ABSTRACT

The quality of romantic relationships is associated with mental health and wellbeing throughout the life course. A number of programmes have been developed to support young people in navigating healthy relationships, and a larger role for relationship education was recently formalised in statutory guidance in England. This study aimed to systematically review the evidence base for relationship education programmes. Evaluations of relationship education programmes for young people, including charting of outcome domains and measures, were reviewed, followed by a focussed synthesis of data from studies that included outcome domains of relevance to healthy relationships. Thirty-six studies of seven programmes were found that focussed on one or more outcomes relating to healthy relationship skills, knowledge and attitudes, none of which were assessed as high quality. All evaluated programmes were developed in the US, and only one evaluation was conducted in the UK. The evaluations had a diverse set of outcome domains and outcome measures, few had longitudinal measures. No evidence was found for young people’s involvement in programme or evaluation development. High-quality longitudinal evaluations and a core set of validated outcome measures are needed. This research also highlights the need to co-create programmes with young people, teachers and relationship experts that are feasible, acceptable and integrated into a mental health-informed curriculum

Introduction

Romantic relationships are associated with health throughout the life course, including with outcomes, such as high blood pressure and obesity (Bennett-Britton et al., Citation2017; Leach et al., Citation2013; Robles et al., Citation2014). For many young people in late adolescence, negotiating early romantic relationships is a key developmental task, the success of which also influences mental health and wellbeing. Research suggests that good-quality relationships can enhance well-being for young people, and their absence over the longer-term is associated with loneliness and reduced satisfaction (Avilés et al., Citation2021; Gómez-López et al., Citation2019). Conversely, ‘low-quality’ relationships, such as those with higher levels of conflict, lower sense of control and lack of ‘authenticity’ appear to have a negative impact, particularly on symptoms of depression amongst adolescent girls (Gómez-López et al., Citation2019; Kansky & Allen, Citation2018).

Despite this, relationship education focussed on healthy relationships has historically featured less prominently in school health curricula. In England, sex and relationship education has previously been described as placing too much emphasis on the mechanics of reproduction and too little on relationships (Ofsted, Citation2013), with many of the manualised relationship education programmes having been developed in the United States (US; Janssens et al., Citation2020)Note 1. Over time, there has been increasing interest in a larger role for relationship education, which was formalised by the Department for Education (DfE) under statutory guidance (DfE, Citation2019). This guidance mandates that

Note 1. This review updates (Janssens et al., Citation2020) from 2018 to 2021, charts evaluation study domains and measures, and synthesizes the evidence for programme effectiveness.

Young people should learn: ‘how to recognise the characteristics and positive aspects of healthy one-to-one intimate relationships, which include mutual respect, consent, loyalty, trust, shared interests and outlook, sex and friendship’ (DfE, Citation2019, p. 29).

Janssens et al.’s (Citation2020) systematic review identified 17 different relationship education programmes for young people aged 11–18 years, with most combining an element of promoting healthy sexual choices alongside knowledge and skills for healthy relationships, and some with a specific focus on promoting long-term relationships or marriage. However, many programmes focussed to a greater or lesser extent on sexual health or violence prevention rather than on healthy relationships (Janssens et al., Citation2020). Prior meta-analyses of relationship education programmes targeted at young people (McElwain et al., Citation2017; Simpson et al., Citation2018) have reported moderate effect sizes in terms of changing attitudes and beliefs and in the development of conflict management skills. These studies pooled findings from peer-reviewed studies across a heterogeneous range of programmes and outcomes, potentially missing evaluations which exist in the grey literature, likely with this type of intervention (Adams et al., Citation2016; Janssens et al., Citation2020).

This review forms part of a wider Wellcome Beacon project ‘Transforming relationships and relationship transitions with and for the next generation: Healthy Relationship Education (HeaRE) and Transitions (HeaRT)’ (Wellcome. Beacon: Healthy Relationships, Citation2021). The main purpose of the review was to identify 1) how programmes are being evaluated and 2) the outcome domains and measures used, including searches of grey literature to provide a broader overview of the nature of the evidence base, and the evidence by programme. Such an information is important to allow policymakers and commissioners in public health and education and education professionals to consider which programmes might be suitable for adaptation or use in their population, and to determine to what extent programmes are successful in addressing the priorities of young people and those that care for them. By describing the outcome domains and measures commonly used in these evaluations, this review also intends to contribute to further development of the evidence base by informing refinement of measures or core outcome sets.

The aims were:

To update the previous review by Janssens et al. (Citation2020) to identify other healthy relationship education programmes developed after 2018.

To identify and chart evaluations of healthy relationship education programmes and describe the outcome domains and outcome measures used.

To synthesise the evidence for effectiveness in relationship education programmes which included outcomes relating to healthy relationship knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted in three stages.

Stage 1: update review of healthy relationship education programmes

The earlier review by Janssens et al. (Citation2020) was updated to identify new programmes meeting their original criteria published between 2018 and 2021. The search strategy (with minor adaptations to allow for database changes) and inclusion and exclusion criteria were replicated from the previous review (available in the supplementary material [strategy S1]). This resulted in a master list of ‘candidate programmes’ including those from the original review and from this update search.

