ABSTRACT

Background

Pregnancy and anticipation of the birth of the first child is considered a happy and exciting time. However, the stress involved in pregnancy has been found to put women at greater risk of impaired psychological well-being, or higher distress. Confusion in the theoretical literature between the terms ‘stress’ and ‘distress’ makes it difficult to understand the underlying mechanism that may enhance or reduce psychological well-being. We suggest that maintaining this theoretical distinction and examining stress from different sources, may allow us to gain new knowledge regarding the psychological well-being of pregnant women.

Objective

Drawing on the Calming Cycle Theory, to examine a moderated mediation model for the explanation of the dynamic between two stress factors (COVID−19-related anxiety and pregnancy stress) that may pose a risk to psychological well-being, as well as the protective role of maternal-fetal bonding.

Methods

The sample consisted of 1,378 pregnant women who were expecting their first child, recruited through social media and completed self-report questionnaires.

Results

The higher the COVID−19-related anxiety, the higher the pregnancy stress, which, in turn, was associated with lower psychological well-being. However, this effect was weaker among women who reported greater maternal-fetal bonding.

Conclusion

The study expands knowledge of the dynamic between stress factors and psychological well-being during pregnancy, and sheds light on the unexplored role of maternal-fetal bonding as a protective factor against stress.

Introduction

Pregnancy and anticipation of the birth of a first child is considered an exciting time for women. However, it has also been shown to be a sensitive period during which women may be at risk of lower psychological well-being (Arnal-Remón et al., Citation2015). Psychological well-being is a broad concept which will be referred in this study as reflecting a positive mental health state, or lower psychological distress (Veit & Ware, Citation1983).

Over the years, many studies have sought to identify the factors that reduce or promote well-being among pregnant women (Agostini et al., Citation2015; Fisher et al., Citation2013; McNamara et al., Citation2019; Verreault et al., Citation2014). This study seeks to further empirical and theoretical understanding of the mechanism that may pose a risk to the psychological well-being of women expecting their first child by clarifying the conceptual distinction between the terms ‘stress’ and ‘distress’, which is regarded as lower psychological well-being (Veit & Ware, Citation1983), and examining the dynamic between them. Furthermore, we suggest that the Calming Cycle Theory can be used as a theoretical framework for investigating the role of a rarely explored protective factor against stress during pregnancy: maternal-fetal bonding.

Stress during pregnancy

The experience of stress is associated with lower psychological well-being, or higher distress (Agostini et al., Citation2015; Fisher et al., Citation2013; Husain et al., Citation2012; Verreault et al., Citation2014). However, there seems to be conceptual confusion, both in daily use and in the scientific literature, between the terms ‘stress’ and ‘distress’, which are often used interchangeably (NRC, Citation2008; Wheaton & Montazer, Citation2009). According to Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), stress is generated when the demands from the environment exceed one’s resources, thus stress is the cause. Distress, on the other hand, refers to the negative consequences of stress, which appear when adaptation and coping strategies fail to return the organism to homoeostasis (NRC, Citation2008). In the perinatal literature, stress is regarded as feelings of worry, concern, and mild anxiety; distress is regarded as lower psychological well-being, sometimes reflected in the form of mental health disorders (Emmanuel & St John, Citation2010; Veit & Ware, Citation1983).

As most studies use the terms ‘stress’ and ‘distress’ interchangeably (e.g. Ibrahim & Lobel, Citation2020; Yali & Lobel, Citation1999), they are unable to explain the underlying mechanism that may affect psychological well-being. In this study we attempt to offer such an explanation by maintaining the distinction between the two terms and suggesting a moderated mediation model that may help in understanding the dynamic between two stress factors (COVID−19-related anxiety and pregnancy stress) and psychological well-being during pregnancy, as well as the protective role of maternal-fetal bonding in these associations.

In recent years, the COVID−19 pandemic has constituted a major source of stress for pregnant women, and particularly those expecting their first child. Although the level of threat has varied over the course of the pandemic, it still poses an ongoing risk to the mental health of pregnant women, who are considered a vulnerable population. Studies indicate higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms among women throughout pregnancy and after childbirth during the pandemic than prior to it (Ceulemans et al., Citation2020; Davenport et al., Citation2020; Hessami et al., Citation2020). A study conducted in Israel revealed that pregnant women experienced high levels of COVID−19-related anxiety, including concerns about being in public places, going to pregnancy check-ups, using public transportation, the health of the fetus and other family members, being infected themselves, and delivering during the pandemic. This anxiety was associated with lower psychological well-being (Taubman – Ben-Ari et al., Citation2020). In addition, concerns related to the COVID−19 pandemic were found to be associated with higher pregnancy stress (Awad Sirhan et al., Citation2022; Garcia-Silva et al., Citation2021).

