ABSTRACT

School mediation is a peacekeeping, conflict-resolution procedure. Evaluating mediation processes allows us to assess their effects through their participants. This systematic review of studies of school mediation aims to study what evidence exist on its educational benefits for teacher mediators, student mediators, and mediated students. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method was followed to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the results. In total, 524 were initially identified, of which 141 were retained after screening. Of these, 32 studies were published from 2000 to 2020. The studies were analyzed according to their statistical design. In addition, their results were summarized along the following dimensions: interpersonal emotional, personal emotional, cognitive-moral, and social impact. School mediation has a personal impact that increases the likelihood of acting constructively and positively when facing conflicts.

Introduction

Every student needs to learn how to manage conflicts constructively. Without training, many students may never learn how to do so (…) The more years students spend learning and practicing mediation procedures, the more likely they will be to use the procedures skillfully both in the classroom and beyond the school door. (Johnson & Johnson, Citation2002, p. 37)

A democratic society and responsible citizenship must empower future generations socially and emotionally. Conflict resolution education in childhood and adolescence should be considered an educational tool for social transformation given its considerable potential for the present and future of societies. The desire for peace may require specific educational strategies, such as school mediation, which can be integrated into ordinary school life.

School mediation is defined as ‘a conflict resolution procedure that consists of the intervention of a third party, outside and impartial to the conflict, accepted by the disputants and without decision-making power over them, with the objective of facilitating that the parties in litigation reach an agreement by themselves through dialogue’ (Jares, Citation2006, p. 111).

As Torrego (Citation2003) verifies, different definitions of school have the following in common: mediation as a process in which the protagonists of an interpersonal conflict transform it by themselves, with the intervention of a third party (chosen or accepted by it), which contributes from its impartiality, confidentiality and competence as a mediator.

When reviewing school intervention in conflicts and interpersonal problems, two main approaches are differentiated: the punitive approach and the educational approach. Broadly speaking, according to Sullivan (Citation2000), the punitive approach consists of imposing a punishment for an action considered a foul. This approach is remedial, focused on the individual and the corresponding punitive sanction. From an educational approach, the intervention is to remedy and prevent. This takes into account interpersonal relationships and the context in which they occur, including the offending student and the people the offend.

School mediation is part of the educational approach. However, data from educational research shows that both approaches coexist in a school (Díaz-Aguado et al., Citation2021; Torrego, Citation2006). Elements of one approach or another may prevail depending on the culture of the school. For this reason, opposition to mediation may arise within a school. For example, some teachers nonetheless remain skeptical about school mediation or avoid intervening in conflicts if the necessary approach to do so is not shared. Their practice requires understanding and acceptance of the educational model. An educational approach – in accordance with the orientation model for prevention and development (Bisquerra, Citation1992; Miller, Citation1971)- does not forget the correction of deviant behaviors. But at the same time, it includes primary prevention and proposes measures aimed at both, personal development and the achievement of quality environment. For this, it has the participation of different professionals and areas of the school. It enables and indeed invites us to regard conflicts as opportunities for dialogue.

This study focuses on the evaluation of school mediation. Programs and experiences have become increasingly available in recent years, but there has not been a systematic evaluation of their quality. Accordingly, this study aims to review the literature more comprehensively and with a more accurate methodology to gather evidence less susceptible to bias.

Background

Research on this issue has been reviewed previously. Review studies or meta-analyses of the effects of conflict-resolution education on students were searched. Thus, in addition to these studies (Garrard & Lipsey, Citation2007; Jones & Kmitta, Citation2000), only those that include school mediation are highlighted below:

Wilson et al. (Citation2003) conducted a meta-analysis of the effects of different aggressiveness prevention programs. All programs had a positive impact on aggressive behaviors, but school mediation programs had lower and inconsistent results due to their limited availability.

In line with the above, Turk (Citation2018) assessed the effects of conflict-resolution education, education for peace, and school mediation on primary and secondary school and university students’ conflict-resolution skills. Her meta-analysis compiled 23 studies conducted in Turkey from 2003 to 2016, of which school mediation was included in 11. All programs, even those with different approaches, had a similar level of impact and were effective in developing individual conflict-resolution skills, albeit with a larger effect size in primary education.

Both meta-analyses focused on the impact of training through programs. However, not only the impact of training but also the experiential learning resulting from participating in a real mediation process should be considered. By conducting her study from such a perspective, Turk (Citation2018) highlights the importance of distinguishing between acquiring mediation skills and actually using them in everyday situations.

The school mediation works on emotions, thoughts, perceptions, and abilities from one’s own experiences and rooted in the most immediate personal reality (Ortega & Del Rey, Citation2004; Ortega & Mora-Merchán, Citation2005). Destructive situations are transformed into learning and personal growth opportunities. This learning is particularly effective in terms of retention and subsequent application (Cowie & Wallace, Citation2000).

Similarly, the meta-analysis by Johnson and Johnson (Citation2002) demonstrated that students who learn how to mediate conflicts between their peers in the program entitled Teaching to Be Peacemakers apply these skills in real conflicts (effect size = 2.16) even months later (effect size = 0.46). The analysis of interviews with their parents also showed that the students used these skills outside the school context. In turn, the teachers perceived an improvement in the classroom environment.