Stage 2: systematic review of evaluations

Search strategy

We searched for evaluations of the ‘candidate programmes’ in the following databases: ASSIA, Web of Knowledge, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (NHS Evidence), Medline, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Educational Resource Information Centre. The search strategy used terms for the candidate programmes, terms to describe the population group of young people, and terms to describe evaluations (see S1 for the full strategy and terms). We identified and searched relationship education programme websites, along with Lesson Planet, VET-Bib, Isidore, Social Science Research Network, Google, and Google Scholar, as well as contacting programme developers, and backward and forward citation chasing.

Inclusion criteria and study selection

Only evaluations of the candidate programmes as defined in stage 1 were included. Other inclusion criteria were age (at least 80% of participants aged between 11 and 18 years) and setting (school, college, or community). We included any study with primary data aiming to evaluate feasibility, impact, implementation, or effectiveness of the relationship education programme, including process evaluations, published between 2000 and June 2021 in the English language. Screening followed a two-stage process, involving abstract and full-text screening by two independent reviewers (SBC, GR, TND, RJ). Disagreements were resolved by a discussion involving a third reviewer.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each evaluation: authors, year, population (including age, gender and other characteristics), number of participants, setting, design of evaluation, intervention delivered (details of programme: number of sessions, content, any adaptations made, duration), comparison group (if any), broad outcome domain as described in the study (e.g. teenage pregnancy, self-efficacy, etc.), and specific outcome measures used.

Stage 3: synthesis

The data extracted were narratively synthesised in two stages, using a tiered synthesis approach similar to that described by Adams et al. (Citation2016). This involved a) a synthesis of the outcome domains and measures used in the evaluation studies identified in stage 2, followed by b) a focussed synthesis of data from those evaluation studies that included outcome domains of relevance to healthy relationships, as defined below.

Charting of outcome domains and measures

Data extracted from each evaluation were summarised in a charting spreadsheet. Two reviewers (SBC and TND) independently categorised the measures used in each study according to the description of the knowledge, skill, attitude, behaviour or other outcome that it intended to measure. Drawing on any theory (e.g. behaviour change) described in the evaluation, the reviewers then followed an iterative process of grouping the broad outcome domains targeted in each evaluation.

Focussed synthesis

From the charting process, evaluations were identified which targeted and measured outcomes relating to healthy relationships knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours. Those evaluation studies which predominantly focussed on outcomes related to sexual health (e.g. teenage pregnancy or abstinence), or violence and abuse without also including a healthy relationship component, were excluded from the focussed synthesis. The inclusion and exclusion decisions were taken independently by two reviewers (TND and SBC) and resolved by discussion. Data from these selected programme evaluations relating to the outcomes above were extracted. Studies were appraised for quality, using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPPI) Centre quality assessment tool (Thomas et al., Citation2004), and independently graded by two reviewers (TND and SBC) as either weak, moderate or strong based on the rating on the checklist and any additional factors identified. The findings and quality ratings were then tabulated and synthesised, drawing together the studies which evaluated each programme.

Results

Update search

Three new programmes: Lights4Violence/”Cinema Voice” (Vives-Cases et al., Citation2019), Healthy Relationship Campaign (HRC; Guillot-Wright et al., Citation2018) and Piecing Together Behaviors of Healthy Relationships lesson plans (Shipley et al., Citation2018) were found. When combined with those found by Janssens et al. (Citation2020), the number of relationship education programmes now totalled 20. The list of included programmes is presented in . The PRISMA is available in Figure S1.

Table 1. Evaluations identified by programme (n = 36).

Systematic review of evaluations

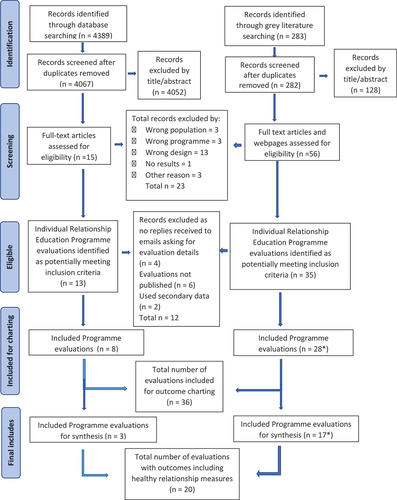

The database search yielded 4389 individual evaluations, and 283 additional records were identified through grey literature searches. Following full-text screening, a total of 36 studies were found that both evaluated the candidate programmes and met inclusion criteria for charting outcome domains and measures (). Eight of these came from the database search, and 28 via the grey literature search.

Characteristics of evaluations

Whilst most programmes were the subject of multiple evaluations (Relationship Smarts/Love U2 (16 studies), Connections: Relationships and Marriage (7), Choosing the Best (3), LOVEBiTES (2), LoveNOTES (2), Teen choices (2), PICK (1), Connections: Dating and Emotions (1), Positive Choices (1), What’s Real (1), we found no published evaluations for 9 of our candidate programmes (), see intervention characteristics in Table S1.

