ABSTRACT

Aims/Background

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has placed emphasis on improving early child development globally. This is supported through the Nurturing Care Framework which includes responsive caregiving. To evaluate responsive caregiving, tools to assess quality of caregiver-child interactions are used, however there is little information on how they are currently employed and/or adapted particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where children have a greater risk of adverse outcomes. The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive guide on methodologies used to evaluate caregiver-child interaction – including their feasibility and cultural adaptation.

Design/Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies over 20years in LMICs which assessed caregiver-child interactions. Characteristics of each tool, their validity (assessed with COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist), and the quality of the study (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) are reported.

Results

We identified 59 studies using 34 tools across 20 different LMICs. Most tools (86.5%) employed video-recorded observations of caregiver-child interactions at home (e.g. Ainsworth’s Sensitivity Scale, OMI) or in the laboratory (e.g. PICCOLO) with a few conducting direct observations in the field (e.g. OMCI, HOME); 13.5% were self-reported. Tools varied in methodology with limited or no mention of validity and reliability. Most tools are developed in Western countries and have not been culturally validated for use in LMIC settings.

Conclusion

There are limited caregiver-child interaction measures used in LMIC settings, with only some locally validated locally. Future studies should aim to ensure better validity, applicability and feasibility of caregiver-child interaction tools for global settings.

Introduction

Promoting better outcomes for early childhood development has finally reached global significance, as evidenced by its inclusion in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (ONU SDGs, https://sdgs.un.org/goals). In particular, SDG 4.2.1 aims to improve the number of children ‘developmentally on-track’ globally. With current estimates of over 250 million children below the age of 5 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) at risk of not reaching their full developmental potential, promoting better outcomes is paramount for governments and institutions (Black et al., Citation2017). The Nurturing Care Framework (NCF), recently devised by leading international organisations including UNICEF, the World Bank and the World Health Organisation (WHO) highlights five key areas of focus (i.e. good health, adequate nutrition, responsive caregiving, security and safety, and opportunities for early learning) which, if instituted, could improve childhood development outcomes. ‘Responsive caregiving’ is one such area, and it is defined in the NCF as ‘observing and responding to children’s movements, sounds and gestures and verbal requests’ and ‘fostering a relationship of trust with the child and protecting against injury and illness’ (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Research clearly demonstrates how essential this supportive caregiver-child relationship is for promoting child development (Aboud & Yousafzai, Citation2015; Deans, Citation2020; Mesman et al., Citation2012; Rao et al., Citation2013; Rocha et al., Citation2020) and how parenting programmes designed to support responsive caregiving can effect change in development trajectories (Britto et al., Citation2017). If agencies are to evaluate such interventions, initial and follow-up assessments of the quality of the interactions between caregivers and their children, often termed maternal-child interaction or parent-child interaction), is crucial.

Establishing the quality of caregiver-child interactions (CCI) involves assessing how caregivers comfort, guide, and respond to the child, how children contribute to the interaction with their behaviour, communication and affect, and what level of synchrony and mismatch there is between the two interactants. CCI has historically been assessed in psychological sciences since the 1970s either through direct observation of interactions between children and their caregivers or through administering questionnaires asking about characteristics of such interactions. Research has demonstrated how caregiver responsiveness (or sensitivity) promotes a secure environment where children feel safe to explore and learn and can be confident that their needs will be met and that distress will be responded to (Mesman et al., Citation2012). These supportive interactions have been shown to either directly positively influence child development or moderate the association between risk factors for child development (e.g. difficult socio-economic background, family violence, child temperamental difficulties, genetic predispositions) and child socio-emotional outcomes (Deans, Citation2020; Rocha et al., Citation2020).

However, this knowledge comes mainly from Western and high-income settings, and more research based in LAMICs is needed to determine whether the association between characteristics of caregiver-child interaction and child outcomes are universal or culturally influenced.

Since this line of research is relatively new, researchers who start planning their study face a series of methodological decisions and challenges which include what dimensions of caregiver-child interaction to assess (e.g. maternal responses to emotions, child vocalisations, synchrony) and how to assess them (e.g. direct observation, video-recordings, questionnaires). They might also question whether they should use tools developed in the target population or elsewhere and whether they should or should not culturally adapt such tools. Finally, they have to evaluate whether the use of their preferred methodology is feasibly applicable to the context where their research is based. In fact, many of the tools used to assess characteristics of interactions require high levels of training and resources, which may be more challenging to source and implement in LMICs (Hirsh-Pasek & Burchinal, Citation2006; Shaw et al., Citation1994).

Whilst several tools have been developed for assessing the quality and characteristics of CCI in high-income settings, there is limited research from LMICs (Scherer et al., Citation2019). Anthropological evidence has previously demonstrated that caregivers in different cultural settings may respond to their infants in very different ways. For example, many non-Western caregivers do not respond ‘en face’ to their infants or might use fewer of what are called ‘distal responses’ (e.g. vocalisations, smiles, talking) as in Western settings. Instead, caregivers from other cultures may have different responsive rhythms or ways of looking, and may respond in a more ‘proximal’ manner (e.g. through touch, with body movements while carrying the children) (M. H. Bornstein, Putnick, & Suwalsky, Citation2012; Kärtner et al., Citation2008; Lancy, Citation2007; LeVine & New, Citation2008). Owing to the cultural and childrearing differences between populations, it remains unclear whether tools developed for use in high-income settings maintain their validity in LMICs (Keller et al., Citation2018; Mesman et al., Citation2018; Mesman, Minter, et al., Citation2018). Presently, there is a dearth of literature which provides evidence on how well tools developed in Western settings predict infant outcomes and whether these work in the same way as culturally adapted scales. Furthermore, there is still a dearth of empirical literature on whether the same constructs of parenting predict the same outcomes in different cultural contexts. Therefore, whether cultural adaptation of tools is necessary has been mainly confined to theoretical debate: supporters of the universalist approach sustain that core parenting constructs are relevant across cultures and no adaptation is necessary, while opponents to this approach believe that same parenting dimensions may have different cultural meanings so adaptation is necessary (Bernstein et al., Citation2005; Keller et al., Citation2018; Mesman et al., Citation2018, Citation2018).

