ABSTRACT

The current pandemic has caused unprecedented disruption across the world. Government-led efforts to prepare for emergencies of this kind have focussed upon maintaining vital social and economic function while reducing disease. In some respects, the UK has seemed unprepared for this pandemic, although radical policies and interventions have been applied as the situation has progressed. Schools are a significant point of connection in any national emergency strategy. This study has explored the experience of a group of primary school leaders based in a medium-sized town in the north of England. Analysis of a focus group discussion has highlighted the potential of schools to provide safeguarding and pastoral care to Children and Young People (CYP) through an anxious period of social isolation. Examination of the interactions across systemic levels has highlighted weaknesses and omissions in the Government’s current pandemic strategy as it relates to the care and education of CYP at a local level. From this examination, recommendations for action have been made.

Introduction

The current pandemic, novel coronavirus Covid-19, began in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. The infection has steadily spread across the globe (13,967,833 identified cases and 593,100 deaths by 17.7.20). The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Covid-19 a global pandemic on 12th March and the first officially reported death from Covid-19 in the United Kingdom (UK) was declared on 5th of March 2020. The outbreak in the UK escalated quickly and on the 23rd of March the UK government imposed a lockdown. This radical intervention was intended to reduce transmission of the virus by imposing quarantine and a social distance between most people, while allowing others to travel and work in order to maintain the continuity of vital services. The lockdown involved the immediate closure of schools for all but the most vulnerable pupils, as well as the children of key workers. In fact, many schools continued to function, often in innovative ways, as this research confirms. School leaders have mediated aspects of the government’s emergency response to the crisis: they have been well-placed to communicate key messages to parents and to coordinate care and support around children and families if needed, within local authority structures (DHSC, 3.3.20).

As a practicing educational and child psychologist (EP) I have had experience working with schools following traumatic or disruptive events. Indeed, educational psychology services usually provide critical incident intervention as part of their core offer to schools and local authorities. This can include consultation and emotional support for school leaders as well as direct work with affected staff and pupils, within a general strategy of supporting a school community to understand and adapt to the challenges presented by the critical incident (Hayes & Frederickson, Citation2008; McCaffrey, Citation2004). Although there has been no empirical work to date, which documents educational psychology’s contribution during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, it is widely known that visits to homes and schools by peripatetic services were stopped in the first lockdown order. Virtual practices have emerged quickly, and many aspects of EP work have continued but there has been some uncertainty about what the needs of children, families and schools might be, during, and following lockdown (Morgan, Citation2020).

At the start of the lockdown, I began to wonder how schools would manage to provide education and exercise their safeguarding responsibilities in such unusual circumstances. Although I understood various services and systems were adjusting their response to children and young people’s education, health, and social care needs, I did not know what this involved or how effective it was likely to be. In the early days of the pandemic, it did not seem clear how my own profession would contribute. My motivation for this study arose directly from the concern and curiosity I felt at this time. Like many people, I read the news and various social media avidly to gain some intellectual and emotional purchase upon the unprecedented experience. I also began to read academic literature, much of it from disciplines quite unfamiliar to me: for example, disaster management and public health. I began to frame my understanding of schools, and the way they function, in a wider context of policies and ideas. Some of these perspectives align well with educational psychology practice frameworks. I will attempt to present the understanding I constructed from this reading before describing the small scale-study I undertook with school leaders in the group of primary schools I regularly work with.

The importance of community organisations, including schools, in pandemic preparedness and response is outlined in the WHO’s influential report ‘Whole of Society Pandemic Readiness’ (2009). The current Government has identified itself as a ‘leading supporter of the international rules-based system’ relating to public health, devised by various organisations, including the WHO (PHE, Citation2014). The WHO have devised a ‘readiness framework’ in planning and implementation, based on the assumption that a serious pandemic would quickly undermine the functioning of essential services. Acknowledging the vulnerability of society as a whole and vulnerable groups in particular, to the potential breakdown of complex systems of ‘interdependency’, the ‘readiness framework’ highlights ‘core-preparedness actions’ most of which we are now quite familiar to us through the implementation of the lockdown strategy: absenteeism of key workers through illness, the need for protective equipment and stockpiling, essential and non-essential activity, infection-control and social-distancing’ (World Health Organisation, Citation2009). This 2009 document remains an influential guidance for countries evaluating their own pandemic preparedness (Wignjadiputro et al., Citation2020).

Although clearly influenced by the WHO guidance, the UK government’s ‘Pandemic Influenza Response’ (PHE, Citation2014) describes the WHO responses as ‘inflexible’ and introduces an alternative framework for responding to influenza and ‘influenza-like’ viruses: Detection, Assessment, Treatment, Escalation and Recovery (DATER). This 2014 document focuses on maintaining healthcare provision through a pandemic, and there is significantly less focus on the societal adaptations, which have been applied in response to Covid-19. Towards the end of this report, the key assumptions underpinning the advice are described: it is assumed that monitoring at the border would not prevent spread of the disease, and that up to 50% of the UK population would be ‘affected in some way’ by the pandemic (2014:65). The possible need for social-distancing measures and quarantine, and increased stockpiling of PPE are not referenced in the 2014 pandemic planning document but are referenced in the government’s ‘UK Biological Security Strategy’ (Gov.UK, Citation2018).

The recently published ‘Coronavirus Action Plan: A guide to what you can expect across the UK’ (Gov.UK, 3.3.Citation2020), outlines the necessity of social-distancing measures as well as restrictions to travel. This suggests that some of the assumptions about the severity and impact underpinning the Government’s planning for an ‘influenza-like’ illness may have changed and become more aligned with the whole of society approach described in the WHO document (2009). To date, the UK government has resisted pressure to acknowledge changes in strategy and has promoted the view that analysis of possible mistakes should be postponed until after the emergency.

Although the role of schools in disaster planning and preparation is not much explored in the existing research, there is a body of literature, which demonstrates that when disasters occur – for example, floods (Beaton and Ledgard, Citation2012), earthquakes (Mutch, Citation2018), epidemics (Hallgarten, Citation2020) – schools play a vital role in maintaining social cohesion and social connectedness: ‘Schools take on additional responsibilities at all stages of the disaster cycle and contribute to the ongoing well-being of their students, families and communities’ (Mutch, Citation2020, p. 4).

In her 2018 article, chronicling school responses to the New Zealand earthquake disasters (2010–2011), Carol Mutch provides an interesting review of disaster research. She cites Drabek’s finding that there are several stages of community response to disasters (Drabek, Citation1986). Early warnings are often ignored or dismissed, and first responses are often not well-organised. The initial shock of the disaster disrupts existing social bonds as social routines and boundaries are suddenly altered. Through an intense period of re-organisation these bonds are quickly reformed, and ‘a new emergent and context-related social fabric emerges with little similarity to previous structures’ (Gordon, Citation2004, as cited in Mutch, Citation2018, p. 334). If appropriate plans and strategies are put in place, a period of social cohesion follows and in this period a sense of community pride and optimism can develop. However, if the challenges are prolonged social cohesion can weaken, especially if responses are not well-organised, and communication is poor. There is some risk that a sense of exhaustion, depression and an absence of hope will set in until a viable plan for reconstruction begins to take shape in the community. At this stage, the risk of social breakdown and conflict is high, especially if there is a sense of unequal treatment and unfair distribution of resources (Mutch, Citation2018).