The majority of evaluations took place in the US (n = 33), with two in Australia and one in the UK. Most programmes were evaluated in educational settings such as schools and colleges (n = 28). The age of participants included ranged from 11 to 20 years, although the majority within each evaluation were aged between 11 and 18 years as per the inclusion criteria. The most commonly used study design was a pre-test post-test design with a control group (n = 14). The majority of evaluations only collected outcome data immediately post-intervention, i.e. after a class or a series of classes had ended (n = 15). Only one study included a process evaluation focussing on feasibility and acceptability of the intervention (Bragg et al., Citation2021).

Charting of outcome domains and measures

Evaluations were often not explicit about the constructs being targeted or measured (see Discussion). Our charting identified 13 broad outcomes targeted and measured in the 36 evaluations, described in (see outcome measures in Table S2). The most frequently measured outcome domain was conflict (16 evaluations) which included both positive (e.g. negotiation and reasoning) and negative (e.g. aggression) behaviours. Ten of the 36 evaluations targeted outcomes related to violence and abuse within relationships, these were differentiated from conflict due to their specific focus on violent behaviours and beliefs about violence. Many evaluations focussed on attitudes towards cohabitation, marriage and divorce; these were grouped together. ‘Help-seeking’ was another outcome which related to attitudes towards relationship counselling or seeking of other forms of support for relationships, and marriage in particular. Studies also included measures that assessed learning and progress aspects of the respective curriculum but were not clearly defined or too broad to be included in other outcome domains or form a separate domain, so we have grouped these as ‘curriculum focussed’. Other domains identified by the charting were communication, sexual health, relationship beliefs and values, connectedness, and parental caregiving beliefs.

Table 2. Outcome domains measured in programme evaluations.

A variety of measures were used in the charted evaluations (details in S2). These ranged from validated measures, such as Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, Citation2015), adapted measures such as Gardner et al.’s (Citation2004) adaptation of the conflict tactics scale (Straus, Citation1979) and bespoke measures or questionnaires designed specifically for the programme evaluation such as in McBride et al. (Citation2011). The most common validated measures were the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, Citation2015), used in three evaluations, versions of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Citation1979; Straus et al., Citation1996), used in five evaluations, and the Attitudes Towards Counselling scale (Gardner, Citation2001; Gardner et al., Citation2004), used in four evaluations. All were completed by the participating young people.

Evaluations addressing healthy relationship skills, knowledge and attitudes

Of the 36 evaluations charted, only 18 were assessed as focussing on one or more outcomes relating to healthy relationship skills, knowledge and attitudes, presented in Table 3. All took place in the US except for the Australian-based LOVEBiTES evaluation, were predominantly set in high-school health education (or Family and Consumer Science (FCS)) classes, and most commonly included those in mid-to-late adolescence, targeting those aged 14–15 and over rather than younger students. Across all evaluations, 37 bespoke outcome measures were used, 14 were adapted by the evaluation authors from existing measures and the remaining 15 used pre-existing scales (note that some measures were used across different evaluations). None of the studies were judged to be of high quality. The majority of studies were judged to be of low quality, due to low response rate, high attrition, no attempts at blinding, and poor reporting of characteristics and design.

Evaluations of the connections programmes

Our review identified five evaluations which assessed a version of the Connections programme (Relationships and Marriage; Dating and Emotions) (Table S3). Those reporting on post-course measures found little evidence of intervention effects, although Gardner et al. (Citation2004) reported a small improvement in knowledge scores; an increase in reported intention to engage in marriage preparation and favourable attitudes to marriage. An evaluation of followed-up participants for four-year post-programme, with considerable attrition, finding an increase in self-esteem scores had been maintained in the intervention group (Gardner & Boellaard, Citation2007).

Evaluations of the Love U2/Relationship smarts/Relationship smarts plus programme

Nine evaluations studied an iteration of this programme (Table S3); with variable delivery. This programme appeared to be used with more selective samples of participants and settings, such as groups of young people described as ‘high-risk’ in various ways (e.g. Antle et al. (Citation2011)) or in community or after-school settings. A diverse range of outcome measures were used, with little overlap between studies.

Evaluations of other programmes: LOVEBiTES, teen choices and PICK

We found one evaluation for each of LOVEBiTES, PICK and Teen Choices. The evaluation of the Teen Choices programme (Levesque et al., Citation2016b) was the only cluster RCT included in our synthesis and was of moderate quality. The trial included a selected sample of young people who were either dating or had been assessed as at risk of relationship violence, and the majority of measures focussed on these outcomes. The exception was a measure of ‘consistent use’ of five healthy relationship skills involving communication, managing conflict and decision-making; Teen Choices was associated with significantly higher odds of consistently using these healthy relationship skills at 6 and 12 months.