A recently published scoping review on tools assessing at least one nurturing care areas of focus in LMICs reported that only a minority of studies (36.5%) assessed the area ‘responsive caregiving’ (Jeong et al., Citation2022). The authors also highlighted that the tools used to measure responsive caregiving were the ones with greater variability, compared to the ones used to measure other Nurturing Care Framework areas. The authors make clear that there is a need for an easy-to-read summary of tools which provides much more detail to inform and support researchers who want to conduct research on parenting in LMICs and select which assessment tool to use.

Aims

This review aims to collate the existing literature on tools used to assess CCI in LMICs to determine which tools are currently being implemented. In this present paper, we will describe the types of tools used to measure CCI in LMICs (which tools and characteristics of those tools), and the way in which the tool was used (their methodology), whether there has been any attempt to adapt or culturally validate the tool (cultural adaptation), and practical aspects of the tool such as cost and training (to inform on feasibility of use). Finally, we will assess the quality of the studies identified in order to provide comprehensive reference tables to enable the reader to better understand the state of the use of these tools in LMICs presently.

Materials and methods

This review was conducted as per the PRISMA protocol for a systematic review (Moher et al., Citation2015). A protocol for the study was registered prior to commencing the review, which outlined the review question, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, risk of bias assessment and strategy for data synthesis (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display record.php?ID=CRD42021244525). There were small deviations from the study protocol. With regards to the study characteristics, the following were extracted in addition to those listed in the protocol: “setting, country of origin, scoring system’. With regards to assessing feasibility of the studies, the following was extracted in addition to those listed in the protocol: ‘post assessment requirements’. These additions were made to enhance the readers understanding of the studies. Furthermore, with the COSMIN tool, ‘Measurement error’ was removed from the list of assessed properties of each paper as it was not felt to be relevant to the studies assessed”.

For the purposes of the study, we defined CCI as any form of reciprocal interaction between a caregiver (typically the mother, but not necessarily so) and his/her child in the context of parental behaviour and childhood development. This definition includes, but is not limited to, the concept of responsive caregiving or sensitivity (i.e. the caregiver’s ability to appropriately interpret and promptly respond to children’s cues (Ainsworth et al., Citation1974; Black & Aboud, Citation2011; Eshel et al., Citation2006)) widely used in literature on parenting. Assessments of CCI also included maternal and child specific behaviours (e.g. vocalisations, smiles, gaze direction), features of parenting other than sensitivity (e.g. intrusiveness, detachment, stimulation, affection, encouragement) and dyadic dimensions (e.g. synchrony, atmosphere). Furthermore, for the purpose of the present paper, the term ‘tool’ is defined as any method used to measure or quantify characteristics and quality of CCI in a structured, reproducible way, which was at least partially described within the study and produced quantitative data as a result.

Search strategy

We aimed to review all studies available in the English language, which included an assessment of CCI. We limited our results to papers published over 20 years between NaN Invalid Date and NaN Invalid Date . This enabled us to include as many papers as possible without extracting data from research that may no longer be culturally or scientifically relevant. Publications were included if they met the following criteria: a) studies which involved families with children up to the age of 5, given that it has been established that indicators of childhood development up to this age have been linked to poor outcomes in later life (Grantham McGregor et al., Citation2007); b) studies conducted (or at least partially conducted) in countries of low or low-middle income, as defined by the World Bank (Appendix 1); c) studies including tools which generate a form of quantitative data, regardless of the specific study design; d) studies which included CCI as either a predictor or an outcome within their design.

To perform a broad search of the literature, the database search tool HDAS (Healthcare Databases Advanced Search) was used to search the databases; Medline, PsychINFO, and CINAHL. The search terms used for each database are outlined in Appendix 2. Other methods of gathering papers included snowballing through a review of the reference list of the papers included in the systematic review.

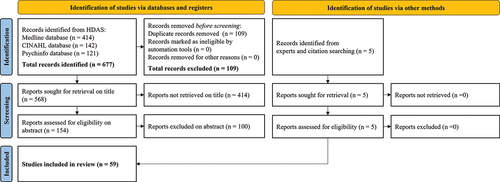

We then performed a screen on the resulting papers based initially on the title, then abstract and full text, in line with our inclusion and exclusion criteria. This was performed by CL, MG and YO, with each paper screened by two reviewers. The PRISMA flow diagram for the search can be found in .

Analysis of results

Three reviewers screened a sample of 10% of the papers with agreement rates were above 90%.

To assess the quality of each paper, we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Citation2018). We evaluated the quality of each study based on its overall design, and the quality of each tool within the study. Where multiple appropriate tools were identified within one study, we evaluated the use of each one separately.

To assess the quality of the tools themselves, LB, MG and CL used an abridged version of the COSMIN risk of bias checklist, selecting the components which we felt were relevant to this review. A number of tools were double-rated by two members of the team, and then two meetings were convened to compare ratings to ensure consistency. We also extracted for reference information on practical aspects of the usage of the tools and the characteristics of the studies themselves.

Results

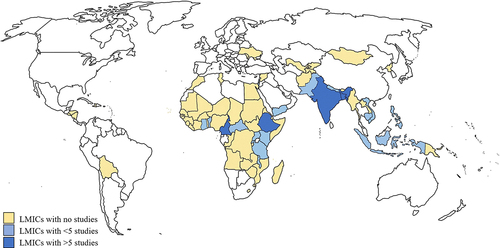

We identified 59 studies that matched the inclusion criteria with 34 tools or coding schemes. These tools varied greatly in their characteristics, such as design, location of origin and application, and age range of participants each tool can be applied to, with the information provided in . Similarly, the studies utilising these tools adopted various methodologies and designs and were conducted in different locations with variability in the age range of children (). depicts the geographical spread of the setting of studies across 20 countries, with many studies from South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia) and quite a few from Ethiopia and Cameroon – often with the same team having used different tools in the same setting. None of the included papers reported conflicts of interest.

Table 1. Characteristics of tools included in the review.