Disaster planning involves the identification of those aspects of a community, which make it vulnerable to threats: environmental, infrastructure, social, and economic. Vulnerability, in disaster situations, arises when individuals and communities cannot gain access to resources and information. This dis-proportionately affects socially and economically marginalised people (Price-Robinson & Knight, Citation2012). It is assumed that a resilient community would find ways to identify and respond to vulnerability in a disaster, to support coping, adaptation and problem-solving at the individual and community level. Schools in the UK have an existing infrastructure to address vulnerability - safeguarding and special educational needs (SEN) frameworks - and these structures might be expected to play a crucial role in a disaster situation. Communities with ‘strong pre-existing networks and connectedness, are able to participate collectively in post-disaster decision-making and recover equilibrium more quickly’ (Thornley et al., Citation2015).

Community psychologists have used social capital (SC) theory to explain how structural aspects of a community can strengthen or undermine the coping of individuals. Social capital theorists focus upon’ the norms, networks, and mutual trust of civil society’ and how these produce ‘cooperative action among citizens and institutions’ (Perkins et al., Citation2002, p. 35). Social norms, which operate in ways, which help to generate trust and reciprocity, are understood to be a form of social capital, available to individuals in adversity or crisis. Effective social support at the micro-level is dependent upon the provision of social capital at the structural level, and integration between settings, agencies, local and national governments boosts social capital because it generates trust (Aldrich, Citation2012; Pita & Ehmer, Citation2020).

This complex relationship between the functioning of social structures and the psychological coping of individuals can be understood in relation to the core intervention of epidemics: the imposition of social-distance and quarantine. Social isolation is a significant source of stress in pandemics. It is known that confinement can undermine physical and psychological health, and that loneliness and a lack of social support can intensify the experience of psychological distress (Bu et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2018). The risk of a significant mental health crisis is particularly high for individuals facing existential challenges relating to their health and safety, food or shelter. The risk is intensified if they are unable to access their primary support networks (Lau & Li, Citation2011; Perkins et al., Citation2002). It is relevant to note here that access to friends, family, community clubs, health providers, social care support, education settings, and shops have been significantly restricted during the Covid-19 pandemic, and lockdown.

Research in ‘disaster management’ indicates that, despite being crucial to understanding the impact of a pandemic, local knowledge typically does not sufficiently influence on-going pandemic planning (Thornley et al., Citation2015). A key aspect of the UK government’s strategy has been to support research. UKRI (UK Research and Innovation) has recently issued a call for research exploring the psychological and educational impact of Covid-19 and associated policy implementation (UKRI, Citation2020). UKRI is also seeking information on how society might change for the better, ‘what can be learned’ from our experience of pandemic and how ‘National Recovery and Transformation might be achieved’. This focus on social policy and societal resilience is explicitly referenced in the WHO whole-of-society approach. Strong (Citation1990) identifies this focus on the ‘liminal’ opportunities of adversity as a feature of pandemic response and research around experience of pandemics.

The aim of this research is to contribute to the developing understanding of the impact of this pandemic on a community (a medium-sized town in the North of England) from the perspective of primary school leaders. The town is situated a few miles from a major city. Its population is mainly White-British ethnicity (94.1%, www.ons.gov.uk) and scores slightly below average (for England) on most indicators of health education and financial well-being. Some areas are within the most deprived 10% in England, as identified in the LA’s ‘Index of Multiple deprivation’ (Ministry of housing, Communities and Local Govt, Citation2019). The schools themselves are managed by the LA. They are not academies - schools which are funded by, and managed directly by the DfE. This difference in status has some implications for how some local services are accessed since academies may or may not choose to commission some LA services. The group of schools participating in this research are part of a ‘cluster’ which collectively allocates a portion of their delegated budget to ‘cluster’ services: family support, art/play therapy, speech and language therapy and educational psychology.

Primary schools are a significant point of connection for the organisations and systems that sustain a community, particularly at local government level. Primary school leaders are experienced in navigating the intersections across systems as they implement local and national policies in their work to support children and families. They are familiar with the ethical and practical dilemmas this can present in everyday management. Consequently, the knowledge of primary school leaders’ is likely to be valuable in policy development oriented towards an effective whole of society approach to this ongoing pandemic.

Method

I have undertaken this research with a group of school leaders, with whom I have an existing working relationship (Herr & Anderson, Citation2005). I am therefore familiar with their schools and the local context and undoubtedly bring some of this knowledge to this research.

This paper analyses discursive material produced in a single focus group discussion, and this mirrors in many ways the form of dialogue, which I hope is typical of my practice in these schools. Research which seeks to contribute to problem-solving in local contexts tends to be ‘asset-based rather than deficit [in its] orientation’ (Perkins et al., Citation2002, p. 35), and this perspective has informed each stage of this study. I have tried to be curious, respectful, and collaborative within the learning community, as I would in my practice.

To help me analyse and formulate the complex and ill-defined problems likely to emerge in this investigation I have drawn upon a problem-analysis model often used in educational psychology practice, Frederickson and Cline’s Interactive Factors Framework (Frederickson and Cline, Citation2009). This model is rooted in ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2007). It is often applied to bring a manageable coherence to complex situations and to support the generation of hypotheses of cause and effect (Morton & Frith, Citation1995). Underpinning the model is the assumption that future plans are best derived from a position of understanding. I decided to use this approach to problem analysis after I had transcribed the focus group discussion. Through the process of looking for themes I had noticed that interactions and connections between the different systemic levels were an important aspect of the narratives shared, perhaps not surprisingly given the focus of the research.

My epistemological position and the practice-based problem-analysis are consistent with participatory action-research in its emphasis on the practical and problem-solving values of knowledge production (Newton & Burgess, Citation2008). What is also shared is a harnessing of the ‘insider position’. As in practice, I have attempted to apply reflexivity in my analysis of this material- to rigorously interrogate my own interpretations while also checking back with participants to make sure that I am being consistent with their intended meanings. This approach, which can be broadly described as systematic, dialogical and interpretative, is quite representative of educational psychology’s flexible relationship with ontology and epistemology (Fogg, Citation2017, Williams Citation2013). Although my profession is often associated with positivist practices such as psychometric testing and categorisation since the late 1970s a social constructionist and post-structural perspective, has become more dominant, with an associated turn towards collaborative and holistic assessment, consultation, and organisational development. Associated with this shift in professional practice and professional identity is a critical view of modernist assumptions relating to evidence-based practice.

