ABSTRACT

The changing landscape of higher education and increased prevalence of mental health issues have placed pressure on universities to respond effectively to the needs of an increasingly diverse student body. Whilst higher education institutions provide support services to help students who are encountering difficulties, it often falls to fellow students to offer support. However, peers may lack awareness and knowledge about how to intervene or be reluctant to intervene due to the ‘bystander effect’ that diffuses responsibility for action in group settings. This article describes an initiative called Seas Suas, a programme developed by the Chaplaincy at an Irish university that encourages students to be more aware and observant of challenging issues impacting other students’ academic and personal lives and to equip them with the knowledge and skills to respond appropriately. A mixed methods research design was undertaken to assess outcomes from the programme (N = 193). Findings indicate that students showed higher levels of empathy, social responsibility and confidence in helping others after participating in the Seas Suas programme. The implications of the findings for pastoral care in higher education are discussed.

Introduction

Pastoral care is the term used in education to describe the structures, practices and approaches to support the welfare, well-being and development of students (Calvert, Citation2009). While Seary and Willans (Citation2020) note that there is scant literature relating to the concept of pastoral care in higher education contexts, there is considerable evidence that having a caring environment is integral to student satisfaction and success (Motta & Bennett, Citation2018). Performance and retention are enhanced where the educational environment is perceived as welcoming, where students feel a sense of belonging and feel valued by the institution (Bruning, Citation2002; Bryson & Hand, Citation2007; Murphy & Holste, Citation2016).

It can be argued that pastoral care initiatives are needed now more than ever at third level as participation rates have increased over recent decades, with higher education transformed from an elite to a mass experience (Côté, Citation2014). As participation rates have grown, the student body has become much more diverse, with increases in students with disabilities, international and migrant students, and students from socio-economically disadvantaged groups (HEA, Citation2018; Scriver et al., Citation2021). At the same time, funding pressures have resulted in larger class sizes and faculty-student ratios, making it less likely that students will have opportunities to build informal mentoring relationships with teaching staff and engage with other students (Maharaj et al., Citation2021).

A concurrent issue of growing concern is the increased prevalence of mental health issues among young people, including students. A large-scale national study of youth mental health in Ireland, the My World Survey (Dooley et al., Citation2019), found that 58% of the young adult sample (aged 18–25) suffered from depression, with a similar percentage experiencing anxiety. Rates of depression and anxiety had increased since a similar survey undertaken in 2012 (Dooley & Fitzgerald, Citation2012), whilst levels of protective factors such as self-esteem, optimism and resilience had decreased. In terms of coping with stressors, ‘friends’ was the most common strategy used with 56% of the sample saying they talk to friends as a coping mechanism (Dooley et al., Citation2019). Initial research findings suggest that these trends have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, whereby social distancing measures and the pivot to emergency remote teaching have increased stress and isolation among students (Flynn et al., Citation2021).

Higher education institutions provide support services to help students who are encountering difficulties, and students are generally encouraged to access these services when they need them. Early intervention services that help students to deal with difficulties in their lives, experience a stronger sense of belonging in the institution and progress through their academic courses yield benefits for students, their families and the academic institution. These benefits include financial savings, better psychological well-being and reduced teaching and administrative burden (Seary & Willans, Citation2020). However, despite information about these services often being widely available, not all students in need will access them due to lack of awareness or reticence related to help-seeking (Cameron & Siameja, Citation2017). Furthermore, Seary and Willans (Citation2020) argue that neo-liberal values of individualism, managerialism, measurement and accountability take precedence over care in higher educational contexts (Macfarlane, Citation2020; Motta & Bennett, Citation2018; Mutch & Tatebe, Citation2017; Zepke & Leach, Citation2010). Mutch and Tatebe (Citation2017) argue that it is imperative to counter this competitive and individualising regime by creating a culture of care and compassion in third-level institutions.

In this article, evaluation findings are outlined in relation to an initiative developed by the Chaplaincy at an Irish University to raise awareness among students of challenging issues impacting the academic and personal lives of their peers and to equip them with the knowledge and skills to respond appropriately. The programme aims to encourage peer support and create a culture of care and compassion among and between students. Before describing the initiative, the theoretical framework for the project and the study is introduced.