Tools and methodologies

The concept of CCI, and how its characteristics and quality are measured are broad and multifaceted. This is reflected in the variety of tools and methodologies identified by this review. We categorised the 34 tools employed in 59 studies conducted in a LMICs setting based on their approach to data collection – specifically, whether the tool utilised an observational (28 tools − 82.4%) or a self-report approach (6 tools − 17.6%) (). Most studies used observational tools that allowed the assessment of CCIs either live in the field (18, 30.5%) or at a later point using videotaped footage of the interactions (25, 42.3%). A minority, 7 studies (11.9%), used self-report tools relying upon the caregiver to provide an account or answer specific structured questions regarding how they interact with their child. Finally, one study used exclusively audio-registration (1.7%), and 8 studies used mixed methods employing more than one type of tool (13.6%) (a full list of studies and tools used within each study can be found in Appendix 3). Most of the 34 tools were developed in Western countries (17 in U.S.A., 11 in an European country) and only a few in LMICs (6 from studies conducted exclusively in one LMIC country and 7 in multi-country studies, including at least one LAMIC setting).

Observational methods/tools

Most studies (51, 86.5%) employed an observational method for the assessment of CCI, which involved using coding schemes to quantify caregiver and infant behaviours and to assess the quality of the interaction observed for a specific period. Some studies included existing tools, such as Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) (Aboud, Citation2007; Betancourt et al., Citation2020; Black et al., Citation2004, Citation2007; Boivin et al., Citation2013; Fernandez-Rao et al., Citation2014; Fisher et al., Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2017; Koura et al., Citation2013; Morris et al., Citation2012; Rasheed & Yousafzai, Citation2015; Scherer et al., Citation2019; Yousafzai et al., Citation2015; Zevalkink & Riksen-Walraven, Citation2001; Zevalkink et al., Citation2008); the Observation of Maternal Child Interaction (OMCI) (Betancourt et al., Citation2020; Brown et al., Citation2017; Obradović et al., Citation2016; Rasheed & Yousafzai, Citation2015; Scherer et al., Citation2019; Yousafzai et al., Citation2015); the Observation of Mediational Interaction (OMI) (Boivin et al., Citation2013; Klein & Rye, Citation2004); the Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training (NCAST) (Frith et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Ilagan, Citation2003); the Coding Interactive Behaviour (CIB) (Feldman & Vengrober, Citation2011); the Ainsworth’s Sensitivity Scales (Alsarhi et al., Citation2021; Mesman, Minter, et al., Citation2018; Rahma et al., Citation2018; Zevalkink & Riksen-Walraven, Citation2001); the Global Rating Scales (GRS) (Knight, Citation2016; Nayak et al., Citation2019); and coding systems such as that developed by (Moore et al., Citation2006, Citation2006).

A number of other studies have used new bespoke coding schemes developed for the purpose of their individual research study (Bornstein et al., Citation2015; Broesch et al., Citation2016; Kärtner et al., Citation2008; Liebal et al., Citation2011). Within these studies, a variety of methods were used to code the observations, as well as a variety of source materials (video or audio), and variation in where the coding of observations took place (real time observations in the field vs recordings after the interaction took place), and finally, in the type of scoring framework used (rate of specific behaviours observed, such as emotional expressions, verbalisations, smiles, soothing, or global scales assessing interactional characteristics, such as caregiver sensitivity, intrusiveness, warmth) (). There were numerous different settings used for observing the participants interacting. This included during feeding, play, book sharing, storytelling, or completely unstructured activities guided by the participants. In terms of setting, some studies chose to observe the interactions in a completely naturalistic manner, following the caregiver-child dyad as they completed their daily activities at home, whilst others confined observation to semi-structured activities (e.g. play, feeding) either at home or in the research site lab.

In lieu of videotaping observations-costly in terms of time and resources, several studies used more abridged methods that allowed interactions to be observed and coded by a trained researcher on site. The tool most commonly used was the HOME (Caldwell & Bradley, Citation1984), specifically the HOME-IT (infant and toddlers) edition. The HOME inventory is designed to assess multiple elements of a child’s home environment, including learning materials, stimulation and variety provided by the caregiver. For the purposes of this review, we identified studies that used the parental responsiveness section of the HOME inventory.

Self-report methods/tools

Despite most studies opting for an observational design, some studies use self-report methods of assessing characteristics of CCI. Some self-reported measures were completed by the participants themselves, but the majority were completed by assessors on behalf of the participants (often due to language and literacy barriers). For example, one team from Palestine (Punamäki et al., Citation2017) read out questions to mothers from the Emotional Availability Self Report (EA-SR; (Biringen et al., Citation2002)). This 28-item questionnaire provides statements such as; ‘My baby likes to be with me most of the time’ or ‘It is hard to soothe my baby’. Another study in Bangalore, India studying the association between quality of mother-child interaction and postpartum psychosis used the Stafford interview (also known as the Birmingham interview for Maternal Mental Health (Brockington, Citation1996)) using semi-structured interviews with probes to assess dimensions, e.g. maternal involvement in infant’s care, feelings towards their infants, child abuse and anger expressed towards infants. provides full details of all methodologies used in studies included in this review.

Cultural adaptation

Apart from a few exceptions (Aboud, Citation2007; Hamadani et al., Citation2006; Moore et al., Citation2006; Nti & Lartey, Citation2007; Wogene, Citation2012; Yousafzai et al., Citation2015), almost all the tools and coding schemes used were originally developed in Western settings (). We have identified the following tools created in LMIC settings; the OMCI developed in Pakistan, The Mother-Child Picture Talk task (Aboud, Citation2007) developed in Bangladesh, a parenting questionnaire to assess knowledge of child development and child-rearing practices (Hamadani et al., Citation2006; Nahar et al., Citation2015), three coding systems focussed one on maternal and child behaviours developed in Ethiopia (Wogene, Citation2012) and two on responsive feeding, one developed in Ghana (Nti & Lartey, Citation2007) and the other developed in Bangladesh (Moore et al., Citation2006). These more indigenous tools were created utilising previous Western tools or with leadership from a Western setting.

