ABSTRACT

Background

Up to 2% of all pregnancies result in pregnancy loss between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks’ gestation, which is defined as ‘late miscarriage’. Lack of consensus about definition of viability paired with existing multiple definitions of perinatal loss make it difficult to define the term ‘late miscarriage’. Parents who experience late miscarriage often have had reassuring scan-milestones, which established their confidence in healthy pregnancy progression and identity formation, which socially integrates their baby into their family. The clinical lexicon alongside the lack of support offered to parents experiencing late miscarriage may disclaim their needs, which has potential to cause adverse psychological responses.

Aim

To review what primary research reports about parents’ experiences and their perceived holistic needs following late miscarriage.

Methods

A narrative systematic review was carried out. Papers were screened based on gestational age at time of loss (i.e. between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks’ gestation). The focus was set on experience and holistic needs arising from the loss rather than its clinical care and pathophysiology. Studies were selected using PRISMA-S checklist, and quality assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool. Thematic analysis was used to guide the narrative synthesis of findings.

Results

Six studies met the inclusion criteria. Three main themes emerged: communication and information-giving; feelings post-event; and impact of support provision.

Conclusion

Literature about the experience of late miscarriage is scarce, with what was found reporting a lack of compassionate and individually tailored psychological follow-up care for parents following late miscarriage. Hence, more research in this arena is required to inform and develop this area of maternity care provision.

Introduction

The loss of a baby during pregnancy represents a deeply emotional and traumatic event for women, partners and families (Bilardi et al., Citation2021; Simmons et al., Citation2006). Maternity care is bound by ethical boundaries and in particular age of viability, which is dictated in the UK by law (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, Citation1990), with viability defined by gestational age, fetal weight and signs of life (Pignotti, Citation2010). Between countries, there is no universal consensus regarding fetal viability, with the World Health Organization (WHO) setting the threshold at 22 + 0, and the UK at 24 + 0 weeks’ gestation (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, Citation1990; Quenby et al., Citation2021). Extending from the concept of viability originates a broad vocabulary surrounding definitions, which includes perinatal loss, postnatal death, stillbirth and miscarriage (MBRRACE-UK, Citation2021). Although necessary, such vocabulary may not align with the feelings or expectations of those who are suffering perinatal loss (Cullen et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2020). Consequently, some parents who have their experience labelled as ‘late miscarriage’ may struggle to recognise their experience as ‘fitting’ into a particular category.

Late miscarriage

In the UK, miscarriage is defined as loss of a baby before 24 completed weeks’ gestation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Citation2016), with incidence reported to be around 30% of all pregnancies (Wang et al., Citation2003). Most perinatal losses occur before 13 + 6 weeks’ gestation and are referred to as ‘early miscarriage’ (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Citation2016). In contrast, ‘late miscarriage’ occurs less frequently and is defined as loss of a baby between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks’ gestation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Citation2016), with incidence varying from 0.6% to 2% of all pregnancies (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Citation2016). The experience of visually ‘meeting the baby’ at the first scan instigates early bonding, and can help develop fetal identity and presence as a new member of the family (Ramos Guerra et al., Citation2011; Roberts, Citation2012; Skelton et al., Citation2023). Hence, when miscarriage occurs following one or multiple scans, lack of formal death certification and use of certain terminology may reject established child identity (National Bereavement Care Pathway Scotland, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2020). In particular, failure to acknowledge fetal identity following late miscarriage may contribute towards developing psychological sequelae. With this in mind, the aim was to review what primary research reports about parents’ experiences and their perceived holistic needs following late miscarriage.

Method

A narrative systematic review was carried out to explore what primary research reports about parents’ experiences and holistic needs following late miscarriage. This method was selected to evaluate studies of different methodological nature, with a view to including papers that capture quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods approaches. It was deemed appropriate to perform a literature review in a systematic manner and conduct a narrative synthesis of its findings as described by Popay et al. (Citation2006) (CASP, Citation2018; Noyes et al., Citation2019).

Sampling the literature

Concept mapping was chosen as the starting point in developing the search strategy (Booth et al., Citation2022), with the iterative nature of concept mapping resulting in development of a table of concepts and synonyms ().

Table 1. Concepts and synonyms.

