ABSTRACT

Background/aims

Giving birth is a life-changing experience for women. Most previous studies have focused on risk factors for a negative childbirth experience. The primary aim of this study was to assess childbirth experience in a sample of postnatal Swedish women. The secondary aim was to analyse demographic and clinical determinants associated with a positive birth experience.

Design/Methods

A digital survey including the instrument Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2 (CEQ2) was answered by 619 women six to 16 weeks postpartum. Regression analyses were made assessing the impact that different factors had on the overall childbirth experience and the four subscales of CEQ2: Own Capacity, Perceived Safety, Professional Support and Participation.

Results

Overall, women were satisified with their birthing experience. Several factors contributed to a positive childbirth experience. Having a vaginal mode of birth (without vacuum extraction) together with not having ongoing mental health problems were the factors with the most influence on the total childbirth experience. Not having maternal complications postpartum and receiving much support from a trusted birth companion were two other important factors.

Conclusion

Although Swedish women tend to express satisfaction with their childbirth experiences, there is a necessity to advocate for a childbirth approach that optimises the chance of giving birth vaginally rather than with vacuum extraction or acute caesarean section, and reduces the risk for complications whenever possible. During pregnancy, mental health problems should be appropriately addressed. Healthcare professionals could also more actively involve the birth companion in the birthing process and equip them with the necessary tools to effectively support birthing women.

Introduction

Around 140 million women give birth every year (Oladapo et al., Citation2018). Giving birth is a significant event in women’s lives, as it is an individual experience that impacts the health and mental well-being of not only the birthing woman but also the child and surrounding family. The childbirth experience carries both short-term and long-term consequences. A positive birth experience can boost the mother’s self-esteem and confidence in her new role as a parent (Karlström et al., Citation2015), and it can strengthen her attachment to the newborn (Smorti et al., Citation2020). Conversely, a negative birth experience increases the risk of postpartum depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder (Fair & Morrison, Citation2012).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided a definition for a positive childbirth experience, stating that it should fulfil or surpass a woman’s personal and sociocultural beliefs and expectations. This includes giving birth to a healthy baby in a clinically and psychologically safe environment, with continuous practical and emotional support from a birth companion and competent clinical staff. In 2018, the WHO released guidelines for intrapartum care, offering specific recommendations for care during all stages of labour to enhance the likelihood of positive childbirth experiences (Oladapo et al., Citation2018). In a recent publication, Leinweber et al. (Citation2023) provided a new and woman-centred definition of a positive childbirth experience: ‘A positive childbirth experience refers to a woman’s experience of interactions and events directly related to childbirth that made her feel supported, in control, safe, and respected; a positive childbirth can make women feel joy, confident, and/or accomplished and may have short- and/or long-term positive impacts on a woman’s psychosocial well-being’ (ibid p 364). By this definition, the authors recognise that ensuring high quality care is essential for birthing women to experience support, maintain control, feel safe, and be respected throughout labour and childbirth (Leinweber et al., Citation2023).

The caregiver’s relationship with the birthing woman significantly impacts childbirth experiences (Dahlberg & Aune, Citation2013). A competent, genuine, and emotionally supportive caregiver fosters trust, enhancing the woman’s confidence in her own birthing abilities. Acceptance, empathy, and having a holistic approach are important caregiver characteristics to properly meet the woman’s individual needs (Dahlberg & Aune, Citation2013; Downe et al., Citation2018; Hill & Firth, Citation2018; Nilsson et al., Citation2013). Effective communication, using understandable language and providing comprehensive information, is also essential for any caregiver (Henderson & Redshaw, Citation2013; Martins et al., Citation2021). Women value personal control and active involvement in decision making during labour and birth (Downe et al., Citation2018; Hill & Firth, Citation2018).

Mental health problems may be a risk factor for a negative childbirth experience. A recent study found a correlation between a negative childbirth experience and poorer mental health, including maternal functioning (Havizari et al., Citation2022). In contrast, Eitenmüller et al. (Citation2022) revealed that mothers with self-reported prior mental health problems had higher prepartum depression scores, but no significant correlation was found between mental health problems and the subjective birth experience.

