ABSTRACT

This paper reports on key findings from a mixed method study analysing how teachers in secondary schools (students aged 11–19) in London and South East England view and experience pastoral care provided to students with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs. In England there is statistical evidence which shows schools are increasingly spending funding on support staff rather than teaching staff. The role of Pastoral Support Staff (PSS) who work with students with SEMH in some secondary schools is one such group of support staff. To date there has been limited research into how teachers perceive these changes and the effects on their role and responsibilities. The views of fifty-one respondents were gathered using an online semi-structured survey, followed by semi-structured interviews with six qualified teachers. Using a figured worlds conceptual framework, teachers’ perceptions of the use of pastoral support staff and the delivery of pastoral care in their schools, and therefore their worlds, were analysed. The findings were analysed using Hoy’s and Tschannen-Moran’s work on trust in schools exploring the trust dynamic between PSS and teachers. Results show that the teachers who participated in this research felt there was a lack of information sharing between different PSS and teachers and have seen the separation of pastoral care from the role of teacher leading to confusion around their responsibilities.

Introduction

This paper reports on key findings from a small-scale study investigating the views of teachers about the use of support staff in pastoral roles (Pastoral Support Staff (PSS)) in secondary schools in London and the South East of England. It sought to find out what teachers considered pastoral care to involve and whether they felt the role of pastoral support staff was changing their roles and responsibilities and how it might be impacting on the students with social, emotional and mental health needs. It is acknowledged that PSS are given a number of titles and that their roles, responsibilities, and status differ greatly between schools. Indeed, the job title, or similar derivatives are not yet listed on the annual national workforce survey (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2017b). Therefore, for clarity, this study focused on the role and responsibilities of PSS who work with students whose behaviour required additional support in school.

National context

Towards the end of the twentieth century there was acknowledgement at national level that there was a growing need for students to have greater access to social, emotional, and mental health (SEMH) support within secondary schools (Brown, Citation2018). This led to schools and health authorities employing counsellors, mental health, and social workers to work directly with students within the school setting alongside teachers and support staff. Edmund and Price (Citation2009) suggested that such action could blur the different professional positions within schools. Graves and Williams (Citation2017) also warn that with the rising numbers of non-qualified teaching staff in schools, there is a danger that the most vulnerable students with the most severe needs will spend most of their time receiving both academic and pastoral support from non-teachers.

In past decades the role of the teacher in England has had its emphasis on a holistic (academic and pastoral) commitment to students (e.g., Hamblin, Citation1978; McLean Davies et al., Citation2015). However, by the beginning of this century the challenges and increased workload of teachers, were leading to concerning retention issues, and in response to this national changes started to be made to a teacher’s role and responsibilities. For example, in 2003 a National Agreement on Teachers’ Workload (Loeb et al., Citation2005; Luekens, Citation2004) was introduced in England accepting the need for teachers to have more administrative time and support in schools. Interestingly, by 2011 the revised Teacher’s Standards (England) made no reference to ‘care’, perhaps in an attempt to lessen the responsibilities of teachers in this area. This ‘care’ role omission was replicated in 2019 in the English School Inspection Handbook (Ofsted, Citation2019) which did not refer to pastoral or pastoral care at all.

The rise in the employment of support staff

Alongside, and perhaps at least partly due to such changes to teacher workload, the number of full-time teaching assistants (including PSS) being employed by school leaders in secondary schools increased by 282% and the number of full-time support staff increased by 86%, between 2000 and 2017, (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2018a). Interestingly, this 86% increase has been in the deployment of support staff who work outside of the classroom. In comparison, there has been only a five per cent increase in the number of full-time teachers in English secondary schools during the same time period (ibid).

As well as issues relating to teacher retention in recent decades, there has been a growing awareness that secondary schools need to challenge and resolve the ethnic disparity between teachers and the students they teach. Indeed, even in very recent years thirty percent of secondary school students were of minority ethnic heritage (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2018a) compared to only eight per cent of teachers and three per cent of headteachers (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2018b). Such disparity is seen as important as research indicates that adults in schools with similar ethnic backgrounds may act as role models and mentors for students (Egalite et al., Citation2015; Wei, Citation2007), as well as benefiting student academic progress.

Burgess et al. (Citation2012) found schools in more disadvantaged areas tended to have newer and more inexperienced teachers and the average time in post was less than seven years. This is additional evidence which might suggest why some school leaders are employing more support staff including PSS (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2016), because PSS are more likely to live locally to the school and thus could be more likely to stay in a position for a longer period of time than teachers. This would allow PSS to develop more meaningful relationships not just with students, but, also with their families.

PSS training and expertise

Despite this rapid increase in pastoral support staff numbers there are no clear national guidelines or qualifications required specifically for this role prior to a person commencing employment in a school. This means that unlike other support staff, such as Teaching Assistants (TA) and Higher Level Teaching Assistants (HLTA), PSS employed to work with some of the most vulnerable students may not have any or little appropriate or relevant training.