Theoretical framework

Empathy is commonly understood as one’s ability to feel and understand the emotions and feelings of others (Bernhardt & Singer, Citation2012; Duan & Hill, Citation1996; M.H. Davis, Citation2018). Empathy is thought to provide the foundation for broader societal attitudes and behaviours, such as social responsibility and prosocial or civic behaviour that reflects an individual’s interest in the ‘greater good’ or their concern for the welfare of others (Silke et al., Citation2018; Da Silva et al., Citation2004; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2015). A significant body of research has found that greater levels of empathy and ‘other-oriented’ values and behaviours are associated with positive personal, interpersonal, and societal benefits including cognitive and emotional development, academic performance, psychological well-being and better quality relationships (Jenkinson et al., Citation2013; Martela & Ryan, Citation2016). There is evidence that empathic attitudes and values lead to greater interpersonal helping and also promote helping, which is more responsive and attuned to the other person’s needs (Batson et al., Citation2004; Carlo et al., Citation2010). However, it has been claimed that individualism and narcissism have increased among the younger generations in society, leading to less empathy and concern for others (Twenge & Campbell, Citation2012). For example, Konrath et al. (Citation2011) found that empathy declined over time among American college students with declines in perspective taking and empathy becoming more pronounced in samples from 2000 onwards. Because the development of empathy is heavily influenced by the culture and environment, the move to a more individualised, meritocratic, globalised and technology-based society might have undermined historical processes of emotional socialisation. For example, the advent of 24/7 news and celebrity social media feeds can lead to ‘empathy fatigue’ whereby it is difficult to empathise with people in need at a global level.

Furthermore, while empathy is a foundational skill, there is evidence to suggest that feeling empathy towards a person or group will not automatically lead a person to intervene to help (Silke et al., Citation2019a). Researchers have identified that empathetic and compassionate people can be inhibited from acting due to a fear of causing offence, making the situation worse or not knowing how best to help. The concept of the ‘bystander effect’ was developed following the failure of bystanders to intervene during the rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in Central Park, New York, in 1964. Darley and Latané (Citation1968) found that people are prevented from helping due to fear of making a mistake and being judged negatively by others if they intervene and feeling less personal responsibility when a number of other potential helpers are present. Furthermore, bystanders tend to rely on the reactions of others to determine if the situation represents an emergency – if others do not react, the individual may be less likely to see the situation as an emergency (Fischer et al., Citation2011).

While students are well placed to provide timely support to friends, family and indeed strangers, the potential for helping can be undermined by the ‘bystander effect’ that diffuses responsibility for action in group settings (Darley & Latané, Citation1968). Bystander programmes aim to increase bystanders’ prosocial behaviours and willingness to intervene in situations that could potentially result in harm (Borsky et al., Citation2018; Salmivalli, Citation2014). Participants are sensitised to warning signs of emerging issues or problems, encouraged to develop empathy for the individual and responsibility to act and encouraged to take action. Programmes also aim to build the skills for intervening and impart the skills or approaches required for taking action (Banyard and Moynihan Citation2011; Darley & Latané, Citation1968; Kettrey & Marx, Citation2019). Such programmes have become increasingly deployed in educational settings to prevent sexual assault and dating violence, cyberbullying and other online harms (e.g. UUK Bystanders Project) and bullying (Salmivalli, Citation2014). Studies of bystander programs have found beneficial effects on participants’ self-efficacy and intentions to intervene and rates of intervention (Katz & Moore, Citation2013; Kettrey & Marx, Citation2019).

Programme overview

From 2012 onwards, student services at the authors’ university were becoming increasingly aware of issues related to student well-being, including mental health issues and negative consequences associated with alcohol and drug misuse. The impact on students was often significant, including academic failure, emotional distress, serious injury and suicide. A need for increased awareness raising and training among students was identified. The ‘Seas Suas’ (which means ‘stand up’ in Gaelic) programme was developed in 2014 as a collaborative initiative by the Chaplaincy Service, the Student’s Union, and the Director of Student Services to encourage students to be proactive in helping fellow students.

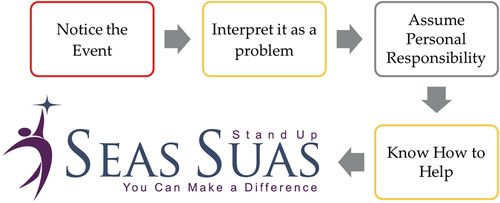

The aim of the Seas Suas programme is to motivate students to be more aware and observant of challenging issues impacting students’ academic and personal lives and to equip them with the knowledge and skills to intervene appropriately. In doing so, it aims to foster a culture of care and support within the university community and beyond. It is informed by Darley and Latané’s (Citation1968) Bystander Intervention Model and the Life Skills Programme in the University of Arizona. While the programme explicitly addresses challenging issues faced by students, the character of the programme is holistic with a specific focus on health and well-being.

A range of contemporary student concerns are explored in the training programme such as alcohol, drugs, suicide, mental health, emotional balance, relationships, and positive peer-group activities. The programme provides students with information and skills to negotiate a range of challenging situations successfully. Training includes gaining knowledge about challenging issues and corresponding supports, developing strategies for effective helping, and learning skills to intervene safely or refer appropriately.