Discussion

This review identified three relationship programmes which had become available since 2018, bringing the total number of programmes to 20. All but one were developed in the US, suggesting that despite the increased attention paid to the relationship element of sex and relationships education, there still appears to be a lack of formal programmes being developed in settings outside of the US. No evaluations were found that took place in a European context, in line with previous reviews in this topic area (Simpson et al., Citation2018), and we found no evaluations available for nine of the 20 programmes.

Our review found diversity in outcome domains and outcome measures, reflecting differences both in what the programmes aimed to achieve and in how these outcomes were conceptualised and measured. Whilst many programmes stated they aimed to develop skills for healthy relationships, evaluations used a range of assessments including knowledge about healthy relationships, measures of attitudes towards behaviours, reported behaviours and levels of confidence in the use of skills (for example, ‘I can’ statements). These might be considered to represent proxies for the more challenging task of determining whether programmes improve young people’s skills in the targeted domains such as conflict management and communication, for example, through observations from peers, teachers or parents.

There are some similarities here with the literature around Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEL/SEAL); which is, to some extent, a building block for later RSHE. Evaluations and reviews in this area have reported a disconnect between SEL skills addressed by studied interventions, and the outcomes measured (Taylor et al., Citation2017; Ura et al., Citation2020), and called for core sets of outcome measures which identify skill growth across domains over time (Ura et al., Citation2020). Learning in relational skills and behaviours are typically incremental, aligning with children and young people’s development, which is reflected in the use of spiral curriculums which build on earlier learning. The majority of programmes are based on theories that more proximal changes in knowledge, skills or attitudes impact future ‘healthy relationships’, however defined, but we found only three evaluations which followed-up participants for a year or longer.

Programmes should also be judged on how well they achieve the outcomes desired by the participants. Many programmes and evaluations did not appear to be co-developed or designed with young people. Whilst views on sex education have been more heavily researched (e.g. Pound et al., Citation2016), little is known about how young people view the relationships aspect of the curriculum, or what they feel it should deliver for them in terms of outcomes; this is crucial for engaging young people in this type of personal development (World Health Organization, Citation2020). The quality of relationships young people have effects them, and these are difficult to understand without their first-hand accounts. Previous and current work by the authors (Barlow et al., Citation2018; Benham-Clarke et al., In review) begins to explore this finding that young people want their voices heard and along with relationship experts see relationship education as having an important role in promoting good mental health and wellbeing, particularly through learning to cope with relationship breakdowns. They also prioritised skills around maintaining happy and healthy relationships over the longer term.

Programme content and theoretical/philosophical basis itself was not the focus of this review, but it is notable that many of the evaluations included outcomes related to attitudes towards marriage, divorce and cohabitation (Gardner, Citation2001; Gardner & Boellaard, Citation2007; Gardner et al., Citation2004; Schramm & Gomez-Scott, Citation2012; Sparks et al., Citation2012) and that more negative attitudes to divorce and cohabitation were framed as positive outcomes (e.g. as in Gardner, Citation2001; Schramm & Gomez-Scott, Citation2012), which suggests underlying cultural, political or religious stances towards relationships. Where RSHE programmes make explicit value judgements about behaviours in relationships, participants may also gauge this and respond accordingly (Scott et al., Citation2012). As evaluations are predominantly US focussed, it is likely that these reflect concerted efforts within many US states to strengthen marriage as a route to improving health and prosperity (Trail & Karney, Citation2012), which is also likely to be reflected in outcome measures on abstinence and delaying sexual intercourse.

Considering internal validity, in general, the quality of evaluations was low, with one or two exceptions, such as a cluster RCT of the Teen Choices programme (Levesque et al., Citation2016a). The most common limitations included a lack of randomisation, unbalanced samples and high attrition rates. Most used a US high-school population of students attending FCS (or similar classes focussing on personal health and development), where there was often a large female preponderance, due to these classes being optional. Outcomes were usually self-reported by unblinded students, which is likely to lead to bias, particularly with measures involving self-rated changes in knowledge or behaviours. Consequently, although the evidence base for some programmes included studies reporting largely positive impacts on measures such as relationship beliefs, expectations and knowledge (e.g. Relationship Smarts/Love U2), the quality of the evidence means that confidence in this effect is low.

We found that high-quality research into aspects of feasibility, acceptability and implementation is a significant gap, which is even more important given the myriad contextual factors at play and the reliance on school staff for the delivery of most programmes studied (Pearson et al., Citation2015).

Strengths and limitations

The inclusion of grey literature is a strength of the review because it identifies a wider range of literature and current research and evaluations. We made efforts to contact programme designers and evaluators, although we were unable to gather missing information in all instances. However, the inclusion of grey literature also meant including posters, proceedings, or online reports, where there was often limited information with which to appraise quality or extract data on the programme, methods or findings. Our approach to the review also required that we make decisions on inclusion, exclusion and categorisation based on our judgements as to the constructs targeted by programmes and outcome measures; this was challenging in the light of often limited information and lack of explicit framing or theory in many evaluations.