Thus, it is not unreasonable to suggest there could be a risk that students with social, emotional and mental health needs will spend less time with teachers due to the input of Teaching Assistants (TA) or the newer PSS role.

Why employ pastoral support staff?

The importance of positive relationships between teachers and students is significant as it can support the academic growth of students and support their social-emotional, behavioural growth (Cooper, Citation2008; Hajdukova et al., Citation2014; Mihalas et al., Citation2009), as well as better psychological health and wellbeing (Herrero et al., Citation2006; Wentzel, Citation2002). Multiple studies have found students seek positive relationships grounded in mutual respect and a sense of fairness with the adults in schools, with behavioural and attendance issues receiving firm, quick discipline (Cooper et al., Citation2000; Hajdukova et al., Citation2014; Pomeroy, Citation1999; Rudduck et al., Citation1996). Arguably, students with social, emotional and mental health needs (SEMH) require a therapeutic approach with more opportunities to talk and be listened to from their teachers than other students (Hajdukova et al., Citation2014). Such increased pressure on teachers might again indicate why school leaders are turning to employing another group of adults to work with students who require a high level of support in managing their behavioural, social and mental health needs.

A further reason may be because although there are studies of whole school pastoral programmes which have failed to demonstrate positive impact (Humphrey et al., Citation2010; Weare & Nind, Citation2011), Murphy and Holste (Citation2016) assert there is scientific evidence that pastoral care and engagement with it, are of particular significance for students who are from low-income households, are at risk of underachievement, or are from minority groups who lack power or influence (subordinate) within a school community compared to the dominant student group. Drawing on many sources, Murphy and Holste (Citation2016) state that a range of evidence affirms increased pastoral support leads to a decline in all types of misbehaviour, and increased achievement and attainment (Felner et al., Citation2007; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Quint, Citation2006 in Murphy & Holste, Citation2016). Importantly, other research has also shown that strong pastoral care can not only increase student positive involvement, motivation and engagement with school life generally, but also in lessons with their teachers (Bryk, A. S., Lee, v. and Holland, P. B, Citation1993; Freiberg et al., Citation2009). Tucker (Citation2013) and Weare and Nind (Citation2011) go further concluding that targeted specific pastoral interventions can have a positive impact on students at risk of exclusion, enabling the avoidance of the long-term damage an exclusion from education can have on a young person’s future.

The research study

This research study (Rice O’Toole, Citation2020) aimed to deepen understanding of how pastoral care is provided in secondary schools, by highlighting the concerns of some teachers, and recommending structures for the use of pastoral support staff in secondary schools. This article reports on the findings related specifically to whether teachers feel the employment of PSS working with students with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs is changing their role and responsibilities, and the possible impact of this on them and students.

Research design and methodology

The study’s conceptual framework used the figured worlds theory developed by Holland et al (Citation2001). Built on the work of Vygotsky (Citation1978), Bakhtin (Citation1981), and Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977) figured worlds theory is used to study how humans see their place in different environments and contexts. Figured worlds theory proposes that humans have a propensity to create or engage with ‘as if’ worlds and that an individual’s identity and agency are linked to and formed by these worlds (Holland, D., Lachicotte Jr., W., Skinner, D. & Cain, C. Citation2001). When applied to this study, figured worlds allowed the acceptance of participants’ responses as only being an insight into their perception of the use of pastoral support staff (PSS) and the delivery of pastoral care in their school(s), and therefore, their world. Explicitly, the worlds discussed are real places – schools, but each participant may have a different view of the world and their worlds.

A pragmatic sequential mixed method design was considered the most appropriate for this research and conceptual framework, using a multiple case study methodology to enable both qualitative and quantitative data to be collected, collated, analysed and interpreted through an online survey and semi-structured interviews (Yin, Citation2009). The two sets of data were interdependent, with the qualitative survey data used to support the qualitative data generated through the survey and interviews (Morse, Citation2003). This approach allowed both the assessment of the volume of non-qualified teacher pastoral staff in schools and the identification of any changes in responsibility for pastoral care, through the online survey and interviews. It was designed specifically to answer the research questions. The sampling strategy followed the recommendations of Creswell and Plano Clark (Citation2011).

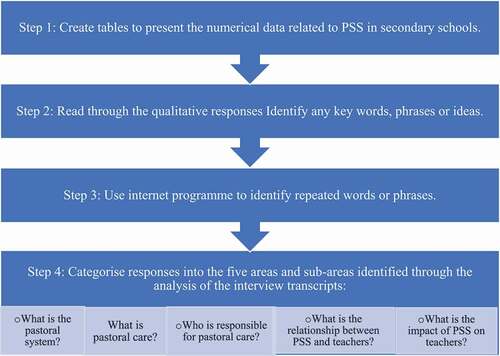

The online survey participants were purposefully sampled based on their connection through professional links to the researcher as a qualified secondary school teacher and Teach First ambassador (Teddlie & Yu, Citation2007). The survey was emailed out to teachers working in secondary schools across London and the South East via a network of former work and training colleagues. The online survey asked respondents fourteen questions about their institution, role, and experiences working with non-qualified teacher pastoral staff. The option to include an open-ended question to collect qualitative data within a nominally quantitative survey was one which utilised the opportunity to hear individual voices within the survey. This allowed for the identification of links or common themes within these findings, as well as in the interview data. Forty-six qualified teachers and five non-qualified teachers completed the online survey over a period of seven months. The qualitative data from the survey was initially analysed using ‘WordCounter’ (https://wordcounter.net/) to identify repeated words or phrases. The quantitative survey data was collated into bar charts and percentages by the survey platform, as well as the mean, standard deviation, and variance. The survey analysis followed the steps shown in .

