ABSTRACT

Objective

Effective interventions are needed to mitigate effects of stress and anxiety from conception and up to two years postpartum (the first 1000 days), but it is unclear what works, for what populations and at what time points. This review aimed to synthesise evidence from existing reviews of the effects of stress and anxiety interventions.

Methods

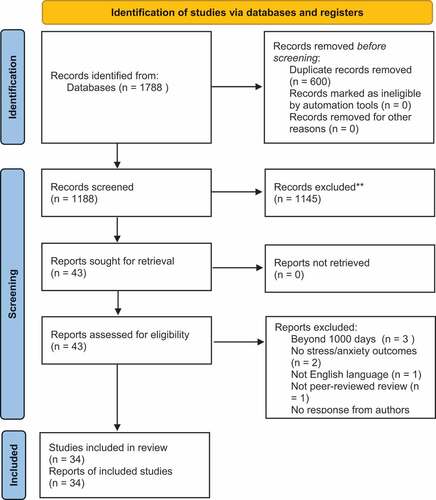

A systematic review of systematic reviews was conducted. PsycINFO, CINAHL, MEDLINE and the Cochrane databases were searched (inception to January 2020). Reviews were eligible if they examined effects of interventions during the first 1000 days on women’s stress and/or anxiety. Extracted data were narratively synthesised. Review quality was assessed using existing recommendations including the AMSTAR tool .

Results

Thirty-four reviews were eligible for inclusion; 21 demonstrated high methodological quality. Cognitive behavioural therapy demonstrates some beneficial effects for anxiety across the first 1000 days for general and at-risk populations. Support-based interventions demonstrate effects for stress and anxiety for at-risk mothers in the postpartum. Music, yoga and relaxation demonstrate some effects for stress and anxiety, but studies are limited by high risk of bias.

Conclusion

Existing evidence is inconsistent. Cognitive behavioural therapy and support-based interventions demonstrate some benefits. Further methodologically and conceptually robust research is needed.

Introduction

Conception to two years postpartum (the first 1000 days) is a transitional period during which an estimated 30% (Glover, Citation2011) and 15–20% (Dennis et al., Citation2017; National Mental Health Division HSE, Citation2017) of women experience stress and anxiety, respectively. Stress and anxiety are distinct yet highly related psychological constructs (Glover, Citation2011) associated with adverse obstetric, maternal and child outcomes, including higher risk of maternal depression (Norhayati et al., Citation2015), lower maternal–child attachment and responsivity (Respler-Herman et al., Citation2012), risk of preterm birth (Lobel et al., Citation2008), low birth weight (Witt et al., Citation2014), child health and developmental outcomes (Ingstrup et al., Citation2012; King & Laplante, Citation2005). Stress and anxiety during the first 1000 days arise from social, psychological, and sociodemographic factors (Bayrampour et al., Citation2018; Dunkel Schetter, Citation2011; Raikes & Thompson, Citation2005). They also arise from stressful life events (Bayrampour et al., Citation2018), including changing roles and responsibilities (Huizink & De Rooij, Citation2018; Huizink et al., Citation2017), having a child who is unwell (Saisto et al., Citation2008) and/or requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU; Loewenstein et al., Citation2019). Stress and anxiety can develop at any time during the first 1000 days, and levels can fluctuate over time (Farewell et al., Citation2018; Rallis et al., Citation2014). Prenatal stress is also associated with postpartum distress (Huizink et al., Citation2017), indicating potential longitudinal effects.

Interventions developed to reduce and/or prevent stress and anxiety differ by type, content and foci, including, for example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), psychoeducation, social support, relaxation and mindfulness. Interventions have targeted both general and vulnerable populations, including those experiencing or at risk for stress and/or anxiety, or who have experienced stressful life events. Interventions targeting more vulnerable populations are suggested to have greater effects (Fontein-Kuipers et al., Citation2014), although it remains unclear what interventions are best suited to what vulnerable populations. It is similarly unclear what interventions are most effective in general populations, and there is a lack of clarity about the impact of timing of intervention delivery on outcomes in both populations. Identifying effective interventions for women across the first 1000 days is critically important to improve maternal and child outcomes.

