ABSTRACT

This article argues that in the contentious energy market of Central Asia transnational corporations (TNCs) and local governments are the real forces at play. While the European Union (EU) has repeatedly shown interest in the region, scarce profitability of the economic ventures and lack of control over the actual investors have resulted in a loss of interest. Deconstructing the EU energy security strategy towards Central Asia, this article reflects how TNCs formally based in Europe have used the ‘Shield of Nationality’ as protection from the blows of resource-rich governments, while remaining driven by capital accumulation. A case study of the Italian oil and gas company ENI in Kazakhstan highlights how the mediation of home governments between corporations and local administrations depends on its relationship with the TNC. The article suggests that future research of the energy sector should consider the role of TNCs and their ambiguous relationship with their ‘home countries’.

Introduction

Since 1991, the relationship between the European Union (EU) and Central Asia has been characterized by a variety of European actors interacting with strongmen-led governments on a bilateral basis. First came the private sector, which had already been invited to the region during the late Soviet era. New discoveries of oil and gas fields and the thirst for cash in hard currency made business in Central Asia enormously profitable for Europe-based companies, large transnational corporations (TNCs) and smaller companies alike. Royal Dutch Shell, British Petroleum and British Gas, ENI, Total SA, OMV Petrom, and other oil-producing TNCs entered the markets of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in search of hydrocarbons, while European diplomacies and EU institutions played a game of catch up with private interests (Allison and Jonson Citation2001; Azretbergenova and Syzdykova Citation2020; Stegen and Kusznir Citation2015). Since then, government and business interests have aligned over energy security preoccupations. This became especially true for European TNCs which were partly state-owned, as opposed to their US counterparts.

This article analyses the strategies and behavioural inconsistencies between European TNCs, the EU and its member states. What explains the lack of coordination between Europe’s supranational institutions and TNCs? This article argues that different interpretations on how to achieve the goal of energy security among EU institutions, member states and TNCs is the reason behind the inconsistent behaviour of the EU in Central Asia. The constellation of different ‘European actors’ weakens the EU’s bargaining power vis-à-vis local actors and sends the signal to Central Asian partners that the normative agenda can be easily compromised.

Contrasting EU and member states’ strategies towards Central Asia, this article shows how TNCs formally based in Europe have used the ‘shield of nationality’ (Wellhausen Citation2014) as protection from the blows of resource-rich governments in the region while remaining fundamentally driven by policies of capital accumulation. The article analyses the diverging interests of the EU, member states and companies, as well as direct competition between private European energy companies and formal strategies aimed at reducing corruption. The lack of competition among TNCs exploiting oil resources in Central Asia seemingly clashes with the EU’s ideas about fair and open markets. But instead of concentrating on this aspect, EU institutions and European lobby groups have mostly focused on influencing change in the legislation and jurisprudence in Central Asian states to protect investments.

Methodological considerations

Because only marginal volumes of natural gas from Central Asia are exported to Europe, this article concentrates on the oil sector.Footnote1 The business structure of oil is complex because it entails pipelines and railways, hubs and ports, tankers and barrels, making it more of a tradable commodity. Kazakhstan’s oil is sold across the Mediterranean Sea, to Iran, to China and to Lithuania, whereas Uzbek and Turkmen gas is pumped via pipeline to Russia, Iran and China only (Azretbergenova and Syzdykova Citation2020; Pirani Citation2019). The choice to focus on oil inevitably slants the article geographically towards Kazakhstan. As shown in , as of 2020, European investments in the energy sector of Central Asia are limited to Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan.

Table 1. Participation of European Union foreign companies in Kazakhstan’s and Turkmenistan’s oil and gas fields in 2020.

In the oil and gas industry, Central Asian governments mostly deal directly with European (and other Western) TNCs, rather than relying on existing diplomatic networks with the EU or its member states. In fact, such a bilateral arrangement has proved convenient for Central Asian governments and TNCs, while the ‘home countries’ of TNCs only benefit through profit repatriation fees, which can be marginal compared with the cash flow enriching private shareholders and Central Asian elites. In short, despite the hype regarding old and new EU strategic documents towards Central Asia, discussed herein, the principal relationship in the energy sector remains one between national governments and TNCs. The central argument of the paper is that EU institutions, member states and TNCs pursued the objective of energy security in different ways. In this sense, in dialogue with the other contributions to this special issue (Arynov Citation2022; Bossuyt and Davletova Citation2022; Dzhuraev Citation2022; Fawn Citation2022; Pierobon Citation2022), the article proposes to re-analyse the evolution of EU–Central Asian mutual interests in the energy sector to recalibrate the academic debate on the topic.

In the section ‘EU energy strategies towards Central Asia: from energy security to the New Green Deal’ we show how the attitude of the EU has changed over a decade. While initially energy security was interpreted as a diversification of suppliers of oil and gas, by 2019 this strategy was abandoned (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Citation2019). We argue that part of the reason for this change is that the window of opportunity for investments had closed. The market was saturated, and the efforts of Central Asian governments consisted in regaining control of the energy sector (Orazgaliyev Citation2018).

The last section ‘When governments become companies’ lawyers: ENI in Kazakhstan’ is a case study proving that the real actors of the energy market are foreign companies and Central Asian governments because they play according to the same rules, while EU institutions are often sidelined or absent from the picture because they lack interest in business performance. While the objective of TNCs is profit, home governments, particularly when tied to the TNC as in the case of Italy, are reduced to ‘company lawyers’ to prevent private trouble, thus jeopardizing wider EU foreign policy goals, aimed at democracy and human rights promotion. Our analysis of the reactions of Italian governments throughout the years benefits from a series of journalistic investigations as well as our fieldwork in the country.

The fieldwork was conducted among oil workers and industry experts between 2018 and 2020 in Almaty, Nur-Sultan, Aktau and Aksai. While most of the companies have their headquarters in Nur-Sultan, the largest consortia have offices in Atyrau, the so-called ‘country’s oil capital’. Some of the key interviews used for this paper were conducted via voice over internet protocol, due to lockdown restrictions after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This research relies on a systematic review of the literatureFootnote2 exploiting the keywords ‘Europe’ and ‘Central Asia’, and its selection process is discussed in the next section. The final review consisted of 91 studies and helped in grounding our critique towards the common practice of flattening EU, member states and TNC interests into a single energy security strategy.

