Abstract

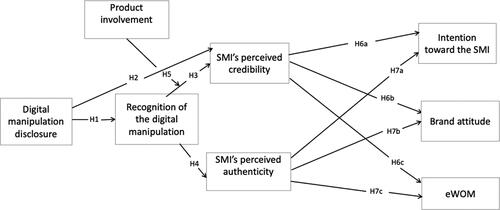

There is an ongoing discussion on the necessity of implementing disclosures for digitally manipulated pictures within the branded content of social media influencers (SMIs). To address this, we conducted two online survey-based between-subjects experiments to assess the effectiveness of digital manipulation disclosures used on Instagram by an SMI. In the first study (N = 99), we examined how a visual prominent disclosure placed directly on the sponsored posts of an SMI, mediated by the recognition of digital manipulation and the perceived authenticity of the SMI, influenced participants’ intentions toward the SMI, their brand attitude, and their likelihood in engaging in electronic Word-of-Mouth. In the second study (N = 155), we manipulated three conditions: the absence of digital manipulation, the presence of digital manipulation without disclosure, and the presence of digital manipulation with disclosure. We investigated the effects of digital manipulation on the perceived credibility of the SMI and on brand related factors, mediated by the recognition of digital manipulation. Moreover, we explored the moderating effects of product involvement on the relationship between digital manipulation recognition and source credibility. Recognizing digital manipulation has no effects on the perceived authenticity of the SMI. Among social media users with high levels of product involvement who can recognize the digital manipulation, the perceived credibility of the SMI tends to be lower. The research holds both theoretical and practical implications for the field of influencer marketing and disclosure practices.

Introduction

Digital manipulation of visual content is a widespread practice on social media. Instagram is a platform where aesthetics plays a relevant role (Hund Citation2017), and therefore, users often enhance their visual appearance by using accessible tools (Fardouly, Willburger, and Vartanian Citation2018; Vendemia and De Andrea Citation2018). Scholars consider disclosing digitally enhanced pictures as an option to warn consumers about possible deceiving practices (Campbell et al. Citation2022).

An ongoing discussion centers around the necessity to regulate incorporating disclosures for digitally manipulated pictures showcased in advertising (e.g. in the United Kingdom and Germany). With the goal of educating consumers about this practice, policymakers in numerous European countries have already enacted legislative frameworks. As a result, in 2017, France passed a law regarding labeling retouched photos used for commercial purposes (Daldorph Citation2017) and in 2021, Norway legislated mandatory labeling of digitally enhanced pictures posted by social media influencers (SMIs) when publishing sponsored content (Gray Citation2021). However, the effectiveness of disclosing digitally enhanced pictures remains a topic of debate.

Previous studies stressed the negative impact on subjective well-being as a result of the exposure to digitally manipulated pictures that often depict an unrealistic body image (e.g. Brown and Tiggemann Citation2020; Coutoure and Harrison Citation2020; Fardouly and Holland Citation2018). However, to this date, only few studies, mostly in traditional media settings, explored the effects of photo edit disclosures on advertising outcomes showing a lack of effectiveness (e.g. Harmon and Rudd Citation2016; Kwan et al. Citation2018; Slater et al. 2012). Considering that social media influencers (SMIs) have become, in recent years, relevant advertising actors to promote businesses (Ye, Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021) research on the impact of disclosing digitally manipulated images showcased in social media influencer (SMI) sponsored content is needed.

Although SMIs receive compensation for their content (Campbell and Grimm Citation2019), they wield significant persuasive power within their follower communities and are often perceived as honest product reviewers (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). Hence, SMI’s perceived credibility (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021; Ki and Kim Citation2019; Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Munnukka, Uusitalo, and Toivonen Citation2016; Nafees et al. Citation2021) and authenticity (Lee and Eastin Citation2021) are crucial elements of the persuasive mechanism behind influencer advertising. However, there is intense competition among content creators for users’ attention on social media (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). Therefore, it is crucial to look at consumers’ involvement with the promoted products that increases their attention and cognitive processing (Celsi and Olson 1998). Hence, when exploring the effects of digital disclosures we considered product involvement, which refers to the relevance of the product endorsed by a SMI to their audience.

Our research specifically addresses the impact of digitally manipulated pictures used by SMIs in branded content, covering both influencer-related outcomes and advertising outcomes, such as the intention toward the influencer, brand attitude, and electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM). Thus, we look at the effectiveness of a visual prevalent clearly worded disclosure label placed directly on the branded posts in recognizing digital manipulation. Furthermore, we aim to investigate how recognizing digital manipulation affects SMI’s perceived credibility and authenticity. The focus on the moderating effect of product involvement when investigating the effects of recognizing digital disclosures on SMIs’ credibility is central to our investigation of SMI advertising.

Literature review and hypotheses

Disclosures and digital manipulation recognition

The practice of picture manipulation is on the rise and gaining popularity within the advertising industry (Campbell et al. Citation2022). While enhancing visual appearances is not a new practice and has been undertaken in analog settings, such as print magazines or outdoor advertising, the extensive array of digital manipulation tools and the scale of this phenomenon represent a new dimension in this practice. The aim of disclosures is to enable audiences to recognize digitally manipulated pictures. Disclosures must come in a form that effectively help consumers recognize digitally enhanced pictures as such (Naderer, Peter, and Karsay Citation2021). The effectiveness of disclosures, therefore, hinges on their ability to command attention and convey clarity to the audience (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023). Revealing digital manipulation and commercial connections in SMI advertising play distinct roles in providing transparency to audiences. Digital manipulation disclosures are designed to inform viewers about any alterations made to visual content through photo editing tools (Coutoure and Harrison Citation2020; Fardouly and Holland Citation2018). On the other hand, sponsorship disclosures aim to reveal the material connection or financial arrangement between the SMI and a brand or product mentioned in the content, focusing on business affiliations and potential financial interests (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2023; Campbell and Grimm Citation2019). These two types of disclosures serve different purposes and have a different history of implementation.

The Persuasion Knowledge Model (Friestad and Wright Citation1994) often served as a theoretical framework for understanding the mechanism behind sponsorship disclosures. Thus, ad disclosures help recipients to activate and retrieve the general knowledge and beliefs they have accumulated over time about advertising (Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2019; Eisend et al. Citation2020), which relates to the cognitive dimension of persuasion knowledge (PK) (Boerman et al. Citation2018). Every new encounter with advertising content, every persuasive attempt adds to the conceptual persuasion knowledge of media recipients. The concept of advertising literacy builds on PK (Rozendaal et al. Citation2011; Zarouali et al. Citation2019). It primarily pertains to advertising as a form of persuasive communication. Disclosures activate advertising literacy (Boerman, Rozendaal, and van Reijmersdal Citation2023). While advertising disclosures in SMIs’ branded content are mandatory in many countries, digital manipulation disclosures are relatively new to the public.

Previous existing scholarship on sponsorship disclosure in SMI advertising can contribute to the research on the efficacy of digital manipulation disclosures. Hence, studies focusing on sponsorship transparency highlighted that disclosures should be obvious to consumers, straightforward, and noticeable (Campbell and Grimm Citation2019; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016) and that they must be understood by the target audiences to which they are presented (Naderer, Peter, and Karsay Citation2021), suggesting that subtlety or placement within a cluster of hashtags may hinder their effectiveness. Campbell and Grimm (Citation2019) emphasize that advertising disclosures should be straightforward and conspicuous, while Wojdynski and Evans (Citation2016) found that placing disclosures among other hashtags does not contribute significantly to advertising recognition. These findings collectively suggest that the visual salience and clarity of disclosures play a pivotal role in their efficacy.

The few studies focusing on photo edit disclosures in social media settings have consistently employed disclaimers placed as captions (Brown and Tiggemann Citation2020; Coutoure and Harrison Citation2020; Fardouly and Holland Citation2018; Livingston, Holland, and Fardouly Citation2020; McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021). However, these studies did not find a significant effect from either form of caption on women’s body satisfaction or mood.

