ABSTRACT

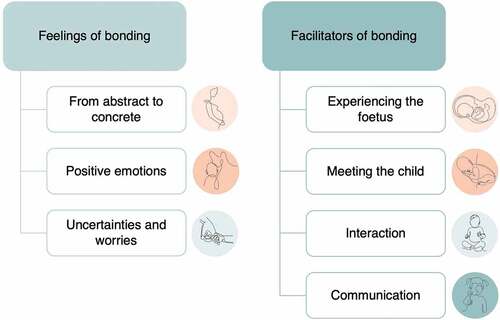

The birth of an infant marks a period of profound change in first-time parents. Parental love and warmth, however, already begin to develop during pregnancy. Also for fathers, the development of bonding to the infant may be a unique process. The current qualitative study aimed to explore views and experiences of first-time fathers on the origins and development of paternal bonding during pregnancy and early childhood. In total, 30 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with expectant fathers (second or third trimester of pregnancy; n = 10) and fathers of infants (0–6 months postpartum; n = 11) and toddlers (2–3 years of age; n = 9). Two major themes were uncovered from the data: feelings of bonding and facilitators of bonding. The first theme was supported with three subthemes: 1) from abstract to concrete, 2) positive emotions, and 3) uncertainties and worries. The second theme, facilitators of bonding, was supported with four subthemes: 1) experiencing the foetus, 2) meeting the child, 3) interaction, and 4) communication. Similar to previous studies, our results suggested that, in most fathers, paternal bonding originates in pregnancy and that it evolves over time. Seeing or feeling the child, both during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as interacting or communicating with the child, appears to facilitate fathers’ feelings of bonding. Involving fathers in pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting may be essential for their bonding process.

The birth of a child marks a period of profound change for first-time parents. Parental love and warmth, however, already begin to develop in the prenatal period (e.g. Habib & Lancaster, Citation2010; Trombetta et al., Citation2021). Parent-to-infant bonding, defined as the emotional tie a parent feels towards their infant (Alhusen, Citation2008; Suzuki et al., Citation2022), guide caregiving behaviours after birth and is thereby foundational for future parenting competencies and child development (Alvarenga et al., Citation2013; Branjerdporn et al., Citation2017; De Cock et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Le Bas et al., Citation2020; Medina et al., Citation2021; Nakic Rados, Citation2021). For example, higher levels of maternal prenatal bonding have been associated with more positive mother-infant interaction 3 weeks postpartum (Medina et al., Citation2021) and better social-emotional development in 12-month-old infants (Le Bas et al., Citation2022). Another study demonstrated that more bonding from father to child throughout the perinatal period was related to better executive functioning in children at 2 years of age (De Cock et al., Citation2017). In mothers, affectionate feelings towards the infant generally arise during the first trimester of pregnancy and increase as the pregnancy progresses (De Cock et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; De Waal et al., Citation2023; Le Bas et al., Citation2021; Tichelman et al., Citation2019; Trombetta et al., Citation2021). Similarly, paternal bonding has been found to increase from the first to the third trimester of pregnancy (Habib & Lancaster, Citation2010), indicating that fathers, like mothers, are more focused on and more involved with the foetus for the imminent birth. At the same time, men have reported lower levels of bonding towards the foetus than women (Lorensen et al., Citation2004; Ustunsoz et al., Citation2010), which may reflect a different and unique process of paternal bonding.

For fathers, opportunities to physically experience the pregnancy are limited compared to those of expectant mothers, and they largely depend on their partners for windows to interact with the unborn child. The lack of first-hand experiences of the foetus and not being able to carry the child, may create an emotional distance towards the pregnancy and the unborn child (Freeman, Citation2000; Guney & Ucar, Citation2019; Kowlessar et al., Citation2015b; Vreeswijk et al., Citation2014). In previous qualitative research, expectant fathers have indeed described early pregnancy as unreal (Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Kowlessar et al., Citation2015b; Widarsson et al., Citation2015). However, despite feeling disengaged, expectant fathers also reported wanting to be involved in their partners’ pregnancy (Widarsson et al., Citation2015) and, with gestation, becoming to accept the foetus as more real, enabling them to relate and emotionally connect to the unborn child (Kowlessar et al., Citation2015b; Lagarto & Duaso, Citation2022; Vreeswijk et al., Citation2014).

For some, however, an actual awareness of fatherhood did not set in until after their child was born (Shorey et al., Citation2017), and even then it took time to understand what it was like being a father (Premberg et al., Citation2008). Qualitative studies suggest that the early postpartum period can be an emotional and stressful period for fathers, in which a new balance must be found between taking care of their new-born child and supporting their partner on the one hand, and work commitments and personal engagements on the other, whilst also dealing with a lack of sleep and sometimes feeling insecure about their parenting competencies (Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Shorey et al., Citation2017). The major adjustments and new responsibilities that are evident to the transition into parenthood put men, like women, at risk for developing mental health problems (Parfitt & Ayers, Citation2014). According to recent meta-analyses, prevalence rates vary between 7–14% for depression and 9–12% for anxiety in men during or after their partner’s pregnancy (Leiferman et al., Citation2021; Rao et al., Citation2020). Psychological problems are a well-known risk factor for poor bonding to the infant, also in fathers (Baldy et al., Citation2023; Kerstis et al., Citation2016; Knappe et al., Citation2021; Nasreen et al., Citation2022).

