ABSTRACT

Objectives

This mixed-methods study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effectiveness of an interactive digital training programme for non-specialist supporters providing a guided self-help intervention for postnatal depression (PND).

Methods

A total of 49 non-specialist trainees participated. Six digital training modules were flexibly delivered over a 5-week period. Training included a chatroom, moderated by a supervised assistant psychologist. Quantitatively, feasibility was assessed via participation and retention levels; acceptability was examined using course evaluation questionnaires; and effectiveness was measured pre-test-post-test quantitatively using a self-report questionnaire and pre-post using scenario questions. Participant focus groups explored feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness.

Results

The training was feasible; 41 completed the course and 42 were assessed at follow-up. Quantitative course evaluation and thematic analysis of focus group feedback demonstrated high training acceptability. RANOVAs indicated training significantly improved knowledge and confidence pre- to post-test. There were demonstrable increases in specific skills at post-test as assessed via clinical scenarios.

Conclusion

This training is a feasible, acceptable and effective way to upskill non-specialists in supporting treatment for PND, however supervised practice is recommended to ensure participants embed knowledge competently into practice. The training offers an effective first step in upskilling non-specialist supporters to support women with PND treatment at scale.

Introduction

Postnatal depression (PND) is a public health problem, affecting 10% to 25% of women postnatally (Howard et al., Citation2014; Noonan et al., Citation2017). Left untreated, PND can be highly distressing and disabling, with risks of both negatively impacting parenting (O’Hara & McCabe, Citation2013), and increasing potential cognitive and socioemotional problems across the child’s lifespan (Viveiros & Darling, Citation2019). Together with other perinatal mental health problems, PND is costly. In England, estimated costs are £8.1 billion/year (Bauer et al., Citation2014); in the United States they are $14 billion/year (Luca et al., Citation2020).

Whilst there are effective treatments for PND, access to perinatal-specific support varies within different healthcare systems based on symptom severity, healthcare insurance accessibility or healthcare provider availability. As early identification and intervention are associated with better treatment outcomes and relapse reduction (Hetrick et al., Citation2008), it is critical that women have prompt access to psychological treatment; akin to international calls for individuals to get ‘the right treatment at the right time’ (Kilbourne et al., Citation2018). Provider availability is a key barrier. Trained, competent licenced providers are a costly and often scarce resource amongst both high- (Singla et al., Citation2021) and low-income country healthcare systems (Clarke et al., Citation2013; Hoeft et al., Citation2017). A recent emphasis on the need to expand the reach of psychological support to a broader group of potential providers (Singla et al., Citation2018) led to England’s £301.75 million investment in ‘Start for Life’ family hubs (HM Government, Citation2022) or community centres. These provide early (0–2) parenting support, social care, health and mental health provision, with family support workers offering targeted support to families with parenting struggles and mental health problems, including depression. This workforce, however, lack training in delivering practical, accessible, effective and perinatally-tailored treatments.

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed to increase the reach and scale of effective mental health provision through self-help and guided self-help interventions supported by non-specialists (World Health Organization, Citation2017). However, there is a lack of evidence about what level of training and skills are necessary for non-specialist providers to effectively support guided self-help interventions (Lund et al., Citation2020). This is critical, as recent large-scale trials of non-specialist led interventions with minimal supporter training and supervision have failed to find significant treatment effects (Caulfield et al., Citation2019). In contrast, where non-specialists are appropriately upskilled, implementation outcomes are positive (Atif et al., Citation2019; Lund et al., Citation2020). Further, with digital training approaches’ recent expansion, especially since COVID, there is a lack of evidence about the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of these approaches in training the treatment delivery skills in non-specialist mental health supporters (Naslund et al., Citation2019; Rahman et al., Citation2019).

Therefore, this project aimed to test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of an online training programme for non-specialists to deliver a PND-specific guided self-help programme. This 6-week behavioural activation (BA) programme, the ‘Netmums guided self-help PND programme’ has been shown in trials to effectively reduce PND symptoms relative to a control group (O’Mahen et al., Citation2013, Citation2014) and helped form the basis for guided self-help for PND in the 2014 NICE Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health Guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2014). The training course, offered via FutureLearn, and accredited by the British Psychological Society has previously had wide uptake; since 2019 over 13,000 individuals joined, with 83% of supporters planning to use it.

