ABSTRACT

Friendship is of paramount importance to children’s holistic well-being and development. Friendship often runs smoothly, but when it runs into difficulties this can be unsettling and time consuming, particularly after the lunchtime break. This article makes an original contribution by placing the lunchtime period under scrutiny and specifically the role of lunchtime welfare supervisors in supporting children’s friendships. I adopt a case study approach, of year two provision (six- and seven-year-olds), involving five lunch time welfare supervisors and a Headteacher. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, field notes and visual images. Findings provide new insights into specific strategies in the ‘Friendship Toolkit’ employed by Lunchtime Welfare Supervisors [LWS] to support children’s friendships, including calming down techniques, the use of a ‘put it right area’, playground leaders and post lunchtime briefing meetings. By way of conclusion, I argue that while lunchtime welfare supervisors have been somewhat overlooked in the literature, their role is significant for promoting and developing opportunities for ‘children’s friendship agency’ and, when required, bespoke friendship support. LWS are therefore pivotal to children’s holistic well-being, learning and development and how children experience school life. Consequently, the role of the LWS in supporting children’s friendships has implications for practice through the application of the ‘friendship toolkit’ of strategies and providing opportunities for ‘children’s friendship agency’.

Introduction

Childhood play is an important ingredient for holistic child development, learning and well-being (Barros et al., Citation2009; Clarke, Citation2018) and therefore, opportunities to playFootnote1 are vital for friendships to flourish. Research into time spent on the playground demonstrates the physical, psychological and social benefits of this experience (Ramstetter et al., Citation2010). Playground play provides opportunities to learn and practise interpersonal skills such as co-operation, conflict resolution and problem solving (Ginsburg, Citation2007). Acar et al. (Citation2017) also note that children interact more with their peers during child directed free play or outdoor time. Friendship is important to children and what goes on in the playground sets the tone and mood for the rest of the day (Clarke, Citation2018).

Despite this, free play within the classroom starts to be restricted when children embark on the first year of compulsory schooling in England (year one, aged 5 and 6 years) when a more formal approach reduces opportunities for play and therefore friendship (Broadhead, Citation2009). By the time children reach year two (aged six and seven years), there is often little or no play-based provision left within the classroom. The only opportunities for child-initiated free play are during playtimes and lunchtime, and therefore playground interactions are significant for the formation and maintenance of children’s friendships. Consequently, the management of this time is crucial for how children experience friendships and raises important questions: for instance, should children be permitted to manage and negotiate their friendship experiences independently or be guided through adult intervention?

Traditional discourses position childhood as a time for children to be instructed on how to behave (James & Prout, Citation2014). Over the last thirty or more years these traditional discourses have been challenged (United Nations, Citation1989), shifting from a deficit view that children should be ‘seen and not heard’ to one where children are seen as ‘socially active participants’ who are competent and capable (Lancaster, Citation2010, p. 85). Dahlberg et al., Citation2006, p. 49) state that children should be permitted to have agency to create ‘knowledge, culture and their own identity’. Katsiada et al. (Citation2018, p. 937) define agency as ‘children’s capacity to make autonomous decisions and choices in all matters affecting them’. Importantly, more recently, this interest into children’s agency has been extended to cover the building and maintenance of children’s friendships (Alvarez-Miranda, Citation2019; Corsaro, Citation2015).

While children may be considered agentic when managing their friendships, children cannot be left totally unsupervised. This is because, despite the benefits of friendship, there can also be negative aspects and instances where children would like support. Playtime is often cited as, ‘the main source of conflict and difficulties’ at school (Arthur, Citation2004, p. 6). Consequently, some schools have tried to reduce the length of playtimes to lessen conflict and the time spent trying to resolve issues. However, this may be counterproductive as children need these opportunities to negotiate friendships as part of healthy development (Corsaro, Citation2015). In addition, occasionally children may welcome an attentive adult to scaffold, support and facilitate their friendship experiences (Katsiada et al., Citation2018). Hedges and Cooper (Citation2017, p. 401) echo this idea stating, ’ … some children may need explicit advice and help with friendship knowledge and strategies’. Likewise, Varghese (Citation2019, p. 47) observes ‘Some children may not be sure how to nurture these skills’ and that good modelling … and plenty of opportunities and space to practise” are needed. Furthermore, children may also need support to manage the more negative experiences that can emerge from social interaction (Parry, Citation2015). As the above discussion has shown, the lunchtime period and the role of LWS are crucial when it comes to friendships, yet this time can raise challenges for children in building and maintaining their friendships.