Implications for research and practice

It is not possible to conclude that any of the individual candidate programmes have a strong evidence base in terms of their proximal or distal impacts on relationships skills or healthy relationship outcomes, particularly over the longer term. One obvious implication is the need for more robust trials with longer-term follow-up. A second is the need to co-develop a core set of validated outcome measures which connect more directly to the desired outcomes of relationship education programmes and reflect the priorities of participants. The findings of the evaluations also need to be considered in their educational and societal contexts; as such, process evaluations are needed to support and sustain successful implementations in different schools and communities, where the necessary support and capacity is often missing (Craig et al., Citation2008; Oberle et al., Citation2016).

Further, there is a more fundamental question about the extent to which such programmes are feasibly or even desirably delivered or evaluated on a ‘stand-alone’ basis. From a public health perspective, relationship education form parts of a much wider system of health promotion and prevention interventions (World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2021). Within schools, this can build on SEL and links to and complements mental health informed and inclusive curricula, as well as other aspects of RSE such as sex education and prevention of violence and abuse, but in England, as in many other countries, much of the content and delivery is left to the discretion of schools (DfE, Citation2019). A recent survey of schools in England by Ipsos MORI and the PSHE Association (Ipsos MORI and the PSHE Association, Citation2021) suggests that schools faced barriers in terms of knowledge, training and resources to delivery of relationship education. Many reported using a tailored approach based on resources and expertise available, rather than using formal programmes. For example, schools reported bringing in third-sector organisations to deliver sessions and drawing on resources and lesson plans developed by organisations such as the PSHE Association (https://www.pshe-association.org.uk/). Consequently, relationship education and evaluation of programmes may lend itself to an ‘active ingredients/core components’ approach, which is sensitive to the settings and constraints, and is co-produced with education professionals and young people, as has been recommended for school mental health programme evaluations (Wignall et al., Citation2021). These approaches are being increasingly used across evaluations of SEL programmes, as well as in broader risk prevention programmes for adolescents (Abry et al., Citation2017; Lawson et al., Citation2019; Skeen et al., Citation2019). Co-production is also likely to increase acceptability and take-up of any resources designed and tested, which need to be available and presented in a user-friendly format.

Conclusions

This review provides knowledge of the relationship education programmes and the evaluations that exist. As well as their content, appraisal of their quality, their outcome measures and where they were conducted. The evaluations had a diverse set of outcome domains and outcome measures, few had longitudinal measures and only one evaluation was conducted in the UK. Whilst research indicates a clear link between healthy relationships and an array of health and social outcomes, this demonstrates that the evidence base for existing healthy relationship education programmes in improving such outcomes is lacking. High-quality longitudinal evaluations and a core set of validated outcome measures are needed. Further, no evidence was found for young people’s involvement in programme or evaluation development. To improve relationship outcomes for young people it is critical that they are fully engaged in the development of new evidence. Therefore, research is needed to co-create programmes with young people, teachers and relationship experts that are feasible, acceptable and integrated into a mental health-informed curriculum and wider prevention programmes in schools and communities. This is likely to advance the evidence and practice further in this field and improve outcomes for young people.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (209.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abry, T., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Curby, T. W. (2017). Are all program elements created equal? Relations between specific social and emotional learning components and teacher–student classroom interaction quality. Prevention Science, 18(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0743-3

- Adams, J., Hillier-Brown, F. C., Moore, H. J., Lake, A. A., Araujo-Soares, V., White, M., & Summerbell, C. (2016). Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: Critical reflections on three case studies. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0337-y

- Adler-Baeder, F. (2005). Looking towards a healthy marriage: School‐based relationships education targeting youth. College of Human Sciences, Auburn University. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/Documents/Love_school_relations.pdf

- Adler-Baeder, F., Savasuk, R., Ketring, S., Smith, T., & Kerpelman, J. (2015). Findings for youth participants in relationship education (RE) 2011-2015 Alabama healthy marriage and relationship education initiative Auburn University. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/wp-new/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Findings-for-Youth-Participants-in-Relationship-Education.pdf

- Adler‐Baeder, F., Kerpelman, J. L., Schramm, D. G., Higginbotham, B., & Paulk, A. (2007). The impact of relationship education on adolescents of diverse backgrounds. Family Relations, 56(3), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00460.x

- Antle, B. F., Sullivan, D. J., Dryden, A., Karam, E. A., & Barbee, A. P. (2011). Healthy relationship education for dating violence prevention among high-risk youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(1), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.031

- Avilés, T. G., Finn, C., & Neyer, F. J. (2021). Patterns of romantic relationship experiences and psychosocial adjustment from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(3), 550–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01350-7

- Barbee, A. P., Cunningham, M. R., van Zyl, M. A., Antle, B. F., & Langley, C. N. (2016). Impact of two adolescent pregnancy prevention interventions on risky sexual behavior: A three-arm cluster randomized control trial. American Journal of Public Health, 106(S1), S85–S90. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303429

- Barbee, A., van Zyl, R., & Murrah, W. (2012). How embedding sex education in a healthy relationship curriculum could lead to reductions in risky sexual behavior. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/wp-new/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-Embedding-Sex-Education-in-a-Healthy-Relationship-Curriculum-Could-Lead-to-Reductions-in-Risky-Sexual-Behavior.pdf

- Barlow, A., Ewing, J., Janssens, A., & Blake, S. (2018). The Shackleton relationship project report and key findings [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from http://socialsciences.exeter.ac.uk/media/universityofexeter/collegeofsocialsciencesandinternationalstudies/lawimages/familyregulationandsociety/shackletonproject/Shackleton_ReportFinal.pdf1

- Benham-Clarke, S., Ewing, J., Barlow, A., & Newlove-Delgado, T. Forthcoming.