Although the transition into fatherhood may be challenging, qualitative studies also indicated that fatherhood brought about a sense of accomplishment and personal growth (Baldwin et al., Citation2019), as well as love, pride, and happiness within the family (Premberg et al., Citation2008). Men reported enjoying interacting with their child and watching them grow (Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Premberg et al., Citation2008). They wanted to be an involved father and strived for a loving relationship (Premberg et al., Citation2008). Spending time alone with the child, particularly alone, was thought to facilitate this process by gaining knowledge on the child’s character and needs, and by developing parental sensitivity (i.e. correctly interpreting and responding to infant signals; Ainsworth et al., Citation1974), which fathers considered to be essential in bonding with the child (Kowlessar et al., Citation2015a; Premberg et al., Citation2008). Although not many studies examined the continuity of paternal bonding over the transition into parenthood, De Cock et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that, despite showing some variety in the level of pre- and postnatal bonding, fathers’ feelings of bonding were relatively stable from pregnancy to toddlerhood.

Previous research provided valuable insights into fathers’ experiences and feelings during their transition into parenthood, but few qualitative studies focused on paternal bonding specifically and none were from the Netherlands. Moreover, the majority of these studies included either the prenatal period or the first year after childbirth, whereas little qualitative research has examined the feelings and thoughts of fathers on the relationship with their child in a wider period of time. To our knowledge, not much is known, qualitatively, about paternal bonding after the first postpartum year. This is unfortunate given the unique and important position of fathers in pregnancy and early caregiving (e.g. Challacombe et al., Citation2023; Fisher et al., Citation2021), a role that has substantially increased over the last decades, at least in Western industrialised countries (Alio et al., Citation2013; Boll et al., Citation2014). The present qualitative study therefore explored the views and experiences of first-time fathers on the origins and development of paternal bonding during pregnancy and early parenthood in a Dutch sample. The aim was to identify several themes from in-depth individual interviews that were key for fathers in different stages of the transition into parenthood: pregnancy, the postpartum period, and toddlerhood.

Method

Participants

Fathers were recruited via an online advertisement sent to women participating in the Brabant Study, a large prospective perinatal cohort study examining obstetric outcomes from a biopsychosocial perspective in pregnant women (Meems et al., Citation2020). Additionally, information on the study was shared on social media, via word-of-mouth, and through flyers. Recruitment took place between May and October 2022. First-time expectant fathers whose partner was in the second or third trimester of pregnancy and fathers with a firstborn child aged 0–6 months or 2–3 years were eligible for participation. Additionally, participants had to be 18 years or older and have a sufficient understanding of the Dutch language. Thirty-seven participants were interested in participation, of which one father was not eligible and six fathers did not return informed consent. This resulted in a total of 30 fathers participating in the study of whom 10 during their partner’s pregnancy, 11 during the postpartum period, and 9 during toddlerhood. All fathers were Dutch and married and/or cohabiting with their partners. None of the fathers of infants or toddlers indicated being the primary caretaker of the child. One father of a toddler indicated that he was currently receiving treatment for depression. Three fathers indicated that they once received treatment for a depression (one expectant father and one father of an infant) or an anxiety disorder (father of a toddler), but not at this moment. Further demographics are presented in . All participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University (reference TSB_RP350) and preregistered at https://aspredicted.org/JXG_RGP.

Table 1. Demographics.

Procedures

Participants completed one in-depth semi-structured interview that lasted on average 33 minutes (range 17–49 minutes) and took place in an online environment. The researchers used an interview guide to make sure that all questions and topics were attended to in the different interviews. However, the researcher would ask follow-up questions to each individual participant in order to stimulate a more in-depth answer. The order in which the questions were asked differed per interview in order for the interview topics to flow and develop naturally. Interviews were audio-recorded using a digital voice recorder and conducted by the first or last author, or a research assistant who was trained by the first or last author. Before the start of the interview, participants were informed on the general aim of the study and were told that they were not obliged to answer a question if that made them feel uncomfortable in any way. After the interview, fathers completed an online questionnaire on general demographics. Fathers received a small present for the child and a gift voucher worth 5 Euros to thank them for their participation. Participants were included in the study until no new information was obtained and data saturation was reached.