Students who undertake the training attend four consecutive training sessions, each lasting 2 hours. During session 1, the Seas Suas bystander intervention model is introduced. As depicted in , participants are encouraged to ‘notice’ specific issues of concern affecting peers in their social environment (e.g. mental health issues, substance misuse) and to interpret whether or not there is a problem. If there is a problem, they are encouraged to assume personal responsibility in addressing the problem and to intervene effectively. Two specific themes or topics are then covered during each subsequent session by experts in each field (e.g. suicide awareness, sexual consent, mental health, drugs awareness) to raise awareness of issues affecting students and the range of services available. Each training session includes interactive engagement, reflective practice and opportunities for a practical application of their learning. In the final session, the Seas Suas model is revisited with real-life scenarios used to illustrate issues that may arise on campus, at home or in social settings and practical steps that can be taken to intervene (for example, using the appropriate language for crisis intervention and referring to support services). Following completion of the programme, participants complete a reflective journal and are encouraged to put their learning into action in their everyday lives. Participants can also contribute to a number of specific events such as Mental Health Week, the Green Ribbon Campaign, helping with the Exam Support Team and assisting with Student Orientation Week. Participants receive an accredited certificate for student volunteering from the university President.

Seas Suas is run twice over the course of each academic year. One programme is carried out in Semester 1, and a duplicated version of the programme is run during Semester 2 with a new group of participants. Participants in the programme are recruited on a voluntary, self-select basis. For the last number of years, approximately 500 students have participated in the programme each year. During 2020–21 academic year, the programme was run online on a reduced basis, involving 50 students in each cohort. Since its inception, approximately 3,000 students have participated in the programme.

Methodology

The aim of the current study is to investigate whether participation in the Seas Suas bystander intervention programme is associated with higher levels of empathy, social responsibility values, and prosocial/civic engagement among third-level students. The research also aims to explore whether participation in the Seas Suas programme is associated with an increased sense of belongingness at the University.

A survey research design was used to quantitatively and qualitatively explore the impact that participation in the Seas Suas programme had on students’ outcomes over time. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee at the authors’ institution in August 2019.

All students who had registered for the Seas Suas programme during Semester 1 of the 2019–2020 academic year were provided with detailed information about the research and invited to participate in the study on an informed consent basis. All students who agreed to participate were asked to complete an online survey approximately 1 week prior to the commencement of the programme (Time 1 survey). The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete. Once students had completed the programme, they were asked to complete a second online survey (i.e. Time 2 survey), which included the same outcome measures as the Time 1 survey. The outcomes were assessed at both time points in order to evaluate changes in students’ knowledge, skills and/or behaviour over time (e.g. before and after Seas Suas participation). The Time 2 surveys also included a set of open-ended questions, which explored students’ perceptions of how the programme had/had not impacted them; what they liked/disliked about the programme; and their recommendations for how the programme could be further improved.

Measures

In the survey, students were asked to respond to questions exploring their sense of belonging and connection to the university and their other-oriented values, including empathy, prosociality and confidence in helping others (see ).

Table 1. Overview of outcomes and measurements included in the research study.

Knowledge of student issues and support services: One of the aims of the Seas Suas programme is to raise awareness among students of the issues facing students and of the services available to students to provide support in relation to these issues. Prior to participating in Seas Suas (Time 1), respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they felt informed about the following topics: Sexual Consent; Alcohol and Substance Abuse; Suicide Prevention and Mental Health. Respondents were also asked to indicate how informed they felt about these same topics after they had participated in the programme (Time 2). Respondents rated their understanding of each topic on a scale from 1 (not at all informed) to 10 (very informed). Respondents were also asked to indicate how knowledgeable they felt about the type of support services that are available for students. Respondents rated the level of their knowledge on a scale from 1 (not at all knowledgeable) to 10 (very knowledgeable), at both time points.

Sense of Belongingness: The Seas Suas programme aims to create a welcoming and nurturing environment for students to enhance their sense of being cared for by the university and by others. The Sense of Belongingness in Higher Education (Yorke, Citation2016) sub-scale was used to assess the degree to which respondents felt they belonged at their university. Respondents rated their sense of belongingness on this six-item scale at both Time 1 and Time 2. The scale ranged from 1 to 24, where higher scores are indicative of higher levels of belongingness.

Confidence/Progression in University studies: It was hypothesised that students may feel more confident in their academic ability and be more likely to stay in college as a result of taking part in the Seas Suas programme. Respondents’ confidence in their academic ability was assessed using the Yorke (Citation2016) Self-Confidence sub-scale. Respondents rated how confident they felt in their ability to succeed in their chosen course of study at both Time 1 and Time 2. The scale consists of four items and ranges in scores from 1 to 16.

Two additional single-item questions were employed to assess respondents’ intentions of remaining in third-level education. Specifically, at both Time 1 and Time 2, respondents were asked to indicate, using a Likert-type scale, the extent to which they were looking forward to another semester at college and to rate their intentions of completing their current course/degree.

Empathy: Respondents’ cognitive and affective empathy were assessed using the Perspective Taking and Emotional Concern sub-scales from the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; M. H. Davis, Citation1980). The Emotional Concern scale assessed respondents’ ability to affectively share the emotions and feelings of others, while the Perspective Taking scale assessed respondents’ ability to understand the emotions and feelings of others. Each scale consists of seven items and ranges in scores from 1 to 35. Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of cognitive and affective empathy.

