Abstract

Background – aims: The long-term survival of pancreatic cancer is poor even after potentially curative resection. The incidence of local-regional failures is high. There is evidence that hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy (HIPEC) is effective in controlling the local-regional failures. The purpose of the study is to identify the effect of HIPEC after surgical removal of pancreatic carcinoma.

Patients – Methods: Prospective study including 33 patients with resectable pancreatic carcinomas. All patients underwent surgical resection (R0) and ΗIPEC as an adjuvant. Morbidity and hospital mortality were recorded. The patients were followed-up for 5 years. Survival was calculated. Recurrences and the sites of failure were recorded.

Results: The mean age of the patients was 67.8 ± 11.1 years (38–86). The hospital mortality was 6.1% (2 patients) and the morbidity 24.2% (8 patients). The overall 5-year survival was 24%. The mean and median survival was 33 and 13 months, respectively. The median follow-up time was 11 months. The recurrence rate was 60.6% (20 patients). Three patients were recorded with local-regional failures (9.1%) and the others with liver metastases.

Conclusions: It appears that HIPEC as an adjuvant following potentially curative resection (R0) of pancreatic carcinoma may effectively control the local-regional disease. Prospective randomised studies are required.

Keywords:

Introduction

Surgical resection of pancreatic cancer is the single potentially curative treatment option [Citation1–4]. The overall 5-year survival rate is very poor and does not exceed 10–15% [Citation5–7]. Survival as high as 20–25% has been exceptionally reported from high volume centres [Citation8,Citation9].

The main problem of pancreatic cancer is the low resectability rate that does not exceed 10–15% of the diagnosed tumours [Citation1–4]. A significant number of these tumours are unresectable because they infiltrate major anatomic vessels. In addition, other locally resectable tumours present with distant and unresectable metastases at the time of initial diagnosis. Long-term survival may be increased either if the proportion of patients with locally unresectable tumours decreases or if treatments that may control recurrence are developed, and especially the local-regional ones.

The sites of recurrence after curative resection are the liver in 50–60%, the peritoneal surfaces in 40–50%, and the pancreatic bed in 50% of the cases [Citation10]. The metastatic lesions may either be the result of undetected cancer emboli on laparotomy or imaging or it may be tumour dissemination during surgical manipulations at narrow limits of resection [Citation11]. If the latter is true intraperitoneal chemotherapy may be effective by decreasing the number of local-regional recurrences. Intraperitoneally administered chemotherapy has been shown to eradicate the microscopic residual cancer emboli in diseases with peritoneal malignancy. The most characteristic of them are tumours of the gastrointestinal tract with peritoneal carcinomatosis [Citation12], pseudomyxoma peritonei [Citation13], peritoneal mesothelioma [Citation14], peritoneal sarcomatosis [Citation15], or locally advanced ovarian cancer [Citation16]. However, the beneficial effect of HIPEC in peritoneal sarcomatosis has been debated [Citation17]. In other publications the role of HIPEC in ovarian cancer does not appear to be clear [Citation18] or the role of EPIC does not seem to improve survive when used additionally to HIPEC [Citation19].

Preliminary results after potentially curative resection of pancreatic cancer in combination with HIPEC are encouraging and show that loco-regional failures may be eliminated [Citation20].

The purpose of the study is to identify the effect of HIPEC as an adjuvant after potentially curative surgery in patients with pancreatic carcinomas. The main objectives of the study are to identify (1) the overall survival and (2) the number of recurrences as well as the sites of failure. The hospital mortality and morbidity with special emphasis to toxicity of gemcitabine is the secondary objective.

Patients – methods

This is a prospective study designed in April 1999 and modified in April 2007 by excluding patients with peri-ampullary tumours who were included in the initial design. Patients with resectable pancreatic carcinomas that did not have distant metastases as assessed by routine preoperative staging (physical examination, CT-scan, MRI, and bone scanning) were included. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Hospital and patients signed an informed consent prior to accepting the treatment.

The diagnosis was possible by physical examination, haematological–biochemical examination, tumour markers (CEA, CA 19–9, and CA-125), endoscopy, CT-abdominal and thoracic scanning, or MRI, and bone scanning.

