?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article is the first attempt to apply Putnis and Sauka's approach to direct measurement of the shadow economy through a survey of company managers in Central Asia. The results of the survey are used to calculate a shadow economy index for 2017 and 2018 in Kyrgyzstan, and to discuss the difference between direct and indirect methods in calculating the size of a shadow economy. We also propose a distinction between shadow economies and informality in general. While a shadow economy is usually understood to arise as a consequence of underreporting of income, we argue that informality is best understood as the aggregate of non-monetary and non-economic practices used in society. Applying this distinction to our case, we suggest that the origins of Kyrgyzstan's shadow economy are not only economic; rather social and cultural processes have had significant effects. This has implications for policy responses that address shadow economic activities.

Familiar but unknown: (re)introducing informality

A recent International Labour Organization (ILO) report (Kuhn, Milasi, and Yoon Citation2018) estimates that 2 billion workers are active in the informal economy. Figures are higher if the secondary effects of informal employment (Dodman, Archer, and Satterthwaite Citation2019; Satterthwaite et al. Citation2020) and the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are taken into account.Footnote1 Job insecurity goes hand in hand with activity in the informal economy, with growing numbers working in precarious employment arrangements. High levels of employment in the informal economy also impact state tax revenues (reducing income and other employment-related taxes). In these circumstances, government spending capacity is substantially affected, with consequences for resourcing of support to citizens. High rates of informal employment can also discourage investment and reduce the availability of credit in whole sectors or countries, resulting in lower and less predictable levels of foreign direct investment (FDI). Accordingly, national governments and international organizations (ILO, the World Bank and, more recently, the European Commission) have, with growing persistence, proposed measures to curb the informal sector (Eurostat Citation2019; World Bank Citation2019) and to tackle issues such as informal labour, tax fraud, informal practices and payments (Labour Market Observatory Citation2018; Williams and Bezeredi Citation2018; Williams and Lapeyre Citation2017).

Due to persistent informality in several spheres of public life, a number of scholars have tended to regard post-Soviet Central Asian countries as kleptocracies, with a restricted elite capitalizing on returns from the extraction of natural resources and/or from gatekeeping of foreign aid and investment (Ahmed Citation2013; Cooley and Heathershaw Citation2017; Cooley and Sharman Citation2015; Furstenberg Citation2018). However, in spite of a growing body of literature, there is still little agreement on what are the key obstacles to development in Central Asia and how best to enhance governance standards there. It has been argued elsewhere that societal attitudes need to be taken into account when choosing measures to best tackle informality at the country and regional levels (Ledeneva Citation2013; Polese, Morris, and Kovács Citation2016a). However, these insights have not yet been integrated into informality studies in Central Asia, in spite of their potential to open new avenues of research and increase understanding of why people and economic actors more broadly, would decide to comply, or not, with state instructions and international standards.

This paper is an attempt to fill this gap. Drawing from a manager’s survey that our team conducted in Kyrgyzstan for 2017 and 2018, this paper makes three significant contributions. Empirically, this is possibly the first attempt to measure the shadow economy of Kyrgyzstan (or any other Central Asian country) using a direct measurement method, drawing from a survey method previously applied to other post-Soviet (but not Central Asian) states, including the Baltic States, Georgia, Russia and Ukraine.Footnote2 Kyrgyzstan performs poorly when it comes to any indicator of either civil and socio-political freedom or government effectiveness. It is the 80th country for ease of doing business;Footnote3 international rankings qualify the country as not free;Footnote4 and its government score is deemed as substantially ineffective.Footnote5 Its shadow economy was estimated in 2015 (the last estimate available using the Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes (MIMIC) method) to amount to 30.78% of gross domestic product (GDP);Footnote6 and the business climate is perceived as extremely corrupt.Footnote7 Despite these apparent challenges, however, Kyrgyzstan has been chosen as a base for international organizations because of its relatively liberal environment (when compared with its immediate Central Asian neighbours, which include Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), making it a viable location for a first pilot of Putniņš and Sauka’s (Citation2015) shadow economy manager survey in Central Asia. Roll out of the survey in Kyrgyzstan was possible thanks to the presence of SIAR Research and Consulting, a highly reliable partner operating in the country and with whom we have been working for almost a decade.

Our results (figures) are similar to those obtained through indirect measurement methods (Medina and Schneider Citation2018), but can be regarded as complementary rather than competing. In addition to triangulating indirect measurement methods of Kyrgyzstan’s shadow economy, we further suggest that direct measurement methods can be used to capture not only the relevance of the phenomenon but also its intrinsic causes. Indirect methods can certainly be useful in calculating indicators and in determining the extent of informality in a national economy. However, direct methods can also shed light on why this is so. Better understanding motives behind choices made to remain in the shadows will allow policymakers to better address societal needs in the medium term.

Distinguishing between what people do and why they do so points to an important but often overlooked distinction: the difference between the shadow economy and informality. The two terms were, and sometimes still are, used almost as synonyms in some disciplines. However, the flourishing of informality studies in the post-Soviet region has highlighted the importance of distinguishing these two distinct but related concepts (Polese Citation2020). We suggest that the shadow economy and its measurement can be considered as the monetary, or economic, aspect of a larger phenomenon that is best understood through the lens of informality. Informality, from this perspective, is defined as the aggregate of symbolic, material and socio-cultural practices that can push some segments of a population to engage in shadow transactions (and accordingly to remain, partially or completely, in the shadows). The aggregate of these shadow transactions and the actors that engage in these transactions (i.e., under-declared revenues, employees and incomes in a given country) can be understood as the shadow economy (Putnis and Sauka 2020).

Our approach to the Kyrgyzstan shadow economy survey reflects this dichotomy. The survey instrument was designed to facilitate the calculation of the components of the shadow economy, with a focus on underreporting of income, number of employees and salaries, as a percentage of national GDP. However, by adopting a broader frame of questions that included questions on levels of satisfaction with government services and attitudes to tax morale and bribery, we also have gathered data that can provide insights beyond individual rational choice criteria.

This paper presents the findings of the shadow economy survey for 2017 and 2018. These results are used for the calculation of the shadow economy index for Kyrgyzstan, which is estimated as a percentage of GDP. The results are then broken down into distinct values for envelope wages, unreported company income and the underreported number of employees (Putniņš and Sauka Citation2015). The next section discusses the advantages of direct and indirect measurement methods and why it is worth combining them when dealing with shadow economies. The following section locates the paper in the existing literature and explains the relationship between shadow economy (mostly measured using economic criteria) and informality (that includes social and reciprocity practices that cannot be monetized or that develop over a long period of time). The last two sections present the results of the survey and analyse the significance, and the consequences, of the survey’s results.

Measuring the shadow economy: direct and indirect methods

We have adopted the term ‘shadow economy’ to refer to any production of legal goods and services by registered enterprises that are intentionally hidden from public authorities. Shadow economies are difficult to quantify since they are a phenomenon that is not readily visible. The research has offered several ways for estimating the phenomena in a certain nation, which may be divided into ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ methods. Indirect approaches often rely on macro data, whereas direct methods rely on tax audits or surveys (for a review, see Putnins and Sauka 2015).

Individuals hide revenues and perform underground transactions for a number of reasons. They could be producing, or selling, illegal goods and services, or they might simply wish to decrease their taxable income in a given year. What is important here is that the measurement of these flows is difficult because few will, in principle, be willing to share information about their real flows and the reasons that push them to operate in the shadows. Starting from this reasoning, researchers have developed measurement approaches to estimate the size and sectors of shadow economies in several world regions, based on a number of identified correlations between the shadow economy and determinants such as tax burden, quality of institutions, regulations, public sector services, self-employment, unemployment and share of labour force (Schneider Citation2017a).

