Abstract

This study examines the extent to which a company's fair trade reputation, and the fit between this reputation and the company's communicated fair trade message, influences consumer scepticism and positive electronic word-of-mouth. The results of two experiments show that a previous fair trade reputation has a direct and indirect effect, via consumer brand identification, on consumer scepticism. Moreover, the fit between the reputation and the communicated message seems to affect scepticism only when the communicated message is perceived as realistic. In industries with poor fair trade reputations (Study 1), the fit does not seem to have an effect on scepticism, while the fit influences scepticism in industries with a certain reputation history for fair trade (Study 2). Scepticism and consumer brand identification play an important mediating role in the relation among reputation, fit and consumers' electronic word-of-mouth intentions. Therefore, we conclude that communicating fair trade initiatives not only can be a rewarding effort but also seems to be a delicate matter.

Introduction

In recent decades, the literature on fair trade consumption has increased enormously (Andorfer and Liebe Citation2012; Castaldo et al. Citation2009; De Pelsmacker, Driesen, and Rayp Citation2005; Herédia-Colaço, do Vale, and Villas-Boas Citation2019). Consumers have become much more aware of the ethical consequences of their behaviour (Carrington, Neville, and Whitwell Citation2010; White, MacDonnell, and Ellard Citation2012), and although market shares of fair trade products, in general, are small, they are growing rapidly. For example, global retail sales of fair trade-certified products more than doubled between 2008 and 2015, reaching €7.3 billion (Fairtrade International 2017), and fair trade sales in the U.S. grew 33% in 2015.

Although these figures look promising, consumers' scepticism about firms that offer sustainable products is growing (Leonidou and Skarmeas Citation2017). For instance, a 2013 European Commission study reported that consumers may react cynically to sustainability initiatives, when they are perceived as being inconsistent with a company's other policies.

Moreover, a recent GfK research report in Germany found that 76% of the respondents had at least ambivalent thoughts about fair trade labels in a clothing context (Frank et al. Citation2016). In addition, disasters, such as the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, may lead to negative consumer attitudes towards the clothing industry’s working conditions in developing countries. Thus, consumers are increasingly aware of fair trade initiatives, but also seem to be sceptical about these initiatives. Consumers' perceptions of a company's reputation might play an important role in explaining this scepticism.

Only a few studies focused on the impact of a company's reputation on consumers' evaluations of fair trade initiatives (Castaldo et al. Citation2009; Obermiller et al. Citation2009). Obermiller et al. (Citation2009) investigated the effect of a general brand reputation on attitudes towards a fair trade advertisement. Castaldo et al. (Citation2009) found a positive effect of a corporate social responsibility (CSR) reputation on consumers' trust in specific fair trade products.

Although literature often includes fair trade as a dimension of CSR (Inoue and Lee, Citation2011; Maloni and Brown, Citation2006; Öberseder et al., Citation2014; Pérez and Del Bosque Citation2013), one might expect a similar role for a company's fair trade reputation in consumers' evaluations of fair trade initiatives. However, none of the previous studies specifically examined this role of a company's fair trade reputation. Moreover, to our knowledge, no research focused on scepticism as a consequence of a previous fair trade reputation. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature, as we focus on (1) the role of a pre-existing fair trade reputation, instead of a general reputation, and (2) an important negative outcome for companies, namely, consumers' scepticism about a fair trade brand.

Castaldo et al. (Citation2009) reasoned that companies with a high reputation for building positive relationships with society are eager to maintain this reputation. Therefore, consumers might think that these companies are more likely to act in line with their promises. To the best of our knowledge, no research in the fair trade context has investigated these assumptions. Given the rise of consumer scepticism about companies’ sustainability initiatives and the negative consequences of this scepticism for companies (Leonidou and Skarmeas Citation2017), we investigate how consumers respond to a fair trade message about a company that does not fit (or fits) this company's previous fair trade reputation. According to Fombrun and Shanley (Citation1990), consumers can use perceptions of an organization’s reputation as cues with which to assess conflicting information about the company or organization. Therefore, consumers' responses to fair trade communication seem to be intertwined with a company's previous fair trade reputation.

In sum, this study aimed to investigate the role of a pre-existing fair trade reputation and the fit between this reputation and the communicated fair trade message in consumer evaluations of a company's brand. More specifically, in two experiments, we tested the effects of a company's fair trade reputation, as well as a (mis)fit in a communicated fair trade message by a third party, on consumer scepticism. We focus on fair trade communication about a brand by a third party to rule out consumers' perceptions of a company's self-interest, because previous studies have argued that, in general, non-corporate information sources are perceived as less biased than corporate sources (Du and Vieira Citation2012; Yoon et al. Citation2006). We further investigated the possible mediating role of consumer-brand identification in this relationship, as previous research has shown that consumer identification can play a crucial role in the effect of a company's CSR reputation on supportive and advocacy behaviours towards the company (Sen and Bhattacharya Citation2001).

Because consumer scepticism about a company's motives for CSR initiatives could result in a diminished intention to speak positively (Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013), or even to speak negatively about a brand (Leonidou and Skarmeas Citation2017), in Study 2, we focused on consumers' word-of-mouth intentions as behavioural outcome. Brands that implement socially responsible initiatives may count on consumers who will speak favourably about the brands to others (Stanaland et al. Citation2011). Recently, this consumer advocacy for brands has moved from an offline to an online environment (Eisingerich et al. Citation2015). This electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) can be defined as ‘any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual, or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet’ (Hennig-Thurau et al. Citation2004, 39). To date, no studies in the fair trade context have focused on eWOM. In the CSR context, Stanton et al. (Citation2019) used eWOM as an independent variable to predict attitudes towards a company, while Vo et al. (Citation2017) focused on the relation between CSR engagement and consumers' positive and negative responses on Twitter. Because eWOM has been proven to be an important influencer of consumers' decision making regarding companies and brands (Jin and Phua Citation2014; Laczniak et al. Citation2001; Rim and Song Citation2016), this study included eWOM intentions as a behavioural response to fair trade reputation and fit. In the next section, we elucidate the conceptual framework of this study.

Conceptual framework

Consumer scepticism

Consumer scepticism can be defined as a distrust or disbelief regarding advertising claims or public relations efforts (Forehand and Grier Citation2003; Obermiller and Spangenberg Citation1998). Consumers can use scepticism as a defence mechanism to protect themselves from possibly misleading marketing communications (Kim and Lee Citation2009). Sceptical consumers are unwilling to trust companies and their activities. Webb and Mohr (Citation1998) found that higher levels of scepticism lead to negative attitudes towards socially responsible campaigns. A vast number of studies have investigated the effects of consumer scepticism. These studies found that the more sceptical consumers are, the less positive their attitudes, brand evaluations, and word-of-mouth intentions and the lower the consumers' purchase intentions (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, and Hill Citation2006; de Vries et al. Citation2015; Leonidou and Skarmeas Citation2017; Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013; Yoon, Gürhan-Canli, and Schwarz Citation2006).

According to Forehand and Grier (Citation2003), there are two types of consumer scepticism: dispositional scepticism and situational scepticism. Dispositional scepticism is defined as a personality trait or a general tendency to doubt companies’ motives (Kim and Lee Citation2009). Situational scepticism, however, can be seen as a temporary state. Certain aspects of a marketing message can influence the level of one’s scepticism. Under these conditions, one can argue that situational scepticism can be evoked independently of consumers' personality traits (Forehand and Grier Citation2003). As this study aimed to investigate the role of a company's previous fair trade reputation, and the fit between this reputation and the communicated fair trade message in consumer evaluations, in the remainder of this article, we focus on consumers' situational scepticism.