In this study, we aimed to answer the following questions. For charitable sector providers:

Is the course feasible to deliver?

Is the course acceptable?

Does the course improve the knowledge, skills and competence in guided self-help for PND?

Methods

Participants

Three charitable sector organisations across the Southwest of England were invited to participate: Action for Children Exeter (Children’s Centre providing parenting support) (Action for Children, Citationn.d.), FearLess (providing support services to people experiencing domestic and sexual violence) (FearLess, Citation2022) and 0–19 Torbay (a partnership of services supporting the health, development and well-being of children, young people and families (0 to 19 Torbay 0, Citationn.d.) (see ). Staff were eligible if they were currently working in one of these organisations and had professional contact with women who may be experiencing PND symptoms. Participants included Children’s Centre workers (providing parenting support), family support workers (supporting families at home) and health navigators (support workers providing practical and emotional support) working with the Splitz Promoting Choice project (an initiative collaborating organisations and community groups to reduce health inequalities and support marginalised women).

Table 1. Total number of participants from collaborating organisations.

Procedure

This study was ethically approved by the University of Exeter’s Ethics Committee (eCLESPsy 514,190). Prior to recruitment, service leads from the collaborating organisations were briefed on the study, then liaised directly with potentially eligible staff and forwarded contact details to the research team. Individuals were approached via email and text message with study information and an invitation letter. Interested persons were sent an informed consent form to complete via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Citation2005) (a secure and GDPR compliant data survey system) which included the option of participating in a focus group.

Consented individuals completed a baseline questionnaire assessing their skills, knowledge and confidence when working with women with PND symptoms. Once completed, the trainees were emailed registration information for the FutureLearn guided self-help PND course, entitled ‘Addressing Postnatal Depression as a Healthcare Professional’. The course consisted of 6 teaching modules: (1) recognising PND symptoms and helping women to focus on a key problem to address, (2) identifying and adapting patterns of avoidance (3) communication strategies, and (4) balancing motherhood expectations and behaviours, (5) helping mothers to stay well Trainees completed the training course flexibly over 3–5-weeks. The course included reading, videos and exercises/role play material to help participants think through how to support a woman working through the PND guided self-help treatment. A key component of the training course was an online chatroom whereby trainees discussed their learning, moderated by an assistant psychologist (SD) and supervised by a perinatal clinical psychologist (HOM).

Trainees then completed both a follow-up questionnaire 5 weeks after course registration assessing their skills, knowledge and confidence when working with women with PND symptoms and course evaluation questionnaire.

Consenting trainees were invited to participate in 90-minute focus groups that included questions about the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of the training programme. Ten participants participated in one of three focus groups conducted on Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Teams, Citation2023) by SD, assisted by CJ or AD. These were video recorded and audio transcribed verbatim.

Measures

Feasibility

Feasibility of the course was assessed against pre-determined criteria, defined in two ways: (1) the proportion of individuals approached who agreed to participate in the course (85%), and (2) the proportion of individuals (who agreed to participate) that completed the course (75%). Feasibility of undertaking the course and providing PND support was also explored in focus groups.

Acceptability

Acceptability of the course was assessed quantitatively by questionnaires developed for this evaluation (see Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 for full questionnaires) and qualitatively by focus groups. Following (Sekhon et al., Citation2017) recommendations, we assessed the participants’ intention, affective attitudes about the training and their experiences of learning. Acceptability was quantitatively defined as at least 70% of participants rating at least 4 out of 5 points (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) on scales assessing the training programme, content and structure, and at least a 7 out of possible 10 points (1 = poor, 10 = excellent) on a scale assessing the overall experience of the course. Participants’ reports of acceptability and potential areas for improvement were explored in focus groups (see ).

