ABSTRACT

The voice of young people in schools is often tokenistic. They are asked to contribute to surveys for OFSTED or are part of an adult-led school council. Rarely are they asked to work with adults to create new knowledge for school improvement. Returning to my previous school to conduct research resulted in developing an inclusive and collaborative methodology. Whilst initially intending to use a participative action research (PAR) process, I synthesised this with Critical Communicative Methodology (CCM) to create Youth Participative Dialogic Action Research (YPDAR). This approach created a research power dynamic where responsibility was shared more equally between the young people and the researcher. The results of this approach were unexpected. As the process developed, the young people’s confidence grew, their trust in the school developed, and they felt empowered to act. This paper explores the processes involved and how YPDAR could be used as a school improvement model with the potential not only to transform young people’s lives, but also the culture of the school.

1. Introduction, context and theoretical background

As a teacher with over 35 years of experience, I was acutely aware of the mental health crisis young people were facing and developed and introduced a whole-school mental health strategy. An opportunity arose for me to investigate the strategy’s efficacy through a Ph.D. While the research produced insightful findings related to the strategy, this paper focuses on the methodology developed through the research process.

My aim from the beginning of the research was to ensure it was a participatory project. I knew there were differing levels of young people’s participation (Cook-Sather, Citation2020; Mercer, Citation2002) in educational research. This was something that also gave me the opportunity to explore how my teaching career may impact my work as a researcher and one of the reasons I was drawn towards participatory action research (PAR); I wanted to support young people to contribute to the review of this school strategy. The partnerships I developed with them during this research led me to the conclusion that, with guidance, they could become change agents in schools.

Being aware that young people are often used as objects of research within a school setting (Wöhrer & Höcher, Citation2012), I intended to ensure that this research was conducted from the young person’s perspective, which is gaining credence although still not commonly adopted (Brady, Citation2017). Accordingly, prior to initiating the data collection phase for my thesis, I visited the school and conducted a patient and public initiative (PPI) type exercise. The purpose of the PPI meetings was to gather young people’s thoughts so they could help shape the research. One of their recommendations I adopted was for the data collection to be completed by sixth-formers, whom they believed the younger participants would talk to more readily. In this respect, I agree with Moules and Kirwan (Citation2005) when they say young people are more likely to open up to their peers than they are to adults. I intended to get a critical view of the whole school mental health strategy from a young person’s perspective. If they were more comfortable talking to someone closer to their own age, they were more likely to give insightful and authentic answers.

1.1. Pupil premium cohort as the participants

Another fundamental decision taken at this point was my invitation to young people from the pupil premium cohort to collaborate as participants in the research. Coming from the most economically disadvantaged section of society, my aim was to give volunteers an opportunity to contribute to and benefit from this unique school research. This decision was founded on the basis that research tells us poverty results in poorer outcomes both in health (Marmot et al., Citation2020) and education (Hirsch & A, Citation2007). Hirsch suggests young people in a similar demographic to the participants in my study feel a lack of control over their learning and therefore become reluctant learners. Whilst this is complex, deep-set and often linked to factors outside of school, education still plays a key role in this area. Furthermore, young people from poorer backgrounds are likelier to lack confidence in school. Mowat (Citation2015) suggests they can feel anxious, sad, frustrated, and angry about the school experience, something often compounded by discriminatory behaviour by teachers. Mowat and Hirsch both suggest that working with these young people is more effective when they are involved in the decision-making process about their own futures.

Hirsch and A (Citation2007) believes that young people’s engagement in school is linked to confidence and school relationships. In my teaching career, I observed young people from this demographic arrive in school keen and eager to impress but gradually, over time, withdraw into their shells. Their performance nose-dived, and many became either invisible or disaffected. This, therefore, allowed me to support such young people in exploring whether they could benefit from being involved in a research project such as this.

1.2. 6th formers as a young research team

After the PPI exercise, which suggested 6th formers work with me as co-researchers, the decision to ask for 6th-form volunteers to make up a young research team (YRT) was also founded on several other principles. As the oldest students in the school, they are often looked up to by other year groups and seen as being aspirational role models for the younger years. Another reason for identifying this cohort as young researchers was their age. Many of them have been at the school for either five or six years, and it is this experience of the institution (its workings, its systems, and idiosyncrasies) I wanted to tap into; the research needed to be viewed through the eyes of these experts and social actors (Cowie & Khoo, Citation2017).

Whilst the primary aim of the research was to explore the mental health strategy, I also decided upon these additional research aims:

To ensure young people in the school inform the research.

To develop ways of collaborating with young people, which ensures the researcher’s previous position does not influence findings in the school.