These correlations have been examined using a variety of sources. One prominent method uses data supplied by the System of National Accounts Statistics to develop discrepancy methods used to measure both hidden and illegal activities (Gyomai and van de Ven Citation2014). Another examines differences between national expenditure and income statistics (MacAfee Citation1980; Yoo and Hyun Citation1998), assuming that revenues can be hidden for tax purposes, but expenditures are not as readily concealed. Discrepancies between the official and actual labour force (Contini Citation1981; Del Boca Citation1981) have also been used under the assumption that a decline in official labour force participation can be interpreted as an increase in the importance of the shadow economy, while the ‘electricity approach’ uses electricity consumption as a proxy for overall economic activity and therefore production (Kaliberda and Kaufmann 1996). Other methodologies include the ‘transaction approach’, relying on measurement for a given year and calculation of its variations, and the ‘currency demand approach’, starting from the assumption that an increase in the size of the shadow economy will increase demand for currency (Schneider Citation1997; Johnson et al. Citation1998a).

In several cases, researchers have managed to build trust with participants and have extrapolated information on roles, dynamics, codes, and norms from such engagement. Such studies have tended to focus on processes and what triggered them rather than seeking to provide overarching estimates of the scale of criminal activity. Direct approaches are valuable for data interpretation and for the elaboration of evidence-based policies to address complex issues and assess their possible risks. Insight from such research has helped answer a range of questions in particular contexts, including why some activities are concentrated in a given geographical area; why some ethnic groups or segments of the society are more likely to engage with certain activities than others; and how governmental agencies and researchers can serve best the interests of the target group while incentivizing the abandonment of unlawful behaviours.

Indirect methods offer a variety of advantages in that they are relatively inexpensive and unintrusive. When applied to countries that use robust statistics and reliable data they can provide excellent starting points to understand the nature of the informal economy. Indirect methods can also help to formulate hypotheses on possible correlations and causations (in other words, what people tend to do). However, they also have a number of potential shortcomings.

First, indirect methods measure unrecorded and unregistered flows without being able to distinguish between illegal and illicit flows and transactions. Some companies produce licit goods and offer licit services but do not report all their transactions to reduce taxable incomes. This can be addressed by inviting companies out of the shadows and is mostly an economic governance issue. Other actors, however, generate illegal products and services (i.e., drugs, trafficking): they cannot be ‘invited out of the shadows’ but should simply be liquidated.

Second, indirect measurements tell us that shadow economies are there but not why. There are a variety of reasons why some actors, even those producing legal goods, might want to remain in the shadows, and a better understanding of these motives is at the basis of more tailored policymaking and better governance mechanisms. Indirect measurements offer little understanding of the social and cultural reasons why some people might want to remain in the shadow and thus not enable us to identify any alternative or local solution to the problem. Direct measurement methods, in contrast, benefit from feedback from the very actors involved in these dynamics and explain the rationale behind certain choices.

It would be difficult to claim that direct approaches are immune from error, including possible underreporting of figures (Merriman et al. Citation2010; Rand 2014) and a related incapacity to take into account unregistered companies. Since measurements are based on surveys of registered companies, they will not be able to take into account the totality of the non-observed economy. Such methods nonetheless mitigate against the risk of mixing illegal and informal activities and can suggest alternate policies that address both separately, rather than prescribing solutions that attempt to address both types of activities at once. While they leave out unregistered companies, they also exclude illegal companies and producers. They offer respondents room to elaborate on their responses and thus provide ground for explanations about the persistence of and preferences for shadow transactions (Putniņš and Sauka Citation2015; Reilly and Krstic 2017).

One name and many flavours: the ‘informalities’ of Kyrgyzstan

When applied to Kyrgyzstan, these concepts seem largely underexplored. Previous measurements of the shadow economy in the region have used the MIMICFootnote8 approach (Schneider Citation2015; Feld and Schneider Citation2010; Williams and Schneider Citation2016). This approach was implemented within the framework of a longitudinal study encompassing a large number of countries worldwide with little specific interest in Kyrgyzstan or the Central Asian region. To explore this gap in empirical studies, both a systematic literature review on the shadow economy in Kyrgyzstan and a broader qualitative literature review on informality have been conducted.Footnote9 Of 36 studies reviewed, we found no previous attempt to measure the size of the informal economy, nor did we find a complete account of the reasons for engaging in such activities.Footnote10

However, this literature survey did identify a number of interesting tendencies. The review identified the most popular understandings of informality research in the region, which included studies that focus on informal payments in the health and education sectors (Gaitonde et al. Citation2016; Baschieri and Falkingham Citation2006; Falkingham, Akkazieva, and Baschieri Citation2010; Ruiz Ramas Citation2016), on housing and informal dwellings (Hatcher Citation2015; Cramer Citation2018; Isabaeva Citation2021; Sanghera Citation2020), transportation (Rekhviashvili and Sgibnev Citation2020), and governance in prisons (Kupatadze Citation2014; Butler, Slade, and Dias Citation2020). provides a summary of the major trends in the region.

Table 1. Main tendencies on informality in the Eurasian region.

The variety of work on informality in Kyrgyzstan should not be a surprise. After all, informality is both an intuitive and mouldable concept (Peattie Citation1987) spawning across several dimensions, including economic, legal, technical, organizational, political and cultural areas, as well as nine separate categories of informality and over a hundred subcategories (Boanada-Fuchs and Fuchs Citation2018, 407–409). As a result, there are some particular ‘flavours of informality’ (Polese Citation2018) that have been particularly attractive to researchers focusing on Kyrgyzstan.

First, the concept of informal politics or governance has been used to explore the way leadership is constructed and maintained across regions and clans (Hale Citation2014; Ismailbekova Citation2018); it has also been recognized that informality may affect democratic development, institution-building and social mobilization (Hale Citation2014; Temirkulov Citation2008). In ground-breaking work on informal governance in the post-Soviet space, Ledeneva (Citation2006, Citation2013) argued for the importance of understanding the sistema behind informal governance in Russia, drawing from her earlier work on blat and long-term relations in business and politics (Ledeneva Citation1998). Her work resonates with that of other scholars who have argued that informality is not necessarily disruptive when it comes to high-level governance structures (Darden Citation2008; Morris Citation2019; Polese et al. 2017). Indeed, long-term relations and the practice of blat in Russian society and politics allowed Ledeneva (Citation1998, Citation2013) to explain how Russian politics works in practice, as opposed to how they should work in theory. This way of thinking has also been explored beyond Russia. Isaacs (2013), for example, has examined the relationship between formal and informal politics in Kazakhstan, while Polese, Ó Beacháin, and Horák (Citation2017) have considered the unintended consequences of a personality cult in Turkmenistan.

Kyrgyzstan, and indeed Central Asia more generally, have been included in debates on participation in the informal sector both from regional and global comparative perspectives (Abbott and Wallace Citation2009; Charmes Citation2012; Kraemer and Wunsch 2016). Authors have explored the relationship between informality and labour market developments (Mirkasimov and Ahunov Citation2017; Rodgers and Williams Citation2009) and the way informality affects the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Makhmadshoev, Ibeh, and Crone Citation2015; Morris and Polese 2013; Rudaz Citation2017). Bazaars have received particular attention because they are not only places where the economy is developed (Karrar Citation2019; Fehlings and Karrar Citation2020; Cieślewska Citation2013), but also are regarded as spaces where the formal and informal meet to contribute to entrepreneurship and initiative (Polese and Prigarin Citation2013; Rudaz Citation2020), where power relations are redefined (Spector Citation2018) and where citizens can generate new social, kinship and economic orders well beyond what the state is trying to propose (Morris Citation2016; Steenberg Citation2016, Citation2020).

Another important field of research has been concerned with the boundary between the moral and immoral (Botoeva Citation2014; Sanghera, Ablezova, and Botoeva Citation2012), reminding us that individual and state morality do not automatically or naturally overlap (Polese Citation2016) not least because the best outcome for an individual is not necessarily the best outcome for a society and the state administering them. When this happens, networks of solidarity may replace the state and rotate around gender, family and kinship identities (Commercio Citation2010; McGuire Citation2017; Sanghera, Ablezova, and Botoeva Citation2012; Satybaldieva Citation2018; Kuzhabekova and Almukhambetova Citation2021), pass through religious identity and education (Murzaraimov and Koylu Citation2019) and go as far as evolving in places where the state is formally present such as prisons or police offices (Butler, Slade, and Dias 2020; Cramer Citation2018; Kupatadze Citation2014). In this respect, informal social networks and sub-economic structures can function alongside allegedly functioning formal economies, as demonstrated in studies ranging from waste management (Sim et al. Citation2013) to livestock (Kasymov and Thiel Citation2019), informal housing (Isabaeva Citation2021) or the bazaar economy (Baitas Citation2020; Karrar Citation2019). Taken altogether, the above works suggest that shadow economies, and participation in underground activities, are too complex to be regarded as merely economic phenomena. They are embedded, lived and negotiated at the everyday level between the state, economic actors, family structures and trust networks.