Prosociality: Respondents’ prosocial behaviours and intentions at Time 1 and Time 2 were measured using the 16-item Caprara et al. (Citation2005) Prosocialness scale. This scale ranges from 1 to 80, where higher scores are indicative of higher levels of prosociality.

Social Responsibility: In order to assess respondents’ social responsibility values the Flanagan and Tucker (Citation1999) Social Responsibility Values scale was employed. This scale consists of six items where respondents rate how important various social values (e.g. helping those less fortunate; helping my society) are to them. The scale ranges from 1 to 30, where higher scores are indicative of more positive social responsibility values.

Competence/confidence in helping others: Respondents’ perceived self-efficacy was assessed at Time 1 and Time 2 using the Perceived Empathic Self-Efficacy scale (PESE; Di Giunta et al., Citation2010). The PESE is a six-item scale, which assesses respondents’ ability to recognise other people’s emotions and identify when another person needs help. The scale ranges from 1 to 30, where higher scores represent a greater perceived ability to read/help others.

Self-Esteem: Self-Esteem was assessed using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (CitationRosenberg). This scale assesses the extent to which respondents’ feel capable and confident in themselves (e.g. I am able to do things as well as most other people). The scale ranges from 1 to 40, where higher scores are indicative of higher self-esteem levels.

Sample

A total of 193 individuals (164 females, 28 males, and 1 other) provided individual survey responses at Time 1 (i.e. prior to the commencement of the Seas Suas programme). All respondents were aged between 17 and 58 years, with an average of 22 years of age (M = 22.23; SD = 5.48). Of the 193 respondents who completed surveys at Time 1, 122 (102 females, 19 males, and 1 other) individuals also returned completed surveys at Time 2. All Time 2 surveys were completed within 2 weeks of the respondent completing the programme. Time 1 and Time 2 surveys were completed approximately 4–6 weeks apart.

Analysis

Respondents’ Time 1 survey responses were compared to their Time 2 responses across the outcome variables assessed. A series of descriptive statistics and t-test analyses were used to identify whether students showed changes in any of these outcome variables after having participated in the Seas Suas programme. All analyses were conducted in SPSS v.24.

Results

A series of preliminary and main analyses were conducted on the data.

Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses were carried out to examine whether there were differences in participants’ knowledge of student issues before and after taking part in Seas Suas. A series of paired samples t-tests were carried out to examine mean differences in responses over time. Results indicated that respondents showed significant increases in their understanding on these topics after participating in Seas Suas, even after controlling for the family-wise error rate (see ).

Table 2. Mean differences in students’ understanding of sexual consent, alcohol and substance abuse, suicide prevention and mental health topics before and after participating in Seas Suas.

Respondents were also asked to indicate how knowledgeable they felt about the type of support services that are available for students. Respondents rated the level of their knowledge on a scale from 1 (not at all knowledgeable) to 10 (very knowledgeable), at both time points. Results from the paired samples t-test showed a significant increase (t(118) = −14.88, p < .001) in knowledge from Time 1 (M = 5.52; SD = 2.11) to Time 2 (M = 8.24; SD = 1.32).

Main analyses

In order to control for the familywise error rate, a Bonferroni correction was performed on all individual analyses conducted. This resulted in a new, more cautious alpha level (p ≤ .005), which is the level of significance accepted in the current research. A summary of findings for each individual outcome is displayed below. Descriptive statistics for all outcomes at Time 1 and Time 2 are presented in . As can be seen in , participants reported moderate-to-high scores on all measures at Time 1 and Time 2 and all scales showed adequate internal consistency.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics, including mean (M) and standard deviations (SD), for all outcome variables measured at Time 1 (Pre-Intervention) and Time 2 (Post-Intervention).

Belongingness

Although respondents showed relatively high levels of perceived belongingness at both Time 1 (M = 20.33; SD = 2.98) and Time 2 (M = 20.54, SD = 3.03), results from the paired samples t-test showed that there were no significant differences (t(118) = −1.06, p = .29) between respondents’ sense of belongingness at Time 1 and Time 2.

Confidence/progression in university studies

While respondents showed high levels of perceived confidence at both Time 1 (M = 11.45; SD = 2.43) and Time 2 (M = 11.76; SD = 2.31), results from the paired samples t-test indicated that there were no significant differences (t(118) = −1.53, p = .13) between respondents’ confidence in their academic ability at Time 1 and Time 2.

Results indicated that there were no significant differences in either respondents’ intentions to complete their degree (t(118) = .37, p = .71) or the extent to which they were looking forward to another semester (t(118) = −.82, p = .42), from Time 1 to Time 2.