Moore (Citation2005) has proposed that educational psychology should take an explicitly post-modernist and social-constructivist position in relation to its theory and practice. He suggests that rather than searching for generalizable principles and objective truths EP’s should focus on the messy complexities of situations and seek ways of facilitating understandings that are useful and meaningful to those within these contexts. Although I do not claim that this study has uncovered, or even constructed, a set of truths about these school leaders experience of the first Covid-19 lockdown, I am hopeful that through our process an understanding has been created which has some utility and ‘stability’ in its situated context, and some relevance to those in similar contexts, perhaps sufficient to plan an appropriate course of action (Brinkmann, Citation2017, p. 127). In this respect, I believe it sits within philosophical pragmatism and the epistemological and ontological orientation of post-qualitative educational research (Rosiek, Citation2013).

In translating a practice model to research, I have adapted and reduced Frederickson and Cline’s model to three stages:

These were shared with a group of school leaders, and then explored through a focus group discussion (recorded online video-conference).

Analysis of the discussion to identify aspects of the situation (factors) and how they might be interacting in ways, which are significant to the school leader’s responses to the pandemic. Further email discussion to achieve a more complete understanding of ‘problem dimensions’ and potential causal mechanisms at work in the system (Annan et al., Citation2013, p. 83).

The Problem Map and a draft of the analysis and formulation were taken back to the participants for review and comment. I have included this diagram for transparency but also to allow the reader to make their own interpretations. The process is explicitly iterative. There is no intended point of closure to the interpretation. Within a practical framework, the understanding constructed would be reviewed (ideally) at some point in the future, in a further cycle of information gathering, analysis and synthesis.

Participants in this study were six headteachers from a ‘cluster’ (group) of nine primary schools, and the ‘cluster’ manager responsible for coordinating a range of child and family support services commissioned by the school ‘cluster’.

Initial guiding hypotheses derived from information publicly available

As the pandemic escalated towards quarantine, schools, families and children became directly affected by the government response. While this reduces the risk of virus transmission, it also creates new risks and problems for school leaders to address.

Through this experience, it seems likely that some new practices and perspectives will emerge in relation to schooling, and child/family welfare.

Analysis of the focus group discussion

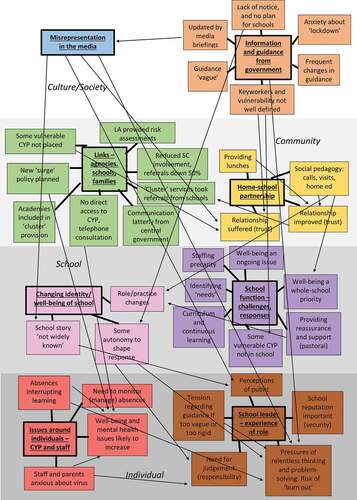

In order to analyse the focus group discussion, I listened several times to the audio-visual recording, then transcribed the spoken text. Through this engagement, I began to identify factors or themes in the talk, which seemed salient to the research questions and important in the context of the discussion. These were organised into groups, which were expressive of overarching concerns/themes. In accordance with the eco-systemic theory, which informs this problem-solving approach, I organised these themes according to system levels (see : Interactive Factors Framework: Problem Map). This allowed me to more easily infer causal influences across systems, guided by the meanings generated in the discussion. The analysis which follows is organised in a way, which mirrors the Problem Map. As previously described, this diagram offers hypotheses, or possible interactions. I presented the Problem Map to the school leaders for comment. From the analysis I produced the following interpretative account of the school leader’s response to the research question, making links to relevant literature. This is followed by a narrative formulation, with proposals for action.

Cultural/ society level

*direct quotes from the focus group discussion are italicised.

Government communication and guidance

The school leaders were given very little notice of the lockdown before it was announced and were unaware of any pre-prepared local or national plan for school closures. In order to understand the constraints within which, they were to work they needed to interpret ‘vague’ instructions, which they often received at the same time as the public, through Media, or Govt televised briefings. The consensus in the group was that schools had been, ‘left to get on with it … .’- to devise their own response to the quarantine. ‘We have done these things without any direction whatsoever. Schools have been left to their own devices and have just basically come through for these kids and these families.’

It was noted that schools across the LA (local authority), perhaps because of the lack of guidance, varied in how much they had continued to provide educational and safeguarding support throughout the lockdown period. For example, some academy chains in the LA were providing only a single ‘hub’ provision, making access more difficult for many families of key workers and vulnerable children.

The identification of key workers, and vulnerable pupils was an early instance of school leaders having to make high-stakes decisions very quickly decisions which had significant ethical and practical impact. It was felt by some that the ambiguity and changeability of the Government Guidance informing these decisions caused parents and carers to ‘lose trust’, potentially undermining the standing of schools in the community. ‘Parents … .couldn’t believe that we didn’t know beforehand’.

The school leaders thought that the lack of clear guidance may have contributed to public uncertainty about how schools were responding to the pandemic. This is something, which I will consider in relation to the role of the media during these first months of the crisis.

The impact of media communication: misinformation and mis-representation

It was noted that the media have played a prominent role in the pandemic: often used as a platform for the communication of official information, potential changes in policy (sometimes through private briefings with journalists), and as a platform for scientific and political debate.

The school leaders viewed the media as having a negative impact upon their experience of working through the pandemic. The frequent Government briefings and leaks caused confusion and it was strongly felt that the media ‘whipped-up’ controversy and conflict. It was observed that schools received unfavourable press coverage when unions questioned the safety of fully re-opening in May and June 2020, and issues relating to school opening more generally had been mis-represented and badly explained. The school leaders expressed frustration that ‘the story of schools’ had not been told’, and that the reality of their work and daily experience had been obscured by a dominant media narrative that schools had been closed since the beginning of lockdown.

Although not alluded to during our focus group, a comparison to the portrayal of NHS staff is relevant. Like educators not all NHS were on the frontline, overworked or at risk, and yet a straightforward ‘worker-hero’ narrative has elicited unequivocal public approval for NHS workers throughout the pandemic so far (Mathers and Kitchen, Citation2020). It seems that the school leaders felt that schools and school staff were excluded from this.

It is known that media representations can express much about the dominant politics and ideology of a culture but also influence how professionals are perceived. Who is defined as a hero is often determined by the agendas of institutions and those with institutional power. Hero status in the media is often precarious (Mathers and Kitchen, Citation2020). Media representations can therefore strengthen or undermine professional identity (collective and individual), and by extension, a person’s sense of self and their well-being (Akkerman & Meijer, Citation2010; Coe et al., Citation2020).

Media representations, and misrepresentations, may have created additional stress, and anxiety for school leaders in this crisis, and it is important to consider how this may have added to the intense emotional and cognitive load associated with managing a complex situation fraught with uncertainty and dilemmatic choice (Phillips & Sen, Citation2011). This accords with what is already known about school responses to disaster incidents. The contribution of teachers is often under-recognised by the public, and there is evidence that this intensifies the stress and emotional exhaustion they experience (Mutch, Citation2018; O’Toole, Citation2018).