It is noteworthy that these studies employed various types of captions, ranging from self-disclaimers in the form of body positive captions or hashtags (Brown and Tiggemann Citation2020) to captions either idealizing or criticizing the retouched images (Coutoure and Harrison Citation2020). Other variations included generic self-disclaimers of a more general nature or specific self-disclaimers detailing the altered body parts (McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021). Conversely, Naderer, Peter, and Karsay (Citation2021) have created standard disclaimers placed as captions, testing their efficacy on the perceived realism of the presented images. Intriguingly, neither disclaimer type, whether placed as a caption or as a hashtag, demonstrated a significant effect when compared to a no-disclaimer condition. However, drawing from the above-mentioned studies on advertising disclosure (e.g. Campbell and Grimm Citation2019; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016) we argue that disclosing digitally manipulated SMI’s branded posts by placing a clearly worded label directly on the branded posts can contribute to the recognition of such digital manipulation and therefore we posit:

H1. The presence of a digital manipulation disclosure enhances the recognition of digitally manipulated pictures, compared to the absence of a disclosure on a digitally manipulated picture.

The effects of digital manipulation disclosure on SMI’s perceived credibility and authenticity

In addition to the cognitive aspects related to recognizing the persuasive intent, the PK framework also includes an evaluative dimension. This dimension involves the affective component of persuasion knowledge, encompassing critical attitudes or feelings, such as skepticism or disliking towards the persuasive message (Boerman et al. Citation2018; Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016).

Persuasion knowledge is related to source credibility that refers to the users’ perception of the communication source (Hovland and Weiss Citation1951; Metzger and Flanagin Citation2015) and it is a relevant asset for SMIs (Balaban and Mustățea Citation2019; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017). Consistent with the rationale of the PK model, individuals perceive and evaluate the credibility of SMIs considering the recognition of the advertising intent. If they are aware of the persuasion tactics of the SMIs they might scrutinize the credibility of the SMI closely.

Various studies (De Jans et al. Citation2020; Grigsby Citation2020; van Reijmersdal and van Dam Citation2020) collectively suggest that advertising disclosures lead to advertising recognition, which can have negative effects on brand attitude and influencer perceptions, such as the intention toward the SMI. The intention toward the SMI refers to the audience’s intent to follow the influencer and engage with their content (Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015). van Reijmersdal and van Dam (Citation2020) identified a negative influence of advertising recognition on both brand attitudes and attitudes toward the influencer, attributing this outcome to heightened attitudinal persuasion. Grigsby (Citation2020) further revealed that ad recognition led to perceptions of pushiness, thereby negatively impacting both ad and brand attitudes. Additionally, De Jans et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the mediating roles of influencers’ assessments, particularly in terms of credibility, where sponsorship disclosures led to advertising recognition, triggering skepticism, and reducing the influencer’s credibility, resulting in lower brand attitudes and brand recognition.

However, there are also studies indicating that consumers perceive advertisement disclosures as a sign of transparency displayed by influencers (Balaban, Mucundorfeanu, and Naderer 2022; Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy Citation2019; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023; Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy Citation2018). The persuasive message is conveyed openly, and users do not feel deceived (Abendroth and Heyman Citation2013). Consequently, this positively affects the credibility of the advertiser (Hwang and Jeong Citation2016), the credibility of the blogger, measured as trust (Colliander and Erlandsson Citation2015), and the perceived trustworthiness of an SMI (Audrezet, de Kerviler, and Moulard Citation2020). Trustworthiness and likeability are elements of the source credibility of actors engaged in embedded advertising, such as SMIs and bloggers (Audrezet, de Kerviler, and Moulard Citation2020; Colliander and Erlandsson Citation2015; Lou and Yuan Citation2019).

Overall, existing literature (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023) indicates that the impact of disclosures may depend on their efficacy in informing consumers about their intended purpose (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023). Transparent advertising disclosures play a crucial role in mitigating negative effects associated with heightened persuasion knowledge, ultimately fostering positive perceptions of SMIs, and increasing engagements with posts (Giuffredi-Kähr, Petrova, and Malär Citation2022; Karagür et al. Citation2022). Unlike traditional advertising disclosures, photo edit disclosure transparently communicating image alterations without direct reference to persuasive intent, have the potential to positively affect audience perceptions, aligning with consumer preferences for transparency in advertising (Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy Citation2019). Consequently, we hypothesized:

H2. Digital manipulation disclosure has a positive impact on SMI’s perceived credibility.

H3. The recognition of the digital manipulation has a negative impact on SMI’s credibility.

In the context of our study, we anticipate that recognizing digital alterations in pictures, which deviate from the unedited content that enhances authenticity perception, may have a negative impact on authenticity. The transparency introduced by the disclosure could disrupt the seamless presentation of unedited content, potentially leading followers to question the authenticity of the SMI. We thus, assume the following:

H4. The recognition of the digital manipulation has a negative impact on SMI’s perceived authenticity.

The moderating role of product involvement

Regardless of the type of advertising, source credibility is a strong predictor for advertising outcomes and has substantial effects when combined with emotions and cognitions (Eisend and Tarrahi Citation2016). Product involvement defined as the personal relevance of a product for the consumer (O’Cass Citation2000) affects consumer attention and the comprehension process (Krugman Citation1966). Previous literature on advertising disclosures (Eisend et al. Citation2020) highlighted that product characteristics influence the impact of disclosures. Thus, high product involvement can lead to increased processing of advertising content (Krugman Citation1966) and tends to prompt recipients to engage in a more thorough and careful evaluation of advertising messages (Celsi and Olson 1998). Therefore, when product involvement is high in the context of recognizing digital manipulation, consumers are likely to engage in a more critical assessment of the influencer’s credibility. As a result, we anticipate significant interaction effects between product involvement and the recognition of digital manipulation on the perceived credibility of the SMI. Thus, we hypothesized:

H5. Product involvement moderates the relationship between the recognition of digital manipulation and the perceived credibility of the SMI, in the sense that individuals with high levels of product involvement who recognize digital manipulation will rate the SMI’s perceived credibility lower.

The impact of SMI’s perceived credibility and authenticity on advertising outcomes

Robust scholarship stressed that credibility plays a crucial role in the persuasive processes for all types of endorsers (Eisend and Tarrahi Citation2016). In the context of SMI advertising, previous research has highlighted the favorable impact of SMI’s credibility on outcomes related to both the influencer and the brand. Hence, increased credibility of the SMI has favorable implications for both the intention towards the SMI (Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015) and the endorsed brand (Balaban, Mucundorfeanu, and Mureșan Citation2022; Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Munnukka, Uusitalo, and Toivonen Citation2016). This aspect is crucial for SMIs as strategic communicators (Enke and Borchers Citation2019) given that SMIs aspire to grow their community of followers (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020).

In addition, users actively engage in electronic-Word-of-Mouth (eWOM) by sharing the SMI’s posts within their own follower communities. eWOM holds significance for both brands and SMIs since it results in the sponsored content gaining exposure beyond the SMI’s immediate audience. When followers engage with and share content, it reaches users who may not be directly connected to the SMI (Evans et al. Citation2017). This sharing mechanism widens the content’s visibility, making it accessible to potential audiences who might not have been exposed to the brand or influencer otherwise. In essence, eWOM creates a ripple effect turning followers into brand advocates who organically introduce the content to new and diverse audiences, enhancing the overall reach and exposure of the sponsored material (Balaban, Szambolics, and Chirică Citation2022).

Previous research highlighted the relevance of SMI’s perceived authenticity for resulting in various advertising outcomes. These outcomes encompass brand-related aspects, such as brand attitude and purchase intention, as well as factors pertaining to the content creator as an advertising figure, including the intention toward the SMI (Fritz, Schoenmueller, and Bruhn Citation2017; Kühn and Riesmeyer Citation2021; Pöyry et al. Citation2019; Schallehn, Burmann, and Riley Citation2014). Hence, followers favor SMIs that are thought to be authentic, and this preference results in affective and behavioral outcomes (Jin Citation2018). The intention toward the SMI is crucial given that the goal of SMIs is to grow their community of followers (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). According to previous research, users are more likely to choose the endorsed brand if they perceive the SMI as authentic (Ki et al. Citation2020; Kowalczyk and Pounders Citation2016). Hence, we posit:

H6. The perceived credibility of the SMI has a positive impact on (a) the intention toward the SMI, (b) brand attitude, and (c) eWOM.

H7. The perceived authenticity of the SMI has a positive impact on (a) the intention toward the SMI, (b) brand attitude, and (c) eWOM.