The choice of analysing the ambiguous relationship of ENI and the Italian government in Kazakhstan has two main reasons. First, shows that there are only three European TNCs in major oil and gas fields in Central Asia: Total SA, Royal Dutch Shell and ENI. As mentioned, British Gas (BG) was another big investor in Kazakhstan. Yet, in Kashagan the company sold its shares to KazMunayGas after being denied selling them to the China National Offshore Oil Corporation and Sinopec (Ostrowski Citation2010; Palazuelos and Fernández Citation2012). Similarly, BG participation in Karachaganak was acquired by Royal Dutch Shell when the company was bought (Shell Global Citation2015). BP became an investor in the field of Tengiz in Kazakhstan in 2000 after merging with American Arco, which since 1997 cooperated with Lukoil in the joint venture LukArco. Still, in 2009, BP sold its shares of LukArco to Lukoil, and in October 2020 withdrew from further exploration of three offshore blocks in the Caspian Sea (Putz Citation2021). Finally, also OMV Petrom, owning the rights of extraction in four small oilfields in Kazakhstan, Komsomolskoe, Aktas, Tasbulat and Turkmenoi, sold its assets, Kom-Munai LLP and Tasbulat Oil Corporation LLP, to Kazakh investors in February 2021 (Sorbello Citation2021).

Second, ENI, along with Chevron, has been the most important company in Kazakhstan for years. The Italian TNC led the Kashagan consortium until 2009. ENI is also co-operator with Shell of the Karachaganak Petroleum Operating B.V. Particularly in these big joint ventures, the participation of other shareholders is marginal, and only operators engage in day-to-day activities bearing the responsibility for the production and financial results.Footnote3 Yet, the case of ENI is peculiar because the Italian government owns shares in the company, while the Netherlands and the UK governments are not shareholders in Shell. Similarly, the Romanian government has shares in OMV Petrom, but the size of investments in Kazakhstan was different (OMV Petrom Citationn.d.). The quarrels between ENI and Kazakhstan jeopardized ENI’s shares in Kashagan after initial conspicuous investments. Losing Kashagan could have meant ENI’s bankruptcy, while OMV Petrom investments in Kazakhstan were only around 4% of the group production. By comparison, in 2019, Kashagan produced 400,000 b/d against the 6450 b/d of Komsomolskoe, Aktas, Tasbulat and Turkmenoi combined (OMV Group Citation2021). This explains why the confrontations between ENI and Kazakhstan often required the intervention of the Italian government. Again, the main argument of the article is that these interventions, led by different interpretations of how to ensure energy security, were dictated by an ambiguous relationship between the state and its TNC, which ended up affecting the credibility of the EU efforts of democracy promotion in the region (Dave Citation2008).

A survey of the literature: energy’s downfall in the institutional agenda

This article is accompanied by a systematic review of the literatureFootnote4 on the relationship between the EU and Central Asia. The search, carried out in April 2021 on Scopus and the Web of Science of the Institute of Scientific Information employing the keywords ‘EU’ and ‘Central Asia’,Footnote5 was narrowed using the following:

The literature should be part of the expanded field of social sciences.

The literature should focus on Central Asia and the EU.

Based on the first requirement, the initial screening revealed 324 studies on Scopus and 189 on the Web of Science. The application of the second principle of exclusion and the removal of doubles narrowed the review down to 91 studies.

Of 91 studies, 33 (or 36.26%) focus explicitly on energy. For the studies pertaining to the energy sector, see Appendix A. The studies are many, but their reading in chronological order by year of publication highlights a progressive fading of the EU conviction to achieve the objective of energy security relying on Central Asian supply of oil and gas.

According to Nanay and Stegen (Citation2012), the scarce engagement of the EU in Central Asia in the 1990s was due to a lack of adequate institutional structures, doubts over the energy potential of the region and a willingness not to worsen the relationship with the Russian Federation (Nanay and Stegen Citation2012, 347–348; Youngs Citation2009). By 2000, the EU internal energy market was sufficiently competitive, hence the European Commission acknowledged the necessity to ensure its energy security in the green papers ‘Towards a European Strategy for the Security of Energy Supply’ (European Commission Citation2000).

The first steps to improve the energy relations beyond the EU borders were taken in 2002 with the ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ of Athens and the formalization of the dialogue with Norway (Prontera Citation2014, 199). That was the same year in which Nabucco, a gas pipeline linking Central Asia with European markets, was first brought to the discussion (Nanay and Stegen Citation2012, 351).

In 2004, the EU promoted the Baku Initiative, which saw the participation of all the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia along with Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and Turkey. The year 2006 was the moment of the entry into force of the Energy Community Treaty that created a common energy market with the Balkan countries (EUR-Lex Citation2006). After the development of such a coherent diplomatic effort targeted at improving the EU energy security, the 2007 Strategy could not but dedicate attention to the energy relations with the Central Asian republics. Nevertheless, according to Delcour (Citation2011), by then the EU was already a latecomer in the region (Delcour Citation2011, 91).

As Prontera (Citation2014) noted, the EU energy policy privileged neither a market approach based on liberalization nor a strategic one based on the promotion of European TNCs and bilateral relations (Andrews-Speed, Liao, and Dannreuther Citation2002). Rather, the EU tried to promote a regional architecture able to enforce the agreements taken on a bilateral basis. This multilateralism may be one of the reasons at the core of its ultimate failure. In fact, the Russian–Ukrainian gas crisis of 2005–06 showed the first cracks of a regional cooperation that could not hold all these countries together. At the Astana conference of 2006 in Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkey participated only as observers. These signals probably pushed EU leaders to think of the Black Sea Synergy (European Commission Citation2010) and the 2007 Central Asia Strategy as possible solutions to bypass the ‘Russian risk’ (Locatelli Citation2010, 961). Indeed, in 2008, 84% of EU imports of natural gas were originating only from three countries: Norway, Russia and Algeria (Locatelli Citation2010, 960).Footnote6

Hence, between 2006 and 2009, the Nabucco project reached the apex of its credibility, producing a series of news updates on sector-specific journals (Oil and Gas Journal Citation2008; Petroleum Economist Citation2006, Citation2007a, Citation2007b, Citation2009; Petroleum Review Citation2009; World of Oil Citation2008).Footnote7 The Nabucco pipeline project became the centre of an EU energy policy that culminated in 2009 with the ‘Third Energy Package’ (Mayer and Peters Citation2017, 138), but already in 2010 Locatelli (Citation2010, 965) noted how this solution was riddled by logistical uncertainties and risks.