- Bennett-Britton, I., Teyhan, A., Macleod, J., Sattar, N., Smith, G. D., & Ben-Shlomo, Y. (2017). Changes in marital quality over 6 years and its association with cardiovascular disease risk factors in men: Findings from the ALSPAC prospective cohort study. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 71(11), 1094–1100. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209178

- Bradford, A. B., Erickson, C., Smith, T. A., Adler-Baeder, F., & Ketring, S. A. (2014). Adolescents’ intentions to use relationship interventions by demographic group: Before and after a relationship education curriculum. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 42(4), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2013.864945

- Bragg, S., Ponsford, R., Meiksin, R., Emmerson, L., & Bonell, C. (2021). Dilemmas of school-based relationships and sexuality education for and about consent. Sex Education, 21(3), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1788528

- Brower, N., MacArthur, S., Bradford, K., Albrecht, C., & Bunnell, J. (2012). Got dating: Outcomes of a Teen 4-H relationship retreat. Journal of Youth Development, 7 (1), 118–124. https://jyd.pitt.edu/ojs/jyd/article/view/156

- Choosing the Best. (2021). Choosing the best [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from http://choosingthebest.com/curricula

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical research council guidance. Bmj, (pp. 337). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- DfE. (2019). Relationships education, relationships and sex education (RSE) and health education [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education

- The Dibble Insititute (2013). Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/NEWDOCS/Whats-Real-sampleV2.pdf

- DO. (2021). Do SRE for schools [Internet]. Retriev Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dosreforschools.com/

- Dobia, B. (2019). “Every client has a trauma history”: Teaching respectful relationships to marginalised youth. An evaluation of NAPCAN’s respectful relationships program Northern Territory 2017-2018 [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.napcan.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/NAPCAN-Love-Bites-NT-Evaluation.pdf

- Ellenwood, S., McLaren, N., Goldman, R., & Ryan, K. (1993). The art of loving well: A character education curriculum for today’s teenagers. Boston: Boston University.

- Flood, M. ( 212). LOVEBiTES: An evaluation of the LOVEBiTES and respectful relationships programs in a Sydney school (2012) [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.academia.edu/2194697/LOVEBiTES_An_evaluation_of_the_LOVEBiTES_and_Respectful_Relationships_programs_in_a_Sydney_school_2012_

- Futris, T. G., Sutton, T. E., & Duncan, J. C. (2017). Factors associated with romantic relationship self‐efficacy following youth‐focused relationship education. Family Relations, 66(5), 777–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12288

- Futris, T. G., Sutton, T. E., & Richardson, E. W. (2013). An evaluation of the relationship smarts plus program on adolescents in Georgia. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 1(2), 1–15. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/730/631

- Gardner, S. (2001). Evaluation of the ‘‘Connections: Relationships and marriage’’ curriculum. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 19(1), 1–14 . Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/wp-new/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Evaluation-of-the-Connections-Relationships-and-Marriage.pdf

- Gardner, S. P., & Boellaard, R. (2007). Does youth relationship education continue to work after a high school class? A longitudinal study. Family Relations, 56(5), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00476.x

- Gardner, S. P., Bridges, J. G., Johnson, A., & Pace, H. (2016). Evaluation of the What’s real: Myths & facts about marriage curriculum: Differential impacts of gender. Marriage & Family Review, 52(6), 579–597. 10.1080/01494929.2016.1157120

- Gardner, S. P., Giese, K., & Parrott, S. M. (2004). Evaluation of the connections: Relationships and marriage curriculum. Family Relations, 53(5), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00061.x

- Gómez-López, M., Viejo, C., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2019). Well-being and romantic relationships: A systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132415

- Gossett, D., & Hooten, M. A. (2006). An evaluation of a three-year abstinence education program in Southeast Alabama. Alabama Counseling Association Journal, 32(1), 12–21. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ902496.pdf

- Guillot-Wright, S. P., Lu, Y., Torres, E. D., Le, V. D., Hall, H. R., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Design and feasibility of a school-based text message campaign to promote healthy relationships. School Mental Health, 10(4), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9255-6

- Haberland, N., & Rogow, D. (2009). It’s all one curriculum: Guidelines and activities for a unified approach to sexuality, gender, HIV, and human rights education. The Population Council Inc. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from www.itsallone.org

- Halpern-Meekin, S. (2011). High school relationship and marriage education: A comparison of mandated and self-selected treatment. Journal of Family Issues, 32(3), 394–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10383944