Method

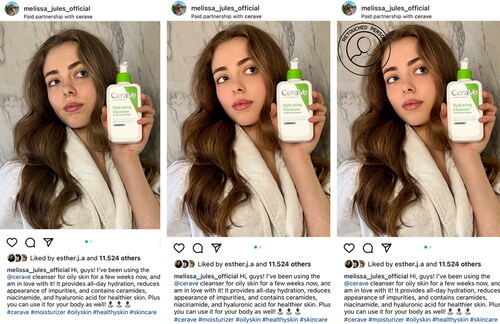

We conducted two studies to examine the effects of a digital manipulation disclosure used in sponsored SMI posts. We examined the impact of a manipulation disclosure placed directly on the pictures as a stamp used in sponsored SMI posts, a disclosure type that is applicable and mandatory in Norway. This labeling standard represents the singular method currently employed for disclosing edited pictures on social media platforms. It entails directly integrating the photo editing disclosure onto the image itself.

In the first study, we looked at the impact of a digital manipulation disclosure mediated by the digital manipulation recognition and perceived authenticity of the SMI on the intention toward the influencer, brand attitude, and eWOM. Building on the first study, in Study 2 we investigated the effectiveness of the digital manipulation disclosure mediated by the digital manipulation recognition and perceived credibility of the SMI on the intention toward the influencer, brand attitude, and eWOM. In both studies, only branded posts were subjected to digital manipulation and disclosure. Branded posts were digitally enhanced to increase the SMI’s facial symmetry, enlarge her lips and eyes, and make her body appear very fit.

Study 1

Method

We conducted an online survey-based between-subjects experiment by manipulating the absence (n1 = 73) vs. the presence (n2 = 80) of a photo manipulation disclosure. We examined different mediators, including the digital manipulation recognition and the perceived authenticity of the SMI. The disclosure tested was worded as ‘Retouched person’ (original wording in German: ‘Retuschierte Person’) and placed as a stamp directly on the digitally modified photos of an SMI, in compliance with the new regulations in countries like Norway (Gray Citation2021). The label was positioned in the upper left-hand corner of the pictures, contrasting the background, and adhering to the imposed size and fonts. Our stimulus materials depicted a fictitious female SMI’s Instagram account (33,000 followers), endorsing the brand Adidas.

Design and stimulus materials

We created a fictitious Instagram page for the influencer by sourcing the images from a public Instagram account from a different country than the country where our research was conducted. This approach is consistent with established practices in previous studies involving manipulated pictures, where images were drawn from public Instagram accounts (e.g. Livingston, Holland, and Fardouly Citation2020, McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021, Tiggemann and Anderberg Citation2020). We have given the influencer a new name, manipulated the follower count, created captions, and included likes for all posts. Moreover, we asked participants if they were familiar with the SMI and received no positive answers. The three branded pictures were further enhanced for the study using Adobe Photoshop 24.1.

Participants in both groups used their mobile phones to complete a survey distributed via a Qualtrics link, which consisted of three parts. In the first part, after providing informed consent, respondents were asked about their socio-demographics and social media usage. In the second part, they were shown the account information of our fictitious SMI and then presented with six Instagram posts from the SMI. Among these posts, three were branded content featuring the influencer promoting sports clothing from the brand Adidas.

In the three branded posts that were disclosed, we deliberately enhanced specific features of the SMI’s physical appearance. The advertising disclosure worded ‘Paid partnership with Adidas’ was positioned above the digitally modified photos of the branded posts, that being standardized disclosure commonly used on Instagram. The digital manipulation disclosure was placed as a stamp on the pictures showing brand endorsement.

The first group viewed the posts without any digital manipulation disclosure, while the second group saw the exact same posts but with the digital manipulation disclosure included. Advertising disclosure, a mandatory practice in Germany, was not a factor in this experiment and was shown to both groups. Examples of the posts considered as stimulus materials are presented in Appendix A.

In the third part of the survey, we asked participants to assess our mediators and dependent variables. Furthermore, to draw attention to the potential adverse effects of digitally enhanced images, as emphasized in previous research, our participants were presented with the following disclaimer after completing the questionnaire: ‘Instagram users frequently digitally edit their photos. Digitally manipulated photographs do not represent an attainable standard of beauty. Each individual possesses their own unique and inherent beauty, and we encourage you to discover and embrace your inner and outer beauty beyond the beauty ideals promoted on social media and in the media.’

Participants

For this study, initially, 153 participants were recruited through the crowdsourcing platform Prolific, known for providing high data quality and being a relevant tool for conducting online experiment-based surveys (Palan and Schitter Citation2018). Participants, fluent in German and Instagram users, were rewarded ∼5 euros for viewing the stimulus material and completing the questionnaire on their mobile phones. Half of the participants in the disclosure group (n = 40) reported seeing the disclosure ‘Retouched person.’ Moreover, 14 respondents (19.17%) from the no-disclosure reported also seeing the disclosure ‘Retouched person.’ Therefore, the manipulation check was successful (χ2(1) = 15.88, p < .001, Φ = .32). Aligned with previous research (McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021) we excluded for further analysis participants who failed to pass the manipulation check. Hence, our final sample consists of N = 99, 50.5% female, 46.5% male young adults, and 3% other gender, aged 18–33 (M = 22.63, SD = 4.07).

Measures

Respondents were asked to rate our mediators, first the manipulation recognition with a single question on a scale from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree (M = 4.83, SD = 1.54) and their perceived authenticity of the SMI was measured using 14 questions on a 7-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘The influencer gives very honest reviews on brands’ from 1 = ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘very much’; α = .92, M = 3.88, SD = .87; Lee and Eastin Citation2021). The dependent variable the intention toward the SMI rated on a 7-point Likert scale using four questions (e.g. ‘I would like to know more about this influencer’, from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’; α = .93, M = 1.92, SD = 1.07; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015), and brand attitude on a 7-point Likert point semantic differential scale with the attributes ‘unattractive’-’attractive’, ‘negative’-’positive’, ‘boring’-’interesting’, and ‘unlikeable’-’likeable’ (α = .92, M = 4.56, SD = 1.35; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). Moreover, eWOM was assessed by participants on a 7-point Likert scale using four questions (e.g. ‘I would share these posts and/or stories with my Instagram friends’, from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’; α = .94, M = 1.72, SD = 1.05; Sohn Citation2009; Evans et al. Citation2017).

For the randomization checks, we considered self-photo manipulation measured using four questions on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘I often make specific parts of my body look larger or look smaller’ from 1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’; α = .72, M = 2.01, SD = .82; Gioia et al. Citation2021) and body appreciation that was measured using six questions also on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘I take a positive attitude towards my body’, from 1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’; α = .87, M = 3.81, SD = .68; Slater, Varsani, and Diedrichs Citation2017).

Results

Randomization checks for age [t (97) = −0.19, p = .78], gender [χ2(2) = .99, p = .61], body appreciation [t (97) = −1.10, p = .97], and self-photo manipulation [t (97) = 1.04, p = .49] showed that the differences between outcome variables are not a result of inherent differences between conditions. Descriptive statistics per condition and between-subjects differences are presented in , while bivariate correlations for mediators and dependent variables are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive analysis and between-subjects differences for Study 1.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations Study 1.

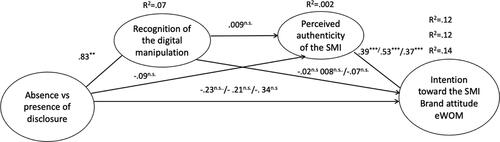

In Study 1 we tested the effects of the disclosure on the digital manipulation recognition (H1) and the impact of the recognition on the perceived authenticity of the SMI (H4). Furthermore, we tested how the perceived authenticity of the SMI affects (a) the intention toward the SMI (H7a), (b) brand attitude (H7b), and (c) eWOM (H7c). We conducted three serial mediation analyses for each dependent variable, intention toward the SMI, brand attitude, and eWOM with digital manipulation recognition and the perceived authenticity of the SMI as mediators. We used Model 6, PROCESS macro 3 in SPSS (Hayes Citation2022) employing 5000 bootstrap samples. The no-disclosure group was used as a reference group.