Table 2. Focus group topic guide

Effectiveness

Effectiveness of the course was measured in three ways. First, baseline and post-training 16-item questionnaires assessed participant knowledge and skills on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = poor, 5 = excellent) and confidence on a 6-point Likert (1 = very confident, 6 = no confidence). Second, participants read a clinical scenario about PND and then used free-text to respond as to which model(s) and tools they might use to address the problem. Two different, but conceptually similar, scenarios were used at baseline and at post-training to avoid testing effects. They were matched on length, type of clinical problems and participant characteristics. Responses were coded and compared pre- and post-training. Finally, the effectiveness of the course was explored qualitatively in focus groups.

Analysis

Quantitative

Responses were analysed using SPSS 28 (IBM Corp, Citation2017). Descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated for knowledge/skills and confidence measures at baseline and post-training. The post-training scores were then compared to the baseline measures using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (RANOVA).

Qualitative

Content analysis of free-text scenario questions was conducted by SD and CJ, who immersed themselves in the data. Using a deductive approach, themes were decided upon as the unit of assessment. An analysis matrix was then devised and checked by HOM. Data was then coded according to categories, and SD and CJ compared codes to ensure reliability. Codes were compared with hypotheses about expected change i.e. improved knowledge about perinatally adapted BA (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008).

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was employed to analyse focus group data. SD became immersed in the transcripts, reading them multiple times and generating initial codes. These codes were iteratively discussed with CJ and a coding system was finalised with HOM. Themes were then created by SD in discussion with HOM and CJ.

Results

Feasibility

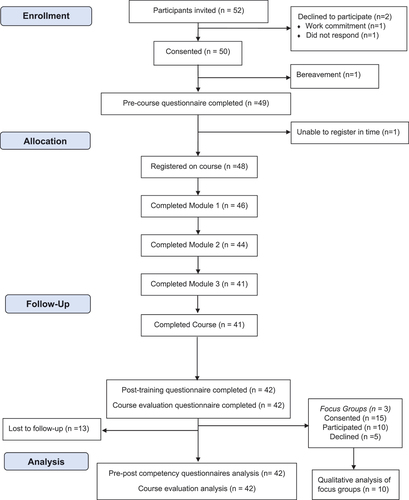

As depicted in the CONSORT diagram (), the high rates of individuals who were approached and subsequently agreed to participate (92%), completed the course (82%), and assessed at follow-up (84%) surpassed feasibility criteria. The moderated chatroom was also deemed feasible, with 39/48 (81.25%) trainees utilising it and an average of 19 comments per trainee.

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram showing participant flow through the study.

Focus groups: feasibility

The following content pertains to themes derived from the focus groups including the current landscape of perinatal mental health support within the third sector and how that informed the need for and feasibility of the programme (see ).

Table 3. ‘Context’ themes from focus groups highlighting the feasibility of undertaking the course in third sector organisations – with quotes to demonstrate.

Context: Current mental health support offered

Participants emphasised that mental health and parenting support for perinatal women was fragmented and sporadic, describing their services as inundated with referrals. These services primarily provide universal and non-targeted support. Pre-training, participants reported they referred women to other services, such as secondary perinatal mental health services, midwifery and health visitors. Furthermore, women often fell through gaps in these services, as their symptoms were either not severe enough for secondary care or too complex for primary care.

Participants reported a significant in-service need for programmes that increased their knowledge and skills in supporting PND. Many reported this programme was their first in-depth training in parental mental health support. A minority had completed Health Education England funded courses in Children’s and Young People’s interventions, including CBT and attachment-based interventions for parenting.

Participants liked how the BA focus of the course complemented their organisations’ strengths-based approach.

Feasibility

All participants completed the course within the 5-week period, though many completed in 2–3 weeks. The course was reported as easy to understand, user-friendly and flexible; the flexibility enabled participants to fit it into their schedules easily.

Participants also found the moderated chat function helpful to their learning, with some describing how they made comments, while others simply enjoyed reading their peers’ comments.

Impact of stigma of mental health on course implementation

Most participants reflected on the shame associated with mental health. Pre-course they were fearful to talk about PND with colleagues and clients, reporting that this stigma may hinder the feasibility of implementing the intervention, expressing a desire for further training on talking about PND with parents.