The search strategy was refined according to critical discussion between the primary researcher, two senior researchers and a subject librarian. A final list of inclusion and exclusion criteria was established (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019) (). Specifically, this literature review focused upon:

Pregnancy loss between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks’ gestation, regardless of the lexicon used to describe it (miscarriage, stillbirth or pregnancy loss).

Studies which investigated the experience and needs of parents who suffered such loss and not the physical clinical management or risk factors which may have led to a late miscarriage.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

Electronic searches were performed and updated between 3 November 2021 and 28 March 2023. Searches were performed on relevant bibliographic databases from the platform EBSCOhost: CINAHL with full text, Medline, PsycInfo and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection. The searches on single themes were saved and combined using Boolean operators (), with subsequent searches run through the different databases with necessary adjustments made.

Table 3. Literature search strategy.

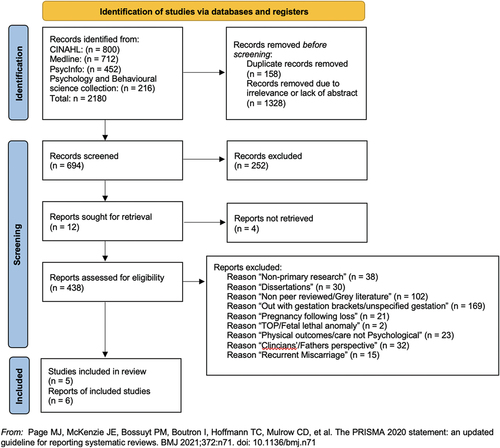

The resulting 2180 studies were further assessed for relevance based on title/abstract and duplicates articles were removed ().

Table 4. Articles found by databases.

Study selection

The remaining articles were further screened by the primary researcher to assess eligibility based on gestational age (between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks of gestation). As a result, a further 252 studies were found not relevant based on title/abstract only. The 442 articles left were assessed by the primary researcher and discussed with two senior researchers in the research team. The screening process is described in .

Table 5. Categories identified from screening process.

To retrieve potential additional relevant articles the reference lists of the studies selected were also screened.

To ensure clarity, validity and auditability of paper selection, the PRISMA-S checklist in conjuction with PRISMA 2020 process was charted (Page et al., Citation2021; Rethlefsen et al., Citation2021), which resulted in development of a PRISMA flow diagram ().

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was chosen to appraise quality of selected studies, because it provides checklists designed to assess both qualitative and quantitative methods (CASP, Citation2022).

The ‘CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist’ was used for five qualitative studies and the ‘CASP Cohort Study Checklist’ for one quantitative study included. The papers selected were found to be of moderate to high quality. All papers adequately articulated the relevance of the topic addressed. Four out of the six papers explicitly stated the aim of the research.

All studies used appropriate methodologies and gained the local ethics committee’s approval. Four out of the five qualitative papers omit to critically evaluate the role of the researcher in relation to the formulation of the study design, the recruitment of participants and the events related to data collection and/or analysis. Only one paper mentions researcher reflexivity practices. Three papers were considered of high quality and three were considered of moderate quality.

Method of narrative synthesis of findings

The narrative synthesis of findings was performed following the steps described by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (Popay et al., Citation2006), which includes:

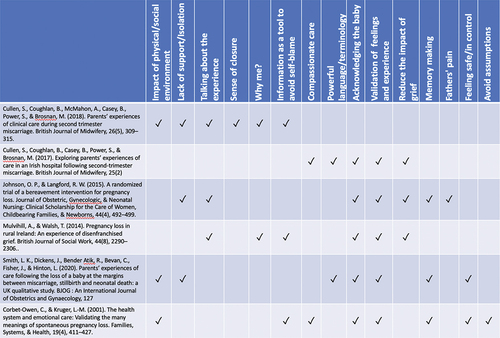

A preliminary synthesis of data in the form of tabulation guided by the CASP checklist ().

A thematic analysis of each study, as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), followed by the exploration of relationships in the data by developing a concept map of emergent themes and a narrative synthesis of findings.

The assessment of robustness of the synthesis, which is obtained by critical reflection on the overall synthesis process and evaluation of study quality.