Evidence on demographic risk factors and childbirth experiences is conflicting. Education level has shown both positive and negative associations, as have age under 30 and parity (Henderson & Redshaw, Citation2013; Viirman et al., Citation2022). The presence and support of the partner have been identified as positive factors in childbirth experiences in several studies (Dahlberg & Aune, Citation2013; Downe et al., Citation2018; Karlström et al., Citation2015; Nilsson et al., Citation2013). However, some studies have yielded no significant correlation (Martins et al., Citation2021; Sigurdardottir et al., Citation2017).

Up until now, research on childbirth experiences has predominantly focused on risk factors for negative experiences, while positive experiences and the factors contributing to them (i.e. salutogenic factors) have received less attention. This can be attributed to various factors. Much of the research on childbirth is medically oriented, aiming to identify and address complications, risks, and adverse outcomes. Negative experiences may be more thoroughly investigated to improve medical practices and outcomes. Furthermore, healthcare research tends to focus on identifying and mitigating risks, and negative birth experiences provide valuable insights into potential complications and areas for improvement in maternal and neonatal care. Since negative birth experiences are often associated with worse outcomes, such as maternal morbidity or neonatal mortality, they are significant public health concerns, and research in this area may be prioritised to address these critical issues and improve overall health outcomes. However, overemphasis on negative experiences has led to a limited understanding of the factors that contribute to positive birth experiences (McKelvin et al., Citation2021). Excessive focus on complications and interventions contribute to the perception that normal, uncomplicated births are the exception rather than the norm. This can lead to a medicalised view of childbirth and influence societal attitudes. The emphasis on negative outcomes may also contribute to heightened anxiety and fear among expectant mothers. A more balanced research approach that includes positive experiences could have a positive impact on maternal mental health (Luce et al., Citation2016). Therefore, it is crucial to explore salutogenic factors, as understanding them can equip caregivers with insights into why some individuals have more positive experiences and what promotes a shift towards a more positive trajectory (McKelvin et al., Citation2021). By investigating and recognising these positive aspects, healthcare providers can enhance their ability to support and facilitate positive childbirth experiences.

The primary aim of this study was to assess childbirth experience in a sample of postnatal Swedish women. The secondary aim was to analyse demographic and clinical determinants associated with a positive birth experience.

Materials and methods

Design

This is a multi-centre cross-sectional study, performed in the period September 2021-January 2022.

Data collection

A digital survey was sent to 2000 women in five cities of different sizes located in southern Sweden. After ethical approval and consent from the managers in each participating clinic, administrators provided a list of the personal code numbers of women fitting the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were being 18 years of age or older and having given birth in the previous six to 16 weeks. Women who had given birth to a stillborn baby were excluded. The list of eligible women was sent to the Swedish state personal address register to retrieve their addresses. Information about the study, along with a link and QR code to the questionnaire, was sent to each woman. Participants provided their consent by providing a unique study code assigned to them, followed by filling in the questionnaire. For those who had not responded within two weeks, a reminder with a printed version of the questionnaire and a pre-paid envelope was sent.

The questionnaire included questions on sociodemographics and clinical variables about the birth, and the Childbirth Experience Scale 2 (CEQ2). The CEQ2 consists of 22 questions about the childbirth experience, whereof 19 are answered on a four-degree Likert scale with a range of 1–4. The CEQ2 questions are divided into four subscales: ‘Own Capacity’ (eight questions), ‘Perceived Safety’ (six questions), ‘Professional Support’ (five questions) and ‘Participation’ (three questions). The final three questions of the instrument are formed as Numerc Rating Scales that are graded from zero to 100 and then coded into four intervals. A total score is calculated by adding all numbers and dividing by four. A higher score indicates a more positive childbirth experience. This instrument has been validated and has good psychometric performance in a Swedish context (Dencker et al., Citation2020).

Data analyses

Nominal data are presented as number and percentage. Continuous variables are described as mean and standard deviation. The experience of childbirth was reported by means from the total sample (n = 619). To analyse which demographic and clinical determinants were associated with a positive childbirth experience, univariate and multiple regression analyses were used. In all regression analyses, those with elective caesarean section were excluded because they were considered a selected group that differs from the remaining modes of birth when it comes to feelings of control and power. Hence, the regression analyses were made on a sub-group consisting of 577 participants.