Community level

Home–school partnership in the context of ‘social distancing’

The imposition of quarantine meant that schools’ core responsibilities – to educate and safeguard children – had to be exercised differently. The necessity of having to interpret government guidance, in key respects, positioned schools as gatekeepers as the agency providing, or preventing, access to school places, for example.

Government guidance issued early in the lockdown contained definitions of vulnerability, which focussed on children with Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCP’s) and those for whom there were safeguarding concerns (DfE, Citation2020a). However, when making decisions about school places the school leaders were advised to apply ‘LA risk assessments’ in relation to individual CYP they thought might struggle to follow social-distancing routines. Consequently, some children with special educational needs were not accommodated in their schools, despite their vulnerability. LA specialist provisions also offered only limited places. The school leaders believed that the pandemic also produced gaps in safeguarding provision in the LA context. Although social care continued to respond to safeguarding high-threshold referrals, those officially at risk and receiving support from social care were a small proportion of those causing concern in schools: ‘What LA know and what schools know are two completely different things’, ‘ … .instead of 3, it was more like 30ʹ.

Although uncertainty about who should, or could, attend school was anxiety-provoking for school leaders, examples were shared of improved partnership with parents. Communication between school staff and parents became more explicitly pastoral, and some of the practices described by the school leaders were evocative of social-pedagogy, with a strong focus on ensuring participation as a means of addressing disadvantage, and the close alignment between educators values and actions (Moss & Petrie, Citation2019). In the first weeks of the lockdown headteachers took responsibility for delivering free school lunches. Regular phone calls to parents and children allowed specific needs to be identified and action taken. Some school staff – learning mentors for example – made visits to homes, holding conversations from a distance. Lunch packs and work packs could be picked up from school, which was always open during school hours.

These contacts may have ‘communicated some normality’ in strange and unusual times – helping to foster the sense of trust and co-operation associated with ‘community resilience’ (Aldrich, Citation2012). Examples were shared in the discussion of an unexpected intimacy and closeness achieved across the ‘social-distance’ after lockdown was imposed: communication through an open school window, home visits that were ‘knock-a-door and run away’ (to a safe distance), ‘class teachers recording stories at bedtime’, headteachers walking through deserted streets at a time when ‘people were frightened … ., when it was thought you would die if you breathed the air’, and parents updating headteachers on policy changes as they appeared on social media.

As well as indicating some shift in power, and perhaps some democratising of relationships- ‘you became something else other than a headteacher in that first week’- these stories also seemed to express school leaders’ satisfaction in being able to reach out beyond the school (institution) to offer help in the community. Indeed, the phrase ‘community school’ was used several times during the discussion. These school leaders perceived that the pandemic required them to prioritise pastoral care in their work, and this positioning may have strengthened this aspect of their professional identity, perhaps in a way which allowed them to more fully integrate their personal and professional values with their school’s identity.

The potential for relationships to be transformed by acts of care and an ethos of collaboration has been noted in research into disaster responses (Charuvastra & Cloitre, Citation2008, Makwana, 2019), critical incidents (Hayes & Frederickson, Citation2008), and home–school partnership (Hodge & Runswick-Cole, Citation2008). It is important to note, however, that this cooperative consensus tends to be fragile in disaster contexts. Disillusionment and anger can quickly grow if support is withdrawn or there is a perception of abandonment, or compassion fatigue (Thornley et al., Citation2015). Parents of children with special educational needs report that the home-school partnership is sensitive to systemic pressures within the school (Potts, Citation2020). This highlights the potential for increased vulnerability for this group in a poorly managed crisis or recovery period.

Links between LA services, schools and families: managing (and not managing) vulnerability in the community

Headteachers described a clear relationship with LA structures, with limited, but well-defined points of connection. In an approach, which echoes the NHS’s Surge Strategy (PHE, Citation2014), it was noted that social care seemed to close many existing Child in Need plans at the onset of lockdown. The anticipated ‘surge’ failed to materialise however, and it was understood that ‘referrals’ to social care decreased by 50% during lockdown. It was explained that in normal times, the majority of CYP referrals to social care are generated from school-based observations and conversations. With the majority of CYP at home, significant safeguarding issues will be hidden during the lockdown and vulnerable parents, carers, children, and young people will be deprived of crisis support at various times. Societal disruption can sometimes increase the autonomy of children and young people, for example, if chaotic circumstances require them to be more independent (UNICEF, Citation2010). In this case, quarantine reduced opportunities for CYP to voice their needs outside their family. This was a concern for school leaders, and they expressed anxiety about this broken connection in the usual practice framework. ‘It fills me with dread. How do we know these children are safe and well?’

While it seemed that some services were withdrawn or reduced, the cluster-level services - those funded directly by nine primary schools in the area - continue to operate a telephone and virtual service, providing family support and counselling for parents and CYP. In parallel with the school leaders’ experience of home–school partnership the cluster-manager had noticed a greater openness in conversations with parents and carers. It was thought telephone conversations were perhaps less risky for parents/carers, allowing them to feel less exposed and consequently less shamed about needing support. Increased openness and help-seeking may have been a consequence of existential anxiety or increased social solidarity- a sense that ‘everyone is in it together’ (Gaztambide-Fernandez, Citation2020). This pattern of collaboration and cooperation is often seen in disaster situations, especially where there is a pre-existing local structure of support (Thornley et al., Citation2015).

It is important to note that these services have been funded directly by the cluster schools, although the schools themselves are managed by the LA. Academy schools in the area, managed directly by central government, have not commissioned these services. The school-leaders explained that when the quarantine was initiated the LA ‘instructed’ the clusters to make these services available to all schools in the area during the lockdown period. This perhaps highlights a gap in service provision, adjusted for in this situation, in this particular town.

School level

Challenges to school function: whole school adaptations

The uncertainty and disruption experienced during disasters and emergencies can provoke rapid, and creative adjustments. Under the pressure and constraints of this emergency staff (in these schools) found themselves adapting their practice and their professional roles. As previously described, a proactive social-pedagogy was developed through community outreach. Existing monitoring systems (for example, C Poms- a safeguarding software system commonly used in schools), and weekly safeguarding reviews continued alongside education for some in small groups- ‘social-bubbles’.

Some of the issues raised in the focus group converged around the expectation of opening schools to all CYP. The school leaders were in agreement that full opening would require significant relaxation of existing Guidance focussed on preventing virus transmission (the 2 metre social-distance rule and social bubbles were in place at the time the focus group took place). The school leaders expected this Guidance would change in order to facilitate a full return to normal schooling in September (this change occurred on 2 July 2020).

It was the school leaders’ view that ‘missed learning’ would need to be addressed through curriculum adaptation. At the time of writing (July 2020) political and media discourse seems focussed on the need for CYP to catch-up with missed learning (Commons Select Committee, Citation2020). Curriculum has been a prominent and perennial focus in educational discourse and policy, with many educators uncomfortable about increased prescriptiveness regarding the content and delivery as well as the impact of assessment through high stakes testing (Harlen, Citation2014; States of Mind, Citation2020). The school leaders’ discussion focussed on identifying the key concepts and skills required to ensure progression. They were planning for baseline assessment, with a focus on reading, writing, numeracy, physical exercise, and arts/culture activities.