Results

As reported in the PRISMA flow diagram (), the literature search identified six articles that fitted the set inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these six articles, two represent different reports on the same study. In accordance with CASP guidance, the studies were assessed based on their participants, aims, method, findings and value. Those variables were critically appraised and charted by the primary researcher with the support of two senior researchers. A synthesis of the data reported from the final selected papers is reported in . The tabulation was developed following CASP Qualitative Studies and the CASP Cohort Study Checklist.

Table 6. Appraisal of articles selected following CASP qualitative studies and CASP cohort study checklists.

A synthesis of the participants’ demographic data from the articles selected is reported in .

Table 7. Descripition of participants’ characteristics.

Findings

Findings from each study were analysed and summarised as per the thematic analysis approach described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2022) ().

Figure 2. Thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2022).

After familiarisation with the data and noting ideas, initial codes were generated ().

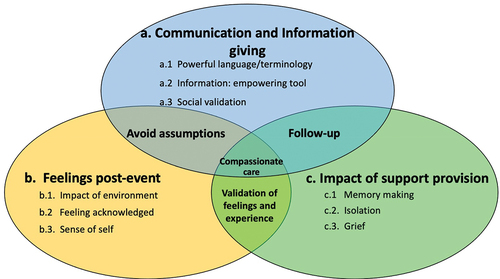

Further analysis established relationships between codes and groupings under overarching themes. Three main themes emerged from the data: communication and information-giving, feelings post-event, and impact of support provision. Given the complex sensitive nature of the topic, some of the core concepts are shared between overarching themes ().

The following narrative synthesis has been structured to relate to the themes identified in the concept map ().

(a) Communication and information-giving

The topic of communication has been raised in all six papers, with reports dichotomous. On one hand, findings highlight quality issues surrounding healthcare professionals’ communication to women and partners, which include: (a.1) their choice and use of terminology and whether this aligned with parents’ need for compassionate care; and (a.2) their ability to effectively inform parents about proceeding events. On the other hand, findings report (a.3) parents’ difficulty in expressing and communicating effectively their feelings and needs to healthcare professionals and also family and friends.

(a.1) Powerful terminology

Examples include healthcare professionals’ use of medical vocabulary.

The use (or misuse) of certain terminology was reported as distressing by some parents. Terms such as ‘product of conception’ (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014, p. 2296), ‘abortion pill’ (Cullen et al., Citation2017, p. 113) and ‘miscarriage’ (Smith et al., Citation2020, p. 870) were statements perceived to be insensitive and incongruous. Smith et al. (Citation2020) report that use of sensitive language which aligns with parents’ perceptions plays a key part in reducing feelings of fear and isolation (Smith et al., Citation2020), avoiding disenfranchised grief (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014) and development of long-term psychological sequelae (Smith et al., Citation2020). Smith et al. (Citation2020) also report that use of sensitive language bestows a sense of candidacy to reach out to support services, which works towards improving both personal and social understanding of what they are experiencing. In addition, being provided with information was viewed as empowering by parents.

(a.2) Information: empowering tool

There is no explanation … all of those questions inside of me … . (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001, p. 420)

Parents highlighted that being given clear information about clinical care provision and reason for their loss worked towards reducing the impact of self-blame and enhanced feelings of being safe and in control (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Cullen et al., Citation2018). In addition, timely provision of information, being given the opportunity to ask questions, and a collaborative approach towards decision-making surrounding care were reported to be key elements in perceptions of ‘feeling heard’ and being provided with the support needed to move forward following loss (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Cullen et al., Citation2018; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020).

(a.3) Social validation

Women and couples reported that lack of understanding from their social circles left them unable to talk about their loss and reduced their feelings of isolation (Smith et al., Citation2020). The following quote emphasises this point:

Nobody called me. Nobody ever called me … I went back to work and nobody mentioned anything. Nobody said anything to me. (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014, p. 2296)

This woman’s need to mourn her loss and have her experience acknowledged and validated clashed with avoidance or downplaying reactions of her family, friends and work colleagues (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). The taboo that surrounds pregnancy loss and being denied the opportunity to talk about it may result in parents experiencing disenfranchised grief and it is associated with longer-term psychological complications (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001). In contrast, parents who experienced support from family and friends found that sharing mementos of their baby provided them with valuable affirmations (Smith et al., Citation2020).

(b) Feelings post-event

Parents’ emotional responses are explored in the literature in relation to the circumstances surrounding ‘late miscarriage’. These include feelings surrounding: (b.1) clinical care provision whilst in hospital; (b.2) acknowledgement of the loss; and (b.3) sense of self.

