ABSTRACT

Background

Up to 39% of women who experience perinatal bereavement proceed to develop Post-Traumatic-Stress-Disorder (PTSD), with this large proportion meriting treatment. Before setting-up a treatment service for postnatal women who are experiencing psychological trauma, it is important to identify what therapies have been used in-the-past to address this problem.

Aim

To scope for research that has implemented therapies to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, for potential inclusion in a flexible treatment package.

Method

A scoping review mapped coverage, range, and type of research that has reported on prior therapies used to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement.

Findings

Due to the dearth of papers that directly addressed perinatal bereavement, we widened the scope of the review to view what treatments had been used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth. Out of 23 studies that report on effectiveness of therapies used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth, only 4-focused upon treating PTSD post perinatal bereavement (3 effective/1 ineffective). Successful treatments were reported by Kersting et al. (2013), who found CBT effective at reducing PTSD symptoms post-miscarriage, termination for medical reasons, and stillbirth (n = 33 & n = 115), and Navidian et al. (2s017)) found that 4-sessions of grief-counselling reduced trauma symptoms post-stillbirth in (n = 50) women. One study by Huberty et al. (2020found on-line yoga to be ineffective at reducing PTSD symptoms post-stillbirth.

Conclusions

A dearth of research has explored effectiveness of therapies for treating psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement and post-childbirth, with need to develop and test a research informed flexible counselling package.

Introduction

Around 5.5 million perinatal deaths occur each year globally (Lawn et al., Citation2014), which can have wide-reaching impacts for communities (Heazell et al., 2021). In the UK, the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (Sands), UK (Citation2018) report that in 2018 five-thousand babies died within 4-weeks of life. Experiencing perinatal bereavement can trigger a natural bereavement process, but for many it prompts more serious mental health problems. For example, a systematic review by Christiansen (Citation2017) reports that up to 39% of women who experience perinatal bereavement proceed to develop Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In contrast, PTSD has a prevalence of 4–17% in the postpartum period post-childbirth (Grisbrook & Letourneau, Citation2021).

PTSD creates disturbing responses to the trauma experienced, which includes behavioural changes, suicidal thoughts, replay of distressing memories, nightmares, flashbacks, irritability, social avoidance, and easy amazement/shock, which together decrease life satisfaction and functioning (Bromley et al., 2017; World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018). When PTSD is specifically associated with a perinatal loss, these features are compounded by a grieving process, loneliness caused by the loss, feelings of betrayal by one’s body, and envy of other mothers (Burden et al., Citation2016).

The large number of women, who experience psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, makes advancement of care not only humane but necessary, with clear need to develop a pathway for referring this population of women. Symptoms of PTSD affect wellbeing, with a number of reviews having investigated effectiveness of PTSD treatments in general (Barrera et al., Citation2013; Bisson et al., Citation2013; Karatzias et al., Citation2019., Roberts et al., Citation2015., Watts et al., Citation2013), with a meta-analyses supporting efficacy of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Eye-Movement-Desensitisation-and-Reprocessing (EMDR; Bisson et al., Citation2013). Therapeutic approaches have proved successful for a range of PTSD survivors (e.g. rape victims, survivors of childhood abuse, refugees, combat veterans, and victims of motor vehicle accidents (E.B. Foa et al., Citation2009).

Delivery of effective care for psychological trauma will prevent a range of consequences, such as impairment to social interactions and capacity to work, through ‘re-experiencing the trauma event’ in the form of nightmares, flashbacks, continual replay, intrusive thoughts, and images, which is what is experienced when a person has PTSD (APA, Citation2013). Heazell et al. (Citation2016) asserts that when a perinatal bereavement occurs, the health care system fails parents through the absence of empathetic services. What we do know is that psychological trauma, such as PTSD, has devastating effects on wellbeing and relationships (Armstrong, 2006; Taft et al., Citation2011). Hence, our goal is to advance treatments for psychological trauma experienced by women who have had a perinatal bereavement, through developing a flexible treatment package that will accommodate individualised care provision.

Before setting up a treatment service for postnatal women who are experiencing psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, it is first important to find out what therapies have been used in the past to address this particular problem. We also appreciate that fathers and co-parents may also develop psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, which is a matter for future widening of any developed and tested treatment package.

To determine potential content of a treatment package, first it is important to identify what therapies have already been used to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, which potentially could be included in a flexible treatment package called CFT-SPIRIT. Hence, our aim was to scope for research that has implemented therapies to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, for further consideration and potential inclusion in a flexible treatment package for future piloting and testing.