Bringing together findings from reviews of different interventions across the first 1000 days is essential to identify the most effective interventions, including for potentially vulnerable subgroups of women. Systematic reviews of reviews facilitate examination of the overall body of evidence that exists for a particular topic and enable the findings of individual reviews to be compared and contrasted (Aromataris et al., Citation2015). This is useful when reviews, potentially demonstrating heterogeneity, already exist (Aromataris et al., Citation2015). Systematic reviews of reviews consolidate findings across reviews to answer questions that are broader in scope than the original reviews (Higgins et al., Citation2020). By synthesising a broad body of evidence, systematic reviews of reviews can provide clearer information for healthcare decision-makers including researchers, healthcare providers, and patients (Higgins et al., Citation2020; Wolfenden et al., Citation2021). Given the diversity and heterogeneous findings for interventions for stress and anxiety in the first 1000 days noted in existing reviews, and the urgent need to better support women during this period, a systematic review of reviews provides a useful and efficient approach to examine effectiveness of stress and anxiety interventions in the first 1000 days. The aim of this systematic review of reviews is to examine the effectiveness of interventions for stress and anxiety during the period from conception to two years postpartum. This includes examination of effects in vulnerable populations, and by timing of intervention delivery and intervention characteristics.

Methods

Searches

This review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020165613) and conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., Citation2009). PsycINFO, CINAHL, MEDLINE and the Cochrane databases were searched from inception to January 2020. Reference lists of identified reviews were also searched.

Search terms

Search terms were designed to maximise identification of different intervention types through the use of a single ‘intervention’ term, and specific terms related to types of interventions, such as ‘cognitive behaviour* therapy’. See Supplementary File 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were a published systematic review, or a systematic review including a meta-analysis, that: (1) examined effects of interventions delivered at any point from conception to two years postpartum; and (2) included women from conception, during pregnancy and/or the first two years postpartum; and (3) examined effects on maternal stress and/or anxiety. Only studies published in English were eligible; there were no restrictions on date of publication.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (KMS, CF) independently screened titles and abstracts against eligibility criteria; Cohen’s Kappa statistic indicated good inter-rater agreement (κ = .74, p < .0005); disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus or recourse to a third reviewer (SR). Full-texts were screened against eligibility criteria by two reviewers (KMS, CF), with 100% reviewer agreement. Data were extracted using a standardised data extraction form by one reviewer (KMS) and checked by a second reviewer (CF). Data extracted included: review author, publication year, review focus, search strategy, participant characteristics, intervention characteristics, and results of the interventions on stress and anxiety outcomes; see Supplementary File 2. Findings of intervention effects were extracted at the level of included reviews rather than the original studies (Aromataris et al., Citation2015). Where reviews reported outcomes other than stress or anxiety, only stress and anxiety findings were extracted. The number of studies included in these reviews that reported on stress and anxiety and those that reported on additional/other outcomes were also noted.

Quality assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using the 11-item assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR) tool (Shea et al., Citation2009) and recommendations from Smith et al. (Citation2011). Two reviewers (KMS, CF) independently rated the quality of half the included reviews each, with all ratings cross-checked by the third reviewer (SR).

Data synthesis

Findings from individual reviews were narratively synthesised and are presented by timing of intervention delivery and/or review focus, as prenatal, postpartum, or perinatal; findings are also presented separately for general and vulnerable or ‘at-risk’ populations within these time periods. Vulnerable populations include women experiencing or at risk of mental health issues, and mothers of infants born preterm, with low birth weight and/or requiring admission to the NICU. Findings are also presented for intervention characteristics including intervention length, delivery (e.g. group or individual) and intervention components or types. All findings are synthesised at the level of the included reviews rather than the original studies (Aromataris et al., Citation2015); only those findings for stress and anxiety outcomes are included and presented in the narrative synthesis.

Results

The systematic search strategy identified 1188 unique reviews. Following title, abstract and full-text screening against eligibility criteria, 34 reviews were eligible for inclusion (). Characteristics of reviews are presented in . Overall, the quality of included reviews was high; 21 reviews rated as high quality, six reviews were medium quality and seven reviews were low quality. Review components demonstrating lower quality included duplicate study selection and data extraction, and provision of full details of included and excluded studies (Supplementary File 3). Reviews were rated as high quality unless otherwise stated below. Details of population and intervention information for sub-group examinations are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of included reviews.

Table 2. Population and intervention information for subgroup examination.