Pregnancy stress is the experience of stress stemming from the pregnancy itself (Ibrahim & Lobel, Citation2020), and includes concerns regarding the physical symptoms of pregnancy, bodily changes, changes in interpersonal relationships, the health of the fetus or mother, the upcoming childbirth, or caring for the future baby (Alderdice et al., Citation2012; Ibrahim & Lobel, Citation2020). Moreover, women expecting their first child find it harder to cope with pregnancy stress due to their lack of experience (Lobel & Dunkel Schetter, Citation2016). Pregnancy stress has been associated with higher fetal movements (DiPietro et al., Citation2002), earlier childbirth (Roesch et al., Citation2004), and lower psychological well-being of the expectant mother, expressed in more symptoms of depression and anxiety disorder (Caparros-Gonzalez et al., Citation2019; Ibrahim & Lobel, Citation2020; Omidvar et al., Citation2018).

As it is evident that COVID−19-related anxiety is associated with higher pregnancy stress, and that higher pregnancy stress is associated with lower psychological well-being, we sought to examine the indirect effect of COVID−19-related anxiety on psychological well-being through the mediation of pregnancy stress. We predicted that the potential dynamic between the two stress factors would contribute to distress, that is, lower psychological well-being. In addition, based on the Calming Cycle Theory, we believed that maternal-fetal bonding might serve a protective function that would moderate this indirect effect.

Maternal-fetal bonding and the calming cycle theory

Being connected is the core of human need, playing a vital role in human growth and thriving, and providing a sense of meaning, worth, and well-being (Feeney & Collins, Citation2015; Jordan, Citation2004). Maternal-fetal bonding is the perceived emotional-psychological bond the mother forms with her unborn baby (Condon & Corkindale, Citation1997). Although sometimes referred to in the scientific literature as maternal attachment (Condon & Corkindale, Citation1997), it does not relate to Bowlby’s attachment theory, which deals with the care-seeking of the child and the caregiving of the mother in response to the infant’s needs. Rather, it relates solely to the mother’s perception of caregiving (McNamara et al., Citation2019), which has been found to increase in intensity and quality throughout pregnancy (Rossen et al., Citation2017).

The Calming cycle Theory is an extension of the Polyvagal Theory, which describes how the autonomic states of the mother and infant can be measured to determine the dyad’s relational health (Bergman et al., Citation2019; Porges, Citation2007). According to the Calming Cycle Theory, Pavlovian co-conditioning (autonomic learning) between the mother and her fetus during pregnancy and after childbirth promotes emotional connection and co-regulation of the mother and infant, which leads to better social and emotional functioning of both of them (Hane et al., Citation2019; Welch et al., Citation2020; Welch, Citation2016). Clinical trials based on this theory, show that interventions to strengthen the emotional connection between the mother and her infant led to upregulation of oxytocin levels, lower heart rate (Ludwig et al., Citation2021; Welch & Ludwig, Citation2017), higher respiratory sinus arrhythmia – an index of parasympathetic regulation (Porges et al., Citation2019; Welch et al., Citation2020), decreased symptoms of depression and anxiety among mothers (Welch et al., Citation2016), and lower child behavioural problems over time (Frosch et al., Citation2019).

Other studies have demonstrated the direct association between maternal-fetal bonding and a variety of positive effects both during pregnancy and postpartum. First, it has been related to the quality of the mother-infant relationship, with mothers who report higher maternal bonding during pregnancy showing higher maternal involvement and bonding with the baby postpartum (Petri et al., Citation2017; Rossen et al., Citation2016; Siddiqui & Hägglöf, Citation2000). Moreover, it has been associated with health practices during pregnancy, including nutrition, exercise, and prenatal care (Cannella et al., Citation2018), as well as with neonatal outcomes, such as gestational age, birth weight, and early childhood developmental outcomes (Alhusen et al., Citation2012, Citation2013). Finally, it has been related to maternal well-being, with studies showing that the better a mother’s bonding with her fetus, the fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression she reports during pregnancy and postpartum (Goecke et al., Citation2012; Matthies et al., Citation2020; Petri et al., Citation2017).