Reputation and scepticism

The reputation of a company can be defined as the result of all perceptions that individuals have of the company over time (Cornelissen Citation2017). Likewise, a company's fair trade reputation represents consumers' perceptions of a company's fair trade activities. Since the fair trade concept was developed, it has become increasingly integrated in CSR (Mohan Citation2009). Carrol (Citation1991) previously introduced the ethical dimension in his pyramid of CSR as the ‘[o]bligation to do what is right, just and fair’ (Carroll 1991, 42). As a result, a vast number of studies in the consumer context have integrated fair trade as one of the dimensions of CSR (Öberseder et al. Citation2014).

Several studies on CSR reputation showed that consumers have unfavourable attitudes about the CSR activities of companies with bad reputations. For example, Obermiller et al. (Citation2009) found that when a well-known brand incorporates fair trade initiatives in its advertisements, this action leads to positive attitudes towards the brand than when an unknown brand incorporates fair trade initiatives. Bögel (Citation2016) showed that when a company has a negative reputation, consumers are less likely to trust the company's CSR activities. More specifically, Vanhamme and Grobben (Citation2009) found that companies that have built a longer CSR history, and thus, obtained a better CSR reputation, face less consumer scepticism than companies that only recently started CSR activities. These findings indicate that a company's previous CSR reputation influences consumer attitudes towards the company. In one of the few studies in the fair trade context, Castaldo et al. (Citation2009) argued that consumers make decisions based on companies’ fair trade positioning. The authors showed that if consumers believe a company is committed to its social and ethical initiatives, then consumers' trust in the company's fair trade products increases.

Based on these studies that related reputation to consumers' attitudes towards a company's CSR or fair trade initiatives, we expect that when a third party communicates about a brand with a high fair trade reputation, this communication will lead to less scepticism about the brand’s fair trade initiatives compared to when a third party communicates about a brand with a low fair trade reputation. We hypothesized the following:

H1: Fair trade communication about a brand with a high fair trade reputation leads to less scepticism than fair trade communication about a brand with a low fair trade reputation.

Fit and scepticism

In addition to the main effect of fair trade reputation, we expect that if this reputation is in line with the communicated fair trade message, consumers will experience less scepticism. This proposed effect can be explained by Osgood and Tannenbaum’s (Citation1955) principle of congruity. According to Osgood and Tannenbaum (Citation1955, 43), ‘changes in evaluation are always in the direction of increased congruity with the existing frame of reference’. In line with this definition, consumers prefer continuity in what they know or perceive about a product or a brand, and new information communicated about this brand.

To further elaborate on this assumption, we draw from associative network models, which imply that human memory is a network of interconnected nodes that activate each other in specific contexts (Hinton and Anderson Citation2014). According to Becker-Olsen et al. (Citation2006), a good fit between a consumer’s previous associations with a company and a company's current activities can be more easily integrated into the consumer’s existing cognitive structure. Conversely, when a certain initiative does not fit consumers' expectations for a company, it is less likely that consumers automatically incorporate this new information into their memory (Becker-Olsen et al. (Citation2006).

In the marketing context, we can draw from several streams of literature that have proven this fit leads to positive evaluations of companies or brands. First, literature on brand extensions showed that the fit between the parent brand and a new extension product is an important predictor of the success of the new product (Aaker and Keller Citation1990; Bottomley and Holden Citation2001; Völckner and Sattler Citation2006). Second, studies on cause-related marketing (CRM) provided evidence that the fit between a company and a cause leads to positive consumer evaluations (Gupta and Pirsch Citation2006; Polonsky and Speed Citation2001; Pracejus and Olsen Citation2004). For example, Nan and Heo (Citation2007) found that a CRM message with a high fit between the brand and the cause leads to positive attitudes towards the advertisement and towards the brand. Elving (Citation2013) tested the interaction effect of cause-company fit and reputation on scepticism, and found that consumers have the lowest levels of scepticism when a company has a good reputation, and a good fit between the company and the cause. Finally, in the CSR context, Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (Citation2007) showed that consumers' responses to CSR activities are dependent on the extent to which these CSR activities are consistent with the positioning of the brand or company. The authors found that when a brand had clearer CSR positioning, consumers' attributions of the company's motives for its CSR activities are less negative.

In sum, based on the principle of congruity and the associative network model approach, previous studies in several domains have found positive effects of fit on consumer evaluations of a brand. The fit between a communicated fair trade message and a company's fair trade reputation could have similar effects on consumer evaluations. For example, if consumers read a message about the new fair trade initiative of a brand with a strong fair trade reputation, such as Ben & Jerry’s, this message could be perceived as more congruent with consumers' previous thoughts about the social responsibility of the brand than when consumers read a message about the new initiative of an oil company, such as ExxonMobil. In this study, we expected that the fit between a company's previous fair trade reputation and the company's communicated fair trade message diminishes consumer scepticism. Therefore, we proposed the following:

H2: A high fit between the communicated fair trade message and the company's fair trade reputation leads to less scepticism than a low fit between the communicated fair trade message and the company's fair trade reputation.

Mediating role of consumer-brand identification

Consumer identities can play an important role in consumer responses to brands (Reinders and Bartels Citation2017; Tian, Bearden, and Hunter Citation2001). Social identity theory is often used to explain the relation between consumer identities and these brands (Escalas and Bettman Citation2003; Stokburger-Sauer, Ratneshwar, and Sen Citation2012). Social identity can be defined as ‘the individual’s knowledge that he (or she) belongs to certain groups together with some emotional and value significance to him (or her) of the group membership’ (Tajfel Citation1972, 31). Bhattacharya and Sen (Citation2003) were among the first to introduce social identity into the consumer context, and suggested that consumers can identify with certain organizations to fulfil the consumers' self-definitional needs. In turn, Ahearne, Bhattacharya, and Gruen (Citation2005) found that consumers' identification with a company leads to buying behaviour and positive word-of-mouth. More specifically, Bagozzi and Dholakia (Citation2006) found that social identification can play an important role in brand communities. Researchers have found that consumers' identification with a brand can, for example, lead to stronger brand loyalty (Lam et al. Citation2010) and more positive word-of-mouth (Alberta, Merunkaa, and Valette-Florence 2013). Thus, brand identification is an important antecedent for brand-related behaviours.

Several studies have linked an organization’s reputation to social identification. Sen and Bhattacharya (Citation2001) found that consumers are more likely to identify with companies that have good CSR reputations than with companies that have bad reputations. More specifically, the authors found that customer-company identification mediates the effect of the company's CSR reputation on company evaluations. Hong and Yang (Citation2009) also found benefits from a strong reputation regarding engendered customer-company identification. In their study, customer-company identification mediated the relation between reputation and positive word-of-mouth intentions. Recently, He, Li, and Harris (Citation2012) focused on the role of brand identity in consumer loyalty. They argued that reputation is part of brand identity, and found that brand identification mediates the relation between brand identity and brand trust. Because scepticism is closely related to trust (Obermiller and Spangenberg Citation1998), we assume that consumers' identification with a brand can also play a mediating role in the relation between a company's fair trade reputation and consumers' scepticism. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H3a: Fair trade reputation has an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification.

Several studies also indicated a mediating role of brand identification between fit and consumers' responses to a brand (Cha, Yi, and Bagozzi Citation2016; Li, Liu, and Huan Citation2019; Lii and Lee Citation2012). Although Lii and Lee (Citation2012) did not directly investigate the mediating role of customer-company identification, their model implies that when different CSR initiatives fit the reputation of the company, this fit leads to different levels of identification. The authors also found that stronger customer-company identification leads to positive in-role and extra-role behaviours. Moreover, Cha, Yi, and Bagozzi (Citation2016) showed that CSR-brand fit strengthens brand identification, which, in turn, increases brand loyalty. Finally, Li, Liu, and Huan (Citation2019) found that when a company introduces a new corporate social responsibility strategy, it leads to more customer-company identification only when the reputation of the company is high (ie when there is a fit between the company and the new corporate social responsibility strategy). Based on these findings, we also expect a mediating role for brand identification between fit and scepticism. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H3b: Fit has an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification.

