ABSTRACT

Aims

To determine what kinds of birth-related experiences of success and failure are described by the participants, and whether there are differences according to fear of childbirth and parity. Studying these experiences is important for understanding the psychological mechanisms behind different childbirth experiences and their impact on maternal mental well-being.

Methods

This was a longitudinal mixed methods study. Descriptions of the birth experiences of 113 Finnish participants were gathered in a survey at 4–8 weeks postpartum and analysed with content analysis. Fear of childbirth was determined antenatally with the Wijma Delivery Expectations scale (W-DEQ A).The number of success and failure expressions were compared between people with FOC and others and between primiparous and multiparous people.

Results

The contents of the childbirth-related experiences of success and failure were categorised into 12 subcategories, organised under three higher-order categories that were named personal factors, course of childbirth, and support. The most typical expressions of success were in the categories of mode of birth, staff, and mental factors, and the most typical expressions of failure in the categories of staff and mental factors. Experiences of failure were more often expressed by primiparous than multiparous people, but there were no statistically significant differences by FOC. Expressions of success were equally common regardless of parity or FOC.

Conclusion

Postpartum people categorise aspects of their birth experiences in terms of success and failure. Primiparous people are more susceptible to experiencing failure at childbirth, but possible differences between people with FOC and other people warrant further investigation.

Introduction

The experience of childbirth has been defined as a significant life event including subjective psychological, physiological, social, political, and environmental aspects (Larkin et al., Citation2009). The quality of the experience has been found to be important for maternal postpartum well-being, such as mental health (Coo et al., Citation2023) and bonding with the baby (Reisz et al., Citation2015). However, most studies have approached childbirth experiences through general evaluations or questionnaires combining different aspects of the experience, without focusing on the meaning individuals attach to their evaluations. Viirman et al. (Citation2023) propose that overall ratings of birth experiences seem to mostly capture perceptions of safety and underestimate other aspects, such as own capacity, participation, and professional support. However, different dimensions in the overall experience may differently affect well-being. For example, perceptions of having failed or being less capable than expected may lead to postpartum depression, and perceptions of being successful may support good self-esteem and maternal adjustment. Indeed, birth experiences can also include perceptions of successes and failures, and they may have important consequences for the mother. However, while birth experiences are widely studied in general, research on success and failure in childbirth is scant (see, however, Kjerulff & Brubaker, Citation2017; Schneider, Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2018). By investigating these aspects of birth experiences, it is possible to better understand meaning-making of the experience, as well as maternal postpartum well-being.

Previous research suggests that experiences of birth are multifaceted. A positive birth experience is important for the welfare of the person giving birth, the baby, and the whole family (Reisz et al., Citation2015; Taheri et al., Citation2018). A good birth experience is related, among other factors, to obstetric, social, and organisational factors, such as an uncomplicated birth and empathetic and continuous care (McKelvin et al., Citation2020), which promote a sense of safety and enhance feelings of control and agency (Karlström et al., Citation2015). Trust in one’s own competence is part of a positive birth experience (Karlström et al., Citation2015), and a very positive birth experience involves a sense of empowerment and daring (Olza et al., Citation2018).

Risk factors for negative childbirth experiences include obstetric events, especially emergency caesareans (Chabbert et al., Citation2020), and negative interactions with professionals and perceived lack of support (McKelvin et al., Citation2020). Obstetric complications and interpersonal difficulties are often the most distressing aspects of birth (Harris & Ayers, Citation2012), but prenatal expectations that are not realised may also negatively affect the experience (Kringeland et al., Citation2009; Lally et al., Citation2008; Preis et al., Citation2019). A negative or traumatic experience can have long-lasting effects on the well-being of the birthing person (Ayers et al., Citation2006; Harris & Ayers, Citation2012; Molgora et al., Citation2020).

Experiencing some aspects of birth as failures may be influenced by severe fear of childbirth (FOC), which is one of the most well-known risk factors for a negative birth experience (Elvander et al., Citation2013). It affects approximately 11% of pregnant people (Nilsson et al., Citation2018) and can also be experienced by those who are not and never have been pregnant (Rondung et al., Citation2022). The fear is commonly related to pain and complications (Eriksson et al., Citation2006) and lack of trust towards professionals or towards one’s own ability to give birth (Eriksson et al., Citation2010). Recent theorising on fear of childbirth suggests that the individual causes and content of fear should be better acknowledged and individualised support should be developed (O’Connell et al., Citation2021) to meet the needs of people experiencing such fear.

Birth experiences may also be qualitatively different for primiparous and multiparous people (Malacrida & Boulton, Citation2012). Primiparae more often feel that their birth expectations are not met, while multiparae, based on previous experiences, may have adjusted their expectations so that they are likely to experience the next birth more positively (Hauck et al., Citation2007). Multiparae are also more likely to have a natural birth if they expect it (Kringeland et al., Citation2010), even though achieving an ideal birth may be more important for primiparous people (Malacrida & Boulton, Citation2012).

While research on general birth experiences may provide useful information on the overall experience, research directly concentrating on experiences of success and failure in childbirth is needed to better understand the meaning of the experiences and their effects on maternal well-being. Kjerulff and Brubaker (Citation2017), specifically exploring feelings of failure or pride in childbirth, found that women who had an unplanned caesarean birth were five times more likely to feel like failures in comparison to those who had a spontaneous vaginal birth; and less likely to feel extremely or quite a bit proud of themselves. However, in Schneider’s (Citation2010) qualitative survey study, 60% of participants reported feelings of failure regarding their births when directly asked. Vaginal birth could also include feelings of failure, and the participants most often attributed the blame of these failures to themselves. Indeed, expectations for a successful birth may be influenced by ideologies such as natural birth, which promote a certain type of birth as favourable and require self-control (Chadwick & Foster, Citation2013). In addition, different versions of such birth ideologies may exist (Macdonald, Citation2006) and, for example, effective pain relief may represent success to one person but failure to another. Birth experiences can also be internally contradictory, with some aspects interpreted as positive and others as negative (Choi et al., Citation2005; Malacrida & Boulton, Citation2012).