Interview

For the purpose of this study, a semi-structured interview guide was developed by the first (NdW) and last author (MB). The topics and questions of this guide were based on earlier qualitative literature on parental bonding (e.g. Kowlessar et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b), as well as on items of questionnaires assessing bonding quality (e.g. Cuijlits et al., Citation2016). The guide was pilot tested on one father who fit the inclusion criteria, but who was not included in the study. No changes were made based on the pilot interview. During the interview, participants were asked to describe their feelings and thoughts towards their infant, as well as the origins and development of these feelings, and to reflect upon the time spent with their child. Overall, the interview guide was similar for each group with only slight adaptations according to the father’s situation. For example, fathers were asked to describe their feelings of becoming a father for the first time, or how they felt in their father role. Other examples of questions were: ‘How would you describe your feelings towards your child?’ and ‘Can you remember whether there was a moment that you first felt an emotional connection with your child?’. In general, all participants in the same group were asked similar questions, but the sequence and phrasing could be changed according to previous answers. Additional questions could be asked to further explore or clarify participants’ responses.

Data analyses

Analyses were conducted in ATLAS.ti (Version 22.2.5.0) by the first (NdW) and last author (MB), using inductive thematic analyses. First, interviews were transcribed verbatim using clear verbatim rules and checked for accuracy. Then, transcripts were uploaded in ATLAS, a coding and organising programme, in which text fragments were coded by means of the code manager. Subsequently, based on the content of these codes, they were allocated to different themes that were identified by the first and last author. An overview was then made describing the condensed meaningful units (i.e. an interpretation of the underlying meaning of the text fragment), codes, and themes. For each group of fathers, one interview was coded independently by the first and last author. After consensus was reached, the first author coded the rest of the interviews under supervision of the last author. Coding was inductive and not driven by an a priori framework. Codes and themes were reviewed and refined by the second author (MvdH).

Results

Two major themes were uncovered from the data: feelings of bonding and facilitators of bonding. The first theme was supported with three subthemes: 1) from abstract to concrete, 2) positive emotions, and 3) uncertainties and worries. The second theme was supported with four subthemes: 1) experiencing the foetus, 2) meeting the child, 3) interaction, and 4) communication. gives an overview of the major themes and subthemes, codes, and examples of condensed meaningful units. presents a graphical overview of the major themes and their subthemes.

Table 2. Overview of major and subthemes, codes, and examples of condensed meaningful units.

Feelings of bonding

From abstract to concrete

Expectant fathers

In early pregnancy, fathers described the bond to their child as abstract. They felt an emotional distance to the child since they were not able to hold the child or to feel its physical presence in a way that their partner could, as one expectant father explained:

I am happy to know that the baby is here, but it feels rather distant. It is not growing in my body, so it feels very different. I cannot hold it, and therefore I have to use a lot of imagination.

Positive emotions

Expectant fathers

Despite feeling disengaged at some points, almost all expectant fathers reported positively on their feelings towards their unborn child. They indicated that their child meant a lot, that they felt warm when they saw the child on ultrasound scans, and that they felt love and wanted to take care of the child, whom they had not yet met. For some, the child had already become a big part of fathers’ life and felt like they would do anything to make sure that the child was well. For a few fathers, this resulted in being more protective towards their partner, who carried their child. Fathers also described feelings of happiness and pride when thinking about their unborn child or seeing the child on ultrasound scans. They were curious and looked forward to meeting and getting to know their child. Most fathers felt close and connected to the child during pregnancy, and some indicated that these feelings increased with the imminent birth. For some, thinking about the child gave them a family-like feeling, as explained by one father:

‘We feel her [the father’s child] throughout the entire day, which I really enjoy. It feels like there are three of us already’.

Fathers of infants and toddlers

Fathers of infants and toddlers described similar feelings. They felt warmth and unconditional love towards their child, who was, by some fathers, described as indispensable and the most important thing in life. It felt good to take care of their child, and some fathers indicated that they would always be there for their child. One father described the bond to his child as: ‘It is like a sort of love that I have never experienced before’. Fathers also thought of their child as a source of joy, energy, and happiness. They enjoyed seeing the child grow and felt proud when the child mastered a new skill, even though they knew it was part of a typical development. The child was described as an enrichment of their life and fathers, of toddlers mostly, enjoyed spending time with them. Some fathers indicated that the bond to their child felt natural and familiar, as this was how it should be. They described the relationship with their child as close, intimate, deep, and pure. The general feeling was that these feelings grew over time, from pregnancy or birth onwards, and got more intense as the child grew older. Some fathers of toddlers described that they particularly enjoyed seeing themselves reflected in their child.

Uncertainties and worries

Expectant fathers

Besides positive emotions, some expectant fathers also expressed worries or feelings of anxiety, for example, regarding foetal health or for how their situation would change after childbirth. Some fathers also described feeling responsible for the child. One father explained: ‘I feel responsible. Although she [the father’s child] is not yet here, she is completely dependent on us parents and we must make sure that she is well, as far as that is possible’.

Fathers of infants

Some fathers of infants described similar feeling, with worrying being an evident part of fatherhood. The majority of these fathers felt highly responsible, since their child was entirely dependent on them. A few also indicated feeling insecure, for example when not succeeding in soothing the child, and feeling that they had to adapt to the new situation. One father described:

At times, I feel insecure. For example, when he [the father’s child] cries and there is nothing I can do to help. That is hard, I then withdraw from the situation. At these moments, it is difficult to feel a connection. That is not because I do not care about him, but because I am insecure, and I do not know what to do.