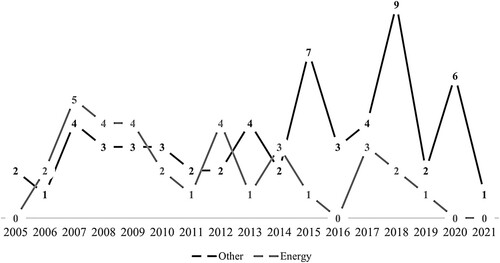

After remaining on paper for more than 10 years, by 2013 interest in academia and policy circles had shifted from Nabucco and towards a less ambitious project: the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). As shown in , while the number of studies on the relations between the EU and Central Asia blossomed after 2014, there was a drastic decrease of research on energy. This trend in the literature corresponds to a waning interest in infrastructural projects that would link Central Asian hydrocarbon basins with consumers in Europe. The expectations did not prove realistic because, with an already relevant array of investors, Central Asian republics could not supply a resource volume that would justify the investment.

Figure 1. Comparison of the trending topic for studies on the European Union and Central Asia over the years. Source: Designed by the authors.

Until 2014, academics and EU policymakers proposed the strengthening of the energy relations between the EU and Central Asia as the only real alternative to differentiate gas imports in an increasingly precarious exchange with Russia (Amineh and Crijns-Graus Citation2014; Kirchner and Berk Citation2010; Locatelli Citation2010; Nanay and Stegen Citation2012; Prontera Citation2014; Ratner et al. Citation2013). While this argument has been repackaged in milder tones by Ibrayeva et al. (Citation2018) and Chumakov (Citation2019) in recent years, the present article concurs with Amineh and Crijns-Graus (Citation2018) in noting that the EU is powerless in Central Asia because its member states maintain the upper hand in foreign policy (Amineh and Crijns-Graus Citation2014, 816; Citation2018, 179; Spaiser Citation2018).

Moreover, as argued in the next section, in the event that Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were fully committed to the task, they would hardly be able to deliver energy supplies sufficient to relieve the EU from its reliance on imports from Russia, which in 2018 amounted to 26.9% of crude oil, 46.7% of solid fuel and 41.1% of natural gas (Eurostat Citation2018).

Initially, EU institutions and European TNCs aimed for the same prize: Central Asian energy resources to ensure energy security. Yet, as the next section highlights, while Central Asia gradually disappeared from the list of EU energy priorities with the failure of the Nabucco project (Amineh and Crijns-Graus Citation2018), European TNCs proved effective in continuing their operations in the region. Still in need of oil supplies and tax revenues, Italy sided with ‘its’ TNC: ENI. This practice often side-stepped the rule of law and led to the de-legitimation of EU institutions, which advocated a process of democratization in the region.

EU energy strategies towards Central Asia: from energy security to the New Green Deal

The EU is required to operate in the field of energy based on the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which in article 194, section b, gives its institutions the authority to act in the market to ensure ‘the security of energy supplies in the Union’ (EUR-Lex Citation2012). Practically, this means that both Parliament and the Commission have active roles in the energy market. Yet, since the composition of Parliament affects the political orientation of the Commission, the 2009, 2014 and 2019 elections have progressively shifted the attention towards the European Green Deal, energy efficiency, and the increasing reliance on renewable energy sources. In other words, José Manuel Barroso’s attempts to negotiate the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCP) are far from Ursula von der Leyen’s efforts to ensure the effective implementation of the European Green Deal (EU Commission Citationn.d. a).

Given the high level of energy consumption compared with the substantial lack of indigenous natural resources, the EU member states have always been net importers of energy. This led EU institutions to strive for a diversification of suppliers and routes to import oil and gas. Already in the late 1990s, the EU was backing the proposal of building what became the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline from Azerbaijan to Turkey,Footnote8 because it would have contributed to source and transit diversification. When it was completed in 2005, the BTC bypassed Russia and thus helped to reduce EU energy dependency on Moscow. Still, pipelines circumventing Russia, such as the BTC, failed to become the main road for Central Asian oil exports to Europe. By 2016, the Russian routes of the Atyrau–Samara pipeline and the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) accounted for the entirety of Kazakhstan’s westward exports.

In 2012, the EU revised its 2007 Strategy towards Central Asia by revamping a project that could have become a crucial part of the Southern Gas Corridor (SCG), which was already on path to connect the gas fields in Azerbaijan with European consumers (Council of the European Union Citation2007; European Commission Citation2007). The TCP was the subject of an intergovernmental agreement between Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and the EU. Linking Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan would have ensured a reliable supply of gas to Europe and the possibility to scale up the SCG in the future. As these conversations were being laid on the table, Russia had successfully completed the construction of the Nord Stream pipeline, bypassing the Baltic countries and Ukraine, in November 2011. In addition, Russia’s Gazprom was in the process of garnering the consent of several transit countries to build the ambitious South Stream pipeline across the Black Sea. Although South Stream was shelved after Russia’s clashes with Ukraine in 2014, Moscow remained the prominent supplier of gas to Europe, with around 243 bcm exported in 2018, twice as much as Norway, the second largest supplier (Dediu, Czajkowski, and Janiszewska-Kiewra Citation2019).

The efforts by the European Commission to resume the conversation on the TCP became part of a geopolitical debate on the role of Russia in the former Soviet space (Cutler Citation2018). At the time, Turkmenistan was selling its gas via land pipeline to Russia and China. But its gas was comparatively cheap: Russia bought it at the rather low price of US$110/mcm, while its European customers were paying up to US$500/mcm; China took Turkmen gas as a payback for its investments on the development of the fields (Henderson and Mitrova Citation2015). Therefore, the prospect of supplying gas to European customers via a more direct route was seen as convenient for Turkmenistan. At the same time, a successful agreement with the EU would have been a diplomatic coup for Turkmenistan, a country with an abysmal record on human, civil and political rights. For EU institutions, TCP negotiations became a bargaining tool against Russia, one mobilized as a direct consequence of its aggression against Ukraine. Russia was also one of the main obstacles to the construction of an undersea pipeline across the Caspian, given the unresolved legal status of the sea. As negotiations over Ukraine improved, however, the conversation about the TCP fell off the table, another demonstration that the negotiations were contingent on other, more important, diplomatic variables.