Finally, a last stream of research in the region deals with corruption from several angles. The post-socialist region has produced a number of nuanced studies exploring relationships and boundaries between corruption and informality (Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva Citation2017; Polese Citation2009; Polese and Stepurko Citation2016; Polese et al. Citation2018; Stepurko et al. Citation2017). Authors have suggested that while informality is a relevant phenomenon that cannot be ignored, its ineffable nature makes it difficult to conceptualize and even more difficult to measure. In attempting to be sufficiently inclusive, an excessively broad definition of informality overlaps to too great an extent with other social phenomena (Routh Citation2011) and generates confusion between illegal and informal economies (Morris Citation2016; Polese Citation2020). Studies have tried to explore the everyday dimension of corruption and why people engage in acts that are formally illegal and punishable (Engvall Citation2014; Marat Citation2015), sometimes framed in a mutual support framework (Ruiz Ramas Citation2016) or by trying to understand what this may mean in a given macroeconomic context (Baschieri and Falkingham Citation2006; Gaitonde et al. Citation2016; Urbaeva, Jackson, and Park Citation2018).

Two main gaps emerge from this literature survey this article addresses. First, there has been little, if any, work that explores the way shadow economies are generated, performed and lived by those very actors that policies are supposed to address. Empirically, the next section will show the way shadow economies are performed and reproduced in practice, what sectors are the most important, and will discuss attitudes towards activities that contribute to the shadow economy. Second, there is a significant gap in understanding the boundary between informality and shadow economies in the region. Accordingly, the empirical section explores the relationship between actions (shadow economy) and the perceptions and attitudes generating them (informality).

Methodology

The methodology used for the survey has been developed and improved for over a decade (Putniņš and Sauka Citation2015; Putnins, Sauka, and Davidescu 2019). It started with a survey in Latvia in 2009 which was subsequently expanded to the three Baltic republics in 2010. The results of the survey are regularly discussed during a policy conference in Riga with the participation of all major political figures. Recommendations are taken into account to better address informal economies at the national level. The Kyrgyz study is constructed around 502 telephone interviews with manager representatives. Companies were stratified according to their annual revenue and selected from a national database of registered firms.Footnote11

Surveys face the risk of underestimating the total size of the shadow economy due to non-response and false answers, given the sensitivity of the subject. By applying data-gathering strategies demonstrated in prior studies, our method reduces this risk by boosting the likelihood of eliciting accurate responses. These techniques include maintaining the confidentiality of respondents’ identities; framing the survey as a study of satisfaction with government policy (similar to Hanousek and Palda 2004); phrasing misreporting questions indirectly, eliminating misreporting responses, and controlling for characteristics that correlate with probable untruthful responses; and asking about ‘similar businesses in the industry’ rather than the respondent’s real firm (Sauka Citation2008).

Owners, directors and managers of firms were interviewed over the phone for five minutes on average. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (1) external influences and satisfaction; (2) shadow activities; (3) company and owner characteristics; and (4) attitudes of entrepreneurs. The questionnaire began with non-sensitive questions on satisfaction with the government and tax policies, before moving on to more sensitive questions regarding shadow activities and purposeful misreporting in order to boost response rates and veracity. Methodological studies of survey design in the context of tax evasion and the shadow economy advocate this ‘gradual’ approach (e.g., Gerxhani Citation2007; Kazemier and van Eck Citation1992).

Some entrepreneurs refused to answer sensitive inquiries concerning shadow operations, even when asked indirectly. Giving a score of ‘0’ to all the questions, implying that no shadow activity occurred during the years under investigation, is one approach to avoid providing true answers. These situations are considered as non-responses, reducing negative bias in shadow activity estimations. Both Gerxhani (Citation2007) and Hanousek and Palda (Citation2004) have addressed and used this strategy in their separate works.

The first group of questions related to ‘external factors’ asked respondents to rate their satisfaction with their country’s State Revenue Service, tax policy, business legislation and government assistance for entrepreneurs. The questions employed a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘1’ (‘very unsatisfied’) to ‘5’ (‘very satisfied’). The first section of the questionnaire also included two items on entrepreneurs’ social norms: tolerance of tax evasion and tolerance of bribery. The measure of tolerance also acts as a control variable, allowing for an underestimation of the scope of shadow activities. The second section on ‘informal business’ is based on Baumol’s (Citation1990) concepts of productive, unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship, assessments of ‘deviance’ or ‘departure from norms’ within organizations (e.g., Warren Citation2003), and empirical studies of tax evasion in various settings (e.g., Aidis and Van Praag Citation2007; Fairlie Citation2002). We determine the extent of shadow activity by asking entrepreneurs to estimate the degree of underreporting of business income (net profits), underreporting of numbers of employees, underreporting of employee salaries and the proportion of revenues paid in bribes. In the third part, we added questions on entrepreneurs’ opinions about the likelihood of getting detected for various sorts of shadow activity, as well as the severity of penalties if found intentionally misreporting. We also ask a question conceived to measure the number of unregistered businesses. Despite the fact that we asked this question to registered business owners/managers, we felt that as rivals and experts in their field, they were likely to know how many unregistered enterprises exist in the industry. In the fourth section of the questionnaire, we extracted entrepreneurs’ thoughts and attitudes concerning tax evasion by including questions on tax morale. We drew from Torgler and Schneider (Citation2009) in this regard, who defined tax morale as ‘a belief in contributing to society by paying taxes’ and ‘a moral imperative to pay taxes’ (230). We phrased the tax morale question indirectly. We also included a question on community belonging as well as a question about perceived contribution to the economy and society in general, all of which are linked to tax morale.

Following the collection of data, we constructed a shadow economy index as a proportion of GDP using the income approach. As a result, GDP equals the sum of employees’ gross salary (gross personal income) and enterprises’ gross operating revenue (gross corporate income). The calculation of the Index was done in three steps: (1) using survey responses, we estimated the degree of underreporting of employee salary and underreporting of enterprises’ operational revenue; (2) we calculated each firm’s shadow production as a weighted average of underreported employee remuneration and underreported operating income, with weights indicating the shares of employee remuneration and businesses’ operational revenue in GDP; and (3) a production-weighted average of shadow production across enterprises was calculated.

First, URiOperatingIncome was computed directly from the corresponding survey question (7), underreporting of business i’s operational income. However, there are two types of underreporting of employee remuneration: (1) underreporting of salaries, or ‘envelope wages’ (question 9); and (2) unreported employees (question 8). When the two components are added together, the total unreported share of employee remuneration for i is:

In the second stage, we calculated a weighted average of underreported personnel and underreported corporate income for each business, yielding an estimate of the unreported (shadow) share of production (income):

where αc is the ratio of employee remuneration to the total of employee remuneration and gross operating revenue of companies. We used Eurostat data to determine ac for each nation, c, in each year. It is crucial to use a weighted average of the underreporting indicators rather than a simple average to interpret the shadow economy index as a percentage of GDP. To calculate the shadow economy index for nation c, we took the weighted average of underreported production, ShadowProportioni, across enterprises in that country:

The weights, wi, represent each business’s proportionate contribution to the country’s GDP, which we calculated using the relative amount of salaries paid by each firm. The weighting in this final average is critical, as it is in the second stage, to allow the shadow economy index to reflect a percentage of GDP.

Parallel orders and economies: results and discussion

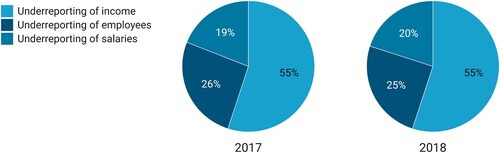

The shadow economy index, calculated using the Putniņš and Sauka (Citation2015) approach, shows that the level of the shadow economy in Kyrgyzstan was 46.1% of its GDP in 2017 and 44.5% in 2018. These figures are very close to the highest levels recorded internationally – 60.64% recorded for Zimbabwe, recorded by Medina and Schneider (Citation2018). On the opposite end of the spectrum, Japan recorded 10.41% of GDP (2005–15), Sweden 13.28%, and Switzerland 7.24%, the lowest value of any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country. It is clear from these figures that the shadow economy is thriving in Kyrgyzstan and occupies a large portion of the country’s economy. Underreported business income comprises that largest component (55% in both 2017 and 2018), followed by 25% related to underreported numbers of employees and envelope wages at 19% ().