Some cross-cultural studies did adapt coding schemes to the specific cultural setting the study was situated in, rather than using standard tools such as NCAST or OMI. One study in Palestine used assessors to follow the child and videotaped maternal and child behaviours using the ‘Coding for interactive behaviour’ (Fieldman, Citation1998). They adapted it with the team in Palestine re-coding for emotional state, narrative coherence, awareness of the child’s distress and the child’s emotions and behaviours to trauma reminders (Feldman & Vengrober, Citation2011). A study across 11 countries, including Argentina, U.S.A., Italy and Cameroon, assessed mean levels of mother and infant vocalisations (at 5 ½ months of age) and associations between them. In this study, the process was adapted so that video recording in the home ‘aimed to be representative of typical routine and behaviour’ with the only people at home being the mother, infant and the videographer, who was from the same community as the dyad being filmed (Bornstein et al., Citation2015). The coding was standard throughout all countries. Similarly, in a study across Kenya, Fiji and the U.S.A., CCI was assessed through recording videos in houses or outdoor areas with mothers and infants seated on the floor or ground and told only ‘to keep the infant content for about 10 minutes’ (Broesch et al., Citation2016). The team defined categories of responsiveness (e.g. tactile/verbal responsiveness) by carefully determining a repertoire of possible behaviours from each country individually and coding them specifically for each country. Finally, Meehan and Hawks (Citation2013) describe a very culturally sensitive process of using naturalistic observations in a culturally relevant manner in order to ensure that the cultural context of early childhood experiences were explored in a way that are not possible to explore using traditional measurements (Meehan & Hawks, Citation2013). This study particularly focussed on cooperative caregiving or ‘allomaternal’ care meaning care by any group caregiver other than the mother in Aka families in Central African Republic. The team recorded rates of holding, touching, and proximity in mothers but also did so with all allomaternal caregivers (Meehan & Hawks, Citation2013).

Practical considerations for use of each tool

The training and time required to complete assessment using the tools we identified varied considerably (). The average time needed to complete the assessments was 36.6 (SD 43.3) min, ranging from 4–5 minto 2 ½ h. Most tools (24, 70.6%) required only one assessor onsite, 5 tools (14.7%) required two assessors, while the remaining 5 (14.7%) did not specify how many assessors were needed. Almost half (15, 44.1%) of the tools required a video camera. Five tools (Coding system adapted from Belsky et al., Citation1984; Coding system developed by Broesch et al., Citation2016; Coding system developed by Gratier, (Citation2003) and Coding system developed by Klein and Hundeide (Citation1996) and Wörmann et al. (Citation2012) required additional software such as a cell phone application, event-recording software, digital audio tape recorder, Cool Edit Pro version 1.1, and the INTERACT 9.0.7 software (Klein & Hundeide, Citation1996; Wörmann et al., Citation2012). Half of the tools identified (17, 50%) did not require special equipment. In terms of post-assessment and training, almost half of the tools (14, 41.2%) required further review and assessment mainly of the coding of videotapes, while twelve tools (35.3%) do not require any post-assessment. The post-assessment mostly involved training to use specific coding schemes and obtaining inter-rater reliability for each of the codes used, as well as quality check processes.

Table 2. Practical considerations and feasibility for use of each tool.

In terms of cost, five tools (14.7%) have a clearly specified cost (Brockington, Citation1996; Caldwell & Bradley, Citation1984, Citation2003; Hughes et al., Citation2005; Murray et al., Citation1996; Rempel & Rempel, Citation2011; Roggman et al., Citation2013), while this was unclear for the majority (27, 79.5%). Many tools were used within specific research environments and were not necessarily created to scale-up or future proprietary use. One of the few tools which had a cost varied in price between $ 65–$75 for a manual and forms.

Quality of tools and studies

The overall quality of the studies was assessed using MMAT (Hong et al., Citation2018) We found that most studies were of an acceptable level of quality (overall mean MMAT score 70.3%, SD 21.3%), with a full quality description included in Appendix 3.

The methodological quality of the tools was further assessed using the COSMIN risk of bias checklist (). This checklist rates the robustness of specific ‘measurement properties’ outlined for each tool in each paper, including structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity, reliability, criterion validity, construct validity and responsiveness (Mokkink et al., Citation2018). We found that most studies had either not commented on these measurement properties for the tools they used or had not used appropriate or robust statistical methods to assess them. The tools which better demonstrated data on their validity and had less risk of bias as per COSMIN were generally those that did not require video coding – these include the HOME inventory, the EA-SR and the OMCI (Biringen, Citation2008; Caldwell & Bradley, Citation1984; Rasheed & Yousafzai, Citation2015). In particular, very few studies actually adapted or validated their coding systems for use in other cross-cultural settings where they were working (Caldwell & Bradley, Citation1984, Citation2003; Fieldman, Citation1998; Moore et al., Citation2006; Sumner, Citation1994). Often this is because videos are taken but coded by researchers from Western settings rather than local coders. Some attempts to be more culturally sensitive do exist, including those studies (Lavelli et al., Citation2019a) which used specific culture-sensitive coding systems such as the one developed by Carra and colleagues (Citation2012) in Cameroon (Lavelli et al., Citation2019b) where the team captured the variety of emotional expressions and actions shown by mothers in different socio-cultural contexts and ensured the meaning was culturally relevant to local coders. Further details can be seen in .

Table 3. Summary of COSMIN risk of bias checklist scores for each measurement property, per tool/methodology.

Discussion

In this review, we identified a wide variety of tools and methodologies used for the assessment of the quality and characteristics of the interaction between caregivers and infants in LMIC countries. We identified a wide variation in how the interactions were observed (ranging from naturalistic observation of daily activity to a contrived environment created by the experimenters), and coded (using global scales or counts of behaviours). In addition, most of the studies used coding systems developed and established in Western settings, with only a few employing rating systems developed in or adapted to the cultural setting in which they were used. Finally, methodologies used for assessment varied in their feasibility; these ranged from brief self-report questionnaires, with little time and training required, to coding systems, which required large periods of time, training, and specialised equipment. Notably, most of the studies reviewed assessed the quality of mother-child interactions with only few of them including other caregivers in their samples (Giannotti et al., Citation2022). It is clear that there is a need to understand tools which may better describe the impact of a wider caregiving environment and multiple caregiver child interactions on children’s developmental outcomes, especially in societies where the caring responsibilities of children are shared with the wider family or community.

Many studies opted to create novel methods of assessment, often without a robust level of reporting on the process of development or the reliability and validity of the tool itself. Overall, the high level of heterogeneity in the methodologies used and in study designs reflects a lack of standardisation or expert consensus on how best to assess caregiver-child interaction quality in these settings, as well as a disparity in what elements of interaction are fundamentally important for child development. This lack of consensus in the approach makes cross-study comparability very difficult. Finally, there was a surprising lack of diversity in the settings for the studies. As depicts, most of the LMICs included in our search were not represented amongst our final list of studies, whereas countries such as India, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia were included several times. This may be due to certain research groups publishing multiple outcome papers. It does highlight a paucity in the representation of many LMIC settings in this field.