Facilitators of bonding

Experiencing the foetus

Expectant fathers

Some moments during pregnancy marked important changes for fathers’ feelings towards their child. For example, seeing the foetus on ultrasound scans or hearing its heartbeat made the pregnancy and child more real, as described by one expectant father as: ‘The first ultrasound scan and the first time that I heard the baby’s heartbeat made me realise that there was a human being inside’. It also enabled fathers to imagine the child a bit better. For some, the first ultrasound scan was an overwhelming experience, which gave rise to an emotional connection to the child or strengthened the feelings they already had. For others, however, ultrasound scans were merely a confirmation of the foetus’ health and did not alter nor facilitate the bond with their child.

Feeling foetal movement for the first time also marked the beginning of bonding for some expectant fathers. One expectant father described: ‘The first time I felt her [the father’s child] kicking was overwhelming. That was my baby in there. I felt small. It feels unreal, you are making new life together, that is very special’. The majority of fathers regularly placed their hand on their partners’ abdomen to feel and make contact with the child. Feeling the foetus move felt special and, according to most fathers, facilitated the emotional connection with the child since the child became more real. These feelings increased as the child became more active. One father described that his feelings for the child were most intense at the moment he felt his child move while his partner was sleeping, since it felt like they had spent some time alone. Most fathers, but not all, had the idea that the child responded to their touch, which was considered beneficial for the bond. Fathers also tried to make contact by singing or talking to their unborn child. However, most indicated that they felt a bit awkward doing so, and they had the idea that the child responded better to touch than to voices or sounds.

Meeting the child

Fathers of infants

Fathers described childbirth as a special and unique moment that radically changed their feelings towards the child. For some fathers, it felt like the beginning of a true connection, since the child was now physically there and fathers could see and hold their child themselves, rather than leaning on second-hand experiencing via their partner. This made a huge difference for them. Others did feel a connection already during pregnancy but indicated that this was not comparable with what they experienced after birth, as explained by one father: ‘From the beginning, you make a choice to take care of your child but at that point, few feelings are involved. However, when holding your child after birth, feelings arise that support that decision’. Where most fathers instantly felt love and connectedness, others took some time to get used to the infants and taking care of the child, to recover from an intense delivery, and to realise they had become a father.

Interaction

Fathers of infants

For fathers of infants, interacting with their infant was key in the bonding process. They described moments where the child made eye contact, laughed, or seemed to recognise their father, as moments that facilitated the bond towards their child. They felt more love, happiness, and more closely connected to their infant as these moments of interaction occurred more often. Fathers described that, in the first weeks postpartum, everything revolved around taking care of the infant’s basic needs and that no or little interaction was possible, which made them feel detached since there was only little they could do. However, as the child grew older, opportunities to interact increased and this strengthened the bond, at least for the majority of fathers. One father described this as follows:

The first weeks she [the father’s child] did not do much. I knew that she was my daughter, but I might as well have been watching someone else’s child. Now, there is interaction. She laughs back at me, or she stops crying or starts laughing when I pick her up. That makes the bond stronger. Of course, I was fond of her from the first day, but at the same time, it had to grow. Now that there is interaction, it keeps getting better.

Fathers of toddlers

Fathers of toddlers described similar feelings but had also noticed a turning point when the child first initiated contact with the father, for example by giving him a spontaneous hug. In addition, fathers enjoy the enthusiastic greetings of their child, playing with them, and laughing together, and these moments were thought to facilitate the bond.

Communication

Fathers of toddlers

In the postpartum period, some fathers felt like the communication with their child was one-sided, since the child could not talk back. The developing language skills of toddlers made fathers enjoy the interaction with their child more. They felt like they could interact with the child on a different level and liked, for example, that their child began to understand and make jokes. In addition, they enjoyed that the child took initiative by indicating his or her preferences. This made it easier for fathers to understand their child, and they liked the fact that the child’s opinion mattered and not all decisions had to be made by the father himself. One father of a toddler explained:

Her language skills are developing, and she [the father’s child] can now express what is going on in her head. That is especially sweet, funny, and cute. The bond is therefore different every day. She is also able to express more and more how she sees a relationship. She can say that she likes her dad and, although it may sound selfish, that feels like getting something in return for the investment that I made over the past years. She is also better in explaining what she likes or dislikes. So, she is more in charge, and I like that.

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore views and experiences of first-time fathers on the origins and development of paternal bonding during pregnancy and early childhood. As an addition to previous qualitative research on the transition into fatherhood, we focused specifically on paternal bonding and included both expectant fathers, as well as fathers of infants and toddlers. By doing so, we aimed to provide new insights into and understanding of the bonding process of men throughout pregnancy and the first years of childhood. Results of the inductive thematic analyses identified two main overarching themes that are of importance to the father-child bond: feelings of bonding and facilitators of bonding. Themes were supported by several subthemes: from abstract to concrete, positive emotions, and uncertainties and worries (concerning the feelings of bonding), and experiencing the foetus, meeting the child, interaction, and communication (as facilitators of bonding).