We posited that the presence of a disclosure contributes to digital manipulation recognition (H1). Disclosure has a direct significant impact on the recognition of digitally manipulated pictures (b = .83, SE = .31, 95% CI = [.22, 1.44], p = .008). Therefore, we found evidence to support H1. We hypothesized that the digital manipulation recognition has a negative impact on SMI’s authenticity (H4). The recognition of the use of digitally manipulated pictures had no direct impact on the perceived authenticity of the SMI (b = .009, SE = .06, 95% CI = [−0.11, .13], p = .87), hence H4 was not supported. Furthermore, the digital manipulation disclosure has no significant direct impact on the perceived authenticity of the SMI (b = −0.09, SE = .19, 95% CI = [−0.46, .28], p = .64). We posited that the perceived authenticity of the SMI has a positive impact on (a) the intention toward the SMI (H7a), brand attitude (H7b), and eWOM (H7c). Our findings showed that the perceived authenticity of the SMI has a significant positive impact on the intention toward the SMI (b = .39, SE = .12, 95% CI = [.16, .63], p < .001), brand attitude (b = .53, SE = .15, 95% CI = [.23, .83], p < .001), and eWOM (b = .37, SE = .11, 95% CI = [.14, .60], p < .001). Thus, results are in favor of H7a, H7b, and H7c. Moreover, the digital manipulation disclosure has no significant direct impact on the intention toward the SMI (b = −0.23, SE = .21, 95% CI = [−0.69, .19], p = .29), brand attitude (b = −0.21, SE = .27, 95% CI = [−0.76, .33], p = .44), and eWOM (b = −0.34, SE = .21, 95% CI = [−0.75, .08], p = .32). Coefficients of direct effects are shown in .

Figure 2. Coefficients of serial mediation Study 1. Notes: N = 99; Unstandardized effects are presented N = 99;**p < .01, ***p < .001.

Placing the disclosure directly on the pictures of the branded posts contributed to digital manipulation recognition. However, the recognition of digital manipulation did not yield the anticipated impact on SMI’s authenticity. Moreover, as shown in where the results of hypotheses testing are presented, there is no indirect effect of the digital manipulation disclosures on the SMI and on brand-related outcomes.

Table 3. Hypotheses testing Study 1.

Study 2

Method

In the second study, our objective was to evaluate the effects of SMIs’ advertising posts, specifically comparing those containing unretouched images to digitally retouched ones, both with and without a disclosure. To achieve this, we digitally altered the pictures we had captured to employ them as experimental stimuli, and we included a visual disclosure as a stamp to them. We decided to test the impact of digitally enhanced pictures in SMI advertising for skincare products, considering the importance for consumers of a genuine depiction of how skin care products work. Moreover, in this study, we explored the moderating role of product involvement in the relationship between recognizing digital manipulation and the perceived credibility of the SMI.

Participants

Initially, we recruited 177 female participants from the United Kingdom (UK), via the crowdsourcing platform Prolific, and randomly assigned them to one of the three conditions. Given the relevance of the ongoing public discussion in this country regarding the introduction of a mandatory disclosure for digitally manipulated pictures on SMI advertising posts, we conducted the study with British participants. Fluency in English and having an active Instagram account were prerequisites, and participants were compensated with ∼5 USD for their involvement. We opted for a female sample because our stimulus materials featured a fictitious female SMI. Previous research stressed the relevance of matching the SMI’s gender with the gender of participants to avoid confounding effects (De Jans et al. Citation2020; De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). Furthermore, women perceived higher levels of similarity with a female SMI than men, and same-gender endorsement positively affects persuasion (Hudders and De Jans Citation2022).

Stimulus materials and study design

Participants across the three groups were instructed to view the SMI account information on their smartphones. The SMI was showcased as a lifestyle digital content creator. Following this, they were shown a total of six Instagram posts, comprising three branded posts promoting skincare products from the CeraVe brand and three organic posts that did not feature any brands. The branded posts included photos showcasing the SMI endorsing skin care products as close-up shots focusing on the SMI’s face, while the other three pictures included in the organic posts showed the SMI from a distance. We included pictures of a fictitious female SMI (41,000 followers) in our stimulus material after closely examining similar posts from genuine SMIs promoting skincare products, thus enhancing the external validity of our experiment. The stimulus materials are shown in Appendix B. illustrates an example of a branded post without digital manipulation, a branded post featuring a digitally manipulated image without disclosure, and one with a disclosure included.

Similar to previous studies (McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021), a manipulation check was performed by asking participants to answer the following question: ‘Did any of the Instagram posts contain one of the following statements or a similar statement?’ Participants were required to select one out of four possible answers. For the third group the correct statement was ‘The person in the photos has been retouched’, while for the other groups, the correct choice was ‘none of the above’. Five participants from each of the two groups failed to indicate the correct answer. In the third group, which viewed digitally manipulated branded pictures with a disclosure, n = 49 (∼80%) participants indicated that they saw the message about the retouched person in the posts. Therefore, the manipulation check was successful [χ2(1) = 92.5, p < .001, Φ = .72]. We eliminated a total number of 22 cases from the original sample and we considered for the analysis a sample of N = 155 participants aged 19–36 years (M = 28.81, SD = 4.56).

The differences between the three groups consist of the absence vs. the presence of digitally manipulated pictures with or without a disclosure in the branded posts. Hence, the first group (n1 = 52) viewed branded posts that featured unaltered pictures of the SMI. The second group (n2 = 54) saw identical branded posts but with digitally manipulated images. The third group (n3 = 49) viewed branded posts with digitally manipulated images, accompanied by a digital manipulation disclosure. Like in Study 1, the disclosure was placed directly on the pictures as a stamp with the wording ‘retouched person’.

Considering existing legislation in the UK that requires mandatory disclosure of SMI advertising, the paid partnership was disclosed for all conditions in the standardized disclosure form used on Instagram. ‘Paid partnership’ placed above each of the branded posts. Thus, similar to Study 1, the advertising disclosure was not considered a factor and was shown in the stimulus materials for all groups.

The survey was distributed as a Qualtrics link and included three parts. After the informed consent, in the first part, participants answered socio-demographic questions. They rated their Instagram usage, satisfaction with their physical appearance, how often they digitally manipulated their pictures, and how important skin care products were to them. In the second part, we instructed the participants to view the stimulus material in the same manner as they typically engage with social media influencers’ posts. Moving on to the third part, we requested participants to provide ratings for our moderators and dependent variables. Similar to Study 1, at the end of the survey, we included a disclaimer aimed at increasing awareness of the potential drawbacks associated with viewing digitally enhanced pictures.

Pre-test

We chose a fictitious SMI and used pictures of her that we took for this study, thereby enhancing the internal validity of our study. Aligned with practices commonly observed among social media influencers on platforms like Instagram, we employed Adobe Photoshop 24.1 to retouch the SMI’s appearance. This involved the removal of skin imperfections and selective enhancements of specific features of the SMI’s physical appearance.

Before conducting our experiment, we ran a pre-test involving three groups of 20 female Instagram users each, totaling N = 60 participants. Participants assessed the SMI-branded posts, which included pictures that were unaltered, compared to digitally manipulated pictures with and without a disclosure. They were asked to rate the extent of digital manipulation in these Instagram posts on a scale from 1, ‘not at all manipulated’ to 7, ‘strongly manipulated.’ The results indicated that posts with unaltered pictures received a lower average rating, M = 1.7, whereas digitally manipulated pictures without disclosure received an average rating of M = 3.35, and those containing a disclosure scored the highest, M = 5.8. These findings confirmed that participants accurately perceived the level of image manipulation as intended for our study’s stimuli. Therefore, we proceeded to use these materials in the study.

Measures

The first mediator, namely digital manipulation recognition, was measured with a single question using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’; M = 4.10, SD = 1.31). The second mediator, the perceived credibility of the SMI was rated by participants also on a 7-point Likert scale using eight questions (‘The influencer is attractive/good looking/sincere/honest/trustworthy/competent/professional/experienced’ from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’ (α = .87, M = 4.65, SD = .77; Ohanian Citation1990; Russell and Rasolofoarison Citation2017).