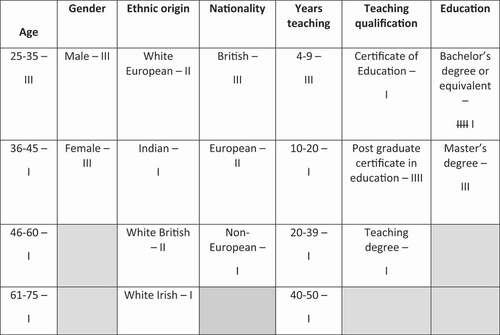

The six interview participants were selected either through the online survey (self-selected), or through colleagues and associates who had expressed a willingness to be interviewed or were able to suggest others. None of the interview participants were colleagues who worked with the researcher directly or indirectly (e.g., local authority). They represented all levels within a school’s hierarchy: a classroom teacher and form tutor; a middle leader and form tutor; a lead practitioner and form tutor; an assistant headteacher; a retired deputy headteacher, and a headteacher. Other distinguishing characteristics of interview participants can be seen in .

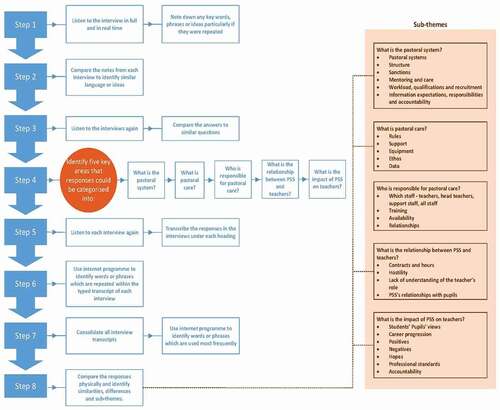

Accepting the figured worlds as described by each of the teachers who participated in the survey and were interviewed, the analysis focused on their understanding of how pastoral care is delivered rather than questioning their description or explanation of how pastoral care was delivered in their school(s). Semi-structured questions were used for the recorded interviews and provided the qualitative data (Silverman, Citation2006). Using a narrative analysis approach (Mertens, Citation2015) recordings were listened to and compared after each interview and key ideas and significant or relevant words and repeated phrases (units of meaning) noted. The responses were viewed as a narrative to reveal the different perspectives on the issues of pastoral care and the employment of PSS.

The responses to the interview questions were transcribed by hand (Mertens, Citation2015) and then typed up for each of the participants. These were then analysed using ‘WordCounter’ to identify the words used most frequently by each participant. The units of meaning gathered from the responses were categorised into five areas: what is the pastoral system; what is pastoral care; who is responsible for pastoral care; what is the relationship between PSS and teachers; what is the impact of PSS on teachers (Cohen et al., Citation2000). Focus was targeted only on the words said and their frequency (Cohen et al., Citation2007). Coding was used to collate the responses, identify similarities and differences and identify further sub-themes (Mertens, Citation2015) under each of the five areas. illustrates the analysis steps for the interviews.

Following guidance from the British Educational Research Association (British Educational Research Association, Citation2018) ethics approval was sought and granted by Canterbury Christ Church University, UK. Due to the researcher’s position as a middle leader in a school it was decided to exclude this school from the research as she acknowledged her position as an insider research (Beynon, Citation1985) and wanted to avoid jeopardising her own position within the school and her relationships with her PSS colleagues. The privacy and safeguarding of the students the participants might mention during the data gathering was also carefully considered (Frankfort-Nachmias & Nachmias, Citation1992), and as a result a safeguarding process was prepared in case action was deemed necessary (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2015a).

Findings

In this section ‘all participants” refer to the combined findings from the online survey and the interviews. When findings relate to either the online survey or interview findings it is stated as such or in terms of respondents or participants.

Despite the question and the label, there was little discussion of ‘care’ or its synonyms when participants described what they understood pastoral care to mean from both the online survey and interview findings. Instead, participants described it as an opportunity to work ‘with the whole child’ and the ‘most fulfilling’ part of their job as shown by the following response:

I think pastoral care is a core part of being a teacher. We are here to educate the whole child and teach them how to be decent citizens, good friends, reliable employees and in time strong parents. (online survey respondent)

All interview participants also emphasised the need for pastoral care, due to the amount of time they take to resolve ‘issues’ or ‘problems’ faced by students, including child exploitation, issues surrounding poverty and abuse. All interview participants discussed behaviour as either the ‘main’ or the most important element of the pastoral role with thirty-five per cent of survey respondents listing ‘behaviour management’ as a skill required for someone in a pastoral role.