More research on success and failure experiences is needed, especially differentiated by fear of childbirth and parity. Therefore, the aims of the present study were as follows: to determine what kinds of birth-related experiences of success and failure are described by the participants, and whether there were differences in the experiences of success and failure according to fear of childbirth and parity. No previous study has investigated failures and successes in the same study. By exploring those experiences, valuable information can be obtained about the evaluation of childbirth events and variations in individual meaning-making and cultural ideals of birth. The results will contribute to understanding the possible implications of birth experiences: In the short term, success or failure experiences in birth may determine the emotional quality of the first days and weeks of motherhood and affect adjustment to parenting. In the long term, they may contribute to explaining why some people develop postpartum depression or anxiety and how this may be related to childbirth experience. The findings will help open new avenues in preventing and caring for negative experiences, which may reduce the negative impacts of such experiences on maternal, child, and family well-being.

Materials and methods

Participants

The participants were recruited from antenatal maternity services in four cities in Finland. In this area, there were 2,754 births in 2020. The due dates of the participants were February to October 2020. Eligibility criteria included being at 30+ gestation weeks and the ability to complete the questionnaires in Finnish. Participants were 22 to 44 years old (M = 31.1 SD = 4.46), 59.3% of them were primiparous, and 40.7% were multiparous. Participants were more often primiparous than pregnant Finnish women on average and had a higher education than Finnish women on average. Details of the sample are presented in .

Table 1. Background characteristics of the sample (N = 113).

Procedure

Ethical approval for the study was obtained before data collection from the Ethics Committee of the relevant university (August 2019). The study was longitudinal with two phases, including surveys in pregnancy (gestational weeks 30+; Phase 1) and postpartum (4–8 weeks, phase 2). The purpose of the longitudinal design in the overarching research project was to investigate developmental pathways throughout the transition to motherhood. The first survey included questions on background variables (family type, number of children, income level, education, age), fear of childbirth, couple relationship (if applicable), self-esteem, depression, and parental burnout (for those participants who already had children). The second phase survey included the same questions except background information, as well as questions on birth experience. Family health centres at four Finnish municipalities agreed to participate in data collection, and public health nurses presented the study to the participants during their antenatal appointments. Later phase surveys were sent directly by mail to the participants who had participated in the first phase. The data were collected in 2020–2021. All participants filled in the surveys and a consent form and sent them to the researchers in a pre-paid envelope. In the first phase, 125 people (25.4%) agreed to participate. A total of 90.4% of the participants (n = 113) in the first phase of the study also participated in the second phase (4–8 weeks postpartum). For the purposes of the present study, background information and fear of childbirth included responses from Phase 1, and birth experience was asked about at Phase 2.

Data collection

Experiences of success and failure were examined on the basis of answers to the open-ended question ‘What kind of experience was childbirth for you? Describe freely’. This was the fifth question of the survey in the second phase of the study, and it was the first of the questions targeting childbirth experiences. All participants (n = 113) answered this question. The length of the responses ranged from 1 to 171 words (M = 61).

Fear of childbirth was measured antenatally (in the first phase of the study) with the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire – version A (W-DEQ-A, Wijma et al., Citation1998). The W-DEQ-A contains 33 Likert scale questions on a visual scale, including six main themes such as ‘How do you think you will feel during delivery?’ with statements such as ‘0 = Really lonely, 5 = Not lonely at all lonely’. Sum scores of the W-DEQ-A range from 0–165 and higher scores represent higher FOC. Cutoff scores for FOC were determined as follows: severe ≥ 85, high 66–85, moderate 38–65, and low ≤ 37 (Zar et al., Citation2001). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was excellent, .92.

Analysis

This was a mixed methods study with a triangulation design and two-phase approach for data analysis (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011). First, content analysis was used to analyse experiences of success and failure in descriptions of birth experiences. With this method, it was possible to describe the phenomenon in a concise and comprehensive manner (Krippendorff, Citation2018). The analysis was conducted by the first author, who also kept an audit trail to keep track of analytical decisions, reflect on her own thoughts and feelings, and recognise possible bias. Analytical decisions were discussed between both authors throughout the process. Disagreements between authors concerned levels of classification, and they were resolved through discussions until consensus was reached. In these discussions, the context of the specific unit of classification, the entire classification system, and theoretical views on birth experiences were considered.

A times to get an understanding about the whole data set. The qualitative data was transferred to a word processing program (Microsoft Word). Answers were numbered, and these numbers were retained throughout the content analysis so that information of each participant’s parity and FOC scores could be correctly encoded in the quantitative analysis. Encoding that information at this stage could have influenced the first author’s interpretations in the content analysis. Second, the relevant units of analysis (words, sentences, or parts of sentences) were identified and encoded with a colour using the definitions of the Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish (Citation2022a; Citation2022b) about successFootnote1 and failureFootnote2 as the guidelines of coding. The expressions that conveyed an understanding of success or failure, following the dictionary definitions, were identified as relevant units. Other expressions were assumed to be neutral in terms of success or failure. Third, some of the longer units of analysis (n = 438) were simplified (i.e. shortened to contain the main idea), if necessary, and assembled for the grouping stage. At this stage, the expressions were arranged according to similar contents, such as those related to pain, in one group. The grouping became more precise as the analysis progressed. For example, among expressions related to pain could be found expressions related to tolerance for pain, pain relief and intensity and quality of pain, which were grouped separately. Finally, the subcategories were grouped according to what unifying factor the subcategories had. Thus, three (n = 3) higher-order categories were formed. The answers of two participants were left out of the analysis because the answers were short, and experiences of success or failure could not be deduced from them. Both missing answers come from multiparous participants, one of them with a moderate FOC, the other with a low FOC.