Our dependent variables, the Intention toward the SMI (α = .98, M = 2.94, SD = 1.62; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015), brand attitude (α = .89, M = 5.16, SD = 1.01; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016), and eWOM (α = .94, M = 2.19, SD = 1.46; Sohn Citation2009; Evans et al. Citation2017) were measured with the same instruments as in Study 1.

Furthermore, participants rated how critical skin care was to them, measured as product involvement, considered as a moderator with five questions on a 7-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘Skin care plays an important role in my daily life’; from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’; α = .95, M = 5.20, SD = 1.44; Choo et al. Citation2014).

Moreover, participants’ body appreciation (α = .91, M = 3.18, SD = .78; Slater, Varsani, and Diedrichs Citation2017) was also measured in the same way as for Study 1. Advertising recognition was measured with one question on a 7-point Likert scale: ‘Did you notice advertising while watching the Instagram posts?’ (M = 6.66, SD = .89; De Jans et al. Citation2020). Finally, participants’ familiarity with the brand CeraVe shown in our stimulus materials was rated with a yes or no question.

Results

As randomization checks, we run a series of one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests to ensure that outcome differences between groups result from our stimuli and not from other variables we controlled for. Thus, age [F (2) = .49, p = .61], and participants’ body appreciation [F (2) = .35, p = .71] were successful. More than 89% (n = 138) of the participants were familiar with the brand CeraVe. However, familiarity with the brand was not significantly different among conditions [χ2(2) = 7.51, p = .06].

Descriptive statistics per condition are shown in . A series of one-way ANOVA were conducted for the mediators and dependent variables. Results showed significant differences between conditions regarding the recognition of the digital manipulation [F(2,155) = 24.48, p < .001] and brand attitude [F(2,155) = 3.12, p = .04]. There are no significant differences regarding the perceived SMI’s credibility [F(2,155) = .73, p = .48], intention towards the SMI [F(2,155) = .002, p = .99], and eWOM [F(2,155) = 2.08, p = .12].

Table 4. Descriptive analysis and the results of the one-way ANOVA tests Study 2.

Our dependent variables, as well as SMI’s perceived credibility, positively correlated. Digital manipulation recognition negatively correlates with the perceived credibility of the SMI. Advertising recognition positively correlates with digital manipulation recognition (r = .23, p = .03) and there are no differences between conditions concerning the recognition of advertising [F(2) = 2.33, p = .10, ηp2 = .30]. The results of the bivariate correlations are shown in .

Table 5. Bivariate correlations Study 2.

We posited that using a digital manipulation disclosure will contribute to digital manipulation recognition (H1). We performed an ANOVA test with the experimental conditions as the fix factor and digital manipulation recognition as a dependent variable. We observed a significant effect of the digital manipulation [F(2) = 24.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .26]. The Bonferroni post hoc test showed that digital manipulation recognition is significantly different in our three conditions, the participants in the group that saw branded posts with digitally manipulated pictures scored higher (M = 4.81, SD = 1.21) in recognizing the digital manipulation compared to participants in the group that saw the post with no digital manipulation (M = 3.85, SD = 1.42, p < .001). Moreover, the participants who saw the posts containing digitally manipulated pictures with a disclosure (M = 5.88, SD = 1.39) had significantly higher recognition values than those in the first and second group (p < .001). Hence, our findings support H1.

We posited that disclosing digital manipulation has a positive effect on the SMI’s perceived credibility (H2). To test the second hypothesis, we performed an ANOVA test with the experimental conditions as the fix factor and the SMI’s perceived credibility as a dependent variable. We observed no significant effect of the digital manipulation disclosure [F(2) = .73, p = .48, ηp2 = .01]. Hence, we found no evidence to support H2.

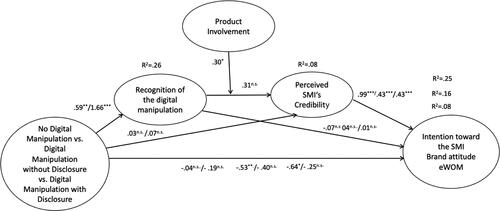

To test the proposed hypothesized model of serial moderated mediation regarding digital manipulation recognition via SMI’s credibility on the intention toward the SMI, brand attitude, and eWOM as dependent variables, we applied Model 91, PROCESS macro 3 in SPSS (Hayes Citation2022), employing 5000 bootstrap samples. Our dependent variable is multicategorical, and the group exposed to the unretouched images was used as a reference group. Product involvement was considered as a moderator. We applied separate analyses for each dependent variable.

Our analysis showed that digital manipulation recognition is higher in the disclosure condition (b = 1.66, SE = .24, 95% CI = [1.17, 2.12], p < .001) and in the no disclosure condition (b = .59, SE = .24, 95% CI = [.12, 1.06], p = .01) compared to the condition without a digital manipulation.

We posited that recognizing the digital manipulation of pictures will negatively affect the SMI’s perceived credibility (H3). Our analysis showed that recognizing digital manipulation has no significant direct effect on SMI’s credibility (b = .31, SE = .19, 95% CI = [−0.07, .69], p = .11). Thus, H3 was not supported.

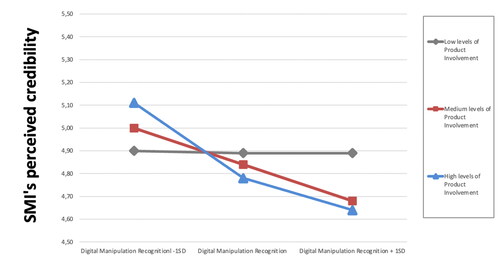

We posited that product involvement will have a moderating role in the relationship between the recognition of digital manipulation and the perceived credibility of the SMI (H5). Findings showed that product involvement positively affects SMI’s perceived credibility (b = .30, SE = .14, 95% CI = [.02, .58], p = .03). The interaction between the recognition of the digital manipulation and credibility (b = −0.08, SE = .03, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.02], p = .02) had a negative significant effect on SMI’s credibility. Hence, our mediation hypothesis (H5) was confirmed. Our findings indicate the following: at low levels of product involvement = 3.73 (Effect = −0.002, SE = .08, 95% BootCI = [−0.16, .15], p = .98), at medium levels of product involvement = 5.19 (Effect = −0.12, SE = .06, 95% BootCI = [−0.24, −0.009], p = .03), and at high levels of product involvement = 6.65 (Effect = −0.24, SE = .07, 95% BootCI = [−0.39, −0.09], p = .001). Interaction effects are depicted in .

Figure 4. Interaction effects of the recognition of the digital manipulation moderated by product involvement on the SMI’s perceived credibility.

We posited that the SMI’s perceived credibility will have a positive effect on the intention toward the SMI (H6a), brand attitude (H6b), and eWOM (H6c). The analysis showed that the SMI’s perceived credibility positively affects the intention toward the brand (b = .99, SE = .15, 95% CI = [.69, 1.29], p < .001), brand attitude (b = .43, SE = .10, 95% CI = [.23, .63], p < .001), and eWOM (b = .43, SE = .15, 95% CI = [.12, .73], p = .006). Thus, H6a, H6b, and H6c were supported. In the case of the intention toward the influencer as the dependent variable, the index of the moderated mediation is significant for the digitally manipulated pictures with no disclosure (Index = −0.05 BootSE = . 03, BootCI [−0.11, −0.005]), and with disclosure conditions (Index = −0.14, BootSE = . 06, BootCI [−0.26, −0.03]). In the case of brand attitude as the dependent variable, the index of the moderated mediation is significant for the digitally manipulated pictures with no disclosure (Index = −0.02, BootSE = . 01, BootCI [−0.06, −0.01]), and with disclosure conditions (Index = −0.06, BootSE = . 03, BootCI [−0.12, −0.01]). Finally, also in the case of eWOM as the dependent variable, the index of the moderated mediation is significant for the digitally manipulated pictures with no disclosure (Index = −0.02, BootSE = . 02, BootCI [−0.06, −0.0004]), and with disclosure conditions (Index = −0.06, BootSE = .04, BootCI [−0.14, −0.005]). shows hypotheses testing for Study 2. The coefficients of direct effects are shown in .

Figure 5. Coefficients of serial mediation Study2. Notes: N = 155; Unstandardized effects are presented N = 99; *p < .05, **p < .01, **p < .001.

