In 1970, a 37 year-old veterinary scientist found himself facing a choice that few would hesitate over: to accept the Chair of Veterinary Pathology at Cambridge University, or instead take up a lowly lectureship in Exercise Physiology in the Department of Physical Education at Birmingham University. The brilliant young vet, whose name was Craig Sharp, chose the Birmingham post and in so doing stepped away from a glittering future in veterinary science to follow his other great passion, sport.

The catalyst for the change of career had been a recent conversation at Victoria Park athletics track in Glasgow with John Anderson, a fellow Glaswegian and athletics coach who would go on to coach such notables as David Moorcroft and Liz McColgan. The exchange concerned the basics of exercise physiology, and when Sharp had finished, Anderson exclaimed, “You simply have to tell this to all the other coaches out there. Nobody in sport knows it!” For the next 35 years, Craig Sharp would channel his prodigious talents and energy into this quest

The previous 15 years in veterinary science had hardly been wasted. Studying at Glasgow University Vet School in the 1950’s under Sir William Weipers was to be forged by the white heat of excellence. Lectures were delivered by the leading scientists of the time, including future Nobel Laureates, James Black (of beta blocker fame), Andrew Huxley (sliding filament of muscle contraction) and Jim Watson (double helix structure of DNA), as well as his mentor, Bill Jarrett FRS. After graduating, Sharp worked part-time in large animal veterinary practice (including stints at Mossgiel, the farm of Robert Burns) and as an assistant lecturer while he completed his PhD into the development of the first vaccine (Dictol) against the cattle lungworm parasite, Dictyocaulus viviparus, supervised by Bill Jarrett. This work would later be submitted to the Nobel committee for consideration. In between studies, he was taught Squash by the eminent work physiologist, John Durnin, and captained the Scottish Universities Cross Country team. In 1963, he was seconded to Kenya to help set up a Faculty of Veterinary Science, spending much of the next seven years in East Africa. During his time there, he continued to run (sometimes as the drag for the Limuru Hunt, sprinkling Jackal urine as scent along the way), and played squash for Kenya. His continuing fascination with sport manifested itself in two notable achievements. The first was to set a new record of 6 hours, 48 minutes for running up Mt Kilimanjaro, an ascent of 4000 metres traversing tropical jungle, savannah grasslands, frozen screed and snowfields en route, and the second was to establish the running speed of a cheetah scientifically. This he did by standing in the back of an open Landrover, holding a stopwatch in one hand and proffering meat in the other to a young female cheetah who was timed from the speeding vehicle over 220 yards. The average of three runs gave a speed of 64.3mph. It would take 50 years before Sharp was vindicated by another graduate of the Glasgow Vet School, Alan Wilson, who recorded a top speed of 58 mph, albeit during the twisting and turning of a real hunt (Nature, 2013).

His trackside conversion in 1970 from Veterinary Science to Sport Sciences had early roots. He claimed his love of athletics was sparked by watching Gaston Reiff beat Emile Zatopek by 0.2 s in the 1948 London Olympic 5000m final, alongside his father. Later, as a young vet, his many interactions with John Durnin in Glasgow and readings of early exercise physiology texts (including a 1965 article in Scientific American entitled simply “The Physiology of Exercise”) further influenced him, and he was already well schooled in the practical business of training at a high level for squash and running. In addition, he had been filling in time since his return from Africa as a professional squash coach, impressing on him the central role of the coach in elite sport which would be a guiding tenet of his new career.