Quantitative analysis was used to answer the second research question, as it can increase the clarity and validity of findings (Grbich, Citation2012). In this phase, the participants’ FOC scores (sum scores of the W-DEQ A; antenatally measured) and information about parity were connected with each unit of analysis. We included information on FOC severity (low, moderate, high, and severe) and a dichotomous parity indicator (primiparous/multiparous) in the units of analysis. The distribution of success and failure experiences was examined by frequency and as a percentage in the subcategories formed in the content analysis, and by FOC and parity. In this phase, numbers of expressions in all subcategories were calculated in total and by FOC severity and parity. Finally, the total expressions of success and expressions of failure were calculated by FOC severity and parity. Differences between primiparous and multiparous participants, and between participants with FOC and other participants, were assessed with an independent samples t test. We expected primiparous participants and those with FOC to be over-represented in expressions of failure and underrepresented in expressions of success.

Results

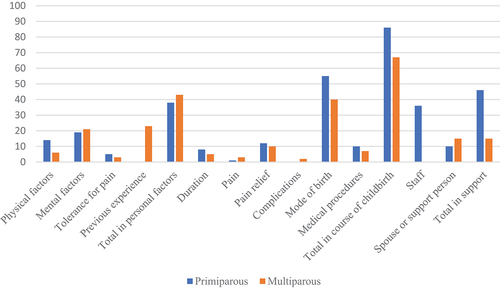

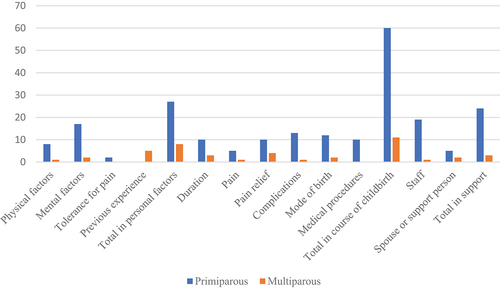

The first aim of this study was to determine what kinds of birth-related experiences of success and failure are described by the participants. Twelve subcategories were identified to capture the participants’ descriptions of success and failure in their birth experiences. The participants described both positive and negative evaluations of their performance and birth-related factors within the same categories, and often the same participants expressed both aspects of success and failure in their descriptions. Three higher-order categories were formed from the twelve subcategories: personal factors, the course of childbirth, and support. One overarching category, diversity of childbirth, encapsulated all categories. This overarching category included all the variation that could be seen within and between individuals: A person’s overall childbirth experience could involve mixed perceptions of successes and failures, and different people could perceive similar aspects of birth differently, with some describing them as successes and others as failures. Overall, more experiences of success were described (n = 305) than experiences of failure (n = 133). All categories are summarised in . A graphical representation of the numbers of success and failure experiences are displayed in . The main elements of each subcategory are described below. The qualitative data was anonymised, and pseudonyms were created for participants to ensure anonymity. Data examples were translated into English by the researchers for the purpose of reporting.

Table 2. Hierarchical structure of the categories.

Personal factors

This category included four subcategories, named physical factors, psychological factors, tolerance for pain, and previous experiences of childbirth. The quotes to illustrate the findings can be found in . Some quotes have been shortened due to readability and for emphasis of relevant information.

Table 3. Examples of quotes.

In physical factors, the participants most often described their physical ability in the second stage of labour and strength during the birth. Surviving without need for help and giving birth ‘with one’s own strength’ was presented as a success by the participants, whereas fatigue or having experienced an assisted birth was described as a failure. Some participants attributed these factors entirely to themselves, while some described others’ support and encouragement as positively affecting their physical endurance. Anni (primipara, moderate FOC) described an experience of failure linked to her physical qualities. Anni’s description () reflected an outcome that differed from her expectations and was presented as caused by her own (poor) performance during the second stage of labour. Anni’s description also reflected the social context – a failure of fulfilling the expectations of others. In her description, a strong expectation for a vaginal birth without assistance seems to be present.

The sub-category of psychological factors included, when successful, descriptions of excitement, self-confidence, a sense of control and concentration. Some participants also described feelings of happiness or love for the child, and how the birth experience facilitated those feelings. On the contrary, failures in this category were presented as not experiencing the positive emotions that were expected to be part of a good birth or falling short of much-needed psychological characteristics such as hardiness and courage, to endure a challenging birth. Jenna’s (primipara, moderate FOC) description showed a successful experience of psychological factors. Jenna described the feeling of self-confidence that helped her during childbirth, even contrary to obstetricians’ predictions. Trust in oneself seems to have played an important role, so that Jenna succeeded in giving birth as she wanted, which resulted in feeling ‘victorious’. This suggests that Jenna had been fighting with the personnel, emerging victorious from that battle.

The participants described their tolerance for pain in relation to antenatal expectations of pain: they tolerated pain better or worse than expected. A good tolerance for pain created a sense of empowerment for some participants, and for some it increased their sense of control. In contrast, some participants were disappointed with their poorer-than-expected pain tolerance. In Roosa’s (primipara, moderate FOC) description, the experience of success was attributed to pain tolerance: Roosa implied that the feeling of empowerment resulted from her good performance and having learned voice techniques that helped her endure the pain without analgesia.