My focus was on ensuring the authenticity of the research through genuine youth voice. This led me to follow an action research methodology that is congruent with the socially constructivist paradigm in that it is value-laden; it has social intent and a social or ‘sound moral purpose’ (Groundwater-Smith et al., Citation2015, p. 142). My values were integral to this study’s purpose and outcome, particularly as it was subjective in exploring people’s everyday life experiences. Crotty (Citation1998) suggests we need to view the research from the participant’s point of view to minimise the risk of imposing our own assumptions. Furthermore, Crotty suggests that to protect against researcher biases, the participants needed to be involved in the research process to ensure interpretations are made from their social construction and not from that of the researcher. In the context of this research, there was the opportunity to develop an action research project that was both participative and potentially transformative by its nature. The issue of shared ownership within the research was addressed through widening participation between myself, the researcher, and the researched; as the process developed and control was devolved through the team, my role evolved from designer to facilitator (Ennew & Plateau, Citation2004). As PAR has the potential to be emancipatory and is most closely aligned with social constructivism (Langhout & Thomas, Citation2010), I decided to apply it to this school study. There was the exciting prospect of developing a research team that would include me as the researcher/facilitator, volunteer sixth formers as members of a YRT, and a cohort of young people as participants. As youth were at the centre of this research, I therefore recognised this as youth participatory action research (YPAR).

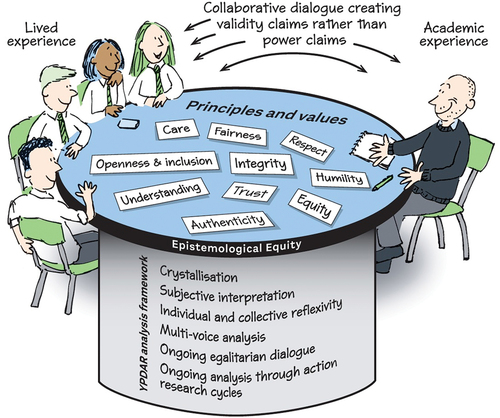

To ensure the authenticity of this research, I was intent on looking for more than ‘just’ YPAR. As with participation in general, YPAR covers a broad field that can involve young people to a greater or lesser extent. The dialogic approach of CCM further influenced my thinking (Latorre Beltran & Gómez, Citation2005). To develop my YPDAR methodology, I therefore synthesised YPAR with CCM, something I explore below. This approach was influenced by Habermas and his seven postulates, three of which are fundamental to this research. He believed everyone could interact and communicate; he called this the ‘universality of language and action’. The second postulate of relevance was the ‘absence of interpretative hierarchy’ that stated all interpretations coming from the research process are equally valid, regardless of the position of the person putting them forward. The final postulate is where the researcher and researched work on an ‘equal epistemological level’, each an expert in their area, be that academic or lived experience (Puigverta et al., Citation2012).

Habermas (Citation1987) suggests that we have moved into an age of dialogue as there has been a shift from instrumental rationality to communicative rationality, where people use their knowledge gained from lived experience, which is something that, by its very nature, is socially constructed. Such an approach aims to achieve accord rather than allowing power to be the leading force for change, something I thought to be important, bearing in mind the power dynamics at play in schools. As with the rest of society, which has seen this dialogic transformation, qualitative research has shifted away from traditional hierarchical research relationships. A redressing of power imbalances within some research areas has been achieved (Råheim et al., Citation2016). As a result, scientific knowledge about our social world has increasingly come about through egalitarian dialogue (Gómez et al., Citation2011) and has produced a more democratic, socially useful and politically responsible knowledge (Denzin et al., Citation2017) that also has the potential to be transformative (Gómez et al., Citation2011; Way et al., Citation2015). Importantly, CCM states that social interactions build social situations, and, as such, reality does not exist autonomously from the subject; only when researchers have intersubjective relationships with social actors can objectivity be reached (Gómez et al., Citation2011). The premise within CCM is that everyone can contribute to knowledge construction, which is further enhanced where there is dialogue between people with differing cultural intelligence. The relationship between the researched and the researcher is vital, and the dialogue between the two enables a path to empirical truth (Gómez et al., Citation2011). This process, therefore, gives the researchers a deep insight into the lived experience of those they are collaborating with and offers opportunities to transform people’s lives. By developing a dialogic methodology, I followed the principles of CCM, which was instrumental in fostering a transformative research process that enabled young people to be part of changing their own and others’ lives. By accessing the participants’ social constructions of reality, the YRT were then able to construct their realities in school. as they shared their lived experience with a researcher through dialogue.

As a teacher, I have seen young people adapt to challenging circumstances through self-restriction, limiting their ability to open up opportunities for them (Teschl & Comim, Citation2005). This leads to young people lacking inspiration and aspirations for enriching life experiences (Hi Kim, Citation2017). By placing young people at the centre of my research methodology, I attempted to counter this deterministic hegemony.