Empathy

Respondents rated both empathic abilities at Time 1 and Time 2. Results from the paired samples t-test indicated that respondents showed significantly higher levels of both cognitive t(108) = −8.91, p < .001, d = 2.79) and affective (t(108) = −23.30, p < .001, d = .98) empathy after taking part in the Seas Suas programme. Specifically, while respondents were found to express moderate levels of affective (M = 21.61; SD = 2.51) and cognitive (M = 23.91; SD = 2.95) empathy at Time 1, they showed significantly higher levels of affective (M = 30.27; SD = 3.60) and cognitive (M = 27.44; SD = 4.13) empathy at Time 2.

Prosociality

Results from the paired samples t-test indicated that, after applying a Bonferroni correction, respondents showed no significant changes in prosociality t(108) = −2.74, p = .007, d = .23) over time. In other words, respondents were found to express similar levels of prosociality at Time 1 (M = 65.06; SD = 8.01) and Time 2 (M = 66.88; SD = 7.68)

Social responsibility

Results from the paired samples t-test revealed that respondents expressed significantly t(108) = −2.85, p = .005, d = .25) more positive social responsibility values after taking part in the Seas Suas programme. However, it should be noted that although significant, the change from Time 1 (M = 23.87; SD = 3.19) to Time 2 (M = 24.68; SD = 3.21) was small.

Competence/confidence in helping others

Results from the paired samples t-test indicated that respondents showed significant t(108) = −5.85, p < .001, d = .53) changes in their self-efficacy after having taken part in the Seas Suas programme. Specifically, respondents’ showed significantly higher levels of perceived empathic self-efficacy at Time 2 (M = 24.58; SD = 3.14) than they did at Time 1 (M = 22.85; SD = 3.35).

Self-esteem

Results from the paired samples t-test showed that respondents showed significant (t(106) = −2.19, p = .004, d = .19) differences in their self-esteem scores between Time 1 (M = 28.37; SD = 5.46) and Time 2 (M = 29.48; SD = 6.03)

Perceived impact of the Seas Suas programme

Once the Seas Suas programme was complete (i.e. Time 2), respondents were also asked a number of questions examining the perceived impact (if any) that the programme had for them personally. A total of 95 participants responded to the open-ended question regarding the perceived benefits of the Seas Suas programme. From these responses, a number of perceived advantages appeared to be commonly discussed. First, several respondents reported feeling more knowledgeable about student issues and how to help others after taking part in Seas Suas. Respondents also reported feeling more informed about the support services that are available for those in need.

“I gained more insight to effective ways of helping others”

“I was made more aware of problems and their warning signs, and what I can do as a bystander in situations”

Similarly, respondents discussed how taking part in Seas Suas helped make them more aware of others and be more considerate of the issues that other people may be dealing with.

“From taking part in Seas Suas, I feel I am more aware of my surroundings and the people around me. I am more inclined to notice those unwell or distressed looking”

“I am definitely more conscious and aware of assessing social situations, and I try and keep more of a keen eye out for those who might be vulnerable or in need of help”

A large number of respondents suggested that the Seas Suas programme helped them to build confidence in their ability to help others and has made them feel more comfortable in intervening or more willing to help/volunteer.

“The biggest benefit for me was to gain confidence in intervening in a potentially hazardous situation when before I would have been less likely due to the bystander effect”

“Seas Suas helped me to break the barrier from just being a bystander. Now, I will act if I see someone struggling be it a stranger or a friend. Now I have the tools to do it whereas before I did not know what to do”

A small number of respondents also appeared to personally benefit from taking part in the programme, referring to how the programme helped increase their ‘self-awareness’ or made them feel ‘happier’ and discussed how they enjoyed being part of a ‘community of helpers’.

Perceptions of the Seas Suas programme

After having completed Seas Suas (i.e. at Time 2), respondents were asked to answer a series of questions exploring their perceptions of the programme. Asked what they liked most about the programme, the majority of respondents commented on ‘the quality of the speakers’. Respondents noted that they found the speakers to be ‘engaging and interesting’ and appeared to like the variety of topics covered over the course of the programme. Additionally, respondents commented on how the talks were delivered. In particular, respondents appeared to like engaging in the ‘interactive discussions’ and ‘mature conversations’ with others on these topics. Several respondents also commented on the quality of the information shared, noting that they found the programme to be applied, informative, and eye-opening.

‘The variety of talks provided and how they helped raise awareness of a number of issues, while always driving home the fact that YOU can make a difference, and to be that one person who makes an effort to help.’

Other elements commonly noted as being ‘liked’ by respondents included the ‘enthusiasm of the hosts’, the ‘positive atmosphere’, and the ‘sense of togetherness’.

‘There is a positive, uplifting, light atmosphere despite dealing with heavy or taboo issues’

‘Incredibly supportive organisers and the right atmosphere’

The most common suggestions for how Seas Suas could be improved included expanding the time/length of the programme and including more interactive elements. A small number of respondents suggested that the programme could be improved by providing more ‘practical advice on how-to’ and recommended including more information about further training initiatives or volunteering opportunities for each of the subjects included in the Seas Suas programme. A few respondents also suggested involving those with lived experience in the programme and including their voice in the discussion.

