ABSTRACT

Swing bowling can influence the outcome of cricket matches, but technique characteristics and coaching practices have not been investigated at an elite level. This study aimed to provide insight into the perceived technique parameters, coaching practices and variables contributing to conventional new ball swing bowling in elite cricket. Six Australian Test match fast bowlers and six Australian international and national-level coaches were interviewed. A reflexive thematic analysis of interview transcripts generated themes associated with swing bowling. Most bowlers reported their technique allows them to naturally create either inswing or outswing, with technique variations used to create swing in the opposite direction. To increase delivery effectiveness, bowlers and coaches recommended pitching the ball closer to the batter in length and varying release positions along the crease. Coaches recommended making individualised technique adjustments, but suggested all bowlers could benefit from maintaining balance and forward momentum to create a consistent release position in repeated deliveries. This study could inform training strategies to alter techniques and improve swing bowling performance. Future research should investigate the physical qualities of fast bowlers and use biomechanical analyses to provide a deeper understanding of swing bowling.

Introduction

Cricket is played between two teams and is a contest between bat and ball, with the aim to score more runs than the opposition. While many formats of cricket are played, Test matches can last up to five days in duration with each team allowed two innings to accumulate runs. Due to the match duration, there is less time pressure, with batters less inclined to take risks to score and therefore, more emphasis is placed on the bowler’s ability to dismiss the opposition batter. As such, winning Test matches has been reported to be partly due to attacking bowling styles (Lohawala & Rahman, Citation2018) and reduced average opposition runs per wicket (Brooks et al., Citation2002).

Bowlers can restrict run scoring and claim wickets of opposition batters by swinging the ball, a tactic used to make the ball deviate horizontally as it travels through the air before bouncing on the wicket. Sarpeshkar et al (Citation2017) demonstrated this by examining the movement patterns of batters facing straight and swinging deliveries. In comparison to straight deliveries, swinging deliveries delayed the initiation of the front-foot stride (stepping the lead foot towards the ball) and bat backswing and downswing as batters must wait for updated ball flight information to anticipate the arrival location before initiating their movements (Sarpeshkar et al., Citation2017). Subsequently, the authors reported that this delayed and reduced the quality of bat and ball contact (Sarpeshkar et al., Citation2017). In matches, this can lead to increased dismissal and reduced scoring rates of batters (S. Mehta et al., Citation2022). To create swing, bowlers use a technique that controls how the ball travels through the air (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2021), where imparting varying speeds, seam positions and spin on the ball can create ideal aerodynamic conditions surrounding the ball to cause swing (Bentley et al., Citation1982; R. Mehta & Wood, Citation1980). Two directions of swing can be achieved, outswing, where the ball swings to the offside or away from the batter’s body, and inswing, where the ball swings to the legside or towards the batter’s body.

While numerous studies have investigated fast bowling lumbar injury mechanisms (Burnett et al., Citation1998; Ferdinands et al., Citation2009) and factors contributing to ball release speed (Portus et al., Citation2004; Worthington et al., Citation2013), swing bowling has received little consideration (Lindsay et al., Citation2021). Currently, conventional swing bowling mechanics have only been investigated in sub-elite athletes (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020, Citation2021). For a right-handed bowler, at the point of ball release, the forearm and hand were angled to the left for outswing and to the right for inswing with the wrist flexing (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020). However, there are differences to descriptions provided by elite fast bowlers in a Cricket Australia coaching manual with greater emphasis on ball grip to deliver the ball with varying hand positions (Pyke, Citation2010). Using an angled seam grip (primary seam angled across the index and middle fingers) can allow bowlers to release the ball with their hand orientated straight down the wicket. Researchers have reported differences in arm kinematics between elite and sub-elite athletes in similar overhead movements of cricket spin bowling (Chin et al., Citation2009; W. Spratford et al., Citation2020) and baseball pitching (Fleisig et al., Citation1999). Therefore, it is likely that elite fast bowlers employ different ball grips and arm positions to generate swing (Pyke, Citation2010) when compared to the bowling actions used by sub-elite athletes in previous research (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020, Citation2021) and further investigations are required (Bartlett et al., Citation1996; Lindsay et al., Citation2021). Research into this area has the potential to benefit athletes and coaches by providing scientific evidence to guide training strategies to improve performance.

As different formats of cricket are played throughout the world, elite bowlers must manage their technique to produce swing across different settings. Understanding how elite bowlers maintain or vary technique aspects to produce swing is unknown. Analysing the experiential knowledge of elite bowlers and coaches could identify crucial aspects to help improve swing bowling performance. Similar approaches have been beneficial to understanding technical aspects of sprinting (Waters et al., Citation2019) and cricket batting (Connor et al., Citation2020) techniques. Qualitative interviews have previously been used to provide an in-depth understanding of fast bowling expertise development (Phillips et al., Citation2010), and studies from other sports have used similar methods to gather information about coaching practices (Pocock et al., Citation2020; Vickery & Nichol, Citation2020). The use of interviews can provide insight into the perceptions of how and why athletes and coaches implement strategies for swing bowling (J. Maxwell, Citation2012) to enhance the understanding of elite cricket performance (Greenwood et al., Citation2012).

To develop a thorough understanding of swing bowling, bowlers and coaches must both be interviewed as they offer unique perspectives that are formed by different roles and experiences within cricket. Bowlers provide an individualised perspective on how they might vary their technique to create swing, whereas coaches mentor many athletes throughout their careers and provide knowledge that may be more generalisable to a population of fast bowlers. Therefore, this study aimed to provide insight into perceived key aspects of the bowling action used by bowlers, practices implemented by coaches, and the variables contributing to conventional new ball swing bowling from the perspective of elite fast bowlers and coaches. The results of this study have the potential to provide the foundations for future swing bowling research that uses qualitative or quantitative methods and guide coaching strategies.