The first subtheme that was identified regarding the feelings of bonding, suggested that, in the early prenatal period, men generally think of the unborn child as unreal and abstract, as has also been reported in earlier research (e.g. Kowlessar et al., Citation2015b). These feelings may be affected by the fact that fathers’ opportunities to experience the pregnancy and the foetus are limited and largely dependent on their partner, who is physically carrying the child (De Waal et al., Citation2022; Freeman, Citation2000; Guney & Ucar, Citation2019). However, throughout pregnancy, most fathers become to accept the child as a tangible human being (Lagarto & Duaso, Citation2022) and, similar to previous research (e.g. Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Premberg et al., Citation2008), fathers felt love, happiness, pride, and closeness to the unborn child, as identified by the second subtheme. Although the levels of paternal bonding differ, it appears that fathers in general, like mothers, feel attached to their infant before birth. Seemingly, for most fathers, bonding originates in pregnancy and increases with gestation, as was also found in previous research (Habib & Lancaster, Citation2010).

Although positive feelings towards the unborn child were described by many expectant fathers, the reports of the pregnancy being unreal and abstract suggest that fathers may have a harder time bonding to their infant compared to women and may have different needs. For instance, their feelings of bonding might benefit more from contact and direct experiences with the child. In the second overarching theme, the current study identified various facilitators that enhanced the bond between father and child at the different stages of development. First, experiencing the child appears to be important for fathers’ process of bonding to their child. Seeing the foetus via ultrasound scans and feelings its movements through the partners’ abdomen appeared to facilitate the paternal bond, at least for some fathers, as was also demonstrated by previous research (e.g. Lagarto & Duaso, Citation2022; Poh et al., Citation2014). However, not all fathers found ultrasound imaging helpful, potentially explaining why other studies (e.g. Harpel & Barras, Citation2018) did not find an increase in paternal bonding after seeing the unborn child on an ultrasound scan.

Moving on to a later stage of the transition into parenthood, the birth of the child marked an important change in fathers’ feelings towards their child. It was described that first-hand experiences after birth (i.e. seeing and holding the child) made an even greater impact on paternal feelings of bonding. These findings are in line with previous research that demonstrated positive outcomes for skin-to-skin contact between father and child after birth, such as more confidence in fathers’ parental role (Blomqvist et al., Citation2012) and higher levels of paternal bonding (Chen et al., Citation2017; Unal Toprak & Senturk Erenel, Citation2021). Although difficult to compare, the results seem different from the results of a quantitative study that found levels of paternal bonding to be relatively stable throughout the perinatal period (De Cock et al., Citation2016). However, the authors were not able to draw any conclusions on the differences in scores between the pre- to postnatal period since the questionnaires used included different items.

Second, for fathers it seems valuable for the relation to be reciprocal or to ‘get something in return’. Two subthemes suggested that significant changes in the bonding process occurred with the first moments of interaction and opportunities to communicate with the child. These interactions and communications contributed to fathers feeling more appreciated and fulfilled and made them understand the child better. Besides, basic caretaking gradually shifted to raising the child, which fathers found more challenging, but also enjoyed more. These findings are in line with a quantitative study that demonstrated an increase in fathers’ reports of child temperament over the first year of life in terms of activity level, smiling and laughter, and high pleasure (Sechi et al., Citation2020). The results are also in line with the general presumption that mothers, in general, are more associated with caregiving behaviours such as bathing or feeding, whereas fathers tend to be more engaged in interactive activities such as physical play, reading, and teaching, and challenge the infant more often (Bornstein, Citation2002; Craig, Citation2006; John et al., Citation2013). Moreover, in the early postpartum period, fathers’ opportunities for solo care or overall involvement may be restricted, for example due to breastfeeding – that is exclusively destined for the mother – and paternal leave which is limited compared to that of mothers (Perez et al., Citation2018; Premberg et al., Citation2008; Wilson & Prior, Citation2010). Accordingly, fathers have reported that the time spent with their child increased over time (Premberg et al., Citation2008). This may be especially interesting in the current study as fathers of toddlers seem to be at home more as they work part-time more often compared to expectant fathers and fathers of infants. Furthermore, paternal sensitivity is known to increase throughout early childhood (Brown et al., Citation2012; Hallers-Haalboom et al., Citation2017; Tissot et al., Citation2015), which may reflect more understanding of the infant’s needs, interests, and wishes, and potentially a stronger emotional tie from father to child as well.