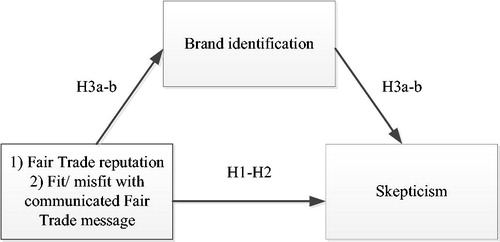

presents the conceptual model of hypotheses 1 through 3.

To test the hypotheses, we conducted two experimental studies. In both studies, 2 × 2 between-subject experimental designs were employed, including the following manipulations: communicated fair trade message (30% fair trade or 100% fair trade) and fair trade reputation (high versus low). By offering small percentages of fair trade ingredients in products, companies can bring suspicion on themselves, which would negatively influence brand purchase intention (Montoro Rios et al. Citation2006). Most of the studies in the fair trade context compared only consumer evaluations of products presented as being 100% fair trade and consumer evaluations of products that are not fair trade at all (De Pelsmacker et al. Citation2005; Didier and Lucie Citation2008; Vanhamme and Grobben Citation2009). In the clothing context, Dickson (Citation2001), for example, examined consumers' willingness to pay for clothing that either was labelled ‘No Sweat’ (ie produced under fair circumstances) or had no label at all (ie regular brand), and found that consumers were positively influenced by a No Sweat label. However, to date, researchers have not investigated how consumers respond to messages in which a company is presented as partly fair trade, and how this presentation is related to the company's perceived fair trade reputation. In the present study, we expected a high fair trade reputation with a 30% fair trade message to present a low fit, and a 100% fair trade message to present a high fit. Conversely, a low fair trade reputation with a 100% fair trade message would present a low fit, while a low fair trade reputation with a 30% fair trade message would present a high fit. Although the percentage of 30% was chosen somewhat arbitrarily, in the fair trade context, certification organizations (ie Rainforest Alliance) use this percentage as their minimum criterion for carrying the label. shows the four conditions in both experiments.

Table 1. Fair trade reputation versus communicated fair trade message.

Study 1 method

Context

In Study 1, we used apparel brands. Recently, the apparel industry has faced many issues related to low contract prices and labour exploitation (Ma, Lee, and Goerlitz Citation2016). Therefore, fashion brands have received negative publicity (Goworek et al. Citation2012). The clothing sector responded to this negative publicity with the introduction of prosocial initiatives, such as fair trade production. For example, clothing brands, such as Nike, H&M, and Zara, began prosocial initiatives (Kozlowski, Bardecki, and Searcy Citation2012). Moreover, Government legislation, such as the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, forced manufacturers and retailers to behave more ethically (Ma et al. Citation2016). These developments make it worthwhile to investigate consumers' fair trade perceptions of the apparel industry.

Pre-test Study 1

Study 1 included two clothing brands that were perceived as either high or low in fair trade. Therefore, a pre-test was conducted to determine which clothing brand was perceived as being the most fair trade and which brand was the least, to be able to represent a 100% versus a 30% fair trade brand. A within-subject design was used that included six clothing brands: H&M, Zara, Primark, Kuyichi, TOMS, and Nudie Jeans. A total of 29 Dutch respondents were asked whether they were familiar with the six brands, and to what extent they perceived the brand as being fair trade (ie having a fair trade reputation). Only respondents who indicated that they were familiar with the brand were included when the fair trade reputation was measured. To measure fair trade reputation, we used a three-item scale following Hsu (Citation2012). We used only three of the five original items, because two items have the same meaning when they are translated into Dutch. The three items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale. For example, participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with the following statement: ‘Brand X is a well-respected brand considering its fair trade products’ (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

We conducted paired sample t tests to choose the brand with the strongest fair trade associations and the brand with the weakest fair trade associations. Kuyichi and TOMS had the strongest reputations concerning fair trade (MKuyichi=4.81; SD = 1.16 and MTOMS=4.76; SD = 1.43). A dependent t-test showed that the difference between these two brands was not statistically significant (t(1, 10)= −.393, p=.70). Because more participants were familiar with the TOMS brand than with Kuyichi, we selected TOMS as the fair trade brand to include in the main study. We selected Primark as the low fair trade reputation brand, as this brand clearly had the weakest fair trade reputation (M = 1.60; SD = 1.10).

Main study

The data were collected with convenience sampling. The sample consisted of 198 Dutch participants; 152 of the participants were female, and 46 were male, with a mean age of 29.3 years (SD = 11.67). Participants from the pre-test were not invited to participate in the main study.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following four conditions, which Fairtrade Netherlands communicates: (1) TOMS is 100% fair trade, (2) TOMS is 30% fair trade, (3) Primark is 100% fair trade and (4) Primark is 30% fair trade. Due to the exclusion of participants based on their non-familiarity with the assigned brand, the final numbers of participants for the conditions were not equal. Specifically, for TOMS (N = 70), the 30% condition consisted of 31 participants, and the 100% condition consisted of 39 participants. Moreover, for Primark (N = 128), 68 participants for the 30% condition completed the survey, and 60 full responses were included for the 100% condition. Because the conditions were divided unevenly, we used Levene’s test to assess homogeneity of variance (ie the variance was equal across groups).

Participants were first exposed to a Facebook page for Fairtrade Netherlands containing a message presenting a brand (TOMS or Primark) and the percentage of the brand that was fair trade (30% or 100%). Subsequently, the participants were asked to complete a self-administered survey containing the following measures.

Measures

First, for the manipulation check on fair trade reputation, the same Hsu (Citation2012) scale was used as in the pre-test (Cronbach’s α was .95 for TOMS and .92 for Primark).

Situational scepticism was measured with an adapted version of Obermiller and Spangenberg’s (Citation1998) advertising scepticism scale. We used three items on a 7-point Likert scale anchored by totally disagree and totally agree. A sample item included ‘I am sceptical about the fair trade production of TOMS/Primark’. The reliability of the scale was adequate for TOMS and Primark (Cronbach’s α was .83 and .69, respectively). Consumer-brand identification was measured with Leach et al.’s (Citation2008) three-item 7-point Likert scale. The reliability of this scale was good (Cronbach’s α was .94 for TOMS and .92 for Primark). Additionally, we incorporated the credibility of the message and the credibility of the source as control variables in the study. For the credibility of the message and the credibility of the source, we used a two-item 7-point Likert scales: ‘The Facebook message that I just read is reliable’ (Cronbach’s α was .82 for TOMS and .84 for Primark), and ‘Fairtrade Netherlands is a reliable source’ (Cronbach’s α was .90 for TOMS and .85 for Primark). We used confirmatory factor analysis to test whether the two dimensions of credibility were perceived as being distinct. The two-dimensional model in which both dimensions were correlated (r=.67) showed a much better fit (χ2/df=.53; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA=.00) than the one-dimensional model (χ2/df = 39.11; CFI=.81; TLI=.43; RMSEA=.44). Finally, we included demographic variables (ie age, gender, income and education) as descriptive variables in the analyses. Multi-item scales were averaged across their scale items to create composite construct scores.

Study 1 results

Manipulation check and control variables

First, the manipulation check showed that participants in the TOMS condition provided statistically significantly higher scores for fair trade reputation (M = 5.23, SD = 1.16) than participants in the Primark condition (M = 1.57, SD = 95; t(1, 196)=22.60, p<.01). Additionally, Fairtrade Netherlands was perceived as a credible source (M = 4.83, SD = 1.23). An ANOVA showed that the difference between the conditions was not statistically significant (F(3, 194)=.54, p=.72). Finally, participants perceived the Facebook message to be credible (M = 4.03, SD = 1.39). However, an ANOVA showed that the differences between the conditions were statistically significant (F(3, 194)=12.29, p<.01). A post hoc analysis showed that the Primark 100% fair trade condition was perceived as the least reliable (M = 3.23, SD = 1.52), whereas the other three conditions did not differ statistically significantly.