The LWS are staff members who are employed for about an hour each day to supervise children during the lunch period so teachers can take a break. Historically, the role of lunchtime staff has been overlooked. This notion is reflected in the low pay, status and conditions of lunchtime staff (Sharp, Citation1994). Generally, LWS tend to be non-qualified and work on a part-time basis. Yet, in the last couple of decades the value and importance of the lunchtime experience for children has come to the fore. For instance, it has been noted that returning to the classroom after a negative, unresolved experience can impact on learning and well-being (Carter, Citation2021; Carter & Nutbrown, Citation2016). Therefore, it is important that we understand more about what the role of LWS entails. Whilst the importance of children’s friendships is becoming well established in the literature (Daniels et al., Citation2010; Hedges & Cooper, Citation2017; Peters, Citation2010; Brogaard-Clausen and Robson, Citation2019), to my knowledge there has been no research in relation to LWS since the 1990s and no studies focusing specifically on the role of the LWS in relation to children’s friendships. This article therefore poses the question: How does the lunchtime welfare supervisor support children’s friendships?

This article is organised as follows. First, I explore what previous research has revealed about the importance of young children’s friendships, including the current knowledge on access to play and friendship. I then address the role of the LWS and highlight a gap in the literature in relation to this role and children’s friendships. This is followed by an outline of the case study methodology and methods. The findings reveal strategies used by LWS that support children to be independent or provide bespoke support for friendship. Finally, the paper suggests new implications for practice around the role of the LWS in supporting children’s friendships.

Literature review

The importance of friendship

A central concern of this study is children’s friendships. Friendships are usually defined as being mutual (Rubin et al., Citation2006). There is usually a mutual preference for interaction which includes sharing emotions and reciprocity during play (Engdahl, Citation2012). Leading on from this, friendship can provide several positive affordances to children. For example, Dunn and Cutting (Citation1999) note how children who could understand the emotions and intentions of others were more likely be able make and keep friendships of quality. The presence of friendships, according to Coelho et al. (Citation2017, p. 813) ‘increased the ability to regulate interactions and emotions, fostering the skills to better understand social relations’. This suggests friendships can increase social skills and social competency. In turn this can have a positive influence on children’s well-being and build a sense of belonging and community (Rogoff, Citation2003). Research has also indicated the benefits friendship can have upon learning and development including a more positive attitude to school life and improved attainment (Ladd, Citation1990). Friendship can also be a protective factor against loneliness and rejection. However, a lack of friends can lead to negative outcomes. For instance, Parker and Seal (Citation1996) noted that social rejection at the preschool phase was a predictor of externalizing problems during adolescence such as delinquency, aggression and attention difficulties. Overtime this can also lead to internalizing issues such as low self-esteem, anxiety and loneliness.

Access to friendship: agency or support for friendship?

Access to play is required for the development and maintenance of friendships. Group formation, including inclusion and exclusion of children, is a problematic issue during pre-school and into the primary age phase (Corsaro, Citation2015). Within children’s peer culture, children develop strategies for including or excluding peers (Oh & Lee, Citation2019). Groups exclude children as they feel threatened by newcomers who may spoil established play. Children have to learn strategies that will allow them to enter play situations in a non-threatening and unobtrusive manner (Corsaro, Citation2003).

Therefore, we should not intervene and force children’s friendships, as by doing so we are asking children to internalise adult skills and knowledge (Corsaro, Citation2003). Corsaro proposes that within childhood there is a distinct culture, and entry strategies are part of this culture. In the same vein, adult intervention in children’s play also carries ethical implications. Carter and Nutbrown (Citation2016) pose a ‘pedagogy of friendship’ framework where adults value and respect children’s friendships, continually develop their knowledge of peer culture (routines and practices) and provide time and space for children to have agency. Likewise, Brogaard-Clausen and Robson (Citation2019) claim that children have a right to privacy in their personal relationships and there are times when adults should step back and allow children to exercise agency. Therefore, children need opportunities for agency and independence to manage their play and friendships. Alvarez-Miranda (Citation2019) agrees with this notion, stating that children should be able to choose their friends and not have friendships forced upon them. This perspective proposes that children be provided with opportunities to exercise ‘personal autonomy and negotiating social order’ (Markström & Halldén, Citation2009, pp. 112–113).

This is not to say that we should leave children completely to their own devices, but rather to tune into children and recognise when they may need additional support (Hedges & Cooper, Citation2017; Varghese, Citation2019; Parry (Citation2015). Some children recognise the limits of their own agency and want adults to intervene and help them, including support to enter play, protect them from physical aggression and resolve disputes over toys. Children recognise adults’ power to ‘enforce ways of behaving within their peer group’ (Katsiada et al., Citation2018, p. 945). Other studies have also recognised the contribution adults can provide to help children access play and sensitively facilitate friendships (Carter, Citation2021; Einarsdottir, Citation2014; Peters, Citation2010).

In light of these findings, some schools have looked at strategies to encourage inclusion on the playground so that more children can benefit from the affordances of play and friendship without using direct adult intervention such as use of the playground ‘buddy bench’ (Clarke, Citation2018, p. 9). Children were asked to sit on the buddy bench if they had no-one to play with and then an adult or another child would support them to find someone. What appeared to be key here was the way that the adult(s) introduced the ‘buddy bench’ to the children. The purpose of the bench was for ‘children who do not know who to play with’ rather than for someone who has no-one to play with. This approach shifted from the perception of a lonely and rejected child to a buddy ‘worthy of being seen and included’ (Clarke, Citation2018, p. 18). Similarly, it is important for there to be a collective responsibility for friendship rather than the burden of a lack of friends or the pressure of making and keeping friends lying solely with individual children themselves. The dilemma for all adults supporting children’s friendships is therefore when to promote agency, when to provide adult support and how to do this (Brogaard-Clausen & Robson, Citation2019). This study is therefore relevant and timely in relation to the role of the LWS and supporting children’s friendships.