Burrell et al. (Citation2003) conducted a meta-analysis of the benefits of both mediation training and practice in which they selected 43 quantitative studies, published from 1985 to 2003, examining the efficacy of school mediation and its impact on the participants’ perception of interpersonal conflict and their training in mediation.

On the one hand, the results indicated that, thanks to their training, the students had acquired a higher degree of knowledge and a more positive perception of interpersonal conflicts by learning steps and strategies to resolve them. On the other hand, after participating in mediations throughout the school year, self-esteem (r = 0.110, k = 4, N = 237, p < 0.05) and academic performance (r = 0.341, k = 5, N = 297, p < 0.05) significantly improved among mediators. Similarly, the students, teachers, and non-teaching staff members’ perception of the school environment improved in general (r = 0.441, k = 4, N = 443, p > 0.05), particularly regarding the decrease in the number of conflicts (r = −0.093, k = 4, N = 379, p < 0.05).

Although these studies focused not only on the impact of the processes experienced but also on the training received by the participants, further research is required to provide data from different countries, from schools with varied characteristics, and from different school age groups.

Research objective and questions

The benefits of school mediation were investigated to measure its effectiveness through its participants: mediators and mediated parties. Therefore, studies that only evaluated the effectiveness of school mediation training – without putting this training into practice – or that analyzed participants in conflict simulations were not included in this analysis.

The following research questions were raised:

In what years were they published?

What is their geographical distribution?

What is their type of research?

What are the most cited studies?

What is the population: teacher mediators, student mediators, or mediated students?

In what educational stages were they conducted?

What is the design of the mediation intervention and the statistical design of the research studies?

What measurement instruments were used?

What emotional, socio-cognitive, and moral variables are the results related to?

What social impact variables are the results related to?

Method

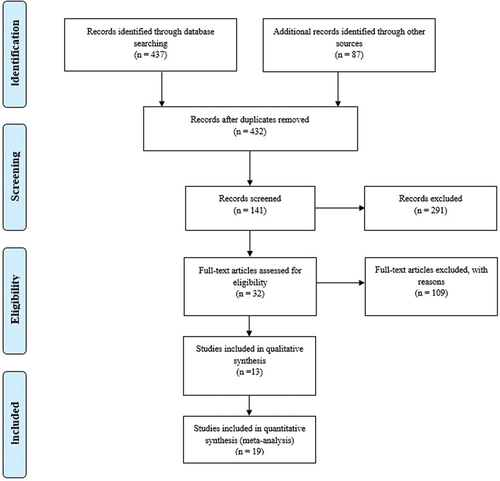

The systematic review was conducted from January to June 2020, and the studies were selected using the PRISMA method (Liberati et al., Citation2009; Moher et al., Citation2009), as described below.

Keyword selection and search filters

The search was performed using the following combinations of terms, in Spanish and in English:

((((mediación OR ‘mediación entre iguales’ OR ‘mediación escolar’) AND (conflicto OR ‘resolución de conflictos’)) AND (‘centro educativo’ OR ‘escuela’ OR ‘escuela’) AND evaluación)

((((mediation OR ‘peer mediation’ OR ‘school mediation’) AND (conflict OR ‘conflict resolution’)) AND school) AND evaluation)

Whenever allowed by the database, the terms included in the Boolean search were restricted to keywords, ‘index terms,’ or ‘subjects.’ Otherwise, the search was restricted to terms in the abstract. If none of these options was available, the search was restricted to titles containing the term ‘school mediation.’ The multidisciplinary thematic profile was also selected to include both education and psychology and not exclude interdisciplinary categories encompassing studies of interest for this review while avoiding searching for related words or equivalent subjects. The search was also limited to available results (print + online). Lastly, the time interval included studies published in the last 20 years, that is, from 2000 to 2020.

Search for information in the database

The literature search was performed combining formal and informal procedures to mitigate the possible harmful effects of publication bias.

As formal sources, the following electronic bibliographic databases were searched: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), EBSCO (PsyINFO), Redined, Eric, and PubPsych. A search was also conducted using UNIKA, a University of Navarra (Universidad de Navarra – UNAV) tool for jointly searching the main sources of information. In addition to using the aforementioned filters, other results were explored at UNIKA to ensure that no key study was overlooked.

As informal or grey literature sources, the following databases were used: OpenGrey and WorldCat, Dissertation Abstract Online, TESEO, and Dart-Europe E-Theses Portal.

Search and screening tools

The cadima.info platform was used to upload the records to a database and to eliminate duplicates, subsequently reading the title and the abstract of each manuscript. Studies were excluded after screening for the following main reasons: 1) the term ‘mediation’ was not mentioned even though the topic of the article was related to school coexistence or conflict resolution; 2) the term ‘mediation’ was mentioned, albeit linked to other areas or purposes (for example, criminal mediation, pedagogical mediation, parental mediation, or mediation applied from a social education perspective); and 3) the document was available in DVD format or was not an academic publication.

