ABSTRACT

Aims

To evaluate the effects of a 5-day residential psychoeducational program on maternal anxiety and fatigue symptoms among women admitted with their unsettled infants and determine the psychological, social and demographic characteristics which are associated with the effect sizes.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of routinely collected data from mothers with children aged up to 24 months who were admitted to and completed the residential early parenting psychoeducational program at Masada Private Hospital Early Parenting Centre in Melbourne. Maternal anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale Three-item Anxiety subscale and maternal fatigue symptoms were the Modified Fatigue Assessment Scale at preadmission, predischarge and follow-up 6-weeks post discharge.

Results

Overall, 1220 admissions were included in analyses. Cohen’s d for reductions in the anxiety symptoms during the program was 0.64 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.70) and from pre-discharge to post-discharge was 0.14 (95% CI 0.09 to 01.9), and for fatigue was 1.21 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.32). Higher borderline personality disorder symptoms and experiencing more stressful life events were associated with lower mean reductions in anxiety and fatigue symptoms. Women with a history of mental health problems had lower anxiety symptom reductions. Women who were older or had younger babies had lower fatigue score reductions.

Conclusion

This study confirms the effectiveness of a 5-day residential early parenting psychoeducational program provided by a private sector facility in reducing postnatal anxiety and fatigue rapidly, with effects maintained to at least 6-weeks post-discharge.

Introduction

Unsettled infant behaviour is a descriptor commonly used to capture behaviours of babies in the first years of life, which can be major concerns for parents (Fisher et al., Citation2011). It includes prolonged and inconsolable crying, resistance to soothing and settling, waking after short sleeps and frequent overnight waking. The prevalence of unsettled infant behaviour has not been established because there is a lack of a consensus definition of the problem. However, it has been reported that at least one in four families experience problematic infant crying and fussing behaviours and up to one in three families experience a problem with infant sleep (Fisher et al., Citation2011). Empirical data have shown that unsettled infant behaviour can have adverse effects on parents’ physical and mental health outcomes, including maternal depression, anxiety (Hiscock & Fisher, Citation2015; Hiscock et al., Citation2007) and fatigue (Kurth et al., Citation2011; Morrell & Steele, Citation2003), paternal depression, anger and frustration (Ellett et al., Citation2009), hostility in the parents’ relationship with each other (Fisher et al., Citation2011), parent–infant relationship (Sarah Oldbury et al., Citation2015) and the babies’ behaviours in later life (Sanson et al., Citation1998).

Infant crying is a powerful anxiety arousing experience, and parents, especially when fatigued can respond emotionally rather than cognitively, using diverse caregiving behaviours to stop the crying, including rocking, pacing, driving, co-sleeping, very frequent suckling, white noise machines, robotic bassinets and attempts to distract the baby. Even if effective in the short term, effects are often not lasting, and the techniques are often not sustainable or always safe (Fisher et al., Citation2011).

Several behavioural and educational programs and approaches have been developed to help parents to manage unsettled infant behaviours. The programs usually provide education for parents on sleep/cry behaviours, sleep cues, unsustainable sleep associations, settling techniques and age-appropriate feeding practices and have been delivered in community health services, general practices or specialist paediatric services. The methods of delivery can be through individual face-to-face short consultations, day programs, or four or five night residential programs. Data from previous trials demonstrated some positive effects in the reduction of sleeping and crying problems among infants (Don et al., Citation2002; Middlemiss et al., Citation2017) and improvement of maternal postpartum depressive symptoms (Fisher et al., Citation2004; Rowe & Fisher, Citation2010).

There is some evidence that behavioural and educational programs for unsettled infant behaviours also reduce anxiety symptoms experienced by mothers of infants. Improving specific knowledge and caregiving skills including putting the baby to bed awake, using rhythmic shooshing and patting to soothe the baby, can reduce anxiety through increasing self-efficacy, confidence and sense of agency. It is also possible that being taught to distinguish fussing and grizzling, which can be an infant’s self-soothing behaviours, from intense crying and to wait for a defined period before intervening allows women to experience diminution in anxiety through supported exposure as the baby quietens and settles to sleep.