Methods

Ontology and epistemology

The authors followed a critical realist ontological (J. A. Maxwell, Citation2012) and post-positivist epistemological (Robson, Citation2002) approach. This ontological approach was used as swing bowling was viewed as a “real” phenomenon based on physics, and not socially constructed or solely a subjective experience. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that swing bowling is challenging to understand, and expert knowledge of how to achieve and manage swing may offer valuable insights (J. A. Maxwell, Citation2012). In this way, there exists some degree of uncertainty in observations, and we cannot know the “reality” of swing with complete certainty. A post-positivist approach was taken as we believe human knowledge is based on conjectures (Lindlof & Taylor, Citation2017). As such, we acknowledge that our background knowledge in the current field of research influenced what was observed (Robson, Citation2002).

Participants

The cohort was composed of two groups: bowlers and coaches. Purposeful sampling was used to recruit individuals who the research team identified as being suitable for this study. Past and present male Australian Test match opening fast bowlers (bowlers who had delivered the first or second over of an innings) were eligible. Six bowlers were asked and agreed to be interviewed. The recruited bowlers had played in a combined 198 Test matches and had claimed a combined 821 Test wickets. Coaches were eligible if they held a Cricket Australia Level 3 coaching accreditation and possessed fast bowling coaching experience at an international (senior Australian team) or national level (senior Australian state teams). Nine male Australian coaches were asked to participate, with six agreeing. The coaches had a combined 27 years of international level experience. Participant characteristics are shown in . Participants are referred to by alphanumeric combinations, for example, B1 and C6 represent Bowler one and Coach six, respectively.

Table 1. Participant characteristics mean ± SD.

Data collection and analysis

Based on the philosophical approach and prior knowledge of the research team, including two members conducting previous swing bowling studies (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020, Citation2021), semi-structured interview guides consisting of open-ended questions were developed (see Appendix). Semi-structured interviews were used to prompt relevant responses and assist the interview process (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2013). During the development of the interview guides, the research team reviewed and refined the content. Additionally, the lead investigator undertook qualitative research training and completed two pilot interviews with an Australian state-level fast bowler and coach to further refine the questions and practice interview technique. Interview guide modifications included adding questions about specific aspects of the bowling action and asking for comparisons to other athletes and coaches to elicit in-depth responses. While the overall structure of the interview was the same for all participants, the order of questions depended on participants’ responses. The interview guide began with questions about playing or coaching experience and then targeted specific factors perceived to be important for swing bowling. Of specific interest was how bowlers produce swing and coaching strategies to improve swing bowling performance. Questions were also asked about different ball types and environmental conditions. The interview ended by allowing the participants to share additional information. Sample questions included:

Can you describe how you produce swing with your bowling action?

From a coaching perspective, can you describe what you believe is important for a bowler to swing the new ball?

How does your approach to bowling/coaching swing change with different colours and brands of balls?

Before data collection, ethics approval was granted from the University of Canberra Human Research Ethics Committee (approval #4646). Individuals were initially contacted to gauge their interest in participating. They were informed of the purpose of the study and given details of their involvement. At the beginning of the interview, participants provided informed consent and were reminded of the interview structure and content. All 12 interviews were conducted by the lead researcher (CL). After rapport building discussions and broad questions to familiarise the participants with the interview theme, they were asked about specific factors perceived to be important for conventional new ball swing bowling. All questions were open-ended with further probing questions to encourage clearer and more expansive responses. All interviews were conducted and recorded using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, California, USA). The mean duration of the interviews was 50 ± 21 minutes for bowlers and 46 ± 7 minutes for coaches.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim with 122 pages of single-spaced text produced for analysis. Following each transcription, the text was compared against the recording and in the case of differences, revisions were made to ensure accuracy (McLellan et al., Citation2003). NVivo 12 (QRS International, Victoria, AUS) was used to analyse all data using Braun and Clarke’s six-step reflexive thematic analysis approach: 1) familiarisation with the data, 2) generating initial codes, 3) generating themes, 4) reviewing themes, 5) defining and naming themes, and 6) writing the report (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). This aligned with the philosophical approach adopted by the researchers as it allowed for examples of swing bowling in training and matches to be identified using the researchers’ subjective experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The analysis was conducted by the lead researcher using an inductive to deductive approach. This meant that open coding was used and upon the creation of a new theme, each transcript was deductively analysed for the same theme (Côté et al., Citation1993). Once codes were developed, they were combined with similar codes into sub-themes (e.g., the codes of pitch the ball up and release point were placed into the sub-theme of line and length). This process was repeated to generate more expansive themes that represented the broadest level of analysis (e.g., the sub-themes of body alignment and bowling arm path were categorised into the theme of bowling action) and allowed for the research aims to be addressed. The data was analysed until saturation was achieved and no new themes were created in two consecutive transcripts.

Trustworthiness was addressed according to the criteria published by (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985): credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was established using recognised research methods (lead researcher qualitative research training, pilot interviews, interview guide modification, peer debriefing (Barriball & While, Citation1994; Braun & Clarke, Citation2013) and reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019)) and prolonged engagement was demonstrated by several members of the research team undertaking scientific research in cricket (R. Crowther, Citation2023; Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2023; Middleton, Citation2011; W. A. Spratford, Citation2015). This allowed for a deep understanding of participants’ perceptions as the investigators had prior experience in the research area. Transferability was addressed through thick descriptions to provide a thorough understanding of participants’ perceptions and improve the applicability of the findings to practice. Dense descriptions of methods and the re-coding of transcripts one month after the initial coding were used to establish dependability. Confirmability was established using peer debriefing sessions throughout the data analysis process. During these sessions, the lead researcher presented their interpretations and findings to another member of the research team (WS) who was not involved in the data collection or analysis and encouraged reflection and alternative interpretations of the data.

Results

Following a reflexive thematic analysis of the data, a total of 29 codes, 11 sub-themes and four themes were created. The themes included bowling action, effective delivery characteristics, coaching practices, and ball and environment variables (see ). Each theme will be discussed as a separate sub-section with sub-themes italicised in-text and key quotations from participants used as exemplar evidence. Factors identified to contribute to swing bowling performance are discussed in detail below and expressed graphically in .

Figure 1. Conceptual model of identified technique aspects and coaching practices that lead to successful inswing and outswing performance.