Eligibility criteria and exclusion labels

Studies were accepted or not according to the following eligibility criteria:

a) Characteristics of the school mediation process (degree of formalization and type of interpersonal conflict):

- Real school mediation processes were formally conducted (at least one) following its formal phases, namely: (i) opening statement, (ii) viewpoint and issues of all parties, (iii) discussions, (iv) search for and evaluation of solutions, and (v) agreement and closing. Studies in which these phases were not met or informal mediations were excluded.

− The type of mediated conflict was interpersonal. Studies in which the conflict was violent or related to bullying were excluded because mediation is not recommended when there is an imbalance of power between the parties.

The exclusion label for this criterion was ‘wrong concept.’

b) Characteristics of the sample of participants:

- The mediators were schoolteachers or students, without involving external people. The mediation was led by a teacher or student or co-mediated (by two teachers or two students). Group mediation (in a group or groups of people) was excluded because this approach requires a more complex organization.

- The mediated parties were students. Studies of mediations of teacher-parent, teacher-teacher, teacher-non-teaching staff, and teacher-principal conflicts were excluded from this review.

- The student body, student mediator, and mediated students comprised primary or high school students.

- Teacher mediators were of any age and professional experience, training, area of knowledge, and educational stage.

The exclusion label for this criterion was ‘wrong population.’

c) Methodological characteristics:

- Experimental, quasi-experimental, and qualitative studies were included in this review. These studies should provide data that could be used as clues or evidence to answer the research question raised in this study. Theoretical or descriptive studies were excluded.

- Access to the sample, data collection, and their statistical treatment should follow previously established procedures.

- The results were measured using an evaluation instrument, such as questionnaire or scale, interview, discussion group, observation record, or self-assessment report, ensuring its reliability and validity in its preparation (if applicable) and application, regardless of instrument. Therefore, those studies whose data were based on context documents, such as reports on the functioning of mediation in the center, were not included.

- Doctoral theses were accepted, but bachelor and master’s theses were excluded.

The exclusion label for this criterion was ‘wrong methodology.’

d) Type of results:

- The data were specifically related to school mediation benefits, both personal and environmental. Studies whose results focused on other aspects, for example, the evaluation of the operation or mediation service (type of conflicts mediated, number of agreements reached, and profile of the mediator, among others) were excluded from this review.

The exclusion label for this criterion was ‘wrong outcome.’

e) Language:

− The study should be written in Spanish or English.

The exclusion label for this criterion was ‘foreign language.’

Data extraction and inclusion

After selecting the studies, the data were extracted. All selected articles were read in full by the researcher who extracted the key information. An Excel spreadsheet was used to record the data and to encode the characteristics of each study. As in Meca (Citation2010), extrinsic (study details), substantive (type of intervention or participants), and methodological characteristics were distinguished. Thus, the coding had the following sections:

Study details: authors, title, journal, year of publication, country, type of document.

Decision on the inclusion or exclusion of the study according to preset criteria.

Data extraction:

Statistical design: type of study (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed).

Type of mediation intervention.

Participants: number of participants (N), type (teacher mediators, student mediators, mediated students), educational level, and age.

Instrument used in the study.

Results were classified along the four dimensions of the Revised Educational Model for the Development of Competences through Mediation (Modelo Educativo de Desarrollo de Competencias a través de la Mediación-Revisado – MEDECOME-R) (Autor&coauthors, 2020): interpersonal emotional competence, personal emotional competence, cognitive-moral competence, and social impact.

Results

Flowchart

The studies were identified and selected as shown in the following flowchart and in accordance with PRISMA guidelines ().

Of the 524 studies initially identified, 92 duplicates were detected, and 291 records were excluded. Thus, 141 studies were screened, of which 109 were excluded. outlines the main reasons. Ultimately, 32 studies were included in this review.

Table 1. Distribution of excluded studies.

Characteristics of the included studies

The studies are distributed throughout the 2000–2020 interval. The year with the highest number of publications was 2000 (5). Subsequently, each year, between 1 and 3 studies were successively published, except for 2001 (0), 2004 (0), 2008 (0), and 2020 (0).

As for their geographical distribution, the studies were conducted in five countries: Spain (14), USA (13), Turkey (3), Portugal (1), and New Zealand (1).

Among all studies, 22 are articles, 9 are doctoral theses, and 1 is a technical report in book format. Taking as reference the number of citations of each study in Google Scholar, the most cited study is that conducted by Bell et al. (Citation2000) with 118 references, followed by the studies by Harris (Citation2005) and Casella (Citation2000) with 65 references each.

Several aspects should be highlighted regarding the type of sample. First, the studies typically collected data from several types of participants simultaneously: teacher mediator (TM), student mediator (SM), and/or mediated student (MS). Few studies focused on only one type of participant. Most studies provided data on student mediators (28), but less frequently on teacher mediators (7) or mediated students (11).

