: Examining the Moderating Role of Online Political Expression in Political Participation.” New Media & Society 17 (6): 880–898. doi:10.1177/1461444813518390

- Zhu, A. Y. F., A. L. S. Chan, and K. L. Chou. 2020. “The Pathway Toward Radical Political Participation Among Young People in Hong Kong: A Communication Mediation Approach.” East Asia: An International Quarterly 37 (1): 45–62. doi:10.1007/s12140-019-09326-6

Appendix A

Table A1. Thematic analysis (final themes and codes).