Prenatal interventions

Thirteen reviews examined prenatal interventions; eight reviews examined intervention effects in general pregnant populations and five examined intervention effects in vulnerable populations.

General populations

In general pregnant populations, findings from three reviews of mindfulness interventions demonstrated inconsistent effects for stress and anxiety (Dhillon et al., Citation2017; Hall et al., Citation2016; Matvienko-Sikar et al., Citation2016). There were no effects of exercise on anxiety in one review (Davenport et al., Citation2018); inconsistent effects were reported for non-pharmacological interventions, including mind–body, psychological, educational and support-based interventions in another review (Evans et al., Citation2019). Two reviews of music interventions demonstrated reductions in anxiety relative to controls (Corbijn van Willenswaard et al., Citation2017; Lin et al., Citation2019); no effects were observed for stress in one of these reviews, which demonstrated medium methodological quality (Corbijn van Willenswaard et al., Citation2017). Relaxation interventions, operationalised as muscle relaxation, massage and yoga, were reported to reduce anxiety and stress in one low-quality review (Fink et al., Citation2012).

Vulnerable populations

Five reviews examined interventions delivered to at-risk pregnant women. One review examining interventions including educational components or treatment regimens for women with pregnancy-specific anxiety and/or fear of childbirth reported no effect for pregnancy-specific anxiety (Stoll et al., Citation2018). One review of interventions for treating antepartum mental disorders identified one CBT intervention only which focused on anxiety disorder and demonstrated within-group anxiety reductions (Van Ravesteyn et al., Citation2017). One low-quality review of theory and group-based psychological interventions for women with elevated symptoms and/or high risk of perinatal mental health issues reported no effects for mindfulness, CBT or interpersonal therapy (IPT) interventions (Wadephul et al., Citation2016). Use of mindfulness interventions for women meeting self-report or diagnostic criteria for depressive or anxiety disorder demonstrated inconsistent effects for stress and some benefits for anxiety in another low-quality review (Shi & MacBeth, Citation2017). No studies of interventions for pregnant women with a history of miscarriage were identified in a final review (San Lazaro Campillo et al., Citation2017).

Postpartum interventions

Eleven reviews focused on interventions delivered in the postpartum period.

General populations

Two reviews were identified for general populations. One review of internet-delivered CBT interventions for women who had given birth in the last two years reported reductions in stress symptoms and anxiety (Lau et al., Citation2017). One medium-quality review of postnatal debriefing for women who had given birth in the last month found no effect of debriefing on anxiety (Bastos et al., Citation2015).

Vulnerable populations

Seven reviews examined interventions for mothers of infants born preterm, low birth weight and/or requiring admission to the NICU. CBT reduced anxiety but not stress for mothers of preterm infants in one review (Seiiedi-Biarag et al., Citation2019). Psychotherapeutic, behavioural, educational, or complementary and alternative interventions (Mendelson et al., Citation2017), and e-health interventions generally (Dol et al., Citation2017), did not demonstrate effects on anxiety or stress for mothers of infants in the NICU. Individualised, support-based and educational interventions reduced stress for mothers of preterm and low birth weight infants in two reviews (Brett et al., Citation2011; Mirghafourvand et al., Citation2017) and reduced anxiety for mothers of preterm infants in one review (Mirghafourvand et al., Citation2017). However, one of these reviews was rated as being of low quality (Brett et al., Citation2011). Music therapy demonstrated short-term reductions in anxiety for mothers of preterm infants in one medium-quality review (Bieleninik et al., Citation2016). Effects of kangaroo care were inconsistent for mothers of preterm and low birth weight infants in one low-quality review (Athanasopoulou & Fox, Citation2014).

Two reviews examined other vulnerable populations. One was a review of psychosocial interventions for women experiencing stress in the postpartum period, which reported reductions in stress for support-based stress-management programmes (Song et al., Citation2015). A medium-quality review of home-based support delivered by a professional or trained lay-professional for economically disadvantaged women who gave birth in the last 12 months found no evidence of positive effects of home visiting on stress or anxiety (Bennett et al., Citation2008).

Perinatal interventions

Ten reviews focused on interventions delivered across the perinatal period. Six reviews were conducted in general populations.