Table 2. Themes, sub-themes, codes, and participant quotes.

Bowling action

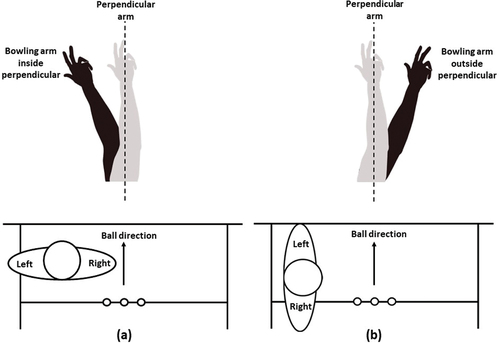

The bowling action theme reported aspects of the delivery stride that allow bowlers to create swing. It was formed by four sub-themes of body alignment, bowling arm path, grips, and ball release as well as 10 codes and 166 quotes from 12 interviews. The participants discussed using different body alignments during the delivery stride. Front-on and side-on bowling actions were reported to promote a bowling arm path that is either inside or outside perpendicular to the ground, respectively (see ). The participants revealed that these positions often result in bowlers having a natural direction of swing:

“I think you’re probably a touch more side-on when you’re bowling outswing to the right-hander um, and you’re probably a little bit more front-on when you’re trying to bowl inswing, it’s just a natural way the arm is going to come through … my arm’s just on the outside of perpendicular … I think if you’re past it on the inside, it’s a lot harder to swing it out … certainly either side of the 12 o’clock is a big indicator of if you can swing in or out”.

Figure 2. Schematics of bowling action classification at back foot contact of delivery stride as viewed from above (images below) and bowling arm path as viewed from behind (images above) for a right-handed bowler. (a) Front-on bowling action leading to bowling arm inside perpendicular and (b) side-on bowling action leading to bowling arm outside perpendicular.

In general, participants reported that having a perpendicular and upright bowling arm at the point of release can assist bowlers to swing the ball in both directions by making subtle changes to other aspects of their technique, such as wrist position. For example:

“ … your bowling arm that travels down the plane of the stumps and then comes back over the top, they’ve got an advantage” (C5) and “I wouldn’t change barely, well I don’t think I did, barely anything to bowl, to, from, from an outswinger to an inswinger. It’d be more just a little bit of change in my wrist and that’s it”. (B1)

For athletes with a bowling arm path on either side of perpendicular, bowlers and coaches suggested adjusting the grip on the ball and making changes to arm and wrist positions, to swing the ball in their non-favoured direction. This is explained by B2 who naturally delivers inswing with a bowling arm path inside perpendicular:

… so even if my wrist, my arm path isn’t perfect my wrist kind of makes up for, well yeah, what my arm path isn’t doing well … for my outswinger I kind of need to fight that a little bit so I hold it with the seam sort of a little bit pointed towards first slip … I probably relax my wrist a little bit and hold it a little bit more open so at release I’m naturally like that, around the ball, at release I can naturally come round it a bit”. (B2)

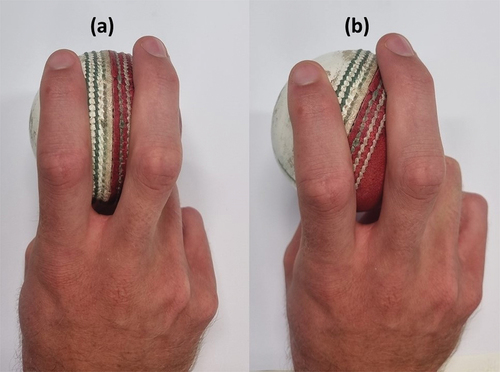

The bowlers reported using different grips (see ) with some using a straight grip (primary seam between the index and middle finger) and others using an angled seam grip (seam angled across the fingers). This is demonstrated by:

“ … so straight on the seam, just the fingers, just ah, sort of either side of the seam” (B3) and “ … I’ve probably got a slightly angled seam”. (B6)

Figure 3. (a) straight seam grip with the primary seam between the index and middle fingers and (b) angled seam grip with the primary seam angled across the index and middle fingers.

These differences were also supported by coaches who suggested bowlers use individualised grips to allow the ball to be released with an angled and upright seam orientation based on their technique:

“ … how I hold the ball, what gives me the best result? So, look I, I think there’s some basics, but I definitely think there are individuals that, that need to do things differently” (C4) and “ … it’s a case of looking how they move through the crease um, to then come up with a grip that is conducive to standing the seam up”. (C5)

When discussing ball release there were contradictions among participants. Some bowlers described having a specific last point of contact with the ball while others said it was hard to determine:

“ … for an outswinger, again, yeah, it’s almost the opposite, I almost imagine my wrist going on the outside of the ball, um, trying to make middle finger the last point that comes off it” (B2) and “ … I couldn’t tell you what, it just felt like it was just ah, it just came out nice”. (B2)

While there was conjecture about how the ball is released from the fingers, participants emphasised maintaining wrist, hand, and finger positions directly behind the ball to produce an upright seam position:

“ … seam upright, pretty old school pointing it to first slip and relying mostly on my action but my wrist as well to get right behind the seam, right behind the ball to keep that seam nice and upright” (B3) and “ … a lot of kids I teach, they’re no chance to get themselves into a position at the crease to get them, to get their fingers behind the ball, and they come down the side of the ball”. (B1)

Effective delivery characteristics

The effective delivery characteristics theme details the perceived key aspects of successful swing bowling following ball release. Three sub-themes were formed: seam position, line and length, and location of swing as well as seven codes and 106 quotes from 12 interviews. To swing the new ball, participants discussed the importance of releasing the ball with the desired seam position. This was described as a slightly angled seam and the maintenance of an upright seam during flight (see ). To maintain an upright seam, imparting backspin on the ball was reported to be an important factor. This is demonstrated by the following quotes:

“I taught myself pretty early that the seam on the ball was pretty important and keeping it as straight as possible with an angle here and there obviously determined which way it went and how much it went”. (B1)

“You need to impart spin on the ball to keep the integrity of that seam all the way down, all the way down the wicket. Ah, and the best analogy I can give you is like one of those spinning tops, like once they slow down, they start to wobble and that’s exactly what the cricket ball does”. (C5)

Figure 4. (a) Angled and upright seam and (b) angled and non-upright seam as viewed from behind (left images) and above (right images).