The survey also identified sectors where the shadow economy is more present. In 2018 the shadow economy permeated 50% of wholesale and 47.1% of the manufacturing sector. The results are staggering also in retail (46.3%), services (43.4%) and construction sectors (38%). The miscellanea category covered by all the others is affected at 33%. In both 2017 and 2018, the most affected locations proved to be the largest cities, including the capital Bishkek (53.6% in 2017 and 47.6% in 2018), Chuy (52.6% in 2017 and 47.4% in 2018), and Issyk-Kul (54.1% in 2017 and 52.7% in 2018, respectively). Other regions such as Talas, Naryn and Jalal-Abad had levels of shadow economy between 35.0–38.5% in 2017 and 30.0–34.5% in 2018. Osh Oblast (also including Osh city) was at 43.2% in 2018 and 39.0% in 2018, while Batken had only 29.9% in 2017 and 26.0% in 2018% of their respective contributions to the GDP.

While around a third of respondents (32.5%) declared not having used bribery in the past 12 months, another third (28.3%) stated that they had used 1–10% of their revenues to bribe officers, whereas 16.7% of respondents this amount was much higher and accounted for 11–30% of their revenue. Payments of higher amounts were rare and only 2.6% and 0.4% of interviewees declared using 31–50% and 51–75% of their revenues, respectively, for this purpose. Payments used to secure contracts with the government were used by more than half of the respondents and these payments averaged 7% of the total contract value.

Despite high figures suggesting that informality is widely present in the country, people’s attitudes were surprisingly pessimistic. In theory, an individual draws a cost–benefit analysis weighing the likelihood of being caught, the damage that will happen to them, and the benefits expected in engaging in informal transactions (Allingham and Sandmo 1974; Putnins and Sauka 2018; Yitzhaki Citation1974). However, as shown in , respondents seemed genuinely concerned with the chances of getting caught, with 40% considering the prospect to be highly likely (75–100% chances). A further 49% were concerned that they might be caught for underreported employees or their salaries. When it comes to underreporting profit, 50.4% of the respondents considered having a 75–100% chance to be caught. By contrast, only 5% interviewed believed authorities would not discover underreported business profits at all, with an additional 5.4% of respondents seeing the risk of being caught as minimal (1–10%).

The data also showed a similar percentage of respondents who perceived zero risk of being caught with 6% identifying no risk for underreporting the number of employees, and 6.4% identifying similarly for underreporting salaries. A higher percentage (13.5%) perceived no risk of being caught for bribery payments compared with the other three sets of data, with a further 7.4% of respondents expecting only a 1–10% probability of being caught. An equal number of respondents identified an 11–30% risk of being caught for bribery, not too dissimilar from the 7% of interviewees who perceived the same probability was applicable regarding the risk of being caught for underreporting salaries. Only 5.6% felt that there was a 1–10% chance of being caught for underreporting salaries, the lowest result in that individual data set. Moreover, 6.3% of respondents perceived a 1–10% probability of being caught for underreporting the number of employees, while a similar 6.2% perceived the risk in the 11–30% range. 8.2% also perceived an equal risk of 11–30% regarding being caught for underreporting business profits.

Perception of risk for underreporting is around 20% for salaries or bribes (20%), business income (18.7%) and number of employees (21.7%). These were people feeling that there is a real and concrete risk of being caught. Consequences for being caught underreporting are considered serious by more than half of respondents. A total of 55.4% would expect a fine at a level to compromise the company’s viability (8.4%) or even survival (4.2%). This, against a rough third (30.7%) expecting nothing too significant would change for the company.

With regards to tax morale (Putnins, Sauka, and Davidescu 2018), when asked to speak in general terms, respondents were asked if they believed that other companies would consider tax avoidance an acceptable behaviour. 30.9% disagreed and 23.5% strongly disagreed with the statement. However, when asked whether tax avoidance was a legitimate behaviour, 38.0% agreed and 45.2% disagreed, corroborating the suggestion that certain behaviours seem more unacceptable when performed by others but, when you are concerned in the first person, one can always find a moral justification (Ariely Citation2002). This is consistent with findings on Ukrainian entrepreneurs (Polese Citation2013).

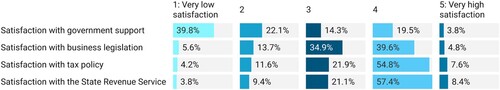

In line with this, it was interesting that Kyrgyz entrepreneurs are more satisfied with the state revenue service (to which they gave a score of 3.57 on a 1–5 scale) than other state services, scoring an average of 3.57. Similarly, the government’s tax policy scored an average behaviour of 3.5, and the quality of business legislation scored 3.25. Further expanding the data in order to highlight the distribution of responses within the surveys, the results show that 57.4% identified as satisfied with the state revenue service, while 54.8% and 39.6% responded similarly with respect to the government’s tax policy and business legislation respectively.

The (im)morality of shadow economies

The Kyrgyz economy strives to maintain a facade of normalcy but is clearly dysfunctional across broad swathes of economic activity, with the shadow economy accounting for almost half of the economy of the country (46.1% in 2017 and 44.5% in 2018). Government support to entrepreneurs is perceived as weak, with satisfaction ranking low (2.25 on a five-point scale) and 40% of respondents feeling disappointed. This may explain the relatively high tolerance for bribery, with 36.1% of respondents believing that bribery is a tolerable behaviour. With these figures, widespread informality should not be considered a mystery. Rather, one should be surprised by the level of compliance with state instructions by a significant fraction of the country’s entrepreneurs, probably due to relatively effective coercion and punitive mechanisms. Entrepreneurs strive to maintain a facade of normalcy and compliance that allows them to sleep at night while paying the minimal amount of taxes to a state that they tend not to trust. Yet, two sets of considerations are needed here about (1) the alleged (im)morality of shadow economy and (2) what their existence and persistence can tell us about the quality of governance.

First, Kyrgyz entrepreneurs engage in behaviours that are not only punished but also considered socially unacceptable in Western settings. They hide revenues, exchange favours, and pay bribes. But is it all so ‘immoral’ after all? Non-monetary informal practices are common across the world both in transitional and rich countries. The difference is that countries with limited informality have worked hard to limit some economic consequences of informality that are considered ‘bad’ whereas they have kept those that are viewed as neutral or not particularly harmful. Yet, even in such cases, a large number of informal practices are still widespread and contribute to the construction of governance both in the Global North and South (Polese Citation2020). Besides, inasmuch as shadow economy figures are higher in the transitional world, similar but legalized practices exist in the Western world. Tax avoidance has been used, more elegantly than tax evasion, as a term to indicate a company that manages to legally reduce its taxable income (Naylor Citation2004). Tax avoidance is not illegal, since transferring profits and losses to and from other countries, as well as investing or paying for services elsewhere is allowed. But, as the Panama papers have shown, boundaries are blurred and what could be legal in one country can be illegal and/or socially unacceptable in another. Kyrgyz companies may underreport the number of employees or pay a part of the monthly salary in a white envelope. Yet, companies in Europe and the United States often require personnel to register as independent contractors and hire them as consultants to avoid paying social insurance contributions. In other cases, companies offer tax-free benefit packages such as company phone, gym subscriptions and lunch vouchers. The same thing is done in less elegant ways in Kyrgyzstan in the form of envelope payments.