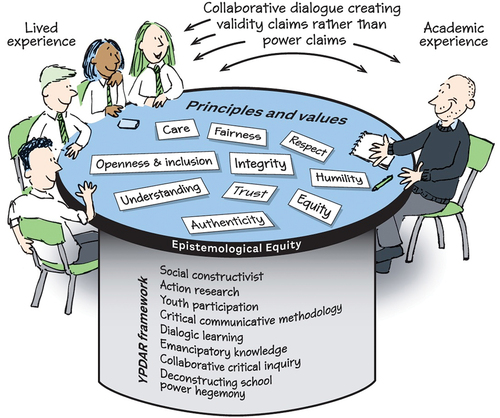

Following a CCM is about demonopolising the knowledge of experts (Beck, Citation1992) and is also attempting to ensure that the knowledge creation, whilst necessarily more complex, is more inclusive; it is likely to impact the lived reality of the social actors as they have had a dialogic collaboration with academics (Schütz & Luckmann, Citation1974). Young people have been described as ‘social actors and experts in their own lives’ (Cowie & Khoo, Citation2017, p. 234). Working in this way, with egalitarian dialogue between myself, the researcher, and these social actors, we aimed to better understand the complex nature of the inequalities that have impacted them. Social constructivism is about how human interactions enable knowledge creation, which I aimed to achieve by synthesising CCM with YPAR and developing Youth Participative Dialogic Action Research (YPDAR). I suggest as a framework for YPDAR.

2. Research design

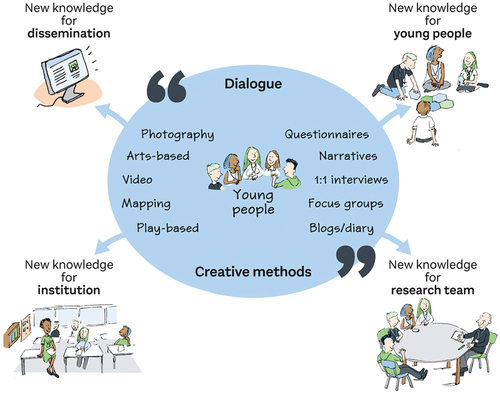

To develop a research project that is a sustained collective inquiry, the collaborative process must include its design (Eynon et al., Citation2013). I had already identified the project’s scope; however, the YRT needed input into the most appropriate methods. There was an expectation that in an attempt to collect data from a wide range of participants, multiple methods would be required. At the beginning of the research, I had thoughts about how the YRT would collect data, but it was clear that the YRT themselves should lead this area. I, therefore, developed a methodological tool () that I introduced to the YRT. The aim of the tool was twofold. It was an educative instrument as it helped me explain to them the broader purpose of the research in relation to knowledge creation. It also enabled me to introduce various potential methods the YRT could use with participants.

I was also acutely aware that the key to the data collection would be the three-way relationship between myself, the YRT and the participants. The initial focus for the YRT/participant meetings focused on getting to know the participants. On reflection, my meetings with the YRT followed a similar pattern: the more we met, the more open we became, and the better we worked together. What very quickly became apparent was that to engage the participants and develop the trust required, the YRT needed to introduce various activities with a common thread. Meetings were required to be both fun and active. The YRT started experimenting with potential data collection methods by adapting a sorting exercise I had used with them. Once they saw how successful this was in engaging the participants, they used their imagination to design their own activities, including outline figures, hexagons, photo-elicitation and poster making. These methods helped the participants find their voice as it enhanced their engagement and, ultimately, the relationships between themselves and the YRT, which is critical to this research (Broussine, Citation2008). I regularly reminded the YRT that these qualitative methods aimed to draw out a dialogue between themselves and participants in a search for rich data. Dialogue was becoming a central tenant to this research and more than a method.

3. Methods through action research

Action research assumes that those closest to a given issue are experts in understanding the root of the problem and are in the best position to help find solutions to such issues (Stringer & Ortiz Aragon, Citation2021). It addresses real-life issues that impact people’s lives through a systematic cyclical investigation that incorporates observation, reflection and action (Stringer & Ortiz Aragon, Citation2021). PAR is a collaborative approach to AR where the research team includes community members with lived experience of the research topic. The aim is the reconstruction of knowledge through understanding and empowerment. PAR is often carried out with marginalised groups who rarely have their voices heard (Bergold & Thomas, Citation2012) and is seen as a way of ensuring social change is informed by the voice of such groups. YPAR is where youth are the participants. During my extensive teaching career, I witnessed that young people rarely got the opportunity to have a say in the running of their school. Some schools run student councils, but my experience suggests they often have a staff-led agenda with little impact on young people or the institution.