Acceptability

Participant course evaluation

All aspects of the course met the acceptability criteria. ‘Training programme’ and ‘content and structure’ sub-measures were rated at least 4 out of a possible 5 points by at least 70% of participants and all ‘overall experience’ sub-measures were rated at least 7 out of a possible 10 points by at least 70% of participants (see Supplementary Table S1).

Areas recommended for additional training

In the course evaluation questionnaire, participants suggested topics for further training: time to consolidate learning, knowledge of recommended general support and self-help systems, dual diagnosis and PND, the impact of unhealthy relationships on PND, and conducting risk assessments.

Focus groups: acceptability

Predominant themes regarding acceptability of the course arose from focus groups describing participants’ experience of learning (see ).

Table 4. ‘Experience of learning’ themes from focus groups highlighting the acceptability of the training – with quotes to demonstrate.

Expectations

The course surpassed participants’ high expectations and was more accessible than anticipated.

Level of complexity

For most, the complexity level was appropriate and acceptable. A small minority with less exposure to previous mental health training and experience found the content occasionally too in-depth (week one was a particularly steep learning curve).

Confidence change

Participants felt more confident using the CBT model and talking about PND with staff and clients.

Areas less engaged

Two participants, qualified in the CBT-based CYP-IAPT Postgraduate Diploma training (Children and Young People) with subsequent supervision training, were already familiar with the core CBT models in the course. However, they explained ‘the day I stop wanting to refresh is the day I need to give up my job’.

Effectiveness

Knowledge and skills

Knowledge scores increased significantly from baseline (M = 39.63, SD = 11.59) to post-training (M = 61.22, SD = 7.30), F(1,40) = 189.61, p = >.001, ηp2 = .83. The effect size was large, with a Cohen’s d of 1.58. The baseline (α = .94) and post-training (α = .96) scales were highly reliable.

Confidence

Confidence scores also increased significantly from baseline (M = 54.78, SD = 14.74) to post-training (M = 32.80, SD = 8.10), where lower scores indicated higher confidence level, F(1,40) = 112.71, p = >.001, ηp2 = .74. The effect size was large, with a Cohen’s d of 1.31.The baseline (α = .97) and post-training (α = .96) scales were highly reliable.

Scenario question assessing knowledge and skills in the questionnaire

Content analysis of scenario questions assessing knowledge and skills used to address clinical PND situations (see ) indicated an increase in CBT skills from baseline to post-training. Further, the way participants would work with parenting and the parent–infant relationship notably changed; using support that directly intervenes with the parent–infant relationship pre-training, to understanding maternal triggers and reactions post-training.

Table 5. Model used to address clinical situation scenario question at baseline and post-training.

Table 6. Therapeutic task used to address clinical situation scenario question at baseline and post-training.

Table 7. Reason provided for therapeutic task used to address clinical situation scenario question at baseline and post-training.

Focus groups: effectiveness/impact of the training programme on learning and skills

Themes from focus groups surrounding the effectiveness of the training course on trainees’ learning (see ) confirmed findings from the quantitative data and qualitative scenario questions.

Table 8. ‘Learning’ themes from focus groups highlighting the effectiveness of the course on participants’ learning – with quotes to demonstrate.

Specific strategies/tools

Specific tools learned from the course was a prominent theme, based on CBT and BA models, including the mood diary, Inside-Out and Outside-In, the TRAP/TRAC model, planning conversations and what it means to be an ‘ideal mum’.

Non-specific strategies

Non-specific strategies including helping clients to overcome barriers and repeating back what a client says were discussed.

Clarity around mental health definitions/symptoms

Participants now reported clarity around mental health symptoms and stated they were able to label PND symptoms, and that once identified, symptoms could then be targeted for improvement.

Impact on practice

Themes arose on the impact on participants’ practice (see ), which was the final assessment of the course effectiveness.

Table 9. ‘Impact on practice’ themes from focus groups highlighting the effectiveness of the course on participants’ work – with quotes to demonstrate.