Fisher et al. (Citation2004) evaluated the effect of a five-night residential program in a small cohort study and found that the Profile of Mood States – Anxiety scores in the clinical range among 57 mothers reduced from 26% at admission to 3% at 6-month follow-up (p < 0.0001). Treyvaud et al. (Citation2009) in a similar study assessed another 5-day early residential parenting program in a public early parenting centre in Victoria, Australia, and found significant declines in the Anxiety sub-scale scores of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale among 44 mothers from the first day of the program to the last day of the program and to 4 weeks after the program. Rowe and Fisher (Citation2010) conducted a study of 79 women admitted to a public residential program in Victoria, Australia, for three or four-night stays in an early parenting centre and found the proportion with the Profile of Mood States – Anxiety scores in the clinical range reduced from 20% at admission to 8% at 1 month and 7% at 6-month follow-up. Nevertheless, Hauck et al. (Citation2012) did not find a statistically significant difference in the means of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – Anxiety sub-scale scores of 93 women 4 weeks after participating in a Day Stay intervention in an early parenting centre in Western Australia and that of 85 mothers from a control group who reported sleep and settling concerns and recruited from community via an advertising campaign.

Fatigue is a state in which a person has a sense of weariness or depletion which leads to a diminished ability to perform at their anticipated levels (Aaronson et al., Citation1999). Severe fatigue is common among women during the postpartum period and is strongly related to their babies’ unsettled behaviours (Fisher et al., Citation2011; Giallo et al., Citation2011). Some studies have examined the effects on maternal fatigue of behavioural and educational programs for new mothers targeting the management of unsettled infant behaviours. Fisher et al. (Citation2004) found that the proportions of women with Profile of Mood States – Fatigue scores in the clinical range declined from 78% at admission to 32% at six-month follow-up (p < 0.0001). Rowe and Fisher’s (Citation2010) also found reductions in the proportion of women with Profile of Mood States – Fatigue scores in the clinical range from 69% at admission to 43% at 1 month and 35% at 6-month follow-up.

Anxiety and fatigue are two important maternal outcomes of the trials on behavioural and educational programs for parents targeting unsettled infant behaviours alongside the common primary outcomes, of postpartum depression and duration of infant crying and sleeping. Overall, this evidence suggests that the behavioural and educational programs have positive effects on maternal anxiety and fatigue. Nevertheless, the evidence is based on small-scale studies which included relatively small sample sizes, open to participation biases because of modest recruitment and retention fractions. We aimed (1) to assess the effects on maternal anxiety and fatigue symptoms of a 5-day residential psychoeducational program for mothers admitted with their unsettled infants and (2) to determine the psychological, social and demographic characteristics which are associated with the effect sizes using a large real-world data set.

Materials and methods

Study design

We analysed data routinely collected from patients admitted to the residential early parenting psychoeducational program at Masada Private Hospital Early Parenting Centre in Melbourne, Australia.

Masada private hospital’s early parenting psychoeducational program

Masada Private Hospital Early Parenting Centre was established in 1996 and currently has 20 beds. It is located in a suburban private hospital in Melbourne. The Centre provides a residential early parenting psychoeducational program. It is one of the largest private early parenting services in Australia. Five parent-infant dyads are admitted and discharged each day. There is a waiting list for admission and empty beds are rare. Details about this program are provided elsewhere (Fisher et al., Citation2004).

In short, mothers of infants aged up to 24 months who are experiencing problems with unsettled behaviours including, disturbances of the sleep wake cycle or feeding difficulties in the infant and/or anxiety, depression, clinical exhaustion and adjustment difficulties are eligible for admission, with a medical referral, to the program. The program is provided in a private hospital so people seeking admission have to hold private health insurance or be able to pay the costs of admission.

It is a structured five-night program for primary caregivers, who are usually mothers, and their infant(s). It provides an individualised program to educate each mother about age-appropriate infant care and gives her supported opportunities to implement new caregiving practices. Individual strategies are designed to support the mother to help her baby by establishing a daily ‘feed, play, sleep’ routine that can be maintained. Recognition of their baby’s tired cues, an understanding of how much sleep an infant needs, and the benefit to a baby of predictable routines of care, sustainable soothing and having sufficient sleep, are discussed and demonstrated.