The determinants included in regression analyses were dichotomised as follows: mode of birth (1=Vaginal birth/0=Vaginal assisted birth with vacuum extraction/acute caesarean section [elective caesarean section excluded]), maternal complications (1=No complications, 0=Yes, minor complications/Yes, major complications), infant complications (1=No complications, 0=Yes, minor complications/Yes, major complications), having a birth companion present at birth (1=Partner/Friend/Relative/Doula, 0=No birth companion), experienced support from birth companion (1=A lot/A great deal, 0=None at all/A little/A moderate amount), ongoing mental health problems (1=No, 0=Yes), living in country of birth (1=Yes, 0=No), education (1=Higher education, 0=No education/Elementary School/High school), relationship status (1=Married/Living with a partner, 0=In a relationship but not co-living/Single/Separated/Divorced/Other), given birth previously (1=Yes, 0=No) and previous traumatic birth experience (1=No, 0=Yes).

Univariate regression analyses were performed with the determinants as independent variables, with both the total CEQ2 score and the separate subscales of CEQ2 as dependent variables. The determinants that were significant in the univariate regressions were then analysed for multicollinearity by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIFs for these determinants were <5, which indicates that there was no significant multicollinearity between the variables (Kim, Citation2019). The significant determinants were later included in the multivariate regression. The significant results in these analyses were considered to have an independent influence on the childbirth experience, keeping all the other determinants constant. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0 was used for the analyses.

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority on 20 August 2021 (Dnr 2021–03968).

Results

Out of 2000 invited women, 619 (31%) participated in the study. The characteristics of the women are shown in .

Table 1. Demographic data and clinical factors.

The mean age was 32.8 years (range 18–47). The majority were primiparous (n = 336; 54%), were married or living with a partner (n = 599; 97%) and had attended higher education (n = 494; 80%). Sixty-seven women (11%) indicated that they had ongoing mental health problems, whereas 48 (8%) reported that they were currently receiving professional support or treatment for mental health problems at the time they filled out the questionnaire. Most women had a vaginal birth without vacuum extraction (n = 458; 74%). Almost everyone had a birth companion present during the birth (n = 612; 99%), and most women (n = 539; 88%) had experienced much support from this person.

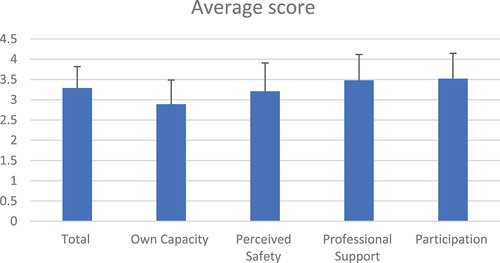

The score on the total CEQ2 scale ranged between 1.30 and 4.00. The mean average was 3.29 ± 0.53. The scoring on subscales ranged between 1.00 and 4.00. The mean average scores were 2.89 ± 0.60 for ‘Own Capacity’, 3.21 ± 0.70 for ‘Perceived Safety’, 3.48 ± 0.64 for ‘Professional Support’ and 3.52 ± 0.63 for ‘Participation’ ().

Figure 1. The mean average score and standard deviation for the total childbirth experience score, and the scoring on the childbirth experience subscales among the total study participants (n = 619).

In the univariate regression analysis between each determinant, CEQ2 total and CEQ2 subscales, several determinants were significantly associated with a positive birthing experience ().

Table 2. Regression coefficients (β) and p-values for the univariate regression analysis between each determinant, the total childbirth experience score, and the scoring on the childbirth experience subscales.

shows the results of multiple regression analyses, illustrating the significant and independent influence of each determinant on CEQ2, which pertains to the childbirth experience.

Table 3. Regression coefficients (β) and p-values for the multivariate regression analysis between each significant determinant in the univariate analysis, the total childbirth experience score, and the scoring on the childbirth experience subscales.

Several determinants were found to make a significant contribution to a positive childbirth experience. The factors that were most influential on the overall childbirth experience were having a vaginal birth without vacuum extraction and not having mental health problems. Furthermore, the absence of postpartum maternal complications and experiencing a high level of support from a birth companion significantly influenced the childbirth experience.