Method

A scoping review was selected because our aim was to map key concepts (Mays et al., Citation2001), which involved inspecting coverage, range, and type of research that has reported on therapies used to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement. The intention was not to describe findings in detail, but instead to map fields that address this area of interest (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The purpose of undertaking a scoping review was to understand the ‘lay of the land’ of prior therapies used to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, for possible inclusion in our flexible CFT-SPIRIT treatment package. According to Mays et al. (Citation2001), scoping reviews include findings from a range of different study methods (Davis et al., Citation2009). Taking this approach, we included the full range of research methods reported, which makes using formal meta-analytic and rating methods difficult to implement, if not impossible. Findings from our scoping review focused upon the range of treatments identified, with quantitative assessment limited to a tally of number of sources reporting upon a particular treatment. Hence, no scored evaluation tools were used to score the literature retrieved. This approach differs to a systematic review, which selects sources based upon specific study type, such as Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT), and then proceeds to impose quality standards upon them. This scoping review was conducted in a meticulous and transparent way (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Citation2001; Mays et al., Citation2001), following the recommended stages of Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005).

(1) Identifying the research question

What research has evaluated effectiveness of therapies used to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement? Due to the dearth of papers that directly addressed perinatal bereavement, we widened the scope of the review to view what treatments had been used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth, for purpose of considering shared systems.

(2) Identifying relevant studies

Studies were identified via electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, Cochrane Library), reference lists, and hand-searching of key journals. A combined free-text and thesaurus approach identified relevant papers for inclusion. The following search terms were used: (‘Posttraumatic Stress Disorder’ OR ‘Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic’ OR ‘Stress, Psychological’ OR ‘complex post-traumatic stress disorder’ OR ‘complex PTSD’ OR ‘Life Change Events’ OR ‘Psychological Trauma’ OR Psychotherapy” Events” OR ‘Psychological Trauma’ OR Psychotherapy) AND (Birth OR childbirth) N5 trauma*) OR (Birth OR childbirth) N5 fear) OR childbirth OR child birth OR labour OR ‘delivery, obstetric’ OR ‘Pregnancy complications’ OR caesarean OR stillbirth OR bereavement OR ‘perinatal death’) AND SU (treatment or intervention or therapy). No date limit was selected, and ‘clinical queries’ was set to ‘Therapy-High Specificity’. Studies required to be written in English.

(3) Study selection

Inclusion criteria involved studies that addressed therapies used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth, with the gate widened to ‘post childbirth’ to reduce risk of missing papers that included perinatal bereavement as a subcategory. The WHO definition of perinatal period was applied, which defines it as commencing at 22 completed weeks (154 days) gestation to 7 completed days post-childbirth (WHO, Citation2021). Papers selected met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the study consisted of a therapeutic intervention used to treat women experiencing psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement or childbirth; (2) Papers that addressed Acute Stress Disorder (ASD), Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSS), PTSD, and Complex-PTSD; (3) the paper was published in English; and (4) full-text paper was available for review. No exclusion criteria were applied.

(4) Charting the data

Results were sifted, recorded, and organised into themes according to treatments used.

Two investigators independently read each article and organised the 23-papers into themes of therapies used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth. Titles for themes were negotiated and agreed, with any difference of opinion easily resolved through discussion.

(5) Collating, summarising and reporting results

Papers were themed and summarised, with no ‘weighting’ of evidence carried out. This approach helped us gain insight into what therapies have been used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth, and which ones were effective. Both authors agreed the 10-categories of therapeutic interventions, regardless of their quality. We took this approach because we wanted to capture all therapies that had been used in our selected context, before continued review of their effectiveness in other settings. During process, discussions took place which led to eventual consensus.

Results

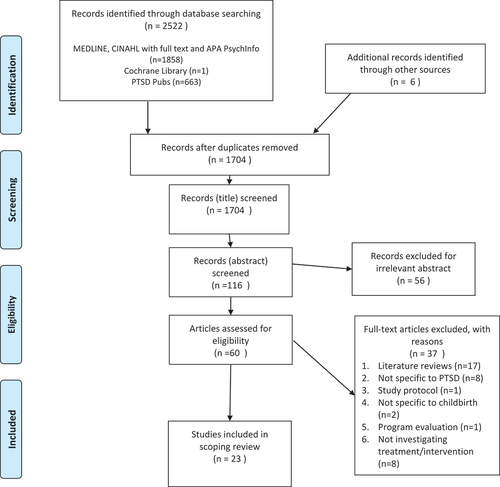

A total of 2522 papers were found, with a further 6 identified through hand-searching reference lists. After 824 duplicate papers were excluded, 1704 were screened, which resulted in 23 being identified as focussing upon therapies used to treat psychological trauma post-childbirth ().