(b.1) Impact of environment

The physical hospital environment has been reported to affect parents’ feelings and experiences of late pregnancy loss. For example, parents expressed the need to be separated from pregnant women and ‘crying babies’ to circumvent additional distress (Cullen et al., Citation2018, p. 312; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). Others also reported how transitioning from a gynaecological ward to a maternity ward changed their care from ‘being a woman with a pile of tissue in her uterus’ to a ‘pregnant woman with a baby’ (Smith et al., Citation2020, p. 870), which addressed their need to have their loss and baby acknowledged.

(b.2) Feeling ‘acknowledged’

Having the baby and loss acknowledged is a core need recognised within the literature. This is threaded throughout all the described themes, and represents one of the stepping stones in dealing with emotional and psychological consequences of pregnancy loss (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001).

Some women report that having their experience ‘dismissed’ and experiencing a sense that ‘it was as if nothing had happened’ (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001, p. 419) inhibited their ability to speak about their loss. These feelings occurred in relation to both healthcare professionals and family members and led to feelings of disempowerment and isolation (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). In addition, Smith et al. (Citation2020) describe how lack of formal certification of the baby’s death before 24 weeks’ gestation negatively impacted some parents who felt they were being denied their baby’s existence and rights to parental leave and maternity pay. There is consensus in the literature that validating parents’ experiences and feelings facilitates them to grieve and lowers the risk of them developing disenfranchised grief, anxiety and depression (Johnson & Langford, Citation2015; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020).

(b.3) Sense of self

Some women reported a sense of empowerment and fulfilment in being pregnant, which is substituted with feelings of being defective and abnormal following a fetal demise (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). As expressed in the quote ‘your body is so, so cruel’ (Smith et al., Citation2020, p. 871), as motherhood becomes part of personal identity and status in society, the pregnancy loss induces in some women feelings of being powerless and ‘cheated’ by their own body at both a personal and a social level (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020). Hence, clear communication is an essential part of re-establishing women’s sense of feeling both safe and in control. Some primiparous women who were gestationally too early to attend antenatal classes felt unprepared for their labour and birth. However, these women reported feeling reassured and cared for when healthcare professionals took time to explain how labour and birth would feel, and what options would be available for pain relief (Cullen et al., Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2020). Hence, the opportunity to be their own storyteller, rather than being assessed only on the basis of their physical symptoms, and being listened to with sensitivity and empathy by healthcare professionals, helped them to feel safe and in control (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001, p. 419; Cullen et al., Citation2017).

(c) Impact of support provision

Another key point identified in the literature is the need for parents to feel supported. Quality support provision should essentially be offered to all women, partners and families as emphasised in the following quote:

It’s hard to ask for support isn’t it … I think it’s easier to accept the offer than to go look for it yourself. (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014, p. 2297)

As support provision is not an all-encompassing formula that can be ‘applied’ to all, parents are advocating for healthcare professionals to empathetically listen and respond to their personal support needs, and refrain from making assumptions (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Smith et al., Citation2020). The studies included in this theme, explored under different lenses aspects of (c.1) memory-making, (c.2) isolation and (c.3) grief.

(c.1) Memory-making

Memory-making consists of both the opportunity for parents to spend time with their baby, and the creation and collection of keepsakes by which to remember the baby. Parents responded positively to the guidance of midwives in relation to creating mementos. For example, some parents reported that being provided with an opportunity to see pictures of their baby before meeting them prepared and reassured them about what to expect (Smith et al., Citation2020). Similarly, others appreciated when midwives took pictures of their baby and stored them in the case notes, thus providing an opportunity for future viewing should they change their mind (Cullen et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2020). Conversely, other parents expressed frustration and anger when they were denied an opportunity to create memories (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020), with the quote that follows illustrating such feelings:

It nearly drove me insane that I never saw that baby. (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001, p. 422)

As such, memory-making represents a tool to validate the baby’s existence and establishes identity of both the ‘lost child’ and the woman and partner’s roles as ‘parents’ (Cullen et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, lack of mementos is reported to play a part in parents developing responses, such as complicated or disenfranchised grief (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020).