However, maternal-fetal bonding has rarely been examined as a protective factor with the potential to moderate the negative consequences of stress. In one study that may provide an indication of this role, closer bonding was found to moderate the association between maternal vulnerability and postpartum depression, with women who were more self-critical reporting fewer symptoms of depression the more attached they were to the fetus (Priel & Besser, Citation1999).

The present study

The present study sought to shed light on the dynamic between two stress factors that may contribute to higher distress, i.e. pose a risk to the psychological well-being of women pregnant with their first child, and the protective role of maternal-fetal bonding. We therefore examined a moderated mediation model in which we hypothesised that higher COVID−19-related anxiety would contribute to higher pregnancy stress, which, in turn, would be associated with lower psychological well-being. In addition, based on the Calming Cycle Theory, we hypothesised that the woman’s bonding with her fetus would moderate the association between pregnancy stress and psychological well-being and the indirect effect of COVID−19-related anxiety. The conceptual model is presented in .

Figure 1. Basic Schematic Moderated Mediation Model for Psychological Well-Being by COVID−19-related Anxiety, Pregnancy Stress and Maternal-Fetal Bonding.

Method

Participants and procedure

After receiving approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, a request for participants in the study was posted on social media sites in October-November, 2021. Participants were considered eligible for the study if they were pregnant and expecting their first baby. Participants were excluded from the study if they were under 18 years old and could not complete questionnaires in Hebrew. The opening page ensured confidentiality, and the women were informed that they could cease to participate at any stage should they wish to do so. In addition, they were told that they could call or email the researchers, whose contact details were provided, should they feel any distress during or after completing the questionnaire.

The final sample consisted of 1378 women aged 18–45 (M = 28.68, SD = 4.56) with a gestational age of 4–41 weeks (M = 25.57, SD = 9.00). The large majority of participants were pregnant with a single baby (97.8%) and had no history of miscarriages (80.3%). Around a fifth (20.4%) indicated an at-risk pregnancy. Most of the participants were Jewish (91.7%), with the others being Muslim, Christian, Druse, or not indicating a religion. Most were married or cohabiting with a partner (90.6%), with the rest being single, engaged, separated, or divorced, and had an academic degree (66.8%). The majority reported their economic status as average or good (87.1%), rather than poor or very good, and their physical health as good or very good (91.8%).

Instruments

The Mental Health Inventory-Short Form (MHI−5; Stewart et al., Citation1988)

was used to assess psychological well-being. Derived from the original MHI (Veit & Ware, Citation1983), the scale is comprised of 5 items relating to the participant’s well-being (e.g. ‘I felt happy’) and distress (e.g. ‘I felt sad and upset’) during the past month. Responses were indicated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (all the time). A score was calculated by averaging the responses to all 5 items, with higher scores reflecting greater psychological well-being. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

COVID−19-Related Anxieties

(Taubman – Ben-Ari et al., Citation2020), a scale examining women’s concerns during pregnancy associated with the pandemic, was used to obtain a global measure of this stress factor. The participants were asked how anxious they felt about: being infected by COVID−19; a family member being infected by COVID−19; being in public places; using public transportation; visiting hospitals or community clinics for pregnancy check-ups; the health of their fetus; the delivery; and raising the baby. Responses were marked on a scale from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating a higher level of the given anxiety. Whereas previous studies, have related to each item separately, for the purposes of the current study, we calculated a total score by averaging the responses to all items. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal component with varimax rotation in order to identify the factor structure of the questionnaire. The results are presented in . The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .88, above the commonly recommended value of .6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 (28) = 6647.42, p < .001). Using eigenvalues > 1 to determine the underlying components, the analysis yielded one factor explaining a total of 59.75% of the variance in the data, thereby validating the use of a single score of global COVID−19-related anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Table 1. Factor Loadings of the COVID − 19-Related Anxieties.