The debates relating to the conceptualisation of CCI and the way it is measured are presently being highlighted in the literature – particularly with the recent global interest in the Nurturing Care Framework (Keller et al., Citation2018; Mesman et al., Citation2018, Citation2018). Proponents have argued that some of the constructs used in the field of parenting and infant development may not be valid across cultures and have debated whether the form of maternal behaviours observed in different cultures may vary even if the function may be the same (Bornstein & Cote, Citation2003; M. H. Bornstein, Putnick, & Suwalsky, Citation2012; Bozicevic et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, some also argue that the methodology that is used to assess it is variable, as we have identified in this paper, and furthermore may also not be valid across different populations. For example, naturalistic observation may provide very different information regarding parent-child interaction if one uses a play-based task in a setting where an infant would not normally be provided with toys to play with, or where the concept of play is culturally different from the Western concept.

Understanding the cultural conception of caregiver-child interaction is the first step before examining the predictive validity of theoretically important aspects of CCI for later child outcomes in different cultural settings. We noted that the majority of tools and methodologies identified in this review were developed in high income countries and little time or effort was spent on considering the conceptual context of caregiver-child interaction. We found that very few studies culturally adapted their methodologies, and when they did, even fewer tested and reported their reliability and cultural validity systematically. There are, however, some examples, mainly using statistical techniques and large data sets to compare responses from different countries. For instance, Jones et al. (Citation2017) examined the measurement equivalence and invariance and the differential item functioning of the HOME inventory across eight international sites. The authors found that HOME scores measured emotional and verbal responsibility in six sites, while these scores lacked structural validity in two sites. Also, using different factor analysis techniques, the HOME inventory had an internal consistency ≥ 0.70 (Jones et al., Citation2017).

Despite most methodologies being developed in high-income countries, there were few notable tools developed in LMICs which were highlighted in this review. These include the OMCI (Yousafzai et al., Citation2015), The Mother-Child Picture Talk task (Aboud, Citation2007), a parenting questionnaire to assess knowledge (Hamadani et al., Citation2010), and a coding system focused on responsive feeding (Moore et al., Citation2006; Nti & Lartey, Citation2007; Wogene, Citation2012). The OMCI was developed in Pakistan for the express purpose of providing a method of assessing CCI that could be used in a low-income setting. It involves assessing live observations in a way which does not require a high level of assessor training or specialist equipment that may be harder to source in LMIC settings. Using a short book-sharing activity as the basis for the interaction, both maternal and child behaviours are assessed by a trained assessor to create a composite score that rates the responsiveness of the interaction. In our review, studies using this tool were of good quality (mean MMAT score 76.7%, SD 23.4%), and the tool itself scored comparatively high in terms of validity and reliability in Pakistan. Unfortunately, the validity of other methodologies developed in LMICs, such as The Mother-Child Picture Talk task (Aboud, Citation2007), the parenting questionnaire (Hamadani et al., Citation2010), and the responsive feeding coding system (Moore et al., Citation2006; Nti & Lartey, Citation2007; Wogene, Citation2012) were not formally evaluated either in the cultural setting where they were created or elsewhere.

It is important to highlight that the literature is still limited regarding whether adaptation of tools to assess caregiving environment is needed or whether scales developed in Western/high-income settings are valid in non-Western/LMIC countries. In fact, more research is needed to determine how well different scales predict infant outcomes compared to adapted scales, which would give researchers more insight into this matter.

We used the COSMIN risk of bias checklist to assess the reliability and validity of the tools and methodologies themselves, as reported by each study. This is a systematic method for patient-reported outcome measures and involves assessing whether each study has reported a number of measurement properties (See ) and, secondly, what level of quality they are if reported. Overall, we found that very few studies referred to these measurement properties or attempted to assess or report on them in their results. Of the studies that did, few scored highly in these areas. This may reflect a seemingly absent gold standard in the field that studies must meet. We found the most well-validated tool in our review to be the HOME inventory. This tool uses an established methodology that has been used in many different settings and for various purposes. It is interesting to consider whether the push for more automated tools that measure caregiver responsiveness through coding and artificial intelligence will help with this, particularly now that we can use video capture so much more freely for longer periods of time in home settings. The issue may still be complicated by the need to further understand and conceptualise responsive caregiving across settings, and any new automated coding framework may not take this into account. This approach has been promoted for measuring caregiver-child synchrony patterns and will be interesting to explore, but we must ensure that the concepts we assume the machine to be coding are universal, and if not, that this is taken into account (Leclère et al., Citation2014).

Strengths of the study

We have conducted a broad systematic review using detailed search criteria (including by country through World Bank criteria) with three reviewers. This has enabled us to uncover a variety of different of methodologies used to measure caregiver responsivity across a variety of settings in LMIC settings. We conducted a robust assessment of the quality of the studies using the MMAT as well as utilising the COSMIN criteria to look at the validation of measures used across settings.

Limitations of the study

There were several limitations to this study. Firstly, the review only included studies conducted in low and low- middle-income countries. This therefore excluded data from settings such as South Africa, classed as an upper middle-income country despite it having areas of low income comparable to other countries included in our review. Indeed, there have been several notable South African studies on CCI which were excluded from this review (Bozicevic et al., Citation2021; Dowdall et al., Citation2017; Murray et al., Citation2016; Tomlinson et al., Citation2020). Moreover, definitions were based on world bank classifications from the time of completing the first search of the literature, which have since been updated and may differ slightly from the world bank classifications at the time of publication. Finally, we were only able to screen publications written in the English language, which may have limited the results from non-English speaking countries.

Conclusion

In summary, we have conducted a detailed systematic review of the literature on the use of tools to assess the quality and characteristics of caregiver-child interactions across low-resource settings. It emerged that there is limited use of these measures; few originate from non-Western cultural settings and almost all tools originating either indigenously or from Western settings are not well validated for the country they are used in or validated across countries. Further research needs to be conducted to understand whether some of the simpler more feasible tools are valid across settings using more rigorous criteria and ensuring that the cultural conceptualisation of caregiving for the specific setting is also considered within its use.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2024.2321615.

References

- Aboud, F. E. (2007). Evaluation of an early childhood parenting programme in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 25(1), 3–13.

- Aboud, F. E., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2015). Global health and development in early childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 433–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015128

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: ‘socialisation’ as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In M. P. M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (2nd ed., pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press.