- Wellcome. Healthy Relationships. (2021). Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://wcceh.org/themes/transforming-relations/beacon-healthy-relationships/

- Ipsos MORI and the PSHE Association. (2021). RSHE: School practice in early adopter schools. 27 May 2021. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rshe-school-practice-in-early-adopter-schools

- Janssens, A., Blake, S., Allwood, M., Ewing, J., & Barlow, A. (2020). Exploring the content and delivery of relationship skills education programmes for adolescents: A systematic review. Sex Education, 20(5), 494–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1697661

- Kamper, C. (2021a) Dibble Institute. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/store/connections-dating-emotions

- Kamper, C. (2021b). Dibble institute. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/store/connections-relationships-marriage/

- Kamper, C. (2021c). Dibble institute. Retrieved 11th November from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/our-programs/healthy-choices-healthy-relationships/#1567669604788-e0bad883-2b318374-fce8

- Kansky, J., & Allen, J. P. (2018). Making sense and moving on: The potential for individual and interpersonal growth following emerging adult breakups. Emerging Adulthood, 6(3), 172–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696817711766

- Kanter, J. B., Lannin, D. G., Russell, L. T., Parris, L., & Yazedjian, A. (2021). Distress as an outcome in youth relationship education: The change mechanisms of hope and conflict. Family Relations, 70(1), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12497

- Kerpelman, J. (2007). Youth focused relationships and marriage education, Forum of Family Consumer Issues [Internet], 12(1), 1–13. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from http://ncsu.edu/ffci/publications/2007/v12-n1-2007-spring/index-v12-n1-may-2007.ph

- Kerpelman, J. L. (2010). The youth build USA evaluation study of love notes.Making relationships work for young adults and young parents [Internet]. YouthBuild USA. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/Documents/YBUSA-Love-Notes-Evaluation-report-2010.pdf

- Lawson, G. M., McKenzie, M. E., Becker, K. D., Selby, L., & Hoover, S. A. (2019). The core components of evidence-based social emotional learning programs. Prevention Science, 20(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0953-y

- Leach, L. S., Butterworth, P., Olesen, S. C., & Mackinnon, A. (2013). Relationship quality and levels of depression and anxiety in a large population-based survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0559-9

- Levesque, D. A., Johnson, J. L., & Prochaska, J. M. (2016a). Teen Choices, an online stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships: Development and feasibility trial. Journal of School Violence, 16(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2016.1147964

- Levesque, D. A., Johnson, J. L., Welch, C. A., Prochaska, J. M., & Paiva, A. L. (2016b). Teen dating violence prevention: Cluster-randomized trial of teen choices, an online, stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships. Psychology ofViolence, 6(3), 421. doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=doi:10.1037/vio0000049

- Lieberman, L., & Su, H. (2012). Impact of the choosing the best program in communities committed to abstinence education. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012442938

- Ma, Y., Pittman, J. F., Kerpelman, J. L., & Adler‐Baeder, F. (2014). Relationship education and classroom climate impact on adolescents’ standards for partners/relationships. Family Relations, 63(4), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12084

- McBride, C., Miller, C., & Vorderstrasse, V. (2011) Relationship skills for adolescents: Health promotion through a college service learning course [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/wp-new/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Roosevelt-U-poster.pdf

- McElwain, A., McGill, J., & Savasuk-Luxton, R. (2017). Youth relationship education: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.036

- Oberle, E., Domitrovich, C. E., Meyers, D. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Establishing systemic social and emotional learning approaches in schools: A framework for schoolwide implementation. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(3), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2015.1125450

- Ofsted. (2013). PSHE education in schools: Strengths and weaknesses [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/not-yet-good-enough-personal-social-health-and-economic-education

- Pearson, M. (2004). LoveU2: Getting smarter about relationships. The Dibble Fund for Marriage Education [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/our-programs/relationship-smarts-plus-classic/#1567669608083-f7be66bf-3bd80ffc-bb4b

- Pearson, M. (2021). Love notes 3.0 classic – healthy relationship skills. The Dibble Institute. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/our-programs/love-notes-classic/#1567669608083-f7be66bf-3bd8

- Pearson, M., Brand, S. L., Quinn, C., Shaw, J., Maguire, M., Michie, S., Byng, R., Lennox, C., Stirzaker, A., Kirkpatrick, T., & Byng, R. (2015). Using realist review to inform intervention development: Methodological illustration and conceptual platform for collaborative care in offender mental health. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0321-2

- Pittman, J. F., & Kerpelman, J. L. (2013). A cross-lagged model of adolescent dating aggression attitudes and behavior: Relationship education makes a difference. In: Published Proceeding, Hawaii International Social Science Conference, Waikiki, HI [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/NEWDOCS/A-Cross-lagged-Model-of-Adolescent-Dating-Aggression-Attitudes-and-Behaviors.pdf

- Ponsford, R., Bragg, S., Allen, E., Tilouche, N., Meiksin, R., Emmerson, L., … Bonell, C. (2021). A school-based social-marketing intervention to promote sexual health in English secondary schools: The positive choices pilot cluster RCT. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr09010

- Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ open, 6(9), e011329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

- Relationships Victoria. (2020). I like, like you. A healthy intimate relationships program for schools [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.relationshipsvictoria.com.au/assets/PDFs/Booklets/RAV-ILLY-Promotions-Booklet-16096-Small.pdf%0A%0A

- Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031859

- Rosenberg, M. (2015). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press.

