Abstract

Introduction: The treatment of advanced primary or recurrent ephitelial ovarian cancer still remains an open and a critical question. The addition of HIPEC to cytoreductive surgery has shown improving overall survival rates. The aim of our study is to describe the progress in its management in our Unit and what we have learned after more than 350 HIPEC procedures.

Methods: From 1997 to 2016 we conducted a retrospective analysis from a prospective database. We described and analyzed 4 cut-points, 1997–2004, 2009, 2012 and 2016.

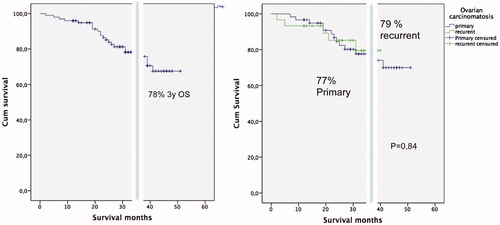

Results: From 1997 to September 2016, 358 patients have been operated in our Unit by CRS with peritonectomy procedures plus HIPEC for stage IIIc and IV ovarian cancer. The HIPEC procedures rate was 4,7 HIPEC per years in the first years up to 35 HIPEC/year in last era. Mean age was 56,7 years (28–78). Median PCI was 15,8. (range 3–36). R0-cytoreduction was 95%. Severe morbidity and mortality were observed in 15 % and 2%, respectively. The 3 y OS was 77% in primary and 79% in recurrent ovarian cancer. The stage IV was not a risk factor for survival. R1 cytoreduction and positive lymph nodes were risk factors in multivariate analysis.

Conclusion: The addition of HIPEC to CRS improves overall survival rates for primary and recurrent ovarian cancer. This therapeutic strategy was incorporated twenty years ago for a few teams in the world and today there is an emerging and strong evidence that could consider it as an standard treatment for the ovarian carcinomatosis.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth cause of death from cancer in women, being the most frequent cause of death among gynecological malignancies in developed countries [Citation1]. Unfortunately, most of the patients will present advanced-stage disease at initial diagnosis, this fact is intimately related to a poor prognosis.

The treatment of advanced primary or recurrent ephitelial ovarian cancer (EOC) still remains an open and critical question. The standard treatment consists of optimal cytoreduction and adjuvant platinum–based chemotherapy. However, more than half of patients will recur [Citation2].

The identification of the best treatment to prolong the time to progression and overall survival with low impact on quality of life is of prime concern. As EOC is restricted to the abdominal cavity for most patients, intraperitoneal chemotherapy is an especially attractive and effective treatment [Citation3].

The GOG 172 [Citation3] study showed a longer median overall survival rate with optimal cytoreduction followed by intraperitoneal chemotherapy with intravenous chemotherapy. These survival benefits were confirmed in a 10-year follow-up [Citation4] and a posterior meta-analysis [Citation5]. Despite this interesting survival benefit, this treatment has not been widely adopted because of its toxicity and patients’ difficulty to complete all six cycles (a completion rate of 42%).

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may solve the aformentions problems associated to delays and repetitive intraperitoneal chemotherapy cycles, HIPEC is administered directly into the abdominal cavity after complete cytoreduction, as primary, interval or consolidation therapy associated to intravenous chemotherapy. The addition of HIPEC to cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and chemotherapy has shown improved overall survival rates for both primary and recurrent EOC in a recent meta-analysis [Citation6] and a phase III randomised and controlled trial (RCT) [Citation7].

From 1997 our Oncologic Surgery Unit has been performing CRS with peritonectomy procedures plus HIPEC with paclitaxel for primary and recurrent carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. The aim of this study is to describe the progress in the management of this disease and what has been learned after more than 350 HIPEC procedures for stage IIIc and IV ovarian cancer.

Methods

From January 1997 to September 2016, 358 patients have been operated on in our Unit by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for stage IIIc and IV ovarian cancer. We conducted a retrospective analysis from a prospective database. All cases were discussed in a pre-treatment multidisciplinary committee. The overall inclusion criteria were histological confirmation of peritoneal carciomatosis from EOC (including both primary and recurrent), treated with CRS and HIPEC, stage IIIc or IV FIGO classification and a good performance status (ECOG ≤ 2). We described and analysed 4 cut-points, 1997–2004 (cut-point I), 2005 to 2009 (cut-point II), 2010 to 2012 (cut-point III) and 2013 to September 2016 (cut-point IV).