The 23 papers identified were divided into 10-themes of therapies, with only 4 directly addressing perinatal bereavement ().

Table 1. Studies that have assessed PTSD treatments post childbirth.

Treatment 1: CBT

Six studies investigated effectiveness of CBT as a treatment for psychological trauma post-childbirth. (1) Sorenson (Citation2003) conducted a quasi-experimental pre-post-test study, which implemented short-term group cognitive therapy to women (n = 9) who self-identified as being traumatised by healthcare provider interaction. Pre-intervention trauma was assessed using the Posttraumatic-Childbirth-Stress-Inventory (PTCS; Sorenson, Citation2003), with no post-intervention measurements taken. (2) Ayers et al. (Citation2007) explored 2 case-studies of women diagnosed with PTSD post-emergency Caesarean Section (CS). Both received face-to-face CBT, with only oral accounts of improvements stated. (3) Nieminen et al. (Citation2016) conducted an RCT with women who met PTSD criteria using the Traumatic-Event-Scale (TES; Wijma et al., Citation1997). Participants received treatment immediately (n = 115) .or 5-months post-delivery (n = 113), which consisted of 8-online internet-based CBT modules. Both groups had significantly lower mean TES and Impact-of-Events-Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997) scores post-treatment (p = <0.05). (4) Reina et al. (Citation2019) analysed a case-study involving (n = 1) woman who met PTSD criteria using the Posttraumatic-Checklist-for-Civilians (PCL5; Blevins et al., Citation2015), IES (Horowitz et al., Citation1979) and Posttraumatic-Cognitions-Inventory (PTCI)(Foa et al., 1999). Thirty-months post-childbirth, this participant received face-to-face CBT, which effectively reduced symptoms.

Out of 6 studies, only two addressed women who had experienced perinatal bereavement. (5) A pilot by Kersting et al. (Citation2011) and subsequent RCT (Kersting et al., Citation2013) assessed effectiveness of internet-based CBT for women who miscarried, had a termination, or a stillbirth. PTSD was measured prior-to and post-intervention using the Impact-of-Event-Scale (IES; Horowitz et al., Citation1979), with marked improvement in PTSD post-intervention (n = 33) compared with the control (n = 26)(p = 0.012). (6) The second Kersting et al. (Citation2013) study used the German version of the IES-Revised (IES-R; Maercker & Schützwohl, Citation1998), and found significant improvements in the treatment group (n = 115) compared with the control (n = 113)(p = 0.001).

Out of the 6 studies found, the four experimental one’s were limited in numbers (n = 9–115; Kersting et al., Citation2013, Citation2011; Nieminen et al., Citation2016; Sorenson, Citation2003), and two were self-limiting case-studies involving only (n = 1–2) women. None addressed the new ICD-11 diagnosis of Complex-PTSD (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018), which is important because Hollins Martin et al. (Citation2021) found that out of (n = 74) women who had experienced perinatal bereavement; (n = 8; 10.8%) met the criteria for PTSD and (n = 22; 29.7%) CPTSD.

Treatment 2: EMDR

Three studies investigated effectiveness of EMDR as a treatment. (1) Sandström et al. (Citation2008) conducted a pilot which assessed effectiveness of EMDR on (n = 4) women who met criteria for PTSD using the TES (Wijma et al., Citation1997). The two women who completed the course, experienced reduced PTSD symptoms immediately post-treatment and again at 12–36 months. (2) Stramrood et al. (Citation2011) also evaluated effectiveness of EMDR at treating (n = 3) pregnant women who developed PTSD post-previous traumatic delivery. No scales were used, with only verbal reports of symptom reduction and increased confidence about impending delivery. (3) An RCT by Chiorino et al. (Citation2019) also assessed effectiveness of EMDR at reducing PTSD symptoms in (n = 20) women who had experienced traumatic delivery using the IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997), with no significant differences found compared with the control (n = 20)(p = 0.124).

Out of these three studies, none addressed perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD and again participant numbers were limited (n = 3–20).

Treatment 3: Debriefing

Two studies explored effects of debriefing on PTSD symptoms post-childbirth. (1) An observation study by Meades et al. (Citation2011) tested effects of midwife-led one-to-one debriefing on women diagnosed with PTSD post-childbirth. The Symptom-Scale-Self-Report (PSS-SR; E. Foa et al., Citation1993) found a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms in the intervention group (n = 46) compared with control (n = 34)(p = <0.05). (2) An additional RCT by Priest et al. (Citation2003) tested whether debriefing was effective at preventing PTSD in women (n = 1745) who had delivered a healthy infant. The intervention group (n = 875) received a single standardised debriefing session at 24–72 hours post-delivery, with trauma symptoms measured using the IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997). Compared against the control (n = 870) no significant differences were found.