(c.2) Isolation

Although most parents report having received empathetic and sensitive care whilst in the hospital, some reported receiving lack of emotional and/or psychological support once discharged home (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). Signposting parents towards opportunities to connect with peers or support groups who have experienced similar situations, may help to ease their sense of isolation and play a role in processing loss of their baby (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001). In one account from Mulvihill and Walsh (Citation2014), a woman describes how follow-up support can help:

‘[it] shows that you are not just a number, you are a person and you’re going to be looked after’. (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014, p. 2297)

Some bereaved parents benefit from tailored follow-up designed to meet their individualised needs, which may include a schedule of phone calls and/or home visits (Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014). Parents interviewed in the Mulvihill and Walsh (Citation2014) study go as far as defining an ideal timeframe that involves a scheduled appointment 2-months post-loss, which provides sufficient time for parents to process their emotions and also represents a time when family and friends’ support starts to naturally diminish.

(c.3) Grief

The term ‘grief’ in a perinatal bereavement context is defined as a dynamic physiological process, which includes ‘psychological, behavioural, social, and physical reactions’ following the loss of a baby (Hollins Martin & Martin, Citation2016, p. 603). In order to reduce the impact of grief, it is important for parents to progress straightforwardly through natural stages. Kübler-Ross (Citation1969) describes the grieving process in five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance, which represents keynote literature on the psychoanalysis of grief. During the process, failure to naturally progress through these stages of grief can lead to pathologies, such as postnatal depression or complicated grief (Hollins Martin & Martin, Citation2016).

Empathy and sensitivity are described as instrumental tools for alleviating pain from a second-trimester loss, which may impact parents’ longer-term ability to adjust throughout the stages of grieving (Cullen et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2020). Johnson and Langford (Citation2015) highlight how women who receive quality emotional bereavement care show reduced levels of grieving and despair. In their study, despair is defined as a maladaptive response during the grieving process. Given that follow-up consisted of a 15-minute telephone call 2-weeks post-loss, it could be argued that ‘a little goes a long way’. In response, implementation of bereavement protocols which schedule quality follow-up may work towards enhancing the ‘emotional healing’ of those experiencing pregnancy loss (Johnson & Langford, Citation2015).

Discussion

The body of literature that has investigated parents’ experiences of perinatal loss, which includes miscarriage, stillbirth and postnatal death, has grown significantly in the last two decades (Farren et al., Citation2018). However, there is a paucity of studies that have explored parents’ psychological needs post experiencing late or second-trimester miscarriage. Out of the 6 papers retrieved, only 3 specifically investigated parents who had experienced loss between 14 + 0 and 23 + 6 weeks of gestation (Cullen et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2020). The other three studies assessed the effects more broadly and used the terms ‘miscarriage’ or ‘perinatal loss’, with gestations at time of loss varying from 8 to 32 weeks; within this bracket, more than 50% of participants were referred to as having experienced a late miscarriage (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Johnson & Langford, Citation2015; Mulvihill & Walsh, Citation2014).

The arising psychological needs surrounding ‘late miscarriage’ are similar to those related to miscarriage in its broader definition, with the findings of this narrative literature review validated by another literature review that focused on women who had experienced miscarriage up to 20 weeks’ gestation Robinson (Citation2014). Robinson (Citation2014) also describes the impact of information provision, acknowledgement of loss and use of appropriate medical terminology, as protective factors against developing psychological complications; for example, complicated grief and/or depression. Clearly, and in relation to miscarriage, the need for support is highlighted by many researchers (Lok & Neugebauer, Citation2007; Robinson, Citation2014), and there seems to be inconsistency in actual uptake of available interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and peer support (Robinson, Citation2014; Séjourné et al., Citation2010). The hesitance in partaking in support interventions could be particularly significant in reference to parents who have experienced late miscarriage. Within the framework of attachment theory, it is suggested that the use of ultrasound scanning intensifies parental−fetal bonding, and particularly during the second trimester (Righetti et al., Citation2005). Also, parents who suffer second-trimester loss may have had multiple scans before the fetal demise. As such, health care professionals may anticipate differences in the incidence of psychological complications and engagement with support services within this group (Lok & Neugebauer, Citation2007). Emphasising this point about engagement with support services, the literature highlights that parents who have experienced late miscarriage often wrestle with the idea of joining support groups specifically focussed upon either miscarriage or stillbirth, simply because they struggle to identify their own loss as fitting into either of these groups (Smith et al., Citation2020).