The role of the lunchtime welfare supervisors in supporting friendships

As early as the late 1980s the Elton, Citation1989) noted the importance of lunchtime particularly on children’s behaviour. LWS were introduced during the 1980s when teachers’ industrial action saw an end to teachers covering the lunchtime period. There was recognition that taking a break over the lunchtime period could be beneficial for teacher well-being and performance (Sharp, Citation1994). Sharp’s research in the 1990s on training schemes for lunchtime supervisors brought to light some common concerns in schools. Concerns centred upon a lack of status being apportioned to the role. This included poor communication, not being permitted to use staff toilets or the staff room, authority being undermined and concerns about how to manage sick or injured children. Sharp (Citation1994, p. 122) stressed that, ‘Too often they have no voice in school matters. The combination of no communication system and lack of status can bring about a devaluing cycle which leads to supervisors not even bothering to mention their suggestions’. Many schools started to address the lack of respect for LWS and explore ways to raise the profile of this role (Fell, Citation1994). Strategies included sending letters home to introduce the lunchtime staff, inviting LWS to school events and socials, thanking LWS for their contribution to school and LWS training. However, since Fell’s study, to my knowledge there has been no further research on LWS, and nothing particularly in relation to friendship. The present study seeks to begin to address this gap.

Methodology

The data for the current study is drawn from a larger study which investigated supporting children’s friendships in year two (six- and seven-year-olds) with teachers, teaching assistants, children and parents. It was a single case study. Yin (Citation2018, p. 15) defines a case study as ‘an empirical method that investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the “case”) in depth and within its real-world context’. This is relevant to this study which researches the phenomenon of children’s friendships in one specific school. The setting was an infant and pre-school providing education for children aged 3+ to 7+ in the north of England. The pre-school has 26 places and the school has grown to a three form entry (90 children per year group). That is nine classes in total. It is situated within an affluent community with 30% BME. The number of pupils in receipt of pupil premium funding is below the national average at 2 to 3%. Similarly, numbers for SEND are only 10%, although numbers of children with complex needs is high as parents often choose the school based on reputation.

The data were collected in a natural setting with a focus on relationships and processes. This was important for capturing ‘the complexity and subtlety of real-life situations’ (Denscombe, Citation2010, p. 55). The small-scale nature of this research allowed me to delve more deeply into children’s friendships. The intention of this study was not to generalise but to see what could be learnt from a particular context (Yin, Citation2018). The boundary of this case study is the school community and the timeframe, the summer term.

Interviews are a key source of case study evidence. They help to unpack the ‘how and why’ of key events and ‘resemble guided conversations’ which helps to get to in-depth perspectives (Yin, Citation2018, p. 118). This paper focuses specifically on five semi-structured interviews that were conducted with lunchtime welfare supervisors and a head teacher. In addition to this I sat in on two post lunchtime meetings that the LWS had for 10 mins at the end of each lunchtime. Field notes and reflective comments were also kept using a research journal after the interviews and attending the post lunchtime meetings. Finally, some photographs were taken of resources and images in the environment that were made reference to by the participants during the interviews. The LWS were all female staff. A couple were employed as teaching assistants in school and worked as LWS. Some were full time and others worked only two or three lunchtimes. Greater detail on the LWS is not provided as their anonymity would be comprised, especially within their own school context. This study was approved by the University’s Ethics Review Board, including written informed consent and the use of pseudonyms have been used to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

Framework for analysis

The interviews were analysed specifically using reflexive thematic analysis (TA; Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Braun and Clarke describe ‘reflexive’ TA as an active, creative and subjective approach where the subjective researcher is unapologetically viewed as a resource and part of the meaning making process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The first phase of the analysis included intensive reading and re-reading to become fully immersed and familiar with the data. The second stage involved coding or labelling of the dataset with specific features relating to the main research question. I then proceeded to the third phase in which initial themes were generated. This involved bringing the data together under broader ‘patterns of meaning’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The third stage also involved revisiting the themes to review and define. Once the final themes were named these were written up, weaving in ‘the analytic narrative’ from the data, and contextualising in relation to the literature (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 93).

Findings

The LWS and friendship strategies

The aim of this study was to examine the role of the LWS in supporting children’s friendships. The main findings indicate that the LWS were utilising strategies suggested by the whole school to predominately encourage children to be independent in their friendships or to provide more direct adult support when required. Therefore, I present the key findings under two theme headings 1) Friendship Independence, and 2) Bespoke Friendship Support. To contextualise, the school had identified friendship at lunchtimes as a priority area and noted that most children were outside for an hour at lunchtime. Therefore, this was recognised as a fundamental part of the day in relation to friendship experience.