In summary, debriefing reduced PTSD scores in the Meades et al. (Citation2011) study, but not the Priest et al. (Citation2003), with neither of these papers addressing women who had experienced perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 4: Counselling

Four studies explored effects of counselling on psychological trauma post-childbirth. (1) Ryding et al. (Citation2004) used the IES (Horowitz et al., Citation1979) to test effects of group counselling on mothers (n = 162) who had received emergency CS, with no difference found compared with the control (n = 65)(p = 0.5). (2) Gamble et al. (Citation2005) conducted an RCT that examined effects of counselling on women (n = 103) with PTSD symptoms post-traumatic birth, using the Mini-International-Neuropsychiatric-Interview-Post-traumatic-Stress-Disorder (MINI-PTSD) scale (Sheehan et al., Citation1998). The intervention group (n = 50) received counselling in the ward from a specialist midwife and the control (n = 53) routine care, with no differences found at 4–6 weeks and 3-months follow-up. (3) Asadzadeh et al. (Citation2020) explored effects of counselling on PTSD symptoms in (n = 90) Iranian women post-delivery. A significant reduction in PTSD-Checklist (PCL-5; Blevins et al., Citation2015) scores was found in the intervention group (n = 45) at 4–6 weeks (p = 0.0001) and 3-months postpartum (p = 0.0001), compared against the control (n = 45). (4) A semi-experimental study by Navidian et al. (Citation2017) provided 4-sessions of grief counselling across a 2-week period to treat (n = 50) women post-stillbirth using the Prenatal-Posttraumatic-Stress-Questionnaire (PPQ; Navidian et al., Citation2017). PTSD symptoms were significantly reduced compared against control (n = 50)(p = 0.0001).

Out of the four studies found, one addressed perinatal bereavement and none Complex-PTSD, with success in treating PTSD in only 2 of the 4 studies (Asadzadeh et al., Citation2020; Navidian et al., Citation2017), possibly due to differences in counselling methods used.

Treatment 5: Expressive writing

Two papers explored effects of expressive writing on PTSD symptoms post-childbirth. (1) An RCT by Di Blasio et al. (Citation2015) investigated whether an expressive writing intervention decreased trauma symptoms using the Perinatal-PTSD-Questionnaire (PTS; DeMier et al., Citation2000), with women (n = 113) in the intervention group experiencing significantly reduced trauma scores. (2) Horsch et al. (Citation2016) also measured effects of expressive writing on PTSD scores in mothers (n = 33) who had delivered extreme preterm babies, using the PTS (DeMier et al., Citation2000). Results showed reduced maternal PTSD in the intervention group, compared against the control (n = 32).

Both of these studies indicate that expressive writing has potential to reduce trauma symptoms post-childbirth, with numbers too low to be anything more than indicative. Again, neither study addressed women with Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 6: Self-help materials

One RCT by Slade et al. (Citation2020) explored whether psychological self‐help materials (leaflet & on-line film) lowered PTSD scores in (n = 336) postnatal women using the Clinician-Administered-PTSD-Scale (CAPS-5; Blake et al., Citation1995). At 12-weeks, results did not differ from the control. Again, this study did not address perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 7: Family support programme

One RCT by Sun et al. (Citation2017) examined effects of a family‐support program on trauma symptoms in pregnant women (n = 124) who delivered an infant with a foetal abnormality. Using the IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997), trauma levels were significantly lower post-intervention (p = 0.025). Again, these results are only indicative and did not address perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 8: Tetris

One RCT by Horsch et al. (Citation2017) evaluated whether number of intrusive trauma memories were reduced in (n = 28) women post-emergency CS, through engaging with a visuospatial handheld gaming device (Tetris) for 15-minutes within the first 6-post-operative hours. Compared with control, the intervention group (n = 28) reported fewer intrusive traumatic memories. Again, this intervention did not address perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 9: Yoga

An RCT by Huberty et al. (Citation2020) assessed effects of a ‘yoga intervention’ upon PTSD scores of women (n = 90) who had experienced stillbirth. Using the IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997), non-significant differences in PTSD symptoms were found post-intervention. Again, participant numbers were small, and this study did not address perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Treatment 10: Compassion focused therapy (CFT)

Two papers explored effects of CFT on PTSD post-childbirth. (1) Mitchell et al. (Citation2018) evaluated effectiveness of an online CFT package, which outlined techniques for increasing self-compassion. Scores from (n = 262) women showed an increase in self-compassion and a decrease in PTSD symptoms using the IES‐Revised (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997). (2) A further RCT by Lennard et al. (Citation2020) tested effectiveness of a self-compassion intervention upon (n = 94) postnatal women using the IES‐Revised (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997), with significant improvement in scores found (p = 0.028) in the intervention group.