Participants perceived the line and length of deliveries to be important for successful swing bowling. Pitching deliveries on a good-to-full length and varying the release position along the crease (see ) were revealed as strategies to increase the effectiveness of deliveries:

“ … ideally you’re hitting the top third of the stumps … if it’s swinging a lot, I’d be encouraging bowlers to bowl mid crease so we get, so you’ve got a little bit of angle towards leg stump or middle stump. If you’re swinging the ball away, bowling mid-crease is a better option than getting closer to the stumps”. (C6)

Figure 5. Overhead schematic of different release points of swinging deliveries. The solid line represents a delivery with a release point close to the stumps. This delivery is initially projected towards the stumps but swings and pitches outside the line of the stumps. The dashed line represents a wider release point where the delivery is also projected towards the stumps but pitches in line with the stumps.

Finally, the location of swing emerged as another important factor that contributes to successful swing bowling performance. Bowlers explained they aim to create late swing, a type of swing where the ball laterally deviates later in flight when it is closer to the batter. The bowlers believe that this provides batters with less time to make decisions about how to play deliveries. For example:

“You’re giving too much away aren’t you when it’s swinging from the hand” (B4) and “ … it will swing late, and the batter can’t make a decision until the last minute”. (B2)

Coaching practices

The coaching practices theme reported coaching strategies to improve swing bowling and technique aspects believed to be important for consistent and successful performance. It was formed by two sub-themes of coaching process and fundamental movement patterns as well as six codes and 63 quotes from six coach interviews. As part of the coaching process, coaches highlighted the need to understand the requirements of swing bowling to allow them to make appropriate technique adjustments. Additionally, coaches reported the need to first observe the bowler’s action and then make changes that are individualised to each player:

“ … as a player, if it just happens then so be it, you might not need to know the whole mechanics of everything that goes into it, but I think as a coach if you are teaching it, you definitely need to know why a ball swings and how you get it to do it”. (C1)

“I mean there’s, and the biggest thing is that each bowler’s different so you can’t try and coach them all the same, you just try and pick out how they deliver the ball and how do we tweak their action to make them more efficient to get the ball out of the hand the best they possibly can”. (C3)

While the bowlers primarily discussed components of their delivery stride required to swing the ball, coaches believe other fundamental movement patterns underpin not only successful swing bowling performance, but the ability to perform well at an elite level. Coaches highlighted the need for bowlers to maintain balance and forward momentum as well as have a repeatable action to produce swing consistently and successfully. This is demonstrated by the following quotes:

“I would coach the fundamentals straight up and the fundamentals mean that you know, you come in and you have a good action first … then I would move to being able to at least being able to deliver the ball with the control of the seam so you knew where the seam was coming out and then obviously trying to get some consistency around where they put the ball”. (C1)

“I think by putting them in a more balanced position, if you think of your trunk as your sort of pillar, you want that pillar upright. It basically allows more energy to go into the ball, behind the ball … importantly you’re working with your arms more down the plane of the stumps … if you’ve got things moving across the plane of the stumps, generally, you’re going to have to redirect them and you contort your body to do it, you wash off potential speed, there’s knock-on effects … look at someone like a James Anderson who’s probably the number one swing bowler in the world for a long period of time. Um, you know, his action is very natural to him, it’s, it’s very different, no one else bowls like him but at the critical moments he’s in a very, very good position”. (C5)

Ball and environment variables

The ball and environmental variables theme reflected how participants perceived different balls and environmental conditions to influence swing bowling. It was formed by two sub-themes of different balls and conditions as well as six codes and 85 quotes from 12 interviews. When asked how different coloured balls influence swing, participants reported that bowlers should not alter their technique. However, they revealed surface coatings deteriorate at different rates, influencing the duration of swing:

“ … the red one seems to um, be, have a better finish and a lasting finish so it tends to swing a little bit more … a white one seems to swing for a short period of time so you need to take advantage of that … the pink one seems to have a more of a white finish and a white coating. That one seems to swing um, more when it’s um, newer and earlier and runs out of puff after a while”. (C1)

Similarly, it was reported that bowlers don’t alter their technique when using Dukes balls. Instead, participants spoke about how the duration and amount of swing differs in comparison to Kookaburra balls and should be considered by bowlers. Participants suggested changing the release point of deliveries (see ) to account for the increased amounts of swing when using the Dukes ball. This is demonstrated by the following quote:

“How you swing the ball doesn’t change too much, it’s more the different ball allows you to either do it for longer or gives you more sideways movement … the ball’s swinging well because it’s a Dukes ball for example. So I might have to give a little bit more angle in my run-up so I can start the ball a little bit more angled because it is going a fair way whereas a Kooka [Kookaburra] mightn’t go much but just enough so I can actually, I can run in a little bit straighter, start the ball straighter”. (C5)

When considering how environmental conditions influence swing bowling, there was significant conjecture among the participants. While all participants believed that environmental conditions affect swing bowling, when asked to describe ideal weather conditions, there were significant differences in the examples provided:

“ … as soon as the cloud comes over, the ball swings” (C3), “I suppose humidity” (C2) and “I’ve seen days where it’s bright blue skies and all the rest of it and the ball has swung”. (C5)

Small variations in the condition of new balls, caused by the manufacturing process, was also considered to be a factor that influences swing:

“Going back to the game we just played, we had a first innings, we bowled first, early, didn’t swing a ball basically and then we came out in the second innings on day 3 in the afternoon and it swung, conditions exactly the same as day one so it’s maybe the ball as well”. (B3)

Discussion

This study aimed to provide insight into perceived key aspects of the bowling action used by bowlers, practices implemented by coaches, and the variables contributing to conventional new ball swing bowling from the perspective of elite Australian fast bowlers and coaches. A reflexive thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews identified that many bowlers naturally deliver one direction of swing due to using front-on or side-on techniques. Bowlers keep their fingers in the same plane as the seam at release to ensure an upright seam position. Regardless of the technique used by bowlers to generate swing, when they create swing, varying the line and length of deliveries increases the difficulty for batters to accurately intercept the ball. Coaches believe that repeatable movement patterns are crucial for bowlers to create swing successfully and consistently. Finally, environmental and ball variables were perceived to influence swing bowling.