Most multiparae (60.9%) compared their experiences with previous birth experiences, either by the successful completion of some factors of the latest birth or by stating that they still had not had a fully successful experience. Maarit (multipara, low FOC) described that she experienced a very successful birth, which included several corrective experiences: midwives’ professionalism and interaction, success of pain relief, her own body and behaviour, and the duration of the labour. Maarit also described the birth event from her spouse’s point of view, which was exceptional in the data.

The course of childbirth

This category encompassed six subcategories: duration of labour, pain, pain relief, complications, mode of birth, and medical procedures during birth. The quotes to illustrate the findings can be found in .

Table 4. Examples of quotes.

In general, a short duration of birth was experienced as part of a successful birth experience but the individuality of experiences applied in this theme as well. While a quick birth exceeded the expectations of most participants, for others it meant a chaotic experience. In Outi’s (multipara, moderate FOC) experience, a quick birth contributed to loss of control: she would have needed more time to adapt to the stages of childbirth, and she did not feel supported by the midwife. However, she described her own processing of the situation as helpful shortly after childbirth. Failures in this category were generally associated with very long labours.

In relation to pain, there were different points of view: some described pain as paralysing them, whereas others described how even severe pain was not overwhelming for them. The severity and nature of the pain surprised some participants. The description of pain was the main content of Jenna’s (primipara, moderate FOC) experience and it can be interpreted as a determining quality of a negative experience. She described her antenatal expectations as failing as the labour was more painful.

The participants described their expectations of pain relief and assessed the pain relief received. Different experiences were observed in this subcategory. For some, the need for pain relief represented failure, whereas for others, a successful experience was partly formed by receiving all possible pain relief. Kiia’s (multipara, moderate FOC) experience positively differed from her expectations. She described childbirth as empowering because she did not need medical pain relief, and this represented a better performance than expected. Her empowerment appeared to be created by this unexpected success (‘I didn’t think I could do it, and still, I could!’) that she had not believed would be possible for her.

Some participants described fear of and concern for complications. These expressions included having tears in childbirth and concern about the baby or complications for it, which negatively influenced the quality of the birth experience. For some participants, minor complications were not a bother, and some described ‘luckily avoided’ complications – successes in this category were formed by negation, that is, no complications. Maria (primipara, severe FOC) described severe complications and acute concern for the baby’s health in an emergency. Maria described how, while writing about the experience, she still experienced being psychologically stuck in the situation and experiencing feelings of worry. She also described the consequences of a birth injury for her mood and for everyday functioning. Maria’s experience can be interpreted through traumatisation: worries for the baby and the birth injury seem to act as triggers for flashbacks.

Mode of birth was a category with a variety of profiles in experiences of success and failure: an expected, successful vaginal birth; an expected vaginal birth with feelings of failure; an attempt at a vaginal birth ending in caesarean birth that was experienced as a failure; an attempt at a vaginal birth ending in a caesarean birth that was experienced as successful; and an expected, planned caesarean birth. If the mode of birth was not expected, some participants seem to have come to terms with it, for example, based on the baby’s health, while others’ descriptions showed different levels of grief, guilt, and disappointment. Saija (multipara, moderate FOC) described a successful vaginal birth, which, according to her wishes, took place in a birthing pool. Essential for a successful experience appeared to be the fulfilment of wishes and expectations, as well as trust in one’s body by both oneself and others.

The subcategory of medical procedures included descriptions of interventions, such as induction of labour and vacuum extraction. There were different approaches to these factors: some described procedures as desirable, some experienced strong disappointment and failure because of them, and some adapted their view. Reija (primipara, moderate FOC) described a conflicting set of experiences. She experienced the birth as different from her expectations, including a medical induction of labour that lasted two days. She experienced losing her strength but also a successful completion of the pushing stage without need for assistance. Reija suggested that an assisted birth would have meant ‘pushing for nothing’, as if all her efforts would have been in vain without a successful end. It seemed important that all the efforts resulted in a successful vaginal birth, which appeared more important than the long duration of labour, tiredness, or a difficult second stage.

Support

This category included participants’ experiences related to the support of hospital staff, spouse, or other support person. The quotes to illustrate the findings can be found in .

Table 5. Examples of quotes.

Typical evaluated qualities of hospital staff were professional skills, empathy, the ability to be present, interaction skills, and ‘a right way of encouragement’ or ‘chemistry’. Indeed, some participants described how midwives made them feel that they would survive a difficult birth, and some felt that midwives’ activities further weakened the experience. Informational support was considered helpful, and, on the other hand, a lack of information was accompanied with fear, concern for the baby, and uncertainty. Elina (primipara, moderate FOC) described unsuccessful experiences related to staff. She described an experience of not being heard during labour and the resulting feeling of worthlessness. Her experience can potentially be interpreted as obstetric violence in both mental and physical ways.

Some participants described the presence of a spouse or a support person as important in the progression of the physiological process of childbirth and others as mental support and encouragement. Noora (primipara, severe FOC) described the important role the spouse’s support played for her. In Noora’s description, the presence of a spouse was interpreted to make the labour progress because it allowed Noora to relax. Noora thus suggested that the presence of a spouse may be essential for birth physiology and represent success as a result of co-agency between spouses. This view may represent a childbirth philosophy that treats birth as a collective or relational event rather than as an individual activity, which proposes that understanding what constitutes a successful experience must also consider an individual’s childbirth philosophy and how it is related to the actual birth.