I think pastoral care in school is about maintaining rules and boundaries for students in the most basic of ways in terms of things that are very black and white. (interview participant)

Other interview participants and survey respondents included additional areas of expertise needed to be able to fulfil the pastoral care role:

knowledge of school systems and policies and a commitment to follow them fully - approachable to students and staff - excellent behaviour management.(online survey respondent)

Good pastoral care has three basic aims: know & understanding pupils, their problems, interests, hopes and ambitions; to fulfil their potential academically, socially and spiritually, to establish a close working relationship with parents. (interview participant)

Teacher training for fulfilling pastoral roles

Concerns were raised for those teachers working as heads of years and the demands of the role combined with the planning and marking responsibilities of teaching by some survey respondents and interview participants. One interview participant claimed:

it’s hard to be able to balance the two. Anyone who can is a really good,

a fantastic, obviously an outstanding practitioner.

Another participant explained that it is difficult to recruit heads of year and often teachers had to be ‘persuaded’ to do the job. A further interview participant explained the benefit of employing PSS as a way of keeping good teachers in the classroom, but also challenged how a non-teacher would be able to understand the demands and nuances of the role.

To become a Head of Year, you normally would want to be a good teacher in

the classroom As you’re promoted to Head of Year, you do less time in the

classroom, so the big advantage of [PSS] would be to free up good teachers to

go back in the classroom, but the downside I can see is if these people are not

teaching, they don’t have no idea.

Another explained they believed their school only employed PSS as an attempt to ‘divorce the pastoral from the teaching and learning’ and therefore reduce teacher workload.

Ninety per cent of survey respondents believed teachers were suitable for pastoral positions. Those who disagreed identified concerns about workload and queried whether it was possible to do both jobs well. They believed more training was required in addition to current teacher training to prepare teachers for the role. This was repeatedly referenced by survey respondents as required for teachers to help them understand the issues within their schools and for those in pastoral positions. One wrote that the pastoral role should be carried out by:

Trained Teachers with training or experience in counselling and psychology

or behavioural management. (online survey respondent)

Survey respondents communicated concerns about a lack of expertise within teacher training organisations and within schools about the issues affecting students. Seventy-four per cent felt teacher training does not prepare teachers to undertake pastoral responsibilities. Participant responses included:

Teacher training is concerned primarily with preparing individuals to deliver

lessons and to ensure behaviour conducive to ensuring those lessons can be

delivered. Little attention is paid to the kinds of behavioural and emotional difficulties students are faced with. (online survey respondent)

Pastoral Support Staff role, responsibilities, and impact

When questioned, several of the interview participants expressed confusion about qualifications required for PSS positions within their school. One participant with responsibility for employment of PSS described the required skills as: strong administrative skills; strong skills building relationships with teachers and parents; able to conflict manage; run and adhere to behaviour management system explaining formal qualifications were not the primary concern when recruiting PSS.

How, when and why information is conveyed was a theme in the survey responses and throughout the interviews. One interview participant discussed limited access to information amounting to ‘sporadic emails’. Another admitted they did not know how to access information about students within their school. A lack of clarity about what could be expected from PSS led some to question the systems in place to assess or appraise PSS. A further participant described the lack of understanding of curriculum, lesson planning and data analysis as part of the issue with PSS because without engaging with data and progress they were only dealing with one ‘side’ of a student’s school life. The ‘one side of the coin’ analogy was also used by other participants to explain how students need to be supported with all elements of their school life by people who could understand all parts of their lives.

Survey respondents reported PSS availability and sole focus on their pastoral duties led to an immediate resolution of issues; good understanding of their cohort and the challenges they face; an ability to form relationships with parents; an ability to monitor target groups or students throughout the day and availability to liaise with outside agencies.

When asked to report on negative experiences working with PSS, survey respondents reported: resentment between the two groups; ‘friendly’ relationships between PSS and students; a lack of understanding of the teacher’s role and workload; a lack of transparency in sharing information with teachers; a lack of accountability; a lack of understanding of student progress; students removed from lessons for time with PSS; lack of support and a lack of professionalism. One respondent highlighted the communication and language skills of some PSS did not meet the standards expected of teachers:

I have unfortunately worked with several pastoral leaders/deputy leaders who

in my view were unprofessional and inappropriate in their use of language/over familiarity shown to students. (online survey respondent)

and another wrote:

Generally, they lack understanding of how students learn and act in the classroom. (online survey respondent)

One felt PSS’s communication with students, appearance, behaviour around students and professionalism did not match those expected of the teaching staff. A further respondent believed any over reliance by students on PSS was a failure of the pastoral system and that this is not just damaging to the students, but also to teachers.