In addition to the above recommendations, respondents were also asked to indicate, on a yes or no basis, whether or not they would recommend the current Seas Suas programme to a friend. In total, 99% (n = 108) of respondents indicated that they would recommend this programme to a friend, only one respondent (1%) reported that he/she would not recommend the programme.

Discussion

The changing landscape of higher education has placed significant constraints on the degree to which staff can build respectful and reciprocal relationships with students (Motta & Bennett, Citation2018). Pastoral care and student services struggle to respond effectively to the needs of an increasingly diverse student body. In these contexts, universities are seeking innovative ways to support students within the institutional and bureaucratic constraints under which they operate. Peer support models have become increasingly popular over recent years and have been successfully used at third level to enhance academic performance (Scriver et al., Citation2021). By having a greater ‘reach’ than professionally led models of support, peer support interventions facilitate students to receive support in the context of their day-to-day interactions, rather than formally through designated support staff (Brady et al., Citation2014; Houlston et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, research findings suggesting that the key mechanism used by young adults to cope with stressors is ‘friends’ (Dooley et al., Citation2019) provide a rationale for enhancing the capacity of peers to provide effective support.

This article describes an initiative developed in an Irish institution to raise awareness, empathy and helping among third-level students. Findings from an initial evaluation of the initiative indicate that participation in the programme is associated with several positive outcomes. Results from the quantitative analyses revealed that participants showed significantly higher levels of empathy and self-esteem, expressed more positive social responsibility values, and felt more confident in their skills to help/understand others after taking part in Seas Suas. In addition, respondents appeared to believe that participation in the programme was associated with a number of benefits, attributing increases in their knowledge of student issues, awareness of others in need, willingness to help others, and confidence in their ability to intervene to their participation in the Seas Suas programme. Overall, respondents appeared to enjoy the programme, with the quality of speakers, the variety of topics covered, and the interactive nature of the programme being identified as particular highlights. Participant feedback regarding possible improvements is valuable in terms of informing the future development of the programme.

The findings from the study indicate that this programme appears to have been successful in increasing empathy among students, which is likely to have implications for a wide range of domains. A strong research base attests to the crucial role that empathy, social responsibility, and civic engagement play in promoting personal development, strengthening interpersonal relationships, and enhancing societal well-being (Hylton, Citation2018; Rossi et al., Citation2016; Da Silva et al., Citation2004). While individuals can have high levels of empathy, they can be reluctant to act for a series of reasons known as the ‘bystander effect’ (Darley & Latané, Citation1968; Silke et al., Citation2019a). These psychological factors that inhibit action were specifically targeted by the programme and the indications from the study are that students feel more confident and skilled in terms of their ability to help others. These findings are in line with evidence from studies of bystander programs, which have found positive impacts on participants’ self-efficacy and intentions to intervene (Kettrey & Marx, Citation2019). Similarly, studies of peer support programmes have found that providing training to students to care for fellow students helps to create a culture of care, whereby people are given ‘permission’ to notice the needs of others and take action (Brady et al., Citation2014; Cowie, Citation2011).

It is interesting to note that the programme was most successful with regard to ‘other oriented’ values but no increases were found in measures related to belongingness to the university, and confidence in academic ability and intention to progress in their academic studies. These findings are contrary to those found in the body of literature in relation to pastoral care, namely that pastoral care enhances student identification with the university and supports academic performance (Murphy & Holste, Citation2016). It is possible that because the programme was provided by the Chaplaincy, rather than by the students’ own faculty, students viewed it as something apart from their academic role. Nonetheless, the study findings provide valuable guidance to the programme managers regarding the aspects of the programme that are impacting students’ knowledge and attitudes, enabling a further fine-tuning of the theoretical processes underpinning the programme. As the initiative is at an early stage of development, it will be important to explore these concepts further in future studies through use of more targeted measures and studies tracking the longer-term impact of the programme. For example, future studies could explore the impact of the initiative on the actual helping behaviour of participants, in addition to values. The impact of the initiative on the wider student population and host institution, including student engagement, retention and performance and use of support services would be other important dimensions to explore.

It could be argued that initiatives of this nature can be seen as feeding into the neo-liberal agenda that has come to dominate in higher education institutions, pushing the responsibility for care back to students and absolving the university of their duty to care for students (Baice et al., Citation2021; Macfarlane, Citation2020). While this argument has merit, it is important to note that one of the outcomes of this initiative is likely to be an increased take-up of university support services for students, due to greater awareness of available services and increased efficacy in terms of knowing how to help, which includes referring others to the appropriate service. Furthermore, there is considerable evidence that social contexts (e.g. peers and communities) play a critical role in the socialisation of youth’s empathic attitudes and civic behaviours (Silke et al., Citation2019b). Creating spaces in the university where students feel nurtured and cared for, is likely to have ripple effects in terms of a more engaged and connected student body capable of advocating for the needs and rights of students, and providing a counterpoint to competitive and individualising forces (Hylton, Citation2018; Murphy & Holste, Citation2016; Mutch & Tatebe, Citation2017).