Theme 1 – LWS strategies for promoting friendship independence

During the interviews, the LWS spoke of the strategies used by the school and adopted by themselves to support children’s friendship independence. Part of their role was to apply these strategies in the playground. The LWS spoke of three strategies, including calming down techniques, the ‘put it right area’ (Cotton, Citation2017) and playground leaders.

Strategy 1 – calming down techniques

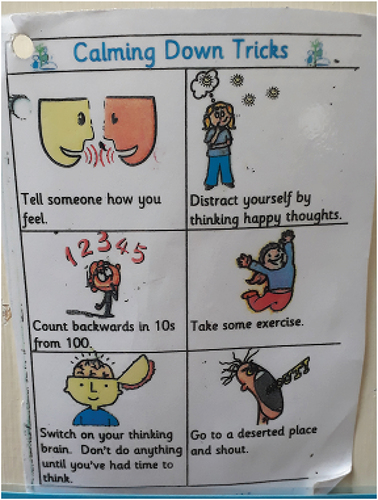

The first strategy was calming down techniques, which the LWS encouraged children to practise. Each LWS had a keychain with examples they could refer to on the playground (see – calming down tricks). This was used when children had an argument and needed to calm down before negotiating a resolution. LWS 5 provided the following explanation:

If a child has felt particularly upset about a situation before they talk about it, we might get them to do things like breathing technique, or there’s fist flowers or counting to calm themselves before they go and speak to the other person about what’s happened.

Image 1. Calming down tricks (see appendix 1).

Children at six and seven years can find it very hard to manage their feelings when issues occur in play, playtime can be ‘the main source of conflict and difficulties’ (Arthur, Citation2004, p. 6). Consequently, some schools have tried to reduce the length of playtimes to lessen conflict and the time taken to resolve issues. However, if we deny children opportunities to feel these emotions and support their management this could also affect children’s well-being and their friendships. In this school, children were encouraged to feel these emotions and then were provided with strategies to manage these feelings and self-regulate (see e.g. Eisenberg et al., Citation2010; Robson, Citation2016)

Strategy 2: put it right area and the use of shared language

The next strategy was the ‘put it right’ area (Cotton, Citation2017). This was a physical space in the corner of the playground where children could go to sort out a friendship issue. The aim was to provide children with a physical space to try and resolve issues. Depending on the child or nature of the argument, they were encouraged to either resolve this independently or with adult facilitation. This strategy advocated children having independence in their friendship negotiations. LWS 2 and 3 outline the use and purpose of this area.

Then as well as in the classroom they have a put it right area, so if two are arguing, you can say, ‘Go and sit there and put it right.’ Then we have these things where we say try this and try that and then I’ll come back and check.

If there are any issues in the playground we try and get children to talk to each other about the situation … We let them try and figure as much as they can out.

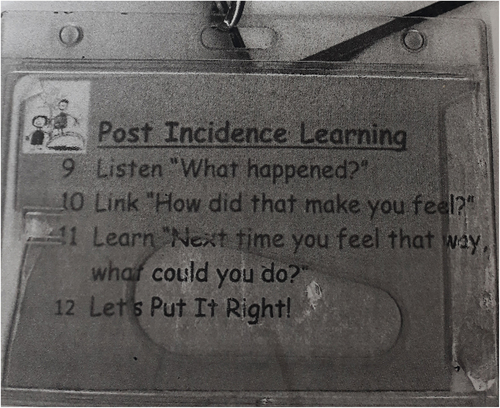

Alongside each ‘put it right’ area language prompts were shared to support children, known as post incidence learning steps (Cotton, Citation2017; see - shared language). The LWS encouraged children to use these visual prompts.

Image 2. Shared language (see appendix 2).

Children were not able to do this straight away in the reception class (4- and 5-year-olds) but were taught and scaffolded until they felt they could manage it themselves. LW5 discussed here how she supports this process.

So we’d say listen, what happened, and then the next step links to that, how did that make you feel? The next step would be learn, so next time you feel that way, what would you do? The final step is let’s put it right. I think it’s a really positive programme and it’s something that all the children know about and are aware of. So if something has happened, that’s a positive solution for them, but it’s also a positive for staff, because we can say to them, let’s go through the steps, and they know that’s how we solve any conflict.

This technique resounds with Markström and Halldén (Citation2009, pp. 112–113) who advocate for children’s agency and autonomy to address issues of social order, relinquishing some power to the children. They argue for children to be provided with opportunities for ‘personal autonomy and negotiating social order’. However, the challenges in practice appeared to be when children were reluctant to enter into this process. Some children perceived that by entering into this process they would be in trouble and/or it could lead to unwanted adult intervention. For others, it was simply that they were not ready and in the right frame of mind to talk through their emotions. LWS 5 and 4 emphasise the need for children to be provided with adequate time and how many children may find it difficult to tackle issues in this way. It needs both parties to willingly engage.