The Prenatal Distress Questionnaire

(PDQ; Yali & Lobel, Citation1999), was used to assess pregnancy stress. Although entitled ‘prenatal distress’, the authors of the questionnaire conceptualised it in a later work as actually measuring pregnancy stress (Ibrahim & Lobel, Citation2020). The 12-item questionnaire asks participants to rate their feelings about different aspects of pregnancy (e.g. ‘I find weight gain during pregnancy troubling’) on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). A total score was calculated for each participant by summing up her responses to all items, with a higher score reflecting higher pregnancy-specific stress. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80.

The Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale

(MAAS; Condon, Citation1993), a 19-item scale, was used to measure the psychological bond expectant mothers develop with their fetus. In the present study, the item regarding miscarriage was omitted, since we believed it might trigger extreme sadness for women with a history of pregnancy loss or abortion. Participants were asked do indicate how they feel about each item on a 5-point scale with options suitable to each item (e.g. ‘Over the past two weeks my feelings about the baby inside me have been … ’ very positive/mainly positive/mixed positive and negative/mainly negative/very negative). A global score was calculated by summing up the responses, with a higher score indicating a higher level of maternal-fetal bonding. In the original study, Cronbach’s alpha was .82 (Condon, Citation1993). In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .77.

A sociodemographic questionnaire

Was used to tap the woman’s background characteristics: age (continuous); education (1=elementary, 2=high school, 3=professional certification, 4=BA degree, 5=MA degree or higher); family status (1=single, 2=married, 3=cohabiting with a partner, 4=separated, 5=divorced, 6=widowed, 7=engaged); financial status (1=poor, 2=average; 3=good, 4=very good); physical health (1=very poor; 2=poor; 3=average, 4=good, 5=very good). In addition, the questionnaire tapped information regarding the pregnancy, including: history of miscarriages (1=no, 2=yes); gestational age (continuous); number of fetuses (continuous); and pregnancy complications or at-risk pregnancy (1=no, 2=yes).

Data analysis

The adequacy of the sample size was confirmed through G*power analysis (Faul et al., Citation2009). For a small effect size (f2= .02) and a significance of α = .05, the G*power analysis indicated 863 to be the minimum appropriate sample size. Therefore, the sample size in the current study (1378 participants) is satisfactory for analysis.

The analysis was conducted in two stages. First, descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and partial correlations were computed for the study variables while controlling for pregnancy trimester and history of miscarriages. Next, to examine the conditional effect of maternal-fetal bonding on the relationship between COVID−19-related anxiety and psychological well-being via pregnancy stress, we performed a moderated mediation analysis, controlling for pregnancy trimester, history of miscarriages, age, education, economic status, and health using the PROCESS macro, model 14, in SPSS (Hayes, Citation2015). As a criterion of statistical significance, we used the 95% confidence interval (CI) generated by the bias-corrected bootstrap method set to 10,000 reiterations. Significant effects are supported by the absence of zero within the confidence interval.

Results

Descriptive data and correlations of the study variables

The means, SD’s and partial correlations of all study variables are presented in . The results indicate that psychological well-being was significantly and positively associated with age, education, economic status, physical health, and maternal-fetal bonding, so that women who were older, more educated, had a higher economic status, and bonded more strongly with the fetus reported higher psychological well-being. In contrast, COVID−19-related anxiety and pregnancy stress were significantly and negatively associated with psychological well-being, with women experiencing higher COVID−19-related anxiety and pregnancy stress reporting lower psychological well-being. There was no multicollinearity between these three variables, reinforcing the theoretical distinction in the scientific literature.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations of the Study Variables.

Test of conditional indirect effect: moderated mediation

The results of the moderated mediation analysis are presented in . As can be seen from the table, paths a and b were significant, thereby meeting the requirement for mediation. More specifically, as predicted, the higher the woman’s COVID−19-related anxiety, the more she tended to experience pregnancy stress, which, in turn, was associated with lower psychological well-being.

Table 3. Moderated Mediation Analysis for Psychological Well-Being by COVID − 19-related Anxiety, Pregnancy Stress and Maternal-Fetal Bonding.