When considering how to identify and support CYP who had experienced adversity during lockdown the school leaders favoured a whole-school strategy designed to provide opportunities for dialogue with CYP and their parents/carers. The recent return of Year 6 groups had shown that while most ‘seemed fine’ it had felt important to make time and space for the children to share their experiences of lockdown, and to talk to parents about how the experience had been for them. It was hoped that this approach would contribute to a supportive school climate, but also help to identify where additional adjustments or interventions might be needed. Plans were being made to access and share training in how to support CYP who have experienced significant loss. It was acknowledged that children do not always talk about their experiences, or their worries and this might isolate them from social support. It was suggested that all schools would need to make emotional well-being and mental health a priority for school development in the coming school year. ‘The well-being of the nation will need to be addressed’.

Individual level

The impact of the pandemic on school leaders’ experience of their role

Government guidance and media communication had a very direct effect upon the school leaders’ experience of their role, and this effect seems relatively unmediated by LA structures (see ). As previously mentioned, they found unclear and frequently changing government guidance stressful to manage. Looking ahead to the new school year, some humorous cynicism was expressed about the scientific basis of current and future policy direction. ‘I think by September this will miraculously no longer be a deadly virus’.

Throughout the pandemic, ethical discomfort had been a feature of their experience, in particular where there were concerns that a policy was unsafe, or not in the best interest of their CYP. They had appreciated the flexibility which guidance had sometimes allowed them - for example, some school leaders had decided to delay the return of early years children until they were comfortable with what they had in place for Y6 children. The school leaders were clear that they expected this ‘flexibility’ to disappear soon and this caused them some anxiety. ‘If guidance I could make a judgment call but if it’s instruction then that’s instantly different, isn’t it?’

The experience of ethical discomfort can compromise a person’s professional identity if there is too great a strain on the frame of meanings (theoretical, practical and moral) in which they locate their practice. With the additional psychological pressure created by the need to continually adapt their practice to changing guidance, school leaders are also at some risk of exhaustion (Akkerman & Meijer, Citation2010; Bhadwaji et al., Citation2020). ‘It’s the relentless thinking’, ‘the planning, then the planning, and the planning’ … … . All the time, even at weekends, even when I am out for a walk with my children’.

Emergent and ongoing problems and risks to staff and pupils

The school leaders anticipated some complex problems arising if schools open fully while the virus is still prevalent in the community. They believed that in these circumstances staff with health issues, and staff who lived with people who needed to shield, would feel very anxious about returning to the school environment. Staff and pupil absence (through illness or anxiety about illness) would be likely to undermine their capacity to reinstate continuous learning.

Narrative formulation and proposals for action

Planning for an increased level of ‘need’ in educational contexts when more CYP return to school

Strengthening of holistic, whole school approaches to ensuring the well-being of CYP and staff will be required

It is not yet clear how quarantine has affected the well-being and learning of CYP, or what support they will require in the coming months: at the time of writing predictions vary from the catastrophic (Carpenter & Carpenter, Citation2020; Roxby, Citation2020) to the sanguine and robust (Bennett, Citation2020; Hattie, Citation2020). Research conducted around previous pandemics is likely to be informative. A study, which surveyed children’s mental health following the SARS outbreak in 2003, estimated PTSD symptoms in 21% of the children affected (Sprang & Silman, Citation2013). However, despite being a similar virus, SARS is considerably more dangerous than Covid-19 (9.5% mortality, as opposed to approximately 1%, with negligible risk from Covid-19 to CYP).

While an intense and potentially traumatising fear of loss of life (Jacobs & Meyer, Citation2006) may not have been commonplace amongst the school community, a significant number of CYP and their families will have experienced adversity as a direct consequence of the lockdown, and for some, lockdown will have exacerbated existing problems. Toxic environmental stress produces mind and body adaptations, which often allow us to cope through a period of crisis, but then cause us difficulties after the immediate crisis has passed. Parents struggling in challenging circumstances, during, and after, the lockdown may be less able to support the development of their children (Charuvastra & Cloitre, Citation2008). Insecure access to basic resources, food and housing has been linked strongly to poor mental health outcomes in CYP following disasters (Beaton and Ledgard, Citation2012) and in rapidly developing economies (Lau & Li, Citation2011). An increase in the psychological issues and challenges, which commonly present around CYP in school might therefore be expected in the coming months. Further disruptions to learning are also possible.

The school leaders were concerned that an increased level of need in the school population would overwhelm existing over-stretched support systems in schools. If support systems are put under strain school exclusions, non-attendance, and school-avoidance would be likely to rise. LA’s will find it very difficult to provide places for excluded, or non-attending CYP in their existing (and already over-stretched) systems and provisions. They suggested that a strategy to prevent this would be needed.

The school leaders in this study were aware of the likely challenges to be faced when more children return to school. They described a range of strategies they were planning across the school to facilitate the transition. It is significant that these were whole school strategies, relationship oriented, and focussed on support that could be provided within school. The senior leaders were applying a holistic model of well-being and mental health in their practice.

Providing the conditions for communication, social connection, and problem-solving, as primary objectives, is consistent with the Psychological First Aid approach applied in disaster management (Mutch, Citation2018; Schafer et al., Citation2015). It is also consistent with whole school approaches to mental-health and well-being recommended by educational psychologists and in some government guidance (PHE, Citation2015). Whole school approaches -‘Nurturing schools’, ‘Attachment-aware’ or ‘Trauma-informed’ (Parker et al., Citation2016) aim to develop a school culture in which emotional de-escalation, problem-solving, respectful communication, and relationship support are highly developed practices. School cultures vary and most adopt a range of strategies. However, many schools, especially at the secondary level, are heavily reliant upon a ‘disciplinary’ approach whereby rewards, sanctions and a measure of social shame (for example, internal and external exclusion) are used to motivate children and young people to conform and co-operate with school rules and adult instructions (DfE, Citation2016). Some schools are keen to apply behaviour policies quite rigidly, adopting a zero-tolerance approach towards, what is often referred to as poor behaviour. It is known that CYP experiencing psycho-social stress tends to be extremely sensitive to the experience of social-shame, and perceived unfairness. They find it especially difficult to cope with sanctions, especially when rigidly applied (Nassem, Citation2019; Oxley, Citation2016).

Across schools, a whole-school approach to mental-health and well-being would be expected to reduce the intensity of psycho-social stress experienced by teachers and children, as well as the need for individualised interventions and support plans (Goldberg et al., Citation2019; Roffey, Citation2016). There are many such frameworks in existence, and they often include screening tools and checklists, which can be used to evaluate systems and assess the well-being of children and staff. In the city of Glasgow, a Universal Nurture Model applied city-wide has been successful in reducing exclusions to very low levels, but this has been achieved in a context in which all schools are funded directly by the LA, and there is a different culture of school evaluation (March & Kearney, Citation2017). In England, 50.1% of the children in state schools attend academies, which are independent of LA structures and directly accountable to the DfE (DfE, Citation2019). Although individual schools may orientate towards a holistic response, a coherent national strategy to address school exclusion and associated issues would require clear leadership, and instruction from central government, if the systemic pressures experienced by school leaders and teachers were to be addressed.