Patients between 16 and 90 years of age, with acceptable cardiopulmonary function, satisfactory renal function (blood urea level <50 mg/dl, and creatinine level <1.5 mg/dl), satisfactory liver function (other than hepatobiliary obstruction), white blood cell count >4000/ml, platelet count >150.000/ml, and acceptable performance status (Karnofsky performance status >50%) were included in the study.

Patients with evidence of distant metastatic disease (liver, osseous, brain, and pulmonary), those who had previously been treated with systemic chemotherapy, with prior malignancy at risk for recurrence (except for basal cell carcinoma or in situ carcinoma of the cervix adequately treated), with poor performance status (Karnofsky scale <50%), with psychiatric diseases or addictive disorders, and pregnant women were not included in the study.

Treatments

Patients with cancer of the head of the pancreas underwent subtotal pancreatoduodenectomy (Kausch–Whipple procedure) while those with tumours of the body or tail underwent distal (left) pancreatectomy. HIPEC was performed for 60 min at 42.5–43 °C with gemcitabine at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 after tumour resection and before the reconstruction of the alimentary tract. HIPEC was possible with the Coliseum technique (open abdominal). A heater circulator with two roller pumps, one heat exchanger, one reservoir, an extracorporeal system of two inflow and two outflow tubes, and four thermal probes was used for HIPEC (Sun Chip, Gamida Tech, Villejuif, France). A prime solution of 3 lit of Normal Saline was instilled prior to the administration of the cytostatic drug. As soon as the mean abdominal temperature exceeded 40 °C, gemcitabine was administered in the abdominal cavity.

During perfusion, adequate fluids were administered in addition to dopamine 3 μg/k. b. w, in order to maintain diuresis at 500 ml/h. Dopamine was also used for 24 h after surgery at the same dose to maintain diuresis at the same levels.

The reconstruction of the alimentary tract was always made after the completion of HIPEC. This was possible with an end-to-side pancreato-jejunal anastomosis, an end-to-side choledocho-jejunal anastomosis in continuity, and a Roux-en-Y gastro-jejunal anastomosis at 60 cm with a second jejunal loop after subtotal pancreatoduodenectomy. After distal pancreatectomy, the resection line of the remnant of the pancreas was always sutured with 3.0 silk.

All resected specimens were sent for histopathological examination and definitive staging. The intra-operative and postoperative complications were carefully recorded and treated. Stage III patients were scheduled to receive additional systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine and 5-FU.

Follow-up

All patients were followed-up at 3-month intervals for the first year and at 6-month intervals later with physical examination, haematological–biochemical examinations, tumour markers (CEA, CA 19–9, and CA-125), CT abdominal and thoracic scanning or MRI. Recurrences and the sites of recurrence were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The variables that were correlated to survival were the gender, the anatomic distribution of the tumour, the performance status, the pT, the pN, the pTNM stage, the degree of differentiation, and the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. The proportion of patients with a given characteristic was compared by chi square analysis or by Pearson’s test. Differences in the means of continuous measurement were tested by Student’s t-test. The survival curves were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox’s regression model was used for multiple analysis of survival. A two-tailed p values <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From April 2007 to April 2016, 33 patients with resectable pancreatic cancer were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 67.8 ± 11.1 years (38–86). The characteristics of the patients are listed in . Histopathology confirmed that all patients had ductal pancreatic carcinomas and complete pathologic staging was possible ().

Table 1. General characteristics of 33 patients with pancreatic cancer.

During the postoperative period (45 days), eight patients (24.2%) were recorded with complications which are listed in . One patient with postoperative bleeding was re-operated immediately and bleeding was successfully controlled. Another patient with anastomotic failure also required re-operation because of failure of the choledocho-jejunal anastomosis which was successfully controlled by T-tube insertion. The remaining two patients with anastomotic leaks were successfully treated conservatively. As a consequence, the re-operation rate was 6.1%. One patient was recorded with grade II neutropenia that did not require any specific treatment. The mean blood loss was 320 ± 200 ml (80–820). The mean operative time was 388 ± 120 min (185–592). The mean number of transfused units of FFP’s was 3 ± 2 (0–8), and the mean number of transfused blood units was 2 ± 2 (0–4).

Table 2. Postoperative complications.

The hospital mortality rate was 6.1% (two patients). One of them died because of acute respiratory distress syndrome and the other because of sepsis with an unknown primary site. The mean hospital stay was 17 ± 7 (9–45) days.