As suggested by the literature review, by 2014 the strategy of suppliers’ diversification had failed, but the EU energy dependency worsened. The latest data from 2018 show that several countries in the EU-27 have increased their energy dependency rate since 2000. Overall, in 2018, the EU imported 58% of the energy it consumed. Two-thirds of the imports were constituted by crude oil, followed by 24% of gas and 8% of solid fossil fuels. The only Central Asian country in the list of the most relevant EU energy suppliers is Kazakhstan with 7.2%, well behind Russia (29.8%), but in line with Iraq (8.7%), Saudi Arabia (7.4%) and Norway (7.2%) (Eurostat Citation2018). Before oil prices and production volumes were driven down by the Russo-Saudi trade spat and the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2019 the biggest oil fields of Kazakhstan had an output of 650,000 b/d from Tengiz, 400,000 b/d from Kashagan and 234,000 b/d from Karachaganak. At the same time, in March 2020 the CPC hit a record high of 1.65 million b/d of oil transported (Coleman Citation2019, Citation2020). Kazakhstan’s annual oil production, at around 90 million tonnes, if entirely sold to EU countries, would only satisfy around 17% of the EU’s total consumption.

The Commission’s understanding of the meaning of ensuring ‘the security of energy supplies in the Union’ (EUR-Lex Citation2012) changed accordingly. While originally it was interpreted as finding alternative reliable suppliers of oil, gas and fossil fuels, it then involved the diversification of energy sources by developing renewable alternatives. This is well exemplified by the 2019 EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, which unsurprisingly dropped the emphasis on energy security and enhanced the narrative on human rights and connectivity (Russell Citation2019). Human Rights Watch, a non-governmental organization (NGO) devoted to the protection of human rights globally, claimed that the first, 2007, strategy had not done enough in the realm of human rights: ‘In 2019, the EU adopted a new strategy on the region, with marked improvements on the previous one from 2007, which was weak on human rights’ (Williamson Citation2019).

As of 2021, the Commission and Parliament are decisively oriented towards the reduction of carbon emissions, expressed through investments in renewables and energy efficiency.Footnote9 This reinterpretation of their role is projected towards a greener future, but as proved by the increase in gas prices of the autumn of 2021, it does not resolve the immediate dependency on Russian supplies of many of its member states (Temnycky Citation2021). The following section showcases a case study of Italy’s ENI in Kazakhstan, which serves to exemplify the argument of a disconnect between different interpretations on how the goal of energy security is to achieve and at what cost.

When governments become companies’ lawyers: ENI in Kazakhstan

‘The Italians built this, the Americans brought that, the French introduced us to it.’ These are commonly heard sentences while interviewing experts, both local and foreign, on the energy sectors across Central Asia. The country toponym, however, has seldom anything to do with the corresponding government and is often tied to private investment by either large TNCs or entrepreneurial groups.

When researching the ‘Italian factor’ in Kazakhstan, the observer would gather that ENI is no different from Kazakhstan’s NOC KazMunayGas, an arm of the government used to satisfy the political objectives of the Italian government. The reality, though, is more complex. ENI was in fact a public company until 1992, when Prime Minister Giuliano Amato sanctioned its transformation into a private enterprise to diminish the influence of the political parties in the wake of the Tangentopoli corruption scandal (The Conversation Citation2016). At that time, ENI was considered by Italian parties as a cash cow to milk, and it did not resemble the lucrative enterprise of today (D’Amato Citation2005).

While the privatization was completed only in 1995, the Italian government still owns 30.33% of ENI’s shares, directly through the Ministry of Economy and Finance and indirectly through the government-owned investment bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (ENI.com Citationn.d.). This partly justifies the proactivity of the Italian cabinet in Kazakhstan throughout the years. Nevertheless, the scarce profitability of certain investments could suggest that Italian intervention has been often dictated by a non-remunerative relationship with ENI. On the other hand, while ENI’s behaviour in Kazakhstan wavered between its public and private souls throughout the year, its only objective has been the maximization of profits.

Under Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi (2001–06 and 2008–11), personal and political interests mixed heavily with the management of ENI. This allowed Italy to remain a major buyer of Libyan and Russian oil and gas, in light of Berlusconi’s questionable ties with Muhammar Gaddafi and Vladimir Putin. Berlusconi was instrumental in the election of Paolo Scaroni, earlier a successful entrepreneur in London, as ENI’s chief executive officer (CEO) in 2005 (Greco and Oddo Citation2018, 168). Scaroni and his successor, Claudio Descalzi, have been acquitted on charges of corruption in Nigeria, in a trial concluded in March 2021 in Milan (Dominelli Citation2021). Still, Berlusconi’s role in Kazakhstan was marginal, and limited to the colourful tales of his visit to Nazarbayev’s dacha, followed by congratulations on Kazakh men’s manliness (Ferrucci Citation2013).

The real puzzle started in 2006 when ENI faced government fines in Kazakhstan for the delays at the Kashagan oilfield, having declared that the deadline for the first extraction foreseen for 2010 would not have been respected (Collier and Venables Citation2012, 162; Tekin and Williams Citation2011, 132). At the time Romano Prodi was Italy’s prime minister. It became clear that Kazakhstan’s government was using sanctions to obtain compensation from the Kashagan consortium, Agip-KCO (Sarsenbayev Citation2011). In addition, ENI was stripped of its single operatorship at Kashagan in favour of a dual operatorship with Shell, embodied by the new consortium: the North Caspian Operating Company (NCOC).

ENI’s punishment was partially borne by the Italian bank UniCredit, which overpaid the acquisition of Kazakhstan’s ATF Bank, property of Bulat Utemuratov, a close ally of Nazarbayev’s. The acquisition followed a 2007 visit of Prodi to Kazakhstan along with a number of Italian entrepreneurs, including ENI’s Paolo Scaroni and then-CEO of UniCredit Alessandro Profumo (Marozzi Citation2007). ATF was purchased for US$2.275 billion (Financial Times Citation2013), while industry sources put the value of ATF at no more than US$850 million (Mondani Citation2013). After the acquisition further government sanctions against ENI were dropped, essentially unveiling the purchase as a concealed bribe destined for Nazarbayev and his associates. ATF was later sold for US$464 million to Galimzhan Yessenov, son-in-law of Almaty mayor Akhmetzhan Yessimov, while UniCredit guaranteed US$630 million of ATF’s debt for the next two years, de facto further discounting the acquisition (Gordeyeva Citation2013). The deal was a disaster for UniCredit, but advantageous for some: Utemuratov became Kazakhstan’s first billionaire (Forbes.kz Citationn.d.), Profumo entered the board of ENI, and Prodi started receiving an annual retainer worth millions as a member of Nazarbayev’s international board of advisors (Mayr Citation2013).