A flexible approach to curriculum and adjustments to school performance evaluation criterion is necessary, to aid ‘recovery’ and manage ongoing disruption

Alongside anxiety about mental health, considerable concern has been expressed at cultural level (politicians and media) about the disruption to learning caused by the pandemic, and the potential deepening of inequalities this might engender long term. The risks so far highlighted have focussed on the need for CYP to catch up on missed learning. The issue of missed learning translates into psychological and emotional risk for children if, when they return to school, they are regularly asked to do work which is too difficult, or to work under pressure for too long. It is known that the experience of too much failure and too much pressure causes anxiety and demotivates. Additional social pressures would intensify this risk, creating further barriers to learning (Ungar, Citation2013). It follows, from this line of reasoning, teachers will need to be free to adjust their expectations of progress, while problems are understood and then addressed.

The school leaders participating in this study seemed aware of these risks and were planning to adjust the curriculum, drawing upon pedagogical and psychological thinking. Ofsted has made it known they will be evaluating schools’ performance in supporting children to catch up. The terms of this evaluation have not yet been shared, and it is not yet clear, at the time of writing, whether schools will be required to follow an unmodified National Curriculum in the event of further significant disruption in Autumn-Winter, 2020–21. There is some risk that politicised understandings of educational purpose and practice, well established in cultural discourse, will be deployed in ways, which polarise this issue.

The school leaders described their commitment to pastoral care at the outset of the pandemic and now view the pastoral dimension of education as fundamental to helping CYP recover from the disruption they have experienced. Although they did not identify what was required from the govt/DfE in this regard, some lessening of performative pressures on children and teachers, and a broader focus on creating the conditions necessary for child development may be required if they are to follow through on this commitment. The issue of curriculum and what to do about missed learning in the context of an ongoing crisis may be a test of the Government’s willingness, at least for a while, to engage with a more holistic range of outcomes and standards.

Planning, governance and communication

Local responses can provide insights required to improve policy and practice

This small-scale study highlights the importance of maintaining school function in a national emergency and the potential for schools to extend their role into the community through social-pedagogical practice. Recovery and resilience-building in the short term may require design and investment in reliable support services, which coordinate around schools at a local level but are well integrated with wider systems. A rigorous evaluative focus on how these services are experienced by children, families, schools, etc. might be considered a ‘stress-test’ for the community resilience required in a disaster context.

Long-term recovery may involve a reconfiguration of the systemic design, in response to the connective breaks that the pandemic exposed (further research is required to identify these breaks). This research highlights the significant role national policy and government guidance has played in shaping services around CYP and families before and during the pandemic. The actions of politicians in the coming months are therefore likely to be crucial in determining what is learned from this pandemic and to what extent this informs pandemic planning.

A plan is urgently needed to secure education and care for all ‘vulnerable’ children

In this particular northern town, in this LA, a level of contact and collaboration continued between families and schools, despite the lockdown. However, the school leaders identified gaps in provision for some vulnerable CYP. Neglect of disabled and marginalised groups is a common pattern in disaster responses (Priestley & Hemingway, Citation2006), and research by advocacy groups confirms that this pandemic was not an exception (Liddiard, Citation2020). A systemic perspective helps us to understand the chain of causes, which create risks for vulnerable CYP. Early in the lockdown, the government passed emergency legislation, which removed (temporarily) LA’s legal obligation to provide appropriate education and care provision for all children with special educational needs, and children in public care. Councils are instead expected to exercise ‘best endeavours’ in this regard (Childrens’ Commissioner, Citation2020a). However, many councils are currently experiencing severe financial strain due to long-term funding cuts and pandemic costs. In this moment, with fewer legal rights and protections, vulnerable CYP are reliant on the capacity of schools, in partnership with parents/carers, to meet their additional needs. Schools themselves are subject to significant systemic pressures, including several years of funding cuts (per pupil), relentless performance management, and now, pressures arising from Covid-19. Government guidance published on the 2nd July (DfE, DfE, Citation2020b) indicates that LA’s should make plans to support CYP who are not accessing education, but this seems to fall short of the multi-systemic understanding of the problem, which this analysis proposes.

Government communication and media representation should be considered a strategic influence on the systems functioning

Behaviour scientists have identified the tone and the content of government ‘messaging’ as a means of generating acceptance for restrictions, a sense of social solidarity and concern for collective well-being (Bavel et al., Citation2020). School leaders in this study struggled with both the tone and the content of government and media communication at times. Clearer and more detailed guidance outlining how a school might seek to function in a quarantine situation might have reduced its workload and stress and this could be usefully addressed by the DfE before further lockdowns take place. A deeper analysis from media outlets of the impact of policy and guidance at the local level may have produced a less toxic and more informative public debate about the role of schools in the pandemic.

This study highlights some precarity in the systems of support around CYP at present, but also the crucial role a school can play in maintaining vital social links with CYP and families, as an everyday practice but also in a whole of society emergency situation. How the government and media represent and engage with education, and educators, is likely to impact on school leaders’ capacity to perform their role. This should be factored into the government’s strategy for a socially cohesive pandemic response.

Conclusion

The principle of interconnected-ness underpinning pandemic preparedness invites a systemic analysis of how the Covid-19 pandemic emergency is being experienced. In this small-scale study, a problem analysis framework applied to the experience of primary school leaders has helped to identify some of the interactions across systemic levels, which occurred in response to the emergency quarantine-lockdown.

In the liminal space created by the partial closing of schools and reduction of social care services a very localised co-ordination of communication emerged between a group (cluster) of primary schools, families, local services and LA statutory services. Consequently, a significant level of pastoral and safeguarding responsibility was exercised despite the quarantine. This response was facilitated by an existing local structure, and this study highlights the value of integrated service provision at the local level while acknowledging the more general precarity and variability of services for children at present in LA’s across the country, the opaque and fragmented funding systems associated with this, and the (currently) reduced protections and entitlements for the most vulnerable in our society.

Although, as I complete this small-study, the first-wave of this pandemic seems to be almost at an end, a second wave is expected, perhaps in the Autumn 2020. A full return for schools is planned for September and talk about second waves and local outbreaks runs parallel to talk of recovery. It is clear our society has been weakened in some ways, and this will impact upon CYP. Schools will need to provide an enhanced level of care and protection for children in the coming months. A national strategy to develop holistic and systemic approaches to well-being and mental health in schools, and flexibility in the delivery of curriculum and evaluation of school performance is recommended in order to maintain school function and ensure the inclusion of vulnerable children and young people. School leaders should be fully involved in planning this, with the government, as respected partners.