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

From 2004, following our protocol [Citation8] for advanced ovarian cancer, all patients with primary ovarian cancer FIGO stage IV received 4 to 8 cycles of carboplatin-plus-paclitaxel based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. All cases included in the present study showed an appropriate response (i.e. radiological tumour stabilisation or regression to FIGO stage IIIc). The majority of patients with primary ovarian cancer FIGO stage IIIC suspected of a high Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) by imaging tests received the same neoadjuvant regimen but in 4 cycles with radiological and tumour markers evaluation after the third cycle.

Finally, when the peritoneal carcinomatosis was a consequence of recurrent ovarian cancer, all patients received preoperative chemotherapy, and the regimen depended on the sensibility to platinum, platinum resistant were not excluded if response or stabilisation was seen.

Surgical procedure (CRS + HIPEC) and postoperative chemotherapy

The surgical management details will be described in each era. Generally and briefly the tumour burden was estimated by the PCI and all the subjects underwent a pelvic or infra-abdominal peritonectomy, including complete removal of the peritoneum from pelvis to bilateral iliac fossae using a full centripetal dissection, complete greater omentectomy, appendectomy, and anterior resection of the rectum if involved. According to PCI and tumour involvement, a total peritonectomy could be necessary, which included extended peritonectomy plus diaphragmatic surfaces and Glisson’s capsule, lesser omentum and omental bursa. Cholecystectomy, splenectomy, pancreatectomy, partial stomach, colon and/or small bowel resections, and segmental hepatectomy were additionally performed if tumour invasion was present. Extended pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy was selectively performed in patients with macroscopic bulky lymph nodes. In cut-point I (1997–2004), the degree of cytoreduction after radical CRS was determined according to the classification described by the Gynaecologic Oncology Group (GOG) in which R0-cytoreduction means the absence of residual macroscopic tumour; R1-cytoreduction, the presence of residual tumour implants ≤1 cm; and R2-cytoreduction, tumour implants >1 cm. In 2004, the Completeness Cytoreduction Score (CC) was also adopted for evaluation of cytoreduction degree. From then on, both methods for classifying cytoreduction have been incorporated considering R0 as equivalent to CC0 only for HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis.

HIPEC was administered for 60 min with paclitaxel (60 mg/m2/2 L of solution) diluted in 1.5% dextrose peritoneal dialysis solution, heated at 41–43 °C, and infused with two Tenckhoff catheters (Quinton Inc., Seattle, WA®) at 1000 ml/min. Patients with previous allergic reactions to paclitaxel received intraperitoneal cisplatin (75 mg/m2/2 L of solution) under the same conditions. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy was delivered after all resections were completed and before the placement of any suture lines, using the Coliseum technique, an open procedure which utilises a heat exchanger, two roller pumps and a heater/cooler unit (Stoeckert, Munich, Germany®).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data were recorded in a categorical fashion and quantitative covariates were measured on a continuous, rather than on an interval, scale. Qualitative covariate comparisons between groups were performed by Chi square test, and quantitative covariables were compared by T-Test when a normal distribution was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test were performed to evaluate the survival data. Results are reported as follows; the number of patients (n) and/or the respective percentage (for covariates analysed as qualitative data), mean and standard deviation (SD) (for covariates analysed as quantitative data). Odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were considered for logistic regression. A p values of < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

From 1997 to September 2016, 358 patients have been operated on in our Unit by CRS with peritonectomy procedures plus HIPEC for stage IIIc and IV (with previous neoadjuvant treatment and down-staging) ovarian cancer. The HIPEC procedures rate had been increased in each cut-point, with 4,7 HIPEC/year in cut-point I up to 35 HIPEC/year in September 2016 (.

Figure 1. Rate of number of HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis performed per year in our Unit.

Cut-point 1: 1997–2004

The first peritonectomy procedure and HIPEC for EOC stage IIIc was performed in January 1997 by Prof. Pera-Madrazo and Prof. Rufian-Peña. From January 1997 to December 2004, 33 HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis were done [Citation9]. 19/33 Patients had peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer and 14/33 patients had peritoneal carcinomatosis from recurrent ovarian cancer. The mean age was 55 (28–72). A total peritonectomy was carried out in 13 patients (39%). A considerable number of patients (14/33, 42%) required intestinal resection. Cytoreductive surgery grade after radical peritonectomy was considered as optimal-R0 in 17 patients (52%), optimal-R1 in 11 patients (33%), and suboptimal-R2 with presence of residual tumour >1cm in 5 patients (15%). Lymphatic node infiltration occured in 11 patients (37% in primary ovarian cancer and 29% in recurrent ovarian cancer). Major postoperative morbidity was observed in 12 patients (36%). Two patients required further surgery, one a hemoperitoneum and the other, a gastric perforation. There was no postoperative mortality in this series.