Hypotheses testing

First, to test the main effect of a company's fair trade reputation on consumer scepticism (H1), one-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference in scepticism between a high fair trade reputation (M = 3.38; SD = 1.08) and a low fair trade reputation (M = 4.84; SD = 1.15), F(1, 196)=76.15, p<.01). Furthermore, because the group sizes were unequal, Levene’s test indicated equal variances (F (3, 194)=.10; p=.96). In H2, we expected that a high fit between the communicated fair trade identity and the fair trade reputation would lead to less scepticism than a low fit between the communicated fair trade identity and the fair trade reputation. One-way ANOVA revealed that the effect of fit on scepticism was not statistically significant (F(1, 196)=1.71, p=. 19). A high fit did not lead to less scepticism (M = 4.20; SD = 1.40) than a low fit (M = 4.44; SD = 1.25). Again, Levene’s test indicated equal variances (F (1, 196)=1.96; p=.16).

To test H3a, in which we assumed that reputation had an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification, we used the Hayes PROCESS (2012), model 4, using 5000 bootstrap samples. The regression analysis showed that when reputation and brand identification were simultaneously regressed on scepticism, the coefficient of reputation was statistically significant (β = 1.24; SE=.20; p<.01), while the coefficient of identification was also statistically significant (β=–.18; SE=.09; p<.05). In addition, the indirect effect of reputation on scepticism through identification was statistically significant (estimated effect=.22), with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (.03 to .44). Thus, H3a was supported.

To test H3b, in which we assumed that fit had an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification, we used the Hayes PROCESS (2012), model 4, using 5000 bootstrap samples. The regression analysis showed that when fit and brand identification were simultaneously regressed on scepticism, the coefficient of fit was, as expected, not statistically significant (β=.23; SE=.17; p=.19), while the coefficient of identification was statistically significant (β=–.47; SE=.08; p<.01). In addition, the indirect effect of fit on scepticism through identification was not statistically significant (estimated effect=.02), with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval including zero (–.12 to .17). H3b was not supported.

Discussion

Hypothesis 1, in which we proposed that a previous fair trade reputation should have an impact on consumers' scepticism, was supported. This study extends previous research in the CSR context (Bögel Citation2016; Vanhamme and Grobben Citation2009), as in the fair trade context, we also found that companies with a bad fair trade reputation seem to suffer more in terms of the negative reactions of consumers to the brands than companies with a good fair trade reputation. In addition, hypothesis H3a, in which we expected that the relation between the previous fair trade reputation and scepticism is mediated by consumer brand identification, was supported. This result is consistent with previous studies, which found that social identification can play a role in explaining the relation between reputation and company-related outcomes (Hong and Yang Citation2009; Sen and Bhattacharya Citation2001).

In contrast to our expectation that the fit would influence consumer scepticism, H2 was not supported. Although previous research on the fit between a sponsor and its cause showed that a higher fit leads to less scepticism (Elving Citation2013), the present results imply that for the fit between a company's previous reputation and the company's communicated fair trade message, different processes might occur. In the context of fair trade apparel, there did not seem to be many sustainable brands that would fit a 100% communicated message, and therefore, even a 30% communicated message could have led to a lack of fit for less sustainable apparel brands. More specifically, the apparel brands that were perceived as mostly fair trade were still evaluated as being just above the midpoint of the scale, while the apparel brands that were perceived as the least fair trade were evaluated below the midpoint of the scale. These results could be explained by the fact that the number of ethical initiatives in the apparel industry has been low compared to other industries, such as the food industry. Di Benedetto (Citation2017) recently argued that there is a lack of availability and visibility of ethical clothing products in retail stores. More specifically, few clothing brands use ethical labelling as a strategic positioning option (Connolly and Shaw Citation2006). In the food context, Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (Citation2007) compared the positioning of three sustainable food brands, where the brand that was the least sustainable still had some associations with environmental sustainability. In that study, the authors found that clear positioning on sustainability leads to several advantages, such as consumers' advocacy behaviours. Thus, in contrast to Study 1, in Study 2, we chose the cocoa industry as the context, because this industry seems to have more developed fair trade associations.

Study 2

Scepticism and eWOM

Study 2 served two main purposes: (1) to test hypotheses H1 through H3 in a different product category and (2) to extend the model with electronic word-of-mouth as the outcome variable. Previous studies showed that consumer scepticism is negatively related to word-of-mouth intentions (Leonidou and Skarmeas Citation2017; Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013). Moreover, Pérez and de los Salmones (Citation2018) found that negative attitudes towards fair trade have a negative relation with positive WOM intentions. In line with the previous studies on the role of consumer scepticism in offline word-of-mouth, we expected consumer scepticism about the fair trade brand to lead to less positive online word-of-mouth, especially because social media have made it even more convenient to convey positive and negative opinions about a brand (Mangold and Faulds Citation2009). In addition, in the CSR context, these online WOM intentions have become more relevant (Oh and Ki Citation2019). Therefore, we proposed:

H4: Scepticism is negatively related to consumers' positive eWOM about a fair trade brand.

In Study 1, we hypothesized that the relations between a company's fair trade reputation and scepticism, and between fit and scepticism, are mediated by consumer brand identification. We expected that through this mechanism, a company's fair trade reputation and fit also indirectly affect eWOM intentions. In this respect, Skarmeas and Leonidou (Citation2013) found that CSR scepticism mediates the relation between consumers' attitudes towards a company's CSR motives and word-of-mouth intentions. Chung and Lee (Citation2019) recently found that attitudes towards the company mediate the relation between CSR history (ie reputation) and offline word-of-mouth intentions. The authors also found a mediating role for attitudes towards the company between the fit of the CSR topic and the company, and WOM intentions. Following these results, we expect the following:

H5a: Fair trade reputation has an indirect effect on eWOM via consumer-brand identification and scepticism.

H5b: Fit has an indirect effect on eWOM via consumer-brand identification and scepticism.

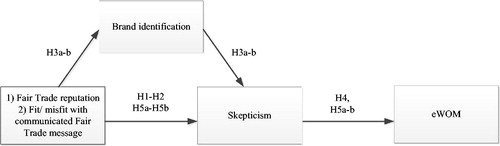

identifies the key constructs included in the second study.

Method Study 2

Context

Since the apparel industry only seemed to have some clearly positioned fair trade brands and a vast number of non-fair trade brands, in Study 2, we used a sector that has already achieved a larger market share of fair trade products. We used cocoa brands that are well known in the Netherlands, as the turnover for fair trade cocoa industry worldwide ($150 billion in 2014) is several times higher than the fair trade cotton industry ($51 billion in 2014) (Fairtrade International 2015). Moreover, the Netherlands is one of the biggest importers of cocoa in the world (CBI, Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Citation2017).

Pre-test

We conducted a pre-test to investigate what brands in the Netherlands are perceived as fair trade brands. Respondents (N = 28) had to evaluate the fair trade reputation of the following six brands: Ben & Jerry’s, Tony’s Chocolonely and Starbucks, which communicate a greater fair trade reputation, versus three ‘regular’ brands, Hertog, Milka and Douwe Egberts. Respondents were first asked to indicate their familiarity with the brand. We removed one respondent that was not familiar with one or more brands. To measure fair trade reputation, we used a three-item scale based on Hsu (Citation2012). We conducted paired sample t tests to choose the brand with the strongest fair trade associations and the brand with the weakest fair trade associations. Tony’s Chocolonely had the strongest reputation concerning fair trade (M = 6.45; SD = 0.98) and Hertog (M = 2.96; SD=.90) and Milka (M = 3.10; SD = 1.05) had the weakest fair trade reputations. A paired sample t test showed that Tonýs Chocolonely had a significantly stronger fair trade reputation than Ben & Jerry’s (t(1, 27)=3.26; p<.01). Since the averages of Hertog and Milka did not differ significantly (t(1, 27)=.81; p=.42), we chose Milka as the brand with the lowest reputation in the main study. In the Netherlands, Hertog is also an ice cream brand (with or without chocolate), while Milka is much more clearly positioned as a chocolate brand.