Table 6. Hypotheses testing study.

Discussion

The main objective of our research was to explore the effectiveness of disclosing digitally enhanced pictures on SMIs’ branded posts. The discussion on the effectiveness of digital disclosures begins with participants’ ability to recall having seen the disclosure. Our studies have revealed that social media users face challenges in remembering encounters with digital disclosures. It is worth emphasizing that in Study 1, even though the disclosure was visibly integrated as a stamp on the branded posts with the wording ‘retouched person’, only approximately half of the participants were able to remember encountering the disclosure. This underscores the issue of recall and recognition surrounding digital disclosures used on social media. Even though the topic of mandatory disclosures for digitally enhanced pictures on SMI’s branded posts has been a subject for public debate in Germany, the country where Study 1 was conducted, such measures have not yet been implemented. Consequently, consumers are not as familiar with these types of disclosures as they are with advertising disclosures, which could explain why they struggle to remember encountering them.

Moreover, according to eye-tracking studies investigating sponsored news articles, significant proportions of users do not even look at sponsorship disclosures. Among those who do, only a fraction accurately identify that the disclosure denotes the content they are viewing as a paid message (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016; Wojdynski et al. Citation2017). Despite the general acknowledgment of image editing and the likelihood that many advertising images have been digitally altered (Harrison and Hefner Citation2014), our findings indicate that the ability to detect photo manipulation solely through visual inspection is somewhat limited. Additionally, users are not accustomed to these types of disclosures as they are with advertising disclosures and do not remember seeing them.

Furthermore, if the disclosure was noticed it contributed to the recognition of digital manipulation. However, the disclosure had no significant direct or indirect impact on the perceived authenticity of the SMI nor on the SMI and brand-related outcomes. The subjective character of authenticity and social media culture’s evolving standards and ideals may explain these findings. On social media, digital manipulation has spread, with many users viewing it as a creative tool to express themselves and improve the visual attractiveness of their content. Social media users may perceive a SMI who uses digital manipulation as authentic because the altered images showcase the person’s unique aesthetic tastes and vision (Balaban and Szambolics Citation2022). Furthermore, social media users could place more value on aesthetics than strict adherence to unaltered reality, leading them to believe that digitally altered photographs accurately portray the SMI’s online persona.

We know from traditional media literacy literature that although users may be aware of certain negative aspects stemming from media content, such media content might still instinctively be appealing to them (Schreurs and Vandenbosch Citation2021). The findings indicating that an SMI is perceived as authentic, despite digitally altering her appearance and disclosing this, suggests that image processing is deeply ingrained in the consciousness of users, and it is not perceived as artificial or unrealistic.

Study 2 was conducted on UK female participants and the SMI endorsed skincare products. The disclosure in the form of a ‘retouched person’ stamp placed on the enhanced images, in accordance with the Norwegian legislation, was recalled by a higher percentage of participants than in the first study. This can be a result of a more prominent discussion on disclosing digital enhancements in the UK than in Germany, where Study 1 was conducted. However, we found evidence in both studies that disclosing digitally enhanced pictures in SMIs’ branded posts contribute to the recognition of the digital manipulation for the participants who remembered the wording of the disclosure. Therefore, visual disclosures of digitally manipulated branded SMIs’ posts are effective to a certain extent when noticed. Hence, our results contradict previous research on this topic (McComb, Gobin, and Mills Citation2021; Naderer, Peter, and Karsay Citation2021).

In Study 2, the high mean values for recognizing digital manipulation were also observed in the group where the pictures were not retouched. Although we carefully selected our stimulus materials and pre-tested the pictures. We included posts that showcased close-up images of the SMI with visible skin imperfections in the condition without digital manipulation and without a disclosure. Nevertheless, participants still assessed these pictures as digitally manipulated. These findings can be interpreted as an indication that social media users often believe that SMIs, in their role as advertising figures, commonly engage in the manipulation of their pictures.

In Study 2, we observed that both disclosing digital manipulation and recognizing digital manipulation do not directly impact SMI’s perceived credibility. However, we found evidence that product involvement has a moderating role in the relationship between recognizing digitally manipulated SMIs’ branded posts and the perceived credibility of the SMI. This finding is the main takeaway of the present research. SMIs are perceived as experts who usually create and post content on social media in a particular area of interest for the audiences (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). Previous literature has shown that topic interest plays a crucial role when choosing to engage with an SMI’s generated content (Coco and Eckert Citation2020). Our results showed that social media users with high product involvement perceived the influencer as more credible. However, when users recognize digital alteration and experience high product involvement, the perceived credibility of the SMIs decreases. Previous research stressed that the awareness of the falsity of advertising manipulation negatively affects advertising outcomes (Campbell et al. Citation2022). Our findings showed that product involvement is a boundary condition to the negative SMI and brand-related advertising outcomes.

Our research confirmed the positive effects of SMI’s perceived credibility (Ki and Kim Citation2019; Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Munnukka, Uusitalo, and Toivonen Citation2016) and authenticity (Lee and Eastin Citation2021; SOURCE 1) on SMI and brand-related advertising outcomes. Thus, SMIs that are perceived as trustworthy and authentic are worthy of being followed. Furthermore, as users who perceive SMIs as authentic engage in eWOM, their persuasive power will grow.

Overall, our research contributes to a better understanding of the mechanism behind the effectiveness of disclosures used for digitally enhanced pictures. Additionally, we evaluate the impact of such disclosures on a cognitive pathway that encompasses the recognition of the disclosure itself and the perceived credibility and authenticity of SMIs.

Limitations and future research

It is essential to consider the findings of the present studies while acknowledging several limitations. First, both studies are single-exposure studies. Therefore, a possible limit is the brief exposure to disclaimer labels affixed to advertisements within one brief session. Moreover, we did not control for the time our participants spent watching the stimulus materials. Future research should consider repeated exposure to disclaimer labels over different sessions and the use of eye-tracking devices. Given that consumers are increasingly adept at seeing and possibly tolerating manipulated advertisements as their exposure to them increases (Campbell et al. Citation2022), longitudinal studies are needed.

Second, in our studies, we used well-known brands, such as Adidas as stimulus material for the first study, and CeraVe for the second study. Thus, preexisting attitudes towards the brands Adidas and CeraVe might have interfered with the objective assessment of the endorser, advertisement, and intentions. To further enhance the study’s scope, future research could explore the use of different brands not familiar to participants as stimulus material and examine how photo manipulation may impact consumer perceptions and attitudes towards them and the advertising agent.

Given that disclosing advertising is a mandatory practice in the countries where we conducted our research, we included an advertising disclosure on all SMI’s advertising posts. Looking at the interaction between sponsorship disclosure and digital manipulation disclosure could contribute to refining ethical standards in influencer marketing, ensuring that both forms of transparency effectively serve their intended purposes. As social media users are accustomed with advertising disclosures, research (Giuffredi-Kähr, Petrova, and Malär Citation2022; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023) showed that sponsorship transparency is not only appreciated but also contributes to positive advertising outcomes. Future research perspectives should investigate the effects associated with transparency concerning digital manipulation disclosures.

Third, while our first study was conducted on a sample including both males and females, the second study was conducted on an exclusively female sample. Therefore, the findings need to be interpreted under this limitation. Future studies must consider gender diverse samples.

Fourth, in the case of the branded posts that were digitally manipulated, surroundings might have influenced the results of our studies. Investigating the effects of the presence vs. the absence of surroundings in digitally manipulated pictures is a factor to be considered for future research.

Fifth, the participants originate from Germany and the UK, countries where public discussion regarding the mandatory disclosure of digitally enhanced images is ongoing, and therefore, they were not yet familiar with this practice. There is a need for future research to be conducted in countries where such disclosures are mandatory.

Sixth, the current research focuses on users’ perspectives. However, studying SMI’s views on ethical practices and transparency through photo edit disclosures in sponsored content should be a compelling opportunity for scholars to shape this emerging field.

Implications

Our research carries both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, these studies offer insights into the effectiveness of disclosures designed to signal the presence of retouched content in SMI posts. Both our studies showed that if noticed, a visually prevalent clearly worded label placed directly on the branded posts significantly contributes to the recognition of digital enhancement. Besides, our findings contribute to a better understanding of how digital manipulation disclosures on SMI’s branded posts relate to the perceived credibility and authenticity of SMIs. Hence, while the perceived authenticity of the SMI is not affected by the recognition of the digital manipulation disclosure, the SMI’s perceived credibility is affected in a negative way only in the case of high levels of product involvement.