The topic of follow-up support following late miscarriage arises in all six papers identified and is also mentioned in the Robinson (Citation2014) review. Parents appreciate being given information about their loss and the possible reasons why it might have occurred, straightforwardly, because it represents a way to validate and make sense of their experience (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Cullen et al., Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2020). Parents also report lack of routine emotional and psychological follow-up support from local health services, along with a failure to effectively signpost available support organisations and/or counselling services. These findings are echoed in a study about support provision for women following miscarriage by Bilardi et al. (Citation2021), which reports that more than half of women are not offered information about available support options, nor actual follow-up emotional or psychological care post-loss, despite stating that they would have liked this. Evidence of reported ‘practice mismatch’ between what women desire in terms of support and type of care they receive (Bilardi et al., Citation2021) is corroborated by findings of the Robinson (Citation2014) study about follow-up care provided post-late miscarriage.

A Cochrane review by Murphy et al. (Citation2012) about the efficacy of providing psychological support post-miscarriage concludes that there is insufficient evidence to confirm that support provision is effective at reducing pathological sequelae (e.g. anxiety, depression and complicated grief). Also, as the Murphy et al. (Citation2012) Cochrane review included studies with largely different datasets, they suggest that further research is required. In addition, a recommendation is made that those who have experienced miscarriage should guide the development of design and the assessment of future support services (Murphy et al., Citation2012).

In addition, Kong et al. (Citation2014) suggest that psychological counselling should be offered to a selected group of women at high risk of developing psychological morbidity. A review of 27 studies conducted by Farren et al. (Citation2021) concludes that women who receive less support and/or have a history of psychiatric illness, recurrent pregnancy loss, or infertility, and/or who are left childless following loss, are at higher risk of developing symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following early pregnancy loss.

Working on the premise of avoiding assumptions and the requirement that every woman should receive person-centred care, differences may be drawn regarding the subgroup of women who have suffered late miscarriage. The literature retrieved highlights a need for providing compassionate emotional care following a second-trimester loss. Parents interviewed by Mulvihill and Walsh (Citation2014) expressed a desire to receive routine emotional care, which is initiated whilst in hospital and followed-up with phone contact and/or home visits especially around 2 months post-loss. In response, Tseng et al. (Citation2017) found a significant decrease in levels of grief from 3 to 6 months following perinatal loss, which suggests that routine follow-up care could be beneficial in this particular time period.

Implications for future research

This literature review reveals a paucity of investigations that have addressed women’s and their partners’ experiences of late miscarriage. It has been ascertained that most of the literature that focuses on the topic of pregnancy loss gathers the event ‘late miscarriage’ under the umbrella of miscarriage or perinatal loss. Although some themes that have emerged from the literature about miscarriage and stillbirth are mutual, there are aspects distinctive to the experience of late miscarriage, which have been overlooked in both clinical and social contexts. These aspects include the use of particular terminology and lack of acknowledgement of loss, which includes memory- making and formal certification and a lack of tailored emotional support. Neglecting these aspects of psychological care may impact parents’ interest in engaging with follow-up support, which in turn may increase the risk of developing psychological morbidity (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, Citation2001; Smith et al., Citation2020). This review emphasises the need to implement compassionate, timely and effective emotional/psychological follow-up support post-late miscarriage, which are points highlighted in the latest guidelines for healthcare professionals developed by the National Bereavement Care Pathway Scotland (Citation2020). However, these guidelines omit to detail who should take charge of planning and delivery of follow-up support, and how the services should work towards effectively addressing the needs of those affected by perinatal loss. Also, in order to deliver high-quality person-centred care, personnel involved in delivering perinatal bereavement care require appropriate training in how to provide compassionate care (Beaumont & Hollins Martin, Citation2016; Cullen et al., Citation2017; Hollins Martin et al., Citation2021).

In addition, the results of this literature review illustrate that further qualitative research is required to investigate the support needs of parents who have suffered late miscarriage, which would inform the implementation of training resources in compassionate care for healthcare professionals (Hollins Martin et al., Citation2021). Also, the development of a compassionate follow-up support service that effectively addresses the specific needs of parents who have experienced late miscarriage could be of benefit (Beaumont & Hollins Martin, Citation2016).