Sample and procedure main study

To test the hypotheses, we conducted an online experiment with a 2 (high fair trade reputation − low fair trade reputation)×2 (30%−100% fair trade) between-subjects design. The data were collected by convenience sampling. In total, 205 Dutch participants were obtained. The sample comprised 56 males and 149 females with a mean age of 33.3 years (SD = 14.9). 47.5% of the participants had a high educational level (ie at least a bachelor’s degree). Participants from the pre-test were not invited to participate in the main study.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following four conditions in which Fairtrade Netherlands communicates: (1) Tony's Chocolonely is 100% fair trade chocolate; (2) Tony's Chocolonely is 30% fair trade chocolate; (3) Milka is 100% fair trade chocolate; (4) Milka is 30% fair trade chocolate. The participants were first shown a Facebook page of Fairtrade Netherlands. Subsequently, the participants were asked to complete a self-administered survey containing the following measures.

Measures

First, for the manipulation check on fair trade reputation, the same Hsu (Citation2012) scale was used as in the pre-test (Cronbach’s α were .97 for Tony’s Chocolonely and .95 for Milka). Situational scepticism was measured with an adapted version of the advertising scepticism scale of Obermiller and Spangenberg (Citation1998). We used three items on a seven-point Likert scale anchored by ‘totally disagree’ and ‘totally agree’. A sample item includes ‘I am sceptical about whether Milka/Tony’s Chocolonely is a fair trade product’. The reliability of the scale was adequate for both Milka and Tony’s Chocolonely (Cronbach’s α=.80 and .92 respectively). Electronic word of mouth towards the brand was measured with a 3-item 7-point Likert scale from Eisingerich et al. (Citation2015). An example item is ‘To what extent is it likely that you recommend Milka/Tony’s Chocolonely on social sites such as Facebook?’ The reliability of the scale was adequate for both Milka and Tony’s Chocolonely (Cronbach’s α=.79 and .82 respectively). Consumer-brand identification was measured with a 3-item 7-point Likert scale by Leach et al. (Citation2008). The reliability of this scale was good (Cronbach’s α were .93 for Tony’s Chocolonely and .94 for Milka). Additionally, we incorporated brand awareness, credibility of the message and credibility of the source as control variables in the study. We used a single item to measure brand awareness based on Yoo, Donthu, and Lee (Citation2000): ‘I am aware of Milka/Tony’s Chocolonely’. For both credibility of the message and credibility of the source, 2-item 7-point Likert scales were used: ‘The message that I just read is reliable’ and ‘Fairtrade Netherlands is a reliable source’. A confirmatory factor analysis was used to test whether the two dimensions of credibility were perceived as distinct. The two-dimensional model in which both dimensions were correlated (r=.82) showed a much better fit (χ2/df=.90; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA=.00) than the one-dimensional model (χ2/df = 5.57; CFI=.97; TLI=.83; RMSEA=.15). The reliabilities of these scales were good (Cronbach’s α were .83 for credibility of the message and .90 for credibility of the source). Finally, demographic variables (ie age, gender, income and education) were included as descriptive variables in the analyses. Multi-item scales were averaged across their scale items to create composite construct scores.

Results of Study 2

Manipulation check and control variables

The manipulation check showed that participants scored Tony’s Chocolonely significantly higher for fair trade reputation (M = 5.24, SD = 1.27) than Milka (M = 3.22, SD = 1.11; F(1, 203)=146.46, p<.01). Additionally, fair trade Netherlands was perceived as a credible source (M = 5.09, SD = 1.20). An ANOVA showed that there was a non-significant difference between the conditions (F(3, 201)=1.33, p=.27). Finally, participants perceived the Facebook message as being fairly credible (M = 4.71, SD = 1.25). An ANOVA showed that the differences between the conditions were significant (F(3, 201)=3.73, p<.05). A post hoc analysis showed that the Milka 30% fair trade condition was perceived as less credible (M = 4.35, SD = 1.29) than Tony’s Chocolonely 100% fair trade condition (M = 5.07, SD = 1.17).

Hypotheses tests

First, to test the main effect of fair trade reputation on consumer scepticism (H1), the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference regarding scepticism between high fair trade reputation (M = 3.69; SD = 1.36) and low fair trade reputation (M = 4.06; SD = 1.22), F(1, 203)=4.19, p<.05). In H2, we expected that a high fit between the communicated fair trade identity and the fair trade reputation would lead to less scepticism than a low fit between communicated identity and reputation. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of fit on scepticism (F(1, 203)=14.42, p<.01). High fit led to less scepticism (M = 3.55; SD = 1.29) than low fit (M = 4.21; SD = 1.22).

To test H3–H5, we conducted the bootstrapping procedure following Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008) in AMOS 23 (Arbuckle, Citation2014). H3a, in which we assumed that fair trade reputation had an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification, was confirmed. The indirect effect of reputation on scepticism through identification was significant (estimated effect= −.13; p<.01). H3b, in which we assumed that fit had an indirect effect on scepticism via consumer-brand identification, was also confirmed. The indirect effect of fit on scepticism through identification was significant (estimated effect= −.11; p<.05). In H4, we proposed that scepticism is negatively related to the consumers' positive eWOM about a fair trade brand. The direct effect was significant (estimated effect= −.18; p<.05).

Finally, H5a,b, in which we assumed that fair trade reputation and fit had an indirect effect on eWOM via consumer-brand identification and scepticism, were confirmed. The indirect effects of reputation on eWOM through identification (estimated effect=.25; p<.01) and through scepticism (estimated effect=.05; p<.01) were significant. The indirect effects of fit on eWOM through identification (estimated effect= −.22; p<.01) and through scepticism (estimated effect= −.10; p<.01) were also significant.

General discussion

Summary of the findings and discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of previous fair trade reputation and the fit between this reputation and the communicated fair trade message in consumer evaluations of a company's brand. This study contributes to knowledge of consumers' responses to the fair trade communication of organizations. More specifically, the results show that when a company with a strong fair trade reputation communicates fair trade initiatives there is less scepticism regarding these fair trade initiatives. In turn, lower scepticism leads to higher online positive consumer advocacy behaviours. Consumers' identification with the specific brand seemed to be an important mediating variable in this relationship. In contrast to previous reputation, the role of fit between previous reputation and the communicated fair trade initiative in consumers' scepticism was less clear. In Study 1, where the evaluation of the fair trade reputation of the industry in general seems to be rather low, we did not find an effect of fit on scepticism. In Study 2, where the previous fair trade reputation was evaluated much more positively, there was a direct and indirect effect of fit on scepticism.

This study extends the previous research in several ways. First, previous work on consumers' responses to fair trade mostly focused on comparing fair trade with non-fair brands and consumers' willingness to pay for fair trade products (Andorfer and Liebe Citation2012). These fair trade products are mainly signalled by fair trade labels with specific claims (Ingenbleek and Reinders Citation2013). Research has already shown that consumers can be sceptical about these sustainability claims (Mohr, Eroǧlu, and Ellen Citation1998). The results of this study provide more insights into the underlying processes of consumers' situational scepticism (Forehand and Grier Citation2003; Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013). Since the results confirmed that previous fair trade reputation influences scepticism, we follow up on Elving’s (Citation2013) claim that more research is required regarding brands’ reputation and brands’ engagement with pro-social initiatives. We find that, dependent on previous fair trade reputation, consumers' can become more or less sceptical towards the fair trade messages of a company or brand.

