Abstract

Aim: The treatment of peritoneal surface malignancies ranges from palliative care to full cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy, HIPEC. Ongoing monitoring of patient recruitment and volume is usually carried out through dedicated registries. With multiple registries available worldwide, we sought to investigate the nature, extent and value of existing worldwide CRS and HIPEC registries.

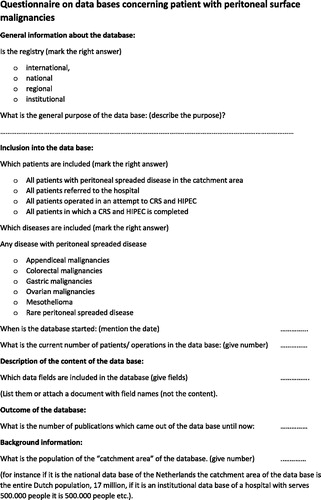

Methods: A questionnaire was sent out to all known major treatment centres. The questionnaire covers: general purpose of the registry; inclusion criteria in the registry; the date the registry was first established; volume of patients in the registry and description of the data fields in the registries. Finally, the population size of the catchment area of the registry was collected.

Results: Twenty-seven questionnaires where returned. National databases are established in northwest European countries. There are five international general databases. Most database collect data on patients who have undergone an attempt to CRS and HIPEC. Two registries collect data on all patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis regardless the treatment. Most registries are primarily used for tracking outcomes and complications. When correlating the number of cases of CRS and HIPEC that are performed to the catchment area of the various registry, a large variation in the number of performed procedures related to the overall population was noted, ranging from 1.3 to 57 patients/million year with an average of 15 patients/1 million year.

Conclusions: CRS and HIPEC is a well-established treatment for peritoneal surface malignancies worldwide. However, the coverage as well as the registration of treatment procedures differs widely. The most striking difference is the proportion of HIPEC procedures per capita which ranges from 1.3 to 57 patients per million. This suggests either a difference in patient selection, lack of access to HIPEC centres or lack of appropriate data collection.

Introduction

The roll out of CRS and HIPEC for peritoneal surface malignancies, such as peritoneal carcinomatosis originating from colorectal cancer, came in the same time frame as the development of big data bases used for clinical outcome evaluations. This coincidence has given an easy opportunity to create data bases on patients with peritoneal surfaces malignancies from the beginning of the development of this new treatment. Today, there are thousands of patients in these databases with an ocean of information that can easily be utilised.

The treatments cytoreduction and hyperthermic intra peritoneal chemotherapy (CRS & HIPEC) were developed in 1980s as a treatment for peritoneal surface malignancies [Citation1]. The treatment contains two major parts, starting with cytoreduction, followed by HIPEC. During the cytoreduction, all visible tumours are resected. Because of the nature of the spreading of the disease this is mostly done by removing parts of the peritoneum together with bowel segments and disease-affected organs [Citation2,Citation3]. The effectiveness of HIPEC has been proven in many studies, which cover the whole range from phase one studies to a meta-analysis [Citation4–10]. Most recently, there has even been published a population-based cohort study showing an increased survival in relation with this treatment [Citation11]. Despite these good results, the treatment has also made name with its high complications rates in the pioneer phase of the treatment [Citation12–14]. HIPEC is now well established and the complication rate has dropped to acceptable levels [Citation15–17].

Many of the phase two studies are registry-based studies [Citation9,Citation18–21]. Although most registries are stated as prospective databases and therefore has high-quality data, they are not specifically designed for a study. This makes the reliability of such studies not completely clear. There are a number of issues that play a role in the reliability of the outcome of these studies. The first, and probably the most determination factor outcome, is the entry into the register. It is obvious that registry-based studies can only answer question of patients or procedures in the registry. The next issue is the definitions of the data fields in the registries. A good example is the number of resections. It can be difficult to understand how to register 10 small resections or one large in a weighted manner. In the analyses of register data, 10 small resections might be presented as 10 times more compared to one big resection. Complications are another example. We are used to weight complication by the treatment needed for it. However, aggressive treatment of complications has a better outcome [Citation17,Citation22–24] but no aggressive treatment does better in registries. Thus, it is questionable whether scoring complications this way really gives a good impression on the morbidity of the treatment. At least it should be compared to peri-operative mortality

In this study, we aim to investigate the nature of peritoneal surface malignancy registries which are currently in use. We will specifically look into the coverage of the registries and the planned purpose. From this, we try to find out what possible questions the registries can answer and what the validity of the outcomes is.

Methods

The key centres from all the nations present at the ninth international congress on peritoneal surface malignancies participants list by the organisation of the congress were scrutinised. The centres were identified by looking at all the participants of the congress from each nation and combining this list with the publication lists. With this the centres with the highest number of publications or the centres that publish on the national registries were contacted. In some countries, more centres were contacted because of the equilibrium of the impact of the centres. The centres were asked to fill out a questionnaire (). Of the 41 nations contacted, there was a response from 22 nations. A number of responses covered more than one registry. This paper includes information from 46 registries.