This study confirms that schools can contribute effectively to a whole of society emergency quarantine. In a medium-sized northern town, the focus of this study, a promising social-pedagogy seemed to flourish between schools and families, supported by an existing local structure of services. This response requires further exploration to understand more fully its potential as an everyday practice as well as its contribution to societal resilience during a whole of society emergency. It is likely that the quarantine/lockdown inspired many adaptations on the ground across the country, amongst public and private services and voluntary organisations. Further research is needed to identify and understand these liminal responses and how they might inform Government plans for a more resilient society.

Disclosure statement

This research was supported by the University of Sheffield, however, the existing working relationship, between me and the schools participating in this study is acknowledged. I am grateful for the time and attention the school leaders gave to this project.

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful advice and comments offered in the peer review process.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2010). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 27, 308–319 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.013

- Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. University of Chicago Press.

- Annan, M., Chua, J., Cole, J., Kennedy, E., James, R., Markúsdóttir, I., Monsen, J., Robertson, L., & Shah, S. (2013). Further iterations on using the problem-analysis framework. Educational Psychology in Practice: Theory, Research and Practice in Educational Psychology, 29(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2012.755951

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., & Boggio, P. S. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature: Human Behaviour, 4, 460–471 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.

- Beaton, K., & Ledgard, D. (2012). Floods in the United Kingdom: School perspectives. In D. Smawfield (Ed.), Education and natural disasters. Education as a humanitarian response (pp. 108–126). Bloomsbury.

- Bennett, T. (2020). Re-booting behaviour after lockdown,: Advice to schools re-opening in the age of Covid-19, Tom Bennett’s School Report, Accessed 15. 5.20. http://behaviourguru.blogspot.com/2020/05/rebooting-behaviour-after-lockdown.html

- Bhadwaji, A., Byng, C., & Morrice, Z. (2020). A rapid literature review of how to support the psychological well-being of school staff during and after covid-19. Edpscyh@UoB. https://edpsychuob.com/category/mental-health/whole-school-approaches/ doi: Edpsych.com

- Brinkmann, S. (2017). Humanism after posthumanism: Or qualitative psychology after the ‘posts’. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(2), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1282568

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The ecology of developmental processes. In Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

- Bu, F., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the Covid-a9 pandemic in 38,217 UK adults. In Social Science and Medicine The National Library of Medicine () (pp. 265). . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521

- Carpenter, B., & Carpenter, M. (2020). A recovery curriculum: loss and life for our children and schools post pandemic. The Schools, Students and Teachers Network. ssatuk.co.uk. Accessed 1st May, 2020. https://www.ssatuk.co.uk/blog/a-recovery-curriculum-loss-and-life-for-our-children-and-schools-post-pandemic/

- Charuvastra, A., & Cloitre, M. (2008). Social bonds and post-traumatic stress disorder. Annual Review Psychology, 59(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650

- Childrens’ Commissioner. (April, 2020a). Statement on changes to regulations affecting children’s social care. Childrens’ Commissioner for England. Accessed 30. 4.20. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/2020/04/30/statement-on-changes-to-regulations-affecting-childrens-social-care/

- Coe, K., Kuttener, P., Manusheela, P., & Mckasy, M. (2020). The “Discourse of Derision” in news coverage of education: A mixed methods analysis of an emerging frame. American Journal of Education, 126(3 423–445). https://doi.org/10.1086/708251

- Commons Select Committee. (2020). Education Committee holds roundtable on learning catch-up and the impact of school closures, Accessed 28. 5.20. https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/education-committee/news-parliament-2017/impact-of–covid-19-on-education-roundtable-19-21/

- DfE. (2020b). Guidance for full opening of schools. Gov.uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/actions-for-schools-during-the-coronavirus-outbreak/guidance-for-full-opening-schools

- DfE. (2016). Behaviour and discipline in schools;advice for headteachers and school staff. DfE. Accessed 25. 5.20. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/488034/Behaviour_and_Discipline_in_Schools_-_A_guide_for_headteachers_and_School_Staff.pdf

- DfE. (2019). The proportion of pupils in academies and free schools, in England, in October 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-proportion-of-pupils-in-academies-and-free-schools-in-england-in-october-2018

- DfE. (2020a). Supporting Vulnerable Children and Young People during the Coronavirus (Covid-19) Outbreak: actions for educational providers and other partners, Issued 22. 3.20and updated 15. 5.20,Gov.uk. Accessed 23. 3.20. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-vulnerable-children-and-young-people/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-vulnerable-children-and-young-people

- Drabek, C. (1986). Human system responses to disaster: An inventory of sociological findings. Springer-Verlag.

- Fogg, P. (2017). What use is a story? Narrative in Practice. In A. Williams, T. Billington, D. Goodley, and T. Corcoran (Eds.), Critical Educational Psychology. BPS Textbooks, Wiley 34–42 .

- Frederickson, N., & Cline, T. (2009). Special Educational Needs, Inclusion and Diversity. Open University Press.

- Gaztambide-Fernandez, R. A. (2020). What is solidarity? during coronavirus and always, it’s more than ‘we’re all in this together’. The Conversation. theconversation.com, Accessed 13. 4.20. https://theconversation.com/what-is-solidarity-during-coronavirus-and-always-its-more-than-were-all-in-this-together-135002

- Goldberg, J. M., Marcin, S., Elfrink, T. R., Schreurs, K. M. G., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Clarke, A. M. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34, 755–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0406-9

- Gordon, R. (2004). The social dimension of emergency recovery. Appendix C In Emergency Management Australia. Recovery, Australia Emergency Management manuals series No 10, p111-143. Emergency Management Australia.

- Gov.UK. (2018) . Biological Security Strategy: How we are protecting the UK and its interests from significant biological risks. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Department of Health and Social Care, and Home Office.

- Gov.UK. (2020). Coronavirus action plan: A guide to what you can expect across the UK. Dept of Health and Social Care, Dept of Health (NI), Scottish Govt, Welsh Govt. Accessed 3.3.20 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/869827/Coronavirus_action_plan_-_a_guide_to_what_you_can_expect_across_the_UK.pdf

- Hallgarten, J. (2020). Four lessons from evaluations of the education response to Ebola, GPE-Transforming Education, Global Partnership for Education, 4 lessons from evaluations of the education response to Ebola | Blog | Global Partnership for Education educationdevelopmenttrust.com .

- Harlen, W. (2014). Assessment, Standards and Quality of Learning in Primary Education. Cambridge Primary Review Trust.

- Hattie, J. (2020). Will missing a term at school due to covid-19 really matter?: reflections on student performance following the Christchurch NZ earthquake and Hurricane Katrina. New Orleans, Bureau international d’education, UNESCO. www.ibe.unesco.org. Accessed 5. 5.20. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fr/news/will-missing-term-school-due-covid-19-really-matter-reflections-student-performance-following

- Hayes, B., & Frederickson, N. (2008). Providing psychological intervention following traumatic events: understanding and managing psychologists’ own stress reactions. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360802019123

- Herr, K., ., & Anderson, G. C. (2005). The continuum of positionality in Action Research, In The Action Research Dissertation: a guide for students and faculty, SAGE.