- Aldred, C., Green, J., & Adams, C. (2004). A new social communication intervention for children with autism: Pilot randomised controlled treatment study suggesting effectiveness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(8), 1420–1430.

- Alsarhi, K., Rahma, Prevoo, M., Alink, L., & Mesman, J. (2021). Observing sensitivity in slums in Yemen: The veiled challenge. Attachment & Human Development, 23(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1454058

- Beatty, J. R., Stacks, A. M., Partridge, T., Tzilos, G. K., Loree, A., & Ondersma, S. J. (2011). LoTTS parent–infant interaction coding scale: Ease of use and reliability in a sample of high‐risk mothers and their infants. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(1), 86–90.

- Belsky, J., Taylor, D. G., & Rovine, M. (1984). The Pennsylvania infant and family development project, II: The development of reciprocal interaction in the mother-infant dyad. Child Development, 706–717.

- Bernstein, V. J., Harris, E. J., Long, C. W., Iida, E., & Hans, S. L. (2005). Issues in the multi-cultural assessment of parent–child interaction: An exploratory study from the starting early starting smart collaboration. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26(3), 241–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.02.002

- Betancourt, T. S., Jensen, S. K., Barnhart, D. A., Brennan, R. T., Murray, S. M., Yousafzai, A. K., Farrar, J., Godfroid, K., Bazubagira, S. M., Rawlings, L. B., Wilson, B., Sezibera, V., & Kamurase, A. (2020). Promoting parent-child relationships and preventing violence via home-visiting: A pre-post cluster randomised trial among Rwandan families linked to social protection programmes. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 621. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08693-7

- Biringen, Z. (2008). Emotional availability (EA) scales (4th ed.). Unpublished Manual.

- Biringen, Z., Vliegen, N., Bijttebier, P., & Cluckers, G. (2002). The emotional availability self-report (EAS). https://www.emotionalavailability.com.

- Black, M. M., & Aboud, F. E. (2011). Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. The Journal of Nutrition, 141(3), 490–494. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.129973

- Black, M. M., Baqui, A. H., Zaman, K., McNary, S. W., Le, K., Arifeen, S. E., Black, R. E., Parveen, M., Yunus, M., & Black, R. E. (2007). Depressive symptoms among rural Bangladeshi mothers: Implications for infant development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(8), 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01752.x

- Black, M. M., Sazawal, S., Black, R. E., Khosla, S., Kumar, J., & Menon, V. (2004). Cognitive and motor development among small-for-gestational-age infants: Impact of zinc supplementation, birth weight, and caregiving practices. Pediatrics, 113(5), 1297–1305. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1297

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., Fink, G., Shawar, Y. R., Shiffman, J., Devercelli, A. E., Wodon, Q. T., Vargas-Barón, E., & Grantham McGregor, S. (2017). Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. The Lancet, 389(10064), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

- Boivin, M. J., Bangirana, P., Nakasujja, N., Page, C. F., Shohet, C., Givon, D., & Klein, P. S. (2013). A year-long caregiver training program to improve neurocognition in preschool Ugandan HIV-exposed children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(4), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e318285fba9

- Bornstein, M. H., & Cote, L. R. (2003). Cultural and parenting cognitions in acculturating cultures: 2. Patterns of prediction and structural coherence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(3), 350–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103034003007

- Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., Cote, L. R., Haynes, O. M., & Suwalsky, J. T. (2015). Mother-infant contingent vocalizations in 11 countries. Psychological Science, 26(8), 1272–1284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615586796

- Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., & Suwalsky, J. T. (2012). A longitudinal process analysis of mother-child emotional relationships in a rural Appalachian European American community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9479-1

- Bozicevic, L., De Pascalis, L., Montirosso, R., Ferrari, P. F., Giusti, L., Cooper, P. J., & Murray, L. (2021). Sculpting culture: Early maternal responsiveness and child emotion regulation – a UK-Italy comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 52(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022120971353

- Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Bhutta, Z. A., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. The Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3

- Brockington, I. (1996). Motherhood and mental health. Oxford University Press.

- Broesch, T., Rochat, P., Olah, K., Broesch, J., & Henrich, J. (2016). Similarities and differences in maternal responsiveness in three societies: Evidence from Fiji, Kenya, and the United States. Child Development, 87(3), 700–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12501

- Brown, N., Finch, J. E., Obradović, J., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2017). Maternal care mediates the effects of nutrition and responsive stimulation interventions on young children’s growth. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(4), 577–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12466

- Caldwell, B. M., & Bradley, R. H. (1984). Administration manual: Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas at little Rock.

- Caldwell, B. M., & Bradley, R. H. (2003). HOME inventory administration manual. Print Design Inc.

- Carra, C., Lavelli, M., & Keller, H. (2012). Cross-cultural coding scheme for mothers’ behaviors during spontaneous interaction with their infants. Unpublished manuscript, University of Verona and and University of Osnabrück.

- Deans, C. L. (2020). Maternal sensitivity, its relationship with child outcomes, and interventions that address it: A systematic literature review. Early Child Development and Care, 190(2), 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1465415

- Dowdall, N., Cooper, P. J., Tomlinson, M., Skeen, S., Gardner, F., & Murray, L. (2017). The benefits of early book sharing (BEBS) for child cognitive and socio-emotional development in South Africa: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1790-1

- Ensor, R., & Hughes, C. (2008). Content or connectedness? mother–child talk and early social understanding. Child Development, 79, 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01120.x

- Erickson, M. F., Sroufe, L. A., & Egeland, B. (1985). The relationship between quality of attachment and behaviour problems in preschool in a high-risk sample. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1–2, Serial No. 209), 147–166.

- Eshel, N., Daelmans, B., de Mello, M. C., & Martines, J. (2006). Responsive parenting: Interventions and outcomes. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 84(12), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.06.030163

- Feldman, R., & Vengrober, A. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in infants and young children exposed to war-related trauma. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(7), 645–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.03.001

- Fernandez-Rao, S., Hurley, K. M., Nair, K. M., Balakrishna, N., Radhakrishna, K. V., Ravinder, P., & Black, M. M. (2014). Integrating nutrition and early child-development interventions among infants and preschoolers in rural India. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences Journal, 1308(1), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12278

- Fieldman, R. (1998). Coding interactive behavior manual. Bar-Ilan University.