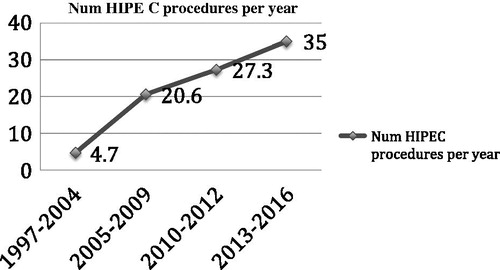

Survival analysis

The mean overall survival estimated by the Kaplan–Meier curve was 48 months (38 months for primary and 57 months for recurrent EOC), independently of the cytoreduction grade, peritonectomy procedure, or lymph nodes. The median regional relapse free survival was 25 months in primary cancer and 31 months in recurrent cancer. The 5 year overall survival (OS) rate of the patients were 37% at 5 years in primary ovarian cancer, and 51% in recurrent ovarian cancer. These results were significantly improved when an optimal-R0 cytoreduction was achieved, reaching a 5 year OS of 60%. Lymphatic metastatic affection significantly decreased survival rates up to 19% in 3 years. 83% 5y OS was achieved in the group of patients that associated recurrent ovarian cancer to optimal cytoreduction R0, subtotal infra-abdominal peritonectomy, and negative lymph nodes.

Multivariate analysis using the multiple regression method of Cox suggested that the predictive survival variables in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (stage III of FIGO) submitted to radical surgery with peritonectomy and combined intraperitoneal and systemic adjuvant chemotherapy were due to the complete cytoreduction and the lymph node invasion ().

Figure 2. 1997–2004. Kaplan–Meier’s overall survival rates of 33 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer and recurrent ovarian cancer after radical-peritonectomy and hypertermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy [Citation9].

![Figure 2. 1997–2004. Kaplan–Meier’s overall survival rates of 33 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer and recurrent ovarian cancer after radical-peritonectomy and hypertermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy [Citation9].](/cms/asset/7aef6754-cd03-45fe-97e8-d1af0f4223b7/ihyt_a_1278631_f0002_b.jpg)

Cut-point: 2005 to 2009

From January 2005 to December 2009, 136 HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis were performed. A total of 84 (62%) patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer and 52 (38%) patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from recurrent ovarian cancer were operated on in our Unit. During this period 62% of the patients with primary serous ovarian carcinomatosis who had a high PCI in preoperative evaluation received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with carbo-taxol for 4 cycles, and we evaluated the response. The mean age was 55.9 years (range 24–77). 29/136 (21%) Patients were stage IV FIGO who had a response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and down-staging.

Therefore, in 65% of our patients R0/CC0 cytoreduction was achieved, R1 in the 26% and R2 in 9%. The positive lymph nodes were in 38% of the patients. Intestinal resection was performed in 60% of the cases. The PCI was measured in this period, with a mean of 14.8 and a range of (3–29). Major morbidity (≥grade 3) was present in 12% of the cases. The postoperative mortality was 1,5% (2/136).

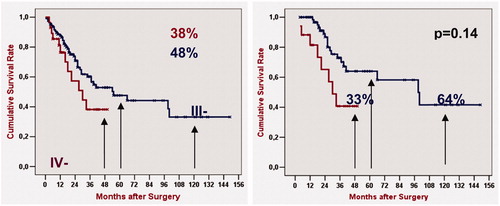

Survival analysis

The 5y OS in stage IIIc and the 4 y OS in stage IV were 48% and 38% respectively, and no difference were found (p = 0.140). When a R0/CC0 was achieved, the 5y and 4y overall survival rate increased to 64% and 41%, respectively and there was a statistically significant difference between both (p = 0.02). When a multivariate analysis was performed the grade of cytoreduction was the prognostic factor to survival (.