Use of tools

Many participants reported incorporating learning in conversations with staff and clients, with a cultural shift within organisations of how PND was discussed. There was scope to integrate the course tools within existing resources.

Approach to client-work

Participants believed the workbook would be more effective with clients one-to-one, however, group settings provide better opportunities to initially broach PND. Participants wanted to meet clients regularly, with practitioner consistency to build therapeutic relationships.

Barriers

Barriers highlighted included lack of client engagement and time for homework (self-help material), which practitioners’ skill, flexibility, and creativity could overcome.

Discussion

PND is prevalent in the community but access to support is limited, highlighting health inequalities that remain unaddressed. This mixed-methods study demonstrated that the training was: feasible to deliver to non-specialist practitioners in the charitable sector, highly acceptable, and effective at increasing participants’ knowledge, skills and confidence in managing PND symptoms. These effects, produced in a relatively short period of time, were consistent with a nascent literature examining the effectiveness of digital training programmes in upskilling non-specialist providers of mental health interventions, in high, middle and low-income countries (Clarke et al., Citation2013; Hoeft et al., Citation2017; Singla et al., Citation2021). As the first formal evaluation for this online course, the findings support the role of the voluntary sector in providing timely, accessible support for women experiencing mild to moderate PND symptoms.

Feasibility

Our findings confirmed the course was feasible to deliver to charitable sector providers. Nearly all invited individuals consented to participate, exceeding the recruitment target by 10. Course completion rates were very high (82%), exceeding the feasibility threshold, and comparable to other mental health training evaluation retention levels (e.g. 75% retention (Rahman et al., Citation2019); 94.3% (Armstrong et al., Citation2011). The moderated chatroom was also feasible, with high engagement.

The flexible training structure was a key factor to participants feasibly completing the course alongside their busy workloads.

Acceptability

The course content and structure were highly acceptable to participants. Quantitative measures (training programme, content and structure and overall experience) exceeded our acceptability thresholds. Overwhelmingly positive focus group feedback was provided by 10 participants.

The course’s range of didactic and interactive activities were rated positively. Content was delivered didactically in reading, videos and audio clips and interactively in a moderated online chat function, allowing for active learning and reflection. This approach builds on literature demonstrating that didactic strategies alone, although effective for disseminating information and increasing provider knowledge (Fixsen et al., Citation2005), produce limited sustained behaviour change.

Effectiveness

The course effectively improved participants’ knowledge, skills and competence in PND guided self-help. Knowledge/skills scores increased pre-post course and these quantitative findings were strongly corroborated with the skills-based scenario questions and focus group themes. Participants’ knowledge of PND improved from being vague and abstract to focused and CBT- and BA-based.

At baseline, participants responded to a PND clinical scenario with parenting and baby-focused activities to address mood difficulties. Post-training, most participants reported they would use CBT and BA strategies, particularly the TRAP/TRAC model and ‘Inside-Out Outside-In thinking’. Future training may benefit from helping practitioners trained in parenting approaches to apply their skills to behavioural models for PND, for example, additional procedural practice through role plays, but most importantly, supervised feedback on actual case content. This is consistent with research demonstrating that treatment comprising PND-tailored CBT and additional strategies that target parenting are associated with both improved PND and child outcomes (Stein et al., Citation2018).

The course effectively improved practitioner confidence in supporting women with PND symptoms, as suggested by pre-post quantitative improvements in confidence scores and focus group feedback. Pre-course, many trainees lacked confidence to initiate conversations with women about PND, due to awareness of parent’s self-stigma and the trainee’s lack of PND-specific training and awareness of available support. Confidence increased significantly post-training such that participants could now discuss PND with colleagues and service users, though not to fully deliver the intervention. These findings suggest this level of training effectively imparted foundational awareness skills of PND support, but further supervision was needed to embed skills in practice (Beidas & Kendall, Citation2010; Henggeler et al., Citation2002; Herschell et al., Citation2010; Schoenwald et al., Citation2009).