In my experience, some staff in pastoral positions relish knowing personal information about children which they use as an excuse for poor behaviour but don’t share with teachers. Therefore, in some cases classroom teachers are set up to fail with a child because building a strong relationship has been made impossible. (online survey respondent)

Most interview participants recognised the need for non-teachers to complete the administrative tasks associated with being a head of year, but also questioned the training and support offered to PSS to prepare them for the more demanding emotional or therapeutic aspects of the role of head of year. Concerns were also raised in relation to the ‘friendly’ relationships PSS were described as developing or encouraging with students. Frustrations between PSS and teachers became apparent particularly around a perceived lack of accountability for PSS versus that faced by teachers. This was key to some participants’ figured worlds in relation to PSS. It was also the case that the line management and contractual arrangements were unclear:

Participant L was “not clear” on the line management structure and thought that PSS were on different contracts.(interview participant)

Discussion

It is well evidenced that high levels of organisational trust have been found to benefit school employees and that a lack of it can lead to resentment (Baier, Citation1987; Hoy, Citation2012; Tschannen-Moran, Citation2014; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). Analysis of the data from this study indicated a clear lack of trust in several areas between teachers and PSS. Such a finding is crucial to this discussion as the relationships and the participants’ and respondents’ perceptions, feelings and beliefs about the relationships form part of teachers’ figured world(s). Interestingly, The Teachers’ Standards in England (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2011) place responsibility on teachers to maintain or build positive relationships with colleagues including support staff, whereas PSS have no such accountability. Previous research studies have defined trust as having five characteristics: benevolence; reliability; competence; honesty and openness and these are used to examine the trust between PSS and teachers (Hoy, Citation2012; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000).

Benevolence

Benevolence can be considered as the confidence that the trusted group or person will act in ways not to harm the other party (Hoy, Citation2012). Many of the participants in this study shared experiences of feeling judged or undermined by PSS and of having heard PSS make denigrating comments about teachers and their practice sometimes in the presence of students. Two interview participants, both responsible for line managing PSS, attributed this to many PSS’s only experience of a school as having been a student themselves. Of course, it can be argued that a teacher’s own experience of education also influences their practice, but they have experienced the classroom in at least three ways: as a student, a teacher, and an observer (Bukor, Citation2015; Day et al., Citation2006; Taber, Citation2009). Some participants explained PSS may find it easier to identify with the student in a situation than the teacher. This, they felt, further weakened the trust between the groups. Also, the behaviour management systems in some schools were dependent on PSS coming to teachers’ classrooms as on-call to provide support or remove students when necessary. Some survey respondents and interview participants remarked that teachers working in schools with these types of behaviour systems might feel judged or embarrassed in their interactions with PSS, leading them to feel inhibited and reluctant to use the behaviour management systems as set out in their school behaviour policy. This again could lead to weakened levels of trust between teachers and PSS.

Reliability

Reliability is the belief the other party will act in a predictable way (Hoy, Citation2012). Interestingly, all participants discussed what could, should and ought to be done by PSS, but they did not seem to have any recourse to address these matters when not completed in ways teachers felt appropriate. Some interview participants reported different approaches used by PSS within the same school and the inconsistent sanctions issued by PSS operating in different areas within the school.

Competence

Competency is another area of trust, and research shows that there is a tendency to trust only those with skill and competence (Hoy, Citation2012; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). Most participants were working in schools of high need and some had experience of working with a range of paraprofessionals in schools as part of Government’s Street Crime Initiative (Hallam et al., Citation2005). Indeed, participants were not averse to experts or professionals working in schools, and indeed many survey respondents expressed a need for more counsellors in schools. However, the interview participants were unclear about the qualifications required to undertake PSS positions in schools. Comments made by interview participants posed about the skills, qualifications and training of PSS suggested a lack of trust in their PSS colleagues’ skills. One said:

If they were not teachers, they should, I would expect that they have done some

qualification or at least, not necessarily a degree, but experience in working with

young people that is kind of measurable.

Findings also showed that some teachers perceive that PSS can impact negatively on their professional standing. One survey respondent said:

The head of pastoral says, ‘bad behaviour is because of bad teaching.’ There

is a culture of blame and them and us.

An interview participant said:

if a teacher has a torrid time with a student and the member of staff [PSS]

comes and is fully supportive of the student, puts their arm around them, … .

as if to say, ‘Don’t worry about the teacher.’ That’s completely what

you have to try and avoid from pastoral staff.

Others however undoubtedly value the support of pastoral staff.

I have a positive relationship. I try always to be proactive. There are some

that are amazing, really great (interview participant)

Honesty

Honesty is significant as it cements trust (Hoy, Citation2012; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000) and a sense of collective efficacy has been found to have a measurable impact on student success. Goddard et al. (Citation2017, p. 1) define this as ‘the sense among group members that they have the capability to organize and execute the courses of action required to achieve their most important goals.’ Yet, some participants reported a them and us culture with both sides having seemingly different goals and aims.