What we know about informality and shadow economy could be combined and used to improve the quality of governance. We are not suggesting that coercion or tighter controls will not work, but rather that such measures will be more effective when combined with measures reinstating trust in the state and by making entrepreneurs feel part of a community with responsibilities to contribute to the development of their society. The embeddedness of social development with profit-generating activities is already a pillar of Islamic finance (Çizakça Citation2015), an area where Western modes of governance (and approaches to tackling informality) could actually worsen rather than improve things. Evidence suggests that economic damage resulting from high levels of informality has been best reduced only by prompting changes in individual (and then societal) behaviours and attitudes towards the state (De Soto Citation1989; Williams Citation2015). This has included creating incentives to re-channel shadow companies and activities into more legal spheres of the economy and offering attractive opportunities in the formal economy to informal workers (ILO Citation2016; Unni Citation2018). Already Bourdieu (2020) suggested that individual morality is circumstantial and that citizens stick to state morality only when it is convenient for them. Overlapping of individual, societal, and state morality is not automatic but is rather the result of efforts by the state to create the conditions to encourage its citizens to comply with state morality (Polese and Stepurko Citation2016). The very foundation of Weberian and post-Weberian states is that individual good may be, in a number of cases, considered secondary to the overall good of society (or of the state). Accordingly, the state must act as a guarantor of the public good so as to look for solutions that are economically viable for a large majority of the population, rather than for a handful of people.

By way of conclusion: on informality and governance

The relationship between the shadow economy and informality is ambiguous. While studies drawing on economic approaches conflate the two words into a single concept, literature from other disciplines has moved beyond an economic, economistic, or monetary understanding of informality to take into account a variety of ways to bypass the state and get things done (Böröcz Citation2000; Giordano and Hayoz Citation2014; Ledeneva Citation2018). The shadow economy is usually referred to as the consequence of underreporting of income, salaries, or employee numbers (Putniņš and Sauka Citation2015). By contrast, informality expands the range of activities to the aggregate of non-monetary and non-economic practices used to interact with other individuals and organizations to maximize the benefits of participation in society. Drawing on Gudeman’s (2015) distinction between the market and society, informality can be regarded as being rooted in social and cultural beliefs, habits, and customs that are maintained in spite of the presence of an overarching entity (usually the state) allegedly regulating the life of its citizens. For Kyrgyzstan, the tendency of citizens and enterprises to remain in the shadows, and the widespread social acceptance of shadow economic activities and transactions, may depend on several factors. It is certainly related to individual preferences to maximize benefits and minimize costs at the expense of the state. However, social and cultural factors also play a role. The economic and legal advantages of paying taxes are that you can legitimately expect something in return from the state (services, infrastructures) and that you will increase the quality of your sleep (in that you will not be constantly worried about being caught). However, an ineffective state can neutralize these advantages.

In such conditions, taxation then becomes an exercise in which individuals try to hand over as little as possible to the state. Corruption and state ineffectiveness, which involves abuse of power by state officers, also erodes the advantages of the ‘good sleep’ benefit. ‘It is highly possible that I will be fined, no matter how much I invest into innovation and compliance, what’s the incentive to do so?’ Business owners in Kyrgyzstan seemed genuinely concerned with the chances of getting caught and on average 40−50% of them considered that they faced a 75–100% chance of being caught for bribery, underreporting employees, salaries, or business profit. However, despite this, the shadow economy index, calculated with Putniņš and Sauka (Citation2015) approach, shows that the level of the shadow economy in Kyrgyzstan is 46.1% of its GDP in 2017 and 44.5% in 2018.

By virtue of the above reasoning, the main question here is not ‘what is the size of the Kyrgyz shadow economy’. There is no real difference if the final calculations show 30%, 35% or 40%. What is important is that the shadow economy in the country occupies a significant share of the daily economy, is composed of widespread practices, and affects state capacity. As a corollary, and possibly even more importantly, measures to tackle the shadow economy should take into account the results of direct measurement approaches. That is, any interventions should be based on efforts to build trust in institutions. However, the advantages of taking into account the perspective of those who are supposed to be the target of such policies are undeniable.

In practical terms, this means that if the Kyrgyz state aims to increase the compliance rates of entrepreneurs it should strengthen its response to the problems that have required the use of informal practices in the first place (i.e., speeding up and slimming down bureaucracy, improving assistance to its citizens, cracking down on capricious and corrupt enforcement of rules for private gain, etc.) rather than increasing punishments that businessmen already fear. Preference for informal solutions to problems over formal ones may be regarded as a form of resistance – a de facto protest against the malfunctioning of the state itself. Unfortunately, successive governments have not yet taken this perspective on board; instead cases of substantial mismanagement populate the Kyrgyz political realm (Palickova and Gotev Citation2019) that are unlikely to reinforce trust in national institutions (Moma Citation2021).

Shadow activities in Kyrgyzstan may stem also from a lack of trust in state support and institutions, and are in many respects a manifestation of divergence between individual and state morality. Many Kyrgyz companies fall well behind their Western counterparts, at least formally. In reality, their strategy is simply less formal for a number of reasons ranging from a lack of functioning regulatory frameworks to a different way of understanding business rules. These tendencies need further exploration to better understand how steps to formalize or end informal practices can lead to better economic and social performance and encourages creativity and innovation, rather than the suffocation of business and initiative. We hope through the research underpinning this paper, to have opened up room for debate about what informal practices can be studied and can be regarded as useful for the state in contrast to obnoxious practices that are rightly addressed using coercive legal measures at national and international level. Once this distinction is developed further, we believe policymaking can only gain through increased capacity to better address the primary necessities of citizens, while economic actors can be encouraged to seek cooperation with the state and to operate within more formalized frameworks.

Acknowledgement

The writing part of the article occurred during a visiting fellowship at Ritsumeikan University, as well as during a research stay at the Institute for Social Theory and Dynamics of Hiroshima. The authors thank their colleagues who contributed with suggestions or logistical support, including Sayaka Ogawa, Hideo Aoki, Rob Kevlihan and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The World Bank and ILO suggested that between 500 million and 1.5 billion more people could be at risk of entering precarious and informal employment, with women, migrants and young people being the most affected categories (Deutsche Welle Citation2020).

2 Already established as an annual survey for Latvia and then the Baltics since 2010, it has been applied to Moldova and Romania (since 2016), Poland (2015–16) and Kosovo (2018). In 2019 it was also implemented in Georgia, Russia and Ukraine (2019) in the frame of the project ‘SHADOW: An Exploration of the Nature of Informal Economies and Shadow Practices in the Former USSR Region’. For a full presentation of the project, see http://shadow-rise.eu/. The survey was carried out by the Kyrgyz partner SIAR Research and Consulting (Citation2019) via 502 phone interviews between April and June 2018, with managers identified through random stratified sampling, as discussed by Putniņš et al. (2018).

3 The Ease of Doing Business rank is compiled by the World Bank. This set refers to 2019; see https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings?region=europe-and-central-asia/.

4 The Global Freedom Scores (GFS) are compiled on a scale from 0 to 100, where a low score indicates a low level of freedom. The GFS is compiled by Freedom House; see https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores/.

5 Government effectiveness is indicated on a scale between −2.5 and 2.5, where the former is the lowest level and the latter the highest. Government effectiveness is part of the Worldwide Governance Indicators of the World Bank, and this last set refers to 2018; see https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?Report_Name=WGI-Table&Id=ceea4d8b/.

6 The shadow economy index is calculated as percentage of GDP by the Global Economy, with last data referring to 2015; see https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/shadow_economy/Asia/.

7 For the 2019 Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International, see https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/.

8 MIMIC is employed by researchers studying the effects of an unobservable latent variable. The approach is used in a number of disciplines, from psychology to applied econometrics.

9 The study was conducted in February 2021 on Scopus and the Web of Science (WoS) of the Institute of Scientific Information. Selected keywords included ‘informal’ and ‘Kyrgyzstan’; and ‘informality’ and ‘Kyrgyzstan’. Given that the informal economy is not the only expression used to identify the concept, third and fourth searches employing ‘shadow’ and ‘underground’ were also made, along with ‘Kyrgyzstan’. For completeness, the review did not limit the search temporally or along disciplinarily lines as long as the study met two main criteria: that the informal dimension had to be the focus of the research and that Kyrgyzstan had to be a major focus of the study. For example, an article studying Kyrgyz migrants in Russia was not considered as part of this review. Similarly, an article listing the informal economy as one of the many variables of a multivariate regression was not deemed suitable. While for the first search, the total number of entries recorded was 70 and 52 for Scopus and WoS, respectively; the second (6 and 5), third (14 and 6) and fourth searches (19 and 6) were much less fruitful. In total, 36 studies were included in the review. For a full list, see Table A1 in the supplemental data online.