Our findings emphasise the importance of including fathers in pregnancy and childcare, both in research and in clinical practice. Thus far, studies on parental-infant bonding are mainly focused on mothers and variables that are associated with paternal bonding remain unexplored (Suzuki et al., Citation2022). That is unfortunate, since fathers may substantially differ in their process of bonding with their infant compared to mothers (Lorensen et al., Citation2004; Ustunsoz et al., Citation2010). Future research may further address the potential facilitators and risk factors of paternal bonding, also by using a quantitative research design. In addition, further studies are necessary that examine the development or continuity of paternal bonding throughout the perinatal period. For clinical practice, the results of the current study imply that it is essential to involve fathers in prenatal health care visits, during childbirth, and in parenting, since seeing, holding, and interacting with the infant presumably facilitates the bonding process. Moreover, it may be important to be aware of fathers’ different process and pace of bonding with their infant and increase opportunities to facilitate this process.

Strengths of the present study were the inclusion of fathers in different stages of their transition into parenthood. In addition, the qualitative nature of the study gave (expectant) fathers the opportunity to describe their experiences in detail. However, there are also some limitations. First, the sample we included was not representative of the population, with fathers being overall highly educated and no fathers with an ethnic minority background partaking in the study. Additionally, all fathers that participated in the present study were married and/or cohabiting with their partner. Results may differ for fathers who are not together with the mother of their child, since they might be less involved in pregnancy and childcare. Further, it is presumable that fathers who agreed to participate were already interested in and involved with their child. As we do not know the characteristics and experiences of those fathers who did not respond to participation, the current sample might represent a group of fathers with a positively skewed involvement in parenting. Therefore, caution is necessary when generalising the results. Future research may address the father-infant bond across different subgroups of fathers, such as fathers with a low socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities, or teenage fathers. Another limitation concerns the restricted number of fathers that were included in this qualitative study. Furthermore, the current study was not longitudinal, which does not allow drawing conclusions on associations between variables or capturing the development of paternal bonding over time. Finally, paternal bonding may be affected by a variety of other factors which have not been accounted for in the present study (e.g. mental health, partner support; Baldy et al., Citation2023; De Cock et al., Citation2016). One of these influencing factors may include paternal involvement with the child, which might have been particularly relevant in the current study since fathers of toddlers more often had parttime employment, compared to expectant fathers and fathers of infants, of whom the majority was employed full-time.

In conclusion, results from the present study indicated that, in most fathers, bonding originates during pregnancy and that it evolves over time. Paternal feelings of bonding appear to be facilitated when seeing or feeling the child, both during pregnancy and after birth, and during moments of interaction and communication with their child. From these results, we may imply that it is important for fathers to be involved in pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting, since this may be essential for their bonding process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1974). Infant mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In M. P. M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press.

- Alhusen, J. L. (2008). A literature update on maternal-fetal attachment. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 37(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00241.x

- Alio, A. P., Lewis, C. A., Scarborough, K., Harris, K., & Fiscella, K. (2013). A community perspective on the role of fathers during pregnancy: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-60

- Alvarenga, P., Dazzani, M. V. M., Da Rocha Lordelo, E., Dos Santos Alfaya, C. A., & Piccinini, C. A. (2013). Predictors of sensitivity in mothers of 8-month-old infants. Paidéia, 23(56), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272356201305

- Baldwin, S., Malone, M., Sandall, J., & Bick, D. (2019). A qualitative exploratory study of UK first-time fathers’ experiences, mental health and wellbeing needs during their transition to fatherhood. BMJ Open, 9(9), e030792. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030792

- Baldy, C., Piffault, E., Chopin, M. C., & Wendland, J. (2023). Postpartum Blues in fathers: Prevalence, associated factors, and Impact on father-to-infant bond. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105899

- Blomqvist, Y. T., Rubertsson, C., Kylberg, E., Joreskog, K., & Nyqvist, K. H. (2012). Kangaroo mother care helps fathers of preterm infants gain confidence in the paternal role. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(9), 1988–1996. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05886.x

- Boll, C., Leppin, J., & Reich, N. (2014). Paternal childcare and parental leave policies: Evidence from industrialized countries. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(1), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9211-z

- Bornstein, M. H. (2002). Parenting infants. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting. Volume 1. Children and Parenting (pp. 21–22). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Branjerdporn, G., Meredith, P., Strong, J., & Garcia, J. (2017). Associations between maternal-foetal attachment and infant developmental outcomes: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(3), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2138-2

- Brown, G. L., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Neff, C. (2012). Father Involvement, Paternal Sensitivity, and Father-Child Attachment Security in the First 3 Years. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027836

- Challacombe, F. L., Pietikainen, J. T., Kiviruusu, O., Saarenpaa-Heikkila, O., Paunio, T., & Paavonen, E. J. (2023). Paternal perinatal stress is associated with children’s emotional problems at 2 years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(2), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13695

- Chen, E. M., Gau, M. L., Liu, C. Y., & Lee, T. Y. (2017). Effects of father-neonate skin-to-skin contact on attachment: A randomized controlled trial. Nursing Research and Practice, 2017, 8612024. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8612024

- Craig, L. (2006). Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender & Society, 20(2), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205285212