General populations

One review of mind–body interventions, including hypnotherapy and yoga, reported inconsistent effects across interventions (Marc et al., Citation2011). One review of parenting education interventions reported small to very small positive effects for interventions on parenting stress, with no long-term effects (Pinquart & Teubert, Citation2010). One review of CBT interventions reported reductions in anxiety within groups and relative to controls (Maguire et al., Citation2018), while a low-quality review examining computer and web-based interventions, including CBT, relaxation and behavioural activation found no evidence of effects for stress or anxiety (Ashford et al., Citation2016). One medium-quality review of mindfulness interventions reported within-subjects reductions in stress and anxiety but no effects relative to controls (Taylor et al., Citation2016). Finally, one low-quality review of yoga interventions reported reductions in anxiety and stress, although the studies included were of high risk of bias (Sheffield & Woods-Giscombé, Citation2016).

Vulnerable populations

Four reviews focused on at-risk populations during the perinatal period. One review of psychotherapeutic interventions for women meeting self-report or diagnostic criteria for anxiety and/or depression reported within-group reductions in anxiety for a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) intervention and three CBT interventions (Loughnan et al., Citation2018). Another review of internet-delivered psychotherapeutic interventions for women meeting self-report or diagnostic criteria for anxiety and/or depression reported reductions in anxiety relative to controls for CBT and behavioural activation interventions (Loughnan et al., Citation2019). Similarly, a review of perinatal mental health interventions for women experiencing stress, anxiety and depression reported reductions in anxiety for one behavioural activation intervention, one mindfulness intervention and one MBCT intervention relative to controls (Lavender et al., Citation2016). A medium-quality review of interventions to treat depression, anxiety and trauma-related disorders identified one CBT intervention that demonstrated reductions in anxiety (Nillni et al., Citation2018).

Intervention characteristics

Three reviews examined intervention length and reported no differences in outcomes based on intervention duration (Maguire et al., 2017; Mendelson et al., Citation2017; Wadephul et al., Citation2016). Eighteen reviews included group interventions or interventions including a group component but did not examine intervention effects by group format. Eleven reviews included individual interventions; a greater proportion of reviews examining individual interventions (63.63%) reported beneficial effects than reviews of group interventions (44.44%). Reviews of group interventions were more likely to report inconsistent findings (33.33%) and less likely to report null findings (22.22%) than reviews of individual interventions (18.18% and 36.36%, respectively).

Fourteen reviews examined potential differences in intervention effects by intervention components or ‘type’. Reviews rated as high-quality reported that music interventions were more effective when participants listened to music of their choosing in their own home than the music provided by the study team and in a medical setting (Lin et al., Citation2019). Imagery was reported as more effective than music for reducing anxiety in one review (Marc et al., Citation2011). Davenport et al. (Citation2018) reported that yoga had a beneficial effect on prenatal anxiety; other forms of exercise did not. Interventions based on or including mindfulness-based stress-reduction components were reported as more effective than other mindfulness interventions in one review (Hall et al., Citation2016). Song et al. (Citation2015) reported that support-based interventions are more effective than educational or interactive interventions, while Mendelson et al. (Citation2017) found no difference between psychotherapy, behavioural or educational interventions. No differences were found for therapist-delivered iCBT (Lau et al., Citation2017). One review reported that interventions focusing on women only were more effective than interventions including couples (Pinquart & Teubert, Citation2010).

Discussion

The current review identified 34 reviews examining effects of interventions for stress and/or anxiety during the first 1000 days. Intervention effects were inconsistent across included reviews and although the quality of the included reviews was high, reviews reported variable quality of included studies. Overall, this systematic review of reviews found insufficient evidence to definitively recommend any one intervention in pregnancy, postpartum, or across the first 1000 days from conception to two years postpartum, for either vulnerable or general populations. However, several potentially useful interventions were identified including CBT, support-focused interventions, music interventions and yoga and relaxation.