A psycho-educational group session is held on Day One for each admission group covering sleep states, early childhood development, daily routines, and age-appropriate feeding, playing and sleeping. In addition, conversations and reflections about the adjustment to parenthood are discussed with nursing staff in daily individual conversations. On Day Four there is a pre-discharge group which provides practical tips on how to transfer the learned skills to the home environment and how to manage reversions in behaviour. Women are encouraged to go out for walks and to build collegial relationships with the other mothers completing the program.

Data sources

We included data contributed routinely by mothers with children aged up to 24 months who were admitted to the five-night residential program at Masada Private Hospital Early Parenting Centre between May 2021 and September 2022. We excluded incomplete data from women who did not complete the program. Early discharge was most commonly because of respiratory or gastro-intestinal infections experienced by the mother or the baby.

Data of the outcomes and determinants () were collected using Vision Tree Optimal Care (VTOC™) an electronic patient reported outcomes system. Maternal anxiety symptoms were assessed at pre-admission (about 2 weeks before admission into the program), pre-discharge (day 5 of the program), and follow-up (6-weeks post-discharge). Maternal fatigue symptoms were collected at admission and follow-up. The determinants were assessed pre-admission.

Table 1. Measures.

All data collection forms were in self-completed digital format using VTOC™. Women completed the forms in the platform using smartphones or computers.

Data management and statistical analyses

It was estimated that a sample of 1125 women was needed to detect a minimum reduction of 0.10 standard deviation in the outcome variables between pre-admission and pre-discharge/follow-up with power 0.80, Type I error 0.05, and up to 30% missing data. The sample size was calculated using the Power and Sample Size software Version 3.1.6 (October 2018).

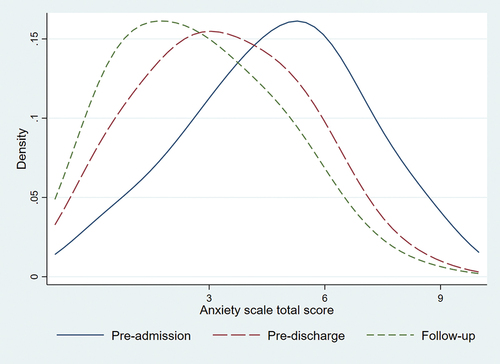

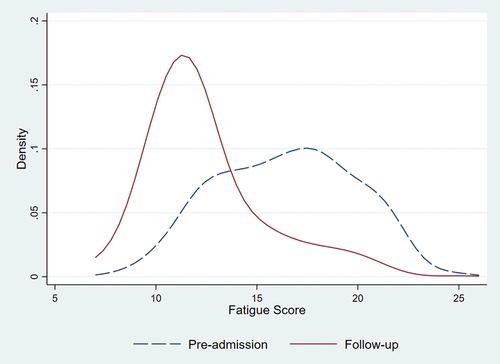

We described the distributions of the EPDS-3A scores at three timepoints (pre-admission, pre-discharge, and follow-up) visually and estimated the changes in the proportions of high anxiety symptoms between timepoints to estimate the effects of the program on anxiety symptoms during the program and post-discharge periods. We examined the effect of the program on fatigue by comparing mean FAS fatigue scores between admission and follow-up.

Cohen’s d effect sizes (mean difference/pooled standard deviation) were calculated to quantify the effects of the program. Cohen’s d of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 indicating small, medium and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation1992).

Multiple linear regression models in which the individual and psychosocial characteristics at admission were included as predictors to predict the reduction of the EPDS-3A scores (from pre-admission to pre-discharge and pre-discharge to follow-up) or fatigue scores (from admission to follow-up). In this study, the selection of individual and psychosocial characteristics was based on our clinical experience and research knowledge.

Data analyses were conducted using Stata Version 16.1. Missing data on EPDS-3A and Fatigue Assessment Scale item data at any assessment timepoint were not imputed. Missing data of the determinants (individual and psychosocial characteristics at pre-admission) were imputed for the model analyses using a multiple imputation method (10 imputations). The ‘mi estimate’ command in Stata was used to estimate the model parameters from the multiply imputed data and adjust coefficients and standard errors for the variability between imputations according to Rubin’s combination rules (Rubin, Citation1987). We conducted sensitivity analyses of the effectiveness of the program with complete cases.

Ethics approval

Approval to conduct the project was provided by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (Certificate Number 2020–25903–51810).