I suppose the challenges are if a child is particularly angry or upset, they may not feel that they’re at a point where they can go through that programme, so I suppose it’s then thinking of other ways that we can help them.

I guess challenges would be if it’s a dispute and the other child doesn’t want to engage. They’re not ready to sort it out sometimes.

The LWS also commented on the fact that sometimes this area was not utilised. This could suggest that startegies need revisiting with children to identify potential issues. This would require time for listening to children to evaluate the efficacy of the strategy.

Strategy 3 – Playground Leaders

Finally, the last strategy in the toolkit for promoting friendship independence was the playground leaders. These were year two children (6- and 7-year-olds). Their role was to be ambassadors in the playground, helping to sort out friendship disputes or play with children who were without a friend.

Here the children were encouraged to be independent, and this gave these children opportunities to lead and be role models for younger children. Here LWS 4 discussed the playground leaders’ role.

They do have the bench, so if they go and sit on the bench if they want a friend so if you haven’t got anyone to play with you can sit on the buddy bench and hopefully someone will come and play, or the welfare supervisors will come and find someone.

Image 3. Playground leader hats, the buddy bench and the role of playground frieNds (see appendix 3).

The playground leader’s strategy encouraged children to be inclusive and utilise the strategies they had been taught for independence since starting school. This demonstrates the inclusive ethos of the school, and the influence teachers can have on developing an inclusive culture (Clarke Citation2018). However, more recently there is recognition of the practical challenges as Alvarez-Miranda (Citation2019) rightly point out, we cannot force friendships upon children.

Another challenge appeared to be in the attrition rate of the playground leaders. LWS 2 suggested here that for some children the role could affect children’s own friendships as they were not able to play with their own friends.

Some children volunteer and then after the third week they give up.The school had addressed this by asking children to carry out this role on certain days to reduce the risks to their own friendships.

LWS suggested another issue, noting, that the buddy bench was often underutilised.

I do think the buddy bench thing, I do think we should maybe push that a little bit more. I never really refer to that ever and, to be honest, I don’t see children using it … Let’s take children to the buddy bench, and it would encourage other children to then see that they’re on their own. If they’re walking around holding a welfare supervisor’s hand, other children, it’s not obvious to them. If a child went to the buddy bench, even with a welfare supervisor’s support, other children could see that and maybe we could encourage them to come over.

This chimes with Clarke (Citation2018, p. 9) who suggested a shift in the way that the ‘buddy bench’ was introduced. The purpose of the bench was for ‘children who do not know who to play with’ rather than for someone who has no-one to play with. The challenges of implementation, of this final strategy, into practice may suggest again the need to regularly revisit strategies and evaluate their efficacy. However, in reality, this can be difficult to achieve with the academic pressure and time constraints within the current educational system.

Theme 2: bespoke friendship support

Despite the school promoting and encouraging autonomy and independence in their friendships there was also acknowledgement that at times children would need adult support The following headteacher comment contextualises this.

Eventually they might have to use their adults, but actually if they can resolve that themselves, all the better.

Likewise, the literature in the field has reported occasions when some children require adult support and intervention in their friendship negotiations (Carter, Citation2021; Carter & Nutbrown, Citation2016). Other research also highlights the importance of adult facilitation and support for children’s friendships (Alvarez-Miranda, Citation2019; Coelho et al., Citation2017; Katsiada et al., Citation2018; Varghese, Citation2019). For some children, more adult intervention was required and even those who were mostly independent still required some assistance with friendship encounters.

The headteacher notes the adult role in recognising the instances where bespoke support is called upon to intervene and support children.

It is very much the teacher’s role … When you pick up either some incident has happened, or from conversations with welfare supervisors, or so generally that they need more support on that, then we do plan in interventions for them and specifically target them.

Post playground briefing meetings: a strategy for bespoke friendship support

The post playground briefing meetings were different to the other strategies because they went beyond the strategies used to promote friendship independence. The aim of these meetings was to review how the lunchtime had gone and discuss any issues or particular children who may need additional support. LWS attended a post playground briefing meeting at 1pm. All the LWS were paid an additional ten minutes to attend and feed into this meeting. This was led by the lead LWS in the staffroom. This gave a support network for the LWS and a sense of shared responsibility where certain classes or children were not the responsibility of just one LWS. In addition, relevant information could be fed back and shared with teachers face to face or via a written online record. As part of this meeting a folder with passport sized photographs of all the children was used to discuss children who may need additional support. The reason for this folder was so that all staff knew who the children were that required additional support. The following head teacher comment provides context on the school ethos and rationale for these meetings.

I’ve not seen it in others [schools], but for us it’s given a high priority. That was partly because I see that as joining the dots. It means you are valuing the lunchtimes, they’re not just somebody who’s looking after them, actually you’re wanting high quality interaction, but you’re also allowing them to debrief. A number of them are teaching assistants as well and they’re better placed, they’ve got a bit more of a view of certain children, the more vulnerable ones. But if you’re only coming in two lunchtimes a week or something, it’s really hard to be part of that. So this, we’ve found, and feedback from the staff, even if they’re only working a couple of days a week for an hour and a half, it enables them to feel part of that overall ethos and values … some of them are not substantive staff in other times and actually some of the children we’ve got are quite complex and it’s knowing each child is different and it’s knowing that actually for that child we do that....