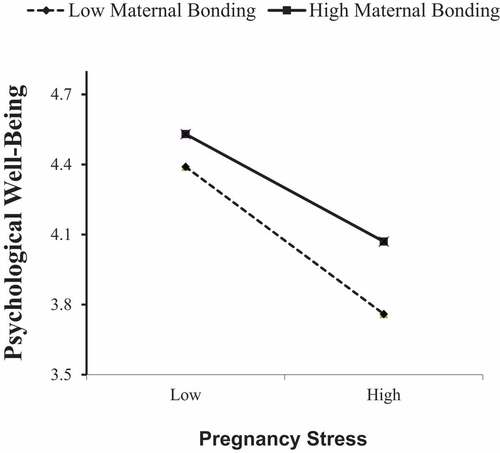

Maternal-fetal bonding was found to moderate the effect of pregnancy stress on psychological well-being (i.e. conditional effects on path b; b = .006, SE = .00, t = 2.33, p = .01). Tests of simple slopes found a significant stronger negative association between pregnancy stress and psychological well-being for those low on maternal-fetal bonding (1 SD below the mean of maternal bonding; b= −.03, SE = .00, t= −11.90, p < .001), and a significant weaker negative association between pregnancy stress and psychological well-being among those high on maternal-fetal bonding (1 SD above the mean; b= −.02, SE = .00, t= −9.48, p < .001). The results of this analysis appear in .

Figure 2. Interactive Effect of Pregnancy Stress and Maternal-Fetal Bonding on Psychological Well-being.

Given the support found for the moderating effect of maternal-fetal bonding, we tested for moderated mediation. The conditional indirect effect was significant and reached its highest levels among those low on maternal-fetal bonding (1 SD below the mean; b= −.07, 95% CI [−.090, −.048]). In contrast, when maternal bonding was high (1 SD above the mean), the effect was weaker (b= −.05, 95% CI [−.071, −.034]). The overall moderated mediation model was supported by the index of moderated mediation (b = .001, 95% CI [.001; .002]), as the fact that zero is not within the CI indicates that maternal bonding has a significant moderating effect on the indirect effect (Hayes, Citation2015).

Discussion

This study sought to gain a better understanding of a mechanism that may affect the psychological well-being of women expecting their first child by employing a theoretical distinction between stress and distress and examining the dynamic between COVID−19-related anxiety, pregnancy stress, and psychological well-being. Furthermore, we drew on the Calming Cycle Theory to explore the potential protective role of maternal-fetal bonding, testing a moderated mediation model.

Since distress is conceptualised in the scientific literature as the negative consequence of stress (NRC, Citation2008), we treated stress as the independent variable and distress (lower psychological well-being) as the dependent variable and tested for a complex model to explain the association between them. The results reveal that anxiety related to the COVID−19 pandemic was associated with another type of stress, i.e. that aroused by the pregnancy itself, which in turn, was related to lower psychological well-being (in other words, higher distress), among women pregnant with their first child. The model we proposed here gives credence to the idea that stress factors and distress should be maintained as separate concepts (NRC, Citation2008; Wheaton & Montazer, Citation2009), and that examining stress from different sources may provide additional information concerning the underlying dynamic of the association between them.

The study also shows that the negative association between pregnancy stress and psychological well-being is weaker among women who have stronger bond with their fetus. In other words, the emotional connection the mother feels towards her unborn child appears to serve a protective function against the potential consequence of experiencing greater stress. These findings are highly important, since they shed light on a significant and underexplored factor that may assist pregnant women experiencing high levels of stress. The findings are in line with studies reporting that maternal-fetal bonding is associated with various positive health behaviours, such as better nutrition, exercise, and prenatal care (Cannella et al., Citation2018), which may contribute indirectly to the reduction of psychological distress in demanding times. The findings of this study also validate the Calming Cycle Theory. Whereas most theories dealing with mother-infant bonding, such as Bowlby’s attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1988), focus on how the emotional connection with the baby help them to get comfort and regulate emotions, the Calming Cycle Theory proposes that this relationship may also have a calming effect on the mother (Welch et al., Citation2020).