Results

Data from 1220 of 1290 eligible admissions (95%) during the study period were included in the analyses. The 70 admissions excluded were because of missing data of the outcomes (EPDS-3A and Fatigue Assessment Scale) at either pre-admission (9 women) and pre-discharge (61 women) assessments. Among the 1220 admissions included in analyses, 46 (3.8%) had missing data related to individual and psychosocial characteristics at pre-admission which were imputed and 559 (45.8%) provided data at the 6-week follow-up. The characteristics of the subgroup with data at follow-up are similar to those of the whole sample ().

Table 2. Psychosocial and demographic characteristics at pre-admission.

Mean anxiety scores reduced consistently and statistically significantly from pre-admission to pre-discharge to follow-up (). Similarly, the proportion of women with high anxiety symptoms declined across the three time points. The whole distribution of the EPDS-3A scores shifted to the left confirming that the reductions were in the whole range, not only at the highest or lowest end (). Cohen’s d for changes in the anxiety symptoms during the program was 0.64 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.70) and from pre-discharge to post-discharge was 0.14 (95% CI 0.09 to 01.9)

Figure 1. Distributions of anxiety scale (EPDS-3A) total scores at pre-admission, discharge, and follow-up.

Table 3. Anxiety scale total scores and categories.

The reduction in anxiety scores between pre-admission and pre-discharge and between pre-discharge and follow-up were associated with several maternal and infant characteristics (). Higher borderline personality disorder symptoms were associated with lower mean anxiety score reductions during the program and in the post-discharge periods. Women with higher anxiety at pre-admission had higher mean anxiety score reductions from pre-admission to pre-discharge and from pre-discharge to follow-up.

Table 4. Models predicting the reduction of EPDS-3A anxiety scores.

Women experiencing insufficient support from family and friends and women with higher parenting confidence had larger mean anxiety score reductions during the program. Women experiencing more stressful life events had smaller anxiety score reductions during the program and women seeing a mental health professional prior to having this baby had smaller anxiety score reductions in the post-discharge period.

Among 498 women who provided data on fatigue at follow-up, the mean FAS fatigue score reduced from 16.3 (95% CI 16.1; 16.7) at admission to 12.3 (95% CI 12.1; 12.6) at follow-up. The distribution curve of FAS fatigue scores shifted to the left from admission to follow-up (). Cohen’s d was 1.21 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.32).

Figure 2. Distributions of FAS fatigue scores at pre-admission and 6-week post discharge (follow up).

The reduction in the FAS fatigue scores was associated with women’s age, borderline personality disorder symptoms, stressful life events, the infant’s age, and the fatigue score at admission (). Women who were older, or with higher borderline personality disorder symptoms, or experiencing more stressful events, or having a younger baby had lower FAS fatigue score reductions. Women with higher FAS fatigue scores at admission had higher fatigue score reductions.

Table 5. Multiple linear regression model predicting the reduction in fatigue scores (pre-admission score – follow-up score).

Discussion

This paper reports the analyses of data collected routinely in a residential Early Parenting Psychoeducational program. We found significant mean reductions in anxiety symptoms of women during the program (a medium effect size) and in the 6 weeks post-intervention (a small effect size). The mean reduction in fatigue symptoms between admission and 6 weeks post-intervention was at a large effect size. We have been able to identify the characteristics of women who had no or only small reductions in anxiety symptoms. These included those experiencing borderline personality disorder symptoms, stressful life events, or who have in the past or are currently consulting a mental health professional. Lower FAS fatigue score reductions were found among older women and women with higher borderline personality disorder symptoms, experiencing more stressful life events, or having a younger baby.

This is the first study to date to have analysed a large set of routinely collected data from a near-complete cohort of women admitted to a residential early parenting program. Assessing the effectiveness of a program with real-world data such as these reduces selection biases and increases both internal and external validity. Nevertheless, we acknowledge some limitations. First, we did not have a control or comparison group. A pre- and post-intervention design can result in an overestimate of effect if the problem reduces with time in a contemporaneously recruited group with similar characteristics who do not receive the intervention. It can also underestimate the effect if the problem worsens with time in a group who just received the usual standard of care. In our study, either of these effects are possible. However, most women admitted to this program have experienced unsettled infant behaviour problems for a reasonably long time, some since the baby’s birth. The duration of the intervention was relatively short. We believe that the problem is unlikely to change substantially in this short period of time without intervention. Therefore, the limitation of the pre- and post-intervention design is thought to be unlikely to cause significant biases in this study. Second, we did not have diagnostic data for the outcomes. However, we focused on the changes of the symptoms of anxiety and fatigue in continuous scales that can capture the whole spectrum of experiences. Third, the majority of women in this study came from advantaged areas. This characteristic of consumers in private healthcare sector differs from that of public healthcare users. Socioeconomic status can act as effect modifiers or confounders. It is important to be cautious when generalising the findings of this study to the similar services provided by the public sector. Finally, the high costs of this service could be a motivation for women to improve by themselves, potentially resulting in overestimated findings. However, the women who used this service were those who could not solve the problem by themselves over a long period of time. It would be very unlikely that they could change it on their own within the short duration of the program.