The determinant that had the strongest influence on the subscale ‘Own Capacity’ was having a vaginal birth without vacuum extraction. Following that, not having mental health problems played a significant role, followed by having given birth previously, and receiving a high level of support from the birth companion. Furthermore, the absence of maternal complications and not having a previous traumatic childbirth experience were significant determinants for ‘Own Capacity’. The subscale ‘Perceived Safety’ was strongly associated with having a vaginal birth without vacuum extraction, followed by the absence of maternal complications, and receiving a high level of support from the birth companion. Having a birth companion providing a high level of support provided the largest contribution to the subscale ‘Professional Support’. Additionally, having a vaginal childbirth without vacuum extraction and the absence of mental health issues and maternal complications were found to have a significant influence on the subscale of ‘Professional Support’. In the subscale ‘Participation’, determinants such as vaginal birth without vacuum extraction, absence of maternal complications, no ongoing mental health problems and receiving a high level of support from a birth companion were found to contribute significantly to the experience of participation.

Discussion

The participants in this study rated their childbirth experience relatively highly compared to previous studies utilising the CEQ2. A Finish study reported mean total scores of 3.0 (Place et al., Citation2022) and a Portuguese study had a mean total score of 2.9 (Marques et al., Citation2022), in comparison with our mean total score of 3.3. The CEQ2 instrument is relatively new, which limits the availability of studies for direct comparison with the present study in terms of CEQ2 scores.

The study findings indicate that several determinants have a significantly positive influence on the childbirth experience. These factors include having a vaginal birth without vacuum extraction together with the absence of maternal complications during pregnancy or childbirth, experiencing a high level of support from a birth companion, having prior childbirth experiences and no ongoing mental health problems.

The mode of birth was identified as one of the primary factors influencing the overall birth experience, where a nonoperative vaginal birth compared with vaginal assisted birth with vacuum extraction or acute caesarean section, made a significant contribution to positive experiences. Promoting a childbirth with as few interventions as possible is crucial to enhance the salutogenesis of the experience. However, while childbirth is a physiological process, many women receive excessive medical interventions in various healthcare settings. Most interventions are medically motivated at an ‘intention to treat-level’, but they also carry risks at the individual level such as undermining a woman’s ‘natural’ ability to give birth and having a negative impact on her childbirth experience (Oladapo et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, this issue is multifaceted, as interventions are mostly employed to prevent prolonged labour, potentially reducing the likelihood of complications and consequently enhancing the childbirth experience (Jansen et al., Citation2013). Additionally, it is crucial to keep in mind that having what healthcare institutions classify as a ”normal” and uncomplicated birth does not automatically ensure a positive childbirth experience (Oladapo et al., Citation2018).

Previous studies have yielded conflicting evidence regarding whether the presence and support of a birth companion have a positive influence on the childbirth experience (Dahlberg & Aune, Citation2013; Downe et al., Citation2018; Karlström et al., Citation2015; Martins et al., Citation2021; Sigurdardottir et al., Citation2017). In this study, the results did not show a significant correlation between the presence of a birth companion and a positive childbirth experience. However, it is noteworthy that in this study sample, there were very few women who had no birth companion present, which could explain the lack of a statistically significant impact of the determinant. However, receiving a lot or a great deal of support from the birth companion was a significant determinant for a positive experience. This may suggest that the support from the birth companion could be crucial for the birthing experience, and only having a birth companion present during childbirth may not ensure a positive experience. Healthcare professionals should pa9y more attention to this aspect as it contributes to the salutogenesis of the childbirth experience. By involving partners, or any other person present at birth, in every stage of childbirth and enhancing their role in supporting the mother, the childbirth experience can be improved (Dahlberg & Aune, Citation2013; Karlström et al., Citation2015). The significance of including partners has been recognised as an important aspect of midwifery care (Grundström et al., Citation2022). Midwives can engage birth companions by maintaining open communication, involving them in decision-making, and recognising their emotional and physical support roles (Tokhi et al., Citation2018).

Having no ongoing mental health problem was a significant determinant for the total scale and most subscales. However, the questionnaire used in this study did not specify which particular type of mental health problem the women had, nor did it inquire about the timing of its onset – whether it existed prior to childbirth or emerged afterwards. Consequently, this limits the interpretation of the significance of the results regarding mental health. In a prior study, a correlation was found between a positive childbirth experience, good mental health, and maternal functioning (Havizari et al., Citation2022). Similarly, in the present study, it was observed that the absence of mental health problems contributes to salutogenesis and has a positive influence on the childbirth experience. It would be reasonable to think that mental health problems increase the risk for a negative interpretation of the birthing experience, but McKelvin et al. (Citation2021) found contradictory results in their literature review, mostly due to different sample sizes, retention rates, and measurement tools. The association between mental health problems and the childbirth experience needs to be further explored both from a pathogenic and salutogenic perspective (McKelvin et al., Citation2021).