In an attempt to explain the underlying mechanism which enables the cycle described above, we may employ another theory that concentrates on positive emotions, namely the Broaden and Build Theory (Fredrickson, Citation2004, Citation2013). According to this theory, positive emotions can ‘undo’ the effect of negative emotions or stress and can thus be helpful when coping with negative experiences. In addition, they serve to increase resilience by broadening the individual’s awareness and allowing them to discover new perceptions, actions, and relationships. Consequently, they aid in building resources, such as new skills, knowledge, and social support, that may promote survival and well-being in the face of threat. Combining the two theories together, it may be that higher maternal-fetal bonding reflects higher levels of love, joy, serenity, awe and other positive emotions, and these positive emotions assist in preventing or at least moderating the negative effect of stress and aid building additional resources that contribute to the well-being of the mothers. Having said that, the Calming cycle theory is limited to explain only the protective role of maternal-fetal bonding against stress in general and not the moderated mediation model we presented as a whole, which include stress from specific sources. This could be addressed in future studies.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, it relied solely on self-reports. Consequently, the responses may suffer from a bias deriving from low self-awareness or social desirability. Secondly, the sample is not representative, but rather a convenience sample recruited through social media, and therefore certain segments of the population may be unrepresented or underrepresented. Nevertheless, this method of recruitment has become common practice in recent years (Hewson et al., Citation2016). Finally, this is a cross-sectional study which was conducted at a single point in time, and therefore causality cannot be inferred. Future studies might consider adopting a longitudinal design and examine post-natal outcomes as well. It would also be of value to investigate the effect on pregnant women’s well-being of additional variables, such as other stress factors, internal resources, or the spousal relationship.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes to the existing literature by exploring issues rarely previously investigated. First, it expands knowledge of the dynamic between stress factors and psychological distress during pregnancy by maintaining a theoretical distinction between the two concepts. The findings of this study may thus help professionals who meet with pregnant women to be aware that women who are exposed to large-scale stressful events or a pandemic are more prone to experience stress with regard to their pregnancy and lower well-being. Therefore, they will be able to offer a more suitable and holistic treatment in order to promote their well-being. Secondly, the study suggests that maternal-fetal bonding may play a protective role against stress among women pregnant with their first child, an insight that has both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically speaking, the idea that the bonding with the fetus may have protective qualities for women, offers a new perspective on the mother-infant dyad- that is most commonly seen as contributing solely to the well-being of the baby. In practice, creating interventions aimed at strengthening the mother’s emotional bond with her fetus, among many other benefits, may help mothers themselves be more resilient to stress and promote their well-being during the sensitive period of pregnancy.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agostini, F., Neri, E., Salvatori, P., Dellabartola, S., Bozicevic, L., & Monti, F. (2015). Antenatal depressive symptoms associated with specific life events and sources of social support among Italian women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(5), 1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1613-x

- Alderdice, F., Lynn, F., & Lobel, M. (2012). A review and psychometric evaluation of pregnancy-specific stress measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33(2), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2012.673040

- Alhusen, J. L., Gross, D., Hayat, M. J., Woods, A. B., & Sharps, P. W. (2012). The influence of maternal–fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low- income, urban women. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21464

- Alhusen, J. L., Hayat, M. J., & Gross, D. (2013). A longitudinal study of maternal attachment and infant developmental outcomes. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(6), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0357-8

- Arnal-Remón, B., Moreno-Rosset, C., Ramírez-Uclés, I., & Antequera-Jurado, R. (2015). Assessing depression, anxiety and couple psychological well-being in pregnancy: A preliminary study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(2), 128–139.. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.986648

- Awad Sirhan, N., Simó-Teufel, S., Molina-Muñoz, Y., Cajiao-Nieto, J., & Izquierdo-Puchol, M. T. (2022). Factors associated with prenatal stress and anxiety in pregnant women during COVID-19 in Spain. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition), 32, S5–S13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcle.2021.10.003

- Bergman, N. J., Ludwig, R. J., Westrup, B., & Welch, M. G. (2019). Nurturescience versus neuroscience: A case for rethinking perinatal mother–infant behaviors and relationship. Birth Defects Research, 111(15), 1110–1127.. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.1529

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

- Cannella, B. L., Yarcheski, A., & Mahon, N. E. (2018). Meta-analyses of predictors of health practices in pregnant women. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(3), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916682212

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A., Perra, O., Alderdice, F., Lynn, F., Lobel, M., Garcı´a-Garcı´a, I., & Peralta-Ramı´rez, M. I. (2019). Psycho- metric validation of the prenatal distress questionnaire (PDQ) in pregnant women in Spain. Women & Health, 59(8), 937–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1584143

- Ceulemans, M., Hompes, T., & Foulon, V. (2020). Mental health status of pregnant and breastfeeding women during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A call for action. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 151(1), 146–147.. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13295

- Condon, J. T. (1993). The assessment of antenatal emotional attachment: Development of a questionnaire instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 66(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01739.x