Consistent with many non-specialist mental health training evaluations (Armstrong et al., Citation2011; Rahman et al., Citation2019), this study utilised a pre-post-test design, lacking a control group. Confounding factors therefore cannot be ruled out; social desirability may have produced biased responses, although the quantitative responses were online and anonymous, and the scenario-based questions assessed specific skills based on free-recall and the ability to appropriately apply the correct skills. This study did not utilise case-based competence assessments (e.g. videos of participants using the workbook with clients), as the pragmatic and short-term nature of this study lacked the resources to assess competency skills both at immediate post-training or following implementation of the intervention, thus limiting our ability to determine participants’ true increase in competency over time. Indirectly however, the clinical scenarios provided a feasible mechanism to assess whether the content of their knowledge changed.

Conclusion

The online course is a feasible, acceptable and effective way to upskill charitable sector healthcare professionals working with women with mild to moderate PND symptoms. For non-specialist providers, this training serves to effectively impart important foundational PND support skills, though supervised practice would be fundamental for delivery of the intervention. This study offers a promising first step forward in extending accessible evidence-based training to non-specialists who have direct access to women in the community experiencing mild to moderate PND symptoms. This training would enable third-sector organisations staff to reach these women confidently and effectively in non-stigmatising ways and could expand access to support.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.2 KB)Acknowledgments

Thank you to South West Academic Health Science Network for our funding, Steph Comley for creating the FutureLearn course, Latika Ahuja and Samantha Eden for helping create the course content, and our participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2023.2280714

Additional information

Funding

References

- 0 to 19 Torbay. (n.d.) Retrieved December 20, 2022, from https://www.0to19torbay.co.uk/

- Action for Children. (n.d.) Retrieved December 20, 2022, from https://www.actionforchildren.org.uk/

- Armstrong, G., Kermode, M., Raja, S., Suja, S., Chandra, P., & Jorm, A. F. (2011). A mental health training program for community health workers in India: Impact on knowledge and attitudes. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-5-17

- Atif, N., Nisar, A., Bibi, A., Khan, S., Zulfiqar, S., Ahmad, I., Sikander, S., & Rahman, A. (2019). Scaling-up psychological interventions in resource-poor settings: Training and supervising peer volunteers to deliver the ‘thinking healthy programme’ for perinatal depression in rural Pakistan. Global Mental Health, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2019.4

- Bauer, A., Parsonage, M., Knapp, M., Iemmi, V., & Adelaja, B. (2014). (publication). The Costs of Perinatal Mental Health Problems. LSE & Centre for Mental Health. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59885/1/__lse.ac.uk_storage_LIBRARY_Secondary_libfile_shared_repository_Content_Bauer%2C%20M_Bauer_Costs_perinatal_%20mental_2014_Bauer_Costs_perinatal_mental_2014_author.pdf.

- Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Caulfield, A., Vatansever, D., Lambert, G., & Van Bortel, T. (2019). WHO guidance on mental health training: A systematic review of the progress for non-specialist health workers. British Medical Journal Open, 9(1), e024059. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024059

- Clarke, K., King, M., Prost, A., & Tomlinson, M. (2013). Psychosocial interventions for perinatal common mental disorders delivered by providers who are not mental health specialists in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 10(10), e1001541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001541

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- FearLess. (2022, December 9). Retrieved December 20, 2022, from https://www.fear-less.org.uk/

- Fixsen, D., Naoom, S., Blase, K., Friedman, R., & Wallace, F. (2005). (publication). Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242511155_Implementation_Research_A_Synthesis_of_the_Literature_Dean_L_Fixsen.

- Henggeler, S. W., Schoenwald, S. K., Liao, J. G., Letourneau, E. J., & Edwards, D. L. (2002). Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: The link between supervisory practices and therapist Fidelity in MST programs. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3102_02

- Herschell, A. D., Kolko, D. J., Baumann, B. L., & Davis, A. C. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005

- Hetrick, S. E., Parker, A. G., Hickie, I. B., Purcell, R., Yung, A. R., & McGorry, P. D. (2008). Early identification and intervention in depressive disorders: Towards a clinical staging model. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77(5), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1159/000140085

- HM Government. (2022). (Rep.). Family Hubs and Start for Life Programme Guide. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1096786/Family_Hubs_and_Start_for_Life_programme_guide.pdf.