Figure 3. Up to 2009 Kaplan–Meier’s overall survival rates of 136 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer and recurrent ovarian cancer after radical-peritonectomy and hypertermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Log-rank test analysis was performed to compare Stage IIIc vs. IV FIGO, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cut-point 3: 2010 to 2012

From January 2010 to June 2012, 218 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer (FIGO stage IIIC or IV) were treated with CRS and HIPEC [Citation10]. Mean age was 56 (range 19–80), with 11% of women over 70. Radiological evidence for down-staging from FIGO stage IV was present in 42 patients (19%). Median PCI was 14 (range 3–30). Extended or total peritonectomy procedures were performed in 156/218 patients (72%). Isolated or multiple bowel resections were completed in 125/218 (57%). R0/CC0 was achieved in 159/218 subjects (73%). Positive lymph nodes after surgical lymphadenectomy were observed in 79/218 patients (36%). A total of 124/218 women (57%) presented peritoneal carcinomatosis from primary ovarian cancer (neoadjuvant therapy in 84%) and 94/218 (43%) from recurrent ovarian cancer. Severe surgical morbidity (Dindo–Clavien III or IV) was observed in 13.8% (30/218) of patients. The reoperation rate was 6.9% (15/218). Three patients (1.4%) died postoperatively.

Survival analysis

Median follow-up time was 33 months. The median overall survival (OS) was 57 months in primary ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis and 55 months in recurrent ones. The 5y OS was 49% in primary and 47% in recurrent ovarian cancer. The median relapse free survival time was 24 months in primary and 19 months in recurrent ovarian cancer. Multivariate analysis identified four independent predictors of OS: R0/CC0-cytoreduction, PCI, positive lymph nodes, and morbidity grade ≥ III. Stage IV FIGO was not a risk factor in the univariate analysis for survival. No significant statistical differences between primary and recurrent ovarian cancer were found in this group of patients (.

Figure 4. Up to 2012. Overall survival Kaplan–Meier curves for the statistically significant variables with Log-rank test. (A) Cytoreduction score. (B) Peritonectomy procedures. (C) Peritoneal Cancer Index. (D) Intestinal resection. (E) Lymph node status. (F) Postoperative Morbidity by Dindo–Clavien classification [Citation10].

![Figure 4. Up to 2012. Overall survival Kaplan–Meier curves for the statistically significant variables with Log-rank test. (A) Cytoreduction score. (B) Peritonectomy procedures. (C) Peritoneal Cancer Index. (D) Intestinal resection. (E) Lymph node status. (F) Postoperative Morbidity by Dindo–Clavien classification [Citation10].](/cms/asset/97ba6567-491c-4336-a03a-f3d0434ce809/ihyt_a_1278631_f0004_c.jpg)

Cut-point 4: July 2012 to September 2016

From July 2012 to September 2016, 140 patients were operated by HIPEC procedure for ovarian carcinomatosis. Mean age was 56.7 years (28–78). Radiological evidence for down-staging from FIGO stage IV was present in 25 patients (18%). Median PCI was 15,8 (range 3–36). Extended or total peritonectomy procedures were performed in 117 patients (84%). Isolated or multiple bowel resections were done on 78 (56%). R0/CC0 was achieved in 95%. Positive lymph nodes after surgical lymphadenectomy were observed in 23.8% of the patients. A total of 93 women (67%) presented primary peritoneal carcinomatosis (87% received neoadjuvant therapy) and 47 (33%) from recurrent ovarian cancer. Severe surgical morbidity (Dindo–Clavien III or IV) was observed in 21 patients (15%). The reoperation rate was 6%. Three patients (2%) died postoperatively.

Survival analysis

Median follow-up time was 33 months. The median overall survival (OS) was 43 months in primary and 35 months in recurrent ovarian cancer. The 3y OS was 77% in primary and 79% in recurrent ovarian cancer with no differences between both. The stage IV FIGO was not a risk factor for survival in univariate analysis, but suboptimal cytoreduction and positive lymph nodes were risk factors in a multivariate analysis. The median relapse free survival time was 27 months (.

Discussion

We present the experience and the evolution in the management of Stage IIIc and IV ovarian carcinoma in our Unit of Oncologic Surgery. Currently the treatment in advanced stage ovarian carcinoma still remains controversial, but the evolution in systemic and surgical management adding loco-regional therapies as HIPEC, have increased the survival expectations for these patients. As we have shown above, our Unit has increased the number of HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis every year, reaching the rate of 35 HIPEC/year from an initial rate of 4,7 HIPEC/year. Some improvements have been incorporated: a standardised procedure, protocol [Citation8] set up and improved technical skills with a learning curve of more than 700 HIPEC procedures for different diseases. Because of this, results have improved, as demonstrated with a R0/CC0 rate of 95% in the last cut-point in addition to a higher mean PCI and a higher mean patient age. The four cut-points were analysed and the data suggests that the standard treatment for ovarian carcinomatosis could incorporate a complete cytoreduction with peritonectomy procedures and HIPEC.