- Condon, J. T., & Corkindale, C. (1997). The correlates of antenatal attachment in pregnant women. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 70(4), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01912.x

- Davenport, M. H., Meyer, S., Meah, V. L., Strynadka, M. C., & Khurana, R. (2020). Moms are not ok: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 1, 1.. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001

- DiPietro, J. A., Hilton, S. C., Hawkins, M., Costigan, K. A., & Pressman, E. K. (2002). Maternal stress and affect influence fetal neurobehavioral development. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 659–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.659

- Emmanuel, E., & St John, W. (2010). Maternal distress: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(9), 2104–2115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05371.x

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Feeney, B. C., & Collins, N. L. (2015). A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(2), 113–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222

- Fisher, J., Tran, T., Duc Tran, T., Dwyer, T., Nguyen, T., Casey, G. J., Simpson, J. A., Hanieh, S., & Biggs, B. A. (2013). Prevalence and risk factors for symptoms of common mental disorders in early and late pregnancy in Vietnamese women: A prospective population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 146(2), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.007

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. In F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 217–238). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567523.003.0008

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In Eds. Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47. pp. 1–53). Academic Press.. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

- Frosch, C. A., Fagan, M. A., Lopez, M. A., Middlemiss, W., Chang, M., Hane, A. A., & Welch, M. G. (2019). Validation study showed that ratings on the welch emotional connection screen at infant age six months are associated with child behavioural problems at age three years. Acta Paediatrica, 108(5), 889–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14731

- Garcia-Silva, J., Caracuel, A., Lozano-Ruiz, A., Alderdice, F., Lobel, M., Perra, O., & Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A. (2021). Pandemic-related pregnancy stress among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Midwifery, 103, 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103163.

- Goecke, T. W., Voigt, F., Faschingbauer, F., Spangler, G., Beckmann, M. W., & Beetz, A. (2012). The association of prenatal attachment and perinatal factors with pre-and postpartum depression in first-time mothers. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 286(2), 309–316.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2286-6

- Hane, A. A., LaCoursiere, J. N., Mitsuyama, M., Wieman, S., Ludwig, R. J., Kwon, K. Y., Browne, J. V., Austin, J., Myers, M. M., & Welch, M. G. (2019). The welch emotional connection screen: Validation of a brief mother–infant relational health screen. Acta Paediatrica, 108(4), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14483

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hessami, K., Romanelli, C., Chiurazzi, M., & Cozzolino, M. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 35(20), 1–8.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155

- Hewson, C., Vogel, C., & Laurent, D. (2016). Internet research methods. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473920804

- Husain, N., Cruickshank, K., Husain, M., Khan, S., Tomenson, B., & Rahman, A. (2012). Social stress and depression during pregnancy and in the postnatal period in British Pakistani mothers: A cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(3), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.009

- Ibrahim, S. M., & Lobel, M. (2020). Conceptualization, measurement, and effects of pregnancy-specific stress: Review of research using the original and revised prenatal distress questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 16–33.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00068-7

- Jordan, J. V. (2004). Relational awareness: Transforming disconnection. In J. V. Jordan, M. Walker, & L. M. Hartling (Eds.), The complexity of connection: Writings from the stone center’s Jean Baker Miller training institute (pp. 47–63). The Guilford Press.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer.

- Lobel, M., & Dunkel Schetter, C. (2016). Pregnancy and prenatal stress. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 318–329). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00164-6

- Ludwig, R. J., Grunau, R. E., Chafkin, J. E., Hane, A. A., Isler, J. R., Chau, C. M. Y., Welch, M. G., & Myers, M. (2021). Preterm infant heart rate is lowered after family nurture intervention in the NICU: Evidence in sup- port of autonomic conditioning. Early Human Development, 161, 105455. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARLHUMDEV.2021.105455

- Matthies, L. M., Müller, M., Doster, A., Sohn, C., Wallwiener, M., Reck, C., & Wallwiener, S. (2020). Maternal–fetal attachment protects against postpartum anxiety: The mediating role of postpartum bonding and partnership satisfaction. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 301(1), 107–117.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05402-7

- McNamara, J., Townsend, M. L., Herbert, J. S., & Hill, B. (2019). A systemic review of maternal wellbeing and its relationship with maternal fetal attachment and early postpartum bonding. PLos One, 14(7), e0220032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220032

- National Research Council Committee on Recognition and Alleviation of Distress in Laboratory Animals. (2008). Recognition and alleviation of distress in laboratory animals. National Academies Press.