This contributes to the broader digital manipulation framework (Campbell et al. Citation2022) and adds depth to the source credibility literature in the context of influencer marketing. Furthermore, our research contributes to the discussion surrounding digital manipulation disclosures within the framework of the PKM model by identifying a nuanced mechanism of conditional effects. When examining digital manipulation disclosures akin to how previous studies have analyzed advertising disclosures, we were not able to identify two paths, the positive impact of transparency and the negative effects of PK (Giuffredi-Kähr, Petrova, and Malär Citation2022; Karagür et al. Citation2022; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2023). Thus, contrary to our expectations, we did not find any positive impact from transparently disclosing digital manipulation. Moreover, we highlighted that recognizing digital manipulation has a negative impact on the perceived credibility of SMIs, under the conditional effect of product involvement.

Our findings carry significance for policymakers, marketers, and SMIs. Despite our research revealing the limited effectiveness of disclosures, we recommend that SMIs incorporate them into their practices. Our research underscores the dual role of photo edit disclosures as a sign of transparency. We argue that these disclosures serve as a positive step toward openness in content creation, providing audiences with a clearer understanding of the editing process involved.

Moreover, policymakers should reevaluate the effectiveness of the specific disclosures examined in regulating digitally manipulated photos in SMIs’ posts and prioritize the development of more comprehensive disclosure strategies. For marketers and SMIs, our results demonstrate that transparency does indeed yield benefits for influencers, as it contributes to maintaining the perceived credibility and authenticity of their followers, as these factors play a pivotal role in influencing advertising outcomes.

APPENDIX 2.docx

Download MS Word (8.5 MB)APPENDIX 1.docx

Download MS Word (3.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The fictitious ads and the datasets in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abendroth, L.J., and J.E. Heyman. 2013. Honesty is the best policy: The effects of disclosure in word-of-mouth marketing. Journal of Marketing Communications 19, no. 4: 245–57.

- Abidin, C., and M. Ots. 2016. Influencers tell all? Unravelling authenticity and credibility in a brand scandal. In Blurring the lines: Market-driven and democracy-driven freedom of expression, ed. M. Edström, A.T. Kenyon, and E.-M. Svensson, 153–61. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Audrezet, A., G. de Kerviler, and J.G. Moulard. 2020. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research 117: 557–69.

- Balaban, D., and M. Mustățea. 2019. Users’ perspective on the credibility of social media influencers in Romania and Germany. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations 21, no. 1: 31–46.

- Balaban, D.C., and J. Szambolics. 2022. A proposed model of self-perceived authenticity of social media influencers. Media and Communication 10, no. 1: 235–46.

- Balaban, D.C., J. Szambolics, and M. Chirică. 2022. Parasocial relations and social media influencers’ persuasive power. Exploring the moderating role of product involvement. Acta Psychologica 230: 103731.

- Balaban, D.C., M. Mucundorfeanu, and L.I. Mureșan. 2022. Adolescents’ understanding of the model of sponsored content of social media influencer instagram stories. Media and Communication 10, no. 1: 305–16.

- Boerman, S.C. 2020. The effects of the standardized instagram disclosure for micro- and meso-influencers. Computers in Human Behavior 103: 199–207.

- Boerman, S.C., and E.A. van Reijmersdal. 2019. Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: The moderating role of Para-social relationship. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3042.

- Boerman, S.C., E. Rozendaal, and E.A. van Reijmersdal. 2023. The development and testing of a pictogram signaling advertising in online videos. International Journal of Advertising 43, no. 4: 672–91.

- Boerman, S.C., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and E. Rozendaal. 2023. Can an awareness campaign boost the effectiveness of influencer marketing disclosures in YouTube videos? Media and Communication 11, no. 4: 140–50.

- Boerman, S.C., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and P.C. Neijens. 2012. Sponsorship disclosure: Effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and brand responses: Sponsorship disclosure. Journal of Communication 62, no. 6: 1047–64.

- Boerman, S.C., E.A. van Reijmersdal, E. Rozendaal, and A.L. Dima. 2018. Development of the persuasion knowledge scales of sponsored content (PKS-SC). International Journal of Advertising 37, no. 5: 671–97.

- Brown, Z., and M. Tiggemann. 2020. A picture is worth a thousand words: The effect of viewing celebrity instagram images with disclaimer and body positive captions on women’s body image. Body Image 33: 190–8.

- Campbell, C., and J.R. Farrell. 2020. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons 63, no. 4: 469–79.

- Campbell, C., and P.E. Grimm. 2019. The challenges native advertising poses: Exploring potential federal trade commission responses and identifying research needs. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 38, no. 1: 110–23.

- Campbell, C., K. Plangger, S. Sands, and J. Kietzmann. 2022. Preparing for an era of deepfakes and AI-generated ads: A framework for understanding responses to manipulated advertising. Journal of Advertising 51, no. 1: 22–38.

- Celsi, R.L., and J.C. Olson. 1988. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research 15, no. 2: 210–24.

- Choo, H.J., S.Y. Sim, H.K. Lee, and H.B. Kim. 2014. The effect of consumers’ involvement and innovativeness on the utilization of fashion wardrobe: The utilization of fashion wardrobe. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38, no. 2: 175–82.

- Coco, S.L., and S. Eckert. 2020. #sponsored: Consumer insights on social media influencer marketing. Public Relations Inquiry 9, no. 2: 177–94.

- Colliander, J., and S. Erlandsson. 2015. The blog and the bountiful: Exploring the effects of disguised product placement on blogs that are revealed by a third party. Journal of Marketing Communication 21, no. 2: 313–20.

- Coutoure, B.A.C., and K. Harrison. 2020. Visual and cognitive processing of thin-ideal instagram images containing idealized or disclaimer comments. Body Image 33: 152–63.

- Daldorph, B. 2017. New French law says airbrushed or Photoshopped images must be labeled. France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/20170930-france-fashion-photoshop-lawmodels-skinny (accessed April 10, 2023).

- De Jans, S., D. Van de Sompel, M. De Veirman, and L. Hudders. 2020. #Sponsored! How the recognition of sponsoring on instagram posts affects adolescents’ brand evaluations through source evaluations. Computers in Human Behavior 109: 106342.

- De Veirman, M., V. Cauberghe, and L. Hudders. 2017. Marketing through instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 36, no. 5: 798–828.

- Djafarova, E., and C. Rushworth. 2017. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior 68: 1–7.

- Eisend, M., and F. Tarrahi. 2016. The effectiveness of advertising: A meta-meta-analysis of advertising inputs and outcomes. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 4: 519–31.

- Eisend, M., E.A. van Reijmersdal, S.C. Boerman, and F. Tarrahi. 2020. A meta analysis of the effects of disclosing sponsored content. Journal of Advertising 49, no. 3: 344–66.

- Enke, N., and N.S. Borchers. 2019. Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13, no. 4: 261–77.

- Evans, N.J., B.W. Wojdynski, and M.G. Hoy. 2019. How sponsorship transparency mitigates negative effects of advertising recognition. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 3: 364–82.

- Evans, N.J., J. Phua, J. Lim, and H. Jun. 2017. Disclosing instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising 17, no. 2: 138–49.

- Fardouly, J., and E. Holland. 2018. Social media is not real life: The effect of attaching disclaimer-type labels to idealized social media images on women’s body image and mood. New Media & Society 20, no. 11: 4311–28.

- Fardouly, J., B.K. Willburger, and L.R. Vartanian. 2018. Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society 20, no. 4: 1380–95.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 1: 1–31.

- Fritz, K., V. Schoenmueller, and M. Bruhn. 2017. Authenticity in branding—exploring antecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. European Journal of Marketing 51, no. 2: 324–48.

- Gioia, F., S. McLean, M.D. Griffiths, M.D., and V. Boursier. 2021. Adolescents’ selfie-taking and selfie-editing: A revision of the photo manipulation scale and a moderated mediation model. Current Psychology 42, no. 5: 3460–76.