From 1997 to 2004

Our Unit performed the first peritonectomy and HIPEC procedure in January 1997 for ovarian carcinomatosis. In the same period multiple changes took place, systemic chemotherapy improved their survival results with the use of platinum associated to taxanes as adjuvant therapy as McGuire et al. [Citation11] showed (38 months vs. 24 months). This was established as the standard treatment in the different international guidelines. Another interesting and controversial concept was the optimal cytoreduction definition in advanced stage ovarian cancer. Regarding this, Bristow et al. [Citation12] conducted a meta-analysis to resolve some controversial aspects: define the optimal cytoreduction, the impact of residual disease on survival in the platinum era and the effect that the type of Unit which perform the cytoreduction had on the patient prognosis. Several conclusions were reached: for the optimal cytoreduction definition, only one study included in this meta-analysis defined the maximal cytoreduction less than 0,5 cm, where most defined it as less than 2 cm, 41,9% being the mean percentage of maximal cytoreductive surgery for all cohorts. While the CRS with peritonectomy procedure offered no residual disease cytoreduction [Citation9,Citation13] it was not considered in this meta-analysis. Another important point was that an experienced centre had a higher rate of cytoreduction (75%) than others less experienced (25%). In this sense, Hoskins et al. [Citation14], in the GOG 52 and 97 protocols, defined a disease larger than 1 cm as suboptimal, furthermore, survival differences between microscopic residual disease and residual disease ≤1 cm were shown.

In recent years, HIPEC has been widely applied in cytoreductive and peritonectomy surgical procedures in order to eradicate residual microscopic disease and to improve survival rates of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of different origins. Sugarbaker [Citation13] suggested that carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer could be an indication for the application of this procedure. Nevertheless, HIPEC procedure for ovarian carcinomatosis has a ways to come before becoming a standard treatment because few institutions have developed this radical surgical approach associated to peritonectomy procedures and HIPEC in ovarian cancer. The procedure’s complexity, the morbidity associated to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy and the absence of RCT phase III could be considered the main reasons. In the study presented in this paper [Citation9], patients were treated with a derivative of taxanes, such as paclitaxel, which demonstrated high antineoplasic activity in the treatment of ovarian cancer while having few side effects and an adequate tolerability in peritoneal administration [Citation15]. The overall survival rates obtained are higher than those of the standard treatment and worth further analysis, although, to be considered as a standard treatment, there should be randomised phase III trials to confirm these results and those of other authors [Citation16–18].

2005 to 2009

New concepts were being incorporated to the standard treatment for stage III and IV ovarian cancer, such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy, completeness of cytoreduction and neoadjuvant therapy but not for cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC [Citation19]. The intraperitoneal chemotherapy was considered standard therapy for ovarian carcinomatosis thanks to the survival benefit showed by the phase III RCT by Amstrong et al. [Citation3] in 2006. In spite of the survival benefits, this therapeutic approach had not been widely adopted because its high toxicity and morbidity and the difficulty for the patients to complete all the cycles (42% rate of completion). Neoadjuvant therapy with platinum/taxanes was categorised as standard treatment only for borderline resectable disease or stage IV disease [Citation19]. We adopted the neoadjuvant therapy in our protocol for borderline resectable ovarian carcinomatosis stage IIIc and IV [Citation8].

The cytoreductive surgery with peritonectomy procedures and HIPEC was not a standard treatment but its use and acceptation were increasing in popularity. By means of technical refinements acquired with the experience, postoperative management, the standardisation of surgical technique and the application of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (2007 protocol [Citation8]) the number of cytoreductive and HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis were increased up to 138 in 2009 with a rate of HIPEC/year of 20,6 (previously 4,7 HIPEC/year). Furthermore, the percentage of R0 cytoreduction and primary carcinomatosis increased because of the setting up protocol for primary ovarian carcinomatosis. 62% of primary ovarian carcinomatosis received neoadjuvant therapy (carbo/taxol) for 4 cycles, interval cytoreductive surgery plus HIPEC and 4 additional cycles. The results shown above are comparable to other cohorts published in the same period [Citation1,Citation20]. Up to 2009 only retrospective studies and two systematic review [Citation20,Citation21] were published for the use of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for ovarian carcinomatosis. Chua T.C. et al. [Citation20] analysed 19 studies that reported the treatment results of HIPEC for patients with both primary and recurrent ovarian cancer, all of them were observational case series and the heterogeneity was high between different studies, however they concluded that the complete cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC procedure may be a feasible option with potential benefits that were compared to standard treatment at least. Others studies from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [Citation22] and Mayo Clinic [Citation23] concluded that such aggressive surgical policy resulted in increased optimal cytoreduction rates and significantly improved oncological outcome.