The educational level at which the mediation processes were developed according to the age of the participating students were mainly Compulsory Secondary Education (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria – ESO) (13) or ESO-Spanish Baccalaureate (10), and in turn, only 2 studies were exclusively focused on primary education, 4 on primary education-ESO, and 2 exclusively on Spanish Baccalaureate. One study is not included at any educational level because the participants were only teacher mediators.

The following tables outline all studies included in this review according to their methodological approach: quantitative (12) (), mixed (7) (), and qualitative (13) (). The main characteristics of all studies were collected: year of publication, authors, title of the article, country, type of publication, type of sample, and size (TM, teacher mediator; SM, student mediator; MS, mediated student).

Table 2. Characteristics of the included quantitative studies.

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies of mixed type.

Table 4. Characteristics of included studies of qualitative type.

Description of the studies according to their statistical design

In the quantitative and mixed studies, three groups were differentiated according to their statistical design: pre-post studies, pre-post studies with a control group, and post studies. Subsequently, the following characteristics were explored in each of these three groups and in qualitative studies: the type of mediation intervention conducted, the instruments used, and the mediation benefits. In addition, the mediation benefits reported in the studies are summarized along the following MEDECOME-R dimensions (Iriarte et al., Citation2020): interpersonal emotional competence, personal emotional competence, cognitive-moral competence, and social impact.

Pre-post studies

This group included studies that applied the instrument before and after the mediation intervention. The intervention was very similar among all studies and consisted of selecting student mediators in one or several schools and specifically training them in mediation. After this training, the student mediators intervened in real cases of conflict between students.

The student mediators were normally selected from a pool of students who either applied or were nominated by their peers or by school staff, albeit always voluntarily. Some selection criteria were related to personal and/or academic qualities or characteristics.

The training hours and their distribution over time varied among the studies. In most studies, training lasted from 10 to 15 hours, spread over two sessions (either consecutively over two weeks, or one per semester). However, in the study by Harris (Citation2005), the student mediators were trained for 160 hours.

The mediation intervention was normally conducted throughout the school year, although in two studies the pre-post analysis was conducted in schools where a mediation program had been active for 2 years (Durbin, Citation2002) and in another for 10 years (Harris, Citation2005). All these studies were conducted in the USA. Their instruments and findings are outlined in .

Table 5. Results of studies with pre-post measurement.

In the interpersonal emotional dimension, the following perceived learnings stand out: the tendency to get along better with others, greater understanding of the other’s point of view, and improved communication through simple skills such as speaking calmly, clarifying information, and listening actively.

In the personal emotional dimension, differences in self-esteem were identified, albeit non-significant ones.

In the cognitive-moral dimension, knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward conflict improved. More specifically, conflict was perceived as something normal in life, the preference for dialogue when addressing problems increased, and the necessary steps of the mediation process were learned. Mediation helped to understand the causes of a conflict and gave the opportunity to both parties to be heard and to clarify misunderstandings in a safe and confidential environment.

In terms of social impact, the number of reports of indiscipline or expulsions for disruptive behaviors, disobedience, physical or verbal conflicts, and, to a lesser extent, challenging behaviors decreased, whereas the perception of security and belonging increased, thus defining psychologically healthier environments that prevent violence.

Pre-post studies with a control group

This group included studies that, in addition to conducting pre-post measurements, had a control group (CG) and an experimental group (EG) to identify differences between them by observing their evolution throughout the study period. In these studies, the EG is paired with a CG whose participants have not undergone mediation or received training for such purposes, while ensuring similarity in variables such as gender, age, ethnic origin, or grade point average. Generally, both groups are formed in the same school. The CG and EG were located in different schools only in the study by Ramírez (Citation2009). In three studies, the groups were formed with student mediators and in one with mediated students.

A mediation intervention involves selecting and training mediators, ensuring the participation of all parties in mediations, and taking measures in the same school year. In Benton (Citation2012), in addition to a pre measure, two post measures were taken, one at the end of the mediation training and another after the actual experience of the mediators.

As outlined in , a striking fact is that all pre-post studies with a control group were dissertations.

Table 6. Results of studies with pre-post measurement and control group.

There are no results for the interpersonal or personal emotional dimension. Benton (Citation2012) reported a post-test (after training) increase in the average emotional intelligence scores of the student mediators, albeit one not maintained after the mediation experience. No significant increases were found after the mediation intervention.

In the cognitive-moral dimension, the study by I. Silva (Citation2015) identified that, before starting the mediation program, the student mediators had greater social and conflict-resolution skills than the students who were not. Despite this difference, the frequency of all social skills among mediator students increased slightly in the evaluation conducted at the end of the course. Similarly, strategies for coping with conflicts were more frequently used by the experimental group, formed by the set of student mediators, than by the control group. Furthermore, the following strategies showed significant differences between the two groups: seeking social support, focusing on solving the problem, seeking professional help, and seeking relaxing diversions. In turn, Ridley (Citation2007) noted that mediated students had lower rates of aggressive responses than control subjects in the posttest after the intervention, but this difference was not significant.