Fear of childbirth and parity

The second aim of the study was to determine whether there were differences in the experiences of success and failure according to FOC or parity. The participants’ sum scores in the W-DEQ A ranged from 26 to 133 (M = 58.71, SD = 19.47) and 11.5% suffered from severe FOC. Primiparous respondents had, on average, higher FOC (M = 59.34, SD = 15.27) than multiparous respondents (M = 57.96, SD = 21.65). Parity and FOC did not correlate statistically significantly with each other. Since there were slightly more primiparae than multiparae in this study, we expected primiparae to more often express successes and failures. The numbers of expressions within each category organised by fear of childbirth and parity are displayed in .

Table 6. Frequencies of the expressions of success and failure according to Parity.

In comparing participants with severe FOC and other participants, contrary to expectations, the total numbers of success and failure expressions did not differ statistically significantly between people with FOC and other participants (failures t(111) = −.394, p = .695; successes t(111) = .930, p = .354). This result implies that the likelihood of failure experiences could not be connected to fear of childbirth in the present study. However, in some of the subcategories, the numbers of answers from people with FOC were larger than expected, although testing for statistical significance was not reasonable due to the small number of expressions in each category. In the subcategory Mode of birth, 42.9% of those referring to experiences of failure had severe FOC, which is the clearest difference in proportion of FOC among all subcategories compared to the whole sample (11.5%). In two subcategories, severe FOC was more common among participants with experiences of failure than in the whole sample: complications (21.4%) and pain relief (14.3%).

According to parity, there were statistically significant differences in total numbers of expressions of failure: primiparous participants more often expressed failures (n = 111) than multiparous participants (n = 22) (t(104,92) = 4.79, p < .001). In terms of subcategories, there were differences in almost every subcategory in the distribution of expressions for the experiences of success and failure ( and ). However, testing for statistical significance was not reasonable for subcategories due to the small number of expressions from multiparous participants. For this reason, differences in subcategories should be understood as reflecting the overall distribution of the expressions, that is, as most expressions of failure coming from primiparous participants. In expressions of success, primiparous and multiparous participants did not differ statistically significantly (t(111) = −.770, p = .443). This was also observed in subcategories, as in nearly all categories both primiparous and multiparous participants described experiences of success. The proportion of primiparous participants’ expressions of success (60.3.%) was very close to the proportion of primiparous participants in the sample (59.3%).

Discussion

The first aim of the present study was to determine what kinds of birth-related experiences of success and failure were described by the participants. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to assess feelings of success and failure in the same study. We found that these opposite experiences could be described within the same categories, representing positive and negative ends of the same continuum. As a result of content analysis, the participants’ descriptions of birth-related success and failure experiences were organised into 12 sub-categories and three higher-order categories. One overarching category, diversity of childbirth, encompassed all the categories and sub-categories.

The large number of categories found in the present study support previous findings suggesting that childbirth experiences are multifactorial (Dencker et al., Citation2020) and individual (Prinds et al., Citation2014; Saxbe, Citation2017). The overarching category suggested that childbirth events may be perceived and interpreted differently by different individuals, including what aspects are defined as important and how they relate to the goals or expectations that the person had prior to birth. In the present study, there were different subjective experiences of clinically similar birth events, and clinically different events but subjectively similar experiences. For some participants, certain events represented failures and for others they were neutral or even experienced as successful.

The main categories found in this study reveal that birth experiences sometimes include evaluations of oneself, of the birth, and of other people. This is most likely related to the importance of the birth event in the transition to parenthood. The same participants often expressed some aspects of birth as successes and some other aspects as failures, which proposes that often birth experiences include internally contradicting elements. The most typical experiences of success were in mode of birth, staff, and psychological factors, whereas the most typical experiences of failure were in staff and psychological factors. This is in line with previous findings suggesting that overall satisfaction of birth is dependent on obstetrical and relationship factors (Chabbert et al., Citation2020). The findings also support previous findings on experiences of failure (Kjerulff & Brubaker, Citation2017; Schneider, Citation2013), suggesting that postpartum people often feel shame and guilt and blame themselves for their negative experiences. The findings of the present study enlarge these previous findings by proposing one possible explanation for why a surgical birth, for example, is often associated with more negative birth experiences: A vaginal birth may be perceived as the baseline for a successful experience, which probably reflects our cultural beliefs that equate birth with a vaginal birth (Weaver & Magill-Cuerden, Citation2013. In the present study, mode of birth was most often mentioned as a successful aspect of birth, possibly reflecting the priority given to it. This finding supports the study of Viirman et al. (Citation2023), which proposed that safety is often prioritised in the overall evaluation to other aspects of birth. However, despite being perceived as less important, perceived failures in these aspects may still have consequences for maternal well-being. More research is needed on internally contradictory experiences and their effects on maternal well-being.

The results suggested that failures were most often attributed to staff or to oneself, representing failed expectations that are differently attributed. Some of the participants’ accounts pointed out that interaction with staff can be a determining factor for the quality of birth experiences. The findings are in line with previous studies highlighting the crucial role of social support in birth experiences (Chabbert et al., Citation2020; Karlström et al., Citation2015; McKelvin et al., Citation2020). It has been found that relationships may be more important for the overall experience than objective events during birth (Harris & Ayers, Citation2012; Hodnett, Citation2002; Lundgren & Berg, Citation2007). The feeling of being failed by other people or by the care system may play an essential component in these negative experiences, and it probably reflects needs that are not met in childbirth. Indeed, interpersonal aspects in birth may have independent consequences for well-being, regardless of safety, mode of birth, or overall experience of birth. Childbirth involves special vulnerability (MacLellan, Citation2020), which should be better addressed in perinatal care. A one-size-fits-all model of care is unlikely to foster good experiences.