Second, this study extends our knowledge of the role of fit in communicating sustainability initiatives. Previous studies have already found that a fit between a company and the social cause in general leads to more positive responses towards the company or brand (Nan and Heo Citation2007) and to greater belief in the credibility of the firm (Becker-Olsen et al. Citation2006). Our study seems to be the first to investigate the effect of fit between a company's previous fair trade reputation and its communicated fair trade message on consumer scepticism. More specifically, we found that communicating different levels of fair trade led to different consumer responses based on consumers' perceptions of the company's previous reputation. Although the results in Study 1 were inconclusive, Study 2 confirmed that a high fit between a company's previous reputation and its communicated fair trade message leads to less scepticism. These results are in line with Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (Citation2010); they argued that the way consumers respond to CSR communication messages is related to the way they perceive the company's previous reputation. An explanation for the inconclusive results in Study 1 could be that participants, given the low score they ascribed to the industry, consider the clothing industry to have a bad reputation and are therefore already sceptical about any fair trade message deriving from any clothing brand. In this context, Shaw et al. (Citation2006) argued that consumers are increasingly aware of child labour and other pertinent issues and concerns in the clothing industry. Moreover, the media have also often reported on scandals about clothing brands that violate ethical norms (Islam and Deegan Citation2010), leading to possible negative perceptions of the ethical awareness of the clothing industry. Since Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (Citation2010) have claimed that consumers' perceptions of suspicious industries could influence the effectiveness of communication about socially responsible behaviour, perhaps the low overall scores for Fair Trade reputation in Study 1 could explain why fit did not influence consumer scepticism in the apparel context.

Third, we further elaborate on underlying processes that explain consumers' situational scepticism by investigating the mediating role of consumer-brand identification. Previous research has already found that identification plays an important role in consumer responses to CSR initiatives (Sen and Bhattacharya Citation2001). More specifically, CSR reputation has proven to lead to stronger consumer-brand identification (He, Li, and Harris Citation2012; Hong and Yang Citation2009). This study extends this work on the role of social identification since we show that strong identification can lead to lower levels of consumer scepticism. Moreover, our results imply that consumer-brand identification seems to at least partly mediate the relationship between a company's previous fair trade reputation and consumer scepticism regarding the communicated fair trade initiative of the company. Study 2 also showed that the relationship between the fit of a company's fair trade reputation and its communicated message and scepticism is partly determined by a consumer's identification with the company.

Finally, the results of our study contribute to a stream of research on consumers' positive online advocacy behaviours (Hennig-Thurau et al. Citation2004). More specifically, we found that in the fair trade context, consumers' scepticism has a negative spillover effect on positive eWOM. The more scepticism there is towards the communicated fair trade message the less consumers are willing to demonstrate positive eWOM. This result extends previous work in the offline context in which scepticism leads to lower positive WOM (Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013). A vast number of studies show that consumers are active online more than ever (Floyd et al. Citation2014; Moriuchi and Takahashi Citation2018; Liu and Park Citation2015). In addition, online word-of-mouth seems to have more social risks because it can reach a larger audience, and the communicated messages are less tailored (Eisingerich et al. Citation2015). Thus, investigating the factors that influence eWOM in response to organizations’ fair trade initiatives can provide valuable insights into how online consumer advocacy can be explained. Our results show that both a company's previous fair trade reputation and the fit between this reputation and the communicated fair trade message have an indirect effect on eWOM via consumer-brand identification and scepticism.

Practical implications

This study has several implications for practice. First, and not surprisingly, reputation matters. Building a reputation on fair trade will have beneficial effects for the company. Managers should realize, however, that this seems to be a long-term investment. Ingenbleek and Reinders (Citation2013) have already demonstrated this for fair trade in the coffee industry; it took more than a decade before the market shares of fair trade coffee rose substantially. Moreover, this rise in market shares was mainly initiated by the market leaders in the industry at that time. Thus, if an organization seeks short-term profit, communicating fair trade initiatives may be a risky endeavour. Moreover, it is important for managers to realize that the fair trade reputation of an industry can have a major effect on consumers' online responses to company initiatives. If you are in a specific industry that has a low fair trade reputation in general (eg the apparel industry), it will be much more difficult to reap the advantages of communicating a fair trade message. Thus, investing in fair trade initiatives in low reputation industries requires a long-term view.

Second, besides the reputation of the company or the industry the company is part of, the fit between reputation and the communicated fair trade message seems to be very important. One could wonder if communicating fair trade initiatives, however sincere the intentions, should be avoided if the fair trade concept is not currently incorporated into the company. In other words, if a fair trade strategy is not (yet) integrated into the core strategy of an organization, communicating fair trade initiatives could backfire and lead to increasingly sceptical responses. Thus, in line with Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (Citation2007), we believe that reaping relational rewards from communicating fair trade seems to be dependent on the clear positioning of the company.

Third, when a company is perceived as having a strong fair trade reputation, this will lead to stronger consumer brand-identification, which in turn leads to more online advocacy behaviours. Thus, for a company to manage its fair trade reputation, developing an identity centred on a fair trade strategy is crucial. Fombrun and Rindova (Citation2000) already suggested that companies who follow an identity-centred approach seem to have the strongest reputations. Managers could therefore invest in creating consumers' sense of belonging to strengthen the bond between the consumer and the brand. More specifically, if consumers perceive a fit between a company's fair trade reputation and its communicated message, using an identity-centred approach could further increase the status of the fair trade reputation and therefore lead to an enhancement of consumers' self-esteem.

Finally, managers should realize that scepticism leads to less positive eWOM. Since greater numbers of consumers are now online, positive online advocacy behaviours could be crucial to building a fair trade reputation. It seems to be important for organizations to keep scepticism as low as possible. Thus, carefully building a fair trade reputation is crucial for establishing consumers' identification with the brand and enhancing their trust in the company.

Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations. First, although most hypotheses were supported, we did not find an effect of fit in Study 1. We argued that this result could be due to the fact that the number of ethical initiatives in the apparel industry has been rather low compared to other industries, such as the food industry. Therefore, we tested the effect of fit on scepticism in another industry with more developed fair trade initiatives. Although we did find this support for the role of fit in scepticism in Study 2, these results should be further confirmed by investigating other industries. Future research could focus on a clear distinction between industries based on the current state of their fair trade initiatives. Moreover, some industries are more complex in the sense that consumers will not always be able to distinguish the different degrees of sustainability of all of the company's products and services (eg financial service providers). For example, a banking company can score high for labour conditions and low for environmental sustainability. Including consumers' awareness of these different forms of sustainability could be important for future research on the effect of fair trade reputation on consumers' responses to fair trade initiatives.

Second, we used a third-party message to communicate the company's fair trade initiatives. Although, in both studies, both the message and the third-party were perceived as credible, one could wonder what the effect on consumer scepticism is when the company communicates the initiatives itself. Research in the crisis communication context, for example, has found that consumers respond differently to a crisis when the crisis message is communicated by an organization versus a third-party (Jin, Liu, and Austin Citation2014). Future research could therefore focus on the distinction of consumer responses to fair trade communications by a third-party versus the company itself.

Third, our study focused on positive online word-of-mouth. Although online consumer communication has increased over the past decade (Chen and Xie Citation2008; Sparks, Perkins, and Buckley Citation2013), research had indicated that consumers with unfavourable product judgments will more often engage in word-of-mouth than consumers with favourable product associations (Anderson Citation1998). Consequently, Leonidou and Skarmeas (Citation2017) argue that it is therefore logical to link scepticism to negative word-of-mouth intentions. Although we found a clear negative relationship between scepticism and positive online advocacy behaviours, the relationship between scepticism and negative word-of-mouth could be included in future research.

Fourth, the way stakeholders perceive companies’ fair trade initiatives may differ. While some initiatives may be seen as genuine/intrinsic (eg fair trade is integrated into the Dutch chocolate brand Tony’s Chocolonely), others may be perceived as forms of green washing/extrinsic (eg Shell is only supporting a local community in Nigeria to gain a more positive reputation). A vast number of studies have emphasized the importance of these so called intrinsic and extrinsic motive attributions in the CSR context (Ellen et al. Citation2006; Schons, Scheidler, and Bartels Citation2017; Vlachos et al. Citation2009). Future research could also include these motive attributions in consumers' responses to communicated fair trade messages.