In the social impact dimension, no quantitatively significant changes were found in reducing conflicts and improving coexistence. However, in Ramírez (Citation2009), the students who participated in the school mediation project assessed school relationships and environment more positively. The comparison of pre-test opinions of both groups (CG and EG) with those provided by the experimental group in the post-test showed a distribution of scores toward positive or very positive assessments of the school environment in the latter. Similarly, Benton (Citation2012) found several percentage increases in EG responses in the use of mediation skills with family and friends both after training and after the mediation experience.

Post studies

Post studies are studies that take a single measure after the intervention to gather evidence of mediation benefits. In all of them, an intentional non-probabilistic sampling is performed to select schools with an active mediation service for at least one year. Subsequently, the sample is defined by accessibility, establishing the number of mediators and mediated participants of school. This type of study has been conducted in Spain, more specifically in 3 autonomous communities: Navarra, Valencia, and Malaga. In all three studies, the collaboration of entities related to school coexistence was key to accessing a representative sample. For example, the Coexistence Advisory Board (Asesoría de Convivencia – AConv), in Navarra; the Center for Training, Innovation and Resources for Teachers (Centro de Formación, Innovación y Recursos Educativos – CEFIRE), in Valencia; the Alicante City Council, and the Education and Youth Department of the Malaga City Council.

In this group, all studies either applied the instrument designed by Ibarrola-García (Citation2010) and published in Ibarrola-García & Iriarte, (Citation2012) or adapted it to develop a new ad hoc instrument. The high average scores that each type of participant gave to different items, which indicate differences in perceived learning, were extracted to describe the results. outlines the results from post studies.

Table 7. Results of studies with post measurement.

In the interpersonal emotional dimension, empathy, the expression of emotions and feelings, active listening, and communication with others stood out.

In the personal emotional dimension, emotional awareness and emotional regulation stood out.

In the cognitive-moral dimension, objectivity emerged as a relevant factor in the analysis of conflicts and alternative thinking in the search for different solutions to a conflict. Consequential thinking, knowing how to ask for help, responsible coexistence, respect and acceptance of differences, reliability, and a sense of justice were also highlighted.

Lastly, in terms of social impact, mediation and the mediators’ work were positively assessed. In general, the students considered that mediation helps to create good coexistence by preventing conflicts and their escalation and by generating support spaces for students. Moreover, mediation learning is transferred to other life situations inside and outside schools. For the teachers, mediation improves relationships with students and helps to manage conflicts and to guide undesirable behaviors.

Qualitative studies

The qualitative studies included in this review (see ) addressed the context of school mediation. Primarily through interviews and direct observation, they explored in greater depth aspects that could go unnoticed. When extracting the results for this study, the researchers’ general descriptions were taken as reference. These descriptions included explanations of the data or emerging categories derived from the analysis of the content of the participants’ responses about their experiences, feelings, and knowledge in mediation. Therefore, data retrieved only through direct citations of the interviews reported in the studies were not highlighted in this review.

In the interpersonal emotional dimension, cognitive and affective empathy stood out, as well as the expression of feelings. As indicated by Casella (Citation2000), learning to be a better listener can calm or ‘defuse’ hostile situations and ‘take the sting out of words.’

In the personal emotional dimension, mediation especially helped subjects to learn how to control emotions such as anger (Robinson et al., Citation2000).

In the cognitive-moral dimension, learning strategies and the ability to understand and resolve conflicts, being open to possible changes in the perception and perspective of situations, and being proactive in creating beneficial situations for both parties in a disagreement stood out. Simultaneously, prosocial behavior also stood out in the student mediators’ selfless effort to create peace, unity, and harmony, thereby arousing positive emotions of happiness in them (Moral Mora, Citation2010; Türnüklü, Citation2011).

As for the social impact, the contribution of mediation to coexistence was referenced, especially in resolving simple conflicts without great complexity (Nix & Hale, Citation2007). Experience and training were perceived as beneficial only because they create an opportunity for tackling conflicts and avoiding addressing them in a destructive way. The mediators also mentioned the use of mediation skills in their own lives.

Discussion and conclusions

This study highlights research on school mediation benefits and on how this process helps its participants. This historical overview and state-of-the-art analysis may help to better guide future studies of this subject.

The 524 studies initially identified attest to the research interest in this subject despite the fact that mediation is not yet widespread as an educational practice across all schools. For this reason, participant samples in general, and the group of mediated students in particular, are difficult to access given the usual lack of a registry or census, which would facilitate monitoring schools with mediation.

Only 32 of the studies included in this review met the eligibility criteria. Among the reasons for excluding studies, the most prominent was a lack of methodological rigor. Therefore, researchers struggle to record changes in students or in the school environment resulting from mediation processes. The external factors that can affect the results are difficult to control and the observations are also expensive and limited.

In line with the above, the studies included in this review were highly similar in terms of type of school mediation intervention, but some differences were identified in statistical design. For this reason, the studies were distributed into four groups. This analysis allowed us to better understand how the research has been conducted to date and thus better understand the results:

- Post studies collected larger and more accessible samples in a region. They were performed using non-longitudinal designs describing a population at a given time and were thus intended to identify the current state of the matter. Consequently, the collaboration of the administrations was crucial for facilitating access to the sample. In this group, the studies reported the most evidence in all dimensions of the Medecome-R model, but they also had the most limitations. The results were based on the participants’ self-perception and not assessed using a measure that could be taken as a reference for comparing its results with the findings of other studies or for knowing its evolution over time.