The results of this study align with previous studies on the positive effects of three- to five-night residential early parenting programs on maternal anxiety symptoms (Fisher et al., Citation2004; Rowe & Fisher, Citation2010; Treyvaud et al., Citation2009). Similarly, the data from this study confirm the findings of previous studies (Fisher et al., Citation2004; Rowe & Fisher, Citation2010) regarding the significant improvement of maternal fatigue symptoms through these programs. However, Hauck et al. (Citation2012) on a Day Stay program found no effect on maternal anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, baby’s overnight waking, or settling time at the 4-week follow-up. It appears that a one-day program might not provide a sufficient ‘dose’ to bring about significant changes in unsettled infant behaviours and, consequently, maternal mental health.

This study reveals several factors associated with the reduction of maternal anxiety symptoms during and after program discharge. Borderline personality disorder symptoms were found to be negatively associated with the improvement in anxiety symptoms both during the course of the program and post-discharge. Borderline personality disorder is a debated diagnosis, but remains in the major diagnostic manuals. Symptoms or traits can include intense relationships with idealisation or vilification of others, dysregulation of affect, and difficulties with trust and in managing anger and frustration (Leichsenring et al., Citation2011). Early parenting programs require capacity to form rapid trusting alliances with care providers, including to care for and settle their babies. New ways of caring for the baby including putting the baby to bed awake, feeding when the baby wakes rather than feeding to sleep, and settling the baby in bed rather than in their arms, can arouse angry resistance. These characteristics make full participation in the program activities difficult and impede the necessary changes in understanding, attitudes, and behaviours related to the knowledge and skills provided, ultimately leading to lower improvements in all outcomes, including anxiety symptoms, as observed in this study. Research on the relationship between borderline personality and anxiety disorders is limited, but it indicates a high prevalence of comorbidity and suggests that borderline personality disorder influences anxiety in particular because self-regulation is poor (Comtois et al., Citation1999; Keuroghlian et al., Citation2015). Therefore, women with anxiety related to borderline personality disorder may not experience improvements in anxiety symptoms due to the program’s lack of specific content or activities that address borderline personality disorder and the specific needs of women with these characteristics.

Similarly, women experiencing stressful life events, those currently seeing or having seen a mental health professional before the program, showed lower reductions in anxiety symptoms. These findings suggest that early parenting programs may not have the same effects for women in varied situations. It is possible that women experiencing several stressful life events are preoccupied and less able to concentrate on the new knowledge being presented and the opportunities to practice and so have insufficient experience to experience anxiety reduction. It is also possible that women with more longstanding mental health problems, for which individual treatment has been sought in the past or is being used concurrently, might require a different ‘dose’ of the intervention in order to derive benefits. It might be that a longer admission or perhaps sequential admissions separated by periods of supported practice at home could be more effective.

On the other hand, this study identified factors associated with improvements in anxiety symptoms. First, women with higher parenting confidence before admission demonstrated better improvement in anxiety symptoms during the program. It is likely that women with higher parenting confidence might already regard parenting skills as being learnt and be open to new opportunities to extend their parenting capabilities. It is also possible that they can apply the knowledge and skills learned in the program more confidently and successfully during the residential program and thereby experience reduced anxiety. Second, women who received little or no help from their families, friends, or others before admission had greater improvements than others in anxiety symptoms. This suggests that the program provided the knowledge, skills, support, and networking that this group of women lacked and that the supportive non-judgemental milieu enabled them to experience the benefits of supported practice. Finally, women with higher anxiety symptoms before admission experienced greater reduction during and after the program. It is logical that when starting with lower levels of mental disorder symptoms, it may be more challenging to achieve a significant reduction compared to starting with higher levels of symptoms. However, this result demonstrates that the program has a positive effect on anxiety symptoms, particularly for those at the higher end of the symptom spectrum.