- Omidvar, S., Faramarzi, M., Hajian-Tilaki, K., Amiri, F. N., & Rohrmann, S. Associations of psychosocial factors with pregnancy healthy life styles. (2018). PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0191723. Article e0191723. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191723

- Petri, E., Palagini, L., Bacci, O., Borri, C., Teristi, V., Corezzi, C., Faraoni, S., Antonelli, P., Cargioli, C., Banti, S., Perugi, G., & Mauri, M. (2017). Maternal–foetal attachment independently predicts the quality of maternal–infant bonding and post-partum psychopathology. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 31(23), 3153–3159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1365130

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

- Porges, S. W., Davila, M. I., Lewis, G. F., Kolacz, J., Okonmah‐Obazee, S., Hane, A. A., Kwon, K. Y., Ludwig, R. J., Myers, M. M., & Welch, M. G. (2019). Autonomic regulation of preterm infants is enhanced by family nurture intervention. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(6), 942–952. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21841

- Priel, B., & Besser, A. (1999). Vulnerability to postpartum depressive symptomatology: Dependency, self-criticism and the moderating role of antenatal attachment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1999.18.2.240

- Roesch, S. C., Schetter, C. D., Woo, G., & Hobel, C. J. (2004). Modeling the types and timing of stress in pregnancy. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 17(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061580031000123667

- Rossen, L., Hutchinson, D., Wilson, J., Burns, L., Allsop, S., Elliott, E. J., Jacobs, S., Macdonald, J. A., Olsson, C., & Mattick, R. P. (2017). Maternal bonding through pregnancy and postnatal: Findings from an Australian longitudinal study. American Journal of Perinatology, 34(8), 808–817. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1599052

- Rossen, L., Hutchinson, D., Wilson, J., Burns, L., Olsson, C., Allsop, S., Elliott, E., Jacobs, S., Macdonald, J. A., & Mattick, R. P. (2016). Predictors of postnatal mother-infant bonding: The role of antenatal bonding, maternal substance use and mental health. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(4), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0602-z

- Siddiqui, A., & Hägglöf, B. (2000). Does maternal prenatal attachment predict postnatal mother–infant interaction? Early Human Development, 59(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-37820000076-1

- Stewart, A. L., Hays, R. D., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (1988). The MOS short-form general health survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care, 26(7), 724–736. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O., Chasson, M., Abu Sharkia, S., & Weiss, E. (2020). Distress and anxiety associated with COVID-19 among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 38(3), 340–348.. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2020.1786037

- Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(5), 730–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730

- Verreault, N., Da Costa, D., Marchand, A., Ireland, K., Dritsa, M., & Khalife, S. (2014). Rates and risk factors associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and with postpartum onset. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 35(3), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2014.947953

- Welch, M. G. (2016). Calming cycle theory: The role of visceral/autonomic learning in early mother and infant/child behaviour and development. Acta Paediatrica, 105(11), 1266–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13547

- Welch, M. G., Barone, J. L., Porges, S. W., Hane, A. A., Kwon, K. Y., Ludwig, R. J., Stark, R. I., Surman, A. L., Kolacz, J., Myers, M. M., & Lavoie, P. M. (2020). Family nurture intervention in the NICU increases autonomic regulation in mothers and children at 4-5 years of age: Follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 15(8), e0236930. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236930

- Welch, M. G., Halperin, M. S., Austin, J., Stark, R. I., Hofer, M. A., Hane, A. A., & Myers, M. M. (2016). Depression and anxiety symptoms of mothers of preterm infants are decreased at 4 months corrected age with Family Nurture Intervention in the NICU. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0502-7

- Welch, M. G., & Ludwig, R. J. (2017). Calming cycle theory and the co-regulation of oxytocin. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 45(4), 519–594. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2017.45.4.519

- Wheaton, B., & Montazer, S. (2009). Stressors, stress, and distress. In T. L. Scheid & T. N. Brown (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems (2nd ed., pp. 171–199). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511984945.013

- Yali, A. M., & Lobel, M. (1999). Coping and distress in pregnancy: An investigation of medically high risk women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 20(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829909075575