-In turn, pre-post studies, with or without a control group, reduce the risk of bias. Any circumstance or the maturation process itself should occur both in the experimental group and in the control group. The internal validity of the mediation intervention is increased, and the statistical data were sufficient to make the results interpretable. However, the samples were small and generally in the same school. Therefore, many students knew each other, so some diffusion might have occurred because they likely talked among themselves about the study in which they were participating.

The results from these two groups (pre-post and pre-post with control group) highlight the lack of evidence in the emotional dimension. Only some of the pre-post studies indicate signs of interpersonal-emotional improvement in empathy and emotional expression. The effects of other studies on the cognitive-moral and social impact dimensions were not reproduced either, but some did show significant increases, specifically: in the knowledge of strategies for coping with conflicts, in the willingness to listen and to dialogue and in the positive assessment of the school environment.

In light of these results, we are unable to conclude that mediation can change the basic belief system (for example, about aggression) or socio-emotional competence or even constructs such as emotional intelligence. Such changes require more time than an intervention such as peer mediation takes. Nevertheless, mediation does increase the likelihood of acting constructively and positively when facing conflicts. Accordingly, mediation provides the experience and environmental feedback necessary to significantly change a person over time.

A contextualized mediation intervention should have greater positive environmental feedback and therefore a stronger impact when integrated with other programs in the Coexistence Plan through a global approach, implying a real participation structure (Sánchez García-Arista, Citation2016). The actions to improve the coexistence are more effective when they are integrated into school plans. The School Coexistence Plan is a document in which teachers reflect on the needs, problems, approach and practices to educate for coexistence in their school. The objective is then to improve coexistence and not only to respond to problems.

In addition to the degree of institutionalization, the following aspects can also affect the results: the selection of student mediators and the length or distribution of the hours of training. Future studies of the effectiveness of school mediation should analyze these aspects and the quality of the school environment. Bidirectionally, a positive school environment, which starts from the educational model of school coexistence, can foster the proper functioning of mediation while simultaneously contributing to generating social bonds and more positive school environments (Cremin, Citation2007; Noaks & Noaks, Citation2009).

Limitations

The strengths of this systematic review are the amplitude of the publication date, the number of electronic databases searched, the unpublished literature, and the researcher’s knowledge and previous experience in the subject.

Notwithstanding its strengths, this review has some limitations, particularly the low comparability of the studies. The characteristics of the studies may moderate or affect the results, such as differences between samples in the type of participants, in mediation training and its effects, in the adequacy of the instrument used, and in the degree of institutionalization of mediation in the school.

In fact, a meta-analysis could not be performed because the studies lack the necessary data to calculate an effect size. In some studies, the results were expressed as percentages and by categorical answers, thus preventing us from assessing the quality of all relevant studies that answer the research question.

The method used in this review – systematic review – also requires understanding the implications of losses in rigor, bias, and limited results due to the selected exclusion criteria, such as language limitations and possible restrictions in literature search and retrieval stages or in the inclusion of literature that was difficult to access in this study. Another limitation was the unavoidable need to simplify some of the methodological steps because this systematic review was conducted by a single reviewer, which might have decreased its precision and reliability and limited the depth of analysis of the collected evidence.

Implications for future research

The existence of censuses of schools that conduct mediations would facilitate access to larger and more representative samples. Asking the schools to prepare records would provide access to information on how mediation is used.

No major differences in school mediation interventions or in the type of instrument were found among the studies included in this review. However, their empirical design differed, as shown by the lower results of the studies with more demanding statistical designs. The type of instrument and the necessary degree of statistical complexity must be adjusted. In this regard, researchers should not lose sight of the possibility of complementing empirically validated effectiveness with the analysis of recorded interventions.

Research must first assess the real impact of mediation interventions and second, provide recommendations to improve the quality and efficiency of the current challenge of conflict-resolution prevention and education.

Guiding conflict resolution promotes the proper development of students’ sociability and socialization and ensures the exercise of democratic principles in society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bell, S. K., Coleman, J. K., Anderson, A., Whelen, J. P., & Wilder, C. (2000). The effectiveness of peer mediation in a low-ses rural elementary school. Psychology in the Schools, 37(6), 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-680720001137:6<505:AID-PITS3>3.0.CO;2-5

- Benton, B. L. (2012). Effects of a peer training and mediation program on student mediators’ emotional intelligence and generalization of conflict resolution skills [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Georgia.

- Bisquerra, R. (1992). Orientación psicopedagógica para la prevención y el desarrollo. Boixareu Universitaria.