These two studies report success of CFT as a treatment for PTSD post-childbirth, with success reported in many other contexts by Leaviss and Uttley (Citation2015), Kirby et al. (Citation2017), and Ferrari et al. (Citation2019). Again, no studies were found to address perinatal bereavement or Complex-PTSD.

Discussion

This scoping review yielded 23-studies that report on effectiveness of therapies for treating psychological trauma post-childbirth, with only 4 specifically focussing upon perinatal bereavement (3 effective/1 ineffective). Kersting et al. (Citation2011), Kersting et al. (Citation2013) found CBT effective at reducing PTSD symptoms post miscarriage, termination for medical reasons and stillbirth, and Navidian et al. (Citation2017) found that 4-sessions of grief counselling were effective at reducing trauma symptoms post-stillbirth. No studies were found that address the new ICD-11 diagnosis of Complex-PTSD (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018). To differentiate between PTSD and Complex-PTSD, the ICD-11 (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018) defines PTSD (code6B40) and Complex-PTSD (code6B41) as two distinct sibling conditions under one parent category of ‘disorders associated with stress’:

PTSD is composed of 3 symptom clusters: (1) Re-experiencing trauma in the here and now, (2) Avoidance of traumatic reminders, (3) A persistent sense of current threat manifested by exaggerated startle and hypervigilance.

CPTSD includes the (1–3) aforementioned clusters, with an additional three that reflect ‘Disturbances in Self-Organisation’ (DSO) (Maercker et al., 2013): (4) Affect dysregulation, (5) Negative self-concept, (6) Disturbances in relationships.

Results have shown a deficit in interest in implementing and testing therapies to treat psychological trauma post-perinatal bereavement, which is a different picture to other contexts (Barrera et al., Citation2013; Bisson et al., Citation2013; Karatzias et al., Citation2019., Roberts et al., Citation2015., Watts et al., Citation2013). Areas for potential testing include CFT. For example, Leaviss and Uttley (Citation2015) reviewed 14 studies that have implemented CFT treatments, with CFT showing promise as an intervention for mood disorders, and clients high in self-criticism. A later meta-analysis by Kirby et al. (Citation2017) of 21 RCT’s conducted over 12 years (n = 1,285) showed significant differences between-group differences in change scores on self-report measures of compassion, self-compassion, mindfulness, depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and well-being. Ferrari et al. (Citation2019) conducted a meta-analysis of 27 RCT’s of self-compassion interventions and their effects on psychosocial outcomes. Results showed that self-compassion led to a significant improvement across 11 diverse psychosocial outcomes; eating behaviour; rumination; self-compassion, stress, depression, mindfulness, self-criticism, and anxiety. In particular, the Ferrari et al. (Citation2019) review supports the efficacy of using compassion-based interventions across a range of outcomes and diverse populations. The evidence presented in the Leaviss and Uttley (Citation2015), Kirby et al. (Citation2017), and Ferrari et al. (Citation2019) reviews, support that a flexible-phased CFT intervention could profoundly benefit women with PTSD and CPTSD post perinatal bereavement.

Due to the dearth of research that reports on treatments for women who have developed PTSD and Complex-PTSD post-perinatal bereavement, our team would like to implement a feasibility RCT to evaluate effectiveness of a flexible CFT informed treatment package that addresses all 6 symptom clusters (CFT-SPIRIT). Both Lennard et al. (Citation2020) and Mitchell et al. (Citation2018) support benefits of using CFT focused interventions to treat PTSD post-childbirth (studies 11 & 13 ), with evidence supporting success of CFT in other contexts (Ferrari et al., Citation2019; Kirby et al., Citation2017; Leaviss & Uttley, Citation2015).

Herman (Citation1992) promotes use of a phase-based model (Cloitre et al., Citation2012a), which addresses DSO symptom clusters of Complex-PTSD. First, this phased model treats problems in day-to-day functioning, with exploration of trauma subsequently introduced (Cloitre et al., Citation2012b). The rationale for this sequencing is:

To increase emotional, psychological and social resources, to improve functioning in daily-life.

To use resources learned to enhance effectiveness of trauma-focused work.

For co-morbid problems, an additional stabilisation process is considered.