Generally, bowlers reported being naturally pre-disposed to delivering either inswing or outswing according to their body position during the delivery stride of their bowling action. Bowlers with side-on and front-on techniques often deliver outswing and inswing, respectively. This is likely caused by front-on techniques leading to increased contralateral thorax flexion and the bowling arm being inside perpendicular (see ), with the opposite occurring for bowlers with side-on techniques (Elliott & Foster, Citation1984). Bowling arm position was not investigated in previous swing bowling research (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020), but appears to be a strategy that bowlers can employ to create swing, and should be considered in future research. When using a straight seam grip (see ), releasing the ball with an arm position on either side of perpendicular creates an angled seam as the hand and fingers are orientated in the direction of swing, influencing the axis of rotation imparted on the ball (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2021). To swing the ball in their non-favoured direction, bowlers with a non-perpendicular arm may be required to change large aspects of their technique such as body alignment or arm position (Lindsay et al., Citation2021), providing valuable pre-flight information for the batter to use to intercept the delivery (Weissensteiner et al., Citation2008). A perpendicular bowling arm may allow bowlers to create both directions of swing by making subtle adjustments to their grip or hand position and is less likely to be detected by the batter.

Ball grip and release were described as important aspects when attempting to generate swing. As each bowler has an individualised technique (Glazier & Wheat, Citation2014), the coaches believed athletes should also use individualised grips to release the ball with an angled seam required for swing bowling. This is consistent with anecdotal reports of elite fast bowlers, found in a Cricket Australia coaching manual (Pyke, Citation2010), who used both straight and angled seam grips to generate the desired ball release orientation. While different grips can be used, the participants emphasised that the wrist, hand, and fingers should be positioned on the posterior surface of the ball so that any rotation of the ball in the hand (angled seam grip) allows bowlers to keep their fingers in line with the seam at release. Maintaining this position creates an upright seam to maximise swing (Barton, Citation1982). This is supported by baseball studies that compared fastball and slider pitches (Stevenson, Citation1985; Whiteside et al., Citation2016). When throwing fastballs, pitchers maintain a hand position on the posterior surface of the ball to impart backspin with an axis of rotation that is orthogonal to the alignment of the wrist, hand, and fingers. When throwing sliders, the hand is turned to the lateral aspect of the ball to impart sidespin. Therefore, bowlers should avoid releasing the ball with their fingers on one side of the seam as it can impart a small amount of sidespin, which promotes a less stable seam, reducing the swing of deliveries (Barton, Citation1982; R. D. Mehta, Citation1985).

Bowlers must release the ball in a way that the seam remains stable and upright (see ) throughout flight to maximise swing. This is achieved when the seam appears in a fixed vertical position and maintains constant airflow asymmetry surrounding the ball to cause swing (Barton, Citation1982; Bentley et al., Citation1982; Scobie et al., Citation2020). To maintain seam stability, the participants suggested imparting backspin on the ball at release, which corresponds with existing literature (Barton, Citation1982; Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020; R. D. Mehta, Citation1985). Bowlers can impart backspin by using wrist flexion through the point of release to drag the index and middle finger down the back of the ball (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2021). Importantly, bowlers should keep their fingers in line with the seam to ensure it is released upright. While it has been established that backspin maintains seam stability, it is unknown what influence angular velocity (ball rotation) has on the ball’s trajectory. Researchers have reported that ball rotation affects airflow surrounding the ball, and subsequently, influences swing, but they suggest the optimal angular velocity varies for different release speeds (Barton, Citation1982; Bentley et al., Citation1982). Further research is required to investigate this aspect of swing bowling.

The participants suggested strategies that bowlers can employ to increase the effectiveness of swinging deliveries. Bowlers should pitch the ball on a good-to-full length (approximately seven to three metres from the batter’s stumps (Justham et al., Citation2010)) and create late swing where the ball deviates more as it gets closer to the batter. By pitching the ball closer in length to the batter, the ball is given a longer flight time to swing, is more likely to hit the stumps, and encourages batters to step forward and play front-foot shots (Justham et al., Citation2010). By creating late swing, batters have less time to make correct decisions about what shot to play and consequently, late swing is considered more difficult to face than early swing (Club, Citation1952). Within scientific literature, late swing has been suggested to be caused by the ball reaching optimal characteristics late in flight, such as a decrease in speed (Barton, Citation1982; Scobie et al., Citation2020). However, there are currently no in situ studies that have investigated late swing and further research is required (Lindsay & Spratford, Citation2020).

Varying the release point of deliveries (see ) was also suggested to increase the difficulty of accurate interception. For example, outswing deliveries can be released from wider along the crease (further from the stumps) so that any swing causes the ball to pitch close to or in line with the stumps, forcing the batter to attempt to hit the ball. Releasing the ball from closer to the stumps when delivering inswing can also be used for the same reasons. Despite these suggestions, previous research suggests that deliveries released from close to the stumps may be more difficult for batters to accurately intercept (Welchman et al., Citation2004). Welchman et al (Citation2004) reported that performers can misperceive the approach angle of trajectories when they travel along the mid-sagittal plane. With batters in cricket adopting side-on stances with their head turned to face the bowler, deliveries released from close to the stumps and projected towards the batter’s body will travel along the mid-sagittal plane. If these deliveries then swing away from the batter’s body, it could be perceived as late swing if the early flight path was not accurately tracked. Varying the release point provides another way to alter the delivery trajectory, reduce predictability, and increase the difficulty for batters to accurately intercept the ball.