In this period, stage IV patients were included, following the trend of different studies, but these patients were included only if they had a radiological and biochemical down-staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Differences in survival were detected between the two stages but not in the next periods.

2010 to 2012

During this period, comparative studies, without randomised and controlled trials, were performed, increasing the level of evidence in favour of HIPEC in the treatment of ovarian carcinomatosis, but not enough to consider it as standard treatment. Our group published, in 2009 [Citation24], a comparative study for recurrent ovarian carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) plus HIPEC and chemotherapy vs. CRS and chemotherapy. An improvement in 5y overall survival from 17% to 57% in the HIPEC group was found. Up to 2012 our Unit operated on 218 patients with ovarian carcinomatosis and we showed a 5y overall survival rate for primary and recurrent of 49% and 47%, respectively, these data included 42 stage IV patients with previous down-staging, these data showed an improving in survival rate when compared with the standard treatment Another important consideration would be the ability to offer these procedures to patients with FIGO stage IV. The overall 5-year survival in this group was 39% (49%, if R0/CC0-cytoreduction), significantly better than the OS achieved with conventional palliative treatments. Patient’s age had been increased and 11% were older than 70, age itself not being considered a contraindication for these procedures.

In this period, the rate of HIPEC procedures for ovarian carcinomatosis were increased per year up to 27,3 HIPEC/year (). We helped to create others units of surgical oncology in Spain and we started several research projects in HIPEC procedure. As a pilot study with laparoscopic HIPEC in neoadjuvant therapy associated to endovenous chemotherapy and posterior CRS + HIPEC yielded promising results [Citation25] and a randomised controlled trial of normothermia vs. hyperthermia for intraperitoneal chemotherapy with paclitaxel in ovarian carcinomatosis is currently in data analysis phase [Citation26].

2013 to 2016

Nowadays, the level of evidence in favour of the use of CRS and HIPEC for ovarian carcinomatosis has increased with the publication of a meta-analysis with 9 comparatives studies [Citation6] and a phase III RCT [Citation7]. Furthermore, multiple observational studies from different institutions with several large cohorts of patients have been published. Spiliotis et al. [Citation7] achieved a 3y overall survival of 75% for HIPEC groups, these results are similar with our last survival analysis shown above.

In the last period, our Unit has increased the rate of HIPEC procedures per year to 35. Some improvements and standardizations have been incorporated and many lessons have been taken from the experience. Despite the fact that the mean PCI and age has increased, the R0/CC0 percentage has increased (up to 95%). The perioperative management has been improved with the incorporation of motivated anaesthetists who provide an exhaustive fluid/volume control demonstrating its impact in the postoperative complications [Citation27]. We avoid the systematic ureteral catheter allocation because its impact in acute renal dysfunction [Citation27]. We use the CRP analysis systematically in the postoperative course to detect early an infectious complicaton [Citation28]. Although the neoadjuvant therapy is controversial [Citation29,Citation30] in advanced ovarian cancer, we continue using it in our protocol [Citation8], because our survival analysis has shown the neoadjuvant therapy to be beneficial [Citation10].

Conclusions

The addition of HIPEC to CRS and systemic chemotherapy could improve the overall survival rates for primary and recurrent ovarian carcinomatosis. This procedure should be performed by an oncological Unit with experienced and motivated surgeons trained in oncology and cytoreductive surgery. This therapeutic strategy was first incorporated twenty years ago by a small number of teams worldwide. However, because there is currently strong and emerging evidence in favour of it, CRS and HIPEC has gained popularity and nowadays, numerous groups perform it. If these trends continue, complete cytoreduction and HIPEC could become a standard treatment in ovarian carcinomatosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the members of Unit of Oncologic Surgery and the Unit of Oncology, Hospital University Reina Sofia, Cordoba, Spain.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. (2014). Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64:9–29.