Whilst there is support for the two-fold approach (1 & 2; e.g. Cloitre et al., Citation2010), an additional stabilisation phase (3) may be necessary for some clients (De Jongh et al., Citation2016). For example:

Those with co-morbid Substance Use Disorder (SUD; Mills et al., Citation2012), where SUD and PTSD interventions are implemented simultaneously.

PTSD with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD; Harned et al., Citation2014), where BPD and PTSD interventions are implemented concurrently.

A range of studies that have used CFT acknowledge its benefits in a range of applications (Leaviss & Uttley, Citation2015; Kirby et al., Citation2017; Ferrari et al., Citation2019; Charter for Compassion: http://charterforcompassion.org/). Hence, a CFT approach will inform our flexible counselling package. We anticipate that our results will be of interest to maternity care professionals, psychologists and mental health practitioners, and we plan to use our findings to inform development of a flexible treatment package for women experiencing psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement, which we will call CFT-SPIRIT.

There are some limitations of this study. First, scoping reviews have characteristic restrictions, given that they focus on breadth rather than depth of information. Nonetheless, this method was appropriate because we wanted a global overview of therapies that have been reported to treat psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement. Second, we limited the included studies to those written in English, which excluded therapies that have been used in cultures where papers have not been published in English.

Conclusion

This paper reports a scoping review of literature that has evaluated treatments for psychological trauma post perinatal bereavement and post-childbirth, with specific focus upon perinatal bereavement. We identified 23 papers, which have been themed into 10 therapies. Out of the 23 papers found, only 4 focus upon perinatal bereavement (3 effective; 1 ineffective). Out of the 3 effective papers, one reports success of 4 grief-counselling sessions (Navidian et al., Citation2017) and the other two report effectiveness of CBT (Kersting et al., Citation2013, Citation2011). All of these papers are short in participant numbers and descriptions of interventions, and none address the new ICD-11 diagnosis of Complex-PTSD (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018). Since 39% of women experience either PTSD or Complex-PTSD post-perinatal bereavement (Christiansen, Citation2017; Hollins Martin et al., Citation2021), it is really important that new treatments are developed and evaluated. It will take time before an evidence-base accumulates regarding use of CFT focused treatment packages to treat PTSD or CPTSD post-perinatal bereavement, with a systematic review and meta-analysis by Karatzias et al. (Citation2017) concluding that further research is required to develop effective flexible interventions to treat CPTSD that build upon the success of prior PTSD interventions. Clearly, further research is required to assess benefits of flexibility, sequencing, and delivery of CFT informed therapy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Armstrong, D. S., Hutti, M. H., & Myers, J. (2009). The influence of prior perinatal loss on parents’ psychological distress after the birth of a subsequent healthy infant. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 38(6), 654–666. PMID: 19930279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01069.x

- Asadzadeh, L., Jafari, E., Kharaghani, R., & Taremian, F. (2020). Effectiveness of midwife-led brief counseling intervention on post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms of women experiencing a traumatic childbirth: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2826-1

- Ayers, S., McKenzie-McHarg, K., & Eagle, A. (2007). Cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder: Case studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 28(3), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820601142957

- Barrera, T. L., Mott, J. M., Hofstein, R. F., & Teng, E. J. (2013). A meta-analytic review of exposure in group cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 24–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.005

- Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., & Lewis, C. (2013). Psychological therapies for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD003388. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub4.

- Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Gusman, F. D., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490080106

- Blevins, C., Weathers, F., Davis, M., Witte, T., & Domino, J. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Burden, C., Bradley, S., Storey, C., et al. (2016). From grief, guilt pain and stigma to hope and pride: A systematic review and meta-analysis of mixed-method research of the psychosocial impact of stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0800-8

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2001). Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s Guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews, CRD Report 4 York.

- Chiorino, V., Cattaneo, M., Macchi, E., Salerno, R., Roveraro, S., Bertolucci, G., Mosca, F., Fumagalli, M., Cortinovis, I., Carletto, S., & Fernandez, I. (2019). The EMDR recent birth trauma protocol: A pilot randomised clinical trial after traumatic childbirth. Psychology & Health, 35(7), 795–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1699088

- Christiansen, D. M. (2017). Posttraumatic Stress disorder in parents following infant death: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.007

- Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Ford, J. D., Green, B. L., Alexander, P., Briere, J., Herman, J. L., Lanius, R., Stolbach, B. C., Spinazzola, J., Van der Kolk, B. A., & Van der Hart, O. (2012a). The ISTSS expert consensus treatment guidelines for Complex PTSD in adults. http://www.istss.org/ISTSS_Main/media/Documents/ISTSS-Expert-Concesnsus-Guidelinesfor-Complex-PTSD-Updated-060315.pdf