Finally, studies on CSR regularly focus on consumers' considerations concerning product quality (corporate abilities, CA) and CSR (Brown and Dacin Citation1997; Marín, Cuestas, and Román Citation2016). These CA and CSR associations can have an important influence on consumer brand perceptions (Brown and Dacin Citation1997; Sen and Bhattacharya Citation2001). Previous research has shown various effects of CA and CSR associations on consumer perceptions and behaviours (Chen Citation2001; Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen Citation2007; Feldman and Vasquez-Parraga Citation2013). Future research could investigate the possible mediating or moderating roles that these consumer CA and CSR associations play in the relationship among fair trade reputation, reputation-message fit and consumer scepticism.

Conclusion

This study shows that previous fair trade reputation can play an important role in positive and negative consumer responses towards a brand. Moreover, in low fair trade reputation industries, the fit between a companies’ previous reputation and its communicated message seems to be less important than in industries that have already developed a reputation for fair trade. Consumers will be sceptical about fair trade initiatives in these bad reputation industries anyway. In sum, we conclude that communicating fair trade initiatives can be rewarding. However, whatever context a brand is in, fair trade communication still seems to be a delicate matter and companies should only communicate these initiatives when the ethical shoe fits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jos Bartels

Jos Bartels (PhD, University of Twente) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Cognition at Tilburg University, The Netherlands. His research focuses on internal and external communication, social identification processes, and the role of social media in sustainability behavior of multiple stakeholders in organizations. He has published in several academic journals including Journal of Organizational Behavior, British Journal of Management, Management Communication Quarterly, and Journal of Business Research.

Machiel J. Reinders

Machiel J. Reinders (PhD, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) is Senior Researcher Consumer Behavior and Marketing at Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen Economic Research, The Netherlands. His research focuses on consumer behavior with regard to sustainable and healthy food products and consumer response to food innovations and new technologies. He has published in several academic journals including Journal of Business Research, Journal of Service Research, European Journal of Marketing, and Food Quality and Preference.

Chrissie Broersen

Chrissie Broersen (MSc) received her MSc in Corporate Communication & New Media from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She now works as Team Lead Brand & Crossmedia Research at MeMo2, Amsterdam. MeMo2 is an independent research and consulting firm specialized in measuring and optimizing advertising effects.

Sarah Hendriks

Sarah Hendriks (MSc) received her MSc in Business Communication & New Media from Tilburg University, The Netherlands. She now works as a Communication Specialist at Partos, Civic & Social Organization, Amsterdam. Partos is the Dutch membership body for organizations working in international development.

References

- Aaker, D.A., and K.L. Keller. 1990. Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing 54, no. 1: 27–41.

- Ahearne, M., C.B. Bhattacharya, and T. Gruen. 2005. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology 90, no. 3: 574–85.

- Alberta, N., D. Merunka, and P. Valette-Florence. 2013. Brand passion: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research 66, no. 7: 904–9.

- Anderson, E.W. 1998. Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research 1, no. 1: 5–17.

- Andorfer, V.A., and U. Liebe. 2012. Research on fair trade consumption—a review. Journal of Business Ethics 106, no. 4: 415–35.

- Arbuckle, J.L. 2014. Amos 23.0 user's guide. Chicago: IBM SPSS.

- Bagozzi, R.P., and U.M. Dholakia. 2006. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group Brand communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing 23, no. 1: 45–61.

- Becker-Olsen, K.L., B.A. Cudmore, and R.P. Hill. 2006. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research 59, no. 1: 46–53.

- Bhattacharya, C.B., and S. Sen. 2003. Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing 67, no. 2: 76–88.

- Bögel, P.M. 2016. Company reputation and its influence on consumer trust in response to ongoing CSR communication. Journal of Marketing Communications 25, no. 2: 115–136.

- Bottomley, P.A., and S.J. Holden. 2001. Do we really know how consumers evaluate brand extensions? Empirical generalizations based on secondary analysis of eight studies. Journal of Marketing Research 38, no. 4: 494–500.

- Brown, T.J., and P.A. Dacin. 1997. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing 61, no. 1: 68–84.

- Carrington, M.J., B.A. Neville, and G.J. Whitwell. 2010. Why ethical consumers don't walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics 97, no. 1: 139–58.

- Carrol, A.B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34, no. 4: 39–48.

- Castaldo, S., F. Perrini, N. Misani, and A. Tencati. 2009. The missing link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The case of fair trade products. Journal of Business Ethics 84, no. 1: 1–15.

- CBI, Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2017. https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/cocoa/netherlands/, retrieved November 2017.

- Cha, M.K., Y. Yi, and R.P. Bagozzi. 2016. Effects of customer participation in corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs on the CSR-Brand fit and brand loyalty. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 57, no. 3: 235–49.

- Chen, A.C.‐H. 2001. Using free association to examine the relationship between the characteristics of brand associations and brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management 10, no. 7: 439–51.

- Chen, Y., and J. Xie. 2008. Online consumer review: Word-of-mouth as a new element of marketing communication mix. Management Science 54, no. 3: 477–91.

- Chung, A., and K.B. Lee. 2019. Corporate apology after bad publicity: A dual-process model of CSR fit and CSR history on purchase intention and negative word of mouth. International Journal of Business Communication: 1–20. DOI:10.1177/2329488418819133.

- Connolly, J., and D. Shaw. 2006. Identifying fair trade in consumption choice. Journal of Strategic Marketing 14, no. 4: 353–68.

- Cornelissen, J.P. 2017. Corporate communication: a guide to theory and practice, 5th ed. London: Sage publications.

- De Pelsmacker, P.,. L. Driesen, and G. Rayp. 2005. Do consumers care about ethics? willingness to pay for Fair-Trade coffee. Journal of Consumer Affairs 39, no. 2: 363–85.

- De Vries, G., B.W. Terwel, N. Ellemers, and D.D. Daamen. 2015. Sustainability or profitability? How communicated motives for environmental policy affect public perceptions of corporate greenwashing. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22, no. 3: 142–54.

- Di Benedetto, C.A. 2017. Corporate social responsibility as an emerging business model in fashion marketing. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 84, no. 4: 251–65.

- Dickson, M.A. 2001. Utility of no sweat labels for apparel consumers: Profiling label users and predicting their purchases. Journal of Consumer Affairs 35, no. 1: 96–119.

- Didier, T., and S. Lucie. 2008. Measuring consumer's willingness to pay for organic and fair trade products. International Journal of Consumer Studies 32, no. 5: 479–90.

- Du, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S. Sen. 2007. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24, no. 3: 224–41.

- Du, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S. Sen. 2010. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility CSR: the role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Reviews 12, no. 1: 8–19.

- Du, S., and E.T. Vieira. 2012. Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. Journal of Business Ethics 110, no. 4: 413–27.

- Eisingerich, A.B., H.H. Chun, Y. Liu, H.(M.). Jia, and S.J. Bell. 2015. Why recommend a Brand face-to-face but not on Facebook? How word-of-mouth on online social sites differs from traditional word-of-mouth. Journal of Consumer Psychology 25, no. 1: 120–8.

- Ellen, P.S., D.J. Webb, and L.A. Mohr. 2006. Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34, no. 2: 147–57.

- Elving, W.J. 2013. Scepticism and corporate social responsibility communications: the influence of fit and reputation. Journal of Marketing Communications 19, no. 4: 277–92.

- Escalas, J.E., and J.R. Bettman. 2003. You are what they eat: the influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology 13, no. 3: 339–48.

- Fairtrade International, FLO 2015. Scope and benefits of fairtrade. 7th ed.

- Fairtrade International, FLO 2017. https://monitoringreport2016.fairtrade.net/en/, retrieved December 2017.