10 The only exception is moneylending and moral reasoning on the capitalist frontier in Kyrgyzstan, but the article is widely different in objective and focus as it limited its enquiry to the phenomenon of informal moneylending adopting an anthropological approach (Pelkmans and Umetbaeva Citation2018).

11 The Kyrgyz government also carries out an annual survey designed to measure the shadow economy in Kyrgyzstan. According to the latest survey, the shadow economy of the country in 2017 ranged between 23.6% and 37.0% of GDP; see https://24.kg/english/129199_Shadow_economy_in_Kyrgyzstan_ranges_from_23_to_37_percent_of_GDP/. This is lower than the amount calculated by SIAR (Citation2019): 46.1%. Nevertheless, our study offers two advantages: first, the analysis of the Kyrgyz national agencies has a much wider confidence interval (more than 10% variation against 3.57% of our method); second, the sample of enterprises surveyed by the Kyrgyz state was 302 against our 502 responses. Our participation rate was 91%, with 550 companies being contacted and 502 participating. As clarified so far, while our data on the size of the informal economy cannot be considered conclusive, this is also one of the most precise measurements possible.

References

- Abbott, P., and W. Claire. 2009. “Patterns of Participation in the Formal and Informal Economies in the Commonwealth of Independent States.” International Journal of Sociology 39 (2): 12–38. doi:10.2753/IJS0020-7659390201

- Ahmed, F. Z. 2013. “Remittances Deteriorate Governance.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (4): 1166–1182. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00336.

- Aidis, R., and V.P. Mirjam. 2007. “Illegal Entrepreneurship Experience: Does it Make a Difference for Business Performance and Motivation?.” Journal of Business Venturing 22 (2): 283–310. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.02.002

- Allingham, M. G., and S. Agnar. 1972. “Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Public Economics 1 (3-4): 323–338.

- Ariely, D., and W. Klaus. 2002. “Procrastination, Deadlines, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment.” Psychological Science 13 (3): 219–224.

- Baez-Camargo, C., and L. Alena. 2017. “Where Does Informality Stop and Corruption Begin? Informal Governance and the Public/Private Crossover in Mexico, Russia and Tanzania.” Slavonic & East European Review 95: 49–75. doi: 10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.95.1.0049

- Baitas, M. 2020. “The traders of Central Bazaar, Astana: motivation and networks.” Central Asian Survey 39 (1): 33–45. doi: 10.1080/02634937.2019.1697642

- Baumol, W. J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive.” The Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): 893–92.

- Baschieri, A., and J. Falkingham. 2006. “Formalizing Informal Payments: The Progress of Health Reform in Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 25 (4): 441–460. doi:10.1080/02634930701210435.

- Boanada-Fuchs, A., and B.F. Vanessa. 2018. “Towards a Taxonomic Understanding of Informality.” International Development Planning Review 40 (4): 397–421. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2018.23

- Böröcz, J. 2000. “Informality Rules.” East European Politics and Societies 14 (2): 348–380.

- Botoeva, G. 2014. “Hashish as Cash in a Post-Soviet Kyrgyz Village.” International Journal of Drug Policy 25 (6): 1227–1234. Epub 2014 Feb 3. PMID: 24594222. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.016.

- Butler, M., G. Slade, and C. N. Dias. 2018. “Self-Governing Prisons: Prison Gangs in an International Perspective.” Trends in Organized Crime. doi:10.1007/s12117-018-9338-7.

- Charmes, J. 2012. “The Informal Economy Worldwide: Trends and Characteristics.” Margin: the Journal of Applied Economic Research 6 (2): 103–132. doi: 10.1177/097380101200600202

- Cieślewska, A. 2013. “From Shuttle Trader to Businesswomen: The Informal Bazaar Economy in Kyrgyzstan.” In The Informal Post-Socialist Economy: Embedded Practices and Livelihoods, edited by Jeremy Morris and Abel Polese, 121–135. Routledge.

- Commercio, M. E. 2010. Russian Minority Politics in Post-Soviet Latvia and Kyrgyzstan: The Transformative Power of Informal Networks. University of Pennsylvania Press. Accessed April 14, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fj6hf.

- Cooley, A., and J. Heathershaw. 2017. Dictators Without Borders: Power and Money in Central Asia. Yale University Press. doi:10.1093/ia/iix172.

- Cooley, A., and J. C. Sharman. 2015. “Blurring the Line Between Licit and Illicit: Transnational Corruption Networks in Central Asia and Beyond.” Central Asian Survey 34 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1080/02634937.2015.1010799.

- Çizakça, M. 2015. “Islamıc Wealth Management in History and at Present.” Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics 28 (1).

- Contini, B. 1981. “Labor Market Segmentatation and the Development of the Parallel Economy—the Italian Experience.” Oxford economic papers 33 (3): 401–412.

- Cramer, B. 2018. “Kyrgyzstan’s Informal Settlements: Yntymak and the Emergence of Politics in Place.” Central Asian Survey 37 (1): 119–136. doi:10.1080/02634937.2017.1327421.

- Del Boca, D.1981. “Parallel Economy and Allocation of Time.” Micros (Quarterly Journal of Microeconomics) 4 (2): 13–18.

- Darden, K. 2008. “The Integrity of Corrupt States: Graft as an Informal State Institution.” Politics & Society 36 (1): 35–59. doi:10.1177/0032329207312183.

- De Soto, H. 1989. “The other path.

- Deutsche Welle. 2020. “ILO Warns of Massive Unemployment.” Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/ilo-warns-of-massive-unemployment/av-53286327

- Dodman, D., D. Archer, and D. Satterthwaite. 2019. “Editorial: Responding to Climate Change in Contexts of Urban Poverty and Informality.” Environment and Urbanization 31: 3–12.

- Dias, C.N., B. Michelle, and S. Gavin. 2020. “Prison Gangs.” In Prisons and Community Corrections, pp. 160–172. Routledge.

- Engvall, J. 2014. “Why are Public Offices Sold in Kyrgyzstan?” Post-Soviet Affairs 30 (1): 67–85. DOI: 10.1080/1060586X.2013.818785.

- Eurostat. 2019. Building the System of National Accounts – informal sector. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Building_the_System_of_National_Accounts_-_informal_sector.

- Fairlie, R. W. 2002. “Drug Dealing and Legitimate Self-Employment.” Journal of Labor Economics 20 (3): 538–537.

- Falkingham, J., B. Akkazieva, and A. Baschieri. 2010. “Trends in Out-of-Pocket Payments for Health Care in Kyrgyzstan, 2001–2007.” Health Policy and Planning 25 (5): 427–436. doi:10.1093/heapol/czq011.

- Fehlings, S., and H. H. Karrar. 2020. “Negotiating State and Society: The Normative Informal Economies of Central Asia and the Caucasus.” Central Asian Survey 39 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/02634937.2020.1738345.

- Feld, L. P., and F. Schneider. 2010. “Survey on the Shadow Economy and Undeclared Earnings in OECD Countries.” German Economic Review 11 (2): 109–149.

- Furstenberg, S. 2018. “State Responses to Reputational Concerns: The Case of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative in Kazakhstan.” Central Asian Survey 37 (2): 286–304. doi:10.1080/02634937.2018.1428789.

- Gaitonde, R., A. D. Oxman, P. O. Okebukola, and G. Rada. 2016. “Interventions to Reduce Corruption in the Health Sector.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8: 8. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008856.pub2.

- Gerxhani, K. 2007. “‘Did You Pay Your Taxes?’ How (Not) to Conduct Tax Evasion Surveys in Transition Countries.” Social Indicators Research 80: 555–581.

- Giordano, C., and H. Nicolas. 2014. “The Social Organization of Informality: The Rationale Underlying Personalized Relationships and Coalitions.

- Gyomai, G., and V. Peter Van de. 2014. “The Non-Observed Economy in the System of National Accounts.” Statistics brief 18.