CBT demonstrated more consistent benefits for maternal anxiety than other intervention approaches, which is unsurprising as it is a well-validated treatment for anxiety in diverse populations (Maguire et al., Citation2018; Van Dis et al., Citation2019). The current review provides some support for the effectiveness of CBT across online and in-person group and individual modalities. Findings for maternal stress were less-frequently examined, limiting the inferences that can be made for this outcome. Support-focused interventions demonstrated benefits for both stress and anxiety but only in the postpartum period. Support-based interventions involve individualised or group-based provision of emotional, practical, and/or social support by healthcare professionals, and/or peers, partners, family and friends (Evans et al., Citation2019; Song et al., Citation2015). Support-based interventions were predominantly examined in the postpartum period, and further examination of effects during pregnancy would be beneficial. Music, yoga and relaxation interventions also demonstrated some reductions in stress and anxiety across the perinatal period in the included reviews, although reviews reported poor quality of included studies, indicating a need for more robust research to better determine intervention effects. Importantly, reviews reported no adverse effects of these approaches, or other approaches demonstrating inconsistent effects, such as exercise.

The findings of this review highlight a significant focus on depression, which has been noted previously for midwifery-delivered perinatal mental health interventions (Alderdice et al., Citation2013). This is evidenced by the high number of included reviews examining depression in addition to stress and anxiety, which were identified even though the literature search focused solely on stress and anxiety. Although highly associated, anxiety and stress conceptually differ from depression (Eysenck & Fajkowska, Citation2018). Similarly, where reviews examined both stress and anxiety, there was a greater focus on effects of interventions on anxiety than stress. Although anxiety and stress are also highly associated, they are distinct constructs with potentially differential mechanisms of effect on maternal and child outcomes (Glover, Citation2011). As perinatal distress is a complex and multifaceted construct (Wadephul et al., Citation2020), future trials of interventions should incorporate a broad range of outcomes, including stress and anxiety (Alderdice et al., Citation2013).

This review noted that most reviews examining vulnerable populations focused on mothers of preterm or low birth weight infants, and infants in the NICU. While these populations highly deserve stress and anxiety reduction supports, there is less evidence of the role of interventions in ‘general’ populations. Given the prevalence rates of perinatal stress and anxiety (National Mental Health Division HSE, Citation2017), general populations may include women with varying levels of stress and anxiety and women at-risk due to alternative predisposing factors. Further, only three reviews examining interventions related to other external sources of stress were identified; one of these represented an empty systematic review (San Lazaro Campillo et al., Citation2017). Given increasing the increasing impact of external stressors such as coronavirus disease 2019-related factors (Moyer et al., Citation2020) and climate-related natural disasters (Harville et al., Citation2010) on perinatal mental health, development and examination of interventions for stress and anxiety in the context of such stressors are needed.

Clearer understanding of effective intervention components is needed to guide future intervention development also. As less than half of included reviews examined the role of intervention components, no clear pattern can be identified for intervention components or types in the current review. Future research should also give greater consideration to timing of intervention delivery and how this may map on to women’s needs across the first 1000 days. The reviews included in this review did not tend to examine the timing of the intervention delivery. Stress and anxiety can fluctuate over the first 1000 days (Farewell et al., Citation2018) and fluctuations may be compounded by differences in population type, with different vulnerabilities or predisposing factors eliciting higher or lower levels of distress at different time points. In-depth examinations of women’s experiences and needs across the first 1000 days are essential to inform future intervention development and delivery (Alderdice et al., Citation2013).

The current review includes reviews of heterogeneous intervention types, which limits inferences that can be made about overall effectiveness across reviews. However, the aim of this systematic review of reviews was to provide an overview of the current state of the evidence supporting interventions for perinatal stress and anxiety. Thus, it was expected that a range of interventions would be examined. There is also heterogeneity related to the focus of some reviews on the modality of intervention delivery (e.g. internet-delivered) or a broader range of interventions (e.g. non-pharmacological interventions). These reviews tended to report more inconsistent effects, most likely due to the heterogeneity of the intervention ‘types’ included. Despite these limitations, this systematic review of reviews reaffirms the conclusions of some individual reviews and further highlights that interventions such as CBT and support-focused interventions demonstrate the most consistent benefits of the interventions reviewed. Synthesising a broad range of interventions in a systematic review of reviews provides up-to-date conclusions on the effects of stress and anxiety interventions in the first 1000 days beyond conclusions that can be obtained from individual reviews of more specific intervention types (Smith et al., Citation2011). The findings of the current review therefore provide a definitive synthesis of intervention effects to inform future research and practice to reduce stress and anxiety from conception and up to two years postpartum (Smith et al., Citation2011).