One example of the ‘them and us’ culture which was reported with resentments on both sides is the way their own ‘wellbeing’ is supported by school leaders. The emotional toll of teaching has been acknowledged, particularly for those working with those students who have experienced physical or emotional abuse (Cefai & Cavioni, Citation2014; Hanley, Citation2017). It has also been recognised teachers can suffer from or are at risk of secondary traumatic stress when working with students who have been affected by trauma and therefore should have access to clinical consultation when needed (Reinbergs & Fefer, Citation2017). However, this study has found that this emotional charge of working with young people seemed to be recognised for PSS with some schools offering PSS counselling or supervision, but not for teachers. This is especially surprising considering that teacher stress and mental ill-health is linked to the significant number of teachers who leave the profession (Bajorek et al., Citation2014; Roffey, Citation2012).

Openness

Finally, openness promotes trust whereas secrecy breeds distrust (Hoy, Citation2012; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). Distributed leadership has given everyone a sense or the illusion of leadership. Some of the titles used for PSS include leader or director in the title (Ball, Citation2013; Lumby, Citation2016) and Lumby (Citation2016) argues this distributed leadership is used to hide the inequality amongst staff. It has also helped to obscure an increase of non-workers in schools – those who do not contribute to the main labour of schools: teaching (Carter & Stevenson, Citation2012).

The findings in this study therefore suggest that the participants of this research study thought teachers and PSS felt either perceived or real inequalities. Participants who had line managed PSS described PSS’s irritation at a lack of parity with teachers in terms of hours worked and holiday allocations, whereas teachers felt the high status of PSS, plus the benefits of not having to teach and complete the associated additional tasks, teamed with a lack of perceived accountability was unfair. Support staff in secondary schools were found to be less likely to be supervised by a teacher than in primary schools and some were not supervised at all (Blatchford et al., Citation2009). Historically, schools have been intrinsically hierarchical in which teachers, TAs (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2015b) and students are held accountable against standards and rules. Administrative and operational staff also have their set tasks to complete and the use of subjects or faculties provides a clear line management structure apparent to all. Pay for teachers is also determined initially via length of service with increases permitted based on the need for their subject expertise, additional experience, qualifications, or responsibility. The introduction of PSS, without the same clear structure whose time appears largely unregulated and tasks are largely unseen can be said to add to the resentment felt particularly by teachers. This lack of clarity is not the fault of either teachers or PSS. School leadership teams need to be responsive to the changes within their organisations (Harris & Spillane, Citation2008) and to consider the impact of their decisions, particularly on the professional role of the teacher.

Conclusions and recommendations

Findings from this small-scale study indicate that there is a place for well-managed support staff in schools providing administrative support for pastoral care providers, form tutors and heads of year. It shows that there is a need for child behaviour and psychology experts in schools to provide training to teachers and support students when specialist intervention is required. However, findings have also highlighted that there is a lack of trust between teachers and PSS in some schools. It is concluded here that reasons for this appear to be associated with a lack of clarity about PSS roles and responsibilities, the required levels of expertise and daily working standards and expectations. Also, as detailed in the discussion section above some teachers are perceiving that when another non-teaching staff member acts as a ‘rescuer,’ it is impacting negatively on their professional standing. Therefore, it is recommended that training to enable PSS to develop nurturing relationships with students and productive ones with staff and students is required. Also, it is concluded that similar accountability measures that exist for teachers and teaching assistants (TAs), need to be put in place for PSS, to help address the lack of trust between different groups of colleagues. To support such developments, it is suggested that a national guidance document on pastoral care for all secondary (and primary) schools in England should be considered.

Without doubt students will continue to need adult guidance, support, and advice during their time at secondary school and it is not surprising if they seek out those who they view as ‘other’ to teachers. Recruiting from the local community means staff may have existing non-school relationships with students. These should be identified and overseen by school leadership teams to keep staff and students safe. Conversely, a student may not want to turn to someone from their community, but rather an independent, impartial professional such as a teacher to turn to when they require pastoral care. The priority for school leadership teams should be making clear to all students the specific roles different staff members fulfil. They should also recognise the importance of line management protocols, to ensure all staff are fully aware of school safeguarding and pastoral processes and systems.

As schools become more dependent on PSS to fill the gaps caused by the teaching crisis, there is greater risk that students with SEMH needs will spend the majority of their time being supported by non-qualified or non-expert PSS rather than being taught by qualified teachers. Without trusting relationships between PSS and teachers, students with SEMH needs are placed further at risk if the adults around them do not share the relevant information required to ensure the student benefits from a cohesive approach. Such environments may mean that teachers only see themselves responsible for students who are able to behave ‘appropriately’ in their classroom. Therefore, students with SEMH, by default, may spend an increasing amount of time out of classrooms supported by non-qualified teaching staff, with fewer opportunities to develop the skills and strategies required to enable them to benefit from lesson time.