Some interesting results were found in the subscale ‘Own capacity’ that warrant commenting. Multiparity and not having previous traumatic birth experience were both significant determinants for a positive birth experience. The association between multiparity and a positive birth experience aligns with existing literature, suggesting that individuals who have undergone multiple childbirths may exhibit increased confidence and a better understanding of the birthing process (Henderson & Redshaw, Citation2013; Hochman et al., Citation2023). This familiarity with childbirth could contribute to a more positive perception of their own capacity to navigate the experience successfully. The more positive experiences among parous women might also be attributed to primiparous women more often having extended duration of labour, heightened requirement for intrapartum interventions (SCB, Citation2023), and misconceptions about the birthing experience (Abalos et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the absence of a previous traumatic birth experience being linked to a positive birth experience underscores the lasting impact of past birthing encounters on subsequent experiences. It suggests that women without a history of traumatic birth may approach the current childbirth with less anxiety or apprehension, potentially contributing to a more positive overall experience. These findings hold implications for healthcare providers and policymakers in tailoring support and interventions for pregnant women. Acknowledging the influence of multiparity and the absence of traumatic experiences can help in identifying those who may benefit from targeted interventions, such as counselling or additional support, to enhance their overall birthing experience. However, the evidence regarding predictor variables representing a vulnerability for a negative birth, development of posttraumatic stress symptoms or promote a positive birth has been reported as contradictory (McKelvin et al., Citation2021).

The participants in this study were selected from various cities and hospitals of varying sizes, which enhances the generalisability of the findings. The participants’ mean age, parity, and distribution of mode of birth were comparable to the national average. However, it is worth noting that the percentage of participants born outside Sweden was lower in this study (13%) compared to the general population (20%) (SCB, Citation2023). Additionally, the proportion of individuals with a university education was significantly higher in this study (80%) compared to the national gender and age-matched average (52%) (SCB, Citation2023). The questionnaire used in this study achieved a response rate of 31%, which is lower than the desired rate. Nonetheless, a considerable number of individuals responded to the questionnaire, which enhances the validity of the results. Finally, 38% of women who had given birth before reported a previous traumatic birth experience. This number is in line with previous research (Ayers et al., Citation2009) but it may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Swedish women rate their childbirth experience relatively high. To optimise the chance of a positive childbirth experience, the factors directly related to the birthing process should be targeted. There is a need to focus on facilitating physiological childbirth with minimal interventions where appropriate. Further, healthcare professionals should more actively involve the birth companion in the birthing process and equip them with the necessary tools to effectively support birthing women. Finally, mental health problems must be properly addressed during pregnancy to optimise a good mental health when going into childbirth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is not available due to ethical reasons.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abalos, E., Oladapo, O. T., Chamillard, M., Díaz, V., Pasquale, J., Bonet, M., Souza, J. P., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2018, April). Duration of spontaneous labour in ‘low-risk’ women with ‘normal’ perinatal outcomes: A systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 223, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.02.026

- Ayers, S., Harris, R., Sawyer, A., Parfitt, Y., & Ford, E. (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: Analysis of symptom presentation and sampling. Journal of Affective Disorders, 119(1), 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.029

- Dahlberg, U., & Aune, I. (2013). The woman’s birth experience-the effect of interpersonal relationships and continuity of care. Midwifery, 29(4), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.09.006

- Dencker, A., Bergqvist, L., Berg, M., Greenbrook, J. T. V., Nilsson, C., & Lundgren, I. (2020). Measuring women’s experiences of decision-making and aspects of midwifery support: A confirmatory factor analysis of the revised childbirth experience questionnaire. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02869-0

- Downe, S., Finlayson, K., Oladapo, O., Bonet, M., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Norhayati, M. N. (2018). What matters to women during childbirth: A systematic qualitative review. Public Library of Science One, 13(4), e0194906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194906

- Eitenmüller, P., Köhler, S., Hirsch, O., & Christiansen, H. (2022). The impact of prepartum depression and birth experience on postpartum mother-infant bonding: A longitudinal path analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 30(13), 815822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815822

- Fair, C., & Morrison, T. (2012). The relationship between prenatal control, expectations, experienced control, and birth satisfaction among primiparous women. Midwifery, 28(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.10.013