Implications for practice

As evidence remains insufficient regarding the needs and follow-up care appropriate for parents who have suffered a late miscarriage, clinicians and individuals involved in providing care should be aware of the uniqueness of this experience, the importance of sharing information about the loss, and be compassionate and responsive to women’s preferences and signpost them to available support services.

Limitations

One limitation of this review is that only three articles included investigated ‘late miscarriage’. Due to differences in defining categories of perinatal loss in terms of gestational age, this means that part of the data utilised may originate from parents who have sustained a perinatal loss within a different gestational bracket. Additionally, there is an abundance of articles about perinatal loss and miscarriage that do not report gestational age at time of loss, and because of this lack of focus they were excluded from the review. Nonetheless, this review has reported new findings, which the conclusion now summarises.

Conclusion

This review has identified three aspects of parental dissatisfaction with care provision following the experience of late miscarriage, which include: (a) communication and information given; (b) feelings post-event; and (c) impact of support provision. Also, this review has highlighted a dearth of compassionate, tailored, emotional and follow-up psychological care, which implies that the development of specific late miscarriage support services is required. A recommendation is also made that more in-depth, high-quality, qualitative research that focuses on the needs of parents who have experienced late miscarriage would appropriately inform both training needs in bereavement care and the development of more effective follow-up support services, as is advocated by the Murphy et al. (Citation2012) Cochrane review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beaumont, E., & Hollins Martin, C. J. (2016). Heightening levels of compassion towards self and others through use of compassionate mind training. British Journal of Midwifery, 24(11), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2016.24.11.777

- Bilardi, J. E., Sharp, G., Payne, S., & Temple-Smith, M. J. (2021). The need for improved emotional support: A pilot online survey of Australian women’s access to healthcare services and support at the time of miscarriage. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(4), 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.011

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Martyn-St James, M., & Booth, A. (2022). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

- CASP. (2018). Making sense of evidence: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- CASP. (2022). What is critical appraisal? https://casp-uk.net/what-is-critical-appraisal/

- Corbet-Owen, C., & Kruger, L.-M. (2001). The health system and emotional care: Validating the many meanings of spontaneous pregnancy loss. Families, Systems, & Health, 19(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089469

- Cullen, S., Coughlan, B., Casey, B., Power, S., & Brosnan, M. (2017). Exploring parents’ experiences of care in an Irish hospital following second-trimester miscarriage. British Journal of Midwifery, 25(2), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2017.25.2.110

- Cullen, S., Coughlan, B., McMahon, A., Casey, B., Power, S., & Brosnan, M. (2018). Parents’ experiences of clinical care during second trimester miscarriage. British Journal of Midwifery, 26(5), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2018.26.5.309

- Farren, J., Jalmbrant, M., Falconieri, N., Mitchell-Jones, N., Bobdiwala, S., Al-Memar, M., Tapp, S., Van Calster, B., Wynants, L., Timmerman, D., & Bourne, T. (2021). Differences in post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy between women and their partners: Multicenter prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 57(1), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.23147

- Farren, J., Mitchell-Jones, N., Verbakel, J. Y., Timmerman, D., Jalmbrant, M., & Bourne, T. (2018). The psychological impact of early pregnancy loss. Human Reproduction Update, 24(6), 731–749. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmy025

- Hollins Martin, C. J., Beaumont, E., Norris, G., & Cullen, G. (2021). Teaching compassionate mind training to help midwives cope with traumatic clinical incidents. British Journal of Midwifery, 29(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2021.29.1.26

- Hollins Martin, C. J., & Martin, C. R. (2016). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and its relationship with perinatal bereavement: Definitions, reactions, adjustments, and grief. In C. R. Martin, V. R. Preedy, & V. B. Patel (Eds.), Comprehensive guide to post-traumatic stress disorders (pp. 599–626). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08359-9_44

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act. (1990).

- Johnson, O. P., & Langford, R. W. (2015). A randomized trial of a bereavement intervention for pregnancy loss. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 44(4), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12659

- Kong, G. W. S., Chung, T. K. H., & Lok, I. H. (2014). The impact of supportive counselling on women’s psychological wellbeing after miscarriage – A randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 121(10), 1253–1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12908

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Routledge.