Like the anxiety symptoms, higher borderline personality disorder symptoms and experiencing more stressful life events were associated with lower levels of fatigue reduction. In addition, being older and having a younger baby were linked to lower reductions in fatigue scores. Age is often an indicator of people’s knowledge, experience, and physical and mental health. Understanding which of these characteristics may influence the program’s effect on fatigue reduction is not straightforward. Among women in the postpartum period, fatigue is highly associated with interrupted and insufficient sleep due to the demands of overnight infant care (Giallo et al., Citation2011). Therefore, the differences in the care needs of younger babies who are still requiring overnight feeds than older babies may moderate the program’s effect on fatigue. This is an individualised program, however, these data suggest that although the program can improve caregiving skills and extend the interval between overnight feeds, it cannot eliminate the fatigue associated with interrupted and insufficient sleep. It suggests that the program might not be indicated for very young infants. In practice, the early parenting centre generally recommends that mothers and infants are not admitted until the infant is at least 16-weeks old.

The data from this study strongly suggest that residential early parenting programs are very helpful to most women, but that, while useful, they might be insufficient to meet all the needs of women with borderline personality disorder symptoms, a history of mental disorders, of older ages, or having younger babies. Women with these characteristics or circumstances might benefit from a higher ‘dose’ of the intervention or follow -up/booster sessions or referral to a specialist psychiatric service in a stepped care approach.

There are several implications for future research. First, it would be useful to understand the nature of anxiety being experienced: to what extent it is generalised or specific to the perinatal period or is more accurately understood as a specific disorder. It would then be useful to understand whether the early parenting program is more or less effective for different disorders. Second, qualitative research would be useful to explore the possible underlying factors that influence the responses of older women to the program. Finally, a replication study among less economically advantaged women to verify the effect sizes and identify whether the influential factors are similar or different.

Conclusion

This study confirms the effectiveness of the 5-day residential Early Parenting Psychoeducational program at Masada Private Hospital in reducing women’s anxiety and fatigue. However, further investigation is needed to identify how the program might be enhanced to meet the needs of sub groups of women, including those experiencing major stressful events, symptoms of personality disorders, with a past history of mental health problems, older ages, or having younger babies. The results of this study can be generalised to similar services provided by the private sector, but it need more evidence for those provided by public sector facilities.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, TT, upon reasonable request.

Contributors

The study conception and design: Jane Fisher and Thach Tran. Material preparation and analysis were performed by Jane Fisher, Thach Tran, Karin Stanzel and Hau Nguyen. Data collection was carried out by Karin Stanzel, Sally Popplestone, Patsy Thean and Danielle French. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Thach Tran and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Approval to conduct the project was provided by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (Certificate Number 2020–25903–51810). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Consent was not needed. All patients admitted to Masada Private Hospital are advised that anonymised data will be drawn from medical records for quality assurance purposes. They are asked to tick a box to acknowledge that they have been informed about this.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the expertise and time of Ms Nicola Ware, Ms Lena Caruso, Ms Catarina Agostino, Ms Penelope Marshall, Ms Clare Jauncey, and Ms Sharon Howell who were members of the project Advisory Board.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, L. S., Teel, C. S., Cassmeyer, V., Neuberger, G. B., Pallikkathayil, L., Pierce, J., Press, A. N., Williams, P. D., & Wingate, A. (1999). Defining and measuring fatigue. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00420.x

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Australian demographic statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3101.0Sep%202019?OpenDocument

- Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Comtois, K. A., Cowley, D. S., Dunner, D. L., & Roy-Byrne, P. P. (1999). Relationship between borderline personality disorder and axis I diagnosis in severity of depression and anxiety. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(11), 752–758. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v60n1106

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150(6), 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

- Črnčec, R., Barnett, B., & Matthey, S. (2008). Karitane parenting confidence scale: Manual.