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., & Maercker, A. (2013). Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706

- Cloitre, M., Petkova, E., Wang, J., & Lu Lassell, F. (2012b). An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 709–717. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21920

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., Karatzias, T., & Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12956

- Cloitre, M., Stovall-Mcclough, K. C., Nooner, K., Zorbas, P., Cherry, S., Jackson, C. L., Gan, W., & Petkova, E. (2010). Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247

- Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

- De Jongh, A., Resick, P. A., Zoellner, L. A., van Minnen, A., Lee, C. W., Monson, C. M., Foa, E. B., et al. (2016). Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22469

- DeMier, R. L., Hynan, M. T., Hatfield, R. F., Varner, M. W., Harris, H. B., & Manniello, R. L. (2000). A measurement model of perinatal stressors: Identifying risk for postnatal emotional distress in mothers of high-risk infants. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 89–100 (SICI)1097-4679(200001)56:1<89::AID-JCLP8>3.0.CO;2-6

- Di Blasio, P., Camisasca, E., Caravita, S., Ionio, C., Milani, L., & Valtolina, G. (2015). The effects of expressive writing on postpartum depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychological Reports, 117(3), 856–882. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.13.PR0.117c29z3

- Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M. J., Beath, A. P., & Einstein, D. A. (2019). Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6

- Foa, E., Riggs, D., Dancu, C., & Rothbaum, B. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060405

- Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., Friedman, M. J., & Cohen, J. A. (2009). Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies. Guilford Press.

- Gamble, J., Creedy, D., Moyle, W., Webster, J., McAllister, M., & Dickson, P. (2005). Effectiveness of a counseling intervention after a traumatic childbirth: A randomized controlled trial. Birth, 32(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00340.x

- Grisbrook, M. A., & Letourneau, N. (2021). Improving maternal postpartum mental health screening guidelines requires assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(2), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00373-8

- Harned, M. S., Korslund, K. E., & Linehan, M. M. (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 55, 7–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.008

- Heazell, A., et al. (2021). Protocol for the development of a core outcome set for stillbirth care research (iCHOOSE Study). BMJ OPEN. (in press; accepted on 8.11.2021).

- Heazell, A. E. P., Siassakos, D., & Blencowe, H. (2016). Ending preventable stillbirths investigator group. Stillbirths: Economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet, 387, 10018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00836-3

- Herman, J. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050305

- Hollins Martin, C. J., Patterson, J., Paterson, C., Welsh, N., Dougall, N., Karatzias, T., & Williams, B. (2021). ICD-11 complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) in parents with perinatal bereavement: Implications for treatment and care. Midwifery, 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.102947

- Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41(3), 209–218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004

- Horsch, A., Tolsa, J., Gilbert, L., Du Chêne, L., Müller-Nix, C., & Graz, M. (2016). Improving maternal mental health following preterm birth using an expressive writing intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(5), 780–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0611-6

- Horsch, A., Vial, Y., Favrod, C., Harari, M., Blackwell, S., Watson, P., Iyadurai, L., Bonsall, M., & Holmes, E. (2017). Reducing intrusive traumatic memories after emergency caesarean section: A proof-of-principle randomized controlled study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 94, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.03.018

- Huberty, J., Sullivan, M., Green, J., Kurka, J., Leiferman, J., Gold, K., & Cacciatore, J. (2020). Online yoga to reduce post-traumatic stress in women who have experienced stillbirth: A randomized control feasibility trial. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-02926-3

- Karatzias, T., Murphy, P., Cloitre, M., Bisson, J., Roberts, N., Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Maercker, A., Ben-Ezra, M., Coventry, P., Mason-Robersts, S., Bradley, A., & Hutton, P. (2019). Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(11), 1761–1775. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000436

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., Roberts, N., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., & Cloitre, M. (2017). Evidence of distinct profiles of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 207, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.032

- Kersting, A., Dölemeyer, R., Steinig, J., Walter, F., Kroker, K., Baust, K., & Wagner, B. (2013). Brief internet-based intervention reduces Posttraumatic Stress and Prolonged Grief in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(6), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348713

- Kersting, A., Kroker, K., Schlicht, S., Baust, K., & Wagner, B. (2011). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral internet-based therapy in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: Pilot data from a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 14(6), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0240-4

- Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behaviour Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

- Lawn, J. E., Blencowe, H., Oza, S., You, D., Lee, A. C., Waiswa, P., Lalli, M., Bhutta, Z., Barros, A. J., Christian, P., Mathers, C., & Cousens, S. N. (2014). Every newborn: Progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. The Lancet, 384(9938), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-7

- Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927–945. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002141

- Lennard, G., Mitchell, A., & Whittingham, K. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of a brief online self‐compassion intervention for mothers of infants: Effects on mental health outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23068

- Maercker, A., & Schützwohl, M. (1998). Erfassung von psychischen Belastungsfolgen: Die Impact of Event Skala-revidierte Version. Diagnostica, 44, 130–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/t55092-000

- Mays, N., Roberts, E., & Popay, J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods (pp. 188–220). Routledge.