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. (2013). Newly diagnosed and relapsed epitelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 24 (Suppl 6):v24–33.

- Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. (2006). Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 354:34–43.

- Tewari D, Java JJ, Salani R, et al. (2015). Long-term survival advantage and prognostic factors associated with intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatment in advanced ovarian cáncer. J Clin Oncol 33:1460–6.

- Chang SJ, Hodeib M, Chang J, Bristow R. (2013). Survival impact of complete cytoreduction to no gross residual disease for primary-stage ovarian cáncer: a metanalysis. Gynecol Oncol 130:493–8.

- Huo YR, Richards A, Liauw W, Morris DL. (2015). Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 41:1578–89.

- Spiliotis J, Halkia E, Lianos E, et al. (2015). Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective randomized phase III Study. Ann Surg Oncol 22:1570–5.

- Munoz-Casares FC, Rufian S, Rubio MJ, et al. (2007). Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Present, future directions and proposals. Clin Transl Oncol E 9:652–62.

- Rufian S, Munoz-Casares FC, Briceno J, et al. (2006). Radical surgery-peritonectomy and intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in recurrent or primary ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 94:316–24.

- Muñoz-Casares FC, Medina-Fernández FJ, Arjona-Sánchez Á, et al. (2016). Peritonectomy procedures and HIPEC in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer: long-term outcomes and perspectives from a high-volume center. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:224–33.

- McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. (1996). Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 334:1–6.

- Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, et al. (2002). Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 20:1248–59.

- Sugarbaker PH. (1996). Complete parietal and visceral peritonectomy of the pelvis for advanced primary and recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Res 81:75–87.

- Hoskins WJ, McGuire WP, Brady MF, et al. (1994). The effect of diameter of largest residual disease on survival after primary cytoreductive surgery in patients with suboptimal residual ephitelial ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170:974–80.

- de Bree E, Rosing H, Filis D, et al. (2008). Cytoreductive surgery and intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with paclitaxel: a clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Ann Surg Oncol 15:1183–92.

- Piso P, Dahlke MH, Loss M, et al. (2004). Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2:21–5.

- Zanon C, Clara R, Chiappino I, et al. (2004). Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for recurrent peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. World J Surg 28:1040–5.

- Deraco M, Rossi CR, Pennacchioli E, et al. (2001). Cytoreductive surgery followed by intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion in the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase II clinical study. Tumori 87:120–6.

- Aebi S, Castiglione M. (2009). Newly and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 20 (Suppl 4):iv21–3.

- Chua TC, Robertson G, Liauw W, et al. (2009). Intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cáncer peritoneal carcinomatosis: systematic review of current results. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1637–45.

- Bijelic L, Jonson A, Sugarbaker PH. (2007). Systematic review of cytoreductive surgery and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in primary and recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 18:1943–50.

- Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Land J, et al. (2006). What is the optimal goal of primary cytoreductive surgery for bulky stage IIIC epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC)? Gynecol Oncol 103:559–64.

- Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, et al. (2006). Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 107:77–85.

- Muñoz-Casares FC, Rufian S, Rubio MJ, et al. (2009). The role of hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC)in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in recurrent ovarian cáncer. Clin Transl Oncol 11:753–9.

- Munoz-Casares FC, Rufian S, Arjona-Sanchez A, et al. (2011). Neoadjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy with paclitaxel for the radical surgical treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in ovarian cancer: a prospective pilot study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 68:267–74.

- Role of intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy with paclitaxel in the surgical treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Hyperthermia Versus Normothermia. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02739698?term=hyperthermia+ovarian&rank =18 [last accessed 26 Oct 2016].

- Arjona-Sánchez A, Cadenas-Febres A, Cabrera-Bermon J, et al. (2016). “Assessment of RIFLE and AKIN criteria to define acute renal dysfunction for HIPEC procedures for ovarian and non ovarian peritoneal malignances”. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:869–76.

- Medina-Fernandez J, Munoz-Casares FC, Arjona-Sanchez A, et al. (2015). Postoperative time course and utility of inflammatory markers in patients with ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Ann Surg Oncol 22:1332–40.

- Meyer LA, Cronin AM, Sun CC, et al. (2016). Use and effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:3854–63.

- Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, et al. (2010). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC and IV ovarian cáncer. N Engl J Med 363:943–53.