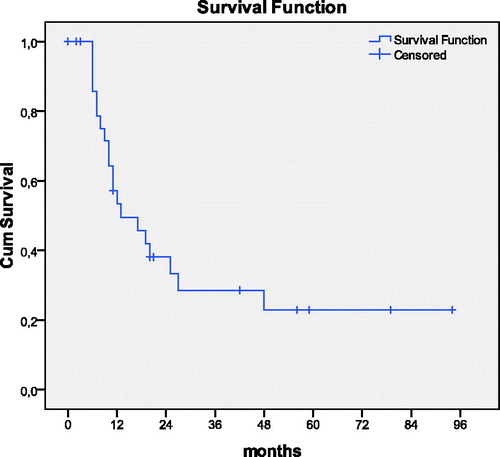

The overall 5-year survival rate was 24%. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rate was 46.7%, 37.6%, and 28%, respectively. The mean and the median survival time were 33 ± 6 and 13 months, respectively (). The degree of differentiation (p = .031) and the use of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy (p = .036) were found to be related to survival. Eighteen patients (54.5%) received additional adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine and 5-FU. The median survival of the patients that received systemic chemotherapy was 25 months and of those that did not receive was 11 months. The degree of differentiation was the single prognostic indicator of survival (HR = 5.891, p = .015, 95% CI =1.187–5.018).

Figure 1. Overall survival in 33 patients with pancreatic carcinomas undergoing R0 resection in combination with HIPEC

One patient with stage II disease and another with stage I died during the immediate postoperative period. The median disease-free survival time was 9 months. The median follow-up time was 11 months. During the follow-up, 20 patients (60.6%) were recorded with recurrence. One of them was T2N1 stage, seven were T3N0 stage, and 12 were T3N1 stage. Liver metastatic disease was recorded in 17 patients (51.5%) and local-regional metastases in 3 (9.1%). All patients with local-regional recurrences were found to be stage T3N1. Currently eight patients (24.2%) are alive without disease, 19 patients (57.6%) died due to disease recurrence, five patients (15.2%) died of other causes unrelated to cancer, and one patient (3%) is still alive with disease 3 years after initial treatment. Histopathologically the disease-free patients were T1N0 (one patient), T2N0 (two patients), T2N1 (one patient), T3N0 (one patient), and T3N1 (three patients). It is of importance to note that there are three long-term survivors (more than 5 years) without disease. One of them is stage T1N0, another is stage T3N0, and another one is stage T3N1.

Discussion

In 1985, the Gastrointestinal Study Group reported that chemoradiation offers significant survival benefit in patients with pancreatic cancer after surgical resection [Citation21]. A decade later a similar study conducted by EORTC did not confirm the same results [Citation22]. In 2004 the ESPAC prospective randomised study showed that in patients with potentially curative resection of pancreatic cancer chemotherapy only offered significant survival benefit [Citation23]. More recent publications showed that chemoradiation is effective offering significant survival benefit in patients with resectable pancreatic carcinomas [Citation24]. In Europe, in addition to surgery, the standard of care is chemotherapy with gemcitabine. In USA, chemoradiation is recommended.

Despite newly developed chemotherapeutic regimens that have shown significant increase in survival, the prognosis of pancreatic cancer still remains poor [Citation25,Citation26]. In addition, the relevant literature about adjuvant treatments in pancreatic cancer conducts to contradictory conclusions and the optimal treatment remains controversial. Unquestionably, it is likely that even radical surgery alone is not adequate to definitely treat patients with pancreatic cancer and effective adjuvant treatment is required [Citation27,Citation28].

The pathophysiology of local-regional recurrence remains unclear. It has been assumed that surgical resection of a tumour located in narrow limits results in local-regional recurrence because cancer emboli from interstitial tissue trauma, or severed lymphatics, or venous blood loss disseminate in the traumatised peritoneal surfaces of the abdominal cavity. These emboli are entrapped in fibrin, and, during wound healing, stimulated by growth factors give rise to recurrent tumours after 2–3 years following initial surgical manipulations [Citation11].