Psychological factors that were found for experiences of both success and failure are interesting. It is possible that birth is, on the one hand, an important transition that promotes self-reflection and actively brings internalised images of oneself to the fore, including negative beliefs of oneself. On the other hand, birth is a culturally laden event that may be perceived as representing the quality of womanhood or motherhood, and not meeting cultural expectations of an ideal birth may cause feelings of failure (Schneider, Citation2018). Some birthing people may expect to fulfil an idealised natural birth (Hall, Citation2016; Preis et al., Citation2019), and they can become judgemental towards themselves if unsuccessful. Performance expectations can explain experiences of failure in all categories but probably appear pronounced in relation to psychological abilities, which may be more easily perceived as controllable than obstetric events. Moreover, evaluating one’s own psychological capabilities may be related to internalised control, which is found to be central in women’s birth behaviours (Martin, Citation2003; Westergren et al., Citation2021). Expectations to stay in control of oneself and feelings of uncontrollability in birth may conflict and cause perceptions of failure.

Feelings of failure in birth most likely have different consequences than negative experiences that do not include such feelings. Indeed, negative experiences and feelings of failure cannot be considered synonymous. Negative experiences may consist of external factors, such as a lack of support or an uncomfortable environment, and often invoke feelings of anger and distrust (Graham et al., Citation2002). Failure, in contrast, refers to a lack of success or falling short of something (Merriam-Webster, Citation2023), which often invokes feelings of guilt, shame, and depression (Kjerulff & Brubaker, Citation2017), and may even affect one’s self-perceptions (e.g. Bandura, Citation1994) and self-esteem (Brown & Dutton, Citation1995). Future research should urgently address the consequences of experiences of success or failure in childbirth.

The second research aim was to determine whether there were differences in the experiences of success and failure according to fear of childbirth and parity. In the total numbers of expressions of success and failure, statistically significant differences could not be observed between people with FOC and other people. This seems counterintuitive and may be explained by the small sample size and relatively few participants with FOC (n = 113, out of which 11.5% suffered from severe FOC). Although not tested for statistical significance, in the present study, people with FOC provided more expressions of failure than expected in the categories mode of delivery, complications, and pain. Previous studies suggest that FOC is associated with more difficult births, as it is a risk factor for instrumental and surgical births (Sydsjö et al., Citation2012), obstetric complications (Dencker et al., Citation2020), and preference for epidural analgesia (Hendrix et al., Citation2022; Räisänen et al., Citation2014) FOC may also cause reduced confidence in oneself and in staff (Lowe, Citation2000; Wigert et al., Citation2020), which may result in negative interactions and more severe pain. It is possible that with more data, differences between participants with FOC and other participants may have appeared significant. Future studies should explore whether fear of childbirth is related to increased probability of experiencing some kind of failure in childbirth.

Differences according to parity in experiences of failure appeared statistically significant, but the same could not be observed in experiences of success. While the expressions of success came as often from primiparous and multiparous participants, descriptions of failure more often came from primiparae. This finding implies that primiparous people are probably more prone to interpreting some aspects of birth as to have failed than multiparous people, or at least they are more likely to report them. Primiparae may be more vulnerable for unrealistic expectations and thus more likely to feel like failures when not achieving them, or they may more easily judge some aspects of birth as failed. However, it may reflect more difficult births in primiparae. Negative experiences have in many studies been found to be more common among primiparous people, although contradicting evidence also exists (Chabbert et al., Citation2020). Multiparous people’s expectations may be lower, or they may be more likely to achieve their high expectations (Preis et al., Citation2019). Even when their births do not unfold as hoped, multiparous people may be able to mitigate this with other aspects in their lives, such as self-confidence in motherhood. In clinical practice, the needs of primiparous people should be better addressed, as feelings of failure may have consequences for maternal well-being and parenting.

Overall, describing birth experiences in terms of success or failure seems to encompass gendered expectations for birthing performance. Childbirth has been proposed to act as an arena for ‘doing gender’: birthing women are, in line with gendered expectations, grateful to their nurturing midwives and often excuse it if they do not feel the care to be as good as they hoped it would (Westergren et al., Citation2021). Feelings of success and failure may thus reflect conformity to gendered behaviour expectations. It may be easy to feel the midwife’s support as successful when she is perceived as nurturing; similarly, a negative birth experience may be internalised (perceive oneself as having failed) or perceived as a failure of staff (gender non-conforming midwives) or explained by external reasons, such as an overcrowded labour ward (see, Westergren et al., Citation2021). However, feelings of failure in relation to staff may also represent the high priority of having one’s needs met in a specially vulnerable moment (MacLellan, Citation2020), and the deep disappointment that insufficient support may cause.

Experiences of success or failure in childbirth set a tone for motherhood that may have long-lasting effects on the mental well-being of the mother. Future research should better describe experiences of success and failure in childbirth and connect them with expectations, care practices, and societal expectations of motherhood and childbirth performance. Because most experiences of failure were expressed by primiparous participants, developing childbirth preparation classes to address their needs should be a priority. Providing accurate information and promoting self-compassion may be beneficial. Developing care practices to meet childbearing people’s expectations is crucial, especially in the care of primiparous people. As cognitive and emotional processes can be affected through psychological support, postnatal services should be offered to people with difficult experiences. The responsibility to offer these services is on health care professionals, as it has been found that feelings of failure may cause the person to avoid speaking about their experience (Schneider, Citation2013).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the present study were its longitudinal design, which allowed assessing FOC prior to childbirth, and low drop-off rate from the first to second measurement point. Quantitative analysis was fruitful for comparing the answers of primiparous and multiparous people, and it provided new knowledge on their differences. However, there were also limitations concerning the low participation rate during the first phase and possible self-selection bias. The participants in the study were highly educated and more often primiparous than the average mother in Finland, which may have affected the results. Highly educated people may be more likely to experience their births in more positive ways (Zadoroznyj, Citation1999), have a stronger sense of control over the events of birth, and even receive more respectful care (Vedeler et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, experiences of success and failure were derived from answers to a very general question on childbirth experience and not a question specifically addressing them. Despite the limitations of the study, the results can be seen as illustrative of experiences of success and failure, and they provide more information on psychological mechanisms and cultural ideals in birth experiences.