- Hoeft, T. J., Fortney, J. C., Patel, V., & Unützer, J. (2017). Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: A systematic review. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12229

- Howard, L. M., Molyneaux, E., Dennis, C.-L., Rochat, T., Stein, A., & Milgrom, J. (2014). Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1775–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61276-9

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows.

- Kilbourne, A. M., Beck, K., Spaeth-Rublee, B., Ramanuj, P., O’Brien, R. W., Tomoyasu, N., & Pincus, H. A. (2018). Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: A Global perspective. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20482

- Luca, D. L., Margiotta, C., Staatz, C., Garlow, E., Christensen, A., & Zivin, K. (2020). Financial toll of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders among 2017 births in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305619

- Lund, C., Schneider, M., Garman, E. C., Davies, T., Munodawafa, M., Honikman, S. , and Susser, E. (2020). Task-sharing of psychological treatment for antenatal depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Effects on antenatal and postnatal outcomes in an individual randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 130, 103466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103466

- Microsoft teams (version 1.6.00.7354). [Computer Software]. (2023). Retrieved from https://teams.microsoft.com/edustart

- Naslund, J. A., Shidhaye, R., & Patel, V. (2019). Digital technology for building capacity of nonspecialist health workers for task sharing and scaling up mental health care globally. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000217

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance (Update) Clinical Guideline 192. Retrieved from https://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG192.

- Noonan, M., Doody, O., Jomeen, J., & Galvin, R. (2017). Midwives’ perceptions and experiences of caring for women who experience perinatal mental health problems: An integrative review. Midwifery, 45, 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.12.010

- O’Hara, M. W., & McCabe, J. E. (2013). Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 379–407. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612

- O’Mahen, H. A., Richards, D. A., Woodford, J., Wilkinson, E., McGinley, J., Taylor, R. S., & Warren, F. C. (2014). Netmums: A phase II randomized controlled trial of a guided internet behavioural activation treatment for postpartum depression. Psychological Medicine, 44(8), 1675–1689. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291713002092

- O’Mahen, H. A., Woodford, J., McGinley, J., Warren, F. C., Richards, D. A., Lynch, T. R., & Taylor, R. S. (2013). Internet-based behavioral activation—treatment for postnatal depression (NETMUMS): A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 814–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.005

- Qualtrics (version March 2023). [Computer Software]. (2005). Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com

- Rahman, A., Akhtar, P., Hamdani, S. U., Atif, N., Nazir, H., Uddin, I., Nisar, A., Huma, Z., Maselko, J., Sikander, S., & Zafar, S. (2019). Using technology to scale-up training and supervision of community health workers in the psychosocial management of perinatal depression: A non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial. Global Mental Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2019.7

- Schoenwald, S. K., Sheidow, A. J., & Chapman, J. E. (2009). Clinical supervision in treatment transport: Effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013788

- Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Singla, D. R., Lawson, A., Kohrt, B. A., Jung, J. W., Meng, Z., Ratjen, C., Zahedi, N., Dennis, C.-L., & Patel, V. (2021). Implementation and effectiveness of nonspecialist-delivered interventions for perinatal mental health in high-income countries. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 498. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4556

- Singla, D. R., Raviola, G., & Patel, V. (2018). Scaling up psychological treatments for common mental disorders: A call to action. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 226–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20532

- Stein, A., Netsi, E., Lawrence, P. J., Granger, C., Kempton, C., Craske, M. G., Nickless, A., Mollison, J., Stewart, D. A., Rapa, E., West, V., Scerif, G., Cooper, P. J., & Murray, L. (2018). Mitigating the effect of persistent postnatal depression on child outcomes through an intervention to treat depression and improve parenting: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(2), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30006-3

- Viveiros, C. J., & Darling, E. K. (2019). Perceptions of barriers to accessing perinatal mental health care in midwifery: A scoping review. Midwifery, 70, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.011

- World Health Organization. (2017, January). Scalable psychological interventions for people in communities affected by adversity. World Health Organization.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MSD-MER-17.1