Conclusions

There is limited evidence to definitively support any one type of intervention across the first 1000 days. Findings of this review provide some evidence for CBT as a useful approach to address anxiety across the first 1000 days in general and vulnerable populations; individualised support-based interventions can reduce stress and anxiety for vulnerable populations in the postpartum. There is a need for more robust examinations of intervention effects, which adopt multifaceted conceptualisations of perinatal mental health and take population, intervention timing and delivery modality into account. Improving research on intervention effects in the first 1000 days is needed to better develop and implement effective interventions with the potential for real and meaningful change in the lives of women and infants.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (72.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (130.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial or personal relationships or competing interests to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alderdice, F., McNeill, J., & Lynn, F. (2013). A systematic review of systematic reviews of interventions to improve maternal mental health and well-being. Midwifery, 29(4), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.05.010

- Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare, 13(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

- Ashford, M. T., Olander, E. K., & Ayers, S. (2016). Computer- or web-based interventions for perinatal mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 197, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.057

- Athanasopoulou, E., & Fox, J. R. E. (2014). Effects of kangaroo mother care on maternal mood and interaction patterns between parents and their preterm, low birth weight infants: A systematic review. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21444

- Bastos, M. H., Furuta, M., Small, R., McKenzie-McHarg, K., & Bick, D. (2015). Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10(4), CD007194.

- Bayrampour, H., Vinturache, A., Hetherington, E., Lorenzetti, D. L., & Tough, S. (2018). Risk factors for antenatal anxiety: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(5), 476–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1492097

- Bennett, C., Macdonald, G., Dennis, J. A., Coren, E., Patterson, J., Astin, M., & Abbott, J. (2008). Home‐based support for disadvantaged adult mothers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(3), CD003759.https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003759.pub3

- Bieleninik, Ł., Ghetti, C., & Gold, C. (2016). Music therapy for preterm infants and their parents: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20160971–e20160971. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0971

- Brett, J., Staniszewska, S., Newburn, M., Jones, N., & Taylor, L. (2011). A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open, 1(1), e000023–e. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000023

- Corbijn van Willenswaard, K., Lynn, F., McNeill, J., McQueen, K., Dennis, C. L., Lobel, M., & Alderdice, F. (2017). Music interventions to reduce stress and anxiety in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmc Psychiatry, 17(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1432-x

- Davenport, M. H., McCurdy, A. P., Mottola, M. F., Skow, R. J., Meah, V. L., Poitras, V. M., Jaramillo Gracia, A., Gray, C. E., Barrowman, N., Riske, L., Sobierajski, F., James, M., Nagpal, T., Marchand, A., Nuspl, M., Slater, L. G., Barakat, R., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., & Ruchat, S. M. (2018). Impact of prenatal exercise on both prenatal and postnatal anxiety and depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(21), 1376–1385. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099697

- Dennis, C. L., Falah-Hassani, K., & Shiri, R. (2017). Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(5), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179

- Dhillon, A., Sparkes, E., & Duarte, R. V. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1421–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0726-x

- Dol, J., Delahunty-Pike, A., Anwar Siani, S., & Campbell-Yeo, M. (2017). eHealth interventions for parents in neonatal intensive care units: A systematic review. JBI Database Of Systematic Reviews And Implementation Reports, 15(12), 2981–3005. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003439

- Dunkel Schetter, C. (2011). Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 531–558. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727

- Evans, K., Spiby, H., & Morrell, J. C. (2019). Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce the symptoms of mild to moderate anxiety in pregnant women. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of women’s views on the acceptability of and satisfaction with interventions. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0936-9

- Eysenck, M. W., & Fajkowska, M. (2018). Anxiety and depression: Toward overlapping and distinctive features Introduction. Cognition and Emotion, 32(7), 1391–1400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1330255

- Farewell, C. V., Thayer, Z. M., Puma, J. E., & Morton, S. (2018). Exploring the timing and duration of maternal stress exposure: Impacts on early childhood BMI. Early Human Development, 117, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.12.001

- Fink, N. S., Urech, C., Cavelti, M., & Alder, J. (2012). Relaxation during pregnancy: What are the benefits for mother, fetus, and the Newborn? A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 26(4), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e31823f565b

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y. J., Nieuwenhuijze, M. J., Ausems, M., Bude, L., & De Vries, R. (2014). Antenatal interventions to reduce maternal distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12500