At one of the meetings, I attended the staff talked about Mable who seemed to be walking around alone with her toy all lunchtime. A note was made of this, information was to be shared with the teacher and the LWS were collectively thinking of ways they might support Mable to play when she was ready to do so.

Getting to know the children and spending time observing them and tuning into children was important. Some of these children appeared to be excluded from play and therefore friendship. This resonates with the work of Alvarez-Miranda (Citation2019) concerned with ways of reducing social exclusion and exploring ways to include all children.

LWS 4 & 1 discussed being paid for the post lunchtime briefing meeting and how that assists them in supporting children’s friendships.

We are paid for ten minutes. Not a lot of money but it’s significant so I think the purpose of those meetings is just like an indication of sometimes very practical things, like we need some help on the buddy bench, just piecing together friendship issues. Or if we are concerned about somebody, like the little girl who was mentioned who’s just a bit sad at the moment – if lots of individuals notice that, it’s nice just to get together and then we can report back to the teacher and say we’ve noticed that so-and-so has been a bit sad these past few lunchtimes. I’m getting to know most of their faces now.

But there are people here who do only work at lunchtime, but because of our system that we have where we go through our debrief, we can then tell them and then they all know, so everybody is all kept in the loop.

In this school there was support for LWS through sharing the strategies used in the school to support friendship. I also asked the LWS despite this did they feel equipped to support children’s friendships or did they feel they needed further support. Most staff were using their own experiences and interpersonal skills to manage friendship encounters. LWS 5 explained how she was drawing upon her own experience of being a parent and asking other LWS or teachers for advice when needed.

Nine times out of ten I think they are things that we can generally deal with. I’ve got two children, so probably my opinion would be different to somebody who has different family circumstances. Generally, I’ll feel quite comfortable with it. If it’s a situation where I’m not quite sure, I would usually go to the teacher and flag to the teacher that something has happened and let her know, or him know, what we’d done to sort it out, or if I’m unsure I’ll ask one of the other welfare supervisors, just to reassure yourself that you’ve dealt with it in the right way really.

LWS 4 also discussed using her own experience as well as the strategies and resources provided by the school as she had not received official training.

I’m quite new to this job still, so I could probably do with something. I’ve never had any official training. I just use my own experience really. We have got these little cards about golden rules, about making good choices and things, calming down tricks and problem-solving to do with having problems with friends.

Discussion

The main contribution of the study is to shed light on the lunchtime period and the role of the LWS, what is going on and what challenges remain. The results of my study provide original insights for practice in relation to a ‘friendship toolkit’ of strategies used by LWS and suggest opportunities for ‘children’s friendship agency’. My study, addressed the following research question: How does the lunchtime welfare supervisor support children’s friendships? Three main insights were highlighted. First, LWS are utilising a ‘friendship toolkit’ (a term I am suggesting) of strategies that intend to promote children’s independence and autonomy. Second, they are also providing opportunities for bespoke friendship support for those encounters or extended periods that may require additional adult support. Third, the study uncovered some of the challenges of enacting this approach to achieve positive outcomes for children’s friendships.

The ‘Friendship Toolkit’

It was evident that the LWS wanted to support children’s friendships through the application of what I call a ‘Friendship Toolkit’ of strategies. Respect and value of children’s friendships was apparent in the time devoted to this (Carter & Nutbrown, Citation2016). This is also evident in the context provided by the Headteacher. … we make a priority of developing friendships … The intention of the LWS was to enable children to be independent in their friendships. This was being achieved through providing physical and emotional space, through strategies such as, the ‘put it right area’. This strategy provided a physical space to retreat to and also emotional space for talk and negotiation to resolve friendship issues. Shared language was also encouraged to scaffold this process if required. Similarly, the playground leaders appeared to be a way of developing collective responsibility for inclusion and friendship. Rather than the responsibility of friendship falling onto individual children (Brogaard-Clausen & Robson, Citation2019).

Bespoke friendship support

It was acknowledged that certain encounters or children would require further adult support. For some children this was occasionally and for others over more extended periods. The post playground meetings were a strategy to help provide this bespoke friendship support. This was a collaborative LWS team approach to support individual children and the LWS themselves. The LWS illustrated that they drew upon their own experience and interpersonal skills to manage some friendship encounters. This suggested the subjective nature and complexity of supporting children’s friendships and indicates some LWS may appreciate further training. Information was shared with teachers and the support of teachers was also drawn upon when needed. This also showed an intention to develop LWS knowledge of children’s friendships and share good practice (Carter & Nutbrown, Citation2016, Carter Citation2021).