- Hale, H. 2014. “The Informal Politics of Formal Constitutions: Rethinking the Effects of “Presidentialism” and “Parliamentarism” in the Cases of Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Ukraine”. In Constitutions in Authoritarian Regimes (Comparative Constitutional Law and Policy, edited by T. Ginsburg and A. Simpser, 218–244. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107252523.014

- Hanousek, J., and P. Filip. 2004. “Quality of Government Services and the Civic Duty to Pay Taxes in the Czech and Slovak Republics, and Other Transition Countries.” Kyklos 57 (2): 237–252.

- Hatcher, C. 2015. “Globalising Homeownership: Housing Privatisation Schemes and the Private Rental Sector in Post-Socialist Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.” International Development Planning Review 37 (4): 467–486. doi:10.3828/idpr.2015.30.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2016. Formalizing the Informal Sector in South Africa, Malawi and Mozambique. https://www.ilo.org/africa/media-centre/articles/WCMS_531715/lang–en/index.htm.

- Isabaeva, E. 2021. “Transcending Illegality in Kyrgyzstan: The Case of a Squatter Settlement in Bishkek.” Europe–Asia Studies 73 (1): 60–80. doi:10.1080/09668136.2020.1861222.

- Ismailbekova, A. 2018. “Mapping Lineage Leadership in Kyrgyzstan: Lineage Associations and Informal Governance.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 143 (2): 195–220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26899771.

- Johnson, S., K. Daniel, and Z.L. Pablo.1998. “Regulatory Discretion and the Unofficial Economy.” The American economic review 88 (2): 387–392.

- Karrar, H. H. 2019. “Between Border and Bazaar: Central Asia’s Informal Economy.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (2): 272–293. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1532017.

- Kasymov, U., and A. Thiel. 2019. “Understanding the Role of Power in Changes to Pastoral Institutions in Kyrgyzstan.” International Journal of the Commons 13 (2): 931–948. doi:10.5334/ijc.870.

- Kaufmann, D., and K. Aleksander.1996. “Integrating the Unofficial Economy into the Dynamics of Post-Socialist Economies.” Economic transition in Russia and the new states of Eurasia 8: 81–120.

- Kazemier, B., and R. van Eck. 1992. “Survey Investigations of the Hidden Economy.” Journal of Economic Psychology 13: 569–587. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(92)90012-v.

- Kraemer-Mbula, E., and W.V. Sacha, eds. 2016. The Informal Economy in Developing Nations. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316662076

- Kuhn, S., S. Milasi, and S. Yoon. 2018. World Employment Social Outlook: Trends 2018. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_615594.pdf.

- Kupatadze, A. 2014. “Prisons, Politics and Organized Crime: The Case of Kyrgyzstan.” Trends in Organized Crime 17: 141–160. doi:10.1007/s12117-013-9208-2.

- Kuzhabekova, A., and A. Almukhambetova. 2021. “Women’s Progression Through the Leadership Pipeline in the Universities of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 51 (1): 99–117. doi:10.1080/03057925.2019.1599820.

- Labor Market Observatory (LMO). 2018. Report On The Activities Of The 2015–2018 Term Of Office. https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-01-18-528-en-n.pdf.

- Ledeneva, A. 1998. Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ledeneva, A. 2006. How Russia Really Works: The Informal Practices That Shaped Post-Soviet Politics and Business. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Ledeneva, A. 2013. Can Russia Modernise? Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511978494

- Ledeneva, A. 2018. “Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, Volume 2.” Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, Volume 2, edited by Alena Ledeneva, Anna Bailey, Sheelagh Barron, Costanza Curro, and Elizabeth Teague. UCL Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt20krxgs.

- MacAfee, K.1980. “A Glimpse of the Hidden Economy in the National Accounts.” Economic Trends 136 (1): 81–87.

- Makhmadshoev, D., I. Kevin, and C. Mike. 2015. “Institutional Influences on SME Exporters Under Divergent Transition Paths: Comparative Insights from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.” International Business Review 24 (6): 1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.02.010

- Marat, E. 2015. “Global Money Laundering and its Domestic Political Consequences in Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 34 (1): 46–56. doi:10.1080/02634937.2015.1010854.

- McGuire, G. 2017. “Informal Vows: Marriage, Domestic Labour, and Pastoral Production in Kazakhstan.” Inner Asia 19 (1): 110–132. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340081.

- Medina, L., and F. Schneider. 2018. “Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years?”. IMF Working Paper no. 18/17. doi:10.5089/9781484338636.001

- Merriman, D. 2010. “The Micro-Geography of Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Littered Cigarette Packs in Chicago.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2 (2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.2.2.61

- Mirkasimov, B., and O.A. Muzaffar. 2017. “Labor Markets and Informality: The Case of Central Asia.”

- Moma, C. 2021. “Sadyr Japarov: New hope for Kyrgyzstan or a return to autocracy?,” Emerging Europe, 21 February. https://emerging-europe.com/news/sadyr-japarov-new-hope-for-kyrgyzstan-or-a-return-to-autocracy/

- Morris, J., and P. Abel, eds. 2013. The Informal Post-Socialist Economy: Embedded Practices and Livelihoods. Routledge.

- Morris, J. 2016. “Everyday Post-Socialism. Working-Class Communities in the Russian Margins, London.” doi:10.1017/slr.2018.187

- Morris, J. 2019. “The Informal Economy and Post-Socialism: Imbricated Perspectives on Labor, the State, and Social Embeddedness.” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 27 (1): 9–30.

- Murzaraimov, B., and M. Köylü. 2019. “Common Religious Education Activities and Mosques in Kyrgyzstan after Independency.” Cumhuriyet Ilahiyat Dergisi 23 (1): 193–211.

- Naylor, R. T. 2004. Wages of Crime: Black Markets, Illegal Finance, and the Underworld Economy. Cornell University Press.

- Palickova, A., and G. Gotev. 2019. “Scandals in Kyrgyzstan highlight dubious Chinese business practices.” Euractiv, 23rd of July 2019. https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-asia/news/scandals-in-kyrgyzstan-highlight-dubious-chinese-business-practices/

- Peattie, L. 1987. “An Idea in Good Currency and how it Grew: The Informal Sector.” World development 15 (7): 851–860.

- Pelkmans, M., and D. Umetbaeva. 2018. “Moneylending and Moral Reasoning on the Capitalist Frontier in Kyrgyzstan.” Anthropological Quarterly 91 (3): 1049–1074. doi:10.1353/anq.2018.0049.

- Polese, A. 2013. “Drinking with Vova: A Ukrainian Entrepreneur Between Informality and Illegality”. In The Informal Post-Socialist Economy: Embedded Practices and Livelihoods, edited by J. Morris, and A. Polese. London and New York: Routledge.

- Polese, A. 2018. “Informality and Policy in the Making: Four Flavours to Explain the Essence of Informality.” Interdisciplinary Political Studies 4 (2): 7–20. doi:10.1285/I20398573V4N2P7.

- Polese, A. 2019. “Informality in Ukraine and Beyond: One Name, Different Flavours with a Cheer for the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality.” In-formality.com. https://www.in-ormality.com/wiki/Informality_in_Ukraine_and_beyond:_one_name,_different_flavourswith_a_cheer_for_the_Global_Encyclopaedia_of_Informality f.

- Polese, A. 2020. “Shadow and Criminal economies in Ireland: a survey of the main methodologies used worldwide”. Report commissioned by the Irish Department of Justice and Equity, Dublin: Ireland (forthcoming).

- Polese, A., J. Morris, and B. Kovács. 2016. “‘States’ of Informality in Post-Socialist Europe (and Beyond).” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 24 (3): 181–190. doi:10.1080/0965156x.2016.1261216.

- Polese, A. 2009. “'If I Receive it, It is a Gift; if I Demand it, Then it is a Bribe': on the Local Meaning of Economic Transactions in Post-soviet Ukraine.” Anthropology in Action 15 (3): 47–60. doi:10.3167/aia.2008.150305

- Polese, A., and P. Aleksandr. 2013. “On the Persistence of Bazaars in the Newly Capitalist World: Reflections from Odessa.” Anthropology of East Europe Review 31 (1): 110–136.

- Polese, A., and S. Tetiana. 2016. “In Connections We Trust.” Transitions Online 13.