While the findings are promising, two key limitations of the study must be acknowledged. First, while the pre- and post-design enabled us to compare differences in students’ outcomes before and after their participation in the Seas Suas initiative, the absence of a control group means that non-programme influences on outcomes cannot be ruled out (Stufflebeam & Coryn, Citation2014). In future studies, it will be important to include a pre- and post-design with a comparison group to provide assurances that the outcomes observed have occurred as a result of the programme. However, such a study design will be challenging in terms of the time and resources required to recruit and retain a comparison group. Second, it should also be noted that results are based on a single programme undertaken at a single institution and may not generalise to other contexts. Other limitations of note are the limited sample size and reliance on self-report measures.

Conclusion

Bystander programmes, which aim to increase willingness to intervene in situations that could potentially result in harm, have become popular in third-level institutions. This article has described the Seas Suas programme, an innovative new programme developed by the Chaplaincy at an Irish university to encourage bystander intervention in relation to a broad range of issues impacting students' personal and academic lives. An initial evaluation of the programme found that participants showed higher levels of empathy, social responsibility and confidence in helping others.

It can be argued that programmes of this nature can play a role in building a culture of care and compassion among students. Baice et al. (Citation2021) argue that it is essential for Higher education institutions to move beyond seeing care as something that is provided in the context of ‘service delivery’. They argue in favour of a relational approach to care, recognising the connectedness between people and between people and their environments. The Seas Suas initiative can be seen as a model of how higher education institutions can promote relational approaches to care, communicating to students that they are not alone and that they have the power to help fellow students and humans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baice, T., Fonua, S. M., Levy, B., Allen, J. M., & Wright, T. (2021). How do you (demonstrate) care in an institution that does not define ‘care’? Pastoral Care in Education, 39(3), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2021.1951339

- Banyard, V., & Moynihan, M. (2011). Variation in bystander behavior related to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention: Correlates in a sample of college students. Psychology of Violence, 1(4), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023544

- Batson, C. D., Ahmad, N., & Stocks, E. L. (2004). Benefits and liabilities of empathy-induced altruism. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (pp. 359–385). The Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-16379-014

- Bernhardt, B. C., & Singer, T. (2012). The neural basis of empathy. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150536

- Borsky, A. E., McDonnell, K., Turner, M. M., & Rimal, R. (2018). Raising a red flag on dating violence: Evaluation of a low-resource, college-based bystander behavior intervention program. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(22), 3480–3501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516635322

- Brady, B., Dolan, P., & Canavan, J. (2014). What added value does peer support bring?: Insights from principals and teachers on the utility and challenges of a school based mentoring programme. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(4), 241–250. December 2014. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2014.960532

- Bruning, S. D. (2002). Relationship building as a retention strategy: Linking relationship attitudes and satisfaction evaluations to behaviour. Public Relations Review, 28, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00109-1

- Bryson, C., & Hand, L. (2007). The role of engagement in inspiring teaching and learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(4), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290701602748

- Calvert, M. (2009). From ‘pastoral care’ to ‘care’: Meanings and practices. Pastoral Care in Education, 27(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940903349302

- Cameron, M. P., & Siameja, S. (2017). An experimental evaluation of a proactive pastoral care initiative within an introductory university course. Applied Economics, 49(18), 1808–1820. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1226492

- Caprara, G. V., Steca, P., Zelli, A., & Capanna, C. (2005). A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.21.2.77

- Carlo, G., Mestre, M. V., Samper, P., Tur, A., & Armenta, B. E. (2010). Feelings or cognitions? Moral cognitions and emotions as longitudinal predictors of prosocial and aggressive behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(8), 872–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.010

- Côté, J. (2014). Youth studies: Fundamental issues and debates. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Cowie, H. (2011). Peer support as an intervention to counteract bullying: Listen to the children. Children and Society, 25(4), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00375.x

- Da Silva, L., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Toumbourou, J. (2004). Civic responsibility among Australian adolescents: Testing two competing models. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3), 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20004

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4, Pt.1), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025589

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85. https://www.uv.es/~friasnav/Davis_1980.pdf

- Davis, M. H. (2018). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Routledge.

- Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Tramontano, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2010). Assessing perceived empathic and social self-efficacy across countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000012

- Dooley, B. A., & Fitzgerald, A. (2012). My world survey: National study of youth mental health in Ireland. Headstrong and UCD School of Psychology. Retrieved October 9, 2021 https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/bitstream/10197/4286/1/My_World_Survey_2012_Online%284%29.pdf

- Dooley, B. A., O’Connor, F. A., & O’Reilly, A. (2019). My world survey 2: The national study of youth mental health in Ireland. Jigsaw and UCD School of Psychology. Retrieved August 27, 2021, from http://www.myworldsurvey.ie/full-report

- Duan, C., & Hill, C. E. (1996). The current state of empathy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(3), 261. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.3.261

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023304

- Flanagan, C. A., & Tucker, C. J. (1999). Adolescents’ explanations for political issues: Concordance with their views of self and society. Developmental Psychology, 35(5), 1198. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1198

- Flynn, N., Keane, E., Davitt, E., McCauley, V., Heinz, M., & Mac Ruairc, G. (2021). Schooling at home’ in Ireland during COVID-19’: Parents’ and students’ perspectives on overall impact, continuity of interest, and impact on learning. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558

- HEA. (2018). Progress review of the national access plan and priorities to 2021.

- Houlston, C., Smith, P. K., & Jessel, J. (2009). The relationship between use of school-based peer support initiatives and the social and emotional well-being of bullied and non-bullied students. Children and Society, 25(4), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00376.x

- Hylton, M. E. (2018). The role of civic literacy and social empathy on rates of civic engagement among university students. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 22(1), 87–106,1534-6102.

- Jenkinson, C. E., Dickens, A. P., Jones, K., Thompson-Coon, J., Taylor, R. S., Rogers, M., Bambra, C. L., Lang, I., & Richards, S. H. (2013). Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 773. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-773

- Katz, J., & Moore, J. (2013). Bystander education training for campus sexual assault prevention: An initial meta-analysis. Violence and Victims, 28(6), 1054–1067. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00113

- Kettrey, H. H., & Marx, R. A. (2019). The effects of bystander programs on the prevention of sexual assault across the college years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(2), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0927-1

- Konrath, S., O’Brien, E., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377395

- Macfarlane, B. (2020). The CV as a symbol of the changing nature of academic life: Performativity, prestige and self-presentation. Studies in Higher Education, 45(4), 796–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1554638

- Maharaj, C., Blair, E., & Burns, M. (2021). Reviewing the effect of student mentoring on the academic performance of undergraduate students identified as ‘at risk’. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 20. Plymouth, UK. https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi20.605

- Martela, F., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). The benefits of benevolence: Basic psychological needs, beneficence, and the enhancement of well‐being. Journal of Personality, 84(6), 750–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12215

- Motta, S. C., & Bennett, A. (2018). Pedagogies of care, care-full epistemological practice and ‘other’ caring subjectivities in enabling education. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(5), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1465911

- Murphy, J., & Holste, L. (2016). Explaining the effects of communities of pastoral care for students. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(5), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.993460

- Mutch, C., & Tatebe, J. (2017). From collusion to collective compassion: Putting heart back into the neoliberal university. Pastoral Care in Education, 35(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2017.1363814

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Measures Package, 61. APA Psyc tests. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?

- Rossi, G., Lenzi, M., Sharkey, J. D., Vieno, A., & Santinello, M. (2016). Factors associated with civic engagement in adolescence: The effects of neighbourhood, school, family and peer contexts. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(8), 1040–1058. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21826

- Salmivalli, C. (2014). Participant roles in bullying: How can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Theory Into Practice, 53(4), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947222

- Scriver, S., Walsh Olesen, A., & Clifford, E. (2021). Partnering for success: A students’ union-academic collaborative approach to supplemental instruction. Irish Educational Studies, 40(4), 669–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1899020

- Seary, K., & Willans, J. (2020). Pastoral care and the caring teacher–value adding to enabling education. Student Success, 11(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v11i1.1456

- Silke, C., Boylan, C., Brady, B., & Dolan, P. (2019a). Empathy, Social Values and Civic Behaviour among Early Adolescents in Ireland: Composite Report. UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre. https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/handle/10379/14989

- Silke, C., Brady, B., Boylan, C., & Dolan, P. (2018). Factors influencing the development of empathy and pro-social behaviour among adolescents: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 94, 421–436. November 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.027

- Silke, C., Brady, B., Dolan, P., & Boylan, C. (2020). Social values and civic behaviour among youth in Ireland: The influence of social contexts. Irish Journal of Sociology, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/0791603519863295

- Stufflebeam, D. L., & Coryn, C. L. (2014). Evaluation theory, models, and applications (Vol. 50). John Wiley & Sons.

- Suárez-Orozco, C., Hernández, M. G., & Casanova, S. (2015). “It’s sort of my calling”: The civic engagement and social responsibility of Latino immigrant-origin young adults. Research in Human Development, 12(1–2), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2015.1010350

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, S. M. (2012). Who are the millennials? Empirical evidence for generational differences in work values, attitudes and personality. In E. Ng, S. Lyons, & L. Schweitzer (Eds.), Managing the New Workforce: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation (pp.152–180). Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Yorke, M. (2016). The development and initial use of a survey of student ‘belongingness’, engagement and self-confidence in UK higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.990415

- Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2010). Beyond hard outcomes: ‘Soft’ outcomes and engagement as student success. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(6), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.522084