- Grundström, H., Malmquist, A., Nieminen, K., & Alehagen, S. (2022). Supporting women’s reproductive capabilities in the context of childbirth: Empirical validation of a midwifery theory synthesis. Midwifery, 110, 103320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103320

- Havizari, S., Ghanbari-Homaie, S., Ommlbanin, E., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2022). Childbirth experience, maternal functioning and mental health: How are they related? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 40(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2021.1913488

- Henderson, J., & Redshaw, M. (2013). Who is well after childbirth? Factors related to positive outcome. Birth, 40(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12022

- Hill, E., & Firth, A. (2018). Positive birth experiences: A systematic review of the lived experience from a birthing person’s perspective. Midwifery Digest, 28(1), 71–78.

- Hochman, N., Galper, A., Stanger, V., Levin, G., Herzog, K., Cahan, T., Bookstein Peretz, S., & Meyer, R. (2023, December). Risk factors for a negative birth experience using the birth satisfaction scale-revised. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 163(3), 904–910. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14884

- Jansen, L., Gibson, M., Bowles, B., & Leach, J. (2013). First do no harm: Interventions during childbirth. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 2(22), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.22.2.83

- Karlström, A., Nystedt, A., & Hildingsson, I. (2015). The meaning of a very positive birth experience: Focus groups discussions with women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0683-0

- Kim, J. H. (2019). Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 72(6), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087

- Leinweber, J., Fontein-Kuipers, Y., Karlsdottir, S. I., Ekström-Bergström, A., Nilsson, C., Stramrood, C., & Thomson, G. (2023). Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of positive childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth, 50(2), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12666

- Luce, A., Cash, M., Huntley, V., Cheyne, H., van Teijlingen, E., & Angell, C. (2016). “Is it realistic?” the portrayal of pregnancy and childbirth in the media. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0827-x

- Marques, M., Zangão, O., Miranda, L., & Sim-Sim, M. (2022). Childbirth experience questionnaire: Cross-cultural validation and psychometric evaluation for European Portuguese. Women’s Health (London, England), 18, 17455057221128121. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057221128121

- Martins, A., Giugliani, E., Nunes, L., Bizon, A., Kroll de Senna, A., Paiz, J., Castro de Avilla, J., & Giugliani, C. (2021). Factors associated with a positive childbirth experience in Brazilian women: A cross-sectional study. Women & Birth, 34(4), e337–e345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.003

- McKelvin, G., Thomson, G., & Downe, S. (2021). The childbirth experience: A systematic review of predictors and outcomes. Women & Birth, 34(5), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.021

- Nilsson, L., Thorsell, T., Hertfelt Wahn, E., & Ekström, A. (2013). Factors influencing positive birth experiences of first-time mothers. Nursing Research and Practice, 2013, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/349124

- Oladapo, O., Tunçalp, Ö., Bonet, M., Lawrie, T., Portela, A., Downe, S., & Gülmezoglu, A. (2018). WHO model of intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: Transforming care of women and babies for improved health and wellbeing. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(8), 918–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15237

- Place, K., Rahkonen, L., Verho-Reischl, N., Adler, K., Heinonen, S., Kruit, H., & Ngene, N. C. (2022). Childbirth experience in induced labor: A prospective study using a validated Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) with a focus on the first birth. Public Library of Science One, 17(10), e0274949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274949

- Sigurdardottir, V., Gamble, J., Gudmundsdottir, B., Kristjansdottir, H., Sveinsdottir, H., & Gottfredsdottir, H. (2017). The predictive role of support in the birth experience: A longitudinal cohort study. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 30(6), 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.04.003

- Smorti, M., Ponti, L., Ghinassi, S., & Rapisardi, G. (2020). The mother-child attachment bond before and after birth: The role of maternal perception of traumatic childbirth. Early Human Development, 142, 104956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.104956

- Statistiska Centralbyrån. (2023). Statistikdatabasen. https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/

- Tokhi, M., Comrie-Thomson, L., Davis, J., Portela, A., Chersich, M., Luchters, S., & van Wouwe, J. P. (2018 Jan 25). Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. Public Library of Science One, 13(1), e0191620. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191620

- Viirman, F., Hesselman, S., Wikström, A., Skoog Svanberg, A., Skalkidou, A., Sundström Poromaa, I., & Wikman, A. (2022). Negative childbirth experience – what matters most? a register-based study of risk factors in three time periods during pregnancy. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 34, 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2022.100779