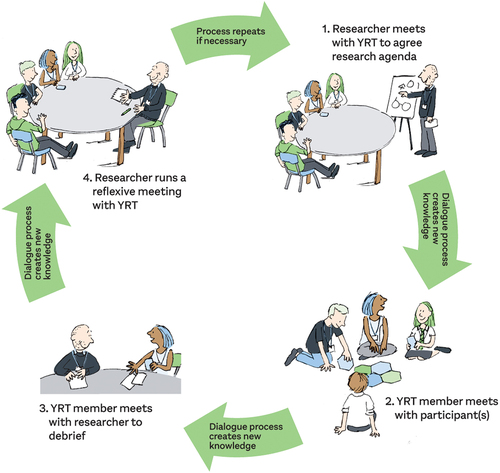

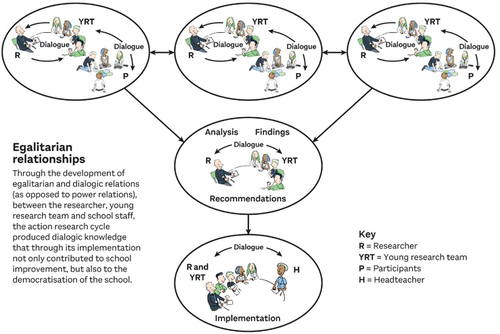

There have been a variety of action research cycles developed in recent years. Some like conceptualise the cycle as a two-dimensional iterative process of reflection, action and evaluation. Others such as Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) suggest a three-dimensional spiral process of plan, act, observe and reflect. I agree with Stringer and Ortiz Aragon (Citation2021), who highlight that the key functions within any action research cycle are linked to looking and thinking. The model they suggest includes mini-cycles of looking, thinking, and acting within a broader cyclical process of planning, implementing and evaluating. The model I developed was based on the YRT preferred way of working, which I explain below and in .

Over the data collection period, weekly mini-cycles were taking place, and these can be simplified into four stages:

Stage 1. Research Team meetings where we identified a research issue, discussed how we would investigate it and then planned the YRT/participant meetings.

Stage 2. YRT/participant meetings.

Stage 3. Researcher/YRT debrief meetings to capture and transcribe information discussed in the Stage 2. Meetings.

Stage 4. Follow up Research Team meetings to review progress, learn together and plan forward.

To fully understand the process, it is important to exemplify how stage two of the research cycle worked. I encouraged the YRT to creatively develop their own research sessions with the participants. While many of the sessions differed, they all had the same aim. This was to create a process that enabled the young researchers and the participants to develop an understanding of the given area under discussion. As the data collection commenced, I deliberately chose to give the YRT the freedom to discover the most appropriate method with which to engage the participants. All YRT members went into their initial meetings with a question-and-answer approach, which was largely unsuccessful. The participants found it difficult to engage in conversation; they gave very simplistic answers, and little meaningful data was gathered in the first few meetings. We gradually evaluated this approach, and many of the YRT team decided to employ more active, creative and fun approaches to engage the participants. To get a flavour of how this worked, I will use one such session, run by Charlotte, a YRT member, to exemplify the typicality of these sessions.

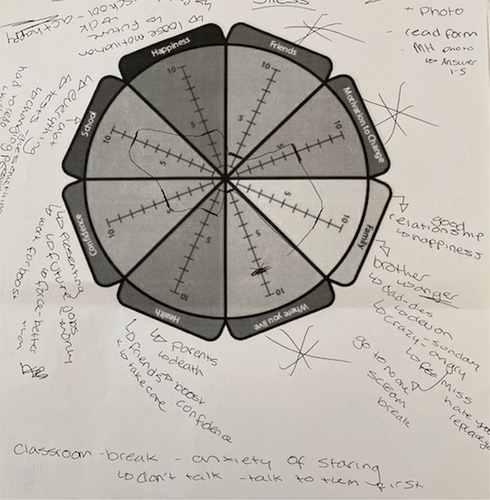

Charlotte worked with two participants, both of whom were in year seven. In one of her sessions with the participants, the topic of ‘stress’ was discussed, and Charlotte decided to explore this further. She researched this topic and found a resource she describes as a ‘stress wheel’ that divides into eight areas of life that can impact an individual’s stress levels ().

Charlotte used this simple tool in a number of ways. It gave her a simple mechanism to engage the participants and enable them to open up about their experiences in and out of school. It allowed her to record what they were saying on a third ‘wheel’, which she completed during their discussions. This activity also enabled a relationship-building process to develop week after week.