- Polese, A. 2016. Limits of a Post-Soviet State: How Informality Replaces, Renegotiates, and Reshapes Governance in Contemporary Ukraine. Columbia University Press.

- Polese, A., D. Ó/ Beacháin, and S. Horák. 2017. “Strategies of Legitimation in Central Asia: Regime Durability in Turkmenistan.” Contemporary Politics 23 (4): 427–445. doi:10.1080/13569775.2017.1331391

- Polese, A., C.W. Colin, I. Horodnic, and P. Bejakovic. 2017. “The Informal Economy in Global Perspective: Varieties of Governance”. London: University of London.

- Polese, A., S. Tetiana, O. Svitlana, K. Tanel, C. Archil, and L. Olena. 2018. “Informality and Ukrainian Higher Educational Institutions: Happy Together?.” Policy Futures in Education 16 (4): 482–500. doi: 10.1177/1478210318758812

- Polese, A. 2021. “What is Informality?(Mapping)“the Art of Bypassing the State” in Eurasian Spaces-and Beyond.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 1–43. doi:10.1080/15387216.2021.1992791

- Putniņš, T. J., and A. Sauka. 2015. “Measuring the Shadow Economy Using Company Managers.” Journal of Comparative Economics 43: 471–490. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2014.04.001.

- Putniņš, T. J., and S. Arnis. 2015. “Measuring the Shadow Economy Using Company Managers.” Journal of Comparative Economics 43 (2): 471–490. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2014.04.001

- Putnins, T. J., S. Arnis, and A.M.D. Adriana. 2019. “Shadow Economy Index for Moldova and Romania.” In Subsistence Entrepreneurship, pp. 89–130. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11542-5_7.

- Putniņš, T. J., and S. Arnis. 2017. “Shadow Economy Index for the Baltic Countries 2009-2016.

- Reilly, B., and K. Gorana. 2018. “Shadow Economy-is an Enterprise Survey a Preferable Approach?.” Panoeconomicus 66 (5): 589–610. doi:10.2298/PAN161108022R.

- Rekhviashvili, L., and W. Sgibnev. 2020. “Theorising Informality and Social Embeddedness for the Study of Informal Transport. Lessons from the Marshrutka Mobility Phenomenon.” Journal of Transport Geography 88: 102386. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.01.006.

- Rodgers, P., and C.W. Colin. 2009. “Guest Editors' Introduction: The Informal Economy in the Former Soviet Union and in Central and Eastern Europe.” International Journal of Sociology 39 (2): 3–11. doi:10.2753/IJS0020-7659390200

- Routh, S. 2011. “Building Informal Workers Agenda: Imagining ‘Informal Employment’ in Conceptual Resolution of ‘Informality’.” Global Labour Journal 2 (3): 208–227.

- Rudaz, P. 2017. The State of MSME development in Kyrgyzstan. Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg.

- Rudaz, P. 2020. “Trading in Dordoi and Lilo Bazaars: Frontiers of Formality, Entrepreneurship and Globalization.” Central Asian Survey 39 (1): 11–32. doi:10.1080/02634937.2020.1732298

- Ruiz Ramas, R. 2016. “Parental Informal Payments in Kyrgyzstani Schools: Analyzing the Strongest and the Weakest Link.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2015.06.003.

- Sanghera, B. 2020. “Justice, Power and Informal Settlements: Understanding the Juridical View of Property Rights in Central Asia.” International Sociology 35 (1): 22–44. doi:10.1177/0268580919877596.

- Sanghera, B., M. Ablezova, and A. Botoeva. 2012. “Attachment, Emotions and Kinship Caregiving: An Investigation Into Separation Distress and Family Relatedness in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstani Households.” Families, Relationships and Societies 1 (3): 379–396. ISSN 2046-7435. doi:10.1332/204674312X656293.

- Satterthwaite, D., D. Archer, S. Colenbrander, D. Dodman, and J. Hardoy. 2020. “Building Resilience to Climate Change in Informal Settlements.” One Earth 2 (2): 143–156.

- Satybaldieva, E. 2018. “A mob for Hire? Unpacking Older Women’s Political Activism in Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 37 (2): 247–264. doi:10.1080/02634937.2018.1424114.

- Sauka, A. 2008. Productive, Unproductive and Destructive Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical and Empirical Exploration. Vol. 3. Peter Lang.

- Schneider, F.1997. “The Shadow Economies of Western Europe.” Economic Affairs 17 (3): 42–48.

- Schneider, F. 2015. “Size and Development of the Shadow Economy of 31 European and 5 other OECD Countries from 2003 to 2015: Different Developments”. Johannes Kepler.

- Schneider, F. 2017a. “Estimating a Shadow Economy: Results, Methods, Problems, and Open Questions.” De Gruyter Open, Open Economics 2017 (1): 1–29.

- SIAR. 2019. “Shadow Economy Index for Kyrgyzstan”. Bishkek: SIAR Research and Consulting.

- Sim, N. M., D. C. Wilson, C. A. Velis, and S. R. Smith. 2013. “Waste Management and Recycling in the Former Soviet Union: The City of Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic (Kyrgyzstan)”. Waste Management & Research: The Journal of the International Solid Wastes and Public Cleansing Association ISWA 31 (10 Suppl.): 106–125. doi:10.1177/0734242X13499813.

- Spector, R. A. 2017. “Order at the Bazaar.” In Order at the Bazaar. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501709746

- Steenberg, R. 2016. “The Art of not Seeing Like a State. On the Ideology of “Informality”.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 24 (3): 293–306. doi:10.1080/0965156X.2016.1262229.

- Stepurko, T., P. Milena, G. Irena, G. Péter, and G. Wim. 2017. “Patterns of Informal Patient Payments in Bulgaria, Hungary and Ukraine: A Comparison Across Countries, Years and Type of Services.” Health Policy and Planning 32 (4): 453–466. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw147

- Steenberg, R. 2020. “The Formal Side of Informality: Non-State Trading Practices and Local Uyghur Ethnography.” Central Asian Survey 39 (1): 46–62.

- Temirkulov, A. 2008. “Informal Actors and Institutions in Mobilization: The Periphery in the ‘Tulip Revolution’.” Central Asian Survey 27 (3–4): 317–335. doi:10.1080/02634930802536753.

- Torgler, B, and S. Friedrich Schneider. 2009. “The Impact of Tax Morale and Institutional Quality on the Shadow Economy.” Journal of Economic Psychology 30 (2): 228–245. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.004.

- Unni, J. 2018. “Formalization of the Informal Economy: Perspectives of Capital and Labour.” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 61: 87–103. doi:10.1007/s41027-018-0121-8.

- Urbaeva, J., T. Jackson, and D. Park. 2018. “Is Informal Financial Aid Good for Health? Evidence from Kyrgyzstan, a Low-Income Post-Socialist Nation in Eurasia.” Health & Social Work Nov 1;43 (4): 226–234. PMID: 30169692 doi:10.1093/hsw/hly021.

- Warren, D. E. 2003. “Constructive and Destructive Deviance tn Organizations.” Academy of management Review 28 (4): 622–632. doi: 10.5465/amr.2003.10899440.

- Williams, C. 2015. “Policy Approaches Towards Undeclared Work, a Conceptual Framework.” Working Paper 4, IAPP.

- Williams, C. C., and S. Bezeredi. 2018. “Explaining and Tackling the Informal Economy: A Dual Informal Labour Market Approach.” Employee Relations 40 (5): 889–902. doi:10.1108/er-04-2017-0085.

- Williams, C., and F. Lapeyre. 2017. “Dependent Self-Employment: Trends, Challenges and Policy Responses in the EU.” Employment Working Paper No. 228. Geneva: International Labour Office. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3082819.

- Williams, C. C., and F. Schneider. 2016. Measuring the Global Shadow Economy: The Prevalence of Informal Work and Labour. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- World Bank. 2019. Informal Employment Percentages. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sl.isv.ifrm.zs.

- Yitzhaki, S.1974. “A Note on Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Public Economics 3 (2).

- Yoo, T., and J. K. Hyun. 1998. “International Comparison of the Black Economy: Empirical Evidence Using Micro-Level Data, paper presented at 1998 Congress of Int.” Institute Public Finance, Cordoba, Argentina.