The challenges of enacting this approach and implications for practice: ‘Children’s friendship agency’

Recent research suggests that children should be provided with agency in relation to their friendships (Carter, Citation2021; Markström & Halldén, Citation2009). Carter and Nutbrown (Citation2016) note the importance of the adult role through the ‘Pedagogy of Friendship’ framework. Pivotal to the adult role is the need to value friendships, develop practitioner knowledge of friendships and ultimately provide opportunities for children to have agency within their friendship encounters. In this study there is evidence that the school had agentic intentions for the children. This was demonstrated through the sharing of whole school strategies and resources to support friendship independence (‘independence’ term used by the school), for example, calming down techniques, the put it right area, the use of shared language prompts. This case study shows that this school had made steps to transfer some control and autonomy to children through the application of the LWS ‘friendship toolkit’ with the main intention of enabling children to become independent when managing their friendships.

However, the findings also suggest the complex nature of children’s peer cultures. Brogaard-Clausen and Robson (Citation2019) demonstrated that the approach was not as simple as applying strategies and having awareness of when to step back and when to intervene and support friendships, but also how to do this effectively. The application of the ‘friendship toolkit’, was not always straightforward. For example, despite adults wishing to resolve friendship issues swiftly children may not be emotionally ready to enter into resolution dialogue. LWS 4 noted the challenge of both parties not always being ready to engage in the resolution process after a fall out. Likewise, there was a suggestion that both the ‘put it right area’ and the ‘buddy bench’ were often underutilised. LWS 5 stated that she did not see children using the buddy bench. This may indicate that there is a stigma involved in using these strategies. Children going into the ‘put it right’ area may perceive that this would draw unwanted adult attention or intervention. The playground buddy bench might advertise those who have no-one to play with. This warrants further research involving children into why these strategies might be underutilised during the lunchtime period.

Finally, this study highlights the importance of recognising that adults and children have different priorities (Brogaard-Clausen & Robson, Citation2019). This leaves space for adults to learn from the children and we need to spend time listening and talking to children, allowing children to suggest some child led strategies for managing friendship. Practitioners/Teachers face ever increasing demands on their time (Hedges & Cooper, Citation2017); however, there needs to be permission for schools to give time to this, prioritising on a school development plan. Time to develop value and respect for friendships, increase knowledge of all staff, including the LWS and align more with the priorities of children. This would provide genuine opportunities for ‘children’s friendship agency’ (a term I am suggesting). This would provide not only time and space for children but time to listen to children, make sure ‘friendship toolkit’ strategies were effective and allow children to make authentic ‘autonomous decisions and choices’ (Katsiada et al., Citation2018, p. 937).

Conclusion

In this article, I have scrutinised the lunchtime period and the role of the LWS. The research highlights important insights into the strategies used by LWS (‘Friendship Toolkit’ of strategies) to promote ‘children’s friendship agency’ and provide bespoke friendship support that may chime with other schools. I have also pointed out the complexities and issues with these strategies, including issues around ‘children’s friendship agency’. There is nonetheless still much critical research to be carried out in relation to how the role of the LWS can be developed to further support children’s friendships, particularly in relation to the efficacy and development of strategies in the ‘friendship toolkit’ and the concept of ‘children’s friendship agency’. Therefore, this article provides opportunities for dialogue and reflection on how to support children’s friendships during this lunchtime period and offers practical implications for school practice through the ‘friendship toolkit’ of strategies. In addition, it would be beneficial to creatively engage with children to understand the efficacy of these strategies from their perspective: I found some strategies were being used less frequently and some children were reluctant to use them. Children would be able to provide further insight into strategies they find useful. There also needs to be opportunities for developing the concept of ‘children’s friendship agency’ so that children are provided with more frequent and genuine opportunities ‘to make autonomous decisions and choices’ within their friendships (Katsiada et al., Citation2018, p. 937). The impact of the global pandemic on children socially and emotionally adds to a sense of urgency and suggests a timely focus for further practitioner attention upon the role of all adults including LWS and how children can be involved in the creation of an approach that provides greater agency and efficacy for children’s friendships.

Appendix_1___2_Calming_Down_Tricks.docx

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Cathy Burnett and Dr Lisa McGrath who kindly acted as reviewers for this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Notes

1. The choice of the term ‘lunchtime welfare supervisor’ has been used throughout this paper to refer to staff that work with children in school during the lunchtime break. From this point in the article lunchtime welfare supervisors will be referred to in the abbreviated form of LWS.

References

- Acar, I. H., Hong, S.-Y., & Wu, C. (2017). Examining the role of teacher presence and scaffolding in preschoolers’ peer interactions. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(6), 866–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1380884

- Alvarez-Miranda, M. J. (2019). Developing positive social interactions among children in a danish preschool. In F. Armstrong & D. Tsokova (Eds.), Action Research for Inclusive Education (pp. 57–66). Routledge.