The questionnaire was asked for general information, inclusion and description of the data base. To enhance the likelihood of getting a response the questionnaire was reduced to a minimal of information. In the general information section, the question was whether the registry was international, national, regional or institutional, thereafter the general purpose of the registry was asked. In the inclusion section, it was asked if the registry contained all patients with peritoneal spread disease in the catchment area, all patients referred to the hospital, all patients who had an attempt to HIPEC or only patients in which the HIPEC was completed. Thereafter, it was asked which diseases were included (appendiceal malignancies, colorectal malignancies, gastric malignancies, ovarian malignancies, mesothelioma or rare diseases). This section was ended with the question on the starting point of the registry and the current number of patients within the registry. In the technical section, it was questioned which data field were used in the registry. The questionnaire was ended with the questions on the number of publications out of the registry and the population in the catchment area.

As the main purpose of this study is to describe the registries and to evaluate what use the data from the registries can yield, the main statistic is descriptive. In the final part of the study, the number of patients will be related to the populations within the catchment area. For this, the annual number of patients during the period the database has been active was calculated. This entry rates are compared between the databases in a descriptive manner. This is done to get an impression on the completeness of the data related to the incidence of the disease or the eligibility of referral or treatment.

Results

In total, 46 centres were identified and were sent the questionnaire. Out of these 46 centres, 23 centres replied from 19 nations. As three centres replied about more than one registry the total number of registries in this evaluation is 27 registries. Five of the registries were international, two of them are linked by the German and English language regions, respectively. They cover the countries Austria, Germany and Switzerland for the German language group and England and Ireland for the English language group. The other three are true international registries, which are open for all institutes in the world. These three international registries deal with more rare disease such as mesothelioma, small bowel malignancies, pancreatic malignancies, soft tissue malignancies etc. Eight registries cover national data from Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. All others are institutional registries or of several institutes from a specific region. For further analysis, the registries are grouped into three groups: 1, the international registries which are open to all centres in the world; 2, the national or language group data registries and the regional and 3, institutional registries. Using this redistribution, there are three international registries, 11 national registries and 13 institutional registries. All registers together cover in total 28 786 patients and 3085 months’ time-period. The average number of patients per registry is 1107 and the average time frame is 128 months.

The general purposes of the registries are stated as quality control; outcome/selection evaluation and basic research. The three international registries deal with research and basic understanding of the disease. The national studies deal mainly with quality control and outcome and the institution registries deal with outcome and basic research. Two of the international registries include patients with attempted CRS and HIPEC and one includes patients not referred to a centre. In the national register group, most registries contain patients referred to a centre or patients who undergone the complete treatment. Two registries claim to include all patients with peritoneal surface disease of the specific disease in the country. These two nations (Denmark and the Netherlands) have a tight national registry on either all malignancies or all colorectal malignancies. These registries are combined with institutional registries of the HIPEC centres. The institutional registries cover from all patients with the disease in the catchment area to only those who are treated.

A cross match of the purpose of the registries and the entry into the registries is given in . This table shows that, in general all kind of entries are used for different evaluations. Quality control is mainly done on the referred patients, outcome is more looked at in attempted and completed patients. Basic research is done on different groups of patients. The international registries are disease specific and therefor more into research while the institutional registries are more treatment outcome orientated and local registries look at outcome ().

Table 1. Numbers of registries in relation to purpose registry and setup.

Table 2. Number of registries in relation to purpose registry and entry of the registry.

The registries include all patient demographics, date of diagnoses, extent of the disease and of treatment, most treatment details of the CRS and HIPEC, post-operative complications, pathology, biological samples including plasma and tumour banks and follow-up. The detail level of the surgical field is in all registries very high, and so are the details in complications description. Neo-adjuvant and adjuvant treatments are stated in most registries. The follow-up is mostly covered and some registries state the surgical treatment for recurrences. Other treatments during the lifespan after the HIPEC are not covered in any registries.

The coverage of the international studies is hard to estimate because of the lack of clarity on the catchment area. In the national studies and language region the catchment area is assumed to be the population of the nation or language region. With this group the inclusion in those registries which claim to cover all patients with peritoneal spread disease the inclusion ranges from 3 to 30 per million per year with an average of 20 per million per year. The registries which cover all referent patients range from 2 to 20 per million per year and for the completed CRS and HIPEC the range is from 1 to 11 per million per year. For the institutional set-up, the referred patient inclusion ranges from 1 to 5, the attempted from 4 to 32 and the completed from 1.3 to 57 with an average of 15 patients per million per year.