- Hodge, N., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2008). Problematising parent–professional partnerships in education. Disability & Society, 23(6), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802328543

- Jacobs, G. A., & Meyer, D. L. (2006). Psychological First Aid: Clarifying the concept. In L. Barbanel & R.J. Sternberg, (Eds). Psychological Interventions in Times of Crisis. New York NY Springer Publishing Co. , .

- Lau, M., & Li, W. (2011). The extent of family social capital promoting positive subjective well-being among primary school children in Schenzhen China. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1573–1582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.03.024

- Liddiard, K. (2020). Surviving ableism in covid times: only the vulnerable will be at risk … .but your ‘only’ is my everything’. i-human group, University of Sheffield. www.sheffield.ac.uk/ihuman. http://ihuman.group.shef.ac.uk/surviving-ablesim-in-covid-times/

- March, S., & Kearney, M. (2017). A psychological service contribution to nurture: Glasgow’s nurturing city. Emotions and Behavioural Difficulties, 22(3), 237–247 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2017.1331972

- Mathers. J., and Kitchen, V. (2020). Beyond Duty: 'Medical Heroes' and the Covid-19 pandemic.Journal of Bioethical Inquiry,17(4), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10065-0

- McCaffrey, T. (2004). Responding to crises in schools: A consultancy model for supporting schools in crisis. Educational and Child Psychology, 21(3), 109–121.

- Ministry of housing, Communities and Local Govt. (2019). English Indices of Deprivation, 2019, Gov.uk, English indices of deprivation 2019: mapping resources - GOV.UK. www.gov.uk

- Moore, J. (2005). Recognising and questioning the epistemological basis of educational psychology practice. Educational Psychology in Practice, 21(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360500128721

- Morgan, G. (2020). Children’s mental health will suffer irreparably if schools don’t reopen soon. The Guardian. Accessed 20.6.20. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/20/childrens-mental-health-will-suffer-irreparably-if-schools-dont-reopen-soon

- Morton, J., & Frith, U. (1995). Causal modelling: A structural approach to developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Wiley series on personality processes. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 1. Theory and methods (pp. 357–390). John Wiley & Sons.

- Moss, P., & Petrie, P. (2019). Education and social pedagogy: what relationship? London Review of Education, 17(3), 393–405 doi:https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.17.3.13.

- Mutch, C. (2018). The role of schools in helping communities cope with earthquake disasters: the case of the 2010-2011 New Zealand earthquakes. Environmental Hazards, 1(4), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2018.1485547

- Mutch, C. (2020). How might research on schools’ responses to earlier crises help us in the covid-19 recovery process? set (2). Research Information for Teachers. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0169

- Nassem, E. (2019). Zero tolerance policies cause anger not reflection. Birmingham City University, School of Education and Social Work. Accessed 15.5.20. https://www.bcu.ac.uk/education-and-social-work/about-us/news-and-events/zero-tolerance-policies-cause-anger-not-reflection

- Newton, P., & Burgess, D. (2008). Exploring types of educational action research: implications for research validity. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(4), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690800700402

- O’Toole, V. (2018). ‘Running on fumes’: Emotional exhaustion and burnout of teachers following a natural disaster. Social Psychology of Education, 21(5), 1081–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9454-x

- Oxley, L. (2016). Emotions and exclusions: how behaviour management in schools can meet emotional needs more effectively. North East Branch Bulletin, (4), 4–12.

- Parker, R., Rose, J., & Gilbert, L. (2016). Attachment Aware Schools: An alternative to behaviourism in supporting children’s behaviour? In H. Lees, and N. Noddings (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Alternative Education (pp. 463-483). Palgrave MacMillan .

- Perkins, D. D., Hughey, J., & Speer, P. W. (2002). Community psychology perspectives on social capital theory and community development practice. Journal of the Community Development Society, 33(1), 33-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330209490141

- PHE. (2014). Pandemic Influenza Response Plan. Public Health England.

- PHE. (2015). Promoting children and young people’s emotional health and wellbeing A whole school and college approach. Public Health England.

- Phillips, S., & Sen, D. (2011). Stress in head-teachers. In J. Langen-Fox, and G. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of Stress in the Occupations (pp. 177-196). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pita, N., & Ehmer, C. (2020). Social capital in the response to covid-19. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(8), 942–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120924531

- Potts, M. (2020). Just me, the bee and the iPad:Listening to stories told by mothers of children with autism who have experienced school exclusion. DEdCPsy thesis, University of Sheffield.

- Price-Robinson, R., & Knight, K. (2012). Natural disasters and community resilience: A framework for support. Child, Family, Community, Australia: Information Exchange, Paper No 3 Australian Institute of Family Studies .

- Priestley, M., & Hemingway, L. (2006). Disability and disaster recovery: A tale of two cities? Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 5(¾), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J198v05n03_02

- Roffey, S. (2016). Building a case for whole-child, whole school wellbeing in challenging contexts. Educational and Child Psychology, 33 (2), 30-42. British Psychological Society.

- Rosiek, L. (2013). Pragmatism and post-qualitative futures. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 692–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788758

- Roxby, P. (2020). Psychiatrists fear tsunami of mental-illness after lockdown. BBC news. Accessed 16.5.20. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52676981

- Schafer, A., Snider, L., & Sammour, R. (2015). Reflective learning report about the implementation and impacts of psychological first aid (PFA) in Gaza. Disaster Health, 3(1 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21665044.2015.1110292), 1-10.

- Sprang, G., & Silman, M. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(1), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

- States of Mind. (2020). ’We’re not learning we’re memorising’- Read London students powerful open letter, States of Mind, accessed January 2021.

- Strong, P. (1990). Epidemic psychology: A model. Sociology of Health & Illness, 12(3), 249-259. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347150

- Thornley, L., Ball, J., Signal, L., Te-Aho, K., & Rawson, E. (2015). Building community resilience: learning from the Canterbury Earthquakes, Kotuitui. New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 10(1), 23–35 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2014.934846.

- UKRI. (2020). Covid-19 research questions-UK research and innovation. Accessed 15.6.20. https://www.ukri.org/files/research-questions-for-covid-19/

- Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 14(3), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805

- UNICEF. (2010). Children of Haiti Report.

- Wang, L., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental healthproblems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18, Article no. 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

- Wignjadiputro, I., Widaningrum, C., & Setiawaty, V. (2020). Whole-of-society approach for influenza pandemic epicenter containment exercise in Indonesia. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(7), 994–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2019.12.009

- Williams, A. (2013). Critical educational psychology: Fostering emancipatory potential within the therapeutic project. Power and Education, 5(3), 304–317. https://doi.org/10.2304/power.2013.5.3.304

- World Health Organisation. (2009). Whole of Society Pandemic Readiness: WHO guidelines for pandemic preparedness and response in the non-health sector. WHO.