- Feldman, M.P., and A.Z. Vasquez-Parraga. 2013. Consumer social responses to CSR initiatives versus corporate abilities. Journal of Consumer Marketing 30, no. 2: 100–11.

- Floyd, K., R. Freling, S. Alhoqail, H.Y. Cho, and T. Freling. 2014. How online product reviews affect retail sales: A meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing 90, no. 2: 217–32.

- Fombrun, C.J., and V.P. Rindova. 2000. The road to transparency: Reputation management at royal Dutch/shell. The Expressive Organization 7: 7–96.

- Fombrun, C., and M. Shanley. 1990. What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal 33, no. 2: 233–58.

- Forehand, M.R., and S. Grier. 2003. When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology 13, no. 3: 349–56.

- Frank, R., M. Unfried, R. Schreder, and A. Dieckmann. 2016. Ethical textile consumption: Only a question of selflessness? GfK Research 8, no. 1: 53–7.

- Goworek, H., T. Fisher, T. Cooper, S. Woodward, and A. Hiller. 2012. The sustainable clothing market: an evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 40, no. 12: 935–55.

- Gupta, S., and J. Pirsch. 2006. The company-cause-customer fit decision in cause-related marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing 23, no. 6: 314–26.

- Hayes, A.F. 2012. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [white paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- He, H.,. Y. Li, and L. Harris. 2012. Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research 65, no. 5: 648–57.

- Hennig-Thurau, T.,. K.P. Gwinner, G. Walsh, and D.D. Gremler. 2004. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing 18, no. 1: 38–52.

- Herédia-Colaço, V., R.C. do Vale, and S.B. Villas-Boas. 2019. Does fair trade breed contempt? A cross-country examination on the moderating role of brand familiarity and consumer expertise on product evaluation. Journal of Business Ethics 156, no. 3: 737–758.

- Hinton, G.E., and J.A. Anderson, eds. 2014. Parallel models of associative memory: Updated edition. New York and London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hong, S.Y., and S.U. Yang. 2009. Effects of reputation, relational satisfaction, and customer–company identification on positive word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Public Relations Research 21, no. 4: 381–403.

- Hsu, K.-T. 2012. The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics 109, no. 2: 189–201.

- Ingenbleek, P.T., and M.J. Reinders. 2013. The development of a market for sustainable coffee in The Netherlands: Rethinking the contribution of fair trade. Journal of Business Ethics 113, no. 3: 461–74.

- Inoue, Y., and S. Lee. 2011. Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tourism Management 32, no. 4: 790–804.

- Islam, M.A., and C. Deegan. 2010. Media pressures and corporate disclosure of social responsibility performance information: a study of two global clothing and sports retail companies. Accounting and Business Research 40, no. 2: 131–48.

- Jin, Y., B.F. Liu, and L.L. Austin. 2014. Examining the role of social media in effective crisis management: The effects of crisis origin, information form, and source on publics’ crisis responses. Communication Research 41, no. 1: 74–94.

- Jin, S.A.A., and J. Phua. 2014. Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising 43, no. 2: 181–95.

- Kim, Y.J., and W.N. Lee. 2009. Overcoming consumer skepticism in cause-related marketing: the effects of corporate social responsibility and donation size claim objectivity. Journal of Promotion Management 15, no. 4: 465–83.

- Kozlowski, A., M. Bardecki, and C. Searcy. 2012. Environmental impacts in the fashion industry: A life-cycle and stakeholder framework. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 45: 17–36.

- Laczniak, R.N., T.E. Decarlo, and S.N. Ramaswami. 2001. Consumers’ response to negative word-of-mouth communication: An attribution theory perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology 11, no. 1: 57–73.

- Lam, S.K., M. Ahearne, Y. Hu, and N. Schillewaert. 2010. Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: A social identity theory perspective. Journal of Marketing 74, no. 6: 128–46.

- Leach, C.W., M. van Zomeren, S. Zebel, M.L.W. Vliek, S.F. Pennekamp, B. Doosje, J.W. Ouwerkerk, and R. Spears. 2008. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical multicomponent model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95, no. 1: 144–65.

- Leonidou, C.N., and D. Skarmeas. 2017. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. Journal of Business Ethics 144, no. 2: 401–15.

- Li, Y., B. Liu, and T.C.T. Huan. 2019. Renewal or not? Consumer response to a renewed corporate social responsibility strategy: Evidence from the coffee shop industry. Tourism Management 72: 170–9.

- Lii, Y.S., and M. Lee. 2012. Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics 105, no. 1: 69–81.

- Liu, Z., and S. Park. 2015. What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tourism Management 47: 140–51.

- Ma, Y.J., H.H. Lee, and K. Goerlitz. 2016. Transparency of global apparel supply chains: Quantitative analysis of corporate disclosures. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 23, no. 5: 308–18.

- Maloni, M.J., and M.E. Brown. 2006. Corporate social responsibility in the supply chain: An application in the food industry. Journal of Business Ethics 68, no. 1: 35–52.

- Mangold, W.G., and D.J. Faulds. 2009. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business Horizons 52, no. 4: 357–65.

- Marín, L., P.J. Cuestas, and S. Román. 2016. Determinants of consumer attributions of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 138, no. 2: 247–60.

- Mohan, S. 2009. Fair trade and corporate social responsibility. Economic Affairs 29, no. 4: 22–8.

- Mohr, L.A., D. Eroǧlu, and P.S. Ellen. 1998. The development and testing of a measure of skepticism toward environmental claims in marketers' communication. Journal of Consumer Affairs 32, no. 1: 30–55.

- Montoro Rios, F.J., T. Luque Martinez, F. Fuentes Moreno, and P. Cañadas Soriano. 2006. Improving attitudes toward brands with environmental associations: An experimental approach. Journal of Consumer Marketing 23, no. 1: 26–33.

- Moriuchi, E., and I. Takahashi. 2018. An empirical investigation of the factors motivating Japanese repeat consumers to review their shopping experiences. Journal of Business Research 82: 381–90.

- Nan, X., and K. Heo. 2007. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility CSR initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. Journal of Advertising 36, no. 2: 63–74.

- Obermiller, C., and E.R. Spangenberg. 1998. Development of a scale to measure consumer skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Consumer Psychology 7, no. 2: 159–86.

- Obermiller, C., C. Burke, E. Talbott, and G.P. Green. 2009. Taste great or more fulfilling’: The effect of brand reputation on consumer social responsibility advertising for fair trade coffee. Corporate Reputation Review 12, no. 2: 159–76.

- Öberseder, M., B.B. Schlegelmilch, P.E. Murphy, and V. Gruber. 2014. Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Ethics 124, no. 1: 101–15.

- Oh, J., and E.J. Ki. 2019. Factors affecting social presence and word-of-mouth in corporate social responsibility communication: Tone of voice, message framing, and online medium type. Public Relations Review 45, no. 2: 319.

- Osgood, C.E., and P.H. Tannenbaum. 1955. The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Psychological Review 62, no. 1: 42–55.

- Pérez, A., and I.R. Del Bosque. 2013. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. Journal of Business Ethics 118, no. 2: 265–86.

- Pérez, A., and M.D.M.G. de los Salmones. 2018. Information and knowledge as antecedents of consumer attitudes and intentions to buy and recommend Fair-Trade products. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 30, no. 2: 111–33.

- Polonsky, M.J., and R. Speed. 2001. Linking sponsorship and cause related marketing: Complementarities and conflicts. European Journal of Marketing 35, no. 11/12: 1361–89.

- Pracejus, J.W., and G.D. Olsen. 2004. The role of brand/cause fit in the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. Journal of Business Research 57, no. 6: 635–40.

- Preacher, K.J., and A.F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40, no. 3: 879–91.

- Reinders, M.J., and J. Bartels. 2017. The roles of identity and brand equity in organic consumption behavior: Private label brands versus national brands. Journal of Brand Management 24, no. 1: 68–85.