- Meades, R., Pond, C., Ayers, S., & Warren, F. (2011). Postnatal debriefing: Have we thrown the baby out with the bath water? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(5), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.002

- Mills, K. L., Teesson, M., Back, S. E., Brady, K. T., Baker, A. L., Hopwood, S., Sannibale, C., Barrett, E. L., Merz, S., Rosenfeld, J., & Ewer, P. L. (2012). Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 308(7), 690–699. PMID: 22893166. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.9071

- Mitchell, A., Whittingham, K., Steindl, S., & Kirby, J. (2018). Feasibility and acceptability of a brief online self-compassion intervention for mothers of infants. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(5), 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0829-y

- Navidian, A., Saravani, Z., Shakiba, M. (2017). Impact of psychological grief counseling on the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms in mothers after stillbirths. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(8), 650–654. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.napier.ac.uk/doi/full/10.1080/01612840.2017.1315623=></https

- Nieminen, K., Berg, I., Frankenstein, K., Viita, L., Larsson, K., Persson, U., Spånberger, L., Wretman, A., Silfvernagel, K., Andersson, G., & Wijma, K. (2016). Internet-provided cognitive behaviour therapy of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth-a randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(4), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1169626

- Priest, S., Henderson, J., Evans, S., & Hagan, R. (2003). Stress debriefing after childbirth: A randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia, 178(11), 542–545. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05355.x

- Reina, S., Freund, B., & Ironson, G. (2019). The use of prolonged exposure therapy augmented with CBT to treat postpartum trauma. Clinical Case Studies, 18(4), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650119834646

- Roberts, N. P., Roberts, P. A., Jones, N., & Bisson, J. I. (2015). Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.007

- Ryding, E., Wiren, E., Johansson, G., Ceder, B., & Dahlstrom, A. (2004). Group counseling for mothers after emergency cesarean section: A randomized controlled trial of intervention. Birth, 31(4), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00316.x

- Sandström, M., Wiberg, B., Wikman, M., Willman, A., & Högberg, U. (2008). A pilot study of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing treatment (EMDR) for post-traumatic stress after childbirth. Midwifery, 24(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.07.008

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl. 20), 22–33.

- Slade, P., West, H., Thomson, G., Lane, S., Spiby, H., Edwards, R., Charles, J., Garrett, C., Flanagan, B., Treadwell, M., Hayden, E., & Weeks, A. (2020). STRAWB2 (Stress and Wellbeing After Childbirth): A randomised controlled trial of targeted self‐help materials to prevent post‐traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 127(7), 886–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16163

- Sorenson, D. (2003). Healing traumatizing provider interactions among women through short-term group therapy. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 17(6), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.apnu.2003.10.002

- Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (Sands), UK. (2018). https://www.sands.org.uk/about-sands/our-work/our-research

- Stramrood, C., van der Velde, J., Doornbos, B., Marieke Paarlberg, K., Weijmar Schultz, W., & van Pampus, M. (2011). The patient observer: Eye-Movement desensitization and reprocessing for the treatment of posttraumatic stress following childbirth. Birth, 39(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00517.x

- Sun, S., Li, J., Ma, Y., Bu, H., Luo, Q., & Yu, X. (2017). Effects of a family-support programme for pregnant women with foetal abnormalities requiring pregnancy termination: A randomized controlled trial in China. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12614

- Taft, C. T., Watkins, L. E., Stafford, J., Street, A. E., & Monson, C. M. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 22–33. PMID: 21261431. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022196

- Watts, B. V., Schnurr, P. P., Mayo, L., Young-Xu, Y., Weeks, W. B., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 541–550. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r08225

- Weiss, D., & Marmar, C. (1997). The impact of event scale–revised. In J. Wilson & T. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399–411). USA Guildford Press.

- Wijma, K., Söderquist, J., & Wijma, B. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: A cross sectional study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 11(6), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00041-8

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Maternal and perinatal health. www.who.int

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). ICD-11-Mortality and morbidity statistics. Icd.who.int. [Retrieved April 2, 2021, from <https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/585833559>