In 2013, Italy’s Prime Minister Enrico Letta maintained the government’s habit to act as ‘informal lawyers’ of Italian companies rather than defending and promoting sovereign interests abroad. When the wife and daughter of a prominent opponent of Nazarbayev were abducted in Rome and flown into Kazakhstan with the help of Italy’s secret service, the Italian Ministry of Interior behaved contradictorily concerning the scandal. When questioned by Parliament, minister Angelino Alfano claimed ignorance regarding the events – an explanation difficult to believe, given that Alfano sat at the top of the chain of command that would have authorized the extraordinary rendition (Sorbello Citation2019, 211). The action was the subject of further questioning at the EU Parliament (Kiil-Nielsen, Lochbihler, and Keller Citation2013).

ENI was touted as involved in the case, because Jorg Mayerbrock, a former employee of the Italian oil and gas company, was hired as the pilot of the private jet rented to fly to Kazakhstan (Greco and Oddo Citation2018). A journalistic investigation unveiled the connection between the Italian government’s response and ENI, and suggested that the search for Mukhtar Ablyazov and his relatives was commissioned by the Kazakh government to the Italian company (Mondani Citation2013).

Since obtaining shares in all major consortia of the country, the Kazakh government has notably reduced its hostile engagement with energy companies. Similarly, ENI’s loss of the single operatorship in Kashagan side-lined the Italian company and reduced its interactions with Kazakh authorities. ENI had acted as a classic energy corporation, overcoming competition by undersigning disputable conditions imposed by local governments (Cooley and Sharman Citation2015; Maugeri Citation2006). In Kazakhstan, this was hardly unique. In fact, Mobil Oil, Philips Petroleum, Texaco and Amoco were all tried in the United States following the ‘Kazakhgate’ scandal which targeted the middleman James Giffen for violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. While Bryan Williams was jailed, Giffen was sentenced with a fine on the ground that his involvement benefited his country’s economy (Yeager Citation2012, 456). Chinese corporations were never prosecuted, but their corrupt involvement with the local elite has been hinted at by Mukhtar Ablyazov (Cooley Citation2012, 141).

In 2012, Italy was importing 17% of Kazakhstan’s total exports, making it the country’s largest customer. Despite China’s rise as an importer of Kazakh oil, Italy still maintained first place. Yet, for Italy, Kazakhstan only constituted 4.2% of its total oil imports (Koch Citation2013, 115). In 2018, Kazakhstan ranked eighth in the list of oil suppliers to Italy, behind Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Nigeria (Statista Citation2021). These quantities did not justify the involvement of the Italian government to secure energy supplies, but any of the blows assessed by the Kazakh government could have jeopardized ENI’s financial stability, status and international reputation, creating a double loss for ‘its’ home government: financial and energetic. In other words, Italy’s energy security was at risk.

ENI’s unclear business transactions did not limit to Central Asia: they extended to Africa, from Libya to Egypt (Greco and Oddo Citation2018). Fieldwork sources referred to having assisted in a discussion involving the payment of a bribe of 7% on top of the value of a contract for the improvement of conditions of Block 3 in Angola in the 1990s. Clearly, the bribe was not paid in person, but rather deposited in a bank account at the Cayman Islands in the name of former President José Eduardo dos Santos.Footnote10 As sources reported, a 7% bribe on top of contracts was an informal rule in Africa in the 1990s. Arguably, ENI became a financial powerhouse because of similar corrupt business dealings in Africa and Central Asia.

These problematic deals were never addressed by EU institutions. The official report of the meetings between ENI and EU institutions indicates a regular schedule of appointments between the company and the Commission, but none of the meetings since 2014 ever focused on ENI’s engagement in Central Asia. Only six out of the 46 meetings involved a discussion on ENI’s engagement in Africa, but the Commission proved especially interested in the company’s role in supplying energy for the internal energy market of the EU (EU Commission Citationn.d. b). Similarly, Royal Dutch Shell had 83 meetings with the Commission, two of them on Africa, one on Iran and one on the Nord Stream, but Central Asia was never discussed (EU Commission Citationn.d. e). OMV had 15 meetings since 2015, and Total only three, but none on Central Asia (EU Commission Citationn.d. c, Citationn.d. d).

In fact, unlike the United States, which approved the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act after the Watergate scandal, the EU does not dispose of tools to counteract the bribery of its companies abroad. Italy is part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention, the Group of States Against Corruption of the Council of Europe, and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, but the EU did not uphold its anticorruption standards to European energy companies (Pleines and Wöstheinrich Citation2016).

Conclusions

The article has interpreted the lack of coordination between EU institutions and TNCs as different understandings on how to achieve the objective of energy security. Throughout the discussion we showed how over time the EU lost interest in Central Asian energy resources, while European TNCs consistent search for profit jeopardized its general Strategy in the region. Similarly, European national governments expected companies to cooperate in satisfying their internal energy demands, but they often had to intervene directly to guarantee the desired result. This was exemplified in the case study of ENI in Kazakhstan, which showed a rather tight collaboration between the company and the highest ranks of the Italian government despite scarce or negative returns for the Italian economy (Statista Citation2020, Citation2021).

Similarly, the initial European strategy to achieve energy security in cooperation with the governments of Central Asia was not entirely pertinent to the reality of private interests engaged in energy production and trade in the region. In fact, the trans-Caspian projects to extend the BTC oil pipeline and the Southern Gas Corridor that the EU backed were found to be unsustainable with respect to economic returns and the availability of resources. China proved to be a faster and more convincing partner, often overpaying for projects to secure gas and oil supplies to satisfy its growing internal energy demand. At the same time, the EU progressively changed its strategy on how to achieve energy security, excluding the topic from its documents regarding Central Asia, whereas Central Asian leaders leaned towards the Chinese and Russian model by which importers pay without attaching conditions (Rettman Citation2011).