This activity took two weeks to complete; in that time, I met with Charlotte at a debriefing between the two of us, where we discussed the approach, what worked and what she needed to do next. Our debriefing meeting also gave her time to reflect on her data collection and the stress wheel exercise and plan her next steps. At the weekly team meeting, Charlotte also shared this approach with the other YRT members. This created a lively discussion where others helped evaluate the process and findings. Again, reflection on an individual and group level enhanced this process. This approach to the research helped the team as we supported and learnt from each other. The collaboration within the team also enabled creativity as other members were inspired by the ideas brought forward and demonstrated by individuals.

3.1. Analysis

One of the central themes of this research was to collaborate with the YRT to ensure the findings were authentic, having been created from our three-way dialogue. I had to ensure the analysis came from the subjective experiences of everyday school life, and this was about how young people’s world was understood rather than an objective reality of it (Boyland, Citation2019). Social constructivism enables a relational reality to be constructed by individuals working together. Biosocial interpretation develops through biological cognition evolving via social interaction as consensus is reached (Cottone, Citation2001). In this research analysis, the biosocial interpretation came from the dialogue between the three parties, people from differing backgrounds collaborating on an equal epistemological level (Gómez et al., Citation2011). This research was about enabling young people to bring their reconstructions together around the consensus (Boyland, Citation2019).

This was practitioner-based research and the research process was therefore not straightforward; the challenge came about as we aimed to conduct data collection followed by a data analysis process. As I explain below, this was an assumption on my part. Initially, I intended to apply an inductive thematic analysis approach; the YRT would meet with participants, and we would codify the data through transcripts of my debrief meetings with them. I expected to conduct a text-book thematic analysis to systematically identify, organise, and gain insight into patterns of meaning within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Whilst I used the six-phase approach to the thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) as a guide, what transpired, due to the nature of the research design and the make-up of the research team, was a hybrid dialogic version. My adaptation saw codes and themes develop through discussion, experimentation, and scrutiny of our transcripts.

The importance of the ongoing dialogue between all research parties at each step of the process cannot be underestimated, as it enabled the team to scrutinise, adjust, re-test and confirm threads in the data. While ongoing dialogue was about the data, it was also coupled with sharing and reinforcing my values. This was achieved by being fully attentive to the team by listening, discussing, and collaborating with group members as we navigated a complex and circuitous route through the research and the analysis. The weekly AR cycles became more than a data collection exercise involving an ongoing analysis process. This process is explained in detail below.

I build a step-by-step picture of how my analytical method developed in the section below. As I worked through the AR cycles and the steps below, what struck me was the overlap between methodological processes and the methods of analysis. The steps below are an indication of the sequential and iterative nature of the work. What is significant is that whilst all steps were integral to the process, Step 3 was the one where time was spent discussing, deliberating and reflecting within an intense dialogic process. This is where we came together for collaborative reflection after individual reflection from individual meetings. This was the time we made decisions and the critical step within this dialogic process.

3.1.1. Step 1. YRT/participant meetings

The YRT met with their participants every week for four months. These took on various different forms depending upon the YRT members. Some worked one-to-one, and others chose to work in pairs. On other occasions, the YRT decided that all the participants should meet, so large whole-group sessions were also held. My desire to give autonomy to the YRT meant that when challenges arose, and solutions came through a process of dialogue within the research team, my default position was to encourage the YRT to take control and make the final decision themselves. The process’ success was based on the relationships that developed between the YRT and their own participants; I learnt to trust the YRT members’ judgements as they were more than capable of making the right call on the working of the YRT/participant groups.

3.1.2. Step 2. Debrief between the researcher and individual YRT members following YRT/participant meeting

After each YRT/participant meeting, debrief meetings were held between myself and the YRT member(s) where we would explore what had taken place; this was recorded, and a transcription was made that both myself and the YRT members reflected upon and scrutinised. During the meetings, we would look at what had been successful and what had been less so. These transcripts were used for the thematic analysis process as we developed an inductive, bottom-up, data-driven approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). This is where we started to discover the codes and themes as our process of insightful invention supported us in discovering new knowledge (van Manen, Citation1990).

3.1.3. Step 3. Weekly research team meetings

The research team meetings process was built upon the foundation of collaborative dialogue based on epistemological equity. Reflective conversations drew initial observations from individual meetings and allowed us to compare and contrast the participants’ thoughts. It also facilitated in-depth group dialogue, enabling individual and group interpretations. As a research team, we discussed the findings from the previous week, and our deliberations then led us to a focus for the following week. Divorcing these discussions from the analytical process is an almost impossible task, as the research process enabled us to develop threads that the YRT would then go and explore with the participants; it was part of the research and analysis methods. The dialogue between myself and the YRT was part of communicative action as they were based upon validity rather than power claims (Flecha, Citation2009). This stage of the work was crucial if I was to develop findings based on the YRT’s voice.