- Santabarbara, T., Erbe, R., & Cooper, S. (2009). Relationship building blocks. Journal of School Health, 79(10), 505–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00440.x

- Savasuk-Luxton, R. (2018). Examining Potential Pathways to Adolescent Dating Violence and the Impact of Youth Relationship Education on Common Correlates of Adolescent Dating Violence [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://etd.auburn.edu/bitstream/handle/10415/6154/Savasuk-Luxton_Dissertation.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Schramm, D. G., & Gomez-Scott, J. (2012). Merging relationship education and child abuse prevention knowledge: An evaluation of effectiveness with adolescents. Marriage & Family Review, 48(8), 792–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2012.714722

- Scott, M. E., Moore, K. A., Hawkins, A. J., Malm, K., & Beltz, M. (2012). Putting youth relationship education on the child welfare agenda: Findings from a research and evaluation review. Child Trends. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/2012-47RelationshipEducFullRpt1.pdf

- Selman, R. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding: Developmental and clinical analyses developmental psychology series. Academic Press. 343 p.

- Shipley, M., Holden, C., McNeill, E. B., Fehr, S., & Wilson, K. (2018). Piecing together behaviors of healthy relationships. Health Educator, 50(1), 24–29. Retrieved 11th November 2021. from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1196102

- Simpson, D. M., Leonhardt, N. D., & Hawkins, A. J. (2018). Learning about love: A meta-analytic study of individually-oriented relationship education programs for adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(3), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0725-1

- Skeen, S., Laurenzi, C. A., Gordon, S. L., du Toit, S., Tomlinson, M., Dua, T., and Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2019). Adolescent mental health program components and behavior risk reduction: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 144(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3488

- Sparks, A., Lee, M., & Spjeldnes, S. (2012). Evaluation of the high school relationship curriculum connections: Dating and emotions. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-011-0244-y

- Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/351733

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-mccoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001

- Szucs, L., Reyes, J. V., Farmer, J., Wilson, K. L., & McNeill, E. B. (2015). Friend flips: A story activity about relationships. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 10(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2015.1049313

- Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school‐based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

- Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(3), 176–184. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-011-0244-y

- Toews, M. L., & Yazedjian, A. (2010). “I learned the bad things I’m doing”: Adolescent mothers‘ perceptions of a relationship education program. Marriage & Family Review, 46(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2010.490197

- Toews, M. L., Yazedjian, A., & Jorgensen, D. (2011). “I haven’t done nothin’ crazy lately:” Conflict resolution strategies in adolescent mothers’ dating relationships. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(1), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.09.001

- Trail, T. E., & Karney, B. R. (2012). What’s (not) wrong with low‐income marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00977.x

- Trella, D. (2009). Relationship smarts: Assessment of an adolescent relationship education program [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/WP/WP-09-12.pdf

- Ura, S. K., Castro-Olivo, S. M., & d’Abreu, A. (2020). Outcome measurement of school-based SEL intervention follow-up studies. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 46(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508419862619

- Utmb Health. (2021). Healthy relationships Campaign [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.utmb.edu/bhar/4r-prevention/healthy-relationships-campaign

- Van Epp, J. (2006). How to avoid marrying a jerk: The foolproof way to follow your heart without losing your mind. McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Vives-Cases, C., Davó-Blanes, M. C., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Sanz-Barbero, B., Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Sánchez-San Segundo, M., Corradi, C., Bowes, N., Neves, S., Mocanu, V., Carausu, E. M., Pyżalski, J., Forjaz, M. J., Chmura-Rutkowska, I., Vieira, C. P., & Corradi, C. (2019). Lights4Violence: A quasi-experimental educational intervention in six European countries to promote positive relationships among adolescents. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6726-0

- Walsh, A., & Peters, T. (2011). NAPCAN’S ‘Growing respect’ [Internet]. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from http://www.awe.asn.au/drupal/sites/default/files/NAPCANs Growing Respect Program for Primary and Secondary Schools_0.pdf

- Weed, S., & Anderson, N. (2005). Evaluation of choosing the best. Unpublished manuscript Retrieved 11th November 2021 from http://www.choosingthebest.org/research_results/indexhtml

- Wignall, A., Kelly, C., & Grace, P. (2021). How are whole-school mental health programmes evaluated? A systematic literature review, Pastoral care in education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2021.1918228

- World Health Organization (2020). Engagement and participation for health equity. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/353066/Engagement-and-Participation-HealthEquity.pdf

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school: Global standards and indicators for health-promoting schools and systems. Geneva: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Retrieved 11th November 2021 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341909/9789240025431-eng.pdf