- Glover, V. (2011). Prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(4), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02371.x

- Hall, H. G., Beattie, J., Lau, R., East, C., & Anne Biro, M. (2016). Mindfulness and perinatal mental health: A systematic review. Women & Birth, 29(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.08.006

- Harville, E., Xiong, X., & Buekens, P. (2010). Disasters and perinatal health: Asystematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 65(11), 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0b013e31820eddbe

- . https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1565873

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A., (editors.) (2020). Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Huizink, A. C., & De Rooij, S. R. (2018). Prenatal stress and models explaining risk for psychopathology revisited: Generic vulnerability and divergent pathways. Development and Psychopathology, 30(3), 1041–1062. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418000354

- Huizink, A. C., Menting, B., De Moor, M. H. M., Verhage, M. L., Kunseler, F. C., Scheuengel, C., & Oosterman, M. (2017). From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: A longitudinal study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20(5), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0746-5

- Ingstrup, K. G., Schou Andersen, C., Ajslev, T. A., Pedersen, P., Sorensen, T. I., & Nohr, E. A. (2012). Maternal distress during pregnancy and offspring childhood overweight. Journal of Obesity, 462845. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/462845

- King, S., & Laplante, D. P. (2005). The effects of prenatal maternal stress on children’s cognitive development: Project ice storm. Stress, 8(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890500108391

- Lau, Y., Htun, T. P., Wong, S. N., Tam, W. S. W., & Klainin-Yobas, P. (2017). Therapist-supported Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(4), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6712

- Lavender, T. J., Ebert, L., & Jones, D. (2016). An evaluation of perinatal mental health interventions: An integrative literature review. Women and Birth, 29(5), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.04.004

- Lin, C. J., Chang, Y. C., Chang, Y. H., Hsiao, Y. H., Lin, H. H., Liu, S. J., Chao, C. A., Wang, H., & Yeh, T. L. (2019). Music interventions for anxiety in pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal Of Clinical Medicine, 8(11), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111884

- Lobel, M., Cannella, D. L., Graham, J. E., DeVincent, C., Schneider, J., & Meyer, B. A. (2008). Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 27(5), 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013242

- Loewenstein, K., Barroso, J., & Phillips, S. (2019). The experiences of parents in the neonatal intensive care unit an integrative review of qualitative studies within the transactional model of stress and coping. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 33(4), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000436

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.001

- Loughnan, S. A., Joubert, A. E., Grierson, A., Andrews, G., & Newby, J. M. (2019). Internet-delivered psychological interventions for clinical anxiety and depression in perinatal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 22(6), 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00961-9

- Loughnan, S. A., Wallace, M., Joubert, A. E., Haskelberg, H., Andrews, G., & Newby, J. M. (2018). A systematic review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(5), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0812-7

- Maguire, P. N., Clark, G. I., & Wootton, B. M. (2018). The efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy for the treatment of perinatal anxiety symptoms: A preliminary meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 60, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.10.002

- Marc, I., Toureche, N., Ernst, E., Hodnett, E. D., Blanchet, C., Dodin, S., & Njoya, M. M. (2011). Mind-body interventions during pregnancy for preventing or treating women’s anxiety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD007559. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007559.pub2

- Matvienko-Sikar, K., Lee, L., Murphy, G., & Murphy, L. (2016). The effects of mindfulness interventions on prenatal well-being: A systematic review. Psychology & Health, 31(12), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2016.1220557

- Mendelson, T., Cluxton-Keller, F., Vullo, G. C., Tandon, D., & Noazin, S. (2017). NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 139(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1870

- Mirghafourvand, M., Ouladsahebmadarek, E., Hosseini, M. B., Heidarabadi, S., Asghari-Jafarabadi, M., & Hasanpour, S. (2017). The effect of creating opportunities for parent empowerment program on parent’s mental health: A systematic review. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, 27(2), 1–9. DOI:10.5812/ijp.5704

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Grp, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moyer, C. A., Compton, S. D., Kaselitz, E., & Muzik, M. (2020). Pregnancy-related anxiety during COVID-19: A nationwide survey of 2740 pregnant women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(6), 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01073-5

- National Mental Health Division HSE. (2017). Specialist perinatal mental health services: Model of Care for Ireland. Health Service Executive. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/specialist-perinatal-mental-health/specialist-perinatal-mental-health-services-model-of-care-2017.pdf