Conclusions

Mothers evaluate their performances in terms of personal factors and assess the course of childbirth and the support they received or did not receive as successful or not. Primiparity seems to be related to the higher probability of experiencing failures in childbirth, but further research on experiences of success and failure, and the possible role of fear of childbirth in them, is needed. Some experiences of failure may be prevented by promoting self-compassion and lowering societal standards and some by developing care practices. Special attention should be paid in perinatal care to address the needs of primiparous people throughout the transition to parenthood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is freely available at https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/81710

Notes

1. Succeed: 1. To end up in a result that is hoped for, intended or good; to go happily, to become as intended or hoped; 2. to accomplish something happily, successfully, or as hoped; to end up with the intended result; to cope well with something, to succeed, to get by; 3. someone can (despite challenges) accomplish something. [Translation by the authors]

2. Fail: Not to succeed in something, to succeed badly, to be unsuccessful, to suffer adversity. [Translation by the authors]

References

- Ayers, S., Eagle, A., & Waring, H. (2006). The effects of childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder on women and their relationships: A qualitative study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(4), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600708409

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman (Ed.). Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998)

- Brown, J. D., & Dutton, K. A. (1995). The thrill of victory, the complexity of defeat: Self-esteem and people’s emotional reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 712–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.712

- Chabbert, M., Panagiotou, D., & Wendland, J. (2020). Predictive factors of women’s subjective perception of childbirth experience: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 39(1), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2020.1748582

- Chadwick, R. J., & Foster, D. (2013). Technologies of gender and childbirth choices: Home birth, elective caesarean and white femininities in South Africa. Feminism and Psychology, 23(3), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353512443112

- Choi, P., Henshaw, C., Baker, S., & Tree, J. (2005). Supermum, superwife, supereverything: Performing femininity in the transition to motherhood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 23(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830500129487

- Coo, S., García, M. I., & Mira, A. (2023). Examining the association between subjective childbirth experience and maternal mental health at six months postpartum. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 41(3), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2021.1990233

- Creswell, J. & Plano Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dencker, A., Bergqvist, L., Berg, M., Greenbrook, J. T. V., Nilsson, C., & Lundgren, I. (2020). Measuring women’s experiences of decision-making and aspects of midwifery support: A confirmatory factor analysis of the revised childbirth experience questionnaire. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02869-0

- Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish. (2022a). Headword ‘Epäonnistua’. Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Online Publication HTML. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://www.kielitoimistonsanakirja.fi/#/ep%C3%A4onnistua?searchMode=all

- Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish. (2022b). Headword ‘Onnistua’. Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Online Publication HTML. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://www.kielitoimistonsanakirja.fi/#/onnistua?searchMode=all

- Elvander, C., Cnattingius, S., & Kjerulff, H. (2013). Birth experience in women with low, intermediate or high levels of fear: Findings from the first baby study. Birth, 40(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12065

- Eriksson, C., Jansson, L., & Hamberg, K. (2006). Women’s experiences of intense fear related to childbirth investigated in a Swedish qualitative study. Midwifery, 22(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2005.10.002

- Eriksson, C., Westman, G., & Hamberg, K. (2010). Content of childbirth-related fear in Swedish women and men—analysis of an open-ended question. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 51(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.08.010

- Graham, J. E., Lobel, M., & DeLuca, R. S. (2002). Anger after childbirth: An overlooked reaction to postpartum stressors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00061

- Grbich, C. (2012). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Sage Publications.

- Hall, C. (2016). Womanhood as experienced in childbirth: Psychoanalytic explorations of the body. Psychoanalytic Social Work, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228878.2015.1073161

- Harris, R., & Ayers, S. (2012). What makes labour and birth traumatic? A survey of intrapartum ‘hotspots’. Psychology & Health, 27(10), 1166–1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.649755

- Hauck, Y., Fenwick, J., Downie, J., & Butt, J. (2007). The influence of childbirth expectations on Western Australian women’s perceptions of their birth experience. Midwifery, 23(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.02.002

- Hendrix, Y. M., Baas, M. A., Vanhommerig, J. W., de Jongh, A., & Van Pampus, M. G. (2022). Fear of childbirth in nulliparous women. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(July), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.923819

- Hodnett, E. (2002). Pain and women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(5), S160–S172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(02)70189-0

- Karlström, A., Nystedt, A., & Hildingsson, I. (2015). The meaning of a very positive birth experience: Focus groups discussions with women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0683-0

- Kjerulff, K. H., & Brubaker, L. H. (2017). New mothers’ feelings of disappointment and failure after cesarean delivery. Birth, 45(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12315

- Kringeland, T., Daltveit, A. K., & Moller, A. (2010). How does preference for natural childbirth relate to the actual mode of delivery? A population-based cohort study from Norway. Birth (Berkeley, Calif), 37(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00374.x

- Kringeland, T., Daltveit, A. K., & Møller, A. (2009). What characterizes women who want to give birth as naturally as possible without painkillers or intervention? Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 1(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2009.09.001

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications.