- Burrell, N., Zirbel, C. S., & Allen, M. (2003). Evaluating peer mediation outcomes in educational settings: A meta-analytic review. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 21(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.46

- Carrasco, V., Hernández, M. J., & Ripoll, J. (2012). Fortalezas y debilidades de la implantación de un programa de mediación en educación secundaria = strengths and weaknesses of the implementation of a mediation strategy in secondary school. REOP - Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 23(3), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.23.num.3.2012.11466

- Casella, R. (2000). The benefits of peer mediation in the context of urban conflict and program status. Urban Education, 35(3), 324–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085900353004

- Cassinerio, C., & Lane‐Garon, P. S. (2006). Changing school climate one mediator at a time: Year‐one analysis of a school‐based mediation program. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 23(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.149

- Cook, J. Y., & Boes, S. R. (2013). Mediation works: An action research study evaluating the peer mediation program from the eyes of mediators and faculty (consulted on 21-04-26). https://bit.ly/3cbYnJk

- Coopersmith, S. (1989). SEl: Self-Esteem Inventories. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Cowie, H., & Wallace, P. (2000). Peer support in action: From bystanding to standing by. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/978144621912

- Cremin, H. (2007). Peer mediation. Open University Press.

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring Individual Differences in Empathy: Evidence for a Multidimensional Approach. Journal of personality & social psychology, 44, 113–126.

- DeVoogd, K., Lane‐Garon, P., & Kralowec, C. A. (2016). Direct instruction and guided practice matter in conflict resolution and social‐emotional learning. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 33(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.21156

- Díaz-Aguado, M. J., Martínez-Fernández, M. B., Chacón, J. C., & Martín-Barbarro, J. (2021). Student misbehaviour and school climate: A multilevel study. Psicología Educativa, 27(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a10

- Díaz-Negrín, M., Luján, I., Rodríguez-Mateo, H. J., & Rodríguez, J. C. (2015). Análisis de la gestión e implementación en mediación en el ámbito escolar. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2015.n1.v1.108

- Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683.

- Durbin, S. B. (2002). School-based peer mediation program implementation: An exploration of student mediators’ attitudes and perceptions before and during program participation. Texas A&M University.

- Frydenberg, E., & Lewis, R. (1996). Escalas de Afrontamiento para Adolescentes. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

- García-Raga, L., Bonet, R., & Mondragón, J. (2018). Significado y sentido de la mediación escolar desde la perspectiva del alumnado mediador de secundaria/Meaning and sense of school mediation based on high school mediators’ views. REOP-Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 29(3), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.29.num.3.2018.23322

- García-Raga, L., Chiva, I., Moral, A., & Ramos, G. (2016). Fortalezas y debilidades de la mediación escolar desde la perspectiva del alumnado de educación secundaria. Pedagogía Social Revista Interuniversitaria, 28(28), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2016.28.15

- García-Raga, L., & Grau, R. 2016. Diseño y validación de un instrumento para evaluar el impacto de la mediación escolar. In C. Pérez-Fuentes, J. J. Gázquez, M. Molero, A. Martos, and A. B. Barragán, La convivencia escolar. Un acercamiento multidisciplinar (Vol. 2, pp. 93–100). Almería: ASUNIVEP.

- García-Raga, L., Grau, R., & Boqué, M. C. (2019). School mediation under the spotlight: What Spanish secondary students think of mediation? Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies, 19(19), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2019-019-garc

- Garrard, W. M., & Lipsey, M. W. (2007). Conflict resolution education and antisocial behavior in US schools: A meta-analysis. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 25(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.188

- Gismero, E. (2000). Escala de habilidades sociales. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

- Harris, R. D. (2005). Unlocking the learning potential in peer mediation: An evaluation of peer mediator modeling and disputant learning. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 23(2), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.130

- Huesmann, L. R., & Guerra, N. G. (1997). Childrens normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. Journal of personality & social psychology, 72, 408–419.

- Ibarrola-García, S. (2010). Mediaci’ón escolar y convivencia: estudio sobre el impacto de la mediación en profesores mediadores, alumnos mediadores y alumnos mediados. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Navarra.

- Ibarrola-García, S., & Iriarte, C. (2012). La convivencia escolar en positivo: mediación y resoluci’ón de conflictos. Madrid: Pirámide.

- Ibarrola-García, S., Iriarte, C., & Aznárez-Sanado, M. (2017). Self-awareness emotional learning during mediation procedures in the school context. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 15(41), 75–105.

- Iriarte, C., Ibarrola-García, S., & Aznárez-Sanado, M. (2020). Propuesta de un instrumento de evaluación de la mediación escolar (CEM). Revista Española de Pedagogía, 78(276), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP78-2-2020-08

- Jares, J. (2006). Pedagogía de la convivencia. Graó.

- Jenkins, J., & Smith, M. (1995). School mediation evaluation materials. Albuquerque, NM: National Resource Center for Youth Mediation.

- Johnson, W. D., & Johnson, T. R. (2002). Teaching students to be peacemakers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Education, 12(1), 25–39.

- Jones, T. S. (1995). Comprehensive Peer Mediation Evaluation Project. Philadelphia: Temple University.

- Jones, T. S., & Kmitta, D. (1992). School Conflict Management: Evaluating Your Conflict Resolution Education Program—A Guide for Educators. Columbus: Ohio Commission on Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management.