3.1.4. Step 4. Supporting the YRT to contribute to the analysis

Enabling the individual members of the YRT to develop their own narrative relating to the findings was important, as this reinforced their autonomy within the research and built their confidence in the data analysis. It was a continuation of my journey to ensure that the YRT’s voice was at the core of the process. Part of this process was ensuring that whatever methods I chose were intuitive; our limited time meant we couldn’t commit to numerous hours of training. I took four significant steps to support the YRT’s involvement in the analysis.

Introducing them to an AI tool to support the data analysis. The choices I had regarding thematic analysis tools were limited. My experience with tools such as NVivo and Atlas. ti was that they were dry and could take a significant amount of time to get used to, particularly for my 6th form YRT. I, therefore, chose a tool called Quirkos because it was colourful and easy to use and interpret. In addition, the company gave free access to all the YRT, enabling them to work on the analysis in their own time.

Running tutorials on qualitative analysis that included a help sheet.

Supporting reflection through the use of a Collaborative self-reflection tool I developed.

Inspiring them to develop reflective writing.

The process I described above was about how dialogue became central to the research and how the principles of CCM enabled a collaborative process that encouraged egalitarian relationships. This, in turn, countered hegemonic school power relationships. The dialogic process between the three parties ensured robust data collection and analysis. It then enabled us to produce findings and recommendations presented to the headteacher, with whom we had further dialogue before agreeing to implement. This is summarised below in .

3.1.5. Triangulation or crystallisation?

As described above, the project’s design enabled both groups of young people to make meaningful contributions to this research through their own lived experiences and interactions with each other. It was about them developing their relationships to build an interpretative position as social constructivists (Charmaz, Citation2000) and was not about taking an objectivist standpoint (Ellingson, Citation2008). My dilemma, however, was that when I first engaged in this research, I aimed to use conventional forms of qualitative analysis so that findings could be presented to improve practice in the school (Charmaz, Citation2000). What transpired was a thematic analysis approach that was informed by the dialogic processes between the three parties within the research. My search for authenticity was less about triangulation and its objective overtones and more about the intuitive flexibility of crystallisation, which enhanced and deepened my thoroughly partial understanding of this given area. This approach brought a greater depth of understanding whilst also highlighting that there is so much more for us to discover (Richardson, Citation2000).

My decision to use crystallisation as a guiding philosophy for the analysis was reinforced by my commitment to understanding the social world through subjective interpretation within the research team (van Lieshoult & Cardiff, Citation2011). As the research developed over time, the relationships matured. Trust and understanding were built between myself and the YRT, as they did between them and the participants. This enhanced our interpretive mechanisms as we started to believe in one another’s capabilities and intentions. Through the repetitive reading and discussion of the transcripts, the collective development of new ideas became cyclical and generative as the group and research developed. By ensuring the perspectives of the research parties were interwoven, I was evaluating the quality of the work based on criteria of convergence rather than criteria of objectivity (Ricoeur, Citation1976); although this was more about being comprehensive in approach rather than about convergence as a goal (Varpio et al., Citation2017). This, I believe, is crucial for the research analysis as, by fusing multiple interpretations of reality, I am guarding against and, as far as possible, removing ‘authorial intent’ (Ricoeur, Citation1976). The clarification process through repetitive speaking and listening tests boundaries and redefines understanding, enhancing trustworthiness (van Lieshoult & Cardiff, Citation2011). It is this that can then give us a fully involved understanding of this topic (Varpio et al., Citation2017).

To develop this thinking further, I adapted the YPDAR framework () into a YPDAR analysis framework () below.

4. Discussion

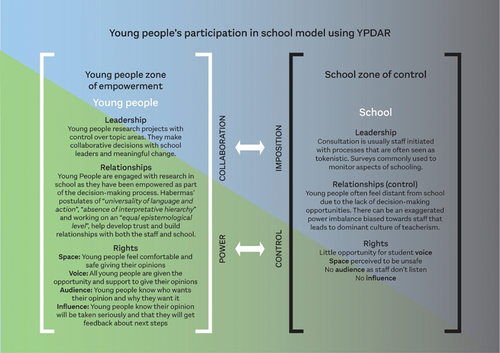

YPDAR was designed as a way to ensure young people in school had a meaningful voice in this school research project. This was about ‘knowledge democracy’ and young people’s rights. Schools are institutions which prioritise adult knowledge creation over young people’s. This research attempted to shift that balance. At the time, I did not realise that it also addressed many challenges faced by education in the 21st Century. The hierarchical nature of English schools results in power issues that see adults impact young people’s identity and social and cultural capital, which can reduce their agency. Furthermore, this research confirmed the view that schools’ expectations of young people are of being ‘compliant’ recipients of education. The system in which young people are forced to fit in ensures they have little active voice and, therefore, have little chance of real growth and development.