Limitations

The concerns of teachers identified in this study are more significant than anticipated as they indicate impact on teachers’ self-esteem and their ability to support students without full knowledge of their needs, as well as damaging the trust between teachers and PSS. The research model did not allow enough time to explore these themes, nor were the interview or survey questions designed to gather information around this area.

This study was small-scale. It only included fifty-one survey respondents and six interview participants. Respondents and participants were found to be disproportionally representative of schools in areas of high need. The study also did not include the views of PSS or any explanation as to why they may withhold information from teachers or be perceived to have friendly relationships with students.

Further research

There is a need to identify the impact of PSS, on students’ welfare, attendance and achievement (Blatchford et al., Citation2009). It is fundamental that the study looks at what the impact is on students working with and being supported by PSS rather than qualified teachers.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to my former employers who kindly funded the taught element of the EdD (First author).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baier, A. (1987). Trust and antitrust. Ethics, 96(2), 231–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/292745

- Bajorek, Z., Gulliford, J., & Taskila, T. (2014). Healthy teachers, higher marks? establishing a link between teacher health and wellbeing, and student outcomes. The Work Foundation.

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: four essays by M.M. Bakhtin. University of Texas Press.

- Ball, S. J. (2013). The education debate. Policy Press.

- Beynon, T. (1985). Initial encounters in the secondary school. Barcombe: Falmer Press.

- Blatchford, P., Bassett, P., Brown, P., Martin, C., Russell, A., & Webster, R. (2009). Deployment and impact of support staff project. Institute of education. University of London. Available http://maximisingtas.co.uk/assets/content/dissressum.pdf

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1977). Reproduction in education, society, and culture. beverley hills. CA: Sage Publications.

- British Educational Research Association. (2018) . Ethical guidelines for educational research. BERA.

- Brown, R. (2018, October). Mental health and wellbeing provision in schools – Review of published policies and information. research report. DfE.

- Bryk, A. S., Lee, V. and Holland, P. B. (1993). Catholic schools and the com- mon good. Harvard University Press.

- Bukor, E. (2015, April 3). Exploring teacher identity from a holistic perspective: Reconstructing and reconnecting personal and professional selves. Teachers and Teaching, 21(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.953818

- Burgess, S., & Allen, R. (2012) “How long are teachers staying for?” Centre for market and public organisation research in public policy. University of Bristol. Available at: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/cmpo/migrated/documents/howlongteachersstaying.pdf.

- Carter, B., & Stevenson, H. (2012). Teachers, workforce remodelling and the challenge to labour process analysis. Work, Employment and Society, 26(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012438579

- Cefai, C., & Cavioni, V. (2014). From neurasthenia to eudaimonia: teachers’ well-being and resilience. In C. Cefai & V. Cavioni (Eds.), Social and emotional education in primary school,133-148 Springer.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). Routledge.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th edition ed.). Routledge.

- Cooper, P. (2008). Nurturing attachment to school: Contemporary perspectives on social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Pastoral Care in Education, 26(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940701848570

- Cooper, P., Drummond, M. J., Hart, S., Lovey, J., & McLaughlin, C. (2000). Positive alternatives to exclusion. Routledge Falmer.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006, August). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600775316

- Department for Education (DfE). (2011) . Teachers’ Standards. DfE.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2015a) . Working together to safeguard children A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. DfE.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2015b). Professional standards for teaching assistants - Departmental advice for headteachers, teachers, teaching assistants, governing boards and employers. DfE.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2016). Schools workforce in England 2010 to 2015: Trends and geographical comparisons. DfE.

- Department for Education (DfE). 2017b. School Workforce in England: November 2016,DfE. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/620825/SFR25_2017_MainText.pdf

- Department for Education (DfE). (2018a). School workforce in England. In November 2017. DfE.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2018b). Statement of intent on the diversity of the teaching workforce – Setting the case for a diverse teaching workforce. DfE.

- Edmund, N., & Price, M. (2009). Workforce Re-modelling and pastoral care in schools: A diversification of roles or a de-professionalisation of functions? Pastoral Care in Education, 27(4), 301–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940903349336

- Egalite, A. J., Kisida, B., & Winters, M. A. (2015). Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 45 (C), 44–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.01.007

- Felner, R., Seitsinger, A., Brand, S., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2007). Creating small learning communities: Lessons from the project on high-per- forming learning communities about “what works” in creating productive, developmentally enhancing, learning contexts. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 209–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701621061

- Frankfort-Nachmias, C., & Nachmias, D. (1992). Research Methods in the Social Sciences (4th edition ed.). Edward Arnold.

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Freiberg, H. J., Huzinec, C. A., & Templeton, S. M. (2009). Classroom management–A pathway to student achievement: A study of fourteen inner-city elementary schools. The Elementary School Journal.110(1), 110(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/598843

- Goddard, R. D., Skrla, L., & Salloum, S. J. (2017). The role of collective efficacy in closing student achievement gaps: a mixed methods study of school leadership for excellence and equity. Journal of Education for Students Placed At, 22(4), 220–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2017.1348900 Risk. (JESPAR)

- Graves, S., & Williams, K. (2017). Investigating the role of the HLTA in supporting learning in English schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(2), 265–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1157138

- Hajdukova, E. B., Hornby, G., & Cushman, P. (2014). Pupil–teacher relationships: Perceptions of boys with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2014.893007

- Hallam, S., Castle, F., & Rogers, L. (2005). Research and evaluation of the behaviour improvement programme. Department for Education and Skills.