- Jones, T. S., & Kmitta, D. (2000). Does it work? The case for conflict education in our nation´s schools. Conflict Resolution Education Network.

- Kacmaz, T. (2011). Perspectives of primary school peer mediators on their mediation practices. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 43, 125–141.

- Kapusuzoglu, S. (2010). An investigation of conflict resolution in educational organizations. African Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 96–102.

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Meca, J. S. (2010). Cómo realizar una revisión sistemática y un meta-análisis. Aula Abierta, 38(2), 53–64.

- Miller, F. W. (1971). Principios y servicios de orientación escolar. Magisterio Español.

- Mitchell, B. J. D. (2000). An evaluation of one public high school’s peer mediation intervention: Teachers’ perceptions [ Doctoral dissertation]. Fielding Graduate University.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Attman, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moral Mora, A. M. (2010). Una aproximación metodológica a la evaluación de programas de mediación para la mejora de la convivencia en los centros escolares [Tesis doctoral inédita]. Universidad de Valencia.

- Murrow, K., Kalafatelis, E., Fryer, M., Ryan, N., Dowden, A., Hammond, K., & Edwards, H. (2004). An evaluation of three programmes in the innovations funding pool: Cool schools. Ministry of Education.

- Nix, C. L., & Hale, C. (2007). Conflict within the structure of peer mediation: An examination of controlled confrontations in an at‐risk school. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24(3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.177

- Noaks, J., & Noaks, L. (2009). School‐based peer mediation as a strategy for social inclusion. Pastoral Care in Education, 27(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940902731880

- Ortega, R., & Del Rey, R. (2004). Construir la convivencia. Edebé.

- Ortega, R., & Mora-Merchán, J. (2005). Conflictividad y violencia en la escuela: iniciativas y programas de afrontamiento de la conflictividad y la violencia escolar. Díada.

- Pérez-Albarracín, A., & Fernández-Baena, J. (2019). Más allá de la resolución de conflictos: Promoción de aprendizajes socioemocionales en el alumnado mediador. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 17(48), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v17i48.2223

- Pinto da Costa, E. (2017). Evaluation of violations in water quality standards in the monitoring network of São Francisco river basin, the third largest in Brazil. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 189(11), 17 de mayo de 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6266-y

- Ramírez, A. (2009). Diagnóstico y gestión de conflictos escolares mediante la intervención en un proyecto de mediación escolar en el aula del colegio de aplicación de Jaén-Perú [ Tesis doctoral].

- Ridley, C. (2007). Evaluation of a school-based peer mediation program: Assessing disputant outcomes as evidence of success [ Doctoral dissertation]. Auburn University.

- Robinson, T. R., Smith, S. W., & Daunic, A. P. (2000). Middle school students’ views on the social validity of peer mediation. Middle School Journal, 31(5), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2000.11494648

- Sánchez García-Arista, M. L. (2016). Gestión positiva de conflictos y mediación en contextos educativos. Reus.

- Schellenberg, R. C. (2005). School violence: Evaluation of an elementary school peer mediation program. [Tesis doctoral inédita]. Regent University.

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., & Bhullar, N. (2009). The assessing emotions scale. In C. Stough, D. Saklofske, & J. Parker (Eds.), The Assessment of Emotional Intelligence. New York: Springer.

- Silva, I. (2015). La mediación como herramienta para resolver conflictos. Impacto sobre las habilidades sociales de los alumnos mediadores en un centro de educación secundaria [ Doctoral dissertation]. Universidad de Alcalá.

- Silva, I. S., & Torrego, J. C. (2017). Percepción del alumnado y profesorado sobre un programa de mediación entre iguales. Qualitative Research in Education, 6(2), 214–238. https://doi.org/10.17583/qre.2017.2713

- Smith, S. W., Miller, M. D., & Daunic, A. P. (1999). Student peer mediator generalization questionnaire (Technical report #7). Retrieved from University of Florida, Department of Special Education website: http://www.coe.ufl.edu/CRPM/CRPMhome.html

- Sullivan, P. K. (2000). The antibullying handbook. Oxford University Press.

- Taylı, A. (2006). Increasing personal and social responsibility in high school students through peer assisting practice. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Gazi University, Ankara.

- Torrego, J. C. (Coord.). (2003). Resolución de conflictos desde la acción tutorial. Consejería de Educación.

- Torrego, J. C. (Coord.). (2006). Modelo integrado de mejora de la convivencia. Graó.

- Turk, F. (2018). Evaluation of the effects of conflict resolution, peace education and peer mediation: A meta-analysis study. International Education Studies, 11(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n1p25

- Türnüklü, A. (2011). Peer mediators’ perceptions of the mediation process. Eğitim ve Bilim, 36(159), 179–191.

- Vázquez, R. L. (2012). La mediación escolar como herramienta de educación para la paz. Tesis doctoral inédita. Universidad de Murcia.

- Wilson, S. J., Lipsey, M. W., & Derzon, J. H. (2003). The effects of school-based intervention programs on aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.136