- Nillni, Y. I., Mehralizade, A., Mayer, L., & Milanovic, S. (2018). Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.004

- Norhayati, M. N., Hazlina, N. H., Asrenee, A. R., & Emilin, W. M. (2015). Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 1(175), 34–52.10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.04

- Pinquart, M., & Teubert, D. (2010). Effects of parenting education with expectant and new parents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019691

- Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20044

- Rallis, S., Skouteris, H., McCabe, M., & Milgrom, J. A. (2014). A prospective examination of depression, anxiety and stress throughout pregnancy. Women and Birth, 27(4), E36–E42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2014.08.002

- Respler-Herman, M., Mowder, B. A., Yasik, A. E., & Shamah, R. (2012). Parenting beliefs, parental stress, and social support relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(2), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9462-3

- Saisto, T., Salmela-Aro, K., Nurmi, J. E., & Halmesmaki, E. (2008). Longitudinal study on the predictors of parental stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 29(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820802000467

- San Lazaro Campillo, I., Meaney, S., McNamara, K., & O’Donoghue, K. (2017). Psychological and support interventions to reduce levels of stress, anxiety or depression on women’s subsequent pregnancy with a history of miscarriage: An empty systematic review. BMJ Open, 7(9), e017802. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017802

- Seiiedi-Biarag, L., Mirghafourvand, M., & Ghanbari-Homayi, S. (2019). The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy on psychological distress in the mothers of preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 41(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2019.1678019.

- Shea, B. J., Hamel, C., Wells, G. A., Bouter, L. M., Kristjansson, E., Grimshaw, J., Henry, D. A., & Boers, M. (2009). AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1013–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009

- Sheffield, K. M., & Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2016). Efficacy, Feasibility, and acceptability of perinatal yoga on women’s mental health and well-being: A systematic literature review. Journal Of Holistic Nursing, 34(1), 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010115577976

- Shi, Z., & MacBeth, A. (2017). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on maternal perinatal mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 8(4), 823–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0673-y

- Smith, V., Devane, D., Begley, C. M., & Clarke, M. (2011). Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-15

- Song, J. E., Kim, T., & Ahn, J. A. (2015). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for women with postpartum stress. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing: Clinical Scholarship for the Care of Women, Childbearing Families, & Newborns, 44(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12541

- Stoll, K., Swift, E. M., Fairbrother, N., Nethery, E., & Janssen, P. (2018). A systematic review of nonpharmacological prenatal interventions for pregnancy-specific anxiety and fear of childbirth. Birth, 45(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12316

- Taylor, B. L., Cavanagh, K., & Strauss, C. (2016). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in the perinatal period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One, 11(5) e0155720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155720.

- Van Dis, E. A. M., van Veen, S. C., Hagenaars, M. A., Batelaan, N. M., Bockting, C. L. H., van den Heuvel, R. M., Cuijpers, P., & Engelhard, I. M. (2019). Long-term outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety-related disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 77(3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3986

- Van Ravesteyn, L. M., Lambregtse-van den Berg, M. P., Hoogendijk, W. J. G., & Kamperman, A. M. (2017). Interventions to treat mental disorders during pregnancy: A systematic review and multiple treatment meta-analysis. Plos One, 12(3), e0173397–e. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173397

- Wadephul, F., Glover, L., & Jomeen, J. (2020). Conceptualising women’s perinatal well-being: A systematic review of theoretical discussions. Midwifery, 81, 102598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102598

- Wadephul, F., Jones, C., & Jomeen, J. (2016). The impact of antenatal psychological group interventions on psychological well-being: A systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative evidence. Healthcare, 4(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4020032

- Witt, W. P., Litzelman, K., Cheng, E. R., Wakeel, F., & Barker, E. S. (2014). Measuring stress before and during pregnancy: A review of population-based studies of obstetric outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1233-x

- Wolfenden, L., Barnes, C., Lane, C., McCrabb, S., Brown, H. M., Gerritsen, S., Barquera, S., Samara Véjar, L., Muguía, A., & Yoon, S. L. (2021). Consolidating evidence on the effectiveness of interventions promoting fruit and vegetable consumption: An umbrella review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(11). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01046-y