This began at Birmingham University in 1971. Before long, Sharp’s abilities as a scientist, communicator and coach were shaping the approach to sport nationally. He co-founded with his colleague, Bill Tuxworth, the country’s first Human Motor Performance Laboratory, and a number of national squads started to beat a path to his door for (free) testing and advice. He also found time to help train Jonah Barrington to some of his six world squash titles. He was soon appointed to the British Olympic Association Medical Committee, and helped to take 90 competitors for altitude training at St Moritz before the 1972 Olympics (he would subsequently attend four more Olympic Games in an official capacity with the BOA). The next 15 years witnessed a sea change as laboratories, university courses and research in sport sciences proliferated, and coaching became more professional. Sharp’s central role in this transformation was recognised in 1987, when the BOA invited him to establish the British Olympic Medical Centre at Northwick Park Hospital. During his five-year tenure, he helped to test and inform the training of notable champions including Steve Redgrave, Matthew Pinsent, Steve Ovett and Audley Harrison, and also found time to advise Glasgow Rangers FC under Graeme Souness. In 1992, he left the BOMC to become the first Chair of Sport Sciences at the University of Limerick, and remained immensely proud of his Fellowship of the International Equine Institute in Limerick where he continued to lecture for many years. He returned to England in 1994 to become Professor of Sport Sciences at West London Institute of Higher Education (later Brunel University), a position he retained as Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2005. During his professional life, he published extensively and authored several books on Walking Physiology (1985), Exercise Physiology of Children (1991), Equine Physiology (1998), Physiology of Dance (1999) and Aging and Fitness (2002).

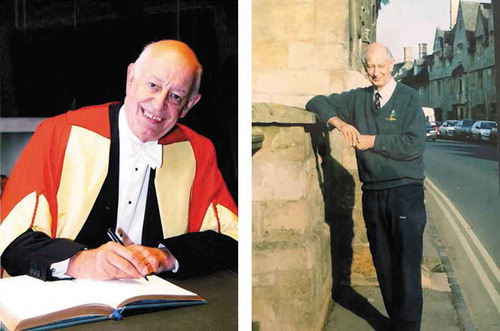

Craig Sharp collected numerous awards, including the International Olympic Committee’s prestigious “Sport and Wellbeing” award, the Sir Roger Bannister Medal from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine, the Dunky Wright Memorial Medal for services to Scottish Athletics, a British Gymnastics Special Services award, Fellowships of the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences, Institute of Biology, and Physical Education Association (UK), and Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Exeter and Stirling. His proudest moment came in 2005 when he was awarded an Honorary DSc by the University of Glasgow to add to his Honorary DSc from the University of East London. He was undoubtedly one of the opinion leaders in the field and not for nothing was he dubbed “The Founder of UK Sport Sciences”.

Most observers would consider these achievements sufficient for any man, but Craig Sharp was a man of many parts. He was an accomplished musician, playing the classical guitar to a high standard. Once, following a talk at the Royal Institution in London, he was returning home via the Underground when a busker he was approaching suddenly stopped in the middle of a classical piece. The busker explained to an enquiring Sharp that he did not know the remainder of the composition, to which Sharp replied that he did, and promptly sat down to complete the music. Appreciative passers-by tossed in a few coins, including some eminent but bemused professors to whom Sharp had been speaking just minutes before! He retained a lifelong interest in Jazz, presenting the weekly “Mood for Night Owls” jazz programme for Kenya Radio, and was also resident Poetry Critic on Radio Clyde in the 70’s. A friend to many Scottish poets, he once drove 1200 miles in 22 hours to attend the funeral of Sorley MacLean in the Kirk at Portree on Skye. He was also an accomplished Burns scholar, and owned several original manuscripts. It is entirely fitting of this polymath that, while one of his earliest publications was entitled “Inhibition of immunological expulsion of helminths by reserpine” (Nature, 1968), his last was “Born at the Ploughtail-Ploughing and Robert Burns” (Burns Chronicle, 2014). Few combined art and science as seamlessly, nor garnered so many friends from both spheres.

Always a welcoming, generous and modest man, Norman Churchill (his mother was a distant relation to Winston) Craig Sharp was born on 6 November 1933 on the Great Western Road, Glasgow to Norman and Sheila. He was educated at Kilcreggan and Kent Road Primary Schools, and then Morrison’s Academy, Crieff. He died on March 21st, 2018, following a stroke.

He will be greatly missed by family and friends, including many from the world of Sport Sciences in the UK and beyond.