The scientific output measured from the number of publications per 100 patients entered is 3.2. If the registries which were not able to publish their result due to the recent start of the registries are excluded, this figure raises to 4.3 publications for every 100 patients. The number of publications by the time the registry is open is one publication, for every year the registry is open.

Discussion

In this study of 27 registries from 19 nations showed that there is a high awareness of quality assurance among centres dealing with peritoneal surface malignancies. Beside the fact that all questioned centres keep track of their own results, several nations take a large effort in bringing outcome and quality control to national and even international levels. Two prospective registries in France are supported and regularly controlled by the National Cancer Institute (INCA) [Citation25]. This on itself is an import safeguard of a relative new treatment. Besides this effort to ensure quality and outcome most centres express a big interest in research. This is reflected by the high number of publications in relation to the number of patients in the registries. Despite these promising results, there are still several methodological problems in the registries. Most of the problems are directly or indirectly related to the selection of the patients entered in the registries. The wide variation of coverage of the registry is in relation to the population, and therefore to the incidence of peritoneal surface malignancies [Citation26–29].

There are a number of different registration systems. The first group is the international registries, which are open to every centre in the world. It is obvious that the entry in these systems is based on the selection criteria in the centres which contribute to the registration. In case that the contributing centres have similar selection, criteria and are covering all patients within their catchment area, this registration systems can be useful for analysing outcome of less frequent diseases. However, both the similar selection criteria and catchment of all patients in the area are unlike. Selection criteria depend on an important part on local customs and local healthcare systems and catchment of all patients is depending on referral mechanism that is also not similar throughout the world. For this reasons, these registrations can best be seen as large collections of cases. The national registries are likely to have a more uniform selection on entry. They may include biological data such as plasma and tumour banks that are fundamental for the evaluation of rare peritoneal disease but also for the evaluation of tumour response and for translational research [Citation30]. The institutional systems have probably the most homogenous entry. However, beside these geological issues there is difference in entry over time. If a centre starts establishing itself, it will have a smaller number of referral compared to when it is established for a longer time, therefore it will by definition have a smaller coverage. There will also be a difference in disease load between the starting centres and the well-established centres [Citation23,Citation31,Citation32]. This will not only have an influence on the numbers of patients in the registry but also in the severity of the disease. All together this means that whenever we look at evaluations of registries we must take all these factors into consideration.

The other dimension of looking at registry’s entry is looking at the defined target group. If we are for example looking at registries in which only completed treatment is recorded, we can only look at outcome of the specific treatment under the selection criteria in the centres that register. In this way, we can see the performance of the resection. If we are looking at the registries which cover all patients affected, we can analyse the outcome of a population under the given treatments performed. Anything in between can give a mixture of these answers.

Probably, the most important question is: “what can we use the registries for?”. The most given answer is quality control and followed by outcome. Quality control comes mostly down to the evaluation of complications. Evaluation within an institute is certainly possible on institutional data bases, evaluation between institutes is however, much more complicated. A cross institute comparison is of value if the entry into the registry and the selection for the treatment is similar between the institutes, as complication rates are dependent on the tumour load and patient demography and co-morbidity. The same is true for outcome comparison. The question can also be put the other way around, what questions the registries can answer. Scientific question on treatment or parts of a treatment can very well be answered by prospective registries designed to answer that specific question. Finding best outcome of a disease is much more complicated to determine by registries. The main reason for this is that they show us a steady-state of the situation. An intervention like changing treatment or selection criteria can reflect as improved outcome for the populations. However, this requires measurements over time, and is clouded by any other, non-covered, alteration in the patient care that might occur simultaneously.

In conclusion, there are different registries on peritoneal surface malignancies. The fact that we have those registries shows a high awareness of quality issues. The large differences in cases performed in regard to population size, indicate that there is still an under treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis, although we do not know the optimal level yet. Local registries function well for quality control whereas the use of merged data from different registries is not completely clear. Probably the best registry is the one that starts with a question which it wants to answer and is carefully designed for that question. But, all registries including so much data will probably allow in the near future to answer quickly and more accurately to the scientific question using the new data exploitation such as data mining

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Sugarbaker PH. (2016). Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of gastrointestinal cancers with peritoneal metastases: Progress toward a new standard of care. Cancer Treat Rev 48:42–9.

- Loggie BW, Thomas P. (2015). Gastrointestinal cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis: surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 29:515–21.

- Witkamp AJ, de Bree E, Kaag MM, et al. (2001). Extensive cytoreductive surgery followed by intra-operative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with mitomycin-C in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Eur J Cancer 37:979–84.

- Cavaliere F, Valle MD, Simone M, et al. (2006). 120 peritoneal carcinomatoses from colorectal cancer treated with peritonectomy and intra-abdominal chemohyperthermia: a S.I.T.I.L.O. multicentric study. In Vivo 20(6A):747–50.