- Giuffredi-Kähr, A., A. Petrova, and L. Malär. 2022. Sponsorship disclosure of influencers – A curse or a blessing? Journal of Interactive Marketing 57, no. 1: 18–34.

- Gray, J. 2021. Norway passes a law requiring influencers to label retouched photos on social media. Digital Photography Review. https://www.dpreview.com/news/1157704583/norway-passes-law-requiring-influencers-to-label-retouched-photos-on-social-media

- Grigsby, J.L. 2020. Fake ads: The influence of counterfeit native ads on brands and consumers. Journal of Promotion Management 26, no. 4: 569–92.

- Harmon, J., and N.A. Rudd. 2016. Breaking the illusion: The effects of adding warning labels identifying digital enhancement on fashion magazine advertisements. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 3, no. 3: 357–74.

- Harrison, K., and V. Hefner. 2014. Virtually perfect: Image retouching and adolescent body image. Media Psychology 17, no. 2: 134–53.

- Hayes, A.F. 2022. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Hovland, C.I., and W. Weiss. 1951. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly 15, no. 4: 635–50.

- Hudders, L., and S. De Jans. 2022. Gender effects in influencer marketing: An experimental study on the efficacy of endorsements by same- vs. other-gender social media influencers on instagram. International Journal of Advertising 41, no. 1: 128–49.

- Hudders, L., S. De Jans, and M. De Veirman. 2021. The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising 40, no. 3: 327–75.

- Hund, E. 2017. Measured beauty: Exploring the aesthetics of instagram’s fashion influencers. #SMSociety17: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society, vol. 44, 1–5.

- Hwang, Y., and S.-H. Jeong. 2016. This is a sponsored blog post, but all opinions are my own: The effects of sponsorship disclosure on responses to sponsored blog posts. Computers in Human Behavior 62: 528–35.

- Jin, S.V. 2018. Celebrity 2.0 and beyond! Effects of facebook profile sources on social networking advertising. Computers in Human Behavior 79: 154–68.

- Karagür, Z., J.-M. Becker, K. Klein, and A. Edeling. 2022. How, why, and when disclosure type matters for influencer marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing 39, no. 2: 313–35.

- Ki, C.-W., and Y.-K. Kim. 2019. The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing 36, no. 10: 905–22.

- Ki, C.W., L.M. Cuevas, S.M. Chong, and H. Lim. 2020. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 55: 102133.

- Kowalczyk, C.M., and K.R. Pounders. 2016. Transforming celebrities through social media: The role of authenticity and emotional attachment. Journal of Product & Brand Management 25, no. 4: 345–56.

- Krugman, H.E. 1966. The measurement of advertising involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly 30, no. 4: 583–96.

- Kühn, J., and C. Riesmeyer. 2021. Brand endorsers with role model function: Social media influencers’ self-perception and advertising literacy. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung 43: 67–96.

- Kwan, M.Y., A.F. Haynos, K.K. Blomquist, and C.A. Roberto. 2018. Warning labels on fashion images: Short‐ and longer‐term effects on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms, and eating behavior. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 51, no. 10: 1153–61.

- Lee, J.A., and M.S. Eastin. 2021. Perceived authenticity of social media influencers: Scale development and validation. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 15, no. 4: 822–41.

- Liljander, V., J. Gummerus, and M. Söderlund. 2015. Young consumers’ responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research 25, no. 4: 610–32.

- Livingston, J., E. Holland, and J. Fardouly. 2020. Exposing digital posing: The effect of social media self-disclaimer captions on women’s body dissatisfaction, mood, and impressions of the user. Body Image 32: 150–4.

- Lou, C., and S. Yuan. 2019. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising 19, no. 1: 58–73.

- Matthes, J., and B. Naderer. 2016. Product placement disclosures: Exploring the moderating effect of placement frequency on brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 185–99.

- McComb, S.E., K.C. Gobin, and J.S. Mills. 2021. The effects of self-disclaimer instagram captions on young women’s mood and body image: The moderating effect of participants’ own photo manipulation practices. Body Image 38: 251–61.

- Metzger, M.J., and A.J. Flanagin. 2015. Psychological approaches to credibility assessment online. In The handbook of the psychology of communication technology, ed. S.S. Sundar, 445–66. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

- Munnukka, J., O. Uusitalo, and H. Toivonen. 2016. Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Marketing 33, no. 3: 182–92.

- Naderer, B., C. Peter, and K. Karsay. 2021. This picture does not portray reality: Developing and testing a disclaimer for digitally enhanced pictures on social media appropriate for Austrian tweens and teens. Journal of Children and Media 16, no. 2: 149–67.

- Nafees, L., C.M. Cook, N.K. Atanas, and J.E. Stoddard. 2021. Can social media influencer (SMI) power influence consumer brand attitudes? The mediating role of perceived SMI credibility. Digital Business 1, no. 2: 100008.

- O’Cass, A. 2000. An assessment of consumers product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. Journal of Economic Psychology 21, no. 5: 545–76.

- Ohanian, R. 1990. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising 19, no. 3: 39–52.

- Palan, S., and C. Schitter. 2018. Prolific.ac – A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 17: 22–7.

- Pöyry, E.I., M. Pelkonen, E. Naumanen, and S.M. Laaksonen. 2019. A call for authenticity: Audience responses to social media influencer endorsements in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13, no. 4: 336–51.

- Rozendaal, E., M.A. Lapierre, E.A. van Reijmersdal, and M. Buijzen. 2011. Reconsidering advertising literacy as a defense against advertising effects. Media Psychology 14, no. 4: 333–54.

- Russell, C.A., and D. Rasolofoarison. 2017. Uncovering the power of natural endorsements: A comparison with celebrity-endorsed advertising and product placements. International Journal of Advertising 36, no. 5: 761–78.

- Schallehn, M., C. Burmann, and N. Riley. 2014. Brand authenticity: Model development and empirical testing. Journal of Product & Brand Management 23, no. 3: 192–9.

- Schreurs, L., and L. Vandenbosch. 2021. Introducing the social media literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. Journal of Children and Media 15, no. 3: 320–37.

- Slater, A., N. Varsani, and P.C. Diedrichs. 2017. #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image 22: 87–96.

- Sohn, D. 2009. Disentangling the effects of social network density on electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) intention. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, no. 2: 352–67.

- Tiggemann, M. 2022. Digital modification and body image on social media: Disclaimer labels, captions, hashtags, and comments. Body Image 41: 172–80.

- Tiggemann, M., and I. Anderberg. 2020. Social media is not real: The effect of ‘instagram vs reality’ images on women’s social comparison and body image. New Media & Society 22, no. 12: 2183–99.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., and S. van Dam. 2020. How age and disclosures of sponsored influencer videos affect adolescents’ knowledge of persuasion and persuasion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 49, no. 7: 1531–44.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., E. Brussee, N. Evans, and B.W. Wojdynski. 2023. Disclosure-driven recognition of native advertising: A test of two competing mechanisms. Journal of Interactive Advertising 23, no. 2: 85–97.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., M.L. Fransen, G. van Noort, S.J. Opree, L. Vandeberg, S. Reusch, F. van Lieshout, and S.C. Boerman. 2016. Effects of disclosing sponsored content in blogs: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion. The American Behavioral Scientist 60, no. 12: 1458–74.

- Vendemia, M.A., and D.C. De Andrea. 2018. The effects of viewing thin sexualized selfies on instagram: Investigating the role of image source and awareness of photo editing practices. Body Image 27: 118–27.

- Wojdynski, B., N.J. Evans, and M.G. Hoy. 2018. Measuring sponsorship transparency in an era of native advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs 52, no. 1: 115–37.

- Wojdynski, B.W., and N.J. Evans. 2016. Native: Effects of disclosure position and language on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 2: 157–68.

- Wojdynski, B.W., H. Bang, K. Keib, B.N. Jefferson, D. Choi, and J.L. Malson. 2017. Building a better native advertising disclosure. Journal of Interactive Advertising 17, no. 2: 150–61.

- Ye, G., L. Hudders, S. De Jans, and M. De Veirman. 2021. The value of influencer marketing for business: A bibliometric analysis and managerial implications. Journal of Advertising 50, no. 2: 160–78.