Coaching practices can be implemented to improve swing bowling performance. The coaches believed it is important to understand what causes a ball to swing to make appropriate technique adjustments. As each athlete has an individualised bowling action (Glazier & Wheat, Citation2014), technique modifications should also be individualised. Coaches should work with athletes to ensure their technique allows them to release the ball with an angled and upright seam orientation. Additionally, components of each bowler’s technique should be coached to ensure swing can be created consistently and successfully. Coaches suggested maintenance of balanced positions throughout the bowling action to ensure forward momentum towards the target line is important. This is similar to previous research revealing that bowlers and coaches believe “technique fundamentals” are required for successful fast bowling performance (Phillips et al., Citation2014). Having stable technique aspects, with little variation, allows athletes to complete their bowling actions in a consistent and repeatable way (Gray, Citation2021). This is what the coaches were referring to as “fundamentals”, however, there is likely to be large amounts of functional variability within each bowler. This allows athletes to adjust their technique to adapt to variables that are present in a typical performance environment such as ball condition, fatigue levels, and environmental conditions to produce and maintain swing. Combining the stable bowling action components of maintaining balanced positions and forward momentum with individualised technique adjustments can assist athletes to release the ball with an angled and upright seam orientation for swing bowling.

The colour and brand of ball used varies with the format and location of matches and can influence swing bowling. While all balls must conform to the International Cricket Council (ICC) Laws of Cricket (males: 155.9–163.0 grams and 22.4–22.9 centimetres in circumference, females: 140.0–151.0 grams and 21.0–22.5 centimetres in circumference), the manufacturing process causes minor variations in the mass, size and surface of balls (Bartlett et al., Citation1996; Deshpande et al., Citation2018; Marylebone Cricket Club. (Citation2022)). These factors influence how air flows around balls (R. Mehta & Wood, Citation1980) and is likely why the participants believed that some new cricket balls swing more than others. Additionally, participants indicated that different coloured balls swing for varying durations due to the durability of the lacquer. Red balls are produced using dye and lacquer and are said to swing for a greater number of overs compared to white and pink balls that have paint applied to the surface that easily deteriorates. The two most widely used brands are Kookaburra and Dukes, with Dukes balls reported to have a more pronounced primary seam, a smaller secondary seam and a more durable lacquer (Rundell, Citation2009; Scobie et al., Citation2020). Researchers have reported that these factors allow Dukes balls to swing at higher speeds, to a greater magnitude, and for more deliveries when compared to Kookaburra balls (Scobie et al., Citation2020), corresponding with the findings of this study. Altering the release point (see ) when using Dukes balls can account for a greater magnitude of swing. The colour (red with a lacquer finish, and white and pink with a paint finish) and brand of ball used may influence both the magnitude and duration of swing that can be achieved. Bowlers and coaches should consider this when implementing match tactics.

Discussions with the participants revealed significant conjecture about how environmental conditions are perceived to influence swing bowling. Many participants provided different examples of what they perceived to be ideal environmental conditions for swing bowling, with most discussions focusing on humidity. This is consistent with published research that has primarily investigated the effects of humidity with some authors reporting an influence and others finding no effects (James et al., Citation2012; R. D. Mehta, Citation1985; Scobie et al., Citation2020). A recent study reported that humidity does not influence swing bowling and investigated the effects of air micro-turbulence that is present above the ground on hot and sunny days (Scobie et al., Citation2020). These conditions interrupt the airflow surrounding the ball, and therefore, cloud cover may be optimal for swing bowling (James et al., Citation2012). Further research is required to investigate how environmental conditions affect the swing of cricket balls.

This study offers future research avenues; however, it is not without limitations. This study only recruited Australian bowlers and coaches who are most familiar with the Kookaburra ball. Future studies could utilise individuals more familiar with Dukes cricket balls such as those who play and coach in England, to provide an understanding of the technique required to create swing that may oppose that of an Australian perspective. Only males were recruited and the perceptions of female bowlers may differ with researchers reporting significant differences between elite male and female fast bowling actions (Felton et al., Citation2019). This research described experiences and perceptions of participants, which do not always match reality (R. H. Crowther et al., Citation2021) and future studies should use quantitative methods, such as biomechanical analyses, to investigate elite bowlers delivering swing. This would provide a more robust understanding of what occurs when bowlers create swing and confirm the accuracy of participants’ perceptions. Following this, further studies should be conducted to develop and investigate training interventions to improve this aspect of fast bowling performance. Additionally, this study did not investigate the physical qualities (strength, joint range of motion, anthropometry, etc.) of bowlers and correlations have been demonstrated with technique, ball release speed and accuracy of fast bowling (Feros et al., Citation2019). This is an important factor of swing bowling that requires further investigation. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to investigate conventional new ball swing bowling at an elite level of cricket and provides the foundations for future research using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Conclusion

This study provided an understanding of the perceived requirements and the variables contributing to conventional new ball swing bowling in elite cricket. Semi-structured interviews of elite fast bowlers and coaches revealed most bowlers naturally create either inswing or outswing due to the position of their body throughout their delivery stride. Delivering the ball with a perpendicular bowling arm can allow bowlers to make subtle adjustments to their grip and wrist position to manipulate the seam angle and create swing in both directions. While bowlers use individualised techniques, maintaining wrist, hand, and finger positions on the posterior surface of the ball in line with the seam will create an upright seam and impart backspin to maintain this orientation. Bowlers should aim to pitch the ball on a good-to-full length and vary the release point to increase the effectiveness of deliveries. From a coaching perspective, bowling action modifications should be individualised, but maintaining balance and forward momentum can be coached to improve technique repeatability and performance. Environmental conditions were perceived to influence swing bowling, but the effect of various weather conditions remains unclear. The findings of this research could guide future studies and assist in the development of training strategies to improve swing bowling performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barriball, K. L., & While, A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing-Institutional Subscription, 19(2), 328–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01088.x

- Bartlett, R., Stockill, N., Elliott, B., & Burnett, A. (1996). The biomechanics of fast bowling in men’s cricket: A review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 14(5), 403–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419608727727

- Barton, N. (1982). On the swing of a cricket ball in flight. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 379(1776), 109–131.