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been shown to be effective in eradicating residual cancer emboli in several abdominal and pelvic malignancies with peritoneal carcinomatosis either as hyperthermic intraoperative or as early postoperative normothermic one [Citation12–16,Citation29]. The advantage of intraperitoneallly used chemotherapy is the high drug level that can be achieved by low systemic exposure [Citation30]. As a consequence, intraperitoneal chemotherapy appears to be a rationale alternative in eradicating the entrapped residual cancer emboli after pancreatic cancer surgery. In addition, intraperitoneal chemotherapy may have a favourable effect in systemic circulation. It has been found that the measured portal vein concentrations exceeded the measured concentration in other vessels when 5-FU was administered intraperitoneally [Citation31].

High-risk patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing potentially curative resection have been effectively treated with systemic adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine [Citation32]. Nevertheless, systemic chemotherapy has not been shown to control local disease effectively. Laboratory and clinical studies have shown that the intraperitoneal use of gemcitabine may effectively target local control. There is much evidence from laboratory studies that the intraoperative intraperitoneal use of gemcitabine may prevent the development of peritoneal dissemination. In addition, it has been referred that the extent of peritoneal carcinomatosis is reduced if early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy is used [Citation33].

In a limited number of patients that underwent surgery in Washington Hospital Centre, the data showed that intraperitoneally administered gemcitabine in combination with heat at 1000 mg/m2 in 3 lit had marked local-regional exposure [Citation34]. The area-under-the-curve ratio of concentration times time for intraperitoneal to intravenous drug was 210 [Citation35]. In a clinical study in patients with advanced pancreatic malignancy, intraperitoneal gemcitabine was well tolerated with no toxicity [Citation32].

The preliminary results of surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer patients from Washington Hospital Centre have shown that there was no haematologic toxicity [Citation34]. Our preliminary data with the intraperitoneal use of gemcitabine as an adjuvant have shown that the method is well tolerated with minor toxicity in only one patient [Citation20]. This has been reproduced in our final results with only one patient presenting grade II neutropenia that did not require any specific treatment. There has been no evidence incriminating intraperitoneal gemcitabine for three anastomotic leaks. From an international multicenter study with HIPEC following distal pancreatectomy and cytoreductive surgery, the method appears to be reasonable with minor toxicity [Citation36]. Advances in surgery, anaesthesia, and perioperative care have resulted in significant decrease of morbidity and hospital mortality especially in high-volume centres even in elderly patients [Citation37–39]. Although it is obvious that all patients underwent treatment in a small-volume centre, the hospital morbidity and mortality are acceptable.

There has been much evidence that there is a positive effect on local-regional recurrence with the use of intraperitoneal gemcitabine [Citation20,Citation34]. The present study has reconfirmed the above data once only three patients (9.1%) have been recorded with local-regional recurrence. All these patients were T3N1 stage. This histopathological finding confirms that locally advanced tumours have the tendency to disseminate locally during surgery. However, there were one patient T3N0, and three T3N1 patients who are still disease free. This means that HIPEC may significantly eliminate the risk of local-regional recurrence in high-risk patients. On the contrary, the overall 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate has been found to be 46.7%, 37.6%, 28%, and 24%, respectively, which is similar to survival that has been reported from high-volume centres [Citation24,Citation40]. The weak point of the study is the short time of follow-up and the small number of the included patients. However, three patients live without disease more than 5 years.

Conclusions

The data possibly indicate that HIPEC as an adjuvant treatment after potentially curative (R0) resection of pancreatic cancer may effectively control the local-regional recurrence. Prospective randomised studies are required for the documentation of these findings.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Schneider G, Siveke JT, Eckel F, Schmid RM. (2005). Pancreatic cancer: basic and clinical aspects. Gastroenterology 128:1606–25.

- Geer RJ, Brennan MF, Cameron J, et al. (1993). Prognostic indicators for survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg 165:68–73.

- Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby TV, van Heerden JA. (1995). Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg 221:59–66.

- Birkmeyer JD, Warshaw AL, Finlayson SRG, et al. (1999). Relationship between hospital volume and late survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 126:178–83.

- Bramhall SR, Allum WH, Jones AG, et al. (1995). Treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer, and incidence of the disease, in the West Midlands: an epidemiological study. Br J Surg 82:111–15.

- Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M. (2002). Cancer statistics 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 52:23–47.

- Beger HG, Rau B, Gansauge F, et al. (2008). Pancreatic cancer-low survival rates. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105:255–62.

- Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. (2003). Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg 237:74–85.

- Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. (2006). One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg 244:10–15.