- Cuijlits, I., Van de Wetering, A. P., Potharst, E. S. M.T. S. E., Van Baar, A. L., & Pop, V. J. M. (2016). Development of a Pre- and Postnatal Bonding Scale (PPBS). Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0487.1000282

- De Cock, E. S. A., Henrichs, J., Klimstra, T. A., Janneke, B. M. M. A., Vreeswijk, C., Meeus, W. H. J., & van Bakel, H. J. A. (2017). Longitudinal Associations between parental bonding, parenting stress, and executive functioning in Toddlerhood. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(6), 1723–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0679-7

- De Cock, E. S., Henrichs, J., Vreeswijk, C. M., Maas, A. J., Rijk, C. H., & van Bakel, H. J. (2016). Continuous feelings of love? The parental bond from pregnancy to toddlerhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000138

- De Waal, N., Alyousefi van Dijk, K., Buisman, R. S. M., Verhees, M., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2022). The prenatal video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting for expectant fathers (VIPP-PRE): Two case studies. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(5), 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22006

- De Waal, N., Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Nyklíček, I., & Pop, V. J. M. (2023). Maternal-infant bonding and partner support during pregnancy and postpartum: Associations with early child social-emotional development. Infant Behavior & Development, 72, 101871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2023.101871

- Fisher, S. D., Cobo, J., Figueiredo, B., Fletcher, R., Garfield, C. F., Hanley, J., Ramchandani, P., & Singley, D. B. (2021). Expanding the international conversation with fathers’ mental health: Toward an era of inclusion in perinatal research and practice. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 24(5), 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01171-y

- Freeman, A. (2000). The influence of ultrasound-stimulated paternal-fetal bonding and gender identification. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography, 16(6), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/875647930001600604

- Guney, E., & Ucar, T. (2019). Effect of the fetal movement count on maternal-fetal attachment. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 16(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12214

- Habib, C., & Lancaster, S. (2010). Changes in identity and paternal–foetal attachment across a first pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 28(2), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903298723

- Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Groeneveld, M. G., Van Berkel, S. R., Endendijk, J. J., Van der Pol, L. D., Linting, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2017). Mothers' and Fathers' Sensitivity With Their Two Children: A Longitudinal Study From Infancy to Early Childhood. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 860–872. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000293

- Harpel, T. S., & Barras, K. G. (2018). The impact of ultrasound on prenatal attachment among disembodied and embodied knowers. Journal of Family Issues, 39(6), 1523–1544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X17710774

- John, A., Halliburton, A., & Humphrey, J. (2013). Child–mother and child–father play interaction patterns with preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.711595

- Kerstis, B., Aarts, C., Tillman, C., Persson, H., Engstrom, G., Edlund, B., Ohrvik, J., Sylven, S., & Skalkidou, A. (2016). Association between parental depressive symptoms and impaired bonding with the infant. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0522-3

- Knappe, S., Petzoldt, J., Garthus-Niegel, S., Wittich, J., Puls, H. C., Huttarsch, I., & Martini, J. (2021). Associations of partnership quality and father-to-child attachment during the peripartum period. A prospective-longitudinal study in expectant fathers. Frontiers in Psychiatry / Frontiers Research Foundation, 12, 572755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.572755

- Kowlessar, O., Fox, J. R., & Wittkowski, A. (2015a). First-time fathers’ experiences of parenting during the first year. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.971404

- Kowlessar, O., Fox, J. R., & Wittkowski, A. (2015b). The pregnant male: A metasynthesis of first-time fathers’ experiences of pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(2), 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.970153

- Lagarto, A., & Duaso, M. J. (2022). Fathers’ experiences of fetal attachment: A qualitative study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21965

- Le Bas, G. A., Youssef, G. J., Macdonald, J. A., Mattick, R., Teague, S. J., Honan, I., McIntosh, J. E., Khor, S., Rossen, L., Elliott, E. J., Allsop, S., Burns, L., Olsson, C. A., & Hutchinson, D. M. (2021). Maternal bonding, negative affect, and infant social-emotional development: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.031

- Le Bas, G. A., Youssef, G. J., Macdonald, J. A., Rossen, L., Teague, S. J., Kothe, E. J., McIntosh, J. E., Olsson, C. A., & Hutchinson, D. M. (2020). The role of antenatal and postnatal maternal bonding in infant development: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Social Development, 29(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12392

- Le Bas, G., Youssef, G., Macdonald, J. A., Teague, S., Mattick, R., Honan, I., McIntosh, J. E., Khor, S., Rossen, L., Elliott, E. J., Allsop, S., Burns, L., Olsson, C. A., & Hutchinson, D. (2022). The role of antenatal and postnatal maternal bonding in infant development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(6), 820–829 e821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.024

- Leiferman, J. A., Farewell, C. V., Jewell, J., Rachael, L., Walls, J., Harnke, B., & Paulson, J. F. (2021). Anxiety among fathers during the prenatal and postpartum period: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 42(2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2021.1885025

- Lorensen, M., Wilson, M. E., & White, M. A. (2004). Norwegian families: Transition to parenthood. Health Care for Women International, 25(4), 334–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490278394