- Fisher, J., Tran, T., Luchters, S., Tran, T. D., Hipgrave, D. B., Hanieh, S., & Biggs, B. A. (2018). Addressing multiple modifiable risks through structured community-based learning clubs to improve maternal and infant health and infant development in rural Vietnam: Protocol for a parallel group cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 8(7), e023539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023539

- Frith, A. L., Naved, R. T., Ekström, E. C., Rasmussen, K. M., & Frongillo, E. A. (2009). Micronutrient supplementation affects maternal-infant feeding interactions and maternal distress in Bangladesh. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(1), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2008.26817

- Frith, A. L., Naved, R. T., Persson, L. A., Rasmussen, K. M., & Frongillo, E. A. (2012). Early participation in a prenatal food supplementation program ameliorates the negative association of food insecurity with quality of maternal-infant interaction. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(6), 1095–1101. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.155358

- Giannotti, M., Gemignani, M., Rigo, P., Venuti, P., & De Falco, S. (2022). The role of paternal involvement on behavioral sensitive responses and neurobiological activations in fathers: A systematic review. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 16, 820884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.820884

- Grantham McGregor, S., Cheung, Y. B., Cueto, S., Glewwe, P., Richter, L., & Strupp, B. (2007). Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. The Lancet, 369(9555), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4

- Gratier, M. (2003). Expressive timing and interactional synchrony between mothers and infants: Cultural similarities, cultural differences, and the immigration experience. Cognitive Development, 18(4), 533–554.

- Hamadani, J. D., Huda, S. N., Khatun, F., & Grantham McGregor, S. M. (2006). Psychosocial stimulation improves the development of undernourished children in rural Bangladesh. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(10), 2645–2652. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.10.2645

- Hamadani, J. D., Tofail, F., Hilaly, A., Huda, S. N., Engle, P., & Grantham McGregor, S. M. (2010). Use of family care indicators and their relationship with child development in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 28(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v28i1.4520

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Burchinal, M. (2006). Mother and caregiver sensitivity over time: Predicting language and academic outcomes with variable- and person-centered approaches. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(3), 449–485. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0027

- Holditch‐Davis, D., Schwartz, T., Black, B., & Scher, M. (2007). Correlates of mother–premature infant interactions. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(3), 333–346.

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Hughes, S. O., Power, T. G., Orlet Fisher, J., Mueller, S., & Nicklas, T. A. (2005). Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite, 44(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.08.007

- Ilagan, P. R. (2003). Maternal-infant interaction and intimate partner violence in Filipino mothers. University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center.

- Jeong, J., Bliznashka, L., Sullivan, E., Hentschel, E., Jeon, Y., Strong, K. L., Daelmans, B., & Nalecz, H. (2022). Measurement tools and indicators for assessing nurturing care for early childhood development: A scoping review. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(4), e0000373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000373

- Jones, P. C., Pendergast, L. L., Schaefer, B. A., Rasheed, M., Svensen, E., Scharf, R., & Murray-Kolb, L. E. (2017). Measuring home environments across cultures: Invariance of the HOME scale across eight international sites from the MAL-ED study. Journal of School Psychology, 64, 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.001

- Kärtner, J., Keller, H., Lamm, B., Abels, M., Yovsi, R. D., Chaudhary, N., & Su, Y. (2008). Similarities and differences in contingency experiences of 3-month-olds across sociocultural contexts. Infant Behavior and Development, 31(3), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.01.001

- Keller, H. (2007). Cultures of infancy. Erlbaum.

- Keller, H., Bard, K., Morelli, G., Chaudhary, N., Vicedo, M., Rosabal-Coto, M., Gottlieb, A. (2018). The myth of universal sensitive responsiveness: Comment on Mesman et al. (2017). Child Development, 89(5), 1921–1928. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13031

- Klein, P. S., & Hundeide, K. (1996). Early intervention: Cross-cultural experiences with a mediational approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Klein, P. S., & Rye, H. (2004). Interaction-oriented early intervention in Ethiopia: The MISC approach. Infants & Young Children, 17(4), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001163-200410000-00007

- Knight, E. (2016). Examining the Impact of an Emotional Stimulation Intervention on Interactions Between Ethiopian Mothers and Their Infants in the Context of Treatment for Malnutrition ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of East Anglia,

- Koura, K. G., Boivin, M. J., Davidson, L. L., Ouédraogo, S., Zoumenou, R., Alao, M. J., Garcia, A., Massougbodji, A., Cot, M., & Bodeau-Livinec, F. (2013). Usefulness of child development assessments for low-resource settings in francophone Africa. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(7), 486–493. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31829d211c

- Lancy, D. F. (2007). Accounting for variability in mother-child play. American Anthropologist, 109(2), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2007.109.2.273

- Lavelli, M., Carra, C., Rossi, G., & Keller, H. (2019a). Culture-specific development of early mother–infant emotional co-regulation: Italian, Cameroonian, and West African immigrant dyads. Developmental Psychology, 55(9), 1850. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000696

- Lavelli, M., Carra, C., Rossi, G., & Keller, H. (2019b). Culture-specific development of early mother–infant emotional co-regulation: Italian, Cameroonian, and West African immigrant dyads. Developmental Psychology, 55(9), 1850–1867. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000696

- Lavelli, M., & Fogel, A. (2005). Developmental changes in the relationship between the infant’s attention and emotion during early face-to-face communication: The 2-month transition. Developmental Psychology, 41, 265–280.

- Leclère, C., Viaux, S., Avril, M., Achard, C., Chetouani, M., Missonnier, S., Cohen, D., & Dekel, S. (2014). Why synchrony matters during mother-child interactions: A systematic review. Public Library of Science ONE, 9(12), e113571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113571

- LeVine, R. A., & New, R. S. (2008). Anthropology and child development: A cross-cultural reader. John Wiley & Sons.