- Warshaw AL, Fernandez-del Castillo C. (1992). Pancreatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med 326:455–65.

- Sugarbaker PH. (1996). Observations concerning cancer spread within the peritoneal cavity and concepts supporting an ordered pathophysiology. In: Sugarbaker PH, ed. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: principles and practise of management. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic, 79–100.

- Tu Y, Tian Y, Fang Z, et al. (2016). Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion for the treatment of gastric cancer: A single-centre retrospective study. Int J Hypertmermia 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2016.1190987.

- Yan TD, Black D, Savady R, Sugarbaker PH. (2006). A systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Ann Surg Oncol 14:484–92.

- Yan TD, Welch L, Black D, Sugarbaker PH. (2007). A systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol 18:827–34.

- Rossi CR, Deraco M, De Simone M, et al. (2004). Hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery for the treatment of abdominal sarcomatosis: clinical outcome and prognostic factors in 60 consecutive patients. Cancer 100:1943–50.

- Bakrin N, Bereder JM, Decullier E, et al. (2013). From the FROGHI (French Oncologic and Gynaecologic HIPEC Group). EJSO 39:1435–43.

- Randle RW, Swett KR, Shen P, et al. (2013). Cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal sarcomatosis. Am Surg 79:620–4.

- Polom K, Roviello G, Generali D, et al. (2016). Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. Int J Hyperthermia 32:298–310.

- Ching Tan GH, Ong WS, Chia CS, et al. (2016). Does early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC) for patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) make a difference? Int J Hyperthermia 32:281–8.

- Tentes AA, Kyziridis D, Kakolyris S, et al. (2012). Preliminary results of hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy as an adjuvant in respectable pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Res Practise 2012:506571. doi: 10.1155/2012/506571.

- Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. (1985). Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg 120:899–903.

- Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. (1999). Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg 230:776–84.

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. (2004). A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 350:1200–10.

- Hsu CC, Herman JM, Corsini MM, et al. (2010). Adjuvant chemoradiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the Johns Hopkins hospital-Mayo clinic collaborative study. Ann Surg Oncol 17:981–90.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. (2011). FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364:1817–25.

- Von Hoff DP, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, et al. (2011). Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol 29:4548–55.

- Koliopanos A, Avgerinos C, Farfaras A, et al. (2008). Radical resection of pancreatic cancer. HBPD Int 7:11–18.

- Ansari D, Gustafsson A, Andersson R. (2015). Update on the management of pancreatic cancer: surgery is not enough. World J Gastroenterol 21:3157–65.

- Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, et al. (2004). Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol 22:3284–92.

- Dedrick RL. (1985). Theoretical and experimental bases of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Semin Oncol 12:1–6.

- Speyer JL, Sugarbaker PH, Collins JM, et al. (1981). Portal levels and hepatic clearance of 5-fluorouracil after intraperitoneal administration in humans. Cancer Res 41:1916–22.

- Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. (2007). Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297:267–77.

- Ridwelski K, Meyer F, Hribaschek A, et al. (2002). Intraoperative and early postoperative chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity using gemcitabine may prevent postoperative occurrence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol 79:10–16.

- Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA, Bijelic L. (2012). Intraperitoneal gemcitabine chemotherapy as an adjuvant treatment for patients with resected pancreatic cancer: phase II and pharmacologic studies. Transl Gastrointestin Cancer 1:161–8.

- Pestieau SR, Stuart OA, Chang D, et al. (1998). Pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal gemcitabine in a rat model. Tumori 84:706–11.

- Schwartz L, Votanopoulos K, Morris D, et al. (2016). Is the combination of distal pancreatectomy and cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC reasonable? Results of an international multicenter study. Ann Surg 263:369–75.

- Renz BW, Khalil PN, Mikhailov M, et al. (2016). Pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head is justified in elderly patients: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 28:118–25.

- Wittel UA, Makowiec F, Sick O, et al. (2015). Retrospective analyses of trends in pancreatic surgery: indications, operative techniques, and postoperative outcome in 1120 pancreatic resections. World J Surg Oncol 13:102. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0525-6.

- Benassai G, Mastrorilli M, Quarto G, et al. (2000). Factors influencing survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol 73:212–18.

- Magistrelli P, Antinori A, Crucitti A, et al. (2000). Prognostic factors after surgical resection for pancreatic carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 74:36–40.