- Lally, J. E., Murtagh, M. J., Macphail, S., & Thomson, R. (2008). More in hope than expectation: A systematic review of women’s expectations and experience of pain relief in labour. BMC Medicine, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-6-7

- Larkin, P., Begley, C., & Devane, D. (2009). Women’s experiences of labour and birth: An evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery, 25(2), e49–e59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2007.07.010

- Lowe, N. K. (2000). Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 21(4), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820009085591

- Lundgren, I., & Berg, M. (2007). Central concepts in the midwife-woman relationship. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 21(2), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00460.x

- Macdonald, M. (2006). Gender expectations: Natural bodies and natural births in the new midwifery in Canada. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 20(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2006.20.2.235

- MacLellan, J. (2020). Vulnerability in birth: A negative capability. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(17–18), 3565–3574. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15205

- Malacrida, C., & Boulton, T. (2012). Women’s perceptions of childbirth “choices”: Competing discourses of motherhood, sexuality, and selflessness. Gender & Society, 26(5), 748–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243212452630

- Martin, K. A. (2003). Giving birth like a girl. Gender & Society, 17(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243202238978

- McKelvin, G., Thomson, G., & Downe, S. (2020). The childbirth experience: A systematic review of predictors and outcomes. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(5), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.021

- Merriam-Webster. (2023). Dictionary of contemporary English. Headword “Failure”. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/failure

- Molgora, S., Fenaroli, V., & Saita, E. (2020). The association between childbirth experience and mother’s parenting stress: The mediating role of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Women & Health, 60(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1635563

- Nilsson, C., Hessman, E., Sjöblom, H., Dencker, A., Jangsten, E., Mollberg, M., Patel, H., Sparud-Lundin, C., Wigert, H., & Begley, C. (2018). Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1659-7

- O’Connell, M. A., Khashan, A. S., & Leahy-Warren, P. (2021). Women’s experiences of interventions for fear of childbirth in the perinatal period: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research evidence. Women & Birth, 34(3), e309–e321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.05.008

- Olza, I., Leahy-Warren, P., Benyamini, Y., Kazmierczak, M., Karlsdottir, S. I., Spyridou, A., Crespo-Mirasol, E., Takács, L., Hall, P. J., Murphy, M., Jonsdottir, S. S., Downe, S., & Nieuwenhuijze, M. J. (2018). Women’s psychological experiences of physiological childbirth: A meta-synthesis. British Medical Journal Open, 8(10), e020347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020347

- Preis, H., Lobel, M., & Benyamini, Y. (2019). Between expectancy and experience: Testing a model of childbirth satisfaction. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318779537

- Prinds, C., Hvidt, N. C., Mogensen, O., & Buus, N. (2014). Making existential meaning in transition to motherhood—A scoping review. Midwifery, 30(6), 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.021

- Räisänen, S., Lehto, S., Nielsen, H., Gissler, M., Kramer, M., & Heinonen, S. (2014). Fear of childbirth in nulliparous and multiparous women: A population‐based analysis of all singleton births in Finland in 1997–2010. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 121(8), 965–970. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12599

- Reisz, S., Jacobvitz, D., & George, C. (2015). Birth and motherhood: Childbirth experience and mothers’ perceptions of themselves and their babies. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21500

- Rondung, E., Magnusson, S., & Ternström, E. (2022). Preconception fear of childbirth: Experiences and needs of women fearing childbirth before first pregnancy. Reproductive Health, 19(1), 1–202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01512-9

- Saxbe, D. (2017). Birth of a new perspective? A call for biopsychosocial research on childbirth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416677096

- Schneider, D. A. (2010). Beyond the Baby: Women’s Narratives of Childbirth, Change and Power. ( Doctoral dissertation). Smith Scholar Works: Smith College.

- Schneider, D. A. (2013). Helping women cope with feelings of failure in childbirth. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 28(1), 46–50.

- Schneider, D. A. (2018). Birthing failures: Childbirth as a female fault line. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 27(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.27.1.20

- Sydsjö, G., Sydsjö, A., Gunnervik, C., Bladh, M., & Josefsson, A. (2012). Obstetric outcome for women who received individualized treatment for fear of childbirth during pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01242.x

- Taheri, M., Takian, A., Taghizadeh, Z., Jafari, N., & Sarafraz, N. (2018). Creating a positive perception of childbirth experience: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal and intrapartum interventions. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0511-x

- Vedeler, C., Eri, T. S., Nilsen, R. M., Blix, E., Downe, S., van der Wel, K. A., & Nilsen, A. B. V. (2023). Women’s negative childbirth experiences and socioeconomic factors: Results from the babies born better survey. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 36, 100850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2023.100850

- Viirman, F., Hesselman, S., Poromaa, I. S., Svanberg, A. S., & Wikman, A. (2023). Overall childbirth experience: What does it mean? A comparison between an overall childbirth experience rating and the childbirth experience questionnaire 2. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 23(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05498-5

- Weaver, J., & Magill-Cuerden, J. (2013). “Too posh to push”: The rise and rise of a catchphrase. Birth (Berkeley, Calif), 40(4), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12069

- Westergren, A., Edin, K., & Christianson, M. (2021). Reproducing normative femininity: Women’s evaluations of their birth experiences analysed by means of word frequency and thematic analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(300). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03758-w

- Wigert, H., Nilsson, C., Dencker, A., Begley, C., Jangsten, E., Sparud-Lundin, C., Mollberg, M., & Patel, H. (2020). Women’s experiences of fear of childbirth: A metasynthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1704484. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2019.1704484

- Wijma, K., Wijma, B., & Zar, M. (1998). Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 19(2), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829809048501

- Zadoroznyj, M. (1999). Social class, social selves and social control in childbirth. Sociology of Health & Illness, 21(3), 267–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00156

- Zar, M., Wijma, K., & Wijma, B. (2001). Pre- and postpartum fear of childbirth in nulliparous and parous women. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 30(2), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/02845710121310