Power structures dominate education, but power’s negative impact on some young people is often unseen in this area. In particular, it reduces their epistemic agency and their agency to act in school. In addition to this, the participants, coming from the PP cohort, were more likely to have a poor sense of self and may have been challenged by concerns around their identity. The final piece in this complex jigsaw is how this same cohort may find school challenging as they may not have access to the social and cultural capital required to succeed.

The research process was initiated around the decision by the school to engage with students to evaluate a major school strategy. This was the first step in the trust-building process between the institution and young people; they were to be listened to, and their research findings were implemented. This message to the young people was heard loud and clear as they took on board their role as knowledge creators. Over time, both sets of young people became empowered to act, their confidence grew, and their sense of identity was positively impacted. Many schools, through their rigid behaviour policies, can negatively impact young people, and I would also suggest their epistemic agency. This project had the opposite effect as all young people benefited from epistemic development as the school called on them as critical thinkers.

In addition, the research process also produced further benefits. The YRT developed their understanding of ‘research’ and their research skills. They developed negotiating, listening and communication skills. They co-wrote academic papers and presented at conferences. Rubbing shoulders with academics and professionals from numerous disciplines helped them develop their social and cultural capital, as did their presentation of findings to the headteacher and other senior staff. They showed skill and sensitivity in using evidence-based arguments to persuade the school staff that change was required. The YRT also developed their socio-emotional skills as their research demanded they work with an ex-teacher turned researcher, school staff and younger participants.

The relationships between the YRT and participants also became key to this research. They were built on care and respect and grew into the ‘single best thing about this research’ (participants). What was discovered was that as the research progressed so trust built between the two parties. The YRT members engaged with the participants outside the research meetings and started supporting them wherever possible. There were conversations about difficult lessons and challenging relationships. One YRT member took a participant under their wing and helped enrol him in the local out-of-school ‘Young Farmers’ Club. What developed was an attachment-like relationship.

The participants also grew throughout the process. They, too, presented to senior staff in a remarkable turnaround. As the research commenced, they were all defined as ‘shy, quiet and unassuming’, and the YRT struggled to engage them in conversation. At its conclusion, many of them volunteered to present their thoughts to an audience of senior teachers and university academics. They felt the school was trusting them, and this, combined with their YRT meetings, helped empower them and grow in confidence. One of the young people involved volunteered that this work had improved their mental health. Whilst this was not part of the research and will need to be investigated further, it certainly makes sense that this overwhelmingly positive experience could impact this way.

This research has prompted me to explore the possibility of a school improvement model which includes knowledge created by young people. The headteacher and senior leaders will always lead school improvement. However, my research suggests that by developing a model which aligns young people as collaborators in school improvement through research, there is an opportunity to develop a system which will benefit all involved. By partnering with the student body, the school will tap into their lived experiences to gain valuable insight into positive change. Over a period of years, this approach can potentially improve the school climate by promoting adult/young people relationships and developing mutual trust.

The model I propose () aims to adjust the school hegemony by redistributing its power dynamics. I argue that moving from an adult-dominated hierarchy to a collaborative system is a soft redistribution of power that supports all involved within schools. Traditionally, schools impose on young people, are tokenistic in their attempts to consult with them and place little regard for their rights. This model moves from imposition to collaboration and brings with it all the benefits described above.

5. Conclusion

This research has opened a window to new approaches in schools. As an ex-teacher, I am acutely aware that many young people find school challenging. My research helped me understand exactly why this was. Some young people don’t fit the mould. Due to no fault, their epistemic agency is underdeveloped, which schools often reinforce. By developing a culture that encourages research led by young people to contribute to improving their experience in school, there is an opportunity to empower them to transform their own lives.

This research improved young people’s confidence and trust in school; it empowered them to act and improved their epistemic agency and sense of self; one participant also explained that their involvement had improved their mental health. The participants also benefited from the attachment-like relationships with the YRT. The YRT, in turn, improved their research, communication and socio-emotional skills. This research has the potential to shed new light on ways of working in schools, and longitudinal research is now required to examine the benefits of YPDAR. My research findings need testing to ensure the findings endure over time and to explore exactly how YPDAR can positively impact school culture and environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dave McPartlan

Dave McPartlan is an honorary researcher at the University of Cumbria. He is involved in a number of school research projects across the north of England. His areas of interest lie in school mental health, research methodologies that enable collaborative working with young people, particularly in schools and research enabling children’s rights.

References

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage.

- Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research, 37(4), 191–222. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801

- Boyland, J. R. (2019). A social constructivist approach to the gathering of empirical data. Australian Counselling Research Journal, 13(2), 30–34. http://www.acrjournal.com.au/resources/assets/journals/Volume-13-Issue-2-2019/Manuscript5-ASocialConstructivistApproach.pdf

- Brady, L. (2017, March). Rhetoric to reality: An inquiry into embedding young people’s participation in health services and research a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/323893755.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, 2, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Broussine, M. (2008). Creative methods in organizational research (1st ed.). Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and contructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 509–535). Sage Publications Inc.

- Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Student voice across contexts: Fostering student agency in today’s schools. Theory into Practice, 59(2), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1705091

- Cottone, R. R. (2001). A social constructivism model of ethical decision making in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01941.x

- Cowie, B., & Khoo, E. (2017). Accountability through access, authenticity and advocacy when researching with young children. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(3), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1260821

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research. Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2017). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, Y. Denzin, N. Lincoln (eds.). (5th ed.). Sage.

- Ellingson, L. (2008). Engaging crystallization in qualitative research: An introduction. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Ennew, J., & Plateau, D. P. (2004). How to research the physical and emotional punishment of children.

- Eynon, B., Torok, J., & Gambino, L. M. (2013). Using E-portfolios in hybrid professional. To Improve the Academy, 32(1), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2013.tb00701.x

- Flecha, R. (2009). The dialogic sociology of the learning communities. In L. Apple & M. Ball, and S. Gandin (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of the sociology of education (pp. 340–348). Routledge.

- Gómez, A., Puigvert, L., & Flecha, R. (2011). Critical communicative methodology: Informing real social transformation through research. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(3), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410397802

- Groundwater-Smith, S., Dockett, S., & Bottrell, D. (2015). Participatory research with children and young people (1st ed.). Sage.

- Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action: Vol. 1. Reason and the rationalization of society. Beacon Press.

- Hi Kim, K. (2017). Transformative educational actions for children in poverty: Sen’s capa bility approach into practice in the Korean context. Education As Change, 21(1), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2338

- Hirsch, D., & A, J. (2007). Experiences of poverty and educational disadvantage. Education, 10. http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/2123.pdf

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). Introducing Critical Participatory Action Research. The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2

- Langhout, R. D., & Thomas, E. (2010). Imagining participatory action research in collaboration with children: An introduction. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1–2), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9321-1

- Latorre Beltran, A., & Gómez, J. (2005). Critical communicative methodology. First international congress of qualitative inquiry. University. http://www.iiqi.org/C4QI/httpdocs/qi2005/papers/beltran.pdf

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020). Health equity in England.

- Mercer, G. (2002). Emancipatory disability research. In L. Barnes, C. Oliver, & O. Barton (Eds.), Disability studies today (pp. 228–249). Polity Press.

- Moules, T., & Kirwan, N. (2005). Children’s fund Essex: Evaluation of the non-use of services in essex. Anglia Ruskin University.

- Mowat, J. G. (2015). Towards a new conceptualisation of marginalisation. European Educational Research Journal, 14(5), 454–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904115589864

- Puigverta, L., Christoub, M., & Holfordc, J. (2012). Critical communicative methodology: Including vulnerable voices in research through dialogue. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42(4), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2012.733341

- Råheim, M., Magnussen, L. H., Sekse, R. J. T., Lunde, Å., Jacobsen, T., & Blystad, A. (2016). Researcher–researched relationship in qualitative research: Shifts in positions and researcher vulnerability. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30996. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30996

- Richardson, L. (2000). Introduction—assessing alternative modes of qualitative and ethnographic research: How do we judge? Who judges? Qualitative Inquiry, 6(2), 251–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040000600206

- Ricoeur, P. (1976). Interpretative theory: Discourse and the surplus of meaning. The Texas Christian University Press.

- Schütz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1974). Structure of the life-world. Heinemann.

- Stringer, E., & Ortiz Aragon, A. (2021). Action research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Teschl, M., & Comim, F. (2005). Adaptive preferences and capabilities: Some preliminary conceptual explorations. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 229–247. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2005-07950-004

- van Lieshoult, F., & Cardiff, F. (2011). Innovative ways of analysing data with practitioners as co-researchers. In D. Higgs, J. Titchen, A. Horsfall, & D. Bridges (Eds.), Creative spaces for qualitative researching: Living research (pp. 223–234). Sense.

- van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. State University of New York Press.

- Varpio, L., Ajjawi, R., Monrouxe, L. V., O’Brien, B. C., & Rees, C. E. (2017). Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Medical Education, 51(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13124

- Way, A. K., Kanak Zwier, R., & Tracy, S. J. (2015). Dialogic interviewing and flickers of transformation: An examination and delineation of interactional strategies that promote participant self-reflexivity. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(8), 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566686

- Wöhrer, V., & Höcher, B. (2012). Tricks of the trade—negotiations and dealings between researchers, teachers and students. FQS Forum Qualitative Socialforschung, 13(1), 6–7. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1797/3319