- Lok, I. H., & Neugebauer, R. (2007). Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.007

- MBRRACE-UK. (2021). UK Perinatal deaths for births from January to December 2019. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/perinatal-surveillance-report-2019/MBRRACE-UK_Perinatal_Surveillance_Report_2019_-_Final_v2.pdf

- Mulvihill, A., & Walsh, T. (2014). Pregnancy loss in rural Ireland: An experience of disenfranchised grief. The British Journal of Social Work, 44(8), 2290–2306. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct078

- Murphy, F. A., Lipp, A., & Powles, D. L. (2012). Follow-up for improving psychological well being for women after a miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD008679. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008679.pub2

- National Bereavement Care Pathway Scotland. (2020). Miscarriage, ectopic and molar pregnancy bereavement care pathway. https://www.nbcpscotland.org.uk/media/wgobocib/nbcp-scotland-mem-pregnancy-mar2020-v1-2.pdf

- Noyes, J., Booth, A., Moore, G., Flemming, K., Tunçalp, Ö., & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: Clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Global Health, 4(Suppl 1), e000893. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000893

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Pignotti, M. S. (2010). The definition of human viability: A historical perspective. Acta Pædiatrica, 99(1), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01524.x

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf

- Quenby, S., Gallos, I. D., Dhillon-Smith, R. K., Podesek, M., Stephenson, M. D., Fisher, J., Brosens, J. J., Brewin, J., Ramhorst, R., Lucas, E. S., McCoy, R. C., Anderson, R., Daher, S., Regan, L., Al-Memar, M., Bourne, T., MacIntyre, D. A., Rai, R., Christiansen, O. B., … Coomarasamy, A. (2021). Miscarriage matters: The epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. The Lancet, 397(10285), 1658–1667. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00682-6

- Ramos Guerra, F. A., Mirlesse, V., & Rodrigues Baiao, A. E. (2011). Breaking bad news during prenatal care: A challenge to be tackled. Ciência & Saude Coletiva, 16(5), 2361–2367. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000500002

- Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., Koffel, J. B., Blunt, H., Brigham, T., Chang, S., Clark, J., Conway, A., Couban, R., de Kock, S., Farrah, K., Fehrmann, P., Foster, M., Fowler, S. A., … Wright, K. (2021). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 39–39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

- Righetti, P. L., Dell’avanzo, M., Grigio, M., & Nicolini, U. (2005). Maternal/paternal antenatal attachment and fourth-dimensional ultrasound technique: A preliminary report. British Journal of Psychology, 96(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712604X15518

- Roberts, J. (2012). ‘Wakey wakey baby’: Narrating four‐dimensional (4D) bonding scans. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34(2), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01345.x

- Robinson, J. (2014). Provision of information and support to women who have suffered an early miscarriage. British Journal of Midwifery, 22(3), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2014.22.3.175

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2016). Early miscarriage. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/patient-leaflets/early-miscarriage/

- Séjourné, N., Callahan, S., & Chabrol, H. (2010). The utility of a psychological intervention for coping with spontaneous abortion. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 28(3), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903487334

- Simmons, R. K., Singh, G., Maconochie, N., Doyle, P., & Green, J. (2006). Experience of miscarriage in the UK: Qualitative findings from the National Women’s Health Study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 63(7), 1934–1946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.024

- Skelton, E., Smith, A., Harrison, G., Rutherford, M., Ayers, S., Malamateniou, C., & Spradley, F. T. (2023). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK parent experiences of pregnancy ultrasound scans and parent-fetal bonding: A mixed methods analysis. PLoS One, 18(6), e0286578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286578

- Smith, L. K., Dickens, J., Bender Atik, R., Bevan, C., Fisher, J., & Hinton, L. (2020). Parents’ experiences of care following the loss of a baby at the margins between miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: A UK qualitative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 127(7), 868–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16113

- Tseng, Y. F., Cheng, H. R., Chen, Y. P., Yang, S. F., & Cheng, P. T. (2017). Grief reactions of couples to perinatal loss: A one‐year prospective follow‐up. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 5133–5142. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14059

- Wang, X., Chen, C., Wang, L., Chen, D., Guang, W., & French, J. (2003). Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: A population-based prospective study. Fertility and Sterility, 79(3), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04694-0

- Xiao, Y., & Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971