- Medina, N. Y., Edwards, R. C., Zhang, Y., & Hans, S. L. (2021). Prioritising our research networks. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 39(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2021.1886257

- Meems, M., Hulsbosch, L., Riem, M., Meyers, C., Pronk, T., Broeren, M., Nabbe, K., Oei, G., Bogaerts, S., & Pop, V. (2020). The Brabant study: Design of a large prospective perinatal cohort study among pregnant women investigating obstetric outcome from a biopsychosocial perspective. BMJ Open, 10(10), e038891. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038891

- Nakic Rados, S. (2021). Parental sensitivity and responsiveness as mediators between postpartum Mental Health and bonding in mothers and fathers. Frontiers in Psychiatry / Frontiers Research Foundation, 12, 723418. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.723418

- Nasreen, H. E., Pasi, H. B., Aris, M. A. M., Rahman, J. A., Rus, R. M., & Edhborg, M. (2022). Impact of parental perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms trajectories on early parent-infant impaired bonding: A cohort study in east and west coasts of Malaysia. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(2), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01165-w

- Parfitt, Y., & Ayers, S. (2014). Transition to parenthood and mental health in first-time parents. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21443

- Perez, A., Van den Brakel, S. M., & Portegijs, W. (2018). Welke gevolgen heeft ouderschap voor werk en economische zelfstandigheid? In Emancipatiemonitor 2018. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau/Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. https://digitaal.scp.nl/emancipatiemonitor2018/welkegevolgen-heeft-ouderschap-voor-werk-en-economische-zelfstandigheid/

- Poh, H. L., Koh, S. S., & He, H. G. (2014). An integrative review of fathers’ experiences during pregnancy and childbirth. International Nursing Review, 61(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12137

- Premberg, A., Hellstrom, A. L., & Berg, M. (2008). Experiences of the first year as father. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00584.x

- Rao, W. W., Zhu, X. M., Zong, Q. Q., Zhang, Q., Hall, B. J., Ungvari, G. S., & Xiang, Y. T. (2020). Prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.030

- Sechi, C., Vismara, L., Rolle, L., Prino, L. E., & Lucarelli, L. (2020). First-time mothers’ and fathers’ developmental changes in the perception of their daughters’ and sons’ temperament: Its association with parents’ Mental Health. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02066

- Shorey, S., Dennis, C. L., Bridge, S., Chong, Y. S., Holroyd, E., & He, H. G. (2017). First-time fathers’ postnatal experiences and support needs: A descriptive qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(12), 2987–2996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13349

- Suzuki, D., Ohashi, Y., Shinohara, E., Usui, Y., Yamada, F., Yamaji, N., Sasayama, K., Suzuki, H., Nieva, R. F., Jr., da Silva Lopes, K., Miyazawa, J., Hase, M., Kabashima, M., & Ota, E. (2022). The current concept of paternal bonding: A systematic scoping review. Healthcare (Basel), 10(11), 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112265

- Tichelman, E., Westerneng, M., Witteveen, A. B., van Baar, A. L., van der Horst, H. E., de Jonge, A., Berger, M. Y., Schellevis, F. G., Burger, H., Peters, L. L., & Heikkila, K. (2019). Correlates of prenatal and postnatal mother-to-infant bonding quality: A systematic review. PLoS One, 14(9), e0222998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222998

- Tissot, H., Favez, N., Udry-Jorgensen, L., Frascarolo, F., & Despland, J. N. (2015). Mothers' and Fathers' Sensitive Parenting and Mother-Father-Child Family Alliance During Triadic Interactions. The Family Journal, 23(4), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480715601110

- Trombetta, T., Giordano, M., Santoniccolo, F., Vismara, L., Della Vedova, A. M., & Rolle, L. (2021). Pre-natal attachment and parent-to-infant attachment: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620942. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620942

- Unal Toprak, F., & Senturk Erenel, A. (2021). Impact of kangaroo care after caesarean section on paternal-infant attachment and involvement at 12 months: A longitudinal study in Turkey. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(5), 1502–1510. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13210

- Ustunsoz, A., Guvenc, G., Akyuz, A., & Oflaz, F. (2010). Comparison of maternal-and paternal-fetal attachment in Turkish couples. Midwifery, 26(2), e1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2009.12.006

- Vreeswijk, C. M. J. M., Maas, A. J. B. M., Rijk, C. H. A. M., & Van Bakel, H. J. A. (2014). Fathers’ experiences during pregnancy: Paternal prenatal attachment and representations of the Fetus. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033070

- Widarsson, M., Engstrom, G., Tyden, T., Lundberg, P., & Hammar, L. M. (2015). ‘Paddling upstream’: Fathers’ involvement during pregnancy as described by expectant fathers and mothers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(7–8), 1059–1068. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12784

- Wilson, K. R., & Prior, M. R. (2010). Father involvement: The importance of paternal solo care. Early Child Development and Care, 180(10), 1391–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430903172335