- Ceelen WP. (2005). Use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal origin. Surg Technol Int 14:125–30.

- Elias D, Pocard M, Goere D. (2007). HIPEC with oxaliplatin in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Cancer Treat Res 134:303–18.

- Mirnezami R, Mehta AM, Chandrakumaran K, et al. (2014). Cytoreductive surgery in combination with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases compared with systemic chemotherapy alone. Br J Cancer 111:1500–8.

- Moran BJ, Meade B, Murphy E. (2006). Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy and cytoreductive surgery for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a novel treatment strategy with promising results in selected patients. Colorectal Dis 8:544–50.

- Piso P, Dahlke MH, Ghali N, et al. (2007). Multimodality treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: first results of a new German centre for peritoneal surface malignancies. Int J Colorectal Dis 22:1295–300.

- Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, et al. (2003). Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 21:3737–43.

- Razenberg LG, Lemmens VE, Verwaal VJ, et al. (2016). Challenging the dogma of colorectal peritoneal metastases as an untreatable condition: results of a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 65:113–20.

- Rouers A, Laurent S, Detroz B, Meurisse M. (2006). Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: higher complication rate for oxaliplatin compared to Mitomycin C. Acta Chir Belg 106:302–6.

- Smeenk RM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. (2006). Toxicity and mortality of cytoreduction and intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in pseudomyxoma peritonei–a report of 103 procedures. Eur J Surg Oncol 32:186–90.

- Verwaal VJ, van Tinteren H, Ruth SV, Zoetmulder FA. (2004). Toxicity of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy. J Surg Oncol 85:61–7.

- Mehta SS, Gelli M, Agarwal D, Goere D. (2016). Complications of cytoreductive surgery and hipec in the treatment of peritoneal metastases. Indian J Surg Oncol 7:225–9.

- Newton AD, Bartlett EK, Karakousis GC. (2016). Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a review of factors contributing to morbidity and mortality. J Gastrointest Oncol 7:99–111.

- Wallet F, Maucort Boulch D, Malfroy S, et al. (2016). No impact on long-term survival of prolonged ICU stay and re-admission for patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:855–60.

- Razenberg LG, van Gestel YR, Creemers GJ, et al. (2015). Trends in cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol 41:466–71.

- Kuijpers AM, Mirck B, Aalbers AG, et al. (2013). Cytoreduction and HIPEC in the Netherlands: nationwide long-term outcome following the Dutch protocol. Ann Surg Oncol 20:4224–30.

- Glehen O, Gilly FN, Arvieux C, et al. (2010). Peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: a multi-institutional study of 159 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 17:2370–7.

- Esquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, et al. (2014). The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies (ASPSM) Multiinstitution Evaluation of the Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS) in 1,013 Patients with colorectal cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol 21:4195–201.

- Mohamed F, Moran BJ. (2009). Morbidity and mortality with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy: the importance of a learning curve. Cancer J 15:196–9.

- Kuijpers AM, Hauptmann M, Aalbers AG, et al. (2016). Cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: the learning curve reassessed. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:244–50.

- Arakelian E, Gunningberg L, Larsson J, et al. (2011). Factors influencing early postoperative recovery after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol 37:897–903.

- Villeneuve L, Passot G, Glehen O, et al. (2017). The RENAPE observational registry: rationale and framework of the rare peritoneal tumors French patient registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12:37.

- Pelz JO, Doerfer J, Dimmler A, et al. (2006). Histological response of peritoneal carcinomatosis after hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (HIPEC) in experimental investigations. BMC Cancer 6:162.

- Hompes D, D'Hoore A, Van Cutsem E, et al. (2009). Evaluation of the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) with complete cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal peroperative chemotherapy (HIPEC) with oxaliplatin: A Belgian multicenter prospective phase II clinical study. J Clin Oncol 27(15_suppl):4101.

- Elias D, Goere D, Blot F, et al. (2007). Optimization of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with oxaliplatin plus irinotecan at 43 degrees C after compete cytoreductive surgery: mortality and morbidity in 106 consecutive patients. Ann Surg Oncol 14:1818–24.

- Detroz B, Laurent S, Honore P, et al. (2004). Rationale for hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the treatment or prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Acta Chir Belg 104:377–83.

- Villeneuve L, Isaac S, Glehen O, et al. (2014). [The RENAPE network: towards a new healthcare organization for the treatment of rare tumors of the peritoneum. Description of the network and role of the pathologists]. Ann Pathol 34:4–8.

- Kusamura S, Baratti D, Hutanu I, et al. (2012). The importance of the learning curve and surveillance of surgical performance in peritoneal surface malignancy programs. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 21:559–76.

- Kusamura S, Baratti D, Deraco M. (2012). Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal surface malignancies. Ann Surg 255:348–56.