- Liebal, K., Reddy, V., Hicks, K., Jonnalagadda, S., & Chintalapuri, B. (2011). Socialization goals and parental directives in infancy: The theory and the practice. Journal of Cognitive Education & Psychology, 10(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.10.1.113

- Meehan, C. L., & Hawks, S. (2013). Cooperative breeding and attachment among the aka foragers. In N. Quinn & J. M. Mageo (Eds.), Attachment reconsidered: Cultural perspectives on a Western theory (pp. 85–113). Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Mesman, J. (2018). Sense and sensitivity: A response to the commentary by Keller et al. Child Development, 89(5), 1929–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13030

- Mesman, J., Minter, T., Angnged, A., Cissé, I. A., Salali, G. D., & Migliano, A. B. (2018). Universality without uniformity: A culturally inclusive approach to sensitive responsiveness in infant caregiving. Child Development, 89(3), 837–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12795

- Mesman, J., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2012). Unequal in opportunity, equal in process: Parental sensitivity promotes positive child development in ethnic minority families. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00223.x

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., & Group, P. P. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Mokkink, L. B., Prinsen, C., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., De Vet, H. C., & Mokkink, L. (2018). COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). User Manual. https://cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-syst-review-for-PROMs-manual_version-1_feb-2018.pdf

- Moore, A. C., Akhter, S., & Aboud, F. E. (2006). Responsive complementary feeding in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine, 62(8), 1917–1930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.058

- Morris, J., Jones, L., Berrino, A., Jordans, M. J., Okema, L., & Crow, C. (2012). Does combining infant stimulation with emergency feeding improve psychosocial outcomes for displaced mothers and babies? A controlled evaluation from northern Uganda. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01168.x

- Murray, L., De Pascalis, L., Tomlinson, M., Vally, Z., Dadomo, H., MacLachlan, B., & Cooper, P. J. (2016). Randomized controlled trial of a book-sharing intervention in a deprived South African community: Effects on carer-infant interactions, and their relation to infant cognitive and socioemotional outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(12), 1370–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12605

- Murray, L., Fiori-Cowley, A., Hooper, R., & Cooper, P. (1996). The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Development, 67(5), 2512–2526. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131637

- Nahar, B., Hossain, I., Hamadani, J. D., Ahmed, T., Grantham McGregor, S., & Persson, L. A. (2015). Effect of a food supplementation and psychosocial stimulation trial for severely malnourished children on the level of maternal depressive symptoms in Bangladesh. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(3), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12176

- Nayak, B. S., Lewis, L. E., Margaret, B., Bhat, Y. R., D’Almeida, J., & Phagdol, T. (2019). Randomized controlled trial on effectiveness of mHealth (mobile/smartphone) based preterm home care program on developmental outcomes of preterms: Study protocol. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(2), 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13879

- Nti, C. A., & Lartey, A. (2007). Effect of caregiver feeding behaviours on child nutritional status in rural Ghana. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(3), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2006.00553.x

- Obradović, J., Yousafzai, A. K., Finch, J. E., & Rasheed, M. A. (2016). Maternal scaffolding and home stimulation: Key mediators of early intervention effects on children’s cognitive development. Developmental Psychology, 52(9), 1409–1421. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000182

- ONU SDGs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Punamäki, R. L., Isosävi, S., Qouta, S. R., Kuittinen, S., & Diab, S. Y. (2017). War trauma and maternal-fetal attachment predicting maternal mental health, infant development, and dyadic interaction in Palestinian families. Attachment & Human Development, 19(5), 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1330833

- Rahma, K. A. Prevoo, M. J., Alink, L. R., & Mesman, J. (2018). Predictors of sensitive parenting in urban slums in Makassar, Indonesia. Attachment & Human Development, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1454060

- Rao, N., Sun, J., Wong, J. M. S., Weekes, B., Ip, P., Shaeffer, S., & Lee, D. (2013). Early childhood development and cognitive deveolpment in developing countries: A rigorous literature review. Department for International Development (Report No. 2208).

- Rasheed, M. A., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2015). The development and reliability of an observational tool for assessing mother-child interactions in field studies-experience from Pakistan. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(6), 1161–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12287

- Rempel, L. A., & Rempel, J. K. (2011). The breastfeeding team: The role of involved fathers in the breastfeeding family. Journal of Human Lactation, 27(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334410390045

- Rocha, N. A. C. F., Dos Santos Silva, F. P., Dos Santos, M. M., & Dusing, S. C. (2020). Impact of mother-infant interaction on development during the first year of life: A systematic review. Journal of Child Health Care, 24(3), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493519864742

- Roggman, L. A., Cook, G. A., Innocenti, M. S., Jump Norman, V., & Christiansen, K. (2013). Parenting interactions with children: Checklist of observations linked to outcomes (PICCOLO) in Diverse Ethnic Groups. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(4), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21389

- Scherer, E., Hagaman, A., Chung, E., Rahman, A., O’Donnell, K., & Maselko, J. (2019). The relationship between responsive caregiving and child outcomes: Evidence from direct observations of mother-child dyads in Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6571-1

- Schröder, L., Kärtner, J., Keller, H., & Chaudhary, N. (2012). Sticking out and fitting in: Culture-specific predictors of 3-year-olds’ autobiographical memories during joint reminiscing. Infant Behavior and Development, 35(4), 627–634.

- Shaw, D. S., Keenan, K., & Vondra, J. I. J. (1994). Developmental precursors of externalizing behavior: Ages 1 to 3. Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.355

- Sumner, G. (1994). NCAST caregiver/parent-child interaction teaching manual. NCAST Publications.

- Tomlinson, M., Rabie, S., Skeen, S., Hunt, X., Murray, L., & Cooper, P. J. (2020). Improving mother-infant interaction during infant feeding: A randomised controlled trial in a low-income community in South Africa. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(6), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21881

- Wogene, T. W. (2012). Infant Recognition Memory and Physical Growth in Wolayita: Relations to Maternal Depression, Food Insecurity Social Support and Mother-Infant Interaction ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Oklahoma State University, US.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Nurturing care for early childhood development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514064

- Wörmann, V., Holodynski, M., Kärtner, J., & Keller, H. (2012). A cross-cultural comparison of the development of the social smile: A longitudinal study of maternal and infant imitation in 6- and 12-week-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 35(3), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.03.002

- Yousafzai, A. K., Rasheed, M. A., Rizvi, A., Armstrong, R., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2015). Parenting skills and emotional availability: An RCT. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1247–e1257. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2335

- Zevalkink, J., & Riksen-Walraven, J. M. (2001). Parenting in Indonesia: Inter- and intracultural differences in mothers’ interactions with their young children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000113

- Zevalkink, J., Riksen-Walraven, J. M., & Bradley, R. H. (2008). The quality of children’s home environment and attachment security in Indonesia. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 169(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.169.1.72-91