- Bentley, K., Varty, P., Proudlove, M., & Mehta, R. (1982). An experimental study of cricket ball swing. Imperial College Aero Technical Note, 82–106.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brooks, R., Faff, R., & Sokulsky, D. (2002). An ordered response model of test cricket performance. Applied Economics, 34(18), 2353–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840210148085

- Burnett, A., Barrett, C., Marshall, R., Elliott, B., & Day, R. (1998). Three-dimensional measurement of lumbar spine kinematics for fast bowlers in cricket. Clinical Biomechanics, 13(8), 574–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(98)00026-6

- Chin, A., Elliott, B., Alderson, J., Lloyd, D., & Foster, D. (2009). The off-break and “doosra”: Kinematic variations of elite and sub-elite bowlers in creating ball spin in cricket bowling. Sports Biomechanics, 8(3), 187–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763140903229476

- Club, M. C. (1952). The MCC cricket coaching book: Published officially for the MCC by the. Naldrett Press.

- Connor, J. D., Renshaw, I., Farrow, D., & Wood, G. (2020). Defining cricket batting expertise from the perspective of elite coaches. Public Library of Science ONE, 15(6), e0234802. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234802

- Côté, J., Salmela, J. H., Baria, A., & Russell, S. J. (1993). Organizing and interpreting unstructured qualitative data. The Sport Psychologist, 7(2), 127–37. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.7.2.127

- Crowther, R. (2023). Ecological dynamics of spin bowling in cricket: Adapting to environmental constraints. Queensland University of Technology.

- Crowther, R. H., Gorman, A. D., Renshaw, I., Spratford, W. A., & Sayers, M. G. (2021). Exploration evoked by the environment is balanced by the need to perform in cricket spin bowling. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 57, 102036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102036

- Deshpande, R., Shakya, R., & Mittal, S. (2018). The role of the seam in the swing of a cricket ball. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 851, 50–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2018.474

- Elliott, B., & Foster, D. (1984). A biomechanical analysis of the front-on and side-on fast bowling techniques. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 10(2), 83–94.

- Felton, P., Lister, S., Worthington, P. J., & King, M. (2019). Comparison of biomechanical characteristics between male and female elite fast bowlers. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(6), 665–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1522700

- Ferdinands, R., Kersting, U., & Marshall, R. (2009). Three-dimensional lumbar segment kinetics of fast bowling in cricket. Journal of Biomechanics, 42(11), 1616–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.035

- Feros, S. A., Young, W. B., & O’Brien, B. J. (2019). Relationship between selected physical qualities, bowling kinematics, and pace bowling skill in club-standard cricketers. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 33(10), 2812–25. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002587

- Fleisig, G. S., Barrentine, S. W., Zheng, N., Escamilla, R. F., & Andrews, J. R. (1999). Kinematic and kinetic comparison of baseball pitching among various levels of development. Journal of Biomechanics, 32(12), 1371–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00127-X

- Glazier, P. S., & Wheat, J. S. (2014). An integrated approach to the biomechanics and motor control of cricket fast bowling techniques. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0098-x

- Gray, R. (2021). How we learn to move: A revolution in the way we coach & practice sports skills. Perception Action Consulting & Education LLC.

- Greenwood, D., Davids, K., & Renshaw, I. (2012). How elite coaches’ experiential knowledge might enhance empirical research on sport performance. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 7(2), 411–22. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.7.2.411

- James, D., MacDonald, D., & Hart, J. (2012). The effect of atmospheric conditions on the swing of a cricket ball. Procedia Engineering, 34, 188–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.04.033

- Justham, L., Cork, A., & West, A. (2010). Comparative study of the performances during match play of an elite-level spin bowler and an elite-level pace bowler in cricket. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering & Technology, 224(4), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1243/17543371JSET77

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. sage.

- Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2017). Qualitative communication research methods. Sage publications.

- Lindsay, C., Clark, B., Middleton, K., Crowther, R., & Spratford, W. (2021). How do athletes cause ball flight path deviation in high-performance interceptive ball sports? A systematic review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 17(3), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211047360

- Lindsay, C., Crowther, R., Middleton Dr, K., Clark, B., Warmenhoven, J., & Spratford, W. (2023). Movement variability in elbow and wrist kinematics of new ball outswing bowling in cricket fast bowlers. ISBS Proceedings Archive, 41(1), 75.

- Lindsay, C., & Spratford, W. (2020). Bowling action and ball flight kinematics of conventional swing bowling in pathway and high-performance bowlers. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1754717

- Lindsay, C., & Spratford, W. (2021). A kinematic comparison of conventional inswing and outswing bowling in cricket. ISBS Proceedings Archive, 39(1), 33.

- Lohawala, N., & Rahman, M. (2018). Are strategies for success different in test cricket and one-day internationals? Evidence from England-Australia rivalry. Journal of Sports Analytics, 4(3), 175–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/JSA-180191

- Marylebone Cricket Club. (2022) The laws of cricket 2017 code (3rd Edition - 2022).

- Maxwell, J. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage Publications.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). A realist approach for qualitative research. Sage.

- McLellan, E., MacQueen, K., & Neidig, J. (2003). Beyond the qualitative interview: Data preparation and transcription. Field Methods, 15(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239573

- Mehta, R. D. (1985). Aerodynamics of sports balls. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 17(1), 151–89. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.17.010185.001055

- Mehta, S., Phatak, A., Memmert, D., Kerruish, S., & Jamil, M. (2022). Seam or swing? Identifying the most effective type of bowling variation for fast bowlers in men’s international 50-over cricket. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(14), 1587–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2022.2094140

- Mehta, R., & Wood, D. (1980). Aerodynamics of the cricket ball. New Scientist, 87(1213), 442–447.

- Middleton, K. J. (2011). Mechanical strategies for the development of ball release velocity in cricket fast bowling: The interaction, variation and simulation of execution and outcome parameters. University of Western Australia.