This deconstruction of the academic debate on the Central Asian energy sector appears necessary in light of the growing simplifications adopted to justify narrow interpretations of states or international organizations as monolithic blocs. The analysis indicates that the EU’s objectives in terms of energy cooperation were not followed by concrete actions in the same direction. The case study of ENI in Kazakhstan has shown how Central Asian governments have often acted seeking compensation or attempting to increase their shares in different project consortia causing the defensive reactions of TNCs, which were then aided by their national governments. These interactions were often in open contrast with the EU strategies, which aimed at strengthening human rights and the rule of law in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The exact figure is not clear because Central Asian countries do not result as major suppliers of natural gas to Europe (Eurostat Citation2018). Still, it is a relatively known fact that most of the gas bought by Russia in Central Asia is later resold to European countries (Henderson, Pirani, and Yafimava Citation2012).

2 A systematic literature review is a technique that allows an unbiased literature review to be undertaken, including all works found through predetermined parameters.

3 Financial department employee, interview by the authors, 14 April 2020.

4 No language limitation has been applied. As seen in Table A1 in Appendix A, there are works in Russian, French, German and Italian.

5 A search of ‘EU’, ‘Central Asia’ and ‘energy security’ would have further limited the search to 45 studies on Scopus and 31 on Web of Science.

6 The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine that started in February 2022 has now upended the once strong relationship between the EU and Russia in terms of energy trade. The war could lead to a revision of the EU's energy strategy and, consequently, of its relationships with other countries and regions. The analysis provided herein is current as of December 2021.

7 While non-academic, these sector-specific journals are Scopus indexed. The full references are in the respective sections.

8 With a capacity of 1 million b/d, or around 400 mty.

9 Employee at DG ENER, European Commission, interview by the authors, 4 November 2021.

10 Financial department employee, interview by the authors, 6 April 2020.

References

- Allison, R., and L. Jonson, eds. 2001. Central Asian Security. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Amineh, M. P., and W. H. J. Crijns-Graus. 2014. “Rethinking EU Energy Security Considering Past Trends and Future Prospects.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 13 (5–6): 757–825. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341326.

- Amineh, M. P., and W. H. J. Crijns-Graus. 2018. “The EU-Energy Security and Geopolitical Economy: The Persian Gulf, the Caspian Region and China.” African and Asian Studies 17 (1–2): 145–187. doi:10.1163/15692108-12341404.

- Andrews-Speed, P., X. Liao, and R. Dannreuther. 2002. “The Strategic Impact of China’s Energy Needs.” In International Institute for Strategic Studies, edited by Philip Andrews, 71–97. London: Adelphi Paper.

- Arynov, Z. 2022. “Opportunity and Threat Perceptions of the EU in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 734–751. doi:10.1080/02634937.2021.1917516.

- Azretbergenova, G., and A. Syzdykova. 2020. “The Dependence of the Kazakhstan Economy on the Oil Sector and the Importance of Export Diversification.” International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 10 (6): 157–163.

- Bossuyt, F., and N. Davletova. 2022. “Communal Self-Governance as an Alternative to Neo-Liberal Governance: Proposing a Post-Development Approach to EU Resilience-Building in Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 788–807. doi:10.1080/02634937.2022.2058913.

- Chumakov, D. M. 2019. “Prospects of Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline.” World Economy and International Relations 63 (8): 47–54. doi:10.20542/0131-2227-2019-63-8-47-54.

- Coleman, N. 2019. “Kazakhstan’s Kashagan Oil Output Surges to 422,000 b/d in Q3.” S&P Global, November 14. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/111419-kazakhstans-kashagan-output-hits-400000-b-d-in-early-sep-eni.

- Coleman, N. 2020. “Kazakhstan’s Tengiz Crude Field Producing ‘To Plan’ Despite OPEC+ Agreement.” S&P Global, May 4. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/050420-kazakhstans-tengiz-crude-field-producing-to-plan-despite-opec-agreement.

- Collier, P., and A. J. Venables. 2012. “Plundered Nations?: Successes and Failures in Natural Resource Extraction.” In Choice Reviews Online, edited by P. Collier and A. J. Venables. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.5860/choice.49-3978.

- Cooley, A. 2012. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press (OUP). doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929825.001.0001.

- Cooley, A., and J. C. Sharman. 2015. “Blurring the Line Between Licit and Illicit: Transnational Corruption Networks in Central Asia and Beyond.” Central Asian Survey 34 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1080/02634937.2015.1010799.

- Council of the European Union. 2007. “The EU and Central Asia: Strategy for a New Partnership, Document 10113/07, Brussels, 31 May Endorsed by the EU Council Presidency Conclusions of the Brussels European Council.” June 21–22. http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%2010113%202007%20INIT.

- Cutler, R. M. 2018. “Evolution of the East Central Eurasian Hydrocarbon Energy Complex: The Case of China, Russia, and Kazakhstan.” African and Asian Studies 17 (1–2): 40–62. doi:10.1163/15692108-12341400.

- D’Amato, A. 2005. “Eni ed Enel, poison pills e tubatico.” [Eni and Enel, poison pills and tubes]. La Terza Repubblica, October 7. http://www.terzarepubblica.it/archivio/eni-ed-enel-poison-pills-e-tubatico/.

- Dave, B. 2008. “The EU and Kazakhstan: Is the Pursuit of Energy and Security Cooperation Compatible With the Promotion of Human Rights and Democratic Reforms?” In Engaging Central Asia: The European Union’s New Strategy in the Heart of Eurasia, edited by N. J. Melvin, 43–67. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Dediu, D., M. Czajkowski, and E. Janiszewska-Kiewra. 2019. “How Did the European Natural Gas Market Evolve in 2018?”. McKinsey and Company. April 15. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/petroleum-blog/how-did-the-european-natural-gas-market-evolve-in-2018#.

- Delcour, L. 2011. “Shaping the Post-Soviet Space? EU Policies and Approaches to Region-Building.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02234_11.x.

- Dominelli, C. 2021. “Processo Eni-Nigeria, Descalzi e Scaroni assolti dall’accusa di corruzione internazionale: «Il fatto non sussiste».” [Trial Eni-Nigeria, Descalzi and Scaroni Acquitted from the Accuse of International Corruption: “Due to Lack of Evidence]. Il Sole 24 Ore, March 17. https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/processo-eni-nigeria-descalzi-e-scaroni-assolti-dall-accusa-corruzione-internazionale-il-fatto-non-sussiste-ADO1bvQB?refresh_ce=1.