- Don, N., McMahon, C., & Rossiter, C. (2002). Effectiveness of an individualized multidisciplinary programme for managing unsettled infants. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 38(6), 563–567. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00042.x

- Ellett, M. L., Appleton, M. M., & Sloan, R. S. (2009). Out of the abyss of colic: A view through the fathers’ eyes. MCN The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 34(3), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMC.0000351704.35761.f1

- Fisher, J., Feekery, C., & Rowe, H. (2004). Treatment of maternal mood disorder and infant behaviour disturbance in an Australian private mothercraft unit: A follow-up study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 7(1), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-003-0041-5

- Fisher, J., Rowe, H., & Feekery, C. (2004). Temperament and behaviour of infants aged 4 –12 months on admission to a private mother –baby unit and at 1- and 6-month follow-up. Clinical Psychologist, 8(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284200410001672928

- Fisher, J., Rowe, H., Hiscock, H., Jordan, B., Bayer, J., Colahan, A., & Amery, V. (2011). Understanding and responding to unsettled infant behaviour: A discussion paper for the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY).

- Giallo, R., Cooklin, A., Dunning, M., & Seymour, M. (2014). The efficacy of an intervention for the management of postpartum fatigue. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 43(5), 598–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12489

- Giallo, R., Rose, N., & Vittorino, R. (2011). Fatigue, wellbeing and parenting in mothers of infants and toddlers with sleep problems. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2011.593030

- Hauck, Y. L., Hall, W. A., Dhaliwal, S. S., Bennett, E., & Wells, G. (2012). The effectiveness of an early parenting intervention for mothers with infants with sleep and settling concerns: A prospective non‐equivalent before‐after design. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(1‐2), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03734.x

- Hiscock, H., Bayer, J., Gold, L., Hampton, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Wake, M. (2007). Improving infant sleep and maternal mental health: A cluster randomised trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92(11), 952–958. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.099812

- Hiscock, H., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sleeping like a baby? Infant sleep: Impact on caregivers and current controversies. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 51(4), 361–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12752

- Keuroghlian, A. S., Gunderson, J. G., Pagano, M. E., Markowitz, J. C., Ansell, E. B., Shea, M. T., Morey, L. C., Sanislow, C., Grilo, C. M., & Stout, R. L. (2015). Interactions of borderline personality disorder and anxiety disorders over 10 years. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(11), 1529–1534. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09748

- Kurth, E., Kennedy, H. P., Spichiger, E., Hösli, I., & Stutz, E. Z. (2011). Crying babies, tired mothers: What do we know? A systematic review. Midwifery, 27(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2009.05.012

- Leichsenring, F., Leibing, E., Kruse, J., New, A. S., & Leweke, F. (2011). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 377(9759), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5

- Matthey, S. (2008). Using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale to screen for anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 25(11), 926–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20415

- Middlemiss, W., Stevens, H., Ridgway, L., McDonald, S., & Koussa, M. (2017). Response-based sleep intervention: Helping infants sleep without making them cry. Early Human Development, 108, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.03.008

- Morrell, J., & Steele, H. (2003). The role of attachment security, temperament, maternal perception, and care‐giving behavior in persistent infant sleeping problems. Infant Mental Health Journal: Official Publication of the World Association for Infant Mental Health, 24(5), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.10072

- Rowe, H. J., & Fisher, J. R. (2010). The contribution of Australian residential early parenting centres to comprehensive mental health care for mothers of infants: Evidence from a prospective study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 4(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-4-6

- Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sanson, A., Prior, M., Oberklaid, F., & Smart, D. (1998). Temperamental influences on psychosocial adjustment: From infancy to adolescence. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 15(2), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0816512200027929

- Sarah Oldbury, R., SCPHN, M. P., & Karen Adams, R. (2015). The impact of infant crying on the parent-infant relationship. Community Practitioner, 88(3), 29.

- Treyvaud, K., Rogers, S., Matthews, J., & Allen, B. (2009). Outcomes following an early parenting center residential parenting program. Journal of Family Nursing, 15(4), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840709350878

- Wynter, K., Tran, T. D., Rowe, H., & Fisher, J. (2017). Development and properties of a brief scale to assess intimate partner relationship in the postnatal period. Journal of Affective Disorders, 215, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.001

- Zanarini, M. C., Vujanovic, A. A., Parachini, E. A., Boulanger, J. L., Frankenburg, F. R., & Hennen, J. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(6), 568–573. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355