- Arthur, L. (2004). Looking out for each other: Children helping left‐out children. Support for Learning, 19(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0268-2141.2004.00311.x

- Barros, R. M., Silver, E. J., & Stein, R. E. K. (2009). School recess and group classroom behavior. Pediatrics, 123(2), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2825

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Broadhead, P. (2009). Conflict resolution and children’s behaviour: Observing and understanding social and cooperative play in early years educational settings. Early Years, 29(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140902864446

- Brogaard-Clausen, S., & Robson, S. (2019). Friendships for wellbeing?: Parents’ and practitioners’ positioning of young children’s friendships in the evaluation of wellbeing factors. International Journal of Early Years Education, 27(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2019.1629881

- Carter, C. (2021). Navigating young children’s friendship selection: Implications for practice. International Journal of Early Years Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1892600

- Carter, C., & Nutbrown, C. (2016). A pedagogy of friendship: Young children’s friendships and how schools can support them. International Journal of Early Years Education, 24(4), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2016.118981

- Clarke, K. M. (2018). Benching playground loneliness: Exploring the meanings of the playground buddy bench: Exploring the meanings of the playground buddy bench. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 11(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2018143930

- Coelho, L., Torres, N., Fernandes, C., & Santos, A. J. (2017). Quality of play, social acceptance and reciprocal friendship in preschool children. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(6), 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1380879

- Corsaro, W. A. (2003). We’re friends, right? : inside kids’ culture. Washington, District of Columbia: Joseph Henry Press.

- Corsaro, W. (2015). The Sociology of childhood (4th ed.). Pine Forge.

- Cotton, D. (2017). How to teach behaviour and how not to. Positive Behaviour Strategies Limited.

- Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., & Pence, A. (2006). Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Languages of evaluation (2nd ed.). Falmer Press.

- Daniels, T., Quigley, D., Menard, L., & Spence, L. (2010). My best friend always did and still does betray me constantly: Examining relational and physical victimization within a dyadic friendship context. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509357531

- Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide : for small-scale social research projects (4th ed.). London: Open University Press.

- Dunn, J., & Cutting, A. L. (1999). Understanding others, and individual differences in friendship interactions in young children. Social Development, 8(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00091

- Einarsdottir, J. (2014). Children’s perspectives on the role of preschool teachers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 22(5), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2014.969087

- Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., & Eggum, N. D. (2010). Self-regulation and school readiness. Early Education and Development, 21(5), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.497451

- Elton, R. (1989). Discipline in schools : Report of the Committee of Inquiry. HMSO.

- Engdahl, I. (2012). Doing friendship during the second year of life in a swedish preschool. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.650013

- Fell, G. (1994). ‘You’re only a dinner lady!’. In Blatchford and Sharp (1994) breaktime and the school: Understanding and changing playground behaviour (pp. 134–145).Routledge.

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697

- Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2017). Collaborative meaning-making using video footage: Teachers and researchers analyse children’s working theories about friendship. European Early Childhood Educational Research Journal, 25(3), 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2016.1252153

- James, A., & Prout, A. (2014). Constructing and reconstructing childhood (3rd ed.). Falmer.

- Katsiada, E., Roufidou, I., Wainwright, J., & Angeli, V. (2018). Young children’s agency: Exploring children’s interactions with practitioners and ancillary staff members in Greek early childhood education and care settings. Early Child Development, 188(7), 937–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1446429

- Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61(4), 1081–1100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02843.x

- Lancaster, P. Y. (2010). Listening to young children: Enabling children to be seen and heard. In G. Pugh & B. Duffy (Eds.), Contemporary issues in early childhood education (pp. 79–94). Sage.

- Markström, A., & Halldén, G. (2009). Children’s strategies for agency in preschool. Children and Society, 23(2), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00161.x

- Oh, J., & Lee, K. (2019). Who is a friend? Voices of young immigrant children. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(5), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1651967

- Parker, J. G., & Seal, J. (1996). Forming, losing, renewing, and replacing Friendships: Applying temporal parameters to the assessment of children’s friendship experiences. Child Development, 67(5), 2248–2268. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131621

- Parry, J. (2015). Exploring the social connections in preschool settings between children labelled with special educational needs and their peers. International Journal of Early Years Education, 23(4), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2015.1046158

- Peters, S. (2010). Transition from early childhood education to school: Literature review. Ministry of Education. http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/98894?

- Ramstetter, C. L., Murray, R., & Garner, A. S. (2010). The crucial role of recess in schools. Journal of School Health, 80(11), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00537.x

- Robson, S. (2016). Self-regulation and metacognition in young children: Does it matter if adults are present or not? British Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3205

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

- Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 571–645). John Wiley & Sons.

- Sharp, S. (1994). ‘Training schemes for lunchtime supervisors in the United Kingdom: An Overview’. In Blatchford and Sharp (1994) breaktime and the school: Understanding and changing playground behaviour (pp. 118–133). Routledge.

- United Nations. (1989). United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), http://www.unicef.org.uk/publications/pub_detail.asp?pub_id=133

- Varghese, P. (2019). Scaffolding Children’s Friendships and social relationships in a primary school in England. In F. Armstrong & D. Tsokova (Eds.), Action research for inclusive education (pp. 43–56). Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications : Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.