- Dzhuraev, S. 2022. “The EU's Central Asia policy: no chance for change?” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 639–653. doi:10.1080/02634937.2022.2054951.

- ENI.com. n.d. “ENI’s Share Capital Structure.” Accessed 11 October 2020. https://www.eni.com/en-IT/about-us/governance/shareholders.html.

- EUR-Lex. 2006. “The Energy Community Treaty.” May 29. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Al27074.

- EUR-Lex. 2012. “Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.” October 26. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT.

- European Commission. 2000. Towards a European Strategy for the Security of Energy Supply. Brussels. November 29. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0ef8d03f-7c54-41b6-ab89-6b93e61fd37c/language-en.

- European Commission. 2007. “European Community Regional Strategy Paper for Assistance to Central Asia for the Period 2007–2013.” http://www.eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/central_asia/rsp/07_13_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2010. “Black Sea Synergy.” March 15. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_10_78.

- European Commission. n.d. a. “A European Green Deal.” https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

- European Commission. n.d. b. “Transparency Register: ENI.” https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/consultation/displaylobbyist.do?id=99578067285-35.

- European Commission. n.d. c. “Transparency Register: OMV.” https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/consultation/displaylobbyist.do?id=94274031992-65.

- European Commission. n.d. d. “Transparency Register: Total Direct Energie.” https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/consultation/displaylobbyist.do?id=625822526139-43.

- European Commission. n.d. e. “Transparency Register: Royal Dutch Shell.” https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/consultation/displaylobbyist.do?id=05032108616-26.

- Eurostat. 2018. “From Where Do We Import Energy and How Dependent are We?” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/energy/bloc-2c.html.

- Fawn, R. 2022. “‘Not Here for Geopolitical Interests or Games’: The EU’s 2019 Strategy and the Regional and Inter-Regional Competition for Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 675–698. doi:10.1080/02634937.2021.1951662.

- Ferrucci, A. 2013. “Quando il dittatore kazako disse a B.: “Vieni nella mia dacia, portati il pigiama.” [When the Kazakh Dictator Told B.: ‘Come to My Dacha, Bring a Pijama]. Il Fatto Quotidiano, July 18. https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2013/07/18/quando-dittatore-kazako-disse-a-berlusconi-vieni-nella-mia-dacia-portati-pigiama/659664/.

- Financial Times. 2013. “UniCredit Buying ATF for $2.3 bln.” Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/30578378-201f-11dc-9eb1-000b5df10621.

- Forbes.kz. n.d. “Bulat Utemuratov.” Accessed 11 October 2020. https://forbes.kz/ranking/object/41.

- Gordeyeva, M. 2013. “UniCredit May Sell ATF Bank to Kazakh Firm for $500 Million.” Reuters, January 31. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-unicredit-kazakhstan/unicredit-may-sell-atf-bank-to-kazakh-firm-for-500-million-idUSBRE90U0O220130131.

- Greco, A., and G. Oddo. 2018. Lo Stato Parallelo: La Prima Inchiesta Sull’ENI Tra Politica, Servizi Segreti, Scandali Finanziari e Nuove Guerre [The Parallel State: The First Investigation on ENI Among Politics, Secret Services, Financial Scandals and New Wars]. Milano: Chiarelettere.

- Henderson, J., and T. Mitrova. 2015. “The Political and Commercial Dynamics of Russia’s Gas Export Strategy.” 102. OIES Paper.

- Henderson, J., S. Pirani, and K. Yafimava. 2012. “CIS Gas Pricing: Towards European Netback?” In The Pricing of Internationally Traded Gas, edited by J. Stern, 1–82. Oxford: OUP/OIES.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security. 2019. “Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership.” May 15. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_the_eu_and_central_asia_-_new_opportunities_for_a_stronger_partnership.pdf.

- Ibrayeva, A., D. V. Sannikov, M. A. Kadyrov, V. N. Zapevalov, E. L. Hasanov, and V. N. Zuev. 2018. “Importance of the Caspian Countries for the European Union Energy Security.” International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 8 (3): 150–159.

- Kiil-Nielsen, N., B. Lochbihler, and F. Keller. 2013. “Question for Written Answer E-007409-13.” EU Parliament, June 24. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-7-2013-007409_EN.html.

- Kirchner, E., and C. Berk. 2010. “European Energy Security Co-operation: Between Amity and Enmity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 48 (4): 859–880. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02077.x.

- Koch, N. 2013. “Kazakhstan’s Changing Geopolitics: The Resource Economy and Popular Attitudes About China’s Growing Regional Influence.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 54 (1): 110–133. doi:10.1080/15387216.2013.778542.

- Locatelli, C. 2010. “Russian and Caspian Hydrocarbons: Energy Supply Stakes for the European Union.” Europe–Asia Studies 62 (6): 959–971. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20750259.

- Marozzi, M. 2007. “Prodi in Kazakistan, e c’è Rovati.” [Prodi in Kazakhstan, and there’s Rovati]. La Repubblica, https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2007/10/08/prodi-in-kazakistan-rovati.html.

- Maugeri, L. 2006. The Age of Oil: The Mythology, History, and Future of the World’s Most Controversial Resource. 1st ed. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

- Mayr, W. V. 2013. “What Human Rights Problems? European Politicians Shill for Kazakh Autocrat.” Spiegel International, March 13. https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/european-social-democrats-lobby-for-kazakhstan-autocrat-a-888428.html.

- Mayer, M., and S. Peters. 2017. “Shift of the EU Energy Policy and China's Strategic Opportunity.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 3 (1): 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740017500051

- Mondani, P. 2013. “L’ostaggio.” [The Hostage]. Report, November 25, 2013, https://www.raiplay.it/video/2013/11/Report-del-25112013-3b2061ff-643d-4599-a1c6-65f6d01f8496.html.

- Nanay, J., and K. S. Stegen. 2012. “Russia and the Caspian Region: Challenges for Transatlantic Energy Security?” Journal of Transatlantic Studies 10 (4): 343–357. doi:10.1080/14794012.2012.734670.

- Oil and Gas Journal. 2008. “Transportation – Quick Takes: Nabucco Capacity Attracts Strong Shipper Interest.” Oil and Gas Journal 106 (3): 10.