- Phillips, E., Davids, K., Renshaw, I., & Portus, M. (2010). The development of fast bowling experts in Australian cricket. Talent Development & Excellence, 2(2), 137–148.

- Phillips, E., Davids, K., Renshaw, I., & Portus, M. (2014). Acquisition of expertise in cricket fast bowling: Perceptions of expert players and coaches. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.005

- Pocock, C., Bezodis, N. E., Davids, K., Wadey, R., & North, J. S. (2020). Understanding key constraints and practice design in Rugby Union place kicking: Experiential knowledge of professional kickers and experienced coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 15(5–6), 631–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954120943073

- Portus, M., Mason, B., Elliott, B., Pfitzner, M., & Done, R. (2004). Cricket: Technique factors related to ball release speed and trunk injuries in high performance cricket fast bowlers. Sports Biomechanics, 3(2), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763140408522845

- Pyke, F. (2010). Cutting edge cricket: Human kinetics.

- Robson, C. (2002). Real world research: A resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Rundell, M. (2009). Wisden dictionary of cricket: A&C black.

- Sarpeshkar, V., Mann, D., Spratford, W., & Abernethy, B. (2017). The influence of ball-swing on the timing and coordination of a natural interceptive task. Human Movement Science, 54, 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2017.04.003

- Scobie, J., Shelley, W., Jackson, R., Hughes, S., & Lock, G. (2020). Practical perspective of cricket ball swing. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering & Technology, 234(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754337119872874

- Sparkes, A., & Smith, B. (2013). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Spratford, W. A. (2015). Biomechanical, anthropometric, and isokinetic strength characteristics of elite finger and wrist-spin cricket bowlers: A developmental and performance perspective. University of Western Australia.

- Spratford, W., Elliott, B., Portus, M., Brown, N., & Alderson, J. (2020). The influence of upper-body mechanics, anthropometry and isokinetic strength on performance in wrist-spin cricket bowling. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(3), 280–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1696265

- Stevenson, J. (1985). Finger release sequence for fastball and curveball pitches. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 10(1), 21–25.

- Vickery, W., & Nichol, A. (2020). What actually happens during a practice session? A coach’s perspective on developing and delivering practice. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(24), 2765–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1799735

- Waters, A., Phillips, E., Panchuk, D., & Dawson, A. (2019). Coach and biomechanist experiential knowledge of maximum velocity sprinting technique. International Sport Coaching Journal, 6(2), 172–86. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2018-0009

- Weissensteiner, J., Abernethy, B., Farrow, D., & Müller, S. (2008). The development of anticipation: A cross-sectional examination of the practice experiences contributing to skill in cricket batting. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30(6), 663–84. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.6.663

- Welchman, A. E., Tuck, V. L., & Harris, J. M. (2004). Human observers are biased in judging the angular approach of a projectile. Vision Research, 44(17), 2027–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2004.03.014

- Whiteside, D., McGinnis, R., Deneweth, J., Zernicke, R., & Goulet, G. (2016). Ball flight kinematics, release variability and in‐season performance in elite baseball pitching. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 26(3), 256–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12443

- Worthington, P., King, M., & Ranson, C. (2013). Relationships between fast bowling technique and ball release speed in cricket. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 29(1), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.29.1.78

Appendix

1 – Bowler interview guide

Can you describe your playing experience as a bowler?

Can you describe your new ball swing bowling experience?

When bowling to a batter of the same handedness are/were you stronger in your ability to bowl either inswing or outswing? What made it easier to bowl one more than the other?

Can you describe how you produce swing with your bowling action?

From your perspective, can you describe what you think is important for new ball swing bowling? Why are these important?

What things have you seen or heard other people do to achieve swing that you do not do yourself? Why don’t you do these things?

How does/did your approach to bowling swing change with different colours and brands of balls?

From your perspective, how do you think environmental conditions influence swing bowling?

Do you have any other information you would like to add?

Run-up & pre-delivery stride

In comparison to a standard delivery, did/do you alter your run-up and pre-delivery stride when bowling swing? If so, can you describe how and what you are/were trying to achieve?

Delivery stride & release

Grip

Can you describe how you grip the ball? Why?

Wrist

Can you describe how you use your wrist? Why?

Bowling Arm

Can you describe how you use your bowling arm? Why?

Thorax

Can you describe your upper body alignment? Why?

Line/Use of Crease

Can you describe your release points and what lines you aim to use? Why?

Release

Can you describe the things you do at the point of release?

Can you describe your release speed? Do you alter it from a standard delivery? If yes, why?

Follow through

Can you describe your follow through? What are you trying to achieve?

Appendix 2

– Coach interview guide

Can you describe your coaching experience?

Can you describe your experience in coaching new ball swing bowling?

Can you describe how you coach a bowler to achieve inswing and outswing?

From a coaching perspective, can you describe what you believe is important for a bowler to swing the new ball?

From a coaching perspective, do you find it harder to coach a bowler to deliver inswing or outswing? What makes it harder than the other?

What things would you tell a developing bowler to focus on when learning to produce swing?

What things have you seen or heard other coaches do when coaching swing that you do not do yourself? Why do you not do these things?

How does your approach to coaching swing change with different colours and brands of balls?

From your perspective, how do you think environmental conditions influence swing bowling?

Do you have any other information you would like to add?

Run-up & pre-delivery stride

In comparison to a standard delivery, do you coach bowlers to alter their run-up and pre-delivery stride? If so, can you describe how and what you want the bowlers to achieve?

Delivery stride & release

Grip

Can you describe how would you coach a bowler to grip the ball? Why?

Wrist

Can you describe how you coach a bowler to use their wrist? Why?

Bowling Arm

Can you describe how you coach a bowler to use their bowling arm? Why?

Thorax

Can you describe how would you coach a bowler to position their body? Why?

Line/Use of Crease

Can you describe how you would coach a bowler in relation to release points and lines to deliver the ball? Why?

Release

Can you describe how you coach the bowlers to release the ball? Why?

Do you coach bowlers to change their release speed? If yes, why?

Follow through

Can you describe how you coach a bowler to complete their follow through? What is the purpose of this?