- Hamblin, D. (1978). The teacher and pastoral care. Blackwell.

- Hanley, T. (2017). Supporting the emotional labour associated with teaching: Considering a pluralistic approach to group supervision. Pastoral Care in Education, 35:4(4), 253–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2017.1358295

- Harris, A., & Spillane, J. (2008). Distributed leadership through the looking glass. Management in Education, 22(1), 31–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020607085623

- Herrero, J., Estévez, E., & Musitu, G. (2006). The relationships of adolescent school-related deviant behaviour and victimization with psychological distress: Testing a general model of the mediational role of parents and teachers across groups of gender and age. Journal of Adolescence, 29(5), 671–690. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.015

- Holland, D., Lachicotte Jr., W., Skinner, D. and Cain, C. (2001). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Hoy, W. (2012). School characteristics that make a difference for the achievement of all students: A 40-year odyssey. Journal of Educational Administration, 50(1(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231211196078

- Humphrey, N., Lendrum, A., & Wigelsworth, M. (2010). Social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) programme in secondary schools: National evaluation. Department for Education.

- Loeb, S., Darling-Hammond, L., & Luczak, J. (2005). How teaching conditions predict teacher turnover in california schools. Peabody Journal of Education, 80(3), 44–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje8003_4

- Luekens, M. T. (2004). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the teacher follow up survey. 2000-01. In Washington, DC: National Center for education statistics, U.S. Dept. of Education, institute of education sciences. E.D. Tabs.

- Lumby, J. (2016). Distributed Leadership as a fashion or fad. Management in Education, 30(4), 161–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616665065

- McLean Davies, L., Dickson, B., Rickards, F., Dinham, S., Conroy, J., & Davis, R. (2015). Teaching as a clinical profession: Translational practices in initial teacher education – An international perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(5), 514–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2015.1105537

- Mertens, D. M. (2015). Mixed methods and wicked problems. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814562944

- Mihalas, S., Morse, W. C., Allsopp, D. H., & McHatton, P. A. (2009). Cultivating caring relation- ships between teachers and secondary students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Implications for research and practice. Remedial and Special Education, 30 (2), 108–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932508315950

- Morse, J. M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design, 241-272 In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Sage.

- Murphy, J., & Holste, L. (2016). Explaining the effects of communities of pastoral care for students. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(5), 531–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.993460

- Office for National Statistics (2012) “International migrants in england and wales: 2011.”

- Ofsted. (2019) . The education inspection framework, Framework for inspections carried out, respectively, under section 5 of the Education Act 2005 (as amended), section 109 of the education and skills act 2008, the education and inspections act 2006 and the childcare act 2006 (draft).

- Pomeroy, E. (1999). The teacher–student relationship in secondary school: Insights from excluded students. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(4),465–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995218

- Quint, J. (2006). Meeting five critical challenges of high school reform: Lessons from research on three reform models. Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

- Reinbergs, E., & Fefer, S. A. (2017). Addressing trauma in schools: Multitiered service delivery options for practitioners. Psychol Schs, 2018(55), 250–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22105

- Rice O’Toole, A.-M. (2020) “The role of qualified teachers in the modern secondary school: Whose responsibility is pastoral care in secondary schools?” (unpublished thesis) Canterbury Christ Church University.

- Roffey, S. (2012). Student well-being: Teacher well-being – Two sides of the same coin. Educational and Child Psychology, 29(4), 8–17. .researchgate.net/publication/285631404_Pupil_wellbeing_-Teacher_wellbeing_Two_sides_of_the_same_coin

- Rudduck, J., Chaplain, R., & Wallace, G. (eds.). (1996). School Improvement: What can pupils tell us? David Fulton.

- Silverman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction (3rd edition ed.). Sage.

- Taber, K. S. (2009) “Learning from experience and teaching by example: reflecting upon personal learning experience to inform teaching practice.”. Journal of Cambridge Studies, March, 4(1), 82–91. (invited opinion piece).

- Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292430

- Tschannen-Moran, M. (2014). Trust Matters: Leadership for successful schools. 2nd Edition. John Wiley and Sons.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 547–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004547

- Tucker, S. (2013). Pupil vulnerability and school exclusion: Developing responsive pastoral policies and practices in secondary education in the UK. Pastoral Care in Education, 31(4), 279–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2013.842312

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press.

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26(suppl 1), 1460–2245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar075

- Wei, F. (2007). Cross-cultural teaching apprehension: A co-identity approach to minority teachers. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 110(110), 5–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.269

- Wentzel, K. R. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73(1), 287–301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00406

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th edition ed.). Sage.