- OMV Group. 2021. “OMV Petrom Divests Production Assets in Kazakhstan.” https://www.omv.com/en/news/omv-petrom-divests-production-assets-in-kazakhstan.

- OMV Petrom. n.d. “Shareholder Structure.” https://www.omvpetrom.com/en/investors/share-and-gdr/shareholder-structure.

- Orazgaliyev, S. 2018. “Reconstructing MNE–Host Country Bargaining Model in the International Oil Industry.” Transnational Corporations Review 10 (1): 30–42. doi:10.1080/19186444.2018.1436646.

- Ostrowski, W. 2010. Politics and Oil in Kazakhstan. 1st ed. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203869161.

- Palazuelos, E., and R. Fernández. 2012. “Kazakhstan: Oil Endowment and Oil Empowerment.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 45 (1–2): 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2012.02.004.

- Petroleum Economist. 2006. “Nabucco Loses Its Plot.” Petroleum Economist 73 (11): 20.

- Petroleum Economist. 2007a. “Hungary Leaves Nabucco on Its Deathbed: Hungary Demands Fed by Russian Fuels.” Petroleum Economist 74 (4): 5.

- Petroleum Economist. 2007b. “I’m Not Dead, Croaks Nabucco.” Petroleum Economist 74 (6): 2.

- Petroleum Economist. 2009. “Natural Gas: Nabucco Takes a Step Forwards.” Petroleum Economist 76 (8): 26.

- Petroleum Review. 2009. “Gas: New Nabucco Challenges.” Petroleum Review 63 (74). https://knowledge.energyinst.org/search/record?id=73294

- Pierobon, C. 2022. “European Union, Civil Society and Local Ownership in Kyrgyzstan: Analysing Patterns of Adaptation, Reinterpretation and Contestation in the Prevention of Violent Extremism (PVE).” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 752–769. doi:10.1080/02634937.2021.1905608.

- Pirani, Simon. 2019. “Central Asian Gas: Prospects for the 2020s.” https://doi.org/10.26889/9781784671525.

- Pleines, H., and R. Wöstheinrich. 2016. “The International–Domestic Nexus in Anti-corruption Policy Making: The Case of Caspian Oil and Gas States.” Europe–Asia Studies 68 (2): 291–311. doi:10.1080/09668136.2015.1126232.

- Prontera, A. 2014. “La Dimensione Istituzionale Della Sicurezza Energetica Europea: Prospettive e Limiti Dell’External Energy Governance.” [The Institutional Dimension of European Energy Security: Perspectives and Limits of the External Energy Governance]. Stato e Mercato 101: 195–224. doi:10.1425/77411.

- Putz, C. 2021. “BP Declined to Dive Back into Kazakh Oil Fields”. The Diplomat. March 15. https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/bp-declined-to-dive-back-into-kazakh-oil-fields/.

- Ratner, M., P. Belkin, J. Nichol, and S. Woehrel. 2013. “Europe’s Energy Security: Options and Challenges to Natural Gas Supply Diversification.”

- Rettman, A. 2011. “Turkmenistan: We’re Not Sure Why Barroso is Coming.” EU Observer, January 10. https://euobserver.com/foreign/31616.

- Russell, M. 2019. “The EU’s New Central Asia Strategy.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/633162/EPRS_BRI(2019)633162_EN.pdf.

- Sarsenbayev, K. 2011. “Kazakhstan Petroleum Industry 2008–2010: Trends of Resource Nationalism Policy?” The Journal of World Energy Law & Business 4 (4): 369–379. doi:10.1093/jwelb/jwr017.

- Shell Global. 2015. “Combining Shell and BG: A Simpler and More Profitable Company.” https://www.shell.com/about-us/what-we-do/combining-shell-and-bg-a-simpler-and-more-profitable-company.html.

- Sorbello, P. 2019. “Italian Business in Central Asia: In and Around the Energy Sector.” Eurasiatica 13: 205–218.

- Sorbello, P. 2021. “Oil Company OMV Petrom Leaves Kazakhstan.” The Diplomat. February 18. https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/oil-company-omv-petrom-leaves-kazakhstan/.

- Spaiser, O. A. 2018. The European Union’s Influence in Central Asia. Geopolitical Challenges and Responses. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Statista. 2020. “Gross Imports of Natural Gas in Italy in 2019, by Country of Origin.” Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/787720/natural-gas-imports-by-country-of-origin-in-italy/.

- Statista. 2021. “Volume of Crude Oil Imported to Italy During the 1st Quarter of 2020, by Country of Origin.” Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/789168/volume-of-crude-oil-imported-by-country-of-origin-in-italy/.

- Stegen, K. S., and J. Kusznir. 2015. “Outcomes and Strategies in the ‘New Great Game’: China and the Caspian States Emerge as Winners.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 6 (2): 91–106.

- Tekin, A., and P. A. Williams. 2011. “Geo-Politics of the Euro-Asia Energy Nexus: The European Union, Russia, and Turkey.” In Choice Reviews Online, edited by A. Tekin and P. A. Williams. Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.5860/choice.49-0532.

- Temnycky, M. 2021. “Europe Must Reduce Its Dependence on Russian Gas.” Euronews, November 1. https://www.euronews.com/2021/11/01/europe-must-reduce-its-dependence-on-russian-gas-view.

- The Conversation. 2016. “Looking Back at 1992: Italy’s Horrible Year.” The Conversation, October 8. https://theconversation.com/looking-back-at-1992-italys-horrible-year-66739.

- Wellhausen, R. L. 2014. The Shield of Nationality. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316014547.

- Yeager, M. G. 2012. “The CIA Made Me Do It: Understanding the Political Economy of Corruption in Kazakhstan.” Crime, Law and Social Change 57 (4): 441–457. doi:10.1007/s10611-011-9341-2.

- Williamson, H. 2019. “EU Should Live Up to Its Rhetoric on Central Asia.” Human Rights Watch, December 17. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/17/eu-should-live-its-rhetoric-central-asia#].

- World of Oil. 2008. “Sixth Nabucco Pipeline Partner Named.” World of Oil 229 (3): 15.

- Youngs, R. 2009. Energy Security: Europe’s Foreign Policy Challenge. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Appendix A

Table A1. Systematic review of the literature on the EU and Central Asia revolving on energy.